Abstract

Releasing sterols to the extracellular milieu is an important part of sterol homeostasis in cells and in the body. ATP-binding cassette transporter Al (ABCA1) plays an essential role in cellular phospholipid and sterol release to lipid-free or lipid-poor apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), the major apolipoprotein in high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and constitutes the first step in the formation of nascent HDL. Loss-of-function mutations in the ABCA1 gene lead to a rare disease known as Tangier disease that causes severe deficiency in plasma HDL level. Mammalian cells receive exogenous cholesterol mainly from low-density lipoprotein. In addition, they synthesize cholesterol endogenously, as well as multiple precursor sterols that are sterol intermediates en route to be converted to cholesterol. HDL contains phospholipids, cholesterol, and precursor sterols, and ABCA1 has an ability to release phospholipids and various sterol molecules. Recent studies using model cell lines showed that ABCA1 prefers to use sterols newly synthesized endogenously as its preferred substrate, rather than cholesterol derived from LDL or cholesterol being recycled within the cells. Here, we describe several methods at the cell culture level to monitor ABCA1-dependent release of sterol molecules to apoA-I present at the cell exterior. Sterol release can be assessed by using a simple colorimetric enzymatic assay, and/or by monitoring the radioactivities of radiolabeled cholesterol incorporated into the cells, and/or of sterols biosynthesized from radioactive acetate, and/or by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of various sterols present in medium and in cells. We also discuss the pros and cons of these methods. Together, these methods allow researchers to detect the release not only of cholesterol but also of other sterols present in minor quantities.

Keywords: ABCA1, ApoA-I, Cholesterol, GC-MS, Lanosterol, HDL, Thin-layer chromatography

1 Introduction

Sterol is an essential lipid for the growth and maintenance of all eukaryotic cells. In mammalian cells, various elaborate regulatory mechanisms operate cooperatively to assure the ample supply of cholesterol, and to prevent the toxic accumulation of cholesterol in membranes [1, 2]. Within a single cell type, the release of cellular cholesterol to the extracellular milieu constitutes a critical step in optimizing cellular cholesterol level. Several ATP-binding cassette transporters including ABCA1, ABCG1, and ABCG4 all have the ability to release cholesterol from cells [3, 4]. ABCA1 plays a unique role in this step, being required for apolipoprotein-mediated cholesterol and phospholipid release, which generates nascent HDL particles [5, 6]. Loss-of-function mutations in the ABCA1 gene causes severe HDL deficiency, known as Tangier disease [7–9]. Patients with this disease display a higher risk for premature cardiovascular heart disease.

Mammalian cells acquire cholesterol from uptake of extracellular lipoproteins including low-density lipoprotein (LDL) [2]. In addition, almost all cells in the body synthesize cholesterol endog-enously. The late stage of cholesterol biosynthesis occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and involves the biosynthesis of a series of intermediate sterols (hereafter referred to as precursor sterols) as the cholesterol precursors (Fig. 1). These precursor sterols, with lanosterol being the first biosynthesized sterol, have structures similar but distinct from that of cholesterol; some of them display distinct roles from those of cholesterol. When their contents exceed certain threshold value, the precursor sterols are also toxic to cells [10]. For example, in humans, genetic defects in the conversion of precursor sterols to cholesterol are known to cause several malformation syndromes [11]. At the cell culture level, early results showed that certain precursor sterols including lanosterol, are transported to the plasma membrane (PM) shortly after their synthesis at the ER [12–15]. After arriving at the PM, cholesterol and various precursor sterol molecules immediately become available for ABCA1-dependent sterol release [16]. Alternatively, they are rapidly transported back to the ER for the conversion to cholesterol [15]. Our recent study [16] showed that ABCA1 prefers to use sterols newly synthesized endogenously, not cholesterol derived from LDL, or cholesterol being recycled within the cells, as its preferred substrates. HDLs are known to contain small but significant amounts of precursor sterols in addition to cholesterol [17]. Together, these studies suggest that ABCA1 mediates the release of phospholipids and not only cholesterol but also other structurally different sterols to apoA-I to generate nascent HDL. In addition to its well-known function of mediating the release of phospholipids and sterols to apoA-I present in the extracellular milieu, we have recently shown that ABCA1 also participates in retrograde sterol movement; lack of ABCA1 impairs sterol internalization from the PM and leads to a defect in sterol sensing at the ER [18].

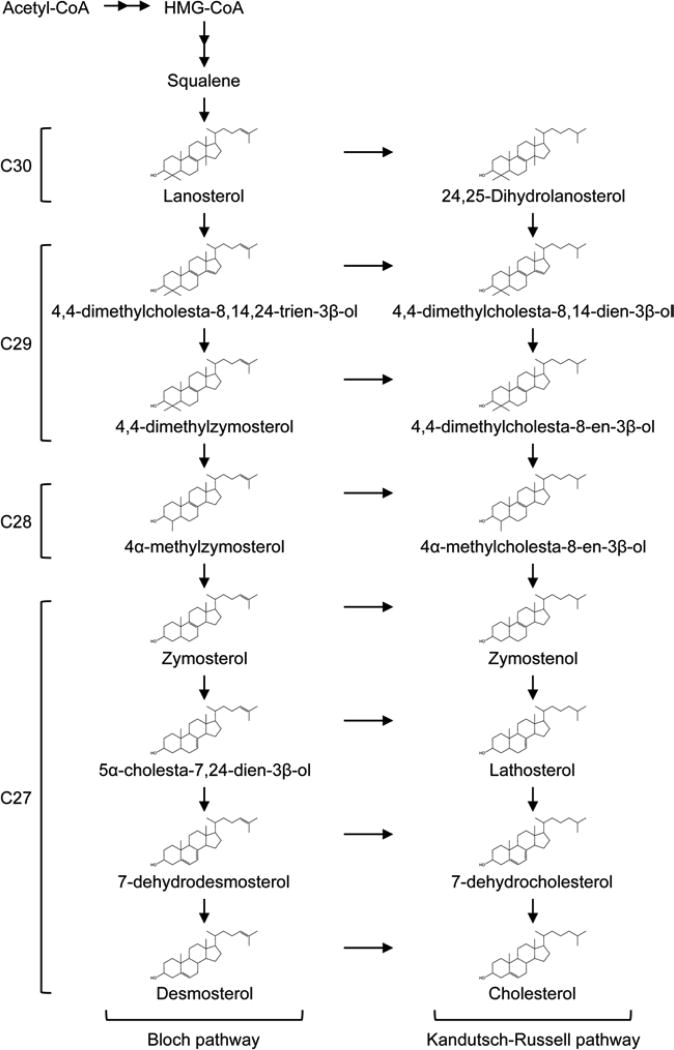

Fig. 1.

Cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. Cholesterol biosynthesis proceeds through either the Bloch pathway or the Kandutsch-Russell pathway. The side-chain double bond at C24 position is reduced by the 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase DHCR24. The substrate for this enzyme may vary in a tissue/cell type-specific manner. The total number of carbons in each sterol is shown on the left

In this chapter, we describe several methods used to monitor ABCA1-dependent sterol release. The first method is to measure cholesterol released into apoA-I by using a colorimetric enzyme assay. This method is based on the generation of H2O2 and cholestenone from cholesterol by the enzyme cholesterol oxidase. The second method is to feed cells with radiolabeled cholesterol and monitor the release of labeled cholesterol from cells. Third, we describe a method that uses radiolabeled acetate (a biosynthetic precursor of sterols) to produce radiolabel sterols endogenously, and uses thin layer chromatography (TLC) to separate the radiolabeled sterols. This TLC method allows one to detect not only cholesterol but also precursor sterols with one or two methyl group(s) located at the steroid ring A. Finally, we describe a method to identify sterol molecules by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). We also discuss the pros and cons of these methods.

2 Materials

2.1 Radioisotopes, Sterols, and Other Reagents

[3H]-cholesterol and [3H]-acetate are obtained commercially. [14C]-cholesterol or [14C]-acetate can be used instead.

Sterol standards for TLC and GC-MS: Epicoprostanol, cholesterol, lathosterol, desmosterol, zymosterol, and lanosterol, which are commercially available, are dissolved in chloroform at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. The stock solutions can be stored at −20 °C.

Sigma-Sil-A can be obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

The BCA protein assay is commercially available.

2.2 Solutions

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS): Dissolve 8 g of sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.2 g of potassium chloride (KC1), 1.15 g of disodium hydrogen phosphate (sodium phosphate, dibasic, anhydrous; Na2HPO4), and 0.2 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate (potassium phosphate, monobasic, anhydrous; KH2PO4) in 1 L of deionized/distilled water (ddH2O). After autoclaving, this solution is stable at room temperature.

10% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA): Dissolve 1 g of fatty acid-free BSA in 10 mL of sterile PBS. After filtration by using a 0.2 urn (or 0.45 urn) filter, the 10% stock can be stored at 4 °C for at least several months.

0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH): Dissolve 0.4 g of NaOH in 100 mL of ddH2O. This solution is stable at room temperature.

10 M potassium hydroxide (KOH): Dissolve 56.1 g of KOH in 100 mL of ddH2O. This solution is stable at room temperature

3% (w/v) sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3) saturated with chloroform: Dissolve 3 g of NaHCO3 in 100 mL of ddH2O, and add 10–20 mL of chloroform. After vigorously mixing, use the top aqueous phase. This solution is stable at room temperature for only a few days.

ddH2O saturated with chloroform: Add 10–20 mL of chloroform in 100 mL of ddH2O and mix vigorously. This solution is stable at room temperature.

2.3 Cell Culture Media

The following media are used for experiments. All media listed below contain 100 U/mL of penicillin and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin.

Medium A: appropriate medium containing 10% (or 7.5%) fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Medium B: appropriate medium containing 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA (unless specified otherwise; from the 10% stock).

Medium D: appropriate medium containing 5% delipidated FBS [19] or lipoprotein-deficient FBS (LPDS; commercially available) (see Note 1).

Medium F: appropriate medium without any supplements.

2.4 ApoA-l

Lipid-free apoA-I is isolated/purified from human plasma as described [20]. Bacterially expressed recombinant apoA-I can also be utilized in the ABCA1-dependent lipid release assay [21–23]. ApoA-I and recombinant apoA-I can be obtained from commercial sources. All apoA-I forms are essentially devoid of lipids. Lyophilized apoA-I should be solubilized to obtain a homogeneous solution by dissolving in PBS for 1 h at room temperature followed by warming at 37 °C for 1 h [20]. After filtration by using a 0.22 µm filter, determine the protein concentration by using a protein assay and adjust to the concentration of 1 mg/mL with sterile PBS. The solution should be kept at 4 °C and can be used for at least a few months.

2.5 Organic Solvents

All organic solvents used are of analytical grade.

Chloroform-methanol (2:1). Mix 200 mL of chloroform and 100 mL of methanol, and store in a dark glass bottle. The mixture is stable at room temperature.

Hexane-2-propanol (3:2): Mix 150 mL of hexane and 100 mL of 2-propanol, and store in a dark glass bottle. The mixture is stable at room temperature.

Ethanol-benzene-water (80:20:5): Mix 80 mL of ethanol, 20 mL of benzene, and 5 mL of ddH2O, and store in a dark glass bottle. The solution can be stored at room temperature for months.

Hexane-ether-acetic acid (260:80:3): Mix 45 mL of hexane, 20 mL of ether, and 0.75 mL of ddH2O. Prepare this mixture just before the TLC analysis.

Methylene chloride-ethyl acetate (97:3): Mix 97 mL of methylene chloride and 3 mL of ethyl acetate. Prepare this mixture just before the TLC analysis.

2.6 Colorimetric Enzymatic Cholesterol Assay Kits

Determinar L FC (available from Kyowa Medex). Mix R-l and R-2 reagents at the ratio of 3:1. Prepare mixture just before the assay (see Note 2).

An alternate kit that can be used is the Free Cholesterol E (available from Wako). Reconstitute appropriate amounts of the lyophilized powder in appropriate volume of buffer provided in the kit. Reconstitute just before the assay (see Note 3).

Cholesterol standard: The Cholesterol stock solution can be prepared in chloroform as described in Subheading 2.1. Free Cholesterol E (Wako) provides a 2 mg/mL cholesterol stock solution.

Cholesterol esterase (if total amount of cholesteryl esters is also required): Dissolve in PBS at the final concentration of 10 U/mL. This solution can be stored at −20 °C.

2.7 Equipment

Evaporator with heater connected to nitrogen gas system.

Microplate reader with appropriate filters.

Channeled 20 cm × 20 cm thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Silica Gel 60 Å, 250 µm layer thickness) can be obtained from Analtech.

TLC developing tank.

Iodine TLC tank to visualize lipids. Add iodine to the tank for developing.

80 °C oven.

GC-MS equipment; for example in our lab we use a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph connected to a Shimadzu QP5000 mass spectrometer and equipped with an XTI-5 (30 m × 25 µm × 0.25 mm) capillary column

3 Methods

Typically, seed cells into a 6-well plate and grow in Medium A essentially to a confluent stage at 37 °C with 100% humidity and 5% CO2. Lipid extraction and analysis are performed at room temperature unless specified otherwise (see Notes 4 and 5).

3.1 Monitoring Cholesterol Release by Using Colorimetric Enzymatic Assay (See Note 6)

Seed cells into 6-well plates and grown to confuency in Medium A in an incubator with 100% humidity and 5% CO2. Typically, cells are seeded at a density of 2–3 × 105 cells/well, and grown for 2–3 days (depending on cell lines/types) in Medium A. For cells that express low levels of ABCA1 (such as human fibro-blasts and mouse embryonic fibroblasts), ABCA1 expression can be induced transcriptionally by incubating cells overnight with a ligand for liver X receptor (LXR) and/or for retinoid X receptor (RXR.) (see Note 7).

Wash cells with PBS or with Medium F twice to remove FBS.

Incubate cells without or with apoA-I (5–10 µg/mL, 1 mL/well) in Medium B for 16–24 h at 37 °C in an incubator with 100% humidity and 5% CO2 (see Notes 8–11).

Collect medium (~1 mL) into a 1.5 mL tube. Wash cells with PBS twice and let them dry.

Spin medium at 10,0000 × g for 5 min to precipitate floating cells and cell debris.

Transfer 0.9 mL of supernatant to a glass tube.

Add 4 vol (3.6 mL) of chloroform-methanol (2:1) into the glass tube and vortex vigorously.

Wrap the glass tube with aluminum foil and leave at 4 °C overnight.

Vortex again and spin the glass tube at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Suck off the aqueous phase.

Add 1 mL of ddH2O and vortex (see Note 12).

Spin the glass tube again at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Suck off the aqueous phase.

Blow-dry the organic phase under nitrogen gas at 40–50 °C using a heat block (or a water bath).

Transfer extracted lipids into a well of 96-well plate with 2 × 100 µL of chloroform-methanol (2:1) to solubilize the dried lipid samples. Load onto a single well per sample (see Note 13).

Lipids present in the cells dried in the tissue culture wells (see step 4) can be extracted as follows: Add 1 mL of hexane-2-propanol (3:2) to a well, place for 1 h at room temperature, and transfer to a glass tube.

Extract cell lipids again by adding 1 mL of hexane-2-propanol (3:2) to a well, place for 30 min at room temperature, and transfer to a glass tube to combine with the first extract.

Blow-dry as describe above (see step 14).

Add 400 µL of chloroform-methanol (2:1) to a tube, vortex, and transfer a quarter (100 µL) of the extract (cell lipids) to a well of a 96-well plate.

Blow-dry the organic solvent in a 96-well plate using a hair dryer or under nitrogen gas.

Add the cholesterol standard (0–20 µg typically 20,10, 5,2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.3125, 0 µg of cholesterol) into separate wells (see Notes 14 and 15).

Add 20 µL of 2-propanol into each well (both samples and standards) to dissolve lipids.

Add 150 µL of reaction mixture into each well and place the plate at 37 °C for 60 min.

Measure absorbance at 550–600 nm (optimal absorbance is 555 nm for Kyowa-Medics Kit, or at 600 nm for Wako kit; reference filter of 700 nm), and calculate cholesterol contents based on the standard curve. To obtain the calculated cholesterol contents in a sample, divide the values by 0.9 for medium extracts, or multiply the values by 4 for cell extracts.

Add 1 mL of 0.1 M NaOH into a well and place at 4 °C overnight to extract cell protein. This can be done after the cellular lipids are extracted. After cellular lipid extraction, the lipid free cell proteins remain in the well and can be measured by BCA protein assay after solubilization by using 0.1 M NaOH.

Normalize cholesterol content in the medium by using cell protein or cell cholesterol as the denominator (see Notes 16 and 17).

3.2 Monitoring the Release of Radiolabeled Cholesterol Added Exogenously

Seed and grow cells as above (see step 1 of Subheading 3.1).

Wash cells with PBS or Medium F twice.

Incubate cells with [3H]-cholesterol (without adding nonradioactive cholesterol as carrier; 0.1 µCi/mL, 1 mL/well) in Medium A overnight (Fig. 2a, Condition IV).

After washing cells with PBS or Medium F twice (to remove unincorporated labeled cholesterol), incubate cells in Medium A to equilibrate [3H]-cholesterol in cells.

After washing cells with PBS or Medium F twice, incubate cells without or with apoA-I in Medium B for up to 24 h (see also Subheading 3.1).

Collect the medium (~1 mL) into a 1.5 mL tube. Wash cells with PBS twice and let them dry.

Spin medium at 10,0000 × g for 5 min to precipitate floating cells and cell debris.

Transfer 0.9 mL of supernatant to a glass tube.

Add 4 volumes (3.6 mL) of chloroform-methanol (2:1) into the glass tube, and vortex vigorously.

Wrap the glass tube with aluminum foil and leave at 4 °C overnight.

Vortex again, and spin the glass tube at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Suck off the aqueous phase.

Blow-dry the organic phase under nitrogen gas at 40–50 °C using a heat block (or a water bath).

For cellular [3H]-cholesterol analysis, extract cellular lipids as described above (see steps 16 and 17 of Subheading 3.1).

The extracted lipids (both from medium and cells) can directly be subjected to scintillation counting to determine radioactivity of [3H]-cholesterol in medium and cells. For more detailed analysis, the extracted lipids are run on TLC with a solvent system of hexane-ether-acetic acid (260:80:3), which separates cholesterol and cholesteryl ester from other lipids. Cholesterol and cholesteryl ester fractions are scraped and their radioactivities are counted by a liquid scintillation counter.

Calculate % release of [3H]-cholesterol by the following equation: counts in medium/(counts in medium + cell) × 100.

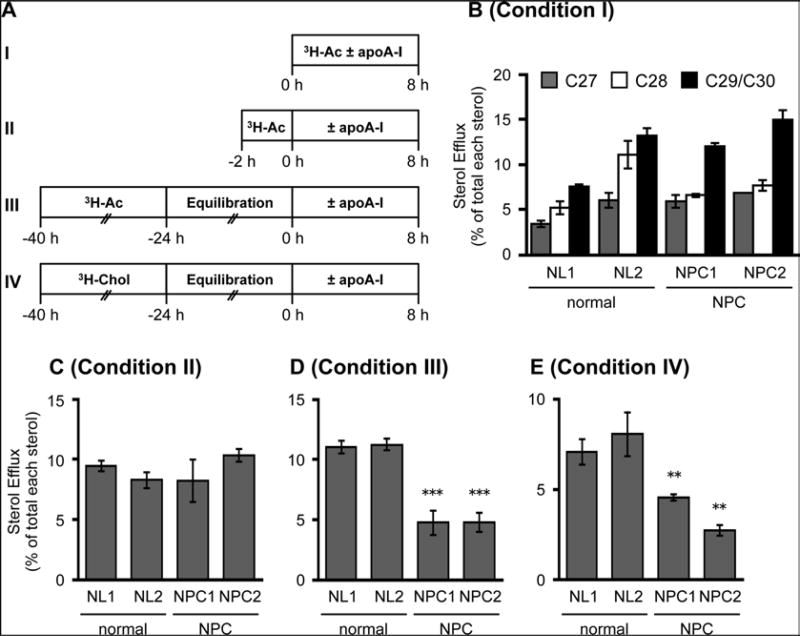

Fig. 2.

Monitoring the ABCA1-dependent release of radiolabeled endogenously synthesized sterols in normal and mutant NPC cells, (a) Procedures used in pulse-chase experiments using radiolabeled-acetate or radiolabeled-cholesterol (Assay I—IV) Cells were labeled with either [3H]-acetate (3H-Ac) or [3H]-cholesterol pH-Chol). (b–e) ABCA1-dependent release of labeled sterols in normal and NPC human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) evaluated under various conditions. HSFs from normal subjects (NL1 and NL2), and NPC patients (mutated in either NPC1 or NPC2 gene) were seeded in 6-well plates and grown in medium A to almost confluency. Cells were then subjected to the assay I, II, III, or IV by labeling cells with [3H]-acetate or [3H]-cholesterol as indicated below. For panel (b), cells pretreated with T0901317 (1 µg/mL) for 18 h were incubated with or without apoA-l (10 µg/mL) during the 8 h [3H]-acetate (40 µCi/mL) labeling period in the presence of T0901317. For panel (c), cells were labeled with [3H]-acetate (40 µCi/mL) for 2 h followed by washing off the label and incubation with or without apoA-l (10 µg/mL) in the presence of T0901317 for 8 h. For panels (d) and (e), cells were labeled with [3H]-acetate (20 µCi/mL) for 16 h in Medium D (D) or with [3H]-cholesterol (0.1 µCi/mL) in Medium A (e), followed by washing off the label and incubation with Medium D or Medium A for 24 h with T0901317 present. The cells were then incubated with or without apoA-l (10 µg/mL) for 8 h in the presence of T0901317. Sterols were analyzed by TLC. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. This research was originally published in J. Lipid Res. Yamauchi et al. (2016) ABCA1 -dependent sterol release: sterol molecule specificity and potential membrane domain for HDL iogenesis, J Lipid Res 57:77–88. © The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology [16]

3.3 Monitoring the Release of Radiolabeled Sterols Synthesized Endogenously

Seed and grow cells in 6-well plates as above (see step 1 of Subheading 3.1).

Wash cells twice with PBS or Medium F.

Incubate cells with [3H]-acetate (2O–40 µCi/mL, 1 mL/well) for 2–16 h in Medium B or in Medium D according to Fig. 2a (Condition I-III) (see Notc 18).

After washing cells twice with PBS or Medium F, incubate cells without or with apoA-I for up to 24 h (typically 6–24 h) in Medium B.

Collect medium (~1 mL) into 1.5 mL tube. Wash cells twice with PBS and let them dry.

Spin medium at 10,0000 × g for 5 min to precipitate floating cells and cell debris.

Transfer 0.9 mL of supernatant to a glass tube.

Add 4 vol (3.6 mL) of chloroform-methanol (2:1) into the glass tube and vortex vigorously.

Wrap the glass tube in aluminum foil and leave at 4 °C overnight.

Vortex again, and spin the glass tube at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Suck off the aqueous phase.

Cell lipids are extracted as above (see steps 16 and 17 of Subheding 3.1).

Blow-dry sample under nitrogen gas at 40–50 °C using a heat block (or a water bath).

Saponify lipids (extracted from medium and from cells respectively) as follows (steps 14–16): Add 3 mL of ethanol-benzene-water (80:20:5) and 0.33 mL of 10 M KOH (final concentration 1 M), and vortex.

Wrap the glass tube with aluminum foil.

Incubate the glass tube at 80 °C for 2 h in an oven.

Blow-dry under nitrogen gas at 40–50 °C using a heat block (or a water bath) to a final volume of~0.1 mL.

Add 1 mL of ddH2O and vortex.

Extract sterols by adding 3 mL of hexane and vortex.

Spin the glass tube at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Collect organic (upper) phase (containing sterols) and transfer to a glass tube (see Note 19).

Repeat steps 19–21 four times in total.

Blow-dry the organic phase to 3 mL.

Add 1 mL of 3% NaHCO3 saturated with chloroform and vortex.

Spin the glass tube at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Remove aqueous phase from the bottom using a glass Pasteur pipette.

Add 1 mL of water saturated with chloroform to the organic phase, and vortex.

Spin the glass tube at 1000 × g for 10 min at room temperature.

Remove aqueous phase from the bottom using a glass pasteur pipette.

Blow-dry the organic phase.

Add 40 µg of lanosterol and 60 µ g of cholesterol as internal markers and 100 µL of chloroform to each tube, then vortex.

Spot onto a channeled 20 cm × 20 cm TLC plate and run in a TLC tank with 30–50 mL of methylene chloride/ethyl acetate (97:3).

Visualize cholesterol and lanosterol by iodine and mark the bands by a pencil.

Scrape off the corresponding bands (cholesterol band, C27 sterols; lanosterol band, C29 and C30 sterols; space between cholesterol and lanosterol bands, C28 sterols) and put into a scintillation vial.

After adding 3 mL of scintillation cocktail, count the radioactivity with a liquid scintillation counter.

Calculate % release of [3H]-sterols as described earlier, using total (cell plus medium) [3H]-sterols as the denominators (see Subheading 3.2).

3.4 Monitoring Sterol Release by GC-MS

Seed cells into two 100-mm dishes.

Incubate cells with apoA-I in Medium B for 24–48 h (6 mL/dish).

Collect and centrifuge medium at 10,0000 × g for 5 min to precipitate floating cells and cell debris.

Extract lipids as described earlier using chloroform-methanol (2:1) (see Subheading 3.1).

Saponify lipids as described earlier (see Subheading 3.3, steps 14–18).

Extract non-saponified fraction (containing sterols) using hexane four times (see Subheading 3.3, steps 19–30).

Add 20 µg of epicoprostanol (as an internal standard) and 0.25 mL of Sigma-Sil-A to the tube and incubate at 60 °C for 30 min to achieve trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatization of the sterols.

Blow-dry under nitrogen gas at 40–50 °C.

Resuspend in 50 µL of chloroform and transfer to a fresh glass vial with screw cap.

Inject appropriate amounts (typically 1–2 µL) of derivatized sterols into a GC-MS (see Note 20).

Analyze the GC profile (Fig. 3) with MS spectra of each peak (see Note 21).

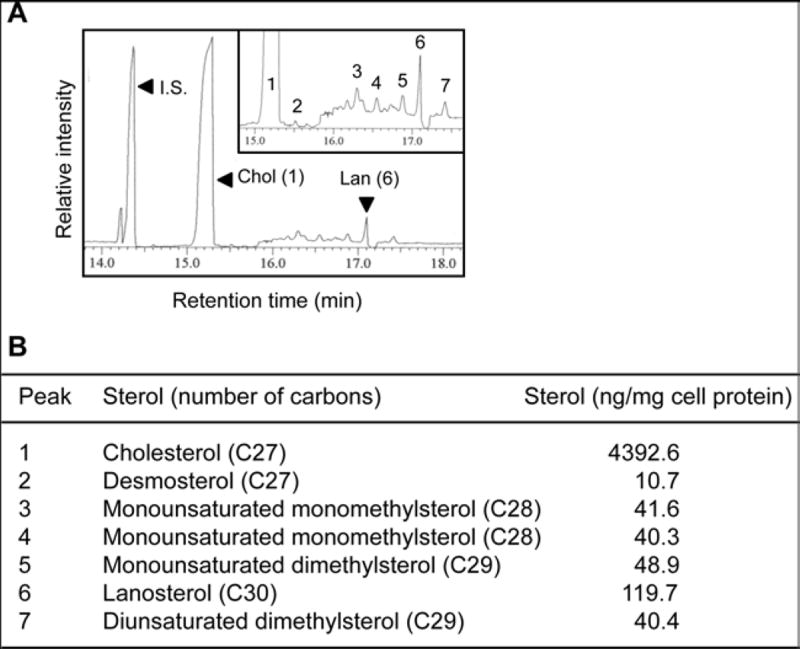

Fig. 3.

GC-MS analysis of ABCA1-dependent sterol release, (a) HEK293 cells stably expressing human ABCA1-GFP (HEK/hABCA1) grown as a monolayer at subconfluency in two 100 mm dishes in Medium D were incubated with apoA-l (5 µg/mL) for 48 h in Medium B. Lipids were extracted from the medium, saponified, and analyzed by GC-MS. The peaks of epicoprostanol (internal standard, I.S.), cholesterol (Chol, peak 1), and lanosterol (Lan, peak 6) are indicated by arrowhead. Other minor peaks (2–5 and 7) are shown in the inset. This research was originally published in J. Lipid Res. Yamauchi et al. (2016) ABCA1-dependent sterol release: sterol molecule specificity and potential membrane domain for HDL biogenesis. J Lipid Res 57:77–88. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology [16]. (b) Identification and quantification of sterols released to apoA-l. Based on the GC-MS profile shown above, the identity of each peak and contents of each sterol were determined. The results are reproduced from Yamauchi et al. [16] with modification

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Catherine C.Y. Chang at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Dr. Sumiko Abe-Dohmae at Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, who participated in developing and/or optimizing some of the methods described in this chapter. The authors' work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants (to Y.Y. and to S.Y.), by the CREST program from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (to Y.Y.), by MEXT-supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities (S1201007) and by NIH grant HL060306 (to T.Y.C. and C.C.Y.C).

Footnotes

The primary purpose to incubate cells in Medium D is to activate sterol regulatory element binding proteins and to upregulate sterol biosynthesis. Depending on cell types used, the concentration of delipidated FBS or LPDS may be reduced to 1 or 2%, but optimization is required.

Determinar L FC from Kyowa Medex is available only in certain Asian countries including Japan and China. Researchers who live in other countries can employ Free Cholesterol E (Wako).

Free Cholesterol E is supplied as lyophilized powder. If reconstituted all at once as described in the manufacture's instruction, the solution can be stored at 4 °C for up to 2 weeks only. To lengthen the usage time of the kit, we recommend that one measures a portion of the powder needed for a single experiment, and reconstitutes the powder in the buffer proportionally.

Not all cell lines express ABCA1. It is important to select correct cell lines/cell types to study ABCA1-dependent sterol release. With cells not expressing ABCA1 (such as HEK293 cells, HeLa cells, and COS-7 cells), sterol release to apoA-I cannot be detected. Cells that express ABCA1 include human fibroblast cell lines WI-38 and MRC-5, HepG2 cells, differentiated THP-1 cells, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, BALB/3 T3 cells, RAW264.7 cells treated with cAMP, and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells [16, 24–26].

Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) disease is a lysosomal storage disease accompanied by severe neurodegeneration that often leads to death in affected patients before adulthood. NPC disease is caused by a mutation either in the NPC1 or NPC2 gene. Both NPC1 and NPC2 proteins bind cholesterol and function in transporting cholesterol out from the late endosome and lysosome [2]. In NPC1- or NPC2-deficient human fibroblasts and CHO cells, cholesterol and other lipids accumulate within the late endosome and lysosome compartments and fail to reach other membrane compartments. Mutant NPC cells serve as effective tools to study cholesterol transport pathways (see Fig. 2).

One needs to keep in mind that in addition to cholesterol, the colorimetric enzymatic assay described in this chapter may detect precursor sterols that can be the substrates of cholesterol oxidase.

ABCA1 expression is highly regulated at the transcriptional level. Treating cells with LXR and/or RXR ligands induces ABCA1 expression and significantly increases sterol release [27]. Several synthetic and natural LXR ligands including TO901317 and 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, respectively, are commercially available. The RXR ligand 9-cis retinoic acid is also commercially available. However, one needs to keep in mind that the colorimetric enzymatic assay described in this chapter can detect oxysterol used to induce ABCA1 expression.

When incubating with or without apoA-I, the BSA concentration in Medium B can be reduced to 0.02% instead of 0.1% (w/v).

ApoA-I is the most physiologically relevant lipid acceptor to assess ABCA1-dependent lipid release because apoA-I is the major apolipoprotein of HDL. However, other α-helix containing apolipoproteins such as apoA-II and apoE [28], and synthetic α-helical peptides [29, 30] can also induce lipid release in an ABCA1-dependent manner. In addition, sodium taurocholate can also mediate ABCA1-dependent lipid release [31].

Approximately 80% or 90–100% of lipid release ability can be observed by using 5 or 10 µg/mL of apoA-I, respectively.

A shorter incubation time can be used. In this case (for example; 6–8 h incubation with apoA-I), lipids extracted from two or more wells per assay may be required in order to exceed the detection limit of the assay employed.

This step is required to remove phenol red. When cholesterol contents are determined by using a colorimetric enzymatic assay, phenol red present in medium causes overestimation due to its color.

A 96-well plate used here should be resistant to organic solvent. Corning® Polypropylene Flat Bottom 96 Well Microplate is recommended.

0.08–20 µg per well of cholesterol can be quantitatively measured by this method [26].

We use the cholesterol standard aqueous solution obtained from Wako. A cholesterol standard can also be prepared by dissolving cholesterol in chloroform-methanol. In this case, this step should be performed before step 20.

The same procedure can be applied to measure phospholipid content. In this case, Phospholipids B (Wako) or Determiner L PL (Kyowa Medex) kit is used as a colorimetric enzymatic assay. Because these assay kits are based on the use of choline oxidase, only choline-containing phospholipids (including phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin) are detected. The detection range is 0.15–20 µg per well.

When determining cell cholesterol levels, measuring both free cholesterol and total cholesterol (free cholesterol and cholesteryl esters) is recommended, which allows one to calculate the amounts of cholesteryl ester by subtracting free cholesterol from total cholesterol. Total cholesterol can be measured by adding cholesterol esterase (at final concentration of 0.1 U/mL; available from Wako) to the free cholesterol assay reagent.

In order to monitor the fate of endogenously synthesized sterols, the labeling conditions are critical. The half-life of various precursor sterols is less than 1 h. Thus, ABCA1-dependent release of [3H]-precursor sterols can only be detected under condition I (Fig. 2a). Even under condition II, it is difficult to detect the release of [3H]-precursor sterols, due to their rapid conversion to cholesterol.

The bottom fraction contains saponified fatty acids. This fraction should not be discarded if fatty acid analysis is required. For fatty acid analysis, acidify the saponified fraction by adding 0.3 mL of 12 M hydrochloric acid (HC1). Extract fatty acids by 2 mL of hexane or petroleum ether 4 times as described in steps 19–22. Concentrate the hexane extract to ~3 mL under nitrogen gas, wash once with 1 mL of 5 mM HC1 and once with 1 mL of ddH2O. After blowing the sample to dryness under nitrogen gas, add oleic acid (40 µg/tube) as an internal standard, spot samples onto a TLC plate and run in a TLC tank with petroleum ether–ether–acetic acid (90:10:1). Afterwards, the fatty acid bands are identified by iodine staining, scraped and their radioactivities are counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

We use a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph connected to a Shimadzu QP5000 mass spectrometer and equipped with an XTI-5 (30 m × 25 µm × 0.25 mm) capillary column. For this system, the injector port is set at 290 °C. The temperature program for the column is as follows: the initial temperature of the oven is 110 °C and the temperature is increased at a rate of 15 °C/min to 290 °C and held for 10 min (total run time 22 min). Helium flow is maintained at a constant rate of 1.3 mL/min.

The sterol masses are quantified using epicoprostanol (as an internal standard) by comparing the relative areas of the individual peaks from the chromatogram. The mass spectrometer is operated in scan mode to observe both the molecular ions and the fragmentation patterns for the individual sterol derivatives. In our experiments, TMS-derivatives of five standard sterols, epicoprostanol, cholesterol, lathosterol, desmosterol, zymosterol, and lanosterol, were clearly separated under this condition. The GC-MS procedure also allowed us to identify TMS-derivatives of the following 10 cellular sterols; lanosterol (C30), monounsaturated 4,4-dimethyl sterol (C29), diunsaturated 4,4-dimethyl sterol (C29), two monounsaturated monomethyl sterols (C28), desmosterol (C27), 5α-cholesta-7,24-dien-3β-ol (C27), zymosterol (C27), lathosterol (C27), and cholesterol (C27) [15]. Also, refer to earlier works [32, 33].

References

- 1.Goldstein J, DeBose-Boyd R, Brown M. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang T-Y, Chang CCY, Ohgami N, Yamauchi Y. Cholesterol sensing, trafficking, and esterification. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:129–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tall A, Yvan-Charvet L, Terasaka N, Pagler T, Wang N. HDL, ABC transporters, and cholesterol efflux: implications for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;7:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarling EJ, de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Edwards PA. Role of ABC transporters in lipid transport and human disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24:342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hara H, Yokoyama S. Interaction of free apolipoproteins with macrophages. Formation of high density lipoprotein-like lipoproteins and reduction of cellular cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3080–3086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis GA, Knopp RH, Oram JF. Defective removal of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids by apolipoprotein A-I in Tangier disease. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:78–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI118082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks-Wilson A, Marcil M, Clee SM, Zhang LH, Roomp K, van Dam M, et al. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;22:336–345. doi: 10.1038/11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodzioch M, Orsó E, Klucken J, Langmann T, Böttcher A, Diederich W, et al. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;22:347–351. doi: 10.1038/11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rust S, Rosier M, Funke H, Real J, Amoura Z, Piette JC, et al. Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1. Nat Genet. 1999;22:352–355. doi: 10.1038/11921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloch KE. Sterol structure and membrane function. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1983;14:47–92. doi: 10.3109/10409238309102790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter FD. Malformation syndromes due to inborn errors of cholesterol synthesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:715–724. doi: 10.1172/JCI16386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echevarria F, Norton R, Nes W, Lange Y. Zymosterol is located in the plasma membrane of cultured human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8484–8489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson WJ, Fischer RT, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH. Efflux of newly synthesized cholesterol and biosynthetic sterol intermediates from cells. Dependence on acceptor type and on enrichment of cells with cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25037–25046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lusa S, Heino S, Ikonen E. Differential mobilization of newly synthesized cholesterol and biosynthetic sterol precursors from cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19844–19851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamauchi Y, Reid PC, Sperry JB, Furukawa K, Takeya M, Chang CCY, Chang T-Y. Plasma membrane rafts complete cholesterol synthesis by participating in retrograde movement of precursor sterols. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34994–35004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi Y, Yokoyama S, Chang T-Y. ABCA1-dependent sterol release: sterol molecule specificity and potential membrane domain for HDL biogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:77–88. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M063784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koivisto PV, Miettinen TA. Increased amounts of cholesterol precursors in lipoproteins after ileal exclusion. Lipids. 1988;23:993–996. doi: 10.1007/BF02536349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamauchi Y, Iwamoto N, Rogers MA, Abe-Dohmae S, Fujimoto T, Chang CCY, et al. Deficiency in the lipid exporter ABCA1 impairs retrograde sterol movement and disrupts sterol sensing at the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:23464–23477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cham BE, Knowles BR. A solvent system for delipidation of plasma or serum without protein precipitation. J Lipid Res. 1976;17:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama S, Tajima S, Yamamoto A. The process of dissolving apolipoprotein A-I in an aqueous buffer. J Biochem. 1982;91:1267–1272. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito H, Dhanasekaran P, Nguyen D, Holvoet P, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC. Domain structure and lipid interaction in human apolipoproteins A-I and E, a general model. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23227–23232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuhira K, Tsujita M, Yamauchi Y, Abe-Dohmae S, Kato K, Handa T, Yokoyama S. Potential involvement of dissociated apoA-I in the ABCA1-dependent cellular lipid release by HDL. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:645–652. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300257-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vedhachalam C, Duong PT, Nickel M, Nguyen D, Dhanasekaran P, Saito H, et al. Mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporter Al-mediated cellular lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I and formation of high density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25123–25130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamauchi Y, Abe-Dohmae S, Yokoyama S. Differential regulation of apolipoprotein A-I/ATP binding cassette transporter Al-mediated cholesterol and phospholipid release. BBA-Mol Cell Biol L. 2002;1585:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamauchi Y, Chang CCY, Hayashi M, Abe-Dohmae S, Reid PC, Chang T-Y, Yokoyama S. Intracellular cholesterol mobilization involved in the ABCAl/apolipoprotein-mediated assembly of high density lipoprotein in fibroblasts. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1943–1951. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400264-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abe-Dohmae S, Suzuki S, Wada Y, Aburatani H, Vance D, Yokoyama S. Characterization of apolipoprotein-mediated HDL generation induced by cAMP in a murine macrophage cell line. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11092–11099. doi: 10.1021/bi0008175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costet P, Luo Y, Wang N, Tall A. Sterol-dependent transactivation of the ABC1 promoter by the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28240–28245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hara H, Hara H, Komaba A, Yokoyama S. Alpha-helical requirements for free apolipoproteins to generate HDL and to induce cellular lipid efflux. Lipids. 1992;27:302–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02536480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendez AJ, Anantharamaiah GM, Segrest JP, Oram JF. Synthetic amphipathic helical peptides that mimic apolipoprotein A-I in clearing cellular cholesterol. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1698–1705. doi: 10.1172/JCI117515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remaley AT, Thomas F, Stonik JA, Demosky SJ, Bark SE, Neufeld EB, et al. Synthetic amphipathic helical peptides promote lipid efflux from cells by an ABCA1-dependent and an ABCA1-independent pathway. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:828–836. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200475-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagao K, Zhao Y, Takahashi K, Kimura Y, Ueda K. Sodium taurocholate-dependent lipid efflux by ABCA1: effects of W590S mutation on lipid translocation and apolipoprotein A-I dissociation. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1165–1172. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800597-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks CJ, Horning EC, Young JS. Characterization of sterols by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of the trimethylsilyl ethers. Lipids. 1968;3:391–402. doi: 10.1007/BF02531277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerst N, Ruan B, Pang J, Wilson WK, Schroepfer GJ. An updated look at the analysis of unsaturated C27 sterols by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:1685–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]