Significance

Fiber materials have great impact on our daily lives, with their use ranging from textiles to functional reinforcements in composites. Although the manufacturing process of manmade fibers is potentially limited by extensive energy consumption, spiders can readily spin silk fibers at room temperature. Here, we report a class of material that is based on a self-assembled hydrogel constructed with dynamic host–guest cross-links between functional polymers. Supramolecular fibers can be drawn from this hydrogel at room temperature. The supramolecular fiber exhibits better tensile and damping properties than conventional regenerated fibers, such as viscose, artificial silks, and hair. Our approach offers a sustainable alternative to current fiber manufacturing strategies.

Keywords: supramolecular fiber, hydrogel, self-assembly, damping, spider silk

Abstract

Inspired by biological systems, we report a supramolecular polymer–colloidal hydrogel (SPCH) composed of 98 wt % water that can be readily drawn into uniform (6-m thick) “supramolecular fibers” at room temperature. Functionalized polymer-grafted silica nanoparticles, a semicrystalline hydroxyethyl cellulose derivative, and cucurbit[8]uril undergo aqueous self-assembly at multiple length scales to form the SPCH facilitated by host–guest interactions at the molecular level and nanofibril formation at colloidal-length scale. The fibers exhibit a unique combination of stiffness and high damping capacity (60–70%), the latter exceeding that of even biological silks and cellulose-based viscose rayon. The remarkable damping performance of the hierarchically structured fibers is proposed to arise from the complex combination and interactions of “hard” and “soft” phases within the SPCH and its constituents. SPCH represents a class of hybrid supramolecular composites, opening a window into fiber technology through low-energy manufacturing.

In nature, spiders spin silk fibers with superb properties at ambient temperatures and pressures (1, 2). We have yet to mimic such an elegant process. Conventionally, synthetic fibers are manufactured through a variety of spinning techniques, including wet, dry, gel, and electrospinning (3). Such approaches to generate fibers are limited by high energy input, laborious procedures, and intensive use of organic solvents. Supramolecular pathways enable the formation of filamentous soft materials that are showing promise in biomedical applications (4–6), such as cell culture (7–9) and tissue engineering (10). However, such materials are constrained by the length scale (submicrometer level) (11–13), energy intake during production (9), and complex design of assembly units (14).

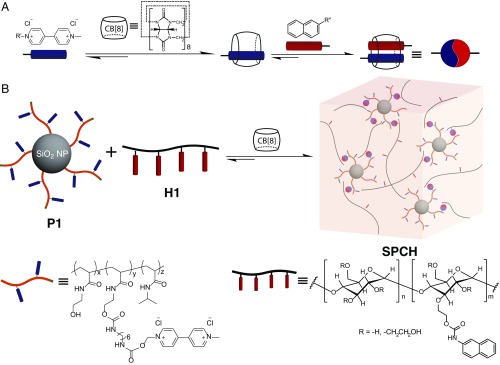

Here, we report drawing supramolecular fibers of arbitrary length from a dynamic supramolecular polymer–colloidal hydrogel (SPCH) at room temperature (Movie S1). The components consist of methyl viologen (MV)-functionalized polymer-grafted silica nanoparticles (P1), a semicrystalline polymer in the form of a hydroxyethyl cellulose derivative (H1), and cucurbit[8]uril (CB[8]) as illustrated in Fig. 1. The macrocycle CB[8] is capable of simultaneously encapsulating two guests within its cavity, forming a stable yet dynamic ternary complex, and has been exploited as a supramolecular “handcuff” to physical cross-link functional polymers (15–18). Introducing shape-persistent nanoparticles into the supramolecular hydrogel system allows for modification of the local gel structures at the colloidal-length scale, resulting in assemblies with unique emergent properties (19). The hierarchical nature of the SPCH is presented, where the hydrogel is composed of nanoscale fibrillar structures. The self-assembled SPCH composite exhibits great elasticity at a remarkably high water content (98%), showing a low-energy manufacturing process for fibers from natural, sustainable precursor materials. We hypothesized that the reorganization of internal structures and the presence of crystallinity in the SPCH enable the formation of the “supramolecular fiber.” Moreover, a detailed investigation of the mechanical behavior of these supramolecular fibers indicates that they exhibit a unique combination of ductility and stiffness. These fibers are also remarkably efficient at absorbing energy with a high damping capacity, comparable with viscose and in some ways, resembling the biological protein-based spider silks.

Fig. 1.

Self-assembly of SPCH. (A) Schematic of the two-step, three-component binding of CB[8] in water. (B) Schematic representation of a hierarchical SPCH prepared through addition of CB[8] to a mixture of polymer-grafted silica P1 (functionalized with MV) and a linear HEC NP H1 in water.

Results

Self-Assembly of SPCH.

The fabrication of SPCH was accomplished by mixing an aqueous solution of H1 (1 wt %) with an aqueous solution of P1 (1 wt %), which was previously complexed with CB[8] in a 1:1 MV:CB[8] ratio (P1 at CB[8]). P1 is a functional polymer (Mn = 74 kDa, polydispersity index Ð=1.48) grafted onto silica NPs with a core size of 50 nm (Fig. 1B; SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S6 show synthesis). The linear polymers (H1 in Fig. 1B) were prepared by functionalizing naphthalene (Np) isocyanate onto hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC; Mn = 1.3 MDa) (20). The composite material exhibited elastic behavior, with an increase in rigidity and a persistent shape. The hydrogel formation is clearly dependent on the presence of all three components of the ternary complex. In the absence of CB[8] or when CB[8] was replaced by cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]), which has a cavity that is only large enough to encapsulate MV alone, mixtures of H1 and P1 behave like a runny liquid (Fig. 2A).

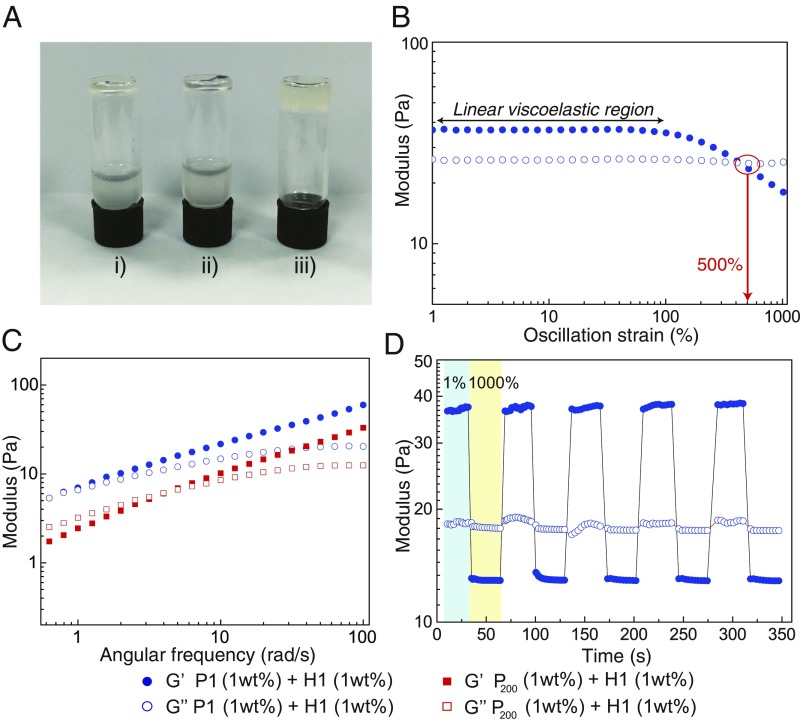

Fig. 2.

Fabrication and rheological characterization of the SPCH. (A) Photograph of inverted vial tests showing the formation of the hydrogel from the mixture of P1 (1 wt %), H1 (1 wt %), and CB[8] (0.05 wt %) exclusively. Vial i, P1 and H1; vial ii, P1, H1, and CB[7]; vial iii, P1, H1, and CB[8]. (B) Rheological strain oscillatory rheology of P1 (1 wt %) at CB[8]/H1 (1 wt %) from 0.1 to 1,000% at 20 °C ( = 10 rad/s). The materials expressed broad viscoelastic regimes and resisted yielding up to 100% strain (/ cross-over point at 500%). (C) Frequency-dependent oscillatory rheology showing that hydrogels with polymer grafted on 50-nm silica nanoparticles (NPs) (P1) have stronger and more ordered networks than hydrogels with polymer grafted on 200-nm silica NPs (P200). (D) Step–strain measurement with applied oscillatory strain alternated between 1 and 1,000% for 30-s periods ( = 10 rad/s, 20 °C). At high strain, G″ dominates. On alternating back to 1% strain, G′ recovers rapidly to its original viscoelastic property. This process was repeated across five high-strain periods, showing good recyclability.

Mechanical properties of the hydrogels were investigated through rheological measurements. Strain-dependent oscillatory rheology of a mixture of H1 (1 wt %) with precomplexed P1 at CB[8] (1 wt %) displays a broad linear viscoelastic region with a gel to sol cross-over point remarkably appearing only at 500% strain (Fig. 2B). The frequency-dependent rheology performed in the linear viscoelastic region is shown in Fig. 2C, blue circles, whereby storage moduli () are dominant over loss moduli () across the whole range of frequencies studied, which identifies gel-like behavior. In the absence of CB[8], no difference in the rheology was observed between an aqueous solution of H1 (1 wt %) alone and a mixture of H1 (1 wt %) with P1 (1 wt %), indicating that entanglement arising from additional polymer chains P1 does not lead to polymeric network formation (SI Appendix, Figs. S7–S9). When P1 was replaced with a larger silica NP size of 200 nm (P200), the assembled hydrogel became weaker (as shown by the red squares in Fig. 2C) as the becomes larger than at low frequencies. This observation is possibly caused by the reduction in the number of effective cross-links in the hydrogel network (21). In addition, a rapid recovery rate of the material is observed in step–strain measurements depicted in Fig. 2D, where alternating strains of 1 and 1,000% were applied to the material at 30-s intervals. Overall, the process was repeated over five cycles, and the SPCH exhibited fast and complete recovery to its initial modulus, corresponding to the fast association kinetics of CB[8] ternary complexation (22, 23).

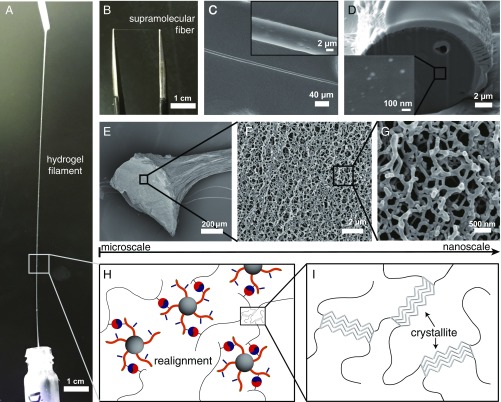

We observed that the hydrogels were substantially “stretchy,” revealing a highly ductile nature. Moreover, a “filament” can be drawn from a reservoir of hydrogel (5 mg) at room temperature that remained stable to lengths 250 mm (Fig. 3A) After the water in the hydrogel filament evaporates within 30 s, a fine and flexible fiber remains with a cylindrical shape and consistent diameter as shown in the SEM images in Fig. 3 B and C. The fiber diameter was found to be independent of the draw length (R2 = 0.001, n = 177) (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), suggesting that an increase in length during drawing was not at the expense of fiber diameter. Rather, fiber length increased through continuous drawing of material from the hydrogel reservoir and a simultaneous, rapid liquid–solid phase transition. We envisage that the fiber diameter is likely determined and therefore, may be tuned by parameters, such as gel viscosity, surface tension, environment (e.g., humidity), and use of nozzles/orifices of specified dimensions. In addition, by slicing the cross-section of the supramolecular fiber using a focused ion beam, we observed that the silica core NPs from P1 were dispersively embedded in the fiber (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Investigating the structure of SPCH. (A) Photograph of the hydrogel filament drawn from the SPCH reservoir. (B) Photograph of the supramolecular fiber after the hydrogel filament undergoes fast dehydration. (C) SEM image of the supramolecular fiber (Inset, zoomed-in view of fiber). (D) Focused ion beam SEM image of the cross-section area in the supramolecular fiber; the light-colored particles in Inset depict the silica NPs with size around 50 nm dispersed inside the polymer matrix. (E–G) Cryogenic SEM images of the internal structure of SPCH shows its hierarchical nature with nanoscale fibrils feature. (H and I) Proposed molecular organization within the hydrogel filament, with H1 and P1 physically cross-linked by CB[8], and the H1 polymer having crystalline domains.

SEM was further used to investigate the internal structure of the SPCH in an effort to explain its unique ductility. Fig. 3 E–G reveals the microstructure in the cross-section of the cryodried and lyophilized hydrogel filament. As the magnification factor increased, we observed nanoscale fibrillar features that interweave and support the internal network of the hydrogel filament. When the diameter of the silica core increased, hydrogels assembled between P200 at CB[8] and H1 exhibited nanosheet-like internal structures (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) compared with the nanofibril features mentioned above, which resulted in unstable filaments (that break on dehydration). This observation also correlates with the frequency sweep in the early rheology study (Fig. 2C, red squares). When P1 was replaced with a linear polymer poly(NIPAm-co-HEAm-MV), the hydrogel did not show such ductility, and it did not yield fibers (Movie S2). No nanofibrillar microstructures were observed in the hydrogels (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) or for any previously reported CB[8]-based hydrogels. More importantly, the semicrystalline H1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S13) allows additional enhancement of the elasticity, where the crystalline domain of the polymer chains could reconfigure itself. To verify this hypothesis as a generic theory, we prepared a hydrogel by replacing H1 with Np functionalized polyvinyl alcohol that is a typical semicrystalline polymer. The resulting materials show similar transformations into fibers (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). In contrast, when amorphous functional polymers [poly(AM-co-HEAm-Np)] were assembled with P1 at CB[8], no fiber formation was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Overall, H1, with crystalline domains at the molecular level, was assembled with P1 through dynamic host–guest interactions via CB[8], forming the nanoscale fibrils, which extend, realign, and repack at the colloidal-length scale (Fig. 3 H and I). The resulting “hydrogel filament” (drawn from the SPCH) exhibits hierarchical structures across multiple length scales that distribute the applied stress effectively. Finally, the large aspect ratio of the filament induces fast evaporation of water, yielding a ductile supramolecular fiber.

Characterization of the Supramolecular Fiber.

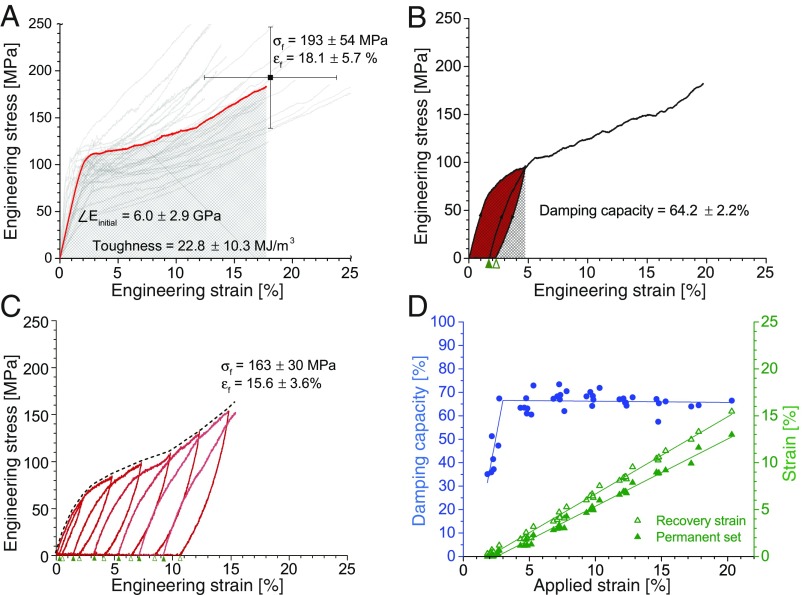

Stress–strain profiles (Fig. 4A) display an initial linear region up to a yield point in the range of 1–3% applied strain. (The tensile-testing method of fibers is described in SI Appendix.) The elastic modulus determined in this region was 6.0 2.9 GPa. Most polymeric materials have stiffness in the range of 1 MPa to 10 GPa. Our supramolecular fiber consists of multiple phases, some of which are soft (amorphous) at room temperature and some of which are crystalline. The crystalline phases provide intermolecular interactions that are stable and do not exhibit viscosity at room temperature, thereby dominating the mechanical response and the resulting high stiffness. Failure strength and strain of the fiber were determined to be 193 54 MPa and 18.1 5.7%, respectively. This unique combination of tensile properties exceeds that of conventional regenerated textile fibers, such as cellulose-based viscose, and protein-based artificial silks as well as animal and human hair (24) (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). Finally, the toughness or total energy required to break the fiber was calculated to be 22.8 10.3 MJm−3, higher than several natural fibers, such as flax and jute (25). The coefficient of variation in properties ranged between 30 to 50%, which is a spread commonly observed in natural fibers, including biological silk (26) and flax (27). Factors influencing variability include processing conditions (drawing speed) and environmental conditions (during processing and testing) as well as the composition of the material (26, 28).

Fig. 4.

Mechanical properties of supramolecular fibers subjected to static and cyclic tensile loads. (A) Illustration of the fiber stress–strain response at a quasistatic loading rate: gray curves indicate variability in the dataset (n = 50), with a representative data curve shown in red; the data point (black square) indicates the mean failure strength and strain, with error bars denoting one SD. (B) Representative stress–strain curve (n = 7) of a fiber subjected to a single loading–unloading–reloading cycle (indicated by arrowheads) at 5% strain. The recovery strain (on unloading) and the permanent set (before reloading) are indicated by white and gray triangles, respectively, on the x axis. The damping capacity was determined from the ratio of the damping energy (shaded area; area between the loading and unloading curves) to the stored energy (hatched area; area below the loading curve). (C) Representative stress–strain curve (n = 7) of a fiber subjected to progressive loading cycles at 2.5% strain intervals up to failure. The damping energy, indicated by the areas between the paired loading–unloading curves, increases with every loading cycle. (D) The evolution of damping capacity, recovery strain, and permanent set with applied strain. Linear fits to the data points are shown.

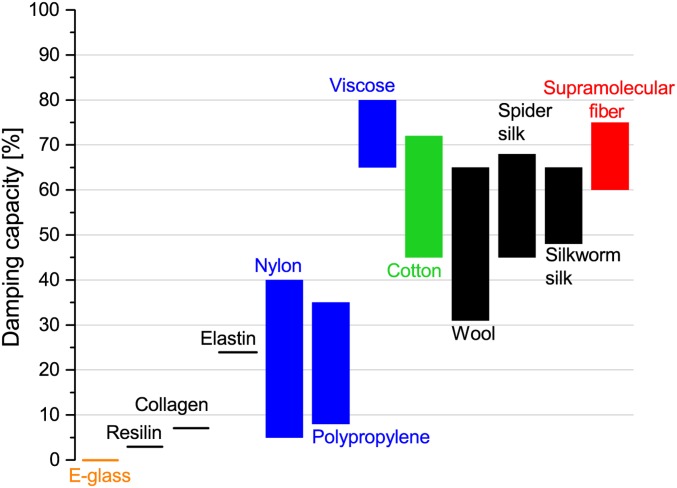

In an effort to assess reversibility and damping behavior of the supramolecular fiber, material response to cyclic loads was investigated. Fibers with low damping capacity (high resilience), like E-glass, elastin, polypropylene, and vulcanized rubber, are efficient at recovering most of the deformation energy that they absorb, typically exhibiting little to no hysteresis, whereas fibers with high damping capacity (low resilience), such as viscose, cotton, and silks, are efficient at absorbing or dissipating most of the energy (Fig. 5). We subjected the fiber to a single load–unload–reload cycle (Fig. 4B). It is evident that the supramolecular fiber has a high damping capacity of 64.2 2.2% (n 7), which is even higher than biological silks and comparable with viscose (Fig. 5). Furthermore, we find that the coefficient of variation in the damping capacity of our supramolecular fiber was significantly lower at only 3% compared with that of all other mechanical properties (ranging between 30 and 50%). Thus, damping capacity in our case is more directly related to the molecular structure of the fiber.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the mechanical properties of our supramolecular fiber (red) with other typical technical fibers. The damping capacity of the supramolecular fiber exceeds that of biological silks and is comparable with viscose, making it a good candidate for energy absorption applications.

From additional tests, we observed that damping energy as well as damping capacity reduced with respected cycles of loading–unloading: from 67.2 5.3% in the first cycle to 31.2 2.8% by the fifth cycle, with the major drop (of 60%) occurring between the first and the second cycles (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Essentially, by subjecting the supramolecular fiber to multiple cycles at the same applied strain, it was transformed from being effective at energy dissipation to a material efficient at energy recovery and storage. Interestingly, this behavior has also been observed for spider silks, with damping capacity that drops from around 68% in the first cycle to as low as 37% in subsequent cycles (29). When the supramolecular fiber was subjected to progressive loading–unloading cycles until failure, the damping energy was observed to increase with every cycle (Fig. 4C). Notably, although the damping capacity increased from 30 to 65% in the range of 2–3% applied strain (i.e., after the first cycle, close to the yield point), it was remarkably stable at 66% for all other cycles of applied strain ranging between 3 and 20% (n = 7) (Fig. 4D). The existence of damping capacity below the yield strain is likely to be because the supramolecular fibers are “visco-elastic” (rather than “purely elastic”) below the yield point and “visco-elasto-plastic” above the yield point. Again, such a profile has also been observed for spider silks, which have damping capacity that is low (at 5–30%) in the first cycle at 5% applied strain but increases to 30–70% in subsequent cycles of increasingly applied strain (30). The recovery strain and permanent set (permanent deformation) were also found to increase linearly with the applied strain (applied deformation) in every cycle up to failure (Fig. 4D).

We envision that the remarkable damping performance of the supramolecular fiber arises from energy dissipative mechanisms provided by a complex structure of “hard” (crystalline) and “soft” (amorphous) phases at the molecular scale (vis. semicrystalline H1 polymer) (Fig. 3I), like in spider silks (29, 31). Although the soft phase is always active, the hard phase is strain-activated and undergoes a partly reversible transformation to the soft phase via a process of strain-induced hydrogen bond breakage when stretched to its limit, which is accompanied by the unraveling, aligning, and slipping of molecular chains. The energy stored during loading in the previous process is (partly) released during unloading by the reformation of hydrogen bonds and reverse transition of soft phases to hard phases as well as dealignment or coiling of molecular chains. Consequently, the fiber finds itself in a new molecular conformation at a nonzero recovery strain (Fig. 4B) (29, 31). In the case of our supramolecular fiber, hard and soft phases exist beyond the molecular scale of the semicrystalline H1 polymer and at the intermolecular scale (where CB[8] provides dynamic cross-links between P1 and H1) as well as at the colloidal scale (silica NPs in the SPCH) (Fig. 3H).

Conclusion

We have shown a means of assembling hierarchical SPCHs based on CB[8] host–guest chemistry. By introducing functional polymer-grafted silica NPs, we successfully modified the internal structure of the gel at the nanoscale and benefited from the semicrystalline nature of H1, which allow for significant enhancement of the elasticity of the material. We have reported a supramolecular fiber drawn from an extremely high-water content SPCH at room temperature. The synthetic biocompatible fiber exhibits a unique combination of strength and high damping capacity that can be readily manipulated through a detailed understanding of the hierarchical assembled structure and the underlying CB[8] host–guest chemistry. We envision that, by altering the chemistry and processing methods of SPCH, a family of supramolecular fibers with a whole range of tunable properties can be produced at low temperature, taking us a considerable step closer to sustainable fiber technology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Skepper and Dr. J. J. Rickard for their detailed and helpful discussion on this manuscript. This work was supported by Engineering Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Grant EP/K503496/1 and Translational Grant EP/H046593/1 as well as a Leverhulme Trust Program Grant (Natural Materials Innovation). Y.W. was funded by EPSRC Grant EP/L504920/1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 8138.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1705380114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rising A, Johansson J. Toward spinning artificial spider silk. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vollrath F, Knight DP. Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk. Nature. 2001;410:541–548. doi: 10.1038/35069000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greiner A, Wendorff JH. Electrospinning: A fascinating method for the preparation of ultrathin fibers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:5670–5703. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitesides GM, Mathias JP, Seto CT. Molecular self-assembly and nanochemistry: A chemical strategy for the synthesis of nanostructures. Science. 1991;254:1312–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1962191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webber MJ, Appel EA, Meijer EW, Langer R. Supramolecular biomaterials. Nat Mater. 2016;15:13–26. doi: 10.1038/nmat4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aida T, Meijer EW, Stupp SI. Functional supramolecular polymers. Science. 2012;335:813–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1205962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capito RM, Azevedo HS, Velichko YS, Mata A, Stupp SI. Self-assembly of large and small molecules into hierarchically ordered sacs and membranes. Science. 2008;319:1812–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.1154586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson R, et al. Structure of the cross- spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S, et al. A self-assembly pathway to aligned monodomain gels. Nat Mater. 2010;9:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nmat2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dankers PYW, et al. A modular and supramolecular approach to bioactive scaffolds for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2005;4:568–574. doi: 10.1038/nmat1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merzlyak A, Indrakanti S, Lee SW. Genetically engineered nanofiberlike viruses for tissue regenerating materials. Nano Lett. 2009;9:846–852. doi: 10.1021/nl8036728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reches M, Gazit E. Casting metal nanowires within discrete self-assembled peptide nanotubes. Science. 2003;300:625–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1082387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato T, Mizoshita N, Kishimoto K. Functional liquid-crystalline assemblies: Self-organized soft materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;45:38–68. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appel EA, et al. Ultrahigh-water-content supramolecular hydrogels exhibiting multistimuli responsiveness. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11767–11773. doi: 10.1021/ja3044568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, et al. Cucurbit[n]uril-based microcapsules self-assembled within microfluidic droplets: A versatile approach for supramolecular architectures and materials. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:208–217. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, et al. Biomimetic supramolecular polymer networks exhibiting both toughness and self-recovery. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1604951. doi: 10.1002/adma.201604951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, et al. Tough supramolecular polymer networks with extreme stretchability and fast room-temperature selfhealing. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1605325. doi: 10.1002/adma.201605325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose S, et al. Nanoparticle solutions as adhesives for gels and biological tissues. Nature. 2014;505:382–385. doi: 10.1038/nature12806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appel EA, Loh XJ, Jones ST, Dreiss CA, Scherman OA. Sustained release of proteins from high water content supramolecular polymer hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4646–4652. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan Y, Loh XJ, Geng J, Walsh Z, Scherman OA. A supramolecular route towards core-shell polymeric microspheres in water via cucurbit[8]uril complexation. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48:8757–8759. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34016j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowland MJ, Appel EA, Coulston RJ, Scherman OA. Dynamically crosslinked materials via recognition of amino acids by cucurbit[8]uril. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med. 2013;1:2904–2910. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20180e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland MJ, Atgie M, Hoogland D, Scherman OA. Preparation and supramolecular recognition of multivalent peptide-polysaccharide conjugates by cucurbit[8]uril in hydrogel formation. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:2436–2443. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewin M. Handbook of Fiber Chemistry. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah D, Porter D, Vollrath F. Can silk become an effective reinforcing fibre? a property comparison with flax and glass reinforced composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2014;101:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colomban P, Dinh HM, Bunsell A, Mauchamp B. Origin of the variability of the mechanical properties of silk fibres: 1-the relationship between disorder, hydration and stress/strain behaviour. J Raman Spectrosc. 2012;43:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aslan M, Chinga-Carrasco G, Sørensen BF, Madsen B. Strength variability of single flax fibres. J Mater Sci. 2011;46:6344–6354. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vollrath F, Porter D, Holland C. The science of silks. MRS Bull. 2013;38:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shao Z, Vollrath F. The effect of solvents on the contraction and mechanical properties of spider silk. Polymer (Guildf) 1999;40:1799–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly SP, Sensenig A, Lorentz KA, Blackledge TA. Damping capacity is evolutionarily conserved in the radial silk of orb-weaving spiders. Zoology (Jena) 2011;114:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Tommasi D, Puglisi G, Saccomandi G. Damage, self-healing, and hysteresis in spider silks. Biophys J. 2010;98:1941–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.