Background:

Infection is a dreaded complication following 2-stage implant-based breast reconstruction that can prolong the reconstructive process and lead to loss of implant. This study aimed to characterize outcomes of reconstructions complicated by infection, identify patient and surgical factors associated with infection, and use these to develop an infection management algorithm.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective review of all consecutive implant-based breast reconstructions performed by the senior author (2006–2015) and collected data regarding patient demographics, medical history, operative variables, presence of other complications (necrosis, seroma, hematoma), and infection characteristics. Univariate and multivariate binomial logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent predictors of infection.

Results:

We captured 292 patients who underwent 469 breast reconstructions. In total, 14.1% (n = 66) of breasts were complicated by infection, 87.9% (n = 58) of those were admitted and given intravenous antibiotics, 80.3% (n = 53) of all infections were cleared after the first attempt, whereas the remaining recurred at least once. The most common outcome was explantation (40.9%; n = 27), followed by secondary implant insertion (21.2%; n = 14) and operative salvage (18.2%; n = 12). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that body mass index (P = 0.01), preoperative radiation (P = 0.02), necrosis (P < 0.001), seroma (P < 0.001), and hematoma (P = 0.03) were independent predictors of infection.

Conclusions:

We observed an overall infectious complication rate of 14.1%. Heavier patients and patients who received preoperative radiation were more likely to develop infectious complications, suggesting that closer monitoring of high risk patients can potentially minimize infectious complications. Further, more aggressive management may be warranted for patients whose operations are complicated by necrosis, seroma, or hematoma.

INTRODUCTION

In total, 102,000 breast reconstructions were performed in 2014 in the United States,1 making it the fifth most common reconstructive procedure.2 Of those, 72.5% were 2-stage implant-based reconstructions involving tissue expander (TE) and implant.1 Infection is a dreaded complication of 2-stage implant-based breast reconstruction, as it can lead to loss of the implant, a prolonged reconstructive process, compromised aesthetic outcomes, and delayed oncologic treatment. These potential sequelae of infection contribute to it being the leading cause of morbidity following postmastectomy breast reconstruction3–5 and add significant costs to the health-care system. Further, although reconstruction can reverse the emotional and psychological trauma of mastectomy, complications such as infection can jeopardize and undermine those psychosocial benefits.6

Rates of infection following implant-based breast reconstruction have been reported to range from 4.8% to 35.4%.6–11 This variability can be attributed in part to the lack of a standardized definition of infection, as it can range from a mild cellulitis requiring only oral antibiotics to severe foreign body infections requiring hospital admission, treatment with intravenous antibiotics, and even implant removal. Surgeons also employ different techniques to reduce the risk of infection, which also likely contribute to this variability. For example, our team’s protocol includes washing out the breast pocket with antibiotic irrigation and changing to a new pair of sterile gloves before placing the new TE or implant. For immediate reconstruction, after mastectomy and before reconstruction begins, the surgical area is re-prepped and redraped, betadine paint is placed in the breast pocket, and all sterile equipments (e.g., light handles, operating instruments) are replaced with a new sterile set. Further, although procedure type (expander/implant, pedicle transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous, and free transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap) has not been found to be correlated with overall complication rate, when complications are examined independently, patients receiving TE and implant-based reconstructions were more likely to develop infection than both those receiving other types of reconstructions3,6 and those receiving cosmetic breast implantation (2.0–2.5%).2

Given the devastating consequences of infection and the higher reported incidence of infection following implant-based breast reconstruction as compared with other types of reconstruction, this study aimed to characterize outcomes of reconstructions complicated by infection, identify patient characteristics and surgical factors associated with infection, and use these to develop an infection management algorithm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective review of all consecutive implant-based postmastectomy breast reconstructions performed by the senior author (G.K.L.) from 2006 to 2015. No further exclusion criteria were employed. The primary outcome variable of interest was infection, which we defined broadly as any clinically apparent infection of the breast. Mild infections such as cellulitis were included in our study.

We also collected and analyzed a variety of other variables, such as patient demographics [age, race, body mass index (BMI)], medical history (history of either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, hypertension, radiation therapy, tobacco use), operative variables (simple versus nipple-sparring mastectomy, immediate versus delayed reconstruction, TE placement, TE fill volume), presence of other complications (mastectomy skin flap necrosis, seroma, hematoma, open wound), and infection characteristics (type of infection, in-patient admission, intravenous antibiotic usage, outcome).

Radiation therapy was recorded as none, preoperative radiation, or postoperative radiation, and tobacco use was recorded as none, prior history, or active. Within our patient cohort, the 4 locations in which the TE were placed included total submuscular, under pectoralis with an acellular dermal matrix (ADM) sling, subcutaneous, or with a latissimus dorsi flap. Concurrent skin flap necrosis included both partial and full thickness necrosis, as we defined necrosis as any postoperative loss of mastectomy skin. The type of infection refers to whether it presented as cellulitis and/or a foreign body infection involving the TE or implant. Finally, outcomes were recorded as “cleared,” “recurrent infection,” “attempted operative salvage,” “explantation,” and/or “secondary TE insertion.” “Cleared” was defined as an infection eliminated after the first attempt, “recurrent infection” as one with any unsuccessful attempt to eliminate it, “attempted operative salvage” as a surgical attempt to eliminate the infection without removing the original implant, “explantation” as removal of the original implant, and “secondary TE insertion” as placement of a new implant after explantation. Notably, given the nonexclusive nature of these potential outcomes, multiple outcomes could be recorded for any given patient.

We obtained ethical approval from Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board before data collection. Data were stored and managed in Research Electronic Data Capture software (Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tenn.), which supports data capture within a secure database.12 Once collected, data were exported from Research Electronic Data Capture to RStudio software version 0.99.887 (RStudio, Boston, Mass.), where all statistical analyses were conducted. Each reconstructed breast was treated as an individual unit, and results are reported as mean ± SD. The unpaired 2-sample Student t test was used for continuous variables, and the Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Variables identified as significant in univariate analysis were included in a multivariate binomial logistic regression to determine independent predictors of infection. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

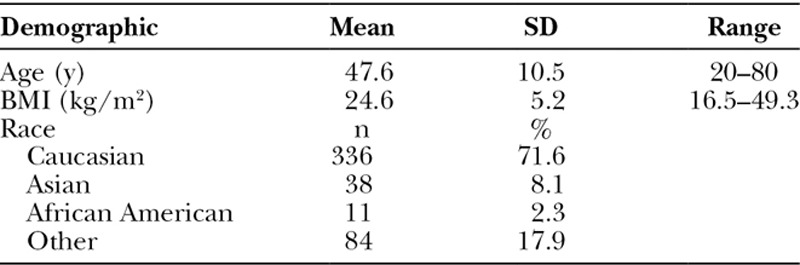

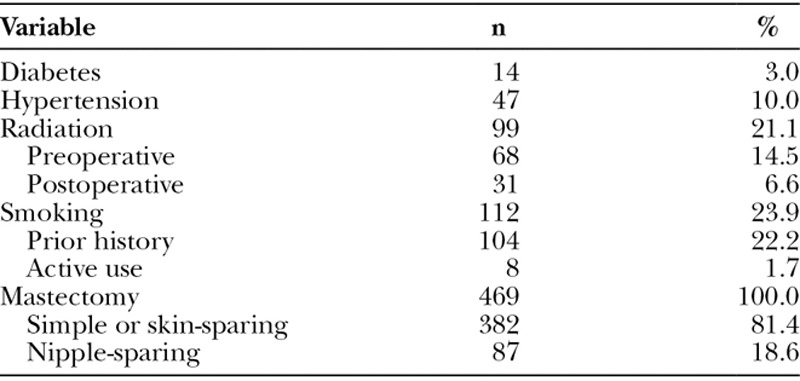

Our cohort consisted of 292 patients who had undergone implant-based breast reconstruction, for a total 469 breasts. The mean age was 47.6 ± 10.5 years, and the mean BMI was 24.6 ± 5.2 kg/m2 (Table 1). The majority of patients were Caucasian (71.6%; n = 336), followed by Asian (8.1%; n = 38), African American (2.3%; n = 11), or other/unknown (17.9%; n = 84). Comorbidities included diabetes (3.0%; n = 14), hypertension (10.0%; n = 47), and smoking history (23.9%; n = 112; Table 2). Of those with a smoking history, the mean pack-year was 13.5 and most had prior history (22.2%; n = 104) while a handful of patients were active smokers at the time of reconstruction (1.7%; n = 8). Fourteen percent (n = 68) of patients had received preoperative radiation therapy, 6.6% (n = 31) had received postoperative radiation therapy, and the remaining (78.9%; n = 370) had no history of radiation therapy. Patients had received either a simple or skin-sparing (81.4%; n = 382) or nipple-sparing mastectomy (18.6%; n = 87).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

Table 2.

Medical History

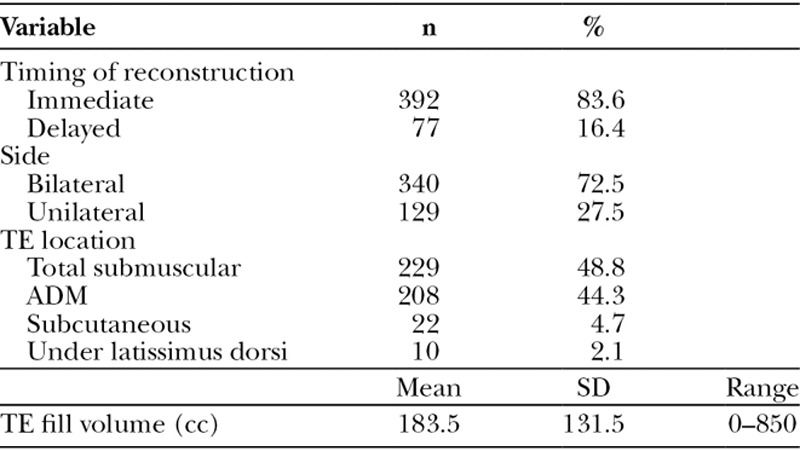

Of the 469 breasts, 27.5% (n = 129) were unilateral reconstructions, whereas 72.5% (n = 340) were bilateral (Table 3). Most reconstructions were performed immediately (83.6%; n = 392), whereas the remaining were delayed reconstructions. TEs were placed total submuscularly (48.8%; n = 229), with ADM (44.3%; n = 208), subcutaneously (4.7%; n = 22), or under a latissimus dorsi muscle flap (2.1%; n = 10). The mean TE fill volume was 183.5 ± 131.5 cc.

Table 3.

Reconstruction Factors

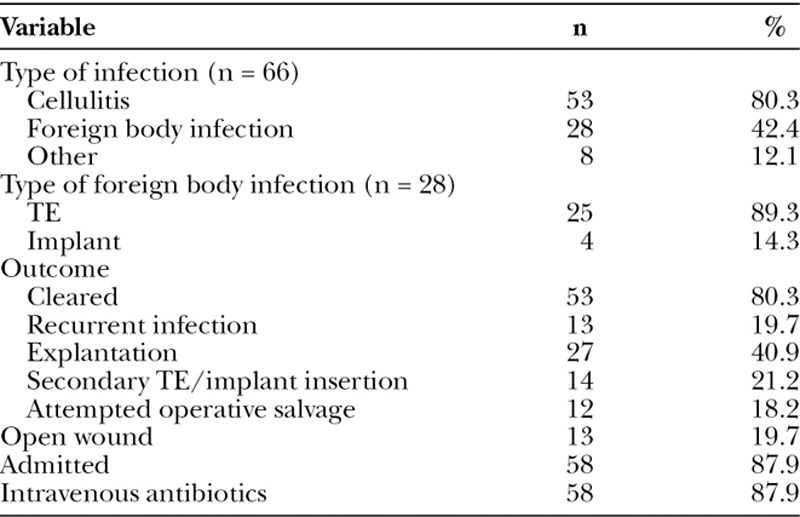

Fourteen percent (n = 66) of breasts or 18.5% (n = 54) of patients were affected by infection (Table 4). The TEs of these 66 infected reconstructions were most often placed with ADM (59.1%; n = 39), followed by total submuscularly (33.3%; n = 22) and subcutaneously (6.1%; n = 4). The 66 infected breasts developed cellulitis (80.3%; n = 53), foreign body infection (42.4%; n = 28), and/or some other type of infectious complication such as folliculitis or mastitis (12.1%; n = 8). Foreign body infections involved the TE (89.3%; n = 25) and/or permanent implant (14.3; n = 4), with 1 patient whose reconstruction was complicated by infection of both TE and implant. One-fifth (n = 13) of all infections involved an open wound with an exposed TE or implant. Eighty-eight percent (n = 58) of all patients with infected reconstructions were admitted to the hospital and given intravenous antibiotics. Four-fifths (n = 53) of infections were cleared after the first attempt, whereas the remaining recurred at least once. The most common outcome was explantation (40.9%; n = 27), followed by secondary TE or implant insertion (21.2%; n = 14) and/or attempted operative salvage (18.2%; n = 12). In addition to infection, reconstructions were also complicated by seroma (11.1%; n = 52), necrosis (8.1%; n = 38), and/or hematoma (3.8%; n = 18). No patients were lost to follow-up.

Table 4.

Infectious Characteristics

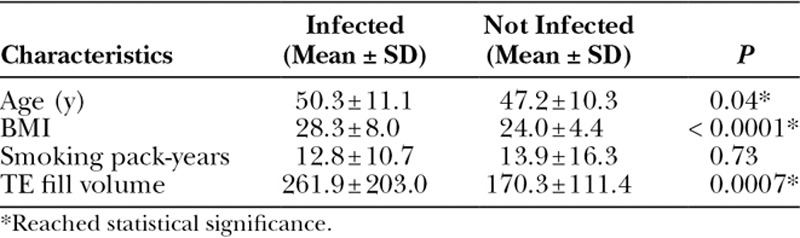

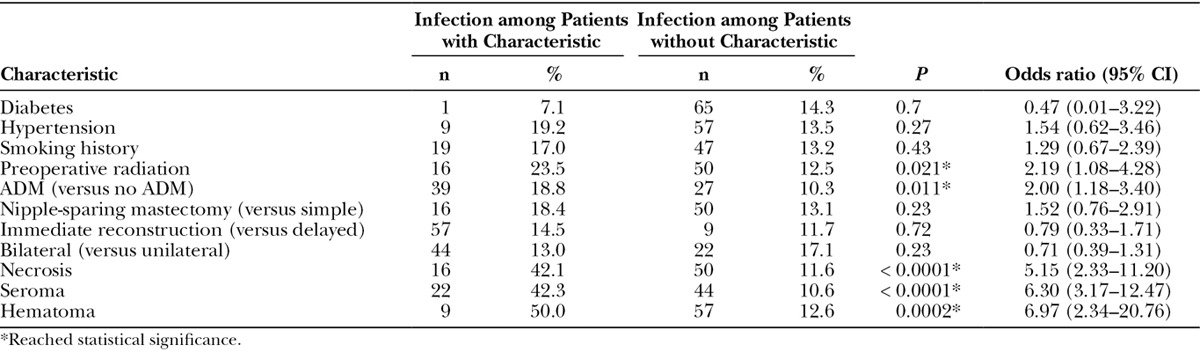

Univariate analysis demonstrated that older age (P < 0.05), greater BMI (P < 0.0001), and larger initial TE fill volume (P < 0.001) were associated with infection (Table 5). Patients who had received preoperative radiation (23.5% versus 12.5%; P < 0.05) and whose reconstructions utilized ADM (18.8% versus 10.3%; P < 0.05) were more likely to develop an infection (Table 6). Patients whose operations were also complicated by necrosis (42.1% versus 11.6%; P < 0.0001), seroma (42.3% versus 10.6%; P < 0.0000001), or hematoma (50.0% versus 12.6%; P < 0.001; Table 6) were more likely to have also developed an infection.

Table 5.

Potential Infection Risk Factors (Continuous Variables)

Table 6.

Potential Infection Risk Factors (Categorical Variables)

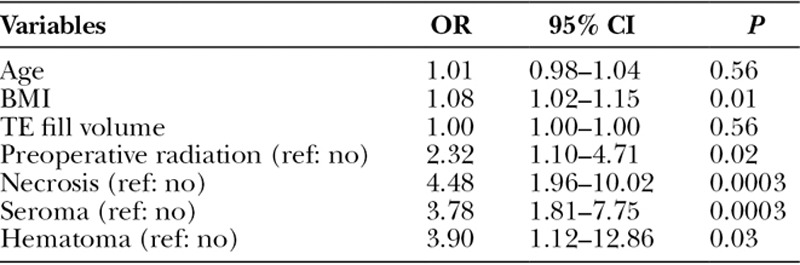

Multivariate logistic regression including risk factors identified as significant in univariate analysis revealed that BMI (odds ratio [OR], 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02–1.15; P = 0.01), preoperative radiation (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.10–4.71; P = 0.02), necrosis (OR, 4.48; 95% CI, 1.96–10.02; P < 0.001), seroma (OR, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.81–7.75; P < 0.001), and hematoma (OR, 3.90; 95% CI, 1.12–12.86; P = 0.03) were independent predictors of infection (Table 7). We found no association between infection and diabetes, hypertension, smoking history, postoperative radiation, type of mastectomy, timing of reconstruction, or whether the reconstruction was bilateral versus unilateral.

Table 7.

Multivariate Binomial Logistic Regression Analysis of Significant Risk Factors

CONCLUSIONS

Although mastectomy decreases patients’ quality of life,13 postmastectomy breast reconstruction has been shown to restore quality of life by providing patients with psychological, social, and functional benefits.14 Although risk of infection is an important consideration for all surgeons, it poses as an especially challenging complication for reconstructive surgeons, given that it can hinder the reconstructive process, delay oncologic treatments, and compromise the aesthetic outcome of the reconstruction. The higher reported incidence of infection following 2-stage, implant-based reconstruction as compared with other types of reconstructions and cosmetic implants,2,3,6 coupled with its increasing popularity as the reconstructive procedure of choice, suggests a need to identify patient and surgical factors that contribute to this procedure’s higher risk of infection. This can then guide clinical decision making so as to minimize infection risk, improve infection management, and ultimately optimize outcome.

In our cohort of postmastectomy patients who had received a TE and implant reconstruction, we observed an overall infectious complication rate of 14.1%, which falls within the lower end of the reported range of 4.8–35.4%.6–11 Most of our infections occurred during the tissue expansion period rather than after permanent implant placement, which is corroborated by the existing literature.15

We found that patients who were heavier, had a history of preoperative radiation, and developed noninfectious complications (necrosis, seroma, and hematoma) were more likely to develop an infection. However, older age, larger TE fill volume, diabetes, hypertension, smoking history, type of mastectomy, timing of reconstruction, or whether the reconstruction was bilateral versus unilateral were not independently associated with infection.

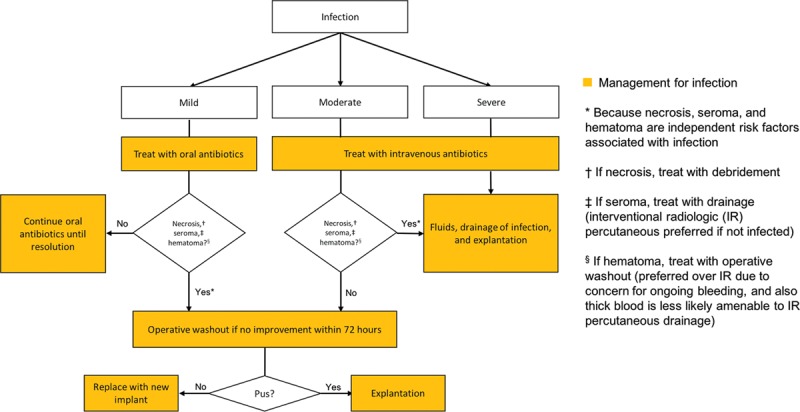

These findings suggest that surgeons should monitor patients with higher BMI and those who have received preoperative radiation more carefully for signs of infection and that extra caution and higher clinical suspicion is warranted for patients whose reconstructions are complicated by necrosis, seroma, and/or hematoma. Using these data, we propose an infection management algorithm (Fig. 1) that takes into consideration the higher likelihood of coexistent infection when the reconstruction is complicated by necrosis, seroma, and/or hematoma, whereby presence of one of these complications elevates the recommended level of management of the infection. Admittedly, this work does not report outcomes of the various treatment pathways presented in this algorithm, and thus this algorithm is presented in the discussion as an algorithm to be considered for future scientific investigation rather than as a definitive algorithm warranting changes in clinical practice.

Fig. 1.

Infection Management Algorithm: this algorithm for treating infections of varying severity recommends an elevation in level of management of the infection should the reconstruction also be complicated by necrosis, seroma, and/or hematoma (which should concurrently be appropriately treated).

Overall, there is a lack of consensus in the literature regarding the association between development of infection and various patient-level and surgical factors. For example, our finding that preoperative radiation was a predictor of infection was supported by other studies,11,16,17 whereas our finding that higher BMI and concurrent development of necrosis were predictors of infection was supported by some studies11,17 but not others.11,18 Similarly, we did not find immediate reconstruction, diabetes, smoking, or nipple-sparing mastectomy to be risk factors for developing infection, which was supported by certain studies18 but not others.6,9–11

There are several reasons that may contribute to the inconclusive data, such as differences in the outcome definition, cohorts examined, surgeon skill, and hospital practices. Thus, 1 limitation of our single-center, single-surgeon study is that our results are not necessarily generalizable to other hospitals. There is a need to conduct larger, multicenter, prospective studies or perhaps meta-analyses of existing studies to synthesize the available data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research Electronic Data Capture is supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through grant UL1 RR025744. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Spectrum is supported by NIH-NCATS-CTSA grant # UL1 TR001085.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Southern California Chapter of the American College of Surgeons, 2017, Santa Barbara, Calif.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics. Plastic surgery statistics report. 2014. Available at http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/news-resources/statistics/2014-statistics/plastic-surgery-statsitics-full-report.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2016.

- 2.Avraham T, Weichman KE, Wilson S, et al. Postoperative expansion is not a primary cause of infection in immediate breast reconstruction with tissue expanders. Breast J. 2015;21:501–507.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen MA, Lefta M, Dietz JR, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after major breast operation. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:326–335.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton JL, Bazakas A, Lee CN, et al. Once is not enough: withholding postoperative prophylactic antibiotics in prosthetic breast reconstruction is associated with an increased risk of infection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:495–502.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukhtar RA, Throckmorton AD, Alvarado MD, et al. Bacteriologic features of surgical site infections following breast surgery. Am J Surg. 2009;198:529–531.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderman AK, Wilkins EG, Kim HM, et al. Complications in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcome Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2265–2274.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franchelli S, Pesce M, Savaia S, et al. Clinical and microbiological characterization of late breast implant infections after reconstructive breast cancer surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2015;16:636–644.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis SH, Ruberg RL, Stevenson KB, et al. Independent risk factors for infection in tissue expander breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1790–1796.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill JL, Wong L, Kemper P, et al. Infectious complications associated with the use of acellular dermal matrix in implant-based bilateral breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68:432–434.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato H, Nakagami G, Iwahira Y, et al. Risk factors and risk scoring tool for infection during tissue expansion in tissue expander and implant breast reconstruction. Breast J. 2013;19:618–626.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reish RG, Damjanovic B, Austen WG, Jr, et al. Infection following implant-based reconstruction in 1952 consecutive breast reconstructions: salvage rates and predictors of success. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:1223–1230.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Harirchi I, et al. Quality of life in patients with breast cancer before and after diagnosis: an eighteen months follow-up study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkins EG, Cederna PS, Lowery JC, et al. Prospective analysis of psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: one-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcome Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1014–1025; discussion 1026.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hvilsom GB, Friis S, Frederiksen K, et al. The clinical course of immediate breast implant reconstruction after breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:1045–1052.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townley WA, Baluch N, Bagher S, et al. A single pre-operative antibiotic dose is as effective as continued antibiotic prophylaxis in implant-based breast reconstruction: a matched cohort study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:673–678.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selber JC, Wren JH, Garvey PB, et al. Critical evaluation of risk factors and early complications in 564 consecutive two-stage implant-based breast reconstructions using acellular dermal matrix at a single center. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:10–20.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyngold MM, Stutman RL, Khiabani KT, et al. Contributing variables to post mastectomy tissue expander infection. Breast J. 2012;18:351–356.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]