Abstract

In northern Western Australia in 2011 and 2012, surveillance detected a novel arbovirus in mosquitoes. Genetic and phenotypic analyses confirmed that the new flavivirus, named Fitzroy River virus, is related to Sepik virus and Wesselsbron virus, in the yellow fever virus group. Most (81%) isolates came from Aedes normanensis mosquitoes, providing circumstantial evidence of the probable vector. In cell culture, Fitzroy River virus replicated in mosquito (C6/36), mammalian (Vero, PSEK, and BSR), and avian (DF-1) cells. It also infected intraperitoneally inoculated weanling mice and caused mild clinical disease in 3 intracranially inoculated mice. Specific neutralizing antibodies were detected in sentinel horses (12.6%), cattle (6.6%), and chickens (0.5%) in the Northern Territory of Australia and in a subset of humans (0.8%) from northern Western Australia.

Keywords: novel flavivirus, Fitzroy River virus, arbovirus, Aedes normanensis, yellow fever virus group, whole-genome sequencing, viruses, Australia, United States

In the state of Western Australia, Australia, active surveillance is conducted for mosquitoborne viruses of major human health significance: alphaviruses Ross River virus (RRV) and Barmah Forest virus (BFV) and flaviviruses Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV) and West Nile virus (subtype Kunjin virus; KUNV). These flaviviruses are endemic and epidemic to the northern and central areas of Australia, where surveillance involves year-round testing for seroconversions in sentinel chickens (1) and virus isolation from mosquito pools collected annually (2,3). More frequent mosquito collection is prevented by the logistical difficulties of accessing remote areas. Commonly isolated arboviruses include the flaviviruses MVEV (and subtype Alfuy virus), KUNV, Kokobera virus (KOKV), and Edge Hill virus (EHV) and the alphaviruses RRV, BFV, and Sindbis virus (4,5). This system occasionally detects viruses that cannot be identified as known viruses, such as Stretch Lagoon virus, an orbivirus isolated in 2002 (6). We describe the detection and characterization of a novel flavivirus named Fitzroy River virus (FRV), isolated from mosquitoes collected in northern Western Australia, and seroepidemiologic evidence of human or animal infection.

Methods

Adult Mosquito Collections

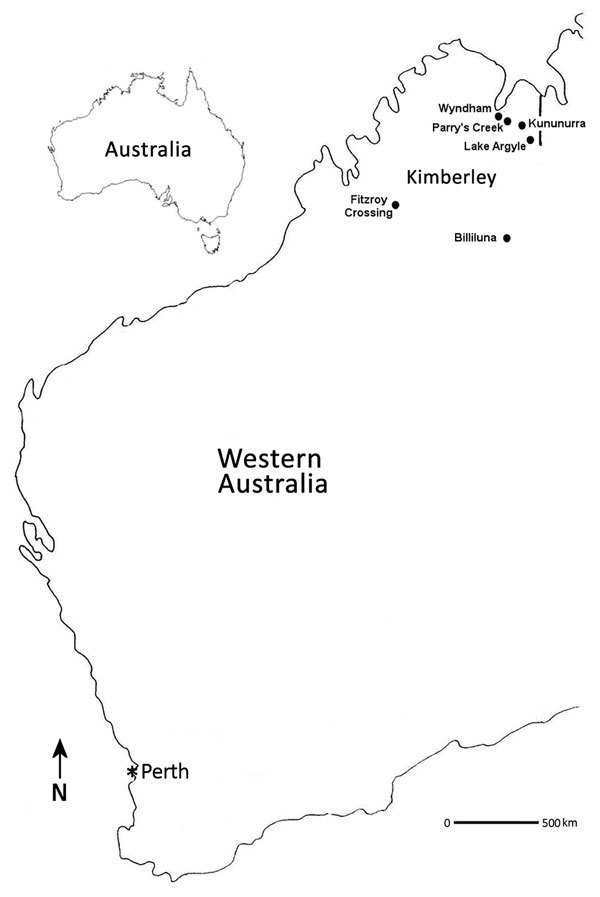

Adult mosquitoes were collected during March and April 2010–2015, at the end of the summer wet season across the Kimberley region of Australia (2) (Figure 1). Mosquitoes were collected in encephalitis vector surveillance traps (7) baited with carbon dioxide and were separated by species and pooled (8–10); blood-fed mosquitoes were excluded from analysis.

Figure 1.

Locations where Fitzroy River virus–positive mosquitoes were collected (black dots), Western Australia, Australia, 2011 and 2012. Perth (asterisk), the capital city and most densely populated area of Western Australia, is shown to indicate its distance from the Kimberley region.

Virus Isolation and Identification

Virus isolation from all mosquito pools was performed as previously described (10). In brief, mosquito pools were homogenized and serially passaged from C6/36 (Aedes albopictus mosquito) cells onto Vero (African green monkey kidney) and PSEK (porcine squamous equine kidney) cells. PSEK cells were later replaced by BSR (baby hamster kidney) cells. Viruses were detected and identified by use of microscopy and monoclonal antibody (mAb) binding patterns in ELISA. For flavivirus-reactive samples, a flavivirus group–reactive 1-step reverse transcription PCR assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (11) was used to amplify a 0.6-kb fragment of the nonstructural protein 5 (NS5) and 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) for PCR and sequence confirmation.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

RNA from viral stock (the prototype isolate K73884) was extracted with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) and sequenced on a HiSeq ultra high–throughput sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Trimmed reads were assessed for quality by using PRINSEQ version 0.20.2 (12) before host (metazoan and mosquito) genome subtraction (Bowtie 2) (13) and assembly (MIRA version 4.0) (14). Resulting contiguous sequences and unique singletons were subjected to homology search by using MegaBLAST and blastx (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against the GenBank database. Sequences that were similar to viruses from the yellow fever virus (YFV) group, a monophyletic branch that previously included 3 viruses (Wesselsbron virus [WESSV], Sepik virus [SEPV], and YFV) (15) were manually edited and reassembled by using Geneious version 7.1.5 (16). The complete genome was resequenced by using overlapping PCR and confirmed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing. The sequences for the 5′ and 3′ UTRs were acquired by using the SMARTer RACE cDNA amplification kit (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Phylogenetic and Recombination Analyses

Nucleotide sequences for the complete polyproteins representing 44 mosquitoborne and tickborne flaviviruses, as well as those that are insect specific or have no known vector, were retrieved from GenBank. Alignments with FRV were performed by using MUSCLE in Geneious version 7.1.5, and a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the general time reversible plus gamma distribution site model of nucleotide substitution with 500 bootstrap replicates (MEGA version 7.0.16) (17). Tamana bat virus was used as the outgroup. For alignments of cleavage recognition sequences from members of the YFV group, previously established sites were identified and aligned (18,19). To assess whether FRV was a recombinant virus, we analyzed polyprotein sequence alignments (as described above) by using default parameters for RDP, GENECONV, BootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SisScan, 3SEQ, and Phylpro methods available in the RDP4 program suite (20).

Virus Growth Kinetics in Vitro

Virus replication was assessed in mosquito (C6/36), mammalian (Vero and BSR), and avian (DF-1) cells (21) by using a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 in 2% fetal bovine serum in M199 (C6/36 cells) or DMEM (Vero, BSR, and DF-1 cells). After 1 hour of incubation at 28°C (C6/36 cells) or 37°C (Vero, BSR, and DF-1 cells), the inoculum was removed and monolayers were washed before addition of 1 mL of media. Plates were incubated; monolayers examined for cytopathic effect (CPE); and samples removed in triplicate at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 days postinoculation (dpi) and stored at −80°C. The 50% tissue culture infectious dose in each sample was determined by serial dilutions and titration in BSR cells in 96-well tissue culture plates, and titers were calculated (22).

Determination of Virulence in Mice

All procedures using animals were approved by The University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee. Groups of 10 mice (18–19 day weanling CD1 mice, equal numbers of each sex) were challenged by intraperitoneal injection of 50 μL or intracranial injection of 20 μL of either 100 or 1,000 50% tissue culture dose infectious units (IU) of FRV. Groups of 3 mice were mock challenged intraperitoneally or intracranially. Veterinarians monitored the mice twice daily for 19 days and then daily through 21 dpi (23,24). At 21 dpi, all mice were deeply anesthetized, bled by cardiac puncture, and killed by cervical dislocation. No animals required euthanasia during the experiment. FRV-specific antibodies were detected by fixed-cell ELISA (25), and the brains of mice with mild clinical signs were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formaldehyde and processed for histopathologic and immunohistochemical examination (23,24).

Serologic Surveys

Human serologic studies were performed with approval from The University of Western Australia Human Ethics Committee. We used human serum samples that were submitted to PathWest Laboratory Medicine WA (Nedlands, Western Australia, Australia) for arbovirus serologic testing and that were positive by flavivirus hemagglutination inhibition assay. We also used serum samples that were submitted for alphavirus testing only (RRV and BFV) and that were serologically negative. Deidentified information about patient age, sex, ZIP code, and test results were provided. Samples from residents of regions in northern Western Australia where FRV had been detected in mosquitoes or where Aedes normanensis mosquitoes are abundant were targeted for this survey. Samples were tested in a flavivirus epitope blocking ELISA that used mAb 3H6 (26). Serum containing flavivirus antibodies in ELISA were subsequently tested by serum cross-neutralization assay for antibodies to FRV, MVEV, KUNV, Alfuy virus, KOKV, Stratford virus, and EHV as described previously (27). As controls, we used polyclonal rabbit or mouse serum previously raised to these viruses.

Animal serologic studies were approved by The Charles Darwin University Animal Ethics Committee. Animal serum (sentinel cattle, horses, chickens, and wallabies) from the Northern Territory of Australia was tested for antibodies to FRV by neutralization tests (28) without prior testing by flavivirus epitope blocking ELISA. Cross-neutralizations with SEPV were conducted on a subset of positive samples to confirm antibody specificity.

Results

Viruses and mAb Binding Patterns

We saw little or no visual evidence of infection of C6/36 cell monolayers during the isolation of FRV, and it grew slowly in Vero cells. Cytopathic evidence of infection was most marked in PSEK and BSR cells. Isolates were initially typed by their mAb binding profile against a panel of flavivirus- and alphavirus-reactive mAbs in fixed-cell ELISA. All isolates of FRV reacted with the flavivirus-reactive mAb 4G2 but failed to react with other flavivirus- and alphavirus-reactive mAbs (data not shown). Preliminary analyses of the nucleotide sequence of the NS5–3′ UTR showed 75%–80% identity to SEPV and WESSV, the viruses most closely related to YFV (15,19,29,30). Identity between all FRV isolates in the NS5–3′ UTR was 98.9%–100%. The mAb binding profile differed from EHV and SEPV, and positive reactions to FRV were detected with mAbs 4G2 and 4G4 only (Table 1).

Table 1. Monoclonal antibody binding pattern of FRV isolates from Western Australia*.

| Virus |

Monoclonal antibody† |

||||||||||

| 4G2 |

4G4 |

6F7 |

7C6 |

8G2 |

6A9 |

3D11 |

3B11 |

3G1 |

5D3 |

7C3 |

|

| FRV‡ | + | + | - | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SEPV | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| YFV | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EHV | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

*EHV, Edge Hill virus; FRV, Fitzroy River virus; SEPV, Sepik virus; YFV, yellow fever virus; +, positive (optical density of >0.2 and at least 2 times the mean of negative control wells); –, negative. †Original descriptions of monoclonal antibody from (31) (4G2), (32) (4G4), (33) (6F7), and (34) (7C6, 8G2, 6A9, 3D11, 3B11, 3G1, 5D3, and 7C3). ‡Monoclonal antibody binding patterns of all FRV isolates were identical to those of the prototype isolate K73884.

Whole-Genome Sequences and Phylogeny

Unbiased high-throughput sequencing results provided >99% of the FRV genome with only partial UTRs not obtained. The completed full-genome length of FRV was 10,807 nt with a single 10,218-nt open reading frame flanked by a 117-nt 5′ UTR and a 472-nt 3′ UTR (Table 2; Technical Appendix Figure, panel A) and has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. KM 361634. At the amino acid level, FRV was more similar to SEPV than to WESSV in most regions, with the exception of the short 2k peptide (70% vs. 91% aa homology), NS4a (87% vs. 92% aa homology), and NS5 (88% vs. 89% aa homology). Because there was a sharp change in amino acid homology between FRV and SEPV across the 2k peptide (70%) and NS4b (94%), we assessed aligned polyprotein sequences for recombination breakpoints by using 8 algorithms in the RDP4 suite, but we found no evidence suggesting that recombination had occurred (data not shown).

Table 2. Comparison of genomic region lengths and similarities between members of the YFV group and FRV*.

| Genomic region |

Virus |

| FRV |

|

SEPV |

|

WESSV |

|

YFV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nt |

aa |

nt |

aa |

nt |

aa |

nt |

aa |

||||

| 5′ UTR | 117 | NA | 116 (94) | NA | 118 (92) | NA | 118 (52) | NA | |||

| Capsid | 348 | 116 | 348 (77) | 116 (84) | 348 (74) | 116 (78) | 363 (54) | 121 (39) | |||

| Premembrane | 267 | 89 | 267 (78) | 89 (94) | 267 (73) | 89 (87) | 267 (59) | 89 (59) | |||

| Membrane | 225 | 75 | 225 (80) | 75 (96) | 225 (74) | 75 (87) | 225 (58) | 75 (47) | |||

| Envelope | 1,470 | 490 | 1,470 (81) | 490 (96) | 1,470 (79) | 490 (93) | 1,479 (63) | 493 (54) | |||

| NS1 | 1,059 | 353 | 1,059 (79) | 353 (93) | 1,059 (76) | 353 (87) | 1,056 (63) | 352 (64) | |||

| NS2a | 678 | 226 | 678 (78) | 226 (88) | 678 (77) | 226 (85) | 672 (54) | 224 (40) | |||

| NS2b | 390 | 130 | 390 (78) | 130 (88) | 390 (76) | 130 (88) | 390 (56) | 130 (50) | |||

| NS3 | 1,869 | 623 | 1,869 (79) | 623 (93) | 1,869 (77) | 623 (92) | 1,869 (67) | 623 (71) | |||

| NS4a | 378 | 126 | 378 (75)) | 126 (87) | 378 (75) | 126 (92) | 378 (61) | 126 (57) | |||

| 2k | 69 | 23 | 69 (71) | 23 (70) | 69 (74) | 23 (91) | 69 (61) | 23 (57) | |||

| NS4b | 744 | 248 | 744 (79) | 248 (94) | 744 (77) | 248 (91) | 750 (66) | 250 (64) | |||

| NS5 | 2,721 | 906 | 2,721 (78) | 906 (88) | 2,721 (76) | 906 (89) | 2,718 (66) | 905 (68) | |||

| 3′ UTR | 472 | NA | 459 (86) | NA | 478 (84) | NA | 508 (65) | NA | |||

| Polyprotein | 10,218 | 3,405 | 10,218 (79) | 3,405 (91) | 10,218 (77) | 3,405 (89) | 10,236 (63) | 3,411 (61 | |||

| Full genome | 10,807 | NA | 10,793 (79) | NA | 10,814 (77) | NA | 10,862 (62) | NA | |||

*Values are sequence length (% identity with FRV). FRV, Fitzroy River virus (GenBank accession no. KM 361634); NS, nonstructural; SEPV, Sepik virus (GenBank accession no. NC008719); UTR, untranslated region; WESSV, Wesselsbron virus (accession no. JN226796); YFV, yellow fever virus (X03700); NA, not applicable.

FRV was highly similar to SEPV across the structural viral proteins, including the membrane (96%) and envelope (96%) proteins. Over the full genome, FRV displayed the highest nucleotide identity to SEPV (79%), WESSV (77%), and YFV (62%). These lower nucleotide identities are in contrast to the polyprotein amino acid homologies (SEPV 91%, WESSV 89%, YFV 61%), indicating that a large proportion of nucleotide differences between FRV and SEPV or WESSV were synonymous. The level of nucleotide identity was higher in the 5′ and 3′ UTRs (94% and 86%, respectively) than in structural proteins (up to 81%) for FRV and SEPV, reflecting the functional importance of the UTRs for virus replication. Closer analysis of several conserved features of flavivirus UTRs is shown in the Technical Appendix Figure. Although comparisons of the cyclization sequences (Technical Appendix Figure, panel C) indicate a high level of conservation among all members of the YFV group, alignments of the upstream AUG region (Technical Appendix Figure, panel D) highlight a clear separation of FRV, SEPV, and WESSV from YFV. When we assessed the string of tandem repeats in the 3′ UTR, some differences between FRV, SEPV, and WESSV emerged. We identified 3 highly conserved repeats in the 3′ UTR of FRV (RFR1, RFR2, and RFR3; Technical Appendix Figure, panel B), which are most similar to the previously described sequences identified in YFV (RYF1, RYF2, and RYF3). Strikingly, WESSV (69.7%–90.6%) and FRV (72.7%–90.6%) retained homologous sequences to RYF1, RYF2, and RYF3, and SEPV retained only a vestigial repeat sequence (RSEP3) that is highly divergent from all other members of the YFV group, including FRV.

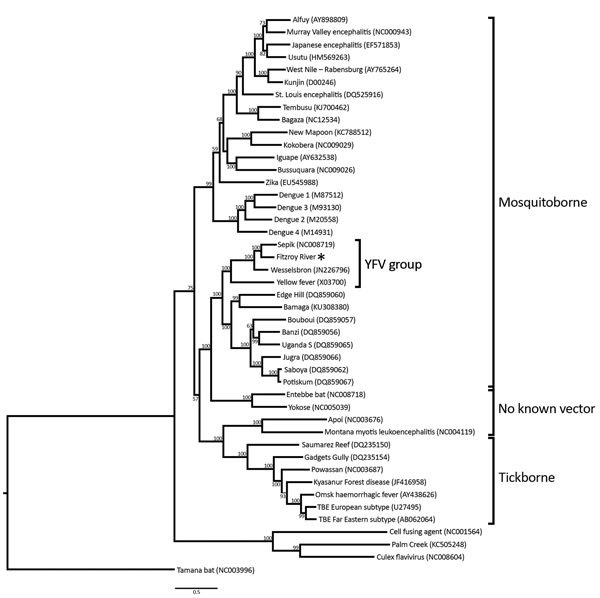

FRV shares a common ancestor with SEPV (with 100% bootstrap support) (Figure 2) and is located in the distinct YFV group according to International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses classification (15). Analysis of the 12 cleavage sites located within the polyprotein open reading frame, following the scheme described by Kuno and Chang (19), supported the phylogenetic structure of the YFV group; YFV displayed marked divergence from FRV, SEPV, and WESSV in several cleavage sites, including Ci/PrM, NS1/NS2a, NS2a/NS2b, and NS2b/NS3 (Technical Appendix Figure, panel E).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the genus Flavivirus, based on full polyprotein nucleotide sequences. Asterisk (*) indicates Fitzroy River virus. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. YFV, yellow fever virus.

Viruses Isolated from Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes yielding isolates of FRV were collected at Fitzroy Crossing in the West Kimberley region in 2011 (Table 3); FRV was isolated from 2 pools of Ae. normanensis and 1 pool of Anopheles amictus mosquitoes. In 2012, a similar level of sampling in the same geographic area (data not shown) showed a shift of activity away from Fitzroy Crossing to a broader area in the eastern and southern Kimberley region, encompassing Billiluna, Kununurra, and Wyndham (Table 3). Sixteen isolates were obtained, most (81.2%) from Ae. normanensis mosquitoes (Table 3) and all from female mosquitoes. Additional virus was isolated from An. amictus, Culex annulirostris, and a pool of damaged and unidentifiable Aedes spp. mosquitoes. The minimum infection rate was greatest at Billiluna (2.5 FRV-infected mosquitoes/1,000 mosquitoes; Table 4). Other arboviruses detected during these seasons included MVEV, KUNV, KOKV, RRV, and Sindbis virus (Table 3).

Table 3. Mosquito species collected and arboviruses isolated from the Kimberley region of Western Australia, Australia, 2011 and 2012*.

| Year, location, mosquito species | No. (%) collected | No. processed | No. pools processed | No. virus isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | ||||

| Fitzroy Crossing | ||||

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 4,657 (38.4) | 2,497 | 110 | 2 FRV, 3 non A/F |

| An. (Cellia) amictus | 750 (6.2) | 504 | 29 | 1 FRV, 4 non A/F |

| An. (Cellia) annulipes s.l. | 2,879 (23.7) | 1,898 | 84 | 6 non A/F |

| Cx. (Culex) annulirostris | 3,202 (26.4) | 1,773 | 79 | 2 MVEV, 1 KUNV, 1 KUNV+SINV, 6 non A/F |

| Other | 635 (5.2) | 482 | 100 | 1 non A/F† |

| Subtotal |

12,123 (100) |

7,154 |

402 |

|

| 2012 | ||||

| Billiluna | ||||

| Ae. (Macleaya) tremulus | 252 (2.0) | 135 | 14 | |

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 1,679 (13.4) | 1,244 | 58 | 3 FRV |

| An. (Cellia) amictus | 650 (5.2) | 508 | 42 | |

| An. (Cellia) annulipes s.l. | 3,456 (27.5) | 1,555 | 74 | |

| An. (Cellia) novaguinensis | 247 (2.0) | 152 | 18 | |

| Cx. (Culex) annulirostris | 5,608 (44.6) | 3,424 | 148 | 2 MVEV |

| Damaged Anopheles spp. | 131 (1.0) | 83 | 14 | |

| Damaged Culex spp. | 218 (1.7) | 111 | 15 | |

| Other | 326 (2.6) | 199 | 84 | |

| Subtotal | 12,567 (100) | 7,411 | 467 | |

| Kununurra | ||||

| Ae. (Finlaya) notoscriptus | 455 (1.3) | 381 | 31 | |

| Ae. (Neomellanoconion) lineatopennis | 3,457 (9.9) | 1540 | 80 | |

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 12,632 (36.2) | 4917 | 219 | 7 FRV, 2 RRV |

| An. (Anopheles) bancroftii | 2,428 (7.0) | 723 | 52 | |

| An. (Cellia) annulipes s.l. | 1,758 (5.0) | 1025 | 67 | |

| An. (Cellia) meraukensis | 2,717 (7.8) | 863 | 60 | |

| Cq. (Coquillettidia) xanthogaster | 931 (2.7) | 796 | 55 | |

| Cx. (Culex) annulirostris | 7,600 (21.8) | 4195 | 193 | 1 RRV |

| Ve. (Verrallina) reesi | 468 (1.3) | 287 | 33 | |

| Damaged Culex spp. | 350 (1.0) | 253 | 30 | 1 RRV |

| Other | 2,111 (6.0) | 1528 | 369 | 4 RRV‡ |

| Subtotal | 34,907 (100) | 16508 | 1189 | |

| Wyndham | ||||

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 1,661 (5.4) | 551 | 30 | 1 FRV, 1 RRV |

| An. (Anopheles) bancroftii | 532 (1.7) | 122 | 14 | |

| An. (Cellia) amictus | 1,589 (5.1) | 380 | 26 | |

| An. (Cellia) annulipes s.l. | 982 (3.2) | 262 | 20 | |

| An. (Cellia) meraukensis | 1,677 (5.4) | 450 | 27 | |

| Cx. (Culex) annulirostris | 21,388 (69.1) | 5,357 | 224 | 1 FRV, 2 KOKV, 4 RRV |

| Cx. (Culex) crinicauda | 330 (1.1) | 62 | 14 | |

| Damaged Culex spp. | 907 (2.9) | 247 | 17 | 1 RRV |

| Other | 1,881 (6.1) | 898 | 206 | 1 FRV, 1 RRV§ |

| Subtotal |

30,947 (100) |

8329 |

578 |

|

| Total | 90,544 | 39,402 | 2,636 |

*Only mosquito collection locations that yielded isolates of FRV are shown; species collected at abundance of <1.0% are grouped as “other”; named species are female mosquitoes only. Results from male mosquitoes are included in “other.” Ae., Aedes; An., Anopheles; Cq., Coquillettidia; Cx., Culex; FRV, Fitzroy River virus; KOKV, Kokobera virus; KUNV, West Nile (Kunjin) virus; non A/F, not an alphavirus or flavivirus and identity is yet to be determined, MVEV, Murray Valley encephalitis virus; RRV, Ross River virus; SINV, Sindbis virus; Ve., Verrallina. †Isolated from female Ae. lineatopennis mosquito. ‡Isolated from female Aedeomyia catasticta (1), Anopheles amictus (1), and Mansonia uniformis (2) mosquitoes. §FRV isolated from a pool of damaged female Aedes spp. mosquitoes, RRV isolated from female An. bancroftii mosquitoes.

Table 4. Minimum infection rates of mosquitoes infected with FRV, Western Australia, Australia, 2011 and 2012*.

| Year, location, mosquito species | No. isolates | Minimum infection rate† |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | ||

| Fitzroy Crossing | ||

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 2 | 0.8 |

|

An. (Cellia) amictus

|

1 |

2.0 |

| 2012 | ||

| Billiluna | ||

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 3 | 2.5 |

| Kununurra | ||

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 7 | 1.4 |

| Wyndham | ||

| Ae. (Ochlerotatus) normanensis | 1 | 1.8 |

| Cx. (Culex) annulirostris | 1 | 0.2 |

| Damaged Aedes spp. | 1 | 1.1 |

*Ae., Aedes; An., Anopheles; Cx, Culex; FRV, Fitzroy River virus. †No. FRV-infected mosquitoes/1,000 mosquitoes; calculated according to (35).

In Vitro Virus Replication

FRV replicated in all 4 cell lines tested. At all time points, the FRV titer grew higher in BSR than in other cell lines, with the exception of Vero cells on day 7; the difference was usually significant (Table 5). Mild CPE was not apparent until day 4 in BSR cells and day 7 in Vero and DF-1 cells; no CPE was evident in C6/36 cells.

Table 5. Fitzroy River virus replication in 4 cell lines.

| Day |

Mean Fitzroy River virus titer* |

|||

| C6/36 |

Vero |

BSR |

DF-1 |

|

| 1 | 0a | 0a | 3.07 ± 0.06b | 0a |

| 2 | 4.68 ± 0.21a | 3.78 ± 0.05b | 5.13 ± 0.06c | 3.81 ± 0.3ab |

| 3 | 5.58 ± 0.05a | 4.72 ± 0.02b | 6.67 ± 0.08c | 5.5 ± 0.08a |

| 4 | 6.66 ± 0.09a | 5.02 ± 0.07b | 6.72 ± 0.05a | 6.26 ± 0.15a |

| 7 | 4.41 ± 0.14a | 7.01 ± 0.01b | 6.6 ± 0.21b | 4.25 ± 0.23a |

*Statistical significance of log transformed arithmetic means was determined with 2-way analysis of variance with correction for multiple comparisons and using the Tukey method for pairwise multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). Means in the same row followed by the same superscript letter did not differ significantly (p>0.05). Results at day 0 were excluded because virus detected at this time point represented residual inoculum.

Virus Virulence in Mice

Two female mice in the 1,000 IU intracerebrally inoculated group and 1 female mouse in the 100 IU intracerebrally inoculated group had hind limb weakness, intermittent photophobia, and/or mild retrobulbar swelling between 5 and 12–13 dpi; however, only 1 female mouse in each intracerebrally inoculated group received a score of 1 on 1–2 days (days 5 and 9). By 13–14 dpi, all mice appeared to be clinically healthy. The only abnormality in intraperitoneally inoculated mice was mild photophobia in 1 mouse in the 1,000 IU group at 6 dpi. Mock-challenged animals showed no clinical abnormalities throughout the study period. All intracerebrally inoculated mice seroconverted; antibody titers were >160. In the intraperitoneally inoculated group, 6 mice in the 100 IU group seroconverted and 8 mice in the 1,000 IU group seroconverted (titers 40 to >160), indicating successful FRV replication.

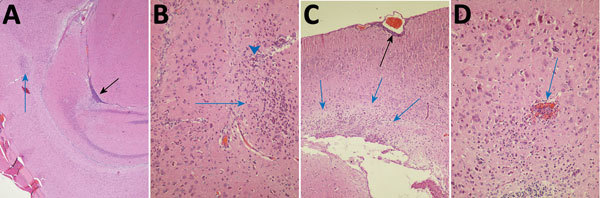

For the 3 mice in which subtle clinical signs developed, we processed the heads for histopathology. We found histopathologic signs of meningoencephalitis in all 3 (Figure 3, panels A–D). The lesions were most notable in the 1,000 IU intracerebrally inoculated group, corroborating the mild clinical signs observed. The least severe lesions were seen in the mouse from the 100 IU intracerebrally inoculated group; however, the lesions were unilateral in the hemisphere not inoculated. In the other 2 mice, the trend was toward greater severity in the inoculated hemisphere; however, in the other hemisphere and distant from the inoculation site, we found leukocyte infiltration, gliosis, and neuronal degeneration. No viral antigen was detected in the affected brains by immunohistochemistry, suggesting that FRV was cleared at the time of euthanasia (21 dpi).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of Fitzroy River virus (FRV)–induced meningoencephalitis in weanling mice inoculated with 1,000 infectious units of FRV. Panels show multifocal mild to severe perivascular and neuropil infiltration of lymphocytes and monocytes (blue arrows in A–C); meningitis in a sulcus (black arrow in A); glial cell activation with notable astrocytosis, neuron degeneration, and neuronophagia (arrowhead in B); occasional hemorrhage (blue arrow in D); mild periventricular spongiosis (blue arrows in C); and meningitis (black arrow in C). Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Original magnifications: A) ×40, B) ×400, C) ×100, D) ×400.

Antibodies in Humans and Animals

A total of 366 serum samples from humans from northern Western Australia, submitted to PathWest Laboratory Medicine WA for alphavirus or flavivirus serologic testing from March through May in 2014 and 2015, were tested for antibodies to FRV (Technical Appendix Table). Overall, the prevalence of antibodies to flaviviruses in the ELISA was 33.6%, of which initial screening showed an FRV neutralization titer >10 in 9 samples. For 3 of these samples, cross-neutralization titers showed FRV antibody titers >40 and at least a 4-fold difference between antibody titer to FRV and other flaviviruses from Australia (Table 6), yielding an FRV positivity rate of 0.8% (3/336) of all samples tested and 2.4% (3/123) of samples with evidence of a flavivirus infection by ELISA. All 3 FRV antibody–positive samples were from the West Kimberley (Broome) region.

Table 6. Serologic test results for 9 serum samples from humans from northern Western Australia, which contained FRV neutralizing antibodies at initial testing*.

| Sample |

ELISA, % block |

FRV initial neutralization titer |

Cross-neutralization titers | Infecting virus |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRV |

MVEV |

KUNV |

ALFV |

KOKV |

STRV |

EHV |

||||

| 2014–1 | 79 | 10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | UD |

| 2014–2 | 87 | 20 | <10 | 10 | 10 | <10 | 10 | 10 | 40 | EHV |

| 2014–3 | 86 | 40 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 20 | 80 | EHV |

| 2014–4 | 84 | 160 | 40 | <10 | 10 | <10 | <10 | 10 | <10 | FRV |

| 2015–1 | 90 | 80 | <10 | <10 | 160 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | KUNV |

| 2015–2 | 92 | 20 | <10 | <10 | 80 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | KUNV |

| 2015–3 | 98 | 40 | 80 | <10 | 10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | FRV |

| 2015–4 | 95 | 80 | 80 | 10 | 20 | <10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | FRV |

| 2015–5 | 98 | 10 | <10 | <10 | 10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | UD |

*ALFV, Alfuy virus (K74157); EHV, Edge Hill virus (K74003); FRV, Fitzroy River virus (K73884); KOKV, Kokobera virus (K69949); KUNV, West Nile (Kunjin) virus (K81136); MVEV, Murray Valley encephalitis virus (K68150); STRV, Stratford virus (C338); UD, undetermined.

Serum from 227 sentinel cattle, 87 horses, and 178 sentinel chickens from the Northern Territory sampled from 2009/10 through 2014/15 were tested for antibodies to FRV. Neutralizing antibodies to FRV were detected in horses (12.6%) and cattle (6.6%). FRV and SEPV cross-neutralization tests on a subsample of FRV antibody–positive serum samples indicated that the FRV infections were not the result of serologic cross-infection with closely related SEPV (data not shown), which occurs in neighboring Papua New Guinea. One sentinel chicken had a low FRV antibody titer. Most FRV infections in domestic animals (n = 24; 77%) were from 2012/13. We also tested serum from 25 wallabies, 1 wallaroo, and 1 bandicoot from the Northern Territory, collected from 2006/07 through 2013/14. Low levels of FRV antibodies were found in 1 wallaby from the Darwin region in January 2007. We found no association between infection and clinical disease in any cattle, horses, chickens, or marsupials tested.

Discussion

The new flavivirus from northern Australia, for which we proposed the name Fitzroy River virus, was first isolated from Ae. normanensis mosquitoes collected near the Fitzroy River. Phylogenetic analysis of isolate K73884 demonstrates that FRV belongs to the YFV group (15). Cleavage recognition sequence analysis groups FRV together with WESSV and SEPV, but distinct from YFV, reflecting the pattern of amino acid homology of members of the YFV group across the polyprotein. When homology of individual viral proteins is assessed, FRV is most closely related to SEPV in all regions excluding some nonstructural components that have a required role in replication (36,37), notably NS4a and 2k, where homology to WESSV was higher. We found no evidence of recombination breakpoints occurring along the FRV genome, and the low (70%) amino acid homology observed in the 2k peptide is most likely the result of a collection of nonsynonymous mutations. However, this recombination analysis was limited to 44 reference flavivirus sequences; a larger collection that includes more YFV group isolates from the Southeast Asia region may reveal further insights into the evolutionary history of FRV.

The phylogenetic placement of FRV in the YFV group is further supported by analysis of features in the flavivirus UTRs (cyclization sequence, upstream AUG region, and tandem repeats), sequences that are functionally necessary for enhancing replication through formation of secondary RNA structures (38). Although we observed near complete consensus in the cyclization sequence at each terminus between these 4 viruses, FRV had higher levels of identity to SEPV and WESSV than YFV across the respective upstream AUG regions. Conversely, the tandem repeats found in the 3′ UTR showed consistently high nucleotide identities (>80% across all 3 sites) with YFV rather than WESSV and SEPV. Together, these data indicate that FRV possesses a unique collection of sequence signatures that distinguish it from other members of the YFV group.

The origin of FRV is unknown. Although increased surveillance in neighboring countries is needed, arbovirus and mosquito monitoring has been pursued in northern Western Australia since the early 1970s (39,40) with only minor changes in strategy. FRV was not detected by virus culture from earlier mosquito collections, a finding consistent with recent introduction into Western Australia and possibly elsewhere in Australia, thus highlighting the value of ongoing surveillance activities. We cannot exclude the possibility that FRV was circulating in mosquitoes of species (or other insect vectors) not commonly collected in traps routinely used for surveillance of adult mosquitoes in Western Australia and that genetic changes enabled the virus to adapt to a new host species, as has been seen with chikungunya virus (41).

Phylogenetic analysis indicated that FRV is most closely related to SEPV in the YFV group, which is currently found only in Papua New Guinea, and WESSV, which occurs in Africa and Thailand. Recent experience with introduction of likely or suspected arbovirus and arbovirus vectors into northern Australia suggests that FRV was probably introduced from Southeast Asia. Included are introductions by mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti (L.), Aedes vexans, and Culex gelidus (42,43) and introductions of viruses including Japanese encephalitis virus from Papua New Guinea (44), bluetongue viruses from Southeast Asia (45,46), and epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus 1 from Indonesia (47).

Most (81%) FRV has been isolated from Ae. normanensis mosquitoes, providing circumstantial evidence that this species may be the dominant vector. Mosquito collections at each locality were conducted ≈2–3 weeks after a period of high rainfall following a relatively dry period. These conditions favor an abundance of Ae. normanensis mosquitoes because these mosquitoes rapidly hatch from desiccation-resistant eggs (48). The detection of antibodies to FRV in sentinel animals from the Northern Territory is consistent with the range and feeding behavior of Ae. normanensis mosquitoes and indicates a wide distribution of FRV in northern Australia.

Our finding of serologic evidence of human infection by FRV, despite low prevalence and apparent confinement to the West Kimberley region, is noteworthy. We detected FRV more extensively across northern Western Australia, so further human infections are likely. Because these samples had been sent for routine diagnostic arbovirus testing, it is presumed that most persons had a clinical illness of concern; however, we did not have access to detailed clinical information. Also, because the samples were single rather than paired acute- and convalescent-phase samples, we could not determine whether the FRV antibodies are the result of acute or previous infections. The antibody titers to FRV in humans were low, and although the cross-neutralizations included all known Australian flaviviruses that replicate in the cell lines we used, these persons may have been infected with an unrecognized flavivirus.

The close relationship of FRV with WESSV and SEPV may indicate potential for FRV to affect domestic animals such as cattle, goats, and sheep. Cattle stations are a dominant agricultural feature of northern Australia. Given that most FRV was isolated from Ae. normanensis mosquitoes, that mosquitoes of this species readily feed on cattle and horses, and that the FRV antibody prevalence in sentinel cattle and horses in the Northern Territory was high, we believe that the enzootic transmission cycle for FRV probably involves Ae. normanensis mosquitoes and domestic animals such as cattle and horses. Infection with FRV was not associated with clinical disease in animals but could potentially be disguised by other arbovirus infections, such as bovine ephemeral fever (49).

The finding of mild clinical signs in FRV-infected weanling mice, more often in those that were intracerebrally infected, indicates that severe clinical disease may be unlikely unless the health of the animal host is compromised. Further research is required to determine if FRV causes clinical disease in humans or domestic animals. The outcomes of this study demonstrate the value of surveillance for mosquitoborne viruses in the detection, characterization, and impact assessment of novel and known arboviruses.

Detection of neutralizing antibodies to Fitzroy River virus in humans and animals in northern Western Australia and the Northern Territory, Australia, and additional details on the characterization of Fitzroy River virus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Lindsay, Peter Neville, and Susan Harrington for assistance with mosquito collections. The assistance of Sarah Power, Margaret Wallace, and Michael Burley with mosquito identification and virus detection is gratefully acknowledged. Technical staff at PathWest provided assistance with PCR and sequencing, and Stephen Davis kindly performed the neutralization assays on animal serum from the Northern Territory. Willy Suen, Caitlin O’Brien, and Agathe Colmant assisted with animal experiments. We also thank John Mackenzie for helpful discussion and the Medical Entomology Branch of the WA Department of Health for funding.

Additional financial support was provided by the Department of Health through the Funding Initiative for Mosquito Management in Western Australia. S.H.W. and W.I.L. were supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. AI109761, Center for Research and Diagnostics and Discovery, Center for Excellence in Translational Research). D.T.W. was funded by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

Biography

Dr. Johansen is a senior medical scientist at PathWest Laboratory Medicine WA and adjunct senior research fellow at The University of Western Australia; her research interests include mosquito and arbovirus surveillance and ecology of arboviruses and vectors. Mr. Williams is a staff associate at the Center for Infection and Immunity, Columbia University, New York, USA; his research interests include rodent and arthropodborne viruses and disease transmission.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Johansen CA, Williams SH, Melville LF, Nicholson J, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, et al. Characterization of Fitzroy River virus and serologic evidence of human and animal infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Aug [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2308.161440

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Broom AK, Lindsay MDA, Harrington SA, Smith DW. Investigation of the southern limits of Murray Valley encephalitis activity in Western Australia during the 2000 wet season. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2002;2:87–95. 10.1089/153036602321131887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broom AK, Lindsay MDA, Johansen CA, Wright AET, Mackenzie JS. Two possible mechanisms for survival and initiation of Murray Valley encephalitis virus activity in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:95–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansen CA, Susai V, Hall RA, Mackenzie JS, Clark DC, May FJ, et al. Genetic and phenotypic differences between isolates of Murray Valley encephalitis virus in Western Australia, 1972-2003. Virus Genes. 2007;35:147–54. 10.1007/s11262-007-0091-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell RC. Arboviruses and their vectors in Australia: an update on the ecology and epidemiology of some mosquito-borne arboviruses. Review of Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 1995;83:141–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen C, Broom A, Lindsay M, Avery V, Power S, Dixon G, et al. Arbovirus and vector surveillance in Western Australia, 2004/05 to 2007/08. Arbovirus Research in Australia. 2009;10:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowled C, Palacios G, Melville L, Weir R, Walsh S, Davis S, et al. Genetic and epidemiological characterization of Stretch Lagoon orbivirus, a novel orbivirus isolated from Culex and Aedes mosquitoes in northern Australia. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1433–9. 10.1099/vir.0.010074-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohe D, Fall RP. A miniature battery powered CO2 baited light trap for mosquito borne encephalitis surveillance. Bulletin of the Society of Vector Ecology. 1979;4:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broom AK, Wright AE, Mackenzie JS, Lindsay MD, Robinson D. Isolation of Murray Valley encephalitis and Ross River viruses from Aedes normanensis (Diptera: Culicidae) in Western Australia. J Med Entomol. 1989;26:100–3. 10.1093/jmedent/26.2.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindsay MDA, Broom AK, Wright AE, Johansen CA, Mackenzie JS. Ross River virus isolations from mosquitoes in arid regions of Western Australia: implication of vertical transmission as a means of persistence of the virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:686–96. 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quan PL, Williams DT, Johansen CA, Jain K, Petrosov A, Diviney SM, et al. Genetic characterization of K13965, a strain of Oak Vale virus from Western Australia. Virus Res. 2011;160:206–13. 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierre V, Drouet MT, Deubel V. Identification of mosquito-borne flavivirus sequences using universal primers and reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction. Res Virol. 1994;145:93–104. 10.1016/S0923-2516(07)80011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:863–4. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chevreux B, Wetter T, Suhai S. Genome sequence assembly using trace signals and additional sequence information. Computer Science and Biology: Proceedings of the German Conference on Bioinformatics. 1999;99:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee of Taxonomy of Viruses: London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice CM, Lenches EM, Eddy SR, Shin SJ, Sheets RL, Strauss JH. Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution. Science. 1985;229:726–33. 10.1126/science.4023707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuno G, Chang GJ. Characterization of Sepik and Entebbe bat viruses closely related to yellow fever virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:1165–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1:vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Prow NA, May FJ, Westlake DJ, Hurrelbrink RJ, Biron RM, Leung JY, et al. Determinants of attenuation in the envelope protein of the flavivirus Alfuy. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2286–96. 10.1099/vir.0.034793-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent end points. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prow NA, Setoh YX, Biron RM, Sester DP, Kim KS, Hobson-Peters J, et al. The West Nile virus-like flavivirus Koutango is highly virulent in mice due to delayed viral clearance and the induction of a poor neutralizing antibody response. J Virol. 2014;88:9947–62. 10.1128/JVI.01304-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suen WW, Prow NA, Setoh YX, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. End-point disease investigation for virus strains of intermediate virulence as illustrated by flavivirus infections. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:366–77. 10.1099/jgv.0.000356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roby JA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Prow NA, Chang DC, Hall RA, Khromykh AA. Increased expression of capsid protein in trans enhances production of single-round infectious particles by West Nile virus DNA vaccine candidate. J Gen Virol. 2014;95:2176–91. 10.1099/vir.0.064121-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall RA, Broom AK, Hartnett AC, Howard MJ, Mackenzie JS. Immunodominant epitopes on the NS1 protein of MVE and KUN viruses serve as targets for a blocking ELISA to detect virus-specific antibodies in sentinel animal serum. J Virol Methods. 1995;51:201–10. 10.1016/0166-0934(94)00105-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansen CA, Mackenzie JS, Smith DW, Lindsay MD. Prevalence of neutralising antibodies to Barmah Forest, Sindbis and Trubanaman viruses in animals and humans in the south-west of Western Australia. Aust J Zool. 2005;53:51–8. 10.1071/ZO03042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uren MF. Bovine ephemeral fever virus. In: Corner L, Bagust T, editors. Australian Standard Diagnostic Techniques for Animal Disease. Melbourne (Australia): The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grard G, Moureau G, Charrel RN, Holmes EC, Gould EA, de Lamballerie X. Genomics and evolution of Aedes-borne flaviviruses. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:87–94. 10.1099/vir.0.014506-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuno G, Chang G-JJ, Tsuchiya KR, Karabatsos N, Cropp CB. Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus. J Virol. 1998;72:73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henchal EA, Gentry MK, McCown JM, Brandt WE. Dengue virus-specific and flavivirus group determinants identified with monoclonal antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:830–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark DC, Lobigs M, Lee E, Howard MJ, Clark K, Blitvich BJ, et al. In situ reactions of monoclonal antibodies with a viable mutant of Murray Valley encephalitis virus reveal an absence of dimeric NS1 protein. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1175–83. 10.1099/vir.0.82609-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broom AK, Hall RA, Johansen CA, Oliveira N, Howard MA, Lindsay MD, et al. Identification of Australian arboviruses in inoculated cell cultures using monoclonal antibodies in ELISA. Pathology. 1998;30:286–8. 10.1080/00313029800169456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macdonald J, Poidinger M, Mackenzie JS, Russell RC, Doggett S, Broom AK, et al. Molecular phylogeny of edge hill virus supports its position in the yellow Fever virus group and identifies a new genetic variant. Evol Bioinform Online. 2010;6:91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiang CL, Reeves WC. Statistical estimation of virus infection rates in mosquito vector populations. Am J Hyg. 1962;75:377–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell CL, Smith DR, Sanchez-Vargas I, Zhang B, Shi PY, Ebel GD. A positively selected mutation in the WNV 2K peptide confers resistance to superinfection exclusion in vivo. Virology. 2014;464-465:228–32. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller S, Kastner S, Krijnse-Locker J, Bühler S, Bartenschlager R. The non-structural protein 4A of dengue virus is an integral membrane protein inducing membrane alterations in a 2K-regulated manner. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8873–82. 10.1074/jbc.M609919200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gritsun TS, Gould EA. Origin and evolution of 3'UTR of flaviviruses: long direct repeats as a basis for the formation of secondary structures and their significance for virus transmission. Adv Virus Res. 2007;69:203–48. 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)69005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liehne CG, Leivers S, Stanley NF, Alpers MP, Paul S, Liehne PFS, et al. Ord River arboviruses—isolations from mosquitoes. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1976;54:499–504. 10.1038/icb.1976.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liehne PFS, Stanley NF, Alpers MP, Liehne CG. Ord River arboviruses—the study site and mosquitoes. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1976;54:487–97. 10.1038/icb.1976.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e201. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whelan P, Hayes G, Tucker G, Carter J, Wilson A, Haigh B. The detection of exotic mosquitoes in the Northern Territory of Australia. Arbovirus Research in Australia. 2001;8:395–404. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansen CA, Lindsay MDA, Harrington SA, Whelan PI, Russell RC, Broom AK. First record of Aedes (Aedimorphus) vexans vexans (Meigen) (Diptera: Culicidae) in Australia. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21:222–4. 10.2987/8756-971X(2005)21[222:FROAAV]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johansen CA, van den Hurk AF, Ritchie SA, Zborowski P, Nisbet DJ, Paru R, et al. Isolation of Japanese encephalitis virus from mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) collected in the Western Province of Papua New Guinea, 1997-1998. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:631–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pritchard LI, Sendow I, Lunt R, Hassan SH, Kattenbelt J, Gould AR, et al. Genetic diversity of bluetongue viruses in south east Asia. Virus Res. 2004;101:193–201. 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melville LF, Pritchard LI, Hunt NT, Daniels PW, Eaton B. Genotypic evidence of incursions of new strains of bluetongue viruses in the Northern Territory. Arbovirus Research in Australia. 1997;7:181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weir RP, Harmsen MB, Hunt NT, Blacksell SD, Lunt RA, Pritchard LI, et al. EHDV-1, a new Australian serotype of epizootic haemorrhagic disease virus isolated from sentinel cattle in the Northern Territory. Vet Microbiol. 1997;58:135–43. 10.1016/S0378-1135(97)00155-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Webb C, Dogggett S, Russell R. A guide to mosquitoes of Australia. Melbourne (Australia): CSIRO Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geoghegan JL, Walker PJ, Duchemin JB, Jeanne I, Holmes EC. Seasonal drivers of the epidemiology of arthropod-borne viruses in Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3325. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detection of neutralizing antibodies to Fitzroy River virus in humans and animals in northern Western Australia and the Northern Territory, Australia, and additional details on the characterization of Fitzroy River virus.