Abstract

The incidence of asthma is increasing globally; however, current treatments are only able to cure a certain proportion of patients. There is an urgent need to develop novel therapies. β1 integrin serves a role in the pathophysiology of asthma through the development of airway remodeling. The aim of the present study was to investigate silencing of the β1 integrin gene in pre-clinical models of allergic asthma. BALB/c mice were sensitized with ovalbumin through intraperitoneal injection and repeated aerosolized ovalbumin. A short hairpin RNA of the β1 integrin gene was designed and transfected into mouse models of asthma in vivo, in order to evaluate whether silencing of the β1 integrin gene affects airway smooth muscle cell proliferation and inflammation by regulating the mRNA expression of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE)-associated genes. Silencing the β1 integrin gene may downregulate β1 integrin mRNA while not statistically decreasing α-smooth muscle actin gene expression and airway smooth muscle thickness. β1 integrin silencing was able to downregulate the transcription of SOCE-associated genes to normal levels, including calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1 and short transient receptor potential channel member 1, but not stromal interaction molecule 1, in asthma. Silencing of the β1 integrin gene additionally maintained nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1 gene expression, and inflammatory cytokines interleukin-4 and interferon-γ at normal levels. The results of the present study provide evidence to suggest that silencing of the β1 integrin gene may be of therapeutic benefit for patients with asthma.

Keywords: asthma, silencing β1 integrin gene, store-operated Ca2+ entry, airway smooth muscle cell proliferation, inflammatory cytokines

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous and chronic inflammatory disease that is defined by a history of respiratory symptoms and variable expiratory flow limitation (1). The dynamics of airway function are influenced by a number of distinct smooth muscles (2). Ca2+ signaling serves an important role in the cellular processes that are known to be altered in the airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) of subjects with asthma, including contractility, proliferation, migration and secretion of inflammatory mediators (3).

Various Ca2+ influx pathways exist in the plasma membranes of ASMCs, including voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, receptor-operated Ca2+ channels, store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) channels and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (4). Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blockers exert no obvious effects on the regulation of airway hyperresponsiveness (5–7); by contrast, SOC channel blockers have been demonstrated to be effective in attenuating airway hyperresponsiveness in ovalbumin-sensitized guinea pigs (8). SOC entry (SOCE) serves an important role in regulating Ca2+ signaling, and the cellular responses and hyperplasia of ASMCs (9–11).

Ca2+ influx through calcium release-activated channels (CRAC) via SOCE has been proposed to be associated with the proliferation of ASMCs (9). The knockdown of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) or calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1 (ORAI1) using small interfering RNA resulted in a decrease in SOCE in response to store depletion by histamine or thapsigargin in human ASMCs, indicating that STIM1 and ORAI1 are important contributors to SOCE in ASMCs exhibiting hyperplasia (12,13). Additionally, ORAI1 has been reported to interact with short transient receptor potential channel member 1 (TRPC1) and forms a ternary complex with STIM1 in the plasma membrane (14,15). TRPC1, a molecular candidate component of SOC channels, has been observed in proliferative porcine ASMCs (9). Therefore, Ca2+ influx through SOCE appears to be important for the regulation of ASMC proliferation.

Structural alterations induced by pathological repair mechanisms, termed airway remodeling, are a consequence of chronic inflammation and mechanical forces in airways exacerbated by asthma (16). β1 integrin is widely-expressed in the airway and the expression is altered in asthma, particularly in ASMCs (17). β1 integrin is associated with cell proliferation, airway and vascular remodeling, obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness (18–20). An increase in β1 integrin expression was observed to be associated with inflammation, fibrosis and airway hyperresponsiveness (20–22). Short hairpin (sh)RNA targeting β1 integrin markedly promoted cellular apoptosis, and inhibited cell proliferation, migration, and interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 secretion in vitro (19).

It was hypothesized that silencing of the β1 integrin gene may inhibit ASMC proliferation and allergic inflammation by attenuating the transcription of SOCE-associated genes. The present study assessed ASM thickness, and the expression of six mRNAs and two inflammatory cytokines. The regulatory effect of silencing the β1 integrin gene may increase the understanding of the complex mechanism of airway remodeling and provide a basis for novel treatments of asthma.

Materials and methods

Animal randomization and modeling

A total of 36 3–4-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Foshan, China) and housed in 6 chambers (6 mice each) with a temperature of 24±3°C, humidity 60±4%, free access to food and water, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Mice were divided into six groups (6 mice/group) using a random number table: group C, control group; group A, asthma group; group T, transfection group; group BC, blank control group; group NC, negative control group; and group PC, positive control group.

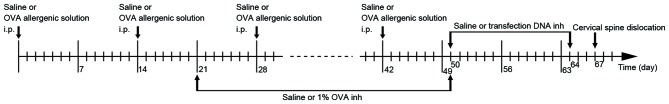

On days 0, 14, 28 and 42, each mouse in group C was injected with 0.2 ml saline into the abdomen, and each mouse in groups A, T, BC, NC and PC were injected with 0.2 ml allergenic solution [10% ovalbumin (OVA; Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) +10% Al(OH)3]. Between days 21 and 50 (3 times/week for 4 weeks), atomized saline was administered to the mice in group C and atomized 1% OVA was administered to the mice in the other groups for 30 mins in a glass test container (30×15×20 cm; Fig. 1). Between days 50 and 64, the mice in group BC were administered 0.2 ml atomized saline, and those in groups T, NC and PC were administered atomized transfection liquid, for 15 mins in a glass container every 2 days (Fig. 1). The atomized transfection liquid consisted of 40 µg transfection DNA, 6 µl transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfection SA, Illkirch, France) and 5 ml 5% glucose solution. β1 integrin shRNA, missense chain and GAPDH were used in groups T, NC and PC, respectively. All of the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation on the 67th day. The flowchart of the establishment of the mouse model is presented in Fig. 1. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen People's Hospital (Shenzhen, China).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the establishment of the mouse model. i.p., intraperitoneal injection; inh, inhalation; OVA, ovalbumin.

shRNA synthesis and vector construction/verification

According to the gene information for β1 integrin in GenBank (no. NM_16412; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank), the 425th nucleotide in the gene encoding region was selected as the initial shRNA target point. Target gene sequences with a GC content between 40 and 55% were selected for potential optimization. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) retrieval was used in the expressed sequence tag database in GenBank. The selected sequence and the corresponding genome database were compared to eliminate homology with other coding sequences and to determine specificity. The efficiencies of sequences in inhibiting the mRNA expression of β1 integrin were assessed using the reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The missense chain was also selected based on β1 integrin gene. An siRNA against GAPDH was included as a positive control to verify transfection reliability, RNA extraction and gene expression quantification. All shRNA sequences used were as follows: β1 integrin, 5′-CACCGCAGGGCCAAATTGTGGGTTTCAAGAGAACCCACAATTTGGCCCTGCTTTTTTG-3′; missense chain, 5′-CACCGCAGGGCCAAATTGTGGGTTTCAAGAGAACCCACAATTTGGCCCTGCTTTTTTG-3′; GAPDH, 5′-CACCGTATGACAACAGCCTCAAGTTCAAGAGACTTGAGGCTGTTGTCATACTTTTTTG-3′.

Subsequent to connecting the carrier to the shRNA section, PCR and electrophoresis were performed. The recombinant positive clone fragments were subjected to sequencing by Guangzhou Genewiz Biotechnology (Guangzhou, China). The experiment also included missense chain as a negative control, and GAPDH as a positive control.

Specimen separation and collection

The left lung was ligated following separation of the trachea, bronchus and lung tissues. Tissue specimens were frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA extraction. The right lung was perfused in 4% polyformaldehyde solution using a 24G indwelling needle. The right middle lobe was separated, ligated and preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining and measurement of ASM thickness

The tissue was embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 µm. Sections were deparaffinized by immersion in xylene and dyed with hematoxylin for 3 mins at room temperature. Sections were washed three times in ddH20 and placed in 85% acid ethanol for 2 mins. The sections were subsequently dyed with eosin for 5 mins and dehydrated through graded alcohols (90, 80 and 70%). The tissues were soaked in xylene, dried and the morphological alterations in the stained sections were examined.

A total of four different cross-sectional airway sections from each specimen were randomly selected to analyze under light microscopy (magnification, ×200). ASM thickness was observed and measured. The ASM thickness of each specimen was calculated from the mean of the four airway cross-sections.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tissue specimens using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was generated using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (DRR037A; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China), and amplified first by PCR using the TaKaRa Ex Taq kit (RR001A; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) to screen the primers, which were designed using Primer 3 software, version 0.4.0 (23), based on data from Uniprot (www.uniprot.org). The thermocycling conditions for the PCR were 95° for 30 sec to activate the DNA polymerase, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec. Melting curve analysis was performed to verify a single product without primer-dimers. The thermocycling conditions of qPCR were the same as above. qPCR was performed on an iQ5 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (DRR081A; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). qPCR results were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (24) and were normalized to β-actin. Primer sequences are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Primers used in the present study.

| Gene name | Gene ID | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product size (bp) | E, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β actin | A1E281 | AAGAGCTATGAGCTGCCTGA | GTTGAAGGTAGTTTCGTGGA | 159 | 98 |

| β1 integrin | P09055 | TTCAGACTTCCGCATTGGCT | TGGAAAACACCAGCAGTCGT | 302 | 104 |

| α-SMA | P62737 | CTCTGCCTCTAGCACACAACT | ACGCTCTCAAATACCCCGTTT | 333 | 96 |

| STIM1 | P70302 | GGTGGAGAAACTGCCTGACA | CAACTGGAGATGGCGTGTCT | 188 | 102 |

| ORAI1 | Q8BWG9 | CCACAACCTCAACTCGGTCA | AACTGCCGGTCCGTCTTATG | 351 | 89 |

| TRPC1 | Q61056 | AGTCCTTCGTTGGAGCTGTG | TGCCTTTCGAGGTATGCGAG | 276 | 103 |

| NFAT2 | Q60591 | ACCTGGCTTGGTAACACCAC | GGGCTGTCTTTCGAGACTTG | 135 | 96 |

E, qPCR efficiency; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule 1; ORAI1, calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1; TRPC1, short transient receptor potential channel member 1; NFAT2, nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1.

ELISA analysis of IL-4 and interferon (IFN)-γ levels in serum

Blood samples were placed in serum separator tubes, maintained at room temperature for 30 min and centrifuged for 15 min with 1,400 × g at 25°C. Serum was transferred into a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube and stored at 4°C. The levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the serum samples were determined using mouse IFN-γ kit DKW 12–2000 and IL-4 ELISA kit DKW12-2040 (Dakewe Biotech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), respectively, in accordance with the manufacturers' protocol.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. P<0.05 was considered to indicate as statistically significant difference. All data represented the average of six replicate experiments. The ASM thickness, RT-qPCR results, and IL-4 and IFN-γ levels were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc tests. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.02; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Identification of β1 integrin shRNA vector

The results demonstrated that the restructured RNA interference vector fragments were all consistent with the synthesized target chain, which confirmed that the synthesized DNA oligo had been successfully inserted into the carrier for the construction of the shRNA vector (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Identification of β1 integrin short hairpin RNA vector.

Assessment of the model and measurement of ASM thickness

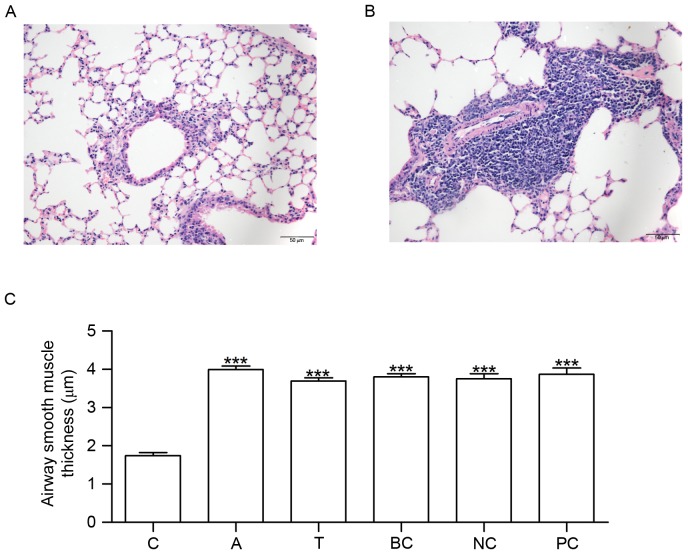

Mice in group C did not exhibit tachypnea or other asthma symptoms. No pathological alterations in the structure of the airway wall were observed in the tissue sections from group C (Fig. 3A). Conversely, mice in group A exhibited tachypnea and mild cyanosis symptoms during OVA-induced asthma. Following continuous OVA-induced asthma, The fur of mice was lackluster in group A. The tissue sections demonstrated epithelial denudation with goblet cell metaplasia, increased thickness of ASM and angiogenesis (Fig. 3B). Compared with group C, ASM thickness was increased in groups A, T, BC, NC and PC (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

HE staining and measurement of airway smooth muscle thickness. Lung tissue sections were stained using HE. The morphological alterations in the stained sections were examined under microscopy. (A) HE staining in C. (B) HE staining in A. (C) Histogram exhibiting the increased airway smooth muscle thickness which occurred in A, T, BC, NC and PC. n=6. ***P<0.001 vs. C. C, control group; A, asthma group; T, transfection group; BC, blank control group; NC, negative control group; PC, positive control group; HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

Silencing of β1 integrin gene regulates the gene expression of SOCE-associated genes and nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1 (NFAT2)

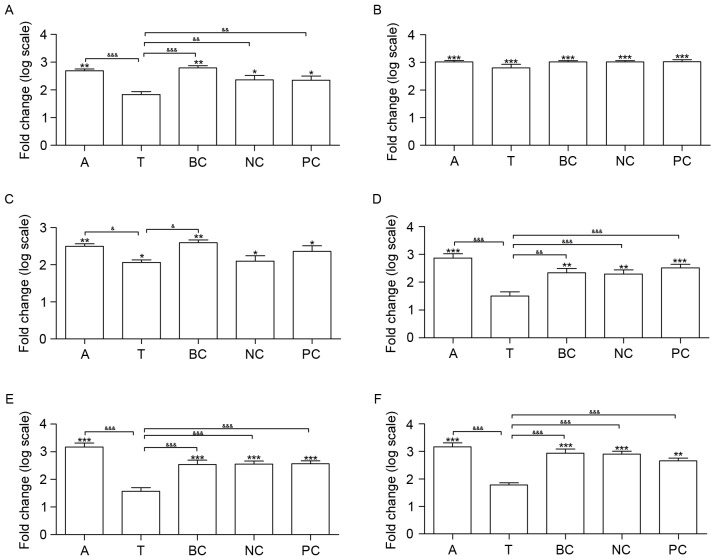

The mRNA expression of six genes was measured in all of the groups, including β1 integrin, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), three SOCE-associated genes (STIM1, ORAI1 and TRPC1) and NFAT2. Compared with group C, the transcription of β1 integrin, all of the SOCE-associated genes and α-SMA was upregulated in groups A, BC, NC and PC (Fig. 4). Additionally, the transcription of α-SMA and STIM1 was upregulated in group T, in contrast with group C. A total of four genes did not exhibit significantly altered expression between groups T and C, including β1 integrin, ORAI1, TRPC1 and NFAT2 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of β1 integrin short hairpin RNA on the expression of β1 integrin, α-SMA and SOCE signaling pathway genes in the lungs of mice. Silencing β1 integrin affected six SOCE signaling pathway genes at the transcriptional level. The mRNA expression of (A) β1 integrin, (B) α-SMA, (C) STIM1, (D) ORAI1, (E) TRPC1 and (F) NFAT2 was measured. n=6. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. C. &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 and &&&P<0.001. C, control group; A, asthma group; T, transfection group; BC, blank control group; NC, negative control group; PC, positive control group; SMA, smooth muscle actin; SOCE, store-operated Ca2+ entry; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule 1; ORAI1, calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1; TRPC1, short transient receptor potential channel member 1; NFAT2, nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1.

Silencing the β1 integrin gene regulates IL-4 and IFN-γ expression levels

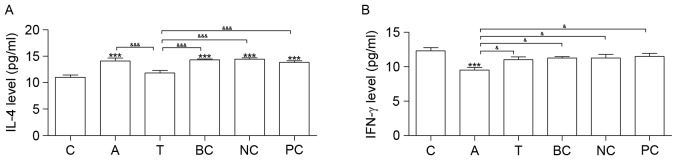

Cytokine IL-4 was increased in groups A, BC, NC and PC compared with group C. Compared with group C, IFN-γ was downregulated in group A (Fig. 5). Neither IL-4 nor IFN-γ exhibited significantly altered expression between groups T and C (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

ELISA analysis. Results of the ELISA analysis of (A) IL-4 and (B) IFN-γ expression levels. n=6. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. C. &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 and &&&P<0.001. C, control group; A, asthma group; T, transfection group; BC, blank control group; NC, negative control group; PC, positive control group; IL-4, interleukin-4; IFN-γ, interferon-γ.

Discussion

The accumulation of β1 integrin in ASM has been demonstrated to be associated with the degree of airway fibrosis, inflammation and hyperresponsiveness (19,20). The present study demonstrated that silencing the β1 integrin gene led to a downregulation of β1 integrin mRNA, without statistically decreasing ASM thickness and α-SMA gene expression, in OVA asthmatic mice. Additionally, silencing of the β1 integrin gene was able to regulate the transcription of SOCE-associated genes at normal levels, including ORAI1, TRPC1 and NFAT2. Silencing of β1 integrin was additionally able to maintain inflammatory cytokines at normal levels in OVA asthmatic mice, including IL-4 and IFN-γ.

β1 integrin shRNA was specifically combined with target β1 integrin mRNA, causing enzymatic degradation of mRNA and thereby decreasing the expression of β1 integrin in mice. The results of the present study demonstrated that the expression level of β1 integrin was not significantly different among groups NC, BC and PC, indicating that the shRNA was able to silence β1 integrin mRNA with high specificity. The present result may provide a foundation for follow-up studies of β1 integrin-targeted intervention in asthma.

Altered expression of calcium channel-associated genes has been associated with airway remodeling in asthma (10,11,25). The results of the present study demonstrated an increase in STIM1, ORAI1 and TRPC1 mRNA levels in the asthma group compared with the control group. STIM1 and ORAI1 have been observed to be upregulated in ASMCs from asthmatic mice (13,25). STIM1/ORAI1-mediated SOCE has been observed to be associated with ASMC proliferation (10). Further studies are required to investigate the expression of STIM1, ORAI1 and TRPC1 in ASMCs from patients with asthma.

Transcriptional modulation of SOC channel-associated genes may represent an important mechanism underlying airway remodeling. The knockdown of ORAI1 expression in synthetic rat ASMCs has been demonstrated to attenuate ASMC proliferation and migration (25). Zou et al (10) observed that suppressing the mRNA expression of STIM1 or ORAI1 with specific shRNA resulted in a decrease in SOCE and ASMC proliferation. The mRNA expression of TRPC1 was observed to be increased in proliferative ASMCs compared with growth-arrested cells by Sweeney et al (9). The results of the present study demonstrated that silencing β1 integrin led to the downregulation of the SOCE-associated genes ORAI1 and TRPC1. Therefore, attenuating the proliferation of ASMCs by silencing β1 integrin may be a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of airway remodeling.

NFAT2 regulates the transcription of pro-inflammatory T cell cytokines (26). T and B cells from ORAI1 knockout mice have been demonstrated to exhibit impaired SOCE and CRAC function, resulting in decreased expression of cytokines IL-4 and IFN-γ in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (27). In the present study, upregulated expression of NFAT2 and IL-4, and downregulation of IFN-γ expression, was observed in the asthma group compared with the control group.

CRAC signaling via SOCE activates NFAT transcription factors in addition to NFAT-promoted gene expression (28,29). Inhibition of the CRAC channel was demonstrated to attenuate allergic inflammation in rats, and airway lymphocyte cytokine production in cells from patients with asthma, by Kaur et al (30). ORAI1-knockout mice were demonstrated to exhibit decreased T cell cytokine production by McCarl et al (27). In addition, Ca2+-signaling of T cells is mediated by the induction of [Ca2+]i by β1 integrin through increased Ca2+-influx (31). In the present study, it was noted that the silencing of β1 integrin maintained the expression of NFAT2 and inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IFN-γ at normal levels. It may be hypothesized that silencing β1 integrin may inhibit allergic inflammation by attenuating the transcription of SOCE-associated genes.

Bronchial hyperresponsiveness has been demonstrated to be associated with airway wall thickness in asthma (16). In addition, the expression of α-SMA has been hypothesized to be an important indicator of airway remodeling in asthma (2). The present study demonstrated that ASM thickness and α-SMA gene expression were increased in Group T, in contrast with Group C. The results of the present study indicated that silencing β1 integrin was insufficient to maintain normal ASM thickness and α-SMA gene expression in asthmatic mice. Previous studies have reported that a number of factors may influence ASM thickness (32,33). For example, Hou et al (32) reported that the anti-inflammatory factor high-mobility group box protein 1 decreased smooth muscle thickness in OVA asthmatic mice. It is hypothesized that silencing β1 integrin may delay the ASMC proliferation and prolong the time of airway remodeling, without altering the final outcome. Numerous signaling pathways may be simultaneously associated with the regulation of ASMC proliferation.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrated that β1 integrin serves a role in ASMC proliferation and airway remodeling. Therefore, silencing β1 integrin may represent a novel target for drug design to attenuate airway remodeling in chronic asthma.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Beijing, China; grant no. 81270074).

References

- 1.Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, Gibson P, Ohta K, O'Byrne P, Pedersen SE, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–178. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slats AM, Janssen K, van Schadewijk A, van der Plas DT, Schot R, van den Aardweg JG, de Jongste JC, Hiemstra PS, Mauad T, Rabe KF, Sterk PJ. Expression of smooth muscle and extracellular matrix proteins in relation to airway function in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1196–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahn K, Ojo OO, Chadwick G, Aaronson PI, Ward JP, Lee TH. Ca(2+) homeostasis and structural and functional remodelling of airway smooth muscle in asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:547–552. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helli PB, Janssen LJ. Properties of a store-operated nonselective cation channel in airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1529–1539. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00054608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendeles L, Hill M, Harman E, Moore P, Pieper J. Dose-response of inhaled diltiazem on airway reactivity to methacholine and exercise in subjects with mild asthma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;43:387–392. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoppe M, Harman E, Hendeles L. The effect of inhaled gallopamil, a potent calcium channel blocker, on the late-phase response in subjects with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89:688–695. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90375-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Twiss M Ann, Harman E, Chesrown S, Hendeles L. Efficacy of calcium channel blockers as maintenance therapy for asthma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:243–249. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohga K, Takezawa R, Yoshino T, Yamada T, Shimizu Y, Ishikawa J. The suppressive effects of YM-58483/BTP-2, a store-operated Ca2+ entry blocker, on inflammatory mediator release in vitro and airway responses in vivo. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney M, McDaniel SS, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, Yu Y, Lapp BR, Zhao Y, Thistlethwaite PA, Yuan JX. Role of capacitative Ca2+ entry in bronchial contraction and remodeling. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92:1594–1602. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00722.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou JJ, Gao YD, Geng S, Yang J. Role of STIM1/Orai1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ entry in airway smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;110:1256–1263. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01124.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinelli AM, Trebak M. Orai channel-mediated Ca2+ signals in vascular and airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;310:C402–C413. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00355.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. A key role for STIM1 in store operated calcium channel activation in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2006;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. ORAI and store-operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:744–749. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0395OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong HL, Cheng KT, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Paria BC, Soboloff J, Pani B, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Singh BB, et al. Dynamic assembly of TRPC1-STIM1-Orai1 ternary complex is involved in store-operated calcium influx. Evidence for similarities in store-operated and calcium release-activated calcium channel components. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9105–9116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608942200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng KT, Liu X, Ong HL, Ambudkar IS. Functional requirement for Orai1 in store-operated TRPC1-STIM1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12935–12940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manuyakorn W. Airway remodelling in asthma: Role for mechanical forces. Asia Pac Allergy. 2014;4:19–24. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2014.4.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teoh CM, Tam JK, Tran T. Integrin and GPCR crosstalk in the regulation of ASM contraction signaling in asthma. J Allergy (Cairo) 2012;2012:341282. doi: 10.1155/2012/341282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei L, Liu D, Huang Y, Jovin I, Shai SY, Kyriakides T, Ross RS, Giordano FJ. Endothelial expression of beta1 integrin is required for embryonic vascular patterning and postnatal vascular remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:794–802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00443-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi F, Qiu C, Qi H, Peng W. shRNA targeting β1-integrin suppressed proliferative aspects and migratory properties of airway smooth muscle cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;361:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bazan-Perkins B, Sánchez-Guerrero E, Vargas MH, Martínez-Cordero E, Ramos-Ramírez P, Alvarez-Santos M, Hiriart G, Gaxiola M, Hernandez-Pando R. Beta1-integrins shedding in a guinea-pig model of chronic asthma with remodelled airways. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:740–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black JL, Panettieri RA, Jr, Banerjee A, Berger P. Airway smooth muscle in asthma: Just a target for bronchodilation? Clin Chest Med. 2012;33:543–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandes DJ, Bonacci JV, Stewart AG. Extracellular matrix, integrins, and mesenchymal cell function in the airways. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:567–577. doi: 10.2174/138945006776818700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spinelli AM, González-Cobos JC, Zhang X, Motiani RK, Rowan S, Zhang W, Garrett J, Vincent PA, Matrougui K, Singer HA, Trebak M. Airway smooth muscle STIM1 and Orai1 are upregulated in asthmatic mice and mediate PDGF-activated SOCE, CRAC currents, proliferation and migration. Pflugers Arch. 2012;464:481–492. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1160-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macian F. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:472–484. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarl CA, Khalil S, Ma J, Oh-hora M, Yamashita M, Roether J, Kawasaki T, Jairaman A, Sasaki Y, Prakriya M, Feske S. Store-operated Ca2+ entry through ORAI1 is critical for T cell-mediated autoimmunity and allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2010;185:5845–5858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samanta K, Bakowski D, Parekh AB. Key role for store-operated Ca2+ channels in activating gene expression in human airway bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Feske S, Cruz-Guilloty F, Oh-hora M, Neems DS, Hogan PG, Rao A. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16232–16243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaur M, Birrell MA, Dekkak B, Reynolds S, Wong S, De Alba J, Raemdonck K, Hall S, Simpson K, Begg M, et al. The role of CRAC channel in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;35:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schottelndreier H, Mayr GW, Guse AH. Beta1-integrins mediate Ca2+-signalling and T cell spreading via divergent pathways. Cell Signal. 1999;11:611–619. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(99)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou C, Kong J, Liang Y, Huang H, Wen H, Zheng X, Wu L, Chen Y. HMGB1 contributes to allergen-induced airway remodeling in a murine model of chronic asthma by modulating airway inflammation and activating lung fibroblasts. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:409–423. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park CS, Bang BR, Kwon HS, Moon KA, Kim TB, Lee KY, Moon HB, Cho YS. Metformin reduces airway inflammation and remodeling via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:1660–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]