Abstract

BACKGROUND

Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy is associated with increased melanoma-specific survival (i.e., survival until death from melanoma) among patients with node-positive intermediate-thickness melanomas (1.2 to 3.5 mm). The value of completion lymph-node dissection for patients with sentinel-node metastases is not clear.

METHODS

In an international trial, we randomly assigned patients with sentinel-node metastases detected by means of standard pathological assessment or a multimarker molecular assay to immediate completion lymph-node dissection (dissection group) or nodal observation with ultrasonography (observation group). The primary end point was melanoma-specific survival. Secondary end points included disease-free survival and the cumulative rate of nonsentinel-node metastasis.

RESULTS

Immediate completion lymph-node dissection was not associated with increased melanoma-specific survival among 1934 patients with data that could be evaluated in an intention-to-treat analysis or among 1755 patients in the per-protocol analysis. In the per-protocol analysis, the mean (±SE) 3-year rate of melanoma-specific survival was similar in the dissection group and the observation group (86±1.3% and 86±1.2%, respectively; P=0.42 by the log-rank test) at a median follow-up of 43 months. The rate of disease-free survival was slightly higher in the dissection group than in the observation group (68±1.7% and 63±1.7%, respectively; P=0.05 by the log-rank test) at 3 years, based on an increased rate of disease control in the regional nodes at 3 years (92±1.0% vs. 77±1.5%; P<0.001 by the log-rank test); these results must be interpreted with caution. Nonsentinel-node metastases, identified in 11.5% of the patients in the dissection group, were a strong, independent prognostic factor for recurrence (hazard ratio, 1.78; P=0.005). Lymphedema was observed in 24.1% of the patients in the dissection group and in 6.3% of those in the observation group.

CONCLUSIONS

Immediate completion lymph-node dissection increased the rate of regional disease control and provided prognostic information but did not increase melanoma-specific survival among patients with melanoma and sentinel-node metastases. (Funded by the National Cancer Institute and others; MSLT-II ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00297895.)

Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy is a standard procedure in the care of appropriately selected patients with melanoma. The first Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-I) confirmed the value of early nodal evaluation and treatment.1–3 This prospective, international, randomized trial showed that the pathologic status of the sentinel node or nodes was the most important prognostic factor and that patients who underwent sentinel-node biopsy had fewer recurrences of melanoma than patients who underwent wide excision and nodal observation. Among patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas (defined as 1.2 to 3.5 mm) and nodal metastases, early surgical treatment, guided by sentinel-node biopsy, was associated with increased melanoma-specific survival (survival until death from melanoma). These results provide support for the recommendation by several professional organizations that staging by means of sentinel-node biopsy should be performed when appropriate.4–7

Currently, immediate completion lymph-node dissection (removal of the remaining regional lymph nodes after sentinel-node excision) is usually recommended for patients with sentinel-node metastases. However, prospective evidence of the efficacy of completion lymph-node dissection is lacking, and the procedure carries a risk of adverse events.8 Results of retrospective evaluations of the usefulness of completion lymph-node dissection are inconclusive.9–11 Available data from one prospective study do not suggest a benefit from immediate dissection, but this study is not sufficiently powered to rule out a clinically significant benefit.12 In addition, in most patients, nodal disease is limited to the sentinel lymph node or nodes and is removed by means of biopsy. Conversely, patients with even microscopic involvement of nonsentinel nodes have an overall poorer prognosis and outcomes that are similar to those in patients with clinically apparent nodal disease.13,14

In the second Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-II), we evaluated the usefulness of completion lymph-node dissection in patients with melanoma and sentinel lymph-node metastases as compared with observation with frequent nodal ultrasonography and dissection only in patients in whom clinically detected nodal recurrence had developed.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

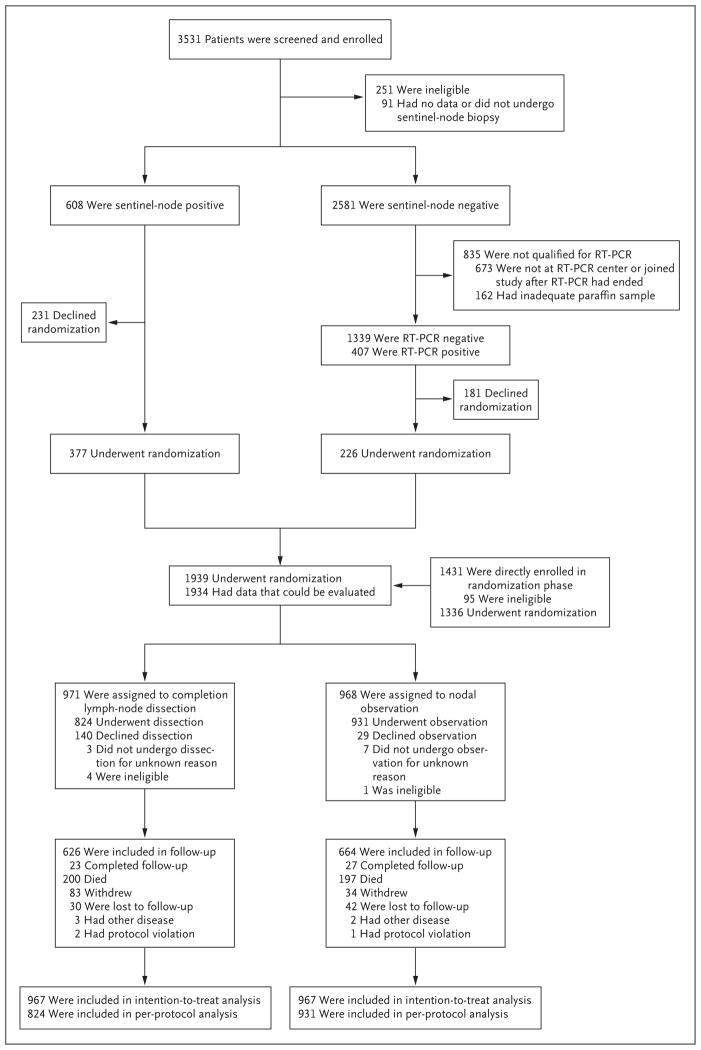

MSLT-II, an international, multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial to evaluate the usefulness of completion lymph-node dissection in patients with melanoma and sentinel-node metastases, consisted of a screening phase in which patients were enrolled before sentinel-node biopsy and a randomization phase in which completion lymph-node dissection was compared with observation and nodal ultrasonography (Fig. 1). The trial was conducted at 63 centers.

Figure 1. Trial Design, Enrollment, and Outcomes.

RT-PCR denotes reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

MSLT-II was designed by the MSLT-II executive committee with input from the pathology and ultrasonography oversight committees (see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Data were collected prospectively on paper and later on Web-based case-report forms. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses reported and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol, available at NEJM.org.

Nodal metastasis was determined by means of standard pathological assessment (including immunohistochemical tests performed according to institutional protocols) or by means of a previously described quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay during the screening phase.15 Patients had to have undergone randomization and completion lymph-node dissection within 140 days after diagnostic biopsy.

The randomization phase involved enrollment of patients who had undergone screening and had pathologically or molecularly positive sentinel-node metastases and patients who had not undergone screening in whom sentinel-node metastases were detected by means of pathological assessment. In the randomization phase, fewer patients with RT-PCR–positive findings than anticipated were enrolled. In 2012, the data and safety monitoring board determined that such patients should no longer undergo randomization, since attainment of sufficient power to evaluate a therapeutic effect in that group was not feasible. The data and safety monitoring board recommended continued follow-up of these patients to assess outcomes.

At the third interim analysis, the data and safety monitoring board determined that detection of a significant survival difference between the trial groups was unlikely and recommended that the current primary end-point data be released. Intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses of the outcome variables showed similar results. Results of per-protocol analyses are reported in this article, since they are likely to be the most clinically pertinent. The intention-to-treat data for the primary end point (melanoma-specific survival) are provided in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

PATIENTS

Eligible patients who provided written informed consent were randomly assigned to undergo completion lymph-node dissection or nodal observation. These patients were 18 to 75 years of age and had clinically localized cutaneous melanoma, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1 (on a 5-point scale, with 0 indicating an absence of disability and higher numbers indicating greater disability), a non–melanoma-related life expectancy of 10 years or more, and a tumor-positive sentinel node. The trial was opened before the universal application of registration. The trial opened in December 2004 and was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov on February 27, 2006. At the time of registration, 119 patients had been enrolled in the trial.

Randomization was performed in a 1:1 ratio with the use of a permuted-block design, which was stratified according to Breslow thickness, ulceration, method of metastasis detection (standard pathological assessment or RT-PCR assay), and enrollment at an MSLT-I center. Patients who were assigned to the observation group were monitored by means of clinical examination every 4 months during the first 2 years, every 6 months during years 3 through 5, and then annually. Nodal ultrasonographic assessment of the sentinel-node basin occurred at each visit for the first 5 years; findings were considered to be abnormal on the basis of a length:depth ratio of less than 2, a hypoechoic center, an absence of hilar vessels, or focal nodularity with increased vascularity. Follow-up of the dissection group involved the same schedule, but without protocol-mandated nodal ultrasonography.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For the primary end point, melanoma-specific survival, we used the log-rank test to compare the rates among patients in the dissection group and the observation group in the intention-to-treat population. Secondary end points included overall survival, disease-free survival, survival without recurrence of regional nodal metastases, distant metastasis–free survival, and the extent of nodal involvement. Time zero was the time of randomization. Melanoma-specific survival was determined at the time of melanoma-related death. Disease-free survival was the time to any recurrence. Survival without nodal recurrence was the time to recurrence within the draining nodal basin. For survival, comparisons between the two groups were performed by means of the log-rank test for univariable testing and Cox regression for adjusted comparisons. Nodal recurrence occurred in a draining regional basin, local and in-transit recurrence occurred between the primary site and the regional basin, and distant recurrence occurred beyond the regional basin.

We estimated that with a total sample of 1925 patients, the trial would have a power of 83% to detect a between-group difference of 5 percentage points in melanoma-specific survival. All tests were two-tailed. Power was reassessed by the data and safety monitoring board before closure of enrollment to ensure that an adequate sample size had been obtained. The cumulative rate of nonsentinel-node metastases was determined by clinical follow-up in the observation group and according to total in-basin nodal recurrence or nonsentinel-node metastasis on immediate completion lymph-node dissection in the dissection group.

Data were summarized with means and standard deviations, medians and ranges, or both in the intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses. Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare results for patients in the dissection group who actually underwent completion lymph-node dissection (these patients were included in the per-protocol and intention-to-treat analyses) with results for those who did not undergo the assigned completion lymph-node dissection (these patients were included only in the intention-to-treat analysis). Survival curves were computed with the use of the Kaplan–Meier method and stratified according to group alone or according to group and method of metastasis detection (pathological assessment vs. RT-PCR). Cox proportional-hazards regression models were constructed separately for the two groups; these models included demographic factors, trial stratification factors, and nonsentinel-node metastasis at the time of completion lymph-node dissection. Subgroup analyses included subgroups that were defined according to the patients’ sex and age, the Breslow thickness, the location and number of positive nodes, and the presence or absence of ulceration. Cox proportional-hazards regression was used to estimate the subgroup-specific hazard ratios.

RESULTS

PATIENTS

From December 2004 through March 2014, a total of 3531 patients were enrolled in the screening phase and 1939 patients underwent randomization (Fig. 1). Demographic and pathologic features of the dissection and observation groups were similar (Table 1, and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). A greater proportion of patients assigned to completion lymph-node dissection than to observation declined their assigned treatment. However, the per-protocol cohorts were similar with respect to prognostic factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients in the Per-Protocol Analysis.*

| Characteristic | Dissection (N = 824) | Observation (N = 931) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex — no. (%) | ||

| Female | 346 (42.0) | 382 (41.0) |

| Male | 478 (58.0) | 549 (59.0) |

| Age — yr | ||

| Mean | 52.5±12.9 | 53.2±13.6 |

| Median (range) | 53.7 (18–76) | 54.9 (19–76) |

| Smoking status — no./total no. (%)† | ||

| Never | 463/803 (57.7) | 522/907 (57.6) |

| Former | 193/803 (24.0) | 227/907 (25.0) |

| Current | 147/803 (18.3) | 158/907 (17.4) |

| Breslow thickness | ||

| Mean — mm | 2.76±2.34 | 2.70±2.11 |

| Median (range) — mm | 2.10 (0.34–28.0) | 2.10 (0.35–30.0) |

| <1.50 mm — no. (%) | 237 (28.8) | 257 (27.6) |

| 1.50–3.50 mm — no. (%) | 404 (49.0) | 462 (49.6) |

| >3.50 mm — no. (%) | 183 (22.2) | 212 (22.8) |

| Primary site — no. (%) | ||

| Arm or leg | 327 (39.7) | 382 (41.0) |

| Head or neck | 113 (13.7) | 128 (13.7) |

| Trunk | 384 (46.6) | 421 (45.2) |

| Ulceration — no. (%) | ||

| Absent | 508 (61.7) | 578 (62.1) |

| Present | 316 (38.3) | 353 (37.9) |

| No. of positive sentinel lymph nodes — no. of patients (%) | ||

| 0, RT-PCR–positive | 80 (9.7) | 111 (11.9) |

| 1 | 596 (72.3) | 643 (69.1) |

| 2 | 121 (14.7) | 162 (17.4) |

| 3 | 18 (2.2) | 10 (1.1) |

| >3 | 9 (1.1) | 5 (0.5) |

| Diameter of sentinel-lymph-node metastasis — mm‡ | ||

| Mean | 1.07 | 1.11 |

| Median | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| Interquartile range | 0.27–1.32 | 0.23–1.38 |

| Size of sentinel-lymph-node metastasis — no. of patients/total no. (%) | ||

| <0.1 mm | 45/566 (8.0) | 65/623 (10.4) |

| 0.1–1.0 mm | 333/566 (58.8) | 343/623 (55.1) |

| >1.0 mm | 188/566 (33.2) | 215/623 (34.5) |

| Received adjuvant therapy — no./total no. (%)§ | 66/814 (8.1) | 60/922 (6.5) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. There were no significant between-group differences in the characteristics listed here. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. RT-PCR denotes reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Data were missing for 21 patients in the dissection group and 24 patients in the observation group.

The sentinel-node metastasis burden, the longest diameter of the largest tumor deposit, was not available for 178 patients in the dissection group and 197 patients in the observation group.

Data were not available for 10 patients in the dissection group and 9 patients in the observation group.

In the dissection group, 143 patients were excluded from the per-protocol analysis. Of those patients, 140 declined the assigned treatment. Patients who were excluded from the per-protocol analysis were more likely than patients who were not excluded to have never smoked, to have nonulcerated primary tumors, and to have an RT-PCR–positive sentinel node (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The sentinel-node tumor burden in both groups was low; the median diameter of the largest tumor deposit was 0.61 mm in the dissection group and 0.67 mm in the observation group.

SURVIVAL RATES

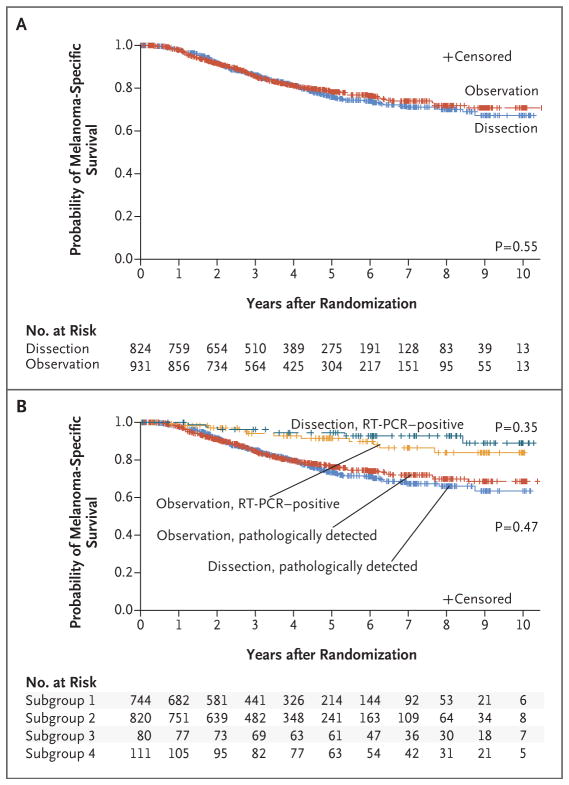

At 3 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in the mean (±SE) rate of melanoma-specific survival between the dissection group and the observation group in the per-protocol analysis (86±1.3% and 86±1.2%, respectively; P=0.42 by the log-rank test) (Fig. 2A) or the intention-to-treat analyses (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). In addition, there was no significant between-group difference in melanoma-specific survival after adjustment for other prognostic factors (hazard ratio for death, 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.88 to 1.34; P = 0.42).

Figure 2. Melanoma-Specific Survival, According to Trial Group and Method of Detection of Metastasis.

Panel A shows melanoma-specific survival according to trial group (completion lymph-node dissection or observation) in the per-protocol analysis. Panel B shows melanoma-specific survival according to the method of detection of sentinel-node metastasis (RT-PCR or pathological assessment). Subgroup 1 comprised patients in the dissection group with pathologically detected metastases; subgroup 2, patients in the observation group with pathologically detected metastases; subgroup 3, those in the dissection group with RT-PCR–detected metastases; and subgroup 4, those in the observation group with RT-PCR–detected metastases. P values were calculated with the use of log-rank tests.

An analysis with available follow-up data suggested that an RT-PCR–positive sentinel node did not have an effect on survival that was as negative as the effect anticipated in the statistical design of the trial, so the results from the two groups are also reported separately here and in the remaining analyses (Fig. 2B). The results of an analysis of both groups together are shown in Figure S2 in the Supplementary Appendix. A subgroup analysis, including an analysis based on sentinel-node tumor burden, did not reveal any subgroups that derived a significant melanoma-specific survival benefit from completion lymph-node dissection (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

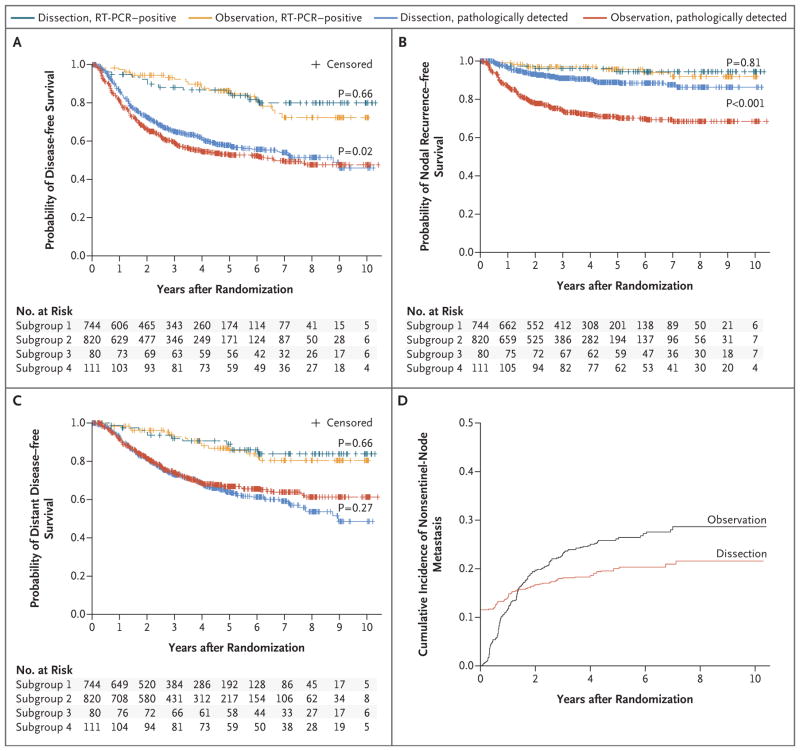

At 3 years of follow-up, the rate of disease-free survival was slightly higher in the dissection group than in the observation group (68±1.7% and 63±1.7%, respectively; P=0.05 by the log-rank test) (Fig. 3A, and Fig. S2A in the Supplementary Appendix), although the results of secondary outcome analyses must be viewed cautiously given the lack of significance for the primary end point. This difference in disease-free survival appears to result from a reduction in the rate of nodal recurrence after completion lymph-node dissection (Fig. 3B, and Fig. S2B in the Supplementary Appendix). This corresponds to an increase in the rate of disease control in the regional nodes at 3 years (92±1.0% in the dissection group vs. 77±1.5% in the observation group, P<0.001 by the log-rank test). After adjustment, the rate of nodal recurrence among patients with sentinel-node metastases detected by means of pathological assessment was 69% lower in the dissection group than in the observation group (hazard ratio, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.41; P<0.001). No significant between-group difference in distant metastasis–free survival was detected (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.31; P = 0.31) (Fig. 3C, and Fig. S2C in the Supplementary Appendix). Types of initial recurrence are listed in Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Figure 3. Disease-free Survival, Survival without Nodal Recurrence, and Distant Metastasis–free Survival, According to Trial Group, and the Cumulative Rate of Nonsentinel-Node Metastasis.

Panel A shows disease-free survival, Panel B shows survival without nodal recurrence, and Panel C shows distant metastasis–free survival according to trial group (completion lymph-node dissection or observation). Subgroup 1 comprised patients in the dissection group with pathologically detected metastases; subgroup 2, patients in the observation group with pathologically detected metastases; subgroup 3, those in the dissection group with RT-PCR–detected metastases; and subgroup 4, those in the observation group with RT-PCR–detected metastases. Panel D shows the cumulative rate of nonsentinel-node metastasis among patients in the dissection group who had positive findings on pathological assessment or nodal recurrence and among patients in the observation group who had nodal recurrence. P values were calculated with the use of log-rank tests.

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Potential prognostic factors affecting melanoma-specific survival were examined. Since the pathologic status of nonsentinel nodes was unknown in the observation group, the two groups of the trial were considered separately. In the entire trial (including patients with positive RT-PCR results), Breslow thickness and the number of sentinel nodes that were positive on pathological assessment (0 vs. >0) were significant prognostic factors in both groups, and male sex was a significant prognostic factor in the observation group (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, since the RT-PCR group appeared to be prognostically distinct, an analysis was also performed that included only patients with sentinel nodes that were positive on pathological assessment (Table 2). In the observation group, male sex was no longer a significant prognostic factor, and it remained nonsignificant in the dissection group. Breslow thickness was a significant prognostic factor in both groups, and the pathologic status of nonsentinel nodes was a significant prognostic factor in the dissection group (hazard ratio for death, 1.78; P = 0.005). The number of involved sentinel nodes was not a significant prognostic factor.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios for Melanoma-Related Death, According to Multivariable Prognostic Factors.*

| Prognostic Factor | Dissection | Observation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Sex: male vs. female | 1.13 (0.80–1.59) | 0.50 | 1.41 (0.98–2.05) | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| Age, per 1-yr increase | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.93 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.15 |

|

| ||||

| Breslow thickness | ||||

|

| ||||

| <1.50 mm† | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| 1.50–3.50 mm | 1.64 (0.96–2.79) | 0.07 | 2.46 (1.34–4.53) | 0.004 |

|

| ||||

| >3.50 mm | 3.82 (2.19–6.66) | <0.001 | 4.32 (2.31–8.09) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Ulceration: present vs. absent | 1.97 (1.40–2.77) | <0.001 | 2.17 (1.55–3.05) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Site of melanoma | ||||

|

| ||||

| Arm or leg† | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| Head or neck | 0.81 (0.44–1.48) | 0.49 | 1.60 (0.96–2.66) | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| Trunk | 1.26 (0.89–1.77) | 0.19 | 1.05 (0.74–1.49) | 0.80 |

|

| ||||

| No. of positive sentinel nodes | ||||

|

| ||||

| 1† | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

|

| ||||

| 2 | 1.08 (0.71–1.62) | 0.73 | 1.27 (0.87–1.84) | 0.21 |

|

| ||||

| ≥3 | 1.17 (0.61–2.24) | 0.64 | 2.01 (0.82–4.95) | 0.13 |

|

| ||||

| Nonsentinel nodes: positive vs. negative | 1.78 (1.19–2.67) | 0.005 | NA | |

Patients with positive findings on RT-PCR were excluded from this analysis. NA denotes not applicable.

This group served as the reference group.

Among patients who underwent immediate completion lymph-node dissection, nonsentinel-node metastases were detected on pathological assessment in 11.5%, and over time, with nodal recurrences in that group, the percentage of patients in whom nonsentinel-node metastases were detected increased to an actuarial rate of 17.9% at 3 years and 19.9% at 5 years (Fig. 3D). In the observation group, the percentage of patients in whom ultrasonographic or physical examination revealed involved nonsentinel nodes increased to 22.9% at 3 years and 26.1% at 5 years, exceeding the rate in the dissection group at both time points (P = 0.02 and P = 0.005, respectively).

ADVERSE EVENTS

Adverse events were more common among patients after completion lymph-node dissection than among patients in the observation group. At the most recent follow-up on April 30, 2016, a total of 24.1% of the patients in the dissection group and 6.3% of those in the observation group had had lymphedema (P<0.001). Among the patients who had lymphedema, this condition was mild in 64%, moderate in 33%, and severe in 3%.

DISCUSSION

The management of regional lymph nodes has long been controversial in the treatment of many solid tumors, particularly melanoma.16 The MSLT-I confirmed the staging value of sentinel-node biopsy and showed a therapeutic advantage of early treatment of nodal metastases among patients with intermediate-thickness melanoma.3 The findings of that trial provided support for the use of sentinel-node biopsy, which is now recommended in the guidelines of most national and professional organizations for the treatment of melanoma.4–7

However, in patients with sentinel-node metastases, the value of completion lymph-node dissection remains controversial. Since most such patients have all nodal metastases removed by means of the sentinel-node biopsy procedure, they cannot derive additional therapeutic value from completion lymph-node dissection. Even microscopic nonsentinel-node metastases portend a markedly worse prognosis, similar to that of patients with bulky, clinically diagnosed metastases,13,14 than the prognosis in patients with metastases that are limited to the sentinel lymph nodes. Patients with nonsentinel-node metastasis may be unlikely to benefit from early dissection. Finally, completion lymph-node dissection is associated with higher morbidity than sentinel-node biopsy alone, so an appraisal of the value of the procedure is important.

Previous data regarding this clinical question have been inconclusive. Retrospective series have produced varied results and are subject to a considerable risk of selection bias.9–11 The findings of one prospective study were similar to those in our trial, but its size (483 patients underwent randomization) and most recent follow-up left enough statistical uncertainty to preclude definitive conclusions.12 MSLT-II, in which 1939 patients underwent randomization with a median follow-up of 43 months, provided sufficient data to resolve the central question: no significant survival benefit was imparted by immediate completion lymph-node dissection among patients with sentinel-node metastases. However, completion lymph-node dissection did provide other potential value for patients with melanoma, including improved staging and an increased rate of regional disease control.

Most patients in the trial population had a low-volume nodal tumor burden. Indeed, some patients had only molecular indications of melanoma in the sentinel node, determined by means of RT-PCR. Those patients had outcomes that were not as poor as those in retrospective studies using the same assay.15,17 However, any variance from pretrial event-rate estimates is unlikely to have affected the overall result, since the RT-PCR–positive group constituted only 12% of the randomized study population. Furthermore, the number of patients with pathologically detected metastases actually exceeded the number in the statistical plan. Patients with a larger sentinel-node tumor burden are more likely than patients with a smaller burden to have nonsentinel-node metastases, and the small number of patients with a larger sentinel-node tumor burden in this trial limits statistical confidence for those patients specifically. It may be possible to use an estimation of the risk of nonsentinel-node metastases based on sentinel-node tumor burden and primary tumor characteristics to help identify patients who may benefit from completion lymph-node dissection.18–20 However, a subgroup evaluation of patients with a greater disease burden (maximal tumor diameter >1 mm) did not indicate that a benefit from completion lymph-node dissection was more likely in high-risk groups than in low-risk groups.

The current trial confirms that the pathologic status of nonsentinel nodes has independent prognostic value, whereas the number of involved sentinel nodes was not significantly related to melanoma-specific survival. Although this finding is somewhat counterintuitive, it echoes retrospective data from multiple institutions.13,14 This confirmation in a prospective trial of the large effect of nonsentinel node status on prognosis reaffirms its staging value. A lack of this information may impede the most appropriate risk stratification and selection of adjuvant therapy for patients who do not undergo completion lymph-node dissection.

Immediate completion lymph-node dissection reduced the rate of regional nodal recurrence by nearly 70%, leading to a small but significant decrease in the overall risk of recurrence. Since no significant difference between the groups was noted in the primary end point, differences with respect to the secondary end points must be interpreted with caution. A nonsignificant difference in distant metastasis–free survival was noted at late time points, but as of this writing, events at those time points have been few, and additional follow-up is necessary. Our trial was unable to determine the safety of avoiding completion lymph-node dissection in patients who are unable to undergo frequent follow-up evaluations or in patients who receive treatment at institutions that are not able to perform nodal ultrasonography.

The advantages of immediate completion lymph-node dissection are tempered by the complications of the procedure. As of this writing, lymphedema has been observed in 24% of the patients in the dissection group and 6% of the patients in the observation group. As expected, there were significantly more complications among patients who underwent completion lymph-node dissection than among those who did not, although the adverse events associated with the surgical procedure were often transient. Although a complete assessment and comparison of lymphedema with other complications would require additional follow-up, we think that the decreased overall number of dissections among patients in the observation group will translate into decreased complications.

The lack of a survival advantage associated with immediate completion lymph-node dissection in this trial contrasts with the results of the MSLT-I. In that trial, patients with nodal disease and intermediate-thickness melanomas had better outcomes with immediate surgery than with delayed surgery. The lack of a survival benefit with completion lymph-node dissection in patients in MSLT-II suggests that any increase in survival with early surgery occurred among patients with disease that was limited to the sentinel node. Patients with nonsentinel-node metastases may still undergo salvage treatment with completion lymph-node dissection, but the timing of that intervention does not appear to be critical.

Early completion lymph-node dissection did not increase survival in the MSLT-II population. It is possible that this was due to dilution of a therapeutic effect, since approximately three quarters of the population did not have melanoma in nonsentinel nodes. A comparison of results in patients with nonsentinel-node metastases in this trial, similar to the latent subgroup analysis in MSLT-I, might address this possibility, but it would be difficult to accomplish.21 First, in this population with a low disease burden and with the most recent follow-up, additional nodal recurrences are expected. Second, even at the most recent follow-up, an imbalance in the observed proportion of patients with non-sentinel node–positive disease was noted, with an excess in the observation group. This may be due to small nonsentinel-node metastases that were not detected on standard pathological examination. Intensive evaluation of nonsentinel nodes with the use of immunohistochemical tests indicates that the frequency of these occult metastases in completion lymph-node dissection specimens is very similar to that of excess nodal recurrences (8 to 10%).18

Overall, some value may be derived from immediate completion lymph-node dissection with regard to staging and an increased rate of regional disease control. However, this value comes at the cost of increased complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (CA189163 and CA29605, to Dr. Faries) from the National Cancer Institute and by funding from the Borstein Family Foundation, the Amyx Foundation, the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the John Wayne Cancer Institute Auxiliary.

Dr. Faries reports receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Amgen, and Immune Design; Dr. Thompson, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Provectus Biopharmaceuticals; Dr. Dummer, receiving consulting fees from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Takeda, Pierre Fabre, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Amgen; Dr. Wright, receiving grant support from Roche; Dr. Hsueh, receiving lecture fees from Amgen and Castle Biosciences; Dr. MacKenzie-Ross, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Amgen; Dr. Johnson, receiving grant support from Incyte and fees for serving on an advisory board from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Genoptix; Dr. Terheyden, receiving honoraria and travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche and honoraria from Merck and Novartis; Dr. Gershenwald, receiving fees for serving on an advisory board from Merck and Castle Biosciences; Dr. McMasters, receiving fees for serving on the board of directors from Provectus Biopharmaceuticals and fees for serving on an advisory board and uncompensated equity interest from Elucida Oncology; Dr. Barth, holding a pending patent on systems and methods for guiding tissue resection (patent no. US 14/919,411); and Dr. Hoon, holding an issued patent on detection of micrometastasis of melanoma and breast cancer in paraffin-embedded, tumor-draining lymph nodes by means of multimarker quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay (patent no. US 7910295). No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We thank Donald L. Morton, M.D., (deceased) who founded the MSLT Group and whose contributions not only to this trial but also to the care of patients with cancer cannot be overestimated.

APPENDIX

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Mark B. Faries, M.D., John F. Thompson, M.D., Alistair J. Cochran, M.D., Robert H. Andtbacka, M.D., Nicola Mozzillo, M.D., Jonathan S. Zager, M.D., Tiina Jahkola, M.D., Ph.D., Tawnya L. Bowles, M.D., Alessandro Testori, M.D., Peter D. Beitsch, M.D., Harald J. Hoekstra, M.D., Ph.D., Marc Moncrieff, M.D., Christian Ingvar, M.D., Ph.D., Michel W.J.M. Wouters, M.D., Ph.D., Michael S. Sabel, M.D., Edward A. Levine, M.D., Doreen Agnese, M.D., Michael Henderson, M.D., Reinhard Dummer, M.D., Carlo R. Rossi, M.D., Rogerio I. Neves, M.D., Steven D. Trocha, M.D., Frances Wright, M.D., David R. Byrd, M.D., Maurice Matter, M.D., Eddy Hsueh, M.D., Alastair MacKenzie-Ross, M.D., Douglas B. Johnson, M.D., Patrick Terheyden, M.D., Adam C. Berger, M.D., Tara L. Huston, M.D., Jeffrey D. Wayne, M.D., B. Mark Smithers, M.B., B.S., Heather B. Neuman, M.D., Schlomo Schneebaum, M.D., Jeffrey E. Gershenwald, M.D., Charlotte E. Ariyan, M.D., Ph.D., Darius C. Desai, M.D., Lisa Jacobs, M.D., Kelly M. McMasters, M.D., Ph.D., Anja Gesierich, M.D., Peter Hersey, M.D., Ph.D., Steven D. Bines, M.D., John M. Kane, M.D., Richard J. Barth, M.D., Gregory McKinnon, M.D., Jeffrey M. Farma, M.D., Erwin Schultz, M.D., Sergi Vidal-Sicart, M.D., Ph.D., Richard A. Hoefer, D.O., James M. Lewis, M.D., Randall Scheri, M.D., Mark C. Kelley, M.D., Omgo E. Nieweg, M.D., Ph.D., R. Dirk Noyes, M.D., Dave S.B. Hoon, Ph.D., He-Jing Wang, M.D., David A. Elashoff, Ph.D., and Robert M. Elashoff, Ph.D.

From the John Wayne Cancer Institute at Saint John’s Health Center, Santa Monica (M.B.F., D.S.B.H.), and the Departments of Pathology (A.J.C.), Biomathematics (H.-J.W., D.A.E., R.M.E.), and Medicine (D.A.E.), University of California, Los Angeles — both in California; Melanoma Institute Australia and the University of Sydney, Sydney (J.F.T., O.E.N.), Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC (M.H.), Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, QLD (B.M.S.), and Newcastle Melanoma Unit, Waratah, NSW (P.H.) — all in Australia; Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City (R.H.A., R.D.N.), and Intermountain Healthcare Cancer Services–Intermountain Medical Center, Murray (T.L.B.) — both in Utah; Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori Napoli, Naples (N.M.), Istituto Europeo di Oncologia, Milan (A.T.), and Istituto Oncologico Veneto–University of Padua, Padua (C.R.R.) — all in Italy; H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL (J.S.Z.); Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki (T.J.); Dallas Surgical Group, Dallas (P.D.B.); Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen (H.J.H.), and Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam (M.W.J.M.W.) — both in the Netherlands; Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, Norwich (M. Moncrieff), and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London (A.M.-R.) — both in the United Kingdom; Swedish Melanoma Study Group–University Hospital Lund, Lund, Sweden (C.I.); University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (M.S.S.); Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem (E.A.L.), and Duke University, Durham (R.S.) — both in North Carolina; Ohio State University, Columbus (D.A.); University of Zurich, Zurich (R.D.), and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne (M. Matter) — both in Switzerland; Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute, Hershey (R.I.N.), Thomas Jefferson University (A.C.B.) and Fox Chase Cancer Center (J.M.F.), Philadelphia, and St. Luke’s University Health Network, Bethlehem (D.C.D.) — all in Pennsylvania; Greenville Health System Cancer Center, Greenville, SC (S.D.T.); Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto (F.W.), and Tom Baker Cancer Centre, Calgary, AB (G.M.) — both in Canada; University of Washington, Seattle (D.R.B.); Saint Louis University, St. Louis (E.H.); Vanderbilt University (D.B.J., M.C.K.), Nashville, and University of Tennessee, Knoxville (J.M.L.) — both in Tennessee; University Hospital Schleswig–Holstein–Campus Lübeck, Lübeck (P.T.), University Hospital of Würzburg, Würzburg (A.G.), and City Hospital of Nürnberg, Nuremberg (E.S.) — all in Germany; SUNY at Stony Brook Hospital Medical Center, Stony Brook (T.L.H.), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York (C.E.A.), and Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo (J.M.K.) — all in New York; Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine (J.D.W.) and Rush University Medical Center (S.D.B.), Chicago; University of Wisconsin, Madison (H.B.N.); Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel (S.S.); M.D. Anderson Medical Center, Houston (J.E.G.); Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore (L.J.); University of Louisville, Louisville, KY (K.M.M.); Dartmouth–Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH (R.J.B.); Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Barcelona (S.V.-S.); and Sentara CarePlex Hospital, Hampton, VA (R.A.H.).

Footnotes

The authors’ full names, academic degrees, and affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Morton DL, Cochran AJ, Thompson JF, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for early-stage melanoma: accuracy and morbidity in MSLT-I, an international multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242:302–11. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000181092.50141.fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2912–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Cancer Network Melanoma Guidelines Revision Working Party. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Cancer Council Australia/Australian Cancer Network; Oct, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline — update 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2375–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coit DG, Thompson JA, Algazi A, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: melanoma, version 3. 2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:945–58. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran A, et al. The impact on morbidity and length of stay of early versus delayed complete lymphadenectomy in melanoma: results of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (I) Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3324–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DY, Lau BJ, Huynh KT, et al. Impact of completion lymph node dissection on patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bamboat ZM, Konstantinidis IT, Kuk D, Ariyan CE, Brady MS, Coit DG. Observation after a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3117–23. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3758-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SL, Morton DL, Thompson JF, et al. Melanoma patients with positive sentinel nodes who did not undergo completion lymphadenectomy: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:809–16. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:757–67. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reintgen M, Murray L, Akman K, et al. Evidence for a better nodal staging system for melanoma: the clinical relevance of metastatic disease confined to the sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:668–74. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung AM, Morton DL, Ozao-Choy J, et al. Staging of regional lymph nodes in melanoma: a case for including nonsentinel lymph node positivity in the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:879–84. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeuchi H, Morton DL, Kuo C, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular upstaging of paraffin-embedded sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2671–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snow HM. Melanotic cancerous disease. Lancet. 1892;140:869–922. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMasters KM, Egger ME, Edwards MJ, et al. Final results of the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial: a multi-institutional prospective randomized phase III study evaluating the role of adjuvant high-dose interferon alfa-2b and completion lymph node dissection for patients staged by sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1079–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cochran AJ, Wen DR, Huang RR, Wang HJ, Elashoff R, Morton DL. Prediction of metastatic melanoma in nonsentinel nodes and clinical outcome based on the primary melanoma and the sentinel node. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:747–55. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starz H, Welzel J, Bertsch HP, Kretschmer L. Tumor penetrative depth considers both the size of sentinel lymph node metastases and their location in relation to the nodal capsule. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4843–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.6284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakera AH, Hesse B, Burak Z, et al. EANM-EORTC general recommendations for sentinel node diagnostics in melanoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1713–42. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altstein LL, Li G, Elashoff RM. A method to estimate treatment efficacy among latent subgroups of a randomized clinical trial. Stat Med. 2011;30:709–17. doi: 10.1002/sim.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.