Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this article (PM I) is to describe the rationale for and development of the Pause Marker (PM), a single-sign diagnostic marker proposed to discriminate early or persistent childhood apraxia of speech from speech delay.

Method

The authors describe and prioritize 7 criteria with which to evaluate the research and clinical utility of a diagnostic marker for childhood apraxia of speech, including evaluation of the present proposal. An overview is given of the Speech Disorders Classification System, including extensions completed in the same approximately 3-year period in which the PM was developed.

Results

The finalized Speech Disorders Classification System includes a nosology and cross-classification procedures for childhood and persistent speech disorders and motor speech disorders (Shriberg, Strand, & Mabie, 2017). A PM is developed that provides procedural and scoring information, and citations to papers and technical reports that include audio exemplars of the PM and reference data used to standardize PM scores are provided.

Conclusions

The PM described here is an acoustic-aided perceptual sign that quantifies one aspect of speech precision in the linguistic domain of phrasing. This diagnostic marker can be used to discriminate early or persistent childhood apraxia of speech from speech delay.

Contemporary research in speech sound disorders (SSD) includes studies to identify, explicate, and treat the genomic, neurocognitive, and neuromotor substrates of childhood apraxia of speech (CAS; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2007; Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America, 2013; Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists [RCSLT], 2011; Shriberg & Campbell, 2002). Perhaps the most significant barrier to research progress in developing a neural marker of CAS and an account of its pathobiology—with implications for prevention and treatment—is the lack of a conclusive behavioral diagnostic marker of CAS. In particular, to date, there is no operationalized and standardized behavioral marker of CAS available with which to discriminate speakers with mild to severe CAS in idiopathic, neurogenetic, neurological, or complex neurodevelopmental contexts from speakers with speech delay (SD) or speakers with other pediatric motor speech disorders (MSD). A marker with such properties to use as the inclusionary criterion in CAS research requires psychometric support for its diagnostic accuracy and empirical support for its theoretical coherence with the speech processing deficits proposed to define CAS. The research reported in the present article (PM I), in PM II (Shriberg et al., 2017a), and in PM IV (Shriberg et al., 2017c) addresses the former needs, with findings in PM III (Shriberg et al., 2017b) assessing the latter need for theoretical coherence. The following review includes relevant terms and concepts in classification, speech processes, and diagnostic marker research in CAS.

Diagnostic Markers of SSD

Definition of Diagnostic Markers

The term diagnostic marker is one of many adjective–noun options used in the classification of diseases and disorders (e.g., adjectives: behavioral, biochemical, clinical, diagnostic, neural, research; nouns: characteristic, feature, marker, phenotype, sign). We define a diagnostic marker of a disorder as “one or more operationalized and standardized signs with sensitivity to and specificity for persons with prior, present, and/or future expression of the disorder at estimated levels of accuracy.” Some diagnostic markers may have only categorical properties (i.e., presence/absence of disorder), whereas markers that meet distributional criteria for ordinal or interval measurement levels may also be used to scale the severity of a disorder (see PM IV; Shriberg et al., 2017c). As defined herein, positive status for a conclusive behavioral diagnostic marker is the ideal inclusionary criterion on which researchers can base the identification and development of biomarkers for diseases or disorders.

Attributes of Diagnostic Markers

Table 1 includes seven attributes of a diagnostic marker that are posited to determine its value for research and clinical application. The seven proposed attributes or measurement constructs in the left-most column are ordered by rank, vertically highest to lowest, by their hypothesized theoretical and psychometric importance in research and practice. The following observations focus on the implications of each attribute for the present context. The information in Table 1 comprises the criteria on which the diagnostic marker of CAS to be described in the present research will be evaluated.

Table 1.

Seven attributes of highly valued diagnostic markers.

| Construct | Premise | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The higher the diagnostic accuracy of a diagnostic marker, the more highly valued it is in research and clinical settings. | Diagnostic markers deemed conclusive for a disorder require > 90% sensitivity and > 90% specificity, yielding positive and negative likelihood ratios of at least 10.0 and at most 0.10, respectively. |

| Reliability | The higher the reliability of a diagnostic marker, the more highly valued it is in research and clinical settings. | Reliable diagnostic markers have robust point-by-point intrajudge and interjudge data reduction agreement and internal and test–retest stability of scores, each estimated across relevant participant heterogeneities. |

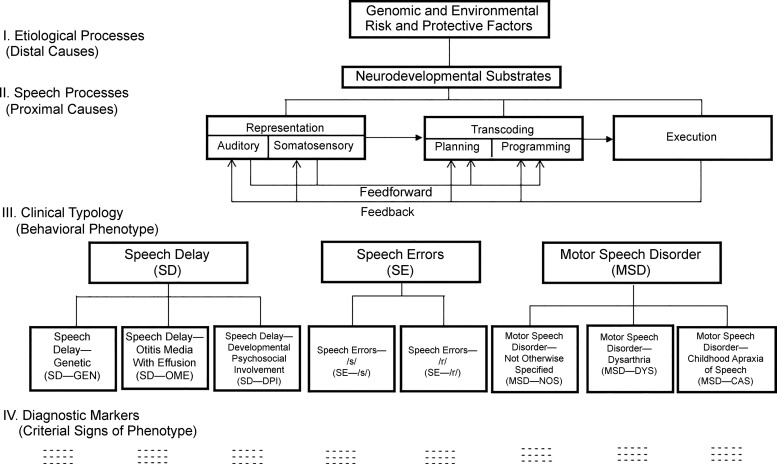

| Coherence | The greater the theoretical coherence of a diagnostic marker, the more highly valued it is in research and clinical settings. | As portrayed in Figure 1, conclusive diagnostic markers (Level IV) for each of the putative speech sound disorder subtypes (Level III) are highly valued for integrative descriptive–explanatory accounts when tied to their genomic, environmental, developmental, neurocognitive, and sensorimotor substrates (Levels I and II). |

| Discreteness | Diagnostic markers from discrete, on-line events are more highly valued than diagnostic markers derived from off-line tallies of events. | Speech signs that that can be spatiotemporally associated with neurological events have the potential to inform explanatory accounts of speech-processing deficits. |

| Parsimony | The fewer the number of signs in a diagnostic marker, the greater is its theoretical parsimony and psychometric robustness. | Each sign required for a diagnostic marker adds theoretical complexity and requires additional, multiplicative psychometric stability. |

| Generality | The more extensive the generality of a diagnostic marker, the more highly valued it is in research and clinical settings. | Diagnostic markers with the most extensive external validity may be used to quantify risk for future expression of disorder, expression of active disorder, and postdict severity of prior disorder. |

| Efficiency | The greater the efficiency of a diagnostic marker, the more highly valued it is in research and clinical settings. | More highly valued markers require the fewest tasks, equipment, examiner proficiencies, and participant accommodations and the least time and costs to administer, score, and interpret. |

Accuracy

As shown in Table 1, the most highly valued diagnostic marker of CAS is proposed to be the one with both the highest sensitivity to speakers who previously, currently, and/or are predicted to express CAS (i.e., true positives), and the one with the highest specificity to exclude speakers without any of these histories (i.e., true negatives). Of the two psychometric challenges, demonstrating high sensitivity to true positive CAS may be the more challenging one. The choice of a diagnostic standard against which to estimate the sensitivity of the diagnostic marker of CAS is a design decision that is based on a number of theoretical and practical considerations, which will be discussed herein. In contrast, valid estimates of the specificity of a proposed marker depend primarily on the accuracy with which participants in the comparison group or groups have been classified. Later discussion of the sensitivity and specificity findings for the diagnostic marker of CAS, termed the Pause Marker, (PM) will return to these issues, including the psychometric criteria used to define conclusive sensitivity and specificity.

Reliability

In addition to diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic markers are required to demonstrate sufficient reliability for each measurement in the process leading to an individual's classification or score on the marker. A challenge for the development of a diagnostic marker of CAS is the level of measurement accuracy needed in data reduction (i.e., in the present research, glossing continuous speech, narrow phonetic transcription, prosody–voice coding, acoustic segmentation and measurement), and including adequate reliabilities in these domains for each sign proposed to be included in the marker. Reliability (and efficiency; see Table 1) goals in measurement projects such as the present one are to instrument and automate as many data reduction operations as possible. The diagnostic marker to be described requires acoustics-aided auditory and visual perceptual judgments, with additional research needed to determine if instrumentation and automatic speech recognition methods can replace at least some elements of each of the current perceptually based measurement tasks.

Coherence

The Speech Disorders Classification System (SDCS) framework, to be discussed in the next section, takes the position that speech, prosody, and/or voice signs that meet psychometric criteria for a diagnostic marker of one of the eight subtypes of SSD described in Figure 1 require theoretical coherence. In other words, proposed markers must be coherent with the speech processing deficit(s) posited to be consequent to neurogenetic and environmental causal substrates. PM III (Shriberg et al., 2017b) reports findings from studies that address this question for the diagnostic marker of CAS described in the present article. The major goal of the PM development to be described here, specifically, inappropriate between-words pauses, termed abrupt inappropriate pauses, was to provide a theoretically coherent behavioral marker of biological events that could eventually be instrumented to provide a quantitative biomarker of CAS.

Figure 1.

The Speech Disorders Classification System.

Discreteness

A fourth premise in Table 1 is that the most highly valued diagnostic markers are obtained from discrete, on-line events, rather than from metrics aggregated off-line. For example, a vocal tremor during a vowel is a discrete behavioral event for which the neuromotor correlates can be quantified using instrumental methods. In contrast, constructs such as reduced intelligibility, reduced articulatory precision, or increased articulatory instability include contributions from many language, speech, prosody, and voice domains typically requiring off-line data reduction and aggregation across domains.

Parsimony

Checklists and other multisign diagnostic markers may obscure the relative contributions of each constituent sign's explanatory power within and among individuals; for example, two persons with the same number of positive signs on a checklist meeting criteria for positive classification can have markedly dissimilar profiles of positive signs. Although individual profiles of signs of a disorder are informative for descriptive–explanatory goals, the premise in Table 1 is that single-sign diagnostic markers have the advantage of parsimony (i.e., they minimize both the conceptual confounds and the psychometric constraints associated with multisign markers). Notice that this issue is constrained to diagnostic markers, not discussions about such issues as whether CAS is best understood as a domain-specific MSD or a multidomain disorder involving cognitive and motor deficits. Some of these issues are addressed in PM III (Shriberg et al., 2017b), and others issues, such as whether CAS is best understood as a spectrum or unitary disorder, go beyond the scope of the present research series.

Generality

In addition to diagnostic markers that identify persons currently expressing a disorder or disease, precision (also termed personalized) medicine seeks early identification of persons with subclinical disorder or persons who are at risk for a disorder. A strength of the PM diagnostic marker described here is that it is not based on articulatory, prosodic, or phonatory competence, which, by definition, leaves little error variance after developmental mastery; rather, it is presumed to be essentially unrelated to developmental milestones and not moderated or mediated by sociodemographic variables (e.g., age, sex, dialect). Therefore, if validated and eventually cross-validated, the PM should also be required to meet several criteria for generality. It should provide a metric with which to identify, quantify, and track changes in the expression of CAS.

Efficiency

Diagnostic markers that require the least effort, time, skills, and financial resources in clinical and research environments are highly valued. The marker described here is posited to be efficient because the continuous speech sample required to obtain the speech data may also be used to obtain language, voice, and/or fluency data. However, continuous speech samples are inefficient in a number of ways. Children with limitations in intellectual function, language comprehension, language production, phonetic inventories, or interest in conversing may not produce a sufficient number of usable words to meet minimum requirements for a valid speech sample. The marker to be described also requires a number of perceptual and acoustic skills in data reduction and the time to complete a number of data reduction tasks using these methods. Automated data collection, data reduction, data scoring, and data analysis should provide increased efficiencies.

Four Sources for Diagnostic Markers of CAS

Descriptive or evaluative review of contemporary diagnostic markers purported to identify CAS is beyond the scope of the present article. It is useful to provide brief overviews of the four sources currently used to identify speakers suspected to test positive for CAS.

Diagnostic Checklists

The most frequent inclusionary requirement for speakers with apraxia of speech is criterion performance on a required number of speech, prosody, and/or voice signs purported to be diagnostic of apraxia, as sampled in a required number and type of tasks (e.g., Murray, McCabe, Heard, & Ballard, 2015) and, more recently, operationalized (e.g., Iuzzini-Seigel, Hogan, Guarino, & Green, 2015). As indicated previously, a primary constraint in CAS research is the lack of consensus on the number and type of operationally defined and standardized signs necessary and sufficient to be sensitive to and specific for CAS. Diagnostic checklists attempt to support three premises about the speech, prosody, and voice profiles of speakers suspected to be true positives for CAS: (a) Their error profiles differ from the well-described profiles of speakers with speech delay, (b) their error profiles differ from the error profiles of speakers with subtypes of pure and mixed dysarthrias, and (c) their error profiles are at least in part similar to those of speakers with adult-onset apraxia of speech (AAS).

Table 2 is an example of a 10-sign checklist for CAS. The studies to be reported in other articles in this series use classification outcomes from this diagnostic checklist as the diagnostic standard against which to estimate the diagnostic accuracy of the marker to be described. The second author developed the checklist entries and quantitative criteria to classify a speaker as positive for CAS in the context of genetic and other studies in CAS in complex neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., Laffin et al., 2012; Raca et al., 2013; Rice et al., 2012; Shriberg, Potter, & Strand, 2011; Worthey et al., 2013). As shown in Table 2, the 10 signs are organized using an analytic framework termed the Ten Linguistic Domains Analytics (TLDA; Shriberg et al., 2010a). TLDA divides behavioral signs of SSD into three classes of segmental signs (vowels, consonants, and vowels and consonants), three classes of prosody signs (phrasing, rate, and stress), and four classes of voice signs (loudness, pitch, laryngeal quality, and resonance). Auditory–perceptual methods are used to identify the occurrences of each sign in the checklist. To be classified as positive for CAS, a speaker must meet auditory–perceptual criteria for at least four signs in at least three of the speech tasks on the research protocol to be described.

Table 2.

Pediatric adaptation of the Mayo Clinic System (MCS) to classify childhood apraxia of speech (CAS).

| Ten Linguistic Domains Analytics | Motor Speech Disorder–Childhood Apraxia of Speech | |

|---|---|---|

| Segmental | 1. Vowels | 1. Vowel distortions |

| 2. Consonants | 2. Voicing errors | |

| 3. Vowels and consonants | 3. Distorted substitutions | |

| 4. Difficulty achieving initial articulatory configurations or transitionary movement gestures | ||

| 5. Groping | ||

| 6. Intrusive schwa | ||

| 7. Increased difficulty with multisyllabic words | ||

| Suprasegmental | ||

| Prosody | 4. Phrasing | 8. Syllable segregation |

| 5. Rate | 9. Slow speech rate and/or slow diadochokinetic rates | |

| 6. Stress | 10. Equal stress or lexical stress errors | |

| Voice | 7. Loudness | |

| 8. Pitch | ||

| 9. Laryngeal quality | ||

| 10. Resonance | ||

Note. Signs are organized using the Ten Linguistic Domains Analytics (TLDA) in the Speech Disorders Classification System (Shriberg et al., 2010a). To be classified as positive for CAS using the MCS, a speaker is required to meet criteria for at least 4 of the 10 listed signs occurring in at least 3 of the 17 speech tasks in the Madison Speech Assessment Protocol (Shriberg et al., 2010a).

Tests and Tasks

A second source of available and emerging methods used to identify speakers with CAS across the life span is to use one or more procedures that fully or partially meet psychometric criteria for a standardized test or task (e.g., McCauley & Strand, 2009; Sayahi & Jalaie, 2016; Strand, McCauley, Weigand, Stoeckel, & Baas, 2013). Although reviews of tests to identify CAS consider some of the seven attributes of a highly valued diagnostic marker proposed in Table 1, most narrative and evidenced-based test reviews focus primarily or only on a test's accuracy (i.e., validity), reliability, and efficiency (Sayahi & Jalaie, 2016). Although there are a number of measures that purport to identify and scale the severity of AAS (Duffy, 2013), there currently is not discipline consensus on one or more tests or tasks for the identification of CAS.

Research Studies to Develop or Validate a Diagnostic Marker of CAS

The lack of a conclusive diagnostic marker for CAS requires researchers to use a patchwork of findings and professional recommendations—often diagnostic marker recommendations in a 10-year-old position statement (ASHA, 2007)—to justify the inclusionary and exclusionary participant criteria for CAS research. Markers associated with deficits in lexical and sentential stress (e.g., Shriberg et al., 2003; Skinder, Connaghan, Strand, & Betz, 2000; Skinder, Strand, & Mignerey, 1999) and central deficits associated with a number of speech-processing constructs (e.g., timing: Alcock, Passingham, Watkins, & Vargha-Khadem, 2000; Peter & Stoel-Gammon, 2008; sequential processing: Button, Peter, Stoel-Gammon, & Raskind, 2013; Peter, Button, Stoel-Gammon, Chapman, & Raskind, 2013; and movement variability: Grigos, Moss, & Lu, 2015) have been reported. To date, there are no reports of behavioral or neural CAS markers for which both sensitivity and specificity estimates are above 90% (Shriberg, 2013; Shriberg & Strand, 2014).

Nonhuman Vocal Learner Literature

In addition to checklists, tests/tasks, and diagnostic signs research, a fourth potentially informative source that can be used to develop diagnostic markers for CAS is in the increasingly informative nonhuman vocal learners literature. A factor of particular interest is the potential for biomarkers of CAS that are based on vocal learning modeled across mammalian and avian species. Sample useful reviews include Colbert-White, Corballis, and Fragaszy (2014); Condro and White (2014); Fessenden (2014); Fisher and Ridley (2013); Ghazanfar and Eliades (2014); Janik (2014); Knörnschild (2014); Konopka and Roberts (2016); Reichmuth and Casey (2014); Prather, Okanoyo, and Bolhuis (2017); Stoeger and Manger (2014); Tschida and Mooney (2012); and Vernes (2016).

Classification of SSD

The SDCS

Figure 1 is a clinical–research framework for pediatric speech sound disorders, which has been in development for several decades, termed the Speech Disorders Classification System. In 2017, the SDCS was finalized to include measures and methods with which to cross-classify SD and MSD (Shriberg, Strand, & Mabie, 2017). The present Figure 1 does not include these updates, which are not relevant in this present context. It is useful first to review the basic terms and concepts of the SDCS, followed by a description of the recent measurement extensions.

The four Levels (I–IV) in the SDCS framework are posited to comprise the clinical–research space in SSD (Shriberg, 2010). The conceptual focus of the study series is on the generic framework at Level II that links proximal speech-processing deficits in CAS with (a) distal causal–explanatory pathways of CAS at Level I, (b) a clinical nosology that includes CAS at Level III, and (c) a proposed diagnostic marker of CAS at Level IV. The present series of articles addresses the need for a diagnostic marker at SDCS Level IV for the clinical entity at Level III termed motor speech disorder–childhood apraxia of speech (hereafter CAS). As shown in Figure 1, the diagnostic marker proposed to discriminate CAS from SD is termed the Pause Marker.

SDCS Level I

SDCS Level I posits genomic, neurocognitive, sensorimotor, and environmental risk and protective variables associated with individual and multiple causal pathways to each of the three classes and eight subtypes of SSD proposed in the clinical nosology at Level III. Literature reviews of relevant research on risk factors and causal pathways to SSD are beyond the scope of the present article. A sample of useful reviews of findings relevant for CAS in the genomic, functional neurobiology, and speech motor control literatures includes Ackermann, Hage, and Ziegler (2014); Barnett and van Bon (2015); Deshpande and Lints (2013); Fiori et al. (2016); Fisher and Scharff (2009); French and Fisher (2014); Fuertinger, Horwitz, and Simonyan (2015); Graham, Deriziotis, and Fisher (2015); Graham and Fisher (2013); Hoogman et al. (2014); Kent (2000); Kent and Rosenbek (1983); Kumar, Croxson, and Simonyan (2016); Liégeois, Mayes, and Morgan (2014); Liégeois and Morgan (2012); Liégeois, Morgan, Connelly, and Vargha-Khadem (2011); Liégeois et al. (2016); Mayes, Reilly, and Morgan (2015); Morgan, Bonthrone, and Liégeois (2016); Morgan, Fisher, Scheffer, and Hildebrand (2016); Nudel and Newbury (2013); Ramus and Fisher (2009); Terband, Maassen, Guenther, and Brumberg (2014); Vernes et al. (2011); and Ziegler, Aichert, and Staiger (2012). A longer term goal of the present research is to contribute to the database linking diagnostic marker findings (Level IV) to genomic and neural substrates of the functional biology of CAS (Level I).

SDCS Level II

Whereas SDCS Level I addresses distal pathway deficits in SSD, Level II includes potential loci for their proximal consequences on speech processing in SSD. This psycholinguistic framework divides speech production into seven elements, with deficits in any one or more element representing a potential origin of one of the three classes and eight subtypes of SSD to be described next. The seven elements are wholly underspecified in the context of the diverse perspectives within and among the research disciplines that contribute proposed descriptive–explanatory accounts of the subtypes of SSD shown in Level III. Putative stage-based frameworks such as the one portrayed in Figure 1 clearly are not consistent with all classical and contemporary speech-processing proposals. The framework was designed to accommodate at least the primitives of the most influential proposals in the CAS literature and the considerably larger literature in AAS. The closest precedent for a clinical–research framework in the pediatric speech-pathology literature is the psycholinguistic model proposed by Stackhouse and colleagues (Pascoe, Stackhouse, & Wells, 2005; Stackhouse & Wells, 1997, 2001).

As shown in Figure 1, representational-stage speech processes for the present purposes include all speech processes prior to planning/programming. These include the auditory–perceptual, somatosensory, and (not shown) memory processes (e.g., Lewis et al., 2011; Waring, Eadie, Liow, & Dodd, 2017) used to encode, store, and retrieve representations (words, syllables, phonemes), and to assign lexical stress. They also include the feedforward of representational information and the feedback of information from speech execution.

We have proposed transcoding as a cover term for speech planning and programming, primarily to accommodate the lack of a consensus on the processing domains of each term within and among basic and applied disciplines in speech motor control (Lohmeier & Shriberg, 2011; Shriberg, Lohmeier, Strand, & Jakielski, 2012). In the CAS literature, the terms planning and programming are often used either interchangeably or collectively, with the latter using the iconic, noncommittal slash convention (i.e., planning/programming). We follow van der Merwe's (1997, 2009) influential proposal in which planning identifies the motor goals and structures to achieve them, and programming provides the muscle-specific requirements, including tone, movement velocity, force, and range. Because the present methods are not instrumented to differentiate such differences between planning and programming at neuromuscular levels of observation, segmental and suprasegmental findings from this research cannot be marshaled in support of one or both deficits in CAS. Post-transcoding processes as shown in Figure 1 include execution and feedback processes. As indicated previously, PM III (Shriberg et al., 2017b) tests several hypotheses about core speech-processing deficits in CAS using participant data from the marker described in this article and from other measures of speech and prosody.

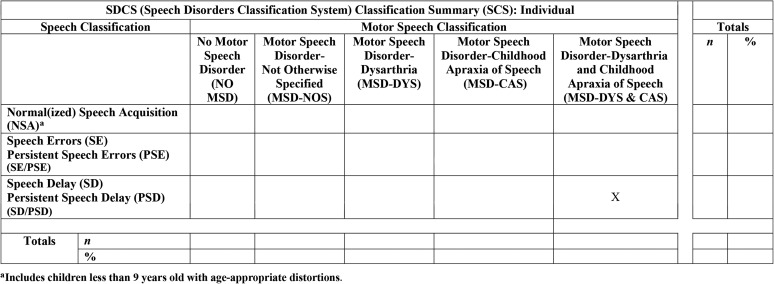

SDCS Level III

The central premise of the SDCS is that, as with all disorders, productive research and effective treatment of SSD require a standardized and well-validated nosology. The SDCS divides SSD into the three classes and eight subtypes, as shown in Figure 1. A child's speech and motor speech classification may, of course, change over time; for example, a child might meet SDCS criteria for one or more of the three subtypes of SD shown in Figure 1, but that child may later be classified as having persistent speech errors (PSE). As discussed in the update to the SDCS, such historical information may be crucial to obtain for some questions (e.g., genetic studies). Also, as discussed later, a speaker's status on speech and motor speech domains should be cross-classified, rather than represented in the linear perspective suggested in the schema shown in Figure 1. For example, most, but not all, children and adolescents who meet diagnostic criteria for CAS also meet SDCS criteria for SD or persistent SD (age-inappropriate speech sound deletions and/or substitutions), with or without language impairment. Older speakers may have normalized CAS and/or SD.

SDCS Level IV

The abbreviations and acronyms under each of the eight putative subtypes of SSD are currently signs and measures used to identify each subtype, with a long-term goal of the SDCS being to use behavioral markers to aid in identifying biomarkers of each subtype. Classifications on the basis of diagnostic ontologies are increasingly important as one type of phenotype in informatics approaches (e.g., Shimoyama et al., 2012).

SD. The speech-processing differences among the three potential causal pathways to SD shown in Figure 1 (speech delay—genetic, speech delay—otitis media with effusion, and speech delay—developmental psychosocial involvement; Shriberg, 2010; Shriberg et al., 2010a) are not directly relevant to the question posed in this report. The dashed rather than solid lines around each proposed subtype signify our present view of these origins as non–mutually exclusive “risk factors” for SD, rather than as exclusive subtypes. The dashes under each proposed subtype indicate that research to date has not produced conclusive or near-conclusive diagnostic markers for the proposed subtype.

The major issue to underscore in this section, as indicated in the title of this series, is that children with significant idiopathic speech delay appear increasingly to be incorrectly classified as having CAS (or with a provisional term such as “suspected CAS”). Reviews of clinical studies in several countries indicate false positive CAS rates ranging from approximately 50% to approximately 90% (ASHA, 2007; RCSLT, 2011), and informal analyses of the increasing numbers of Internet discussions and postgraduate clinical training opportunities in CAS support such findings. The implications of misdiagnosis for treatment issues are significant. Among the seven generic speech-processing elements shown in Figure 1, Level II, proximal SD deficits, are posited to be in one of two elements: delayed acquisition of correct auditory–perceptual or somatosensory features of underlying representations and/or delayed development of the feedback processes required to fine tune the precision and stability of segmental and suprasegmental production to ambient adult models. Treatment studies support the efficacy of an array of interventions to help children develop the level of phonological awareness, verbal short-term memory, and other neurocognitive requisites to instantiate correct and stable auditory–perceptual and somatosensory representations and to generalize learning across relevant representational domains (e.g., features, phonemes, syllables, words, lexical stress; Rvachew & Brosseau-Lapré, 2012). As discussed presently, proximal CAS deficits are posited to be significantly more complex.

SE. The class of SSD termed SE includes children who have histories of feature-limited speech sound distortions, generally on the most challenging manner classes of speech sounds in a language (e.g., fricatives, affricates, liquids), which for some speakers may persist for a lifetime with or without treatment (Boyce, 2015; Flipsen, 2015; Klein, Byun, Davidson, & Grigos, 2013; Preston & Edwards, 2007, 2009; Preston, Hull, & Edwards, 2013; Shriberg, Gruber, & Kwiatkowski, 1994; Sjolie, Leece, & Preston, 2016; Van Borsel, Van Rentergem, & Verhaeghe, 2007; Wren, Miller, Peters, Emond, & Roulstone, 2016; Wren, Roulstone, & Miller, 2012; Zharkova, 2016). There is research support for sociodemographic differences between children who have experienced the across-the-board, age-inappropriate deletion and substitution errors that define SD (e.g., differences in sex; Shriberg, 2010) and children whose speech errors include only the feature-limited distortion errors that define SE.

As noted previously, a nosological confounding factor is that speakers older than approximately 9 years who are classified as having residual or persistent distortion errors may have histories of either SD or SE (e.g., Shriberg, Flipsen, Karlsson, & McSweeny, 2001; Shriberg et al., 1994). In an acoustic study series of SE, the persistent /s/ and /r/ distortions of adolescents with SE histories were more severe than the residual /s/ and /r/ distortions of adolescents with prior SD (Flipsen, Shriberg, Weismer, Karlsson, & McSweeny, 1999, 2001; Karlsson, Shriberg, Flipsen, & McSweeny, 2002). These findings may imply differences between developmental and normalization goals in representational and feedback processes underlying SE versus SD over time. In particular, the studies cited speculated that the distortion errors of the children with the SE histories may have been more resistant to normalization because these children had made these distortions since the earliest period of speech development, whereas the children with SD deleted these target sounds and/or substituted others for them earlier in speech development. The implications for treatment of this perspective is that deficits in auditory and somatosensory feedback processes may be less effective for children with histories of SE than for children with histories of SD. It is clear that there are many testable hypotheses about the interactive effects of strengths and deficits in each of the seven speech processes in Level II in the development and persistence of distortion errors in children with histories of SD compared with those with histories of SE.

MSD. The third proposed class of SSD in the SDCS includes three subtypes termed motor speech disorder—not otherwise specified (MSD-NOS), motor speech disorder—dysarthria (MSD-DYS), and motor speech disorder—childhood apraxia of speech (MSD-CAS). The three subtypes of childhood MSD are arranged left to right in Figure 1 in order of their estimated increasing severity of involvement and corresponding decreasing prevalence in complex neurodevelopmental disorders.

MSD-NOS is a provisional classification for speakers with age-inappropriate deficits in the precision and stability of speech, prosody, and voice that differ from the segmental and suprasegmental errors present in speakers with the three subtypes of SD, but they do not meet criteria for dysarthria or CAS. Examples of studies using varied terms and concepts to describe such children are cited in Shriberg et al. (2010a); more recent articles include Peter, Matsushita, and Raskind (2012); Redle et al. (2015); Rupela, Velleman, and Andrianopoulos (2016); and Vick et al. (2014). An index of spatiotemporal precision and stability developed to identify speakers with MSD-NOS and reference data on the measure are described elsewhere (Mabie & Shriberg, 2017; Shriberg, Strand, & Mabie, 2017).

A second subtype of pediatric motor speech disorder, MSD-DYS, is posited to include the same subtypes of dysarthria as those classically defined for speakers of all ages in the Mayo Clinic System (MCS; Duffy, 2013). It is beyond the scope of the present article to review the many classification issues and alternative proposals to the MCS for the pediatric dysarthrias (e.g., Hodge, 2013; Morgan & Liégeois, 2010; van Mourik, Catsman-Berrevoets, Paquier, Yousef-Bak, & van Dongen, 1997; Waring & Knight, 2013; Weismer, 2006, 2007; Weismer & Kim, 2010).

The primary focus in the present article is on the specificity of a proposed diagnostic marker of MSD-CAS relative to SD, with additional data gathered to support its specificity relative to MSD-NOS and MSD-DYS. As described, MSD-NOS is a new classification for which there is no comparison group on which to test the discriminant validity of the PM for CAS to be described here. Also, to the date of publication of this series, we have not completed an analysis of PM findings in groups of children or adults with well-documented subtypes of dysarthria. The specificity of the PM relative to dysarthria has been supported, however, in associated emerging studies of speakers with complex neurological disorders who have substantial rates of five types of dysarthria. A review of these studies is presented in the next section on extensions to the SDCS.

MSD-CAS includes speakers with an inherited or sporadic congenital form of apraxia of speech or an apraxia of speech due to a neurological insult during the speech acquisition period, nominally birth to 9 years of age. Congenital or childhood onset of CAS may occur idiopathically or in the context of a complex neurodevelopmental disorder. The consensus in the AAS literatures is that the behavioral signs of AAS are consistent with deficits in transcoding linguistic representations into the movement commands for speech (Liss, 1998; Maas & Mailend, 2012; Schneider & Frens, 2005; Terband, Maassen, Guenther, & Brumberg, 2009; van der Merwe, 2009). As described presently, we posit that one “moment” of apraxia—a point in talking when pre-execution commands are not sufficient to continue speaking—includes an inappropriate pause due to transcoding deficits in both representational and motor speech processes. Although origins of such deficits in CAS and AAS differ in pathobiology, we take the position that the two forms of apraxia of speech share generally similar speech processes, with more recent emphasis in the developmental form of apraxia of speech also placed on the processing of feedforward information (e.g., Iuzzini-Seigel et al., 2015; Nijland, Maassen, & van der Meulen, 2003; Preston et al., 2014; Terband et al., 2009; Terband & Maassen, 2010).

The Finalized Version of the SDCS

As described previously, the SDCS uses standardized measures and indices to profile a speaker's competence, precision, and stability of speech, prosody, and voice (Shriberg et al., 2010a, 2010b). Perceptual and acoustic data analyses in the present study used the methods in these articles and additional reference databases of speakers with typical speech and SD to study genetic and neurodevelopmental substrates of pediatric speech and MSD (e.g., Laffin et al., 2012; Peter et al., 2016; Raca et al., 2013; Rice et al.; 2012; Shriberg, Paul, Black, & van Santen, 2011; Shriberg, Potter, & Strand, 2011; Worthey et al., 2013). Since the two 2010 methodological reports and the latter substantive articles, extensions of the SDCS have been developed to finalize the speech and motor speech classifications. This research has been conducted during the same time period as development of the PM described in the following section titled “Development of the PM.” It is useful to precede that description with a brief summary of extensions to the SDCS, particularly as they describe research to differentiate MSD-CAS from MSD-DYS.

Table 3 provides information on the five speech classifications, the five motor speech classifications, and the five dysarthria subtype classifications in the finalized version of the SDCS. The references in the right-most column include the operationalized and standardized perceptual and acoustic diagnostic markers used to classify each type and subtype of SD and MSD. The five, mutually exclusive SD classifications are consistent with contemporary nosology in childhood SSD (e.g., Bernthal, Bankson, & Flipsen, 2013; Bowen, 2015; Dodd, 2005; McLeod & Baker, 2017; Rvachew & Brosseau-Lapré, 2012). As indicated previously, the revised SDCS now includes classifications for PSE and persistent speech delay (PSD) where needed and totalized when the distinction is not relevant. Thus, at the time of assessment a child is classified as one of the five mutually exclusive speech classifications shown in the rows in Table 3.

Table 3.

Speech classifications, Motor Speech classifications, and Dysarthria Subtype classifications in the Speech Disorders Classification System (SDCS). The five Speech classifications are mutually exclusive, as are the five Motor Speech classifications. The five subtypes of dysarthria classifications are not mutually exclusive. That is, a speaker can meet percentile criteria for more than one of the five listed dysarthria subtype classifications (i.e., mixed dysarthria).

| Speech Disorders Classification System (SDCS) |

Age (yrs;mos) at Assessment | Description | Reference a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classes, Types, and Subtypes | Abbreviation | |||

| Five Speech Classification Types | ||||

| Normal(ized) Speech Acquisition | NSA | 3–80 | Does not meet criteria for any of the four Speech Disorder classifications. Includes children 3-8 years old with only distortion errors | 2, 3, 4 |

| Speech Errors | SE | 6–8;11 | Age-inappropriate speech sound distortions | 3, 4 |

| Persistent Speech Errors | PSE | 9–80 | Age-inappropriate speech sound distortions that persist past 9 years of age | 4, 5 |

| Speech Delay | SD | 3–8;11 | Age-inappropriate speech sound deletions and/or substitutions | 3, 4 |

| Persistent Speech Delay | PSD | 9–80 | Age-inappropriate speech sound deletions and/or substitutions that persist past 9 years of age | 3, 4, 5 |

| Five Motor Speech Classification Types | ||||

| No Motor Speech Disorder | No MSD | 3–80 | Does not meet criteria for any of the four Motor Speech Disorder classifications | 2, 7 |

| Motor Speech Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified | MSD-NOS | 3–80 | Meets Precision-Stability Index (PSI) criterion for MSD-NOS | 2, 7 |

| Motor Speech Disorder-Dysarthria | MSD-DYS | 3–80 | Meets Dysarthria Index (DI) and Dysarthria Subtype Indices (DSI) criteria for MSD-DYS | 2, 7 |

| Motor Speech Disorder-Childhood Apraxia of Speech | MSD-CAS | 3–80 | Meets Pause Marker (PM) criteria for MSD-CAS | 6, 7 |

| Motor Speech Disorder-Dysarthria & Childhood Apraxia of Speech | MSD-DYS & CAS | 3–80 | Meets SDCS criteria for MSD-DYS & MSD-CAS | 2, 7 |

| Five Dysarthria Subtypes | ||||

| Ataxic | 3–80 | Cerebellar disorder | 1, 2 | |

| Spastic | 3–80 | Upper motor neuron disorder | 1, 2 | |

| Hyperkinetic | 3–80 | Basal ganglia disorder; increased movement | 1, 2 | |

| Hypokinetic | 3–80 | Basal ganglia disorder; decreased movement | 1, 2 | |

| Flaccid | 3–80 | Lower motor neuron disorder | 1, 2 | |

Table 3 also cross-classifies a speaker's speech classification with his or her classification status on five mutually exclusive motor speech classifications. As shown in the columns, these classifications include a category for speakers who do not meet criteria for any MSD (No MSD), and classifications for MSD-NOS, MSD-DYS, MSD-CAS, and MSD-DYS & CAS. MSD-NOS is the classification for speakers meeting criteria for only this classification; speakers who meet criteria for NOS and one of the other three MSD classifications are classified in this category.

The Dysarthria Index and Dysarthria Subtype Indices

Last, for speakers who meet the classification criteria for MSD-DYS or MSD-DYS & CAS, an additional set of indices determines which one or more of the five subtypes of dysarthria shown in Table 3 has or have the most assessment support. It is useful for the present description to include a copy of the SDCS dysarthria measure used to identify dysarthria and possibly subtypes and a copy of an example cross-classification matrix. Table 4 includes the 34 perceptual and acoustic signs of dysarthria that comprise the Dysarthria Index (DI) and the five subtype indices of dysarthria termed the Dysarthria Subtype Indices (DSI; Mabie & Shriberg, 2017; Shriberg & Mabie, 2017; Shriberg, Strand, & Mabie, 2017). As shown in Table 4, the DI yields a percentage score that is based on the number of positive signs of dysarthria subtracted from 100%, so that low scores indicate more involvement. Each of the five DSI includes from 10 to 19 diagnostic signs. Following Duffy's (2013) weightings of the signs' contribution to differential diagnosis of each dysarthria subtype (one or two “pluses” in Duffy's tables), each sign contributes 1 or 2 points to a total score for each index. As in the DI, the total score is subtracted from 100, so that low-percentage scores indicate more severe involvement. Mabie and Shriberg (2017) included rationale and psychometric findings for the ways in which the DI and DSI percentage data and percentile standardization procedures are used to make DI and DSI classifications.

Table 4.

The Dysarthria Index and the five Dysarthria Subtype Indices.

| Ten linguistic domains | No. | Dysarthria Index (DI) speech, prosody, and voice changes | Assessment mode

a

|

Five Dysarthria Subtype Indices (DSI)

b

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | A | Ataxic | Spastic | Hyperkinetic | Hypokinetic | Flaccid | |||

| Vowels | 1 | Increased percentage vowels/diphthongs distorted | X | X (2) | X (2) | ||||

| Consonants | 2 | Number of nasal emissions | X | X (2) | |||||

| 3 | Increased percentage of weak consonants | X | X (1) | ||||||

| Vowels and consonants | 4 | Increased Diacritic Modification Index class duration | X | X (1) | X (1) | ||||

| Phrasing | 5 | Increased slow/pause time | X | X (1) | X (2) | ||||

| Rate | 6 | Increased slow articulation/pause time | X | X (1) | X (2) | X (1) | |||

| 7 | Decreased average syllable speak rate (with pauses) | X | X (1) | X (2) | X (1) | ||||

| 8 | Decreased average syllable articulation rate (without pauses) | X | X (1) | X (2) | X (1) | ||||

| 9 | Increased fast rate | X | X (2) | ||||||

| 10 | Decreased stability of syllable speaking rate | X | X (1) | X (2) | |||||

| Stress | 11 | Increased excessive/equal/misplaced stress | X | X (2) | X (1) | ||||

| 12 | Increased reduced/equal stress | X | X (2) | ||||||

| Loudness | 13 | Decreased stability of Speech Intensity Index | X | X (2) | X (2) | ||||

| 14 | Increased stability of Speech Intensity Index | X | X (1) | X (2) | X (1) | ||||

| 15 | Increased soft utterances | X | X (2) | X (1) | |||||

| 16 | Decreased Speech Intensity Index (difference dB) | X | X (2) | X (1) | |||||

| Pitch | 17 | Increased low pitch/glottal fry | X | X (2) | X (1) | ||||

| 18 | Increased low pitch | X | X (2) | X (1) | |||||

| 19 | Decreased F0 on vowels & diphthongs | X | X (2) | X (1) | |||||

| 20 | Decreased F0 range on vowels/diphthongs | X | X (1) | X (1) | X (2) | X (1) | |||

| 21 | Decreased stability of F0 on vowels & diphthongs | X | X (1) | ||||||

| Laryngeal quality | 22 | Increased breathiness | X | X (1) | X (2) | ||||

| 23 | Increased rough | X | X (1) | X (1) | |||||

| 24 | Increased strained | X | X (1) | X (1) | |||||

| 25 | Number of utterances with [Tremulous] comment | X | X (1) | ||||||

| 26 | Increased break/shift/tremulous | X | X (2) | X (1) | |||||

| 27 | Increased multiple laryngeal features | X | X (2) | X (2) | |||||

| 28 | Number of diplophonic utterances | X | X (2) | ||||||

| 29 | Increased percentage of jitter on vowels/diphthongs | X | X (1) | ||||||

| 30 | Decreased stability of jitter for vowels | X | X (1) | ||||||

| 31 | Increased percentage of shimmer on vowels | X | X (1) | ||||||

| 32 | Decreased stability of shimmer on vowels | X | X (1) | ||||||

| Resonance quality | 33 | Increased nasal | X | X (1) | X (1) | X (1) | X (2) | ||

| 34 | Decreased F1 for /ɑ/ | X | X (1) | X (1) | X (1) | X (2) | |||

| Totals | |||||||||

| Unweighted | 18 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 19 | 11 | 10 | ||

| Weighted | 18 | 16 | 15 | 23 | 22 | 19 | 15 | ||

A = acoustic; P = perceptual.

The DI includes all 34 items, unweighted. The bolded “X” and number in parenthesis indicate items that are weighted 2 points rather than 1 point within the five DSI. The criteria for a classification of motor speech disorder–dysarthria (MSD-DYS) are a DI score below 80%, two unweighted DSI indices below 70%, and at least one DSI ≤ 10th percentile.

It is important to underscore the high pair-wise intercorrelation coefficients among DSI scores because the same signs are used in as many as three of the five indices (see Table 4). Of the 10 pair-wise correlations between DSI scores from 107 participants meeting DI criteria for dysarthria in preliminary studies, there were three significant positive Pearson r coefficients between DSI subtype scores: ataxic and hyperkinetic (r = .313; p < .001), hypokinetic and flaccid (r = .502; p < .001), and spastic and hyperkinetic (r = .735; p < .001). Thus, what might appear to be mixed dysarthrias may be, at least in part, a function of collinearity among signs in the MCS.

A Sample SDCS Summary Classification

Figure 2 is a sample output from software that cross-classifies a speaker's speech and motor speech classifications. As shown by the placement of the “X” on this summary matrix, this sample from a 17-year-old participant was classified as PSD on the speech classification axis (rows) and MSD-DYS & CAS on the motor speech axis (columns). The output is also used for group data, where the entries in the matrix indicate the number and percentage of participants cross-classified on the speech and motor speech classifications (cf. Shriberg, Strand, & Mabie, 2017). Additional output provides individual or group-percentage classification summaries and standardized percentile findings supporting, for some speakers, one or more of the five dysarthria subtypes. Later analyses will allude to methods and findings reviewed here.

Figure 2.

Sample software classification output for a 17-year-old female speaker.

Development of the PM

This review of the development of a marker to identify speakers with CAS is divided into three parts. Part I, “Methods to Develop a Diagnostic Marker of CAS,” describes procedures used to select, organize, operationalize, standardize, and computerize candidate diagnostic signs of CAS. Part II, “The PM,” describes the PM, outlines procedures to classify speakers as positive (PM+) or negative (PM−) for CAS, and reviews reliability estimates for data reduction procedures (i.e., phonetic transcription, prosody–voice coding, acoustic analyses). Part III, “Supplemental Pause Marker Signs (SPMS),” describes procedures to classify a speaker's status on three supplemental signs of CAS (slow articulatory rate, inappropriate sentential stress, transcoding errors) used to resolve marginal PM scores (i.e., PM scores from 94% to 95.9%) and to support classification of a speaker as PM+ (i.e., CAS+) or PM−. Part III also includes reliability information for each of the three SPMS. The Pause Marker Report includes sample screen displays and audio file exemplars of inappropriate between-words pauses (Tilkens et al., 2017).

Part I. Methods to Develop a Diagnostic Marker of CAS

Selection of Candidate Signs of CAS

Development of a diagnostic marker that can be used to identify CAS began by assembling candidate speech, prosody, and voice signs associated with apraxia of speech from the extensive discussion and tabular presentations in the three editions of Duffy's textbook (Duffy, 1995, 2005, 2013). For programmatic studies of the three subtypes of MSD shown in Figure 1, preliminary candidate signs of MSD-NOS and MSD-DYS were also selected from the broader literatures in SSD of known and unknown origins, including SSD associated with deficits in cognitive, structural, sensory, motor, and affective domains. The primary goal was to identify potential signs of CAS on the basis of deficits in the core transcoding (planning/programming) processes proposed to underlie apraxia of speech (see Figure 1).

Organization

As reviewed in the present text, the canonical organization of signs of MSD in Duffy's curated summaries of the relevant literatures is a matrix in which column heads are types of neurogenic speech disorders and row labels are the speech, prosody, and voice signs (e.g., slow rate; Duffy, 1995, 2005, 2013). A ‘+’ in a column–row cell denotes a sign that discriminates the disorder or disorder type, with a ‘++’ in a cell highlighting signs that are especially discriminative. Classification of a speaker as positive for an MSD requires a criterion number of ‘+’ or ‘++’ signs, sometimes also requiring a specific number of tokens of the sign in specific types of speech samples or tasks. The column-wise and row-wise sequencing of signs in the Duffy tables is designed for visual clarity, with signs organized to aggregate in sets showing the discriminating features among disorders (aphasia, apraxia, dysarthria) and among subtypes of dysarthria.

Shriberg et al. (2010a) described another type of organization matrix for the three classes and eight subtypes of SSD shown in Figure 1. As shown in Table 5, the columns of the matrix organize signs of SSD using a three-parameter system termed Competence, Precision, and Stability Analytics (CPSA; Shriberg et al., 2010a). Competence signs are measures used to index severity of involvement (e.g., percentage of consonants correct obtained from a continuous speech sample, a standardized score on an articulation test). Precision signs index subphonemic spatiotemporal characteristics of speech, prosody, and voice development (e.g., standardized metrics of vowel space or vowel duration). Stability signs index the consistency of behaviors within samples and in repeated trials within and across differing tasks (e.g., coefficient of rate variation).

Table 5.

Organization of signs for the three classes and eight types of speech sound disorders shown in Figure 1 using the Ten Linguistic Domains Analytics and the Competence, Precision, Stability Analytics described in Shriberg et al. (2010a).

| Ten Linguistic Domains Analytics | Competence, Precision, Stability Analytics |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competence |

Precision |

Stability |

|||||

| Perceptual | Acoustic | Perceptual | Acoustic | Perceptual | Acoustic | ||

| Segmental | |||||||

| I. Vowels | 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 15 |

| II. Consonants | 37 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 48 |

| III. Vowels & consonants | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Total | 43 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 71 |

| Suprasegmental | |||||||

| Prosody | |||||||

| IV. Phrasing | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| V. Rate | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| VI. Stress | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Voice | |||||||

| VII. Loudness | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| VIII. Pitch | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| IX. Laryngeal quality | 1 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 15 |

| X. Resonance quality | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 7 | 0 | 24 | 14 | 0 | 6 | 51 |

| Overall total | 50 | 0 | 35 | 23 | 4 | 10 | 122 |

As shown in Table 5, the rows of this matrix organize signs of SSD using a framework described in the text (see Table 2) termed the TLDA (Shriberg et al., 2010a). The TLDA framework organizes signs of SSD by three segmental and seven suprasegmental domains for prosody and voice. As described in the cited reference, the rationale for the TLDA is that these 10 domains comprise an analytically informative framework for descriptive−explanatory accounts of typical and atypical speech development and performance. The 10 domains are neutral relative to theoretical frameworks in child phonology, speech science, and functional neurobiology. The premise is that organization of diagnostic signs of SSD by the three segmental and seven suprasegmental domains shown in Table 2 and Table 5 will yield insights about speech processes in SSD (see Figure 1, Level II) that might be missed if signs of SSD are not aggregated by linguistic domains.

Last, as shown in Table 5, each of the three CPSA columns is subdivided to indicate the method used to quantify each speech, prosody, or voice sign. Perceptually based signs are obtained using narrow phonetic transcription (Shriberg & Kent, 2013), with some signs also requiring prosody–voice coding methods (Shriberg, Kwiatkowski, & Rasmussen, 1990). Acoustically based signs and acoustically aided perceptual signs obtained with an Active X version of TF32 (Milenkovic, 2000) use procedures described in Shriberg et al. (2010a) and the Phonology Project Laboratory Manual (Shriberg et al., 2014). As shown in Table 5, an original pool of 122 candidate signs of SSD (89 perceptual; 33 acoustic) was studied, including the diagnostic sign (the PM) proposed as sufficient for a marker of CAS and three signs that comprise the SPMS (slow articulatory rate, inappropriate sentential stress, and transcoding errors). As described in Part II, the SPMS provides validity support for PM classifications. For the finalized version of the SDCS described previously, which focused on dysarthria, these signs were augmented by the tables in Duffy (2013) that focus on the five subtypes of dysarthria shown in Table 4.

To summarize, using the three-parameter analytic framework shown in Table 5, the PM described in Part II is an acoustic-aided perceptual sign that quantifies one aspect of speech precision in the linguistic domain of phrasing.

Operationalization

To maximize the validity and reliability of candidate diagnostic signs of CAS, the SDCS uses operationalized methods at each phase of data processing. Data are gathered using the Madison Speech Assessment Protocol (MSAP; Shriberg et al., 2010a), which includes 17 tasks that assess speech by imitative and spontaneous methods in simple to complex cognitive, linguistic, and motor contexts. As just described, data reduction includes procedures to quantify speech, prosody, and voice information from responses to MSAP tasks using perceptual and acoustic methods. All data reduction and analyses are completed in the PEPPER (Programs to Examine Phonetic and Phonologic Evaluation Records; Shriberg et al., 2010a) environment. Shriberg et al. (2010b) reported findings from a series of reliability estimates for each of the transcription, prosody–voice coding, and acoustic data reduction methods. As described in Part II, PM scores and scores for two of the three SPMS signs (slow articulatory rate, inappropriate sentential stress) are obtained from eligible utterances from the MSAP's continuous speech sample. Scores for the third SPMS sign (transcoding errors) are obtained from responses to the Syllable Repetition Task (SRT; Shriberg et al., 2009).

Standardization

Although a series of studies has yielded optimum cutoff scores relative to the sensitivity/specificity of some candidate signs of CAS, most signs use reference data that adjust raw scores for individual differences in participants' age and sex, with some MSAP measures substantially mediated by cognitive constraints adjusted for intellectual status rather than by chronological age. For the latter need, the MSAP includes the Kaufmann Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT–2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004).

Reference data are available from three databases. Potter et al. (2012) provides reference data on MSAP tasks for 150 participants, ages 3 to 18 years, with typical speech-language development. Scheer-Cohen et al. (2013) provides reference data on MSAP tasks for 50 participants, ages 20 to 80 years, with typical speech. Mabie et al. (2015) includes reference data for signs obtained from conversational speech samples from 180 speakers, ages 3 to 5 years, with SD of unknown origin.

For each speech, voice, and prosody sign obtained from one or more of the MSAP tasks, a z-score beyond 1 SD from the reference data in the direction indicated by the adjective in the sign's title (e.g., lowered percentage of consonants correct) meets the criterion for “positive” (i.e., atypical) performance. Preliminary studies indicated that, compared with the estimated diagnostic accuracy of more conservative criteria (e.g., 1.25, 1.50, or greater standard deviation units), this relatively liberal criterion yielded the highest sensitivity/specificity values. As discussed later herein, the PM uses a criterion-referenced cutoff score rather than an age-sex–based normative-referenced score to classify a participant's status as PM− (typical) or PM+ (atypical). For the SPMS signs, inappropriate sentential stress and transcoding errors are also based on cutoff criteria, whereas slow articulatory rate is based on age-sex standardized scores.

Computerization

As indicated previously, all methods described in the articles in this series are completed within the PEPPER platform, which will eventually be distributed as freeware that includes tutorials and audio and screen-display exemplars. Until these electronic resources are available, procedural details cited in this report are kept current in the Phonology Project Laboratory Manual, and citations to technical reports can be freely downloaded from the Phonology Project website (http://www.waisman.wisc.edu/phonology/).

Part II. The PM

Description and Procedures

The PM defines a between-words pause as any between-words period of at least 150 ms in which there is no speech. An inappropriate pause is “a between-words pause that occurs either at an inappropriate linguistic place in continuous speech and/or has one or more inappropriate articulatory, prosodic, or vocalic features within the pause or in a sound segment preceding or following the pause” (Tilkens et al., 2017, p. 5).

Table 6 is a typology of eight inappropriate between-word pauses that were identified in preliminary, unpublished studies of citation forms and continuous speech samples from speakers across the life span with typical and atypical speech. As described in the next paragraph, the percentage of occurrence of the first four types of inappropriate pauses at present comprises what is termed the PM. Participants with atypical speech included speakers with idiopathic SSD or SSD in neurologic, neurogenetic, and complex neurodevelopmental contexts. Judgments about the appropriateness of pauses and classification of each pause into one or more of each of the eight types of inappropriate pauses in Table 6 are made by an acoustics analyst using software (PEPPER) that includes a phonetic transcript of a participant's continuous speech; wave form and spectrographic displays; and dialogues to compute, code, and store data.

Table 6.

Auditory–perceptual and acoustic descriptions for eight subtypes of inappropriate between-words pauses.

| Type | Subtype | Locus of inappropriate behavior |

Descriptions of eight types of inappropriate pauses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within pause | Within adjacent sound(s) | |||

| Type I | Abrupt | X | A pause immediately preceded or followed by a phoneme that includes a sudden strong onset of energy or sudden offset of energy. Steep-amplitude rise/fall time is the best current visual and acoustic correlate of the percept of an abrupt phoneme. | |

| Alone | – | – | A pause that occurs at a linguistically incorrect position in an utterance, is not one of the other seven subtypes of inappropriate pauses, and does not have any identifiable auditory or acoustic feature. | |

| Change | X | A pause immediately preceded or followed by a phoneme or word that includes a significant change in amplitude, frequency, or rate. | ||

| Grope | X | A pause that includes visible acoustic energy in the spectrogram consistent with a lip or tongue gesture or inappropriate voicing. The gestures may include formant traces of sounds or traces of incompletely realized stop bursts. | ||

| Type II | Long | X | A pause that has a lengthened duration that is unusual for the linguistic context (usually > 750 ms). | |

| Breath | X | A pause that includes audible inhalation not associated with excessive length of the utterance or emotional excitement. | ||

| Repetitions/revisions | X | A pause immediately preceded or followed by a dysfluent word or syllable repetition or revision. | ||

| Additions | X | A pause immediately preceded or followed by an added speech sound. | ||

Note. See text for rationale for dividing the subtypes into two classes termed Type I and Type II. The four subtypes of inappropriate pauses within Type I and within Type II are each listed in decreasing frequency of occurrence in the present sample of participants with childhood apraxia of speech.

As shown in the Table 6 typology, the eight inappropriate between-words pause types are divided into two types: pause type I and pause type II. Pause type I includes four pause types that occurred frequently and predominantly in speakers suspected to test positive for CAS in idiopathic, neurogenetic, and complex neurodevelopmental contexts, as well as in a construct validity comparison group that included two types of AAS—apraxia of speech and primary progressive apraxia of speech. Pause type II includes four inappropriate pause types that occurred less frequently than type I pauses, both in young speakers suspected to test positive for CAS and in the two types of AAS. Only utterances that met eligibility criteria for coding using the Prosody–Voice Screening Profile (PVSP; Shriberg et al., 1990; i.e., utterances not confounded by behaviors such as laughing, chewing food, etc.) were coded for occurrences of the eight types of inappropriate between-words pauses. As described in the following section, the four type I pauses are used to compute the PM. Type II pauses are retained for their potential to inform explanatory accounts of speech processing in apraxia of speech, as used in the third article in this research. Tabular data on the frequency of occurrence of each inappropriate pause type in three participant groups are available in Tilkens et al. (2017; see Table 5).

Using the definitions in Table 6, the acoustic analyst completes the following four steps to code the occurrence of each of the eight types of inappropriate pauses.

Identify all pauses longer than 150 ms in the 24 (sometimes fewer) utterances eligible for coding (i.e., not meeting one or more of the 31 PVSP exclusion codes).

Set the duration of the pause by positioning the cursors directly after the final glottal pulse, if voiced, or measurable speech energy of the preceding segment and just before the next glottal pulse or measurable speech energy.

Set the pause location within the utterance displayed on the screen by positioning the right cursor anywhere within the boundary of the pause.

Classify the pause (by checking the on-screen box) as either appropriate or inappropriate for the linguistic context and indicate whether it meets criteria for one or more of the eight types of inappropriate between-words pauses listed in Table 6. Audio–visual exemplars of these procedures are included in the Pause Marker Technical Report (Tilkens et al., 2017).

Calculation of a PM Score

Speech Sample

The PM score is the percentage of inappropriate between-words type I pauses that occur in the 24 utterances of a continuous speech sample that meet eligibility criteria for PVSP coding. As described in the PVSP manual, referred to previously, eligible utterances are those that do not include one or more of 31 behaviors (exclusion codes) that would interfere with PVSP coding (e.g., an utterance spoken while laughing, eating, or in a play register). For some speech samples, 24 eligible utterances may not be available; for these samples the PM is based on fewer than 24 utterances, resulting in a possible reduction in the internal and external validity of the data. Because PM calculations are word centered, the average number of words per utterance is more important than the total number of utterances. As determined from pilot study, speech samples with fewer than 40 between-words opportunities for pauses are not eligible for a valid PM score. As described in the text, the PM outcome from such a sample is classified as indeterminate. For some research or clinical applications, obtaining an additional speech sample could be a means to aggregate a sufficient number of pause opportunities (at least 40) to calculate a usable PM score.

Calculation

The denominator for the PM is the total opportunities for pauses, defined as the total number of words in the PM analysis minus the total number of PVSP coded utterances. The numerator for the PM calculation is the total number of occurrences of the four types of inappropriate type I pauses in Table 6. The product is multiplied by 100 to yield a percentage.

PM Cutoff Score

Series of analyses were completed with subsets of participants with typical and atypical speech to determine a PM score cutoff point that maximally discriminated children with CAS as classified by the second author (using a procedure described in PM III; Shriberg et al., 2017b) from children with SD as classified by the SDCS (see Figure 1). These studies indicated that a percentage of inappropriate between-words pauses more than 5% is optimally sensitive to and specific for participants with CAS as classified using the MCS. To make the direction of this criterion consistent with other competence percentage scores, the percentage of occurrence of inappropriate pauses is subtracted from 100. Thus, speakers with scores of 95% and above are classified as having typical or appropriate between-words pausing (PM−), and speakers with PM scores below 95% are classified as positive (PM+) for CAS. PM scores from 94% to 95.9% (i.e., within one percentage point of the 95% cutoff) are termed marginal PM scores. This convention was developed in lieu of an estimate of the standard error of measurement of PM scores, which would require a larger database of samples than is currently available. Procedures to resolve marginal PM scores are described in Part III.

Reliability Estimates for the PM

Four estimates of the reliability of identifying inappropriate pauses in continuous speech were obtained. Each estimate used the acoustic-aided coding procedures just described to identify the inappropriate pauses shown in Table 6. Because the two analysts who completed the initial PM coding and the reliability recoding were very familiar with the database samples, some intrajudge reliability estimates used consensus rather than individual analyst reliability procedures.

The first of two interjudge agreement estimates included speech samples from 30 participants whose transcripts contained inappropriate pauses, 17 randomly selected from the consensus CAS+ participants described in PM II (Shriberg et al., 2017a), and 13 with SD whose transcripts contained inappropriate pauses. One of the acoustic analysts had originally identified a total of 195 inappropriate pauses in these samples. A second analyst identified 159 of the 195 inappropriate pauses, yielding an interjudge agreement estimate of 81% for the identification of inappropriate pauses in continuous speech.

A second estimate of the interjudge agreement in identifying inappropriate pauses was obtained using speech samples from 40 participants. The samples were randomly drawn from each of three groups described in PM II (Shriberg et al., 2017a): the consensus CAS+ participants, the participants with SD, and participants of comparable ages from the Potter et al. (2012) reference database of speakers with typical speech development. Of the total of 550 pauses identified in these three sources, 198 were coded as inappropriate: 176 in the larger group of MSD participants, 19 in the SD group, and 3 in the reference group. Each of the samples originally coded for inappropriate pauses by one analyst was re-coded by another analyst. The overall interjudge agreement was 81%, with individual agreement estimates of 82% for the MSD participants, 79% for the SD participants, and 66% for the participants with typical speech development.

Estimates of the intrajudge reliability of identifying inappropriate pauses were completed using speech samples from 34 of the 40 participants used in the second interjudge reliability estimate. Each of 422 obtained pauses were coded as either appropriate or inappropriate by two analysts using a consensus procedure. Approximately 2 to 3 months later, each analyst individually re-coded the 422 pauses, which included 136 inappropriate pauses: One hundred seventeen were from the MSD group, 12 were from the SD group, and 7 were from the reference group. For one analyst, overall intrajudge agreement was 82%, with individual estimates of 86% from the MSD samples, 58% from the SD samples, and 43% from the reference group samples. For the second analyst, overall agreement was 77%, with individual estimates of 77% from the MSD samples, 75% from the SD samples, and 86% from the reference group samples.

A final intrajudge reliability estimate included only the four type I inappropriate between-words pause types termed abrupt, alone, change, and grope (see Table 6). As discussed previously, in preliminary studies, these four types of inappropriate pauses were most frequently associated with the CAS+ classifications completed by the second author using the MCS. As shown in the Pause Marker Technical Report (Tilkens et al., 2017), the other four inappropriate pauses in Table 6 (later termed Type II) occurred significantly less often in participants suspected to test positive for CAS and participants meeting criteria for AAS. The two analysts selected 13 participants with CAS and SD who as a group had high rates of the four type I inappropriate pauses. The analysts then used a consensus procedure to identify, from the 13 continuous speech samples, a total of 245 inappropriate pauses. Of the 202 type I inappropriate pauses, 141 were abrupt pauses, 29 were alone pauses, 21 were change pauses, and 11 were grope pauses. Approximately 2 to 3 months later, using the same consensus procedure, analysts re-coded 170 of the 202 inappropriate pauses (84%) as the same inappropriate pause subtype assigned in the prior consensus coding. At the level of individual inappropriate pause types, 86% of the abrupt pauses, 76% of the alone pauses, 86% of the change pauses, and 82% of the grope pauses were re-coded as the same inappropriate pause type assigned in the first consensus coding, yielding a four-type average consensus reliability of 82.5%.

The absolute magnitudes of these intrajudge and interjudge reliability estimates are not high, but they are consistent with point-by-point agreement percentages reported for other perceptually based independent and dependent variables in speech development and SSD research (e.g., Shriberg & Lof, 1991; Shriberg et al., 2010b).

Tilkens et al. (2017) included a summary of findings from a study series to identify acoustic correlates of abrupt inappropriate pauses. Collaborative research using alternative instrumental methods is needed to automate the PM for increased reliability and efficiency. PM III (Shriberg et al., 2017b) discusses associated issues toward a long-term goal of a neural marker of apraxia of speech.

Part III. Supplemental Pause Marker Signs

Rationale

A participant's status on the SPMS is used for two purposes. The primary purpose is to resolve marginal PM scores (i.e., PM scores from 94% to 95.9%). For speakers with PM scores in this marginal range relative to the 95% cutoff point, the speaker's SPMS status determines whether the speaker is classified as PM+ or PM−. Research toward a diagnostic marker of CAS has supported slow articulatory rate, inappropriate sentential stress, and transcoding errors as statistically associated with suspected CAS in a number of published and unpublished studies. Speakers with marginal PM scores who test positive or negative on at least two of the three SPMS signs meet criteria, respectively, for either marginal CAS+ or marginal CAS−. The final PM classification for participants with negative SPMS outcomes is annotated as SPMS−, and the final marginally negative PM classification is annotated as PM−. Speakers with marginal PM scores and indeterminate SPMS outcomes (i.e., the available data on the three signs are insufficient to meet criteria for SPMS+ or SPMS−) are classified as indeterminate (annotated as IND). As noted in the text, this latter conservative convention acknowledges the need for supportive information when using one test instrument to identify a disorder. Obtaining an additional continuous speech sample for a research or clinical need could yield a PM score that is classifiable (i.e., the additional PM score is not marginal, or if marginal, it can be resolved with sufficient SPMS information).

The second purpose of the SPMS is to provide supplemental validity support to all clinical and research findings using the PM score to classify a speaker as CAS+ or CAS−. For example, if the PM score for a speaker is inconsistent with other clinical or research information about the speaker, SPMS findings can be used to aid in interpretation of findings (e.g., PM findings could possibly be invalid because of behavioral or methodological constraints during assessment). The following sections provide brief rationales and procedures for each of the three SPMS signs.

Slow Articulatory Rate

Rationale

Slow articulatory rate has strong face validity as a sign of planning and/or programming deficits. Because rate of speech is not learned in the way segmental and certain suprasegmental features of a language are mastered during development, the CPSA framework classifies slow articulatory rate as a precision sign rather than a competence sign. Slow articulatory rate is sensitive to CAS, and it is demonstrably specific relative to age-sex–based comparisons to speakers with typical speech (Potter et al., 2012) and to speakers with speech delay of unknown origin (McSweeny et al., 2012). A primary specificity constraint, however, is that slow articulatory rate is present in speakers with several types of MSD. Thus, although a primary sign of the classification of MSD compared with SD (see Figure 1), slow articulatory rate is not specific among the subtypes of MSD in the SDCS framework.

Procedures and Reliability

Articulation rate is defined as the number of syllables per second minus pause time. In operation, articulation rate is identified as slow when a speaker's z-score is lower than 1 SD from the mean articulation rate of typical speakers of the same chronological age (or adjusted for mental age, as in the present article, when available) and sex (Potter et al., 2012; Scheer-Cohen et al., 2013). As discussed elsewhere in this series, the selection of the z-score criteria for each analysis (i.e., 1 SD, 1.25 SD, 1.5 SD) was determined arbitrarily from a combination of considerations, including the estimated precision of the measurement of the variable, precedent data in the literature, and the consequences of increasing the probability of false positive versus false negative classifications. The criteria of 1 SD unit was selected as the default for rate and all other SDCS standardization procedures, with more stringent criteria used for some analyses to decrease the probability of false positives.