Abstract

Many empirical studies throughout the social and biomedical sciences focus only on very narrow outcomes such as income, or a single specific disease state, or a measure of positive affect. Human well-being or flourishing, however, consists in a much broader range of states and outcomes, certainly including mental and physical health, but also encompassing happiness and life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and close social relationships. The empirical literature from longitudinal, experimental, and quasiexperimental studies is reviewed in attempt to identify major determinants of human flourishing, broadly conceived. Measures of human flourishing are proposed. Discussion is given to the implications of a broader conception of human flourishing, and of the research reviewed, for policy, and for future research in the biomedical and social sciences.

Keywords: flourishing, well-being, happiness, family, religion

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being” (1). Much of the discipline of economics is allegedly devoted to the maximization of some notion of expected utility, supposedly taking into account all aspects of an agent’s preferences. The goal of the discipline of positive psychology is sometimes articulated as “the scientific study of the strengths that enable individuals and communities to thrive” (Positive Psychology Center, University of Pennsylvania; https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/). However, our actual empirical studies in medicine and public health, in psychology, in economics, and in many other disciplines are often restricted to very narrow outcomes. Empirical research in health typically addresses only a single disease; many psychological studies focus only on the alleviation of symptoms; empirical studies in economics not infrequently only examine effects on income or the production and consumption of goods and services. If a central goal of these disciplines is more fundamentally contributing to some broader notion of human well-being, then it would seem that the empirical studies and the measures used should more often consider a broader conception of well-being and flourishing, and that our investigations into etiology should likewise examine the causes and interventions that most contribute to human flourishing, broadly conceived. In this paper, I would like to outline a proposal concerning shifting empirical research in that direction. I will discuss a number of broader outcome measures that might be used, and I will discuss, based on current evidence, what seem to be substantial determinants of human flourishing. I will finally comment on the implications of this for policy and for future empirical research in the biomedical and social sciences (2–10).

On Human Flourishing

Various measures of subjective well-being have been proposed in the positive-psychology literature (11–14). Some of the most widely used measures concern either happiness conceived of as a positive affective state, sometimes referred to as “hedonic happiness,” or alternatively overall life satisfaction, sometimes referred to as “evaluative happiness” (15). Representative questions, often rated on a scale of 0–10, include the following: “In general, how happy or unhappy do you usually feel?” (14) or “Overall, how satisfied are you with life as a whole these days?” (16). More recently, broader composite measures have been proposed encompassing numerous aspects of psychological well-being (17–21). These composite measures sometimes include positive affect and life satisfaction but also a collection of others such as meaning, purpose, autonomy, self-acceptance, optimism, positive relationships, mastery, self-determination, resilience, personal growth, vitality, engagement, and self-esteem. Different measures combine different subsets of these various attributes. These broader composite measures or certain items of these broader measures are sometimes referred to as measures of “eudaimonic” happiness or well-being (15). As measures of psychological well-being, many of these may be reasonable. However, there are long-standing traditions that suggest that flourishing consists of something more than one’s mental state and how one feels about various aspects of life.

Notably absent from most of these lists is, for example, virtue. However, in the philosophical literature, arguments have been put forward that virtue is a central component of flourishing; Aristotle argued that happiness is attained by action in accord with virtue (22). There is a tradition in philosophy of the cardinal virtues: that at the foundation of all of the moral virtues and character strengths lie four fundamental virtues upon which all others depend. These four are sometimes referred to as: prudence or practical wisdom; justice; fortitude or courage; and temperance or moderation (23). Perhaps aspects of fortitude are touched upon in “resilience”; perhaps aspects of temperance in “self-determination”, but what of justice or wisdom? A focus on purely psychological aspects of life misses these.

Also notably absent from the aforementioned list of aspects of psychological flourishing is health. However, health is arguably central to a person’s sense of wholeness and well-being. Possibly some of the reason health is excluded is so as to be able to examine relationships between positive psychological states and subsequent physical health, and indeed there is a reasonably well-established literature that has done this (24–26). Composite measures of psychological well-being might indeed be better predictors of subsequent health than simply using life satisfaction. However, if what is of principal interest is an overall assessment of complete well-being, or flourishing, then health should arguably be included.

Moreover, even if we were to restrict consideration to an assessment of psychological well-being, it is not clear why the composite measures of psychological well-being are preferable to overall self-assessed life satisfaction, as a fundamental assessment for tracking the progress of life. The life satisfaction measure allows an individual to weight the various components of psychological well-being, and other aspects of life, as he or she sees fit. Must one include all of the psychological states above? Someone might not want to give much weight to optimism on the grounds that those who are overly optimistic may be more likely to have a distorted view of reality (27–29). Someone might likewise not want to give much weight to “self-acceptance” because excessive self-acceptance might hinder growth in virtue or character. Life satisfaction measures, in which an individual weights the various aspects of their life as they see fit, might thus be a better summary of psychological well-being.

However, life satisfaction or psychological well-being do not capture all that we would ordinarily mean by flourishing. That flourishing is yet broader seems clear from the possibility that a person may feel satisfied with life, and yet be utterly depraved, or without meaningful social relationships, or entirely dependent upon narcotics. Would we say such persons are flourishing? Something beyond psychology seems to be in view with flourishing. If some notion of flourishing is ultimately of interest, then health itself, along with psychological well-being, and virtue, would all seem to be central components.

Flourishing itself might be understood as a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good. We might also refer to such a state as complete human well-being, which is again arguably a broader concept than psychological well-being. Conceptions of what constitutes flourishing will be numerous and views on the concept will differ. However, I would argue that, regardless of the particulars of different understandings, most would concur that flourishing, however conceived, would, at the very least, require doing or being well in the following five broad domains of human life: (i) happiness and life satisfaction; (ii) health, both mental and physical; (iii) meaning and purpose; (iv) character and virtue; and (v) close social relationships. All are arguably at least a part of what we mean by flourishing. Each of these domains arguably also satisfies the following two criteria: (i) Each domain is generally viewed as an end in itself, and (ii) each domain is nearly universally desired. I would suggest that these two criteria—of being ends and being universally desired—may be useful guides in decisions concerning the domains that should be included in national surveys and polls to assess flourishing.

If, however, we think about flourishing not only as a momentary state but also as something that is sustained over time, then one might also argue that a state of flourishing should be such that resources, financial and otherwise, are sufficiently stable so that what is going well in each of these five domains is likely to continue into the future for some time to come. Financial and material stability would generally not be viewed as ends in themselves but may be important in the preservation of those goods that are their own ends. For flourishing over time, it might thus also be good to assess financial and material stability as well. I would in no way claim that these domains above entirely characterize flourishing. Someone who is religious for example would almost certainly include some notion of communion with God or the transcendent within what is meant by flourishing. I would only argue here that, whatever else flourishing might consist in, these five domains above would also be included, and thus these five domains above may provide some common ground for discussion.

The measurement of well-being in each of these domains is in no way straightforward. Each has a large literature devoted to it (12, 13, 15, 16, 30–33). There will be no perfect measures. However, to make progress, some summary measure seems better than none at all (34). There are of course numerous existing composite measures of psychological well-being (17–21), and some might argue that these should be adequate; but, as noted above, these generally do not capture broader components of flourishing such as health, and often also do not assess virtue. I have, in the Appendix: Flourishing Measures, proposed two summary measures. The first measure includes questions on each of these five domains described above; the second measure, in addition to these five domains, also includes questions on having sufficient stability and financial resources so that flourishing is likely to continue. The former measure is perhaps conceptually more satisfactory as a measure of flourishing, at a given point in time, as each of the domains arguably constitutes its own end. The latter measure, which includes financial and other resources, may be the better measure in practice as it will likely indicate flourishing over a longer stretch of time. For these proposed measures, I have selected two questions in each of these five, or six, domains based principally on prior measures that have some empirical validation and are already used with some frequency in the literature (14, 16, 30, 31, 34–36).

There is of course a certain arbitrary element in the selection of questions and, in some of these domains, such as virtue or meaning, considerable work remains to be done on measure development and validation. An attempt was, however, made to select these questions on principled grounds. It seemed good, whenever possible, to make use of questions that are already being frequently used in surveys, polls, and past research, so as to facilitate comparison when used for evaluative or research purposes. Often these questions used in prior surveys had been subject to some degree of prior empirical validation. Thus, the questions on life satisfaction, positive affect, mental and physical health, and meaningful activities were selected as those already used by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (16), the United Kingdom (34), US General Survey (35), the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (36), and many others. The questions on close social relationships which likewise have been asked regarding prior research, were taken from the Campaign to End Loneliness measure (31). Only the items on character and virtue are entirely newly proposed here, because, although several multiitem measures of specific virtues have been developed (32), there appears to be essentially no literature on more global single-item virtue measures. Any attempt at such assessment is of course only going to be partially adequate. Of the two character–virtue questions in Appendix: Flourishing Measures, the first is intended to provide some assessment of prudence and justice, and the second of fortitude and temperance. I would propose, with no clear way of weighting across domains, to simply sum the scores of each. This too is, of course, not entirely adequate, as, for example, financial resources may play a more important role at levels below the poverty line than in higher ranges. I in no way view this as being the best possible measure, but see it rather as a proposal that might be used until something more satisfactory emerges. The measurement of flourishing using the various domains above could also of course be carried out with alternative or additional questions.

Undoubtedly, the components will be correlated. Mental health is known to be correlated with happiness and life satisfaction (8, 9, 15); a life lived in the pursuit of virtue is likely to give rise to a strong sense of purpose, etc. Nevertheless, the components, although correlated, are still arguably conceptually distinct. Someone, for example, may have a strong sense of purpose, but pursue means that he or she knows to be morally suspect to attain their ends. The components then do arguably assess distinct aspects of flourishing. Further empirical work will be necessary to assess the correlations between the components, and the psychometric properties of the flourishing measures; and the ultimate utility and coherence of the proposal will only be possible to judge positively if it also proves useful empirically in understanding the determinants of flourishing.

Certainly, when feasible, more specific multiitem measures within each of these domains could also be used in research that aims to better understand human flourishing (12, 13, 30–33). Again, single-item measures of constructs like meaning, purpose, and virtue are certainly not entirely satisfactory, and considerable work on measurement in these domains still needs to be carried out. However, the insertion of even single-item measures into surveys or cohort studies can often be leveraged for tremendous benefit in subsequent research studies. My primary purpose in this paper, however, is not principally measurement, but to promote the use of a broader range of outcomes related to flourishing in medicine, public health, psychology, and social science research and to consider what major pathways to flourishing, broadly conceived, may be. It is to this latter topic that we now turn.

Prominent Pathways to Human Flourishing

The public health impact of an exposure is often assessed as a function of (i) how common the exposure is, that is to say, its prevalence, and (ii) the size of its effect. If our focus is to be the uncovering of important pathways to flourishing, one would thus want to focus on aspects of human life that have relatively large effects on each of the five or six domains described above and that are common. From my reading of the empirical literature on these topics, and the suggestions and comments of others (37), I would like to propose here that four major pathways are both relatively common and have reasonably sizeable effects on each of the aforementioned domains of flourishing. The four pathways, which I will subsequently discuss, are family, work, education, and religious community. In what follows, I will review the empirical evidence for each concerning their prevalence and their contributions to the various domains of flourishing. The review of the empirical evidence for how each pathway contributes to each domain of flourishing will be restricted to longitudinal, experimental, and quasiexperimental data and designs. Cross-sectional studies will not be considered. Certainly, there are numerous prior reviews of the correlates of subjective well-being (https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/) (8, 9). However, many reviews on this topic do not clearly differentiate, when summarizing the evidence, between cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, and, in many of these areas, cross-sectional studies constitute the vast majority of the literature. In evaluating evidence for causality, this is problematic, because, for many of these pathways and domains, there is likely to be feedback, with effects in both directions. Cross-sectional designs then cannot in general provide evidence for causality. For example, although religious community may protect against subsequent depression, it is also the case that those who become depressed are more likely to stop participating in religious community (38). Likewise, although it may be the case that marriage makes people happier, it is also the case that happy people are more likely to marry (39). Without longitudinal data, assessing the direction of causality is generally not possible. Ideally, for longitudinal studies to provide evidence for causality, control for prior levels of the outcome under consideration should be made and changes in the exposures being studied should be examined so as to obtain more reliable causal inferences (40).

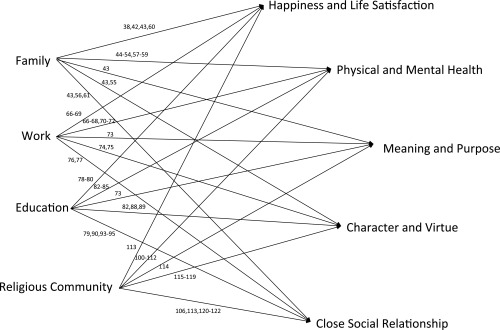

Some of evidence for the effects of each of the four pathways on the flourishing domains is summarized in Fig. 1. Each arrow on this graph is accompanied by a series of references. These references provide evidence from either longitudinal studies with good confounding control, or from randomized trials or quasiexperimental designs, for the corresponding effects. Relations among the pathways themselves, and among the flourishing domains themselves, are not here represented. Each of the five or six domains of flourishing is also likely to have effects on the others. Understanding these too is an important area of empirical research, and considerable progress has been made in studying these relationships as well, for example, how positive affect, life satisfaction, and purpose in life might affect physical health (24–26). Although considerable progress has been made in understanding these relations, much empirical work with longitudinal designs still needs to be done. Our focus here, however, will be on the effects of each of the pathways on the various flourishing domains. However, again, the relations between the pathways and between flourishing domains themselves, and the relevant mechanisms governing these relations, will continue to be important areas of research.

Fig. 1.

Diagram relating pathways to various human flourishing outcomes (with references).

The four pathways that will be considered here—family, work, education, and religious community—are not intended to be exhaustive with respect to major determinants of flourishing. There are of course other pathways—engagement with the arts, for example—that may contribute substantially to a person’s life across the various flourishing domains, but for which regular participation is perhaps not as widespread. Likewise, other forms of community involvement, beyond that found in religious institutions, may positively affect the various flourishing domains, but, in today’s society at least, such participation likewise does not seem particularly common (41). The four pathways upon which I will focus here are common and, as we will see, have powerful effects across the domains of flourishing. The argument here is not that, for any individual, all four must be present for flourishing. Nor is the argument that these four are exhaustive. Rather, it is that these four pathways are important, and common, and that if efforts were made to support, improve, and promote participation in these pathways, the consequences for human flourishing would be substantial.

Let us begin with family. Although not universal, the vast majority of children grow up in some type of family context. Moreover, although marriage rates have been declining, marriage continues to be a very common phenomena with ∼80% of Americans aged 25 and older, at some point in time, having been married (42) and thereby having formed a family structure beyond their family of origin. Participation in family life is thus a very common experience. The effects of family life, and of marriage, are profound. The vast majority of studies on marriage and happiness or life satisfaction are cross-sectional. However, the existing longitudinal studies indicate, like the cross-sectional studies, that marriage is associated with higher life satisfaction (39, 43) and greater affective happiness (44). Evidence moreover suggests that marriage is associated with better mental health, physical health, and longevity, even controlling for baseline health (45–55). Concerning character and virtue, although understudied and current outcome measures are inadequate, there is longitudinal evidence that marriage is associated with higher level of personal growth (44), and with a reduction in crime for those at high risk (56). It is also associated with higher levels of meaning and purpose in life (44). Marriage is moreover associated longitudinally with higher levels of positive relationships with others, higher levels of perceived social support, and lower levels of loneliness (44, 57). Marriage likewise tends to be associated with better financial outcomes, even controlling for baseline financial status and education (45).

Conversely, divorce is associated longitudinally with poorer mental and physical health outcomes, even controlling for baseline health (44, 49, 51, 52, 55, 58–60), lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction (44, 61), lower levels of meaning and purpose in life (44), lower levels of positive relations with others (44), poorer relationships between children and parents (62), and greater levels of poverty for both children and mothers (45).

Marriage also has profound effects on the lives of children. Children within, rather than outside of, marriage are more likely to have better mental and physical health, to be happier in childhood and later in life, are less likely to engage in delinquent and criminal behaviors, are more likely to have better relationships with their parents, and are themselves less likely to later divorce (45, 47, 57, 63–65).

The effects of marriage on health, happiness and life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, close social relationships, and financial stability are thus profound. Divorce, in contrast, has adverse effects on all of these outcomes. Although there may be instances in which tensions between married partners seem irreconcilable, the evidence on marriage and divorce suggests that, if interventions were perhaps available earlier in the relationship, when problems first began to develop, the consequences for the flourishing of both the spouses and their children could be substantial. We will return to this point below. Marriage and family thus appear to be an important pathway to flourishing.

We will now consider work and employment as pathways to flourishing. Approximately 81% of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population aged 25–54 is employed, including about 88% of men and 73% of women (66). Relatively high proportions, for both genders, thus have some form of employment; moreover, the effects of employment on a number of outcomes are fairly pronounced. Metaanalyses suggest that those who are employed have higher levels of life satisfaction and of family or marital satisfaction, and better mental and physical health (67, 68). Longitudinal studies also indicate that reemployment of the unemployed results in improvement in life satisfaction, and in self-reported physical health and mental health, and further indicates that loss of a job results in reductions in mental health and in life satisfaction (67–71). Interventions to provide employment have been found, in randomized trials, to have effects on quality of life, better mental health, and fewer hospitalizations, even among those with severe mental health problems at baseline (72, 73). There is some evidence that past work and education experiences explain some of the variation in purpose in life (74), but rigorous longitudinal studies are still needed. The relationship between employment and crime is complex and likely bidirectional, because those with criminal records have more difficulty obtaining employment, but there is some, albeit not conclusive, evidence that vocational training programs reduce crime (75, 76). With regard to social relationships, longitudinal studies, and even a randomized trial of a vocational training program, suggest that employment increases the likelihood of marriage (77). Longitudinal studies likewise suggest that unemployment renders divorce more likely for most groups (78). Employment is of course a source of income and financial stability.

Let us turn now to education. Some form of education is of course a near-universal phenomenon, but the extent varies considerably across people and populations. There is reasonably good evidence that higher levels of education are longitudinally associated with higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction (79–81). Although cross-sectional analyses that control for many covariates at once sometimes suggest no association, or even a negative association (80), such analyses typically control for income, employment, and marital status, which may be the primary pathways. Longitudinal analyses that take this temporal ordering into account suggest an effect of education on higher happiness and life satisfaction through these pathways (79, 80). Education is a strong cross-sectional predictor of health (82, 83), but the extent to which this is causal is debated. Although some longitudinal and quasiexperimental designs do indicate a protective effect (83–86), other strong designs suggest that this effect may be more modest than may have been previously thought, or may not apply to all contexts (83, 87, 88), with possibly a larger effect in the United States than in Europe (83). Concerning virtue and character, there is some evidence from longitudinal studies that education decreases the likelihood of criminal activity and increases the likelihood of voting and of democratic participation (83, 89, 90). There is some evidence that past education and work experiences explain some of the variation in purpose in life (74), but rigorous longitudinal studies are still needed. Higher levels of education are associated with subsequently higher levels of club membership, participation, and social interaction (91). Concerning marriage, there is some evidence that education may delay the timing of first marriage (92, 93) but increases the overall likelihood of marriage (80, 94, 95), and decreases the likelihood of subsequent divorce (96). Education can of course strongly affect subsequent income (97–99).

We will conclude our consideration of the four pathways with religious community. Approximately 84% of the world’s population report a religious affiliation (100). Within the United States, 89% believe in God or a universal spirit, 78% consider religion a very important or fairly important part of life, 79% identify with a particular religious group, and 36% report having attended a religious service in the last week (101). Not only is participation substantial, but there is now fairly good evidence that participation in religious community is longitudinally associated with the various domains of flourishing. There is a large literature suggesting that attending religious services is associated with better health (102–104). Although much of the literature is methodologically weak, there are now numerous well-designed longitudinal studies that suggest that regular religious service attendance is associated with greater longevity (105–110), a 30% lower incidence of depression (38, 107, 111), a fivefold lower rate of suicide (112), better survival from cancer, and numerous other outcomes (102, 104). Importantly, the evidence suggests that it is attending religious services, rather than private practices or self-assessed spirituality or religiosity, that is most strongly predictive of health (106, 113). It is the communal form of religious practice that appears to bring about better health outcomes. Numerous studies have also demonstrated an association between attending services and happiness and life satisfaction; almost all of these are cross-sectional, but the existing longitudinal evidence offers confirmation of this and suggests that it may be causal (114). There is likewise some evidence from longitudinal studies that service attendance is associated with greater meaning in life (115). With the relationship between religion and virtue, once again, many of the studies use cross-sectional designs. However, there have been a number of randomized priming experiments suggesting at least short-term effects of religious prompts on prosocial behavior (116). There is longitudinal evidence that those who attend services are subsequently more generous and more civically engaged (117). There is also some experimental evidence that encouragement to prayer increases forgiveness, gratitude, and trust (118–120). Finally, concerning close relationships, there is evidence from longitudinal studies that attending religious services decreases the likelihood of divorce (107, 121, 122), increases the likelihood of subsequently making new friends, and of marrying, and increases social support (107, 114, 123). The effect of religious community, and specifically religious service attendance, on these various aspects of flourishing, is thus substantial.

On the Promotion of Human Flourishing

If it is the case that the family, work, education, and religious community are important determinants of various aspects of human flourishing, as indeed they seem to be, then this has profound implications for societal organization and resource allocation. If we desire societal good, broadly construed as human flourishing, and crudely represented by the measures described above, then the structures, policies, laws, and incentives, financial or otherwise, that contribute to family, work, education, and religious community will likely be important ways in which society itself can better flourish.

Policies can be put into place to support marriage; current marriage penalties for the poor embedded within the welfare system should be eliminated (6, 7); resources could be expanded to assist and support those with marital conflict. Randomized trials of certain online marriage support programs have been shown to have important effects on relationship confidence and satisfaction, and on individual functioning and mental health (2), and the potential for outreach of these is considerable. Concerning employment, welfare policy could be structured so as to not disincentivize work. Supportive employment programs could be established for vulnerable populations. Such supportive employment interventions have been found, in randomized trials, to have effects on competitive employment, health, and quality of life, even for mentally ill and homeless populations (3, 4, 72, 73). Education that ensures both adequate school resources and devoted competent teachers, for all students, would of course both contribute toward employment and income (5), as well as also further promote the various domains of flourishing. With respect to religious community as a pathway, society could continue to preserve and promote the tax-exempt status of these organizations so as to facilitate their important contributions. The regular media portrayals of various negative aspects of religion can and should be balanced with the numerous ways, documented above, in which religious community and service attendance promotes health, well-being, and human flourishing. Further discussion of these issues could be included within public health and health care.

With respect to research, if empirical studies are to better promote human flourishing, several implications would seem to follow. First, broad human flourishing outcome measures, rather than just specific disease outcomes, should be the focus of more empirical research studies, and should be incorporated into more designs so as to better understand the causes and determinants of, and interventions to promote, human flourishing. Moreover, outcomes such as meaning and purpose or character and virtue should not simply be viewed as being justified because of their relations with physical health, but also as ends in themselves. Second, it would be good to examine multiple outcomes simultaneously rather than the common practice of only examining single individual outcomes (10). That is not to say that specific outcomes and individual diseases ought to be neglected, but simply that the balance should shift. Third, research resources, both human and financial, would perhaps be better allocated to allow for more of a balance across broader human flourishing outcomes measures, versus more narrow, but still important, specific disease outcomes. A shift along these lines would have important implications for government funding agencies, student dissertation choices, and departmental hiring and promotion decisions. These institutional decisions concerning resource allocation and hiring have profound effects on the content of research and could be better balanced so that more research on broader aspects of human flourishing takes place. Fourth, it is unfortunate that with topics as important as these, so much of the existing research continues to be with cross-sectional data, which, as noted above, severely compromise our ability to reason about causality or to assess determinants. Incorporation of broader flourishing measures into existing longitudinal cohort studies could help address this, as would greater research funding for these topics. Finally, governments could begin to collect data on broader outcome measures and to track and measure progress not only on gross domestic product but on various other measures of well-being and flourishing (8), including meaning and purpose, and perhaps even character and virtue. Self-reported measures of character and virtue of course have their weaknesses, but there is some evidence that they do bear some relation to other, potentially more objective measures of character (124). Some progress in this regard has already been made. Bhutan rather famously put forward the idea of a Gross National Happiness Index. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development now collects data on measures such as of life satisfaction, health, individual financial security, and meaningful and purposeful activity for each of the participant nations (16). Recently, the United Kingdom began collecting such data on several of these measures in their annual population survey (34). The incorporation of such measures into government surveys can both alter discourse about policy priorities, and also prove useful in research. As noted above, although not entirely adequate, the insertion of even single-item measures of the flourishing domains into surveys could be leveraged for important research purposes.

The focus of this essay has been on individual pathways to personal flourishing, that is, on decisions or actions an individual might take to flourish. However, a well-functioning government and society, with sufficient material resources, is of course also crucial in sustaining the pathways described above that promote individual flourishing. An efficient and effective government, a well-functioning financial system, the absence of corruption, and civic stability are all important in supporting families, work, education, and religious communities in the promotion of individual flourishing; and the study of how more macro- and state-level factors influence individual flourishing is needed as well. However, the relevant effects here are arguably in both directions. The state of government and the policies it undertakes will influence individual flourishing. However, individual health, relationships, life satisfaction, purpose, and, perhaps especially, virtue will likely also contribute to the strengthening of the institutions that allow a society to thrive. A deeper consideration of, focus on, and understanding of outcomes such as purpose, and virtue, moving beyond measures of only income or health, may contribute not only to a broader and more profound individual flourishing, but also to a better functioning society as well.

Appendix: Flourishing Measures

The “Flourish” measure is obtained by summing the scores from each of the first five domains. The “Secure Flourish” measure is obtained by summing the scores from all six domains including the financial and material stability domain. Each of the questions is assessed on a scale of 0–10.

Domain 1: Happiness and Life Satisfaction.

Overall, how satisfied are you with life as a whole these days?

0 = Not Satisfied at All, 10 = Completely Satisfied

In general, how happy or unhappy do you usually feel?

0 = Extremely Unhappy, 10 = Extremely Happy

Domain 2: Mental and Physical Health.

In general, how would you rate your physical health?

0 = Poor, 10 = Excellent

How would you rate your overall mental health?

0 = Poor, 10 = Excellent

Domain 3: Meaning and Purpose.

Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?

0 = Not at All Worthwhile, 10 = Completely Worthwhile

I understand my purpose in life.

0 = Strongly Disagree, 10 = Strongly Agree

Domain 4: Character and Virtue.

I always act to promote good in all circumstances, even in difficult and challenging situations.

0 = Not True of Me, 10 = Completely True of Me

I am always able to give up some happiness now for greater happiness later.

0 = Not True of Me, 10 = Completely True of Me

Domain 5: Close Social Relationships.

I am content with my friendships and relationships.

0 = Strongly Disagree, 10 = Strongly Agree

My relationships are as satisfying as I would want them to be.

0 = Strongly Disagree, 10 = Strongly Agree

Domain 6: Financial and Material Stability.

How often do you worry about being able to meet normal monthly living expenses?

0 = Worry All of the Time, 10 = Do Not Ever Worry

How often do you worry about safety, food, or housing?

0 = Worry All of the Time, 10 = Do Not Ever Worry

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.World Health Association 1948. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization. International Health Conference (World Health Association, New York), Official Records of the World Health Organization, No 2, p 100.

- 2.Doss BD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the web-based OurRelationship program: Effects on relationship and individual functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:285–296. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashner TM, et al. Impact of work therapy on health status among homeless, substance-dependent veterans: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:938–944. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modini M, et al. Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the international evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:14–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.165092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chetty R, Friedman J, Rockoff J. Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. Am Econ Rev. 2014;104:2633–2679. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rand S. The real marriage penalty: How welfare law discourages marriage despite public policy statements to the contrary—and what can be done about it. The University of the District of Columbia Law Review. 2015;18:93–143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox WB, Price JP, Rachidi A. Marriage Penalized. Does Social-Welfare Policy Affect Family Formation? Institute for Family Studies; Charlottesville, VA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diener E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000;55:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seligman MEP. Flourish. Atria; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.VanderWeele TJ. Outcome-wide epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2017;28:399–402. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantril H. The Pattern of Human Concerns. Rutgers Univ Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46:137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fordyce MW. A review of research on the happiness measures: A sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Soc Indic Res. 1988;20:355–381. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Research Council . Subjective Well-Being. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.OECD . OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB. A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19) Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:186–194. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diener E, et al. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97:143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huppert FA, So TTC. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc Indic Res. 2013;110:837–861. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su R, Tay L, Diener E. The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) and the brief inventory of thriving (BIT) Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2014;6:251–279. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aristotle (1925) The Nicomachean Ethics (Oxford University Press, Oxford)

- 23.Pieper J. The Four Cardinal Virtues. University of Notre Dame Press; Notre Dame IN: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2016;78:122–133. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Han B. Positive affect and mortality risk in older adults: A meta-analysis. PsyCh J. 2016;5:125–138. doi: 10.1002/pchj.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein ND, Klein WM. Unrealistic optimism: Present and future. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1996;15:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dienstag JF. Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scruton R. The Uses of Pessimism: And the Danger of False Hope. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prawitz AD, et al. InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation. J Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campaign to End Loneliness 2015 Measuring Your Impact on Loneliness in Later Life. Available at https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Loneliness-Measurement-Guidance1.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 32.Peterson C, Seligman ME. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53:80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allin P, Hand DJ. New statistics for old?—measuring the wellbeing of the UK. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2017;180:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35. NORC (2017) General Social Survey (GSS). Available at www.norc.org/research/projects/pages/general-social-survey.aspx. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 36. WHO (2017) The World Health Organization World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO WMH-CIDI). Available at https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi/. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 37.McHugh P, Chisolm M. 2013 Psychiatry and Human Flourishing. Available at www.hopkinsmedicine.org/psychiatry/education/flourishing/images/Grand%20Rounds_Human_Flourishing.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 38.Li S, Okereke OI, Chang S-C, Kawachi I, VanderWeele TJ. Religious service attendance and lower depression among women—a prospective cohort study. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50:876–884. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9813-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stutzer A, Frey BS. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? J Socio Econ. 2006;35:326–347. [Google Scholar]

- 40.VanderWeele TJ, Jackson JW, Li S. Causal inference and longitudinal data: A case study of religion and mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:1457–1466. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pew Research Center 2014 Record Share of Americans Have Never Married. Available at www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/09/24/record-share-of-americans-have-never-married/. Accessed October 24, 2016.

- 43.Uecker JE. Marriage and mental health among young adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53:67–83. doi: 10.1177/0022146511419206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marks NF, Lambert JD. Marital status continuity and change among young and midlife adults longitudinal effects on psychological well-being. J Fam Issues. 1998;19:652–686. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilcox WB. Why Marriage Matters: 30 Conclusions from the Social Sciences. 3rd Ed Institute for American Values/National Marriage Project; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson CM, Oswald AJ. 2005. How Does Marriage Affect Physical and Psychological Health? A Survey of the Longitudinal Evidence (The Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn, Germany), IZA Bonn Discussion Paper, No 1619.

- 47.Wood RG, Goesling B, Avellar S. The Effects of Marriage on Health: A Synthesis of Recent Research Evidence. Mathematica Policy Research; Princeton: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horwitz AV, White HR, Howell-White S. Becoming married and mental health: A longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. J Marriage Fam. 1996;58:895–907. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HK, McKenry P. The relationship between marriage and psychological well-being. J Fam Issues. 2002;23:885–911. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lamb KA, Lee GR, DeMaris A. Union formation and depression: Selection and relationship effects. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65:953–962. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon RW. Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. AJS. 2002;107:1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lillard LA, Panis CWA. Marital status and mortality: The role of health. Demography. 1996;33:313–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams K, Umberson D. Marital status, marital transitions, and health: A gendered life course perspective. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:81–98. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manzoli L, Villari P, M Pirone G, Boccia A. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan RM, Kronick RG. Marital status and longevity in the United States population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:760–765. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sampson RJ, Laub JH, Wimer C. Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects. Criminology. 2006;44:465–508. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waite LJ, Gallagher M. The Case for Marriage. Doubleday; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aseltine RH, Jr, Kessler RC. Marital disruption and depression in a community sample. J Health Soc Behav. 1993;34:237–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women’s midlife health. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:111–125. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shor E, Roelfs DJ, Bugyi P, Schwartz JE. Meta-analysis of marital dissolution and mortality: Reevaluating the intersection of gender and age. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams K. Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:470–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zill N, Morrison DR, Coiro MJ. Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. J Fam Psychol. 1993;7:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing Up with a Single Parent. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amato PR, Sobolewski JM. The effects of divorce and marital discord on adult children’s psychological well-being. Am Sociol Rev. 2001;66:900–921. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maier EH, Lachman ME. Consequences of early parental loss and separation for health and well-being in midlife. Int J Behav Dev. 2000;24:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015 Household data annual averages. 11b. Employed persons by detailed occupation and age. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11b.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 67.McKee-Ryan F, Song Z, Wanberg CR, Kinicki AJ. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90:53–76. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74:264–282. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waddell G, Burton AK. Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being? The Stationary Office; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lucas RE, Clark AE, Georgellis Y, Diener E. Unemployment alters the set point for life satisfaction. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01501002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rueda S, et al. Association of returning to work with better health in working-aged adults: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:541–556. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoffmann H, Jäckel D, Glauser S, Mueser KT, Kupper Z. Long-term effectiveness of supported employment: 5-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:1183–1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13070857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Rijn RM, Carlier BE, Schuring M, Burdorf A. Work as treatment? The effectiveness of re-employment programmes for unemployed persons with severe mental health problems on health and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:275–279. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-103121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryff CD, Heidrich SM. Experience and well-being: Explorations on domains of life and how they matter. Int J Behav Dev. 1997;20:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson DB, Gallagher CA, MacKenzie DL. A meta-analysis of corrections-based education, vocation, and work programs for adult offenders. J Res Crime Delinq. 2000;37:347–368. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raphael S, Winter-Ebmer R. Identifying the effect of employment on crime. J Law Econ. 2001;44:259–283. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mamun AA. Effects of Employment on Marriage: Evidence from a Randomized Study of the Job Corps Program. Final Report. Mathematica Policy Research Center; Princeton: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sayer LC, England P, Allison PD, Kangas N. She left, he left: How employment and satisfaction affect women’s and men’s decisions to leave marriages. AJS. 2011;116:1982–2018. doi: 10.1086/658173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cunado J, de Gracia FP. Does education affect happiness? Evidence for Spain. Soc Indic Res. 2012;108:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Powdthavee N, Lekfuangfub WN, Wooden M. What’s the good of education on our overall quality of life? A simultaneous equation model of education and life satisfaction for Australia. J Behav Exp Econ. 2015;54:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oreopoulos P, Salvanes KG. Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. J Econ Perspect. 2011;25:159–184. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cutler DM, Llera-Muney A. 2006 Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence. National Poverty Center Working Paper Series No 06-19. Available at www.npc.umich.edu/publications/workingpaper06/paper19/working-paper06-19.pdf.

- 83.Lochner L. 2011 Non-production Benefits of Education: Crime, Health, and Good Citizenship. NBER Working Paper 16722. Available at www.nber.org/papers/w16722.

- 84.Ludwig J, Miller DL. Does Head Start improve children’s life chance? Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Q J Econ. 2007;122:159–208. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawachi I, Adler NE, Dow WH. Money, schooling, and health: Mechanisms and causal evidence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:56–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grossman M. The relationship between health and schooling: What’s new? Nordic J Health Econ. 2015;3:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clark D, Royer H. The effect of education on adult mortality and health: Evidence from Britain. Am Econ Rev. 2013;103:2087–2120. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dobbie W, Fryer RG. The medium-term impacts of high-achieving charter schools. J Polit Econ. 2015;123:985–1037. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lochner L, Moretti E. The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94:155–189. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dee TS. Are there civic returns to education? J Public Econ. 2004;88:1697–1720. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Helliwell JF, Putnam RD. Education and social capital. East Econ J. 2007;33:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ikamari LDE. The effect of education on the timing of marriage in Kenya. Demogr Res. 2005;12:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gangadharan L, Pushkar M. 2001 The Effect of Education on the Timing of Marriage and First Birth in Pakistan. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc, 2001. Available at https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/41483/6/gangadharan_maitra.pdf.

- 94.Clarkberg M. The price of partnering: The role of economic well-being in young adults’ first union experiences. Soc Forces. 1999;77:945–968. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sweeney MM. Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. Am Sociol Rev. 2002;67:132–147. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kreager DA, Felson RB, Warner C, Wenger MR. Women’s education, marital violence, and divorce: A social exchange perspective. J Marriage Fam. 2013;75:565–581. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Psacharopoulos G. Returns to investment in education: A global update. World Dev. 1994;22:1325–1343. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harmon C, Oosterbeek H. The returns to education: Microeconomics. J Econ Surv. 2003;17:115–155. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carneiro P, Heckman JJ, Vytlacil E. Estimating marginal returns to education. Am Econ Rev. 2011;101:2754–2781. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.6.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pew Research Center 2012 The Global Religious Landscape. Available at www.pewforum.org/files/2014/01/global-religion-full.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 101. Gallup (2015–2016) Religion. Available at www.gallup.com/poll/1690/religion.aspx. Accessed July 28, 2016.

- 102.Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. 2nd Ed Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Idler EL, editor. Religion as a Social Determinant of Public Health. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 104.VanderWeele TJ. Religion and health: A synthesis. In: Balboni MJ, Peteet JR, editors. Spirituality and Religion Within the Culture of Medicine: From Evidence to Practice. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2017. pp. 357–402. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, Ellison CG. Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography. 1999;36:273–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Musick MA, House JS, Williams DR. Attendance at religious services and mortality in a national sample. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:198–213. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Cohen RD, Kaplan GA. Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:68–74. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gillum RF, King DE, Obisesan TO, Koenig HG. Frequency of attendance at religious services and mortality in a U.S. national cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. A systematic quantitative review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:81–90. doi: 10.1159/000190791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li S, Stampfer MJ, Williams DR, VanderWeele TJ. Association between religious service attendance and mortality among women. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:777–785. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Balbuena L, Baetz M, Bowen R. Religious attendance, spirituality, and major depression in Canada: A 14-year follow-up study. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:225–232. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.VanderWeele TJ, Li S, Tsai AC, Kawachi I. Association between religious service attendance and lower suicide rates among US women. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:845–851. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.VanderWeele TJ, et al. Attendance at religious services, prayer, religious coping, and religious-spiritual identity as predictors of all-cause mortality in the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:515–522. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lim C, Putnam RD. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. Am Sociol Rev. 2010;75:914–933. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Krause N, Hayward RD. Religion, meaning in life, and change in physical functioning during late adulthood. J Adult Dev. 2012;19:158–169. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shariff AF, Willard AK, Andersen T, Norenzayan A. Religious priming: A meta-analysis with a focus on prosociality. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2016;20:27–48. doi: 10.1177/1088868314568811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Putnam RD, Campbell DE. American Grace. Simon and Schuster; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lambert NM, Fincham F, Braithwaite SR, Graham S, Beach S. Can prayer increase gratitude? Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2009;1:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF, Graham SM, Beach SR. Motivating change in relationships: Can prayer increase forgiveness? Psychol Sci. 2010;21:126–132. doi: 10.1177/0956797609355634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Lavallee DC, Brantley CW. Praying together and staying together: Couple prayer and trust. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2012;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Call VRA, Heaton TB. Religious influence on marital stability. J Sci Study Relig. 1997;36:382–392. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Amato PR, Rogers SJ. A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. J Marriage Fam. 1997;59:612–624. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wilcox WB, Wolfinger NH. Soul Mates: Religion, Sex, Love, and Marriage Among African Americans and Latinos. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fowers BJ. Toward programmatic research on virtue assessment: Challenges and prospects. Theory Res Educ. 2014;12:309–328. [Google Scholar]