Abstract

Background

Fibromyalgia (FMS) is a pain condition affecting 2–6% of US adults; effective treatment remains limited. Determinants of nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplement (NVNM) use among adults with FMS are not well-studied. We investigated the relation of NVNM use to FMS, and trends, in two nationally representative samples of US adults ≥18 years.

Methods

Data were drawn from 2007 and 2012 National Health Interview Surveys (N's = 20127 and 30672, resp.). Logistic regression was used to examine associations of FMS to NVNM use (past 12 months) and evaluate potential modifying influences of gender and comorbidities. Multivariate models adjusted for sampling design, demographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors.

Results

FMS was significantly higher in 2012 than in 2007 (1.7% versus 1.3%), whereas NVNM use decreased (57% versus 41%; p < 0.0001). Adults reporting diagnosis were more likely to use NVNMs within 12 months, 30 days, or ever relative to adults without; positive associations remained significant after controlling for demographics, lifestyle characteristics, medical history, and other confounders (ranges: 2007 and 2012 AORs = 2.3–2.7; 1.5–1.6, resp.; p's < 0.0001).

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional study of two national samples, NVNM use was strongly and positively associated with FMS, highlighting the need for further study.

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a rheumatologic neuropathic chronic pain syndrome affecting approximately 2.7% of populations of all ages across the world [1], including an estimated 1.8–6.4% of those in the US [2, 3]. FMS is characterized by a constellation of somatic symptoms (e.g., fatigue, sleep, mood disturbances, and cognitive impairment) that are typically present in addition to widespread pain [4]; the etiology of FMS is largely unknown [4]. Additionally, those with FMS may also experience high rates of comorbidity, such as osteoarthritis [5], autoimmune [6], kidney [7], respiratory [7], and cardiovascular [7, 8] disease, gastrointestinal conditions [7, 9], and headache [1, 7, 10]. Although FMS affects both sexes and people of all ages, the majority of US cases occur in Caucasian, middle-aged women [11, 12].

The chronic widespread pain characterizing FMS is difficult to manage, and many physicians remain unfamiliar with FMS diagnostic criteria and treatment [13] often making it difficult for patients to obtain an accurate FMS diagnosis and appropriate care. Although a lack of efficacy evidence for opioids as FMS treatment exists [14, 15] and opioid overdose deaths have more than tripled since 1999 [16, 17], FMS patients may receive opioid therapy [18]. Common treatments for FMS include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants, and other pain medications [19]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which may carry side effects for as many as 25% of long-term users [20], are not currently recommended for FMS by any guidelines [19]. Although three drugs are FDA-approved for FMS treatment [21], these medications may carry significant side effects for some [22] and are not always effective for all [19]. Thus, patients may turn to complementary health approaches (CHAs, defined as medical/healthcare systems or practices used outside of mainstream medicine [23]) to manage symptoms [24]; back, neck, and joint pain are among the most commonly reported conditions for which patients use CHAs in the US [25, 26].

Nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements (NVNMs) are a type of CHA used by nearly twenty-five percent of US adults with a musculoskeletal disorder [25] and include animal- and plant-derived products (i.e., fish oil, herbal dietary supplements). The extent and efficacy of NVNMs, particularly herbal dietary supplements, are largely unknown [27, 28]. Although a handful of large surveys have documented high rates of herbal and other NVNM use for chronic pain syndromes [24, 25, 29, 30], and anecdotal accounts indicate that a wide range of herbs have been used for the treatment of FMS [31], rigorous investigations regarding the prevalence and correlates of NVNM use in FMS remain limited. To address these gaps, we assessed the relation of FMS to NVNM use in two large, representative samples of US adults and examined potential changes in prevalence rates for NVNM use among those with FMS over a 5-year time period.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

Participants for this study were drawn from two nationally representative samples of 23,501 and 34,525 US adults (National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), 2007 and 2012, resp.). The NHIS is an annual national, cross-sectional household survey of the noninstitutionalized US population and is administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics. A supplement (adult alternative medicine) to the core individual, family, and household surveys asked participants about use of a broad range of CHAs, including herbs and other NVNMs, for both years. All questions were administered in a personal interview format. Adult response rates to the NHIS were 78.3% in 2007 and 79.7% in 2012, respectively [32].

The NHIS is the only national, public-use survey that includes comprehensive sets of questions regarding NVNM and other CHA use. Both 2007 and 2012 surveys used a stratified multistage probability design weighted on age, sex, and race/ethnicity, using 2000 and 2010 Census data for each, respectively. Both surveys oversampled Asian, Black, Hispanic, and minority elderly populations. Thus, each person in the covered population had a known nonzero probability of selection. Additional project details have been described elsewhere [32].

2.2. Study Population

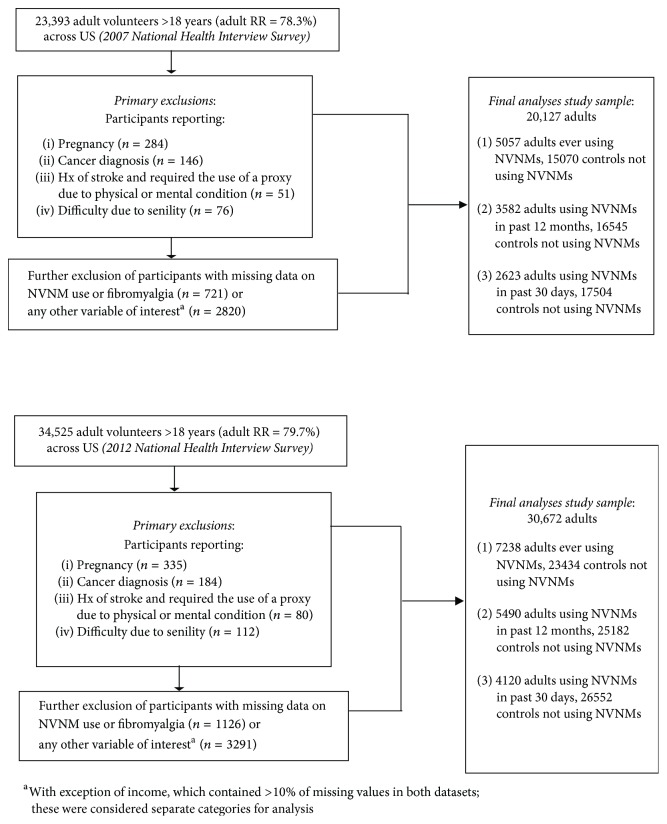

Our analysis excluded participants who were <18 years of age, were pregnant, had functional limitation(s) due to senility, had a stroke and used a proxy to complete the interview, or had current cancer; those missing data on key covariates were also excluded, as were participants with extreme values for exercise (>6,000 minutes per week) in order to eliminate potential information bias. Further exclusion of persons with missing data on FMS and NVNM use (at 30 days, at 12 months, or ever using NVNMs) yielded final study samples of 20,127 and 30,672 adults for 2007 and 2012, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram for nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplement (NVNM) use in two national datasets.

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Outcome Variables

The main outcome variable for this study was the reported use of NVNMs within the past 12 months (Y/N). We additionally assessed use of NVNMs within the previous 30 days (Y/N) and ever (Y/N). Briefly, survey participants were shown a card with a list of NVNMs (for which the majority were comprised of herbs or their compounds; 2007 list: 44 NVNM items with additional queries for up to two combination supplements, and 2012 list: 21 NVNM items with additional queries for up to two combination supplements) and queried for a dichotomous response regarding consumption of any “herbal or other nonvitamin supplements.” NVNMs included those labelled “dietary supplement” and in the form of pills, capsules, tablets, or (2012) liquids (including tinctures) and did not include homeopathic or cannabis products.

2.3.2. Exposure Variable

Our main exposure was fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) (Y/N), ascertained as an affirmative response to fibromyalgia after being asked “Have you EVER been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia? Which of these were you told you had?”

2.3.3. Covariates

Demographics, lifestyle factors, health conditions, and medical care-related factors known or suspected to be associated with CHAs, NVNM use, and/or FMS were considered a priori as potential covariates in multivariate models. Demographic factors assessed included age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income, marital status, geographic region, and place of birth. Additional related factors included insurance status, annual family out-of-pocket medical costs, and delay of care due to concerns over cost. Lifestyle factors included smoking status, alcohol use, exercise, BMI (using the National Institutes of Health clinical classifications scores) [33], health status, and substance abuse. Health conditions included self-reported history of physician-diagnosed diabetes, kidney disease, gastrointestinal disorder, respiratory conditions, dyslipidemia, liver condition, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, nonspecific arthritis, gout, migraines, mental health condition, insomnia, and previous cancer diagnosis. These variables are described in greater detail below.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We conducted complete-case analyses using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) and used sampling weights to account for complex survey procedures; these were adjusted for the probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and poststratification [34]. We merged NHIS family, person, household, sample adult, and adult alternative health files for each year and measured sample characteristics, including frequencies/prevalence rates of NVNM use (previous or current use, past 12 months, and past 30 days) for 2007 and 2012, respectively; we extrapolated estimates to generate population frequencies using NHIS sampling weights. Weighted t-tests and Rao-Scott Chi-square tests were used to determine significant differences by NVNM use status for three outcome time points in both survey years; significant factors were included in models as covariates. We also used a DOMAIN statement to keep our exclusions separate while maintaining the integrity of sampling weights and used Chi-square and t-tests to determine significant changes between 2007 and 2012 on weighted frequencies and means of all items, in addition to number of different NVNMs used, physician disclosure of NVNM use, and use of other CHAs. We considered trends between time points significant if there was no overlap in weighted percentage confidence intervals. Differences between participants with versus without missing data were assessed. All p values shown are two-sided at p ≤ 0.05.

Weighted logistic regressions were used to evaluate the independent associations of FMS diagnosis to NVNM use in the last 30 days or 12 months or ever. All multivariate models were adjusted for demographics and medical care-related factors; additional models also included lifestyle characteristics and health conditions.

Demographic characteristics included age (evaluated as both a continuous and categorical variable (18–24, 25–44, 45–64, 65–74, and 75+ years)), sex (male/female), race (“non-Hispanic White,” “non-Hispanic Black,” “Hispanic,” “Asian,” and “other”), marital status (“married/cohabitating,” “divorced/separated/widowed,” and “single”), education (“≤some HS,” “HS/GED,” “some college/AA/tech,” and “bachelor's degree+”), employment (“employed for pay,” “employed but not for pay,” and “unemployed”), income ($1–$24,999; $25,000–$44,999; $45,000–$74,999; $75,000+; “do not know;” and “missing”), geographic region (“northeast,” “midwest,” “south,” and “west”), and place of birth (US-born/other). Medical care-related factors included insurance status (“uninsured,” “Medicaid,” “Medicare,” “disability,” and “private”), annual out-of-pocket medical costs (“none”; <$500; $500–$1999; $2000–$2999; $3000–$4999; $5000 and over; and “do not know”), and delayed access to care because they “could not afford” or “worried about cost” (yes/no). Additional analyses also controlled for lifestyle-related factors, including BMI (evaluated as continuous and categorical (<18.5 = “underweight,” 18.5–25 = “underweight or normal weight,” 25–29.9 = “overweight,” 30–34.9 = “obese class 1,” and 35+ = “obese classes 2/3”)) [35]; tobacco use (“current smoker,” “former smoker,” and “never smoked”); alcohol use (“none,” “light,” and “moderate to heavy”); substance abuse other than tobacco or alcohol in past year (yes/no); and physical activity (continuous, in minutes/week).

In our fully adjusted models, we also evaluated the potentially confounding influence of self-reported health status (“excellent/very good/good,” “fair,” and “poor”), specific health conditions, and total number of health conditions; this comorbidity index was created from 0–13 participant-reported conditions, including a history of (1) diabetes; (2) kidney disease; (3) gastrointestinal disorder (including history of ulcers, inflammatory/irritable bowel disease, or constipation severe enough to require medication in the past year and/or (2012) abdominal pain, digestive allergy, and/or heartburn in the past year); (4) respiratory conditions (history of asthma or emphysema and/or chronic bronchitis); (5) dyslipidemia; (6) liver condition; (7) rheumatoid arthritis; (8) cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, angina, and/or heart attack); (9) hypertension; (10) nonspecific arthritis; (11) gout; (12) migraines; and (13) mental health condition (depression, phobias, and/or being often anxious in past year and/or ever having bipolar disorder). Health conditions were evaluated both collectively and individually; insomnia in the past year and previous cancer diagnosis were evaluated individually.

We also assessed the potential modifying influence of gender and presence of comorbid health conditions (0-1 versus 2+) on the association between FMS and NVNM use at each outcome time point and for each survey year by including the corresponding multiplicative-interaction term in age-adjusted models.

3. Results and Discussion

Relative to participants with complete data in both survey years, those with missing data on key covariates were less likely to be employed and report high educational attainment and more likely to be underweight, be older, and indicate poor reported health status (p's ≤ 0.0001). Participant age ranged from 18 to 85 years, averaging 47.5 ± 0.25 and 48.5 ± 0.18 years for 2007 and 2012, respectively. In both years, study participants were predominantly white (72.2% and 69.5%, resp.), female (53.1% and 53.5%), and insured (84.3% and 84.2%); most (56.4% and 57.9%) reported they never smoked cigarettes. Excluding prayer, most participants had used at least one CHA before (69.8% and 68.8%), and a majority had also used natural products other than NVNMs (60.4% and 62.4%) (not shown). In both years, 35% were overweight (mean BMI = 27.4 ± 0.05 and 27.7 ± 0.04, for 2007 and 2012, resp.), and most (63% and 72%) reported at least one chronic health condition, with the number of chronic health conditions increasing from a mean of 1.5 ± 0.02 in 2007 to 1.9 ± 0.01 in 2012.

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of demographic and lifestyle characteristics, stratified by year and NVNM use in the past 12 months; medical-related/health characteristics are displayed in Table 2. The percentage of adults reporting NVNM use (ever) declined significantly between time points (p < 0.0001) from 27.1% of the sample population in 2007 (n = 5057) to 24.2% in 2012 (n = 7238; not shown). In contrast, the percentage of adults reporting use of NVNMs within the last 12 months (19.1% to 18.5%, resp.) and 30 days (13.9% in both years; not shown) remained approximately the same. Prevalence of diagnosed FMS also increased from 1.3% to 1.7% (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Consistent with a slight decrease in overall NVNM use among the general population, overall NVNM use among adults diagnosed with FMS declined from 57% in 2007 to 41% in 2012 (p < 0.0001). There were no apparent changes in the number of different combination NVNM supplements taken among those with FMS (mean (SE) for past 30 days = 0.99 (0.20) in 2007, 1.1 (0.38) in 2012, p = 0.89).

Table 1.

Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of 2007 and 2012 national US samples, stratified by NVNM use in the past 12 months, National Health Interview Survey.

| Characteristic | 2007 (N = 20,127) | p | 2012 (N = 30,672) | p | Overall pW | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVNM Use | NVNM Use | ||||||||||

| Yes | 95% CI | Weighted population estimate∗ | No | Yes | 95% CI | Weighted population estimate∗∗ | No | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||||||

| Total | 3582 (19.1) | (18.4, 19.8) | 16270972 | 16545 (80.9) | 5490 (18.5) | (17.8, 19.2) | 16713004 | 25182 (72.4) | <0.0001 | ||

| Age in years | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 269 (8.2) | (6.8, 9.6) | 1332833 | 1884 (11.7) | 391 (7.4) | (6.3, 8.4) | 1231081 | 2637 (11.1) | |||

| 25–44 | 1169 (31.9) | (30.1, 33.7) | 5193487 | 6195 (36.3) | 1775 (32.1) | (30.4, 33.7) | 5358304 | 8879 (34.1) | |||

| 45–64 | 1414 (39.8) | (37.9, 41.7) | 6476821 | 5314 (32.3) | 2162 (39.1) | (37.5, 40.8) | 6542615 | 8379 (33.1) | |||

| 65–75 | 462 (12.6) | (11.4, 13.7) | 2044193 | 1599 (9.5) | 741 (14.0) | (12.8, 15.1) | 2332396 | 2777 (11.4) | |||

| 75+ | 268 (7.5) | (6.5, 8.5) | 1223638 | 1553 (10.2) | 421 (7.5) | (6.6, 8.4) | 1248608 | 2510 (10.3) | |||

| Mean (SE) | 49.06 (0.35) | (48.38, 49.75) | 47.09 (0.27) | <0.0001 | 49.58 (0.33) | (48.93, 50.23) | 48.24 (0.19) | <0.0001 | 0.2794 | ||

| Sex | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Male | 1535 (43.2) | (41.3, 45.1) | 7028291 | 7644 (47.8) | 2341 (42.8) | (41.1, 44.5) | 7153927 | 11565 (47.3) | |||

| Female | 2047 (56.8) | (54.9, 58.7) | 9242681 | 8901 (52.2) | 3149 (57.2) | (55.5, 58.9) | 9559077 | 13617 (52.7) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2716 (82.9) | (81.7, 84.1) | 13487880 | 9419 (69.6) | 3979 (78.8) | (77.5, 80.1) | 13163299 | 14637 (67.4) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 329 (6.9) | (6.0, 7.8) | 1121133 | 2812 (13.5) | 513 (7.6) | (6.7, 8.4) | 1266927 | 4058 (13.3) | |||

| Hispanic | 360 (6.7) | (5.9, 7.5) | 1091895 | 3358 (12.8) | 622 (9.0) | (8.1, 9.8) | 1496127 | 4796 (14.4) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Asian | 99 (1.8) | (1.4, 2.2) | 297318 | 547 (2.3) | 196 (2.6) | (2.2, 3.0) | 438850 | 975 (2.9) | |||

| Other Race/ethnicity | 78 (1.7) | (1.3, 2.0) | 272746 | 409 (1.8) | 180 (2.1) | (1.7, 2.4) | 347801 | 716 (2.1) | |||

| Marital status | 0.088 | 0.009 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Married/ Cohabitating |

1903 (52.0) | (50.0, 53.9) | 8453944 | 8507 (51.4) | 2865 (52.1) | (50.2, 53.9) | 8703339 | 12354 (49.4) | |||

| Never married | 710 (21.0) | (19.2, 22.7) | 3411156 | 3800 (23.1) | 1206 (22.8) | (21.2, 24.4) | 3813588 | 6184 (24.7) | |||

| Divorced/sep/ widow |

969 (27.1) | (25.5, 28.7) | 4405872 | 4238 (25.6) | 1419 (25.1) | (23.7, 26.5) | 4196077 | 6644 (25.9) | |||

| Education | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| <12th grade | 272 (7.0) | (6.1, 7.8) | 1131795 | 3307 (16.5) | 417 (6.4) | (5.7, 7.2) | 1076502 | 4420 (15.1) | |||

| HS/GED | 808 (22.3) | (20.7, 23.8) | 3624376 | 4830 (29.6) | 1043 (18.4) | (17.2, 19.6) | 3078409 | 6860 (26.8) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Tech training/ some college |

1185 (33.4) | (31.6, 35.2) | 5436406 | 4527 (28.5) | 1924 (35.3) | (33.6, 36.9) | 5896361 | 7548 (30.7) | |||

| ≥Bachelor's degree | 1317 (37.4) | (35.4, 39.3) | 6078395 | 3881 (25.4) | 2106 (39.9) | (38.1, 41.6) | 6661732 | 6354 (27.4) | |||

| Employment | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Employed for pay | 2189 (61.6) | (59.8, 63.3) | 10016152 | 9818 (59.5) | 3301 (60.2) | (58.5, 61.9) | 10065089 | 13857 (55.4) | |||

| Employed but not for pay | 162 (4.8) | (4.0, 5.6) | 784425 | 465 (3.1) | 227 (4.3) | (3.7, 5.0) | 725979 | 703 (3.0) | |||

| Unemployed | 1231 (33.6) | (31.9, 35.3) | 5470395 | 6262 (37.4) | 1962 (35.4) | (33.7, 37.1) | 5921936 | 10622 (41.7) | |||

| Income | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| $1–$24,999 | 820 (23.4) | (21.8, 25.1) | 3809168 | 3710 (22.2) | 1186 (21.0) | (19.8, 22.3) | 3512363 | 5670 (21.6) | |||

| $25,000–$44,999 | 576 (15.7) | (14.3, 17.1) | 2553714 | 2545 (15.9) | 894 (16.3) | (15.1, 17.5) | 2727946 | 3675 (14.5) | |||

| $45,000–$74,999 | 478 (13.5) | (12.2, 14.9) | 2203952 | 1643 (10.6) | 803 (14.9) | (13.7, 16.0) | 2490180 | 2727 (11.5) | |||

| $75,000 and over | 341 (10.0) | (8.8, 11.1) | 1622926 | 858 (5.6) | 583 (11.4) | (10.4, 12.5) | 1912903 | 1683 (7.5) | |||

| Do not know | 129 (3.6) | (3.0, 4.2) | 578665 | 944 (5.3) | 189 (3.2) | (2.6, 3.8) | 538020 | 1103 (4.3) | |||

| Missing | 1238 (33.8) | (31.9, 35.7) | 5502547 | 6845 (40.4) | 1835 (33.1) | (31.6, 34.6) | 5531592 | 10324 (40.5) | |||

| Geographic location | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Northeast | 541 (15.5) | (13.8, 17.2) | 2526830 | 2783 (17.4) | 762 (13.9) | (12.5, 15.3) | 2324064 | 4325 (18.3) | |||

| Midwest | 850 (25.6) | (23.1, 28.1) | 4161206 | 3642 (25.0) | 1230 (26.2) | (24.2, 28.1) | 4374539 | 5173 (23.3) | |||

| South | 1190 (32.2) | (29.7, 34.7) | 5232720 | 6337 (37.8) | 1506 (29.2) | (26.8, 31.7) | 4886374 | 9683 (38.9) | |||

| West | 1001 (26.7) | (24.6, 28.9) | 4350216 | 3783 (19.8) | 1992 (30.7) | (28.6, 32.7) | 5128027 | 6001 (19.6) | |||

| Place of birth | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| US born | 3164 (91.0) | (90.1, 91.9) | 14807161 | 13116 (85.4) | <0.0001 | 4791 (89.8) | (88.9, 90.7) | 15010846 | 20112 (83.5) | <0.0001 | |

Note. Column percentages shown; ∗adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on 2000 Census data; ∗∗adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on 2010 Census data; ∗∗∗significant changes between 2007 and 2012 indicated by nonoverlapping weighted population confidence intervals; Wp values obtained by comparing weighted estimates; note: significant changes between datasets with differing weighting schemes indicated by nonoverlapping weighted population confidence intervals as ∗∗∗.

Table 2.

Medical care/health characteristics of 2007 and 2012 national US samples, stratified by NVNM use in the past 12 months, National Health Interview Survey.

| Characteristic | 2007 (N = 20,127) | p | 2012 (N = 30,672) | p | Overall pW | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVNM use | NVNM Use | ||||||||||

| Yes | 95% CI | Weighted population estimate∗ | No | Yes | 95% CI | Weighted population estimate∗∗ | No | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||||||

| Insurance status | |||||||||||

| Uninsured | 505 (13.4) | (12.4, 14.5) | 2185136 | 2999 (16.2) | <0.0001 | 790 (13.0) | (12.0, 13.9) | 2168607 | 4705 (16.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid | 155 (4.0) | (3.3, 4.6) | 645744 | 1510 (7.6) | <0.0001 | 287 (4.4) | (5.2, 10.5) | 735478 | 2736 (9.3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Medicare | 786 (21.6) | (20.0, 23.2) | 3519561 | 3466 (21.7) | 0.623 | 1277 (23.3) | (21.8, 24.8) | 3892141 | 5922 (23.9) | 0.451 | <0.0001 |

| Disability | 63 (2.0) | (1.3, 2.7) | 321398 | 165 (0.96) | <0.0001 | 111 (2.1) | (1.7, 2.5) | 346117 | 258 (1.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Private insurance | 2537 (72.6) | (70.9, 74.3) | 11813273 | 10211 (65.3) | <0.0001 | 3736 (70.2) | (68.7, 71.8) | 11739270 | 14238 (60.2) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Out of pocket costs, annual$ | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| None | 286 (7.8) | (6.8, 8.8) | 1272433 | 2155 (11.7) | 483 (8.1) | (7.3, 9.0) | 1358939 | 3811 (13.9) | |||

| <$500 | 1249 (35.0) | (33.3, 36.8) | 5700791 | 6719 (39.6) | 1780 (31.3) | (29.7, 32.9) | 5230362 | 9593 (37.3) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| $500–$1999 | 1236 (34.1) | (32.4, 35.8) | 5549126 | 4755 (29.5) | 1809 (33.8) | (32.4, 35.1) | 5641914 | 6938 (28.3) | |||

| $2000–$2999 | 333 (9.3) | (8.3, 10.3) | 1512573 | 1151 (7.7) | 554 (10.3) | (9.3, 11.3) | 1717635 | 2025 (8.7) | |||

| $3000–$4999 | 217 (6.2) | (5.3, 7.1) | 1008834 | 691 (4.5) | 420 (8.3) | (7.5, 9.1) | 1391128 | 1237 (5.1) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| $5000+ | 222 (6.4) | (5.6, 7.2) | 1039327 | 635 (4.1) | 396 (7.3) | (6.5, 8.1) | 1219938 | 1180 (5.1) | |||

| Do not know | 39 (1.2) | (0.74, 1.6) | 187888 | 439 (2.9) | 48 (0.9) | (0.63, 1.2) | 153088 | 398 (1.6) | |||

| Delayed care because they could not afford/worried about cost | 621 (17.6) | (16.2, 19.0) | 2867318 | 1947 (12.0) | <0.0001 | 964 (16.7) | (15.6, 17.9) | 2794500 | 3478 (13.2) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Perceived health status | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 3133 (87.7) | (86.6, 88.9) | 14272846 | 14162 (86.3) | 4849 (89.7) | (88.8, 90.6) | 14987051 | 21383 (86.2) | |||

| Fair | 363 (10.0) | (9.0, 11.1) | 1632026 | 1781 (10.1) | 505 (8.1) | (7.3, 8.9) | 1347889 | 2942 (10.7) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Poor | 86 (2.3) | (1.7, 2.8) | 366100 | 602 (3.6) | 136 (14.0) | (1.8, 2.7) | 378064 | 857 (86.0) | |||

| Physical activityR | |||||||||||

| None | 915 (24.6) | (22.9, 26.3) | 4001744 | 7428 (42.2) | <0.0001 | 1078 (18.9) | (17.7, 20.1) | 3158655 | 9136 (34.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Low/moderate | 2298 (65.3) | (63.3, 67.3) | 10629710 | 7504 (47.5) | <0.0001 | 3837 (70.8) | (69.5, 72.2) | 11841154 | 13429 (54.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| High | 1613 (46.5) | (44.5, 48.5) | 7571196 | 5164 (33.8) | <0.0001 | 2924 (54.7) | (53.0, 56.3) | 9136857 | 9817 (40.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Mean (SE) (weekly) (min) | 283.09 (10.23) | (262.96, 303.22) | 198.45 (6.00) | <0.0001 | 325.00 (9.77) | (305.77, 344.24) | 239.65 (4.63) | <0.0001 | 0.003 ∗∗∗ | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.016 | 0.031 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| <24.9 | 1384 (39.0) | (37.3, 40.8) | 6348273 | 6243 (38.7) | 2057 (38.6) | (37.0, 40.1) | 6448785 | 9039 (36.3) | |||

| 25–29.9 | 1246 (34.5) | (32.7, 36.2) | 5605830 | 5875 (35.4) | 1916 (34.4) | (32.9, 36.0) | 5757553 | 8717 (34.8) | |||

| 30–35 | 614 (17.2) | (15.8, 18.6) | 2793014 | 2731 (16.1) | 903 (16.3) | (15.1, 17.4) | 2718245 | 4425 (17.3) | |||

| 35+ | 338 (9.4) | (8.3, 10.5) | 1523855 | 1696 (9.9) | 614 (10.7) | (9.8, 11.6) | 1788421 | 3001 (11.6) | |||

| Mean (SE) | 27.37 (0.11) | (27.15, 27.60) | 27.35 (0.56) | 0.887 | 27.54 (0.09) | (27.36, 27.72) | 27.77 (0.05) | 0.024 | 0.2305 | ||

| Tobacco use | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Never | 1894 (51.2) | (49.2, 53.2) | 8330263 | 9977 (57.6) | 3114 (56.3) | (54.8, 57.9) | 9413789 | 14939 (58.3) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Former | 1067 (30.3) | (28.7, 31.9) | 4930987 | 3292 (21.2) | 1539 (28.6) | (27.3, 30.0) | 4788193 | 5281 (22.0) | |||

| Current | 621 (18.5) | (16.7, 20.3) | 3009722 | 3276 (21.2) | 837 (15.0) | (13.8, 16.2) | 2511022 | 4962 (19.6) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Alcohol use | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| None | 1006 (26.7) | (25.1, 28.4) | 4349888 | 6958 (39.0) | 1454 (24.0) | (22.5, 25.5) | 4012831 | 9897 (36.6) | |||

| Light | 1740 (47.9) | (46.1, 49.7) | 7794610 | 6609 (41.0) | 2662 (49.6) | (48.0, 51.3) | 8292892 | 10426 (42.7) | |||

| Moderate to heavy | 836 (25.4) | (23.6, 27.1) | 4126474 | 2978 (19.9) | 1374 (26.4) | (24.9, 27.9) | 15263475 | 4859 (20.7) | |||

| Substance abuse | 30 (0.81) | (0.52, 1.1) | 132414 | 96 (0.62) | 0.157 | 62 (1.3) | (0.89, 1.6) | 210988 | 164 (0.66) | 0.0003 | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidity indexa | |||||||||||

| None | 918 (25.6) | (23.9, 27.3) | 4164042 | 6532 (38.4) | <0.0001 | 1035 (18.7) | (17.5, 19.8) | 3117059 | 7588 (29.8) | <0.0001 | 0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| One | 912 (26.0) | (24.4, 27.5) | 4225414 | 3846 (23.7) | 1218 (22.3) | (20.9, 23.6) | 3721577 | 5717 (22.9) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Two | 662 (18.4) | (16.9, 19.8) | 2987313 | 2488 (15.5) | 1083 (19.6) | (18.4, 20.8) | 3272605 | 4243 (17.2) | |||

| ≥Three | 1090 (30.1) | (28.4, 31.7) | 4894203 | 3679 (22.4) | 2154 (39.5) | (37.8, 41.2) | 6601763 | 7634 (30.2) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Mean (SE) | 1.83 (0.03) | (1.77, 1.90) | 1.45 (0.02) | <0.0001 | 2.23 (0.03) | (2.17, 2.29) | 1.84 (0.02) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ | ||

| Chronic health conditions | |||||||||||

| Diabetes | 314 (8.2) | (7.2, 9.1) | 1331587 | 1633 (9.4) | 0.021 | 596 (10.2) | (9.3, 11.2) | 1709992 | 2965 (11.2) | 0.106 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Kidney disease | 57 (1.6) | (1.2, 2.1) | 263373 | 289 (1.6) | 0.713 | 91 (1.5) | (1.2, 1.8) | 250872 | 506 (1.9) | 0.047 | <0.0001 |

| GI diseaseaa | 590 (16.9) | (15.5, 18.3) | 2752405 | 1696 (10.8) | <0.0001 | 2186 (40.4) | (38.9, 41.9) | 6744109 | 7468 (29.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Chronic resp. conditionsb | 615 (16.9) | (15.6, 18.2) | 2745606 | 2144 (13.4) | <0.0001 | 985 (18.0) | (16.8, 19.3) | 3015703 | 3762 (15.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CVDc | 257 (7.0) | (6.1, 7.9) | 1142025 | 1078 (6.8) | 0.607 | 393 (7.1) | (6.3, 7.9) | 1186819 | 1829 (7.3) | 0.621 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1136 (31.1) | (29.4, 32.9) | 5064154 | 4764 (28.7) | 0.017 | 1856 (33.4) | (31.8, 35.0) | 5582424 | 8168 (32.2) | 0.165 | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1159 (32.2) | (30.5, 34.0) | 5246236 | 3977 (24.6) | <0.0001 | 1881 (33.9) | (32.2, 35.6) | 5659527 | 6628 (26.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 54 (1.5) | (1.1, 1.9) | 244387 | 198 (1.2) | 0.138 | 91 (1.6) | (1.2, 2.0) | 271510 | 348 (1.3) | 0.146 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic pain conditionsd | 1836 (51.6) | (49.8, 53.3) | 8390744 | 5940 (36.9) | <0.0001 | 3018 (55.2) | (53.9, 56.9) | 9263106 | 9943 (39.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Mental health conditionse | 832 (23.8) | (22.1, 25.6) | 3874783 | 2623 (16.0) | <0.0001 | 1674 (30.4) | (28.9, 31.9) | 5084683 | 5854 (22.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Insomnia | 948 (26.9) | (25.2, 28.7) | 4383811 | 2885 (17.8) | <0.0001 | 1488 (26.8) | (25.4, 28.2) | 4472612 | 4728 (18.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| History of cancer | 355 (10.1) | (9.0, 11.2) | 1638188 | 1101 (7.4) | <0.0001 | 569 (10.7) | (9.7, 11.7) | 1792043 | 2039 (8.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Use of other complementary health approaches | 3539 (98.9) | (98.6, 99.3) | 16094998 | 14150 (86.2) | <0.0001 | 5357 (97.9) | (97.5, 98.4) | 16369136 | 17689 (72.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Other natural productsf | 3331 (93.4) | (92.4, 94.4) | 15192940 | 10243 (64.4) | <0.0001 | 5215 (95.5) | (94.9, 96.2) | 15965914 | 15806 (64.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Mind-bodyg | 1870 (53.2) | (51.5, 55.0) | 8659604 | 3621 (23.6) | <0.0001 | 2094 (39.7) | (38.0, 41.4) | 6633294 | 3290 (13.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Manipulative/ bodyworkh |

2034 (58.4) | (56.5, 60.3) | 9496114 | 4144 (27.1) | <0.0001 | 2783 (51.7) | (50.0, 53.4) | 8634942 | 6075 (25.3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Energy healing/Reiki | 218 (6.1) | (5.2, 7.0) | 997157 | 137 (0.89) | <0.0001 | 240 (4.5) | (3.8, 5.1) | 747014 | 123 (0.47) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| spiritual practicesi | 2334 (64.6) | (62.7, 66.5) | 10512222 | 9637 (56.5) | <0.0001 | 643 (12.5) | (11.4, 13.5) | 2081886 | 718 (2.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

| Alternative systemsk | 858 (23.8) | (22.1, 25.5) | 3867268 | 1136 (6.9) | <0.0001 | 1037 (19.0) | (17.8, 20.2) | 3180077 | 1231 (4.9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ |

Note. Column percentages shown; ∗adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on 2000 Census data; ∗∗adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on 2010 Census data; ∗∗∗significant changes between 2007 and 2012 indicated by nonoverlapping weighted population confidence intervals; Wp values obtained by comparing weighted estimates; note: significant changes between datasets with differing weighting schemes indicated by nonoverlapping weighted population confidence intervals as ∗∗∗; $family costs aside from deductibles, premiums, copays; Rdefined as ≥10 min. increments; aincluding diabetes, kidney disease, gastrointestinal disorder (including ulcer and/or abdominal pain, digestive allergy, and heartburn), respiratory conditions (asthma, emphysema, and/or chronic bronchitis), dyslipidemia, liver condition, rheumatoid arthritis, CVD, hypertension, nonspecific arthritis, gout, migraines, mental health condition; aaincluding bowel conditions and ulcers (2007); past 12 months: abdominal pain, digestive allergy, heartburn, and ever having ulcer (2012); basthma, emphysema, and/or chronic bronchitis; cmyocardial infarction, heart disease, angina pectoris; dmigraines (past 3 months), nonspecific arthritis, gout, nonspecific joint pain for 3+ months, rheumatoid arthritis; edepression, bipolar disorder, phobias, often anxious (past year); fsupplements other than NVNMs, including vitamins/minerals, probiotics (past 30 days), fish oil (past 30 days), chelation therapies; gTai Chi/Qi Gong, yoga, guided imagery, progressive relaxation, deep breathing exercises, meditation (singular term “meditation” used in 2007; expanded in 2012 to include mantra and mindfulness meditation), mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive therapy (2012), stress-management class (2007), biofeedback, hypnosis; hpractitioner-based massage (ever), chiropractic/osteopathic manipulation, Sobador visit; iprayed for one's own health (2007) or centering prayer/contemplative meditation (2012); and/or visit with Espiritista (2007 only), Curandero, Shaman, and/or native American healer; kacupuncture, Ayurveda, homeopathy, and naturopathy.

Table 3.

NVNM use in two nationally representative samples of adults with diagnosed fibromyalgia, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS 2007 N = 221 (1.3%∗C1) versus NHIS 2012 N = 524 (1.7%∗∗C2)).

| Characteristic | 2007 | 2012 | Overall pW | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 95% CI | Weighted population estimate∗ | N (%) | 95% CI | Weighted population estimate∗∗ | ||

| NVNM use ever | <0.0001 ∗∗∗ | ||||||

| Yes | 114 (57.1) | (49.3, 64.9) | 624881 | 204 (40.6) | (35.3, 45.8) | 633029 | |

| No | 107 (42.9) | (35.1, 50.7) | 469162 | 320 (59.4) | (54.2, 64.7) | 927192 | |

| NVNM use in past 12 months | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 82 (41.7) | (33.3, 50.2) | 456477 | 157 (31.2) | (26.1, 36.4) | 487362 | |

| No | 139 (58.3) | (49.8, 66.7) | 637566 | 367 (68.8) | (63.6, 73.9) | 1072859 | |

| NVNM use in past 30 days | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 62 (32.7) | (24.6, 40.9) | 358265 | 126 (24.5) | (19.9, 29.1) | 382285 | |

| No | 159 (67.3) | (59.1, 75.4) | 735778 | 398 (75.5) | (70.9, 80.1) | 1177936 | |

| Number of different NVNM supps in past 30 daystt | |||||||

| (Mean (SE)) | 0.99 (0.20) | (0.60, 1.4) | 1.07 (0.38) | (0.32, 1.8) | 0.894 | ||

| Physician disclosure of NVNMd | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 50 (64.6) | (53.1, 76.1) | 294988 | 51 (71.4) | (59.0, 83.9) | 140681 | |

| No | 32 (35.4) | (23.9, 46.9) | 161489 | 15 (28.6) | (16.1, 41.0) | 56221 | |

Note. Total sample with fibromyalgia is percentage denominator; ∗adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on 2000 Census data; ∗∗adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity based on 2010 Census data; ∗ ∗∗significant changes between 2007 and 2012 indicated by nonoverlapping weighted population confidence intervals; Wp values obtained by comparing weighted estimates; note: significant changes between datasets with differing weighting schemes indicated by nonoverlapping weighted population confidence intervals as ∗∗∗; ttamong NVNM users with fibromyalgia; including combination NVNM supplement; dwithin past 30 days (N = 66; 2007); only disclosure of top therapy assessed within past 12 months (2012); C1(95% CI: 1.1, 1.5); C2(95% CI: 1.6, 1.9).

Between 2007 and 2012, rates of NVNM consumption (past 12 months; Table 1) declined among non-Hispanic White adults (83% to 79%) but increased among those identified as Hispanic (7% to 9%; p's < 0.0001). Overall, the likelihood of NVNM use significantly increased by number of health conditions in both years (Table 2; p's for trend ≤ 0.0001, not shown). In addition, NVNM users (past 12 months) spending under $500 in out-of-pocket medical costs decreased (2007 and 2012: 35.0% and 31.3%, resp.) while NVNM users spending over $3,000 increased (6.2% and 8.3%). This was also noted by an increase in likelihood of NVNM use by out-of-pocket costs for both years (p's for trend = 0.0001; not shown). Lastly, consumption of other natural products (i.e., vitamins/minerals) increased (93% to 96%) among all herbal users between time points.

3.1. Relation of FMS to Herbal Use

Nearly 60% of those with FMS reported previous or current NVNM use; 42% indicated using NVNMs in the past 12 months, and 33% in the past 30 days (Table 3). Approximately 3% of all NVNM users had FMS; this rate did not differ between years (Table 4). In 2007, participants with FMS were 3.7 times as likely as those without FMS to use NVNMs for any length of time (OR = 3.7, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.7, 5.0). After adjustment for demographic, lifestyle, and medical/health factors, those with FMS were 2.7 times as likely to report ever using NVNMs than those without FMS (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.7, (CI: 1.9, 3.8)). FMS showed a similarly strong positive association to recent NVNM use (12-month and 30-day AORs = 2.3 (CI: 1.5, 3.4) and 2.3 (CI: 1.6, 3.5), resp.). Likewise, FMS was significantly and positively associated with all NVNM use outcomes in 2012, although the magnitude of the associations was lower (2012 AORs: herbal use (ever) = 1.6 (CI: 1.3, 2.0); 12 months = 1.6 (CI: 1.2, 2.0); 30 days = 1.5 (CI: 1.2, 2.0)).

Table 4.

Association of NVNM use to self-reported fibromyalgia diagnosis in two nationally representative samples of adults, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS 2007, N = 20,127; and 2012, N = 30,672).

| N (%) | 95% CI | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p | Odds ratio adjusted for demographics and related factors∗ (95% CI) | p | Odds ratio adjusted for demographics, lifestyle, and related factors¥ (95% CI) | p | Odds ratio adjusted for demographics, lifestyle, and related factors + comorbidityt (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHIS 2007 | ||||||||||

| NVNM use in the last 30 days | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 62 (3.0) | (2.1, 3.9) | 3.07 (2.12, 4.45) | <0.0001 | 2.36 (1.59, 3.51) | <0.0001 | 2.54 (1.69, 3.83) | <0.0001 | 2.34 (1.55, 3.52) | <0.0001 |

| No | 2561 (97.0) | (96.1, 97.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| NVNM use in the last 12 months | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 82 (2.8) | (2.0, 3.6) | 3.09 (2.19, 4.37) | <0.0001 | 2.34 (1.58, 3.47) | <0.0001 | 2.48 (1.67, 3.71) | <0.0001 | 2.25 (1.51, 3.35) | <0.0001 |

| No | 3500 (97.2) | (96.4, 98.0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| NVNM use ever | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 114 (2.7) | (2.1, 3.3) | 3.66 (2.66, 5.03) | <0.0001 | 2.85 (2.02, 4.02) | <0.0001 | 3.01 (2.13, 4.25) | <0.0001 | 2.66 (1.85, 3.82) | <0.0001 |

| No | 4943 (97.3) | (96.7, 97.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| NHIS 2012 | ||||||||||

| NVNM use in the last 30 days | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 126 (3.0) | (2.4, 3.6) | 2.04 (1.59, 2.61) | <0.0001 | 1.65 (1.27, 2.14) | 0.0002 | 1.72 (1.33, 2.24) | <0.0001 | 1.51 (1.15, 2.00) | 0.003 |

| No | 3994 (97.0) | (96.4, 97.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| NVNM use in the last 12 months | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 157 (2.9) | (2.4, 3.4) | 2.03 (1.62, 2.56) | <0.0001 | 1.72 (1.34, 2.20) | <0.0001 | 1.82 (1.42, 2.33) | <0.0001 | 1.57 (1.21, 2.04) | 0.0007 |

| No | 5333 (97.1) | (96.6, 97.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| NVNM use ever | ||||||||||

| Fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 204 (2.9) | (2.4, 3.3) | 2.17 (1.75, 2.69) | <0.0001 | 1.84 (1.47, 2.32) | <0.0001 | 1.92 (1.52, 2.42) | <0.0001 | 1.59 (1.25, 2.03) | 0.0002 |

| No | 7034 (97.1) | (96.7, 97.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

Boldface indicates statistical significance at p ≤ 0.05; ∗adjusted for age, sex, race, education, employment, income, geographic location of birth, insurance status (Medicaid, disability, and private), out-of-pocket medical expenses, delayed access to care due to cost, and region (2007); additionally, marital status (2012); ¥additionally adjusted for smoking status, alcohol use, exercise, and BMI (2007); and substance abuse (2012); thealth conditions include diabetes, kidney disease, gastrointestinal disorder (including ulcer), respiratory conditions, dyslipidemia, liver condition, rheumatoid arthritis, CVD, hypertension, arthritis, gout, migraines, and mental health condition; and self-reported health status.

The magnitude of the association of NVNM use to FMS was significantly greater in those with 0-1 comorbid health conditions than in those with 2 or more health conditions (age-adjusted ORs, resp., = 4.7 (CI: 2.2, 9.8) versus 2.8 (CI: 2.0, 3.9; p for interaction = 0.008) in 2007; not shown). However, we found no evidence of a modifying effect of multiple comorbidities in 2012 or for gender in either year.

To our knowledge, this is the first large, population-based study to examine the relation of NVNM use to FMS; it is also among the first rigorous studies to investigate the relation of NVNM use to any chronic pain condition in a large sample [25, 29, 30, 36]. Relative to adults without FMS, those with FMS were significantly more likely to report using NVNMs at any time point (within the past 30 days or 12 months or ever) in both 2007 and 2012 survey years; the positive association of FMS to NVNM use remained highly significant even after controlling for a broad array of demographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors.

In our study, the majority of those with FMS indicated using NVNMs at some time point; one-third had used NVNMs in the past 30 days. Previous studies assessing herbal use in FMS reported widely varying rates among FMS patients, ranging from 43% (FMS = 434) to 78% (FMS = 90) [36, 37]. Reported rates among other chronic pain populations have been considerably lower, ranging from 6.8% in a sample of primary care patients using opioids [29] to 15% in a primary care patient population with chronic pain [30]. However, percentages given in prior studies were unweighted and may in part reflect differences in study populations and outcome definitions, rendering comparison with our findings challenging.

Prevalence of diagnosed FMS increased between 2007 and 2012 (1.3% to 1.7%). Despite lower rates than those appearing globally and in some US studies [1–3], this apparent rise in diagnosed FMS may be due in part to increased recognition of FMS by physicians following publication of the 2010 Preliminary ACR updated criteria for fibromyalgia.

In contrast, we found reported NVNM use among adults with FMS declined significantly from 2007 to 2012, paralleling the modest but significant reduction in overall NVNM use observed between these periods. However, the mean number of different combination NVNM supplements used by those with FMS did not differ between time points and averaged lower than that reported in a case-control study of North American women (N = 434 with FMS) [36]. In addition, both the observed decline in NVNM use among those with FMS and the positive but more modest association between NVNM use and FMS in 2012 compared to 2007 may also reflect increased availability of FDA-approved FMS medications following the 2007 NHIS survey administration. It also remains possible that both the increase in FMS diagnoses and decrease in odds of NVNM use for FMS over time are also in part the result of promotion for FMS drugs by pharmaceutical companies [38] and increased off-label prescription of other drugs for FMS, potentially including opioids [39, 40].

Strengths and Limitations. This investigation was the first study to assess the relation between NVNM use and FMS in a large US population. Strengths of our study include large, nationally representative samples, use of data from two time periods, and the availability of comprehensive information on NVNM use, as well as a broad array of demographic, lifestyle, health-related, and other potentially confounding factors. However, there were some limitations. Perhaps most important, the cross-sectional study design precluded determination of causal relationships. Ascertainment of NVNM use and medical history, including diagnosis of FMS, was reliant on self-report, raising the possibility of recall bias; however, potential underascertainment would likely bias our results toward the null, indicating more conservative estimates.

Although the NVNM use outcome mainly comprised of herbal dietary supplements and was assessed separately from many other nonherbal supplements in both NHIS data collection periods, the nonherbal products coenzyme Q-10, SAM-e, fish oil, and prebiotics/probiotics were included in our main NVNM outcome. Thus, our consideration of a broader NVNM outcome may be more appropriate than a specific herbal supplement use outcome, since reports of individual ingredients were not consistently available between years. There was inadequate capture of certain herbal products within the NVNM outcome. No data were available on consumption of herbal and green teas used for health purposes or on products not labelled (per NHIS requirements for inclusion) “dietary supplement,” including home grown herbs, traditionally prepared herbal products, and bulk herbs/powders sometimes recommended (i.e., by nutritionists, natural foods purveyors) over widely available supplements due to quality and processing concerns. We did not have information on FMS severity or duration, and although the 2012 questionnaire differed from 2007, there were no differences with respect to assessment of fibromyalgia. Based on cognitive testing and input from expert panels, the definitions of certain modalities were modified in 2012 to reduce false-positive responses [34] which may have affected findings. However, these changes were relatively minor and were unlikely to affect our estimates, as these potential false-positives did not vary by disease status.

Given the high prevalence rates of those with FMS using NVNMs, and the strong, positive relationship of FMS to NVNM use which persisted in 2012 despite the availability of approved treatments, additional prospective research is warranted to confirm these findings, to further investigate the prevalence, patterns, and determinants of specific NVNM use in FMS, and to explore the safety and potential efficacy of NVNM products for this still poorly managed condition.

4. Conclusions

In the first large cross-sectional study of two nationally representative samples of US adults, reported diagnosis of FMS was strongly and positively associated with NVNM use in both 2007 and 2012 after adjustment for demographic, lifestyle, and health factors. Rigorous prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and to further explore the patterns, determinants, and potential efficacy of NVNM use in those with FMS.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by NIH NIGMS Grant T32 GM081741. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Dina Jones for feedback on earlier iterations of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Queiroz L. P. Worldwide epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2013;17, article 356(8) doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walitt B., Nahin R. L., Katz R. S., Bergman M. J., Wolfe F. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the 2012 national health interview survey. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138024.0138024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent A., Lahr B. D., Wolfe F., et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, utilizing the Rochester epidemiology project. Arthritis Care and Research. 2013;65(5):786–792. doi: 10.1002/acr.21896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clauw D. J. Fibromyalgia and related conditions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(5):680–692. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staud R. Evidence for shared pain mechanisms in osteoarthritis, low back pain, and fibromyalgia. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2011;13(6):513–520. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacomelli C., Talarico R., Bombardieri S., Bazzichi L. The interaction between autoimmune diseases and fibromyalgia: Risk, disease course and management. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2013;9(11):1069–1076. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2013.849440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe F., Michaud K., Li T., Katz R. S. Chronic conditions and health problems in rheumatic diseases: comparisons with rheumatoid arthritis, noninflammatory rheumatic disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and fibromyalgia. Journal of Rheumatology. 2010;37(2):305–315. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haviland M. G., Banta J. E., Przekop P. Fibromyalgia: prevalence, course, and co-morbidities in hospitalized patients in the United States, 1999-2007. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2011;29(6):S79–S87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang T.-Y., Chen C.-S., Lin C.-L., Lin W.-M., Kuo C.-N., Kao C.-H. Risk for irritable bowel syndrome in fibromyalgia patients a national database study. Medicine (United States) 2015;94(10, article no. e616) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tietjen G. E., Brandes J. L., Peterlin B. L., et al. Allodynia in migraine: Association with comorbid pain conditions. Headache. 2009;49(9):1333–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett R. M., Jones J., Turk D. C., Russell I. J., Matallana L. An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2007;8, article 27 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NIH. Questions and Answers about Fibromyalgia. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases 2014. Available from: http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Fibromyalgia/default.asp.

- 13.Wolfe F., Clauw D. J., Fitzcharles M. A., et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2011;38(6):1113–1122. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaskell H., Moore R. A., Derry S., Stannard C. Oxycodone for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;6:p. CD010692. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010692.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Painter J. T., Crofford L. J. Chronic opioid use in fibromyalgia syndrome: A clinical review. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2013;19(2):72–77. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182863447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. CDC. Drug-poisoning Deaths Involving Opioid Analgesics: United States, 1999–2011. NCHS Data Brief 2014. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db166.htm. [PubMed]

- 17.Rudd R. A., Seth P., David F., Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010-2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(5051):1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y., Sun P., Watson P., Mitchell B., Swindle R. Comparison of Medication Adherence and Healthcare Costs between Duloxetine and Pregabalin Initiators among Patients with Fibromyalgia. Pain Practice. 2011;11(3):204–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macfarlane G. J., Kronisch C., Dean L. E., et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76(2):318–328. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanza F. L., Chan F. K. L., Quigley E. M. M. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(3):728–738. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Häuser W., Walitt B., Fitzcharles M. A., Sommer C. Review of pharmacological therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2014;16(1):p. 201. doi: 10.1186/ar4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roskell N. S., Beard S. M., Zhao Y., Le T. K. A meta-analysis of pain response in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Practice. 2011;11(6):516–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. NIH. Pain: Considering Complementary Approaches (eBook). Available from: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/pain/ebook, 2016.

- 24.Nahin R. L., Stussman B. J., Herman P. M. Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures on Complementary Health Approaches Associated with Painful Health Conditions in a Nationally Representative Adult Sample. Journal of Pain. 2015;16(11):1147–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke T. C., Nahin R. L., Barnes P. M., Stussman B. J. Use of complementary health approaches for musculoskeletal pain disorders among adults: United States, 2012. National Health Statistics Reports. 2016;(98) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes P. M., Bloom B., Nahin R. L. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. National Health Statistics Reports. 2008;2008(12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ernst E. Oxford Handbook of Complementary Medicine (Oxford Medical Handbooks) Oxford, New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoonees A., Visser J., Musekiwa A., Volmink J. Pycnogenol® (extract of French maritime pine bark) for the treatment of chronic disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008294.pub4.CD008294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleming S., Rabago D. P., Mundt M. P., Fleming M. F. CAM therapies among primary care patients using opioid therapy for chronic pain. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;7, article no. 15 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg E. I., Genao I., Chen I., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Medicine. 2008;9(8):1065–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabrera C. Fibromyalgia: A Journey Toward Healing. Chicago, USA: Contemporary Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32. CDC, 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release. 2013, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, Maryland.

- 33.Ursini F., Naty S., Grembiale R. D. Fibromyalgia and obesity: The hidden link. Rheumatology International. 2011;31(11):1403–1408. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1885-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. CDC, Variance Estimation Guidance, NHIS 2006-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics, 2016.

- 35. NIH. Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risks. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmi_dis.htm, 2015.

- 36.Shaver J. L., Wilbur J., Lee H., Robinson F. P., Wang E. Self-reported medication and herb/supplement use by women with and without fibromyalgia. Journal of Women's Health. 2009;18(5):709–716. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimmock S., Troughton P. R., Bird H. A. Factors predisposing to the resort of complementary therapies in patients with fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology. 1996;15(5):478–482. doi: 10.1007/BF02229645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faerber A. E., Kreling D. H. Content analysis of false and misleading claims in television advertising for prescription and nonprescription drugs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29(1):110–118. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2604-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dowell D., Haegerich T. M., Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Zee A. The promotion and marketing of oxycontin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(2):221–227. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2007.131714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]