Abstract

Background:

Estimates of psychiatric morbidity in the community will help service development. Participation of trained nonspecialist health-care providers will facilitate scaling up of services in resource-limited settings.

Aims:

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of priority mental health problems in populations served by the District Mental Health Program (DMHP).

Settings and Design:

This is a population-based cross-sectional survey.

Materials and Methods:

We did stratified cluster sampling of households in five districts of Kerala. Trained Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) identified people who had symptoms suggestive of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Clinicians evaluated the information collected by the ASHAs and designated individuals as probable cases of psychosis or noncases. Screening instruments such as General Health Questionnaire-12, CAGE questionnaire, and Everyday Abilities Scale for India were used for identifying common mental disorders (CMDs), clinically significant alcohol-related problems, and functional impairment.

Results:

We found 12.43% of the adult population affected by mental health conditions. We found CMD as most common with a prevalence of 9%. The prevalence of psychosis was 0.71%, clinically significant alcohol-related problems was 1.46%, and dementia and other cognitive impairments was 1.26%. We found informant-based case finding to be useful in the identification of psychosis.

Conclusions:

Mental health problems are common. Nonspecialist health-care providers can be trained to identify psychiatric morbidity in the community. Their participation will help in narrowing the treatment gap. Embedding operational research to DMHP will make scaling up more efficient.

Keywords: Alcohol dependence, bipolar disorder, common mental disorders, community health workers, District Mental Health Program, prevalence of psychiatric morbidity, psychosis, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

The wide treatment gap in mental health calls for scaling up of services.[1] Shortage of mental health professionals makes scaling up a difficult task in low- and middle-income countries. Nonspecialist health-care providers can be trained to identify the unmet needs and facilitate care in the community and primary care settings.[2]

The District Mental Health Program (DMHP) is the flagship program under the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) of India. It is operational in more than 225 districts, covering more than one-third of the country. Scaling up of mental health care is its goal. The DMHP provides decentralized specialist services through their monthly outreach clinics. They also train and equip nonspecialist health-care providers, particularly primary care doctors, to deliver mental health care in community and primary care settings.

Psychiatric disorders differ in their nature, severity, and prevalence. Estimates of their prevalence in the community will help service development. This, however, is not an easy task. Interviewing a large number of individuals by specialists is difficult because of issues related to feasibility and costs.[3] We chose an innovative case finding method to estimate the lifetime prevalence of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. We also wanted to see whether health workers after training can administer simple screening tools to identify conditions such as common mental disorders (CMDs), alcohol-related problems, and cognitive impairment. This paper describes the prevalence estimates made by the study co-ordinated by the Kerala State Mental Health Authority and carried out by the DMHP teams in five districts of Kerala. Our aim was to estimate the prevalence of mental health problems in the community with the help of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) employed under the National Health Mission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Five districts of Kerala, two each from northern and central regions and one from the southern region (Kasaragod, Wayanad, Palakkad, Idukki, and Kollam), were selected for the survey. We used a cross-sectional study design. The research was carried out with the involvement and supervision by the DMHPs in these districts.

Sampling

We used random cluster sampling. Block Panchayaths in each district were stratified into East, West, and Mid zones. One Block Panchayath from each zone was chosen. We chose three Grama Panchayaths from each Block Panchayath and chose wards at a ratio of 1:7. The urban areas (municipalities and corporations) were grouped together. One municipality or a corporation was selected for each district. The wards were again selected at the ratio of 1:7.

Procedure

We prepared a booklet which contained (a) a questionnaire to collect sociodemographic and household details; (b) Symptoms in Others Questionnaire (SOQ) to screen for major neuropsychiatric disorders;[4] (c) Symptom of Psychosis, a checklist based on the psychosis module of mhGAP Intervention Guide;[5] (d) General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)[6] to screen for CMDs which is a group of minor psychiatric illnesses such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and others; (e) Everyday Abilities Scale for India (EASI)[7] to screen for functional impairment due to dementia and other cognitive impairments; and (f) CAGE questionnaire[8] to screen for problems related to alcohol abuse.

All the study instruments were translated into local language by adopting standard procedures of translation, back translation, and cultural adaptation. We trained ASHAs to administer these tools. They then visited the households in the designated area. A key informant, either the head of the household or a senior family member available in the household, was identified and the aims of the study was explained. All adult members of the household were invited to participate in the study. The study instruments were administered after obtaining informed consent. The subjects were assured confidentiality of the information they provide. The home visits were often repeated to meet all household members. Information regarding mentally ill members in the family, issues related to their care, and the needs of the family was collected using Need Assessment Questionnaire, which we designed. Families were also given information about the availability of mental health-care services. We relied on the ration card issued by the state government to measure the socioeconomic status. All those with a ration card designated as “below poverty line” were considered as poor and rest were considered as “above poverty line (APL)” for the purpose of the study.

Training for Accredited Social Health Activists

A 2-day training program was organized in each district before the commencement of the study. This training program was designed by a committee consisting of the principal investigators and they supervised the implementation of the training program. The 1st day of training focused on enhancing the mental health knowledge of ASHAs and building their skills to interview key informants and elicit symptoms of psychiatric illness, especially that of psychosis. The DMHP team comprising a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, psychiatric social worker, and a nurse supervised the training program. The training was based on mhGAP Intervention Guide.

Handouts and leaflets were prepared in Malayalam. The same material was used at all sites. Case vignettes were used to describe prototypes of each condition. ASHAs were encouraged to describe and discuss probable cases from their catchment area. They were also given specific training in the administration of study instruments. More opportunities for interactive learning were provided on the 2nd day. The public health importance of this research and the importance of their role were made explicit to them. We wanted them to be stakeholders in this initiative as they will continue to serve the same population.

Field work monitoring

Although the ASHAs were assigned simple tasks, we offered them support during their field work. ASHAs could call clinicians over telephone to clarify their doubts. The co-coordinating center located at Government Medical College, Thrissur, took up the responsibility of handling the unresolved issues and provided clarifications, assistance, and directions to all centers as and when needed. We also organized periodic group reviews at all centers. These were interactive sessions aimed at giving and getting feedback.

The survey took place between 2014 and 2015. The completed survey forms were sorted and organized. We identified the files of the households reporting symptoms on SOQ. These files were then evaluated by a psychiatrist to see whether the reported symptoms are suggestive of psychosis, mental retardation (MR), epilepsy, dementia, and alcohol-related problems. Participants were then classified as probable case, possible case, or a noncase. When psychosis was considered, the clinician tried to classify them further as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, whenever this was possible. These diagnostic considerations were based on the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) classification. The prevalence estimates were made after combining both probable and possible cases.

All cases of psychosis identified in four GramaPanchayaths of Palakkad district were followed up with inquiries with the ASHAs or other key informants in an attempt to validate the diagnosis of psychosis. Psychiatrists working with the Palakkad DMHP made visits to the community. They interviewed the ASHAs and asked them to visit the family and organize personal interviews with the subjects and their family members. We estimated the positive predictive value (PPV) of this case identification method based on the evaluations made by the clinicians in the community.

Statistical analysis

Proportions and means were used to describe the sample. We estimated the lifetime prevalence of psychosis in general and that of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in particular. The estimates of lifetime prevalence of epilepsy and MR were solely based on the response to the relevant items in SOQ. The point prevalence rates of CMDs, alcohol-related problems, and that of dementia and other cognitive impairments were estimated. A score of 3 or more on GHQ-12 was taken as indicative of CMD. A score of 2 or more on CAGE was considered as cutoff score for identifying individuals with clinically significant alcohol-related problems. A score of 4 and above on the EASI was taken as indicative of functional impairment due to dementia or other cognitive impairments. Screen-positive cases were then compared with screen-negative cases to identify risk factors using multivariate analysis. We used Chi-square test to find the association between sociodemographic factors and mental disorders. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios for risk assessment. Missing data were considered as missing when detailed analysis was undertaken.

Data entry and data management were done using Microsoft Excel, and the software used for data analysis was R version 3.1.2 (Pumpkin Helmet) R Development Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (http://www.R-project.org).

RESULTS

The survey was done by 221 ASHAs. They collected details of the households from 45,886 households with 192,980 residents. The prevalence estimates were made for this population. The data from all centers were combined and reviewed for errors and missing data. We found missing data on several variables. Multiple factors such as nonavailability of reliable informants at the time of home visits, problems with data collection, omissions during documentation into survey forms, and omissions during data entry had contributed to this. We had to limit the detailed analysis to 41,572 households with complete details.

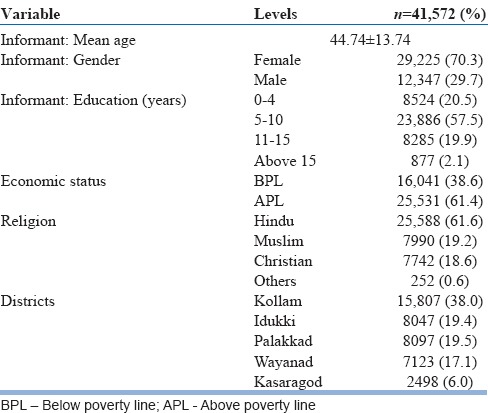

The informants from 1344 (2.9%) households reported presence of a person with mental health problem in the family. The characteristics of all the households which were surveyed are given in Table 1. Majority of the informants were females aged < 45 years with 5–10 years’ education.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of 41,572 households

Lifetime prevalence of psychosis

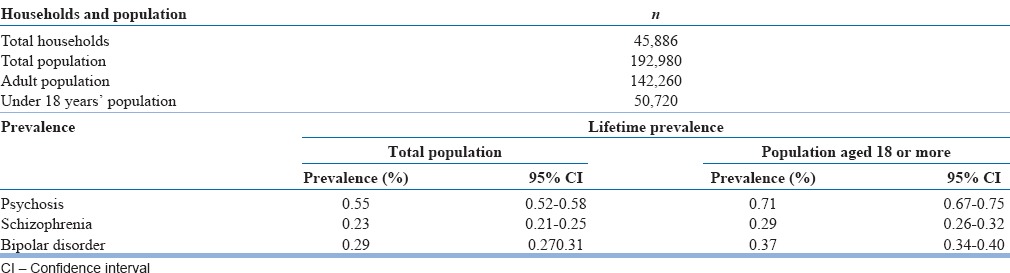

A total of 1062 individuals were considered as probable or possible cases of psychosis by the psychiatrist after evaluating the documented information collected by the ASHAs during the survey. The estimated lifetime prevalence of psychosis in this study was 0.55% (95% CI: 0.52–0.58). There were 1009 individuals who had clinical features suggestive of psychosis among 142,260 individuals who were aged 18 years or more. The estimated lifetime prevalence rate of psychosis among adults (those who are 18 or older) was 0.71% (95% CI: 0.66–0.74). There were 53 cases of psychosis among 50,720 individuals who were aged < 18 years giving a lifetime prevalence estimate of 0.10%.

We used the same strategy to estimate the lifetime prevalence rates for schizophrenia and found it to be 0.23% (95% CI: 0.21–0.25). The estimated lifetime prevalence rate for schizophrenia among adults (those who are 18 or older) was 0.29% (95% CI: 0.26–0.32).

The lifetime prevalence rate for bipolar disorder was 0.29% (95% CI: 0.27–0.31) and the estimated lifetime prevalence rate for bipolar disorder among adults (those who are 18 or older) was 0.37% (95% CI: 0.34–0.40) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Lifetime prevalence of psychosis

We used an informant-based case finding method to identify cases of psychosis in the community. Psychiatrists who work along with the community mental health team at Palakkad reviewed the cases of psychosis identified from the four GramaPanchayaths. They interviewed the ASHAs to collect more information. The ASHAs in turn contacted the family members to get more details. The subjects and the family members were invited for personal interviews. Whenever that was not possible, the family members were contacted to get relevant details about the illness. ICD-10 guidelines were used for the diagnostic evaluation. The survey identified 121 subjects who had symptoms suggestive of psychosis. Psychiatrists could personally interview 29 subjects and only family members could be interviewed for 12 other subjects. All ASHAs were interviewed by the psychiatrists after they made home visits. This information was used to arrive at the diagnosis of psychosis. Clinicians agreed with the diagnosis of psychosis in 104 subjects. The PPV of this method was 86%. Most cases who did not receive a diagnosis of psychosis were found to be having conditions such as MR, dementia, or alcohol-related problems.

Prevalence of mental retardation and epilepsy

We identified 450 (0.23%) individuals with epilepsy among the 192,980 people in the 45,886 households surveyed. There were 400 (0.21%) individuals with symptoms indicative of MR. We did not evaluate these cases further.

Prevalence of common mental disorders

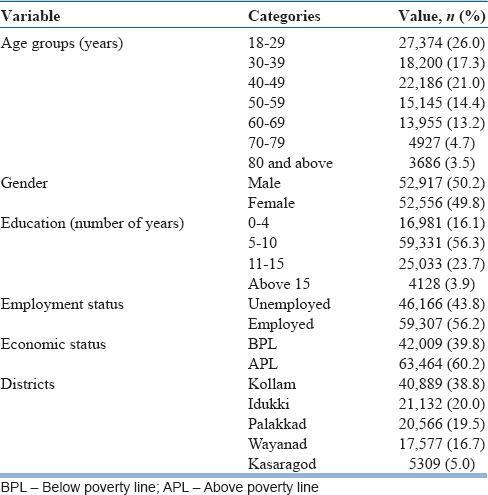

Profile of individuals who completed GHQ-12 (n = 105,473) is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Profile of individuals screened with the General Health Questionnaire-12 (n=105,473)

Most of the adults screened for CMD were aged 18–29 years. Both genders were almost equally represented. Most of them (56.3%) had 5–10 years of education, 56.2% were employed, and 39.8% of them belonged to families below the poverty line. Mean GHQ scores increased with advancing age. Women had higher mean GHQ score across all age groups.

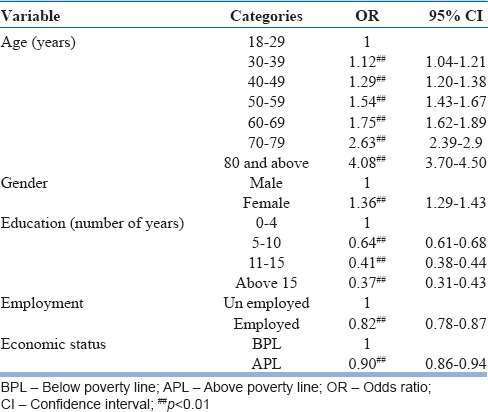

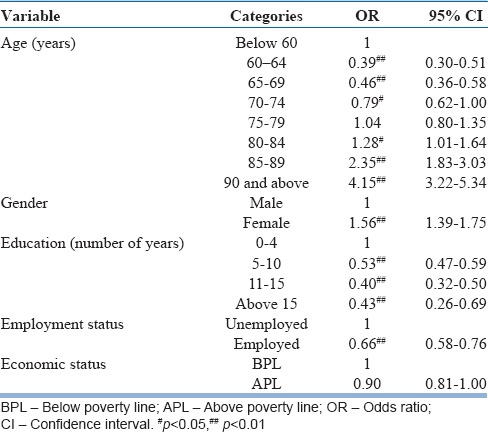

We used a cutoff point of 3 or more for GHQ-12, and the prevalence rate of those screened positive for CMD among adults was 9.0% (95% CI: 8.83–9.17). We used logistic regression to identify factors associated with those screened positive for CMD. Individuals aged above 40 years and females were at higher risk for CMD. More number of years of education, employment, and better socioeconomic (APL) status were protective factors [Table 4].

Table 4.

Factors associated with the General Health Questionnaire-positive cases (common mental disorders) on logistic regression

Prevalence of clinically significant alcohol-related problems

CAGE questionnaire was administered to 3163 individuals identified as having alcohol-related problems by the ASHAs. Only these cases were given CAGE questionnaire. We considered a CAGE score of 2 or more as indicative of clinically significant alcohol-related problems. We found 2108 (66.6%) of them having a score of 2 or more. The estimated prevalence of clinically significant alcohol-related problems was 1.09% (95% CI: 1.04–1.14). Vast majority of them (98.43%) were aged 18 years or older. Prevalence of alcohol-related problems among the adult population (aged 18 years or more) was 1.46% (95% CI: 1.40–1.52). Males accounted for 95.3% of all cases. Almost half of those with alcohol-related problems had severe problems.

Prevalence of dementia and other cognitive impairments

We used EASI to assess the activities of daily living of 16,649 individuals using EASI. There were 15,642 individuals who were aged 60 years or older. Among them, 1639 (10.48%) had a score of 4 or more on EASI. The estimated prevalence of dementia and other cognitive impairments was thus 10.48% among older people. There were 1007 individuals who reportedly had problems with memory and thus were screened though their age was below 60 years. We did a multivariate analysis and found age and female gender to be risk factors for cognitive impairment among older people. Education and employment were found to be protective factors [Table 5].

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of the Everyday Abilities Scale for India scores

The findings related to the need assessment will be discussed in a separate paper.

Combined prevalence of priority psychiatric disorders

While making an estimate of the combined prevalence of mental health conditions such as psychosis, CMD, cognitive impairment, and alcohol-related problems for the adult population, we have to presume that comorbidity (an individual diagnosed with more than one condition) is infrequent and thus will not alter the estimate of total prevalence. However, this may not be true. In that case, combined rates will exceed the actual prevalence. While attempting to combining the rates, we found 12.43% of the adult population to be affected by priority mental health conditions. This included those screened positive for CMDs (9%), alcohol-related problems (1.46%), dementia, and other cognitive impairments (1.26%). We found the prevalence of psychosis to be 0.71% in the adult population.

DISCUSSION

We found psychiatric morbidity common among the adult population of Kerala. Common Mental Disorder was most frequent with 9% of the adult population screened positive on GHQ-12. Outreach workers like ASHAs are capable of participating in community-based research. We found informant-based case finding to be a useful method for identifying cases of psychosis in the community. Simple, short screening questionnaires can be used to estimate the prevalence of CMD, alcohol-related problems, and cognitive impairment. Active case finding by trained community health workers will be helpful in identifying unmet mental health needs in the community.

Lifetime prevalence of psychosis, mental retardation, and epilepsy

We found the prevalence of psychosis in the adult population to be 0.71% (95% CI: 0.66–0.74). The prevalence of schizophrenia was 0.29% (95% CI: 0.26–0.32) and that of bipolar disorder was 0.37% (95% CI: 0.34–0.40). These rates are comparable to the rates reported by the Indian Council of Medical Research collaborative study of severe mental morbidity and the National Mental Health Survey[9] The prevalence of epilepsy and MR was low at 0.23% and 0.21%, respectively, when compared to earlier studies from India.[10] However, there are serious methodological limitations here.

Reliance on the abilities of trained ASHAs for identification of individuals with psychosis is the major limitation of this study. However, the PPV of this case finding method was high (86%). We can train outreach workers like ASHAs to elicit clinical features of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. We found the 2-day training based on mhGAP Intervention Module[5] to be useful in building their case-finding capacity. Informant-based case-finding techniques had been used in community settings and were found to be more useful than structured interviews in identifying conditions such as schizophrenia.[11,12] But then, such methods are likely to miss milder forms of the illness. In any case, identification of individuals with unmet mental health needs by trained health workers can be a good starting point for community care by the DMHP.

Common mental disorder

The prevalence of CMD in the total population was 9.0% (95% CI: 8.83–9.17). We used the GHQ-12 cutoff used by earlier studies from India.[13,14] Our CMD rate is similar to that of the combined rates for depression and other CMDs reported by the NMHS.[9] Our estimates are entirely based on the use of GHQ-12 by trained ASHAs. This is unlike the detailed evaluations used in a recent report from India. They have reported lower rates.[15] The high community prevalence of CMD makes it a major public health challenge for Kerala, more so when the suicidal rates are high.[16] Higher prevalence of CMD in older age groups suggests the prospect of further increase in the prevalence of conditions like depression in older age groups. Depression will emerge as a major public health problem in all rapidly aging societies.

Clinically significant alcohol-related problems

We identified clinically significant alcohol-related problems in 1.46% of the adult population. The prevalence was 3% among men and most of them had serious problems related to alcohol. High alcohol consumption was reported earlier from the state with about one-tenth of the current drinkers in high-risk drinking zone.[17] Our rates only refer to those with clinically significant problems due to their drinking. The proportion of those who abuse alcohol would be much more and we did not estimate the extent of alcohol abuse or drinking pattern. Alcohol abuse, like depression, is associated with suicides and has an adverse impact on the well-being of other family members. We need evidence-informed policies to regulate sale of alcohol in the state and interventions to prevent harm.

Dementia and other cognitive impairments

As per the 2011 Census, 12.6% of Kerala's population is 60 years or older. We found 10.48% among the surveyed older people having functional impairment. We used EASI as a general measure of cognitive disability. These figures do not by any means refer to the community prevalence of dementia. The EASI has only modest sensitivity and specificity when it is used alone for identification of dementia.[18] Earlier studies from Kerala had found the prevalence of dementia to be much lower.[19,20] However, those studies also identified a similar proportion of older people with cognitive dysfunction during the initial evaluation. A variety of disabling conditions could contribute to functional impairment in older people. We found older age, female gender, unemployed status, and low education to be risk factors for cognitive disability. Future research should look for factors which can reduce disability, prevent or postpone its occurrence. The reportedly high prevalence of depression among older people[21] is a matter of concern and can contribute to disability. The increasing number of older people with disabling neuropsychiatric conditions will lead to an exponential increase in the need for long-term care. Home-based care is often associated with significant caregiver burden. Families engaged in care do not get the support they need.[22] Trained health workers can identify and support home-based care.[23] Simple community-based interventions can be of help to people with disabling neuropsychiatric conditions like dementia.[24,25]

Limitations of the study

Reliance on the capacity of trained ASHAs to elicit clinical features of psychosis is the major limitation of the study. Clinician interviews were not carried out to assess all individuals which is the major limitation. It is not easy to schedule interviews with a large number of people in community settings. We used translated validated screening instruments, but did not undertake validation exercises for the translated versions. We also did not estimate the inter-rater reliability between ASHAs. These are other limitations. We had to make best use of the limited time for evaluations done by the ASHAs in households. Hence, we limited ourselves to the use of brief screening instruments instead of detailed diagnostic evaluations.

Population-based surveys to estimate psychiatric morbidity are not easy and can be challenging tasks.[26] We tried to rely on simple, easy case identification methods which can be used by health workers like ASHAs. Our results thus may not represent accurate estimates of the community prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders. Instead, it indicates the extent of psychiatric morbidity in the community.

CONCLUSIONS

Mental health problems are prevalent and identifiable in the community. Depressive disorders and other minor mental health problems are common. A large number of individuals need care and support. Specialists themselves cannot provide mental health care for all those who need it. Training and equipping nonspecialist health-care providers will be a useful strategy to reduce the treatment gap in mental health.

There cannot be health without mental health.[1] Social determinants of health[27] remain relevant for mental health. We found poverty, low education, and unemployed status to be associated with mental health problems. Social interventions cannot be viewed separately from health-care interventions. A public health approach will help. Outcomes would depend on effective implementation of interventions. There is a strong case to make operational research an integral component of programs like the DMHP. This will help us to evaluate and guide the services. Embedding operational research to DMHP will add value by making scaling up more efficient.

Financial support and sponsorship

We o acknowledge the financial support from the National Health Missionby to the Kerala State Mental Health Authority for conducting the survey.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the help and support received from Dr. V. Raman Kutty, Professor, Achuthamenon Centre for Health Science Studies, SCTIMST, Thiruvananthapuram; Dr. K. Rajmohan, Former Director Clinical Epidemiological Resource and Training Centre, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram and Dr. K. Vijayakumar, Former Professor and Head of Community Medicine, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370:859–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V, Maj M, Flisher AJ, De Silva MJ, Koschorke M, Prince M WPA Zonal and Member Society Representatives. Reducing the treatment gap for mental disorders: A WPA Survey. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:169–76. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Math SB, Chandrashekar CR, Bhugra D. Psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaac MK, Kapur RL. A cost-effectiveness analysis of three different methods of psychiatric case finding in the general population. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:540–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mhGAP_intervention_guide/en/

- 6.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27:191–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fillenbaum GG, Chandra V, Ganguli M, Pandav R, Gilby JE, Seaberg EC, et al. Development of an activities of daily living scale to screen for dementia in an illiterate rural older population in India. Age Ageing. 1999;28:161–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 20]. Available from: http://www.nimhans.ac.in/sites/default/files/u197/NMHS%20Report%20%28Prevalence%20patterns%20and%20outcomes%29%201.pdf .

- 10.Math SB, Srinivasaraju R. Indian psychiatric epidemiological studies: Learning from the past. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S95–103. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibre T, Kebede D, Alem A, Negash A, Kibreab S, Fekadu A, et al. An evaluation of two screening methods to identify cases with schizophrenia and affective disorders in a community survey in rural Ethiopia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48:200–8. doi: 10.1177/002076402128783244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyero T, Alem A, Kebede D, Shibire T, Desta M, Deyessa N. Mental disorders among the Borana semi-nomadic community in Southern Ethiopia. World Psychiatry. 2004;3:110–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuruvilla A, Pothen M, Philip K, Braganza D, Joseph A, Jacob KS. The validation of the Tamil version of the 12 item general health questionnaire. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41:217–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prince M 10/66 Dementia Research Group. Care arrangements for people with dementia in developing countries. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:170–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sagar R, Pattanayak RD, Chandrasekaran R, Chaudhury PK, Deswal BS, Lenin Singh RK, et al. Twelve-month prevalence and treatment gap for common mental disorders: Findings from a large-scale epidemiological survey in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:46–55. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_333_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soman CR, Safraj S, Kutty VR, Vijayakumar K, Ajayan K. Suicide in South India: A community-based study in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:261–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute of Medical Statistics, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). IDSP Non-communicable Disease Risk Factors Survey, Kerala, 2007-2008. National Institute of Medical Statistics and Division of Non-communicable Diseases, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandav R, Fillenbaum G, Ratcliff G, Dodge H, Ganguli M. Sensitivity and specificity of cognitive and functional screening instruments for dementia: The Indo-U.S. Dementia Epidemiology Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:554–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaji S, Promodu K, Abraham T, Roy KJ, Verghese A. An epidemiological study of dementia in a rural community in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:745–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaji S, Bose S, Verghese A. Prevalence of dementia in an urban population in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:136–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakulan A, Sumesh TP, Kumar S, Rejani PP, Shaji KS. Prevalence and risk factors for depression among community resident older people in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:262–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaji KS, Smitha K, Lal KP, Prince MJ. Caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease: A qualitative study from the Indian 10/66 Dementia Research Network. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:1–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaji KS, Arun Kishore NR, Lal KP, Prince M. Revealing a hidden problem. An evaluation of a community dementia case-finding program from the Indian 10/66 dementia research network. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:222–5. doi: 10.1002/gps.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dias A, Dewey ME, D’Souza J, Dhume R, Motghare DD, Shaji KS, et al. The effectiveness of a home care program for supporting caregivers of persons with dementia in developing countries: A randomised controlled trial from Goa, India. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prince MJ, Acosta D, Castro-Costa E, Jackson J, Shaji KS. Packages of care for dementia in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murthy RS. National Mental Health Survey of India 2015-2016. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:21–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_102_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]