Abstract

Gastrointestinal nematode infection is known to alter host T cell activation and has been used to study immune and inflammatory reactions in which nitric oxide (NO) is a versatile player. We previously demonstrated that Trichinella spiralis infection inhibits host inducible NO synthase (NOS-2) expression. We now demonstrate that (i) an IL-4 receptor α-subunit (IL-4Rα)/Stat6-dependent but T cell-independent pathway is the key for the nematode-induced host NOS-2 inhibition; (ii) endogenous IL-4 and IL-13, the only known IL-4Rα ligands, are not required for activating the pathway; and (iii) treatment of RAW264.7 cells with parasite-cultured medium inhibits NOS-2 expression but not cyclooxygenase 2 expression. We propose that a yet-unidentified substance is released by the nematode during the host–parasite interaction.

Keywords: inflammation, nematode, immunoregulation, nitric oxide, endotoxin

Gastrointestinal nematode infection has served as a well established model to study parasite-induced host T cell activation and cytokine regulation (1, 2). Interaction within the cytokine network plays a key role in the control of immunity and inflammation that mediates host protective responses (3, 4). Recently, nitric oxide (NO) has been recognized as one of the most versatile players in the immune system based on several findings. (i) Producing or responding to NO is a major feature of macrophages and many other immunesystem cells. (ii) All isoforms of NO synthase (NOS) are expressed in the immune system, and induction of inducible NOS (NOS-2) has been implicated in a variety of immunologic inf lammatory conditions. (iii) NOS-2 expression is up-regulated by T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines and inhibited by Th2 cytokines. In addition, the effects of NO are not restricted to any single cytokine receptor. Thus, NO plays a very diverse role in the immune system. (iv) Activation of NOS-2 results in the production of a high concentration of NO. Highly diffusible ·NO is rapidly oxidized to reactive nitrogen species that are detrimental in several immunopathologic processes [see reviews (5–7) for further information].

We have previously demonstrated that Trichinella spiralis infection induces down-regulation of NOS-2 expression (8), which has the following characteristics. (i) Local jejunal infection by T. spiralis systemically inhibits NOS-2 gene transcription, protein expression, and enzyme activity in the ileum, jejunum, colon, kidney, lung, and uterus. (ii) The effect of inhibition is potent and can override endotoxin-induced NOS-2 expression. (iii) The inhibition does not extend to the expression of other isoforms of NOS; to paxillin, a housekeeper protein; or to cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), another protein induced by proinflammatory cytokines. (iv) The inhibition is not associated with a chemically induced intestinal inflammatory response. (v) The inhibition is unlikely related to the formation of specific anti-parasite antibodies. (vi) The inhibition may involve substances other than stress-induced corticosteroids.

The objective of the current study was to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the NOS-2 inhibition by parasitic infection, and the results of our studies (i) demonstrate an IL-4 receptor α-subunit (IL-4Rα)/Stat6-dependent but T cell-independent pathway that down-regulates NOS-2 expression during parasitic infection; (ii) show that in mice lacking endogenous IL-4 and IL-13, the only known agonists for IL-4Rα, T. spiralis infection still activates the host IL-4Rα/Stat6 signaling pathway (thus, we propose that a novel substance or alternative IL-4Rα ligand is released by the helminth during the host–parasite interaction); and (iii) show that treatment of RAW264.7 cells with T. spiralis-cultured medium can cause significant inhibition of NOS-2 protein and mRNA expression, while COX-2 expression remains unaffected. Thus, the mechanism and effects can occur both in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, our data challenge the classic explanation for a CD4+ T cell-dependent immune mechanism that protects against helminth infection and shed new light on the complex parasite–host interaction and the immune responses to parasite infection. We provide a paradigm for the mode of action of IL-4Rα/Stat6 signaling in regulating NOS-2 expression that is important for understanding cytokine-mediated inflammatory reactions. Further elucidation of this pathway could lead to the development of new therapies for inflammatory conditions characterized by overproduction of NO, and also could provide more insight into the hygiene hypothesis that has been very influential in directing strategies to prevent allergic diseases.

Methods

Animals, Treatment, and T. spiralis Infection. Male CF-1 mice and athymic nude mice [body weight (BW) 25–30 g] and Sprague–Dawley rats (BW 250–300 g) were obtained from Harlan. Transgenic mice with disrupted genes for Stat6 (Stat6–/–; BALB/c-Stat6tm1Gru); IL-4 receptor α-subunit (IL-4Rα–/–; BALB/c-Il4rαtm1Sz); IL-4 (IL-4–/–; BALB/c-Il4tm2Nnt); γ,δ, T cell receptor (γδ TCR–/–; C57BL/6J-Tcrdtm1Mom); and α,β,γ,δ, T cell receptor (αβγδ TCR–/–; C57BL/6J-Tcrbtm1Mom Tcrdtm1Mom), as well as the respective WT controls, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. IL-4 and IL-13 double gene-knockout (IL-4–/–/IL-13–/–) mice were kindly provided by A. N. McKenzie and F. G. Lakkis (Medical Research Council, London). The IL-4/IL-13 KO mice were generated as described in ref. 9 and bred onto a BALB/c background for at least eight generations (10). Control (WT) BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The ages of all experimental mice were 5–6 weeks. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Texas Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee. T. spiralis was maintained by passage in CF-1 mice. Naive mice were inoculated orally with 600 T. spiralis larvae obtained by enzymatic digestion of skeletal muscle from infected mice (8). For cytokine measurements, animals were killed 1–10 days after oral inoculation (8). For the experiments involving tyrosine kinase inhibition, T. spiralis-infected or uninfected mice were divided into herbimycin A-treated and vehicle (DMSO)-treated groups. Herbimycin A (Calbiochem) was administered (15 μg/g of BW) i.p. According to the results from real-time continuous assay of cytokines in the intestinal (afferent) and efferent thoracic duct lymph, IL-4 activity reaches a peak at day 2 postinfection (PI) (11) with T. spiralis and then declines to normal levels by day 4. However, by about day 7 PI, IL-4 levels rise again to reach a second peak (11). Based on this time course, we injected herbimycin A on days 2 and 7 PI, and then NOS-2 expression in the ileum was analyzed by Western blot. For the experiments involving IL-4 receptor antibody, T. spiralis-infected or uninfected mice were divided into IL-4 receptor antibody- and vehicle-treated groups. Monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL-4 receptor antibody (CDw124, R & D Systems) was administered (6.5 μg/g of BW) i.p. on the day of T. spiralis inoculation as well as days 2 and 7 PI, according to the profile of IL-4 release after infection (11). At death, the proximal jejunum and distal ileum were quickly isolated and for some experiments; the mucosa was also isolated. All tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –135°C until further processing.

Tissue Processing and Sample Preparation. Frozen tissues were pulverized with a pestle and mortar that contained liquid nitrogen. For protein extraction, the tissues were homogenized at 4°C in 20 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (final concentration: 10 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor/10 μg/ml benzamadine/5 mTIU/ml aprotinin/10 μg/ml leupeptin/10 μg/ml pepstatin A/5 μg/ml antipain/0.2 mM phenylmethane sulfonate fluoride/0.1 mM ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid). Each sample was homogenized by using a polytron tissue grinder at 4°C then sonicated on ice by using a cell disrupter with five pulses at a duty cycle of 40% and an output of 3. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and supernatant fractions were used for SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblotting.

In Vitro Adult Worm and Newborn Larvae (NBL) Culture. Ten Sprague–Dawley rats were infected with 10,000 infective muscle T. spiralis larvae isolated from infected CF-1 male mice. On day 4 PI, food was removed from those infected rats, and on the following day (day 5 PI), the rats were killed. The entire small intestine was removed from each animal and incubated in 0.9% saline solution at 37°C with gentle shaking. Adult T. spiralis worms were collected over a period of 4 h (recover rate ≈70%; thus, 70,000 worms were collected), then washed with saline containing 2% antibiotics (“antibiotic-antimycotic mixture” from GIBCO) four times at an interval of 0.5 h. The worms were then transferred into three cell culture flasks containing RPMI medium 1640 with 2% antibiotics (30 ml per flask) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After incubation, NBL could be observed under the microscope (Fig. 6C). The medium containing worms and NBL was sedimented for 10 min at 300 × g at room temperature, and the supernatant was collected and used for cell assay for NOS-2 expression.

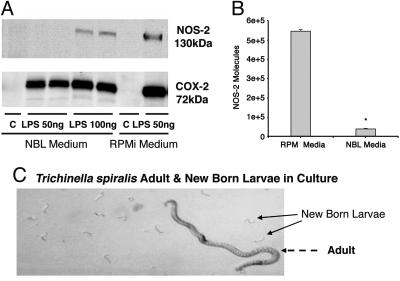

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of NOS-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells by a T. spiralis-secreted substance(s). (A) Immunoblotting for NOS-2 and Cox-2 in RAW264.7 cells cultured with NBL medium and control medium. LPS was used for induction of NOS-2 and Cox-2. Treatment with NBL medium inhibited LPS (50 ng/ml)-stimulated NOS-2 expression by 100%. Increasing the concentration of LPS to 100 ng/ml only partially overcame the inhibition by worm-cultured medium [expression in response to 100 ng/ml LPS was still <50% of the expression in response to LPS (50 ng/ml) in control medium]. In contrast, the expression of COX-2 was not significantly altered. (B) Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of NOS-2 mRNA in RAW264.7 cells cultured with NBL medium and control medium. Changes in RAW264.7 cell NOS-2 mRNA were quantified after normalizing to NOS-2 standard. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3–6). *, P < 0.01 compared with control. (C) In vitro culture of T. spiralis adult worm and NBL.

RAW264.7 Cell Assay for NOS-2 Expression. Murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 was maintained at 37°C and 5%CO2 in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% low endotoxin FBS (HyClone). For treatment, the cells were exposed to adult- and NBL-cultured medium (10% vol/vol) or control RPMI medium 1640 and 2% antibiotics for 36 h. Then, LPS (50 and 100 ng/ml) was used for induction of NOS-2 and COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells. Four hours after LPS stimulation, the cells were lysed and proteins were extracted according to the procedure described above.

Immunological Reagents. Polyclonal rabbit anti NOS-2 antibody was developed by our group (12). Monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL-4 receptor antibody (CDw124) was purchased from R & D Systems. Polyclonal rabbit anti COX-2 antibody was purchased from Upstate (Charlottesville, VA).

Western Blot Analysis. Equal amounts of proteins (50 or 100 μg per well) were loaded onto the gel for each experimental sample. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and the membranes were treated with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T (20 mM Tris·HCl/130 mM NaCl, pH7.6/0.1% Tween 20), then incubated at 4°C overnight with the anti-NOS-2 or COX-2 polyclonal antibodies. The membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. Chemiluminescence was used to identify NOS-2 or COX-2 protein according to the ECL Western blotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences).

Cytokine Measurements. Whole blood and the mucosa from the proximal jejunum and distal ileum were obtained from experimental animals. Sera were isolated after allowing the blood to coagulate at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min. The mucosa tissue was processed as described in the methods for sample preparation. The levels of cytokines in both sera and mucosa tissues were determined by using mouse IL-4 and IL-13 sandwich ELISA from R & D Systems. Tissue levels of IL-4 are reported as ng of cytokine per mg of protein, and serum IL-13 is reported as pg/ml.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription. RAW264.7 cell RNA was extracted by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of RNA was checked by absorbance at 260 and 280 nm and gel electrophoresis. Total RNA (0.3 μg) was reverse-transcribed by using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR. NOS-2 mRNA Quantitative PCR was performed by using an ABI/PerkinElmer 7700 Sequence Detector. All PCRs were performed in triplicate in a volume of 25 μl, using 96-well optical-grade PCR plates and optical sealing film. The QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) was used for real-time quantification of double-stranded DNA targets. A pair of conventional PCR primers for mouse NOS-2 (sense, 5′-CAG CTG GGC TGT ACA AAC CTT-3′; position of cDNA 2176–2197; antisense, 5′-ATG TGA TGT TTG CTT CGG ACA-3′; position of cDNA 2220–2241) was used for the amplification reaction. The following thermal cycler program was used: initial activation of the HotStar Taq polymerase at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of the DNA denaturation step at 95°C for 15 s, primer annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. Melt-curve analysis was performed by slowly heating the PCR products from 60°C to 95°C with simultaneous measurement of the SYBR Green I signal intensity. We calculated the relative expression of NOS-2 transcripts by generating standard curves from serial 10-fold dilutions of an oligo DNA bearing the NOS-2 assay amplicon. For each reaction, the Ct (number of PCR cycles required for the fluorescent signal to reach threshold) is directly proportional to the amount of input template. Therefore, with the use of a standards dilution series of known concentration (5-log), the number of molecules for the samples was determined by interpolation from the standard curves. All experiments were conducted multiple times (at least three), using the appropriate positive, negative, and no-template controls. Fluorescence emission spectra were monitored in real time for amplification kinetics, and melting-curve analyses were performed to assess the specificity of the amplified products. For further conformation, PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels.

Results

Suppression of NOS-2 by T. spiralis Infection Depends on an IL-4Rα/Stat6-Mediated Pathway. Previous studies on the mechanisms of protective immunity to intestinal nematode have demonstrated that Th2 cells and IL-4 play a central role in host defense (1, 13, 14). Therefore, we studied the effect of blocking the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) on T. spiralis-initiated NOS-2 down-regulation by injecting a monoclonal anti-mouse IL-4R antibody that recognizes both soluble and membrane-bound IL-4 receptor. Such treatment profoundly interfered with the ability of T. spiralis to down-regulate NOS-2 expression (data not shown).

The IL-4 receptor complex is composed of α chain and γ common chain (γc) receptor subunits. The 140-kDa α chain specifically binds IL-4 with high affinity, whereas the γc chain serves as a component shared with receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15 (15). To further study the role of the IL-4 receptor, we used IL-4Rα-deficient mice that lack the α chain of both soluble and membrane forms of the receptor (16). As in control mice, NOS-2 was detected in the ileum of IL-4Rα gene knockout mice under noninfected conditions. After infection with T. spiralis for 9 days, NOS-2 expression in the ileum of WT control mice was almost abolished. However, the infection did not inhibit NOS-2 expression in the ileum of IL-4Rα KO mice (Fig. 1A).

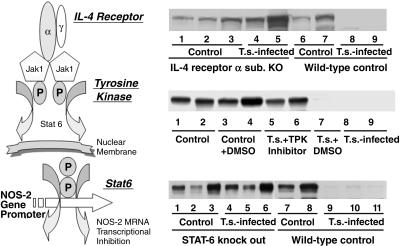

Fig. 1.

Suppression of NOS-2 by T. spiralis (T.s.) infection depends on an IL-4Rα/Stat6-mediated signaling pathway (scheme in Left). Immunoblotting for NOS-2 in ileum from IL-4Rα–/– and WT control mice (A); tyrosine kinase inhibitor herbimycin A treated and control mice (B); and Stat6–/– and WT control mice (C). Each indicated lane number represents an individual animal used in the experiment. Ileal NOS-2 expression was abolished after 9 days of T. spiralis infection in control groups, whereas no change was noticed in IL-4Rα–/– (A, lanes 4 and 5), herbimycin A-treated (B, lanes 5 and 6), and Stat6–/– (C, lanes 4–6) mice.

Stat6 is activated by IL-4R and is essential for induction of IL-4-dependent gene expression (17). Furthermore, IL-4-induced Stat6 activation has been shown to suppress the transcriptional activation of some NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory mediators (18) that, in turn, may result in up-regulation of NOS-2 (19). Recently, an important role for Stat6 has been reported in protective immunity in mice infected with T. spiralis (20). Therefore, we evaluated intestinal NOS-2 expression in T. spiralis-infected Stat6-deficient (Stat6–/–) and WT mice. NOS-2 was constitutively expressed in the ileum of both Stat6 KO mice and its WT control (Fig. 1C). After infection with T. spiralis for 8 days, NOS-2 expression in the ileum of control mice was almost abolished. However, this T. spiralis-initiated NOS-2 down-regulation was not observed in the ileum of STAT6 gene knockout mice (Fig. 1C). Thus, Stat6 plays an important role in NOS-2 down-regulation during T. spiralis infection.

Stat factors are latent cytoplasmic proteins that are activated by tyrosine phosphorylation to allow them to homodimerize and rapidly translocate into the nucleus (21). To confirm the role of tyrosine phosphorylation in T. spiralis-initiated NOS-2 down-regulation, we performed experiments with the widely used tyrosine kinase inhibitor herbimycin A. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, tyrosine kinase inhibition by herbimycin A clearly blocked T. spiralis-infection-initiated NOS-2 down-regulation.

A T Cell-Independent IL-4Rα/Stat6-Stimulating Pathway Is Activated During T. spiralis-Induced Inhibition of NOS-2. IL-4 plays a central role in the regulation of immune responses by promoting the differentiation of Th cells toward the Th2 subset. On the other hand, IL-4 gene expression is highly tissue-specific, and IL-4 is mainly produced by T cells and highly produced by differentiated Th2 cells (1, 22). Data show that infection with T. spiralis induces rapid changes in the population of T cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) that represents a common basis underlying the onset of the gut mucosal immunological reaction (23). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume a prominent role of T cells and their products in T. spiralis-induced down-regulation of NOS-2. To further study the role of T cells, we performed a series of experiments with T cell-deficient mice.

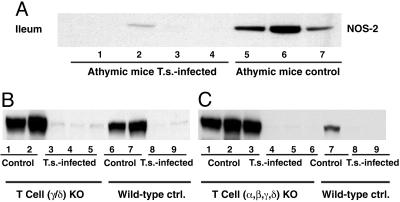

Athymic nude mice have rudimentary thymuses in which T cell maturation cannot occur normally. As a result, there are few or no mature T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs and a failure of all cell-mediated immune reactions. As in normal mice, NOS-2 was constitutively expressed in the ileum of athymic mice (Fig. 2A). After infection with T. spiralis for 7 days, NOS-2 expression in the ileum of athymic mice was almost abolished. Thus, thymic-derived T cells are not involved in T. spiralis-initiated NOS-2 down-regulation (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

A T cell-independent IL-4Rα/Stat6 pathway is activated during T. spiralis-induced inhibition of NOS-2. Immunoblotting for NOS-2 in ileum from athymic mice (A); γδ TCR–/– and WT control mice (B); and αβγδ TCR–/– and WT control mice (C). Each indicated lane number represents an individual animal used in the experiment. Ileal NOS-2 expression was abolished after 9 days of T. spiralis infection in both control and T cell-deficient mice.

Two types of T cells exist; one expresses the T cell receptor (TCR) α/β heterodimer and the other the TCR γ/δ heterodimer. Whereas α/β TCR+ cell development is tightly regulated within the thymus, γ/δ TCR+ cells can develop extrathymically. In the human colon and small intestine, 5–40% of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) are γ/δ TCR+ cells, and in mice, an even greater proportion of IEL are γ/δ TCR+ cells (24, 25). A study (26) that showed a significant increase of γ/δ TCR+ cells in IEL after T. spiralis infection suggests a role for γ/δ TCR+ cells in mucosal responses to enteric parasitic infections. Therefore, we performed experiments with γ/δ TCR+-gene-deficient mice. Similar to what was seen in control mice, NOS-2 was also observed in the ileum of γ/δ TCR–/– mice (Fig. 2B). After infection with T. spiralis for 7 days, NOS-2 expression in the ileum of γ/δ TCR–/– mice was markedly attenuated (Fig. 2B). Thus, a deficiency of γ/δ TCR–/– does not affect the T. spiralis-induced NOS-2 down-regulation pathway. To further confirm that a T cell-independent IL-4/Stat6 pathway is activated in T. spiralis-induced inhibition of NOS-2, we performed experiments with transgenic mice with a disrupted gene of αβγδ TCR (α/β/γ/δ TCR–/–). NOS-2 expression in the ileum of α/β/γ/δ TCR–/– mice was almost abolished after infection with T. spiralis (Fig. 2C). Thus, T cells are not involved in the IL-4Rα/Stat6 pathway that mediates T. spiralis-induced NOS-2 down-regulation.

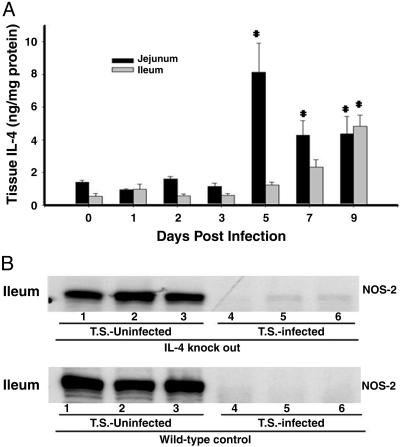

Is Another Factor or Pathway Involved in the Stimulation of the IL-4Rα/Stat6 Pathway During T. spiralis Infection and Host Reaction? The IL-4 receptor exists as both a type 1 (α+γc) and a type 2 (α+IL-13Rα1) IL-4R. The type 1 receptor binds exclusively IL-4, whereas the type 2 receptor can bind either IL-4 or IL-13 (27). The finding that the T. spiralis-stimulated and IL-4Rα/Stat6-mediated NOS-2 inhibitory pathway is T cell-independent led to the suggestion that a unique mechanism may be engaged in this NOS-2 inhibitory process. To verify the relationship between IL-4 and NOS-2 regulation, we first measured serum levels of IL-4 and found they were undetectable during T. spiralis infection (data not shown). We, therefore, measured local tissue levels of IL-4 within the jejunal and ileal mucosa from T. spiralis-infected mice. We found a market increase of IL-4 after 5 days of infection (Fig. 3A) in jejunal tissue and after 9 days of infection (Fig. 3A) in ileum. To further elucidate the role of endogenous IL-4 in the activation of the IL-4Rα/Stat6 pathway, we determined whether NOS-2 down-regulation during T. spiralis infection occurred in IL-4 gene knockout animals. Again, NOS-2 was detected in the ileum of IL-4 KO mice under noninfected conditions (Fig. 3B). After infection with T. spiralis for 9 days, NOS-2 expression in the ileum of both IL-4–/– mice and its WT control was markedly inhibited (Fig. 3B). Thus, a deficiency of endogenous IL-4 production does not affect the T. spiralis-activated IL-4Rα/Stat6 pathway.

Fig. 3.

Endogenous IL-4 deficiency failed to affect T. spiralis-induced NOS-2 inhibition. (A) Tissue levels of IL-4 within the jejunal and ileal mucosa from T. spiralis-infected CF-1 mice were measured (uninfected animal was labeled as day 0). A marked increase of IL-4 after 5 days of infection in jejunum and after 9 days of infection in ileum was observed (*, P < 0.01). Data are the mean of four animals in each group. (B) Immunoblotting for NOS-2 in ileum from IL-4–/– and WT control mice. Each indicated lane number represents an individual animal used in the experiment. Ileal NOS-2 expression was abolished after 9 days of T. spiralis infection in both control and IL-4–/– mice.

The results above imply that IL-13, the only other cytokine that uses the IL-4Rα/Stat6 pathway, may be important in T. spiralis-induced NOS-2 down-regulation. To clarify the role of IL-13, we measured serum levels of IL-13 collected from IL-4–/– mice and its WT control. Despite a lack of endogenous IL-4 production, T. spiralis infection resulted in a marked increase (85-fold) in IL-13 (Fig. 4A). In WT control mice, T. spiralis infection induced elevations of IL-13 to even higher levels (431 pg/ml) than in IL-4–/– mice (Fig. 4A). These data are in themselves interesting because it is believed that IL-4 plays a central role in the regulation of immune responses by promoting the differentiation of Th cells toward the Th2 subset that is a primary source for IL-13 secretion. To further understand IL-13 generation after T. spiralis infection, we performed serum IL-13 measurements with the samples from mice with the disrupted gene of αβγδ TCR. T. spiralis-infection-stimulated IL-13 levels were markedly decreased in α/β/γ/δ TCR–/– mice, whereas they remained high in WT control mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The impact of endogenous IL-4 and T cells on serum concentration of IL-13. (A) Despite a lack of endogenous IL-4 production, a 9-day T. spiralis infection resulted in a marked increase in serum IL-13 (85-fold). The elevations of IL-13 were even higher (431 pg/ml) in WT control mice. Data are the mean of nine animals in each group (*, P < 0.01). (B) T. spiralis-infection-stimulated IL-13 levels were markedly decreased in α/β/γ/δ TCR–/– mice, whereas they remained high in WT control mice. Data are the mean of three animals in each group (*, T.s. vs. control, P < 0.05; †, T cell KO vs. T cell WT, P < 0.01).

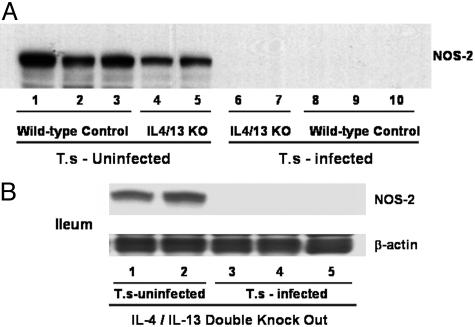

It has been well demonstrated that compensatory mechanisms play an important role in the induction of cytokine-regulated immune activation (28). Our data (Fig. 4A) showing that T. spiralis infection can significantly increase the production of IL-13 in mice that lack endogenous IL-4 further suggested the existence of another mechanism or pathway. During the course of our experiments, McKenzie's group (28) published a study characterizing Th2-mediated immune responses by using several combined Th2 cytokine-deficient mice. To further investigate whether endogenous IL-4 and IL-13 are important for NOS-2 down-regulation, we obtained IL-4/IL-13 double-knockout mice, with permission from A. N. McKenzie, and evaluated ileal NOS-2 expression after T. spiralis infection (Fig. 5). Despite the combined disruption of the IL-4/IL-13 genes, T cell numbers and the lymphoid organ composition of the mice were normal (28), and no severe sickness was observed after T. spiralis infection. Similar to IL-4 KO mice, NOS-2 was observed in the ileum of IL-4/IL-13–/– mice (Fig. 5). After infection with T. spiralis for 8 days, NOS-2 expression in the ileum of IL-4/IL-13–/– mice was almost abolished (Fig. 5). Thus, the host IL-4Rα/Stat6 signaling pathway is activated even without endogenous production of both IL-4 and IL-13 during the T. spiralis-induced NOS-2 down-regulation pathway.

Fig. 5.

Deficiency of both endogenous IL-4 and IL-13 failed to affect T. spiralis-induced inhibition of NOS-2. (A) Immunoblotting for NOS-2 in ileum from IL-4–/–/IL-13–/– and WT control mice. (B) Immunoblotting for NOS-2 and β-actin in ileum from IL-4–/–/IL-13–/– mice. Each indicated lane number represents an individual animal used in the experiment. Ileal NOS-2 expression was abolished after 9 days of T. spiralis infection in both IL-4–/–/IL-13–/– (A, lanes 6 and 7) and WT control (A, lanes 8–10) mice. The same sample was blotted with anti-β-actin (45 kDa) antibody, and no inhibition was observed (B).

Inhibition of NOS-2 Expression by a T. spiralis-Secreted Substance(s). We cultured T. spiralis in vitro, collected the adult/new born larvae-culture medium (NBL; see Methods) and tested whether a worm-secreted substance would inhibit NOS-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells. In brief, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 1.0 ml of NBL medium (10% vol/vol) or control RPMI medium 1640 for 36 h. Then, LPS (50 and 100 ng/ml) was added to induce NOS-2. As demonstrated in Fig. 6A, treatment with NBL medium inhibited LPS (50 ng/ml)-stimulated NOS-2 expression by 100%. Increasing the concentration of LPS to 100 ng/ml only partially overcame the inhibition by worm-cultured medium [expression in response to 100 ng/ml LPS was still <50% of the expression in response to LPS (50 ng/ml) in control medium]. Our in vivo study (8) demonstrated that T. spiralis-induced NOS-2 inhibition is highly selective and does not extend to the expression of COX-2. We used the same cell lysates to observe protein expression of COX-2. The worm-cultured medium did not affect LPS-induced COX-2 expression (Fig. 6).

We previously showed (8) that infection of mice with T. spiralis resulted in a significant reduction of steady-state levels of NOS-2 mRNA. Therefore, we determined the effect of T. spiralis culture medium on the expression of NOS-2 mRNA in RAW264.7 cells by using real-time quantitative PCR. A significant decrease in LPS-stimulated NOS-2 mRNA was observed after a 36-h treatment with NBL medium (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

Maintaining an appropriate balance between proinflammatory responses to eliminate infectious agents and antiinflammatory responses to limit the damage to either host or pathogen is an important feature of many host–parasite relationships. Substantial evidence indicates that immunoregulatory cytokines exert a wide variety of effects on those processes. Our interest in understanding the mechanisms underlying the cross-talk between parasite and host arises because gastrointestinal roundworm parasites, including T. spiralis, infect approximately one billion people worldwide and are believed to cause approximately one million deaths annually (29). In addition, elucidation of the mechanisms could lead to the development of new strategies for the therapy of various inflammatory pathological conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (30), and could also offer more information on the hygiene hypothesis that has been very influential in directing strategies to prevent allergic diseases (4).

We have previously demonstrated (8) that ongoing gut inflammatory reactions induced by certain roundworms can set into motion systemically operated mechanisms that down-regulate NOS-2 expression. Host responses to gastrointestinal nematode infection have been shown to be mediated by CD4+ Th cells that can be activated as early as 12 h after T. spiralis infection (31). CD4+ Th cells can be divided into two basic subsets, Th1 and Th2, based on their cytokine secretion profile. Th2 cell responses are involved in host immunity provoked by T. spiralis, and IL-4 is the primary cytokine released by Th2 lymphocytes (11). Although it is clear that both proinflammatory (Th1) and antiinflammatory (Th2) cytokines are actively involved in the regulation of NOS-2 expression, the effects of IL-4 on NO production are not clear-cut. IL-4 has been reported to inhibit NO production by stimulating arginase expression that results in the depletion of l-arginine, the substrate for NOS to make NO (32). In our model, NOS-2 down-regulation is due to a decease in steady-state NOS-2 mRNA levels (8), making it unlikely that the NOS-2-inhibitory effect of IL-4 is due to NOS-2-substrate depletion.

The production of IL-4 can be induced in T cells and highly induced in differentiated Th2 cells (33). The gastrointestinal tract is one of the largest immunological organs of the body, containing more lymphocytes and plasma cells than the spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes combined (23). The intestinal epithelial cells are in intimate contact with T cells within the epithelial compartment and function as antigen-presenting cells to regulate T cell responses in the intestinal mucosa. The unique intraepithelial location of T. spiralis maximizes the stimulation of T cells after infection (34). Thus, one would predict that activated T cells most likely are the major sources of Th2 cytokine expression after T. spiralis infection. Therefore, it was surprising that T. spiralis infection still resulted in down-regulation of NOS-2 in the various T cell-deficient mice (Fig. 2).

Equally surprising was the observation that T. spiralis infection activated IL-4Rα/Stat6 signaling that did not require host production of either IL-4 or IL-13 (Figs. 3 and 5). Furthermore, T. spiralis-secreted substances also inhibited LPS-stimulated NOS-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 6). Thus, we propose that an undefined substance could be involved in the IL-4Rα/Stat6 stimulating pathway activated during T. spiralis-induced inhibition of NOS-2.

An additional important finding is that a deficiency of endogenous IL-4 did not dramatically affect the production of IL-13 (Fig. 4A). Although IL-4 is thought to be a critical factor for the regulation of T cell commitment to the CD4+ Th2 phenotype, a number of in vivo as well as in vitro studies have placed this concept in doubt. First, it has been reported that IL-4/IL-4R-deficient mice were able to produce Th2 cytokines in response to parasites infections and to soluble protein antigen injection (35–38). Second, Th2 cytokine production by both IL-4 and IL-4Rα knockout mice was suggested to originate from Th0 lymphocytes or unconventional CD4+ T cells (e.g., natural killer T cells) (38). Our data support the recent findings of an IL-4/IL-4R-signaling-independent pathway for the up-regulation of Th2 cytokines because in helminth-infected IL-4 knockout mice, IL-13 levels are high (Fig. 4A). However, we also find that T cell development is important because the expression of IL-13 is inhibited after the infection in T cell-deficient animals (Fig. 4B).

In summary, our current study with a variety of genetically modified mice sheds light on the complex immune responses controlling parasite infection and demonstrates an IL-4/Stat6-dependent and T cell-independent pathway that down-regulates NOS-2 expression during parasite-induced gut inflammation. We propose that a previously uncharacterized substance could be involved in the IL-4Rα/Stat6-stimulating pathway during host–parasite interaction. The presence of this substance(s) in T. spiralis culture medium should help to identify and characterize this material. The information obtained from the present study will be useful for exploring new strategies to effectively control unbalanced NO production that is broadly involved in multiple pathological conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NL64221, GM061731, and P30DK56338; the John S. Dunn, Harold and Leihla Mathers, and Robert A. Welch Foundations; the U.S. Army Department of Defense; the Texas Gulf Coast Digestive Diseases Center; and the University of Texas.

Author contributions: K.B., Y.H., N.W., and F.M. designed research; K.B., M.Z., Y.H., and M.L. performed research; K.B. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; K.B., M.Z., Y.H., M.L., and F.M. analyzed data; and K.B., N.W., and F.M. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; IL-4Rα, IL-4 receptor α-subunit; NBL, newborn larvae; NOS, NO synthase; PI, postinfection; Th, T helper.

References

- 1.Finkelman, F. D., Pearce, E. J., Urban, J. F., Jr., & Sher, A. (1991) Immunol. Today 12, A62–A66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garside, P., Kennedy, M. W., Wakelin, D. & Lawrence, C. E. (2000) Parasite Immunol. 22, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelman, F. D. & Urban, J. F., Jr. (2001) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 107, 772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yazdanbakhsh, M., Kremsner, P. G. & van Ree, R. (2002) Science 296, 490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bian, K. & Murad, F. (2003) Frontiers Biosci. 8, d264–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogdan, C. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman, J. W. (2001) Int. Immunopharmacol. 1, 1397–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bian, K., Harari, Y., Zhong, M., Lai, M., Castro, G., Weisbrodt, N. & Murad, F. (2001) Mol. Pharmacol. 59, 939–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenzie, G. J., Fallon, P. G., Emson, C. L., Grencis, R. K. & McKenzie, A. N. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 189, 1565–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue, Y., Konieczny, B. T., Wagener, M. E., McKenzie, A. N. & Lakkis, F. G. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 1125–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramaswamy, K., Negrao-Correa, D. & Bell, R. (1996) J. Immunol. 156, 4328–4337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisbrodt, N. W., Pressley, T. A., Li, Y. F., Zembowicz, M. J., Higham, S. C., Zembowicz, A., Lodato, R. F. & Moody, F. G. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, G454–G460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grencis, R. K. (1997) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 352, 1377–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urban, J. F., Jr., Madden, K. B., Svetic, A., Cheever, A., Trotta, P. P., Gause, W. C., Katona, I. M. & Finkelman, F. D. (1992) Immunol. Rev. 127, 205–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boothby, M., Mora, A. L., Aronica, M. A., Youn, J., Sheller, J. R., Goenka, S. & Stephenson, L. (2001) Immuol. Res. 23, 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chilton, P. M. & Fernandez-Botran, R. (1997) Cell. Immunol. 180, 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izuhara, K., Heike, T., Otsuka, T., Yamaoka, K., Mayumi, M., Imamura, T., Niho, Y. & Harada, N. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 619–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan, E. D. & Riches, D. W. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 253, 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai, S. H., Lin-Shiau, S. Y. & Lin, J. K. (1999) Br. J. Pharmacol. 126, 673–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urban, J. F., Jr., Schopf, L., Morris, S. C., Orekhova, T., Madden, K. B., Betts, C. J., Gamble, H. R., Byrd, C., Donaldson, D., Else, K. & Finkelman, F. D. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 2046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akira, S. (1999) Stem Cells 17, 138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jankovic, D., Sher, A. & Yap, G. (2001) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro, G. A. & Harari, Y. (1991) Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 95, 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha, B., Vassalli, P. & Guy-Grand, D. (1992) Immunol. Today 13, 449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poussier, P. & Julius, M. (1994) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12, 521–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bozic, F., Forcic, D., Mazuran, R., Marinculic, A., Kozaric, Z. & Stojcevic, D. (1998) Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21, 201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izuhara, K. & Shirakawa, T. (1999) Int. J. Mol. Med. 3, 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallon, P. G., Jolin, H. E., Smith, P., Emson, C. L., Townsend, M. J., Fallon, R. & McKenzie, A. N. (2002) Immunity 17, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelman, F. D., Shea-Donohue, T., Goldhill, J., Sullivan, C. A., Morris, S. C., Madden, K. B., Gause, W. C. & Urban, J. F., Jr. (1997) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 505–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott, D. E., Urban, J. J., Argo, C. K. & Weinstock, J. V. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 1848–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, C. H., Richards, E. M. & Bell, R. G. (1999) Cell. Immunol. 193, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutschman, R., Lang, R., Hesse, M., Ihle, J. N., Wynn, T. A. & Murray, P. J. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 2173–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul, W. E. (1997) Ciba Found. Symp. 204, 208–16; discussion 216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castro, G. A. & Harari, Y. (1982) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 6, 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopf, M., Le Gros, G., Bachmann, M., Lamers, M. C., Bluethmann, H. & Kohler, G. (1993) Nature 362, 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brewer, J. M., Conacher, M., Satoskar, A., Bluethmann, H. & Alexander, J. (1996) Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 2062–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noben-Trauth, N., Paul, W. E. & Sacks, D. L. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 6132–6140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankovic, D., Kullberg, M. C., Noben-Trauth, N., Caspar, P., Paul, W. E. & Sher, A. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 3047–3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]