Abstract

The objectives of this quantitative study were to (1) ascertain to what extent older adults aged 50 and above feel and desire to be younger than their age, and classify themselves as young versus old; (2) compare these patterns with those found among other cross-cultural populations; and (3) assess the extent to which self-rated health and life satisfaction predict age identities. This study was carried out on a sample of 500 dwellers of the Senegalese capital aged 50 and older. This sample was constructed using the quota method to strive for representativeness. Most of the respondents wanted to be younger than their chronological age (51.8 %), but only 27.8 % felt younger than they were. Moreover, 80 % of the sample claimed to be old. Self-rated health predicted felt age and the feeling of being old. Furthermore, the less-satisfied Dakar residents were with their life, the younger they wanted to be. We first discuss our results in a comparative perspective focused on how orientations toward individualism and collectivism could be related to age identity, and on demographic characteristics of the Senegalese population—where life expectancy is 59.3 years old. We then analyze the relevance of age identity dimensions as indicators of successful aging in Dakar.

Keywords: Biological anthropology, Age identity, Successful aging, Africa

Introduction

In Western societies, many of the older adults feel younger than their chronological age (Barak et al. 2011; Barrett 2003; Demakakos et al. 2007; Kaufman and Elder 2002; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Uotinen et al. 2005; Westerhof and Barrett 2005). Several studies in fact suggest that maintaining a youthful identity is a self-enhancing illusion promoting well-being in societies that partly devalue old age (Heckhausen and Schultz 1998; Schafer and Shippee 2010). This idea is in particular supported by studies demonstrating that older adults who feel younger than their chronological age show higher scores of subjective well-being than those who feel their age or older (e.g., Westerhof and Barrett 2005). In addition, research indicates that a youthful age identity is strongly associated with older adults’ positive state of health (e.g., Barak and Stern 1986; Boehmer 2007; Demakakos et al. 2007; Knoll et al. 2004; Markides and Ray 1988; Solomon et al. 2009; Uotinen et al. 2005). These associations are consistent with the theoretical perspective that subjective age derives from a process of anchoring and adjusting one’s experience of age in light of personal, physical, and social references points (Montepare 2009). Moreover, the association of a youthful age identity with positive well-being and health has led several researchers to study age identity in the context of successful aging (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Uotinen 2005; Uotinen et al. 2003).

Recent cross-cultural comparisons of subjective age further suggest that the tendency to experience oneself as younger than one’s age is a universal phenomenon. In a comprehensive study comparing data from 18 diverse societies, Barak (2009) observed that across cultures adults typically experienced themselves to be younger than their chronological age. However, the extent of this youthful perspective differed across dimensions of age identity. More specifically, adults’ ideal age was generally reported to be younger than the age they reported feeling.

Although much has been learned about subjective age identity in recent years, a number of theoretically important questions remain. One question is the extent to which subjective age does indeed reflect a basic, universal personal dimension along which adults identify themselves. A related question is the extent to which psychological variables such as perceived health and well-being serve as determinants of age identity. To address these questions, research is necessary which examines patterns and predictors of age identity in alternative cultures. Although previous cross-cultural research has included diverse cultures, the bulk of this research has been conducted in highly modernized western societies (Barak 2009). To date, only one study has examined age identity in Africa: Barak et al. (2003) interviewed adults in Nigeria. However, this work focused mainly on younger- and middle-aged adults (20–60 years). Moreover, it did not examine the extent to which factors such as perceived health and life satisfaction served as predictors of age identity. Such were the aims of the present research.

Age identity and its dimensions

In the symbolic interactionism perspective, identity is constructed through interactions between self and society (e.g., Mead. 2006 [1934]). According to Uotinen (2005, p. 14): “when studying age identification, conceptualizations of identity that are based on an idea of self that is both flexible and socially and culturally constructed are helpful.” Therefore, in a specific social-and-cultural context, “age identity refers to the subjective evaluation of a person’s age, which is subject to individual and historical experiences” (Kaufman and Elder 2002, p. 169). Age identity is thus understood as a multidimensional concept including specific aspects of personal aging and general views of what it means to be old. Indeed, in their seminal work of subjective age, Kastenbaum et al. (1972) suggested that subjective age was a complex personal construct that reflected different “ages of me” such as how old individuals perceived themselves to feel, look, act, and desire to be. Subsequent research has drawn mainly on this conceptualization of age identity. For example, Barak’s (2009) consumer behavior research looking at individuals’ cognitive age has operationally defined age identity in terms of four questions correspond to the four dimensions of personal age suggested by Kastenbaum et al. (1972). Montepare (1996) has taken a different psychometric approach to subjective age and examined it using a multidimensional measure entailing three subscales reflecting psychological, physical, and social subjective age perceptions to parallel the basic dimensions along which development and behavior are typically described. Whatever the approach, researchers suggest that different dimensions of subjective age provide different insights into the construct and should be examined independently. The present research selected the dimensions of felt age and ideal age to assess the age identities of adults in Dakar to be able to compare more directly the extent to which they paralleled patterns observed in other cultures. In addition, some research has suggested that felt age and ideal age reflect very different aspects of one’s age identity and may be associated with different predictor patterns.

According to Demakakos et al. (2007), the ideal age of older adults has a direct connection to age-related stereotypes in society. Consequently, Western societies, sometimes described as ageist (e.g., Levy and Banaji 2002; Palmore 2002), supposedly induce older adults to wish they were younger than their chronological age. However, ideal age could also be linked to satisfaction with present age (Uotinen et al. 2003). Although scholars disagree as to the meaning of ideal age, empirical results in Western populations have shown similar patterns: in England, for example, Demakakos et al. (2007) have shown that 91.4 % of individuals aged 50 and over want to be younger than their chronological age. In Iowa (the USA), adults between the ages between 51 and 92 wanted to be 22 years younger on average than their chronological age (Kaufman and Elder 2002).

Felt age is also a construction that is indissociable from its social context, but studies indicate that it is associated with a multitude of factors, particularly health factors (e.g., Knoll et al. 2004; Solomon et al. 2009; Uotinen et al. 2005). In Western societies, several studies have demonstrated that most of the older adults felt younger than their chronological age. For example, by comparing the age identity of Americans and Germans between the ages of 40 and 74, the Westerhof and Barrett study (2005) indicated that the former felt on average 9.6 years younger than their chronological age, as opposed to “only” 6.3 years for the latter. In Finland, Uotinen et al. (2005), distinguishing between “perceived physical age” and “perceived mental age,” have shown that that 37 % of Finns aged between 65 and 84 feel physically younger than their chronological age, and 57 % feel mentally younger.

Since older people often feel younger than their age, it is not surprising that they often do not feel they belong to the “old” category either (e.g., Bultena and Powers 1978; Kaufman and Elder 2002) and only moderately identify with their age group (Weiss and Lang 2009). As with the other dimensions of age identity, the feeling of being old seems highly dependent on social context. We believe that the demographic characteristics of a given population are also data that should be taken into account in analyzing this dimension of age identity.

Age identity and cultural context: the case of Dakar

The preceding overview of the literature shows that age identity is highly dependent on the context which surrounds older adults. Westerhof and Barrett (2005), as well as Uotinen (2005) and Barak (2009), have already highlighted the importance of including cultural context more in research on age identity, especially considering how orientations toward individualism and collectivism may relate to age identity. Barak et al. (2011) have further demonstrated that independent versus interdependent self-construals may be tapped by different measures. In particular, whereas individual-focused measures (such as asking individuals what age they feel) may tap independent construals, group-comparison focused measures (such as classifying how old one feels regard to an age decade reference groups) may reflect interdependent perceptions. And, while the same pattern of ideal <felt <chronological age occurs in various population irrespective of type (independent or interdependent) of measurement, independent measures more often evidence cultural differences, whereas interdependent measures show cross-cultural less variability.

The process of individualization in Dakar and the demographic characteristics of its population may be related to age identity here as well. By United Nations criteria (UN 2009) Senegal is the 17th least developed country in the world. Life expectancy is 59.3 years old (United Nations 2011), and in the last census (2002), 5.4 % of the population was over 60 (Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) 2006). In Dakar, individuals aged 50 and older statistically make up a small portion of the population. This may lead to their usually being defined as older adults and to their considering themselves as such.

The modernization theory (Cowgill and Holmes 1972) associates the decline in the societal power of older adults in the post-industrial era with the rise of individualism and the fact that older adults have become a less valuable source of information (Uotinen 2005). According to Westerhof and Barrett (2005), individualism indeed “tends to be linked with the youth-centeredness of a culture.” The economic, social, and health situation in Dakar is conducive to a process of individualization (Werner 1997). For example, the illiteracy rate is 35 % (compared to 60.7 % for the entire country); infant-juvenile mortality is “only” 77 ‰ (121 ‰ for the entire country); 81 % of the households have access to electricity (47 % for the entire country). In 2005, the synthetic fertility rate in Dakar was 3.7 children per woman, considerably lower than that for the rural population (6.4 children per woman), indicating that the demographic transition is in progress in the capital (Ndiaye and Ayad 2006). However, even if an individualization process is underway in the Senegalese capital, it would be wrong to speak of individualism in the western sense of the word. Without going into the classic opposition between segmented and differentiated societies (Durkheim 1973 [1893]), or between collectivistic and individualistic societies (Hofstede 1980 1), individualism, as a preeminent value specifically characterizing western modernity, has no place in West Africa, “it is not because it [individualism as a value] does not exist […] but because strongly individuated individualities are supposed to put themselves exclusively in the service of social reproduction” (Marie 1997, p 63).

Ethnographic, and so relatively dated, literature indicates that in West Africa in general, deference to elders constitutes one of the pillars of social and family organizations and that older adults are the holders of traditional values and the guarantors of the perpetuation of community habitus 2 (e.g., Attias-Donfut and Rosenmayr 1994; Balandier 1974). In a recent qualitative study on the subjective quality of life and intergenerational relations in Dakar, Macia et al. (2010) have shown that respect for elders, together with the obligation to help them financially, is still one of the mechanisms by which individualism is held in check. This anthropological literature, along with the theory of modernization, tends to indicate that Senegalese society is less individualistic and less youth-centered than Western societies. One might therefore hypothesize that older adults still play a major and valued role in Dakar and that they may thus more easily identify themselves to be old, and may have an ideal and a felt age closer to their chronological age.

Age identity in the framework of successful aging

Empirical studies have brought to light several correlates of age identity in Western populations. Among these correlates, health and well-being have been the focus of particular interest over the last decades, and have been shown to have strong associations with age identity (Uotinen 2005). This evidence has led several researchers to study age identity, and/or self-perceptions of aging in the framework of successful aging (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Uotinen et al. 2003). As summarized by Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. (2008, p.378): “studies that address questions about successful aging find that youthful subjective age is associated with good health and high levels of well-being.”

Indeed, physical health is generally acknowledged to be one of the main factors influencing the age identity of older people (notably felt age). Whether the health indicators used are subjective (such as self-rated health) or objective (such as physical disabilities), studies show that poorer health factors are significant predictors of an older age identity among older adults (e.g., Barak and Stern 1986; Boehmer 2007; Knoll et al. 2004; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Markides and Ray 1988; Solomon et al. 2009). One main theoretical model serves to interpret this causal relationship between health and age identity. In fact, an individual’s felt age could be considered as an assessment of his or her personal condition compared to social representations of age and aging specific to the context in which he or she lives. These factors interact to form one’s personal aging model (Furstenberg 2002; Montepare, 2009). In western society where aging is associated with health problems, older persons in good health—who do not display the physical characteristics of old age—thus assume a younger age identity.

Furthermore, several studies have shown that older persons who have higher scores of subjective well-being also report feeling younger than their chronological than those who feel their age or perceive it as older (Barak and Stern 1986; Montepare 1996; Westerhof and Barrett 2005). Researchers on the whole accept this relationship. The idea is moreover also largely borne out by studies on (a) age-related stereotypes, and (b) subjective well-being as well as adaptive self-regulation. Indeed, there is currently a relative consensus regarding age-related stereotypes in Western societies, and most researchers today concur that age-related stereotypes are on the whole negative (e.g., Levy and Banaji 2002; Boduroglu et al. 2006; Macia et al. 2009; Palmore 2002). Yet, research on subjective well-being has shown it to vary little with age (for a review, see Diener and Suh 1998). The coping mechanisms developed by older adults and their adaptive self-regulation are thus thought to enable them to maintain high levels of well-being despite the loss of certain social roles, affective losses, health concerns likely to affect them, and of course the largely negative stereotypes pertaining to them. According to many researchers, subjective well-being should be tied to a youthful identity, especially in societies where old age is sometimes devalued (Heckhausen and Schultz 1998; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Schafer and Shippee 2010; Westerhof and Barrett 2005).

Objectives

To fill in gaps in the existing literature on age identity, the primary objectives of this study in Dakar, the administrative and economic capital of Senegal, were thus (1) to ascertain to what extent older adults aged 50 and above feel and desire to be younger than their age, and classify themselves as young versus old; (2) to compare these patterns with those found among other cross-cultural populations; and (3) to assess the extent to which self-rated health and life satisfaction predict age identities.

Materials and methods

Population sample

This study was conducted from January to June 2009 on a sample of 500 individuals aged 50 and older. This sample was constructed using the quota method (cross-section by age, gender and town of residence) to strive for representativeness of the population aged 50 and older living in the department3 of Dakar. Data from the Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie dating from the last census (2006) were used to this end. The quota variables used were gender (male/female), age (50–59/60–69/70 and over, with an upper age limit of 100 years) and town of residence. The towns were grouped by the four arrondissements making up the department of Dakar: Plateau-Gorée (5 towns), Grand Dakar (6 towns), Parcelles Assainies (4 towns) and Almadies (4 towns). Practically, this method requires constructing a sample that reflects the proportions observed in the general population. For example, according to the last census, men aged 50–59 living in town of Medina (arrondissement of Plateau-Gorée) represented 2.4 % of the population aged 50 and older living in the department of Dakar. The sample has been constructed so as to reflect this proportion and include 12 men aged 50–59 living in this town.

For each town, four investigators (PhD students in Medicine and Pharmacy) started out from different points each day to measure and interview individuals in Wolof or French in every third home. Investigators had a given number of individuals to interview (women aged 50–59/men aged 50–59/women aged 60–69/men aged 60–69/women aged 70 and over/men aged 70 and over, in each town) to meet the quotas. Only one person was selected as a respondent in each home.

Face-to-face guided interviews based on a questionnaire were used to collect the data required for the study. The questionnaire contained items about age (official age, chronological age, ideal age, felt age), socioeconomic characteristics, health and health-related quality of life, nutrition and physical activity, life satisfaction, material well-being, as well as the quality of social relations. The interviews lasted from 1 to 2 h depending on the respondents’ desire or need to talk. The quantitative objective of this biological-anthropological survey was to carry out a holistic study of aging in the department of Dakar. Only a portion of this data was used for this article.

Measurements

Age identity

Four age identity questions were asked in this study. The first, emphasizing the medical aspect of our study so as to convince participants to tell us their chronological age, was: “For medical reasons, we need to know your age. Could you please tell us?” Ideal age was measured by asking the respondents, “If you could be any age you like, what would it be?” Information regarding felt age was collected via the following question: “Deep down inside, what age do you feel?” Lastly, the feeling of being old was evaluated with the following question: “Do you feel you are part of the old age group [maget]?”4

Based on responses to the age identity questions, two indices were computed as often done in related research: ideal age was computed as the difference between chronological age and ideal age; felt age was computed as the difference between chronological age and felt age. Thus, larger difference values indicated younger ideal or felt age identities. The feeling of being old was evaluated as the extent to which individuals classified themselves as being part of the old age group.

Satisfaction with life

Subjective well-being is now widely accepted to be a multidimensional concept made up of cognitive assessment of life in general (i.e. life satisfaction) and an individual’s positive and negative affects (Diener et al. 1999). In the present study, only the Diener et al. (1985) satisfaction with life scale was used as an indicator of subjective well-being. As this scale had never previously been used in Senegal, we first had to validate its content and translate it before using it.

To assess the validity of the content of the satisfaction with life scale for the Dakar context, we called on a panel of experts, as suggested in related research (e.g., Contandriopoulos et al. 1990). The French language version of this scale (Blais et al. 1989)—along with all the other scales used in this study—was therefore presented to several Senegalese and French researchers from a variety of disciplines (anthropology, sociology, philosophy, neurology, physiology) in the course of a “questionnaire validation meeting.” All researchers, without exception, agreed that the items on this scale were relevant to the Dakar population, and even for the Senegalese population as a whole. After that, the parallel back-translation procedure described by Vallerand (1989) was used to translate the scale into Wolof, the language spoken by everyone in the Senegalese capital.

The internal coherence of this scale, which includes 5 items with 7 possible answers, was highly satisfactory in our sample population (α = 0.818). For consistency with the results in the literature (e.g., Westerhof and Barrett 2005), the original scores—ranging from 7 to 35—were converted to a 10-point scale (10 corresponding to high life satisfaction).

Self-rated health

Self-rated health was measured using a question with five possible answers: “Overall, would you say that your health is: excellent, very good, good, mediocre, or poor?” This variable was dichotomized for analysis. The split was made between the answers “excellent,” “very good,” and “good” (scored 0) and the answers “mediocre” and “poor” (scored 1).

Sociodemographic variables

Among the sociodemographic data collected during the interviews, three were taken into account for this study: gender, educational level, and marital status. Gender was coded as follows: 1 for women; 0 for men. Five levels of education were defined: none, primary (theoretically for children between 6 and 10 years old), 1st cycle secondary (for children between 11 and 14 years old), 2nd cycle secondary (for children between 15 and 18 years old), and university. Marital status was coded as follows: married (=0)/other (=1). These variables were included in the analyses as control variables.

Analyses

We used bivariate and multivariate tests to assess the associations among measures. Linear regression equations were then used to assess the extent to which self-rated health and life satisfaction predicted ideal and felt age. In these analyses, chronological age along with the other sociodemographic variables were included to assess the relative predictive value of these factors. As other researchers have done, the computed age identity indices were used to assess the extent to which individuals felt or desired to be younger than their age was predicted by health and satisfaction. A logistic regression was performed to test predictors of classifying oneself as old. The software used for the statistical analysis was PASW Statistics 18, published by SPSS Inc. (Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Summary descriptive statistics for all measures are presented in Table 1. Demographic data indicated that the majority of the sample was in their fifties, male, married, with a low education level.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, self-rated health, feeling of being old, ideal and felt age characteristics of the sample (N = 500)

| Variables | Categories | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age | 50–59 years | 268 | 53.6 |

| 60–69 years | 136 | 27.2 | |

| 70–100 years | 96 | 19.2 | |

| Gender | Male | 263 | 52.6 |

| Female | 237 | 47.4 | |

| Educational level | None | 228 | 45.6 |

| Primary | 113 | 22.6 | |

| 1st cycle secondary | 73 | 14.6 | |

| 2nd cycle secondary | 50 | 10.0 | |

| University | 36 | 7.2 | |

| Marital status | Married | 372 | 74.4 |

| Not married | 128 | 25.6 | |

| Self-rated health | Excellent/very good/good | 355 | 71 |

| Mediocre/poor | 145 | 29 | |

| Ideal age | <Chronological age | 259 | 51.8 |

| =Chronological age | 209 | 41.8 | |

| >Chronological age | 32 | 6.4 | |

| Felt age | <Chronological age | 139 | 27.8 |

| =Chronological age | 346 | 69.2 | |

| >Chronological age | 15 | 3.0 | |

| Feeling of being old | Yes | 397 | 79.4 |

| No | 103 | 20.6 |

Patterns of age identity

The sample on average was approximately 61.3 ± 9.7 years old. However, adults reported their ideal age to be younger than their chronological age by about 9.6 years (mean ideal age was 51.7 ± 18.7 years). Adults also felt younger than their chronological age, but by only about 2.6 years (mean felt age was 58.7 ± 11.2 years). In terms of percentages, most of the respondents wanted to be younger than their chronological age (51.8 %), and for 41.8 % of the sample ideal age matched chronological age. For only 27.8 % of the participants, felt age was younger than chronological age: for a large majority felt age matched chronological age (69.2 %). Moreover, a large majority of the respondents (79.4 % of the sample) claimed to identify with the group of old people.

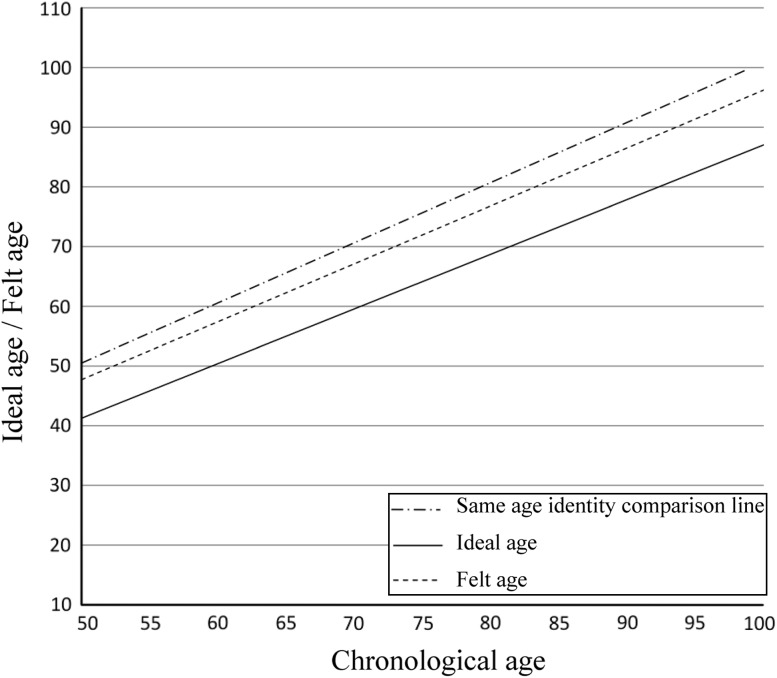

As indicated in Table 2, advances in chronological age were associated with older ideal and felt ages. And, ideal ages were consistently younger than felt ages. A more detailed analysis of the relationship between chronological age, ideal age and felt age is depicted in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlations between chronological age, ideal age, felt age (N = 500)

| Chronological age | Ideal age | Felt age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age | 1 | 0.478*** | 0.842*** |

| Ideal age | 1 | 0.388*** | |

| Felt age | 1 |

*** p < 0.001

Fig. 1.

Ideal age and felt age according to chronological age (N = 500)

Age identity, self-rated health, and life satisfaction

Bivariate analyses

Spearman correlation tests showed that self-rated health was significantly correlated with felt age identity (r = 0.237, p < 0.001), but not with ideal age identity (r = −0.003, ns). Thus, the more Senegalese older adults rated their health positively, the younger their felt age, but not their ideal age. Furthermore, a χ2 test indicated that people who rated their health poorly (“mediocre” or “poor”) more often felt they belonged the old age group than those who rated their health better (91.0 vs 74.6 %; χ2(1df) = 16.90, p < 0.001).

A Pearson correlation showed that life satisfaction was negatively and significantly correlated with ideal age identity (r = −0.142, p < 0.001). Thus, the less satisfied Dakar residents were with their life, the younger they wished to be. Life satisfaction was not significantly correlated with felt age identity (r = 0.063, ns). Furthermore, the mean life satisfaction score of people who felt they were old (5.75 ± 2.03) was higher than those of people who do not feel they were old (5.04 ± 1.84; t = 3.261, p < 0.001).

Multivariate analyses

Table 3 presents the results of the linear regressions predicting participants’ associations with ideal age and felt age identities. These results indicate that self-rated health predicted felt age but not ideal age identities, whereas life satisfaction predicted ideal age but not felt age identity. People with positive self-rated health felt younger (compared to their chronological age) than those who rated their health as mediocre or poor, even when all the sociodemographic factors were controlled in the analysis. Conversely, the more Senegalese adults were satisfied with their life, the less they wished to be younger.

Table 3.

Ordinary least squares regression predicting ideal age and felt age identities (N = 500)

| Variable | Category | Ideal age identity | Felt age identity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | ||

| Chronological age | 0.207* | 0.090 | 0.026 | 033 | |

| Gender (men) | Women | 1.949 | 1.657 | −0.507 | 607 |

| Educational level (university) | None | −5.860 | 3.102 | −2.713* | 1,137 |

| Primary | −4.506 | 3.196 | −2.678* | 1,171 | |

| 1st cycle secondary | −6.258 | 3.367 | −2.082 | 1,233 | |

| 2nd cycle secondary | −3.606 | 3.579 | −0.648 | 1,312 | |

| Marital status (married) | Not married | −2.950 | 1.821 | 0.486 | 667 |

| Self-rated health (good to excellent) | Mediocre/poor | −1.713 | 1.732 | −1.900** | 635 |

| Life satisfaction | −1.585*** | 0.391 | 0.094 | 143 | |

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Table 4 presents the results of logistic regression using the feeling of being old as dependent variable. It confirms the bivariate results described above, as negative self-rated health significantly predicted the feeling of being old, even when the sociodemographic factors are included in the analysis as control variables. However, life satisfaction no longer predicted the feeling of being old when this relationship is controlled by the set of sociodemographic factors and self-rated health.

Table 4.

Logistic regression predicting the feeling of being old (N = 500)

| Variable | Category | OR | IC for OR (95 %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age | 1.20*** | 1.14–1.27 | |

| Gender (men) | Women | 2.01* | 1.13–3.58 |

| Educational level (university) | None | 4.41** | 1.72–11.31 |

| Primary | 3.12* | 1.19–8.14 | |

| 1st cycle secondary | 3.77* | 1.33–10.68 | |

| 2nd cycle secondary | 1.45 | 0.52–4.03 | |

| Marital status (married) | Not married | 1.07 | 0.55–2.08 |

| Self-rated health (good to excellent) | Mediocre/poor | 2.30* | 1.11–4.78 |

| Life satisfaction | 1.09 | 0.95–1.26 |

Note The −2 log likelihood (−2LL; relative model fit statistics) was 373.58

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Discussion

Patterns of age identity

Westerhof and Barrett (2005) concluded in their study of the relationship between age identity and subjective well-being in the United States and in Germany that a greater emphasis on cultural context should be included in this growing area of research. The results of our study fully bear this out, and reveal several insights cross-cultural explorations have to offer in deepening our understanding subjective age identification.

Three dimensions of age identity were explored among older adults in Dakar: ideal age, felt age, and the feeling of being old. Consistent with previous cross-cultural work in more modernized Western and non-Western societies, the present research found that with age, adults not only perceive themselves as younger than their chronological age, but also desire to be younger. As well, ideal age identities show a larger discrepancy with chronological age than felt age as others have found (Barak 2009; Barak et al. 2011). Thus, the present work suggests that subjective age may be a fundamental, universal psychological dimension along which adults define themselves and their aging experience.

At the same time, differences in certain characteristics of subjective age were observed, pointing to the influence of cultural contexts on variations in the adults’ age identities. For instance, in the Dakar sample, ideal age was about 10 years below chronological age, and “only” 51.8 % of the participants desired to be younger. In a similar age sample, Kaufman and Elder (2002) noted a larger 22 year difference between chronological age and ideal age in Iowa. In an age sample of 50 and over in England, Demakakos et al. (2007) also observed large discrepancies with 91.4 % of adults wanting to be younger than their chronological age.

Noteworthy patterns of differences in felt age were also found. As was observed for ideal age, Dakar older adults’ felt age was much closer to their chronological age than has been observed among their western counterparts. For example, Westerhof and Barrett (2005) found that that Americans between the ages of 40 and 74 felt on average 9.6 years younger than their chronological age, as opposed the 6.3 years for Germans. In contrast, the older adults in Dakar reported feeling only slightly younger, about 2.6 years, than their chronological age. As well, in the present sample, 80 % of the participants identify with the older age group, which clearly differentiates them from older western people for whom this classification is less accepted (e.g., Bultena and Powers 1978; Levy and Banaji 2002). For example, Bultena and Powers found that, 65 % of Americans aged 65 and older identified themselves as “middle-aged” rather than “elderly” or “old.”

What might account for the observed differences in patterns of age identification? Demakakos et al. (2007) and others have argued that younger age identities derive from negative cultural views of age. To the extent that older adults in Dakar hold less extreme age identities, one can speculate that their views of old age are less negative that their Western counterparts. The modernization theory (Cowgill and Holmes 1972) and anthropological literature addressing individualism and collectivism can also be useful in interpreting differences between Senegalese and Western older adults. Undeniably, Senegalese society is less individualistic than Western societies (Werner 1997), as it is less associated with youth-centered values (Westerhof and Barrett 2005). It is therefore likely that the societal power of older adults remains high in Dakar (Macia et al. 2010). In such a society, feeling younger may thus not be a self-enhancing illusion promoting well-being as in societies where old age is sometimes devalued (i.e. western societies). Our results are consistent with this hypothesis since felt age was not significantly associated with life satisfaction in our sample. However, other explanations can also be envisaged, and qualitative studies should be carried out to better understand felt age in the Senegalese context.

Our anthropological interpretation of felt age in the Senegalese context could also be employed to explain the frequent feeling of being old among older adults in Dakar. Indeed, if the societal power of older adults remains high in Dakar, they can more easily assume their age status than in the West. However, this result should be replaced in the demographic context of Senegal. In a country where life expectancy is only 59.3 years (United Nations 2011), it is not surprising that the majority of persons aged 50 and over feel they belong to the old age group. This major demographic difference between Senegal and western countries would appear largely to explain why people in their fifties in Dakar feel old. One might thus speculate that old age begins around 50 in Senegal. Nonetheless, qualitative research is necessary to confirm this interpretation.

Age identity in the framework of successful aging

Ideal age is often described as an indicator of satisfaction with aging (e.g., Uotinen 2005). In Dakar, younger ideal ages were significantly predicted by how satisfied adults were with their lives, in and above the potential contribution of other distinguishing sociodemographic factors. Moreover, whereas life satisfaction was strongly predictive of ideal age, perceived health was not. This result echoes recent qualitative research carried out by Macia et al. (2010) indicating that “being happy with what one has” is perceived and clearly expressed by both young and older Dakar residents as necessary to maintaining the quality of life. Not wanting to be younger than one’s age may be a coping strategy to fit in with what is socially acceptable and/or simply possible. In our sample population, however, self-rated health was not associated with ideal age. This result matches those of Hubley and Hultsch (1994) in Canada, but is in contradiction with those of Uotinen et al. (2003) on the Finnish population. This latter study demonstrated that older Finnish in better health showed less of a discrepancy between ideal and chronological age. The various indicators of health used in the studies could partly explain the inconsistency of the results. Further investigation, comparing several health indicators, is needed to better understand the links between ideal age and health not only in Dakar but in Western societies as well.

In the present study, self-rated health predicted variations in felt age, in and above potential sociodemographic predictors. The more the older adults rated their health as negative, the older they felt. This outcome indicates that felt age could be considered as an indicator of the general health of older adults in Dakar, as in Western populations (e.g., Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Markides and Ray 1988; Uotinen et al. 2003). Likewise, health status was an indicator of feeling old insofar as older adults who rated their health as poor or mediocre more often considered themselves as older adults. This finding is also consistent with models of subjective age which suggest that the age individuals experience themselves to be derives in part from proximal physical and other cues which provide age referencing information (Montepare 2009)

However, unlike what has been observed in Western countries, felt age was not significantly predicted by life satisfaction. This result could once again be interpreted in terms of individualism/collectivism. According to several researchers, feeling younger is a self-enhancing illusion promoting well-being in societies where old age is sometimes devalued (Heckhausen and Schultz 1998; Schafer and Shippee 2010; Westerhof and Barrett 2005). In a more collectivistic society where older adults apparently still have high societal power (Macia et al. 2010), feeling younger is perhaps not such a self-enhancing illusion. Moreover, as Westerhof and Barrett (2005) indicate, the more individualistic the society, the greater the need for positive illusions. According to this interpretation, Senegalese older adults may have less of a need for positive illusions to maintain a high level of well-being. The same reasons could also explain why feeling old was not predicted by life satisfaction in our sample. Nevertheless, other interpretations can be imagined and other studies should be conducted to better understand how age identity is constructed in Dakar, especially in relation to life satisfaction.

Several qualifications and directions for future work may be outlined. The present data were correlational, making it necessary to consider the causal links assumed in this research in more detail. Indeed, although health status is usually described has having an impact on age identity, it is equally possible that one’s age identity influences how one interprets one’s health status. For instance, the results of the longitudinal studies conducted by Uotinen et al. (2005) and Demakakos et al. (2007) have shown that age identity was a predictor of self-rated health, hypertension, diabetes and mortality. At the same time, in their longitudinal study of age identity, Markides and Boldt (1983) found that changes in subjective age were predicted by changes in health status over time. The need for a more comprehensive analysis of the directionality and timing of age identity and its correlates is surely an area for extended exploration, especially in cross-cultural contexts.

Furthermore, as this was a quantitative study, our interpretations and conclusions need to be tested through qualitative research and the use of more direct measures of cultural attitudes and perspectives to achieve a better understanding of how age identity is constructed as well as the social representations of old age and the elderly in Dakar.

Future cross-cultural research would also benefit from looking more closely as the extent to which age identity and its physical and psychological correlates operate within cultural subgroups. In the present study, differences in gender, educational level, and marital status were used primarily as control variables. However, other research has suggested that older individuals, as well as unmarried persons and people in the lower socio-occupational categories have older felt age than, respectively, younger people, married people, and people in higher socio-occupational categories (Barrett 2003; Kaufman and Elder 2002; Markides and Boldt 1983; Westerhof and Barrett 2005). Some researchers have also suggested that subjective age and its correlated may differ between men and women, although research on gender-related differences had mixed results. While some researchers have found aging women to experience younger subjective ages, others have found no differences in men’s and women’s subjective ages (Barak and Stern 1986; Montepare 1991; Montepare and Lachman 1989; Pinquart and Sörensen 2001). Although by and large, results obtained in Dakar appeared to vary only with respect educational level, more in-depth research with hypotheses tailored to specific demographic groups is warranted.

Barak et al. (2011), along with Westerhof and Barrett (2005) and Montepare (2009), have made the compelling argument that cultural context needs to be taken into greater account more broadly in gerontological research and theory on subjective age identification. The present research took a step in this direction by examining in more detail patterns and predictors of various dimensions of age identity in a distinctive non-western population of older adults. Drawing on theory and evidence generated in the developed world, researchers working in southern hemisphere countries can and should take the call to action to further this work.

Footnotes

For example, the individualism versus collectivism (IDV) dimension if of the 25 in Senegal (compared to 91 in the USA; http://geert-hofstede.com/senegal.html).

The term habitus comes from the study of Marcel Mauss (1936). Habitus could be simply defined as the lifestyle habits of the individuals, mostly dependent on the social class in which they evolve (Bourdieu 1980). In this paradigm, hexis is the active and behavioral expression of the habitus.

In Senegalese administrative zoning, Dakar is both a region and a department. Dakar’s region includes four departments: Pikine, Guediawaye, Rufisque, and Dakar. In general, Pikine, Guediawaye, and Rufisque are referred to as suburbs, whereas the department of Dakar is the “real” city.

Maget means “to be old” and/or “older adult” in Wolof. It is the more conventional term to speak about old age and older adults.

References

- Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) (2006) Résultats du troisième recensement général de la population et de l’habitat du Sénégal RGPHIII. Rapport National de Présentation. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSENEGALINFRENCH/Resources/461584-1175072268436/TROISIEMERECENSEMENTPOPULATIONETHABITATSENEGAL.pdf. Accessed 14 Nov 2010

- Attias-Donfut C, Rosenmayr L. Vieillir en afrique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Balandier G. Anthropo-logiques. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Barak B. Age identity: a cross-cultural global approach. Int J Behav Dev. 2009;22:2–11. doi: 10.1177/0165025408099485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barak B, Stern B. Subjective age correlates: a research note. Gerontol. 1986;26:571–578. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak B, Mathur A, Zhang Y, Lee K, Erondu E. Age satisfaction in Africa and Asia: a cross-cultural exploration. Asia Pac J Mark Logist. 2003;15:3–26. doi: 10.1108/13555850310765042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barak B, Guiot D, Mathur A, Zhang Y, Lee K. An empirical assessment of cross-cultural age self-construal measurement: evidence from three countries. Psychol Mark. 2011;28:479–495. doi: 10.1002/mar.20397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE. Socioeconomic status and age identity: the role of dimensions of health in the subjective construction of age. J Gerontol. 2003;58B:S92–S100. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais MR, Vallerand RJ, Pelletier LG, Brière NM. L’échelle de satisfaction de vie: validation canadienne-française du “satisfaction with life scale.”. Rev Can Sci Comport. 1989;21:210–223. [Google Scholar]

- Boduroglu A, Yoon C, Luo T, Park DC. Age-related stereotypes: a comparison of American and Chinese cultures. Gerontology. 2006;52:324–333. doi: 10.1159/000094614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer S. Relationships between felt age and perceived disability, satisfaction with recovery, self-efficacy beliefs and coping strategies. J Health Psychol. 2007;12:895–906. doi: 10.1177/1359105307082453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. La distinction: critique sociale du jugement. Paris: Editions de Minuit; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bultena GL, Powers EA. Denial of aging: age identification and reference group orientations. J Gerontol. 1978;52:125–134. doi: 10.1093/geronj/33.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contandriopoulos AP, Champagne F, Potvin L, Denis JL, Boyle P (1990) Savoir préparer une recherche. La définir, la structurer, la financer. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, Montréal

- Cowgill DO, Holmes LD. Aging and modernization. New-York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Demakakos P, Gjonca E, Nazroo J. Age identity, age perceptions and health. Evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1114:279–287. doi: 10.1196/annals.1396.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM. Subjective well-being and age: an international analysis. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 1998;17:304–324. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RE, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Personal Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas R, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E (1973 [1896]) De la division du travail social, 9th edn. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

- Furstenberg AL. Trajectories of aging: imagined pathways in later life. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2002;55:1–24. doi: 10.2190/3H62-78VR-6D9D-PLMH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Schultz R. Developmental regulation in adulthood: selection and compensation via primary and secondary control. In: Dweck CS, Heckhausen J, editors. Motivation and self-regulation across the life span. New-York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 50–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hubley AM, Hultsch DF. The relationship of personality trait variables to subjective age identity in older adults. Res Aging. 1994;16:415–439. doi: 10.1177/0164027594164005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenbaum R, Derbin V, Sabatini P, Arrt S. “The ages of me”: toward personal and interpersonal definitions of functional aging. Aging Hum Dev. 1972;3:197–211. doi: 10.2190/TUJR-WTXK-866Q-8QU7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman G, Elder GH. Revisiting age identity: a research note. J Aging Stud. 2002;16:169–176. doi: 10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00042-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn A, Kotter-Grühn D, Smith J. Self-perceptions of aging: Do subjective age and satisfaction with aging change during old age? J Gerontol. 2008;63B:P377–P385. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.p377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll N, Rieckmann N, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Predictors of subjective age before and after cataract surgery: conscientiousness makes a difference. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Banaji MR. Implicit ageism. In: Nelson T, editor. Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2002. pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Lahmam A, Baali A, Boëtsch G, Chapuis-Lucciani N. Perception of age stereotypes and self-perception of aging: a comparison of French and Moroccan populations. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2009;24:391–410. doi: 10.1007/s10823-009-9103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Duboz P, Gueye L. Les dimensions de la qualité de vie subjective à Dakar. Sci Soc Santé. 2010;25:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Marie A. Du sujet communautaire au sujet individuel. Une lecture anthropologique de la réalité africaine contemporaine. In: Marie A, editor. L’Afrique des individus. Paris: Karthala; 1997. pp. 53–110. [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Boldt JS. Change in subjective age among the elderly: a longitudinal analysis. Gerontologist. 1983;23:422–427. doi: 10.1093/geront/23.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Ray LS. Change in subjective age among the elderly: an eight-year longitudinal study. Compr Gerontol. 1988;2:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss M. Les techniques du corps. In: Mauss M, editor. Sociologie et anthropologie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 1936. pp. 363–383. [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH ([1934] 2006) L’esprit, le soi et la société. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

- Montepare JM. Characteristics and psychological correlates of young adult men’s and women’s subjective age. Sex Roles. 1991;24:323–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00288305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montepare JM. An assessment of adults’ perceptions of their psychological, physical, and social ages. J Clin Geropsychol. 1996;2:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Montepare JM. Subjective age: toward a guiding lifespan framework. Int J Behav Dev. 2009;33:42–46. doi: 10.1177/0165025408095551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montepare JM, Lachman ME. “You’re only as old as you feel”: self-perceptions of age, fears of aging, nd life satisfaction from adolescence to old age. Psychol Aging. 1989;4:73–78. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.4.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye S, Ayad M. (2006) Enquête démographique et de santé au Sénégal 2005. Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Humain [Sénégal] et ORC Macro, Calverton

- Palmore E. Ageism in Canada and the United States. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2002;19:41–46. doi: 10.1023/B:JCCG.0000015098.62691.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in self-concept and psychological well-being in old age: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol. 2001;56B:P195–P213. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.p195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer MH, Shippee TP. Age identity, gender, and perception of decline: Does feeling older lead to pessimistic dispositions about cognitive aging? J Gerontol. 2010;65B:S91–S96. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Helvitz H, Zerach G. Subjective age, PTSD and physical health among war veterans. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:405–413. doi: 10.1080/13607860802459856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2002) Rapport de la deuxième assemblée mondiale sur le vieillissement. Madrid. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N02/397/52/PDF/N0239752.pdf?OpenElement. Accessed 8–12 April 2002

- United Nations (2011) Human development report 2009. http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2011_EN_Complete.pdf. Accessed 15 Sep 2011

- Uotinen V (2005) I’m as old as I feel. Subjective age in Finnish adults. Dissertation, University of Jyväskylä

- Uotinen V, Suumata T, Ruoppila I. Age identification in the framework of successful aging. A study of older Finnish people. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;56:173–195. doi: 10.2190/6939-6W88-P2XX-GUQW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uotinen V, Rantanen T, Suutama T. Perceived age as a predictor of old age mortality: a 13-year prospective study. Age Ageing. 2005;34:368–372. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand RJ. Vers une méthodologie de validation transculturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: implications pour la recherche en langue française. Can Psychol/Psychol Can. 1989;30:662–680. doi: 10.1037/h0079856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Lang F. Thinking about my generation: adaptive effects of a dual age identity in latter adulthood. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:729–734. doi: 10.1037/a0016339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner JF. Itinéraires individuels à la marge. Etudes de cas sénégalais. In: Marie A, editor. L’Afrique des individus. Paris: Karthala; 1997. pp. 367–403. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof GJ, Barrett AE. Age identity and subjective well-being: a comparison of the United States and Germany. J Gerontol. 2005;60B:S129–S136. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]