Abstract

Despite recent advances in radiotherapy, a majority of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer (PC) do not achieve objective responses due to the existence of intrinsic and acquired radioresistance. Identification of molecular mechanisms that compromise the efficacy of radiation therapy and targeting these pathways is paramount for improving radiation response in PC patients. In this review, we have summarized molecular mechanisms associated with the radio-resistant phenotype of PC. Briefly, we discuss the reversible and irreversible biological consequences of radiotherapy, such as DNA damage and DNA repair, mechanisms of cancer cell survival and radiation-induced apoptosis following radiotherapy. We further describe various small molecule inhibitors and molecular targeting agents currently being tested in preclinical and clinical studies as potential radiosensitizers for PC. Notably, we draw attention towards the confounding effects of cancer stem cells, immune system, and the tumor microenvironment in the context of PC radioresistance and radiosensitization. Finally, we discuss the need for examining selective radioprotectors in light of the emerging evidence on radiation toxicity to non-target tissue associated with PC radiotherapy.

1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is predicted to affect approximately 53,670 new individuals resulting in nearly 43,090 deaths in the year 2017, making it the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the U.S. [1]. The 5-year survival rate for PC is ~8%, with a median survival from the time of diagnosis ranging between 3 and 6 months, neither of which have shown much improvement over the last decades [1,2]. It was noted that the incidence and death rate of PC have increased by 1.2% and 0.4%, respectively, per year since 2000 [2]. Resection, the only curative treatment for PC, is limited to only 15–20% of cases and has little success, with only 20% of resected patients living more than five years [3]. Post-resection death is often the result of recurrences occurring both locally (33%–86%) and distantly (23%–92%) [4–7]. In an attempt to improve survival, both chemotherapy (CT) and radiotherapy (RT) are used either in conjunction with resection or as the sole treatments for the majority of 80–85% of PC patients who present with unresectable tumors [8].

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines version 2.2016, resectable PC is defined as disease with no evidence of distant disease, no tumor contact with celiac axis (CA), superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or common hepatic artery and/or no tumor contact with the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein (PV) or ≤ 180 degrees contact without vein contour irregularity. Unresectable PC is defined as distant metastatic disease or head/uncinated tumor contact with SMA/CA > 180 degrees or first jejunal SMA branch and body/tail tumor contact of >180 degrees with the SMA or CA or unreconstructable SMV/PV involvement. A borderline resectable disease is defined as those with disease status between resectable and unresectable status. In these potentially resectable patients, clinical studies have shown that a combination of CT and RT can convert the tumor to a resectable state in 8%–30% of cases [9–13]. Unfortunately, RT does not conclusively play a beneficial role in the treatment of PC, often being only mildly successful in a minority of cases for both resectable and unresectable disease. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the clinical trials that have investigated the efficacy of RT in the treatment of resectable and unresectable PCs. However, interpretability of many of these studies is limited due to lack of information in regard to radiation technique. It is important to note that the success of treatment can be greatly affected by the technique used as well as the treatment’s timing (i.e., pre-operative vs. post-operative). Further, many studies reported to be unsuccessful were based on the patient overall survival analysis only. However, as PC is very rarely curable, it may be more useful to consider the quality of life when evaluating the success of new treatments [14]. Ultimately, it appears that while some PC patients may respond to RT, the majority of PC patients are RT resistant. The main reason attributed to the ineffectiveness of RT in PC patients is the existence of intrinsic and acquired radioresistance. Several mechanisms associated with the disease have been proposed to contribute to this radioresistance of PC, including alterations in the DNA damage response, DNA repair machinery, and cell cycle checkpoint controls, as well as the hypoxic environment within the tumor and the activation of stellate cells leading to fibrosis.

Table 1.

Currently available clinical trials to base decisions of radiation therapy in resectable pancreatic cancer.

| Study/Trial | Treatment | N | OS | MS | Special considerations | Overall Conclusion | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GITSG (1987) | RTa + CT (Bolus 5-FU during RT and maintenance for 2 yrs) | 21 | 19% f | 21 mo | Negative surgical margins only; Excluded periampullary tumors, study closed early due to poor accrual and interim analysis detection of survival benefit | Survival benefit | [351] |

| Observation | 22 | 5%f | 10.9 mo | ||||

| EORTC 40891 Updated (2007) | RTa + CT (CI 5-FU during RT, no maintenance ) | 110 | 18%g | 1.8 yr | Periampullary and pancreatic head adenocarcino mas included, positive margins allowed | No survival benefit | [352] |

| Observation | 108 | 17% g | 1.6 yr | ||||

| ESPAC-1 (2004) | RTa + CT (bolus 5-FU during RT) | 73 | 7%f | 13.9 mo | Included ductal adenocarcinoma ofthe pancreas, positive margins allowed, physician choice of randomization arms, lack of quality assurance | CT-survival benefit RT-survival detriment | [353] |

| RTa + CT (bolus 5-FU during RT and 5-FU + folinic acid maintenance for 6 mo) | 72 | 13% f | 19.9 mo | ||||

| CT (5-FU + folinic acid maintenance for 6 mo) | 75 | 29% f | 21.6 mo | ||||

| Observation | 69 | 11% f | 16.9 mo | ||||

| RTOG 9704 (2011) | GEM then 5-FU/EBRT (50.4 Gy) then GEM | 221(187 )h | 22% | 20.5 mo | The overall and median survival are for head lesions only | On multivariate analysis, GEM arm trend toward improved survival (P = 0.08) | [354] |

| 5-FU then 5- FU/EBRT (50.4 Gy) then 5-FU | 230 (201)h | 18% | 17.1 mo | ||||

| Medicare- SEER (2003) | Resection alone | 241 | 29% e | 11.5 mo | Retrospective- Data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program | Adjuvant chemoradiother apy offers survival benefit | [355] |

| Resection + adjuvant chemoradiati on therapy (not further defined) | 155 | 41% e | 25.1 mo | ||||

| Johns Hopkins Hospital- | Resection alone | 509 | 16% f | 15.5 mo | Retrospective | Adjuvant chemoradiother apy offers survival benefit | [356] |

| Mayo Clinic collaborati ve study (2010) | Resection + 5-FU based CRT(median dose 50.4 Gy) | 583 | 22% f | 21.1 mo | |||

| Johns Hopkins (1997) | Standard therapy b | 99 | 80% d | 17.5 mo | Patients choose which therapy they wanted to receive. | EBRT offers a survival benefit; intensive therapy offered no survival benefit. | [357] |

| Intensive therapy c | 21 | 70% d | 21 mo | ||||

| No therapy | 53 | 54% d | 13.5 mo |

Abbreviation: GITSG = Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group; CI=continuous infusion; CT=chemotherapy; RT=radiotherapy; CRT= Chemoradiotherapy; EBRT=external beam radiation therapy; 5-Fu= 5 fluorouracil; mo=months N=number of patients; yrs=years; OS= Overall survival; MS= Median survival.

RT dose of 40 Gy delivered by split course with a 2-week break after 20 Gy. It is important to note that the use of split course therapy allows for accelerated repopulation of malignant cells and has been associated with decreased effectiveness in anal cancer, cervical cancer and head and neck cancer [207,358–360]. Also for many cancers a minimum dose of 50 Gy is required, and therefore the 40 Gy may be inadequate [361,362].

EBRT to pancreatic bed at 4000–4500cGy in combination with two 3-day courses of 5-FU followed by weekly bolus (500mg/m2 per day) for four months.

EBRT to pancreatic bed at 5040–5760cGy as well as prophylactic hepatic irradiation at 2340–2700cGy in combination with 5-FU infusion (200mg/m2 per day) and leucovorin (5mg/m2 per day) for 5 of 7 days for 4 months.

1 year survival rate.

3 year survival rate.

5 year survival rate.

10 year survival rate.

The number inside () is for pancreatic head.

Table 2.

Currently available clinical trials to base decisions of radiation therapy in non-resectable pancreatic cancer.

| Study/Trial | Treatment | N | OS | MS | Special considerations | Overall Conclusion | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GISTG (1981) | RTa + CT (bolus 5- FU+maintenance for 2 yrs) | 83 | 40% b | 10 mo | Other significant prognostic variables included pretreatment performance status and pretreatment CEA level | Survival benefit | [363] |

| RTc + CT (bolus 5-FU +maintenance for 2 yrs) | 86 | 40% b | 10 mo | ||||

| RTc | 25 | 10%b | 6 mo | ||||

| ECOG (1985) | RTa + CT (bolus 5-FU + maintenance) | 47 | 28%b | 8.3 mo | No survival benefit, Substantial ly greater toxicity RT +CT | [364] | |

| CT (5-FU) | 44 | 28%b | 8.2 mo | ||||

| GISTG (1988) | RT + CT (bolus 5-FU during RT; SMF maintenance for 2 yrs) | 22 | 41%b | 42 wk | Survival benefit | [365] | |

| CT (SMF for two yrs) | 21 | 19%b | 32 wk | ||||

| GERCOR(2007) | CT (GEM based combination) followed by RTd + CT (5-FU during RT) | 72 | 65.3 %b | 15 mo | Initial CT for three months, then decision to administer CRT or continue CT in non-progressive patients was the investigator’s choice. | Survival benefit | [366] |

| CT | 56 | 47.5 %b | 11.7 mo | ||||

| FFCD/SFRO (2008) | RTe+ CT (CI 5-FU+cisplatin during RT; maintenance GEMf) | 59 | 32% b | 8.6 mo | No distant metastasis, study closed early due do interim analysis showing survival detriment. | No survival benefit; Substantial ly greater toxicity RT+CT | [367] |

| GEM | 60 | 53% b | 13 mo | ||||

| ECOG (2011) | RTg +CT (GEM concurrent and maintenance) | 34 | 50%b | 11.1 mo | No distant metastasis, study closed early due to low patient accrual | Survival benefit; Substantial ly greater toxicity RT+CT | [319] |

| GEM | 37 | 32%b | 9.2 mo | ||||

| RTOG 0020 (2012) | RTg + CT (GEM and paclitaxel) | 91 | 46.2 %b | 11.5 mo | No distant metastasis | Maintenan ce R11577 is not effective and associated with broad range of toxicities | [249] |

| RTg + CT (GEM and paclitaxel) + maintenance R115777(tipifarn ib) | 94 | 34.0 %b | 8.9 mo | ||||

| LAP07 (2016) | CT (GEM with/without Erlotinib) | 136 | 24% b | 15.2 mo | CRT was associated with increased risk for grade 3 and 4 toxicity. | CRT is not superior to CT in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer who did not progress after 4 months of CT. | [237] |

| CT(GEM with/without Erlotinib) + CRT (50.4Gy with capecitabine) | 133 | 27% b | 16.5 mo |

Abbreviation: CI=continuous infusion; CT=chemotherapy; 5-Fu= 5 fluorouracil; GEM=gemcitabine; mo=months; n=number of patients; RT=radiotherapy; SMF= streptozocin, mitomycin, 5-FU; yrs=years.

RT dose of 40 Gy delivered by split course with a 2-week break after 20 Gy. It is important to note that the use of split course therapy allows for accelerated repopulation of malignant cells and has been associated with decreased effectiveness in anal cancer, cervical cancer and head and neck cancer [207,358–360]. Also for many cancers a minimum dose of 50 Gy is required, and therefore the 40 Gy may be inadequate [361,362].

1 year survival rate.

RT dose of 60 Gy delivered by split course with a 2-week break after 20Gy.

2 year survival rate.

RT dose 60 Gy given in 2 fractions.

RT dose of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions.

In this review, we aim to discuss and update current knowledge and understanding of the following topics: (i) various biological processes and changes that occur during and after PC radiotherapy, (ii) possible mechanisms associated with the emergence of PC radioresistance, and (iii) currently available radiosensitizers and radioprotectors for PC therapy. The radioprotectors are discussed not only as protectors of normal cells against radiation but also as enhancers enabling cancer cell killing (differential effect) when treated with conventional or Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT), as an additional benefit.

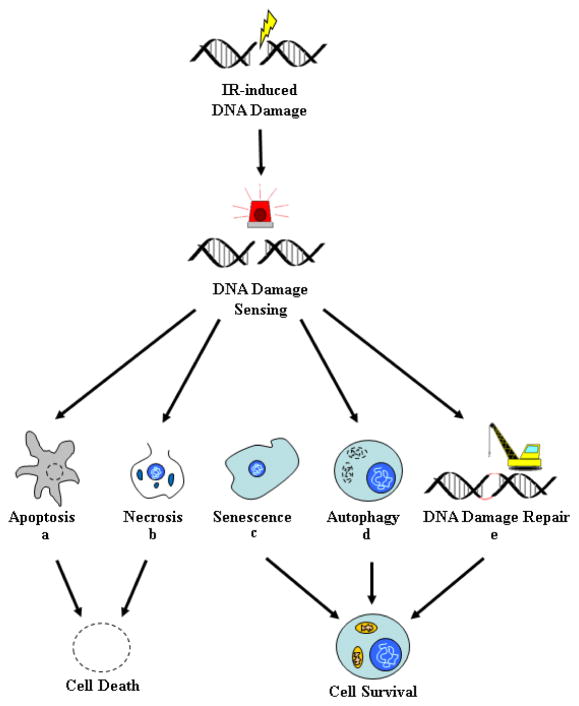

2. Molecular and cellular pathways associated with radiotherapy

When a cell is subjected to ionizing radiation (IR), DNA damage occurs as high energy photons interact with electrons resulting in the electron gaining part of their energy, according to the Compton effect [15]. These secondary electrons can then induce DNA damage, either directly by ionizing atoms within the DNA helix, or indirectly by first ionizing oxygen-containing molecules surrounding the DNA (e.g. water), to produce highly reactive free radical species, which in turn interact with the DNA resulting in damage. This indirect mechanism has been suggested to contribute to the majority of the DNA damage [16]. Ionizing radiation can damage the DNA strands and create a single strand break (SSB) or double strand break (DSB). The SSBs are rapidly repaired by members of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARP) family in conjunction with base excision repair (BER). A DSB probably form when two SSB are in close proximity, and these DSBs are far more difficult to repair and are therefore more toxic and lethal to cancer cells. In individual cells, exposure to radiation can elicit several possible responses: 1) transient response with survival, 2) senescence, 3) apoptosis, 4) necrosis, and 5) autophagy (Figure 1). In cells that survive irradiation, exposure to the insult induces a transient cell cycle arrest followed by DNA repair and survival. If the damage is too extensive, senescence, apoptosis, or necrosis will instead be induced to eliminate the damaged cells or at least limit their proliferative potential. Senescence is a viable state of permanent cell cycle arrest associated with the induction of markers of cellular aging. Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death involving caspase activation followed by DNA fragmentation. Cells undergoing necrosis exhibit changes consistent with the loss of plasma membrane integrity (rupture of the plasma membrane, mitochondrial swelling, disintegrated organelles, and atypical nucleus). Apoptosis and necrosis are irreversible processes that result in cell death and their ultimate removal by macrophages. Autophagy is a process by which cells consume their own components to either self-destruct or survive conditions of limiting nutrients. In cancer cells exposed to ionizing radiation, autophagy can lead to either cell death or survival, depending on the conditions.

Figure 1. Cellular Response to Ionizing Radiation.

In response to ionization radiation, a normal or cancer cell undergoes DNA damage in the form of either single strand breaks (SSB) or double strand breaks (DSB). DNA damage is sensed by the cell, resulting in progression down to any one of five biological outcomes: Apoptosis (a), Necrosis (b), Senescence (c), Autophagy (d), and/or DNA repair and survival (e). Genetic and epigenetic alterations in pathways regulating these responses can lead to radiation resistance. Following irradiation, the DNA breaks are recognized by ATM and ATR kinases, which in turn can either engage the apoptotic machinery or else protect the cell by activation of compensatory mechanisms (e.g. cell arrest and DNA repair). (a) Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death initiated by caspases and regulated by members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins (intrinsic pathway) or members of the death receptors (extrinsic pathway). Many cancer cells have lost their ability to undergo apoptosis, thereby making them less susceptible to IR-induced apoptosis. (b) Necrosis is a form of cell death characterized by disruptions of the plasma membrane, autolysis, and breakdown of cellular organelles. The cell’s fate to undergo necrosis versus apoptosis depends on the dose of radiation, with the higher doses inducing necrosis. (c) IR-induced DNA damage can also lead to the induction of senescence. Senescence is a viable state of permanent cell cycle arrest characterized by markers of cellular aging (e.g. SA-β-galactosidase expression, increased production of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), and decreased synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins). (d) Autophagy is a stress response characterized by the intracellular degradation of cytoplasmic constituents by the lysosomes. Autophagy can contribute to survival by the replacement of structures damaged by ROS, but the process can also contribute to cell death if autophagy is left uncontrolled. When a cell is irradiated, autophagosomes are formed that fuse with the lysosome to form autophagolysosomes. The autophagolysosomes auto-digest the damaged cell organelles and protein content for recycling. Autophagy may also be linked to radioresistance as this mechanism can be both pro-survival and pro-death depending on the conditions. (e) Activation of the ATM and ATR kinases can lead to activation of cell cycle checkpoints, formation of DNA damage foci, and recruitment of DNA repair machinery, which then act conjointly to protect the cells from the effects of radiation.

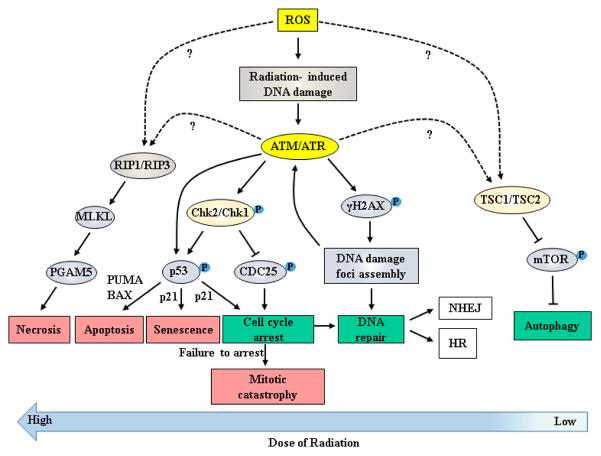

Cells exploit various responses to DNA damage and the associated biochemical pathways to protect themselves from the effects of radiation. Thus, alterations in components of these biological pathways can lead to the generation of radioresistance. Other biomolecular changes that can contribute to radioresistance include changes in tumor microenvironment leading to increased hypoxia at the tumor’s center. Autophagy may also be linked to radioresistance as this mechanism can be both pro-survival and pro-death depending on the system. Based on the current understanding, a model depicting the interplay of various biological processes involved during post-radiation response is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Biological consequences and its associated signaling mechanism(s) in response to the high and low levels of ionizing radiation.

Ionizing radiation leads to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which then react with cellular constituents to damage membranes, proteins, and genetic material. At the DNA level, the ROS create single- and double-stranded breaks in the genome (SSB, DSB). Detection of these breaks by surveillance systems results in the activation of the ATM and ATR kinases, which serve as central coordinators of the cellular response to IR. Activation of these kinases after IR and activation of their downstream effector kinases, the Chk2 and Chk1 kinases respectively, contributes to the induction of apoptosis (via activation of p53 and induction of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members PUMA and BAX), induction of senescence (at least in part through the induction of p21 by p53, along with delayed induction of p16), or else transient cell cycle arrest (via p53-mediated induction of p21 and phosphorylation/inactivation of the CDC25 phosphatases). The induction of senescence and cell cycle arrest protect from mitotic catastrophe by blocking entry of cells with DSB in either the S and M phases of the cell cycle. Activation of the ATM and ATR kinases also causes phosphorylation of the H2AX histone variant, which then acts as a seed for the formation of DNA damage foci. These foci serve to amplify and coordinate the DNA damage response in addition to facilitating the recruitment of the DNA repair machinery. Repair of DSB can then proceed through use of homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), depending on the phase of the cell cycle. Finally, through mechanisms that have not yet been completely elucidated, IR-induced ROS formation can also lead to necrosis via activation of the RIP1/RIP3 complex or else activation of autophagy via inhibition of the mTOR complex. This activation of autophagy can either promote or inhibit survival, depending on the conditions. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in the pathways that control these different responses can contribute to the development of radiation resistance.

While negligible information is known about the molecular mechanisms of radiation resistance in PC, radiation resistance has been the primary focus of clinical and radiobiological research in many other malignancies. Based on what is known about radiation resistance in other malignancies combined with the identification of mutated pathways in PC, herein we review some possible predictive pathways that can contribute to PC radioresistance.

3. DNA damage sensing and repair

The first step in a cell’s response to radiation is sensing the damage caused by that radiation and using these signals to activate the signaling cascades that will determine the nature of the cell’s response-whether it will be a transient cell cycle arrest, senescence, apoptosis, or necrosis, with or without activation of autophagy. Various proteins have been identified for their role in DNA damage sensing. SSBs created by ionizing radiation are immediately recognized by members of the PARP family, which PARsylate (addition of poly ADP-ribose) DNA-associated proteins in the vicinity of the break. These chains of poly (ADP-ribose) then serve to recruit components of the BER machinery which then can repair the break. Recognition of DSBs involves activation of the ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ATM and Rad3 related proteins) kinases, both of which are members of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-like kinase (PIKK) family [17–22]. By mechanisms that remain unclear, ATM is immediately recruited to and activated by a DSB. The DSB is eventually trimmed by exonucleases to produce a single-stranded 3′-overhang that can lead to the recruitment of the Rad17-replication factor C (Rad17-RFC)/9-1-1 complex and subsequent activation of ATR. Together, the two kinases initiate and coordinate the cellular response to DNA breaks [23–26] and activate pathways that protect the cells from the effects of IR. Some of these pathways block the cell cycle to allow DNA repair to take place while others stimulate the activity of the DNA repair machinery. Several pathways activated by ATM that are discussed in this review are illustrated in Figure 2. Germline mutations in the ATM gene, in a disorder such as ataxia-telangiectasia, have been associated with the hypersensitization of cells to radiation. Thus, patients harboring mutations in the ATM gene are predicted to be at higher risk of cancer incidence [27]. Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of ATM in cancer cells using AZD8055 can sensitize these cells to the effects of radiation, and this inhibitor is now being pursued for radiosensitization of solid tumors. ATM and ATR modulate pathways that control cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair machinery, senescence, autophagy, and apoptosis [27–34].

The success of radiation treatment is often determined by the balance between DNA damage and DNA repair [35–37]. If a cell is damaged beyond what can reasonably be repaired, it will most likely undergo programmed cell death. Besides these biological functions, if the extent of the damage is within the scope of what can be repaired, the cell will more often survive. Radiation induced DSBs are repaired by one of two mechanisms: homologous recombination (HR), and/or nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) [20–22,38–41], with NHEJ playing a dominant role while HR plays a supportive role [21,24,42–45]. However, HR has been more closely associated with radiosensitivity than NHEJ [46–48]. Iliakis et al., proposed that repair may in fact occur in a two-step process with NHEJ occurring first in order to restore continuity to the genome and HR occurring second at which point the actual sequence around the break is restored [49]. In addition, inhibition of NHEJ by DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) inhibitor NU7026 or by RNAi was shown to radiosensitize 8988T and Panc1 PC cells [50], suggesting that both DNA repair mechanisms deserve further exploration as pathways for radiosensitization. ATM has also been linked to DNA repair through a variety of molecules including Nijmegen breakage syndrome1 (NBS1), BRCA1, and CHK2 [51]. Interestingly, cells deficient of BRCA1 has been shown to be associated with a hypersensitivity to irradiation and defects in homologous recombination (HR) [51,52]. Likewise, loss of NBS1 in cells has been linked to radiosensitivity and defects not only in HR but also in nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) [51,53,54]. Also, F-Box and WD Repeat Domain Containing 7 (FBXW7) was shown to facilitate NHEJ repair by binding with XRCC4. Subsequently, polyubiquitination of XRCC4 via lysine 63 will enhance the chance of binding FBXW7-XRCC complex with the KU70/80 heterodimer scaffold to initiate NHEJ process. Inhibition of XRCC4 polyubiquitylation using pharmacological inhibitor MLN4924 also resulted in impairment of NHEJ repair. Thus, effective inhibition of NHEJ appears to be an alternative therapeutic strategy for PC patients having a defective HR repair pathway [55].

One downstream mechanism of ATM that is especially interesting in regards to radiation resistance results in the phosphorylation and activation of p53 [56–62]. ATM kinase activity results in the activation of Chk1 and Chk2 kinases, with both kinases phosphorylating p53 at Ser-20 [56,63–67]. Phosphorylated p53 disassociates from MDM [56,63,67–69], whose natural function is to target p53 for degradation, resulting in p53 accumulation [56,70,71]. Activated p53 is a DNA-binding protein that recognizes binding sites (comprising of four head-to-tail copies of the pentanucleotide PuPuPuC(A/G)) in the promoter of genes involved in cell cycle control, DNA repair, and regulation of apoptosis. Among these are genes encoding for the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and IGF-BP3 as well as the cell cycle regulators p21 and Gadd45 [56,59,65,72–80]. p21 is a potent and general inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) that control the G1/S and G2/M transitions of the cell cycle. This induction of p21 by p53 blocks cells at the G1/S and G2/M borders of the cell cycle in response to radiation. This transient cell cycle arrest allows DNA repair to take place before cells are allowed to re-enter the cell cycle to resume cell division. Thus, the p53 activation in response to IR can lead to either DNA repair and survival [81] or else apoptosis [82], depending on the type of cell or the extent of DNA damage.

4. Activation of cell cycle checkpoints

Radiotherapy impedes growth and viability, at least in part, by the generation of DSBs. If present at the time a cell is undergoing mitosis, these DSBs can wreak havoc and trigger mitotic catastrophe, a form of cell death. To block entry into mitosis and allow time for DNA repair to take place, cells with DSB activate the G1/S and G2/M cell cycle checkpoints [83]. For the purpose of radiotherapy, activation of these checkpoints is a double-edge sword. The checkpoints transiently inhibit tumor cell proliferation, but they also protect the cells from mitotic catastrophe and promote DNA repair. Invariably, a small number of tumor cells recover, deactivate the checkpoints, and give rise to clones of proliferating cells. A new concept in radiation biology is the notion that tumors can be radiosensitized by drugs that block the activation of the G2/M checkpoint. The G1 checkpoint is largely mediated through the activation of p53 by Chk1/2 followed by subsequent activation of p21 which mediates G1 arrest [25,84–86]. In many cancer cells, the G1/S checkpoint is already inactivated as a consequence of genetic alterations in components of this checkpoint, including p53 and p16.

The G2/M checkpoint is under the controlof Cdc2/cyclin B complex, whose activity is pre-requisite for the G2/M transition of the cell cycle [87]. In response to DSB, the ATM and then ATR kinases are activated. These kinases activate their respective downstream targets, the Chk2 and Chk1 kinases. These two kinases in turn phosphorylate and inactivate the Cdc25 dual-specificity phosphatases, whose activities are needed for dephosphorylation of Tyr15 of Cdc2, activation of the Cdc2/Cyclin B complex, and for the G2/M transition [88–90]. On the other hand, 14-3-3 binds to the phosphorylated forms of Cdc25, which contributes to arrest the cells at G2/M after ATM/ATR activation [91,92]. The net result is the inhibition of the Cdc2/cyclin B complex by DSB and the accumulation of the irradiated cells at G2 phase of the cell cycle. Cdc25c phosphorylation by Chk1/2 allows its binding to 14-3-3, which decreases its catalytic capabilities and results in its sequestration in the cytoplasm [93]. Importantly, 14-3-3σ is routinely found to be overexpressed in PC and has been directly associated with increased radioresistance [94,95].

Recently, we have identified the small GTPase Rac1 as one such key factor that regulates the activation of the checkpoint in response to ionizing radiation [96,97]. Rac1 is a member of the Rho family of small GTPases (guanosine triphosphatases) [98]. It is isoprenylated at the C-terminus and this isoprenyl group is thought to be responsible for recruitment of Rac1 to membranes, both plasma and internal membranes. Like other small GTPases, Rac1 exists in either as an active GTP-bound form or inactive GDP-bound state. In its active form, Rac1 associates with and activates its downstream targets, including the p21-activated kinases 1-3 (PAK1-3). In breast cancer cells, we have discovered that Rac1 is activated within 15 minutes following IR [96]. In both breast and PC cells, pre-incubation of the cells with Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 [99] abrogated activation of the G2/M checkpoint in response to IR. Similar outcomes were observed in cancer cells introduced with Rac1 siRNAs or infected with a dominant-negative mutant of Rac1 (Rac1-T17N) [96]. Interestingly, Rac1 inhibition also prevented activation of the ATM/Chk2 and ATR/Chk1 pathways in response to IR, as indicated by IP-kinase assays. Even more significantly, NSC23766 also sensitized the breast and PC cells to the effects of radiation [96,97]. While non-toxic to the unirradiated cells, NSC23766 synergized with radiation to drastically reduce the viability and clonogenicity of the cells.

5. Apoptosis

Some of the most commonly observed genetic dysregulations seen in aggressive cancer cells occur in apoptotic signaling pathways, that limit the effects of anticancer therapies, including radiation, which often rely on these pathways, to induce cell death [16,100–103]. Enhancing apoptotic cell death to improve therapeutic efficacy, can be accomplished in two ways: increasing pro-apoptotic genes and the pathways that control them or decreasing apoptotic inhibitors and their upstream pathways.

NF-κB, whose activity is often enhanced in response to radiation, has been shown to be constitutively activated in various cancers including PC, colon cancer, breast cancer, T-cell leukemia, lymphoma, and melanoma [104–107]. NF-κB is a major promoter of cell survival through the overexpression of its downstream targets (i.e. Bcl-XL, and BCL-2) which inhibit apoptosis. NF-κB can be activated by ATM [27] as well as by the p53-inducible death domain-containing protein (PIDD) [108] in response to DNA damage. Inhibition of NF-κB, by treatment with such molecules as genistein and indole-3-carbinol among others, has been shown to improve the efficacy of radiotherapy in various cancers [105,109–120]. While the exact mechanism(s) by which the inhibition of NF-κB improves treatment-associated cell death is not known, it has been suggested that it comes as a result of a greater number of cells undergoing apoptosis.

Bcl-2 family members are the master regulators of apoptosis and include pro-apoptotic (e.g. PUMA), anti-apoptotic (e.g. Bcl-2), and pore-forming effectors (BAX and BAK) and contain a BH3 domain (Bcl2 homology -3 domain). Bcl-2 was the first member discovered and is often considered an oncogene based on its anti-apoptotic function and overexpression in cancer [121]. On the other hand, inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) are also often overexpressed in cancer, essentially acting as an apoptotic “brake” and thus greatly reducing the efficacy of treatments such as radiation [104,113,122–126]. Numerous IAPs, such as cIAP2, XIAP, and Survivin are commonly found to be upregulated in PC [127]. Of note, based on the presence of one to three baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) and caspase activation recruitment (CARD) domain, IAPs can be divided into three classes: Class1 (XIAP, cIAP-1, cIAP-2, ML-IAP and ILP2); Class-2 (NAIP); and Class-3 (SURVIVIN and BRUCE) [125]. The importance of IAP’s apoptotic inhibition in radiation sensitivity is highlighted by the fact that chondrosarcomas, which overexpress BCL-2, BCL-XL, and XIAP, show significant radioresistance in vitro. Additionally, expression of IAPs increases with radiation treatment, while knockdown of IAPs by siRNA greatly increases radiosensitivity in a synergistic manner with radiation [128]. It is important to remember, however, that the pathways in which these proteins are involved are greatly interwoven with one another such that changing the expression of one molecule may not result in a change in overall apoptosis, as another pathway/molecule may be able to compensate. Therefore, many proteins are involved in the ultimate decision of cell survival or cell death [129].

The effects of IAPs are countered by IAP-antagonists including the second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (Smac) [126,130]. These molecules are activated during TNFα-dependent or TRAIL-induced apoptosis [131–137]. Synthetic mimetics of Smac have been shown to sensitize cancer cells, including those of breast cancer, multiple myeloma, glioblastoma, and ovarian cancer, to induced apoptotic cell death [131–133,137,138]. However, simply upregulating Smac may not be enough to enhance treatment efficacy as a recent study indicated that some IAPs inhibit IAP antagonists instead of directly inhibiting caspases [139].

Likewise, the role of p53 in apoptosis has been linked to radiation resistance. While many p53 mutations have been shown to affect cell cycle check point control, others have no effect on the cell cycle but instead solely affect the cell’s ability to undergo apoptosis [140]. Importantly, the majority of p53 mutations, which occur in approximately 50% of all human cancers, are point mutations in the DNA-binding domain, resulting in the overproduction of p53 protein that is unable to activate the Bax or PUMA promoter, key apoptosis inducers [72,140–143].

Another molecule that has been implicated in apoptosis is the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1). STAT1 is a transcription factor downstream of the interferon signaling pathway that has been shown to be overexpressed in various other malignancies such as head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma [144–146]. STAT1 is activated in response to IR, and this activation likely contributes to radioresistance [147,148]. While in some instances STAT1 can increase apoptosis through the activation of pro-apoptotic genes and suppression of anti-apoptotic proteins produced by the NF-κB pathway, its constitutive overexpression has also been shown to promote cell survival likely via the modulation of pathways activated by ATM, including Chk2 and NBS1 [148–150]. This overexpression of STAT1, which is often seen in cancers, is likely linked to their observed radioresistance as knockdown of STAT1 has been shown to increase radiosensitivity in the cells of squamous cell carcinoma [148] and in renal cell carcinoma [145]. Researchers have suggested that this radiosensitization is a result of the modulation of IL-6 and IL-8 as the expression of these cytokines greatly diminishes following the downregulation of STAT1 [144]. It is believed that these cytokines may act as prosurvival signals essentially saving the tumor cells from apoptosis. Additionally, IL-1, TNFα, VEGF, HGF, and IGF-1 have been found to be radioprotective in a variety of cancers, mostly thought to be due to their activations of the NF-κB or PI3K pathways [72].

Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) signaling, which promotes ATM stability, has been shown to be involved in cellular transformation, growth, motility, and apoptotic protection. IGF1R is overexpressed in radiation resistant melanoma and breast cancer cells and blocking its expression results in decreased cell proliferation and increased radiosensitivity. It is theorized that this radiomodulating effect is primarily due to the IGF1R’s anti-apoptotic activities [151]. Genetic blockade of IGF1R by expression of a truncated, dominant negative-IGF1R increased radiation-induced apoptosis in BxPC3 PC cells [152].

Cell stress, often seen in cancer due to hypoxia, acidic microenvironments, or suboptimal protein turnover, can cause activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) which, without cellular adaptation, can lead to apoptosis. However, adaptation can, and often does, occur; resulting in up or down-regulation of specific UPR pathways, ultimately leading to an upregulation of GRP78/BiP chaperones, which inhibit apoptosis and cause overall cytotoxic resistance [153]. Interestingly, UPR also leads to a significant increase in NF-κB activity, which further inhibits apoptosis [154].

In PC specifically, it has also been shown that regenerating gene 4 (REG4 ) acts as anti-apoptotic factor via the AKT pathway and its expression results in decreased radiosensitivity. Briefly, REG4 is a C-type lectin involved in the regulation of proliferation and differentiation of liver, pancreas, gastric and intestinal cells, discussed in detail in a recent review article [155]. The effect of REG4 on gemcitabine resistance, however, is modest, indicating that chemo-and radio-sensitivity may not fully coincide phenotypically or mechanistically. Importantly, REG4 is particularly promising as a predictor of PC radiosensitivity as it is found to be in higher levels in the sera of PC patients, with increased levels correlating with increased incidence of local recurrence after radiotherapy [156].

Of great importance in the context of the role of apoptosis dysregulation in radioresistance, however, is the understanding that radiosensitivity cannot be predicted solely depending on apoptosis or the intactness of apoptotic pathways. Studies that have used apoptosis as their sole benchmark for radiosensitivity have shown high rates of both false positive and false negative results. Additionally, as seen across multiple cancers, screening for apoptotic pathway mutations and apoptotic induction post-RT has shown limited predictive capabilities with regard to patient radioresponse and treatment outcome [72].

6. Autophagy

Autophagy, literally meaning ‘to eat oneself’, is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism that results in the large-scale lysosomal degradation of cellular contents including proteins, macromolecules, ribosomes and organelles. The role of autophagy in cancer cells can be both pro-survival and pro-death depending on the circumstances. In some instances, defective autophagy has been associated with malignant transformation of a normal cell and oncogenesis, therefore appearing to play a tumor suppressive role. In addition, in some cancer cells, as well as most normal cells, autophagy protects cells against cellular stress, thereby giving cells a chance to repair themselves instead of being automatically destined for apoptotic death upon damage [157–159]. Currently, the role of autophagy in radioresistance is both complicated and unclear, though many studies are underway to investigate its role in several types of cancer.

Autophagy, like apoptosis can also be a type of programmed cell death. In cells in which apoptosis is defective or repressed, often resulting in radiation resistance, autophagy provides another mechanism by which cell death can occur. Unfortunately, key autophagic proteins are also often underexpressed in cancers. Beclin1 (BECN1), an autophagy-related protein, is often deleted or underexpressed in cancers including prostate, breast, ovarian, colon, brain tumors, hepatocellular carcinomas and cervical cancers [160–168], suggesting that BECN1 along with its corresponding autophagic role may be repressed in some cancer cells [157]. Targeting of proteins involved in autophagy could therefore potentially offer therapeutic benefit in radiation-resistant cancer cells.

Previously, several research groups have demonstrated that inhibition of protein kinase C delta (PKCδ), Bcl-2, or tissue transglutaminase 2 (TGM2) in PC cells triggers autophagy-mediated cell death [157,169,170]. Another study found that IGF-II stimulation in combination with ionizing radiation increases cell death in pancreatic (AsPC-1, Panc-1) and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells under hypoxic conditions, most likely due to autophagy [171]. This effect, however, was not observed when cells were exposed to ionizing radiation alone. Importantly, IGF-II stimulation enhanced cell death only under hypoxic conditions, while under normoxic conditions promoted cell survival, underscoring the complexity of autophagy as both a pro-survival and pro-death mechanism, depending on both the type of cell and microenvironment. This is especially intriguing, as PC cells are radioresistant possibly due to inhibition of apoptosis. Activation of the pro-death function of autophagy could potentially be exploited in PC as an alternative means of inducing cell death in irradiated PC cells that may have lost the ability to undergo apoptosis.

However, autophagy can also act as a prosurvival mechanism in cancer cells, helping them withstand their highly hypoxic and acidic tumor microenvironments, ER stress, and therapy-induced cell stress and damage, including those caused by radiation. All these mechanisms and biological process associated with autophagy were discussed in detail in recent reviews articles [157,172–174]. Resistance to radiation has been hypothesized to be a result of the induction of autophagy leading to the sequestration of mitochondria damaged by the radiation; that protects the cells against apoptotic cell death. For example, in one study overexpression of FKBP51, a regulator of NF-κB, was associated with lower levels of apoptosis and higher levels of autophagy in melanoma cells after radiation treatment [175]. Further, it has been shown that incubation of PC cell lines with chloroquine leads to a post-irradiation cell death, which may at least in part be due to the inhibition of autophagy by chloroquine [176]. These studies suggest that, in at least some cases, autophagy acts as a prosurvival mechanism in response to radiation [175].

7. Genetic alterations affecting radioresponse of pancreatic cancer

In total, an average of 63 mutations in a core set of 12 biochemical pathways have been detected in high-throughput sequencing of PC specimens [177]. These mutations are in systems that control the response of the cells to the microenvironment, extracellular stimuli, intracellular signals, and cellular stresses. These mutations significantly alter the expression and activation of downstream molecules in their respective biochemical pathways, creating a cascading effect that serves to inhibit cell death and promote survival, repair, and proliferation via multiple mechanisms.

The earliest and most common mutations detected in PC occur at the 12th codon of the Kras gene, at which the naturally occurring glycine is commonly replaced with either an aspartic acid or valine. This mutation results in constitutive activation of Kras and continuous activation of its downstream effectors, most notably the PI3K/AKT pathway, Raf/MAPK/ERK pathway, and Rac1 GTPase [178,179]. Kras has been shown to contribute to chemotherapy resistance and radioresistance of PC. Treatment with Kras-targeted siRNA resulted in radiation sensitization in vitro and in xenografts of PC cell lines with oncogenic Kras mutations (Panc-1, ASPC-1, Capan-2, MiaPaCa-2, and PSN-1) [180]. ERK activation leads to increased proliferation and survival, as well as increased transcription of SHH and anti-apoptotic RSK (RPS6KA) protein [178]. AKT activation leads to increased VEGF, increased angiogenesis via NOS3, and activation of the NF-κB pathway, as well as inhibition of p53-mediated transcription, apoptosis, and autophagy.

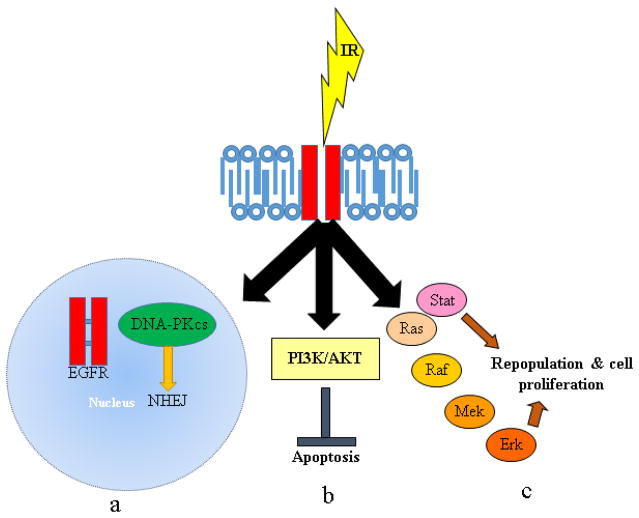

Among the many genetic alterations detected in PC, many contribute to inactivation of the G1/S cell cycle checkpoint. Among these genetic alterations are the loss of p53 and of p16, found in approximately 50% and 98% of PCs respectively [178,179,181]. Kras activation further contributes to the inactivation of this checkpoint by promoting the expression of D-type cyclins. The net effects are the absence of a G1/S cell cycle arrest in response to IR in PC cells. This lack of a G1/S response makes these cells more susceptible to abrogators of the G2/M checkpoint, as they are now more reliant on the activity of this checkpoint to promote cell cycle arrest and prevent mitotic catastrophe. But the loss of p53 in PC cells is a double-edge sword, as it can also contribute to decreased susceptibility of PC cells to apoptosis. The role of p53 in cell cycle arrest and DNA repair, likely through its induction of p21 and GADD45, has been linked to radiation sensitivity and resistance in various cancers. For example, overexpression of Bcr-Abl, the oncogenic form of c-Abl’s nuclear tyrosine kinase gene product implicated in the activation of p53, has been linked to radioresistance in growth factor-dependent lymphoma cells, likely a result of a prolonged G2/M cell cycle block that provides extra time for cells to repair DNA after radiation [72,182,183]. In a similar manner, loss of the G2/M checkpoint, which is partially controlled by p53, resulted in radiosensitization of lymphoma, carcinoma, and breast cancer cells. This observation is thought to occur because cells with DNA damage enter mitosis before they had a chance to repair the damage, thereby resulting in chromosome loss, mitotic catastrophe, and cell death [72,184,185]. Another pathway that shows frequent alterations in PC is the overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). This molecule is often overexpressed in carcinomas, including those of the lungs, colon, and breasts [186–188]. Studies have indicated that, in response to certain stimuli like radiation, EGFR translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), a kinase implicated in the repair of DSBs through NHEJ [20,189–201]. This mobilization of EGFR can also inhibit apoptosis through activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway as well as provide a survival advantage through repopulation and tumor progression as a result of the activation of the Ras/Raf/Mek/ERK and STAT signaling pathways [20,202–208]. Multiple pathways and mechanisms through which EGFR activation imparts radioresistance in cancer cells is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. EGFR-mediated responses to radiation.

Three distinct mechanisms contribute to the EGFR-mediated radioresistance in cancer cells (a) In response to irradiation, EGFR activity is induced in a ligand-independent manner which in turn leads to activation of downstream signaling which is primarily involved in the DNA repair mechanism. The putative nuclear localization sequence (NLS) present in the EGFR can be recognized by karyopherin further leading to nuclear import. In the nucleus, EGFR physically interacts with the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKCs) to regulate the non-homologous end joining DNA repair pathway. (b) As a consequence of IR, EGFR autophosphorylates and activates its corresponding downstream signaling cascades, such as PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/ERK pathways to regulate survival signaling (indirectly inhibiting apoptosis) and directly promoting proliferation of irradiated cells. (c) The phosphorylated tyrosine residues in EGFR can also function as an adaptor molecule for the JAK/STAT pathway.

A mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR in non-small cell lung carcinoma patients resulted in the failure of EGFR to enter into the nucleus and bind to DNA-PKcs, resulting in a decreased capacity to repair DSBs that strongly correlated with enhanced radiosensitivity [209,210]. Furthermore, studies have shown that cells treated with cetuximab, an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody, have greatly diminished DNA repair and survival, likely as a result of the sequestration of EGFR in the cytoplasm and its inability to interact with DNA-PKcs [200]. Cetuximab has been shown to effectively sensitize cells to the effects of IR in several cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancers [211–217], further suggesting the potential role of EGFR in the radiosensitization of cancer cells.

A third pathway often mutated in PC that has significant potential to enhance PC radioresistance is the Sonic hedgehog/Indian hedgehog (SHH/IHH) pathway. It is estimated that the rate of mutations in this pathway approaches 100% in PC, with 70% of PC tumors expressing 35-fold higher levels of SHH and IHH on an average [179,181]. Additionally, smoothened (SMO) is also found to be frequently overexpressed in PC [181]. Further, the SHH pathway results in activation of GLI and BMP2 along with increased IGF2 expression. Activated GLI serves to increased expression of VEGF, which promotes angiogenesis as well as increased activation of the AKT and NF-κB pathways. BMP2 activation increases PI3K activity and transcription of IGF-1. Increased levels of IGF-1 and IGF-2 interact with and activate IGFRs which, along with EGFRs, are overexpressed in 20–64% of PC tumors [178,179]. Activation of these receptors increases the activity of the PI3K, NF-κB, AKT, and JNK pathways along with stimulation of angiogenesis, generation of reactive oxygen species, and enhanced NO production via NOS2 and NOS3 activation. Increased NF-κB activity leads to increased apoptosis inhibition via increased transcription of XIAP, cIAP2, TNFAIP3 Interacting Protein 2 (TNIP2), and Bcl-2 [218]. Conversely, activation of the JNK pathway is pro-apoptotic, as it can lead to Bcl-2 and 14–3–3 inhibition, though these functions are likely appreciably tempered by the anti-apoptotic effects of the AKT pathway.

Upregulation of the cholecystokinin (CCK) B and gastrin receptor (CCKBR) is also commonly found in PC along with an increase in overall gastrin expression, resulting in increased activation of the CCKBR pathway [179]. This activation serves primarily to activate the PI3K pathway, further solidifying PI3K and its downstream pathways as a predominant mechanism for PC survival to cytotoxic stress. As multiple upstream pathways activate PI3K, inhibition of individual upstream molecules, such as EGFR, IGFR, and even Kras, may not deactivate PI3K due to compensatory effects.

Aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is also found in approximately 65% of PC tumors [179,181] further contributing to redundancy in the anti-apoptotic mechanisms present in PC. TGFβ signaling is also affected by mutations commonly found in PC, namely by mutations in TGFBR1, TGFBR2, and SMAD4 occurring in 4%, 1%, and 50% of PCs respectively [181]. While these mutations result in decreased TGFβ-mediated growth inhibition, they also have the potential to exert pro-apoptotic effects by causing decreased Bcl-2 levels. These pro-death effects, however, are likely compensated for directly by NF-κB mediated upregulation of Bcl-2 and indirectly by AKT mediated activation of 14-3-3 and inhibition of BAD. To obtain a global perspective of the genes modulated in response to radiation across the cancers we have listed a few metabolic and non-metabolic genes differentially expressed and associated with radioresistance of pancreatic and other cancers in Table 3.

Table 3.

Radiation responsive differential gene expression profile and their associated signaling pathways in multiple cancers.

| Cancer type | Cell lines | Experimental method | Genes modulated | Associated Pathways and biological functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic cancer | Panc-1 and BxPc3 | cDNA micro array | FDPS, ACAT2, AG2, CLDN7, DHCR7, ELFN2, FASN, SC4MOL, SIX6, SLC12A2, and SQLE. | Cholesterol biosynthesis pathway | [311] |

| PK-1, PK-8, PK-9, T3M4, and MiaPaCa2 | cDNA micro array | AREG, MAPKAPK2, RGN, ANG-2, caspases-8, LRAT and CLCA-1. | Growth factor, cell cycle check point, angiogenesis, apoptosis, retinoid cycle, electron transport. | [370] | |

| Nasopharyngeal cancer | CNE2 | Proteomics | GRP78, Mn- SOD, 14-3-3σ, Maspin. | Cell survival, scavenging reactive oxygen species, Cell cycle, cell growth, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis. | [371] |

| Esophageal Cancer | TE-2R, TE-9R, TE-13R, and KYSE-170R | cDNA micro array | ICEBERG, BIRC2, COX-2, CD73, PLAU, CYP1A1, GRP58, and ERP70, PRKCZ, ROR2,SGK, CASP6, CDH1, CDH3, PCDH9, MLL3, PRKCBP1, CDK6 and CCNA2. | Inflammation, apoptosis, DNA metabolism, cell growth, electron transport chain, apoptosis, cell adhesion, transcription and cell cycle. | [372] |

| Lung cancer | Anip973 vs Anip973R | cDNA micro array | DDB2, LOX, CDH2, CRYAB, GBP-1, CD83, TNNC1. | DNA damage repair, extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, apoptosis, angiogenesis, immune response, calcium signaling | [373] |

| A549 vs A549R | RNA Seq | SESN2, FN1, TRAF4, CDKN1A, COX-2, DDB2 and FDXR. | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition, migration and inflammatory response. | [374] | |

| Prostate cancer | PC3 vs LNCaP | RNAseq | BRCA1, RAD51, FANCG, MCM7, CDC6 and ORC1. | DNA repair and replication. | [375] |

| PC3 | cDNA micro array | CCDC88A, ROCK1, NEXN, FN1, MYH10 and MYH9 | Cell cycle and Cell motility | [376] | |

| Prostate cancer and colon cancer | PC3 vs Caco-2 | RT-PCR | CCDC88A, FN1, MYH9 and ROCK1 | Cell motility | [377] |

Note: Bold letters represents differentially upregulated genes and their associated biological pathways whereas, un-bold letters represents down regulated genes and their corresponding pathways.

8. Previously tested radiosensitizers in pancreatic cancer

With the significant complexity that the aforementioned genetic alterations provide, research toward clinically useful radiosensitizers in PC has been slow and challenging. To date, the primary focus of radiosenisitization research has been on identifyimg molecular target (s) and methodologie (s) to enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiation as compared to normal cells. These methods, though, designed to prevent unacceptable increases in toxicity while improving therapeutic efficacy, significantly restrict the available avenues by which radiosensitization can be pursued. Additionally, with the dawn of stereotactic irradiation, it is arguable that such criteria may no longer be necessary as significant radiation doses can be avoided altogether for the vast majority of the healthy tissue in the tumor’s vicinity. However, despite advancements in both radiation methods and knowledge about the effects of IR on PC at both cellular and tissue levels, no specific radiosensitizers currently exist for PC.

Instead, radiosensitization of PC is currently accomplished by the use of concurrent chemotherapy, often with either 5-FU or gemcitabine. While chemoradiotherapy (CRT) was initially developed as an attempt to prevent/eliminate systemic metastatic growth during localized radiotherapy, it was found that chemotherapeutics and IR could have a synergistic effect on local tumor control [16]. This synergy, however, is inconsistent among different chemotherapeutics, even among the same class of drugs, and their underlying mechanisms are often unclear. This scenario applies in particular to the case of 5-FU and gemcitabine, in which modest and significant synergy with IR is found, respectively [16]. The reasons for this difference, despite both drugs being antimetabolites with similar mechanisms of action, remain unknown, and as such cannot be exploited for future improvement of radiosensitization efficacy. One notable exception to this is that gemcitabine has been found to inhibit ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) while 5-FU does not, the potential importance of which may be linked to the role of RNR in DNA repair [219]. Additionally, CRT with gemcitabine has shown significant increases in treatment toxicity, thus limiting its universal clinical use [16].

Several other methods for radiosensitization have been attempted for PC and other cancers. While a majority of approaches showed promise in both in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies, most ultimately failed to provide significant radiosensitization in clinical studies. However, identifying and understanding the underlying mechanisms that contributed to the failure of these methods, may provide greater insights for the development of successful radiosensitization strategies.

One of the first methods examined for potential radiosensitization was through treatment with halogenated pyrimidines. These nucleoside analogs, consisting of deoxycytidine, deoxyuridine or thymidine with a methyl group replaced by Cl, Br, or I, are incorporated into the DNA of a dividing cell, thus weakening it and increasing the amount of DNA damage occurring from a given dose of IR [16]. Through this mechanism, these halogenated pyrimidines have differential affinity for cancer cells due to their rapid proliferation rates. To significantly enhance the DNA damaging effect of radiation via these methods, however, many halogenated pyrimidines must be incorporated into each DNA strand, thus necessitating the presence of the altered pyrimidines at the tumor for multiple cell generations. Additionally, systemic treatment with halogenated pyrimidines is precluded by the ability of the liver to rapidly dehalogenate molecules, thereby necessitating delivery directly to the tumoral arterial blood supply [16]. While this is a significant hindrance to the utility of halogenated pyrimidines in the majority of cancers, it is particularly challenging in PC as the tumor is located deep in the abdomen, making access to the tumor both difficult and invasive. Further, hypovascular nature and high interstitial pressure encountered in PC make long-term intra-arterial infusions impractical.

The importance of tumor hypoxia in radioresistance has long been recognized and has provided an additional avenue in the pursuit of tumor radiosensitization. Initially, the majority of studies examining the ability of tumor oxygen status to allow for radiosensitization focused on increasing tumor oxygenation. Attempts at accomplishing this, however, either through subjecting the patient to hyperbaric oxygen or through a blood transfusion before RT, have met with limited success in most cancers and been largely unsuccessful in PC [16]. The likely cause for this failure is that low tumor oxygenation, especially that of PC, is often an artifact of inadequate and imperfect tumor vasculature, extensive desmoplasia, and rapid tumor growth, not anemia or poor blood-oxygen saturation. As such, the efficiency of such methods to practically increase tumor oxygenation is minimal.

Alternatively, methods seeking replacement of the radioenhancing effects of oxygen with other molecules that are more readily absorbed/concentrated in hypoxic tissues has also been attempted. These oxygen substitutes, primarily nitroimidazoles and related compounds, have exhibited some degree of clinical success for radiosensitization, though their actual utility in a therapeutic setting remains unclear [16,220]. These compounds enter the cytoplasm through the plasma membrane and chemically produce the same radical-stabilizing and DNA damage-fixing effects that oxygen allows. However, unlike oxygen, nitroimidazoles are metabolized slowly, allowing them to diffuse more than 200 μm away from capillaries [16,220]. As such, a deep penetration into the hypoxic portions of tumors is allowed, theoretically leading to great improvement in the ability of these oxygen substitutes to radiosensitize hypoxic tumors. One of the first oxygen substitutes to be tested in depth was misonidazole, which showed significant radiosensitizing effects in vitro where 10mM treatment allowed almost equal IR-induced cell killing in hypoxic and normoxic cells. In clinical trials, however, pre/co-treatment with misonidazole and IR failed to show any improvement in treatment response as compared to IR alone except for one trial in which a modest improvement was found in a small subset of patients with pharyngeal cancer [16]. This failure may be explained by the dose-limiting neurotoxicity (both peripheral and central) of the drug that prevented administration of doses at which optimal plasma concentration could be achieved. To address these problems of dose limitation, a similar compound, etanidazole, was also tested in clinical trials as an oxygen substitute radiosensitizer. In vitro etanidazole was found to be as potent radiosensitizer as misonidazole, but with a shorter half-life and lower partition coefficient in vivo, preventing it from crossing the blood-brain barrier and limiting its ability to penetrate peripheral nerves and thus reducing its neurotoxicity. These alterations allowed etanidazole to be administered at much greater dosage, but in clinical testing, it still failed to show improvement in RT efficacy and these aspects have been reviewed in detail elsewhere [16]. Interestingly, another nitroimidazole, nimorazole, that was shown to have decreased in vitro radiosensitizing efficiency as compared to the other tested nitroimidazoles, but also a significantly reduced toxicity profile, has provided more promising clinical results. Nimorazole significantly enhanced both local control and survival in irradiated patients with head and neck cancer, but to date has not been tested in cancers of other sites [16]. Another nitroimidazole, doranidazole (PR-350) has been tested in PC cells in vitro and in vivo [221–224], and has been evaluated in a Phase III trial (n = 46 patients) in combination with intraoperative radiotherapy for locally advanced PC in a Japanese cohort [225,226]. No difference in one-year survival was seen [226], but 3-year survival was significantly increased with the combination [225].

These failures, and limited successes, illustrate several important points with regard to radioresistance and radiosensitization in PC, as well as in cancer in general. First, and perhaps most importantly, results from the in vitro and limited in vivo testing available in radiation research are poor indicators of clinical efficacy of radiosensitizers. Additional factors beyond those of just the cancerous cells must be considered for all potential radiosensitizers, such as practicality of implementation, metabolism, the interplay of the tumor microenvironment and surrounding tissues with the sensitizer’s penetrative abilities into the tumor, and the toxicity that such a sensitizer will elicit. Unfortunately, most of these issues cannot currently be addressed using models available to bench/animal researchers and thus only come to light upon clinical testing, but can simultaneously subject the patients to harm through unforeseen toxicities, as well as cause significant expense for an ultimately doomed treatment. These difficulties highlight the need for novel research models to better evaluate potential radiosensitizers prior to implementation in clinical trials. Opportunities for such a model may exist through the use of in situ irradiation experiments using transgenic murine models, and thus development of irradiation models of this nature, though undoubtedly difficult, should be pursued as rapidly as possible.

9. Promising molecular targeting agents as radiosensitizers in pancreatic cancer therapy

Despite the lack of past success in the development of PC radiosensitizers, multiple novel add-on pharmaceuticals showing promising enhancement of PC radioresponse are currently at various stages of testing, both clinical and preclinical [227]. Unfortunately, no new preclinical techniques have been developed with which to test the efficacy of these potential radiotherapeutic modulators, resulting in reliance on evidence for warranting clinical testing that has previously been shown to poorly translate bench results to clinical worth. However, while most of these novel potential radiosensitizers will likely fail, their breadth and number provide the greatest hope to date that a clinically viable and practical PC radiosensitizer will be found.

Of the potential radiosensitizing targets currently under study, the most extensively tested is modulation of EGFR. EGFR inhibition is currently an FDA-approved treatment for PC, though it provides only negligible benefit in the form of a 2-week improvement in overall survival time [228]. Currently, focus is shifting from its use as monotherapy to an adjunct treatment to improve efficacy of other therapeutic modalities. For the purposes of PC radiosensitization, EGFR inhibition has been evaluated using both anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab or small molecule inhibitors erlotinib and gefitinib. The results of these studies have been generally positive in the preclinical setting, though with notable exceptions. In at least one preclinical study, cetuximab was shown to elicit no beneficial additive or synergistic effects with IR [179]. Another, more recent study suggested that erlotinib only radiosensitizes PC cell lines containing wild-type Kras [229]. These studies are in concordant with an earlierstudy showing that both erlotinib and cetuximab have the capacity to increase cell death both in vitro and in vivo in irradiated BxPC3 cells, which express wild-type Kras [230]. A complication to the interpretation of this study, however, is the fact that all experiments with positive results utilized concurrent treatment with gemcitabine as well, potentiating that the increase in cytotoxicity after EGFR inhibition was in fact due to chemosensitization and not an increase in IR efficacy. The probability of this being the case is increased when it is considered that erlotinib plus gemcitabine results in increased cytotoxicity over gemcitabine alone while erlotinib plus IR lead to no enhancement in cell death [230]. Many other studies, however, have demonstrated positive radiosensitizing effects of EGFR inhibition in PC, both concurrent with and independent of treatment with chemotherapeutics, through multiple mechanisms including enhancement of the G1 checkpoint, release of apoptotic inhibition, and anti-angiogenesis [228].

Despite the conflicts in preclinical results, EGFR inhibition in the context of radiotherapy has been, and continues to be, the subject of many clinical trials, the majority of which are well summarized by Chang and Saif in their 2009 review [228]. Unsurprisingly, as with the preclinical studies, phase II trials testing EGFR inhibition as a method for radiosensitization have yielded conflicting results leading to confusion regarding the utility and future design of anti-EGFR therapies in the context of improving radiosensitization of PC. To date, some of the most encouraging outcomes for PC have been obtained from clinical trial testing EGFR inhibition in conjunction with chemoradiotherapy. The trial involved pretreatment with cetuximab (400 mg/m2 dl) prior to IR followed by concurrent cetuximab administration (250 mg/m2 dl) with chemoradiation (54Gy IR + gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2/week for 4 weeks)) [231]. In this trial, which is also to date the largest such trial conducted, comprising 66 locally advanced PC patients, the 1-year survival was 61% and the 2-year survival was 20% with a median survival of 15 months, which is a significant improvement over the historical median survival time for locally advanced PC patients undergoing CRT of 11 months [228,231]. Another trial using erlotinib and gemcitabine concurrent with IR showed a median survival of almost 19 months in 20 locally advanced PC patients [232]. Other trials, however, have not been so favorable. Maurel et al., achieved a median survival of 7.5 months using gefitinib with gemcitabine and IR [233]. In the three treatment arms described by Demols et al., in another trial, median survival ranged from 3.7 to 10.7 months, indicating a treatment disadvantage despite 45% of the patients showing at least a partial response to various treatment regimens [234]. Although the majority of patients in these clinical trials were able to complete treatment, toxicity appeared to be a significant concern, with the majority of trials showing Grade 3–4 GI toxicity occurring in 15–60% of patients [228]. Additionally, dose-limiting toxicities were observed in 0–60% of patients [228,235,236]. Results were recently reported from the international Phase III LAP 07 study comparing capecitabine-based chemoradiation with gemcitabine-based therapy for non-progressive locally advanced PC, following four months of gemcitabine-based therapy with or without erlotinib. The results showed that standard chemoradiation improves local control but not overall survival, and there was no change in the overall survival with gemcitabine compared to gemcitabine plus erlotinib used as maintenance settings [237]. Treatment with erlotinib concurrent with RT and various chemotherapeutics is the subject of a single Phase III clinical trial (RTOG-0848) that is currently recruiting patients. This study will specifically evaluate the effect of gemcitabine +/− erlotinib followed by gemcitabine +/− erlotinib +/− IR + 5-FU/capecitabine. The results of this trial will allow the community to determine the true clinical applicability of EGFR inhibition, at least with erlotinib, in the context of CRT in PC. Interestingly, multiple studies have shown the preclinical and clinical efficacy of second generation pan-EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as afatinib and dacomitinib in breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, glioblastoma, head and neck cancer, and PC [238–240]. This class of TKI’s exhibit irreversible binding to the ATP binding pocket of the tyrosine kinase domain of all the EGFR family members thereby blocking the tyrosine kinase activity. In 2013, the USFDA approved afatinib as a first-line therapy for patients with metastatic NSCLC [241]. Recently, afatinib has been reported to radiosensitize PC cells by inhibiting the EGFR family member-mediated AKT phosphorylation and causing mitotic catastrophe-mediated cell death. However, unlike previous studies with erlotinib and cetuximab [230], afatinib showed similar radiosensitization potential in both Kras wild-type and Kras mutant harboring PC cells [242].

Beyond EGFR modulation, the agent that has been evaluated for PC radiosensitization is nelfinavir, a HIV protease inhibitor with potentially beneficial off-target effects. While designed for action against HIV proteases, nelfinavir, like most protease inhibitors, is promiscuous, decreasing human proteosome activities as well [243]. The resulting increase in misfolded proteins has been found to be sufficient to lead to an unfolded protein response (UPR) within the cell, causing many downstream events including phosphorylation of eIF2α. This phosphorylation acts as a signal for the cell to globally decrease protein synthesis as well as upregulate and activate GADD45 [243]. Activated GADD45 interacts with and activates the phosphatase PP1, leading to dephosphorylation of AKT and ultimately to radiosensitization [229,243,244]. In vitro, this radiosensitizing effect has been found to increase IR-induced PC cell death by approximately 40% with even greater effects seen in vivo, postulated to be due to vascular alterations within the tumor. Nelfinavir has been evaluated in several clinical trials in multiple cancer types both as a monotherapy and as an adjunct agent. Two clinical trials, one published and one completing, have attempted to analyze the additive/synergistic effects of nelfinavir with IR in PC [245]. The first trial, a Phase-I study testing a combination of nelfinavir, gemcitabine (at 2 separate dose levels with equal patient distribution in each), and IR (50.4Gy with a boost to 59.4Gy) in 12 patients with locally advanced PC, showed encouraging results. Of the 10 patients who were able to complete the therapeutic regimen, 6 were downstaged to resectability. Further, the objective response rates were found to be 50% and 70% based on CT and PET assessment, respectively [245]. Importantly, with this regimen, no dose limiting toxicities were observed. The second trial, a Phase-I currently concluding at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (data not yet published) is showing a similarly mild toxicity profile for nelfinavir added to stereotactic respiratory gated CRT, though with relatively less treatment efficacy.

Another avenue for radiosensitizing PC currently undergoing clinical testing is the inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs). Preclinical studies using HDAC inhibitors (HDACIs) on PC and various other cancers have demonstrated the role of HDACs in response to and repair of DNA damage [246]. By increasing the amount of radiation-induced DNA damage and slowing DNA repair, along with modulation of p53, pRB, cell cycle regulators, as well as regulators of apoptosis and cell proliferation, HDACIs radiosensitize cancer cells. One preclinical study in PC specifically demonstrated that treatment with vorinostat, a hydroxamic acid HDACI, significantly reduces post-IR colony survival in several PC cell lines, leading to 40–60% enhancement in cell death post-IR as compared to cells treated with IR alone [247]. Interestingly, IR plus vorinostat induced no greater apoptosis than vorinostat alone (p=0.69). Consistent with previous studies in other cancers, mechanistically vorinostat was found to delay DNA repair post-IR (via inhibition of both NHEJ and HR) as well as inhibit constitutive and IR-induced NF-κB and EGFR signaling pathways, [247]. Paradoxically, studies have also demonstrated the ability of HDACIs to radioprotect healthy tissues, particularly cutaneous, intestinal, and bone marrow tissues, both in vitro and in vivo [246]. With this preclinical foundation, two clinical trials, one published and one with unknown status, have tested the effects of HDACIs with CRT in PC [248]. The first trial, a Phase-I study testing a combination of vorinostat (dose escalation up to 400 mg), capecitabine, and IR (30Gy in 10 fractions) in 21 patients with non-metastatic PC, showed the combination was well tolerated, although three patients experienced dose limiting toxicities, including two gastrointestinal toxicities and one thrombocytopenia. The Intergroup definition of borderline resectable PC was used, and 6 weeks elapsed from completion of RT to surgery. At the time of surgical resection, 90% of patients exhibited stable disease while 10% had progressive disease and the median survival was 1.1 years [248]. The second trial (NCT01333631), is currently analyzing the effects of the HDACI and antiepileptic drug valproic acid, in combination with chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine in PC patients.

An additional mechanism that has been explored for clinical testing, though currently stalled, for PC radiosensitization involves inhibition of Ras. Even with the activating mutations of Ras common to PC, the ability of Ras to function is dependent on post-translational farnesylation or geranylgeranylation (together called prenylation) via a farnesyltransferase or geranylgeranyltransferase, respectively, to allow for attachment to the inner envelope of the plasma membrane [179]. As such, farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTI) and geranylgeranyltransferase inhibitors (GGTI) have been used in combination with radiation. A phase II randomized trial of gemcitabine/paclitaxel/RT, followed by the FTI tipifarnib (R115777) for unresectable PC demonstrated that maintenance FTI failed to improve clinical outcome and was associated with increased toxicities [249]. It should be pointed out that it is well established that Kras and N-Ras become alternatively geranylgeranylated and remain fully functional in cells treated with FTIs [250–252]. Beyond FTIs, a dual farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase inhibitor (L-778123) has undergone preclinical and ultimately Phase-I evaluation as an IR adjunct in the hopes that Ras inhibition would lead to significant decrease in PC radioresistance [179,253]. Despite encouraging results from initial studies, including demonstration of enhanced radiosensitivity in patient-derived cell lines, L-778123 has been abandoned due to unacceptable cardiotoxicity encountered in clinical trials. Currently, focus is centered on reducing the toxicity either through cardioprotective add-on pharmaceuticals or alterations to the drug structure. Many researchers, including the National Cancer Institute sponsored “RAS Initiative” collaborative project, are engaged to find specific Ras inhibitors.

In addition to these potential methods for PC radiosensitization currently undergoing clinical testing, multiple other radiosensitizers have shown significant promise but have not yet moved beyond preclinical experiments. For example, HIF-1α inhibition as a mechanism for radiosensitization has been the subject of multiple studies as its nuclear translocation, which occurs in the context of cellular hypoxia, promotes the expression of various target genes involved in cell survival promotion, inhibition of apoptosis, and antioxidant function [254–256] Significantly, nuclear HIF-1α is found in 88% of PC tumor samples and only 16% of samples from normal pancreas, illustrating both the hypoxia present in PC as well as the likelihood that HIF-1α inhibition, if found to be a clinically viable method for PC radiosensitization, will differentially act on PC cells and not surrounding healthy pancreas [256]. Inhibition of HIF-1α with the orally bioavailable small molecule inhibitor PX-478 resulted in enhanced radiosensitivity in hypoxic PC cells in vitro, both with and without concurrent treatment with 5-FU or gemcitabine, showing an approximate 40% increase in IR-associated cell death [256,257]. Interestingly, the radiosensitizing effects of PX-478 were found to be enhanced in vivo, where a tumor growth inhibition 97% greater than that found with IR alone was observed when mice were concurrently treated with it and 5 daily 1Gy fractions of IR, highlighting the importance of tumor oxygenation on PC radiosensitivity [256].