Abstract

Reducing health disparities is a national public health priority. Latinos represent the largest racial/ethnic minority group in the United States and suffer disproportionately from poor health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease risk. Academic training programs are an opportunity for reducing health disparities, in part by increasing the diversity of the public health workforce and by incorporating training designed to develop a skill set to address health disparities. This article describes the Training and Career Development Program at the UCLA Center for Population Health and Health Disparities: a multilevel, transdisciplinary training program that uses a community-engaged approach to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in two urban Mexican American communities. Results suggest that this program is effective in enhancing the skill sets of traditionally underrepresented students to become health disparities researchers and practitioners.

Keywords: health disparities, Latino, minority health, workforce development

INTRODUCTION

Reducing health disparities is a major goal of Healthy People 2020 and has been a central goal of the national public health policy agenda for decades. By health disparities we mean group differences in health that are unnecessary, preventable, and unjust (Whitehead, 1992). A growing body of public health research and practice focuses on Latino communities (Dinwiddie, Zambrana, & Garza, 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2014), as they represent the largest racial/ethnic minority group in the United States (Daviglus et al., 2012) and exhibit a disproportionate burden of chronic disease (Daviglus et al., 2012; Vega, Rodriguez, & Gruskin, 2009), as well as high rates of poverty and social disadvantage (Lopez, 2015). Almost two thirds of the U.S. Latino population is composed of people of Mexican-origin (Lopez, 2015), for whom there is an increasing body of scientific literature documenting high rates of cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension (Dinwiddie et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2014). Despite increasing interest and efforts to improve health outcomes among Latinos, the imbalance between the proportion of Latinos in the public health workforce and their representation in the general U.S. population is a persistent challenge (Rodriguez et al., 2014). The lack of public health training in transdisciplinary and multilevel approaches is halting progress in reducing health disparities (Golden et al., 2015; Rodriguez et al., 2014).

A promising strategy for advancing health disparities research and practice in underserved Latino communities is through the development of academic pipeline programs for traditionally underrepresented students (Guerrero et al., 2015; Holden, Rumala, Carson, & Siegel, 2014; Kuo et al., 2015). Such programs can help train a more diverse public health workforce as well as build capacity among trainees to deal with health-related issues in a burgeoning Latino population and in a culturally competent manner. Evaluations of such programs have shown an increase in students’ pursuit of graduate degrees and professional positions in public health (Duffus et al., 2014).

Training and academic pipeline programs are supported by the idea that a public health workforce that is more representative of the populations being served can help improve quality of care and health outcomes and more effectively reduce health disparities (Lichtenstein, 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2014). Research indicates that health professionals from underrepre-sented groups are more likely than their nonminority peers to work in underserved communities (Holden et al., 2014; Ko, Heslin, Edelstein, & Grumbach, 2007; Kuo et al., 2015; Ortega et al., 2015).

This article describes an innovative training program at the UCLA Center for Population Health and Health Disparities (UCLA CPHHD) that provides men-torship, training, research, and programmatic opportunities for high school, undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, and junior faculty. The UCLA CPHHD training program focuses on recruiting students from underrepresented racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds who demonstrate an interest and commitment to an academic career focused on reducing Latino health disparities. This training program applies a multilevel, transdisciplinary approach toward improving health disparities by engaging mentors and trainees from a wide range of disciplines, including community health, health services research, biostatistics, epidemiology, psychology, medicine, pediatrics, arts and media, Chicano studies, nutrition, and integrative physiology.

OVERVIEW OF UCLA CPHHD

The UCLA CPHHD is one of 10 nation-wide CPHHD centers, 5 of which are funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and 5 of which are funded by the National Cancer Institute (Golden et al., 2015). The UCLA CPHHD conducts projects that are situated in neighboring East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights, two predominantly Mexican American communities in Los Angeles County, California. East Los Angeles, in particular, is the largest Latino community in the United States in terms of proportion (98%), and almost half (47%) of residents are foreign-born (U. S. Census Bureau, 2010). The average educational level of East Los Angeles is lower than the state’s average; and the percentage of persons living below the federal poverty level is higher than the state’s average (U. S. Census Bureau, n.d.).

The UCLA CPHHD has implemented a community-engaged intervention to improve the food landscape by converting locally owned corner stores to be healthy food retailers in an effort to increase community access to fresh and affordable fruits and vegetables (Ortega et al., 2015). This corner store “makeover” project also has a youth training component involving local high school students, who are trained as public health advocates.

UCLA CPHHD TRAINING AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

The design of the UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program was guided by adult learning theory, which emphasizes creating learning experiences that minimize didactic instruction and maximize self-directed learning and that also encourage a wide range of instructional activities to appeal to varied experience levels and background (Merriam, 2001). Moreover, three overarching principles guide the training program: mentorship, collaboration, and community-engagement. The UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program emphasizes meaningful training and mentorship opportunities to enhance trainees’ skill sets to provide a pathway to working on community health and development initiatives (Figure 1). The UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program has multiple entry-points along the academic trajectories: high school, undergraduate, master’s-level, and doctoral students; postdoctoral fellows; and junior faculty.

Figure 1.

Framework for Training Pathway in Latino Health Disparities Research

THE NEXT GENERATION OF COMMUNITY HEALTH YOUTH ADVOCATES

In an effort to increase the diversity in health professions, the UCLA CPHHD developed efforts that heavily emphasize working with local high school students. The UCLA CPHHD also worked directly with high school students in part because some experts cited the lack of support and mentorship for minority and low-income students in Grades K-12 as “the single biggest impediment to greater diversity in the health professions” (Grumbach & Mendoza, 2008).

For the youth training component, we implemented a food justice and health advocacy elective curriculum that covers cardiovascular health, nutrition, food justice, social marketing, media advocacy, and video production. As part of their community engagement requirement, the students developed short videos on healthy eating, carried out cooking demonstrations at converted corner stores, and participated in various health-oriented community events. These activities were well-received in the community and led to a partnership with a local YMCA that implemented a similar program. The youth engaged in similar social marketing activities and developed the Mi Vida, Mi Salud (My Life, My Health) Cookbook, a bilingual compilation of selected recipes that youth have prepared, focusing on fruits and vegetables. Students were also mentored by graduate students, who helped with their admissions essays for 4-year colleges and/or job applications and searched for enrichment activities, such as writing workshops and volunteer opportunities, to bolster their academic and professional skill sets.

UCLA CPHHD SUMMER PROGRAM

Since 2011, UCLA CPHHD offers a 10-week trans-disciplinary, community-engaged summer training program focusing on Latino health disparities. Trainees were primarily recruited from 4-year institutions throughout Los Angeles County. For example, UCLA CPHHD–affiliated faculty promoted the program via class listservs among undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral students. Representatives of UCLA CPHHD also attended campus-wide student activities fairs at UCLA CPHHD as well as at neighboring universities. Community partners in the East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights neighborhoods recruited students through their professional networks to help increase the representativeness of Latinos in the program. UCLA CPHHD–affiliated faculty also recruited students through their professional networks that facilitated the participation of trainees from institutions across the country.

Over the course of the first 4 years, 37 students have completed the summer training program (17 undergraduate, 6 master’s students, 13 PhD students, and 1 dietetic intern). Trainees represent a wide range of academic disciplines including ethnomusicology, dietetics, journalism, anthropology, biology, political science, and public health. Trainees were predominantly Latino (57%) but represented a diverse group of students (21% Asian, 19% non-Latino White, and 3% African American). Trainees were almost evenly split between genders (54% female). Since the passage of Proposition 209 in 1996, the UCLA CPHHD is not allowed to identify race or ethnicity as part of its admissions process. However, the application for the training program includes a series of questions that can identify whether a student is disadvantaged, either economically or educationally (first-generation college).

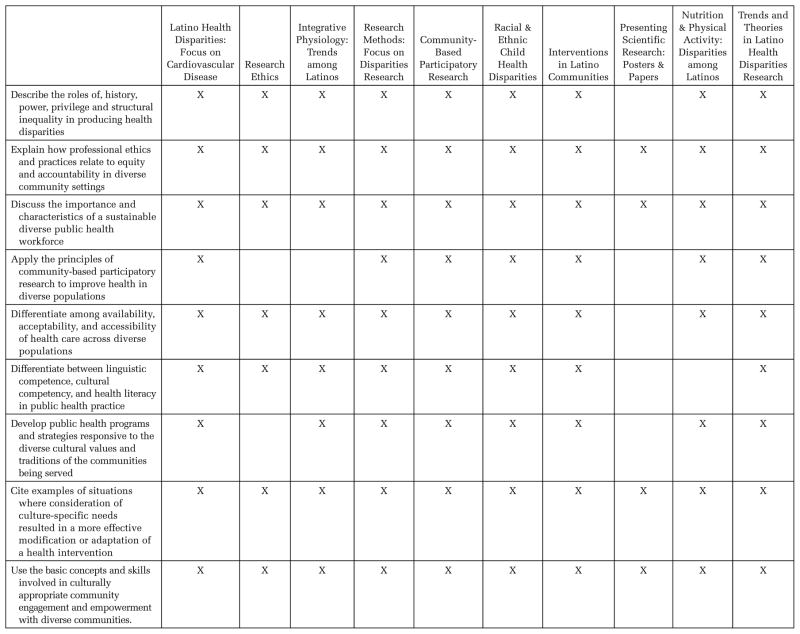

The summer program provides students with a wide-range of academic and professional development opportunities to increase exposure to community-engaged research. Trainees’ activities include assistance with grant writing, preparation of National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute reports, preparation of institutional review board applications, survey development, data collection and entry, community outreach efforts, and developing social marketing materials. Weekly interactive seminars are conducted by leading experts in a wide-range of fields pertaining to Latino health disparities including community health, physiology, health policy, and research methods. Seminar topics are guided by the Diversity and Culture Core Competencies of the Associations of Schools of Public Health (n.d., Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diversity and Culture Core Competencies of the Associations of Schools of Public Health

Trainees are introduced to the process of scientific writing in weekly writing workshops, where they receive mentorship on the process of conceptualizing a research question, identifying appropriate data to address the question, selecting target journals, and drafting a complete manuscript. Trainees are provided with an introductory-level tutorial on the statistical analyses, led by advanced biostatistics graduate student trainees. Each 2-hour weekly workshop is divided into 1 hour of instruction on a particular topic (e.g., drafting a methods section) and 1 hour of feedback where trainees discuss each other’s work and/or receive feedback from their mentors. Trainees also participate in a workshop on developing a poster presentation and are required to present a poster at the end of the summer to faculty and students from the UCLA CPHHD (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

UCLA CPHHD Undergraduate Student Presents His Poster at an Annual Research Symposium on Campus

A major component of the summer training program is fieldwork. Trainees are required to spend at least 40 hours throughout their traineeship in East Los Angeles and/or Boyle Heights directly working with our community partners.

GRADUATE TRAINEESHIP

In addition to the summer training program, the UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program provides traineeships for UCLA CPHHD graduate students during the academic year. Since 2011, seven graduate students have been funded by UCLA CPHHD. Faculty mentors affiliated with UCLA CPHHD have also assisted trainees in efforts to secure additional funding, including National Institutes of Health (NIH) fellowships. In addition to the financial support, the traineeship provides rigorous and comprehensive training for students interested in pursuing Latino health disparities research with a focus on community engagement. The traineeship emphasizes the need for trainees to be independent researchers and encourages them to initiate ancillary projects based on their own research interests, including opportunities to collect data for dissertations. Students are present at all research team and Community Advisory Board (CAB) meetings, and they accompany faculty members to annual UCLA CPHHD conferences at which they are provided opportunities to network with faculty and students from all 10 centers across the country (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Students From an East Los Angeles YMCA Visit UCLA

The UCLA CPHHD also provides graduate students with unique opportunities to actively participate in community-engaged research during the academic year. Trainees are directly involved with the development of instruments, data collection and analyses, implementation and evaluation efforts of the research projects. The traineeship also offers skills in grant writing and dissemination of research findings to a wide-range of audiences including local elected officials and the media. Furthermore, the Training and Career Development Program has mentored students with their applications and presentations for postdoctoral fellowships and junior faculty positions.

POSTDOCTORAL FELLOWS AND JUNIOR FACULTY

The Center has supported four postdoctoral fellows and three junior faculty members in the past 5 years. Of the postdoctoral fellows, three were female; one was non-Latino White, one was Latina, and two were Asian American. All three of the junior faculty members were Latino; two were male and one was female.

For postdoctoral fellows, support has been in the form of stipends, access to project data, and statistical support for publications. The postdoctoral fellows have also been involved in the teaching and mentoring of undergraduate and graduate students. Because the primary goal of the postdoctoral fellowship is to make the fellows more marketable for junior faculty positions (e.g., through writing grants and publishing peer-reviewed articles); the UCLA CPHHD creates an opportunity for them to be independent in pursuing their goals, while at the same time providing mentorship.

For the junior faculty, the UCLA CPHHD has served as an academic home when they have applied for NIH-funded mentored Career Development Award (K) or R01 applications. All three junior faculty members are interested in Latino health disparities. Center faculty mentor the junior faculty and support them academically on publications and grants. The junior faculty members are given the opportunity to interact with the students and fellows in the UCLA CPHHD and at a minimum conduct one lecture in the summer seminar series. All three faculty members have been successful in obtaining NIH funding and publishing in peer-reviewed journals.

CAREER DEVELOPMENT AND GUIDANCE

A major component of the Training and Career Development Program is the guidance and support provided by the faculty to the trainees. All the activities in the UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program are designed to provide experiences and opportunities that inform career choices and support graduate school and professional applications. Faculty provide one-on-one academic advising and career mentoring for each student. However, a major component of the training program is the informal mentoring faculty provide trainees, which has helped prevent student attrition from their academic programs as well as helped cultivate their confidence and self-efficacy to pursue a research career in Latino health disparities. For example, students are provided with support to navigate challenges including pressure from family to return home and/or discontinue their studies in order to obtain full-time employment and/or seek out more lucrative professions.

With the junior faculty in the UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program, the ability to interact with senior faculty who can serve as mentors on an NIH Career Development Award (K) application is crucial for a junior faculty member’s success as an independent investigator. In addition, the UCLA CPHHD Training Program provides a rich, collaborative context for junior faculty to write and publish papers and to be involved in teaching trainees from diverse backgrounds.

RESULTS

Outcome data on the trainees are regularly collected using the metrics tool administered among all 10 of the national CPHHD Training Programs to track graduate student and postdoctoral fellow trainees’ accomplishments (Golden et al., 2015). Preliminary results reflect the accomplishments of trainees as a result of their involvement with the UCLA CPHHD.

The achievements of the high school and undergraduate trainees in our program are noteworthy. For example, in East Los Angeles less than half of the residents (46%) have at least a high school degree (U. S. Census Bureau, 2010). However, among the 60 high school students who participated in the elective course, 50 graduated from high school, demonstrating a 83% graduation rate. Among the high school graduates, 38 continued (or are continuing) with trade school, community college, or 4-year college programs. Five students chose to pursue health-related programs, two enrolled in registered dietician programs and three are studying public health. Qualitative analyses of the students’ experiences revealed that students became effective health advocates in their community and developed skills such as public speaking, video production, social marketing, media literacy, and community organizing as a result of the program (Sharif et al., 2015). Moreover, this initiative introduced them to educational and professional fields they were previously unfamiliar with including public health, marketing, and dietetics (Sharif et al., 2015). To date, two of the undergraduate trainees have completed master of public health programs, one is enrolled in medical school, two are being trained to become registered dieticians, and four are employed on research projects focusing on health disparities.

Graduate student and postdoctoral trainees continue to progress on their dissertations, present at research conferences and collaborate with faculty on manuscripts. The graduate student trainees have been involved with the publication of 18 peer-reviewed journal articles and have completed a total of 28 presentations at scientific conferences. Moreover, one doctoral and two postdoctoral fellows were awarded NIH-grants and four trainees (two doctoral and two postdoctoral) have acquired tenure track faculty positions at institutions across the country.

LESSONS LEARNED

Despite ongoing data collection to evaluate the longer term outcomes of the training program, the UCLA CPHHD team has documented lessons learned that can help inform the design of future training programs. First, not all trainees were able to complete deliverables including preparing a manuscript and a scientific poster. This happened for multiple reasons including insufficient time as well as a mismatch between the trainee’s capabilities and the skill level required for the specific task. For example, the Writers Workshop was modified each year to more appropriately meet the needs of the participating students given that some had no prior experience reading scientific peer-reviewed articles. As a result, the program was modified so that doctoral students-led papers and provided peer mentoring for trainees to complete tasks, including literature reviews, presenting results in tables, and formatting manuscripts for journal submission. This experience helped develop the second lesson learned: Trainees in fact were seeking more guidance than originally anticipated by the UCLA CPHHD faculty. Initially, trainees chose their own research topic, which resulted in unmet deadlines, heightened stress levels and disappointment among trainees. However, based on feedback provided to faculty, the program was adjusted so that students were paired with a faculty member or doctoral students to work on papers-in-progress. Another lesson learned relates to the reality of working on community-engaged research projects. Namely, training programs that place students in community settings should have alternative/back-up plans in place should logistical and/or financial challenges, among both the study team as well as community partners, delay timelines. Another challenge that the faculty and graduate student mentors faced was the limited professional experience some of the more junior trainees, high school students, and undergraduate students. For example, issues of tardiness and absenteeism had to be addressed and were incorporated in the informal mentorship in order to bolster trainees’ level of professionalism. In addition, the peer mentorship yielded varying success largely due to a limitation in the recruitment process. Specifically, incoming graduate students were recruited to serve as mentors for more junior students. However, there were instances in which the graduate student himself or herself lacked research experience to provide an effective mentor–mentee relationship. Finally, training programs focusing on disadvantaged students, such as ours, are faced with the challenge of trainee attrition due to competing demands on their time including familial obligations as well as limited resources such transportation to-and-from their fieldwork placements.

DISCUSSION

Health disparities researchers are needed to not only document and conceptualize disparities facing underserved communities but also to identify, develop, and evaluate potential solutions to eliminate these disparities. Reducing health disparities involves a multi-pronged strategy that includes training a public health workforce with the knowledge and skills to address factors that contribute to health disparities from a wide range of public health professions.

Studies have shown that focusing on trainees from minority backgrounds increases the likelihood that they will return to an underserved community or perform research on health disparities (Ko et al., 2007). Our UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program provides significant faculty “face-time” and mentoring in two major areas: academic advising/career mentoring and scientific support to be successful considering that minority and first-generation college students have much less likelihood of being exposed to academics or the possibility of an academic research-oriented career. Our UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program exposes students to how community health research is conducted and exposes them with the opportunity to better understand academia as a career choice. In addition, our program provides informal support and mentoring that provides a network of peers and faculty who recognize the unique challenges disadvantaged students face in traditional academic settings and who are committed toward providing a safety-net for students to pursue their academic and career goals, both during and beyond the duration of the formal training program.

Entering the health professions workforce, either as practitioners or as researchers, is challenging for minority undergraduate students who are faced with challenges such as inadequate preparation for college-level courses and lack of time management between coursework and extracurricular activities, which often lead to suboptimal grades. In our Training and Career Development Program, our mentors address academic and time management challenges and make the students aware of the requirements to apply for graduate or professional schools. For the undergraduates in particular, the UCLA CPHHD Training and Career Development Program is designed to optimize their success in applying to graduate or professional schools by providing research experiences that they can write about in their personal statements or discuss during interviews, including opportunities to be on posters or peer-reviewed article, as well as providing academic advising and career mentoring. We also consider the community experiences pivotal in guiding students to consider a career in addressing health disparities research. Many students share that working in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights and seeing the impact of “food swamps” (Ortega et al., 2015) on the health of individuals in a community has a lasting impact on their career choice.

We have documented modest success in supporting graduate students to complete their degrees and obtain postdoctoral fellowships or junior faculty positions, and postdoctoral fellows and junior faculty to obtain NIH funding and become independent investigators. Our heavily experiential training provides activities and support for each level of the academic training pathway. Pipeline programs focused on bringing minority trainees into academia and research should consider the amount of faculty time and the appropriate experiences and support necessary to help these trainees be successful at every level, starting as early as high school.

Acknowledgments

All contributors were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health and The California Endowment.

References

- Associations of Schools and Programs of Public Health. MPH core competency model. n.d Retrieved from http://www.aspph.org/educate/models/mph-competency-model/

- Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, … Stamler J. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie GY, Zambrana RE, Garza MA. Exploring risk factors in Latino cardiovascular disease: The role of education, nativity, and gender. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1742–1750. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffus WA, Trawick C, Moonesinghe R, Tola J, Truman BI, Dean HD. Training racial and ethnic minority students for careers in public health sciences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;47(Suppl 5):S368–S375. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden SH, Ferketich A, Boyington J, Dugan S, Garroutte E, Kaufmann PG, … Srinivasan S. Transdisciplinary cardiovascular and cancer health disparities training: Experiences of the centers for population health and health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:395–402. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach K, Mendoza R. Disparities in human resources: Addressing the lack of diversity in the health professions. Health Affairs. 2008;27:413–422. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero AD, Holmes FJ, Inkelas M, Perez VH, Verdugo B, Kuo AA. Evaluation of the pathways for students into health professions: The training of under-represented minority students to pursue maternal and child health professions. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19:265–270. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1620-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden L, Rumala B, Carson P, Siegel E. Promoting careers in health care for urban youth: What students, parents and educators can teach us. Information Services and Use. 2014;34:355–366. doi: 10.3233/ISU-140761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M, Heslin KC, Edelstein RA, Grumbach K. The role of medical education in reducing health care disparities: The first ten years of the UCLA/Drew Medical Education Program. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:625–631. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo AA, Verdugo B, Homes FJ, Henry KA, Vo JH, Perez VH, … Guerrero AD. Creating an MCH pipeline for disadvantaged undergraduate students. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19:2111–2118. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein R. 25 years of promoting diversity in public health leadership: The University of Michigan’s Summer Enrichment Program in health management and policy. Public Health Reports. 2013;128:410–416. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G. Hispanics of Mexican origin in the United States, 2013: Statistical profile. Washington DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2015/09/2015-09-15_mexico-fact-sheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. 2001;89:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Albert SL, Sharif MZ, Langellier BA, Garcia RE, Glik DC, … Prelip ML. Proyecto MercadoFRESCO: A multi-level, community-engaged corner store intervention in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. Journal of Community Health. 2015;40:347–356. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9941-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, … Sims M. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:593–625. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. State and county quick facts. n.d Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/0620802.html.

- U. S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/2010census/

- Sharif MZ, Garza JR, Langellier BA, Kuo AA, Glik DC, Prelip ML, Ortega AN. Mobilizing young people in community efforts to improve the food environment: Corner store conversions in East Los Angeles. Public Health Reports. 2015;130:406–414. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31(1):99–112. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. International Journal of Health Services. 1992;22:429–445. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]