Abstract

Background

Acinetobacter baumannii is a common nosocomial pathogen and strain-typing methods play important roles in hospital outbreak investigations and epidemiologic surveillance. We describe a method for identifying strain-specific peptide markers based on LC-MS/MS profiling of digested peptides. This method classified a test set of A. baumannii isolates collected from a hospital outbreak with discriminatory performance exceeding that of MALDI-TOF-MS.

Methods

Following the construction of a species “pan-peptidome” by in silico translation and digestion of whole genome sequences, a hypothetical set of genome-specific peptides for an isolate was constructed from the disjoint set of the pan-peptidome and the isolate’s calculated peptidome. The genome-specific peptidome guided selection of highly expressed genome-specific peptides from LC-MS/MS experimental profiles as potential peptide markers. The species specificity of each experimentally identified genome-specific peptide was confirmed through a Unipept lowest common ancestor analysis.

Results

Fifteen A. baumannii isolates were analyzed to derive a set of genome- and species-specific peptides that could be used as peptide markers. Identified peptides were cross-checked with protein BLAST against a set of 22 A. baumannii whole genome sequences. A subset of these peptide markers was confirmed to be present in the actual peptide profiles generated by multiple reaction monitoring and targeted LC-MS/MS. The experimentally identified peptides separated these isolates into six strains that agreed with multilocus sequence typing analysis performed on the same isolates.

Conclusions

This approach may be generalizable to other bacterial species, and the peptides may be useful for rapid MS strain tracking of isolates with broad application to infectious disease diagnosis.

Keywords: A. baumannii, peptidomics, strain identification, peptide markers

Introduction

Nosocomial outbreaks caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria carry substantial morbidity and mortality for hospitalized patients in the U.S. (1). Acinetobacter baumannii represents a particularly virulent nosocomial pathogen, and outbreaks of A. baumannii strains resistant to most or all known classes of antibiotics have been responsible for many life-threatening hospital-acquired infections (2). While hospital reservoirs of such bacteria have proven extremely difficult to locate and eliminate, methods that allow identification and tracking of individual strains have proven extremely valuable to infection control efforts. High-resolution strain-tracking techniques may be particularly useful in complex outbreak situations where independent transmission chains involving multiple clones occur against a background of sporadic infection with non-outbreak strains.

The standard method for strain typing of bacterial isolates for many years has been pulsed field gel electrophoresis, a technique that works by analysis of restriction digest patterns using an electrophoresis method capable of separating large fragments of genomic DNA (3). Though this technique has demonstrated its ability to provide relatively robust strain differentiation in certain instances, it has largely been replaced by direct sequencing technologies, which are faster and allow more precise differentiation. The most widely used of these methods is multi-locus sequence analysis, based on the sequencing of a small set of genes that are discriminatory between strains (4). Whole genome mapping and whole genome sequencing are becoming easier and less expensive for clinical, food safety, and public health laboratories, and provide the ultimate level of genomic resolution for clone level tracking of outbreaks (5, 6). However, whole genome sequencing is still not practical for real-time surveillance and strain tracking in many cases of real outbreaks.

Mass spectrometry and proteomics have come to play a much larger role in clinical microbiology over the past decade and the availability of commercial matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) instruments has revolutionized isolate identification in hospital microbiology laboratories (7). These methods work by profiling intact proteins in the m/z range of 2000–20,000, which yields adequate information for identification of a majority of clinical bacteria isolates to the genus and species level by reference to a spectral database. Many attempts have been made to adapt this technology to identification of isolates to the strain level, with some successes (8). However, the proteins profiled by clinical mass spectrometers tend to be highly conserved and limited in number. Consequently, these methods are not optimally suited to strain-level classification of isolates required for tracking of outbreaks.

Mass spectrometry methods based on profiling of peptide fragments may provide a theoretically greater discriminatory capability than methods that sample small intact proteins. Fragmentation may be achieved through a variety of methods, including by laser, collision, and enzymatic digest of proteins (9, 10). In this work, we present an approach to strain-level identification of bacteria based on a rapid tryptic digest protocol and mass spectrometry identification of peptide digest fragments. We demonstrate that this method is capable of classifying a set of A. baumannii isolates into groups concordant with multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) classification.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial isolates

The 22 bacterial isolates used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1. We identified their Oxford MLST and strain naming conventions by searching the pubMLST public databases for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity (pubmlst.org) with the isolate name or GenBank accession number. For mass spectrometry experiments, isolates were aerobically subcultured onto blood agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) for 18–24 h at 35°C with 5% CO2. Isolated colonies from these subcultures were used for MALDI-TOF MS experiments.

MALDI-TOF MS

MALDI-TOF mass spectra were acquired on a Bruker AutoFlex III mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA) as described previously (11). FlexAnalysis software (v3.0 Bruker Daltonics, Inc.) was used for peak detection.

Protein Separation, digestion and identification

Briefly, the retention time of the desired protein was determined by Bruker’s MALDI MS or Q-TOF LC/MS and separated by HPLC as described previously (11). Rapid tryptic digestion was carried out using a CEM Discover microwave system (CEM, Matthews, NC) at 55°C for 15 min with 50W microwave setting. The protein identifications were carried out with either a Waters Synapt G2 HDMS Q-TOF mass spectrometer or a Thermo Orbitrap Elite LC-MS/MS. Detailed information about the protein separation, digestion, and identification methods is provided in the online supplemental file that accompanies this article.

Sample preparation for LC-MS Multiple Reaction Monitoring

The speed-dried FA/ACN lysates were re-suspended in 50mM NH4HCO3 for 15 min rapid digestion by trypsin without protein reduction or alkylation. The digests were diluted with 0.1% FA H2O and spiked with proper amount of labeled peptides for both MRM using ChipCube QQQ and targeted LC-MS/MS using Q-TOF. Detailed information about the sample preparation protocol is provided in the online supplemental file that accompanies this article.

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) LC-MS/MS analysis

The MRM LC-MS assay was developed using an Agilent 6495 ChipCube triple quadruple (QQQ) and ProtID-Chip-43(II) chip. The gradient was run from 5% to 20% B in 7 min with 0.6μl/min flow rate. The total assay time was 11 min. The assay was optimized for collision energy, MS settings, HPLC separation using Skyline 3.1 and Agilent’s MassHunter Optimizer B.07. In the optimized method, the lower limit of detection for most peptides in the samples was approximately 0.5fmol (data not shown). Further information about the MRM LC-MS/MS analysis is provided in the online supplemental file that accompanies this article.

Targeted LC-MS/MS

Targeted LC-MS/MS was run on an Agilent 6540 Q-TOF instrument with AdvanceBio peptide Map column (2.1×150 mm 2.7 μm). 6 peptides (SALVNEYNVDASR, GPLDAAPAYGVK, VTTSGFDGSK, VEENIGQPLSPYAITK, AATMIGLTPQAPS and LFNATAGGYAK) were quantified. The internal control spike was approximately 10 pmol. The collision energy and other MS parameters were optimized before the sample run. The MS/MS acquisition time was set to 400 ms for all ions. Further information about the targeted LC-MS/MS analysis is provided in the online supplemental file that accompanies this article.

Data processing

Both MRM and Targeted LC-MS/MS data by QQQ and Q-TOF were processed by Skyline 3.1.0 software package (MacCoss Lab, University of Washington).

Peptidome creation

A selected set of protein FASTA files corresponding to 15 A. baumannii isolates (online Supplemental Data Table 2 that accompanies this article) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (12). The Digest Database tool in GPMAW 10 software (13) was used to perform a theoretical digestion of each protein into peptides. The resulting collection of all peptides was processed with UltraEdit (IDM computer solutions, Inc., Hamilton, OH) to filter out duplicated peptides and peptides with amino-acid length <6 and >25. The genome-specific peptidomes for strains A–F were then constructed by comparing individual peptidome to a reference pan-peptidome consisting of the combined peptidomes from the other 14 A. baumannii isolates. Thus, the set of peptides encoded by a particular isolate that are not represented in any of the other 14 isolates constitutes the genome-specific peptidome of that isolate.

Experimental identification of genome-specific peptides

The genome-specific peptidome was defined as the set of peptides present in a given genome and absent from the genomes of all other isolates included in the analysis set. We identified the detected genome-specific peptides for a given isolate by comparing detected high-confidence peptides with the genome-specific peptidome using the Microsoft Excel MATCH function.

Lowest common ancestor (LCA) analysis

To address the question of whether any of the experimentally-identified genome-specific peptides are present in organisms other than A. baumannii, a Unipept web tool, pept2lca (Unipept.ugent.be/apidocs/pept2lca) was used to perform LCA analysis. Peptides were defined as species-specific if they were not found to be present in the genomes of any different species by the LCA analysis. The set of identified genome-specific peptides that were found by LCA to be species-specific were selected as potential unique peptide markers. Further information about the LCA analysis is provided in the online supplemental file that accompanies this article.

Results

Strain identification using intact protein analysis with MALDI-TOF

We initially sought to develop a method to distinguish strain differences in 22 A. baumannii complex isolates by MALDI-MS. These 22 isolates were selected from a larger set of isolates of A. baumannii complex collected in the NIH Clinical Center during an outbreak (6, 14). To ensure the correct strain classification and identification, only the isolates with sequenced genomes were selected for inclusion in this analysis (Supplemental Data Table 1). Isolates 11, 25, and 26 were not included in experimental MALDI-MS or LC-MS analysis as archived isolate stocks were not available at the time of this study. However, it was possible to include these three isolates in the theoretical peptidome analysis since whole genome sequencing was available.

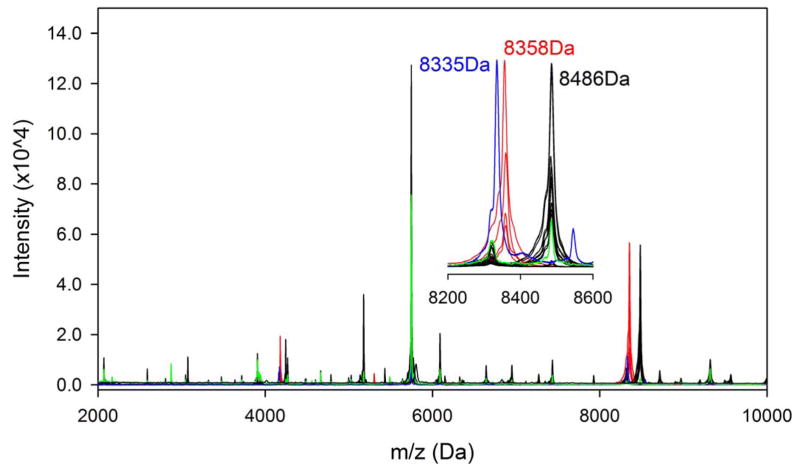

Our initial analysis queried whether protein peaks present in MALDI-TOF MS spectra could be used to distinguish among the 6 strain assignments within our isolate set, based both on previously published PFGE data and Oxford MLST group classification (6, 14). Only a single distinguishing feature was found in the MALDI-TOF MS profiles (Figure 1). Isolates in the strain D group appeared to demonstrate a peak that was shifted from ~8486 Da to ~8358 Da relative to strains A, B, C or E while isolate F showed a similar but different shift from ~8486 Da to ~8335 Da. High mass accurate Q-TOF LC-MS measured the masses of these three peaks to be 8487.57 Da, 8359.36 Da, and 8336.60 Da. Genomic analysis and protein sequencing by top-down proteomics revealed that the peak represented the same protein in all 6 strains (gi|475927070|gb|EMT96064.1 in strain D, ACIN5111_1550 in strain F and gi|342232168|gb|EGT96951.1 in strain B). The 128 Da shift in the strain D isolate is due to a glutamine deletion (deltaQ20) and strain F contains the deltaQ20 and a histidine to asparagine mutation (H29N). (Supplemental Data Figure 1). This highly expressed 72–73 residue protein contains almost 50% glutamine in tracks of up to six glutamines and its function is unknown. Thus, mutations in this single protein could distinguish three strain groups: D, F, and A–B–C–E.

Figure 1.

MALDI-MS spectra for 4 strain D (red) isolates, a group of 15 strain A, B and C (black) isolates, 1 strain E (green) isolate and 1 strain F (blue) isolate. In the inserted graph, the scale of peak intensity of strain F (blue) was rescaled 10× from original data to show the peak shift in strain E.

Development of reference peptidome for A. baumannii genome-specific peptides

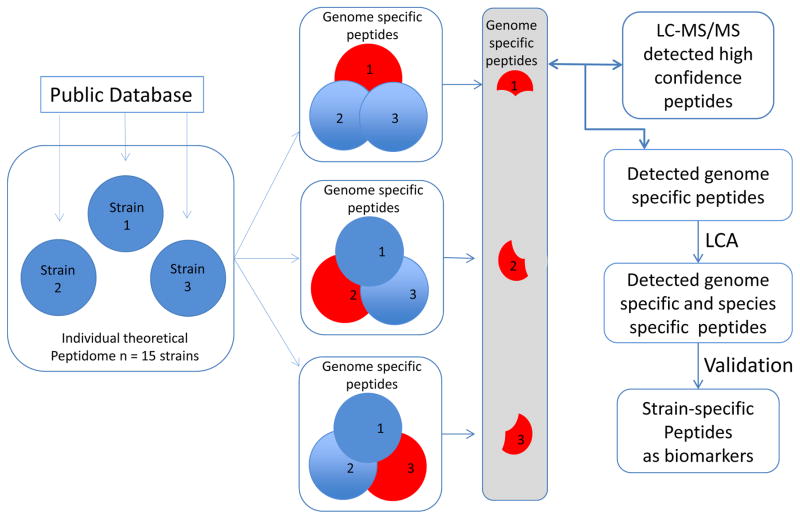

Given the inability of intact protein profiling with MALDI-TOF MS to separate all isolates into strain groups, we sought to develop a higher resolution strain typing method based on tryptic protein digests. To do this, we first developed an analytic method that could be used to identify theoretically discriminating tryptic peptide fragments. The approach began with a series of in silico tryptic digest proteome sets (pan-proteome, genome-specific proteome, species-specific proteome, and strain-specific proteome) for the isolates of interest (Figure 2). LC-MS/MS was then used for experimental identification of predicted peptide markers.

Figure 2.

Peptidome analysis to detect genome-specific and species-specific peptides using A. baumannii as an example. High confidence peptides detected experimentally by LC-MS/MS were compared with genome specific peptides to identify a set of detected genome-specific peptides. Lowest common ancestor (LCA) was then used to search species-specific peptides. MRM or targeted LC-MS/MS was used to validate the peptide marker experimentally.

To construct a pan-peptidome for a test set of A. baumannii isolates, 15 isolates for which whole genome sequences were available were combined to create a FASTA database (Supplemental Data Table 2). These 15 isolates included strains A–F as well as an additional 9 A. baumannii isolates that were chosen to be representatives of the A. baumannii dendrogram of all A. baumannii genome assemblies present in the NCBI database. These 15 strains had 40–86% peptidome similarity to one another based on tryptic peptidome analysis (Unipept) (Supplemental Data Figure 2). Pairwise similarities were computed as a fraction of the size of the intersection over the size of the union of both peptidomes (15). Peptidome similarities between a representative strain D (ST231) isolate and representative members of strain A (ST281), strain B (ST348), or strain C (ST353) were about 60%. The peptidome similarity among representative members of strains A, B and C (ST281, ST348, and ST353 respectively) was about 80%. On the basis of this degree of difference, we postulated that it should be theoretically possible to identify genome-specific peptides to distinguish these representative A. baumannii MLST types.

Rapid tryptic digestion of intact bacteria

Traditional tryptic digestion methods involve reduction, alkylation and lengthy digestion aiming for complete coverage. Given the very large number of peptides produced in a typical digestion, we hypothesized that strain-specific peptides could be detected with a simplified digestion scheme. We developed a rapid protocol that involved a 15 min digest of intact bacterial cells at 55°C without cell lysis, protein denaturation, disulfide reduction or alkylation. This simplified digestion scheme was designed to minimize time and optimize efficiency at the potential expense of generating a complete disulfate-reduced peptide fragment library (online Supplemental file). It was found to be comparable in terms of the numbers of peptides and proteins identified with either a conventional 4 h digest at 37°C that included cell denaturation, disulfide reduction, alkylation and desalting, performed in parallel (Supplemental Data Table 3) or 55°C for 15 min in either a water bath or in a CEM Discover microwave system (Supplemental Data Table 4).

LC-MS/MS detection of A. baumannii strain-specific peptides

Representative isolates from A. baumannii strains A–F underwent rapid 15 min tryptic digestion at 55°C. A portion of the digests was analyzed by LC-MS/MS for total protein identification and among the analyzed isolates, 753 to 1457 proteins and 2546 to 6482 peptides were detected (Supplemental Data Table 5). In comparison, the theoretically possible genome-specific peptides among each member (based on comparison of each isolate’s genome to the pan-peptidome constructed from the other 14 isolates in the set) were 629–6554 (Supplemental Data Table 5). The number of theoretical genome-specific peptides was dependent on how the pan-peptidome was constructed, and including a greater number of strains was expected to increase generality. For the purpose of this proof-of-concept demonstration, we chose 15 isolates representing a broad range of A. baumannii strains for the pan-peptidome construction. An analysis of whether each peptide was specific to Acinetobacter baumannii (i.e. not present in the genome of a different species) was performed using tryptic peptide analysis to define its LCA based on the UniProtKB records where the complete taxonomic lineage derived from the NCBI taxonomy of the peptide can be found (16). The number of theoretically possible species-specific peptides based on LCA analysis ranged from 405 to 3220 (Supplemental Data Table 5). Other peptides were found to be specific to Acinetobacter (genus), gammaproteobacteria (class), or proteobacteria (phylum).

We compared the peptidome for representative isolates from A. baumannii strains A–F with the actual detected peptide list from LC-MS/MS data. High confidence peptides were defined as those with FDR < 0.01 during the target-decoy protein search. Of these high confidence peptides, 4 to 129 peptides were found to be genome-specific and a mean of 14 (min 4, max 72) were found to be also species-specific by LCA analysis. While these represent only a small fraction of the available genome-specific and species-specific peptides, they are abundant peptides that may be suitable for MRM development. The relative expression levels (Supplemental Data Table 6) were calculated from LC-MS data by extracting the precursor ion and integrating the LC-MS chromatography peak. The peptides with higher expression levels were high abundance peptides that could be easily detected and were chosen as potential peptide markers for further validation and MRM assay development.

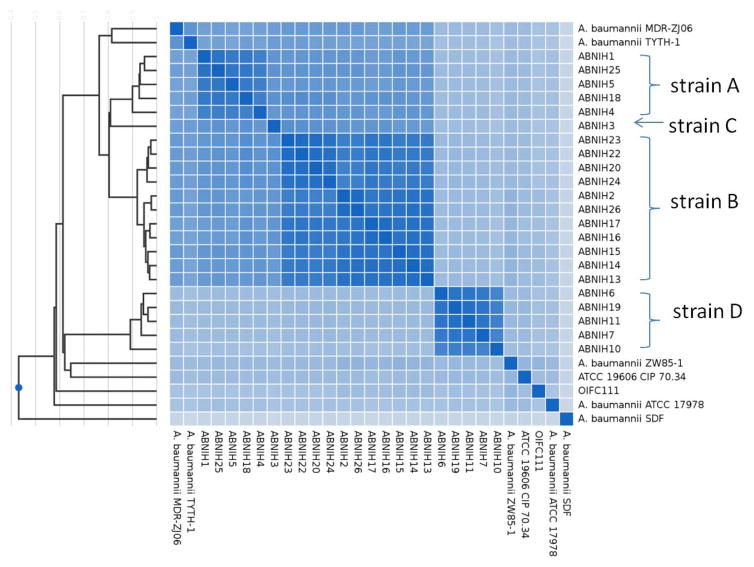

Table 1 lists the chosen peptide sequences and precursor ions that were easily detected by LC-MS/MS and both genome-specific and species-specific. The top-choice peptide markers for the analyzed isolates representing strains A–C were GPLDAAPAYGVK, VEENIGQPLSPYAITK and LFNATAGGYAK respectively. To validate these peptides as strain-specific, we compared the peptidome similarities of 22 NIH A. baumannii isolates for which whole genome sequencing data were available using Unipept peptidome analysis (Figure 3, Table 2). Peptidome similarities clearly separate these 22 isolates into 4 groups corresponding to strains A, B, C, and D.

Table 1.

Representative peptides detected from isolates with Strain A, B, C, D, E and F. Peptide specificity was checked by Unipept with lowest common ancestor (LCA) as A. baumannii. The ion charge, precursor ion mass, transitions and relative abundance are listed in Supplemental Data Table 6.

| Strain | Peptide | Precursor (Da) |

|---|---|---|

| A | GPLDAAPAYGVK | 579.81134 |

| VTTSGFDGSK | 499.74353 | |

| B | LGIDTEQVLK | 558.319 |

| VEENIGQPLSPYAITK | 879.96729 | |

| AATMIGLTPQAPSK | 693.37653 | |

| C | LFNATAGGYAK | 556.7904 |

| EALGGYLPTR | 538.7904 | |

| SDGGMTIVVPEESR | 738.85362 | |

| D | LGEPQDIANAVR | 641.84117 |

| NEAVSDQAPAVR | 628.81515 | |

| GDVDGLAAGAEYK | 633.30408 | |

| GLTAQEIYR | 525.78257 | |

| EGLSTFLNK | 504.77168 | |

| NVGGNNYENGTILDPK | 852.91305 | |

| E | AEAAPAPQAVAPK | 610.83536 |

| IGQDLNLR | 464.76419 | |

| AGGVTSQAVVMDGGYTAQ | 856.40147 | |

| F | DGALPADAPMTQAQ | 693.32196 |

| YLNEVVLDR | 560.80351 | |

| ILSSTALK | 416.76058 | |

| LALPTAVQK | 470.79496 |

Figure 3.

Peptidome similarities of 22 NIH A. baumannii isolates and 7 other randomly selected strains using their genome data. The graph was generated by Peptidome analysis by Unipept. Strain A, B, C and D were clearly separated theoretically by comparing their tryptic peptidome differences.

Table 2.

Strain identification of ABNIH isolates

| Theoretical | Experimental | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Peptidome | MLST (Oxford) | 8360Da | Q-TOF | QQQ |

| ABNIH01 | A | ST281 | No | A | A |

| ABNIH02 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH03 | C | ST353 | No | C | C |

| ABNIH04 | A | n/a | No | A | A |

| ABNIH05 | A | ST281 | No | A | A |

| ABNIH06 | D | ST231 | Yes (D)a | ||

| ABNIH07 | D | ST231 | Yes (D) a | ||

| ABNIH10 | D | ST231 | Yes (D) a | ||

| ABNIH11 | D | ST231 | n/ab | n/ab | n/ab |

| ABNIH13 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH14 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH15 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH16 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH17 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH18 | A | ST281 | No | A | A |

| ABNIH19 | D | ST231 | Yes (D) a | ||

| ABNIH20 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH22 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH23 | B | ST238 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH24 | B | ST348 | No | B | B |

| ABNIH25 | D | ST281 | n/ab | n/ab | n/ab |

| ABNIH26 | B | ST348 | n/ab | n/ab | n/ab |

the 8360Da peak was detected and assigned to strain D

isolates were not available

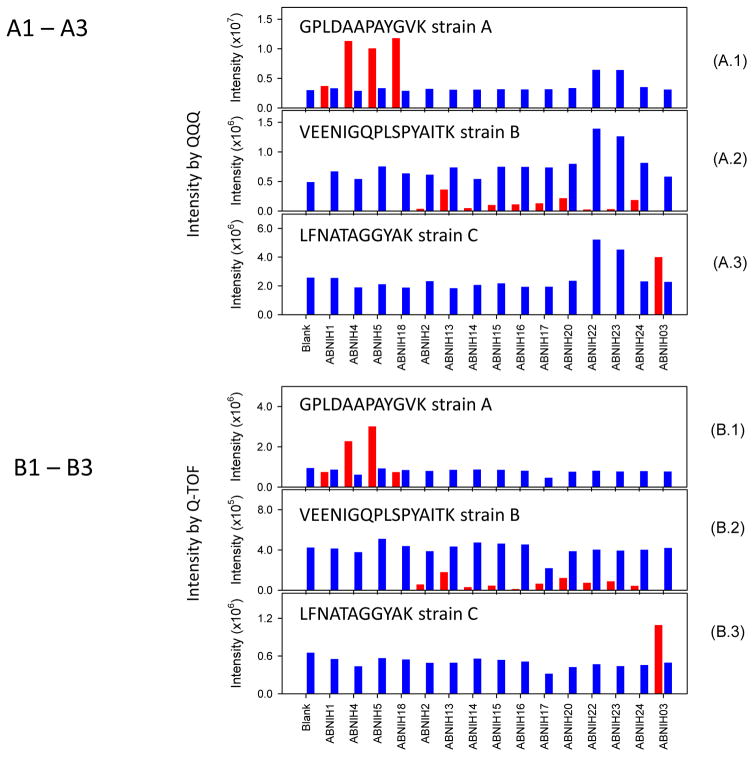

To validate the peptide markers and concept of the method, we developed MRM assays (Agilent’s ChipCube QQQ 6495) and a targeted LC-MS/MS method (Agilent’s Q-TOF 6540) to confirm the peptide markers associated with the 15 A. baumannii isolates. In both assays, isotope labeled target peptides were used to optimize the assays. In addition to the peptides listed in Table 1 for strains A–C, isotopically labeled peptide SALVNEYNVDASR was also added as a positive control. SALVNEYNVDASR is a highly abundant and highly specific A. baumannii peptide present in all 15 A. baumannii isolates used in the strain-specific validation and in strain E and F (data not shown). The retention time and relative intensity of this peptide during the sample run were used to monitor the sample preparation, instrument status and HPLC column performance. Figure 4 shows the relative intensity of three detected peptides using Q-TOF and QQQ. GPLDAAPAYGVK, VEENIGQPLSPYAITK and LFNATAGGYAK were found to be the best peptide markers among other peptides on Table 1 for strains A–C, respectively. The peptide retention time (peptide RT) and the ratio to standard for these three peptide markers are summarized in Supplemental Data Tables 7 and 8. Representative chromatograms for these three peptides are shown in Supplemental Data Figure 3 and 4. The strain classification by these three peptide markers matched well with the peptidome analysis and Oxford MLST. A workflow for A. baumannii species identification based on MALDI and LC/MS is summarized in Supplemental Data Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Relative integrated peak intensities of three peptide markers measured by MRM LC-MS (Figures 4A.1 to 3) or targeted LC-MS/MS (Figure 4B.1 to 3) from 15 ABNIH isolates (strains A, B and C) shown on the X-axis. The blue bars are the integrated peak intensities of labeled peptides or standards and the red bars are the detected peptides from ABNIH isolates.

Discussion

In this work, we present a proof-of-concept approach for identifying bacterial strain-specific mass spectrometry peptide markers based on LC-MS/MS profiling of digested peptides and peptidomic analysis. This method was able to classify a test set of A. baumannii isolates collected from a previously studied hospital outbreak into groups corresponding to MLST types with discriminatory performance substantially exceeding that of MALDI-TOF MS. Our method combines the generation of theoretical peptidomes (i.e. pan-peptidome, genome-specific peptidomes) from the in silico translation and digestion of whole genome sequences with bioinformatic confirmation of the peptide strain specificity, followed by the detection of these peptides experimentally. We show that LC-MS/MS protein peptides can be acquired from a rapid 15 min digestion at 55°C of either whole bacterial isolates or their FA/ACN lysates used in MALDI.

The species specificity of each of the calculated genome-specific peptides detected in the LC-MS/MS spectra was verified using LCA analysis (16). This step was necessary to exclude the possibility that the genome-specific peptides identified in the initial step were present in the genomes of more distantly-related species that were not represented in the pan-peptidome. For instance, a given peptide may be present in one sequenced member A. baumannii, but also present in some E. coli. In such a case, the peptide would have appeared to be genome-specific in the initial analysis but would not to be species-specific in the LCA analysis. The set of genome-specific peptides experimentally found in LC-MS/MS profiles and verified as species-specific through LCA analysis were then validated as potential strain-specific peptide markers using protein BLAST against a set of 22 A. baumannii genomes. It should be emphasized that the specificity of the peptides identified by this method is dependent on the number of genomes used to construct the pan-peptidome, and specificity is expected to increase as more genomes are added for a particular case. In the case of this proof-of-principle study, we limited our pan-peptidome test set to 15 isolates. Greater initial specificity might be expected when working with a larger isolate set. While this approach does not provide an absolute global assessment of all peptide fragments, it provides methods to detect abundant proteins and peptides that are specific to different bacterial strains. The great diversity of peptides available to this approach allows one to focus selectively on high abundance peptides that make the most robust markers for strain identification.

Several potential pitfalls must be addressed in the future development of this method towards a clinical application. The first relates to the quality and availability of strain-specific genomes. Second, false positives (i.e. type I errors) may occur from incorrect attribution of a peptide marker to a strain or species because of sequence errors and non-genomic factors such as noise and interference from matrix (17). Potential interfering substances may be present which may only become apparent during MRM optimization with visual inspection of the chromatogram. Third, relying on only one or two peptide markers may be limiting because unrelated peptides (e.g. derived from variable tryptic digestion, missed cleavages) could give rise to a confounding false peptide marker signal. The use of multiple peptide markers for a specific strain should diminish the influence of any single (false) peptide marker. The expansion of the marker pool to include larger strain and isolate pools will enhance the specificity of the approach. Fourth, the existence of non-clonal and mixed cultures may limit the sensitivity of this approach in detecting a set of markers in a primary clinical specimen, though we would not expect this to be substantially problematic for the single-colony (clonal) subcultures that are routinely used for bacterial identification in clinical microbiology laboratories.

To improve the fidelity of this approach, further work should be directed to include more strain types as well as MLSTs derived from different geographic locations. Rapid digestion without reduction and alkylation will bias the results towards high abundance proteins that are less likely to vary with growth conditions. However, features of growth conditions such as environmental stress and nutrient availability may affect the A. baumannii proteome and induce proteins associated with signaling, virulence, resistance factors and stress responses (18, 19). These lower abundance proteins may be important when assessing the rapid identification of drug resistant strains (19). Their detection with a rapid tryptic digestion protocol remain to be determined. Challenges with MRM include the sensitivity and range of protein concentration reached without enrichment methods. Analytes with precursor and fragment ion masses similar to that of a target peptide can result in contaminated MRM transitions, which can result in a type I error or inaccurate quantification (17). In contrast to the discovery approach of strain-specific peptide markers described in the current study, others have developed a targeted approach based on selected reaction monitoring of known peptides associated with S.aureus species, strain, and antibiotic resistance (20).

We anticipate that our approach may be applicable to many other clinical isolates allowing a rapid means of identifying specific bacterial strains based on unique peptide markers, with broad utility in both infectious disease diagnostics and epidemiologic tracking of outbreaks (21).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Clinical Center, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health and Human Services or the National Institutes of Health.

We acknowledge the assistance of the Proteomics and Metabolomics Shared Resource of Duke University School of Medicine in the provision of protein identification services. We also thank Col. Emil P. Lesho, Dr. Patrick T. McGann and the Multidrug-resistant organism Repository and Surveillance Network (MRSN) team at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD (WRAIR) for providing A. baumannii AC OIFC111 (strain F) for this work.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: HW, SD, JPD, AS.

Performed the experiments: HW, SD, YC, ES, MMS, AR, MT.

Analyzed the data: HW, SD, AS, JPD, YC, ES, MMS, AR

Manuscript writing and editing: HW, SD, JPD, AS

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, editor. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. 2013:1–114. http://wwwcdcgov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508pdf.

- 2.Kaye KS, Pogue JM. Infections caused by resistant gram-negative bacteria: Epidemiology and management. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:949–62. doi: 10.1002/phar.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz DC, Cantor CR. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized dnas by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell. 1984;37:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaeser SP, Kampfer P. Multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) in prokaryotic taxonomy. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015;38:237–45. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JM. Whole-genome mapping: A new paradigm in strain-typing technology. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1066–70. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00093-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Montero CI, Stock F, Mijares L, Program NCS, et al. Genome-wide recombination drives diversification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13758–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel R. Maldi-tof ms for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Clin Chem. 2015;61:100–11. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.221770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinali S, van Belkum A, Goering RV, Girard V, Welker M, Van Nuenen M, et al. Microbial typing by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry: Do we need guidance for data interpretation? J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:760–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01635-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asakawa D, Calligaris D, Zimmerman TA, De Pauw E. In-source decay during matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization combined with the collisional process in an FTICR mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2013;85:7809–17. doi: 10.1021/ac401234q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Switzar L, Giera M, Niessen WM. Protein digestion: An overview of the available techniques and recent developments. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:1067–77. doi: 10.1021/pr301201x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau AF, Wang H, Weingarten RA, Drake SK, Suffredini AF, Garfield MK, et al. A rapid matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry-based method for single-plasmid tracking in an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2804–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00694-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Biotechnology Information. [last accessed December 2014]; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome.

- 13.Lighthouse Data. [last accessed December 2015];Digest database tool GPMAW 10. www.gpmaw.com.

- 14.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Gupta J, Program NCS, Palmore TN, Murray PR, Segre JA. Genomic insights into the fate of colistin resistance and Acinetobacter baumannii during patient treatment. Genome Res. 2013;23:1155–62. doi: 10.1101/gr.154328.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesuere B, Debyser G, Aerts M, Devreese B, Vandamme P, Dawyndt P. The Unipept metaproteomics analysis pipeline. Proteomics. 2015;15:1437–42. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesuere B, Devreese B, Debyser G, Aerts M, Vandamme P, Dawyndt P. Unipept: Tryptic peptide-based biodiversity analysis of metaproteome samples. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5773–80. doi: 10.1021/pr300576s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Picotti P, Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring-based proteomics: Workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nat Methods. 2012;9:555–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares NC, Cabral MP, Gayoso C, Mallo S, Rodriguez-Velo P, Fernandez-Moreira E, Bou G. Associating growth-phase-related changes in the proteome of Acinetobacter baumannii with increased resistance to oxidative stress. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1951–64. doi: 10.1021/pr901116r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun SH, Choi CW, Kwon SO, Park GW, Cho K, Kwon KH, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of cell wall and plasma membrane fractions from multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:459–69. doi: 10.1021/pr101012s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charretier Y, Dauwalder O, Franceschi C, Degout-Charmette E, Zambardi G, Cecchini T, et al. Rapid bacterial identification, resistance, virulence and type profiling using selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13944. doi: 10.1038/srep13944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez-Buylla A, Picazo JJ, Culebras E. Optimized method for Acinetobacter species carbapenemase detection and identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1589–92. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00181-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.