Abstract

Transgender patients face a multitude of health disparities and often a lack of understanding by healthcare professionals. A survey was undertaken of internal medicine residents in a large urban academic training program to determine prior education, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge in providing care for transgender individuals in a primary care setting. Total N=67 respondents (52% of those eligible). A full 97% of residents believe transgender medical issues are relevant to their practice, but only 45% had prior education about the care of transgender patients. Less than one-third of respondents felt comfortable describing hormonal/surgical therapy options or referring to another physician to meet these patient needs. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia risk was underestimated for the trans woman population. Most medical residents did not feel up to date with screening guidelines. In contrast, most residents correctly identified higher rates of depression/suicidality in transgender individuals, as well as lower adherence to human papillomavirus screening recommendations for trans men.

Keywords: : health maintenance, medical education, primary care

Introduction

It is estimated that ∼0.6% of the U.S. population, or 1.4 million individuals, self-identify as transgender.1 These patients experience notable health disparities, including increased prevalence of high-risk sexual behavior,2 HIV infection,3 and gonorrhea/chlamydia infection in trans women,4 inadequate human papillomavirus (HPV) screening in trans men,5 and depression/suicidality.6 Delivering appropriate healthcare to this population can be challenging for many reasons, including lower rates of healthcare-seeking behavior due to perceived discrimination7,8 and discomfort among providers.3,8 Prior studies show that resident physicians are less comfortable taking a sexual history and managing sexual health issues in the LGBTQ patient population.9,10 We undertook a survey study of internal medicine residents at a large urban academic center to better understand their attitudes, prior education, comfort, and knowledge in the area of transgender primary care.

Methods

A survey was delivered during academic conference time to internal medicine residents during an outpatient rotation. The residents practice in combined faculty and resident outpatient internal medicine practice at a large urban academic center, providing comprehensive primary care to a medically complex and culturally and socioeconomically diverse population. This is not a dedicated LGBTQ practice and it is not known how many patients within the practice identify as transgender. Residents in the program are a geographically diverse group hailing from different parts of the United States and 18 different countries. Thirty-seven percent are women. Historically, ∼50% of residents in the program go on to pursue subspecialty fellowship.

Participation in the survey was voluntary, no identifying data were collected about respondents, and there was no penalty for opting out of the survey. The 16-question survey was designed to assess perceived importance of transgender health training, level of prior exposure to transgender health, comfort in providing primary care to transgender patients, and knowledge of specific medical issues for transgender patients; including sexually transmitted infections risk, mental health, cancer screening, and management of gender transition. The survey was institutional review board exempt as it was designed for educational assessment and curricular design, and no identifying data were collected about respondents.

Results

A total of 67 residents (52% of those eligible) completed the anonymous survey. The results are described below.

Attitudes

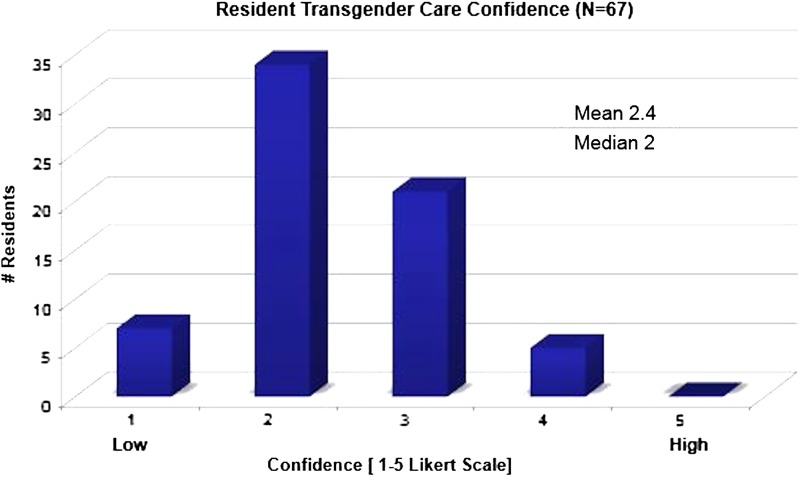

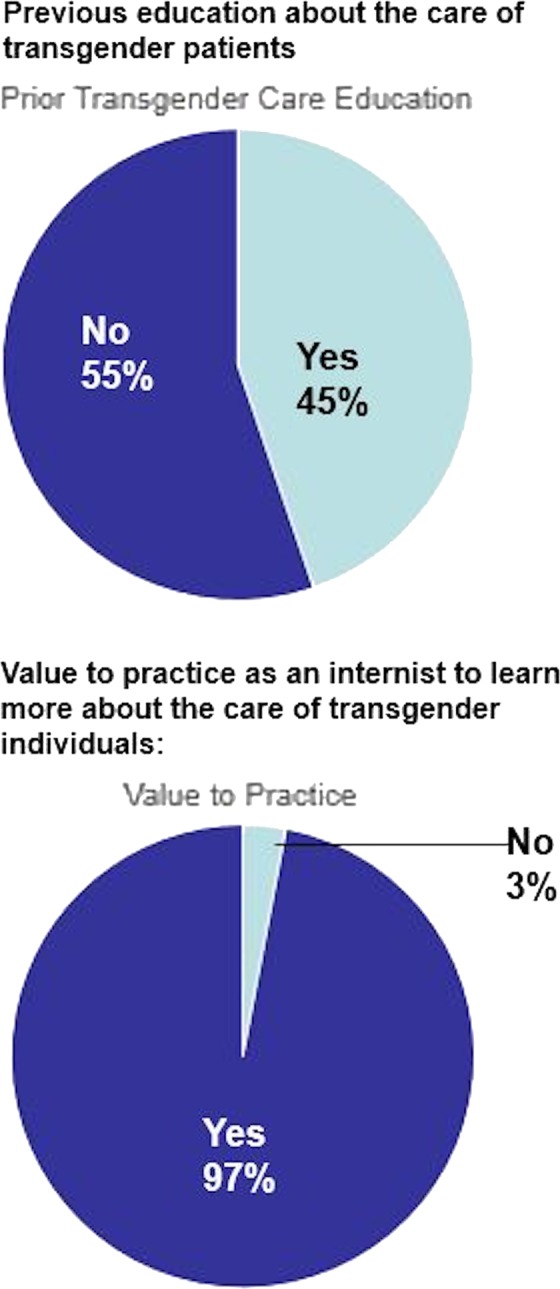

Nearly all (97%) of the respondents felt that understanding transgender medical care is valuable to their practice as internal medicine physicians.

Prior education

Only 45% had received any previous education in the area of transgender health (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Internal medicine resident prior education and attitudes, regarding transgender healthcare.

Comfort

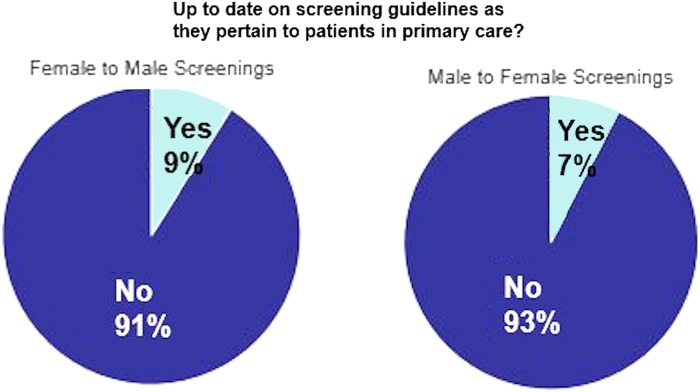

When asked to rate their confidence in providing medical care for a transgender patient on a 1–5 Likert scale (1=low confidence, 5=high confidence), the median response was 2, and average was 2.4 (Fig. 2). Two residents (3%) responded that they would feel uncomfortable treating a transgender patient for personal, moral, or religious reasons. In total, 9% of the respondents felt confident prescribing hormone replacement therapy, and 27% knew where to refer a patient for hormone therapy. Regarding gender-affirming surgery, 15% of residents felt they could adequately describe the process of female to male (transgender man, trans man) sexual reassignment, and 19% could describe the male to female (transgender woman, trans woman) sexual reassignment to their patients. Only 9% of residents felt they knew where to refer patients to a surgeon for gender-affirming sexual reassignment. Regarding primary care screenings 91% and 93% of residents did not feel up to date on screening guidelines for trans men and trans women, respectively (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Internal medicine resident confidence (1–5 Likert scale) in their ability to provide comprehensive care to a transgender patient.

FIG. 3.

Internal medicine residents who feel up to date on primary care screening guidelines for trans men (female to male), and trans women (male to female).

Knowledge

In assessing risk of HIV, 39% of respondents identified a higher incidence of HIV in the trans man population, and 52% of residents identified higher HIV incidence in the trans woman population. Approximately half of residents identified increased gonorrhea/chlamydia incidence in the trans woman population. Regarding HPV, 81% of residents identified that trans men are less likely to be up to date with HPV screening than their cis-gendered peers. Most residents identified that transgender patients experience higher rates of depression and increased suicidality with 95% and 92% of respondents identifying these risks, respectively.

Discussion

The results of this anonymous survey of internal medicine residents demonstrate that, overwhelmingly, the respondents felt it is valuable to their practice of internal medicine to understand the care of transgender patients. Only a small minority felt uncomfortable caring for transgender individuals due to personal, moral, or religious reasons. This recognition of and appreciation for transgender health issues may reflect some of the larger cultural and legal shifts currently ongoing toward greater transgender awareness and advocacy. In a resident population that overall values transgender health, there exists a need for further educational efforts to improve comfort and knowledge in the delivery of this care.

In our study sample, less than half of respondents had ever received prior training in the area of transgender health. Importantly, prior research demonstrates that increased education can improve physician attitudes and willingness to assist transgender patients11,12 and that greater knowledge about the LGBTQ population is associated with improved attitudes. Medical school and graduate medical training programs may offer a unique opportunity to provide this didactic and clinical experience in caring for individuals within the LGBTQ community. It has been shown that outpatient medical practices can be modeled to provide improved care to this high-risk population, but even in programs that do not have dedicated LGBTQ centers, didactic educational materials may provide important exposure and education.13–15

In our survey, residents overall did not feel particularly comfortable in their ability to provide comprehensive medical care for transgender individuals (median response of 2 and average response of 2.4 on a 5-point Likert scale). This discomfort is likely multifactorial, with causes, including lack of exposure to the transgender population, lack of formal education in transgender care, and uncertainty in guidelines pertaining to health maintenance screenings in the transgender population. Without a comprehensive knowledge base, providers may feel inadequate in providing care to a transgender patient, which can lend itself to a feeling of discomfort.

Interestingly, our results illustrate an uneven knowledge base about transgender health among surveyed medical residents. There were significant gaps in medical resident knowledge pertaining to HIV and gonorrhea/chlamydia prevalence, which have been reported to be higher than the general population.4,5 However, medical residents did recognize the risk of HPV in the trans male population. Medical residents were aware of the mental health issues with higher prevalence in the transgender population, including depression and suicidality. The awareness of mental health issues may be influenced by popular culture attention to transgender mental health disparities.

Overall, medical residents did not have knowledge of how to provide hormonal therapy or explanations of gender-affirming surgery, and they generally did not know where to refer patients for these services. This lack of knowledge may create a barrier to care for transgender patients seeking gender-affirming therapies.16 Understanding screening recommendations is likely complicated by the fact that after pursuing gender-affirming medical or surgical therapy, screening recommendations can change from standard guidelines.17 To fully care for a transgender patient, the primary care doctor should be knowledgeable of medical issues, understand social challenges, have resources for care coordination, including hormonal and surgical gender-affirming therapy, and provide counsel regarding routine screening tests.18

Recent curriculum implementation for medical students and pediatric interns was proven successful in bolstering trainee's perceived knowledge of medical and psychosocial issues faced by transgender youth.19 A similar structured curriculum could be adapted for internal medicine trainees, as there are both self-perceived and actual gaps in knowledge of medical issues for this patient population.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, although over half of eligible respondents completed the survey, there were still a relatively few respondents (N=67). Moreover, since completion of the survey was voluntary rather than compulsory, there may exist an element of response bias. In an attempt to increase survey completion rates, the survey was designed to fit on one page. However, this did not leave room to query other important points about transgender primary care, such as mammography recommendations for trans women taking feminizing hormone therapy, in adequate detail.

Conclusion

Few data exist in the area of internal medicine graduate medical education pertaining to providing comprehensive primary care to the transgender population. Our study of internal medicine residents in a large academic urban institution suggests residents believe learning how to provide comprehensive care for transgender patients is valuable for their practice, despite the majority lacking a robust prior training in this area and demonstrating confidence and knowledge deficits. There have not been formal didactic sessions dedicated to heath care for the LGBTQ population for medical residents at this institution, despite the fact that education has been shown to improve caregiver attitudes and comfort. Medical residents demonstrated an uneven knowledge base in transgender health. It is important to educate medical trainees about transgender health issues, as well as provide information about how to refer patients for hormonal and surgical gender-affirming therapies. Further research is warranted to investigate the best way to provide didactic and clinical training to internal medicine residents regarding the care of transgender patients. We propose that those academic internal medicine programs without dedicated LGBTQ centers incorporate dedicated didactics and accessible print and electronic resources specifically designed to provide education in the unique aspects of transgender healthcare, with the goal of improving provider attitudes, comfort, and knowledge in caring for this vulnerable population.

Abbreviation Used

- HPV

human papillomavirus

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Flores A, Herman JL, Gates GJ, et al. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leon SR, Segura ER, Konda KA, et al. High prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in anal and pharyngeal sites among a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in Lima, Peru. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e008245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peitzmeier SM, Khullar K, Reisner SL, Potter J. Pap test use is lower among female-to-male patients than non-transgender women. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:808–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GR, Jones KT. Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the veterans health administration: a case–control study. LGBT Health. 2015;3:122–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socías M, Marshall B, Arístegui I, et al. Factors associated with healthcare avoidance among transgender women in Argentina. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:8–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes V, Blondeau W, Bing-You RG. Assessment of medical student and resident/fellow knowledge, comfort, and training with sexual history taking in LGBTQ patients. Fam Med. 2015;47:383–387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitts RL. Barriers to optimal care between physicians and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescent patients. J Homosex. 2010;57:730–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas DD, Safer JD. A simple intervention raised resident-physician willingness to assist transgender patients seeking hormone therapy. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1134–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safer JD, Pearce EN. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banwari G, Mistry K, Soni A, et al. Medical students and interns' knowledge about and attitude towards homosexuality. J Postgrad Med. 2015;61:9–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redfern JS, Sinclair B. Improving health care encounters and communication with transgender patients. J Commun Healthc. 2014;7:25–40 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender–competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1114–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:713–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Department of Family and Community Medicine CSF. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People; 2nd Edition. Deutsch MB. (ed). 2016. Available at: www.transhealth.ucsf.edu/guidelines (accessed June28, 2017)

- 18.Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, Katz M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:9151–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vance SR, Jr, Deutsch MB, Rosenthal SM, Buckelew SM. Enhancing pediatric trainees' and students' knowledge in providing care to transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

Cite this article as: Johnston CD, Shearer LS (2017) Internal medicine resident attitudes, prior education, comfort, and knowledge regarding delivering comprehensive primary care to transgender patients, Transgender Health 2:1, 91–95, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0007.