Abstract

Illicit rac-MDPV (3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone), manufactured in clandestine labs, has become widely abused for its cocaine-like stimulant properties. It has recently been found as one of the toxic materials in the so-called “bath salts”, producing, among other effects, psychosis and tachycardia in humans when introduced by any of the several routes of administration (e.g., intravenous, oral, etc). The considerable toxicity of this “designer drug” probably resides in one of the enantiomers of the racemate. In order to obtain a sufficient amount of the enantiomers of rac-MDPV to determine their activity, we have improved the known synthesis of rac-MDPV and have found chemical resolving agents, (+)- and (−)-2′-bromotetranilic acid, that gave the MDPV enantiomers in >9896% ee as determined by 1H NMR and chiral HPLC. The absolute stereochemistry of these enantiomers was determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies.

Keywords: 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV); designer drug; bath salts; euphoric stimulant; synthesis; non-chromatographic chiral resolution

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one (3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone, MDPV, “Bath Salts”) It was originally synthesized as a stimulant at Boehringer Ingelheim in 1969,1 and has been is a widely abused because of its potent euphoric stimulant in maneffect.2 It has recently been assignedbeen classified as a Schedule 1 controlled substance, like heroin and LSD. The compound remained obscure until recently when its illicit production and distribution caused a rise in hospitalizations. Human abuse of MDPV and its dependence-producing properties was observed since it became available as a “designer drug” for “recreational” use.3–5 It was found to have considerable toxicity associated with its use as one of the components in bath salts (agitation, psychosis, tachycardia).6 MDPV, itself, was examined and found to have reinforcing effects and was self–administered in rats.7 It MDPV has no approved medical use in the U.S. It is a synthetic derivative of the natural product cathinone, which has itself been misused by individuals presumably seeking its stimulant effects. It has been found that on the molecular level MDPV is more potent than cocaine as a catecholamine-transporter blocker; it was able to block all three transporters, DAT, NET and SERT.2 All of the pharmacological data on MDPV have been obtained with its racemic mixture, since the compound has not, hitherto, been resolved. Chiral resolution of racemates has been known, on occasion, to provide enantiomers with quite different pharmacological effects, and the toxicity of a racemate is sometimes confined to a specific enantiomer. Furthermore, the less toxic enantiomer could eventually prove to be a useful medication, and even a more toxic enantiomer has been eventually found, in some cases, to be medically useful. For these reasons, we sought a method for chiral resolution of MDPV that would provide a sufficient amount of its enantiomers for pharmacological evaluation, and we have determined the stereochemical stability of this relatively simple molecule. In order to find a method for the chiral resolution, we needed to resynthesize the racemic compound. We have now improved the synthesis of MDPV, and we designed a simple and efficient non-chromatographic chiral resolution that provides enantiomers in >96% ee. We also determined that the HCl salt of the enantiomers did not racemize on standing in water for at least 24 hours at room temperature, removing any concern that this might occur during pharmacological testing.

EXPERIMENTAL

General

Melting points were determined on a Thomas-Hoover melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analyses were carried out on Analtech silica gel GHLF 0.25 mm plates using various concentrations of CHCl3 / MeOH containing 10% NH4OH (10% of 28% NH4OH in MeOH solution) or of EtOAc / n-hexane. Visualization was accomplished under UV light or by staining in an iodine chamber. Proton and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (1H and 13C NMR) spectra were recorded in CDCl3 with CHCl3 (δ 7.26), CD3OD with CH3OH (δ 3.31) and DMSO-d6 with DMSO (δ 2.50) as an internal standard, on a Bruker DMX500 wide-bore spectrometer (proton frequency 500.13 MHz, running XWINNMR v3.1) and on a Varian 400 (proton frequency 400 MHz, running VnmrJ version 4.0), with the values given in ppm and J (Hz) assignments of 1H resonance coupling. Mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on a VG 7070E spectrometer or a JEOL SX102a mass spectrometer. Micro-Analysis, Inc., Wilmington, DE, performed elemental analyses, and the results were within ±0.4% of the theoretical values. The optical rotation data were obtained on a PerkinElmer polarimeter model 341. The enantiomeric purity was assessed using an Agilent 1100 series HPLC.

1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)pentan-1-one (2)

Piperonal (benzo[d][1,3]dioxole-5-carbaldehyde, 45.04 g, 0.36 mol) in 60 mL of dry THF was added dropwise to a mechanically stirred solution of 2M butylmagnesium chloride in THF (180 mL, 0.36 M) under argon in a 2 L 3-neck flask, keeping the internal temperature between 5–20 °C with cooling in dry ice-acetone. The mixture was stirred 0.5 h and treated cautiously with 625 mL of saturated NH4Cl in portions. Ether (375 mL) was added and the aqueous layer was separated and re-extracted with ether (200 mL). The combined ethereal solution was washed with 50 mL H2O and evaporated to give 70.8 g of the alcohol intermediate 1 (1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)pentan-1-ol) that still contained some solvent. It showed one spot on TLC in ether-hexane 1:1. The alcohol 1 was added to a well-stirred suspension of 248.0 g of MnO2 in 700 mL of CHCl3 in a 2 L 3-neck flask. The mixture was stirred mechanically and refluxed with a water separator for liquids heavier than water. After 1 h no additional water was produced and TLC showed clean conversion to one spot that appeared at higher Rf than the intermediate alcohol 1. The MnO2 mixture was filtered and washed well with CHCl3. The filtrate and washings were evaporated and the residue was distilled in vacuo to give 1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)pentan-1-one (2, 55.9 g, 90.4% based on 1), bp 125–129 °C / 0.2 – 0.15 mm.

rac-1-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one•HCl (rac-3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone•HCl, rac-MDPV•HCl) (4)

The ketone 2 (20.6 g, 0.1 mol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (200 mL) and treated dropwise at room temperature with a solution of Br2 (16.0 g, 0.1 mol) in 50 mL of CHCl3 to give a very rapid reaction to form 3 (1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-bromopentan-1-one). When the solution showed a negative reaction with moist starch-iodide paper, excess saturated NaHCO3 solution was cautiously added to the stirred solution to give a final aqueous pH of ~ 8. The CHCl3 was separated and evaporated. The residue was dissolved in 200 mL of ether and treated with pyrrolidine (14.22 g, 0.2 mol) and stirred overnight. The basic fraction was extracted into excess 10% citric acid. The citric acid solution was washed with ether (discarded) and made basic to pH 13–14 with 25% NaOH. The basic material was extracted with ether twice and the combined ether extracts was washed with brine and evaporated to a light yellowish-red oil (23.35 4 g). The oil was dissolved in isopropanol (50 mL) and treated with 20 mL of isopropanol containing about 2.7 g of HCl gas. The resulting crystalline material (24.7 g) was heated to solution in 100 mL of 100% EtOH, cooled and diluted with 50 mL of ether. The salt was filtered, washed with 50 mL of 2:1 ethanol-ether and dried in a vacuum oven to give 1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one•HCl (4, 22.2 g (80%) of white crystalline material, mp 247–249 °C (dec, brown before mp; lit.1 mp 229–231 °C). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 12.3 (brs, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.09 (s, 2H), 5.16-5.15 (m, 1H), 3.82-3.74 (m, 2H), 3.67-3.59 (m, 1H), 2.94-2.89 (m, 1H), 2.23-2.08 (m, 4H), 2.04-1.98 (m, 2H), 1.48-1.36 (m, 1H), 1.35-1.26 (m, 1H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 194.4, 153.6, 148.9, 130.6, 125.9, 108.4, 107.7, 102.4, 62.4, 52.7, 49.4, 33.0, 23.9, 23.6, 19.5, 13.9. Anal: Calculated for C16H22ClNO3: C, 61.63, H, 7.11, N, 4.49. Found: C, 61.57; H, 7.11, N, 4.52. The hydrochloride salt was converted to its free base by adding aqueous 20% Na2CO3 to a suspension of the salt in Et2O at room temperature. The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O. The combined organic layer was dried over MgSO4 or Na2SO4. This was filtered, concentrated and dried in vacuo to give the free base as a yellow syrup. The base from this salt was homogenous on silica gel TLC (Et2O: hexane: concd NH4OH; 3 mL: 2 mL: 1 drop). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 7.80 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 6.984 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (s, 2H), 3.77-3.75 (m, 1H), 2.66-2.64 (m, 2H), 2.54-2.53 (m, 2H), 1.90-1.85 (m, 1H), 1.75-1.72 (m, 5H), 1.26-1.18 (m, 2H), 0.86 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ES+): Calcd for C16H22NO3 (M+H)+ 276.1600; found: 276.1606.

Optical Resolution of rac-MDPV•HCl

The hydrochloride salt 4, 6.24 g, 0.02 mol) was partitioned between ether and aqueous Na2CO3 and the ether was evaporated to give the free-base rac-MDPV as a yellow oil. The free-base was dissolved in 54 mL of acetone containing 6.76 8 g (0.021 mol) of (+)-2′-bromotartranilic acid ((+)-BTA) and slowly diluted with 40 mL of ether. It was seeded with a sample of S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5) from a prior run that crystallized from acetone-ether (4:3). The resulting crystals were filtered, washed with 40 mL acetone-ether (4:3) to give the S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA salt 5 (4.58 6 g , 79%). This was dissolved in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and methanol (200 : 3) and evaporated to a foam. Addition of acetone rapidly gave white crystals of pure S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5). Mp 130–132 °C, [α]23D = +57.5 (c 0.89, MeOH). Anal: Calculated for C26H31BrN2O8: C, 53.89; H, 5.39; N, 4.83. Found: C, 53.89; H, 5.14, N, 4.90. X-ray crystallographic analysis of this material showed that the absolute configuration of (−)-MDPV was S (Fig. 1). A sample of this salt from a similar experiment was converted to the free base, [α]23D = −6.5 (c 0.89, CHCl3). The filtrate and washings from the preparation of 5 were combined, evaporated, and treated with aqueous Na2CO3. Extraction with ether and evaporation gave 2.32 g (8.42 mmol) of free-base rac-MDPV (4) enriched with (+)-MDPV (6). These mixed bases were treated with 2.88 9 g (9.0 mmol) of (−)-BTA in 25 mL of acetone to give 2.82 g of crystalline R-(+)-MDPV•(−)-BTA (6). The material was filtered washed with acetone then hexane and dried to give 2.82 g of 6 as a pure materialsolid. Mp 131–133 °C, [α]23D = −57.6 (c 0.98, MeOH). Anal: Calculated for C26H31BrN2O8: C, 53.89; H, 5.39; N, 4.83. Found: C, 53.97; H, 5.08, N, 4.92.

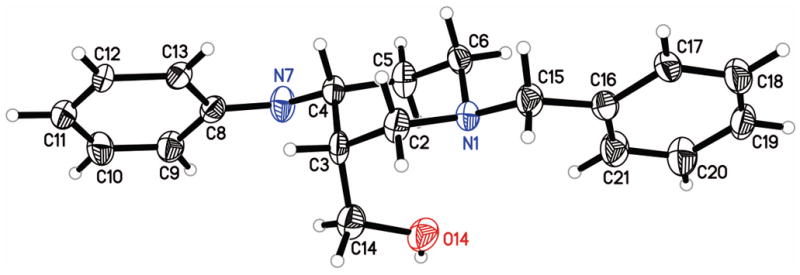

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal data for S-(−)-MDPV

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data on compound S-(−)-MDPV was collected using CuKα radiation and a Bruker Platinum-135 CCD area detector. A 0.109 × 0.064 × 0.016 mm3 crystal was prepared for data collection by coating with high viscosity microscope oil, mounted on a micro-mesh mount (Mitergen, Inc.), and a data set collected at 150°K. The crystal was orthorhombic in space group P 212121, with unit cell dimensions a = 9.3654(2), b = 9.8370(3), and c = 28.0706(7). Data was 95.9% complete to 68.19° θ (~ 0.83 Å) with an average redundancy of 5.49. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least squares on F2 values using the programs found in the SHELXTL suite (Bruker, SHELXTL v6.10, 2000, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI). Corrections were applied for Lorentz, polarization, and absorption effects. Parameters refined included atomic coordinates and anisotropic thermal parameters for all non-hydrogen atoms. Hydrogen atoms on carbons were included using a riding model [coordinate shifts of C applied to H atoms] with C-H distance set at 0.96 Å. Complete information on data collection and refinement is available in the supplemental material. The final anisotropic full matrix least-squares refinement on F2 with 334 variables converged at R1 = 2.90%, for the observed data and wR2 = 8.80% for all data. The absolute configuration was determined from the diffraction data. The absolute configuration as reported by PLATON is C2′ = R, C3′ = R (both from the reference molecule), and C8 = S. Atomic coordinates for S-(−)-MDPV have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (deposition number CCDC 1026174). Copies of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge, CB2 1EZ, UK [fax: +44(0)-1223-336033 or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

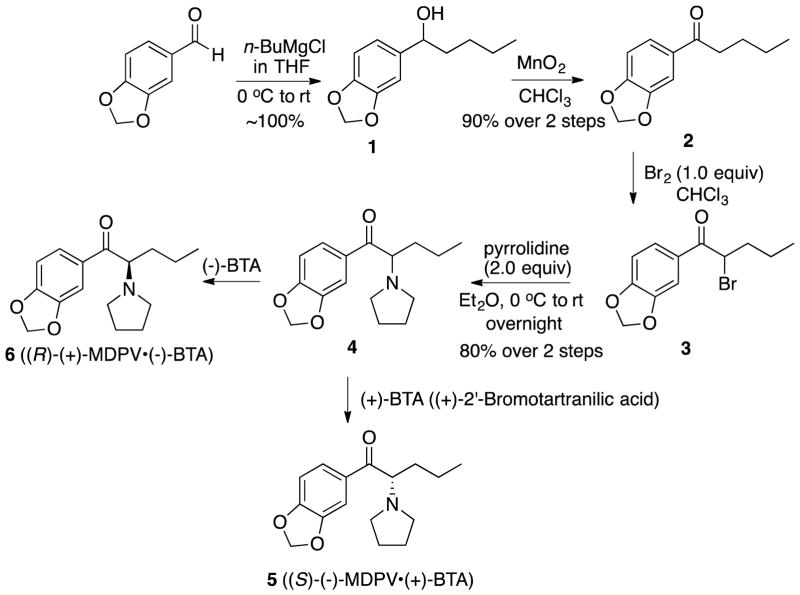

The synthesis of rac-MDPV (4, Scheme 1) followed the general method of Heffe8 as employed by Meltzer.9 The first few steps in the known synthesis of rac-MDPV were modified (Scheme 1). In our hands, this procedure for the preparation of 1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)pentan-1-ol (1, Scheme 1) proved superior to the literature reaction of butylmagnesium chloride with piperonylnitrile followed by hydrolysis. The NMR spectrum of the ketone 2, obtained by oxidation of 1, matched that described by Stille.10

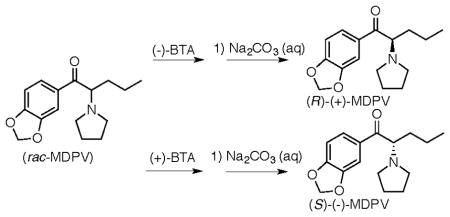

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5) and R-(+)-MDPV•(−)-BTA (6)

Thus, Grignard reaction of piperonal (benzo[d][1,3]dioxole-5-carbaldehyde) with n-butylmagnesium chloride gave the alcohol 1 (1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)pentan-1-ol, Scheme 1). Manganese dioxide oxidation gave ketone 2 (1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)pentan-1-one) in 90% yield for the 2-step procedure. Bromination alpha to the keto moiety in 2 gave 1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-bromopentan-1-one (3), and 3 reacted with pyrrolidine to give the desired rac-MDPV (1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one, 4) in 80% yield for the last two steps in the synthesis.

Chiral resolution was achieved through salt formation of rac-MDPV with (−)- and (+)-2′-bromotartranilic acid (BTA) to give S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5) and R-(+)-MDPV•(−)-BTA (6, Fig. 1). The (+)- and (−)-BTA were prepared using the procedure of Montzka et al.11 via tartaric acids with known absolute configuration. An X-ray crystallographic structure determination of the (−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA salt 5 provided the necessary proof that the configuration at C8 in (−)-MDPV was S (Fig. 1).

Determination of enantiopurity through HPLC and 1H NMR

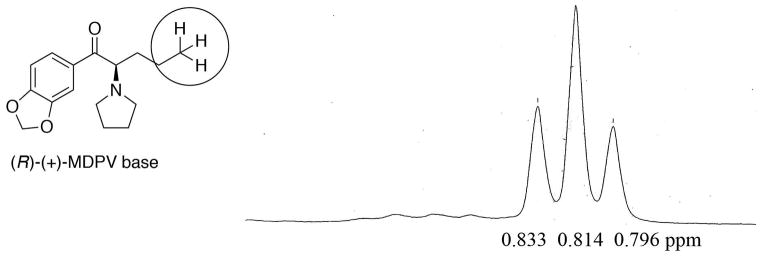

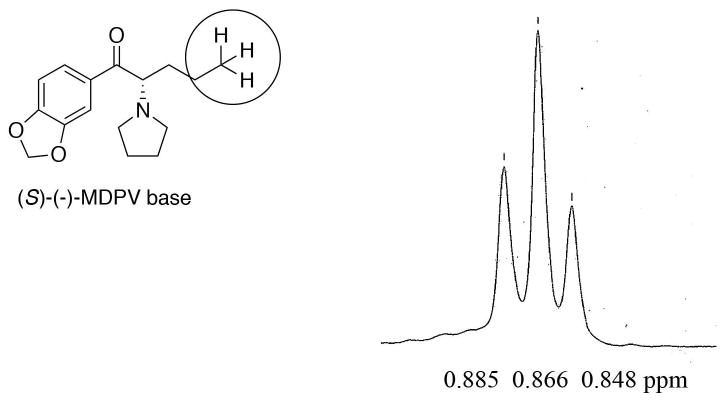

1) 1H NMR

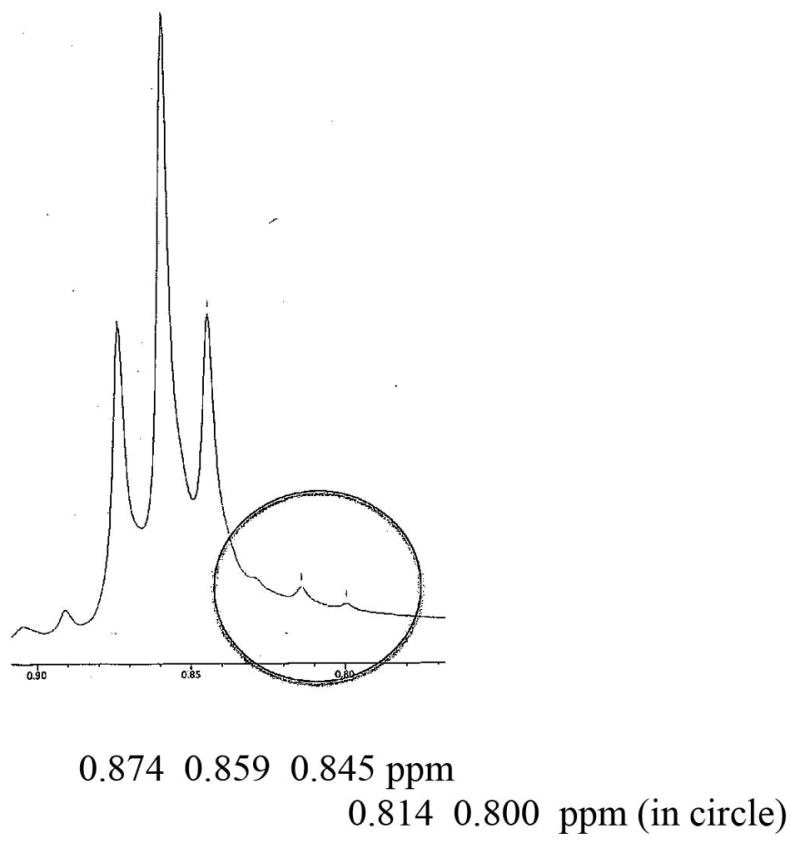

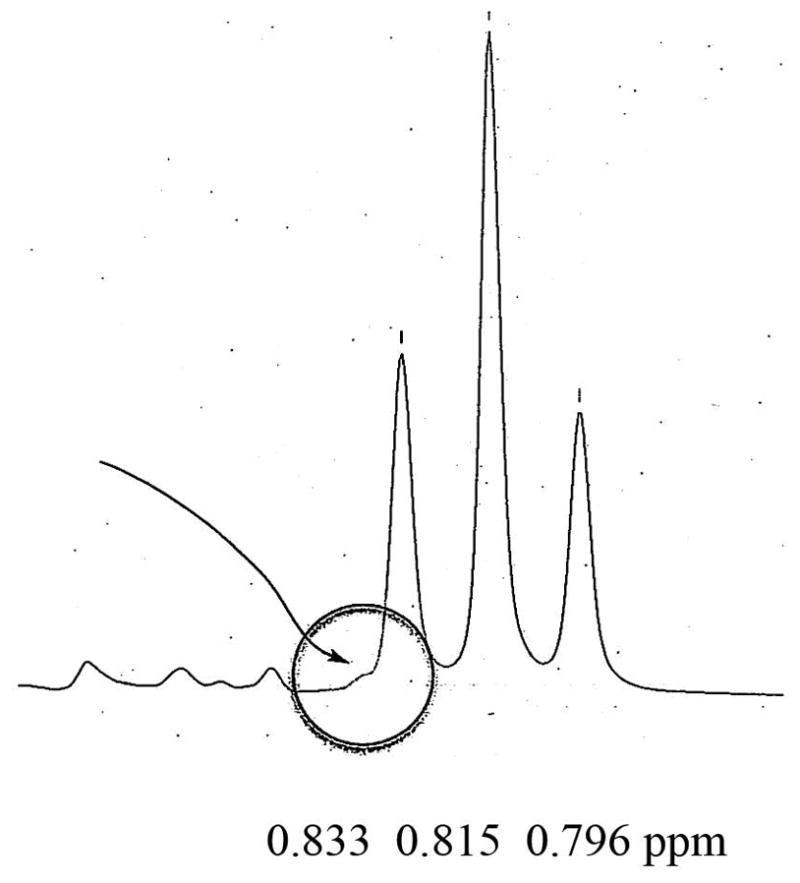

The HCl salts, made for pharmacological evaluation, were found to be stable in aqueous solution (vide infra). They were prepared from the free-bases obtained from 5 and 6 (Scheme 1). The HCl salts of the S-(−)- and R-(+)-MDPV were converted back to their free-bases needed for this study using the usual procedures. The enantiomeric purity of the free bases were assessed by 1H NMR (Fig. 2 and 3) using 25 uL of R-(−)-1-phenyl-2,2,2-trifluoroethanol as a chiral shift reagent in CDCl3 (0.6 mL, concentration: 0.055 mol/L). The free bases showed > 98% ee as seen in Fig. 2 and 3. The presence of the other enantiomer was not detected.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

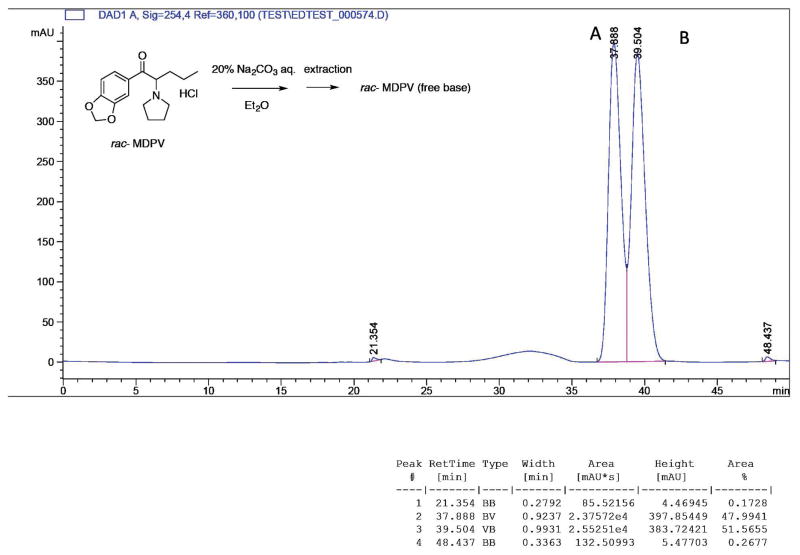

2) HPLC

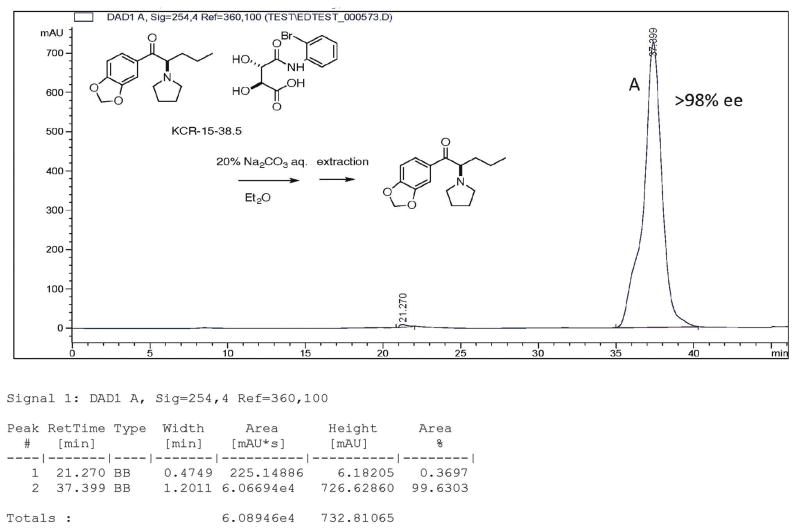

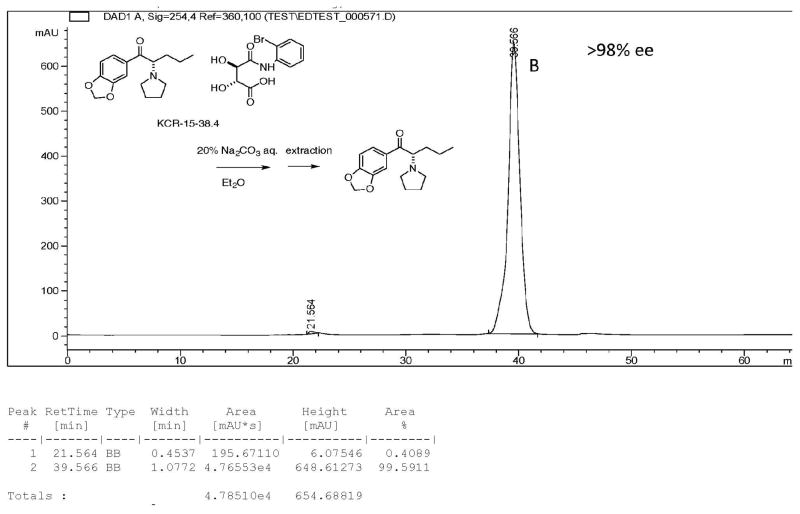

Several chiral columns were examined to determine their suitability for this analysis. None were found that gave satisfactory results; baseline separation could not be obtained on any column. The best chiral column was a Daicel CHIRACEL OJ chiral HPLC column (flow rate; 0.2 mlmL/ min,. eluent: hexane / IPA / n-butylamine (99 / 1 / 0.1)). The retention times of the enantiomers from the free base of rac-MDPV were determined. Enantiomer retention times of A, 37.88 min (R-(+)-MDPV), B, 39.50 min (S-(−)-MDPV) (area: A / B = 48 / 51.6 (1 / 1.08) were observed. Baseline separation was not achieved (Fig. 4), but the peaks could be easily distinguished.

Figure 4.

Each of the separated free-base enantiomers obtained from their 2′-bromotartranilic acid salt was examined separately (Figs. 5 & 6) and it was determined that the purity of A (R-(+)-MDPV in Fig. 4) and B (S-(−)-MDPV in Fig. 4) was >98% ee. The other enantiomer was not seen in Fig. 5 or Fig. 6.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Limits of detection for 1H NMR and chiral HPLC methods

1H NMR method

In order to measure the experimental limits of accuracy of the 1H NMR (using a chiral shift reagent) and the chiral HPLC methods for determining enantiomeric purity, various amounts of the opposite enantiomer was deliberately added to the examined enantiomer in each method. Thus, 0.5% of R-(+)-MDPV•(−)-BTA (11.9 uL of 7.55 mg/mL of 6 in EtOH) was added to a suspension of S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5) in water, and 20% Na2CO3 aq. was added to the mixture. The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O and the combined organic layer was dried over MgSO4 or Na2SO4. This was filtered, concentrated and dried in vacuo to give the free-bases as a yellow syrup. The NMR samples were prepared using CDCl3 (ca. 0.5 – 0.6 mL, concentration of enantiomeric free-bases: ca. 0.05 ~ 0.06 mol/ L) and 25 uL of R-(−)-1-phenyl-2,2,2-trifluoroethanol was added as a chiral shift reagent. Each of the samples were prepared with 0.5%, 1.0% or 2.0% of the other enantiomer.

When 0.5% and 1% of the minor isomer was added, they could be observed only at very high magnification of the spectral area (see supporting information). The minor isomer could easily be observed (see circled area in Fig. 7) when 2% of the R-(+)-isomer was added to S-(−)-MDPV. However, when 2% of the S-(−)-MDPV was added to R-(+)-MDPV, the minor isomer was observed as a broad area (Fig. 8) and was not as apparent as seen in the reverse experiment (Fig. 7). Again, addition of 0.5% and 1% was observable, but only when greatly magnified (see Supporting Information). From these data, the purity of the isomers was estimated to be >96% ee.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

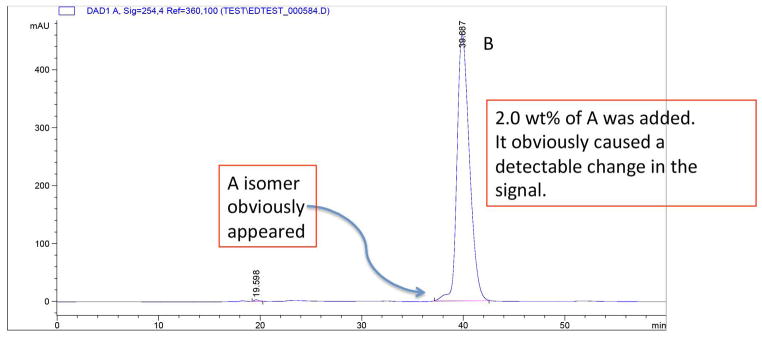

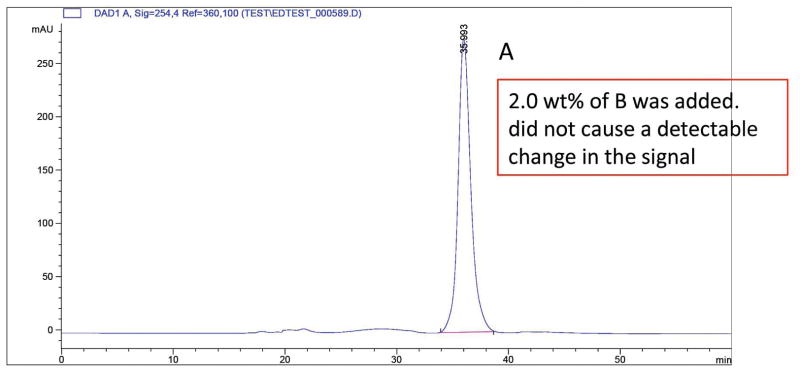

Chiral HPLC method

An analogous procedure to that used in the 1H NMR method was used to examine R-(+)-MDPV•(−)-BTA (6) with 0.5% of of S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5). For HPLC, the free-base syrup was dissolved in EtOH (ca. 1 – 2 mL). Both enantiomers were examined using samples prepared with 1.0% and 2.0% of the other enantiomer. In Fig. 9 the addition of 2.0 wt% of R-(+)-MDPV to S-(−)-MDPV was clearly discernable. That same amount of S-(−)-MDPV added to R-(+)-MDPV could not be seen (Fig. 10). Thus, the HPLC analysis was clearly not as sensitive as the NMR method that could detect 0.5% of the other enantiomer (when the spectra was enlarged greatly), and where a 2% addition was much more easily observed.

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Stereochemical stability of the HCl salt of the enantiomers

The HCl salt of each enantiomer was dissolved in H2O / EtOH and the solution was allowed to stand for 24 h at room temperature. The HCl salt of each enantiomer in these solutions was converted into the free-base and the enantiomeric purity of the S-(−)-MDPV free-base was assessed by chiral HPLC and NMR; the enantiomeric purity of the R-(+)-base was assessed by NMR alone. Since the presence of the other enantiomer was not detected in either of the enantiomers, the free base could be said to have remained > 96% ee. Therefore, the HCl salt appeared to be stereochemically stable under these time and temperature conditions.

CONCLUSION

The synthesis of rac-MDPV was improved and its enantiomers were separated through salt formation with (−)- and (+)-2′-bromotartranilic acid (BTA). The purified S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5) and R-(+)-MDPV•(−)-BTA (6) salts, with their absolute configuration determined through the X-ray crystallographic analysis of S-(−)-MDPV•(+)-BTA (5), were free-based and the S-(−)-MDPV and R-(+)-MDPV were converted to their pharmacologically useful HCl salts. The HCl salt was found to be stable on standing in water for 24 hours. These enantiomers will be pharmacologically evaluated in the future to determine which retains the biological activity found in the racemate and whether the less toxic enantiomer might prove useful for other purposes.

Acknowledgments

The work of the Drug Design and Synthesis Section, NIDA, & NIAAA, was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The X-ray crystallographic work was supported by NIDA through an Interagency Agreement #Y1-DA1101 with the Naval Research Laboratory. We thank Dr. Klaus Gawrisch and Dr. Walter Teague (Laboratory of Membrane Biochemistry and Biophysics, NIAAA), for NMR spectral data. The authors also thank Noel Whittaker, Mass Spectrometry Facility, NIDDK, for mass spectral data.

References

- 1.Koppe H, Ludwig G, Wedel H, Zeile K. 1-(3′4′-Methylenedioxyphenyl-2-pyrrolidinealkanones. 3,478,050. US Patent. 1969 Nov 11;

- 2.Baumann M, Partilla J, Lehner K, Thorndike E, Hoffman A. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive ‘bath salts’ products. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(4):552–562. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, Jansen J. Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of “bath salts” and “legal highs” (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clinical Toxicology. 2011;49(6):499–505. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.German CL, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Bath salts and synthetic cathinones: An emerging designer drug phenomenon. Life Sciences. 2014;97(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz DP, Bhattacharya D, Bhattacharya S, Deruiter J, Clark CR, Suppiramaniam V, Dhanasekaran M. Synthetic cathinones: “A khat and mouse game”. Toxicology Letters. 2014;229(2):349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonowicz JL, Metzger AK, Ramanujam SL. Paranoid psychosis induced by consumption of methylenedioxypyrovalerone: two cases. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2011;33(6):640.e5–640.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Nemirovsky NE, Sewalia K, Grabenauer M, Thomas BF, Marusich JA, Wegner S, Olive MF. Potent rewarding and reinforcing effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Addiction Biology. 2014;19(2):165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heffe W. Die Stevens-umlagerung von allyl-phenacyl-ammoniumsalzen. Helv Chim Acta. 1964;47:1289–1292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meltzer PC, Butler D, Deschamps JR, Madras BK. 1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-pentan-1-one (pyrovalerone) analogues: A promising class of monoamine uptake inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1420–1432. doi: 10.1021/jm050797a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Echavarren AM, Stille JK. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative coupling of aryl triflates with organostannanes. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:1557–1565. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montzka TA, Pindell TL, Matiskella JD. Substituted tartranilic acids. A new series of resolving acids. J Org Chem. 1968;33(10):3993–3995. [Google Scholar]