Abstract

Background:

A high level of preoperative anxiety is common among patients undergoing medical and surgical procedures. Anxiety impacts of gastroenterological procedures on psychological and physiological responses are worth consideration.

Aims and Objectives:

To analyze the effect of listening to Vedic chants and Indian classical instrumental music on anxiety levels and on blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), and oxygen saturation in patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective, randomized controlled trial was done on 199 patients undergoing upper GI endoscopy. On arrival, their anxiety levels were assessed using state and trait scores and various physiological parameters such as HR, BP, and SpO2. Patients were randomly divided into three groups: Group I of 67 patients who were made to listen prerecorded Vedic chants for 10 min, Group II consisting of 66 patients who listened to Indian classical instrumental music for 10 min, and Group III of 66 controls who remained seated for same period in the same environment. Thereafter, their anxiety state scores and physiological parameters were reassessed.

Results:

A significant reduction in anxiety state scores was observed in the patients in Group I (from 40.4 ± 8.9 to 38.5 ± 10.7; P < 0.05) and Group II (from 41.8 ± 9.9 to 38.0 ± 8.6; P < 0.001) while Group III controls showed no significant change in the anxiety scores. A significant decrease in systolic BP (P < 0.001), diastolic BP (P < 0.05), and SpO2 (P < 0.05 was also observed in Group II.

Conclusion:

Listening to Vedic chants and Indian classical instrumental music has beneficial effects on alleviating anxiety levels induced by apprehension of invasive procedures and can be of therapeutic use.

Keywords: Anxiety, endoscopy, Indian classical music, Vedic chants

INTRODUCTION

Hospitals are not a part of our everyday routines. This foreign environment can easily elicit fear and anxiety in patients. More so, if patient has to undergo some invasive procedure, their anxiety increases many folds.[1] Preventing or alleviating intense anxiety during the examination is important not only because of its unpleasantness per se but also because anxiety may prolong the procedure or result in incomplete procedure, greater medication use, increasing the probability of side effects.[2,3]

To reduce patient's anxiety during invasive procedures, various approaches have been used to distract the patient's attention, such as therapeutic communication, information, visualization, aromatherapy, therapeutic touch, and listening to music.[4,5] Scientific studies have shown the value of music therapy on the body, mind, or health of diseased individuals.[6] Clinical trials have revealed a reduction in heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), breathing rate, insomnia, depression, and anxiety with music therapy.[7,8]

There are only few studies which have evaluated the effect of Indian music on anxiety and BP, HR, and oxygen saturation during upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy. Till date, no studies have reported the effect of listening to Vedic chants on these parameters. With this background, we conducted a study to observe the physiological effect of Vedic mantras and Indian classical music in patients undergoing upper GI endoscopy for dyspepsia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

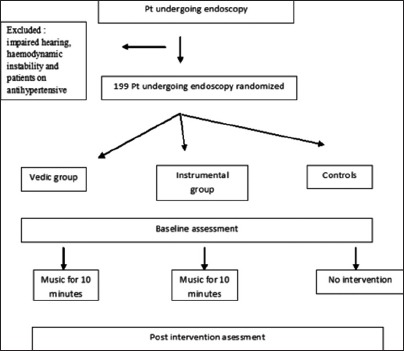

The present study is a randomized control trial conducted in the Department of Physiology and Gastroenterology, Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla and is approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee as per No. (MS) G-5(Ethic)/2015-8368. The study population included patients aged 18 years and above presenting for elective outpatient GI endoscopy for the first time. Exclusion criteria were patients with impaired hearing, hemodynamic instability, and patients on antihypertensive and antipsychotic drugs. The patients who were willing to participate in our study were randomized into three groups by computer-generated numbers [Figure 1]. If alpha is set at 0.05 and power at 0.80, then a sample size of 65 was required for each of the three groups (total n = 195) to detect a medium effect size.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing randomization of study subjects

The selected study participants were asked to move in a separate room where they were administered the consent form. All those who consented to be part of the study were asked to lie down and rest for 30 min. After this, study participants were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) pro forma, which is a self-reporting standardized scale comprising two parts state and trait, used for measuring anxiety level. Biophysiological parameters were recorded in all the patients. BP was measured by the calibrated SSMED sphygmomanometer by tying BP cuff on the right arm in the sitting position. HR and oxygen saturation are measured by the calibrated SSMED pulse oximeter from the left index finger.

Group I consisting of 67 patients were made to listen prerecorded Vedic chants (Purusha Suktam) for 10 min and Group II including 66 patients listened to Indian Classical instrumental music - Santoor (Raga Kaushik Dhwani Gat in Teentaal played by Pandit Shivkumar) for 10 min. Music was played on HP laptop and patients were made to hear the music through head phones. Group III of 66 controls remained seated for same period in the same environment. After intervention, the patients in all the groups were given Y-1 Form of STAI to be filled for assessing their present state of anxiety. Their physiological parameters were again recorded, and then, they were immediately sent for further endoscopy examination.

Statistical analysis

Based on the observation of the study, the data analysis and interpretation were done using descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation (SD) and inferential statistics such as paired’ test, independent t-test, and “Chi-square” test. Statistical software Epi Info version 7.2 (Centre for Disease Control, Atlanta, USA) was used for data analysis. All the authors had accessed to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

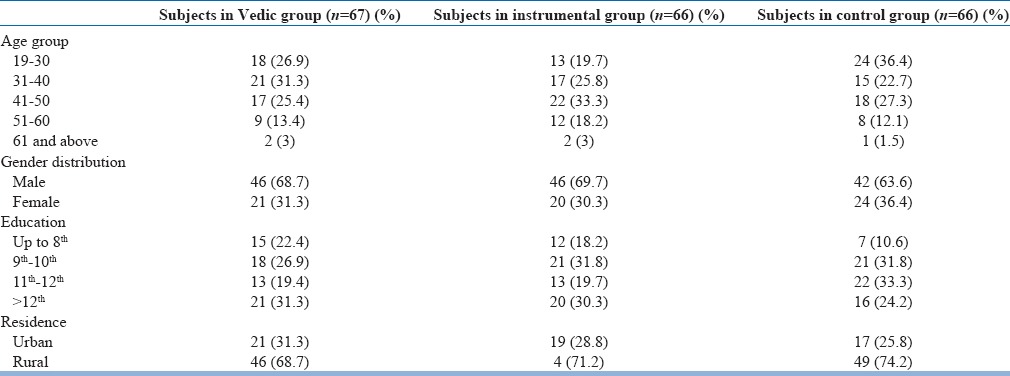

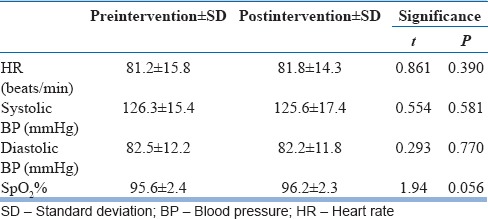

In the present study, a total of 199 patients who underwent gastroscopy were selected. Their age ranged from 19 to 65 years. Age was comparable in all the three groups (P = 0.08). The mean age in the Vedic group was 39.1 years (SD ± 11.1), in the instrumental group was 41.6 years (SD ± 10.6), and in the control group was 37.2 years (SD ± 11.9). There were more males than females in all the three study groups (Vedic 68.7% males, instrumental 69.7% males, and control 63.6% males). The difference between mean height, mean weight, and mean body mass index of the study participants in the Vedic, instrumental, and control group was not statistically significant (P = 0.85, P = 0.85 and P = 0.65, respectively). The baseline physiological parameters recorded in the three groups did not show any statistically significant difference (P > 0.05); the mean HR being 81.2 ± 15.3 beats/min, 83.6 ± 18.2 beats/min, and 83.1 ± 13.8 beats/min in the Vedic, instrumental, and control group, respectively. The mean systolic and diastolic BPs were 126.3 ± 15.4 and 82.5 ± 12.3 mmHg, 131.8 ± 20.8 and 85.5 ± 13.6 mmHg, and 128.1 ± 14.8 and 84.7 ± 12.2 mmHg, respectively, in the Vedic, instrumental, and control group. The mean SpO2 in the Vedic group was 95.6% ±2.4%, in the instrumental group was 95.9% ±2.5%, and in the control group was 94.7% ±2.9% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic comparison of study groups

No statistically significant difference was found in the baseline State and Trait scores while comparing the three groups, their scores being 40.4 ± 8.9 and 44.3 ± 9.0 in the Vedic group, 41.9 ± 9.9 and 44.1 ± 8.1 in the instrumental group, 40.5 ± 8.8 and 44.3 ± 7.7 in the control group.

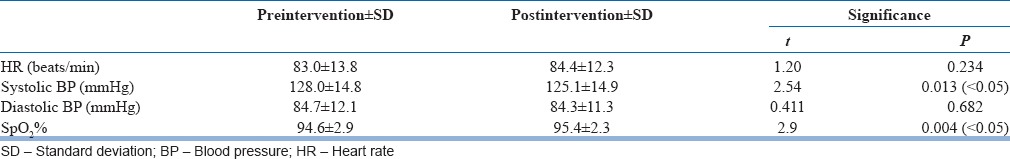

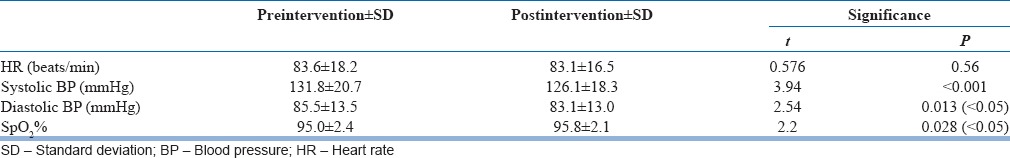

After intervention, the systolic and diastolic BPs decreased in all the three study groups with statistically significant change observed in the instrumental group (from 131.8 ± 20.7 to 126.1 ± 18.3 mmHg, P < 0.001 and from 85.5 ± 13.5 to 83.1 ± 13.0 mmHg, P < 0.05). Similarly, all the study groups showed an increase in SpO2 levels with statistically significant difference in the instrumental group (from 95.0 ± 2.4 to 95.8 ± 2.1%, P < 0.05). Although insignificant, the participants in the instrumental group showed a decrease in HR as compared to the other two groups where HR increased after intervention [Tables 2–4].

Table 2.

Effect of intervention in the Vedic group (n=67)

Table 4.

Effect of intervention in the control group (n=66)

Table 3.

Effect of intervention in the instrumental group (n=66)

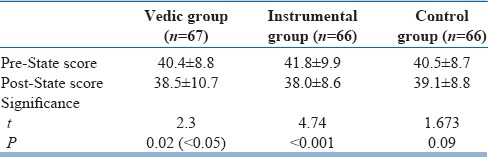

When pre- and post-intervention state anxiety scores were compared, the study groups showed statistically significant reduced anxiety level (from 40.4 ± 8.8 to 38.5 ± 10.7 in the Vedic group and from 41.8 ± 9.9 to 38.0 ± 8.6 in the instrumental group; P < 0.05 and P < 0.001 respectively) with no significant change in the controls (from 40.5 ± 8.7 to 39.1 ± 8.8; P = 0.09) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Change in anxiety state score after intervention

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to detect the possible relationship between State and Trait anxiety in patients undergoing upper GI endoscopy and evaluate the impact of musical intervention on their anxiety levels as measured by the Spielberger's standardized STAI. As cut point of 39–40 is normally used for clinically significant symptoms of anxiety,[9,10,11] our findings suggest that listening to Vedic chants and Indian classical instrumental music resulted in reduction of anxiety levels from clinically significant to clinically insignificant anxiety (<39), while in the control group, the score remained >39. Similar results were obtained by various investigators[12,13,14] in literature who have compared the effect of divergent music on anxiety levels in two groups, i.e., music and control group undergoing endoscopic procedures. The observed effect of music and Vedic chants on anxiety may be due to their ability to distract or modulate mood. This is mediated by the mesocorticolimbic system, the core of which consists of the ventral tegmental area and the ventral striatum, including nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, and prefrontal cortical areas. There is release of both dopamine and endogenous opioids within midbrain structures.[15,16]

Even patients with a low predisposition to anxiety may become apprehensive in the anticipation of surgery and show physical and psychological changes, including increased HR, BP, palpitations, vasoconstriction, nausea, vomiting, and gastric stasis.[17] Increase in HR and vasoconstriction causing rise in BP is modulated by the autonomic nervous system.[18] Music acts on the autonomic nervous system by occupying several neurotransmitters from the auditory center of the temporal lobe, which then signals the hypothalamus, medulla, amygdala, pons, midbrain, and thalamus. This leads to reduction in the sympathetic activity with simultaneous activation of parasympathetic drive along with the reduction of stress hormone levels. The result is anxiolytic diversion from negative stimuli and an integrated hypothalamic relaxation response resulting in reduced HR and BP.[18] A study was conducted by Sutoo and Akiyama[19] on spontaneously hypertensive rats to investigate the mechanism, by which music reduces BP. They suggested that music leads to an increase in calcium/calmodulin-dependent dopamine synthesis in the brain which modifies brain functions. The resultant increase in dopamine levels inhibits sympathetic activity through D2 receptors (by decreasing cAMP activity, opening K+ channels, and blocking Ca++ channels) and thus reduces BP.

In our study, the participants in the instrumental group showed a statistically significant decrease in systolic and diastolic BP with increase in SpO2 after intervention. Decrease in HR was also observed though not statistically significant. Our findings are substantiated by Kotwal et al. who found significant difference in systolic and diastolic BP, HR, and respiratory rate[20] in patients who were made to listen music. Researches done in the past have suggested that a listener's personal music preferences increase the ability of a specific type of music to attenuate an individual's stress levels. Several studies have observed the relaxing effect of classical music, whereas genres such as hip hop, techno music, and heavy metal are commonly associated with physiological arousal. More specifically, a study by Gerra et al. found that listening to techno music led to significant increases in HR and norepinephrine, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels.[21] According to the research by Bernardi et al.,[22] slower or more meditative music such as raga music had significant effect on reducing the HR while faster music and more complex rhythms such as rap, techno, and fast classical had significant effect on increasing the respiratory rate, HR, and BP. Bernardi et al.[23] found that healthy volunteers who listened to self-selected or classical music after exposure to a stressor showed a significant decrease in self-rated anxiety, whereas those exposed to heavy metal or silence did not. This may explain the difference of physiological effects observed in the subjects of our study, when they were made to listen to Vedic chants and Indian classical instrumental music.

The present study adds to many researches on the benefits of music on the body and mind during invasive procedures. Our study is unique and first of its kind to observe the beneficial effects of Vedic chants and Instrumental music on anxiety and physiological parameters. We conclude that endoscopy patients who listen to Vedic chants and/or instrumental music before the procedures shows reduced anxiety scores and improved physiological parameters. It is a clinically meaningful outcome, which would ease the anxiety and increase patient compliance. Another advantage of music therapy is that it poses virtually no risk to patients and has also been shown to help reduce and avoid the unnecessary risks related to excessive consumption of powerful pharmacological agents such as narcotics and sedatives. Moreover, the fact that music therapy programs are relatively inexpensive, suggest that significant benefits in patient well-being and quality of patient care could be achieved by implementation of widespread programs of music therapy throughout the health-care system. A limitation of this study includes the fact this study was done in a single health institution of the state. In the future, multicentric studies can be undertaken to validate the role of music in decreasing the anxiety associated with endoscopic procedures.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carr EC, Nicky Thomas V, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: A longitudinal perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:521–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, Calvet X, Moix J, Rué M, et al. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:201–4. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199902000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudin D. Frequently overlooked and rarely listened to: Music therapy in gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4533. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i33.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harikumar R, Raj M, Paul A, Harish K, Kumar SK, Sandesh K, et al. Listening to music decreases need for sedative medication during colonoscopy: A randomized, controlled trial. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangoulia P, Ouzounidou A. The role of music to promote relaxation in Intensive Care Unit patients. Hosp Chron. 2013;8:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ersöz F, Toros AB, Aydogan G, Bektas H, Ozcan O, Arikan S. Assessment of anxiety levels in patients during elective upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:29–33. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2010.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leardi S, Pietroletti R, Angeloni G, Necozione S, Ranalletta G, Del Gusto B. Randomized clinical trial examining the effect of music therapy in stress response to day surgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94:943–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilliard RE. The effects of music therapy on the quality and length of life of people diagnosed with terminal cancer. J Music Ther. 2003;40:113–37. doi: 10.1093/jmt/40.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight RG, Waal-Manning HJ, Spears GF. Some norms and reliability data for the state – Trait anxiety inventory and the Zung self-rating depression scale. Br J Clin Psychol. 1983;22:245–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1983.tb00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsberg C, Björvell H. Swedish population norms for the GHRI, HI and STAI-state. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:349–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00449430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addolorato G, Ancona C, Capristo E, Graziosetto R, Di Rienzo L, Maurizi M, et al. State and trait anxiety in women affected by allergic and vasomotor rhinitis. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:283–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Hassan H, McKeown K, Muller AF. Clinical trial: Music reduces anxiety levels in patients attending for endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:718–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes A, Buffum M, Lanier E, Rodahl E, Sasso C. A music intervention to reduce anxiety prior to gastrointestinal procedures. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:145–9. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galekovic KA, Olden KW. 7210 Patient anxiety in the preprocedure endoscopy area: effect of music on anxiety levels. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2000;51:AB295. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5107(00)14881-3 . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–94. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelley AE, Berridge KC. The neuroscience of natural rewards: Relevance to addictive drugs. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3306–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson KH, Stakes AF. Effect of anxiety on gastric emptying in preoperative patients. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:540–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thaut MH. Neurophysical processes in music perception and their relevance in music therapy. In: Unkefer RF, editor. Music Therapy in the Treatment of Adults with Mental Disorders: Theoretical Bases and Clinical Interventions. New York: Schirmer Books; 1990. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutoo D, Akiyama K. Music improves dopaminergic neurotransmission: Demonstration based on the effect of music on blood pressure regulation. Brain Res. 2004;1016:255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotwal MR, Rinchhen CZ, Ringe VV. Stress reduction through listening to Indian classical music during gastroscopy. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1998;4:191–7. doi: 10.1155/DTE.4.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerra G, Zaimovic A, Franchini D, Palladino M, Giucastro G, Reali N, et al. Neuroendocrine responses of healthy volounteeres to ‘techno music’: Relationship with personality traits and emotional state. Int J Psychophysiol. 1998;28:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(97)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernardi L, Porta C, Sleight P. Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory changes induced by different types of music in musicians and non-musicians: The importance of silence. Heart. 2006;92:445–52. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.064600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labbé E, Schmidt N, Babin J, Pharr M. Coping with stress: The effectiveness of different types of music. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2007;32:163–8. doi: 10.1007/s10484-007-9043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]