Significance

This study addresses a topological paradox in Ca2+ signaling mediated by cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR). The messenger is synthesized by CD38, thought to be a type ll ectoenzyme. Instead, we show that it exists naturally in two opposite membrane orientations and that the type III, with its catalytic domain facing the cytosol, is active in producing cellular cADPR. Its topology was resolved by a technique simultaneously targeting dual epitopes for protein identification, which identifies the intracellular type III CD38 unambiguously. It is also shown that its cADPR-synthesizing activity is regulated by cytosolic interactions with Ca2+ and integrin-binding protein 1 (CIB1). The results indicate that membrane proteins are not necessarily expressed with only one unique membrane orientation set by sequence motifs as generally believed.

Keywords: CD38, cyclic ADP-ribose, membrane topology, calcium signaling, CIB1

Abstract

CD38 catalyzes the synthesis of the Ca2+ messenger, cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR). It is generally considered to be a type II protein with the catalytic domain facing outside. How it can catalyze the synthesis of intracellular cADPR that targets the endoplasmic Ca2+ stores has not been resolved. We have proposed that CD38 can also exist in an opposite type III orientation with its catalytic domain facing the cytosol. Here, we developed a method using specific nanobodies to immunotarget two different epitopes simultaneously on the catalytic domain of the type III CD38 and firmly established that it is naturally occurring in human multiple myeloma cells. Because type III CD38 is topologically amenable to cytosolic regulation, we used yeast-two-hybrid screening to identify cytosolic Ca2+ and integrin-binding protein 1 (CIB1), as its interacting partner. The results from immunoprecipitation, ELISA, and bimolecular fluorescence complementation confirmed that CIB1 binds specifically to the catalytic domain of CD38, in vivo and in vitro. Mutational studies established that the N terminus of CIB1 is the interacting domain. Using shRNA to knock down and Cas9/guide RNA to knock out CIB1, a direct correlation between the cellular cADPR and CIB1 levels was demonstrated. The results indicate that the type III CD38 is functionally active in producing cellular cADPR and that the activity is specifically modulated through interaction with cytosolic CIB1.

Cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) is a second-messenger molecule regulating the endoplasmic Ca2+ stores in a wide range of cells spanning three biological kingdoms (1–4). Equally widespread is the enzyme activity that cyclizes nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide (NAD) to produce cADPR (5). The first fully characterized enzyme was the ADP-ribosyl cyclase, a small soluble protein in Aplysia (6). It was thus surprising that the soluble cyclase shows sequence homology with the carboxyl (C-) domain of a mammalian membrane protein, CD38, a surface antigen first identified in lymphocytes (7). Subsequent work shows that CD38 is indeed a novel enzyme catalyzing not only the synthesis of cADPR but its hydrolysis to ADP-ribose as well (8, 9). Gene ablation studies establish that CD38 is the dominant enzyme in mammalian tissues responsible for metabolizing cADPR and is important in regulating diverse physiological functions, ranging from neutrophil chemotaxis to oxytocin release and insulin secretion (10–12).

It is generally believed that CD38 is a type II protein with a single transmembrane segment and a short amino(N)-tail of 21 residues extending into the cytosol, whereas the major portion of the molecule, its catalytic C-domain, is facing outside (13). This membrane topology seems paradoxical to CD38 functioning as a signaling enzyme producing an intracellular messenger. A vesicular mechanism has been proposed, positing that CD38 can be endocytosed, together with transport proteins, into endolysosomes. The transporters can then mediate the influx of substrates for CD38 and efflux of cADPR from the endolysosomes to act on the endoplasmic Ca2+ stores (14, 15).

Recently, we have shown that CD38, in fact, can exist in two opposite membrane orientations, not only in the expected type II orientation but also in the opposite type III orientation, with the catalytic C-domain facing the cytosol (16). We further establish that the most critical determinants of the topology are the positive charges in the tail next to the transmembrane segment (17). The type III CD38 is fully active in raising the cADPR levels in cells. In this study, we developed a dual-epitope protein identification (DepID) method with high specificity and sensitivity for type III CD38. With it, we confirmed and quantified the intracellular type III CD38 in human multiple myeloma cells. Its regulation was explored using yeast-two-hybrid screening. A cytosolic protein, Ca2+ and integrin-binding protein 1 (CIB1), was identified and shown to interact specifically with the catalytic C-domain of the type III CD38. We further showed that the type III CD38 is functionally active in producing cellular cADPR, the levels of which directly correlate with the CIB1 levels. The results substantiate the type III signaling mechanism of CD38 (1, 18).

Results

Development of a DepID Assay for Type III CD38.

We have advanced the notion that CD38 exists naturally in both type II and type III orientations, resolving the topological issue surrounding its enzymatic synthesis of the intracellular messenger molecule cADPR. We have shown that mutating the positively charged residues in the N-terminal tail segment of the molecule to negative changes the membrane orientation of CD38 from type II, expressing on the cell surface, to type III, which is localized mostly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (16, 17). An important point that remains to be established is that the intracellular type III CD38 is naturally present in cells.

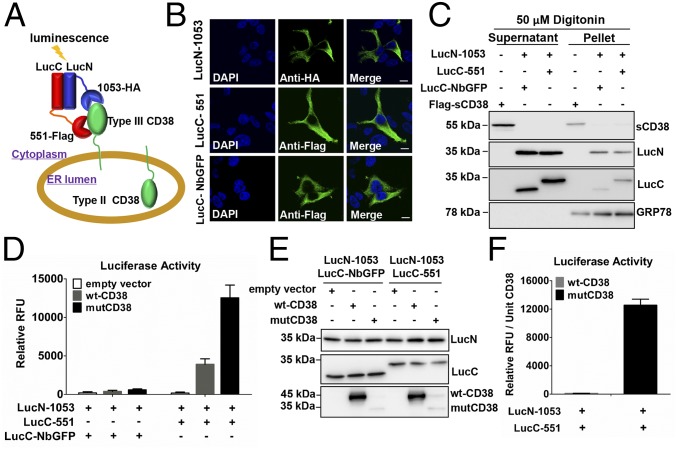

It is anticipated that the abundance of type III CD38 in cells would be much lower than the abundance of dominant type II, obligating the development of a new method for detection with high sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, the method must be able to distinguish its membrane topology definitively. The design of such a method is diagrammed in Fig. 1A. Type III CD38 in the ER should have its catalytic-terminal domain facing the cytosol. We targeted two separate epitopes on the C-domain simultaneously using two different nanobodies (Nb-1053 and Nb-551) that we have previously generated (19) (Fig. S1). Crystallography identifies a 3D array of 22 or 23 different residues comprising each epitope (19), making the combination unique to the protein (CD38) that possesses both. The nanobodies were fused with the N-terminal (LucN) or C-terminal (LucC) fragment of Gaussia princeps luciferase, respectively. Simultaneous binding of the two nanobodies to the same C-domain of the CD38 molecule allows the two complementing luciferase fragments to get close enough to reconstitute an active enzyme, producing luminescence in the presence of the substrate coelenterazine (20). This approach of using dual epitopes for protein identification (DepID) ensures high specificity, whereas the luminescence detection provides the high sensitivity required.

Fig. 1.

Detection of type III CD38 in HEK293 cells by the DepID assay. (A) Schematic diagram of the DepID assay for type III CD38. Cytosolic probes were constructed by splicing luciferase fragments (LucN or LucC) to nanobodies (1053 or 551) targeting two different epitopes of the C-domain of CD38. Simultaneous binding of both probes to the same type III CD38 reconstitutes the active luciferase and produces luminescence. (B) Confocal fluorescence micrographs of HEK293 cells expressing HA-tagged LucN-1053, Flag-tagged LucC-551, or LucC-NbGFP and stained with anti-HA or anti-Flag. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (C) Release of the DepID probes by membrane permeabilization. HEK293 cells stably expressing DepID probes or Flag-sCD38 (a cytosolic control) were permeabilized by 50 μM digitonin, and the supernatant and pellet were analyzed by Western blot, with GRP78 as an ER control. (D) DepID assay in HEK293 cells. The cells stably expressing DepID probes were transfected with wt-CD38, mutCD38, or empty vector, separately. Luminescence [relative fluorescent units (RFU)] was measured after addition of 20 μM coelenterazine. (E) Expression of DepID probes and CD38 in the cells indicated in D was measured by Western blots. (F) Luminescence was normalized to the CD38 amounts in the corresponding cells.

Fig. S1.

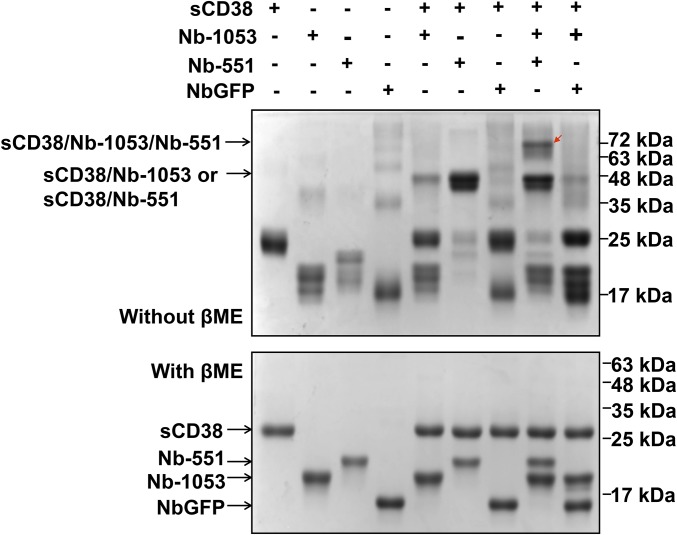

Cross-link of Nb-1053, Nb-551, and sCD38. NbGFP acts as a negative control. Proteins, as indicated in each lane, were incubated with 1 mM dithiobis [succinimidylpropionate] (DSP) for 1 h at room temperature and quenched with 25 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.4) for 15 min to remove unreacted DSP. The samples were separated into two parts, and SDS loading buffer was added for PAGE with (Lower, de–cross-linked as loading controls) or without (Upper) β-mercaptoethanol (βME). The triple-protein complex was observed in lane 8 (red arrow, Upper) in the presence of Nb-1053, Nb-551, and sCD38, but not in lane 9 (Upper) with substitution of Nb-551 by NbGFP.

The topological determinant of the method resides in the cytosolic expression of the Luc-Nb probes, which dictates that only the type III CD38 with its C-domain facing the cytosol can be detected. The amino acid sequences of the designed probes were analyzed with “topology prediction” tools (www.expasy.org/tools) to ensure that there was no potential organelle-targeting signal in the sequence. The constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells. As shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S2, the cytosolic expression of the probes was verified by immunofluorescence microscopy using antibodies against the tags in the probes (HA or Flag; Fig. 1 A and B). Further support came from digitonin treatment that permeabilized the plasma membrane, resulting in the release of most of the cytosolic probes to the supernatants (Fig. 1C). In contrast, GRP78, an ER lumen protein, was retained in the pellets. As a positive control, cells expressing a soluble form of CD38 (sCD38) likewise released most of the molecule to the supernatant after digitonin permeabilization.

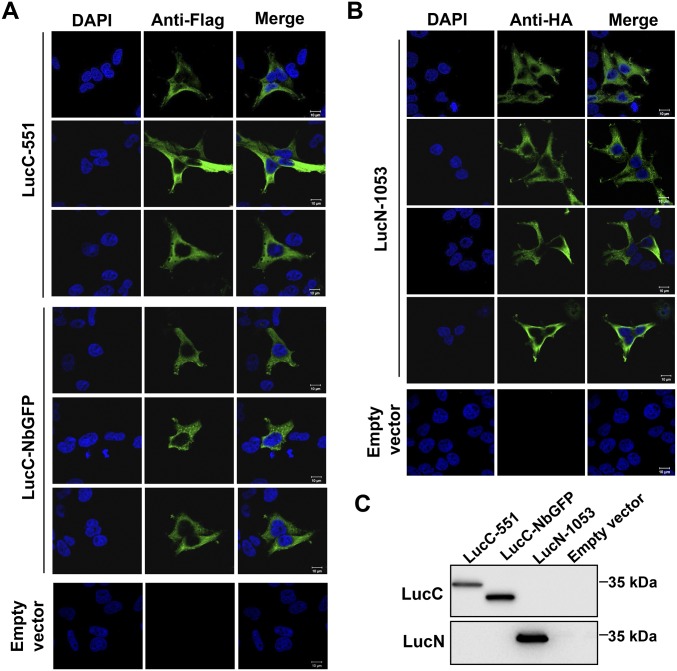

Fig. S2.

(A and B) More micrographs as in Fig. 1B. (C) Expression of LucC-551, LucC-NbGFP, or LucN-1053 in HEK293 cells was analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA or anti-Flag. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

The method was then applied to the HEK293 cells expressing type III mutant CD38 (mutCD38; Fig. 1 D–F) that was constructed by mutating the positive residues in the N-terminal tail sequence to negative (16). The cells also contained the DepID luciferase probes. As shown in Fig. 1D, large luminescence signals were detected, indicating the binding of the two probes to the type III CD38 and reconstituting the active luciferase. As a negative control, one of the probes (LucC-551) was replaced with one containing a nanobody against an irrelevant protein, GFP (LucC-NbGFP; Fig. 1E, Middle, lanes 1–3), and no luminescence was detected (Fig. 1D), even though the amounts of luciferase probes expressed in all of the cells were essentially identical (Fig. 1E). The results indicate that the simultaneous binding of two probes to the same type III CD38 molecule is required for generating the luminescence. Likewise, control cells not expressing CD38 (empty vector; Fig. 1E) also produced no luminescence (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1D also shows that cells overexpressing large amounts of wild-type CD38 (wt-CD38) compared with mutCD38 (Fig. 1E) produced only very modest luminescence signals. This result was not due to variation in the amount of probes expressed, because the amounts were essentially identical in all cells (Fig. 1E). The results are consistent with the fact that wt-CD38 is known to be mainly expressed on the cell surface as a type II protein (21). When normalized to the amounts of CD38 expressed, it can be seen (Fig. 1F) that cells expressing mutCD38 produced more than 100-fold luminescence signal compared with cells expressing wt-CD38. These results verify that the DepID method is highly specific for type III CD38 and has high sensitivity. That cells transfected with a wt-CD38 construct could produce modest luminescence indicates that significant amounts of type III CD38 are normally coexpressed and coexist with type II CD38.

Endogenous Type III CD38 Exists in Multiple Myeloma Cells.

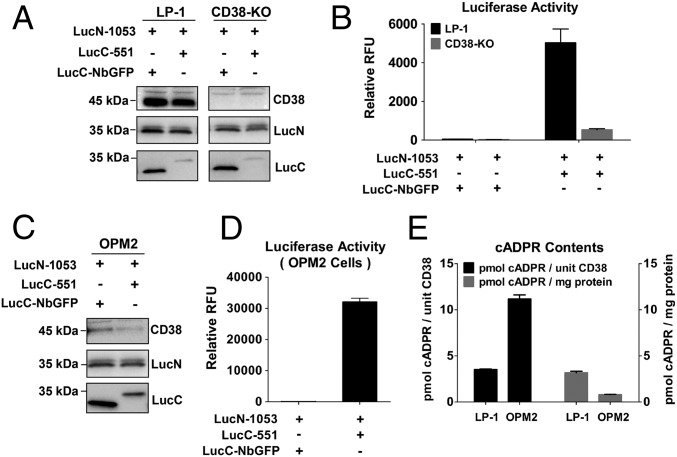

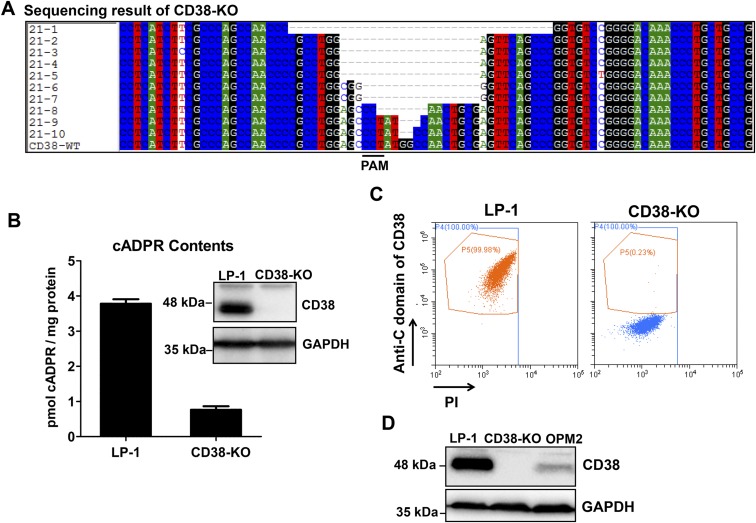

With the verification of the DepID method, it was then applied to two multiple myeloma cell lines derived from patients to determine if type III CD38 is naturally expressed in cells. Both LP-1 and OPM2 endogenously express high levels of CD38 (19). Cell lines, based on LP-1 and OPM2, stably expressing LucN-1053 and LucC-551 were generated. Western blots validated the expression of the probe proteins, as well as CD38, the expression level of which was much higher in LP-1 cells than in OPM2 cells (Fig. 2 A and C). Fig. 2 B and D show that high luminescence was readily detected in both cell types, whereas no luminescence was detected in the negative controls with LucC-NbGFP. Comparing OPM2 and LP-1 cells, OPM2 produced much higher luminescence even with much less CD38 expressed (compare Fig. S3D), indicating that most of it was intracellular type III. To substantiate the DepID method further, the CRISPR-Cas9 technique was used to delete CD38 in the LP-1 cells (22). Genomic sequencing (Fig. S3A), Western blot analyses (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3B, Inset), and cell surface staining (Fig. S3C) confirmed that the cells expressed no full-length CD38. The luminescence signal was likewise greatly suppressed (Fig. 2B). The residual signals might be due to a slight contamination with wild-type cells or some unknown splicing form of CD38 that was active but not deleted by CRISPR targeting (Fig. S3 A and B). We further measured the cADPR levels in the two cell lines. After normalizing the amounts of CD38 expressed in each cell line, the results showed that OPM2 produced cADPR more efficiently (Fig. 2E, left scale, black) than LP-1. The much higher amounts of CD38 in LP-1 cells did result in higher cADPR contents when normalized to total protein (Fig. 2E, right scale, gray). This result indicates that although both type II CD38 and type III CD38 contribute in producing the intracellular cADPR, the type III form is more efficient, consistent with our previous results (16, 17).

Fig. 2.

Endogenous type III CD38 in multiple myeloma cells detected with the DepID assay. (A) Western blots of wild-type and CD38-KO LP-1 cells stably expressing DepID probes. (B) Luminescence measurement in the LP-1 and CD38-KO cells as described in A. (C) Western blots of OPM2 cells stably expressing DepID probes. (D) Luminescence measurement in the OPM2 cells as described in C. (E) Intracellular cADPR in the cell lines. Amounts of cADPR were normalized either to the amounts of CD38 expressed (Left) or to total protein (Right). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. S3.

(A) Sequencing of the CD38-KO cells. More than two different deletions were found in CD38-KO. (B) cADPR contents in the CD38-KO cells. (Inset) Western blot analysis of CD38 expression level. (C) Live cells were stained with antibody against C-terminal CD38 analyzed with a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). (D, Upper) Expression levels of CD38 in LP-1 and OPM2 cells. (D, Lower) GAPDH serves as a loading control.

Identification of CIB1 as a Specific Interacting Partner of CD38.

The natural existence of intracellular type III CD38 with its C-domain facing the cytosol should allow ready modulation of its catalytic activity, and thus cellular cADPR levels, by many of the cytosolic regulatory mechanisms. To identify regulatory proteins that bind to and interact with the C-domain of the type III CD38, we used the yeast-two-hybrid approach (SI Materials and Methods). The 30-kDa C-domain of CD38 (sCD38) was used as bait to screen a human leukocyte library (Clontech). Ten positive clones were obtained, and all encoded the same full-length CIB1 (23). It is a cytosolic soluble protein of 183 residues having two high-affinity Ca2+-binding sites with the EF-hand motifs (24) (Fig. S4).

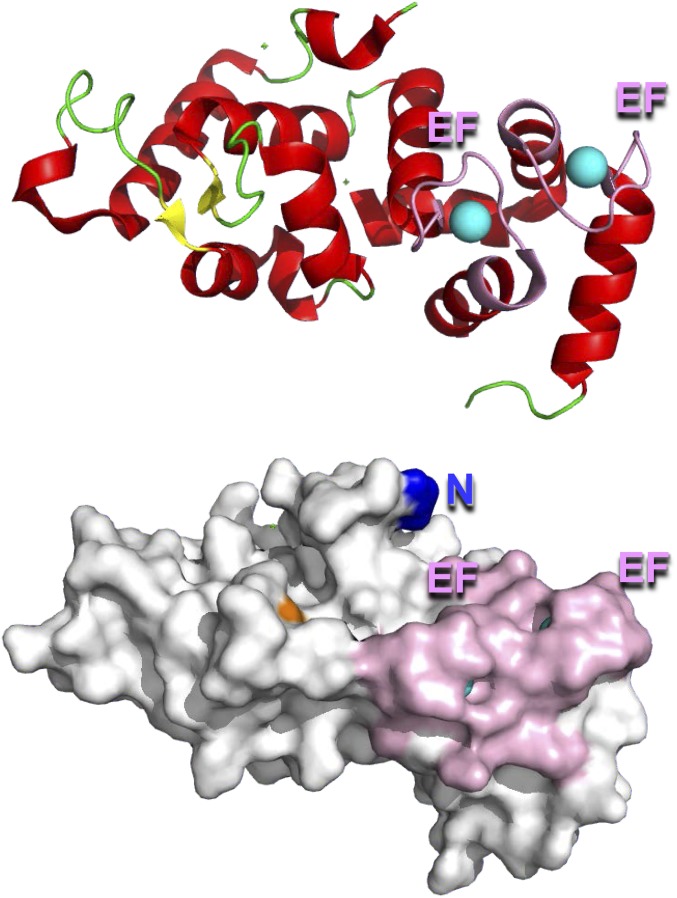

Fig. S4.

Secondary structures (Upper) and surface view (Lower) of CIB1 (Ca2+, cyan; helices, red; β-sheets, yellow; EF-hand, pink; coil, green; N terminus, blue; Ser78, orange). Structure coordinates are from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID code 1XO5).

The screening was repeated using a different library, a human spleen library (Clontech). For bait, we used an enzymatically inactive mutant of sCD38, by mutating the catalytic residue of sCD38 from glutamate 226 to glutamine [sCD38 (E226Q)] (25, 26). This change was made to avoid possible interference of the enzymatic product, cADPR, during the screening. Nine positive clones were obtained, and five of them were again positively identified as CIB1.

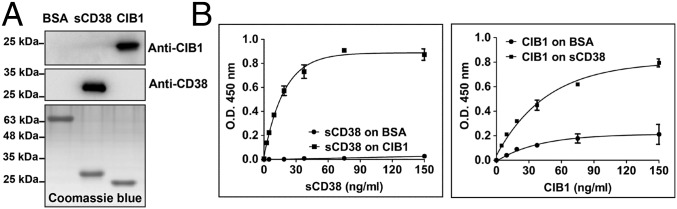

To demonstrate directly the interaction between the two proteins, CIB1 was expressed in Escherichia coli and sCD38 was expressed in yeast (26), and both were purified and verified (Fig. 3A). CIB1 was attached to an ELISA plate and incubated with increasing amounts of sCD38. After washing, the amounts of sCD38 specifically bound were assayed using anti-CD38 and peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. As shown in Fig. 3B, Left, saturable binding of sCD38 to CIB1 was observed. A control using BSA instead of CIB1 showed no signal. Similar results were obtained by attaching sCD38 to the surface and probing with increasing amounts of CIB1. Again, saturable binding was observed (Fig. 3B, Right).

Fig. 3.

In vitro interaction between recombinant CIB1 and sCD38. (A) Western blots and protein gel of the purified recombinant CIB1 and sCD38 used for ELISA. (B) In vitro binding between sCD38 and CIB1 analyzed by ELISA. (Left) Microtiter plates were coated with CIB1 or BSA and then incubated with increasing concentrations of sCD38. The amounts of sCD38 retained were measured using polyclonal anti-CD38. (Right) Similar to Left except that the plate was coated with sCD38 and incubated with increasing CIB1. The mean ± SEM of one representative experiment performed in triplicate is shown. O.D., optical density.

Intracellular Interaction of CD38 with CIB1.

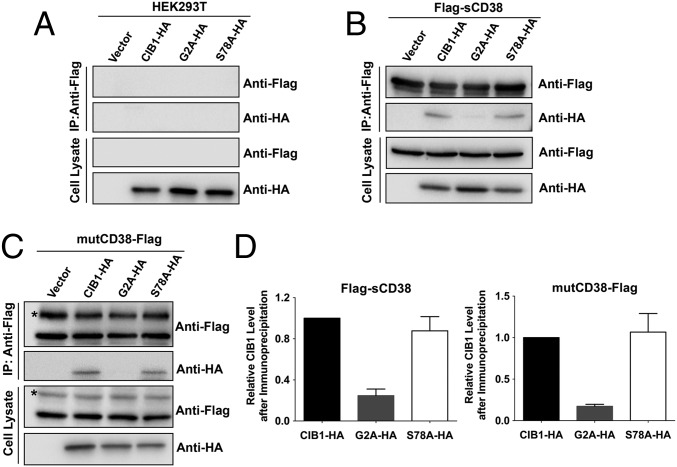

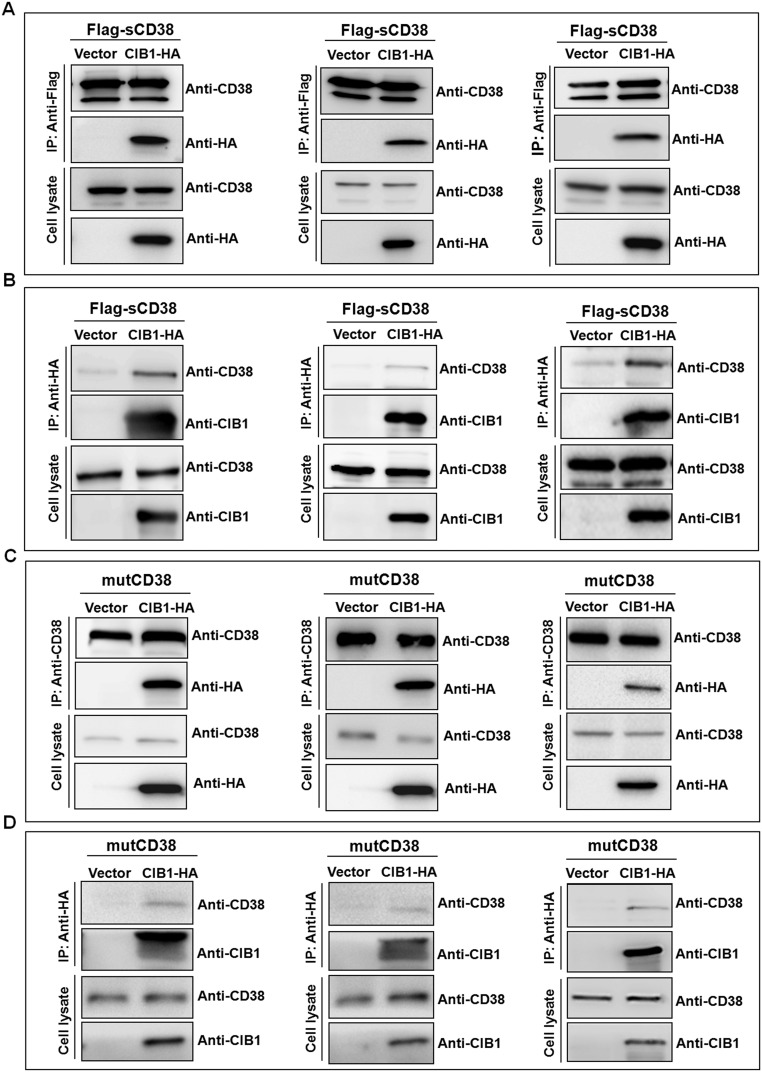

To show that the two proteins can interact inside cells, we used a line of HEK293T cells stably expressing Flag-tagged sCD38 in the cytosol (Flag-sCD38) (16, 27). After transfection with HA-tagged CIB1 and immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Flag, a prominent band was clearly present in cells expressing Flag-sCD38 [Fig. 4B and Fig. S5A, IP:anti-Flag, anti-HA] but not in control cells (Fig. 4A, HEK293T). The precipitates and total cell lysate were also analyzed using anti-CD38 or anti-Flag, which confirmed the presence of CD38 in the Flag-sCD38–expressing cells, but not in the control cells. The amounts of CD38 present in cells transfected with the vector with or without CIB1 were similar, which also served as an internal control for input of IP and gel loading.

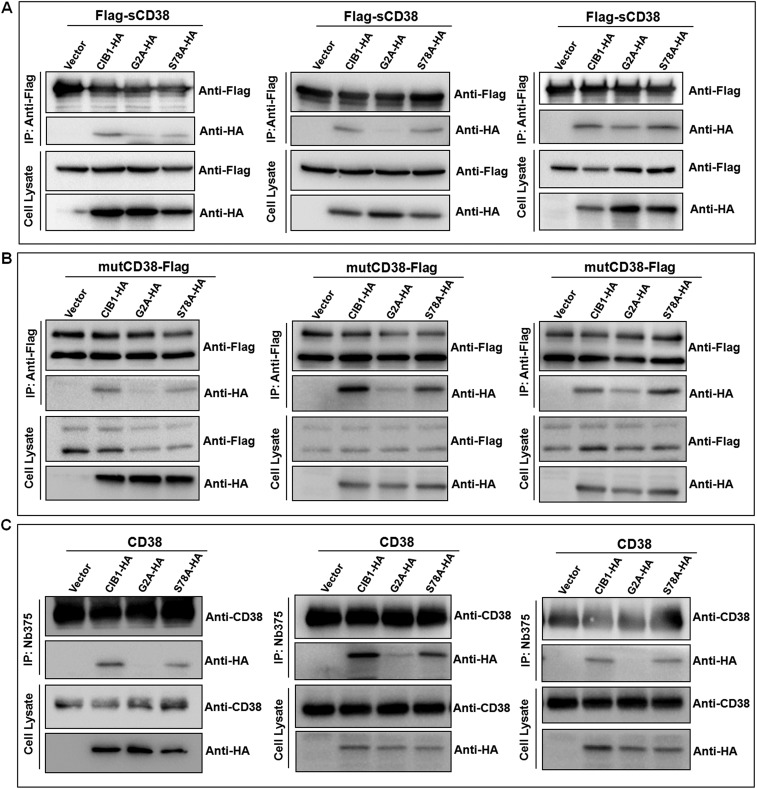

Fig. 4.

Mutational study on CIB1 interacting with type III CD38. HEK293T cells (A) or the cells stably expressing Flag-tagged sCD38 (B) or Flag-tagged mutCD38 (C) were transfected with empty vector, HA-tagged CIB1 (CIB1-HA), G2A (G2A-HA), or S78A mutant (S78A-HA). CD38 in the lysates was immunoprecipitated, followed by Western blots with anti-Flag or anti-HA. The label (*) in C indicates type II CD38. Results from one representative experiment are shown. (D) Quantification of CIB1-HA, G2A-HA, or S78A-HA in the gels after IP shown in B and C. Values are represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). Additional results are shown in Fig. S6.

Fig. S5.

Intracellular interaction between exogenous CIB1 and CD38. (A and B) HEK293T cells stably expressing Flag-tagged sCD38 were transfected with HA-tagged CIB1 or HA-empty vector. The cells were lysed, and Flag-sCD38 (A) or CIB1-HA (B) was immunoprecipitated, followed by Western blots for CD38 and CIB1/HA-tag. (C and D) Similar experiments were done on HEK293T cells stably expressing mutCD38.

Fig. S5B shows the results of the complementary experiment. The same Flag-sCD38 cells were transfected with either vector as a control or with CIB1-HA, but IP was done using anti-HA instead. Only cells expressing CIB1-HA showed the presence of CD38 (Fig. S5B, IP:anti-HA, anti-CD38) and CIB1 (Fig. S5B, IP:anti-HA, anti-CIB1) in the precipitates.

HEK293T cells stably expressing mutCD38 were transfected with CIB1-HA to determine if it could really interact with the transmembrane type III CD38. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag or anti-CD38, and the Western blots were probed using anti-HA. Fig. 4C and Fig. S5C show the clear presence of CIB1 in the precipitates (IP, anti-HA). Anti-Flag or anti-CD38 staining showed similar amounts of CD38 were present in both (Fig. 4C and Fig. S5C), serving as an internal control for input of IP and gel loading. A complementary experiment using anti-HA (CIB1) for the IP likewise confirmed that CD38 was present in the precipitates (Fig. S5D, IP:anti-HA, anti-CD38).

Identification of the N Terminus of CIB1 as Its CD38-Interacting Region.

Mutational analysis was then used to identify the interacting domain in CIB1. Mutating Gly2 in CIB1 to alanine eliminated its association with all forms of CD38 (Fig. 4 B and C and Fig. S6C, IP:anti-Flag, anti-HA, lane 3). No or little mutant CIB1 was detected in the immunoprecipitates of cytosolic CD38 (Fig. 4 B and D and Fig. S6A), mutCD38 (Fig. 4 C and D and Fig. S6B) and wt-CD38 (Fig. S6C). In contrast, mutating Ser78 to alanine (Fig. 4 B and C or Fig. S6, IP:anti-Flag or anti-CD38, anti-HA, lane 4), a potential phosphorylation site (28), was innocuous for the interaction. The amounts of the mutant CIB1 in cells expressing cytosolic CD38 (Fig. 4B), mutCD38 (Fig. 4C), and wt-CD38 (Fig. S6C) were similar to amounts expressing wild-type CIB1 (Cell Lysate, Anti-HA). The results indicate CIB1 interacts with the type III CD38 through its N-terminal region, which is on the surface (Fig. S4, blue). The innocuous Ser78 is, on the other hand, located in the interior (Fig. S4, orange). It is of interest to note that Gly2 is known to be the site for myristoylation of CIB1 (29), suggesting that the type III CD38, being a membrane protein, may have a preference for the myristoylated form of CIB1 due to its membrane localization or conformational difference.

Fig. S6.

(A and B) More micrographs as in Fig. 4. (C) Cells stably expressing wt-CD38 were transfected with empty vector, wild-type CIB1, G2A, or S78A mutant with an HA tag. The cells were lysed, and CD38 was immunoprecipitated, followed by Western blots for CD38 or CIB1.

Visualization of Intracellular Interaction of CD38 with CIB1 by Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation.

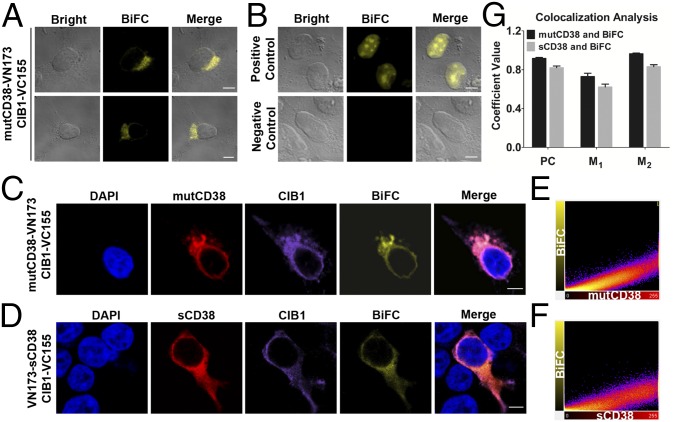

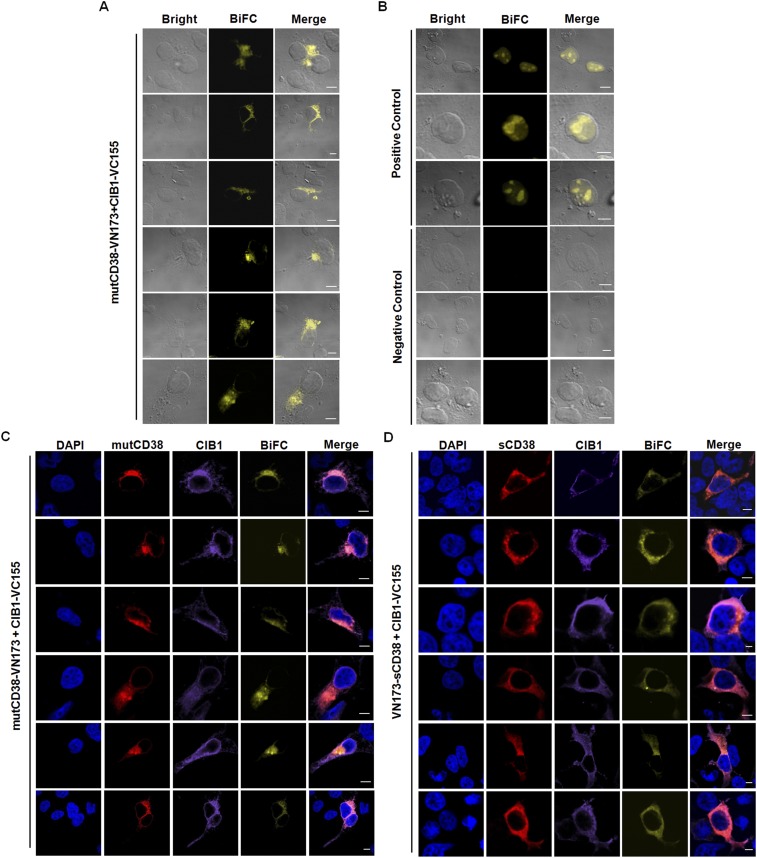

The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) technique (30) was then used to visualize CIB1 interacting with the type III CD38. The technique is based on the structural complementation of two nonfluorescent fragments, N-terminal (VN173) and C-terminal (VC155), of a fluorescent protein, Venus, that are fused, respectively, to a pair of interacting proteins. The binding of the two interacting proteins brings the two nonfluorescent fragments together and reconstitutes the fluorescence. Constructs were made by fusing VN173 to the C terminus of mutCD38 and VC155 to the C terminus of CIB1 (SI Materials and Methods). HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the two constructs, and, as shown in Fig. 5A and Fig. S7A, BiFC was observed in localized regions resembling the ER inside the live cells.

Fig. 5.

Visualization of intracellular association between CIB1 and type III CD38 using BiFC. (A) BiFC of mutCD38-VN173 and CIB1-VC155. (B) BiFC of bJun-VN173 and bFos-VC155 (positive control) or bJun-VN173 and bFosΔZIP-VC155 (negative control). (C and D) BiFC with the immunostaining signals of CIB1 (anti-HA, purple, Alexa Fluor 647) and mutCD38 (C; red, Alexa Fluor 555) or sCD38 (D; red, Alexa Fluor 555). BiFC fluorescence is shown in yellow, and nuclear staining (DAPI) is shown in blue. The merged image shows superposition of CD38, CIB1, and DAPI signals. (E and F) Colocalization analysis with Imaris software. Scatter-plot pixels correspond to the images shown in C and D. Complete colocalization results in a pixel distribution along a straight line whose slope will depend on the fluorescence ratio between the two channels. (G) PC, M1, and M2 were analyzed with JACoP. M1 is defined as the fraction of mutCD38 (black bars) or sCD38 (gray bars) overlapping BiFC signal; M2 is defined conversely. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM of 63 mutCD38 cells and 52 sCD38 cells. Additional results are shown in Fig. S7. (Scale bars: A–D, 5 μm.)

Fig. S7.

More micrographs as in Fig. 5. (Scale bars: 5 μm.) (A) BiFC of mutCD38-VN173 and CIB1-VC155. (B) BiFC of bJun-VN173 and bFos-VC155 (positive control) or bJun-VN173 and bFosδZIP-VC155 (negative control). (C and D) BiFC with the immunostaining signals of CIB1 (anti-HA, purple, Alexa Fluor 647) and mutCD38 (C; red, Alexa Fluor 555) or sCD38 (D; red, Alexa Fluor 555). BiFC fluorescence is shown in yellow, and nuclear staining (DAPI) is shown in blue. The merged image shows superposition of CD38, CIB1, and DAPI signals.

Fig. 5B and Fig. S7B show the positive control using Fos and Jun, which are known to interact inside the cell nucleus (31). Indeed, BiFC was observed only in the nucleus of the cells cotransfected with bJun-VN173 and bFos-VC155 (Fig. 5B and Fig. S7B, Upper). Truncated Fos (bFosΔZIP-VC155) loses its ability to interact with Jun, and no BiFC was observed (negative control; Fig. 5B and Fig. S7B, Lower).

Cellular distribution of CIB1-HA and the type III CD38 was visualized by immunofluorescence staining using anti-HA and anti-CD38. Fig. 5C and Fig. S7C show that the BiFC signals colocalized with the type III CD38 (mutCD38) in regions consistent with the ER. The distribution of CIB1 confirmed that it is a cytosolic molecule, but the BiFC signal was observed only in regions where it colocalized with the type III CD38.

As mentioned above, we have previously constructed the catalytic C-domain of CD38 as a soluble cytosolic protein (sCD38) (27). If CIB1 indeed binds to the C-domain, the BiFC pattern should be cytosolic in cells expressing sCD38 instead of mutCD38. Such was indeed the case, as shown in Fig. 5D and Fig. S7D. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with VN173-sCD38 and CIB1-VC155. The BiFC pattern was clearly cytosolic, essentially the same as the distribution of both CIB1 and sCD38. The fact that the BiFC pattern is determined by the subcellular distribution of CD38 strongly substantiates the authenticity of the technique for visualizing the two interacting proteins in cells.

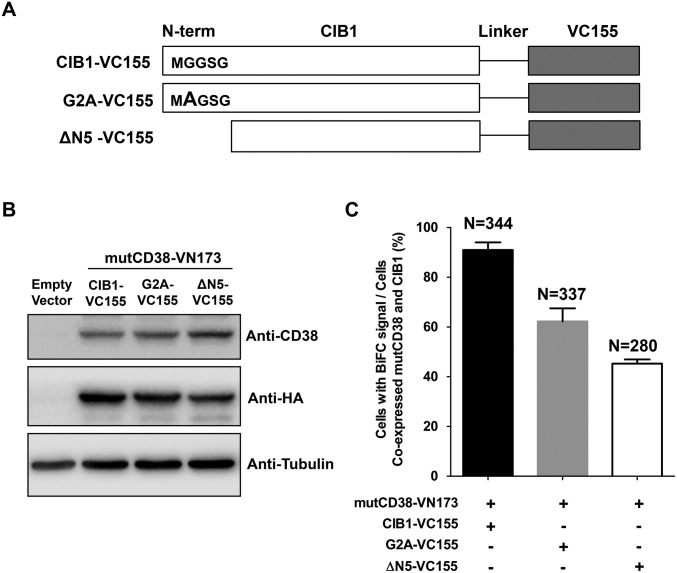

BiFC probes were also constructed for the G2A mutant of CIB1 described above and an additional mutant with the first five residues truncated. Consistently, the percentages of the mutCD38 cells transfected with these constructs and showed BiFC signals greatly decreased (Fig. S8).

Fig. S8.

Mutational study on CIB1 interacting with type III CD38 using the BiFC assay. (A) Diagram of VC155-tagged wild-type CIB1 (CIB1-VC155) and CIB1 mutants (G2A-VC155 with the mutation of Gly to Ala at the second amino acid of CIB1 and ΔN5-VC155 with the deletion of first five amino acids of CIB1). (B) Expression of CIB1-VC155, G2A-VC155, ΔN5-VC155, or mutCD38-VN173 in HEK293T cells analyzed by Western blot with anti-CD38 or anti-HA antibody. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Ratio of cells with BiFC signal in the cells coexpressing both mutCD38 and CIB1. Values were obtained by counting 280–344 cells (mean ± SEM).

The colocalization of mutCD38 and the BiFC signal was quantified by scatter plot. In Fig. 5E, the fluorescence intensities of mutCD38 and BiFC at each pixel of the image (Fig. 5C) were plotted in a 2D scattered graph using the program ImarisColoc. For perfect colocalization, points should fall on a straight line, the slope of which depends on the ratio of the fluorescence of the two signals. Fig. 5E shows that the points generally follow a straight line, indicating good colocalization. Fig. 5F shows similarly good colocalization for sCD38 and BiFC.

Colocalization for a population of cells was further analyzed using the Image J (NIH) plugin JACoP (SI Materials and Methods). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PC) and Menders’ coefficient (M1 and M2) were calculated for the mutCD38 and sCD38, as well as their respective BiFC signals. Fig. 5G shows the values of PC, M1, and M2 are all close to 1 for both mutCD38 vs. BiFC and sCD38 vs. BiFC (Fig. 5G), indicating good colocalization.

The above results, using three entirely different techniques, all confirmed that CIB1 specifically interacts with CD38 in vitro, as well as in live cells. The finding that the full-length type III CD38, as well as the catalytic C-domain of CD38, specifically interacts with a cytosolic regulatory protein also provides strong support for the type III signaling mechanism of CD38.

CIB1 Modulates the Intracellular cADPR Level.

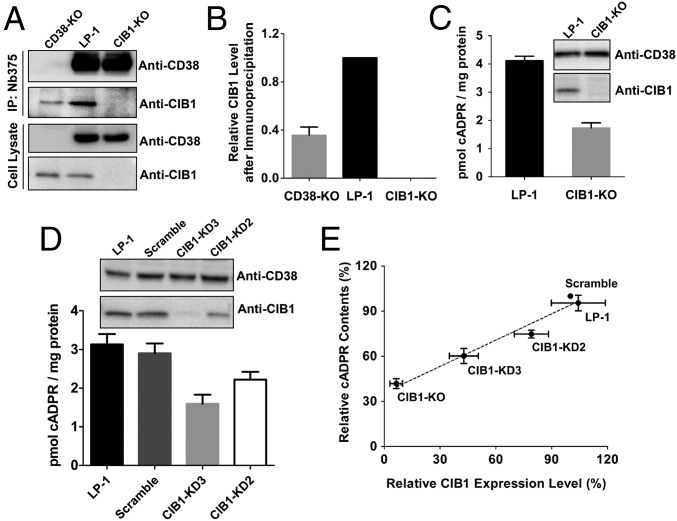

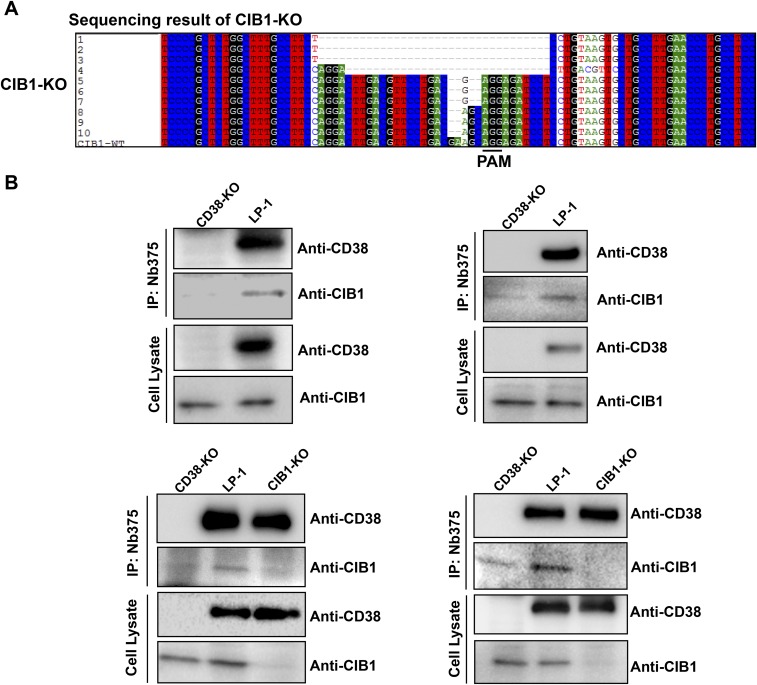

According to the results from the DepID assay, both LP-1 and OPM2 can be used to study the regulatory mechanism of endogenous type III CD38. We chose LP-1 because it endogenously expresses both CIB1 and CD38 (Fig. 6A, Cell Lysate, lane 2), making the results more physiologically relevant. To delete the CIB1 or CD38 gene, guide RNA targeting its exon region was cloned into the CRISPR plasmid lentiCRISPRv2 (32) or pX458 (22), respectively (SI Materials and Methods). As described in Materials and Methods, cell clones were selected, and sequencing confirmed the deletion (Fig. 3A and Fig. S9A). Western blot analysis also confirmed that CIB1 or CD38 was not expressed (Fig. 6A, Cell Lysate, lane 3, anti-CIB1 and lane 1, anti-CD38).

Fig. 6.

Correlation between cADPR contents and CIB1 expression levels. (A) Co-IP of endogenous CIB1 and CD38 with a nanobody against CD38 (Nb-375). Detection of CIB1 and CD38 was done using anti-CIB1 or anti-CD38, respectively. Additional results are shown in Fig. S9B. (B) Quantification of CIB1 after IP in similar gels as shown in A (mean ± SEM, n = 5). The intracellular cADPR contents in wild-type, CIB1-KO (C), and CIB1-knockdown (KD) (D) LP-1 cells are shown. (Inset) Western blots of CD38 and CIB1 in different LP-1 cells. (E) Linear correlation (R2 = 0.98) between CIB1 and cADPR contents. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Fig. S9.

(A) Sequencing of CIB1-KO cells. There are at least four different types of deletions, with lengths of 2 bp, 4 bp, 30 bp, and 34 bp, suggesting that the CIB1-KO cell line is a mixture of at least two clones or that CRISPR/cas9 was still active in cutting the genome after the selection of single colonies. (B) More Western blots similar to Fig. 6A.

With these cell lines, we first investigated the interaction between endogenous CD38 and CIB1. As shown in Fig. 6A (IP:Nb375), both CD38 and CIB1 could be pulled down in the wild-type LP-1 cells by the immobilized CD38 nanobody, Nb-375, which binds to an epitope overlapping with Nb-1053 (19). Background contamination by endogenous CIB1 during IP was assessed using CD38-KO cells (compare Fig. 2A), which showed much less CIB1 signal, and was completely eliminated in the CIB1-KO cells (Fig. 6 A and B).

The physiological association between CD38 and CIB1 prompted us to explore further the effect on cADPR production, which is one of the main direct functions of CD38 as a signaling enzyme. This analysis was done by depleting CIB1 in LP-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 6C, the cADPR contents in the CIB1-KO cells were measured to be greatly reduced to ∼40% of the contents of wild-type LP-1 cells. The CIB1 levels in cells can also be manipulated by using shRNA to reduce the expression of CIB1. Fig. 6D shows that the larger the reduction of the CIB1 levels (Inset), the larger is the reduction in the cADPR contents.

Combining all of the results in various treated cells with different CIB1 expression levels, there is a direct correlation between the cellular cADPR and CIB1 levels, with a correlation value (R2) of 0.98 (Fig. 6E). Because CIB1 is a cytosolic protein and, as shown above, it binds to the catalytic C-domain of CD38, the results indicate that CIB1 can modulate the enzymatic activity of the endogenous type III CD38 in human myeloma cells. The residual cADPR level in the CIB1-KO cells thus represented the basal cADPR-synthesizing activity of the endogenous type III CD38. Consistently, purified recombinant sCD38 is enzymatically active (8). Interaction with cytosolic CIB1 can thus potentially enhance this basal activity by about two- to threefold.

SI Materials and Methods

Materials.

The expression plasmid pcDNA3.1 (+) and yeast-two-hybrid system were obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. Lipofectamine 2000, FCS (FBS), DMEM, Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM), penicillin/streptomycin solution, trypsin, and Alexa Fluor-conjugated donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Life Technology. NADase was prepared from Neurospora crassa. Diaphorase from Clostridium kluyveri, NAD+, nicotinamide, alcohol dehydrogenase, resazurin, tri-n-octylamine, digitonin, poly-l-lysine, propidium iodide, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads, 3× FLAG peptide, and mouse monoclonal anti-Flag and anti-HA antibodies were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic Beads, dithiobis [succinimidylpropionate] (DSP) were obtained from Thermo Scientific. Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow and NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow were obtained from GE Healthcare. Rabbit polyclonal anti-CIB1 antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and mouse monoclonal anti-CIB1 antibody was obtained from Millipore.

HEK293 and HEK293T cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, and the myeloma cell lines, LP-1 and OPM2, were kindly provided by Annie An, Peking University, Beijing. Cell line authentication is achieved by genetic profiling using polymorphic short tandem repeat loci. The cells were cultured in DMEM (HEK293 and HEK293T), IMDM (LP-1), or RPMI 1640 (OPM2) supplemented with 10% or 20% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (Life Technology). The cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Construction of Plasmids.

Plasmids for IP.

To make the pCHMWS series of lentivector constructs, Flag-sCD38 and mutCD38 were subcloned from the corresponding pEGFP-C1 (27) or proGFP-N1 vector (16) into pCHMWS-EGFP, which was a gift from the Pasteur Research Centre of The University of Hong Kong. To make the construct pKH3-CIB1, the pcDNA3.1-CIB1-Myc obtained from Addgene (no. 32505) (40) was used as a template for amplification and subcloned into pKH3 (no. 12555; Addgene) by HindIII and XbaI. To make the constructs pKH3-G2A and pKH3-S78A with the mutation of Gly to Ala or Ser to Ala, mutagenesis was performed on the parent plasmid, pKH3-CIB1, with the Fast Mutagenesis System Kit (Transgene).

Plasmids for BiFC.

BiFC constructs encoding the N-terminal (-VN173) and C-terminal (-VC155) fragment of Venus were obtained from Addgene (nos. 22011 and 22010). To make the construct pBiFC-CIB1-VC155, the pBiFC-VC155 (no. 22010) was used as a template for amplification and subcloned into pKH3-CIB1. To make the constructs pBiFC-G2A-VC155 with the mutation of Gly to Ala, mutagenesis was performed on the parent plasmid, pBiFC-CIB1-VC155, with the Fast Mutagenesis System Kit. To make the CIB1 deletion mutant lacking residues 2–5 (ΔN5) and fused with VC155 (pBIFC-ΔN5-VC155), pBiFC-CIB1-VC155 was used as a template for amplification. To make the construct pBiFC-mutCD38-VN173, the proGFPN1-mutCD38 (16) was used as a template for amplification and subcloned into pBiFC-VN173 with HindIII and KpnI. To make the construct pBiFC-VN173-sCD38, the pEGFPC1-sCD38 (27) was used as a template and the VN173 was subcloned into pEGFPN1-sCD38 with NheI and XhoI. As positive or negative controls, pBiFC-bJun-VN173, pBiFC-bFos-VC155, and pBiFC-bFosDelataZip-VC155 were used (nos. 22012, 22013, and 22014; Addgene) (31).

Plasmid for protein expression and purification.

The synthetic CIB1 gene designed with optimal Escherichia coli codon use (41) with a 10-His tag was cloned into a pET15b (Novagen) vector and expressed in E. coli strain BL21.

Plasmids for DepID.

Lentiviral pCDH-EF1-LucN-T2A-Puro and pCDH-EF1-LucC-IRES-Neo (The Systems Biology Institute) vectors are based on two fragments of the humanized Gaussia princeps luciferase (the 16-aa N-terminal secretion signal sequence was not included, LucN and LucC) as previously described (20), an HA tag at the N terminus of LucN, and a Flag tag at the N terminus of LucC. Both LucN and LucC were linked to the N terminus of the target protein by a 10-aa flexible polypeptide linker consisting of (Gly.Gly.Gly.Gly.Ser)2. To construct LucN-1053 or LucC-551, Nb-1053 and Nb-551 were amplified from the phagemids pHEN2-1053 and pHEN2-551, separately (19), and subcloned to a pCDH-EF1-LucN-T2A-Puro vector or pCDH-EF1-LucC-IRES-Neo vector by EcoRI and NotI or EcoRI and BamHI. As a negative control, Nb-551 was replaced with the gene encoding NbGFP, which was amplified from the pOPINE-NbGFP nanobody (no. 49172; Addgene) (42). As positive controls, bJun and bFos were amplified from pBiFC-bJunVN173 and pBiFC-bFosVC155, separately, and subcloned to pCDH-EF1-LucN-T2A-Puro or pCDH-EF1-LucC-IRES-Neo vector by EcoRI and NotI or EcoRI and BamHI. All of the plasmids for DepID were used to prepare the lentiviral particles and applied to cell infection.

Construction of CD38/CIB1-KO or -Knockdown LP-1 Cell Lines.

To construct the CIB1-KO cell line, the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for CRISPR interference (5′-CTTGACGTTCCTGACGAAGC-3′) targeting the region in exon 2 of the CIB1 gene was cloned into the plasmid, lentiCRISPRv2 (no. 52961; Addgene) (32). For CIB1-knockdown cell lines, shRNA coding sequences (CIB1-KD2: 5′-GCCTTCCGCATCTTTGACTTT-3′, CIB1-KD3: 5′-GTCTGAGATGAAGCAGCTCAT-3′) were cloned into a lentivector, pLKO.1 (no. 10878; Addgene) (43), and pLKO.1-scramble (no. 1864; Addgene) (44) as a control. Lentiviral particles were prepared with the second-generation packaging system and applied to cell infection as described previously (43). The infected cells were selected by 1 μg/mL puromycin. For CIB1-KO cells, colonies were prepared by serial dilution and validated by DNA sequencing following PCR amplification of genomic DNA using the primer pair 5′-AGTCGCCTGTCCAAGGAGCTGCT-3′ and 5′-TAGTGGAGCCCAGGGTCAAAGAG-3′. To construct the CD38-KO cell line, the sgRNA for CRISPR interference (5′-CTGAACTCGCAGTTGGCCAT-3′), targeting exon 1 (around the start codon) of CD38, was cloned into an all-in-one CRISPR plasmid (pX458, no. 48138; Addgene) (22). This recombinant plasmid was transfected into LP-1 by electroporation using the Amaxa 4D-Nucleofector system (SF Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector X Kit, the 4D-Nucleofector program EN138; Lonza). Single-cell colonies were prepared, and CD38-KO colonies were validated by DNA sequencing following PCR amplification of the target region from the genomic DNA by the specific primers (5′-GCTCAGGTGTAAAGTGCC-3′ and 5′-TTCAGTGTACTTGACGCATC-3′).

Yeast-Two-Hybrid Screen.

The yeast-two-hybrid screens were conducted with a Clontech Matchmarker Two-Hybrid system (catalog no. K1612-1) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The bait sCD38 (amino acids 46–300) or sCD38-mut (an enzymatically inactive mutant of sCD38 made by mutating the catalytic residue of sCD38 from glutamate 226 to glutamine) fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain in the pGB vector was screened against a human leukocyte (no. 638821; Clontech) or spleen (no. 638824; Clontech) cDNA library in the pACT2-AD vector (no. 638822; Clontech), respectively, in the yeast strain Y190. Positive colonies were selected on the agar plate (SD/−Leu/−Trp/−His/+3AT), tested by a β-galactosidase assay, and sequenced.

Co-IP and Western Blotting.

Whole-cell lysates for IP were prepared in ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100] containing a protease inhibitor mixture (EDTA-Free Complete; Roche). IP was performed as previously described, with modifications (45). Briefly, HEK293T cells stably expressing sCD38 or mutCD38 were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells per 6-cm dish and transiently transfected with 4 μg of plasmid of pKH3-CIB1 or pKH3 as a negative control. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cell lysates were incubated overnight with Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads or Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic Beads, or with anti-CD38 antibody, and the immune complexes were precipitated using protein G-Sepharose, washed, and blotted with corresponding antibodies; signals were developed by adding ECL (Abvansta), detected and quantified by a Chemidoc MP system and ImageLab software (BIO-RAD). Ten percent of the lysate was used as the input control.

BiFC Assay and Immunofluorescence Imaging.

The BiFC assay was performed as previously described (30, 31). HEK293T cells were seeded at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well onto coverslips precoated with 0.005% poly-l-lysine in 24-well plates and transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of total DNA containing equal amounts of BiFC constructs as indicated in the main text. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were washed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Cells were then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) for 30 min and subsequently incubated with mouse anti-HA (VC155 fused with an HA tag) and rabbit anti-CD38 antibody for 1.5 h, followed by incubation of Alexa Fluor-conjugated donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Cells were then stained with DAPI for 5 min, mounted, and visualized by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510).

Colocalization Analysis.

Colocalization analysis was performed as previously described (46). PC, M1, and M2 were calculated by JACoP [a plugin of ImageJ software (NIH) in the public domain]. PC generates a range of values ranging from 1, representing a perfect positive correlation, to 0, representing a random distribution. M1 and M2 provide a measure of the total colocalized intensity divided by the total intensity for each fluorescence channel (mutCD38, sCD38, and BiFC). Scatter plots analyzed with both Imaris software (Bitplane Scientific Software AG) and JACoP showed similar results.

Solid-Phase Binding Assay.

Recombinant CD38 and CIB1 (sCD38 and CIB1) were prepared separately, as previously described (26, 41). Solid-phase binding assays were performed in a Corning 96 Well Clear Polystyrene High Bind Stripwell Microplate by ELISA. In detail, wells were coated overnight at 4 °C with 100 μL per well of 5 μg/mL recombinant sCD38 or CIB1 proteins and blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Following three washes with PBST, recombinant CIB1 or sCD38 was added at the indicated concentrations and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. After four washes with PBST, bound proteins were detected by specific mouse anti-CIB1 monoclonal or rabbit anti-CD38 polyclonal antibody for 1 h, followed by incubation of HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h. The peroxidase substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma) was added to the wells, the reaction was stopped with 2 M H2SO4 after 0–15 min, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an Infinite M200 PRO (Tecan).

Measurement of the Intracellular Production of cADPR.

The cells (1 × 106) were harvested, and cell pellets were lysed with 0.6 M perchloric acid. After centrifugation, the endogenous cADPR in the supernatant was measured by a cycling assay described previously (47), the pellets were redissolved in 1 M NaOH, and the protein amount was quantified by Bradford assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Quick Start Bradford Kit; BIO-RAD). Results were presented as picomoles of cADPR per milligram of total proteins.

DepID Assay of CD38 in Live Cells.

All of the plasmids encoding DepID probes, including LucN-1053 and LucC-551 or LucN-1053 and LucC-NbGFP, were packaged into lentiviral particles, which were used to infect HEK293, LP-1, or OPM2 cells to make DepID stable cell lines. In the experiments with HEK293 cells, the DepID stable cell lines were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1-Flag, pcDNA3.1-CD38-Flag, and pcDNA3.1-mutCD38-Flag plasmids separately, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technology). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, the cells were briefly digested by 0.05% trypsin-EDTA, stopped, and washed with PBS. The cells (2 × 105 cells per well) were plated in 96-well, flat-bottomed, white microtiter plates (Corning), and a protein complementation assay was performed accordingly (20). Native coelenterazine (Nanolight Technology) was prepared as a stock solution of 1 mM in propylene glycol under argon and diluted in PBS at room temperature before injection. The working concentration of coelenterazine was 20 μM. Signals of luminescence were read on an Infinite 200 PRO plate-reader (TECAN). To measure the endogenous type III CD38, LP-1, or OPM2 cells (∼1 × 105 cells) stably expressing DepID, probes were collected and suspended in PBS followed by assays performed as described above.

Discussion

A topological issue has remained unresolved ever since CD38 was established as the dominant enzyme for metabolizing cADPR in mammalian cells and tissues, because the enzymatic activity was presumed to face the extracellular region. An attractive feature of the type III signaling mechanism of CD38 is that it not only renders the issue moot but also provides a new approach for understanding the regulatory mechanism of CD38. The current results showing that the catalytic C-domain of CD38 interacts with a cytosolic regulatory protein, CIB1, and that this interaction leads to modulation of cADPR levels are strongly supportive of the mechanism.

Here, we devised a sophisticated DepID method to establish firmly the natural occurrence of the intracellular type III CD38. The requirement of the presence of dual epitopes greatly increases the specificity of the identification compared with other immunotargeting methods. The use of complementary reconstitution of luciferase ensures not only high sensitivity but also extremely low background. Furthermore, the method detects total type III CD38 present in both the plasma and organellar membranes. In all, DepID is a great improvement and much more definitive than the surface staining assay of the N-terminal tail sequence we previously used (16). The success of DepID in identifying CD38 is a proof of principle for the approach, which can be easily extended for identifying any cellular protein by using appropriate antibodies in the constructs. DepID is also topologically versatile. Here, we directed the expression of the luciferase probes to the cytosol to ensure targeting only the type III CD38 facing the cytosol. With an appropriate targeting sequence inserted into the probes, DepID can be designed to identify luminal proteins in organelles as well. DepID can be a general method of choice for protein identification.

CIB1 is a multifunctional regulatory protein having two high-affinity binding sites for Ca2+ with the EF-hand motifs. It has been shown to be involved in regulating Ca2+ signaling through binding to the inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor and modulating its ion channel activity (23). Here, we showed that CIB1 interacts with type III CD38 through its N terminus. Mutating Gly2 abolished the interaction, indicating specificity (Fig. 4). Gly2 is also known to be the myristoylation site of CIB1. Considering that CIB1 is a Ca2+/myristoyl switch, changes in intracellular Ca2+ may alter its interaction with CD38, resulting in consequential modulation of its enzymatic activity. The mechanistic details are now being explored. It seems unlikely, however, that direct binding of CIB1 to CD38 can alter its catalytic activity via conformational change, because the crystal structure of CD38 shows that it is a rather rigid molecule with six disulfide bridges (26, 33). However, if the binding is at the mouth of the active site pocket, it could lead to changes in the entry and exit of NAD and/or cADPR.

For type III CD38, its catalytic C-domain is in the reducing environment of the cytosol. Some of its disulfide bridges could be disturbed. A possible function of CIB1 could thus be serving as a protein chaperone, preserving the disulfides of CD38 and its enzymatic activity. We have shown that all of the disulfides, except the last one (C287–C296), are important for the cADPR-synthesizing activity of CD38 (27). Mutation of the individual cysteine residues of these disulfides can lead to a 70–80% reduction in activity. By preserving the disulfides, CIB1 can thus effect about a two- to threefold enhancement of the type III CD38 activity, consistent with the extent of enhancement that was observed in this study (Fig. 6).

Another possibility for modulation of the CD38 activity could be through modification of the catalytic domain of CD38. CIB1 is known to interact with a variety of kinases, including ASK1 (34). This fact is relevant because we and others have reported that cADPR synthesis in sea urchin eggs is activated by a cGMP-dependent phosphorylation process (35, 36). A similar mechanism also operates in rat hippocampus (37). In human granulocytes, agonist-induced activation and phosphorylation of CD38 are found to be cAMP-dependent (38). CIB1 can function as an adaptor protein, binding and recruiting various kinases to the proximity of the catalytic domain of CD38 and effecting regulation through phosphorylation. The converse could also be true, because CIB1 is also known to bind calcineurin B, a regulatory subunit of the phosphatase calcineurin (39). Although the exact mechanism of how CIB1 modulates CD38 activity remains to be elucidated, the facts that the type III CD38 naturally exists and a cytosolic regulator, CIB1, is involved in regulating its activity point to a new paradigm for understanding the cADPR/CD38 signaling pathway.

Materials and Methods

Details of the materials and methods used, including the yeast-two-hybrid screen, vector constructions, DepID, immunostaining, and other assays, are available in SI Materials and Methods. All relevant data are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Graeff for reading and editing our manuscript. This study was supported by grants from National Science Foundation of China (Grant 31501134 to J.L., Grant 31571438 to Y.J.Z., and Grants 31470815 and 31671463 to H.C.L.) and grants from Shenzhen and Guangdong Governments (Grants JCYJ20150331100801849, JCYJ20160428153800920, JCYJ20160608091848749, ZDSYS201504301539161, KQTD2015071714043444, and 2014B030301003).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1703718114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lee HC. Cyclic ADP-ribose and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) as messengers for calcium mobilization. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31633–31640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.349464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HC. The cyclic ADP-ribose/NAADP/CD38-signaling pathway: Past and present. Messenger (Los Angel) 2012;1:16–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HC, Aarhus R, Levitt D. The crystal structure of cyclic ADP-ribose. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:143–144. doi: 10.1038/nsb0394-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HC, Walseth TF, Bratt GT, Hayes RN, Clapper DL. Structural determination of a cyclic metabolite of NAD+ with intracellular Ca2+-mobilizing activity. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1608–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rusinko N, Lee HC. Widespread occurrence in animal tissues of an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of NAD+ into a cyclic metabolite with intracellular Ca2+-mobilizing activity. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11725–11731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee HC, Aarhus R. ADP-ribosyl cyclase: An enzyme that cyclizes NAD+ into a calcium-mobilizing metabolite. Cell Regul. 1991;2:203–209. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.States DJ, Walseth TF, Lee HC. Similarities in amino acid sequences of Aplysia ADP-ribosyl cyclase and human lymphocyte antigen CD38. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:495. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard M, et al. Formation and hydrolysis of cyclic ADP-ribose catalyzed by lymphocyte antigen CD38. Science. 1993;262:1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.8235624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takasawa S, et al. Synthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic ADP-ribose by human leukocyte antigen CD38 and inhibition of the hydrolysis by ATP. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26052–26054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato I, et al. CD38 disruption impairs glucose-induced increases in cyclic ADP-ribose, [Ca2+]i, and insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1869–1872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin D, et al. CD38 is critical for social behaviour by regulating oxytocin secretion. Nature. 2007;446:41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature05526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partida-Sánchez S, et al. Cyclic ADP-ribose production by CD38 regulates intracellular calcium release, extracellular calcium influx and chemotaxis in neutrophils and is required for bacterial clearance in vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1209–1216. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson DG, Bell JI. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the human CD38 (T10) molecule, a cell surface glycoprotein with an unusual discontinuous pattern of expression during lymphocyte differentiation. J Immunol. 1990;144:2811–2815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruzzone S, et al. Subcellular and intercellular traffic of NAD+, NAD+ precursors and NAD+-derived signal metabolites and second messengers: Old and new topological paradoxes. Messenger (Los Angel) 2012;1:34–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Flora A, Zocchi E, Guida L, Franco L, Bruzzone S. Autocrine and paracrine calcium signaling by the CD38/NAD+/cyclic ADP-ribose system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1028:176–191. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao YJ, Lam CM, Lee HC. The membrane-bound enzyme CD38 exists in two opposing orientations. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra67. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao YJ, Zhu WJ, Wang XW, Zhang LH, Lee HC. Determinants of the membrane orientation of a calcium signaling enzyme CD38. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:2095–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HC, Zhao YJ. The type III calcium signaling mechanism of CD38. Messenger (Los Angel) 2014;3:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li T, et al. Immuno-targeting the multifunctional CD38 using nanobody. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27055. doi: 10.1038/srep27055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassonnet P, et al. Benchmarking a luciferase complementation assay for detecting protein complexes. Nat Methods. 2011;8:990–992. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta K, Shahid U, Malavasi F. Human CD38, a cell-surface protein with multiple functions. FASEB J. 1996;10:1408–1417. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.12.8903511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White C, Yang J, Monteiro MJ, Foskett JK. CIB1, a ubiquitously expressed Ca2+-binding protein ligand of the InsP3 receptor Ca2+ release channel. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20825–20833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentry HR, et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of CIB1 delineates a new family of EF-hand-containing proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8407–8415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q, et al. Structural basis for the mechanistic understanding of human CD38-controlled multiple catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32861–32869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munshi C, et al. Identification of the enzymatic active site of CD38 by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21566–21571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909365199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao YJ, Zhang HM, Lam CM, Hao Q, Lee HC. Cytosolic CD38 protein forms intact disulfides and is active in elevating intracellular cyclic ADP-ribose. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22170–22177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armacki M, et al. A novel splice variant of calcium and integrin-binding protein 1 mediates protein kinase D2-stimulated tumour growth by regulating angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2014;33:1167–1180. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarman KE, Moretti PA, Zebol JR, Pitson SM. Translocation of sphingosine kinase 1 to the plasma membrane is mediated by calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:483–492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shyu YJ, Liu H, Deng X, Hu CD. Identification of new fluorescent protein fragments for bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis under physiological conditions. Biotechniques. 2006;40:61–66. doi: 10.2144/000112036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu CD, Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol Cell. 2002;9:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11:783–784. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Q, et al. Crystal structure of human CD38 extracellular domain. Structure. 2005;13:1331–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon KW, et al. 2009. CIB1 functions as a Ca(2+)-sensitive modulator of stress-induced signaling by targeting ASK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:17389–17394, and erratum (2006) 106:19629.

- 35.Galione A, et al. cGMP mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in sea urchin eggs by stimulating cyclic ADP-ribose synthesis. Nature. 1993;365:456–459. doi: 10.1038/365456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willmott N, et al. Nitric oxide-induced mobilization of intracellular calcium via the cyclic ADP-ribose signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3699–3705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reyes-Harde M, Potter BV, Galione A, Stanton PK. Induction of hippocampal LTD requires nitric-oxide-stimulated PKG activity and Ca2+ release from cyclic ADP-ribose-sensitive stores. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1569–1576. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruzzone S, et al. Abscisic acid is an endogenous cytokine in human granulocytes with cyclic ADP-ribose as second messenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5759–5764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609379104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heineke J, et al. CIB1 is a regulator of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2010;16:872–879. doi: 10.1038/nm.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haataja L, Kaartinen V, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. The small GTPase Rac3 interacts with the integrin-binding protein CIB and promotes integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3)-mediated adhesion and spreading. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8321–8328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamniuk AP, Nguyen LT, Hoang TT, Vogel HJ. Metal ion binding properties and conformational states of calcium- and integrin-binding protein. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2558–2568. doi: 10.1021/bi035432b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kubala MH, Kovtun O, Alexandrov K, Collins BM. Structural and thermodynamic analysis of the GFP:GFP-nanobody complex. Protein Sci. 2010;19:2389–2401. doi: 10.1002/pro.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moffat J, et al. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonifacino JS, Dell’Angelica EC. 2001. Immunoprecipitation. Curr Protoc Cell Biol Chapter 7:Unit 7.2.

- 46.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C723–C742. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graeff R, Lee HC. A novel cycling assay for cellular cADP-ribose with nanomolar sensitivity. Biochem J. 2002;361:379–384. doi: 10.1042/bj3610379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]