Significance

The lateral neural plate border (NPB) gives rise to the neural crest, one of the precursors of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and generally considered an evolutionary innovation of the vertebrate lineage. Recently, it has been reported that a rudimentary neural crest exists in protovertebrate Ciona, but whether this is true in other invertebrates and there is conserved molecular machinery specifying the NPB lineage are unknown. We present evidence that orthologs of the NPB specification module specify lateral neural progenitor cells in several invertebrates, including worm, fly, and tunicate. We propose that an ancient lateral neuroblast gene regulatory module was coopted by chordates during the evolution of PNS progenitors.

Keywords: C. elegans, neural plate border, neural border, Msx/vab-15, ZNF703/tlp-1

Abstract

The lateral neural plate border (NPB), the neural part of the vertebrate neural border, is composed of central nervous system (CNS) progenitors and peripheral nervous system (PNS) progenitors. In invertebrates, PNS progenitors are also juxtaposed to the lateral boundary of the CNS. Whether there are conserved molecular mechanisms determining vertebrate and invertebrate lateral neural borders remains unclear. Using single-cell-resolution gene-expression profiling and genetic analysis, we present evidence that orthologs of the NPB specification module specify the invertebrate lateral neural border, which is composed of CNS and PNS progenitors. First, like in vertebrates, the conserved neuroectoderm lateral border specifier Msx/vab-15 specifies lateral neuroblasts in Caenorhabditis elegans. Second, orthologs of the vertebrate NPB specification module (Msx/vab-15, Pax3/7/pax-3, and Zic/ref-2) are significantly enriched in worm lateral neuroblasts. In addition, like in other bilaterians, the expression domain of Msx/vab-15 is more lateral than those of Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2 in C. elegans. Third, we show that Msx/vab-15 regulates the development of mechanosensory neurons derived from lateral neural progenitors in multiple invertebrate species, including C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Ciona intestinalis. We also identify a novel lateral neural border specifier, ZNF703/tlp-1, which functions synergistically with Msx/vab-15 in both C. elegans and Xenopus laevis. These data suggest a common origin of the molecular mechanism specifying lateral neural borders across bilaterians.

The vertebrate neural border is a transient embryonic domain located between the neural plate and nonneurogenic ectoderm from late gastrulation to early neurulation. The neural border is composed of the lateral neural plate border (NPB) and preplacode ectoderm (PPE) subdomains (1, 2). The NPB and PPE give rise to the neural crest and placode, respectively, both of which undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition/delamination, migrate in prototypical paths, and give rise to the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and many other cell types (3, 4). However, the NPB and PPE also have many different features (5). For example, the PPE is confined to the anterior half of embryos and does not contribute to the central nervous system (CNS), whereas the NPB is the lateral border of the whole neural plate and consists not only of progenitors for the PNS but also those for the CNS in the dorsal neural tube. The juxtaposed localization of the CNS neuroectoderm and PNS progenitors also occurs in the trunk of invertebrate embryos such as nematodes, arthropods, annelids, and urochordates (6–9), reminiscent of vertebrate NPB. In Caenorhabditis elegans, lateral neuroblasts (P, Q, and V5 cells) are located between the embryonic CNS and skin from the birth of these cells (10). In addition, worm lateral neuroblasts possess several key cellular and developmental features of vertebrate NPB. For example, the medially located P neuroblasts display nuclear migration and give rise to multiple cell types, including CNS motor neurons (10). The laterally located V5 and Q neuroblasts give rise to PNS neurons; that is, V5 neuroblasts give rise to the mechanosensory neuron PVD, whereas QL and QR neuroblasts give rise to the migratory mechanosensory neurons AVM and PVM, respectively (10). Furthermore, Q neuroblasts undergo delamination and migrate along prototypical paths while dividing and differentiating (10), similar to the neural crest in vertebrates and mechanosensory bipolar tail neurons (BTNs) in tunicate (3, 9). At the molecular level, Msx/vab-15 establishes the identity of the lateral boundary of the neuroectoderm in fly, annelids, amphioxus, lamprey, and higher vertebrates. Also, their Msx/vab-15–expressing domains include both CNS and PNS progenitors (8, 11–14). Worm Msx/vab-15 expression was observed in lateral P neuroblasts, progenitors of larval CNS motor neurons. Furthermore, development of mechanosensory neurons is defective in Msx/vab-15 mutants (15). These evolutionary echoes suggest that studies in C. elegans may reveal new clues regarding whether there is a conserved molecular mechanism underlying development of worm lateral neuroblasts and vertebrate NPB.

Using genetic analysis, we show here that worm Msx/vab-15 expresses in and specifies all lateral neuroblasts. We also did comparative analysis in multiple species, including C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Ciona intestinalis, to show that Msx/vab-15 regulates the development of mechanosensory neurons derived from their lateral neural borders, similar to its role in the vertebrate NPB. We profiled the expression of 90% conserved transcription factors in worm trunk ectoderm at the resolution of single cells and found that orthologs of the vertebrate NPB specification module are significantly enriched in worm lateral neuroblasts. More interestingly, a novel NPB specifier, ZNF703/tlp-1, was identified and shown to be synergistic with Msx/vab-15 in regulating lateral neural progenitors in both C. elegans and Xenopus laevis, providing another molecular clue to trace the origin and evolution of the lateral neural border.

Results

Msx/vab-15 Specifies Lateral Neuroblasts in C. elegans.

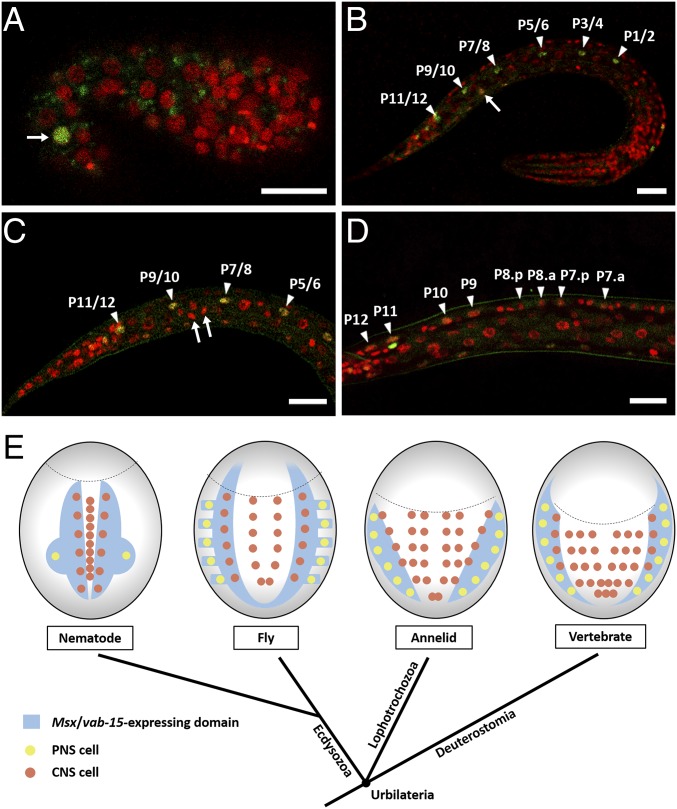

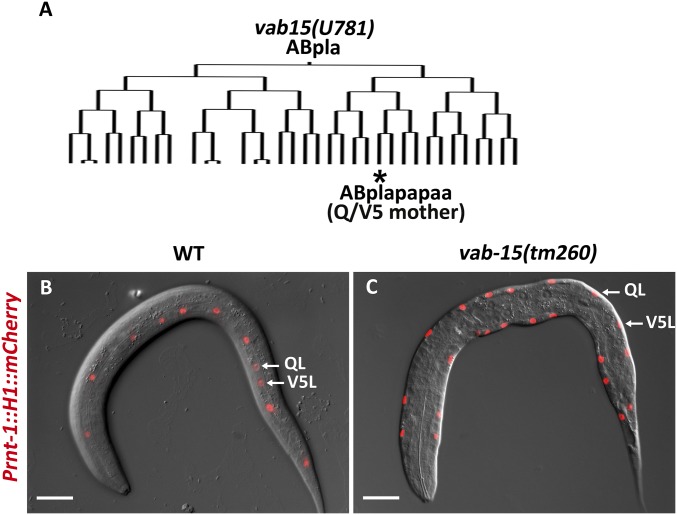

A previous study in C. elegans did not detect Msx/vab-15 reporter expression in V5 and Q neuroblasts (15). To reveal the expression pattern of endogenous Msx/vab-15, we generated a knockin worm strain in which GFP was integrated into the 3′ end of the Msx/vab-15–coding sequence in the genome. Worms of the knockin strain do not show any detectable phenotype, suggesting the GFP knockin does not disturb the expression of vab-15. The knockin strain shows significant Msx/vab-15 expression in embryonic AB.p(lr)apapaa, which is the mother cell of Q and V5 neuroblasts (Fig. 1A). After the division of this mother cell, Msx/vab-15 expression turns off in V5 neuroblasts but is maintained in Q cells until they divide (Fig. 1 B and C). P-neuroblast expression of Msx/vab-15 starts before hatching, is maintained while P nuclei migrate into the ventral midline in early L1-stage larvae, and shuts down after P neuroblasts divide (Fig. 1 B and D).

Fig. 1.

Expression of Msx/vab-15 in the trunk nervous systems of bilaterians. (A–D) Lateral view of Msx/vab-15::GFP knockin comma-stage embryo (A), newly hatched L1 larvae (B), middle L1 (C), and late L1 (D). The red channel represents Histone1::mCherry knockin to label nuclei universally. Arrows indicate the mother cell of Q and V5 (A), Q neuroblast (B), or Q daughter cells (C). Arrowheads indicate P neuroblasts (B and C) and their daughter and granddaughter cells (D). In middle L1 stage, P nuclei have arrived at the ventral midline (C). Anterior end of larvae is to the right, and ventral side is up. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (E) The schematic drawing of neurulae represents the dorsal view of vertebrates and the ventral view of protostomes. The head region in each animal lies above the dotted arc. Only in the ectoderm of C. elegans are neuroblasts drawn according to their precise numbers: a pair of PNS progenitors [AB.p(lr)apapaa, the mother cell of V5 and Q neuroblasts]; six pairs of P neuroblasts; and nine progenitors of ventral cord motor neurons in the midline. The Msx/vab-15–expressing domain in the annelid is based on Platynereis dumerilii (8). The Msx/vab-15–expressing domain in fly is based on D. melanogaster (7). The vertebrate Msx/vab-15–expressing domain represents the merged expression patterns of Msx1, Msx2, and Msx3 in mouse (34, 35).

To investigate the function of Msx/vab-15 during worm development, we phenotyped Msx/vab-15 mutants. These mutants appear to have wild-type embryonic cell lineage and produce lateral neuroblasts that can even divide in larvae (Figs. 2 and 3B and Fig. S1), but their P neuroblasts are significantly defective in nuclear migration, and those that migrate into the midline frequently fail to give rise to hypodermal daughter cells or neurons (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Q neuroblasts in mutants show a defect in migration too (Fig. 3B), and fail to give rise to mechanosensory neurons with nearly full penetrance (Fig. 3 D and F and Table 1). Similarly, V5 neuroblasts in mutants also fail to give rise to neurons (Fig. 3H).

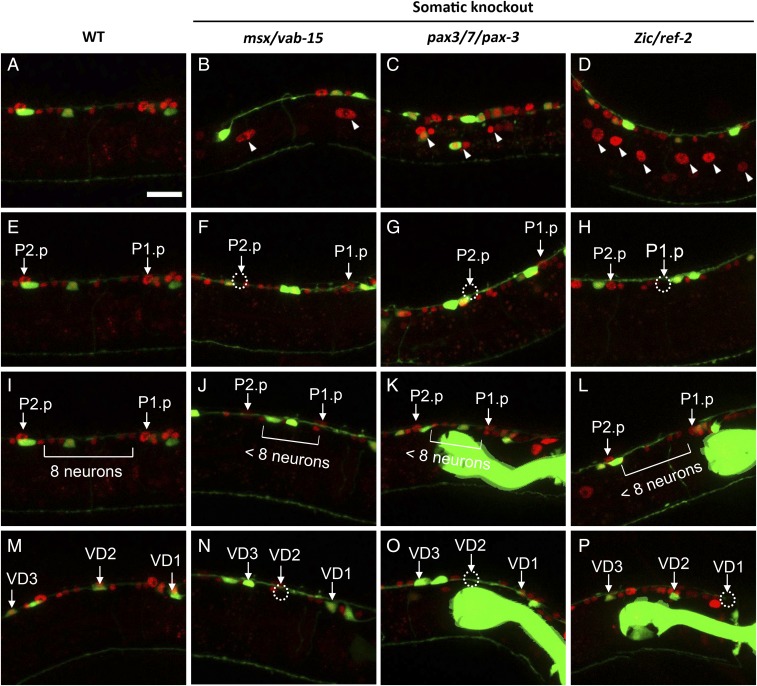

Fig. 2.

Msx/vab-15, Pax3/7/pax-3, and Zic/ref-2 are required for migration and differentiation of P neuroblasts. Somatic knockout was induced by heat shocking embryos carrying the Phsp::CAS9 transgene. The Pref-2::H1::mCherry reporter was used as a marker to label P-neuroblast progeny. The Punc-25::GFP reporter was used to label D-type ventral cord motor neurons. VDs are P-derived D-type neurons. (A, E, I, and M) Wild-type L2 larvae, when all P progenies arrive at the ventral midline (A) and give rise to hypodermal Pn.p (E) and neurons (I and M) distributed with stereotypical patterns. Arrowheads indicate progenies of P neuroblasts that are defective in migration, as shown retained in the lateral body. In mutant worms, some P neuroblasts cannot migrate to the ventral cord and retain in the middle body of worm (B–D). Among P neuroblasts that successfully migrated into the ventral cord, some failed to give rise to hypodermal Pn.p (F–H), neurons (J–L), such as VD neurons (N–P). Dotted circles indicate missing nuclei. Each worm was arranged such that its anterior end was to the right and its ventral midline was at the top. Green fluorescence in pharynx represents the Pmyo-2::GFP coinjection marker (K, L, O, and P). All of the worms detected were at L2 stage. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Fig. 3.

Msx/vab-15 is required for the development of worm lateral PNS progenitors. The boundary of the worm body is delineated by dashed lines. (A and B) Migration of Q neuroblast progeny cells. Dotted circles indicate Q daughter or granddaughter cells. Examined worms were at late L1 stage. Q daughters were separating due to their different migration rate in wild type (A), whereas they failed in migration in the vab-15 mutant so that even their granddaughters are clustered together (B). (C–F) Q-derived mechanosensory neurons AVM (arrow in C) and PVM (arrow in E) were missed in the vab-15 mutant (D and F). Examined were L2 larvae. Arrowheads indicate ALM (C and D) or PLM (E and F) neurons as a landmark. (G and H) V5-derived mechanosensory neuron PVD (arrow). egl-17: markers of Q neuroblasts and their progeny (47). mec-4: markers of AVM/PVM (58). mec-10: markers of AVM/PVM and PVD (59). Arrowheads indicate the PLM neuron as a landmark. Examined were L3 larvae. (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

Fig. S1.

Retention of Q cells in Msx/vab-15 mutants. (A) Intact embryonic cell lineage of the vab-15(u781) mutant up to the 398-cell stage, in which the mother cell of V5 and Q has been generated. (B and C) Retention of Q cells in vab-15 mutant larvae. Prnt-1::H1::cherry, marker of Q and seam precursor cells. Shown are the lateral view (B) and ventral view (C) of newly hatched L1 larvae. (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

Table 1.

Genetic analysis of migration and differentiation of lateral neuroblasts

| Gene | Allele | Frequency of worms with neuroblast migration defect, % (n) | Frequency of worms with neuroblast differentiation defect, % (n) | ||||

| Q*,† | P‡ | Missing PDE§ (V5.paaa#) | Missing AVM† (QR.paa#) | Missing PVM† (QL.paa#) | Not 13 VDs¶ (Pn.app#) | ||

| Wild type | 0 (100) | 0 (30) | 1 (105) | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 0.5 (200) | |

| Msh/vab-15 | tm260 | 34 (44) | 81 (101) | 58 (112) | 96 (104) | 96 (101) | 100 (44) |

| Knockout in embryo|| | 19 (32) | 46.46 (99) | 30 (50) | 28 (50) | 16 (50) | 46.46 (99) | |

| Knockout in L1|| | 13 (23) | 0 (27) | 6 (50) | 4 (25) | 8 (50) | 0 (27) | |

| NLZ/tlp-1 | bx85 | 0 (50) | 0 (55) | 2 (100) | 13 (101) | 4 (104) | 0 (101) |

| ZNF/ztf-6 | tm1803 | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 2 (42) | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 0 (100) |

| Ash/hlh-3 | tm1688 | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 0 (100) | 3.6 (280) |

| Zic/ref-2 | Knockout in embryo|| | 0 (42) | 54 (63) | 0 (50) | 0 (42) | 0 (42) | 54 (63) |

| pax3/7/pax-3 | Knockout in embryo|| | 0 (22) | 41.7 (60) | 4 (50) | 0 (22) | 0 (22) | 45 (60) |

The number of scored animals in each experiment is in parentheses.

A late-stage larva is considered abnormal if either the AVM or PVM is mislocated.

mec-4 reporter as an AVM/PVM neuron marker.

ref-2 reporter as a marker of P neuroblasts and their progeny.

dat-1 reporter as a PDE marker.

unc-25 reporter as a VD neuron marker.

Cell lineage of the specified neuron.

Somatic knockout is induced by heat shock activating Phsp::CAS9 in a specified stage.

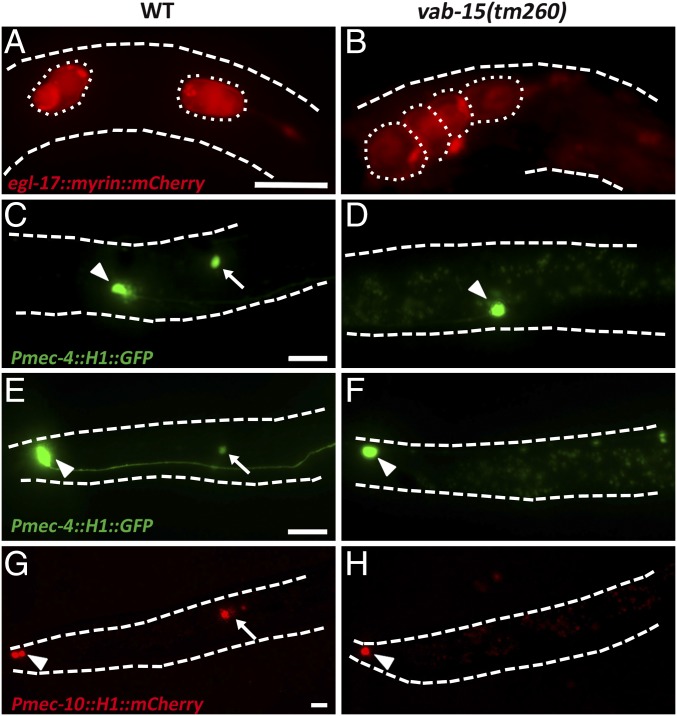

V5 neuroblasts show a strong phenotype in Msx/vab-15 mutants even though Msx/vab-15 expression shuts down right after the separation from its sister cell Q in late embryos, indicating Msx/vab-15 specifies the cell fate of these neuroblasts at the embryo stage, instead of functioning at the larval stage. To dissect the temporal role of Msx/vab-15, we generated an Msx/vab-15 somatic knockout strain in which CAS9 is driven by a heat-shock promoter. Disrupting Msx/vab-15 at an early stage by heat shocking embryos results in a significant migration and differentiation defect of the lateral neuroblasts. On the contrary, disrupting Msx/vab-15 in newly hatched L1 larvae does not lead to a significant differentiation phenotype in V5 and Q neuroblasts (Table 1). Similarly, knocking out Msx/vab-15 at the early L1 stage does not affect the development of P neuroblasts, either (Table 1). In summary, our endogenous gene-expression analysis and temporal knockout assay show that Msx/vab-15 specifies the lateral neuroblasts at their initial formation and regulates the development of both the CNS and PNS.

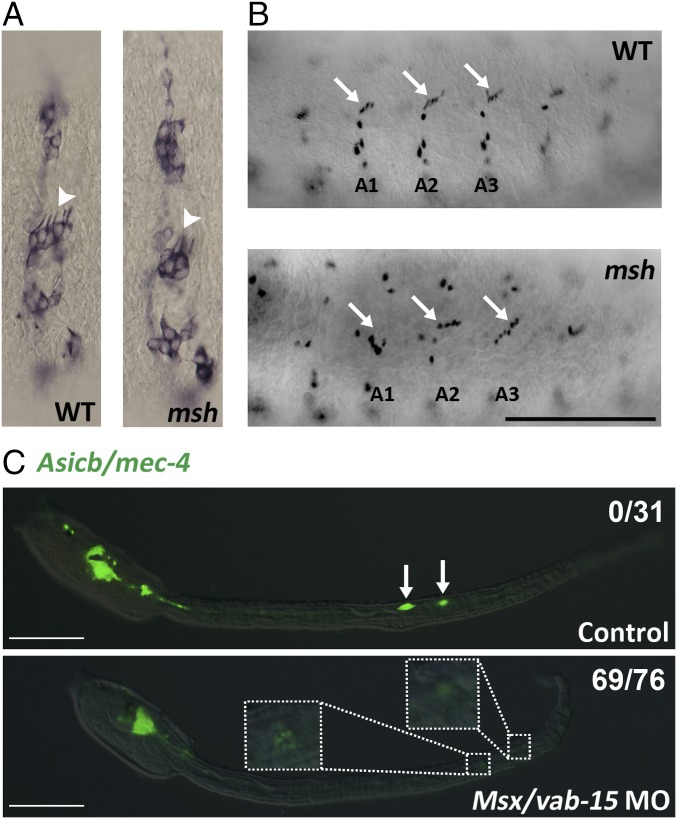

Msx/vab-15 Regulates Development of PNS Derived from Lateral Neuroblasts in Fly.

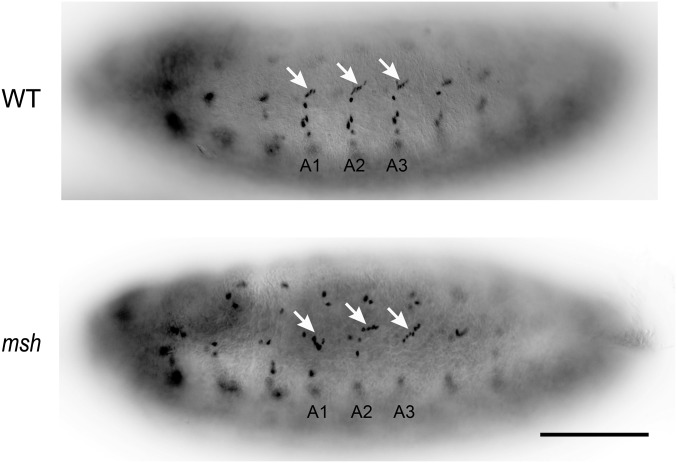

As in nematodes and vertebrates, Msx/vab-15 in D. melanogaster is also expressed in the lateral neural border encompassing both CNS and PNS progenitors (7, 16). Furthermore, fly Msx/vab-15 is a specifier of lateral CNS progenitors (7, 16). To test whether Msx/vab-15 also regulates the PNS in fly, we generated an Msx/vab-15 mutant, msh4-4, in D. melanogaster and focused on the lateral clusters of the mechanosensors, the chordotonal organs. In wild-type Drosophila embryos, each chordotonal organ is made of four cells derived from a single sense organ precursor (SOP) cell, including a neuron, glial cell, and two supporting cells. During PNS development, five SOPs for the chordotonal organs are formed in the Msx/vab-15–expressing domain lateral to the neuroectoderm in each segment (7). The progeny cells of these five SOPs migrate dorsally and give rise to a stretch of five characteristically arranged chordotonal organs (17). However, in msh4-4 mutants, the chordotonal organs contained fewer neurons and glial cells (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the migration of the progeny cells derived from the SOPs in msh4-4 embryos appeared to be significantly desynchronized among different segments, as indicated by the position of the glial cells, whereas in the wild-type embryos these cells migrated to a similar position in all segments (Fig. 4B). So, like its role in nematodes and vertebrates, Msx/vab-15 in fly regulates PNS development in the lateral neural border.

Fig. 4.

Msx/vab-15 is required for the development of worm lateral PNS progenitors in other invertebrates. (A and B) Disrupted chordotonal organs in Msx/vab-15/msh mutant Drosophila embryos. Shown are lateral views of wild-type and msh4-4 embryos at early stage 12 with the anterior side at the left and ventral side at the bottom. (A and B) Neurons in the chordotonal organs are revealed by 22C10 immunostaining (A) and glial cells by Repo staining (B). Pictures of whole embryos are in Fig. S4. Arrowheads indicate a five-neuron array of chordotonal organs in wild type but disorganized with only four neurons in msh4-4. Arrows indicate glial cells in the chordotonal organs. The migration of five glial cells of chordotonal organs is significantly desynchronized, and the glial cell numbers vary in different segments compared with the WT embryos. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (C) Defective BTN differentiation in Msx/vab-15 knockdown Ciona. Examined were larvae whose dorsal sides were up. Arrows point to BTNs. (C, Insets) Enlarged areas in the morpholino-injected larva represent BTNs with the down-regulated Asicb reporter, a marker of BTN mechanosensory neurons. Fractions of scored larvae with down-regulated reporter activity are shown. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

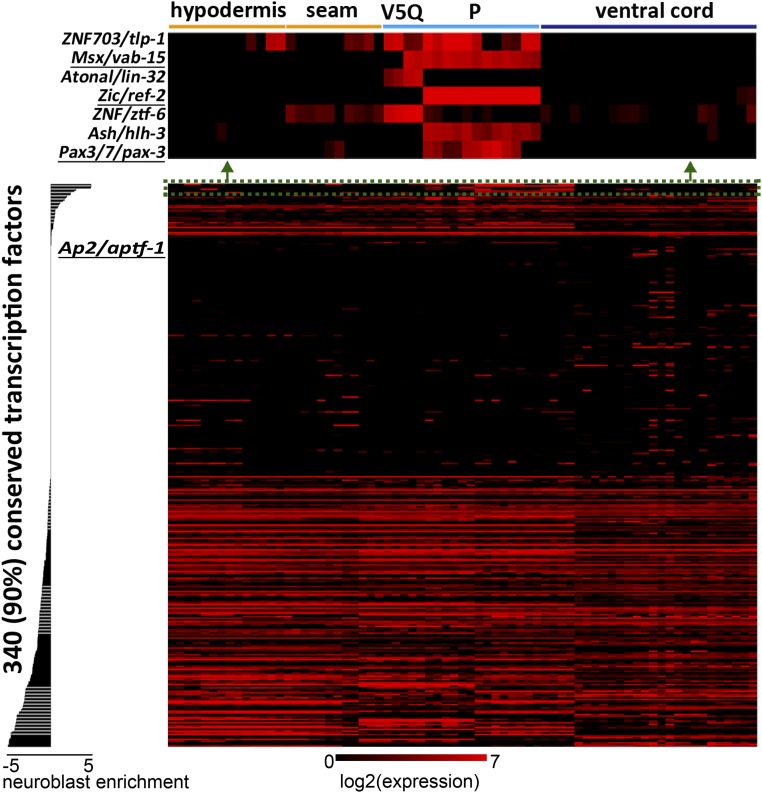

Systematic Prediction of Lateral Neuroblast Regulators in C. elegans.

To comprehensively reveal regulators that distinguish lateral neuroblasts from trunk CNS and the skin cells flanking them, we generated reporter transgenic lines for 339 out of all 377 worm transcription factors that have human orthologs (18) (Dataset S1). Seventy-five percent of our cloned promoters are more than 2-kb-long upstream regions. Other promoters are less than 2 kb, mostly because their upstream intergenic regions are short. It has been demonstrated that 2 kb upstream of a worm gene accurately drives gene expression in most cases (19, 20). Therefore, the majority of our reporters should largely recapitulate endogenous gene expression. We profiled their expression in trunk ectoderm of newly hatched L1 larvae at the resolution of single cells using an imaging analysis pipeline (19) (Fig. 5). The annotation of L1 trunk ectodermal cells is highly reliable because of their well-separated and invariable position and characteristic nuclear morphology (10). All cell annotations were manually verified to be precise.

Fig. 5.

Expression profile of conserved transcription factors in the trunk ectoderm of L1 larvae at single-cell resolution. The data are in Dataset S2. Cells were manually arranged according to their cell types. Genes are ranked according to their neuroblast-enrichment score (see Materials and Methods) in descending order. (Upper) Expression profile of the top-seven neuroblast-enriched genes, which are barely expressed in skin cells and ventral cord motor neurons. Orthologs of vertebrate NPB specifiers are underlined.

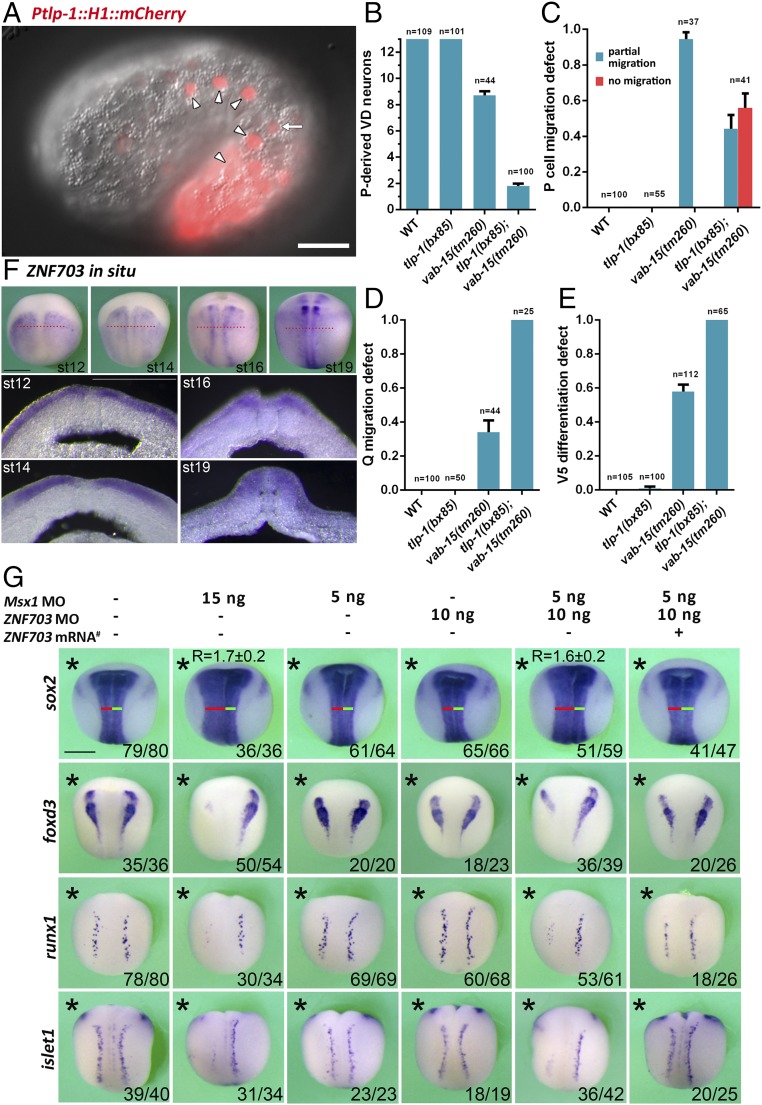

To predict neuroblast regulators, we defined a neuroblast-enrichment score as the logarithmic ratio of expression in neuroblasts over expression in skin or ventral cord motor neurons (Materials and Methods for details). To test the prediction power of our neuroblast-enrichment score, we functionally validated seven top-scored genes: ZNF703/tlp-1, Msx/vab-15, Atonal/lin-32, Zic/ref-2, Znf/ztf-6, Ash/hlh-3, and Pax3/7/pax-3 (Fig. 5). In addition to Msx/vab-15 described in this study, Atonal/lin-32 is a well-known master regulator of Q and V5 neuroblast development (21, 22). Our genetic analysis showed that Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2 are required for both migration and differentiation of P nuclei (Fig. 2 and Table 1). However, mutants of the other three candidates (ZNF703/tlp-1, Ash/hlh-3, and Znf/ztf-6) show a weak to marginal phenotype (Table 1). ZNF703/tlp-1 is expressed both in P neuroblasts and the mother cells of V5 and Q, similar to Msx/vab-15 (Figs. 5 and 6A), so we further investigated the genetic interaction between ZNF703/tlp-1 and Msx/vab-15. Although P neuroblasts appear, there are no phenotypes in ZNF703/tlp-1 single mutants. But P neuroblasts in ZNF703/tlp-1;Msx/vab-15 double mutants show a stronger defect in migration and differentiation than those in Msx/vab-15 single mutants (Fig. 6 B and C). Q neuroblasts display little migration defect in ZNF703/tlp-1 single mutants, whereas ZNF703/tlp-1;Msx/vab-15 double mutants showed a stronger phenotype than Msx/vab-15 single mutants (Fig. 6D). Significant synergistic effect was also observed upon V5 differentiation (Fig. 6E). Therefore, ZNF703/tlp-1 is a novel neuroblast regulator that functions as a modulator of Msx/vab-15 activity in worms. These data demonstrated that the neuroblast-enrichment score is strongly related to the molecular mechanisms specifying worm lateral neural precursor cells. Then, examining the correlation between the worm neuroblast-enrichment score and orthologs of the NPB specification module can suggest the conservation between the worm lateral neuroblasts and the vertebrate NPB.

Fig. 6.

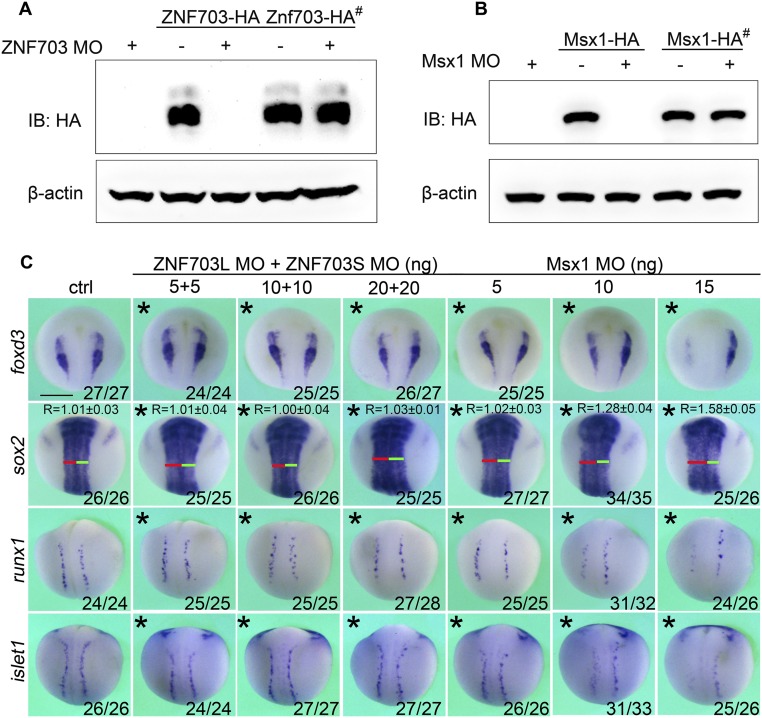

ZNF703/tlp-1 is a novel regulator functioning as an Msx/vab-15 modulator both in worm lateral neuroblasts and vertebrate NPB. (A) Embryonic expression of worm ZNF703/tlp-1. A comma-stage embryo carrying the Ptlp-1::H1::mCherry reporter trangene is shown. Arrowheads indicate P neuroblasts. Arrow indicates the mother cell of V5 and Q neuroblasts. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B–E) Phenotypes of ZNF703/tlp-1 and Msx/vab-15 mutant worms of migration and differentiation of lateral neuroblasts. The y axis represents the number of VD neurons recognized by the Punc-25::GFP marker (B) or the fraction of worms showing the specified defect (C–E). The number of scored worms is shown. (F) The expression of ZNF703 in Xenopus embryos from stage (st)12 to st19. (Scale bar, 0.5 mm.) The red dot lines represent the location of cross section. (G) Whole-mount in situ hybridization assay in Xenopus embryos (st16 to st17) to examine the effect of MO knockdown of Msx/vab-15 and/or ZNF703/tlp-1 on the expression of the neural plate marker Sox2, neural crest specifier FoxD3, and Rohon–Beard sensory neuron progenitor marker Runx1 and DRG progenitor marker Islet1. Asterisks indicate the injected side of an embryo. The red lines and green lines indicate the length of left and right parts of neural tubes, respectively. # indicates mRNA resistant to the ZNF703 MO. Fractions of scored embryos with phenotype are shown. (Scale bar, 0.5 mm.) Error bars represent standard errors.

The NPB Specification Module Is Conserved Between Worm and Chordates.

A conserved four-gene NPB specification module (Msx/vab-15, Pax3/7/pax-3, Zic/ref-2, and AP2/aptf-1) establishes the identity of the NPB from jawless fish lamprey to mouse (11, 23). This gene set has neuroblast-enrichment scores significantly higher than those of other genes (Mann–Whitney test based on neuroblast-enrichment score, P value < 1.8 × 10−4). Actually, three out of these four genes are among the top-seven neuroblast-enriched genes (Fig. 5). Although the expression patterns of these three NPB specifiers (Msx/vab-15, Pax3/7/pax-3, and Zic/ref-2) are overlapping, the expression domain of Msx/vab-15 in many bilaterians expands more laterally than those of Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2 (8, 24). Consistently, only Msx/vab-15, but not Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2, is expressed and plays a critical role in the most lateral V5 and Q neuroblasts, which are PNS progenitors in worm (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Another example of more lateral Msx/vab-15 expression exists in the urochordate C. intestinalis. Two NPB cells (b8.18 and b8.21) give rise to BTNs, which are likely the counterparts to vertebrate dorsal root ganglion (DRG) mechanosensory neurons (9). These two NPB cells express Msx/vab-15 and Pax3/7/pax-3 but not Zic/ref-2 (9, 25). Nevertheless, our gene-knockdown experiments showed that Msx/vab-15 is required for BTN differentiation (Fig. 4C). Therefore, Msx/vab-15 regulates the development of the PNS from the lateral neural border in both Protostomia and Deuterostomia, regardless of the coexistence of other NPB specifiers such as Zic/ref-2.

ZNF703/tlp-1 Is a Novel NPB Specifier in X. laevis.

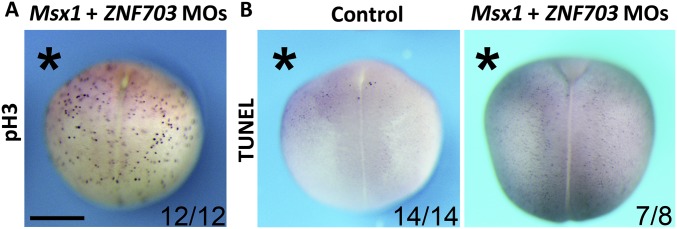

We have identified ZNF703/tlp-1 as a novel regulator of lateral neuroblasts cooperating with Msx/vab-15 in C. elegans. To investigate whether ZNF703/tlp-1 has conserved function in vertebrates, we examined its expression and function in X. laevis. In situ RNA hybridization showed that ZNF703/tlp-1 is expressed at the posterior ectoderm except for the dorsal midline in frog gastrulae. During neurulation, the expression of ZNF703/tlp-1 in nonneurogenic lateral ectoderm diminishes so as to become enriched in the NPB and neural crest (Fig. 6F). As in C. elegans, disturbing ZNF703/tlp-1 alone has no detectable phenotype. But moderate knockdown of both ZNF703/tlp-1 and Msx/vab-15 significantly down-regulates the trunk expression of the neural crest specifier FoxD3, migratory DRG progenitor marker islet1, and nonmigratory Rohon–Beard mechanosensory neuron progenitor marker Runx1 (Fig. 6G), with no detectable effect on cell proliferation or apoptosis (Fig. S2). High dosage Msx/vab-15 morpholino blocks the differentiation of NPB in Xenopus, while low dosage does not (Fig. 6G and Fig. S3). Hence, ZNF703/tlp-1 acts as a modulator of Msx/vab-15 in both worm lateral neuroblasts and the vertebrate NPB, supporting our hypothesis on the conservation of the gene regulatory module specifying the lateral neural border across bilaterians.

Fig. S2.

Little effect on cell proliferation (A) and apoptosis (B) of Xenopus embryos by the moderate double knockdown of Msx/vab-15 and ZNF703/tlp-1. pH3, phosphorylated histone H3Serine10 as a cell proliferation marker. TUNEL, apoptosis marker. Embryos are viewed from the dorsal side with anterior on top. Asterisks indicate the morpholino injection side. (Scale bar, 0.5 mm.)

Fig. S3.

Assessment of effects of ZNF703 and Msx1 depletion in Xenopus. (A) Immunoblots (IBs) showing that ZNF703 MO efficiently blocks translation of an MO-complementary Znf703-HA mRNA but not an MO-resistant Znf703-HA# mRNA. (B) Immunoblots showing that Msx1 MO efficiently blocks translation of an MO-complementary Msx1-HA mRNA but not an MO-resistant Msx1-HA# mRNA. β-Actin serves as a loading control in A and B. (C) Depletion of ZNF703 alone through injecting a mix of MOs up to 40 ng has no discernable effects on the expression of foxd3, sox2, runx1, and islet. However, depletion of Msx1 using 10 to 15 ng MO discernably decreased the expression of foxd3, runx1, and islet1 and expanded the expression domain of sox2. Asterisks indicate the injected side of an embryo. (Scale bar, 0.5 mm.)

Discussion

An important feature of Bilateria is the centralized nervous system, in which the CNS in the head and trunk midline integrates and processes sensory information from the PNS. Developmental processes to generate centralized nervous systems differ dramatically among different bilaterian phyla. In nematodes such as C. elegans, cell fate is coupled with cell lineage and neurogenesis is multiclonal; that is, many independent progenitor cells give rise to neurons (6, 10). However, in vertebrate gastrulae, accompanying the determination of the dorsoventral axis by BMP signaling, ectoderm in the dorsal midline thickens to form a neural plate, from which their CNS is derived. Between the neural plate and nonneurogenic ectoderm are the NPB and PPE, from which the majority of the vertebrate PNS is derived (24). How nervous system centralization patterns come into being is a long-standing question in neural development and evolution (3, 26).

Regarding the molecular mechanisms determining CNS development, comparative studies have provided evidence that the CNS of vertebrates, annelids, and arthropods originated from a common bilaterian ancestor (8, 27). For example, both the neuroectoderm of annelids and neural plate of vertebrates are subdivided into a sim/hlh-34–expressing midline and longitudinal Nk2.2/ceh-22–, Nkx6/cog-1–, Pax6/vab-3–, Pax3/7/pax-3–, and Msx/vab-15–expressing domains from medial to lateral, likely representing the molecular architecture of trunk CNS in their last common ancestor, Urbilateria (8). However, there has been debate on the common origin of CNS centralization because some sister or outgroup species of annelids, arthropods, and chordates lack a centralized ventral cord (26, 28). For example, hemichordates differ from major chordates by possessing a diffuse nervous system and do not have mediolateral neural patterning (29). Characterization of the molecular mechanisms of neural patterning in distantly related bilaterians should provide a broader view of the evolution of nervous system centralization (28).

Nematodes diverged from arthropods about 550 Mya, close to the origin of Ecdysozoa (30). Unlike annelids and arthropods, nematodes have an unsegmented body plan and no appendages. C. elegans burrows in rotten matter and has a feeding organ isolated from the rest of the animal (31, 32). Correspondingly, its nervous system is more modestly organized than those in annelids and arthropods. The complex mediolateral patterning of trunk CNS is largely absent in worm, where there are only motor neurons in its ventral cord. Nevertheless, Pax3/7/pax-3 and Msx/vab-15 still express in the lateral border of the CNS neuroectoderm in worm (15, 33), consistent with the conserved expression patterns of these two lateral genes in arthropods, annelids, and chordates (8). Our genetic analysis shows that both Msx/vab-15 and Pax3/7/pax-3 specify P neuroblasts, which are worm CNS progenitors, similar to their roles in the lateral CNS progenitors in fly and vertebrates (11, 16, 34–36). Combining our data with the existing evidence of the common origin of trunk CNS from fly to vertebrates (8, 27), it is more likely that nematodes inherited the Msx/vab-15 specification of P neuroblasts from Urbilateria than the nematode branch lost the conserved lateral domain after diverging from fly and then regenerated it independently.

In addition to the conserved CNS molecular module shown in C. elegans, our data suggest that the molecular mechanism defining the lateral neural border, from which the majority of the PNS is derived, is also conserved across bilaterians. First, the lateral neural borders in nematodes, fly, annelids, and urochordates show conserved neural patterning where the medial portion of the Msx/vab-15–expressing domain gives rise to the CNS whereas the lateral portion generates the PNS. Second, their lateral PNS progenitors exhibit several key features of vertebrate PNS progenitors, such as migration and differentiation into mechanosensory neurons (7, 8, 10, 13, 34). Our genetic analysis also shows that Msx/vab-15 specifies these PNS progenitors in nematodes, fly (Fig. S4), and urochordates, similar to its role in the vertebrate NPB and PPE. The PPE is the neurogenic ectoderm anterolateral to the NPB, and is considered the epidermal subdomain of the vertebrate neural border that mostly contributes to cranial sensory systems (1, 37). The PPE also gives rise to mechanosensing hair cells of lateral lines in the trunk of anamniote vertebrates and those in vertebrate inner ears (1). The development of the mechanosensing hair cells in vertebrates and that of the mechanosensory neurons in worm and fly both depend on Atoh1/lin-32 (22, 38). On the contrary, Ciona BTNs and vertebrate DRG neurons require Neurogenin/ngn-1 (9). Hence, more molecular and comparative studies are needed to understand the evolutionary relationship of these mechanosensing cell types. Nevertheless, our study on the neural borders suggests the conservation of the molecular mechanism underlying the specification of PNS progenitors across bilaterians (39).

Fig. S4.

Disrupted chordotonal organs in Msx/vab-15/msh mutant Drosophila embryos. Shown are the lateral view of wild-type and msh4-4 embryos at early stage 12 with anterior side on the left and ventral side at the bottom. Glial cells in the chordotonal organs are revealed by Repo staining. Arrows indicate glial cells in the chordotonal organs. (Scale bar, 100 µm.)

In theory, the similarity between the invertebrate and vertebrate lateral neural border can be explained by either common origin or convergence of independent evolution. To distinguish between these two hypotheses, it is necessary to compare molecular mechanisms specifying lateral neural borders in various bilaterians. Unlike the vertebrate NPB and neural crest, the molecular mechanism underlying the specification of worm lateral neuroblasts still remains largely unknown after years of genetic study (33, 40, 41). Our systematic expression profiling of 90% conserved transcription factors in C. elegans revealed that three NPB specifiers (Msx/vab-15, Pax3/7/pax-3, and Zic/ref-2) are coexpressed in worm lateral neuroblasts and that Msx/vab-15 expression is more lateral than that of Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2, like their expression patterns in neural borders of vertebrates, urochordates, amphioxus, and likely annelids (7, 8, 11, 13, 24). Furthermore, we showed that Msx/vab-15 regulates the differentiation of PNS progenitors in worm and fly, similar to its critical role in specifying PNS lineage in urochordates and vertebrates. We noticed that in PNS specification, only the role of Msx/vab-15 is conserved in worm, but not the other two NPB specifiers, Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2. This is not totally surprising because there have been indications that the expression and function of Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2 are not strictly conserved in the evolution of PNS development. For example, whereas Pax3/7/pax-3 is expressed in the lateral domain in both annelids and nematodes (8, 33), it is active in transverse stripes in fly (27). In addition, Pax3/7/pax-3 is only marginally expressed in the putative PNS progenitor region in annelids (8). Their expression even varies within vertebrates. Pax3/7/pax-3 and Zic/ref-2 expression domains are significantly more medial in lamprey (11) than those in zebrafish (42). Also, in Ciona, the NPB cells that give rise to mechanosensory BTNs do not express Zic/ref-2 (25). Therefore, our data, consistent with other studies, showed that only Msx/vab-15, but not other NPB specifiers, exhibits conserved expression and a functional role in PNS progenitors across bilaterians (3, 43). Finally, we have identified a novel lateral neural border specifier, ZNF703/tlp-1, and demonstrated that it functions synergistically with Msx/vab-15 in regulating the migration and differentiation of lateral neural progenitor cells in both C. elegans and Xenopus. Altogether, our data revealed deep conservation of vertebrate NPB specifiers’ module composition, expression pattern, and regulatory role in neural border development among distantly related species with drastically different neural anatomy, favoring the common origin hypothesis in the molecular mechanism underlying neural border specification.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans-Related Procedures.

Orthologous gene pairs.

Orthologous gene pairs were obtained from a previous publication (18) or annotation in WormBase (www.wormbase.org) or TreeFam (www.treefam.org). A 1:N ortholog relationship is allowed.

C. elegans strains and reporter transgenes.

Mutant strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center or National BioResource Project of Japan. vab-15 mutants: TU2362(u781), FX0260(tm260); tlp-1 mutant: EM347(bx85); lin-32 mutant: FXO1446(tm1446); dat-1 reporter: BZ555(Pdat-1::GFP). Promoter reporter constructs and their transgenic strains were generated as described (19, 44), and their description can be found in Dataset S1. vab-15::GFP knockin strain was generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system as described (45). mec-10 reporter (Pmec-10::H1::mCherry) was generated through mosSCI insertion (46). Primer sequences of mec-10 promoter: 5′-accgaaagatgcacgtccta-3′ and 5′-ATATTGTGGTCCAGCTCTCACACTG-3′.

Somatic knockout.

Somatic KO was conducted as described (47). Guide RNA sequences: vab-15, 5′-GTGAATGTTGCATAGACAG-3′; pax-3, 5′-GTCGTGTTAACCAACTCGG-3′; ref-2, 5′-CTTGGGCTGGAAGAAAGTG-3′. These sequences were cloned into the vector pOG2306 (47). Each vector was injected into worms mixed with the Pmyo-2::GFP coinjection marker. Synchronized embryos of transgenic strain were transferred to OP50-seeded nematode growth medium (NGM) plates and heat shocked as described, at 33 °C for 1 h (47). The embryos then grew at 20 °C until L2 stage.

Imaging protocol.

Larvae that grew for no more than 4 h after hatching were considered to be at early L1 stage. Larvae whose neuronal lineage P neuroblasts finished cell division and whose gonad was composed of about 50 cells were considered to be at L2 stage. For live imaging, worms were placed on a 2% agarose pad and immobilized using levamisole (2.5 mg/mL). Images were captured using a Zeiss Imager A2 epifluorescence microscope. For 3D imaging, collected worms were frozen in liquid nitrogen for a night. Frozen worms were thawed in 200 μL acetone. Then, the acetone was discarded and the worms were fixed with a solution composed of 1× modified Ruvkun’s witches brew and 20% formalin for 1.5 h, and then proceeded to DAPI staining and 60% glycerol mounting as described (19). Three-dimensional images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope. The pixel size was 0.132 µm in the x-y plane and 0.300 µm in the z direction.

Cell annotation of 3D image stacks of L1 larvae.

The 3D image stacks of worms were straightened computationally along the anterior–posterior axis. Their cell nuclei were segmented and annotated, and then manually edited with the VANO interactive interface as described (19). The identities of hyp7 hypodermal nuclei, seam cells, ventral cord motor neurons, neuroblasts, and their progeny’s nuclei were manually confirmed according to WormAtlas (www.wormatlas.org) (10).

Gene-expression measurement.

The gene-expression level for every cell was measured as described (19). Briefly, background fluorescence was estimated using 10 pseudonuclei. After subtracting background fluorescence, mCherry fluorescence was normalized by DAPI fluorescence to account for spherical aberration. A nucleus with a normalized mCherry fluorescence of 500 was often barely distinguishable from background red fluorescence according to visual inspection. To become robust to background, gene expression was calculated as (normalized mCherry fluorescence + 500)/500.

Neuroblast-enrichment score.

For each gene, we calculated its median log2 expression level for hypodermal cell group (hyp7, V1 to V4, plus V6), lateral neuroblast group (Q, P, V5), and ventral cord motor neuron (VMN) (Dataset S2). Mean (MedianP, MedianQ) − Max (Medianhyp7, MedianV, MedianVMN) represents the neuroblast-enrichment score of a gene.

Embryo-lineage tracing.

vab-15 mutant strain TU2362(u781) was crossed with RW10029 (zuIs178; stIs10024) (48), which carries the his-72::GFP transgene so that all somatic nuclei become detectable during embryogenesis. Then, one- to four-cell-stage embryos were transferred onto an agarose pad for imaging. We performed confocal imaging with an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope. Embryo-lineage tracing and imaging were processed as described (49). The u781 mutant is edited up to 200 time points with 398 cells.

D. melanogaster-Related Procedures.

Generation of Drosophila mutant.

Msh mutant was generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 method (50) and guide sequence 5′-GGCTAGGACTCAGGTTGGTC-3′ targeting the N-terminal msh coding region. Msh4-4 contains a single-nucleotide insertion at position 185 of the ORF so that it is a frameshift allele and produces a truncated MSH protein of only 67 amino acids.

Immunocytochemistry and microscopy.

Embryos were fixed and stained as previously described (51). Rat anti-Repo was from A. Tomlinson (Columbia University, New York). Embryos were observed using differential interference contrast optics with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope.

X. laevis-Related Procedures.

Frogs were used with ethical approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tsinghua University.

Xenopus whole-mount in situ hybridization.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed based on standard protocols (52, 53). cDNA sequences for ZNF703, Runx1, Islet1, and Sox2 were cloned into the vector pCS107 (www.xenbase.org). Primer sequences were as follows: ZNF703: 5′-TCCatcgatATGAACTGTTCTCCCCCTGGATCT-3′ and 5′-cacGTCGACctggtatcctagcgctgaagctg-3′; Runx1: 5′-tccATCGATATGGCCTCACATAGTGCCTTCCA-3′ and 5′-gagcCTCGAGtcagtatggccgccatacggctt-3′; Islet1: 5′-cgcGAATTCatgggagatatgggagaccca-3′ and 5′-gagcCTCGAGtgcctctatagggctggctaccatg-3′; and Sox2: 5′-gagaGAATTCatgtacagcatgatggagaccgag-3′ and 5′-gcgcctcgagtcacatgtgcgacagaggcagcgtgcc-3′. In situ probes were labeled with Dig-UTP using a Promega T7 polymerase kit.

Xenopus embryo manipulation and microinjection.

Xenopus eggs and embryos were obtained through standard procedures (54). Briefly, eggs harvested from HCG-injected female frogs were fertilized through artificial insemination techniques. Fertilized eggs were dejellied using 2% cysteine prepared in 0.1× Marc’s modified Ringer’s (MMR) (pH 7.9), followed by a thorough wash with 0.1× MMR. The dejellied embryos were then transferred into 2% Ficoll in 0.5× MMR for morpholino (MO) and/or mRNA injection.

The MO sequences were as follows: Msx1: 5′-GCCATACAGAGAGATCCGAGCTGAG-3′; ZNF703a: 5′-ACCAGGGCGCAAAGATTCCCCTTGT-3′; and ZNF703b: 5′-ACCAGGGCGCGGAGATTCCCCTTAT-3′.

All MOs are purchased from Gene Tools. ZNF703 MO was a mixture of 5 ng ZNF703a MO and 5 ng ZNF703b MO per embryo. Msx1 MO and/or ZNF703 MO mixed with 2 ng RLDx as lineage tracer were injected into the animal-pole two left-side cells at the eight-cell stage. For rescue experiments, after MO injection, ZNF703 mRNA was immediately injected into the same two cells before the needle hole cured. Beta-gal mRNA was coinjected as a lineage tracer in the ZNF703 mRNA-alone group. The right-injected embryos were sorted out under a fluorescence dissecting microscope (Olympus; SZX16) and cultured to stages 16 to 17. Embryos were fixed in Mops EGTA MgSO4 formaldehyde (MEMFA) solutionin for 4 h at room temperature followed by whole-mount in situ hybridization. ZNF703 mRNA (mixed with beta-gal)-injected embryos were stained by red-gal before in situ hybridization.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as described previously (55). Briefly, Xenopus embryos were lysed in TNE buffer (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) plus protease inhibitors, and pipetted several times on ice. Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min. Supernatant was mixed with loading buffer and boiled for 15 min followed by SDS/PAGE separation. Primary antibody of HA (Roche; 1:2,000 dilution) and primary antibody of β-actin (1:5,000 dilution) were used.

C. intestinalis-Related Procedures.

C. intestinalis adults were obtained from M-Rep. Sperm and eggs were collected by dissecting the sperm and gonad ducts.

Construct.

The Asicb reporter construct was designed based on the previously published enhancer sequence (56).

Microinjection of antisense morpholino oligonucleotide.

MOs were obtained from Gene Tools. The antisense oligonucleotide sequence of the Msx MO is 5′-ATTCGTTTACTGTCATTTTTAATTT-3′. The MO was dissolved at a concentration of 0.5 mM in 1 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mg/mL tetramethylrhodamine dextran (D-1817; Invitrogen). Microinjection of MO was performed as described previously (57).

Image acquisition.

Images of larvae were captured using a Zeiss AX10 epifluorescence microscope.

Statistics.

Wilcoxon and Mann–Whitney tests, robust statistics tests with no assumption on the distribution of samples, were used to examine whether a set of worm genes orthologous to a vertebrate gene module had significantly higher neuroblast-enrichment or mechano-enrichment scores. In genetics and gene-knockdown analyses, Fisher’s exact test was used under the assumption that the fraction of animals with a phenotype followed binomial distribution, and a t test was used when a quantitative phenotype was scored under the assumption that the quantitative phenotype followed normal distribution. Variation was calculated based on binomial or normal distribution, and the similarity of variations was not assumed to decrease the false positive rate. The minimum number of scored animals was 22 in one batch analyzed, whereas the maximum was 300.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Haidong Li from the Center of Biomedical Analysis, Tsinghua University for confocal imaging, and Lei Qu and Hanchuan Peng for processing imaging data. Drs. Cecilia Mello and Robert Waterston edited the manuscript. Dr. Dionne Vafeados provided transgenic worms. We are very grateful to Drs. Martin Chalfie, Andy Fire, David Kingsley, Chris Amemiya, Xiaohang Yang, Ding Xue, Zhirong Bao, Margaret Fuller, and Joanna Wysocka for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China Grant 20131970194; National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 20141300429 and 91519326; Tsinghua 985 funding; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from JSPS Grant 24687008; and Pre-Strategic Initiatives, University of Tsukuba.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1704194114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schlosser G, Patthey C, Shimeld SM. The evolutionary history of vertebrate cranial placodes II. Evolution of ectodermal patterning. Dev Biol. 2014;389:98–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medeiros DM. The evolution of the neural crest: New perspectives from lamprey and invertebrate neural crest-like cells. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2013;2:1–15. doi: 10.1002/wdev.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green SA, Simoes-Costa M, Bronner ME. Evolution of vertebrates as viewed from the crest. Nature. 2015;520:474–482. doi: 10.1038/nature14436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milet C, Monsoro-Burq AH. Neural crest induction at the neural plate border in vertebrates. Dev Biol. 2012;366:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlosser G. Do vertebrate neural crest and cranial placodes have a common evolutionary origin? BioEssays. 2008;30:659–672. doi: 10.1002/bies.20775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Alessio M, Frasch M. msh may play a conserved role in dorsoventral patterning of the neuroectoderm and mesoderm. Mech Dev. 1996;58:217–231. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denes AS, et al. Molecular architecture of annelid nerve cord supports common origin of nervous system centralization in bilateria. Cell. 2007;129:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolfi A, Ryan K, Meinertzhagen IA, Christiaen L. Migratory neuronal progenitors arise from the neural plate borders in tunicates. Nature. 2015;527:371–374. doi: 10.1038/nature15758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauka-Spengler T, Meulemans D, Jones M, Bronner-Fraser M. Ancient evolutionary origin of the neural crest gene regulatory network. Dev Cell. 2007;13:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos C, Robert B. msh/Msx gene family in neural development. Trends Genet. 2005;21:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abitua PB, Wagner E, Navarrete IA, Levine M. Identification of a rudimentary neural crest in a non-vertebrate chordate. Nature. 2012;492:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature11589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharman AC, Shimeld SM, Holland PW. An amphioxus Msx gene expressed predominantly in the dorsal neural tube. Dev Genes Evol. 1999;209:260–263. doi: 10.1007/s004270050251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du H, Chalfie M. Genes regulating touch cell development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;158:197–207. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isshiki T, Takeichi M, Nose A. The role of the msh homeobox gene during Drosophila neurogenesis: Implication for the dorsoventral specification of the neuroectoderm. Development. 1997;124:3099–3109. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orgogozo V, Grueber WB. FlyPNS, a database of the Drosophila embryonic and larval peripheral nervous system. BMC Dev Biol. 2005;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaye DD, Greenwald I. OrthoList: A compendium of C. elegans genes with human orthologs. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, et al. Analysis of cell fate from single-cell gene expression profiles in C. elegans. Cell. 2009;139:623–633. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reece-Hoyes JS, et al. Insight into transcription factor gene duplication from Caenorhabditis elegans Promoterome-driven expression patterns. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Z, et al. A proneural gene controls C. elegans neuroblast asymmetric division and migration. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1136–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao C, Emmons SW. A transcription factor controlling development of peripheral sense organs in C. elegans. Nature. 1995;373:74–78. doi: 10.1038/373074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikitina N, Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M. Dissecting early regulatory relationships in the lamprey neural crest gene network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20083–20088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806009105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland LZ. Chordate roots of the vertebrate nervous system: Expanding the molecular toolkit. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:736–746. doi: 10.1038/nrn2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imai KS, Levine M, Satoh N, Satou Y. Regulatory blueprint for a chordate embryo. Science. 2006;312:1183–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.1123404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strausfeld NJ, Hirth F. Introduction to ‘Homology and convergence in nervous system evolution.’. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371:20150034. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arendt D, Nübler-Jung K. Comparison of early nerve cord development in insects and vertebrates. Development. 1999;126:2309–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hejnol A, Lowe CJ. Embracing the comparative approach: How robust phylogenies and broader developmental sampling impacts the understanding of nervous system evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20150045. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe CJ, et al. Dorsoventral patterning in hemichordates: Insights into early chordate evolution. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rota-Stabelli O, Daley AC, Pisani D. Molecular timetrees reveal a Cambrian colonization of land and a new scenario for ecdysozoan evolution. Curr Biol. 2013;23:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen C, Dirksen P, Prahl S, Strathmann EA, Schulenburg H. The prevalence of Caenorhabditis elegans across 1.5 years in selected north German locations: The importance of substrate type, abiotic parameters, and Caenorhabditis competitors. BMC Ecol. 2014;14:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-14-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albertson DG, Thomson JN. The pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1976;275:299–325. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1976.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson KW, et al. The paired-box protein PAX-3 regulates the choice between lateral and ventral epidermal cell fates in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2016;412:191–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Chen X, Xu H, Lufkin T. Msx3: A novel murine homologue of the Drosophila msh homeobox gene restricted to the dorsal embryonic central nervous system. Mech Dev. 1996;58:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duval N, et al. Msx1 and Msx2 act as essential activators of Atoh1 expression in the murine spinal cord. Development. 2014;141:1726–1736. doi: 10.1242/dev.099002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin J, Wang C, Yang C, Fu S, Redies C. Pax3 and Pax7 interact reciprocally and regulate the expression of cadherin-7 through inducing neuron differentiation in the developing chicken spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2016;524:940–962. doi: 10.1002/cne.23885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abitua PB, et al. The pre-vertebrate origins of neurogenic placodes. Nature. 2015;524:462–465. doi: 10.1038/nature14657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arendt D, et al. The origin and evolution of cell types. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:744–757. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fritzsch B, Beisel KW, Pauley S, Soukup G. Molecular evolution of the vertebrate mechanosensory cell and ear. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:663–678. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072367bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng G, et al. Developmental stage-dependent transcriptional regulatory pathways control neuroblast lineage progression. Development. 2013;140:3838–3847. doi: 10.1242/dev.098723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wrischnik LA, Kenyon CJ. The role of lin-22, a hairy/enhancer of split homolog, in patterning the peripheral nervous system of C. elegans. Development. 1997;124:2875–2888. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garnett AT, Square TA, Medeiros DM. BMP, Wnt and FGF signals are integrated through evolutionarily conserved enhancers to achieve robust expression of Pax3 and Zic genes at the zebrafish neural plate border. Development. 2012;139:4220–4231. doi: 10.1242/dev.081497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waki K, Imai KS, Satou Y. Genetic pathways for differentiation of the peripheral nervous system in ascidians. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8719. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray JI, et al. Multidimensional regulation of gene expression in the C. elegans embryo. Genome Res. 2012;22:1282–1294. doi: 10.1101/gr.131920.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickinson DJ, Ward JD, Reiner DJ, Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frøkjær-Jensen C, et al. Random and targeted transgene insertion in Caenorhabditis elegans using a modified Mos1 transposon. Nat Methods. 2014;11:529–534. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen Z, et al. Conditional knockouts generated by engineered CRISPR-Cas9 endonuclease reveal the roles of coronin in C. elegans neural development. Dev Cell. 2014;30:625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray JI, et al. Automated analysis of embryonic gene expression with cellular resolution in C. elegans. Nat Methods. 2008;5:703–709. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho VWS, et al. Systems-level quantification of division timing reveals a common genetic architecture controlling asynchrony and fate asymmetry. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:814. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gratz SJ, et al. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–1035. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang X, Yeo S, Dick T, Chia W. The role of a Drosophila POU homeo domain gene in the specification of neural precursor cell identity in the developing embryonic central nervous system. Genes Dev. 1993;7:504–516. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lander R, et al. Interactions between Twist and other core epithelial-mesenchymal transition factors are controlled by GSK3-mediated phosphorylation. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1542. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Ding Y, Chen YG, Tao Q. NEDD4L regulates convergent extension movements in Xenopus embryos via Disheveled-mediated non-canonical Wnt signaling. Dev Biol. 2014;392:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sive HL, Grainger RM, Harland RM. 2000. Early Development of Xenopus laevis: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY)

- 55.Gao L, et al. A novel role for Ascl1 in the regulation of mesendoderm formation via HDAC-dependent antagonism of VegT. Development. 2016;143:492–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.126292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coric T, Passamaneck YJ, Zhang P, Di Gregorio A, Canessa CM. Simple chordates exhibit a proton-independent function of acid-sensing ion channels. FASEB J. 2008;22:1914–1923. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Satou Y, Imai KS, Satoh N. Action of morpholinos in Ciona embryos. Genesis. 2001;30:103–106. doi: 10.1002/gene.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duggan A, Ma C, Chalfie M. Regulation of touch receptor differentiation by the Caenorhabditis elegans mec-3 and unc-86 genes. Development. 1998;125:4107–4119. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang M, Chalfie M. Gene interactions affecting mechanosensory transduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1994;367:467–470. doi: 10.1038/367467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.