How orangutans survive in fragmented habitats

Bornean orangutan.

Since 2016, Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), which inhabit the increasingly fragmented forests of the Sabah region of the Malaysian Borneo, have been listed as critically endangered in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. Using high-resolution LiDAR and GPS-enabled visual tracking of animals from 2014 to 2016, Andrew Davies et al. (pp. 8307–8312) attempted to determine how a well-documented group of around 800 orangutans move through canopies and select habitats within a 7.4-km2 swath of the Lower Kinabatangan wildlife sanctuary in the Malaysian Borneo, which is dotted with forests fragmented by logging, oil palm plantations, and other human activities. Orangutans largely avoided canopy gaps but preferred dense upper canopy cover, tall trees, uniform canopy heights, and proximity to emergent crowns, suggesting that the primates are sensitive to canopy attributes, despite their ability to survive in disturbed forests. In contrast, orangutans appeared indifferent to canopy shape and vertical layering. Belying the presumption that males and females would favor canopies with different 3D structures by virtue of their differing weight and tendency for risk aversion, the authors found no significant differences in canopy use based on age or sex. According to the authors, the findings underscore orangutans’ resilience in the face of habitat fragmentation as well as the need to account for upper canopy attributes in orangutan habitat conservation efforts. — P.N.

Treating sepsis in a baboon model

Bacterial sepsis, which is generally accompanied by the activation of the complement system, can be life-threatening. Complement inhibition has long been considered a potential therapy against sepsis, but the ideal targets of inhibition are unclear. Ravi Shankar Keshari et al. (pp. E6390–E6399) used a baboon model of Escherichia coli sepsis to investigate the therapeutic potential of RA101295, an inhibitor of complement C5 cleavage. The authors found that RA101295 effectively inhibited E. coli-induced complement activation in vitro in a human whole-blood assay and in vivo in the baboon model. Inhibiting C5 in vivo in E. coli-challenged baboons led to reductions in bacteriolysis, lipopolysaccharide release, and proinflammatory cytokine production, but did not affect bacterial clearance. In addition, RA101295-treated animals experienced reduced leukocyte activation and decreased activation of the coagulation pathways and the fibrinolytic system compared with untreated animals. RA101295 treatment led to significant organ protection and improved survival of septic baboons, with four out of five treated baboons surviving a bacterial dose that led to 100% mortality in untreated animals. The results indicate that the terminal part of the complement system plays a crucial role in sepsis progression. Inhibition of complement C5 cleavage could serve as a potential therapeutic approach for bacterial sepsis, according to the authors. — S.R.

Age estimates in small-scale societies

Agta woman from Palanan, Philippines, wearing traditional bracelets.

In human societies, life histories can be characterized by key events such as the age of first reproduction, length of childhood dependence, interbirth intervals, and life span. Such traits reveal population age structures and allow anthropologists to reconstruct how human life histories evolved. Accurate age estimation, however, is challenging, especially for small societies that do not mark the passage of time in calendar years. Yoan Diekmann et al. (pp. 8205–8210) describe a Bayesian approach—a form of statistical inference—to account for the inherent difficulty and uncertainty of estimating individuals’ ages in the field. Using estimated age ranges as well as age ranks from youngest to oldest, which people in small societies can report with reasonable accuracy, the authors’ model produces Bayesian posterior distributions of age, a kind of probability curve derived from both prior assumptions and sample data, for each individual. The authors demonstrate how the approach improves upon other methods by analyzing data from 65 Agta foragers from the Philippines with known ages. Next, the authors applied the approach to a more challenging dataset of 587 Agta spanning multiple camps and used the results to infer age-specific fertility patterns in the entire population. The findings demonstrate how Bayesian statistics can help refine age estimates, according to the authors. — T.J.

Inducing cervical ripening

Crucial to successful vaginal birth, cervical ripening refers to remodeling of the matrix of the cervix that precedes the onset of contractions and allows dilation and birth. Although medical practitioners induce cervical softening and labor using prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), the mechanisms of prostaglandin-mediated cervical ripening remain poorly understood. Annavarapu Hari Kishore et al. (pp. E6427–E6436) detail the molecular mechanism by which PGE2 acts in cervical stromal cells to amplify its own synthesis and initiate cervical ripening. The authors show that PGE2 increases calcium ion signaling in stromal cells via EP2 receptors, signaling the dephosphorylation of the HDAC4 protein and triggering its movement to the nucleus. This translocation downregulates 15-hydroxy prostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH), an enzyme that neutralizes PGE2 by converting it to an inactive metabolite. Furthermore, PGE2 upregulates cyclooxygenase-2 and PGE synthase, two enzymes that synergistically form PGE2. The authors also present results from in vivo experiments with human cervical stromal cells and a mouse model that together confirm the role of 15-PGDH in cervical ripening. The findings suggest a pharmacological pathway to induce or delay cervical ripening, according to the authors. — T.J.

Persistent stress response and traumatic brain injury

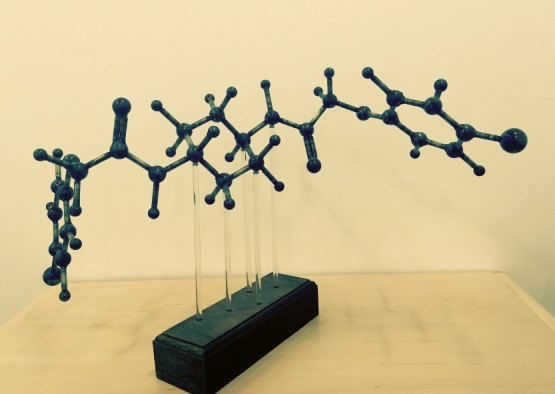

Welded sculpture showing the structure of ISRIB.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) carries consequences that can last a lifetime, from permanently impaired cognition and memory to increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Although surgery and behavioral rehabilitation can help patients cope with ongoing symptoms, no pharmacological therapies currently exist. Austin Chou et al. (pp. E6420–E6426) report that TBI causes the integrated stress response (ISR) signaling pathway to remain persistently activated in the hippocampus, a brain region implicated in memory and learning. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate that a small molecule called ISR inhibitor (ISRIB) inhibits the core event of ISR and restores cognitive deficits in mice. Common to all eukaryotic cells, ISR acts to restore cellular homeostasis by phosphorylating eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α). Due to its small size, ISRIB readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and blunts the restoration. To determine whether sustained hippocampal eIF2α phosphorylation underpins the long-term symptoms of TBI, the authors conducted trials with two different murine models and found that ISRIB treatment is sufficient to reverse hippocampus-dependent cognitive deficits. In addition, systemic ISRIB treatment weeks after injury enabled mice to form stable spatial memories that persisted at least 1 week after treatment stopped. Though preliminary, the findings point to a potential therapeutic path for TBI, according to the authors. — T.J.