Abstract

Adolescent exposure to risk in film has been associated with behavior. We coded Black and White character involvement in sex, violence, alcohol use, and tobacco use, and combinations of those behaviors in popular mainstream and Black-oriented films (film n = 63, character n = 426). Health risk portrayals were common, with the majority of characters portraying at least one. Black characters were more likely than Whites to portray sex and alcohol use, while White characters were more likely to portray violence. Within-segment combinations of sex and alcohol were more prevalent for Black characters, while violence and alcohol were more prevalent for Whites. Throughout a film, Black characters were more likely than White characters to portray sex and alcohol, sex and tobacco, and alcohol and tobacco. Risky behaviors are prevalent, but types portrayed differ between Black and White characters. This may have implications for health disparities in Black and White adolescents.

Adolescents in the United States spend nearly 9 hours per day engaging with entertainment media, and films and television remain popular media sources (Rideout, 2015). Adolescents watch an average of 31 films per year—more than any other age group (Nielsen, 2010). In many of these films, adolescents are exposed to portrayals of sex, violence, alcohol use, and tobacco use (Bleakley, Jamieson, & Romer, 2012; Gunasekera, Chapman, & Campbell, 2005; Worth, Chambers, Nassau, Rakhra, & Sargent, 2008). Social cognitive theory predicts that media can influence behavior by modifying risk-relevant cognitions and emotions and also through modeling “scripts” for behavior (Bandura, 2001). This influence has been documented across a variety of domains in adolescent health (Strasburger, Jordan, & Donnerstein, 2010).

Exposure to sexual content in media is associated with intention to engage in sexual intercourse (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2011), earlier sex initiation (O’Hara, Gibbons, Gerrard, Li, & Sargent, 2012), sexual risk taking (O’Hara et al., 2012), and progression of sexual activity (Hennessy, Bleakley, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2009). Media violence is associated with aggressive behavior and cognitions and decreased school performance (Anderson et al., 2003; Bushman & Huesmann, 2006; Çetin, Lull, Çelikbaş, & Bushman, 2015). Also in this domain, there is evidence that the MPAA ratings system does little to decrease adolescent exposure to violence in movies—there is not much difference in violence between PG-13 rated films and R-rated films (Nalkur, Jamieson, & Romer, 2010). Exposure to alcohol in media is associated with increased alcohol use (Dal Cin et al., 2009) even for those at lowest risk for alcohol initiation (Hanewinkel et al., 2014). Tobacco use in media is associated with higher receptivity to smoking (Sargent et al., 2002) and smoking initiation (Sargent et al., 2005). Along with these specific effects (e.g., alcohol exposure influences alcohol-related behavior), it is also possible to find cross-behavioral effects (e.g., alcohol exposure influences other risk behaviors). One study found evidence for specific and cross-behavioral effects of exposure to alcohol and sex in media on later alcohol consumption and sexual behavior among adolescents (O’Hara, Gibbons, Li, Gerrard, & Sargent, 2013).

Cross-behavioral influences are likely because many media risk portrayals are not limited to single occurrences. Characters often engage in more than one risk behavior. James Bond drinks a martini, fights the antagonist’s henchmen, and sleeps with a Bond girl all in the same film—sometimes within the span of a few minutes. There is research suggesting that adolescent risk behaviors cluster, such that adolescents who are more risky in one area are more likely to be risky in another (DuRant, Smith, Kreiter, & Krowchuk, 1999). There is also evidence of adolescents combining risk behaviors in a single setting. For example, 22.4% of sexually active adolescents reported drinking alcohol or using drugs before their most recent sexual intercourse (Kann et al., 2014). Combinations of risk behaviors like this are common in media as well. A content analysis of reality television found that alcohol use was correlated with sexual behavior and tobacco use (Flynn, Morin, Park, & Stana, 2015). Another study found that more than three quarters of popular films involved a violent character engaging in at least one other risk behavior (Bleakley, Romer, & Jamieson, 2014).

It is important to note that adolescent media exposure is heterogeneous. Specifically, Black adolescents watch more than twice as much television and movies as White adolescents (Ellithorpe & Bleakley, 2016; Jordan et al., 2010; Rideout, 2015), are more likely to have a television in their bedroom, and are more likely to report that the television is on all the time in their home (Jordan et al., 2010; Rideout, 2015). The denser media diet of Black adolescents also includes more Black characters (Ellithorpe & Bleakley, 2016). Black and White adolescents may therefore be differentially exposed to risk behaviors portrayed by Black and White characters.

Black and White adolescents are also different in many health-related domains. Black adolescents are more likely than White adolescents to have been in a physical fight, to have engaged in sexual intercourse, to initiate sex earlier, and to have had four or more sex partners (Kann et al., 2014),while White adolescents are more likely than Black adolescents to have carried a weapon, to have tried smoking, and to currently smoke (Kann et al., 2014). Additionally, although Black adolescents tend to initiate alcohol use at a younger age, White adolescents report higher sustained rates of alcohol consumption and are more likely to report binge drinking behaviors (Kann et al., 2014). Media exposure is often differentially associated with these likelihoods for Black and White adolescents. Exposure to alcohol in media is more strongly associated with alcohol use for White than for Black adolescents (Gibbons et al., 2010). Similarly, exposure to sexual content in media is predictive of subsequent sexual behavior for White but not Black adolescents (Hennessy et al., 2009). The same pattern is found for the relationship between exposure to smoking in media and smoking behavior (Jackson, Brown, & L’Engle, 2007). Thus, Black adolescents tend to watch more film and television than White adolescents, but seem to be less influenced by media depictions of risky health behaviors.

One explanation for this mismatch between exposure and effects is that media exposure studies often neglect to consider the attributes of the characters modeling the behaviors. Previous work suggests that Black adolescents are more likely to be influenced by Black models than by White ones (Appiah, 2001). Black adolescents also tend to identify with and pay more attention to Black exemplars— especially when the adolescent has strong ethnic identity (Appiah, 2001, 2004). A few studies have examined “Black-oriented” media which have a higher proportion of Black characters than mainstream media (Schooler, 2008; Schooler, Ward, Merriwether, & Caruthers, 2004) and which often include themes of Black culture or concerns (Allen, Dawson, & Brown, 1989; Sheridan, 2006). Such films tend to be targeted and marketed toward primarily Black audiences (Dal Cin, Stoolmiller, & Sargent, 2013; Darden & Bayton, 1977). Young Black women had more positive body image when they viewed Black-oriented content, but were unaffected by mainstream content (Schooler et al., 2004). Furthermore, smoking initiation in Black adolescents was predicted by exposure to smoking in Black-oriented media, but not by exposure to smoking in mainstream media (Dal Cin et al., 2013). These findings suggest that not only is it important to consider the risk behaviors portrayed in media, but also to consider attributes of the characters engaging in them and of the adolescents exposed to them.

The Current Study

Because risk behaviors in media can affect adolescent health, we examined the prevalence of sex, violence, alcohol use, and tobacco use in popular film. We also examined the extent to which combinations of risk behaviors (e.g., sex and alcohol) were portrayed both within a five-minute segment (e.g., a character drank alcohol and had sex in the same scene) and within the entire duration of a film (e.g., the same character drank alcohol at one point in the film and later had sex). The importance of character race in the relationship between media portrayals and health behaviors led us to also sample Black-oriented films in addition to mainstream ones. The inclusion of Black-oriented films served to increase the number of Black characters in the sample, allowing us to compare how Black and White characters engaged in risky behaviors.

Method

Film Selection Procedures

The top 30-grossing films of 2014 according to Variety magazine were selected as representing popular mainstream films, in accordance with previous research (Jamieson & Romer, 2008). The mainstream films coded represented $5,447,217,180 in gross revenue, which was 48.95% of the $11,127,600,000 grossed by all films in 2014. Selection of “Black-oriented content” was more complicated. We decided a priori that an inclusive definition of Black-oriented was the goal, as there is some disagreement in both research and popular culture regarding the definition. Some argue that having a predominantly Black cast is sufficient to call content Black-oriented (Schooler, 2008; Schooler et al., 2004). Others say that the selected film also must include narrative themes of race, racism, or Black culture (Jones, 1990). Others suggest that the content should either have a predominantly Black cast or it should cover Black themes, but does not necessarily need to do both (Allen et al., 1989; Sheridan, 2006). Still others propose a marketing component (Dal Cin et al., 2013; Darden & Bayton, 1977). Since the common denominator is a predominantly Black cast, we began there. For the purposes of the present study, “predominantly” was defined as 50% or greater of the main characters. We also allowed for the possibility that some films would not meet this criterion but might meet the criterion for Black themes and/or targeting and should therefore be included to allow for a larger variety of film in the category.

We began with a pool of the 500 highest grossing films for 2013 and 2014 (1,000 total) according to www.boxofficemojo.com, which provides information about every movie commercially shown in a given year, not just the top-grossing ones.1 Potential Black-oriented films were identified based on the proportion of characters who were Black. All films with at least two Black characters in the top eight-billed cast were selected for further scrutiny (n = 40). Possible Black-oriented films included 21 films from 2013 and 19 films from 2014. These 40 films were coded by the trained coders; this more official coding indicated that in actuality 30 films had a cast of at least 50% Black characters (Schooler et al., 2004). Three films that did not have predominantly Black casts (42 (38% Black cast), 12 Years a Slave (29% Black cast), and Fruitvale Station (33% Black cast) but covered Black or racial themes were added to the list (Allen et al., 1989; Sheridan, 2006). Finally, one film that was originally coded with the mainstream films (Ride Along) met the criterion for a predominately Black cast (50%). Thus, the final sample included 29 mainstream films and 34 Black-oriented films.

Coding of Content

The films were coded in their entirety by five trained coders in five-minute segments (n = 1,510) using a directed, quantitative, previously-validated coding scheme (Bleakley et al., 2012, 2014; Jamieson & Romer, 2008; Nalkur et al., 2010). After multiple sessions of training, the coders achieved inter-coder reliability as calculated by Krippendorff’s alpha using a separate, previously validated test sample of 59 segments before coding the films independently.

Characters

There were 426 main characters coded across the 63 films. Main character was defined by cross-checking official listings on DVD cases and IMDB.com for up to eight top-billed cast members. If fewer than eight cast members were listed on the DVD case or on IMDB.com, then that number was the number used. In mainstream films (n = 215 characters), 75.3% of characters were White, 5.1% were Black, and 19.6% were another group (including non-humans). In Black-oriented films (n = 211 characters), 20.9% of characters were White, 75.4% were Black, and 3.7% were another group. Krippendorff’s α (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) for character race was 0.93. Characters coded as “other” were excluded, and character race was dichotomized (White = 0, Black = 1).

Single Risk Behaviors

Each segment was coded for whether each main character was involved in the portrayal of sex, violence, alcohol, and tobacco. Dichotomous variables were then created indicating whether each character was involved in a given behavior at any point throughout the film. Reported reliabilities are for the presence of the behavior in the segment. Sexual behavior was defined as any type of sexual contact, ranging from kissing on the lips to explicit intercourse (Krippendorff’s α = 0.93). Violence was defined as intentional acts to inflict injury or harm (Krippendorff’s α = 0.94). Aggression in sports games (e.g., tackling, boxing) was excluded. Both the character initiating and the character receiving were coded as being involved in violence. Alcohol portrayal was defined as a character being directly involved any activity related to alcohol, ranging from handling of bottles to observed consumption (Krippendorff’s α = 0.94). Tobacco portrayal was similarly defined, ranging from character handling of smoking paraphernalia to explicit use (Krippendorff’s α = 0.84). An overall variable indicating whether any main character engaged in any of the four risk behaviors was also created (0 = involved in none of the four behaviors, 1 = involved in one or more).

Within-Segment Combinations

Combined behaviors on the segment level were when the same character was coded as engaging in more than one risk behavior in a five-minute segment. The possible combinations were sex and violence, sex and alcohol, sex and tobacco, violence and alcohol, violence and tobacco, and alcohol and tobacco. For example, when Amy Dunne in Gone Girl murdered a character shortly after engaging in sexual intercourse with him, it was coded as a segment-level combination of sex and violence. A variable indicating whether a character engaged in any within-segment combination was also created (0 = involved in none of the possible within-segment combinations, 1 = involved in one or more within-segment combination).

Within-Film Combinations

Behavioral combinations within film were defined as occurring when the same character was coded as engaging in more than one behavior at any point in the film. For example, Nick Dunne in the film Gone Girl drinks alcohol at a party early in the film, and later in the film engages in sexual intercourse. This would be coded as a film-level combination of sex and alcohol. Segment-level combinations are also included in the film level, as they are technically still combinations within the film. The possible film-level combinations are the same as the segment-level combinations. A variable indicating whether a character engaged in any within-film combination was also created (0 = involved in none of the possible within-film combinations, 1 = involved in one or more within-film combination).

Statistical Analysis

The unit of analysis was a character. Logistic regression analysis was conducted in Stata 13.0 to test for differences in portrayals by White and Black characters. Character race was the independent variable, and character behavior was the dependent variable. Clustering was used to adjust standard errors to account for the fact that multiple characters appeared in each film. Thus, variations between films should not be as impactful as character-level variation. All confidence intervals define a 5% type 1 (alpha) error. The unequal distribution of race in mainstream and Black-oriented films (i.e., only 11 Black characters in the mainstream films) prohibited testing for interactions between character race and film classification, as nearly all Black characters appeared in Black-oriented films and nearly all White characters appeared in mainstream films.

Results

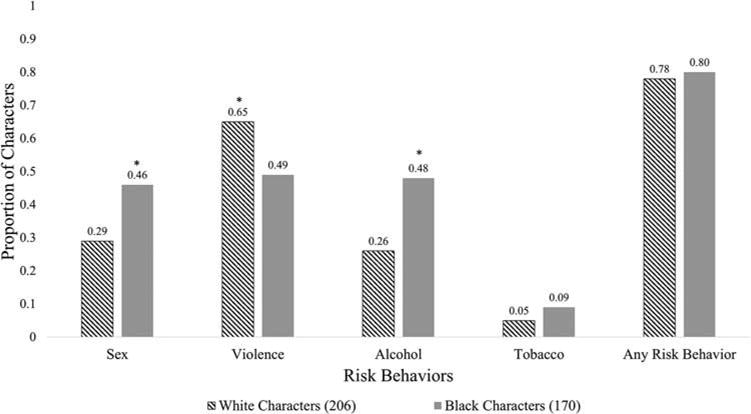

More than three quarters of Black and White characters engaged in at least one risk behavior. Twenty percent of White characters and 25% of Black characters portrayed at least one behavioral combination at the segment level. Additionally, 35% of White characters and 51% of Black characters engaged in at least one combination of behaviors at the film level. Details about the prevalence of risk behaviors and combinations can be found in Figures 1 through 4.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of characters engaging in single risk behaviors.

Fig. 4.

Proportion of characters engaging in risk behaviors alone and in combination with other behaviors.

Regression Analysis

Logistic regression showed that when looking at all risk behaviors combined, the likelihood of engaging in any one risk behavior is no different for Black and White characters, OR = 1.12, CI(0.65, 1.91). However, there were differences between Black and White characters when the risk behaviors are broken down by behavior type. Black characters were more likely than White characters to engage in sexual behavior, OR = 2.16, CI(1.26, 3.71) and to consume alcohol, OR = 2.63, CI(1.46, 4.73). However, White characters were more likely than Black characters to engage in violence, OR = 0.54, CI(0.31, 0.93). There was no significant difference between Black and White characters’ involvement with tobacco—though this is possibly due to the small number of tobacco occurrences, OR = 1.90, CI(0.87, 4.15).

Analyses on the within-segment combinations indicated that the likelihood of engaging in any segment-level combination was not significantly different for Black and White characters, OR = 1.36, CI(0.73, 2.53). However, there were differences in portrayals of specific combinations. Black characters were more likely than White characters to combine sexual behavior and alcohol use in the same segment, OR = 2.33, CI(1.04, 5.24). White characters were more likely than Black characters to combine violence and alcohol use in the same segment OR = 0.29, CI(0.09, 0.95). There was no significant difference between Black and White characters in their likelihood of combining sexual behavior and violence in the same segment, OR = 0.55, CI(0.23, 1.30), combining violence and tobacco use in the same segment, OR = 0.81, CI(0.21, 3.14), or combining alcohol use and tobacco use in the same segment, OR = 3.73, CI (0.71, 19.50). The likelihood of combining sexual behavior and tobacco could not be tested in logistic regression because White characters had no incidences of the combination.

Within-film behavioral combinations were more likely to be portrayed by Black characters as compared to White characters, OR = 1.95, CI(1.24, 3.06). More specifically, Black characters were more likely than White characters to combine sexual behavior and alcohol use within-film, OR = 2.76, CI (1.29, 5.89), to combine sexual behavior and tobacco use within-film, OR = 3.73, CI(1.10, 12.68), and to combine alcohol use and tobacco use within-film, OR = 3.05, CI(1.07, 8.70). There was no significant difference between Black and White characters in their likelihood of combining sexual behavior and violence within-film, OR = 1.29, CI(0.70, 2.35), combining violence and alcohol use within-film, OR = 1.77, CI(0.89, 3.51), or combining violence and tobacco use within-film, OR = 1.22, CI(0.43, 3.45).

Discussion

Early initiation of risk behaviors in adolescence is predictive of escalation of negative behaviors and of poor health outcomes later in life (Bushman & Huesmann, 2006; Grant, Stinson, & Harford, 2001). There is strong evidence for a relationship between adolescents’ media exposure to risk behaviors such as sex, violence, alcohol use, and tobacco use, and their subsequent behaviors (Bleakley et al., 2011; Bushman & Huesmann, 2006; Dal Cin et al., 2013). The present study examined portrayals in films, and whether they varied by character race. The results suggest that risk behaviors are commonly portrayed with most characters, regardless of race, engaging in at least one risk behavior. However, when examining specific behaviors, Black characters were more likely to be involved in sex and alcohol use, and White characters were more likely to be involved in violence. There were also differences between Black and White characters with regard to portrayals of behavioral combinations. Black characters were more likely than White characters to engage in any film-level combination overall, and to be involved in combinations of sex and alcohol both within segment and within film. Black characters were also more likely to engage in combinations of sex and tobacco and of alcohol and tobacco within film, whereas on the segment level, White characters were more likely to engage in violence and in combinations of violence and alcohol.

Black and White adolescents respond differently to Black and White characters (Appiah, 2001, 2004) with Black adolescents typically identifying more strongly with Black characters (Appiah, 2004; Dal Cin et al., 2013; Schooler et al., 2004). Therefore, differences in risk portrayals by Black and White characters are likely important for predicting the relationship between media exposure and adolescent behavior. In addition, Black and White adolescents are differentially susceptible to certain risk behaviors (Kann et al., 2014) and media portrayals have the potential either to reduce or exacerbate those disparities (Keller & Brown, 2002). Exacerbation effects may be especially worrisome for sexual behaviors because Black characters were more likely than White characters to portray sexual behavior either alone or in combination with substance use. This could possibly reinforce the disparity that already exists, wherein Black adolescents engage in riskier sex behaviors than White adolescents do (Kann et al., 2014).

Single risk behaviors can have domain specific as well as general effects (O’Hara et al., 2013). Similarly, combinations of risk could also influence behavior in both specific and general ways. Interestingly, while the segment-level differences in combination behavior were fairly balanced between Black and White characters, with Black characters portraying more risk in some domains and White characters portraying more risk in other domains, the film-level differences were all driven by more risk combination portrayals by Black characters. This suggests that, across an entire film, Black adolescents may be more likely to be exposed to more global risk combinations than White adolescents. Behavioral co-occurrence is often presented as global or situational (Cooper, 2002). “Global overlap” (Leigh & Stall, 1993), which is more related to film-level combinations, refers to the extent to which an individual performs both behaviors (e.g., an individual who both drinks alcohol and has sex), and whether there is a general increase in the likelihood of performing one in the future based on the performance of the other (Cooper, 2002). Situational co-occurrence, however, is more related to segment-level combinations. Situational co-occurrence is much more specific, such that the behaviors occur at the same time or on the same occasion. It is possible that portrayals of global combinations and specific combinations may have different behavioral effects, in part because of the specificity with which adolescents would likely learn scripts for behavior. Exposure to characters combining sex and alcohol, for example, could predict adolescents’ likelihood of combining of sex and alcohol in the same setting. However, it could also predict the likelihood of being risky in general, or other novel combinations of risk behaviors. Future research should examine these possibilities more closely.

Limitations and Future Research

This study had a limited sample of films. Films not coded because they were not in the top 30 nonetheless could have been popular with adolescents. That said, the 29 mainstream films coded constituted nearly half of the gross revenue for all films in 2014, indicating that they likely had extensive reach. Additionally, in order to sample enough Black-oriented films, we had to include some low revenue films that may have had lower adolescent exposure. Another limitation is in our ability to predict adolescent behavior from exposure to the behaviors depicted in media. Some scholars have questioned the power of causal predictions in public health, especially when considering historical and cultural variables as antecedents (Steinberg & Monahan, 2011). However, most evidence for media influence and adolescent health is consistent with at least some causal role for media (Anderson et al., 2003; Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2008; Sargent et al., 2005). In addition, although film-level combinations were more numerous than segment-level ones, it is possible that the temporal distance between portrayed behaviors may decrease the likelihood that adolescents pick up the scripts and cognitions that would predict later re-enactment of the behaviors. Finally, we do not have information on the context of the behavioral portrayals in the present analysis. Previous work on adolescent exposure to risk in media has found evidence for influence of exposure on risky behavior regardless of portrayal context (Bleakley et al., 2008, 2011; Brown et al., 2006). Therefore, although the impact of the risks in the present data may be moderated by contextual factors, there remains an expectation that there will be some baseline influence regardless of that contextual information.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that characters in film frequently engage in risky health behaviors and often combine those behaviors onscreen. The implications of adolescent exposure to these risks, and especially to their combinations, should be addressed. For example, drinking alcohol in conjunction with sexual activity is a combination prevalent among adolescents (Kann et al., 2014) and among media characters, yet the influence of media on these behavioral combinations in not well understood. Furthermore, it should also be noted that the types of behaviors portrayed tend to differ for Black and White characters, with Black characters more likely to enact behaviors and combinations related to sex and alcohol and White characters more likely to engage in violence. This finding has potential implications for health disparities in Black and White adolescents. For example, Black adolescents are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors at a younger age compared to their White peers (Kann et al., 2014), and this may be reinforced by their increased likelihood of exposure to sexual behaviors portrayed by Black characters. Exposure to film characters that portray risk may therefore be an important factor to consider in predicting adolescent susceptibility to engage in risk behaviors and their combinations.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of characters engaging in segment-level combinations of risk behaviors.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of characters engaging in film-level combinations of risk behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (Grant Number 1R21HD079615). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD.

Footnotes

www.boxofficemojo.com was used for the Black-oriented films instead of Variety magazine because Variety only includes the top 100-grossing films for the year. Many Black-oriented films are low earners at the box office, and those films would have been excluded if relying on Variety alone, leaving very few Black-oriented films for coding.

References

- Allen RL, Dawson MC, Brown RE. A schema-based approach to modeling an African-American racial belief system. American Political Science Review. 1989;83:421–441. doi: 10.2307/1962398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Berkowitz L, Donnerstein E, Huesmann LR, Johnson JD, Linz D, Wartella E. The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(3):81–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2003.pspi_1433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appiah O. Ethnic identification on adolescents’ evaluations of advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research. 2001;41(5):7–22. doi: 10.2501/JAR-41-5-7-22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appiah O. Effects of ethnic identification on web browsers’ attitudes toward and navigational patterns on race-targeted sites. Communication Research. 2004;31(3):312–337. doi: 10.1177/0093650203261515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology. 2001;3:265–299. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. It works both ways: The relationship between exposure to sexual content in the media and adolescent sexual behavior. Media Psychology. 2008;11(4):443–461. doi: 10.1080/15213260802491986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Using the Integrative Model to explain how exposure to sexual media content influences adolescent sexual behavior. Health Education and Behavior. 2011;38(5):530–540. doi: 10.1177/1090198110385775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Jamieson PE, Romer D. Trends of sexual and violent content by gender in top-grossing US films, 1950-2006. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Romer D, Jamieson PE. Violent film characters’ portrayal of alcohol, sex, and tobacco-related behaviors. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):71–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: Exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts back and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Huesmann LR. Short-term and long-term effects of violent media on aggression in children and adults. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(4):348. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çetin Y, Lull RB, Çelikbaş M, Bushman BJ. Exposure to violent and sexual media content undermines school performance in youth. Advances in Pediatric Research. 2015;2(6):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;(14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Stoolmiller M, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in movies and smoking initiation among black youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(4):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Gerrard M, Gibbons F, Stoolmiller M, Wills TA, Sargent JD. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes, and peer affiliations mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden BJ, Bayton JA. Self-concept and Blacks’ assessment of Black leading roles in motion pictures and television. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1977;62(5):620. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.62.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153(3):286. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellithorpe ME, Bleakley A. Wanting to see people like me? Racial and gender diversity in popular adolescent television. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Online First. 2016;45:1426–1437. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0415-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn MA, Morin D, Park SY, Stana A. “Let’s get this party started!”: An analysis of health risk behavior on MTV reality television shows. Journal of Health Communication. 2015;20(12):1382–1390. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F, Pomery E, Gerrard M, Sargent J, Weng CY, Wills T, Stoolmiller M. Media as social influence: Racial differences in the effects of peers and media on adolescent alcohol cognitions and consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(4):649. doi: 10.1037/a0020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson F, Harford T. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: A 12-year follow-up. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13(4):493–504. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekera H, Chapman S, Campbell S. Sex and drugs in popular movies: An analysis of the top 200 films. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2005;98:464–470. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.10.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Hunt K, Sweeting H, Engels RC, Scholte RH, Morgenstern M. Portrayal of alcohol consumption in movies and drinking initiation in low-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):973–982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Krippendorff K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures. 2007;1(1):77–89. doi: 10.1080/19312450709336664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Estimating the longitudinal association between adolescent sexual behavior and exposure to sexual media content. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46(6):586–596. doi: 10.1080/00224490902898736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Brown JD, L’Engle KL. R-rated movies, bedroom televisions, and initiation of smoking by white and black adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(3):260–268. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson P, Romer D. The changing portrayal of adolescents in the media seince 1950. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jones FG. The Black audience and the BET channel. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1990;34(4):477–486. doi: 10.1080/08838159009386756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Bleakley A, Manganello J, Hennessy M, Stevens R, Fishbein M. The role of television access in the viewing time of US adolescents. Journal of Children and Media. 2010;4(4):355–370. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2010.510004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, Chyen D. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63(Suppl 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S, Brown J. Media interventions to promote responsible sexual behavior. The Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):67–72. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48(10):1035. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalkur PG, Jamieson PE, Romer D. The effectiveness of the motion picture association of America’s rating system in screening explicit violence and sex in top-ranked movies from 1950 to 2006. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(5):440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen. How teens use media: A Nielsen report on the myths and realities of teen media trends. 2010 Oct 7; Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2009/How-Teens-Use-Media.html.

- O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Li Z, Sargent JD. Greater exposure to sexual content in popular movies predicts earlier sexual debut and increased sexual risk taking. Psychological Science. 2012;23(9):984–993. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Li Z, Gerrard M, Sargent JD. Specificity of early movie effects on adolescent sexual behavior and alcohol use. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;96:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V. The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens.

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, Gibson JJ, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Carusi CP, Dalton MA. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, Mott LA, Tickle JJ, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Viewing tobacco use in movies: Does it shape attitudes that mediate adolescent smoking? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(3):137–145. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D. Real women have curves: A longitudinal investigation of TV and the body image development of Latina adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(2):132–153. doi: 10.1177/0743558407310712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D, Ward ML, Merriwether A, Caruthers A. Who’s that girl: Television’s role in the body image development of young white and black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28(1):38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00121.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan E. Conservative implications of the irrelevance of racism in contemporary African American cinema. Journal of Black Studies. 2006;37(2):177–192. doi: 10.1177/0021934706292347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Monahan KC. Adolescents’ exposure to sexy media does not hasten the initiation of sexual intercourse. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(2):562. doi: 10.1037/a0020613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburger VC, Jordan AB, Donnerstein E. Health effects of media on children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):756–767. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth KA, Chambers JG, Nassau DH, Rakhra BK, Sargent JD. Exposure of US adolescents to extremely violent movies. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):306–312. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]