Abstract

Background

Transitions into and out of Medicaid, termed churning, may disrupt access to and continuity of care. Low-income, working adults who became eligible for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act are particularly susceptible to income and employment changes that lead to churning.

Objective

To compare health care use among adults who do and do not churn into and out of Medicaid.

Data

Longitudinal data from 6 panels of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Methods

We used differences-in-differences regression to compare health care use when adults reenrolled in Medicaid following a loss of coverage, to utilization in a control group of continuously enrolled adults.

Outcome Measures

Emergency department (ED) visits, ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission, and visits to office-based providers.

Results

During the study period, 264 adults churned into and out of Medicaid and 627 had continuous coverage. Churning adults had an average of approximately 0.05 Medicaid-covered office-based visits per month 4 months before reenrolling in Medicaid, significantly below the rate of approximately 0.20 visits in the control group. Visits to office-based providers did not reach the control group rate until several months after churning adults had resumed Medicaid coverage. Our comparisons found no evidence of significantly elevated ED and inpatient admission rates in the churning group following reenrollment.

Conclusions

Adults who lose Medicaid tend to defer their use of office-based care to periods when they are insured. Although this suggests that enrollment disruptions lead to suboptimal timing of care, we do not find evidence that adults reenroll in Medicaid with elevated acute care needs.

Keywords: Medicaid, churning, health care reform

In 2011—before the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion of Medicaid took effect in most states—nearly 30% of nonelderly, nonpregnant adults with Medicaid experienced a disruption in their coverage.1,2 The dynamic nature of Medicaid enrollment is due, in part, to the fact that eligibility for this program is based on income, which can fluctuate over time. Many low-income adults hold 1 or more part-time jobs with variable hours, making them susceptible to coverage interruptions when their Medicaid eligibility is reevaluated.3,4 In addition to income variation, individuals can lose Medicaid if they fail to provide documentation of continuing eligibility, which most states require adults to provide every 6 or 12 months, sometimes accompanying an in-person interview. These eligibility and renewal procedures can contribute to gaps in Medicaid coverage among low-income individuals, and especially those with changing family and economic circumstances.5,6

Recent studies have highlighted the potential for adults with incomes near the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility threshold to experience changes in insurance coverage as they transition between qualifying for Medicaid and qualifying for subsidized private insurance offered through health benefit exchanges.2,7 Policymakers and researchers have expressed concern that these transitions, termed “churning,” may be disruptive to the care that adults receive. Adults who churn between private insurance and Medicaid may not have access to the same networks of providers across plans, and can face higher levels of cost sharing in private insurance plans.8 In part for these reasons, adults may be unwilling or unable to purchase private insurance after losing Medicaid coverage.9–11

Interruptions in insurance coverage can be costly, both in terms of the administrative resources that are used to track enrollment transitions,12 and because disruptions in coverage may cause adults to forego routine care. Interruptions in Medicaid coverage are associated with lower rates of primary and preventive care use,13–15 and persons who defer preventive care may ultimately use more acute care services, which can lead to greater downstream health care costs. For example, one study, which focused on Medicaid coverage interruptions among children in California, estimated that the rate of pediatric hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions declined by 26% after the state provided qualifying children with 12 months of continuous Medicaid eligibility.16 Another study, which examined churning among diabetic Medicaid patients in Florida, found that hospital costs increased by $720 per person in the 3 months after adults reenrolled in Medicaid, following a gap in coverage.17 As many uninsured, low-income persons enroll in Medicaid when they receive emergency care, this evidence suggests that churning could ultimately cause Medicaid programs to bear the costs of care for reenrolling adults in high-cost delivery settings.18

We are not aware of a published study that has examined the relationship between Medicaid churning and health care use with nationally representative data, and more importantly, one that compares health care use between churning adults and those with stable Medicaid coverage. In this study, we compare monthly trends in health care use among adults who lose and subsequently reenroll in Medicaid, to those of continuously enrolled adults, using longitudinal data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). We assess whether adults who reenroll in Medicaid after losing coverage have higher rates of inpatient and emergency department (ED) use upon reenrollment, relative to continuously enrolled adults. We also consider whether churning is associated with an unstable pattern of visits to office-based providers—the setting where many patients receive primary and preventive care. By examining whether adults who experience churning defer the use of office-based care during lapses in coverage, and if they use an excess of acute care after reenrolling in Medicaid, this study may help policymakers determine whether it would be efficient to provide Medicaid beneficiaries with continuous coverage, or to adopt other policies that smooth transitions between insurance programs.19,20

METHODS

Data and Sample

We analyze longitudinal data from panels 11–16 of the MEPS, comprising individuals who were surveyed from 2006 through 2012. Individuals in the MEPS are a subsample of those surveyed in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which is conducted in the year preceding the first MEPS interview round. The MEPS follows individuals for up to 2 years, and reports episodes of health care use and Medicaid enrollment by month.21,22 We use the NHIS to obtain baseline health, demographic, and insurance enrollment data on individuals, and link this to longitudinal information on insurance status and health care use from the MEPS.

Panels 11–16 consisted of 23,578 adults who were between the ages of 19 and 62 (inclusive) at the time of their NHIS interview, and who were followed subsequently in the MEPS. We restrict our analyses to adults with incomes < 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) in the NHIS who were followed for 2 full years in the MEPS, and we exclude women who were pregnant and adults who were ever enrolled in Medicare. These adults may qualify for Medicaid through separate eligibility pathways, and will likely display different patterns of health care use than the adults we study here. (See Data Appendix Fig. A-1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B125 for a population flowchart.) This yielded an analytic sample of 5877 persons, from which we identified 264 adults who experienced Medicaid churning (see below), and 627 adults who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid.

Defining Churning

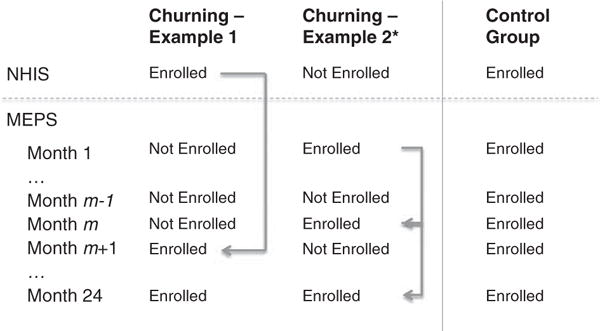

The main independent variable is a measure of Medicaid enrollment transitions, or churning, which we construct using self-reported insurance enrollment data from the NHIS and the MEPS. We define churning as an initial period of enrollment in Medicaid, followed by a loss of coverage, and subsequent reenrollment (a “churning cycle”; see Fig. 1). Our definition of churning includes adults who became uninsured (91.7% of the sample) and those who enrolled in private insurance upon leaving Medicaid (8.3%). In contrast to the large number of Medicaid beneficiaries who experienced a change in their enrollment status in a calendar year (ie, 28.9% of all Medicaid beneficiaries in 2011), only 264 (4.5%) of the adults in our sample experience at least 1 full churning cycle during the MEPS observation period. This difference reflects the fact the MEPS surveys individuals for only 24 months, which limits our ability to observe longer churning cycles. In this study, we focus on changes in health care use before and after the month in which churning adults reenroll in Medicaid.

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of churning and control group definitions. Arrows indicate full churning cycles, representing completed transitions from enrollment in Medicaid, to other insurance or no insurance, and a subsequent resumption of Medicaid coverage. Although we allow a baseline observation of Medicaid enrollment in the NHIS to contribute to our count of insurance transitions, adults must have experienced at least 1 observed disruption in Medicaid coverage, during a MEPS observation month, to contribute to our churning sample. *This second example illustrates a person with 2 full churning cycles during the observation period. In this paper, we analyze health care use only during the first episode of churning, due to the small number of adults who experience 2 or more churning cycles in our sample. MEPS indicates Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey.

Dependent Variables

We analyze monthly visits to the ED, ED visits admitted to the hospital, and visits to office-based health care providers, as reported in the MEPS. ED visits that resulted in a hospital admission may serve as an indicator for the severity of medical need. Office-based care includes visits to primary care providers and specialists. We analyze visits within these 3 categories where Medicaid is the primary payer and, in secondary analyses, visits regardless of the patient’s primary payer.

Episodes of health care use in the MEPS are self-reported, although information about visits is checked and supplemented in a follow-back survey conducted with providers. Notably, the MEPS asks individuals about all episodes of health care use, regardless of insurance status.21

Statistical Analysis

We used differences-in-differences regression to compare the change in utilization following Medicaid reenrollment among adults who experience churning, to trends in a control group. For the few adults in our sample who experience multiple episodes of churning (N = 16), we focus on use following reenrollment in the first churning cycle.

For each outcome variable, we estimate models for person i in month t of the form:

where Ci = 1 for the churning group, and equals for the control group. We center each person’s observations around the month of reenrollment in Medicaid for the churning group (t0). In the control group, t0 is the 13th month of consecutive Medicaid enrollment in the MEPS.

The variable Postit = 1 if montht − t0 ≥ 0, and is set to 0 otherwise. For each person in the churning group, we restrict the analysis period before reenrollment to those months in which the adult lacked Medicaid coverage, and the post-reenrollment period to months where the adult had Medicaid. In both groups, we analyze a window of up to 8 months around t0 (ie, 4 mo before t0, and 4 mo after). We selected this window because it captured the greatest variation in use around the month of reenrollment in the churning group (Fig. 2). Although we only focus on up to 4 months of pre-reenrollment and post-reenrollment data, we observe, on average, 9.7 months of postperiod data and 6.5 months of preperiod data across individuals in the churning sample.

FIGURE 2.

Trends in health care utilization for churning and control groups where Medicaid is the primary payer. Time zero on the horizontal axis is defined as the month in which a churning adult resumed Medicaid enrollment (for the churning group) and is the 13th month of the MEPS survey for the continuously enrolled control group. The vertical axis shows the rate of use per person-month. Graphs are plotted using a kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing function, with an Epanechnikov kernel. Graphs show utilization where Medicaid is the primary payer. We separately examined plots of utilization for all payers, and found very similar trends in the churning and control groups. A, Emergency department visits; B, Emergency department visits admitted inpatient; C, Office-based provider visits. CI indicates confidence interval.

The parameters γ1 through γ4 of the above equation capture linear time trends before and after t0, for the churning and control groups. Using estimates for these parameters, we calculate a cumulative change in use from the start to the end of the 8-month period spanning Medicaid reenrollment in the churning group, and compare this with the analogous change in the control group. We report this comparison as a “cumulative difference-in-differences.”

The regressions use within-person variation in Medicaid enrollment and health care use. Time-invariant characteristics of individuals are controlled in the difference-in-differences model. As such, we do not directly control for demographic or disease characteristics, which should remain constant over the short time period over which we observe individuals. We estimate linear regressions with robust SEs clustered by state, and do not incorporate survey weights. Additional details regarding our empirical methods, including a description of the cumulative difference-in-differences calculation, are provided in the Technical Appendix (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B125). All analyses were conducted in Stata 13 (College Station, TX).

Sensitivity Analyses

We report the results of 2 sensitivity analyses. First, we reestimate our models after including visits covered by all payers, including uninsured visits, in the dependent variable. We did this to check whether changes in Medicaid enrollment led to changes in overall utilization, or alternatively, to a change in the mix of visits where Medicaid was the primary payer. Second, to investigate whether the length of a Medicaid coverage gap is associated with utilization, we estimate stratified regressions that separately compare use in the control group: (1) to utilization among churning adults who lost Medicaid coverage for between 1 and 5 months, and (2) to adults whose Medicaid coverage gap was 6 months or longer.

RESULTS

Study Sample

Our sample consisted of 264 adults who experienced churning and 627 adults who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid (Table 1). Adults in the churning group were approximately 4 years younger than those in the control group (mean baseline age of 36.5 in the churning group vs. 40.8 in the control group), although this difference was not statistically significant at P < 0.05. Churning adults were slightly more likely to have incomes between 100% and 200% of the FPL than the controls, suggesting that persons at somewhat higher income levels are more likely to experience earnings variation that results in a loss of Medicaid eligibility. The point estimates for disease prevalence indicate that adults in the control group are more likely to have heart disease, hypertension, and asthma compared with those in the churning group; however, not all differences are statistically significant, due in part to small sample sizes. These descriptive characteristics are similar to those reported in another study of Medicaid churning.23

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Churning and Control Groups as Reported in the NHIS Baseline Survey

| Mean

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Churning Group (n = 264) | Control Group (n = 627) | |

| Mean age | 36.534 | 40.781 |

| % Male | 0.279 | 0.276 |

| Enrolled in Medicaid (at baseline) | 0.757 | 1.000 |

| Gap in Medicaid coverage before reenrollment (mo)* | 6.504 | — |

| Family income as % of FPL | ||

| < 50% FPL | 0.281 | 0.276 |

| 50%–74% FPL | 0.157 | 0.295 |

| 75%–99% FPL | 0.181 | 0.159 |

| 100%–124% FPL | 0.112 | 0.137 |

| 125%–149% FPL | 0.124 | 0.075 |

| 150%–174% FPL | 0.104 | 0.027 |

| 175%–199% FPL | 0.041 | 0.031 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 0.467 | 0.443 |

| Black | 0.210 | 0.290 |

| Hispanic | 0.250 | 0.193 |

| Other | 0.073 | 0.074 |

| BMI | ||

| 10 < BMI ≤ 20 | 0.050 | 0.083 |

| 20 < BMI ≤ 30 | 0.538 | 0.472 |

| 30 < BMI ≤ 40 | 0.287 | 0.293 |

| BMI > 40 | 0.125 | 0.151 |

| Disease history | ||

| Any heart disease history | 0.042 | 0.101† |

| Any hypertension history | 0.299 | 0.356 |

| Any heart attack history | 0.041 | 0.046 |

| Any diabetes | 0.122 | 0.145 |

| Any asthma history | 0.198 | 0.238 |

| Joint pain in past 30 d | 0.377 | 0.411 |

| Any functional limitations | 0.566 | 0.581 |

Authors’ calculations for the NHIS 2005–2010 linked to the MEPS sample (from panels 11 to 16). Characteristics of persons (except for Medicaid enrollment statistics) are at the time of the NHIS survey, which occurred between 6 and 12 months before the first MEPS survey round.

In our churning sample, 117 adults had a gap in Medicaid coverage of 6 months or longer, whereas 147 had a coverage gap of 1–5 months.

Control group is statistically different from the churning group at P < 0.05.

BMI indicates body mass index; FPL, federal poverty level; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey.

Trends in the Churning and Control Groups

Figure 2 plots trends in health care utilization for the churning group, before and after Medicaid reenrollment (solid lines), relative to the continuously enrolled control group (dashed lines). The zero point on the horizontal axis represents the month when churning adults reenrolled in Medicaid, and represents the 13th consecutive month of enrollment in the control group. To the left of this point, we plot the average utilization trend for churning adults for those months in which they had private insurance or were uninsured; to the right of zero, we plot utilization in months when these adults had Medicaid.

Panel (A) shows the trend in ED visits for claims where Medicaid is listed as the primary payer. Four months before Medicaid reenrollment, persons in the churning group had relatively few ED visits. Notably, the rate of Medicaid ED visits begins to increase in the churning group 4 months before reenrollment—the period when these adults indicated that they had no Medicaid coverage. After reenrollment, visits continued to increase in the churning group, although at a slower pace than before. In contrast, adults who retained Medicaid without interruption had a relatively constant rate of ED use throughout the observation period (approximately 0.04 visits per person per month). Although the graph does show evidence of a growing rate of ED visits in the churning group after Medicaid reenrollment, inspection of the confidence intervals indicates that use in the churning group is not statistically different from use in the control group. However, our ability to detect differences between the groups is dampened by the fact the churning group is small, and that it contributes fewer observations at points further in time from adults’ Medicaid reenrollment dates.

Panel (B) shows the analogous trends for Medicaid-covered ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission. Here, we do not find evidence that admitted ED visits increase around the time of Medicaid reenrollment in the churning group, compared with the control group.

Panel (C) shows the results for office-based visits. Four months before reenrolling, adults in the churning group had an average of approximately 0.05 Medicaid-covered office-based visits per month, significantly below the rate of about 0.20 visits per month in the control group. Over the observation period, office-based visits exhibit an upward trend in the churning group. However, the average visit rate in the churning group does not reach that of the control group until the end of our observation period—between 2 and 4 months after the churning adults had returned to Medicaid. By contrast, the use of office-based visits was largely stable in the control group.

Regression Results

Our main regression results are presented in Table 2. The coefficients in this table can be interpreted as changes in the per-person per-month rate of use for a particular service. For most of the outcomes we evaluate, we find that the churning group exhibits an increasing rate of health care use after Medicaid reenrollment, although this change is small. For example, the monthly rate of Medicaid-covered ED visits increased among churning adults by 0.004 (P = 0.60) visits per person per month after reenrollment. Similarly, the rate of visits to office-based providers increased by 0.015 (P = 0.20) after reenrollment in the churning group.

TABLE 2.

Difference-in-Differences Regression Estimates

| Medicaid ED Visits | Medicaid ED Visits Admitted Inpatient | Medicaid Office-based Visits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Churning group: Ci | 0.025 (0.021) | −0.012 (0.008) | −0.063 (0.027)* |

| Postperiod: Postit | 0.009 (0.012) | −0.005 (0.005) | 0.052 (0.016)** |

| Main difference-in-differences estimate: Postit × Ci | −0.023 (0.024) | 0.013 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.038) |

| Linear time trend in the preperiod: (montht − t0) × (1 − Postit) | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.002)* | −0.006 (0.007) |

| Linear time trend in the postperiod: (montht − t0) × Postit | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.005 (0.005) |

| Linear time trend in the preperiod for the churning group: (monthi − t0) × (1 − Postit) × Ci | 0.015 (0.007)* | −0.003 (0.003) | 0.016 (0.009) |

| Linear time trend in the postperiod for the churning group: (monthi − t0) × Postit × Ci | 0.004 (0.007) | −0.003 (0.002)○ | 0.015 (0.011) |

| Cumulative difference-in-differences | 0.053 (0.028)○ | −0.013 (0.008) | 0.119 (0.037)** |

| Observations | 7726 | 7726 | 7726 |

| R2† | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

The dependent variables include only those visits where Medicaid was listed as the primary payer. The unit of analysis is a person-month. Robust SEs clustered by state are shown in parentheses. The model intercepts are not shown.

Significance markings are as follows:

P < 0.10.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

The corresponding F statistics are all significant at P < 0.05 or better.

ED indicates emergency department.

The cumulative difference-in-differences estimates indicate that, over our 8-month observation period, Medicaid-covered ED utilization increased by 0.053 (P = 0.07) visits per person per month, relative to the control group. Similarly, the rate of visits to office-based providers increased cumulatively by 0.119 (P < 0.01), relative to the control group. We did not find statistically significant cumulative changes in admitted ED visits.

Of note, we found that churning adults visit office-based providers in a concentrated window of time when they have coverage, and have fewer visits once they lose Medicaid. To illustrate this, in a supplemental analysis (Data Appendix Fig. A-2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B125), we plot utilization trends before Medicaid dis-enrollment in the churning group. The rate of Medicaid-covered visits to office-based providers is about 0.15 per person per month in the churning group before these adults lose Medicaid, and is comparable to the use rate in the control group. Use in the churning group falls significantly below the controls after these adults lose Medicaid, and only returns to its original level between 2 and 4 months after reenrollment.

Data Appendix Table A-1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B125) presents our sensitivity analysis results. In panel I, we report estimates for postenrollment utilization for all payers. In general, our estimates are similar to our main analyses, but indicate smaller cumulative changes in use. Panels II and III demonstrate that cumulative changes in office-based visits, over our 8-month observation period, are greater for adults with Medicaid coverage gaps of at least 6 months (N = 117), versus adults with shorter coverage gaps (N = 147). We do not find evidence that cumulative changes in ED visits are greater for adults with relatively longer, versus shorter, coverage gaps. However, it bears noting that none of our models explain much variation in utilization, with R2 all < 1%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examine changes in health care use that occur when adults reenroll in Medicaid following an interruption in coverage, and compare these changes with utilization among low-income adults with continuous Medicaid coverage. Our analysis of a sample of churning adults shows that the rate of visits to office-based providers falls significantly below that of continuously enrolled adults when churning adults lose Medicaid coverage, and only returns to a level that is comparable to the control group several months after reenrollment. This lag between a resumption of Medicaid coverage and a return to “steady state” levels of utilization suggests that churning in Medicaid is disruptive to beneficiaries’ access to office-based providers, as it may take time to establish provider contacts after a loss of coverage. In addition, we find that longer Medicaid coverage gaps are associated with larger cumulative changes in visits to office-based providers through an episode of churning. This demonstrates that longer uninsurance spells are associated with more volatile patterns of health care use.

We had hypothesized that the deferred use of office-based care (including preventive services) in the churning group would be associated with elevated acute care use once adults reenroll in Medicaid. Although we find that visits to the ED are increasing in the churning group around the time of reenrollment, we do not find statistically significant evidence of elevated ED use after the resumption of Medicaid coverage, even among adults with coverage gaps of 6 months or longer. Our inability to detect such adverse effects of gaps in health insurance coverage may be due, in part, to the small size of the churning group, the relatively short window of time around each churning event, and our focus on a single churning event for each individual. It may take repeated interruptions in coverage, occurring over a longer time frame than we can observe in the MEPS, for the adverse health effects of churning to materialize. Thus, although our results do not allow us to conclude that Medicaid programs bear higher costs of inpatient and ED care when adults who churn reenroll in Medicaid, they do not rule out the potential for long-run savings to Medicaid programs from policies that reduce churning.

A major goal of the ACA is to increase the level and continuity of primary care use, with the accompanying objective of reducing spending on potentially avoidable episodes of high-cost inpatient and ED care. Our analyses demonstrate that churning disrupts low-income adults’ visits to office-based providers, including those who deliver primary and preventive care. Researchers and policy analysts have proposed a number of policies to mitigate the disruptive effect of churning on ambulatory care use, including: (1) providing 12 months of guaranteed Medicaid eligibility to low-income adults; (2) establishing Basic Health Plans for adults with incomes of up to 200% of the FPL, to which adults can transition when their incomes rise above the Medicaid eligibility threshold; and (3) better connecting the health insurance plans that participate in the ACA’s marketplace exchanges with Medicaid managed care programs.19,20,24 This latter option is now being tested in Arkansas, which implemented its Medicaid expansion using a premium assistance model that allows low-income adults to purchase subsidized health insurance through the state’s exchange. The level of premium assistance will decline as incomes rise, but will not always require adults to change insurance plans. Alternatively, states could contract with Medicaid managed care plans that also participate in the health insurance exchanges. To the extent that plans participating in both types of markets use the same provider networks, transitions between plans due to churning may lead to fewer disruptions in care.25 Recent work has found that Medicaid managed care plans that are integrated with private insurers are more likely to steer their Medicaid enrollees to primary care providers who serve their networks of privately insured patients, as opposed to providers who mostly accept Medicaid.26 The extent to which these plans may be successful in reducing churning-related disruptions in care remains unknown.

Our study has several limitations. First, our definition of churning provides a small sample of adults that limits the statistical precision of our estimates. We pooled all publicly available panels of the MEPS for which there was sufficient information on key inclusion criteria, such as pregnancy status, to select patients for our analysis. Related to the small sample size, the number of observations diminishes at time points further from the month of reenrollment. Second, the MEPS provides only 24 months of observations on individuals, which limits our ability to examine the effects of churning on health and health care use over the long term. Third, because the MEPS does not report income on a monthly basis, we are unable to determine whether adults who churned remained eligible for Medicaid but did not reapply, or if they became ineligible due to income or employment changes. In a supplementary analysis, presented in the Data Appendix (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B125), we show that the churning episodes we study are, in fact, related to employment transitions. More specifically, we show that adults tend to reenroll in Medicaid after losing full-time employment in firms that offer health insurance benefits (see Appendix Fig. A-3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/B125).

Fourth, insurance enrollment and health care use are self-reported in the MEPS. Our finding that the use of Medicaid-covered services increases before reenrollment in the churning group suggests that knowledge of Medicaid participation might lag changes in actual enrollment status by 1 or several months. Researchers have also found that MEPS respondents tend to underreport certain episodes of health care use. Comparisons of Medicare claims to the MEPS have revealed a pattern of underreporting of visits to office-based providers and to the ED in the MEPS, particularly among nonwhites and those with lower levels of income and education.27 Although this suggests that the level of health care use may be misreported by the adults in our sample, to the extent that these individuals consistently misreport utilization over time, our analysis will still correctly measure changes in use through an episode of churning. Future work could harness the growing availability of all-payer claims databases to more accurately examine how health care use varies with changes in insurance status, and to examine longer-term effects of insurance transitions on health care use.

CONCLUSIONS

Low-income adults who experience gaps in Medicaid coverage defer their use of office-based care to periods when they are insured. Although enrollment disruptions may lead to a suboptimal timing of care, we do not find evidence that adults reenroll in Medicaid with acute care needs that make them significantly more likely to use inpatient or emergency care than continuously enrolled adults. Further research is needed to study the long-run consequences of repeated coverage interruptions on health and health care use. Encouraging the integration of provider networks for Medicaid programs and private insurance plans offered through the ACA’s health benefit exchanges is among several steps that policymakers can take to mitigate the disruptive effect of churning on health care use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ray Kuntz at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for assistance using the MEPS, Darrell Gaskin for helpful comments, and May Li for research assistance.

Supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. E.T.R. also received financial support from the Jayne Koskinas Ted Giovanis Foundation for Health and Policy. C.E.P. is supported by a career development award from the National Cancer Institute and the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (1K07CA151910).

This work does not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Fund or the Jayne Koskinas Ted Giovanis Foundation.

E.T.R. was in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health at the time this research was conducted.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

References

- 1.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Authors’ Calculations From the 2011 MEPS-Household Component. Rockville, MD: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD, Rosenbaum S. Issues in health reform: how changes in eligibility may move millions back and forth between Medicaid and insurance exchanges. Health Aff. 2011;30:228–236. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyman K, Elmendorf D, Schiel D. The evolution of income volatility. Brookings Institution Paper; 2012. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2013/1/household-income-volatility-dynan/household-income-volatility-dynan.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irregular work scheduling and its consequences. Economic Policy Institute; 2015. Available at: http://www.epi.org/publication/irregular-work-scheduling-and-its-consequences/. Accessed April 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Holding Steady, Looking Ahead: Annual Findings of a 50-State Survey of Eligibility Rules, Enrollment, and Renewal Procedures, and Cost Sharing Practices in Medicaid and CHIP Table 14: Renewal Periods and Streamlined Renewal Processes for Parents in Medicaid. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenney GM, Lynch V, Haley J, et al. Variation in Medicaid eligibility and participation among adults: implications for the Affordable Care Act. Inquiry. 2012;49:231–253. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.03.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommers BD, Graves JA, Swartz K, et al. Medicaid and marketplace eligibility changes will occur often in all states; policy options can ease impact. Health Aff. 2014;33:4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra V, McMahon S. Minimizing care gaps for individuals churning between the marketplace and Medicaid: key state considerations. Center for health care strategies issue brief. 2014 Available at: http://www.chcs.org/media/Churn_1_30_2014_final.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- 9.Hayes SL, Schoen C. Stop the churn: preventing gaps in health insurance coverage. Commonwealth fund blog post. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum S. Report on health reform implementation addressing Medicaid/marketplace churn through multimarket plans: assessing the current state of play. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40:233–242. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2854855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buettgens M, Nichols A, Dorn S. Churning under the ACA and state policy options for mitigation. Urban Institute policy brief. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irvin C, Peikes D, Trenholm C, et al. Discontinuous coverage in Medicaid and the implications of 12-month continuous coverage for children. Mathematica Policy Research Report. 2001 Available at: http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/media/publications/PDFs/discontinuous.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 13.Lavarreda SA, Gatchell M, Ponce N, et al. Switching Health Insurance and its effects on access to physician services. Med Care. 2008;46:1055–1063. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318187d8db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson LM, Tang SF, Newacheck PW. Children in the United States with discontinuous health insurance coverage. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:382–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdus S. Part-year coverage and access to care for nonelderly adults. Med Care. 2014;52:709–714. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bindman AB, Chattopadhyay A, Auerback GM. Medicaid re-enrollment policies and children’s risk of hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Med Care. 2008;46:1049–1054. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185ce24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall AG, Harman JS, Zhang J. Lapses in Medicaid coverage: impact on cost and utilization among individuals with diabetes enrolled in Medicaid. Med Care. 2008;46:1219–1225. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d695c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haber SG, Khatutsky G, Mitchell JB. Covering uninsured adults through Medicaid: lessons from the Oregon Health Plan. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;22:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingram C, McMahon SM, Guerra V. Creating seamless transitions between Medicaid and the exchanges. State Health Reform Assistance Network policy brief. 2012 Available at: http://statenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/State-Network-CHCS-Seamless-Coverage-Transitions-April-2012.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- 20.Rosenbaum S, Lopez N, Dorley M, et al. Mitigating the effects of churning under the Affordable Care Act: lessons from Medicaid. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2014;12:1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JW, Monheit AC, Beauregard KM, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996/97;33:373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS survey background. 2009 Available at: http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp Accessed April 12, 2015.

- 23.Sommers BD. Loss of health insurance among non-elderly adults in Medicaid. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;24:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum S, Sommers BD. Using Medicaid to buy private health insurance—the great new experiment? N Engl J Med. 2013;369:7–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1304170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid expansion in Arkansas. 2015 Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-arkansas/. Accessed June 8, 2015.

- 26.Roberts ET. An Analysis Using Massachusetts Data [unpublished PhD dissertation] Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2015. Do Medicaid MCOs Affect Office-based Physicians’ Incentives to Participate in Medicaid? [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuvekas SH, Olin GL. Validating household reports of health care use in the medical expenditure panel survey. Health Serv Res. 2006;44:1679–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.