Abstract

Using structural equation modeling, we examined the relationship of Hispanicism on recent substance use and whether Americanism moderated the effect in a sample of 1,141 Hispanic adolescents. The Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire (BIQ) was used to determine the degree of individual comfort in both Hispanic (Hispanicism) and American (Americanism) cultures. Hispanicism was associated with greater family functioning (β = 0.36, p < .05) and school bonding (β = 0.31, p < .01); Americanism moderated the effect of Hispanicism on substance use (β = 0.92, p < .01). Findings suggest that Hispanic culture was protective against substance use, however those effects differed depending on level of Americanism.

Keywords: Acculturation, Hispanic/Latino/Latina, Culture, Substance Use/Alcohol and Drug Use

Introduction

An estimated 23.9 million Americans, or 9.2% of the population aged 12 years or older, report recent (i.e., past 30 days) illicit substance use (e.g., marijuana/hashish, cocaine, crack, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, and non-medical use of prescription medications); approximately 10% (2.4 million) were adolescent youth, 12–17 years. Among racial/ethnic groups reporting substance use, Hispanic adolescents report problematic use. Hispanic youth have the highest prevalences of lifetime, annual, and 30-day alcohol, cigarette, and licit and illicit drug use, excluding amphetamines, compared to their non-Hispanic white and Black/African American peers (CDC, 2012; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, and Schulenberg, 2013; SAMHSA, 2011). Hispanic youth are also more likely to initiate substance use at an earlier age compared with other ethnic minority youth (CDC, 2012).

Early substance use has been linked to a multitude of socio-behavioral and health difficulties including delinquency, poor school performance, higher proclivity for drug abuse and dependence (Benard, 2004; Bonnie and O’Connell, 2004; Miller, Naimi, Brewer, Jones, 2007; SAMHSA, 2011), involvement with the criminal justice system, and engagement in sexually risky behaviors (CDC, 2011; Kotchick, Shaffer, and Forehand, 2001). These behaviors and social challenges may increase the risk of unplanned teen pregnancies and acquisition of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; Prado, Szapocznik, Maldonado-Molina, Schwartz, and Pantin, 2008). The aforementioned outcomes associated with substance use are adverse health conditions that disproportionately affect Hispanic youth, making the prevention of substance use and other adverse sequelae public health priorities.

Acculturation and Hispanic Substance Use

Some data suggest that identification with Hispanic cultural values (e.g., familismo, respeto) may protect youth from engaging in substance use and other risky behaviors (Castro et al., 2007). Acculturation to American culture, however, may weaken the potential protective effects (Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, and Hayes-Bautista, 2005; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, and Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013) of Hispanic cultural values. For example, some studies have found acculturation to American culture to be associated with increased health and social risks (Berry, 2005; Turner, Lloyd, and Taylor, 2006; Van Wormer and Davis, 2013), greater substance use and dependence (de la Rosa, Holleran, Rugh, and MacMaster, 2005; Epstein, Botvin, and Diaz, 2001; Gil et al., 2000; Martinez, Eddy, & DeGarmo, 2006; Rodriguez et al., 2007; Szapocznik, Prado, Burlew, Williams, and Santisteban, 2007; Warner et al., 2006), poor family functioning, lower school bonding, and associating with deviant peers among Hispanic adolescents (Prado et al., 2008). Conversely, some research has found endorsement of both American and Hispanic cultures to be protective for youth against substance use (Farelly et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2007).

Studies examining the nuances related to the acculturation process are needed given the mixed findings in the literature. Given that acculturation is a multidimensional process that evolves throughout the life course (de la Rosa, Vega, and Radisch, 2000; Lopez-Class, Castro, and Ramirez, 2011), exploring the degree to which individuals identify with both their Hispanic culture and American cultural values and beliefs (Berry, 1997, 2007a) may shed insight into how variations in acculturation impact critical socio-contextual predictors (e.g., family functioning, school bonding, and peer drug use attitudes and norms) of substance use as well as actual substance use (Berry, 1997, 2007a; Valencia and Johnson, 2008).

Acculturation Defined

The process of integrating and adjusting to a new culture involves changes in several life domains such as language and cultural preference (Lopez-Class et al., 2011). A prevailing issue is the degree to which one participates in the new culture (i.e., American) or the culture of origin, or vice versa (LaFromboise, Coleman, and Gerton, 1993). The level to which an individual participates in either culture can be stressful and difficult for families due to the conflict between Hispanic (i.e., emphasis placed on the family and community) and American cultural values (i.e., significance placed on the individual over the family; Prado et al., 2008). As a result, prior work has highlighted the complexity of acculturation with respect to Hispanic and American culture (Lopez-Class et al., 2011).

As such, investigating the complexity involved in the acculturation process is particularly salient when there is a juxtaposition between an individual’s struggle to preserve the culture of origin while participating in the newly adopted culture (Berry, 1997, 2007a). In this vein, more research is needed that elucidates the influence of both cultures together on Hispanic family functioning (Smokowski, Rose, and Bacallao, 2008) and other ecodevelopmental predictors of substance use (e.g., school bonding, and peer drug use attitudes and norms). The consistent and significant associations with said ecodevelopmental factors alongside Hispanic youth substance use (Prado et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2007) highlights this need further.

Acculturation and Ecodevelopmental Predictors of Substance Use

Substance use occurs in developmentally predictable ways during adolescence (Martinez et al., 2006); assessing the mechanisms that contribute to Hispanic adolescent problem behavior requires an understanding of youths’ social and cultural contexts. Specifically, identifying how critical processes within youths’ family, school, and peer environments operate together to impact substance use and how they are are influenced by acculturation may provide important insight for prevention efforts (Bacio et al., 2015). Ecodevelopmental theory, an ecological systems model, provides a multi-dimensional framework that helps explain the influence of family, school, peer, and acculturation mechanisms (Pantin, Schwartz, Sullivan, Coatsworth, and Szapocznik, 2003b).

The micro-system, which is the focus of the current study, consists of the most proximal processes that influence adolescent development. These include the direct interactions youths have with parents, school, and peers, all of which have strong and direct influences on youth behavior (Pantin et al., 2003b; Szapocznik and Coatsworth, 1999; Szapocznik et al., 2007). The family specifically, contains highly influential proximal processes (e.g., parent-adolescent communication, positive parent-adolescent relationships, and parental support) among Hispanic families (Marsiglia, Kulis, Parsai, Villar, & Garcia, 2009; Prado et al., 2009) and is a critical social support system that contributes to the “development and well-being of its members” (Hepworth, Rooney, Dewberry-Rooney, Strom-Gottfried et al., 2013, p. 252). However this support may be weakened during the process of acculturation (de la Rosa, and White, 2001; Gil, Wagner, and Vega 2000; Martinez, 2006; Prado et al., 2008; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez, and Wang, 2007; Szapocznik et al., 2007; Turner et al., 2006). At the same time, some studies suggest that endorsement of both culture of origin and the new culture may have a positive impact on family functioning.

For instance, Farelly and colleagues (2013) examined the influence of adolescent acculturation on family functioning and found that youth endorsing both culture of origin and the new culture had greater family functioning and were less likely to engage in risky sexual behavior. Sullivan et al. (2007) found a similar relationship with youth endorsing both culture of origin and the new culture being significantly associated with higher family functioning and less behavior problems compared to other acculturating youth. From an ecodevelopmental perspective, the level to which youth retain their origin cultural practices and endorse the new culture may not only determine substance use risk and family functioning (Martinez et al., 2006; Schwartz et al., 2007), but predict important relationships in the school and peer contexts such as school bonding and associating with deviant peers (Annuziata, Few, Hogue, and Liddle, 2006; Hawkins, Catalano, and Miller, 1992; Prado et al., 2010).

Research examining the interplay between family, school, and peer factors and their association with Hispanic adolescent substance use found that family functioning was indirectly related to substance use through school functioning and conduct problems (Lopez et al., 2009; Schwartz et al., 2009). Despite the finding that family functioning has a significant impact on school functioning and youth substance use, it is not well understood how school factors combine with acculturation, family, and peer mechanisms to influence substance use (Lopez-Class et al., 2009). Assuming youth become more immersed into American culture through the school and peer contexts, acculturation may have a substantive impact on substance use through these particular processes (Bacio et al., 2015). The current study therefore fills a gap in the literature by examining the impact of acculturation on substance use, with the family, school, and peer contexts together in a mediational framework.

The complex associations between youth’s family, school, and peer systems can either aggravate or mitigate risky behavior, which highlights the critical importance of investigating these processes together (Szapozcnik and Williams, 2000). For example, research has shown that youth who perform poorly in school are more likely to associate with substance-using peers (Swaim, Bates, and Chavez, 1998). Peers, in addition to the family and school environments, create critical ecodevelopmental settings in which youth experience risk as well as develop resiliency (Szapocznik and Coatsworth, 1999). Peers are considered to be one of the most influential proximal factors for youth during adolescence, and are necessary in understanding youth substance use (Koss-Chioino, and Vargas, 1999). Further, peers are a key acculturating mechanism for Hispanic youth (Pantin et al., 2003b): as youth acculturate and gain more autonomy, they look to their peers for acceptance and may adopt American cultural practices in order to gain entry into peer groups. This developmental and cultural dynamic can increase youth susceptibility to anti-social peer pressure and subsequent problem behavior such as substance use (de la Rosa and White, 2001).

Youth micro interactions between parents, school, and peers are pivotal in shaping youth development in positive and negative ways; however, more studies are needed that examine the direct and indirect effects of acculturation on said ecodevelopmental factors. Moreover, the prevention of Hispanic youth substance use requires a contextualized framework that considers factors at the multiple levels in which adolescent development is embedded (Catalano and Hawkins, 1996; Szapocznik and Coatsworth, 1999). In light of the importance of Hispanic ecodevelopment, this study examines whether family functioning, school bonding, and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms mediate the relationship between acculturation and past 90-day substance use.

Current Study and Hypotheses

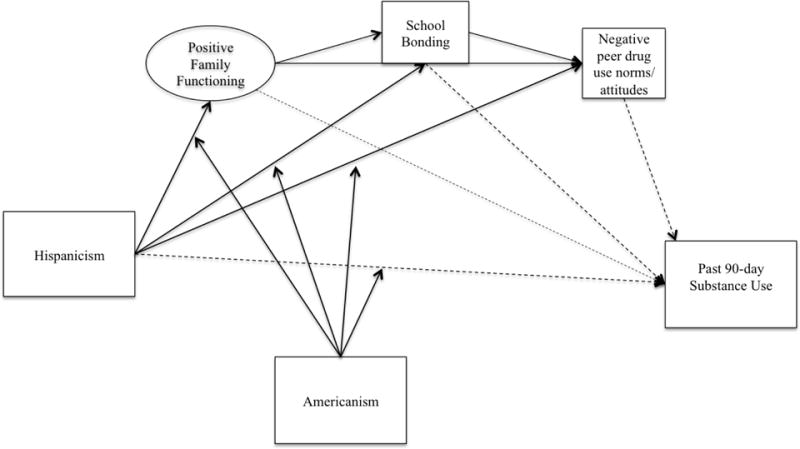

Guided by ecodevleopmental theory, the relationship between Hispanicism (level of endorsement of Hispanic culture/culture of origin) and Americanism (level of endorsement of American culture/new or dominant culture) and socio-contextual predictors of substance use including family functioning, school bonding, and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms (see Figure 1) will be examined, allowing for a multi-layered investigation of mediators of the relationship between acculturation and substance use (Pantin et al., 2003b; Szapocznik and Coatsworth, 1999). Ecodevelopmental theory will be used as the guiding framework to test the direct and indirect effects of Hispanicism on family, school, and peer predictors of substance use as well as the effect of Americanism on Hispanicism and said ecodevelopmental outcomes (Pantin et al., 2003b; Prado et al., 2010; Szapocznik and Coatsworth, 1999).

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Note: Bold paths represent positive direct effects while dotted paths represent negative effects.

Three hypotheses were postulated: Higher levels of Hispanicism will be associated with greater family functioning, school bonding, negative peer drug use attitudes/norms, and lower past 90-day substance use; 2) The relationship between Hispanicism and substance use will be mediated by family functioning, school bonding, and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms; 3) Higher levels of Americanism will lessen the protective effects of Hispanicism on family functioning, school bonding, peer drug use attitudes and norms, and past 90-day substance use.

Methods

Data/Procedures

The current study combined baseline data from three randomized controlled trials (N = 1148) of the Familias Unidas prevention intervention, which uses a parenting approach to reduce HIV and substance use risk behaviors among Hispanic youth (Prado et al., 2012). Two trials tested the efficacy of the Familias Unidas prevention intervention, and one trial tested the effectiveness of the Familias Unidas prevention intervention. Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Miami Social/Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board, the Miami-Dade County School Board’s research committee, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Participants in the first Familias Unidas trial consisted of 242 delinquent youth, 12–17 years of age (Prado et al., 2012). Hispanic adolescents and their parent/primary caregiver were recruited through the Miami-Dade Department of Juvenile Justice Services and the Miami-Dade County Public School system (Prado et al., 2012). In order to be eligible for this particular trial, youth had to have been arrested at least once or have a level-3 behavior problem (e.g., assault, breaking and entering, fighting, possession of drugs or weapons, vandalism, etc.). Participants were randomized into one of two conditions: the Familias Unidas intervention or a community control condition (i.e., standard school prevention curriculum).

Data from the second trial used in the present study consisted of an efficacy study that tested a shortened version of the Familias Unidas intervention. The intervention was condensed from a 12-session program to a 6-session program. Participants included 160 ninth grade Hispanic adolescents and their caregivers. Families were randomized to Familias Unidas or a community practice condition, and were recruited from four high schools in Miami-Dade County. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be of Hispanic origin, attending 9th grade, living with a caregiver willing to participate, and living within the catchment area of the four targeted schools. Participants with prior psychiatric hospitalizations, or with plans to move out of the South Florida area during the study period were excluded.

The third study was an effectiveness trial with 746 Hispanic 8th grade adolescents and their adult primary caregiver. Participants were recruited from 18 randomly selected middle schools in Miami-Dade County that met the study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria. Schools located within the Miami-Dade County school district was the primary criterion at the school level. The criteria at the participant level included: (a) female and male adolescents of Hispanic immigrant origin; (b) adolescents attending 8th grade at baseline, (c) adolescents living with an adult primary caregiver who was willing to participate; and (d) at baseline, families must have been living within the catchment areas of the participating middle schools.

The total sample (across all three studies) included 1,148 Hispanic youth, 627 (54.6%) males and 521 (45.4%) females, with a mean age of 14.24 years (SD = 0.86). The adolescent participation rate across all three studies was 65.76%. More than half (n = 656; 57.01%) of the adolescents were born in the US; the remainder of adolescents involved in the study were immigrants born primarily in Cuba (37.4%), Colombia (10.8%), Honduras (7.5%), Nicaragua (6.9%), Argentina (5.7%), and the Dominican Republic (5.7%). The median household income ranged from $15,000–$19,999.

Measures

Questionnaires across all trials were conducted on computers utilizing the Audio Computer Assisted Interviewer Program (A-CASI; Resnick et al., 1997). A-CASI has been shown to improve youth’s level of honest responses to questions with a sensitive nature (e.g., Metzger et al., 2000). Participants read or listened to items in the language of their choice.

Acculturation

The level of adolescent acculturation was measured using the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire (BIQ), which assesses level of orientation to both American and Hispanic culture. The BIQ was designed specifically for Hispanics, and includes 11 items to assess Americanism and 11 items for Hispanicism (Zane & Mak, 2003). Five-point Likert scale items ranging from (1) ‘Not at all comfortable’ to 5 ‘Very comfortable’ measure comfort or enjoyment of both American and Hispanic cultures. Sample questions include “How much do you enjoy American music?”, and “How comfortable do you feel speaking Spanish at school?”, as well as one’s which indicate desire to utilize the culture’s traditions and customs (e.g., celebrating birthdays the Hispanic way). Cronbach’s alphas for the Americanism and Hispanicism subscales were 0.88 and 0.91, respectively.

Family Functioning

A family functioning latent variable was constructed using five indices: positive parenting; parental involvement; parental monitoring; family communication; and parent-adolescent communication. Each scale was collapsed by summing the items and were treated as indicators for family functioning. A confirmatory factor analysis was then conducted to determine the feasibility of collapsing the five indicators onto a single latent family functioning construct.

Positive parenting (9 items, α = 0.78) and parental involvement (15 items, α = 0.87) were measured using the corresponding subscales from the Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, and Huesmann, 1996). A sample item included, “When you have done something that your parents like or approve of” with response categories ranging from (0) ‘Never’ to (3) ‘Often.’

Parental monitoring was measured using five items from the Parent Relationship with Peer Group Scale (α = 0.82) (Pantin, 1996), which asks parents to indicate the extent to which they supervise their youth and how well they know their youth’s friends. A five-point, Likert scale, ranging from (1) ‘Not at all’ to (5) ‘Extremely well (often),’ were the response options.

Family communication (3 items, α = 0.74) was measured using a subscale from the Family Relations Scale (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, and Zelli, 1997). A sample item included “How well do you personally know your child’s best friends?”

Parent-adolescent communication was assessed using twenty items (α = 0.90) from the Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes and Olson, 1985). A sample question was, “I can discuss my beliefs with my mother/father without feeling restrained or embarrassed” with response categories ranging from (1) ‘Strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘Strongly agree.’

School Bonding

School bonding was assessed using seven items (α = 0.82) from the Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (Goodenow, 2006). Only data from the school bonding subscale, which measures perceptions of belongingness within a school setting, was used for the analysis. Sample questions included, “Most mornings I look forward to going to school,” and “My school is a nice place to be.” Response categories ranged from (1) ‘Not At All True’ to (3) ’Very True.’

Peer Attitudes and Drug Norms

Peer attitudes and drug norms were assessed using three items (α = 0.83) taken from a subscale from the University of Southern California’s Health Behavior Survey (Pentz et al., 1989). Sample questions included, “If your friends found out that you drank sometimes, how do you think they’d feel?’, and “If your friends found out that you smoked cigarettes or used chewing tobacco, snuff or dip, how do you think they’d feel?” Response categories ranged from (1) ‘They would approve’ to (4) ‘They would disapprove and stop being my friends.’

Past 90-day Substance Use

An overall, binary substance use variable, was created using three indicators: past 90-day smoking; past 90-day alcohol use; and past 90-day drug use. Adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and drug use were measured using similar items utilized in the Monitoring the Future study, a national epidemiologic study that assessed the prevalence of alcohol, cigarette, and illicit drug use (Johnston et al., 2013). However, the current study focused on past 90-day substance use whereas Monitoring the Future Study assesses past 30-day use. As a result, a binary variable was created in the current study to demonstrate whether adolescents had smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol, or used an illicit drug in the past 90-days.

Data Analytic Plan

First, using Mplus (version 7; Muthen & Muthen, 2012), we estimated a measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to ascertain the feasibility of collapsing five indicators (i.e,, positive parenting, parental involvement, parental monitoring, family communication, and parent-adolescent communication) onto a single latent family functioning construct. Each scale was collapsed by summing the items and were treated as indicators for family functioning.

Second, we estimated the hypothesized structural equation model (see Figure 1). We used the default estimator, WLSMV, in Mplus to estimate these models; WLSMV is suitable for dealing with categorical outcomes (Flora and Curran, 2004). Weighted least square parameter estimates were obtained by using a diagonal weight matrix, which is good in providing unbiased estimates (Muthen and Muthen, 2012), with standard errors and means. With WLSMV, a continuous latent response variable (y*) underlying the observed dichotomous variable was used. To test the moderation effects of Americanism on the relationship between Hispanicism and past 90 day substance use, family functioning, school bonding and negative peer drug use norms, we first created the interaction term by multiplying the Hispanicism and Americanism scores, and then regressed past 90 day substance use, family functioning, school bonding and negative peer drug use norms on Hispanicism, Americansim, and the interaction term. The hypothesized indirect effects were tested using the asymmetric distribution of products test (MacKinnon et al., 2002); partial mediation is assumed if the confidence interval for this product does not include zero.

Model fit was examined using the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the chi-square (χ2) statistic. The CFI compares the hypothesized model to the null model while the RMSEA tests how well the hypothesized model fits the data (Kline, 2011; Byrne, 2012). The RMSEA estimates the deviation of the specified covariance matrix in the hypothesized model with the covariance matrix in the data. CFI values of 0.95 or greater (Bentler, 1990) and RMSEA values of 0.06 or less (Byrne, 2012; Steiger, 1990) indicate good model. Adolescent’s age, gender, nativity status (U.S. born or foreign born), household income, and cohort membership were controlled for in the model as covariates for outcomes.

Third, the standardized path coefficients were used to assess the size of the direct and indirect effects. Standardized path coefficients that assess the direct effect can be used as correlation coefficient (r) in structural equation modeling. As well, indirect and total effects can be calculated, with standardized estimates corresponding to effect-size estimates (Kline, 2005). As such, effect sizes were interpreted based on small (r = .10), medium (r = .24), and large effects (r = .37).

Results

Past 90-day Substance Use

Three substance use indicators including past 90-day alcohol, smoking, and drug use were combined to create a binary past 90-day substance use variable. In order to provide context regarding problematic substance use among Hispanic youth, national statistics from Monitoring the Future (MTF) were utilized, specifically past 30-day use. It is important to note however that while MTF assesses past 30-day use, the current study examined past 90-day substance use. MTF substance use rates among 8th grade Hispanic youth were used given the average age of the current sample (14.24 years old). Past 90-day alcohol (11.8%) and cigarette smoking (6.5%) among Hispanic youth in the current sample were comparable to past 30-day national rates of use among Hispanics, which are 10% and 6% respectively (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014). Drug use among Hispanics was lower in this sample (8.4%) compared to MTF drug use (e.g., any illicit drug use 17.8%.

Although substance use rates were comparable to national averages, it is important to note that a significant proportion of youth in the current study were foreign born (43%). Foreign born Hispanic youth tend to have lower rates of drug use than US born youth, which this study also found (Almeida, Johnson, Matsumoto, Godette, 2012; Bacio, Lau, & Mays, 2013; Borges et al., 2011; Pena et al., 2008; Prado et al., 2009). Past 90-day alcohol (14.7%), cigarette (7.5%), and drug use (10%) among U.S. born youth were higher compared to alcohol (7.9%), cigarette (5.1%), and drug use (6.3%) among foreign born youth in this sample.

Acculturation

Eleven, 5-point Likert, items assessed Hispanicism and 11, 5-point Likert, items assessed Americanism; the mean scores for Hispanicism and Americanism were 37.50 (SD = 10.73) and 48.07 (SD = 7.62) respectively.

Measurement Model

Family Functioning

Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), all five family functioning subscales loaded significantly onto a single latent construct. The standardized factor loadings for parental involvement (p < 0.001), positive parenting (p < 0.001), parent adolescent communication (p < 0.001), family communication (p < 0.001), and parental monitoring (p < 0.001), were 0.89, 0.74, 0.69, 0.60, and 0.53, respectively. The measurement model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(4) = 6.40, p = 0.17; CFI = 0.999; RMSEA = 0.023.

Structural Equation Model

The hypothesized structural equation model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(64) = 233.3, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.048. We examined the interaction effects first and found there was a significant moderation effect of Americanism on the relationship between Hispanicism and past 90-day substance use (β = 0.85, p < 0.01). Thus, we conducted an analysis leaving out the three nonsignificant moderation effects; this model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(70) = 220.9, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.044.

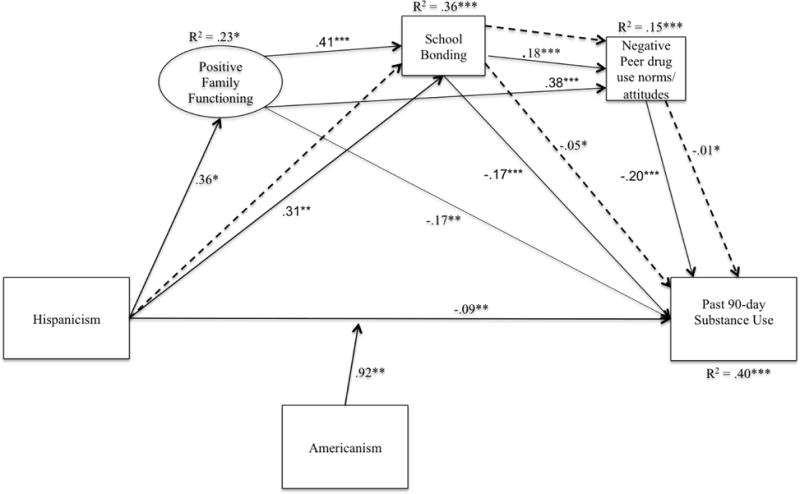

Direct Effects

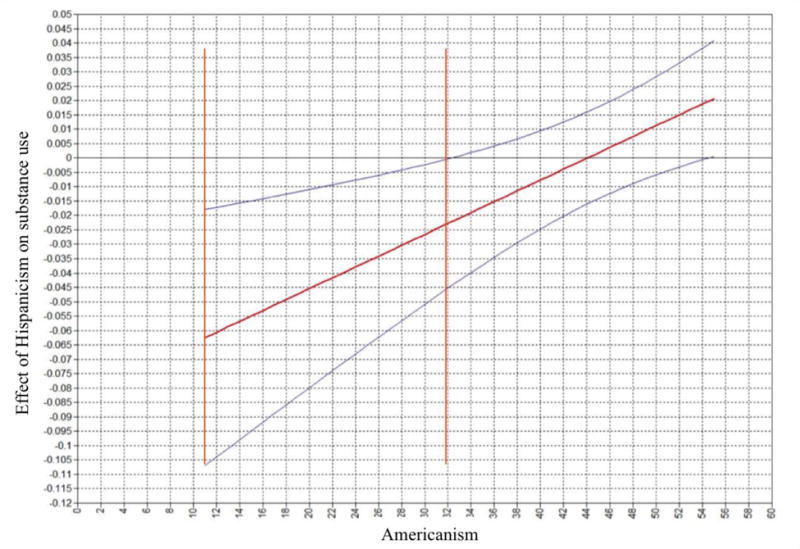

The direct path from Hispanicism to family functioning (β = 0.36, p < 0.05) as well as the direct path from Hispanicism to school bonding were significant (β = 0.31, p < 0.01). The effect size from Hispanicism to family functioning was large while the effect from Hispanicism to school bonding was medium. Americanism significantly moderated the effect of Hispanicism on past 90-day substance use (β = 0.92, p < 0.01; See Figure 2); Specifically, the effect of Hispanism on past 90-day substance use became positive with higher levels of Americanism (See Figure 3). The significant interaction between Hispanicism and Americanism on past 90-day substance use had a large effect.

Figure 2. Direct and Indirect Effects.

Results of the hypothesized model in predicting past 90-day substance use. Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001; Only paths at p<.05 are presented; R2=R squared values for endogenous variables; Bold paths represent direct effects while dotted paths represent mediated effects.

Figure 3. Plotted Interaction Effect.

Plotted interaction effect between Hispanicism and Americanism on past 90-day substance use; Note: The red line represents regression coefficient of Hispanicism on substance use; blue lines represent 95% confidence interval of regression coefficient of Hispanicism; the vertical red lines represent the regions where the effect of Hispanicism was significant.

Family functioning was positively associated with school bonding (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms (β = 0.38, p < 0.001), which were large effects. Family functioning was also negatively associated with past 90-day substance use (β = −0.17, p < .01). School bonding was inversely related to past 90-day substance use (β = −0.17, p < 0.001) and positively related to negative peer drug use attitudes/norms (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). Negative peer drug use attitudes/norms was inversely associated with past 90-day substance use (β = −0.20, p < 0.001). See Figure 2 for a visual depiction of the significant direct effects.

Indirect Effects

There was a statistically significant indirect effect between Hispanicism and past 90-day substance use through school bonding and negative peer drug use attitudes and norms (β = −0.01, p < 0.05; 90% CI = −0.022 to 01); As well, there was a significant indirect effect between Hispanicism and past 90-day substance use through school bonding (β = −.05, p < .05; 90% CI = −0.102 to 01).

Interaction Effect

As mentioned previously, there was a significant interaction effect between Hispanicism and Americanism on past 90-day substance use (Figure 3). The Americanism and Hispanicism interaction was continuous. The results of the interaction indicated that the inverse effect from Hispanicism to past 90-day substance use changed to a positive effect as the level of Americanism increased. Specifically, Hispanicism was associated with higher past 90-day substance use as Americanism increased.

Post-Hoc Analyses

Sample Comparisons

Since multiple youth samples were combined for the current study, we conducted multigroup analyses with the adjudicated and non-adjudicated samples to test for possible differences between samples. First, to test for measurement invariance a multigroup CFA was conducted on the family functioning measurement model comparing the samples. The results supported configural invariance (X2 (8) = 7.311, p = 0.5, RMSEA < 0.001, CFI = 0.999) as well as metric invariance (constrained factor loadings; ΔX2 (4) = 6.72, p = 0.15, RMSEA = 0.017, CFI = 0.999). However, scalar invariance (constraining indicator intercepts) was not supported (ΔX2 (4) = 33.042, p < 0.001). Due to these results, we proceeded with metric invariance. Second, we compared the model with all paths freely estimated and the model with all paths (except the paths from covariates) constrained. Results indicated that constraining these paths did not significantly worsen model fit (ΔX2 (18) = 27.93, p = 0.063). Both the constrained (X2 (126) = 240.94, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.931) and freely estimated model (X2 (108) = 235.58, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.924) demonstrated good fit. Thus, the results showed that there were no differences between these samples.

Discussion

This study examined the direct and indirect effects of acculturation to American culture and retention of culture of origin on substance use through the ecodevelopmental mechanisms of family functioning, school bonding, and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms. Cultural processes, such as acculturation, are central in understanding the etiology of substance use (Alegría, Vallas, and Pumariega, 2010). As well, acculturation is a fundamental process to investigate among Hispanic’s considering they are the fastest growing minority group in the nation and given the make up of the current sample (i.e., many participants were first and second generation immigrants). Due to the negative public health and social ramifications of youth substance use and subsequent HIV risk, understanding the ecodevelopmental mechanisms through which acculturation processes impact substance use may provide critical insight into the nuanced way that acculturation influences youth development. This study fills a current gap in the literature by using mediation analyses to examine the effects of retention of culture of origin and acculturation to American culture on important Hispanic adolescent ecodevelopmental contexts and substance use. This study found Hispanicism (i.e., youth endorsing Hispanic cultural values and beliefs) to be associated with lower substance use, however those effects decreased for youth exhibiting higher levels of Americanism (i.e., oriented to American culture).

It was first hypothesized that higher levels of Hispanicism would be associated with greater family functioning, school bonding, negative peer drug use attitudes and norms, and lower past 90-day substance use. Results indicated that greater Hispanicism was significantly associated with greater family functioning, school bonding, and lower past 90-day substance use. Secondly, it was hypothesized that family functioning, school bonding, and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms would mediate the effects of Hispanicism on substance use and was partially supported; school bonding and peer drug use attitudes and norms mediated the effects of Hispanicism on substance use. The significant direct and indirect effects of Hispanicism on these ecodevelopmental outcomes and substance use are in accordance with previous research (Annuziata et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 1992; Prado et al., 2010).

Despite some research finding retention of culture of origin to be associated with increased substance use (Fosados et al., 2007), the present finding that Hispanicism was associated with lower substance use is consistent with other studies that have found retention of culture of origin to be protective for Hispanic youth (Berry, 2007a; Nguyen and Benet-Martinez, 2013; Rosiers, Schwartz, Zamboanga, Ham, and Huang, 2013; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, and Szapocznik, 2010; Smokowski et al., 2008). As well, this study found that family functioning, school bonding, and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms were mechanisms through which Hispanicism operated in a protective manner. Hispanic cultural values and norms may contribute to decreased anti-social behavior such as substance use (Gamst et al., 2002), specifically as a result of Hispanic culture being more restrictive compared to American culture regarding individual freedom (Castro et al., 2007). Youth that endorse Hispanic culture may be more apt to adhere to Hispanic social norms that stress the importance of family, a critical protective factor, over the individual and may protect youth from substance use. Parents in Hispanic families tend to keep their culture of origin norms, which may mitigate intergenerational conflict with their children (Dinh, Roosa, Tein, and Lopez, 2002). In due course, positive family functioning may provide social support and encouragement to do well in school. The social support of the family may allow youth to have an easier time acclimating to the American school system and may result in a positive bonding experience with their school. This may decrease the likelihood of youth associating with deviant peers and increasing their chances of not using substances.

The result of the continuous interaction between Hispanicism and Americanism indicated that the protective effects of Hispanicism decreased for youth as Americanism increased. Although some research has found acculturation to American culture to be protective against substance use and psychosocial problems (Rosiers et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2007; Smokowski et al., 2008), other studies have found it to be a risk factor for substance use (Epstein, Botvin, Dusenbery, Diaz, and Kerner, 1996; Portes & Rumbaut, 1996; Sullivan et al., 2007; Vega and Gil, 1998). In this study, it was hypothesized that Americanism would moderate the effect of Hispanicism on family functioning, school bonding, peer drug use attitudes/norms, and past 90-day substance use. This hypothesis was partially supported as Americanism moderated the effect of Hispanicism on past 90-day substance use, which supports evidence surrounding the risk effects of acculturation to American culture and the protective effects of Hispanicism. These findings suggest that substance use risk as a matter of acculturation to American culture depends on the degree to which youth are acculturated, demonstrating the varied effects of acculturation on substance use for youth. Youth who highly endorse American cultural interests and values may result in deterioration in Hispanic family norms, values, and attitudes regarding substance use, thereby increasing risk for deleterious risk behavior (Szapocznik et al., 2007).

Lastly, no significant moderation effects were found between Americanism and the hypothesized mediators. Given the high value that Hispanics place on the family, the level of Americanism may not influence levels of family functioning as long as a high level of Hispanicism is present. This falls in line with previous research that states that what is important for youth health outcomes is retaining Hispanic values, not necessarily gaining or losing American values (Schwartz et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., in press). Specific to school bonding, the lack of an interaction effect may suggest that school bonding is protective regardless of level of Americanism since the protective processes offered by retention of Hispanic cultural values often translate into strong school ties. Regarding the peer context, the lack of a significant moderating effect may have resulted from the small and non-significant association between Hispanicism and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms. Although youths’ familial and school relationships have a larger influence on youth during early adolescence, the effect of Americanism on Hispanicism and peer drug use attitudes may become more pronounced as youth age, gain autonomy, and increasingly look towards their peer group for acceptance. Overall, these results demonstrate the complex relationships between acculturation, ecodevelopment, and substance use.

Findings from this study indicate a need for exploring the effects of Hispanicism and Americanism in more depth, given the decreased effect of Hispanicism on substance use for youth who scored high on the Americanism measure. Although the capacity to think and behave consistently within both cultural contexts is thought to counteract the negative effects of acculturation on substance use as well as ecodevelopmental outcomes, findings from this study suggest that acculturation specific to culture of origin and American culture is a more complex and detailed process. Thus, future studies should assess Hispanicism and Americanism more closely and examine whether the direction of effects for both acculturation continuums change depending on where youth are in the acculturation process with respect to both cultures. Examining the interplay between both continuums in more depth may elucidate specific points of intervention for acculturating youth and provide further understanding to how Hispanicism and Americanism operate for adolescent youth navigating both cultures.

Findings from this study were in accordance with previous research that supported associations between positive family functioning, school bonding, associating with pro-social peers, and lower substance use (Annuziata et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 1992; Prado et al., 2010), however more research is needed that explores the effects of acculturation on these outcomes longitudinally. Although this study did not find any significant interaction effects between Hispanicism and Americanism on ecodevelopmental outcomes for youth in this sample, results indicated that school bonding and negative peer drug use attitudes/norms were mechanisms in which Hispanicism operated in a protective manner. Since youth who have poor family functioning or perform badly in school are at increased risk for associating with deviant peers and substance use (Prado et al., 2008; Swaim et al., 1998), illuminating the level at which endorsing Hispanic culture and American culture provides youth with support that is conducive to positive ecodevelopment and lower substance use is critical. Further, adolescent youth experience many changes during this important developmental period and peers are an important mechanism that may expose acculturating youth to pro substance use norms (Fosados et al., 2007; Pantin et al., 2003b). Both the family and school contexts, therefore, may contain critical processes that promote positive functioning and prosocial behavior.

To this team’s knowledge, this is the first study that examined the impact of acculturation, specifically the endorsement of Hispanic and American culture, on substance use, with the family, school, and peer contexts together in a mediational framework. Although some significant medium and large effects were found, other significant paths had small effects and should be interpreted with caution. Although Hispanicism was protective for Hispanic youth, studies are needed that further explore the intricacies associated with Hispanicism and Americanism together as they influence youth ecodevelopment and substance use over time.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the current study. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design, causual relationships cannot be determined. Second, given the unique nature of the South Florida area, generalizations to other Hispanic sub-groups located outside of the region should be made with caution. For example, as a group, Latinos/Hispanics in South Florida may have more economic and/or political power, which may differentially impact acculturation effects. Studies with Hispanic populations in other regions of the U.S. would need to be conducted to determine if our findings can be replicated. Third, given the differences in use among youth for each substance, the interplay between acculturation and ecodevelopmental outcomes may vary. Additionally, due to varying social acceptance of alcohol use versus illicit drug use, acculturation and ecodevelopmental outcomes may differ on these particular substance use outcomes as a result. Further, dichotomizing substance use may not allow researchers to detect the true magnitude of an effect compared to leaving substance use as a continuous outcome. Fourth, effect sizes should be interpreted with caution since many of the significant direct and indirect effects were small. Finally, self-report measures were employed across all three studies, which could potentially bias participant responses. There is the possibility that participants may not provide an honest response, particularly for questions that may cause anxiety or embarrassment; however, this is mitigated by our use of the A-CASI system.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the impact of acculturation and ecodevelopmental factors on Hispanic adolescent substance use. Findings from this study indicated that Hispanicism was associated with greater family functioning and was protective against substance use through school bonding and peer drug use attitudes and norms. As well, the effect of Hispanicism on substance use was moderated by Americanism. This finding, relating specifically the level at which Americanism becomes risky for youth, needs more exploration given the mixed research regarding acculturation to American culture. Studies that elucidate the varied effects and nuances of acculturation can provide insight into how endorsement of ones own culture interacts with the effects of adhering to American cultural norms on risky behavior and can help in the tailoring of prevention/intervention programming targeting Hispanic youth. Given the projected increase in the Hispanic population over the next few decades, understanding the risk and protective effects of acculturation and ecodevelpmental factors on adolescent substance use may help clinicians work more effectively with Hispanic immigrant populations. Clinicians that are aware of the subtleties surrounding acculturation processes specific to Hispanic and American cultures and their associated health risk behaviors may be better able to tap into key protective processes that mitigate these behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants for sharing their feedback as part of this study.

Funding: This research was funded by CDC grant # U01PS000671, NIDA grant # R01 DA025192, and NIDA grant # R01DA025894

Footnotes

Although the lower or upper confidence limit is shown as 0.000, it technically is not zero. MPlus output only prints estimates with three decimals.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alegria M, Vallas M, Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;19(4):759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Matsumoto A, Godette D. Substance use, generation and time in the United States: The modifying role of gender for iimigrant urban adolescents. Social Science Medicine. 2012;75(12):2069–2075. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annuziata D, Few L, Hogue A, Liddle HA. Family functioning and school success in at-risk, inner city adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:100–108. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacio GA, Estrada YE, Huang S, Martinez M, Sardinas K, Prado G. Ecodevelopmental predictors of early initiation of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use among Hispanic adolescents. Journal of School Psychology. 2015;53:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Development. 1985;56:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Benard B. Resiliency: What we have learned. WestEd. San Francisco, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparitive fir indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007a. pp. 543–558. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2005;29:697–712. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997;46(1):5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bacio GA, Lau AS, Mays VM. Drinking initiation and problematic drinking among Latino adolescents: Explanations of the immigrant paradox. Psychology Addictive Behavior. 2013;27(1):14–22. doi: 10.1037/a0029996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie RJ, O’Connell ME. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Washington, DC: The National Academic Press; 2004. retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Breslau J, Oroco R, Tancredi DJ, Anderson H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Medina-Mora ME. A cross national study on Mexico-US migration, substance use and substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;117(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Taylor and Francis Group; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Garfinkle J, Naranjo D, Rollins M, Brook JS, Brook DW. Cultural traditions as “protective factors” among Latino children of illicit drug users. Substance Use and Misuse. 2007;42:621–642. doi: 10.1080/10826080701202247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocialbehavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). (2012) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States 2011. 2012;59 no. SS-4, 1-162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). (2012) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States 2012. 2011;61 no. SS-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa MR, Holleran LK, Rugh D, MacMaster SA. Substance abuse among U.S. Latinos: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa M, Vega R, Radisch MA. The role of acculturation in the substance abuse behavior of African-American and Latino adolescents: Advances, issues, and recommendations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(1):33–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa M, White MS. A review of the role of social support systems in the drug use behavior of Hispanics. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(3):233–240. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh KT, Roosa MW, Tein JY, Lopez VA. The relationship between acculturation and problem behavior proneness in a Hispanic youth sample: A longitudinal mediation model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(3):295–309. doi: 10.1023/a:1015111014775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, Diaz T. Linguistic acculturation associated with higher marijuana and polydrug use among Hispanic adolescents. Substance use and Misuse. 2001;6:477–499. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, Dusenbery L, Diaz T, Kerner J. Validation of an acculturation measure for Hispanic adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1996;79:1075–1079. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farelly C, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Prado G. The role of acculturation and family functioning in predicting HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic delinquent youth. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2013;15:476–483. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9627-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosados R, McClain A, Ritt-Olson A, Sussman S, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. The influence of acculturation on drug and alcohol use in a sample of adolescents. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32(12):2990–3004. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamst G, Dana RH, Der-Karabetian A, Aragon M, Arellano LM, Kramer Effects of Latino acculturation and ethnic identity on mental health outcomes. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2002;24(4):479–504. doi: 10.1177/0.739986302238216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner E, Vega W. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;30(1):79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10(2):115–129. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.10.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth DH, Rooney RH, Dewberry Rooney G, Strom-Gottfried K. Direct social work practice: Theory and skills. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 2012 Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd. The Guliford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koss-Chioino JD, Vargas LA. Working with Latino youth: Culture, development, and context. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology. 2001;21:493–519. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman HL, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and Theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Hayes-Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Class M, Castro FG, Ramirez AG. Conceptions of acculturation: A review and statement of critical issues. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. A longitudinal analysis of Hispanic youth acculturation and cigarette smoking: The roles of gender, culture, family, and discrimination. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2013;15(5):957–968. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Parsai MB, Villar P, Garcia C. Cohesion and conflict: Family influences on adolescent alcohol use in immigrant Latino families. Journal of Ethnicity in Substnace Abuse. 2009;8:400–412. doi: 10.1080/15332640903327526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Eddy JM, DeGarmo DS. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Springer Link; 2006. Preventing substance use among Latino youth Handbook of Drug Abuse Prevention. In Eds. CITY. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Koblin BT, Turner C, Navaline H, Holte S, Seage GR. Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: Utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152:99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119:76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AD, Benet-Martinez V. Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2013;44(1):122–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Preventing substance abuse in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: An eco-developmental, parent-centered approach. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003b;25(4):469–500. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H. Scale of parent relationship with peers. university of Miami; 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Pena JB, Wyman PA, Brown CH, Matthieu MM, Olivares TE, Hartelfooter D, et al. Immigration generation status and its association with suicide attemptes, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the United States. Prevention Science. 2008;9(4):299–310. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0105-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentz MA, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, Flay BR, Hansen WB, Wang EYI, et al. A multicommunity trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse: Effects on drug use prevalance. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261(22):3259–3266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: A portrait. 2nd. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Maldonado-Molina M, Bandiera F, Schwartz SJ, de la Vega P, Hendricks Brown C, Pantin H. An empirical test of ecodevelopmental theory in predicting HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic youth. Health Education and Behavior. 2010;37(1):97–114. doi: 10.1177/1090198109349218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Schwartz SJ, Maldonado-Molina MM, Bandiera FC, de la Rosa M, Pantin H. What accounts for difference in substance use among U.S. born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents?: Results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Szapocznik J, Maldonado-Molina MM, Schwartz SJ, Pantin H. Drug use/abuse prevalence, etiology, prevention, and treatment in Hispanic adolescents: A cultural perspective. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Rosen A, Bacio GA, Jimenez GL, Pantin H, Brown CH, Velazquez M, Villamar J, Freitas D, Tapia MI, McCollister K. The efficacy of familias unidas on drug use and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: main effects and interaction effecs by parental stress and social support. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125:S18–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez RA, Henderson CE, Rowe CL, Burnett KF, Dakof GA, Liddle HA. Acculturation and drug use among dually diagnosed Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6(2):97–113. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosiers SE, Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Ham LS, Huang S. A cultural and social cognitive model of differences in acculturation orientations, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol-related risk behaviors among Hispanic college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(4):319–340. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [SAMHSA] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National registry of evidence based programs and keepin’ it REAL. 2011 Retrieved from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=133.

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Rodriguez L, Wang SC. The structure of cultural identity in an ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults. Basic and Applied Psychology. 2007;29(2):159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Mason CA, Pantin H, Wang W, Brown CH, Campo AE, Szapocznik J. Relationships of social context and idenitity to problem behavior among high-risk Hispanic adolescents. Youth and Society. 2009;40:541–570. doi: 10.1177/0044118x08327506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Huang S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Lorenzo-Blanco E, Villamar JA, Soto DW, Pattarroyo M, Szapocznik J. Substance use and sexual behavior among recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Effects of parent-adolescent differential acculturation and communication. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125S:S26–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation. American Psychologist. 2010;65(4):237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Cordova D, Mason CA, Huang S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers S, Soto DW, Villamar JA, Pattarroyo M, Szapocznik J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation: Links with family functioning andmental health in recent-immigrant Hispanic adolescents. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12341. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose R, Bacallao ML. Acculturation and Latino family processes: How cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Family Relations. 2008;57:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Schwartz SJ, Prado G, Huang S, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. A bidimensional model of acculturation for examining differences in family functioning and behavior problems in Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27(4):405–430. [Google Scholar]

- Swaim RC, Bates SC, Chavez EL. Structural equation model of substance use among Mexican-American and white non-Hispanic school dropouts. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23(3):128–138. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz MD, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins and Interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Williams RA. Brief strategic family therapy: Twenty-five years of interplay among theory, research, and practice in adolescent behavior problems and drug abuse. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;2:117–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1009512719808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew AK, Williams RA, Santisteban DA. Drug abuse in Arican American and Hispanic adolescemts: Culture, development, and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:77–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, Zeli A. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: A measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, Taylor LJ. Stress burden, drug dependence, and the nativity paradox among U.S. Hispanics. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2006;28:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia E, Johnson V. Acculturation among Latino youth and the risk for substance use: Issues of definition and measurement. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38(1):0.37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wormer K, Davis DR. Addiction Treatment: A strengths perspective. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil A. Drug use and ethnicity in early adolescents. Plenum Press; NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, Valdez A, Vega WA, de la Rosa M, Turner RJ, Canino G. Hispanic drug abuse in an evolving cultural context: An agenda for research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:S8–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Mak W. Major approaches in the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy. In: Chun K, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC.: American psychological Association; 2003. pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.