Abstract

Modern vaccines must be aimed to generate long-lasting, high-affinity and broadly neutralizing antibody responses against pathogens. The diversity of B cell clones recruited into Germinal Center (GC) responses is likely to be important for the antigen neutralization potential of the antibody-secreting cells and memory cells generated upon immunization. However, which factors influence the diversity of B cell clones recruited into GCs is unclear. As recirculating naïve antigen-specific B cells arrive in antigen-draining secondary lymphoid organs, they may potentially join the ongoing GC response. However, the factors that limit their entry are not well-understood, and how that depends on the stage of the ongoing follicular T cell and GC B cell response is not known. In this work we show that in mice naïve B cells have a limited window of time during which they can undergo antigen-driven activation and join ongoing immunization-induced GC responses. However, pre-loading naïve B cells with even a threshold activating amount of antigen is sufficient to rescue their entry into GC response during its initiation, peak and contraction. Based on that, we suggest that productive acquisition of antigen may be one of the main factors limiting entry of new B cell clones into ongoing immunization-triggered GC responses.

Introduction

A hallmark of T-dependent B cell responses is generation of Germinal Centers (GCs), which are important for the development of long-term high affinity humoral immunity [1, 2]. GCs are anatomical substructures in B cell follicles that form around follicular dendritic cells (FDCs). GCs are seeded by antigen-activated B cells that have acquired cognate T cell help, proliferated, and differentiated into GC B cells. Within GCs, B cells undergo extensive proliferation, somatic hypermutation of their B cell receptors (BCRs), and class-switching and compete for antigen deposited on FDCs and for help from follicular helper T cells (Tfh) [3]. Tfh cells drive GC B cells’ affinity maturation by providing help preferentially to GC B cells that present more antigenic peptides in the context of MHCII, thus rescuing GC B cells from apoptosis and promoting their proliferation [4, 5]. In parallel, follicular regulatory T cells (Tfr) fine-tune GCs by down-regulating the magnitude of the GC response and by preventing expansion of non antigen-specific B cell clones [6, 7]. GC B cells then differentiate into long-lived plasma cells and class-switched memory B cells that harbor immunoglobulins and BCRs, respectively with higher affinity to foreign antigens [8–11].

While generation of long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells is a prerequisite for development of long-term humoral immunity, the diversity of B cell clones that participate in GC responses may contribute to the breadth of antigenic epitopes recognized by effector cells and therefore to the pathogen neutralization potential of the response.

While previous studies suggested that GCs are formed by relatively few B cells, recent works unambiguously demonstrated that GCs are seeded by 50–200 B cell clones [12–15]. However, the ability of antigen-specific B cells to populate early GCs is variable. When T cell help is limiting, B cell clones with relatively low affinity to antigen are recruited into GCs less efficiently [16].

Preexisting GCs can also be populated by new B cell clones following a boosting immunization [17]. However, the factors which control or limit recruitment of new B cell clones into ongoing GCs over the course of an infection or following a primary immunization are not known. Naïve antigen-specific B cells’ ability to enter preexisting “late” GCs is potentially limited by multiple factors: 1) limited availability of antigens to naïve cells; 2) competition with preexisting GC B cells for Tfh cell help; 3) difference in the helper functions of Tfh cells over time [18]; 4) increased exposure of B cells to Tfr cells. In this work, we attempted to assess how the likelihood of new B cell recruitment into GCs depends on the stage (initiation, peak, or contraction) of the Tfh/Tfr and GC response.

Our study suggests that B cells that transiently acquire a low amount of antigen can enter GCs at all stages of the response. However, the ability of naïve B cells to undergo antigen-dependent activation and recruitment into the GC response drops by 6–10 days after a standard immunization. We suggest that the main factor limiting the entry of new B cell clones into GCs after a primary immunization may be the availability of antigen for sampling by the naïve B cell repertoire.

Materials and Methods

Mice

B6 (C57BL/6) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratory. B6-CD45.1 (Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. BCR transgenic HyHEL10 [19] and MD4 mice [20] were generously provided by Jason Cyster. HyHEL10 mice were crossed with UBC-GFP (004353) (Jackson Laboratory) and with B6-CD45.1 mice and maintained on the B6 background. MD4 mice were crossed with B6-CD45.1 and maintained on the B6 background. Recipient mice were 6–10 weeks of age. All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen free environment and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Michigan.

Antigen preparation

Duck eggs were purchased locally. Duck egg lysozyme (DEL) was purified as previously described [19]. Ovalbumin (OVA) was purchased from Sigma. DEL was conjugated to OVA via glutaraldehyde cross-linking as previously described [19].

Immunization and adoptive transfer and immunization

Where indicated, recipient mice were preimmunized subcutaneously (s.c.) in the flanks and base of tail and into front foot pads (f.f.p.) with 100 μg OVA in Ribi (Sigma) or s.c. with 50 μg DEL-OVA in Ribi.

HyHEL10 B cells were enriched from donor mice by negative selection as previously described [21]. Transient exposure to antigen was performed as previously described with an antigen dose slightly above the threshold required for B cell activation [22]. In brief, purified HyHEL10 B cells were incubated with 0.5 μg/mL DEL-OVA ex vivo for 5 minutes at 37 °C and washed three times with room temperature DMEM supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose, L- glutamine and sodium pyruvate, 2% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 50 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. About 5 ×104 DEL-OVA-pulsed or naïve HyHEL10 B cells were then transferred into recipient mice. To study MD4 B cell activation, splenocytes from MD4 CD45.1 mice with a known frequency of transgenic B cells or from CD45.1 mice were transferred into recipient CD45.2 mice either unimmunized or s.c. pre-immunized with DEL-OVA in Ribi.

Flow cytometery and cytokine staining

The following antibodies (Abs) and reagents were used for flow cytometry analysis: biotinylated anti-mouse IgD (11-26/SBA-1, SouthernBiotech) and CXCR5 (2G8, BD Biosciences); fluorescently conjugated anti-mouse IgD-APC-Cy7 (11- 26c.2a, Biolegend), IgMa-PE (DS-1, BD Pharmingen), IgMb-PE (AF6-78, BD Pharmingen), PD1-PE-Cy7 (RMP1-30, Biolegend), CD25-Brilliant Violet 421 (PC61, Biolegends), CD38-PerCP-eFluor 710 (90, eBioscience), B220-V500 and B220-PerCP-Cy5.5 (RA3- 6B2, BD Pharmingen), FAS-PE-Cy7 (Jo2, BD Pharmingen), CD4-APC-Cy7 (RM4-5, Biolegend), CD8-APC-Cy7 (53-6.7, eBioscience), CD45.1-Alexa Fluor 700 (A20, Biolegend), GL7-eFluor 450 (GL7, eBioscience), FoxP3-APC (clone FJK-16s, eBioscience), CD69-PE (clone H1.2F3, Pharmingen), IL21-PE (clone FFA21, eBioscience), IFNγ- Alexa Fluor 700 (clone XMG1.2, Biolegends), and streptavidin-Qdot 605 (Life Technologies). Single-cell suspensions from inguinal lymph nodes (ILNs) were incubated with biotinylated antibodies for 20 minutes on ice, washed twice with 200 μl PBS supplemented with 2% FBS, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% NaN (FACS buffer), and then incubated with fluorophore- conjugated antibodies and streptavidin for 20 minutes on ice, and washed twice more with 200 μl FACS buffer. For IL21 and IFNγ cytokine staining, lymphocytes from ILNs of immunized mice were first resuspended in 10% DMEM (DMEM supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose, L- glutamine and sodium pyruvate, 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 50 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin) and then cultured in a CO2 incubator, at 37°C and stimulated with Cell Activation Cocktail (Biolegend) that contains PMA, ionomycin and Brefeldin A for 6 hours according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For FoxP3 and cytokine staining the cells were permeabilized and stained using FoxP3 staining buffer set (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then resuspended in FACS buffer for acquisition. Data were acquired on a FACSCanto and analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar).

Immunofluorescence

The following Abs/reagents were used for confocal immunofluorescent analysis: biotinylated anti-mouse IgD (11-26/SBA-1, SouthernBiotech), CD4-CF594 (RM4-5, BD biosciences), and streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 647 (Life Technologies) or BCL6-A647(clone K112-91, BD-Pharmingen) and IgMa-PE (clone DS-1, BD-Pharmingen). Brachial lymph nodes (BLNs) were harvested from recipient mice, fixed for 1 h in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS on ice and washed with PBS. They were then blocked overnight in 30% sucrose, 0.1% NaN in PBS, embedded in Tissue- Tek optimum cutting temperature compound, snap-frozen in dry ice and ethanol, and stored at −70 °C. Thirty micron cryostat sections were cut from the tissue blocks, affixed to Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher), and stained first with biotinylated anti-IgD Abs and then with anti-CD4 Abs and streptavidin as previously described [22]. Alternatively they were stained with anti-Bcl6 and anti-IgMa Abs. Confocal analysis of the sections was performed using Leica SP5 with argon and helium-neon lasers, 2-channel Leica SP spectral fluorescent PMT detector, and a 20× oil-immersion objective with a numerical aperture of 0.7. Images were processed using Imaris (Bitplane).

Statistics

Statistical tests were performed as indicated using Prism 6 (GraphPad). Differences between groups not annotated by an asterisk did not reach statistical significance.

Results

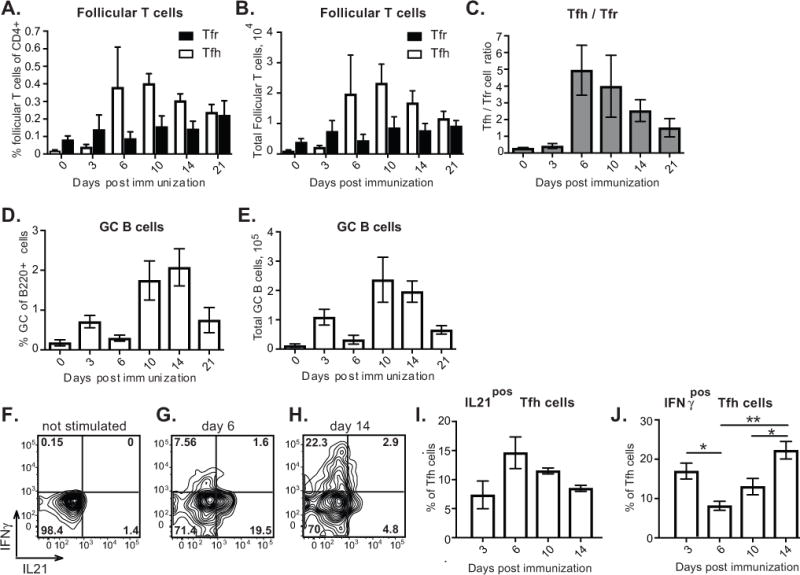

In order to determine whether the ability of B cells to enter immunization-triggered GCs depends on the stage of the GC response, we first analyzed the kinetics of GC B cell and follicular T cell responses in the draining lymph nodes (LNs) of mice immunized with the protein antigen ovalbumin (OVA) in Ribi adjuvant (Supplemental Fig. 1A, B, gating strategy). In unimmunized mice there were over 3 times as many Tfr as Tfh cells (Fig. 1A–C). By 6 days post immunization (d.p.i.) the number of Tfh cells significantly increased, reaching a 5:1 Tfh:Tfr ratio. (Fig. 1A–C). This was followed by expansion of GC B cells that peaked at 10–14 d.p.i. (Fig. 1D, E). At 14 d.p.i Tfh cell numbers and the Tfh/Tfr cell ratio started to decrease, followed by a substantial decline in GC B cell numbers by 21 d.p.i. (Fig. 1A–E). Based on the observed kinetics of the GC response and previously published data, GC seeding in the draining LNs is likely to occur between 3 and 6 d.p.i. [23, 24]. This is followed by the peak of the GC response at 10 d.p.i. and its resolution after 14 d.p.i.

Figure 1. Kinetics of immunization-induced follicular T cell and GC B cell response.

Flow cytometry analysis of follicular T cells and GC B cells in the inguinal lymph nodes (ILNs) of mice immunized with OVA in Ribi subcutaneously in the flanks and base of tail and into front foot pads. A, B, Follicular helper (white bars) and follicular regulatory (black bars) T cell frequencies of CD4+ B220− CD8− cells (A) and total numbers (B). C, Tfh/Tfr ratios. D, E, GC B cell frequencies of B220+ CD4− CD8− cells (D) and total numbers (E). F–J, Analysis of IL21 and IFNγ production by Tfh cells at various times following immunization. F–H, Representative examples of flow cytometry cytokine staining of FoxP3neg CXCR5highPD1high Tfh cells from ILNs of mice at 6 (F, G) and 14 (H) days post immunization, following their ex vivo stimulation with PMA and ionomycin (G, H) or without ex vivo stimulation (F). I, J, Fraction of Tfh cells that upregulate production of IL21 (I) and IFNγ (J) following ex vivo stimulation. Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01. Data are from 3–4 independent experiments, 1–3 mice per experiment. Data presented as mean ± SEM.

Previous studies indicated that Tfh cells’ cytokine production and effector functions vary depending on the stage of GC response [18]. To test whether these observations would hold under our selected immunization conditions, we assessed production of IL21 and IFNγ cytokines by Tfh cells at various times following immunization with OVA in Ribi. Consistent with previous findings [18], we observed a trend for decreased production of IL21 by Tfh cells during the later stages of the Tfh cell response (Fig 1.F–I). Interestingly, we also found that during Tfh cells’ contraction phase, production of IFNγ by Tfh cells significantly increased (Fig 1. F–H, J). To summarize, Tfh cell frequency, production of cytokines and ratio to Tfr cells vary throughout different stages of the immunization-induced GC reaction, which may potentially affect recruitment and participation of new B cell clones in T-dependent responses.

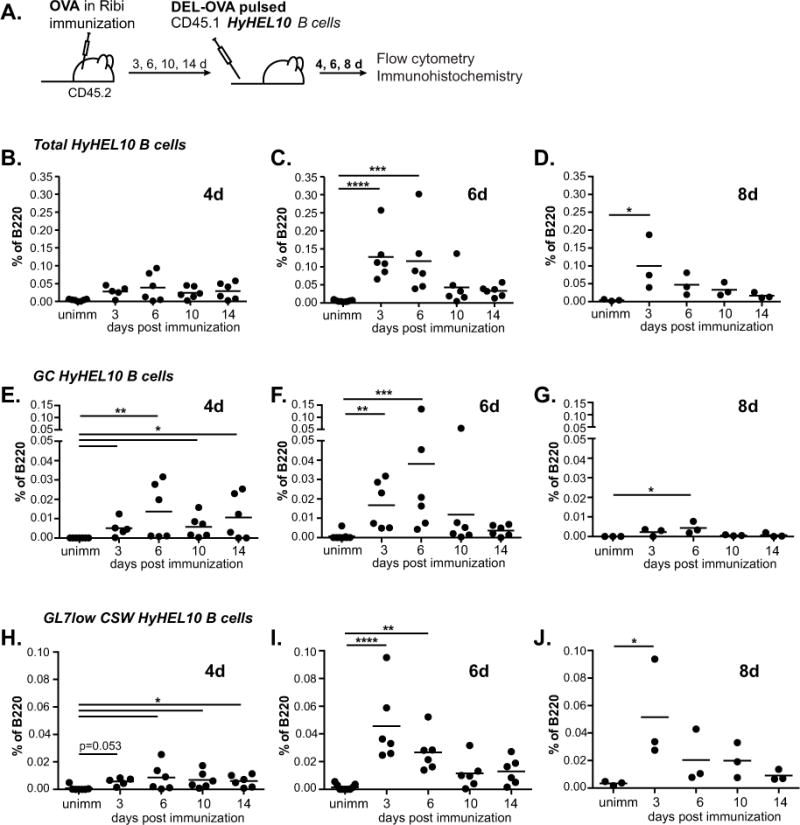

To address whether B cells that acquire the same amount of antigen have a substantially different ability to enter GCs depending on the phase of the GC response we made use of a recently published experimental strategy [22](Fig. 2A). Transgenic HyHEL10 B cells [25] that have B cell receptors (BCR) specific to duck egg lysozyme (DEL) were incubated ex vivo for 5 minutes with DEL chemically conjugated to OVA (DEL-OVA) at a concentration only slightly above HyHEL10 B cells’ activation threshold [22]. The unbound antigen was then washed off and HyHEL10 B cells were transferred into mice preimmunized with OVA in Ribi. While DEL-OVA pulsed HyHEL10 B cells could not reacquire their cognate DEL antigen in vivo, they could present preacquired OVA antigenic peptides in the context of MHCII molecules for recognition by OVA-specific Th cells in vivo. Our previous study demonstrated that 1) antigen-pulsed B cells transferred into recipient mice preimmunized with OVA for 3 days undergo proliferation, differentiate into GC B cells, and participate in histologically defined GCs in vivo and 2) that their ability to enter the B cell response is critically dependent on the acquisition of the Ag-linked OVA for presentation to activated Th cells [22].

Figure 2. Antigen-exposed HyHEL10 B cells recruitment into B cell response during initiation, peak and resolution of the immunization-induced GC response.

A, Experimental scheme. 5×104 HyHEL10 B cells pulsed ex vivo with 0.5 μg/mL DEL-OVA were transferred into unimmunized control mice or mice preimmunized with OVA in Ribi s.c. and f.f.p. for 3, 6, 10 and 14 days. Flow cytometry analysis of ILNs was performed at 4, 6, and 8 days post HyHEL10 B cell transfer. B–J, Frequencies of total HyHEL10 (B–D), GL7high FAShigh IgDlow CD38low HyHEL10 (E–G), and GL7low IgMlow IgDlow HyHEL10 (H–J) B cells of B220+ CD4− CD8− cells at 4d (B, E, H), 6d (C, F, I) and 8d (D, G, J) following the transfer. Data are from 3–5 independent experiments. Each point represents a separate mouse. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test to unimmunized control. *, **, ***, **** represent p≤0.05, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001 correspondingly.

To assess B cell recruitment into an immunization-driven GC response at its various stages, fifty thousand DEL-OVA pulsed HyHEL10 B cells were transferred into recipient mice at 3, 6, 10 and 14 days after immunization with OVA or into unimmunized mice as negative controls (Fig. 2A). These times correspond to the initiation, peak and contraction phases of the Tfh cell response (Fig. 1A–C).

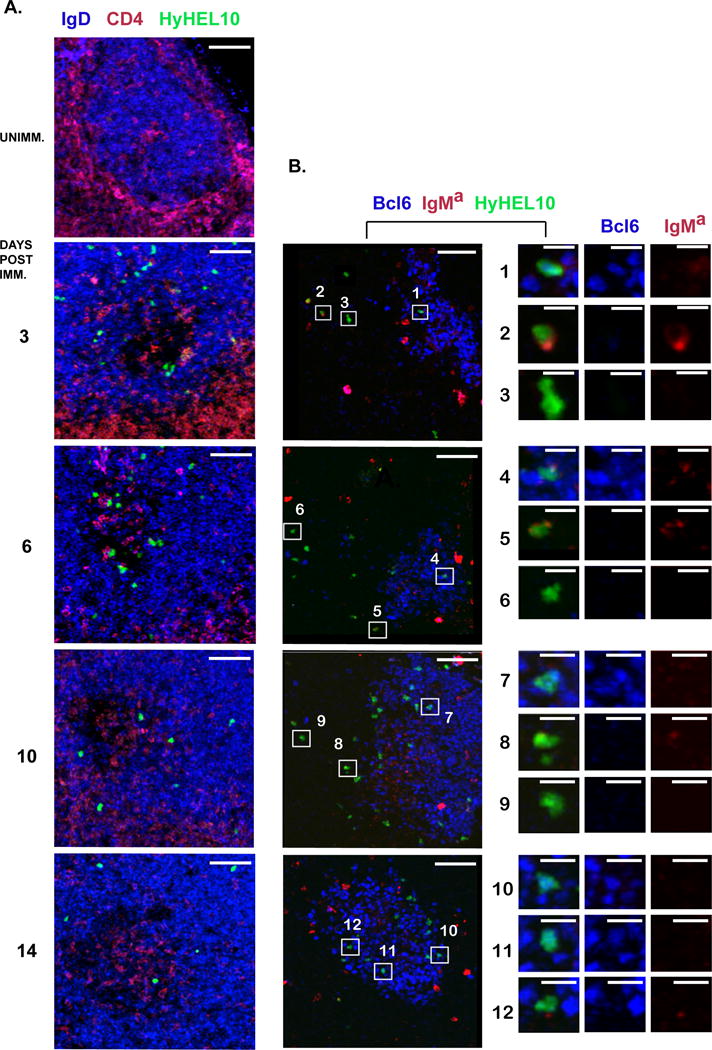

At 4 days after the transfer of antigen-pulsed HyHEL10 B cells, we observed their expansion in the draining LNs of all OVA-immunized recipient mice (Fig. 2B). Based on the GL7high FAShigh IgDlow CD38low phenotype (Supplemental Fig. 1C), comparable numbers of HyHEL10 B cells differentiated into GC B cells in all OVA-immunized, but not in control recipient mice at 4 days after transfer (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. 2, black bars). At 6 days after the transfer the numbers of HyHEL10 GC B cells either slightly increased (when transferred at 3, 6 d.p.i.) or stayed the same (at 10, 14 d.p.i.) (Fig. 2F; Supplemental Fig. 2, gray bars). In all cases, HyHEL10 GC B cell numbers started to decline by 8 days after B cell transfer, as expected due to their inability to reacquire their cognate antigen DEL within GCs and compete with OVA-specific endogenous GC B cells (Fig. 2G; Supplemental Fig. 2, white bars). Some of the antigen-pulsed HyHEL10 B cells also differentiated into GL7low class-switched B cells, which made up 20–40% of total HyHEL10 B cells by 6–8 days after their transfer (Fig. 2H–J, 2B–D). Few, if any, HyHEL10 plasma cells were found (data not shown). The presence of HyHEL10 B cells in the GCs of OVA-immunized, but not control mice, was confirmed by immunofluorescent analysis of draining LNs regardless of the time of antigen-pulsed B cell transfer following immunization (Fig. 3, HyHEL10 B cells express GFP and are detected as green). The majority of GC- resident HyHEL10 B cells also expressed Bcl6 (Fig. 3B; see examples 1, 4, 7, 10, 11). Of note, HyHEL10 B cells were also found in other regions of B cell follicles, some of which were IgMa positive (Fig. 3B; examples 2, 5) and some class-switched (Fig. 3B; examples 3, 6, 9). Altogether these results indicate that at various stages of the OVA-immunization induced endogenous follicular T cell/GC response, acquisition of relatively small amounts of DEL-OVA antigen by newly arriving HyHEL10 B cells is sufficient for their recruitment into the GC and class-switched GL7low memory B cell responses in OVA-draining lymph nodes. However, when antigen-pulsed B cells are transferred at the peak and resolution phases of the Tfh/GC response (at 10 and 14 d.p.i.), their subsequent accumulation as GC and class-switched GL7low B cells at 6 and 8 days after transfer is reduced, in parallel with the overall decline in the endogenous follicular T cell/GC response.

Figure 3. Antigen-exposed HyHEL10 B cells can enter GCs during initiation, peak and resolution of the immunization-induced GC response.

A, B, Examples of DEL-OVA pulsed HyHEL10 B cells’ anatomical positioning with respect to GCs. Confocal immunofluorescent analysis of 14–20 μm thick sections from the BLNs of mice which were either unimmunized or preimmunized for 3, 6, 10, or 14 days with OVA in Ribi, received DEL-OVA pulsed HyHEL10 B cells, and were analyzed at 6 days post transfer. Green Fluorescent Protein-expressing HyHEL10 B cells are shown as green. Sections were stained with fluorescently conjugated anti-CD4 (red) and anti-IgD (blue) antibodies in A or IgMa (red) and Bcl6 (blue) in B. Right column is a zoomed in view on the HyHEL10 cells selected in the middle column. Bars: left and middle columns - 50 μm, right column - 10 μm. In A: IgDlow areas outline GCs. In B: Bcl6 positive cells are GC B cells, IgManeg HyHEL10 B cells are class switched. Not associated with GFP-positive HyHEL10 cells red staining is likely due to nonspecific binding of IgMa, presumably to macrophages and FDCs. The data are representative of three independent experiments, 1 mouse per experiment.

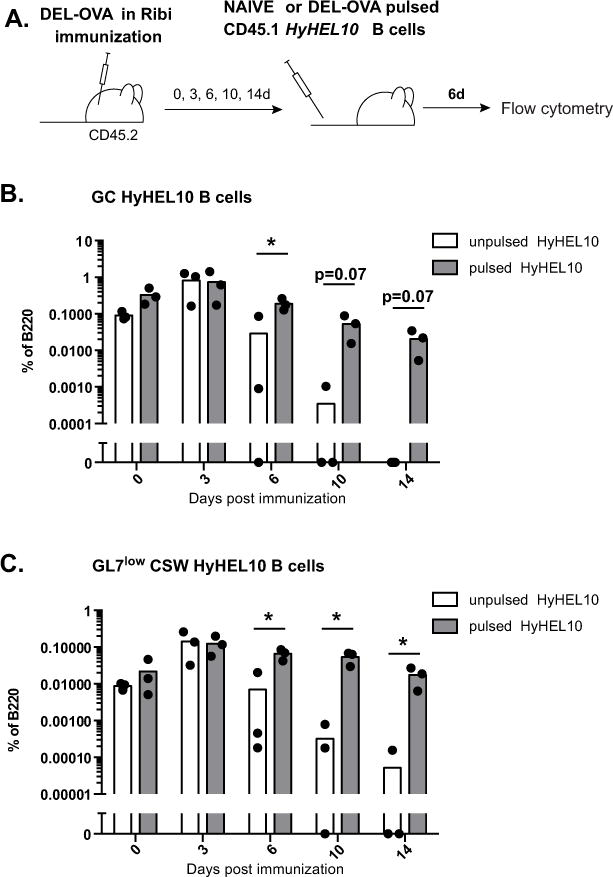

To test the ability of naïve B cells to enter the GC response during its various stages, naïve HyHEL10 B cells were transferred into mice immunized with their cognate antigen DEL-OVA in Ribi adjuvant at 0, 3, 6, 10 and 14 d.p.i (Fig. 4A). While HyHEL10 B cells transferred into recipient mice prior to or 3 days after the immunization mounted a vigorous GC B cell response, their ability to form GC B cells began to decline when they were transferred 6 days following the immunization and completely disappeared at later times (Fig. 4B, white bars). Naïve HyHEL10 B cells also formed substantially smaller class-switched B cell responses when transferred into DEL-OVA immunized mice with a 10–14 day delay (Fig. 4C, white bars). However, HyHEL10 B cells pulsed with a low dose of antigen (0.5 μg/ml of DEL-OVA) formed GC B cells and class-switched GL7low cells when transferred into DEL-OVA immunized mice even at the peak and prior to contraction phases of the GC response, similarly to antigen-pulsed cells transferred into OVA-immunized mice (Fig. 4B, C, gray bars, Fig. 2E–J).

Figure 4. Recruitment of naïve and DEL-OVA-pulsed HyHEL10 B cells into B cell response during initiation, peak and resolution of GC response in DEL-OVA immunized mice.

A, Experimental scheme. 5×104 HyHEL10 B cells (naïve or pulsed ex vivo with 0.5 μg/mL DEL-OVA) were transferred into mice preimmunized with DEL-OVA in Ribi s.c. for 0, 3, 6, 10 and 14 days. Flow cytometry analysis of ILNs was performed at 6 days post HyHEL10 B cell transfer. B, C, Frequencies of unpulsed (white bars) or DEL-OVA pulsed (gray bars) HyHEL10 GL7high FAShigh IgDlow CD38low (B) and GL7low IgMlow IgDlow HyHEL10 (C) B cells of B220+ CD4− CD8− cells. Data are from 3 independent experiments. Each point represents a separate mouse. *, p< 0.05. Multiple T-tests with Holm-Sidak method of correction for multiple comparisons.

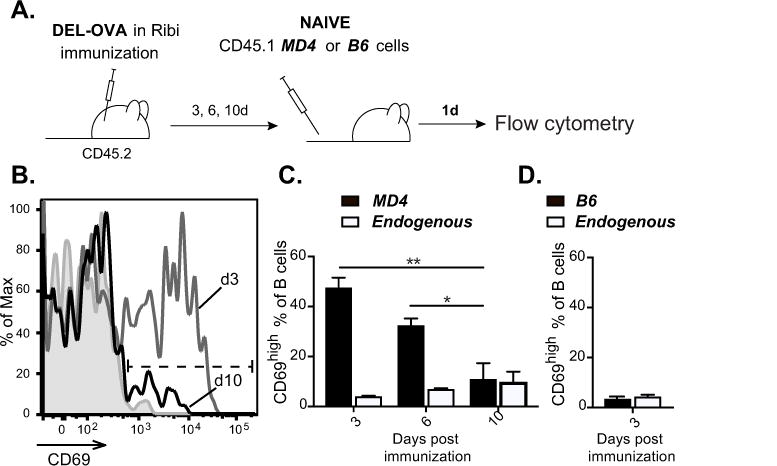

To test whether B cells have a limited window of time to undergo antigen-driven activation following a standard protein immunization, we utilized BCR transgenic B cells from MD4 mice that have the same specificity to DEL as HyHEL10 B cells. Unlike HyHEL10 B cells, MD4 B cells cannot undergo class-switching, but they are better for enumeration of antigen-specific B cells by flow cytometry because they constitute the majority (>95%) of B cells in MD4 mice. Splenocytes containing 0.2–1 million of antigen-specific B cells from CD45.1 MD4 mice were transferred into recipient CD45.2 mice preimmunized with DEL-OVA in Ribi for 3, 6 and 10 days or into unimmunized control mice. One day later antigen-driven activation of the recently arriving MD4 B cells was assessed in the ILNs of recipient mice based on their upregulation of surface CD69 (Fig. 5A). We found that many MD4 B cells transferred at 3 days post immunization underwent activation (Fig. 5B, C). In contrast, transferred non-transgenic CD45.1 B cells did not upregulate CD69 in ILNs of DEL-OVA mice preimmunized for 3 days (Fig. 5D). The fraction of MD4 B cells that underwent Ag-dependent activation and upregulated CD69 significantly decreased between 3 and 10 days following DEL-OVA immunization (Fig. 5B, C). Based on these observations and the findings described above, we conclude that following immunization with standard protein antigen in Ribi adjuvant, antigen-driven activation becomes the predominant factor limiting the entry of new antigen-specific B cells into the ongoing GC B cell response (Fig. 6).

Figure 5. Antigen-dependent activation of B cells at various times post immunization.

A–D, Upregulation of CD69 by naïve MD4 or B6 B cells transferred into DEL-OVA preimmunized mice. A, Experimental scheme. 2–10×105 naïve CD45.1 MD4 B cells were transferred into mice preimmunized with DEL-OVA in Ribi s.c. for 3, 6, and 10 days or into control unimmunized mice. Similar number of CD45.1 B6 B cells were transferred into mice preimmunized with DEL-OVA in Ribi s.c. for 3 days. Flow cytometry analysis of ILNs was performed 1 day post B cell transfer. B, Representative flow cytometry analysis of MD4 B cell’s CD69 surface staining after their transfer into unimmunized mice (filled gray) or mice preimmunized for 3 (gray line) and 10 (black line) days. C, Frequencies of CD69high MD4 B cells (B220pos CD4neg CD8 neg CD45.1 pos CD45.2neg, black bars) and endogenous B cells (B220pos CD4neg CD8 neg CD45.1neg CD45.2pos, white bars). Data are from 3 independent experiments, 1 mouse per experiment. Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *, **, represent p<0.05, 0.01 correspondingly. D, Frequencies of CD69high B220pos CD4neg CD8 neg CD45.1 pos CD45.2 neg B6 B cells that were transferred at 3 days post DEL-OVA immunization (black bars) and CD45.1neg CD45.2pos endogenous B cells (white bars). Data are from 2 independent experiments, 4 recipient mice. Data presented as mean ± SEM.

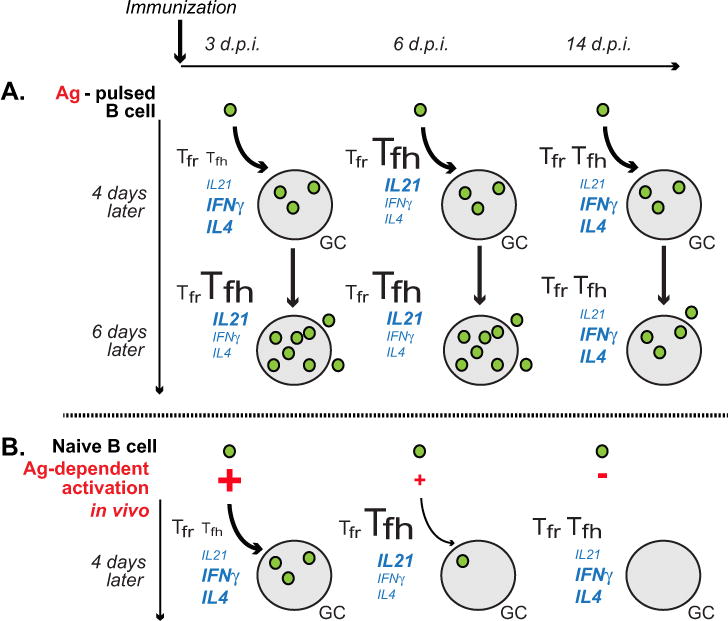

Figure 6. Model of new B cell entry into GC response at various times after immunization.

A, B cells exposed to a threshold activating dose of antigen and cognate T cell help can enter GC response with comparable efficiency at various times after immunization, including the initiation, peak and resolution phases of follicular T cell response. However, their subsequent expansion in GCs and formation of memory cells is reduced during the Tfh/GC resolution phase, possibly due to their decreased exposure to Tfh cell-produced IL21 and/or increased repression from Tfr cells. B, Following immunization, naïve antigen-specific B cells have a limited window of time when they can enter GC response. This window of time is determined by antigen-dependent activation of the naïve B cells entering into antigen-draining LNs. In mice immunized with DEL-OVA in Ribi s.c., antigen-dependent activation and entry into GCs starts to drop at 6 d.p.i.

Discussion

While the cellular and molecular mechanisms of GC B cell affinity maturation and their differentiation into memory B cells and plasma cells have been analyzed in a great level of detail, the factors that control clonal diversity of B cell responses are much less understood. In this work, we addressed which factors may limit the access of new antigen-specific B cell clones into GC and memory B cell responses following a standard protein/adjuvant immunization. First, we asked whether the ability of B cells uniformly exposed to the same small dose of cognate antigen to enter GC responses would be different during the initiation, peak, and resolution of the follicular T cell/GC B cell response. Our studies suggest that the initial expansion of antigen-experienced B cells in vivo and the generation of GC B cells do not strongly depend on the phase of the follicular T cell/GC response (Fig. 6A). We also confirmed histologically that B cells can enter GCs during various phases of the follicular T cell/GC response. However, when antigen-exposed B cells enter the GC response during the peak or contraction phase, their subsequent expansion as GC B cells and their differentiation into memory-like GL7low class-switched B cells is reduced (Fig. 6A). We speculate that the observed trend may be explained by the decreased ability of Tfh cells to support proliferation and survival of both older and newer GC B cell clones, possibly due to the decrease in Tfh cell numbers and altered cytokine-mediated activity and/or the relative increase in the contribution of Tfr cells that negatively impact GC sustainability [6, 7, 18].

We then assessed the ability of naïve antigen-specific B cells to enter the GC response at various times following immunization with their cognate antigen. We found that in contrast to B cells that pre-acquired a small amount of antigen, naïve B cells’ ability to enter both the GC and GL7low CSW B cell responses drops by 6–10 days following immunization. That correlated with significantly decreased ability of antigen-specific B cells to undergo early activation (Fig. 6B). This outcome is consistent with naïve B cell access to antigen becoming relatively limited in vivo after a few days following immunization, suggesting it is a critical factor for new antigen-specific B cell clones’ recruitment into the GC response. The fact that boosting immunizations promote recruitment of new antigen-specific B cell clones into preexisting GCs is consistent with this hypothesis [17].

One possibility is that over time naïve B cells’ access to antigen becomes more restricted. Formation of immune complexes leads to antigen redistribution onto FDCs [26]. While antigens persist on FDCs for prolonged periods of time, supporting the GC response, a previous study indicated progressive loss in naïve B cells’ ability to acquire antigens from FDCs overtime [27]. Gradual degradation of antigen and formation of GCs around FDCs may partially limit access of naïve B cells to FDC-presented antigens. Steric hindrance by the antibodies generated during the early B cell response in some cases may additionally limit antigen acquisition by newly arriving B cell clones [28]. Further studies are necessary to discriminate between these possibilities and thus decipher factors controlling recruitment of new B cell clones into ongoing immunization-induced GCs. Future studies should also address whether various adjuvants or antigen administration protocols affect the window of time in which new B cells may enter ongoing GCs following immunization. Dissecting these factors may be important for improving the diversity of B cell clones entering GCs following vaccinations and thus increasing the chances of generating broadly neutralizing antibody responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Cyster for provision of mice.

References

- 1.Berek C, Berger A, Apel M. Maturation of the immune response in germinal centers. Cell. 1991;67(6):1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90289-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob J, Kelsoe G, Rajewsky K, Weiss U. Intraclonal generation of antibody mutants in germinal centres. Nature. 1991;354(6352):389–392. doi: 10.1038/354389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesin L, Ersching J, Victora GD. Germinal Center B Cell Dynamics. Immunity. 2016;45(3):471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Meyer-Hermann M, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter. Cell. 2010;143(4):592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gitlin AD, Shulman Z, Nussenzweig MC. Clonal selection in the germinal centre by regulated proliferation and hypermutation. Nature. 2014;509(7502):637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, Srivastava M, Divekar DP, Beaton L, Hogan JJ, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med. 2011;17(8):975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung Y, Tanaka S, Chu F, Nurieva RI, Martinez GJ, Rawal S, Wang YH, Lim H, Reynolds JM, Zhou XH, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat Med. 2011;17(8):983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McHeyzer-Williams M, Okitsu S, Wang N, McHeyzer-Williams L. Molecular programming of B cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(1):24–34. doi: 10.1038/nri3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brink R, Phan TG, Paus D, Chan TD. Visualizing the effects of antigen affinity on T-dependent B-cell differentiation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86(1):31–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oracki SA, Walker JA, Hibbs ML, Corcoran LM, Tarlinton DM. Plasma cell development and survival. Immunol Rev. 2010;237(1):140–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroese FG, Wubbena AS, Seijen HG, Nieuwenhuis P. Germinal centers develop oligoclonally. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17(7):1069–1072. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu YJ, Zhang J, Lane PJ, Chan EY, MacLennan IC. Sites of specific B cell activation in primary and secondary responses to T cell-dependent and T cell-independent antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21(12):2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob J, Przylepa J, Miller C, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. III The kinetics of V region mutation and selection in germinal center B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178(4):1293–1307. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tas JM, Mesin L, Pasqual G, Targ S, Jacobsen JT, Mano YM, Chen CS, Weill JC, Reynaud CA, Browne EP, et al. Visualizing antibody affinity maturation in germinal centers. Science. 2016;351(6277):1048–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwickert TA, Victora GD, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Mugnier MR, Gitlin AD, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. A dynamic T cell-limited checkpoint regulates affinity-dependent B cell entry into the germinal center. J Exp Med. 2011;208(6):1243–1252. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwickert TA, Alabyev B, Manser T, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal center reutilization by newly activated B cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):2907–2914. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein JS, Herman EI, Lainez B, Licona-Limon P, Esplugues E, Flavell R, Craft J. TFH cells progressively differentiate to regulate the germinal center response. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(10):1197–1205. doi: 10.1038/ni.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen CDC, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science. 2007;315:528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1136736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334(6184):676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen CD, Ansel KM, Low C, Lesley R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, Cyster JG. Germinal center dark and light zone organization is mediated by CXCR4 and CXCR5. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(9):943–952. doi: 10.1038/ni1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner JS, Marthi M, Benet ZL, Grigorova I. Transiently antigen-primed B cells return to naive-like state in absence of T-cell help. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15072. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitano M, Moriyama S, Ando Y, Hikida M, Mori Y, Kurosaki T, Okada T. Bcl6 protein expression shapes pre-germinal center B cell dynamics and follicular helper T cell heterogeneity. Immunity. 2011;34(6):961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerfoot SM, Yaari G, Patel JR, Johnson KL, Gonzalez DG, Kleinstein SH, Haberman AM. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity. 2011;34(6):947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen CD, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science. 2007;315(5811):528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1136736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heesters BA, Myers RC, Carroll MC. Follicular dendritic cells: dynamic antigen libraries. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(7):495–504. doi: 10.1038/nri3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki K, Grigorova I, Phan TG, Kelly LM, Cyster JG. Visualizing B cell capture of cognate antigen from follicular dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(7):1485–1493. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicasio M, Sautto G, Clementi N, Diotti RA, Criscuolo E, Castelli M, Solforosi L, Clementi M, Burioni R. Neutralization interfering antibodies: a “novel” example of humoral immune dysfunction facilitating viral escape? Viruses. 2012;4(9):1731–1752. doi: 10.3390/v4091731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.