Abstract

Mutations in the MEF2C ( myocyte enhancer factor 2 ) gene have been established as a cause for an intellectual disability syndrome presenting with seizures, absence of speech, stereotypic movements, hypotonia, and limited ambulation. Phenotypic overlap with Rett's and Angelman's syndromes has been noted. Following the first reports of 5q14.3q15 microdeletions encompassing the MEF2C gene, further cases with point mutations and partial gene deletions of the MEF2C gene have been described. We present the clinical phenotype of our cohort of six patients with MEF2C mutations and compare our findings with previously reported patients as well as with a growing number of genetic conditions presenting with a severe neurodevelopmental, Rett-like, phenotype. We aim to add to the current knowledge of the natural history of the “MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome” as well as of the differential diagnosis, clinical management, and genetic counseling in this diagnostically challenging group of patients.

Keywords: MEF2C, intellectual disability, speech delay, epilepsy, involuntary movements

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders including Rett's syndromes (RS), Rett-like syndromes, and Angelman's syndrome (AS) present with severely restricted or absent expressive language, seizures, and stereotypies and are characterized by vast genetic heterogeneity and significant clinical overlap. 1 An important fraction of patients with the clinical diagnosis of RS and AS remains molecularly undiagnosed. 2 3 The list of pathogenic mutations associated with a Rett-like phenotype has been growing, including those in the genes FOXG1, CDKL5, SLC9A6, TCF4, MEF2C ( myocyte enhancer factor 2 ), and others; these probably account for a fraction of previously unexplained underlying genetic etiology. 2 3 4 5 6 7 Achieving a clinical diagnosis in this heterogeneous group of disorders, which can be of a very diverse genetic background, is therefore highly challenging.

Loss-of-function mutations in the MEF2C gene have been found in patients with a complex, RS-like phenotype. 2 8 9 10 The MEF2C gene was originally identified as the phenocritical gene in the 5q14.3 microdeletion syndrome. 9 11 12 Consequently, patients with intragenic deletions and point mutations were identified, further confirming the pathogenicity of haploinsufficiency of the MEF2C gene. 13 14 Haploinsufficiency of MEF2C has been suggested as the most likely pathogenic mechanism as patients with both deletions and truncating and missense MEF2C mutations present with a similar, distinct phenotype. On the other hand, there are only a few reports of duplications of the MEF2C gene. These individuals seem to present with a milder phenotype of mild cognitive impairment, speech disorder, microcephaly, and mild ventriculomegaly. 9 15 Furthermore, a case of an affected monochorionic twin pregnancy with MEF2C duplication and abnormal corpus callosum in both twins has been described, and a pathogenic role for MEF2C overexpression in the developing brain has been proposed as the causative mechanism in MEF2C duplication. 15

Typical clinical characteristics in individuals with MEF2C mutations encompass severe global developmental delay with absent speech, limited walking, seizures, and stereotypic movements. Pregnancy and neonatal course are typically uneventful, but early hypotonia, feeding difficulties, and poor eye contact can occur. Some but not all of the MEF2C patients show stereotypic behavior, particularly hand flapping, clapping, mouthing, head rocking, and hand biting. 10 13 14 Purposeful hand use is generally present and retained. Patients can have various types of epilepsy, although they can also be seizure-free. Seizures arise typically during infancy or early childhood and are commonly associated with fever. Most of the time, the seizures respond well to medication. Growth is generally normal, and there is no known increased risk of internal congenital malformations. In contrast to patients with RS, no period of developmental regression or microcephaly is observed. Furthermore, commonly reported symptoms are episodic hyperventilation, autistic features, tendency to recurrent infections (upper respiratory tract), constipation, and ametropia (myopia, hyperopia, strabismus). 10 Minor brain abnormalities have been described with delayed myelination reported in point mutation cases and cortical malformations in patients with microdeletions. 13 One case of concentric myocardial hypertrophy has been described in a patient with a MEF2C deletion, 16 but this has not been subsequently confirmed as an associated feature in other studies and may be a coincidental finding.

The phenotypic overlap with RS was noted and a common molecular pathway was proposed. MEF2C loss-of-function mutations diminish synergistic transactivation of both MECP2 and CDKL5 . 17 MEF2C codes for a transcription factor essential for normal brain, craniofacial, heart, and vascular development. 17 18 19

We present a new cohort of patients with MEF2C mutations, one whole gene, four partial gene deletions, and a new point mutation. We compare our findings with those of disorders with significant phenotypic overlap and discuss the MEF2C distinguishing features.

Methods

We present comprehensive clinical data of six novel patients presenting with MEF2C -associated syndrome. Aberrations in the MEF2C gene were found using OGT (Oxford Gene Technology) chromosomal microarray in patients 1, 2, and 4, using the SNP6.0 array in patient 3, and using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification in patient 6. In patient 5, a nonsense mutation in MEF2C was found by next generation sequencing on a severe infantile epilepsy gene panel, and the variant was confirmed with Sanger sequencing of the MEF2C exon 3.

We reviewed the literature of published MEF2C cases and compared our findings to further delineate the MEF2C clinical presentation. 13 14

We compared the findings in our cohort of MEF2C patients with other severe neurodevelopmental disorders presenting with seizures, severely restricted or absent expressive language, gait difficulties, and stereotypic behavior. We reviewed the literature to include a comprehensive clinical presentation of Rett's, Angelman's, PittHopkins', Mowat–Wilson's, Christianson's, Phelan–McDermid's syndromes, adenylosuccinase deficiency, and mutations in the genes FOXG1, CDKL5, IQSEC2, STXBP1, CNTNAP2 , and WDR45 . 4 5 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Results

Clinical Features of Our Cohort and of Other Patients with the MEF2C-Linked Syndrome

Clinical features of the six patients (five females and one male) with a de novo pathogenic MEF2C mutation are presented ( Table 1 ). The oldest patient in our cohort was 10 years and 7 months old at her last examination, and the oldest reported in the literature was 14 years old. 13 14

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of our cohort of patients with MEF2C associated syndrome.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Male | Female | Female | |

| Age | 10 y 7 mo | 6 y 6 mo | 9 y | 2 y 6 mo | 3 y 1 mo | 3 y | |

| Mutations | Deletion breakpoints | Chr5:85,748,110- 91,307,813 | Chr5:88,098,253- 88,592,348 | Chr5: 88,034,622-88,164,453 | Chr5:88,193,289- 88,450,318 | / | / (MLPA) |

| Deleted genes | MEF2C, RASA1, ARRDC3, CCNH, CETN3, COX7C, GPR98 | MEF2C exons 1–3 | MEF2C exons 2–10 | MEF2C exon 1 | / | MEF2C exons 1–2 | |

| cDNA change | / | / | / | / | c.220G>T het | / | |

| Amino acid change | / | / | / | / | p.Glu74Ter | / | |

| De novo | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Prenatal exposures | Gestational diabetes, on insulin | valproate | − | − | − | n/a | |

| Growth | Birth weight | 2.86 kg | 3.7 kg | 4.14 kg | 3.29 kg | 3.20 kg | 3.46 kg |

| Height | p75 | p75-91 | p50 | p9 | p25 | n/a | |

| Weight | p75 | p91-98 | p9 | p2-9 | p25 | n/a | |

| Head circumference | p9 | p91-98 | p50 | p25 | p50 | p25 | |

| Development | Global developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Absent speech | + | + | − | + | + | − | |

| Gross motor delay | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Independent sitting (age) | 18 mo | 12–14 mo | 12 mo | 10–11 mo | 12 mo | n/a | |

| Independent walking (age) | − | 2 y | 3 y 6 mo | 2 y 6 mo | − | 2 y 2 mo | |

| Regression | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Neurologic | Seizures type/onset age/treatment | Myoclonic epilepsy, < 1 y, valproate | Generalized tonic–clonic seizures, started as febrile, infancy, valproate | Generalized seizures, started as febrile, < 1 y, - | Generalized seizures and absences, started as febrile, 15mo, - | Febrile and afebrile seizures, < 1 y, valproate and phenobarbital | − |

| Stereotypic movements | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Repetitive hand movements | Hand flapping | + | Hand flapping, clasping in midline, screws paper up | n/a | Hand wringing | + | |

| Purposeful hand use | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Ceiling gazing | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Bruxism | + | + | + | n/a | + | − | |

| Hand mouthing | + | n/a | + | + | n/a | n/a | |

| Other | Head nodding | n/a | Tongue thrusting | n/a | Rocks in her chair | Hand wringing | |

| Eye contact | + | Poor | Makes eye contact with people she knows, will not look at strangers | n/a | transient | n/a | |

| Sleeping problems | + | − | + | + | + | n/a | |

| Behavior | Obsessive, specific eating pattern, likes running water | Autistic traits, likes music, light and water | Generally happy, laughing, short attention span, overfills mouth when self-feeding, loves water | Overfills mouth when self-feeding | Happy | Excitable personality | |

| Social interaction | Plays alone with very simple activities | Plays alone, tolerates hugs | Enjoys being around other children, smiles at people she knows, does not like being touched | Responsive to familiar adults, possible autism | Loves human contact and interaction | ||

| Vision | Mild myopia | Registered blind | − | − | Mild myopia | n/a | |

| Episodic breathing abnormalities (onset age) | 2 wk | − | 3 y | n/a | − | − | |

| Hypotonia | Progressed into spasticity by the age of 7 y | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Hypermobility | n/a | + | n/a | n/a | + | + | |

| Reflexes | Reduced | n/a | − | Brisk | n/a | n/a | |

| Brain MRI | Thick CC | Frontal cortical atrophy and moderate ventriculomegaly | Small CC, possible white matter abnormality in occipital lobes | Small splenium of CC, mild ventriculomegaly | Normal | n/a | |

| EEG | High amplitude spike/poly spike and slow wave complexes bilaterally with slight right sided predominance | n/a | Dysrythmic background with high voltage poly spike wave bursts (centrencephalic neuronal hyperexcitability) | n/a | Bilateral temporal slow waves and bilateral parietal spike waves | n/a | |

| Head shape | Asymmetric brachycephaly | − | Scaphocephaly | − | Mild posterior plagiocephaly | − | |

| Facial dysmorphisms | Broad forehead | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Down turned corners of the mouth | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| Prominent philtral pillars | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Short columella | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Tented upper lip | − | + | + | + | Slightly | − | |

| Depressed nasal bridge | + | + | + | + | − | ||

| Epicanthic folds | + | − | − | + | |||

| Hypertelorism | + | − | − | − | |||

| Large mouth/full lips | + | + | + | − | + | ||

| Recurrent infections | + | + | − | − | + | n/a | |

| Feeding difficulties | Severe GERD | − | + | Severe GERD | Severe GERD | + | |

| Constipation | + | − | − | As baby | + | − | |

| Jugular pit/sternal fistula | − | − | − | − | − | n/a | |

| Cardiac abnormalities | − | PDA closed with a coil, PFO | − | − | − | n/a | |

| Skin/ pigmentation | Hemangiomas | + | + | − | − | − | |

| Pale blue eyes | + | + | + | − | + | ||

| Other | Floppy larynx, cold hands and feet | Duplex left kidney, broad based and unstable gait | Drooling, poor coordination, wide-based gait | − | Cleft palate | Drooling, ataxic, walking with support at the age of 3 y | |

Abbreviations: -, absence of feature; +, presence of feature; CC, corpus callosum; cDNA, complementary deoxyribonucleic acid; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; n/a, data not available; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PFO, persistent foramen ovale; /, not relevant.

All patients manifested delay in gross motor development, with latest age for sitting unaided by 18 months, crawling by 5 years, and pulling to stand by 7 years. Patient 1 that showed most severe delay in achieving major motor milestones was the one with the largest (5.6 Mb) deletion encompassing multiple genes. Expressive language in MEF2C syndrome is typically severely impaired or absent. Only two of our patients (patient 3 and 6) developed some limited speech and communication abilities. While patient 3 had no words by the age of 40 months, she showed significant improvement later on and was using a few words in context by the age of 9 years. Patient 6 displayed good understanding and was using up to maximum 15 words by the age of 3 years.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was performed in five of our patients and showed mild central nervous system abnormalities in four (80%), including frontal cortical atrophy and moderate ventriculomegaly, abnormalities of corpus callosum, and posterior white matter abnormalities.

Facial features of patients 1, 3, and 5 are presented in Fig. 1 . Patients are not overtly dysmorphic, but do present with distinct minor facial characteristics including a high and wide forehead, flat nasal bridge, epicanthic folds, tented upper lip, down turned corners of the mouth, short columella, a short philtrum with prominent pillars, and often pale blue eyes. Our patient with cleft palate (CP) is the first MEF2C patient presenting with abnormalities of craniofacial development.

Fig. 1.

Frontal and lateral views of patients with MEF2C ( myocyte enhancer factor 2 ) linked syndrome. ( A ) Patient 1 at the age of 2 years. Note broad forehead, pale blue eyes, flat nasal bridge, characteristic prominent philtral pillars, and short columella. ( B ) Patient 3 at the age of 3 years and 5 months. Note pale blue eyes, prominent philtrum, tented upper lip, and wide mouth with thick lower lip. ( C ) Patient 5 at the age of 3 years. Note the characteristic “ceiling-gazing” behavior and slight tenting of the upper lip.

None of our patients displayed the fossa abnormality (pit/sternal fistula), which was previously reported as a specific recurrent clinical finding in MEF2C patients. 12 14 29 36 None of our patients had developed any life-threatening symptoms.

Genetic Features of Our Cohort

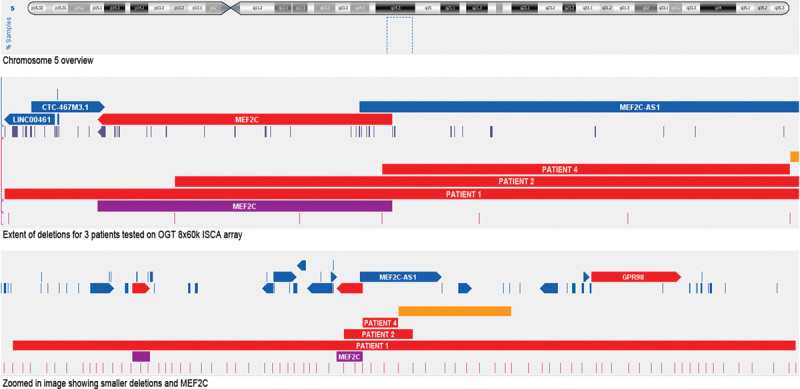

Distinct deletions of MEF2C in patients 1, 2, and 4 are presented on chromosomal microarray image ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Microarray findings. Deletions of the MEF2C ( myocyte enhancer factor 2 ) gene in the genomic region 5q14.3q15 with the location of the deletions of our novel patients: patients 1, 2, and 4 are presented from bottom to top.

The MEF2C c.220G>T mutation found in patient 5 results in a premature stop codon at the protein level (pGlu74Ter) and is therefore predicted to be pathogenic. This mutation has not been previously reported. It is located in the Mef2 DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) binding domain of the MEF2C transcription factor and is predicted to be pathogenic according to MutationTaster (MT; www.mutationtaster.org ).

Clinical Comparison with Other Severe Neurodevelopmental Disorders with Seizures, Absent Speech, and Stereotypic Hand Movements

An overview is presented ( Table 2 ). The phenotypic overlap to RS and other similar syndromes is significant, but with the important distinction that in MEF2C , usually there is no microcephaly and no neurodevelopmental regression. There are some possible unique distinguishing features such as “ceiling-gazing” stereotypy.

Table 2. Clinical comparison of our cohort with other severe neurodevelopmental disorders with seizures, absent speech, and stereotypic movements.

| Microcephaly | Global developmental delay | Absent speech | Independent walking (mean age) | Developmental regression | Seizures (%) | Involuntary movements (frequency) | Purposeful hand skills | Poor eye contact | Autistic features, Behavior | Easily provoked, excessive laughter | Sleeping problems | Vision problems | Episodic breathing abnormalities | Hypotonia | Ataxic gait | Feeding difficulties | Constipation | Cardiac abnormalities | Cold hands and feet | Distinctive facial features | Brain MRI | EEG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEF2C This study | − | + | 4(6) | 4(6) 2 y 6 mo | 1(6) | 5(6) | Hand flapping, wringing, clasping, paper screwing, tongue thrusting, chair rocking, ceiling gazing 6(6) | + | 3(4) | 4(5) | − | 4(5) | 3(5) | 2(5) | + | 3(4) | 5(6) with severe GERD in three | 3(5) | 1(5) | 1(5) | Broad forehead, flat nasal bridge, epicanthus, tented upper lip, short columella, prominent philtral pillars, large mouth, pale blue eyes | 4(5): ventriculomegaly, CC abnormalities, frontal cortical atrophy, white matter abnormalities | Abnormal EEG 3(3): bilateral slow wave with high voltage spike /poly spike bursts |

| MEF2C point mutations ( Rocha 2016 ) | n/a | + | + | 4(8) 2 y 8 mo | 1(9) | + | Hand stereotypies, mouthing, biting fingers 5(9) | n/a | 3(7) | 3(7) | − | n/a | Strabismus | n.a | 6(8) | + | 3(4) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 6(8): ventriculomegaly, delayed myelination, hyperintense periventricular white matter, enlarged CSF spaces | n/a | |

| MEF2C partial deletions ( Tanteles 2014 ) | − | + | 7(8) | 1(4) 2 y 6 mo | 0(6) | 4(7) | Flapping, clapping, batting, mouthing, waving hands in front of face, bruxism, head shaking, rocking back and forth, hand biting to injury 7(8) | n/a | 4(5) | Scared of loud noises, would head bang | − | 2(6) | Myopia | 1(5) Breath holding behavior | 6(7) | + | Severe GERD in two | n/a | n/a | n/a | 3(5): thin CC, delayed myelination, unspecific white matter lesions, enlarged 4th ventricle mildly enlarged extracerebral CSF spaces | n/a | |

| Typical Rett ( Tan 2013, Watson 2001, Genereviews ) | acquired | + | Some | Regression | + | In up to 90% | Hand washing, wringing, squeezing, clapping, patting, tapping, rubbing, mouthing, plucking clothing, hand biting | Loss of purposeful hand use | Intense, dreamlike stare | Paniclike attacks, screaming fits, inconsolable crying, autistic features | + | Night laughter, prolonged wakefulness, early morning awakenings | Ametropia, astigmatism | Episodic apnea and/or hyperpnea | + | Dyspraxic gait | Oropharyngeal and gastroesophageal incoordination | + | Cardiac rhythm disturbances | + | − | Reductions of dorsal parietal gray matter and preservation of occipital cortex (Carter et al. 2008) | Generalized background slowing and/or loss of the occipital dominant rhythm with further theta and delta slowing |

| Angelman ( Tan 2013, Watson 2001, Genereviews ) | acquired (true or relative) (30%) | + | Minimal to no use of words | 2,5–6 y (90%) | Unusual | 65–90%, onset usually before 3 y | Hand flapping, hypermotoric, mouthing of objects, tongue thrusting | Not well developed at any stage | Seek eye contact | Happy, fascination with water, most enjoy social contact, hyperactivity and aggression | + | 70–80% | Myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, strabismus, ocular hypopigmentation | − | + | + | + | + | − | Not common | Thin upper lip vermillion, widely spaced teeth, deep set eyes, wide smiling mouth, prominent chin | Delayed myelination. white matter abnormalities, mild cortical atrophy, hypoplastic CC | Pathognomonic EEG: large-amplitude slow-spike waves |

| Pitt Hopkins ( Tan 2013, Peippo 2012, Genereviews ) | true or relative (10–65%) | + | Minimal to no use of words | 4–6 y (<50%) | Unusual | 40–50% | Flapping, clapping, wringing, swaying, finger crossing, head rolling or rotation (40–60%) | Two patients lost the use of hand skills | − | Happy, sociable, often withdrawn in own world, outbursts of aggression | Variable | Fewer than half, excess sleep in infancy | High myopia, astigmatism | + | + | + | Rare | Severe | − | + | Abnormal helices, deep set eyes, full cheeks, malar prominence, widely spaced teeth | CC hypoplasia, ventricular dilatation, cerebellar atrophy/vermian hypoplasia | EEG may change from normal to significantly abnormal, frontal pseudoperiodic delta waves, focal spikes slow/slow-and-sharp-wave activity |

| Mowat Wilson ( Tan 2013, Garavelli 2007, Genereviews ) | >80% | Moderate to severe | Minimal to no use of words | 3–4 y | − | 70–75% | Mouthing (95%), bruxism (87%), flick, tap and twirl objects (58%), turning pages, flicking lights on and off, repeated head movements | + | Variable | Happy demeanor with frequent smiling, affectionate and sociable personality | Only 20% | + | 4,1% structural eye abnormalities: microphthalmia, coloboma, Axenfeld anomaly | − | Infancy | With arms upheld | Some | + | 52% most common: PDA, pulmonary stenosis, VSD | n/a | Uplifted earlobes, thick medially flared eyebrows, overhanging nasal tip, low-insertion columella, prognathism | CC hypoplasia or agenesis (43%), ventriculomegaly, cortical atrophy, pachygyria, cerebellar hypoplasia, poor hippocampal formation, frontotemporal hypoplasia with temporal dysplasia | Normal or mild slowing at seizure onset |

| Christianson ( Schroer 2010, Tan 2013, Seltzer 2014 ) | acquired | + | + | Loss of ambulation (teenage y) | + | + | Staring at own hands, pill-rolling hand movements, clapping, dystonia | Loss of fine motor skills | n/a | Happy demeanor | + | + | Impaired ocular movement (ophthalmoplegia) | n/a | + | + | Swallowing difficulties, GERD | n/a | n/a | n/a | Emaciation, long narrow face with prominent nose, jaw and ears | Cerebellar, brainstem and hippocampus atrophy, CC hypoplasia | Normal / “frontal high-amplitude 2–3 Hz” spike and wave activity |

| Microcephaly | Global developmental delay | Absent speech | Independent walking (mean age) | Developmental regression | Seizures (%) | Involuntary movements (frequency) | Purposeful hand skills | Poor eye contact | Autistic features /behavior | Easily provoked/excessive laughter | Sleeping problems | Vision problems | Episodic breatding abnormalities | Hypotonia | Ataxic gait | Feeding difficulties | Constipation | Cardiac abnormalities | Cold hands and feet | Distinctive facial features | Brain MRI | EEG | |

| Phelan–McDermid's syndrome (Costales and Kolevzon, 22 Tan et al, 3 GeneReviews) | Microcephaly (up to 14%), macrocephaly (up to 31%) | Moderate to severe | + | 3 y Some unable to ambulate | + | 14–41% | Mouthing, chewing nonfood items, repetitive use and spinning of objects, stereotypic vocalizations | Poor | Autisticlike, impaired social interaction | − | 41–46% | Hyperopia, myopia, in 6% cortical visual impairment | − | + | + | + | − | 3–13% | − | Large ears, full brow, full cheeks, puffy eyelids, deep set eyes | Arachnoid cysts in 15%, ventriculomegaly, dysmyelination, thin CC, posterior fossa abnormalities | Abnormal EEG in six patients with a febrile seizures | |

| CDKL5 (Tan et al, 3 Fehr et al, 39 Seltzer and Paciorkowski 34 ) | + | + | Minimal to no use of words | 10,8% F, 0 M 39,6m | − | Early-onset, before 3 mo | Mouthing, wringing, clapping, biting, clasping (80% F, 33% M) | Acquired in over half F (and 1 M), of whom 30% lost the ability | Poor, “eye pointing” in 15% | + | n/a | + | n/a | 50,0–66,6% | + | + | + | 40–77% | Large deep set eyes, high forehead, full lips, wide mouth, widely spaced teeth | Global atrophy, decreased white matter volume | Unique: bilateral synchronous electrodecrement followed by repetitive spikes and sharp waves | ||

| FOXG1 (Florian et al, 4 Tan et al 3 ) | Severe before 4 mo, can be congenital | + | + | Rare 1(11) | In the first 5 mo | + | Hand pulling, pill rolling, wringing of fingers, protrusive tongue movements, bruxism | Hand dyskinesia | Poor 5(8) | Impaired social interaction | n/a | 6(11) | High prevalence of strabismus, keratoconus (one case) | − | + | n/a | + | n/a | n/a | + | Round face, sloping forehead, bitemporal narrowing, full cheeks, flat midface, bulbous nasal tip | Delayed myelination, agenesis or hypoplasia of CC, frontal and temporal atrophy with gyral simplification | Multifocal pattern with spikes and sharp waves |

| IQSEC2 (Tran Mau-Them et al, 28 Allou et al 2 ) | Acquired progressive | mild to severe | No language or speech delay | Variable | Variable | + | Hand washing/rubbing | No (1) | Variable | Self-injury, aggressive behavior, unexplained crying episodes | Rare | − | Impaired (hypermetropia) | Rare | + | − | n/a | n/a | n/a | − | High forehead, short philtrum, full lips (one patient at the age of 28 y) | One patient at the age of 28 y with cerebral atrophy | Normal |

| STXBP1 (Deprez et al, 20 Saitsu et al, 21 OMIM) | − | Severe to profound | + | Rare, one patient began walking at the age of 7 y | + | Early onset 3d - 4,5m | Dyskinetic movements, stereotypic behavior | One patient feeds self | Weak eye pursuit, poor visual attention | Hyperactivity | n/a | n/a | One patient with cortical visual impairment | n/a | + | Ataxia | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | − | Brain hypomyelination, thin CC, cerebral atrophy | Focal or bilateral synchronous discharges, burst suppression pattern, West's syndrome |

| BPAN (WDR45) (Hoffjan et al, 43 Hayflick et al 44 ) | Acquired in one patient | + | Very limited | 2(7) | Secondary neurologic decline in adolescence | 5(7) | Washing, wringing, hand mouthing, bruxism, dystonia | + | Intense eye contact | Variable | + | Variable | Myopia, astigmatism, abnormal pupil, coloboma, retinal detachment, increased VEP latency, patchy loss of pupillary ruff | − | Spasticity | + | − | + | n/a | n/a | Small mouth with a tented upper lip, large ears | Thin CC, delayed myelination, ventriculomegaly, and cerebral, cerebellar, and pons atrophy; later on signs of iron deposition in the SN and GP | Spike and slow wave activity, focal/generalized epileptiform discharges, diffuse background slowing with superimposed bursts of fast rhythms |

| Adenylosuccinase deficiency (Spiegel et al, 26 Jurecka et al 27 ) | Acquired | Mild to severe | Very limited to absent | Rare, 2–6 y | Loss of motor skills in late childhood because of spasticity | early-onset | Mouthing, clapping hands, head and trunk rocking, chafing of hands in front of eyes, rubbing feet, bruxism | n/a | + | Severe irritability, impulsivity, hyperactivity, aggressive, agitation, very happy demeanor reported in 1 family | Reported in 1 family | n/a | Strabismus, nystagmus, cortical visual impairment | Apnea | Hypotonia, spasticity can develop in late childhood | + | + | n/a | − | n/a | Small nose, thin upper lip, wide mouth, long smooth philtrum, prominent metopic suture | Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, delayed myelination, hypoplasia of CC | Burst suppression pattern |

| CNTNAP2 (Smogavec et al 6 ) | 1(8) microcephaly/ 1(8) macrocephaly | Moderate to severe | Variable, loss of speech or stagnation | 7/8 2,5 y (range 18 mo to 5 y) | Loss of speech 3(8) loss of motor skills 1(8) | Early onset 8(8) (<3,5 y) | Hand wringing, skin picking | 6(7) | Variable | Variable: hyperactivity, (auto) aggression, autism, tantrums (one was very sociable) | n/a | n/a | n/a | Hyperventilation 1(3) | Variable | Variable | Variable | Variable | − | n/a | − | 2(8): suspect cortical dysplasia, 2(8) white matter intensities, 1(8) vermian atrophy, 43% cortical dysplasia in the initial report 45 | slow rhythm, epileptic discharges |

Abbreviations: -, absence of feature; +, presence of feature; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CC, corpus callosum; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; F, female; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GP, globus pallidus; HR, heart rate; M, male; n/a, data not available; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; SN, substantia nigra; VSD, ventriculum septum defect.

We think that the subtle facial phenotype, as described previously, the “ceiling-gazing” behavior, and the presence of hemangiomas could be a clue to a MEF2C diagnosis.

Discussion

Clinical Delineation of “MEF2C Syndrome”

Patients with MEF2C syndrome show severe to profound developmental delay, limited or absent speech, seizures, hypotonia, limited walking abilities, and characteristic stereotypic behavior. Frequent findings also include poor eye contact, autistic behavior, episodic breathing abnormalities, feeding difficulties, constipation, strabismus, sleeping problems, a tendency to frequent infections, and subtle facial dysmorphism. The presenting clinical phenotype, although not instantly recognizable, is characteristic for MEF2C syndrome and compatible with that previously described in MEF2C clinical picture. 13 14 In all of our patients, the diagnosis was suspected clinically based on their array of distinctive features. In most cases, there was preliminary exclusion of RS or AS.

MEF2C is a transcription factor important in multiple developmental processes including neurogenesis and synaptic formation, myogenesis, development of the anterior heart field, neural crest, craniofacial development, chondrocyte hypertrophy and vascularization, endothelial cell proliferation, and lymphoid development. 10 30 31 In the developing brain, it regulates excitatory synapse number, dendrite morphogenesis, and differentiation of postsynaptic structures. It is highly expressed in frontal cortex, entorhinal cortex, cerebellum, dentate gyrus, and amygdala. 12 These findings explain the underlying molecular substrate for global developmental delay, seizures, hypotonia, autistic features, and presence of minor, usually nonspecific, brain abnormalities. Interestingly, periventricular heterotopia has been described in patients with 5q14.3q15 microdeletion, 32 but this has not been subsequently confirmed and it is thought to be due to other genes included in the deletion of the patients described by Cardoso et al. 32

Dermatological abnormalities were frequently described as part of the 5q14.3 microdeletion syndrome. This has been explained by the contiguous gene deletion involving the adjacent RASA1 gene, haploinsufficiency of which is causative for capillary malformation—arteriovenous malformation syndrome. 33 We confirm this association in our patient (number 1) presenting with multiple skin hemangiomas and a multiple gene deletion encompassing the RASA1 gene. Furthermore, we report on a patient (number 2) with a large capillary nevus of the lower limb but with an intragenic MEF2C deletion, encompassing the first three exons of MEF2C gene but not the RASA1 gene. As MEF2C has been shown to play an important role in vessel development targeting both genes for endothelial cell organization as well as smooth muscle cell differentiation, this might explain the cause of the capillary malformation in our patient, hereby expanding the MEF2C clinical phenotype. 34 The association might also be due to a long-range effect of the deletion on RASA1. The intragenic deletion in our patient with capillary malformation results in the deletion of exons 1 to 3, which are the same exons as were previously reported by Tanteles et al as being deleted in a Cypriot patient who also presented with a cutaneous vascular malformation. 14 We are hereby proposing an association of MEF2C exon 1 to 3 deletion with vascular malformations and a new genotype–phenotype correlation.

Furthermore, MEF2C is an important regulator of cardiac myogenesis and is expressed in heart cells before the formation of the heart tube. In homozygous mice for a MEF2C null mutation, the heart tube does not correctly loop, the right ventricle does not form, and a subset of cardiac muscle genes are not expressed. 19 So far, cardiomyopathy has only been reported in one patient. 16 Ultrasound heart examinations performed in our cohort showed normal scans except for patient 2. This patient was born with a persistent foramen ovale and a patent ductus arteriosus, which was closed with a coil; however, in that particular case, the mother has been treated with valproate during pregnancy, and this may have contributed to the offspring's cardiac presentation.

Our cohort includes a patient with a MEF2C point mutation, leading to a premature stop codon at the 74th amino acid of the MEF2C protein, and a CP. Family and prenatal history were not contributory for clefting. CP is quite frequent in the general population with an estimated incidence of 1 in 2,000. On the other hand, mice lacking MEF2C function manifest CP, and MEF2C has been proven to participate in craniofacial development. 30 Duplications of MEF2C have been associated with cranial asymmetry and metopic prominence in humans. 35 Further patient descriptions would be necessary to investigate whether CP may be an additional feature of this syndrome.

A jugular fossa abnormality (a jugular pit or fistula), which was previously presented as a characteristic recurrent clinical sign of MEF2C patients and a possible clue to the MEF2C diagnosis, 12 14 29 36 was not present in our cohort of patients.

In patients with RASA1 deletion, screening for associated vascular malformations is indicated (brain and spine imaging). In view of hereby published findings, further surveillance might also focus on craniofacial abnormalities (CP) and congenital heart disease. Melatonin has been reported as helpful in ameliorating sleep disturbances. Impaired vision, including myopia, hypermetropia, and astigmatism, seem to be common, and ophthalmological evaluation would be warranted to improve the outcome.

Genotype–Phenotype Correlation and Variability

All of the reported variants in the MEF2C gene occurred de novo and were heterozygous. Clinical variability may be partially explained by the type of mutation, and partial MEF2C deletions have been reported to cause a milder phenotype and have a better prognosis. 14 Patients with small deletions and intragenic mutations were more likely to acquire walking skills. 10 Some patients never experience seizures, especially patients with partial MEF2C deletions. 12 13 37 A lower risk of refractory seizures has been described for patients with point mutations. 10

To the best of our knowledge, only 10 patients with MEF2C point mutations including our patient have been identified so far, 13 and this limits the study of possible genotype–phenotype correlations. Still, some characteristics seem to emerge. All of our patients with smaller intragenic deletions did achieve independent walking (youngest at the age of 2 years, oldest at the age of 3 years). Smaller intragenic deletions therefore show a less severe effect as would also be expected, whereas the majority of 5q14.3-q15 microdeletion syndromes do not walk and remain very hypotonic. 9

Half of point mutation patients reported by Rocha et al have achieved independent ambulation, a finding previously reported by Novara in a review of 10 patients where only one patient (with a point mutation) reached independent walking (at the age of 3 years). Our patient with a point mutation was only 3 years and 1 month old at the time of her last examination; therefore, we cannot confirm the suggested lesser effect of the intragenic point mutation compared with a deletion regarding the ambulation skills.

Although lack of speech is considered a diagnostic finding in MEF2C, we report on two patients with intragenic deletions who developed limited speech abilities (one with a maximum word vocabulary of 15 words and good understanding at the age of 3 years, and the other using a few words in context at the age of 9 years). Besides our two patients, there is only one other case reported that maintained speech. 37 All these three patients harbor intragenic MEF2C deletions: one patient displays a deletion of exons 2 to 10 (patient 3, this study) and, interestingly, both two other patients display the same deletion of exons 1 to 2 (patient 6, this study, and a patient with 10 consistent words plus jargon as reported by Paciorkowski et al). 14 37

Distinguishing between Syndromic Intellectual Disability Disorders with Seizures, Absent Speech, and Repetitive Involuntary Movements

The syndromes included in Table 2 show significant overlap in clinical features including global developmental delay, absent speech, gross motor delay, inability to ambulate, seizures, and involuntary movements (repetitive stereotypies or dyskinesias). Historically, there are several reports of overlap in clinical features between RS, AS, and Pitt–Hopkins' syndrome. As much as 10% of patients with a clinical diagnosis of AS do not have a molecularly proven diagnosis, and it is possible that these patients actually have a different underlying genetic etiology. 3 Some patients with clinical diagnosis of AS were found to have MECP2 mutations. Unique distinguishing features between the two syndromes were suggested by the authors to be the presence of a movement disorder, pathognomonic electroencephalographic pattern, regression, and loss of purposeful hand use in patients with RS. 1 Approximately 2% of patients with unsteady gait, absent speech, and happy demeanor but normal 15q11.2 methylation test and UBE3A mutation analysis were subsequently diagnosed with Pitt–Hopkins' syndrome. 5

Distinction of these syndromes through clinical phenotyping is important for better diagnostic clarity and provision of better prognostic information. Lumping them under nonspecific umbrella terms such as Rett-like and Angelman-like has been discouraged, as there is gathering phenotypic and clinical history data to recognize most of these disorders as separate diagnostic entities. 38 39

Distinguishing features are quite a few; the first worth consideration is acquired microcephaly, which is present in many of these disorders (Rett, Angelman, CDKL5, SLC9A6 , and TCF4) . However, postnatal deceleration in head growth has been eliminated from the necessary criteria for RS, as it was not present in all patients. 40 41 Regression, typical for RS, can also occur in the setting of other syndromes, including epileptic encephalopathy. However, in RS, regression generally precedes the onset of seizures. 42 Unique clinical features have been reported, such as episodic breathing abnormalities (Rett, Pitt–Hopkins, CDKL5, MEF2C ), characteristic facial features (Mowat–Wilson, Pitt–Hopkins, MEF2C ), pattern of involuntary movements, specific behavioral phenotype (generally happy predisposition in Angelman, Mowat–Wilson, and Christianson; ceiling gazing in MEF2C ), absence of neurodevelopmental regression (Angelman, Pitt–Hopkins, Mowat–Wilson, MEF2C ), disruption of normal craniofacial ( MEF2C, FOXG1 ), and cardiac development ( MEF2C , Mowat–Wilson, Phelan–McDermid). Nonspecific features included in the Rett supportive criteria are variably present ( Table 2 ).

MEF2C patients do not usually meet the Rett diagnostic criteria for lack of acquired microcephaly and of the regression. 2 Epileptic seizures seem to be less severe and of a later onset than classic RS. MEF2C patients do not usually display progressive loss of previously acquired skills neither a previous period of normal development. 18 Phenotypic overlap between MEF2C and Rett has been explained by a shared molecular pathway, and decreased expression of MECP2 and CDKL5 (but not TCF4 ) was measured in vivo in blood of patients with a MEF2C proven mutation. 17

In some congenital and infantile forms of RS, CDKL5 and FOXG1 mutations were found as causative. CDKL5 gene mutations have been variably associated with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy, X-linked dominant infantile spasm syndrome, the early onset seizure variant of Rett syndrome and other epileptic disorders such as West syndrome. 39 In most cases, patients present with a distinct clinical profile that in majority does not fulfill the Rett criteria. FOXG1 patients usually present with congenital microcephaly or early onset deceleration of head growth resulting in microcephaly before 4 months of age. Presentation in point mutations cases is usually severe and excludes the typical Rett regression period after a period of normal development, whereas 14q12 deletions are characterized by a normal perinatal period followed by a phase of regression at the age of 3 to 6 months. 4 FOXG1 presentation can include abnormalities of craniofacial development (CP).

Genes identified as causative in early epileptic encephalopathies and disorders of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) have been shown to present with a broad phenotypic spectrum and also include a Rett-like phenotype. 39 42 43 Striking clinical similarities between the X-linked neurodegeneration disorder BPAN (“β-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration,” an NBIA caused by mutations in the gene WDR45 ) and RS were described, and the causative WDR45 gene was suggested to be included in the multigene panels when testing for an RS or a variant RS. 44 Interestingly, both Rett and BPAN show X-linked dominant inheritance. In the case of BPAN, somatic mosaicism was suggested as an explanation for extreme phenotypic variability in males who can present with severe neonatal encephalopathy or mild intellectual disability based on the timing of mutation acquisition during embryogenesis. 44

Biallelic mutations in CNTNAP2 have been found to cause an autosomal recessive intellectual disability syndrome with epilepsy and cortical dysplasia. Phenotypic spectrum of CNTNAP2 seems to be broad involving behavioral anomalies, hand wringing, and abnormal breathing patterns, and therefore clinical presentation can be rather difficult to distinguish from other disorders that present with early onset seizures, developmental regression, and lack of or very limited speech. 6 In several CNTNAP2 patients, speech development was reported as normal and the microcephaly is rare; specific distinguishing features are cortical dysplasia and decreased deep tendon reflexes, but the cortical dysplasia does not seem to be as frequent as previously thought. 6

As we have shown, the etiology of syndromes presenting with severe intellectual disability, epilepsy, absence of speech, stereotypic movements, hypotonia, and limited walking ability is heterogeneous, including genes associated with epileptic encephalopathies, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, and NBIA disorders. First-tier testing through array comparative genomic hybridization is important as the majority (48/58) of the deleterious alleles affecting MEF2C so far were pathogenic copy number variants. Next, exome or broad panel sequencing, including the aforementioned genes, would be indicated, as the genes mentioned participate in various cellular pathways and are currently included in different genetic sequencing panels (intellectual disability, epileptic encephalopathy, clinical epilepsy panels, NBIA disorders).

Establishing the genetic diagnosis in a patient with a MEF2C -associated syndrome is important for better understanding of the natural history of this disorder, focusing attention on relevant health issues, prognostic consideration, and also avoidance of unnecessary testing. Understanding of underlying molecular mechanisms and shared pathways of these neurodevelopmental disorders ( MEF2C, MECP2, CDKL5 ) is important for planning pharmaceutical trials for possible future targeted treatment of the associated neurobehavioral symptoms. Although new cases are emerging, MEF2C -associated syndrome is relatively new and therefore its natural history has not yet been fully studied. Several of the symptoms are age-dependent, and several of the reported patients were too young to present the possible clinical manifestations. Therefore, further studies will be essential to more fully delineate the MEF2C clinical phenotype.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for their generous participation and agreement to publication of this article. The parents of patients 1, 3, and 5 also gave informed consent to the publication of the photographs.

References

- 1.Watson P, Black G, Ramsden S et al. Angelman syndrome phenotype associated with mutations in MECP2, a gene encoding a methyl CpG binding protein. J Med Genet. 2001;38(04):224–228. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.4.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allou L, Julia S, Amsallem D et al. Rett-like phenotypes: expanding the genetic heterogeneity to the KCNA2 gene and first familial case of CDKL5-related disease. Clin Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cge.12784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan W H, Bird L M, Thibert R L, Williams C A. If not Angelman, what is it? A review of Angelman-like syndromes. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(04):975–992. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florian C, Bahi-Buisson N, Bienvenu T.FOXG1-related disorders: from clinical description to molecular genetics Mol Syndromol 20122(3-5):153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peippo M, Ignatius J.Pitt-Hopkins syndrome Mol Syndromol 20122(3-5):171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smogavec M, Cleall A, Hoyer J et al. Eight further individuals with intellectual disability and epilepsy carrying bi-allelic CNTNAP2 aberrations allow delineation of the mutational and phenotypic spectrum. J Med Genet. 2016;53(12):820–827. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroer R J, Holden K R, Tarpey P S et al. Natural history of Christianson syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(11):2775–2783. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert L, Bienvenu T, Allou L et al. MEF2C mutations are a rare cause of Rett or severe Rett-like encephalopathies. Clin Genet. 2012;82(05):499–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novara F, Beri S, Giorda R et al. Refining the phenotype associated with MEF2C haploinsufficiency. Clin Genet. 2010;78(05):471–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zweier M, Rauch A.The MEF2C-related and 5q14.3q15 microdeletion syndrome Mol Syndromol 20122(3-5):164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nowakowska B A, Obersztyn E, Szymańska K et al. Severe mental retardation, seizures, and hypotonia due to deletions of MEF2C. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(05):1042–1051. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Meur N, Holder-Espinasse M, Jaillard S et al. MEF2C haploinsufficiency caused by either microdeletion of the 5q14.3 region or mutation is responsible for severe mental retardation with stereotypic movements, epilepsy and/or cerebral malformations. J Med Genet. 2010;47(01):22–29. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocha H, Sampaio M, Rocha R, Fernandes S, Leão M. MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome: report of a new MEF2C mutation and review. Eur J Med Genet. 2016;59(09):478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanteles G A, Alexandrou A, Evangelidou P, Gavatha M, Anastasiadou V, Sismani C. Partial MEF2C deletion in a Cypriot patient with severe intellectual disability and a jugular fossa malformation: review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(03):664–669. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesaretti C, Spaccini L, Righini A et al. Prenatal detection of 5q14.3 duplication including MEF2C and brain phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A(05):1352–1357. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engels H, Wohlleber E, Zink A et al. A novel microdeletion syndrome involving 5q14.3-q15: clinical and molecular cytogenetic characterization of three patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(12):1592–1599. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zweier M, Gregor A, Zweier C et al. Mutations in MEF2C from the 5q14.3q15 microdeletion syndrome region are a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and diminish MECP2 and CDKL5 expression. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(06):722–733. doi: 10.1002/humu.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bienvenu T, Diebold B, Chelly J, Isidor B. Refining the phenotype associated with MEF2C point mutations. Neurogenetics. 2013;14(01):71–75. doi: 10.1007/s10048-012-0344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Q, Schwarz J, Bucana C, Olson E N.Control of mouse cardiac morphogenesis and myogenesis by transcription factor MEF2C Science 1997276(5317):1404–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deprez L, Weckhuysen S, Holmgren P et al. Clinical spectrum of early-onset epileptic encephalopathies associated with STXBP1 mutations. Neurology. 2010;75(13):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d7bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitsu H, Kato M, Mizuguchi T et al. De novo mutations in the gene encoding STXBP1 (MUNC18-1) cause early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Nat Genet. 2008;40(06):782–788. doi: 10.1038/ng.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costales J L, Kolevzon A. Phelan-McDermid syndrome and SHANK3: implications for treatment. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(03):620–630. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0352-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edery P, Chabrier S, Ceballos-Picot I, Marie S, Vincent M-F, Tardieu M. Intrafamilial variability in the phenotypic expression of adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency: a report on three patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A(02):185–190. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garavelli L, Mainardi P C. Mowat-Wilson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2(01):42. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gitiaux C, Ceballos-Picot I, Marie S et al. Misleading behavioural phenotype with adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(01):133–136. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiegel E K, Colman R F, Patterson D.Adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency Mol Genet Metab 200689(1-2):19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jurecka A, Zikanova M, Kmoch S, Tylki-Szymańska A. Adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38(02):231–242. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9755-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran Mau-Them F, Willems M, Albrecht B et al. Expanding the phenotype of IQSEC2 mutations: truncating mutations in severe intellectual disability. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(02):289–292. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Shehhi M, Betts D, Mc Ardle L, Donoghue V, Reardon W. Jugular pit associated with 5q14.3 deletion incorporating the MEF2C locus: a recurrent clinical finding. Clin Dysmorphol. 2016;25(01):23–26. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verzi M P, Agarwal P, Brown C, McCulley D J, Schwarz J J, Black B L. The transcription factor MEF2C is required for craniofacial development. Dev Cell. 2007;12(04):645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verzi M P, McCulley D J, De Val S, Dodou E, Black B L. The right ventricle, outflow tract, and ventricular septum comprise a restricted expression domain within the secondary/anterior heart field. Dev Biol. 2005;287(01):134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardoso C, Boys A, Parrini E et al. Periventricular heterotopia, mental retardation, and epilepsy associated with 5q14.3-q15 deletion. Neurology. 2009;72(09):784–792. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336339.08878.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carr C W, Zimmerman H H, Martin C L, Vikkula M, Byrd A C, Abdul-Rahman O A. 5q14.3 neurocutaneous syndrome: a novel continguous gene syndrome caused by simultaneous deletion of RASA1 and MEF2C. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(07):1640–1645. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Q, Lu J, Yanagisawa H et al. Requirement of the MADS-box transcription factor MEF2C for vascular development. Development. 1998;125(22):4565–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novara F, Rizzo A, Bedini G et al. MEF2C deletions and mutations versus duplications: a clinical comparison. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56(05):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berland S, Houge G. Late-onset gain of skills and peculiar jugular pit in an 11-year-old girl with 5q14.3 microdeletion including MEF2C. Clin Dysmorphol. 2010;19(04):222–224. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32833dc589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paciorkowski A R, Traylor R N, Rosenfeld J A et al. MEF2C haploinsufficiency features consistent hyperkinesis, variable epilepsy, and has a role in dorsal and ventral neuronal developmental pathways. Neurogenetics. 2013;14(02):99–111. doi: 10.1007/s10048-013-0356-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seltzer L E, Paciorkowski A R. Genetic disorders associated with postnatal microcephaly. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;166C(02):140–155. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fehr S, Wilson M, Downs J et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(03):266–273. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagberg G, Stenbom Y, Engerström I W. Head growth in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 2001;23 01:S227–S229. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neul J L, Kaufmann W E, Glaze D G et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(06):944–950. doi: 10.1002/ana.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olson H E, Tambunan D, LaCoursiere C et al. Mutations in epilepsy and intellectual disability genes in patients with features of Rett syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(09):2017–2025. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffjan S, Ibisler A, Tschentscher A, Dekomien G, Bidinost C, Rosa A L. WDR45 mutations in Rett (-like) syndrome and developmental delay: case report and an appraisal of the literature. Mol Cell Probes. 2016;30(01):44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayflick S J, Kruer M C, Gregory Aet al. b-Propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration: a new X-linked dominant disorder with brain iron accumulation Brain 2013136(Pt 6):1708–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauss K A, Puffenberger E G, Huentelman M J et al. Recessive symptomatic focal epilepsy and mutant contactin-associated protein-like 2. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1370–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]