Significance

A stripe pattern is widely observed among animals and often used for warning or camouflage in caterpillars. However, its genetic background is largely unknown. This study showed that the Toll ligand Spätzle3 (Spz-3) is responsible for the silkworm Zebra locus, which causes black stripes on the anterior margin of each segment. Exhaustive knockdown experiments of spz- and Toll-related genes clarified that spz-3 and Toll-8 are involved in the melanin pigmentation of Zebra and another mutant. The Spz-3/Toll-8 signaling pathway is suggested to induce Zebra stripe-specific expression of the pigmentation gene yellow. This study sheds light on not only the unique aspect of Spz/Toll functions but also, stripe pattern pigmentation in caterpillars through co-option of a Toll signaling pathway.

Keywords: Spätzle3, Toll signaling pathway, melanization, striped pattern, Bombyx mori

Abstract

A stripe pattern is an aposematic or camouflage coloration often observed among various caterpillars. However, how this ecologically important pattern is formed is largely unknown. The silkworm dominant mutant Zebra (Ze) has a black stripe in the anterior margin of each dorsal segment. Here, fine linkage mapping of 3,135 larvae revealed a 63-kbp region responsible for the Ze locus, which contained three candidate genes, including the Toll ligand gene spätzle3 (spz-3). Both electroporation-mediated ectopic expression and RNAi analyses showed that, among candidate genes, only processed spz-3 induced melanin pigmentation and that Toll-8 was the candidate receptor gene of spz-3. This Toll ligand/receptor set is also involved in melanization of other mutant Striped (pS), which has broader stripes. Additional knockdown of 5 other spz family and 10 Toll-related genes caused no drastic change in the pigmentation of either mutant, suggesting that only spz-3/Toll-8 is mainly involved in the melanization process rather than pattern formation. The downstream pigmentation gene yellow was specifically up-regulated in the striped region of the Ze mutant, but spz-3 showed no such region-specific expression. Toll signaling pathways are known to be involved in innate immunity, dorsoventral axis formation, and neurotrophic functions. This study provides direct evidence that a Toll signaling pathway is co-opted to control the melanization process and adaptive striped pattern formation in caterpillars.

Animals have various color patterns: spot and stripe patterns are frequently observed. These body patterns are often used for camouflage or aposematic coloration to avoid predators (1, 2). In aposematism, the contrast created by the combination of bright and dark colors, such as yellow/red and black (Fig. 1A), is important to facilitate detection by predators and hasten avoidance learning (3). The molecular mechanism underlying spot formation in adult and larval insects has become more apparent via many studies in Drosophila (4, 5), Bombyx mori (6, 7), and several butterflies (8–10). Although stripe pattern formation is well-studied in vertebrates, such as the zebra (11), rodents (12), and zebrafish (13), the molecular backgrounds of this pattern in insects are largely unknown. Because the stripe pattern is often observed in lepidopteran larva and its biological roles are more evident than in other animals (14, 15), it is intriguing to study the mechanism and evolutionary origin of caterpillar stripe formation.

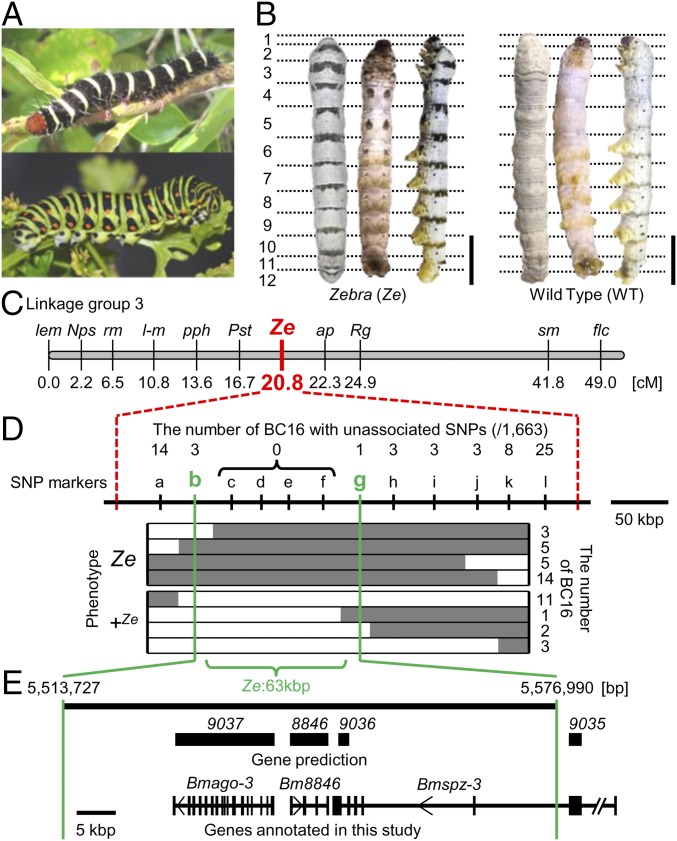

Fig. 1.

Striped pigmentation in lepidopteran larvae and fine mapping of the B. mori mutant Ze. (A) Lepidoptera larvae in nature have striped color patterns that function in aposematic coloration. (Upper) The frangipani hornworm (Pseudosphinx tetrio). (Lower) The common yellow swallowtail (Papilio machaon). (B) Dorsal, ventral, and lateral views of the f40 strain, the Ze mutant (Left) and the WT N4 strain (Right) of B. mori. Ze has a black stripe on one-fourth of the anterior part of the dorsal side of each larval segment in contrast to N4 without markings. (Scale bars: 1 cm.) (C) Genetic maps of B. mori linkage group 3. (D and E) The fine mapping results of the Ze region. Regions separated by broken red lines indicate the responsible 400 kbp by standard SNP markers (25). Gray and white bars indicate the genotypes of the heterozygote (Ze/+Ze) and homozygote (+Ze/+Ze), respectively. The 63-kbp region responsible for the Ze phenotype is denoted by Ze:63kbp. The numbers above the SNP markers indicate recombination events. Gene prediction in the Ze:63kbp was derived from KAIKObase and SilkBase databases.

The silkworm B. mori is a suitable model organism to study the genetic and molecular mechanisms of color pattern formation. There are extensive stocks of larval marking mutants, whole-genome information, and readily available functional analysis tools (16, 17). The silkworm mutant Zebra (Ze), which occurred spontaneously in ancient China, has a black stripe on one-fourth of the anterior part of the dorsal side of each larval segment (Fig. 1B, Left) and provides a good object to study to understand the mechanism of striped pattern formation. Previous genetic studies revealed that the Ze allele is dominant over the WT and mapped to 20.8 cM of linkage group 3 (18) (Fig. 1C).

In this study, a 63-kbp region responsible for Ze, including three predicted genes, was identified by linkage analysis. Additional observation of expression profiles and functional analysis of these three genes showed that the Ze allele is caused by a spätzle (spz) family gene Bmspätzle3 (Bmspz-3). A cytokine-like ligand for the Toll receptor, Spz, is a key molecule in the activation of the Toll signaling pathway, which is involved in both dorsoventral axis formation during embryogenesis (19) and innate immunity (20). In addition, among spz paralogous genes in Drosophila melanogaster, some have been suggested to be involved in innate immunity and neurotrophic functions (20). However, to date, no evidence has been provided to show that this spz family gene regulates the melanin synthesis pathway directly. Therefore, the findings in this study shed light on not only the unique function of this spz family gene but also, the molecular mechanism of color pattern formation, which furthers our understanding of the whole melanin synthesis pathway involved in body marking and innate immunity.

Results

Fine Linkage Mapping of the Ze Locus in B. mori.

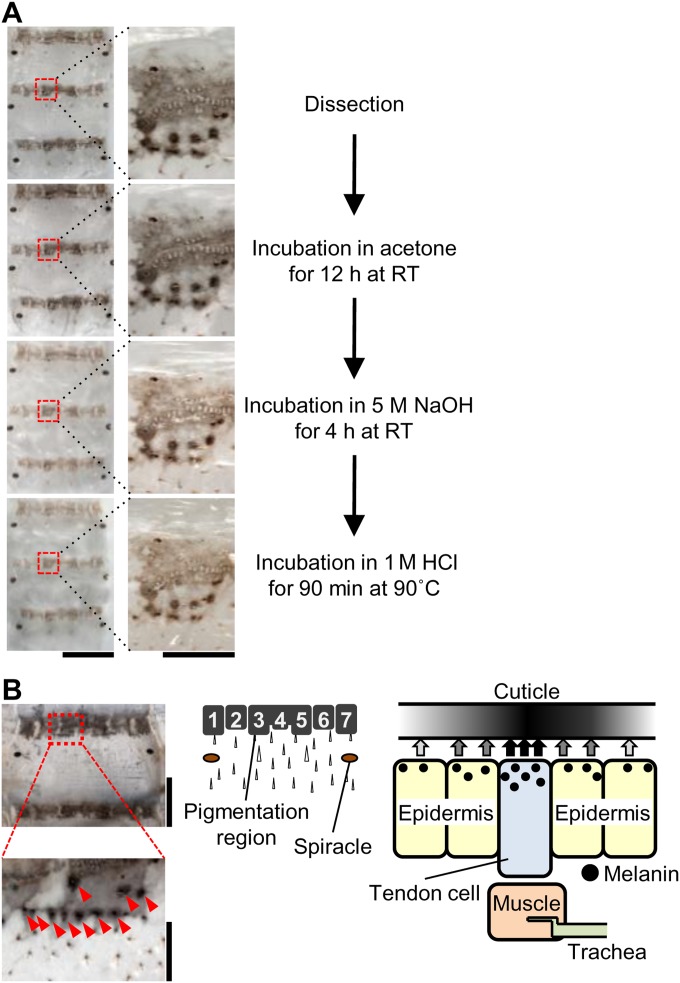

Each larval segment of the Ze mutant strain f40 [Ze/Ze; plain (p)/p] has a black striped marking in the anterior margin on the dorsal side and a twin spot marking on the ventral side (Fig. 1B, Left), in contrast to the WT strain N4 (+Ze/+Ze; p/p) without markings (Fig. 1B, Right). Chemical analysis suggested that the pigments accumulated in the black stripes on the cuticle of the Ze mutant contained melanin (Fig. S1A). Detailed observation revealed that each stripe is composed of seven blocks of pigmented areas (Fig. S1B, Center). In the dense spots (Fig. S1B, red arrowheads), the melanin pigments accumulated on the cuticle just around the joint region between the tendon cell and muscle (Fig. S1B, Right).

Fig. S1.

Insolubility of the cuticle pigmentation of the Ze mutant. (A) The dissected cuticles from fourth larval instar (row 1) were sequentially treated with acetone for 12 h at room temperature (row 2), 5 M NaOH for 4 h at room temperature (row 3), and 1 M HCl for 90 min at 90 °C (row 4). Enlargements of the areas in red rectangles in Left are shown in Right. (Scale bars: Left, 5 mm; Right, 0.5 mm.) (B) Pigmented cuticle in Ze. The pigmented area is composed of seven subareas, and the dense melanin pigments are on the tendon‒muscle junction (red arrowheads and presumed scheme of pigmentation). (Scale bars: Upper Left, 2 mm; Lower Left, 500 μm.)

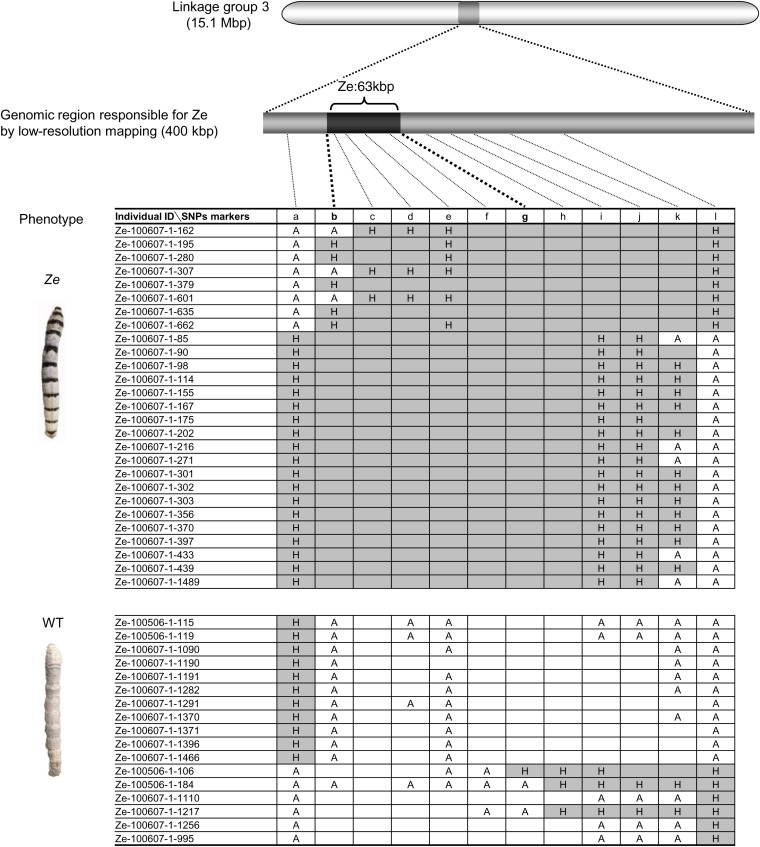

Previous genetic studies have mapped the Ze locus to linkage group 3 (18) (20.8 cM) (Fig. 1C). Using standard SNP markers (21), low-resolution mapping was first performed with 1,472 progeny [733 Ze individuals (Ze/+Ze; p/p) and 739 p individuals (+Ze/+Ze; p/p)] obtained from 10 pairs of parents [backcrossed F1 progeny (BC1) males and p females]. Using newly designed SNP markers (Table S1), we further performed fine mapping of 1,663 progeny (822 Ze individuals and 841 p individuals) obtained from 11 pairs of parents (BC16 males and p females). Among 12 additional genetic markers (a‒l), the genotypes of four markers (c‒f) were completely linked to the Ze phenotype (Fig. 1D and Fig. S2). These analyses showed that the Ze locus was located within an ∼63-kbp region, hereafter referred to as Ze:63kbp.

Table S1.

Primers for fine mapping

| ID | Name | Sequence | Name | Sequence |

| a | Ze-071119-R16_F1 | TTAAGGGTGGTTTGAAGAGG | Ze-071119-R16_R1 | TTATGCGTAGGCTTACTGGC |

| b | Ze400K_14_F | TCTCATCCACATCATCGTTGGTC | Ze400K_14_R | GCAGGCTTCGAACGGAACTAATGT |

| c | Ze400K_57_F | GGTAAAGCGGTGACGTCATGAAA | Ze400K_72_R | GGGTGAAATTAGTACTTCACTATCAG |

| d | Ze400K_13_F | TTCTGAAACTAGGAGTCTAGTAGAGT | Ze400K_13_R | AAGATCGACCGTGAAGATCTCC |

| e | 8846-F2 | TGCTACGAACGCCACTACGCT | 8846-R6 | TGGACTGCAGTGTGCAGCTCCA |

| f | Ze400K_35_F | CTCATTTGAGACTAGTCTTATACATAGT | Ze400K_35_R | ATTAATACTCTCCGTGACAACAGAAC |

| g | Ze400K_39_F | ACCGGCTGAGACGTCAGTTAGT | Ze400K_39_R | AACCGAGAACTAGCTTAGCGTTAAG |

| h | Ze400K_34_F | AAACAATGGCCGTAAAGCTGTCGGT | Ze400K_34_R | TACGCAACAACGCAACAACCTGAAAC |

| i | Ze400K_21_F | GTTTGTGGGTGACCCATATTAGG | Ze400K_21_R | CCGAAAACGGTTACCAATTAGTCT |

| j | Ze400K_10_F | CCTTTGTGAGGAAGTGTACTTGAG | Ze400K_10_R | GTTGTGTCAAAATTGTGGTGTCGCA |

| k | Ze400K_08_F | GATGATGTCACCCATTGCCATTTAC | Ze400K_08_R | CCACACACCTACAACTCTATCATATG |

| l | ap-9038-F | GTTTGCAAGTACTGCCAACG | ap-9038-R | GAAAGTGTGACAATCCTTGTGTC |

Fig. S2.

Detail of linkage analysis. The phenotypes of BC16 individuals were completely linked to the genotype at markers c–f, suggesting that the genomic region responsible for Ze is narrowed down to ∼63 kbp (between markers b–g). A and H indicate a WT homozygote and a heterozygote, respectively. Blanks with white and gray columns indicate the presumed genotypes of A and H, respectively, according to the results of neighboring SNP markers.

Ze:63kbp Includes Three Candidate Genes for the Ze Locus.

The Ze:63kbp region includes three predicted genes (BGIBMGA008846, BGIBMGA009036, and BGIBMGA009037) according to KAIKOBase (sgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/KAIKObase/) and SilkBase (silkbase.ab.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/cgi-bin/index.cgi) databases (Fig. 1E). BGIBMGA009037 encodes an argonaute3 (accession no. AB332312) homolog, which was named Bmago-3. The amino acid sequence of BGIBMGA009036 contained an spz-like cystine knot domain. Furthermore, a BLASTp search and phylogenetic analysis indicated that this is a homolog of spz-3 in other insects [e.g., D. melanogaster (NP_609160.2) and Tribolium castaneum (NP_001153625.1)] (Fig. S3A). BGIBMGA009035, which is located outside of Ze:63kbp, was found to be a part of the spz-3 gene, and thus, the combined sequences of 9035 and 9036 were characterized as Bmspz-3 (Fig. 1E). BGIBMGA008846 encodes an NifU-like domain, which has been suggested to be involved in the assembly of iron‒sulfur clusters and binds one iron ion at its N terminus (22). However, the homolog and function of this gene are not clear, and thus, we henceforth refer to as Bm8846.

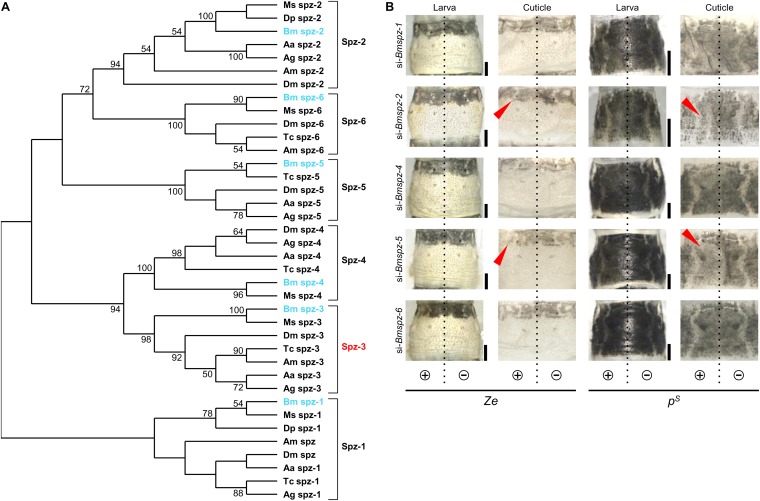

Fig. S3.

Phylogenetic analysis and knockdown of spz family genes other than spz-3 in the Ze and pS strains. (A) The phylogenetic tree was inferred based on the amino acid sequences of the CK domain from public databases using the maximum likelihood method (LG + G + I model). Bootstrap values >50% are provided in the branches. (B) Phenotypes of knockdown of other spz family genes in Ze and pS strains. Dashed lines illustrate the position of the dorsal midline. (Scale bars: 1 mm.)

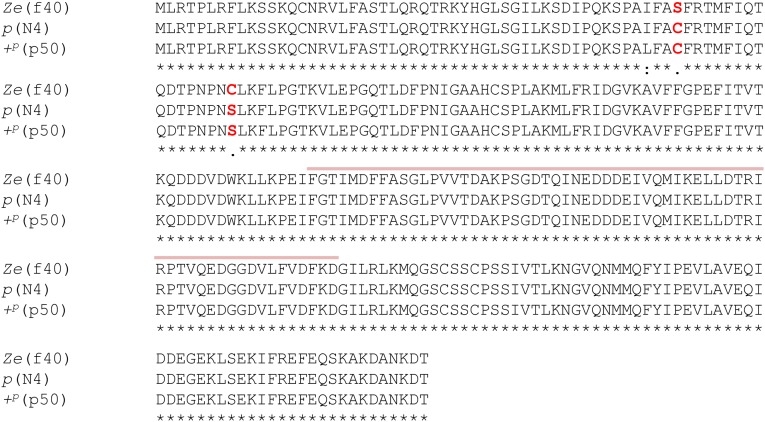

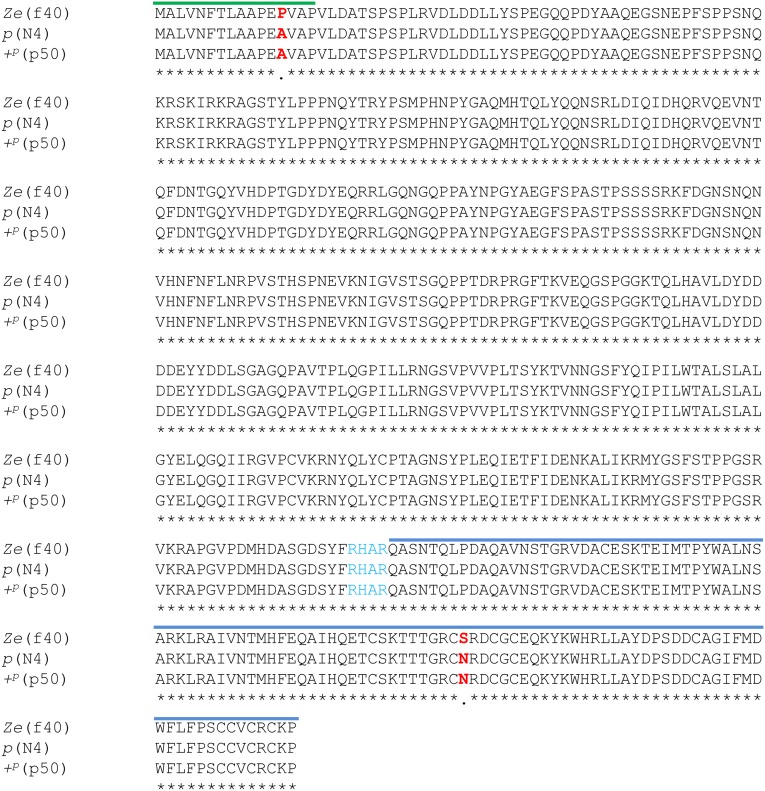

To determine whether the Ze candidate genes had structural defects in an ORF, the amino acid sequences of the three predicted genes in Ze:63kbp from three strains [Ze (f40), p (WT; N4), and +p (WT; p50)] were compared. Among the Ze and the two WT strains, there were no frameshifts and/or indels for all three genes (Figs. S4–S6). Bmspz-3 had two nonsynonymous substitutions within a signal peptide (P in the Ze, A in the two WT strains) and cystine knot domain regions (S in the Ze, N in the two WT strains) (Fig. 3A; Fig. S5). The region encoding the signal peptide for Bmspz-3, however, was located outside of Ze:63kbp; thus, the amino acid change in this region should not be involved in the phenotypic change. In contrast, no nonsynonymous substitutions were observed within the functional domains of Bm8846 and Bmago-3 (Figs. S4 and S6, respectively).

Fig. S4.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Bm8846 between the Ze and two WT strains. The amino acid sequences of Bm8846 were compared between the Ze (f40) and WT strains. The red characters and dots under the sequences indicate nonsynonymous substitutions between the Ze and WT strains. There were two nonsynonymous substitutions on the outside of the NifU-like domain, which are indicated by pink lines. The asterisks and colon indicate identical amino acids and nonsynonymous substitutions of the WT strains, respectively.

Fig. S6.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Bmago-3 between the Ze and two WT strains. The amino acid sequences of Bmago-3 were compared between the Ze (f40) and WT strains. The red characters and dot under the sequences indicate nonsynonymous substitutions between the Ze and WT strains. There was one nonsynonymous substitution on the outside of the PAZ domain that is indicated by a green line, and there was one nonsynonymous substitution on the outside of the Piwi domain that is indicated by an orange line. The asterisks and colon indicate identical amino acids and nonsynonymous substitutions of the WT strains, respectively.

Fig. 3.

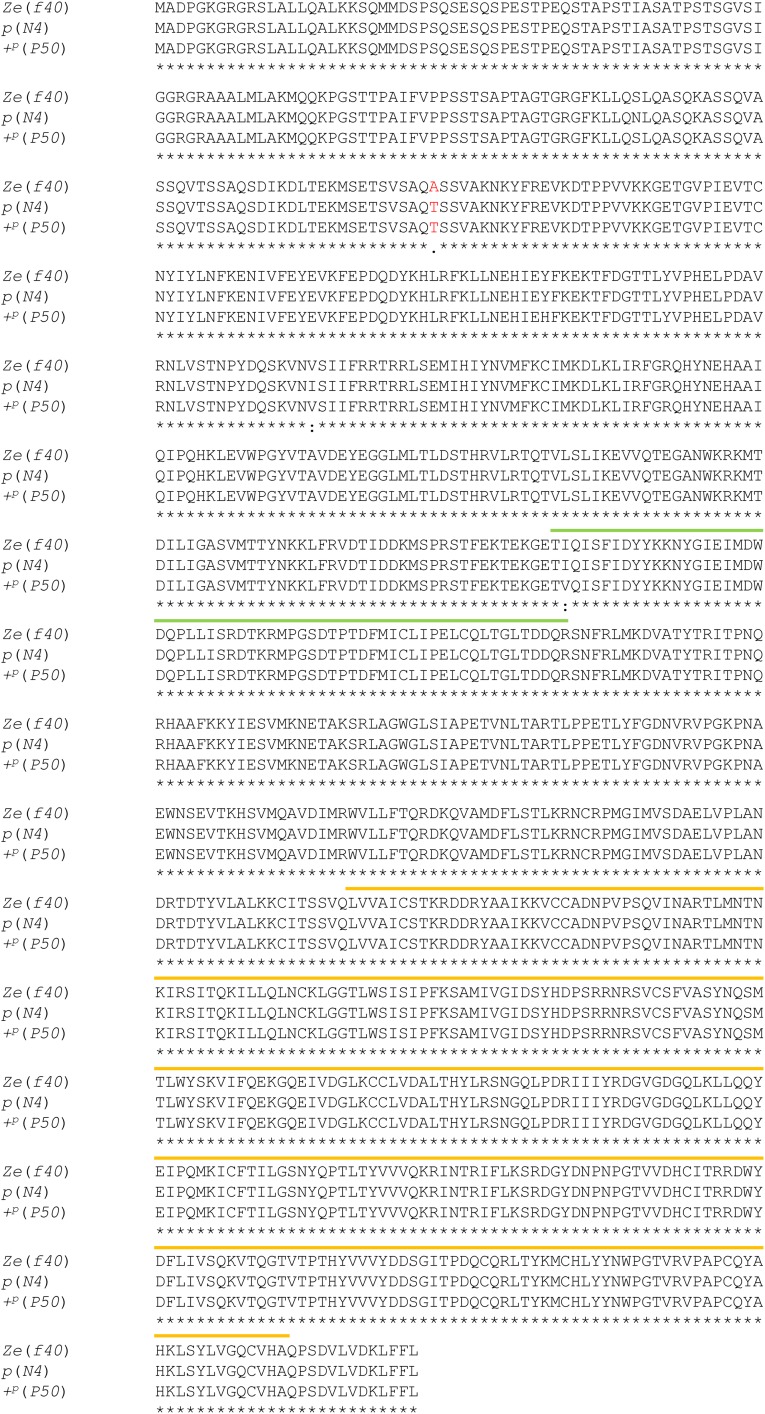

Ectopic expression of transgene Bmspz-3 causes melanin pigmentation of the larval and pupal cuticle. (A) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Spz-3 of the Ze and WT strains. Green letters indicate nonsynonymous substitutions, and red letters C indicate highly conserved cysteine motifs among the spz family genes. (B) Scheme of plasmids for transgenic ectopic expression of Bmspz-3 and the helper plasmid pHA3PIG, which encodes piggyBac transposase. All plasmids contained the A3 promoter of Bmactin3, EGFP as a reporter, and recognition sequences of piggyBac (L and R with gray arrows). We prepared plasmids, which encoded the full-length ORF of Bmspz-3 (Spz-3WTFL and Spz-3ZeFL for WT and Ze, respectively), and the CK domain region, where the processed form functioned with the signal peptide (26) (Spz-3WTCKSP and Spz-3ZeCKSP) of both of the Ze and WT strains, respectively, to test whether melanin pigmentation was caused by Bmspz-3. The blue and red arrowheads in A and B indicate processing sites for the signal peptide and the processed form of Bmspz-3, respectively. The green asterisks indicate the sites of nonsynonymous substitutions as in A. (C and D) The phenotypes of ectopic expression of the full-length (C) and processed (D) forms of Bmspz-3 in larvae and pupa are shown, respectively. (Scale bars: 5 mm.)

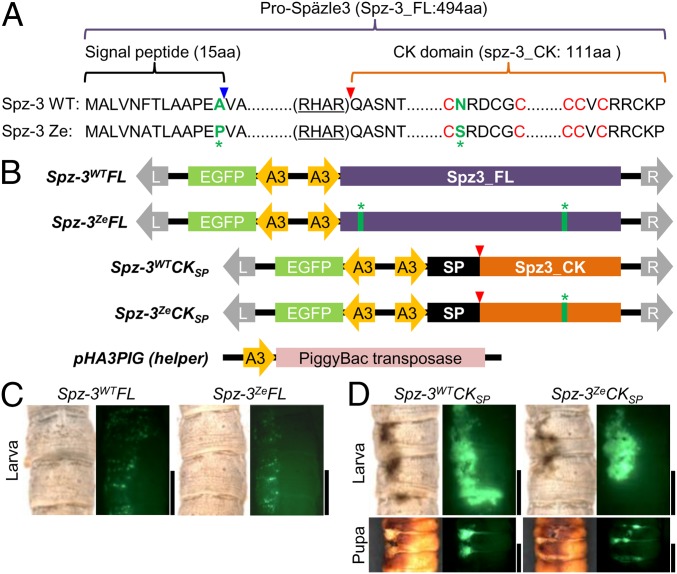

Fig. S5.

Alignment of the amino acid sequence of Bmspz-3 between the Ze and two WT strains. The amino acid sequences of Bmspz-3 were compared between the Ze (f40) and WT strains. The red characters and dots under the sequences indicate nonsynonymous substitutions between the Ze and WT strains, and the blue characters indicate the recognition sequence of the processed RHAR. There were two nonsynonymous substitutions: one in the peptide signal region that is indicated by a green line and another in the cystine knot domain that is indicated by a blue line. Asterisks indicate identical amino acids.

Expression Profiles of Candidate Genes in Larval Epidermis.

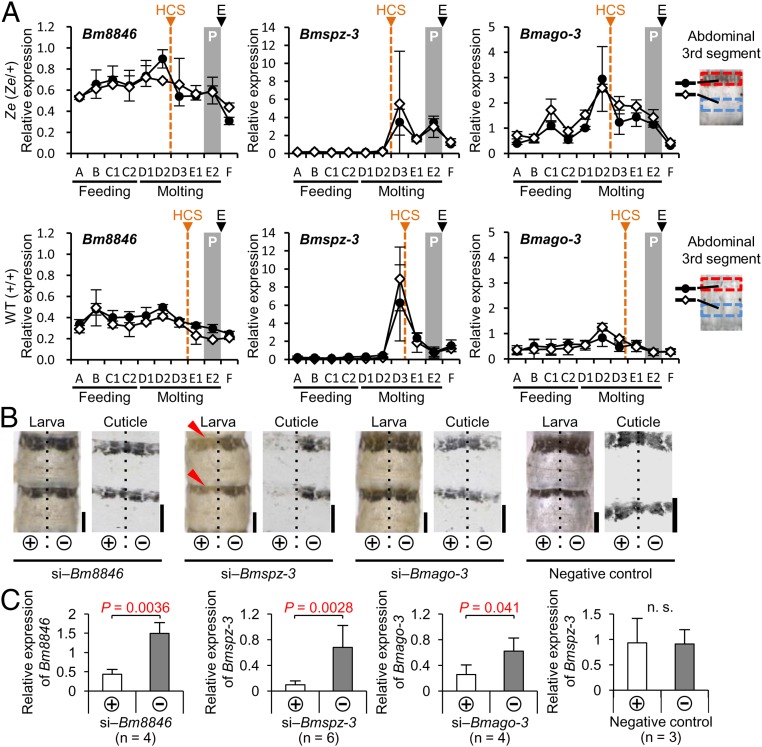

Next, the expression profiles of the above candidate genes within Ze:63kbp in the epidermis were analyzed during the fourth instar stage. We prepared mRNA from pigmented and nonpigmented areas of the abdominal third segment in the Ze (f40; Ze/+Ze) strain and their corresponding areas in the WT (N4; +Ze/+Ze) strain. By quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), the expression levels of the three genes, which were standardized by the expression of the ribosomal protein gene ribosomal protein L3 (BmrpL3), were compared. In all candidate genes, the expression profiles during the fourth instar stage were almost identical between the pigmented (black circle in Fig. 2A) and nonpigmented (white diamond in Fig. 2A) areas in the Ze epidermis (Fig. 2A, Upper: Bm8846, Bmspz-3, and Bmago-3). This result suggests the possibility that the Ze candidate gene itself does not determine the region specificity of pigmentation. Similar expression patterns of the three genes were also observed in the corresponding area of the WT strain (Fig. 2A, Lower: Bm8846, Bmspz-3, and Bmago-3). The expression levels of Bm8846 and Bmago-3 in the Ze strain were higher than those in the WT strain throughout the fourth instar. However, Bmspz-3 expression was lower and peaked at D3 and E2 during the molting period in the Ze strain but only at D3 in the WT strain (Fig. 2A, Center), indicating some differences in expressional control of the gene between the Ze and WT strains. The peak expression during the molting stage suggests that the molting hormone ecdysteroid induces Bmspz-3 expression.

Fig. 2.

Expression profiles and effects of siRNA of Bm8846, Bmspz-3, and Bmago-3 in the larval epidermis. (A) Temporal expression patterns of three genes in the epidermis from the third to fourth ecdysis (n = 3 in each period and strain) are shown for the Ze mutant (Left: Bm8846, Center: Bmspz-3, Right: Bmago-3 in Upper) and the WT strain (Left: Bm8846, Center: Bmspz-3, Right: Bmago-3 in Lower). Expression of the BmrpL3 gene was used as an internal control. The black circles and white diamonds indicate the pigmented and nonpigmented areas of the Ze mutant (or the corresponding areas of the WT strain), respectively, which are shown as red and blue boxes in the abdominal third segment, respectively. E, ecdysis; HCS, head capsule slippage; P, pigmentation period. (B) Phenotypic changes by knockdown of the candidate genes in the larva and cuticle specimen on the abdominal third and fourth segments in the Ze mutant are shown. Dashed lines illustrate the position of the dorsal midline. (Scale bars: 2 mm.) (C) Relative expression levels of genes targeted by siRNA were compared between the introduced (+) and nonintroduced (‒) sides. Statistical comparisons were conducted using the one-sided paired Student’s t test. Error bars indicate the SD.

Bmspz-3 Knockdown Causes Stripe Pigmentation Loss.

To identify the candidate gene responsible for the black stripe pigmentation in Ze, an in vivo electroporation technique (23, 24) was used to knockdown each candidate. Then, the resulting phenotypic changes were observed. Although RNAi is not generally effective in Lepidoptera, this technique enables the introduction of dsRNA or plasmid DNA into the target tissues, such as the epidermis, both easily and effectively. After siRNA for each gene was introduced into the epidermis of the abdominal third and fourth segments of the third instar larvae, the phenotypic change was observed in the fifth instar stage (Fig. 2B). In this method, RNAi-induced changes should occur in the left side of the segment where the plus electrode (+) was touched, because the negatively charged RNA was introduced effectively into the epidermal cells.

Bm8846 and Bmago-3 siRNA had no effect on the larval phenotypes in the Ze strains (Fig. 2B). However, when the larvae were treated with siRNA of Bmspz-3 (si‒Bmspz-3), the black stripes disappeared slightly in the introduced (left) side (Fig. 2B, red arrowheads), although the change was not very clear. To observe the striped pigmentation pattern more clearly, we dissected and detached the cuticle sheet where the melanin accumulates from the epidermis. The black stripes on the cuticle disappeared only in the introduced (left) side of the si‒Bmspz-3–treated sample (Fig. 2B, cuticle), whereas no change was observed in the right side, where no siRNA had been introduced. We confirmed by qRT-PCR that the RNA level of each target gene was reduced significantly in the left side, where the siRNA knockdown occurred (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that Bmspz-3 is involved in striped pigmentation formation in the larval epidermis and is a possible gene responsible for the Ze phenotype.

Ectopic Expression of Bmspz-3 Induces the Black Pigmentation.

To further understand how Bmspz-3 controls melanin pigmentation, we next performed overexpression of the gene by electroporation-mediated somatic transgenesis (23, 24). In this method, after plasmid DNAs were incorporated into the epidermal cells by in vivo electroporation, target genes in the donor plasmid were integrated into the host genome by piggyBac transposase in the helper plasmid (Fig. 3B). Because there were two amino acid changes between the WT and Ze strains (Fig. 3A, green letters and asterisks), we made the donor plasmids including various parts of the Bmspz-3 gene from the WT and Ze strains (Fig. 3B).

Next, we performed the overexpression of full-length constructs of spz-3 from the WT and Ze strains (Fig. 3B, Spz-3WTFL and Spz-3ZeFL), but unexpectedly, this treatment had no effect on larval pigmentation (Fig. 3C). Because Spz proteins should be processed before activation, this result may be caused by the inefficient processing of ectopically expressed Spz-3. To validate this possibility, we next made constructs of processed Spz-3, which included only the CK domain and digested just after Arg-His-Ala-Arg (RHAR) sequence (25) (Fig. 3A, red triangle). The WT and Ze Bmspz-3 CK domain regions were connected to the fibroin signal peptide (26), which is expected to work equally in both plasmids (Fig. 3B, Spz-3WTCKSP and Spz-3ZeCKSP). The ectopic expression of these plasmids in the WT larva and pupa showed melanin formation among the regions expressing EGFP (Fig. 3D). The pigmentation seemed stronger in the anterior part of the segment, suggesting that the Ze stripe region is prepatterned by molecules other than Bmspz-3.

Spz-3 Is Also Involved in Melanization of the Striped Pattern.

Phylogenetic analysis showed a highly conserved monophyly for each spz family gene among insect species, suggesting their conserved functional roles in some cellular or developmental processes (Fig. S3A). To clarify whether other spz family genes in addition to spz-3 are involved in melanin pigmentation, electroporation-mediated siRNA knockdown was performed. After siRNA treatment of Bmspz-1 (so-called spz), -2, -4, -5, and -6 in the Ze larva, a weak phenotypic change of black pigmentation was detected in si–Bmspz-2 and si–Bmspz-5 in Ze (Fig. S3B, red arrowheads). However, these effects were not as clear as that shown after Bmspz-3 knockdown (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that, although Bmspz-2 and Bmspz-5 have some redundant roles in causing pigmentation, Bmspz-3 is one of the main genes involved in melanization among the spz family genes.

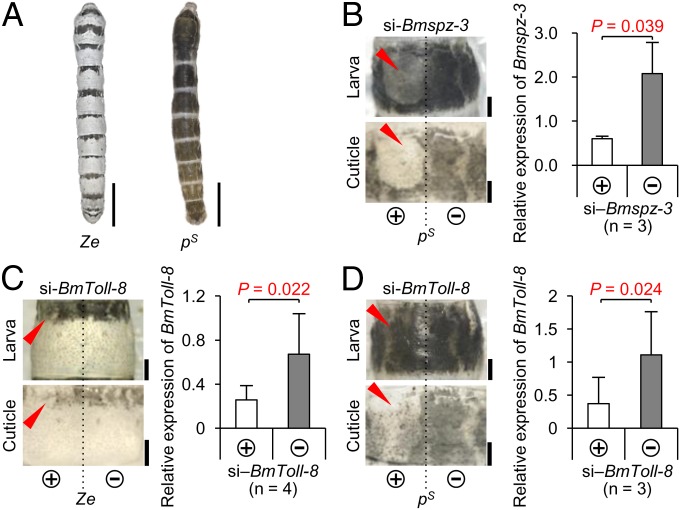

Next, we investigated whether the spz-3 and spz family genes are involved in melanin formation in the pigmentation patterns of mutant strains other than Ze. Striped (pS), which has a broader black stripe in each segment (Fig. 4A), has one allele in the p locus (linkage group 2, 3.0 cM), which encodes more than 15 different alleles and is controlled by the transcription factor, Apontic-like (Apt-like) (7). In the pS larva, knockdown with si‒Bmspz-3 by in vivo electroporation caused drastic loss of black pigmentation in the introduced (left) side (Fig. 4B, red arrowheads), similar to that observed in the Ze strain (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Bmspz-3 is also involved in the melanization process of the pS pigmentation pattern. In addition, electroporation-mediated knockdown with si‒Bmspz-2 and si‒Bmspz-5 had a weak effect on the pS melanization pattern, as shown in the Ze mutant (Fig. S3B, red arrowheads).

Fig. 4.

Spz-3 and Toll-8 signaling pathway is involved in melanin pigmentation in Ze and pS larvae. (A) Color pattern of the Ze mutant (Left) and another striped mutant pS (Right). The pS mutant has a broader black stripe in each segment than Ze. (Scale bars: 1 cm.) (B) Phenotypic changes of larva and cuticle introduced by siRNA of Bmspz-3 and relative expression levels of Bmspz-3 between the introduced (+) and nonintroduced (‒) sides of the pS mutant. (Scale bars: 1 mm.) (C and D) Phenotypic changes of larva and cuticle introduced by siRNA of BmToll-8 and relative expression levels of BmToll-8 between the introduced (+) and nonintroduced (‒) sides of the Ze (C) and pS (D) mutants. Error bars indicate the SD. Statistical comparisons were conducted using the one-sided paired Student’s t test. (Scale bars: 1 mm.)

Spz-3 Works as a Putative Ligand of Toll-8 in Melanization.

An important question is whether the Bmspz-3 gene works on melanization through the Toll signaling pathway. Because Spz-3 works as a ligand of Toll-8 in neuromuscle joint formation in D. melanogaster (27), siRNA of BmToll-8 was injected into Ze and pS larva, which resulted in the loss of pigmentation patterns in both strains (red arrowheads in Fig. 4 C and D, respectively), similar to the phenotypic change observed in the Bmspz-3-knockdown larva (Figs. 2B and 4B). This result indicates that Toll-8 is involved in the melanization process in the pigment pattern formation in silkworms.

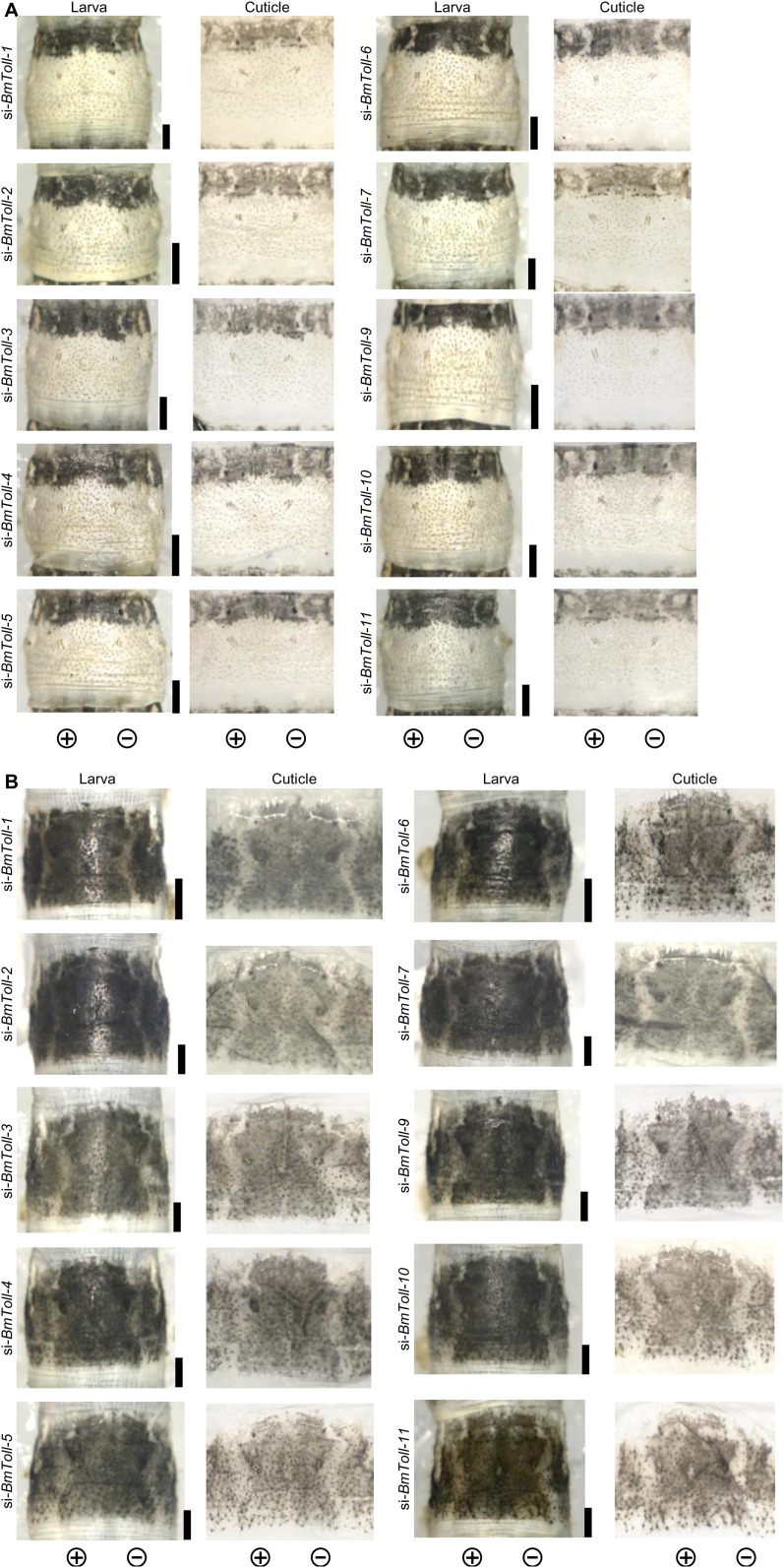

A previous report suggested that, in addition to Toll-8, 10 genes (Toll-1‒Toll-7 and Toll-9‒Toll-11) are encoded in the silkworm genome (28). To determine the possibility of involvement of these genes in larval pigmentation, we knocked down each gene’s expression by siRNA with electroporation in the Ze and pS larva. However, there was no notable change to the black pigmentation in any case (Fig. S7), suggesting that BmToll-8 is the key receptor in the Toll signaling pathway for larval pigmentation.

Fig. S7.

RNAi phenotypes of Toll family genes other than Toll-8 in the Ze and pS strains. RNAi phenotypes on the abdominal third segment of fifth instar Ze (A) and pS (B) larvae are shown. (Scale bars: 1 mm.)

The yellow mRNA Is Specifically Induced in the Ze Stripe Region.

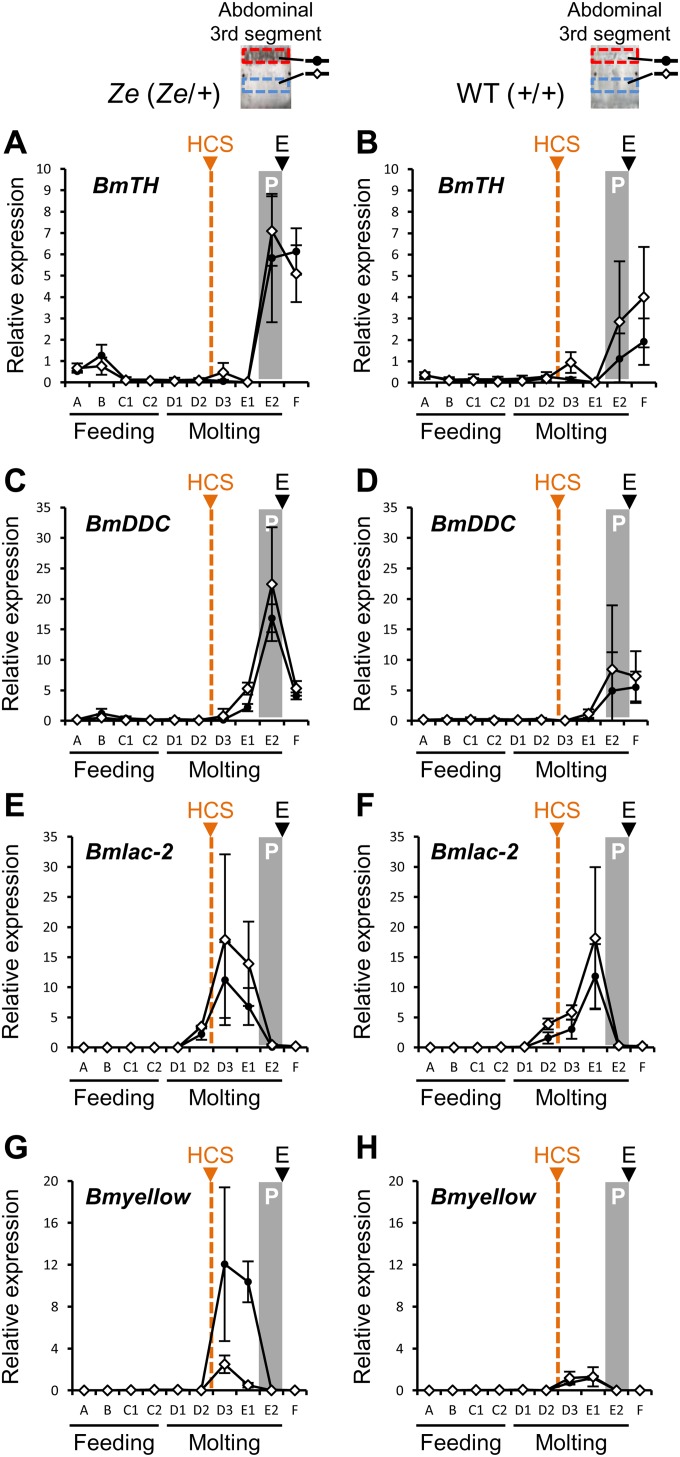

Detailed observation suggested that the black stripes in the Ze strain were composed of polymerized melanin pigments (Fig. S1A). Thus, to understand how melanin is synthesized in the striped formation in Ze, the expression profiles of genes in the melanin synthesis pathway, including tyrosine hydroxylase (BmTH), dopa decarboxylase (BmDDC), laccase-2 (Bmlac-2), and yellow (Bmyellow), were further analyzed and compared (Fig. S8). The expression of Bmlac-2, which peaked during the D3–E1 stages during the molting stage, seemed similar between the WT and Ze strains and between the pigmented and nonpigmented regions (Fig. S8 E and F). The expression levels of BmTH and BmDDC, which increased in the E2 stage just before the fourth larval ecdysis, were similar between strains and regions, although these expression levels seemed higher in the Ze mutant than in the WT strain (Fig. S8 A‒D). The increase in expression of these genes in the nonpigmented regions can be explained by the fact that both are also involved in the sclerotization of the new cuticle (29).

Fig. S8.

Expression profiles of melanin synthesis-related genes in the larval epidermis. Temporal expression patterns of genes related to melanin synthesis in larval epidermis from the third to fourth ecdysis (n = 3 in each period and strain) are shown in the mutant Ze (A, BmTH; C, BmDDC; E, Bmlac-2; G, Bmyellow) and the WT strain (B, BmTH; D, BmDDC; F, Bmlac-2; H, Bmyellow). Expression of the BmrpL3 gene was used as an internal control. Head capsule slippage and pigmentation period are denoted by HCS (orange triangle and broken line) and P (gray box), respectively, and ecdysis is denoted by E (black triangle). Black circles and white diamonds indicate the pigmented and nonpigmented areas of the Ze mutant (or corresponding area in the WT strain), respectively, which are shown as red and blue boxes in the abdominal third segment, respectively. Error bars indicate the SD.

It is remarkable that Bmyellow expression was induced specifically in the striped pigmented area of the Ze mutant from D3 to E1 during the molting stage (Fig. S8G). In the WT strain and the nonpigmented area of the Ze strain, no induction of this gene was observed (Fig. S8H). Yellow is known to be a key dopa-converting enzyme for the production of melanin in the final process (30, 31). The above results suggest that Bmspz-3 and its downstream gene network target the Bmyellow gene, which enables region-specific pigmentation in the anterior region of each segment in the Ze mutant (Fig. 5A).

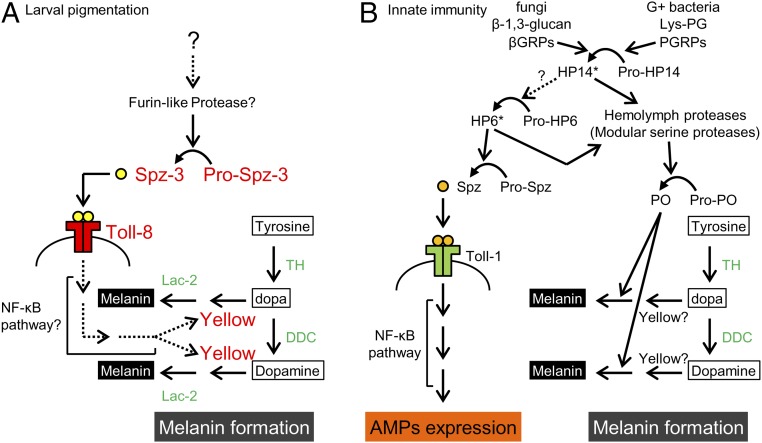

Fig. 5.

A model of the pathway involved in melanin formation and larval pigmentation. (A) A model of melanin formation through the Spz-3/Toll-8 pathway of the B. mori larval epidermis. Spz-3 may activate Toll-8 and up-regulate the yellow expression in the pigmented area (red letters). (B) Antimicrobial peptide expression through the Spz/Toll signaling pathway and melanin formation through the prophenol oxidase (pro-PO) pathway in the innate immunity in insects (based on refs. 33, 34, and 36). Factors with asterisks (HP14 and HP6) are known to be involved in these two pathways in M. sexta, but it is not clear whether these factors are conserved among insects. Broken lines indicate uncertified pathways. Green letters indicate enzymes involved in melanin synthesis. AMP, antimicrobial peptide; βGRP, β-1,3-glucan recognition protein; Lys-PG, lysine-containing peptidoglycan; PGRP, peptidoglycan recognition proteins; PO, phenol oxidase; Pro-HP, precursor of hemolymph protease; Pro-PO, precursor of phenol oxidase.

Discussion

Here, linkage mapping and functional analysis showed that the spz family gene Bmspz-3 was responsible for the silkworm mutant Ze. The knockdown experiments showed that, among the spz family genes, Bmspz-3 is mainly involved in the melanin formation of the striped pigmentation in the Ze mutant (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3B). Importantly, Bmspz-3 knockdown also resulted in the loss of pigmentation in the pS mutant (Fig. 4B), indicating that Bmspz-3 regulates a common pathway in the melanin formation of larval pigmentation (red letters in Fig. 5A). The Spz-3 signal seems to be received by the Toll-8 receptor at least in the pigmented area in the Ze and pS mutant strains. The same ligand/receptor relationship has been reported in the neuromuscular junction of D. melanogaster (27). Because our recent study has shown that the pS phenotype is controlled by the apt-like–encoding transcription factor (7), this Spz-3/Toll-8 signaling pathway likely interacts with the genetic circuit of apt-like and contributes to the phenotypic diversity of caterpillars. Although there are at least six gene classes in the spz family in insects (Fig. S3A), this report shows that an spz gene is involved in the melanization process. It has been reported that Spz-1 works as a ligand of Toll-1 and that the Toll signaling pathway is involved in dorsoventral axis formation (19), muscle development during embryogenesis (32), and the induction of antimicrobial peptide expression in innate immunity (33, 34) (Fig. 5B). In addition, Toll-6 and Toll-7 are suggested to function in the synaptogenesis of locomotor neuron networks, with two ligands, Spz-2 and Spz-5, in Drosophila (35). Although there is no direct evidence for other functions of spz family genes at present, highly conserved structures indicate some functional role of each class of spz family genes.

The infection of bacteria or fungi into the insect body induces not only the expression of antimicrobial peptide through the Spz and Toll signaling pathway but also, melanin formation through the prophenol oxidase pathway (36) (Fig. 5B). The initial step in both pathways is to recognize the lysine-containing peptidoglycan and β-1,3-glucan from the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria and fungi by peptidoglycan recognition proteins and β-1,3-glucan recognition proteins, respectively, which are followed by independent serine‒protease cascades in the two pathways (33, 34) (Fig. 5B). In Manduca sexta, it has been suggested that the protease hemolymph protease 6 (HP6) activates both pathways (34, 36), but it is not clear whether this regulation is conserved among insects. At the end of the protease cascade, Spz is processed from pro-Spz by spz-processing enzyme, and Spz and Toll binding activates NF-κB–dependent transcription (20). Although we have not yet studied the roles of NF-κB factors in larval pigmentation, we first show here the relationship between the Toll-like pathway and melanin formation. It is noteworthy that Lac-2, used for larval pigmentation, and phenol oxidase, used for melanization in innate immunity, are different enzymes structurally but show the same enzymatic activity (Fig. 5). Thus, additional comparative studies on larval pigmentation and innate immunity may reveal a more accurate pathway and overall picture of melanin synthesis.

Overexpression experiments showed that ectopic pigmentation was caused by processed CK domain constructs of Spz-3 but not caused by the full-length constructs (Fig. 3 C and D). This result indicates that the full-length constructs of Spz-3 could not be processed appropriately under the experimental conditions. A recent report on M. sexta surmised that Spz-3 processing is mediated by furin-like enzymes based on the recognition sequence RHAR (25). Thus, the full-length construct integrated by somatic transgenesis into the random site of the host genome may not be expressed appropriately when the furin-like processing enzyme is expressed. However, the result that the CK plasmids caused pigmentation of both the Ze and WT strains (Fig. 3D) indicates no functional difference caused by the amino acid change (N in WT; S in Ze) in the CK domain of Spz-3. The two amino acid difference between WT and Ze Spz-3 may not contribute to functional differences. It is possible that the phenotypic change between the Ze and WT strains is caused by different expression patterns between Ze and WT Bmspz-3 (Fig. 2A, Center), although it remains unclear whether a cis-regulatory sequence controls the temporal expression patterns of Bmspz-3.

To understand the stripe pattern formation, the molecular mechanism underlying region-specific pigmentation should be clarified. The Bmyellow gene, which directs melanization in the nearly final step, was expressed only in the future pigmented area (Fig. S8 G and H), but unexpectedly, the responsible gene for the Ze phenotype, Bmspz-3, did not show region-specific expression patterns (Fig. 2A, Center). Even with innate immunity, localized melanin formation is also triggered by HP14 in M. sexta in the most upstream step in the protease cascade by recognizing microorganisms (33). Several possibilities might explain this result. First, it is possible that some factors in the protease cascade upstream of Spz-3 processing are expressed in a stripe region-specific manner, which enables localization of the activated Spz protein only in the striped region. Second, the putative receptor Toll-8 or its downstream target genes are possibly expressed only in the future striped region. However, to date, there is no direct evidence of this possibility. The observation that the Ze-pigmented region is structurally distinct from other areas in the same segment (Fig. 1C) implies that some specific factors regulate formation of the developmental structure. This type of factor may also regulate expression of the yellow gene in a region-specific manner. Similarly, the region-specific expression of the yellow gene is observed in the spot patterns of Drosophila wings as well as the stripes of the Drosophila abdominal segments (4, 37). Some elements reported to be involved in these color patterns may contribute to the up-regulation of yellow expression in the Ze mutant. In the formation of eyespot patterns of Papilio xuthus larva, however, not only yellow but also, many other melanin synthesis genes, such as TH, DDC, and tan (38, 39), as well as the transcription factors spalt and E75 (31) are expressed specifically in the future black region. In contrast, the results of the Ze mutant showed no expression changes in TH, DDC, or lac-2 between the WT and Ze strains. The Ze strain is a spontaneous mutant isolated 1,000 or 2,000 y ago at most, and thus, the expression change of spz-3 may affect only a small number of genes. In contrast, the eyespot pattern of Papilio larvae has been selected as an adapted trait against predators over a long period, in which many genes are networked to optimize the phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Silkworms were reared on mulberry leaves or an artificial diet at 25 °C under long-day conditions (16 h light:8 h dark). Linkage analysis, qRT-PCR, 5′ and 3′ RACE, and functional analysis are detailed in SI Materials and Methods. Chemical treatment and phylogenetic analysis can be found in SI Materials and Methods. Primers used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Table S2.

Primers for cloning, 5′ and 3′ RACE of candidate genes, construction of overexpression plasmids, and qRT-PCR

| Target gene and name | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

| Cloning | |

| Bm8846 | |

| 8846-F3 | ATGCTACGAACGCCACTACGC |

| 8846-F5 | CCGGGTCAAACTTTGGACTT |

| 8846-F6 | GCTGGACACAAGGATTCGTC |

| 8846-R3 | TTATGTATCTTTGTTTGCATCCTTGGC |

| 8846-R4 | GCTTCCAATCAACATCATCG |

| 8846-R5 | ACATTTATGTATCTTTGTTTGCATCC |

| 8846-R6 | TGGACTGCAGTGTGCAGCTCCA |

| Bmspz-3 | |

| 9035-F3 | TGGTGTTAGCACGAGCGGACAG |

| 9035-F4 | CGATGAGAAACTCAGTGGGCTGTG |

| 9035-F5 | AGAGTGTATGTGGCATCGGTGCGA |

| 9035-F6 | GCATGTCATGTCTTGCCGCCATAAC |

| 9035-R9 | GTCGAAGCCGGACTGAAGCCTT |

| 9035–5RACE-F2 | AGTCAGTAGTGGTCGCGCGCGA |

| 9036-F4 | ATAGAACACTGCCATTGTATTGTTACG |

| 9036-R10 | CCGTCAAGGGAATGAAAATTACAAATC |

| 9036-R3 | CCGGTCGTGGTTTTGCTGCAAGTT |

| 9036-R4 | GCTTTGATTTGCGGAGAGTGAAGTGA |

| 9036-R5 | AGTTTCCAGCCGTTGGGCAATACAA |

| Bmago-3 | |

| 9037-F3 | ATGATGGACTCTCCCTCACAATCT |

| 9037-F4 | CGCACACGTCGTTTGAGCGAA |

| 9037-F5 | AGATTTCATGATATGCCTCATTCCGG |

| 9037-R3 | CTGTTACGTATCCAGGCCAAACTT |

| 9037-R4 | TAGACGACTCTTGGCAGTTTCGTT |

| 9037-R5 | GTATGCTGATGCTCCAAAGCGT |

| 9037-R6 | GCACGCACTGTCCCACTAGAT |

| 5′ and 3′ RACE | |

| Bm8846 | |

| 8846–3RACE-F1 | GCCAGCGGACTGCCTGTGGTAACAGATGC |

| 8846–3RACE-nest-F1 | ATCGTGCTCTTCTTGTCCAAGCT |

| 8846–5RACE-nest-R1 | GCGTAGTGGCGTTCGTAGCAT |

| 8846–5RACE-R1 | GGCAAGTGGACTGCAGTGTGCAGCTCCA |

| Bmspz-3 | |

| 9035–5RACE-nest-R1 | ACTTTCCGCTCGTGACGTCC |

| 9035–5RACE-R1 | GAGTGGCGTGGGATCGTCTACACCGAACGGG |

| 9036–3RACE-F1 | TTCGACGCCGCCCGGCAGCCGAGTGAAG |

| 9036–3RACE-F2 | GCCTGACGCGCAGGCCGTCAACAGTACCG |

| 9036–3RACE-F3 | CTCGTTTACAGACGTGACCACA |

| 9036–3RACE-nest-F1 | GGTGGATGCGTGCGAAAGCAA |

| 9036–3RACE-nest-F2 | CCCTCAACTCCGCAAGGAAACT |

| 9036–3RACE-nest-F3 | ATCAGTACCAAAACTTGTTGGAGGC |

| Bmago-3 | |

| 9037–3RACE-F3 | CCGAATCCCGGGACCGTGGTCGATCACTGT |

| 9037–3RACE-F4 | ACACTAGGATCTTCCTGAAGTCGA |

| 9037–3RACE-nest-F3 | AACGAGACGGGACTGGTACGAT |

| 9037–5RACE-nest-R3 | CCTATACTCACTCCTGAAGTACTA |

| 9037–5RACE-nest-R4 | TACTAGGAGTTGCACTTGCAATGGT |

| 9037–5RACE-R3 | GCCAGCATCAATGCTGCTGCGCGTCCTCT |

| Plasmid construction | |

| Spz3ZeFL, Spz3WTFL | |

| infu-spz3-F1 | CCACCGGTCGCCACCatggctttggtaaattttacgctcgc |

| infu-spz3-R2 | AGAGTCGCGGCCGCTTCAAGGCTTACACCTGCAAACGCA |

| Spz3ZeCKfib, Spz3WTCKfib | |

| infu2-spz3-F | actaattcaaggatccaccggtcgccaccATGGCTTTGGTAAATTTTACGCTCGC |

| FibHSigP-R1 | tgcatttgtataagcgacatactgcagagcgcagcacaagat |

| Spz_CysKnot_F | GCTTATACAAATGCAcaggcctckaacacacaaytg |

| spz3CK-NotI-R1 | AGAGTCGCGGCCGCT |

| Spz3Ze(1–60), Spz3WT(1–60) | |

| BamHI-spz3(1-60)-F1 | ACTAATTCAAGGATCatggctttggtaaattttac |

| Bm_spz3_60aa_R(4mRFP) | GTCCTCGGTGTTGTCttgattcgaagggggactgaa |

| opt-mRFP-F | gacaacaccgaggacgtcatcaagga |

| 15bp-opt-mRFP-R | TCTAGAGTCGCGGCCGCctactgggagccggagtggcggg |

| qRT-PCR | |

| BmrpL3 | |

| rPL3_qPCR_03-F | ATCAAGGGTTGCTGCATGGGACCT |

| rPL3_qPCR_03-R | GGTTGATCTTTTCTAGTGCAGCCCTC |

| Bm8846 | |

| 8846_qPCR02-F | TGGTAACAGATGCTAAACCTTCGGGT |

| 8846_qPCR02-R | TGTACAGTAGGACGAATCCTTGTGTC |

| Bmspz-3 | |

| spz3qPCR01-F | CAAAACACAGCTCCACGCGGTAC |

| spz3qPCR01-R | CCGTTTCGTAGAAGTATCGGACCTTG |

| Bmago-3 | |

| 9037_qPCR02-F | GGGTTCTGTTGTTCACTCAGAGGGA |

| 9037_qPCR02-R | GAGGGGTACCAATTCAGCGTCAGA |

| BmToll-8 | |

| BmToll8_qPCR01-F | CAAGCATTGTCGGTTCTTTCTG |

| BmToll8_qPCR01-R | TTTCGGAGTGCTTGTGGATTT |

| BmTH | |

| BmTH_qPCR02-F | CGCCTTTCCACACACCTGAACC |

| BmTH_qPCR02-R | GGGATGCAAGGCCAATTTCTTGCG |

| BmDDC | |

| BmDDC_qPCR02-F | GATGAAGACATCCGCAACGGTCTCA |

| BmDDC_qPCR02-R | ATCTCCAATTTCGTCAAGAGCGTCG |

| Bmlac-2 | |

| lac-2_qPCR01-F | CGAACCACCAAGGATCTGTTACTATC |

| lac-2_qPCR01-R | GGCAATGAGACCAGACCACATTCGT |

| Bmyellow | |

| Bmyellow_qPCR01-F | GTCAGCGTTCCTAGGTGGCG |

| Bmyellow_qPCR01-R | TCGAAGCTCGGGTAGGGCGTT |

SI Materials and Methods

Silkworm Strains.

The Ze mutant strain, f40, and the pS mutant, f34, were obtained from the Institute of Genetic Resources, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan. The WT strains N4 and p50 were gifts from T. Shimada and T. Kiuchi, University of Tokyo, Tokyo. Silkworms were reared on mulberry leaves or an artificial diet at 25 °C under long-day conditions (16 h light:8 h dark).

Linkage Analysis.

For positional cloning of the Ze locus, 11 F1 heterozygous males were obtained from a single-pair cross between a Ze strain f40 male and a p strain N4 female, and each was backcrossed with a p strain female. A total of 1,472 BC1 fifth instar larvae (Ze phenotype, 733 individuals; WT phenotype, 739 individuals) were used for low-resolution mapping. Furthermore, for fine-resolution mapping, 1,663 BC16 fifth instar larvae (Ze phenotype, 822 individuals; WT phenotype, 841 individuals) were used. Genomic DNA was extracted from parent moths, F1 moths, and each BC1 and BC16 fifth instar larvae using DNAzol solution (Invitrogen Corporation). For genetic analysis, SNP PCR markers were constructed (Table S1). The homozygous (A) or heterozygous (H) state of BC16 was determined (detailed in Fig. S2). Genotyping was performed by direct PCR sequencing. The PCR reactions were performed using ExTaq polymerase (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The purified genomic DNA was used as the PCR template. Each PCR fragment was confirmed to be a single band by gel electrophoresis and treated with Alkaline Phosphatase, shrimp (Roche Applied Science) and Exonuclease I (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) to remove primers and dNTP. Purified DNA was sequenced using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3730xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing data were analyzed using a trial version of Sequencher 4.8 (Gene Codes Corporation).

qRT-PCR.

Staging of fourth instar Bombyx mori larvae was based on the spiracle index. After anesthetization of the Bombyx larvae on ice, the epidermis was dissected in PBS (pH 7.4). Epidermal tissues from the black-pigmented anterior region and the middle region, which is white-pigmented on the dorsal side of the abdominal third segment in the mutant Ze, were collected, and the muscles, fat bodies, and trachea were removed as well as possible. The collection areas are indicated as red and blue broken rectangles in Fig. 2A and Fig. S8. Also, the equivalent regions of the epidermis of the p strain were collected as a control. Total RNA was isolated using the TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation) and purified via phenol/chloroform extraction after treatment with 0.2 U DNase I (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, reverse transcription was conducted with a random primer (N6) using the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sample was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation before use in qRT-PCR analysis. The mRNA expression levels of Bmspz-3, Bmago-3, Bm8846, BmToll-8, BmTH, BmDDC, Bmyellow, and Bmlac-2 were determined using the Real-Time PCR System with power SYBR green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the StepOne System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). BmrpL3 was used as an internal control. Each primer set is listed in Table S2 (qRT-PCR). The relative expression levels of target genes were calculated by the relative standard curve method. Expression levels of mRNA for each sample were determined with more than three biological replicates. Statistical comparisons were conducted using the one-sided paired Student’s t test.

5′ and 3′ RACE.

To determine the sequence of transcription of the candidate genes Bm8846, Bmspz-3, and Bmago-3, 5′ and 3′ RACE was performed using the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primers were designed from the nucleotide sequences of the predicted genes [BGIBMGA008846 (Bm8846), BGIBMGA009035 and BGIBMGA009036 (Bmspz-3), and BGIBMGA009037 (Bmago-3)] and listed in Table S2. PCR products were subcloned into a pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega Corporation). Nucleotide sequences were determined using an ABI3130xl genetic analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

siRNA for Gene Knockdown.

siRNAs of Bm8846 (target sequence: 5′-TTGCTATTAAAACCTGAAATATT-3′), Bmpz-3 (target sequence: 5′-TCGAGAACAAAGCGTTGATAAAA-3′), Bmago-3 (target sequence: 5′-TTGTAACGAGCAGTGCACAAATT-3′), other spz family genes (target sequence: spz-1, 5′-TACAATCGAGGAGTTCAACGAAA-3′; spz-2, 5′-ATGCGTTCAAGTTTACAACTACC-3′; spz-4, 5′-GTGAAGAACGACACATATCAATC-3′; spz-5, 5′-CGCGGTATAACCCAAACGAGTGG-3′; spz-6, 5′-CGCCATCAACGGCGATAACGAAA-3′), and Toll family genes (target sequence: Toll-1, 5′-TAGTCATAATCGTATTTCGGAAA-3′; Toll-2, 5′-TTCTCCATTAGCTATTCCAAACA-3′; Toll-3, 5′-TGCTCTCCAAGAACTTCCTGTCG-3′; Toll-4, 5′-GGGACTTCTCTTAAAGAAGCACA-3′; Toll-5, 5′-CTCTAATTGAAGCACAGATCAAC-3′; Toll-6, 5′-TACGATGAATCCGTATTTGGTGG-3′; Toll-7, 5′-CCCTAAAGACGAGGAGTTTGTAA-3′; Toll-8, 5′-GACTAGACTTGAGCGAAAATAAT-3′; Toll-9, 5′-TAGAGACAAAGGATTACAAGTAT-3′; Toll-10, 5′-TGCGTAGATGAGCTTTCCTTTCC-3′; Toll-11, 5′-TTGAAGTGTTGTCATCCTTAAGG-3′) were designed based on the criteria by Yamaguchi et al. (40). Universal negative control (Nippon gene) was purchased as negative control. siRNA (concentration: 250 μM, volume: 1.0 µL) was injected from the abdominal fifth segment into the hemolymph of third or fourth instar Ze larvae with a glass needle connected to a microinjector (FemtoJet; Eppendorf AG). Intermediately after the injection, two separated drops of PBS were placed on the larvae, which were used as electrodes to avoid serious damage, and electrical stimulation was applied (conditions: five square pulses of 20 V, 280-ms interval) using the electroporation-mediated somatic transgenesis method (EMST) (23, 24). Phenotypic effects to the fifth instar larvae were observed under a KEYENCE VH-5500 microscope system (Keyence Corporation) or a Leica M165FC stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems). Furthermore, to clearly visualize the RNAi effect of cuticular pigmentation, the siRNA-treated samples were incubated in 10% SDS for a minimum of 12 h at room temperature, which enabled easy removal of the epidermis from the cuticle, and they were observed and compared between the introduced (left) side and the nonintroduced (right) side with the KEYENCE VH-5500 microscope system. To quantify the mRNA levels of target genes using qRT-PCR, the introduced epidermis and the nonintroduced epidermis of the abdominal third segment were collected from the same individual at the period D3 when high expression of Bmspz-3, at the fourth instar stage, was observed.

Plasmid Construction for piggyBac-Based Transgene Expression.

Recombinant plasmids were constructed from a piggyBac target vector (pPIGA3GFP::A3DsRed2) containing an EGFP and DsRed2 reporter genes, each driven by the Bmactin-3 promoter (A3 in Fig. 3B). The ORF of Bmspz-3 of the f40 (Ze) and N4 (p) strains was PCR-amplified using iProof polymerase (Bio-Rad Laboratories) under the following conditions: 98 °C for 10 s; 32 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The enzyme protein was removed from the PCR solution using a mixture of phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol. The PCR products were purified by ethanol precipitation. The pellet was rinsed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in 7 µL of ultrapure water (Merck Millipore Billerica). The addition of dATP to the 3′ end of the PCR products was carried out using ExTaq master mix (TaKaRa) at 70 °C for 30 min. Each PCR product was subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega Corporation). Then, colony PCR was conducted using the PCR primers listed in Table S2 (plasmid construction) and iProof high-fidelity polymerase (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: 98 °C for 10 s; 22 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega Corporation) from each PCR solution was removed using the restriction enzyme DpnI (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) at 37 °C for 1 h. The PCR products were purified using the GenElute PCR Clean-Up Kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation). The amplified ORF of Bmspz-3 was replaced with DsRed2 in the piggyBac target vector using an In-Fusion HD Liquid Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) (Spz-3ZeFL and Spz-3WTFL in Fig. 3B). In addition, a signal peptide of fibroin heavy chain gene (FibH) (26) and the C terminus of the Bmspz-3 ORF, which contained a cystine knot domain, were amplified by PCR using the genomes of the f40 and p50 strains, respectively. These gene fragments were used to replace DsRed2 in the piggyBac target vectors (Spz-3ZeCKSP and Spz-3WTCKSP in Fig. 3B).

Transgene Expression.

The donor plasmid, which contained both the gene of interest and the EGFP reporter gene, and the helper plasmid pHA3PIG, which encoded the piggyBac transposase driven by the BmActin A3 promoter, were mixed at a final concentration of 1.0 µg µL−1 each and injected into second instar larvae at 0.5–1.0 µL. Then, phenotypic changes were observed at the fifth instar larval and pupal stages. Procedures of injection and the EMST method are described above (see above).

Chemical Treatment.

To determine whether the black striped marking of Ze was composed of melanin pigments, the epidermal samples of fourth instar larvae were washed in acetone at room temperature for 12 h, treated with 5 M NaOH at room tempertature for 4 h, and hydrolyzed in 1 M HCl at 90 °C for 90 min according to the method described by Koch and Kauffman (41) with some modifications. The samples with chemical treatment were observed under the stereomicroscope (Leica M165FC; Leica Microsystems).

Phylogenetic Analysis.

To identify orthologous relationships among spz family genes in insects, phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the CK domain sequence of genes, which was predicted by Pfam (pfam.xfam.org/). Information on spz family genes in B. mori (Bmspz-1: BMgn002397, Bmspz-2: BMgn010869, Bmspz-3: BMgn009035 and -9036, Bmspz-4: BMgn008841, Bmspz-5: BMgn012697, Bmspz-6: BMgn013880), Drosophilia melanogaster (spz-1: AAF56658.1, spz-2: NP_729009.2, spz-3: AAF52574.2, spz-4: NP_609504.2, spz-5: AAF47694.1, spz-6: NP_611961.1), Manduca sexta (spz-1: ACU68553.1, spz-2: Msex2.09986-PA, spz-3: Msex2.04433-PA, spz-4: Msex2.03391-PA, spz-6: Msex2.07505-PC), Danaus plexippus (spz-1: EHJ70909.1, spz-2: EHJ66092.1, spz-6: EHJ65295.1), Anopheles gambiae (spz-1: XP_310768.4, spz-2: AGAP006483-PA, spz-3: AGAP008360-PA, spz-4: XP_317626.4, spz-5: XP_308593.4), Aedes aegypti (spz-1: AAEL013434-PA, spz-2: AAEL001435-PA, spz-3: AAEL008596-PA, spz-4: XP_001652981.2, spz-5: XP_001654338.1), Tribolium castaneum (spz-1: EEZ99207.1, spz-3: NP_001153625.1, spz-4: EFA09263.1, spz-5: XP_970793.1, spz-6: NP_001164082.1), and Apis mellifera (spz-2: XP_006562326.1, spz-3: XP_006566243.1, spz-6: XP_391869.3) were obtained from the NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank), KAIKObase (sgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/KAIKObase/), ManducaBase (agripestbase.org/manduca), and VectorBase (https://www.vectorbase.org) public databases. Amino acid sequence alignment was generated with the multiple sequence alignment by log expectation algorithm. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method (LG + G + I model) with Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software, version 6.0. Bootstrap analysis was performed to assess confidence levels for various phylogenetic lineages (1,000 replicates). Bootstrap values >50% are provided in Fig. S3A.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Narukawa for her help with the practical technique of linkage analysis and K. Chagi and N. Uemura for technical support in some experiments. We also thank Drs. T. Kojima and K. Mita for helpful comments on the manuscript. Silkworm strains used in this study were supported by the National Bio-Resource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan. This work was supported by MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 20017007, 22128005, and 15H05778 (to H.F.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1707896114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cott HB. Adaptive Coloration in Animals. Methuen Publishing; London: 1940. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prudic KL, Oliver JC, Sperling FA. The signal environment is more important than diet or chemical specialization in the evolution of warning coloration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19381–19386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruxtion GD, Sherratt TN, Speed MP. Avoiding Attack. The Evolutionary Ecology of Crypsis, Warning Signals and Mimicry. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gompel N, Prud’homme B, Wittkopp PJ, Kassner VA, Carroll SB. Chance caught on the wing: cis-Regulatory evolution and the origin of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Nature. 2005;433:481–487. doi: 10.1038/nature03235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner T, Koshikawa S, Williams TM, Carroll SB. Generation of a novel wing colour pattern by the Wingless morphogen. Nature. 2010;464:1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature08896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi J, et al. Periodic Wnt1 expression in response to ecdysteroid generates twin-spot markings on caterpillars. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1857. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoda S, et al. The transcription factor Apontic-like controls diverse colouration pattern in caterpillars. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4936. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monteiro A, et al. Differential expression of ecdysone receptor leads to variation in phenotypic plasticity across serial homologs. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Reed RD. Genome editing in butterflies reveals that spalt promotes and Distal-less represses eyespot colour patterns. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11769. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadeau NJ, et al. The gene cortex controls mimicry and crypsis in butterflies and moths. Nature. 2016;534:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature17961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caro T, Izzo A, Reiner RC, Jr, Walker H, Stankowich T. The function of zebra stripes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallarino R, et al. Developmental mechanisms of stripe patterns in rodents. Nature. 2016;539:518–523. doi: 10.1038/nature20109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irion U, Singh AP, Nüsslein-Volhard C. The developmental genetics of vertebrate color pattern formation: Lessons from zebrafish. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;117:141–169. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnett JB, et al. Stripes for warning and stripes for hiding: Spatial frequency and detection distance. Behav Ecol. 2017;28:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tullberg BS, Merilaita S, Wiklund C. Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: Functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272:1315–1321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mita K, et al. The genome sequence of silkworm, Bombyx mori. DNA Res. 2004;11:27–35. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia Q, et al. Biology Analysis Group A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori) Science. 2004;306:1937–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.1102210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyama K. Studies on the hybridology of Insects I. On some silkworm crosses with special reference to Mendel’s law of heredity. Bull Coll Agric Imp Univ Tokyo. 1906;7:259–393. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belvin MP, Anderson KV. A conserved signaling pathway: The Drosophila toll-dorsal pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:393–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetru C, Hoffmann JA. NF-kappaB in the immune response of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000232. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto K, et al. A BAC-based integrated linkage map of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R21. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agar JN, et al. Modular organization and identification of a mononuclear iron-binding site within the NifU protein. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2000;5:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s007750050361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ando T, Fujiwara H. Electroporation-mediated somatic transgenesis for rapid functional analysis in insects. Development. 2013;140:454–458. doi: 10.1242/dev.085241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujiwara H, Nishikawa H. Functional analysis of genes involved in color pattern formation in Lepidoptera. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2016;17:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao X, et al. The immune signaling pathways of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;62:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang SP, Guo TQ, Guo XY, Huang JT, Lu CD. Structural analysis of fibroin heavy chain signal peptide of silkworm Bombyx mori. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2006;38:507–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballard SL, Miller DL, Ganetzky B. Retrograde neurotrophin signaling through Tollo regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:1157–1172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng TC, et al. Identification and analysis of Toll-related genes in the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noh MY, Muthukrishnan S, Kramer KJ, Arakane Y. Cuticle formation and pigmentation in beetles. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2016;17:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittkopp PJ, Vaccaro K, Carroll SB. Evolution of yellow gene regulation and pigmentation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1547–1556. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Futahashi R, Shirataki H, Narita T, Mita K, Fujiwara H. Comprehensive microarray-based analysis for stage-specific larval camouflage pattern-associated genes in the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. BMC Biol. 2012;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halfon MS, Keshishian H. The Toll pathway is required in the epidermis for muscle development in the Drosophila embryo. Dev Biol. 1998;199:164–174. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi D, Garcia BL, Kanost MR. Initiating protease with modular domains interacts with β-glucan recognition protein to trigger innate immune response in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13856–13861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517236112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanost MR, et al. Multifaceted biological insights from a draft genome sequence of the tobacco hornworm moth, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;76:118–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIlroy G, et al. Toll-6 and Toll-7 function as neurotrophin receptors in the Drosophila melanogaster CNS. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1248–1256. doi: 10.1038/nn.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Jiang H. Prophenoloxidase activation and antimicrobial peptide expression induced by the recombinant microbe binding protein of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;83:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong S, Rokas A, Carroll SB. Regulation of body pigmentation by the Abdominal-B Hox protein and its gain and loss in Drosophila evolution. Cell. 2006;125:1387–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Futahashi R, Fujiwara H. Melanin-synthesis enzymes coregulate stage-specific larval cuticular markings in the swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. Dev Genes Evol. 2005;215:519–529. doi: 10.1007/s00427-005-0014-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Futahashi R, Banno Y, Fujiwara H. Caterpillar color patterns are determined by a two-phase melanin gene prepatterning process: New evidence from tan and laccase2. Evol Dev. 2010;12:157–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi J, Mizoguchi T, Fujiwara H. siRNAs induce efficient RNAi response in Bombyx mori embryos. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch PB, Kaufmann N. Pattern specific melanin synthesis and DOPA decarboxylase activity in a butterfly wing of Precis coenia Hübner. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;25:73–82. [Google Scholar]