Abstract

Ocular infection with Herpes Simplex Virus causes a chronic T-cell mediated inflammatory lesion in the cornea. Lesion severity is affected by the balance of different CD4 T-cell subsets with greater severity occurring when the activity of regulatory T-cells is compromised. In the present report, fate-mapping mice were used to assess the stability of Treg function in ocular lesions. We show that cells that were once FoxP3+ functional Treg may lose FoxP3 and become Th1 cells which themselves could contribute to lesion expression. The instability mostly occurred with IL-2 receptor low Treg and was shown to be in part the consequence of exposure to IL-12. Lastly, in-vitro generated iTreg were shown to be highly plastic and capable of inducing SK when adoptively transferred into Rag1−/− mice, with 95% of iTreg converting into ex-Treg in the cornea. This plasticity of iTreg could be prevented when they were generated in the presence of Vitamin-C and Retinoic acid. Importantly, adoptive transfer of these stabilized iTreg to HSV-1 infected mice more effectively prevented the development of SK lesions than did the control iTreg. Our results demonstrate that CD25lo Treg and iTreg instability occurs during a viral immuno-inflammatory lesion and that its control may help avoid lesion chronicity.

Introduction

Ocular infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) can result in a chronic immuno-inflammatory reaction in the cornea, which represents a common cause of human blindness (1). Studies in animal models have revealed that stromal keratitis (SK) lesions are orchestrated mainly by IFN-γ–producing CD4+ T cells (Th1) cells (2, 3). The lesions are less severe and can even resolve if regulatory T cells (Treg), such as CD4 Foxp3 T cells, dominate over the proinflammatory CD4 T cell subsets (4, 5). Lesions become far more severe if Treg are depleted prior to infection or even if suppressed in the face of ongoing infection (4, 6). Thus lesions can be limited in severity if Treg function is optimized. Recent studies on some experimental models of autoimmunity have revealed that the function of Treg may be unstable in the face of an inflammatory environment (7–10). In fact Treg may lose their regulatory function and even take on proinflammatory activity and contribute to lesion expression. So far it is not known if Treg plasticity happens during a viral immune-inflammatory lesion and if the event helps explain why lesions become chronic and eventually fail to resolve. This issue is evaluated in the present report using a fate mapping mouse model system.

Reasons for plasticity are thought to be the consequence of either epigenetic modifications or posttranslational modifications (11). Several studies have shown that DNA demethylation of the Foxp3 conserved noncoding sequence 2 (CNS2), also named Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR), is critical for stable expression of FoxP3 (12, 13). Demethylation of CpG motifs allows critical transcription factors, such as Foxp3 itself and Runx1–Cbf-β complex, to bind to the TSDR region and keep the transcription of Foxp3 active in the progeny of dividing Treg (14). Another layer of epigenetic control involves the acetylation of the Foxp3 gene, which enforces FoxP3 expression and stability (15). Several other external stimuli such as proinflammatory cytokines can also influence Treg stability either by influencing the epigenetic status of the FoxP3 gene or by making posttranslational modification (16). Accordingly, activation of Treg in the presence of IL-6 leads to a STAT3-dependent decrease in Foxp3 protein and message accompanied by increased DNA Methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) expression. These effects lead to methylation of the TSDR region of the Foxp3 gene, as well as reduced acetylation of histone 3 at the upstream promoter region of the gene (17–19). Another important cytokine that influences Treg stability is IL-2 (20). Accordingly, several recent studies correlate robust surface expression of the high affinity IL-2 receptor (CD25) with enhanced Foxp3 expression, suppressive function, and stability of the Treg phenotype (9, 21, 22).

In this report we use fate mapping mice to show that Treg plasticity occurs in a virus induced inflammatory reaction and might contribute to stromal keratitis lesion severity and chronicity by secreting proinflammatory cytokine IFN-γ. This plasticity of Treg occurred more readily in the CD25lo population of Treg and was in part due to proinflammatory cytokine IL-12. Additionally, we also show that iTreg are highly plastic in the SK microenvironment. Lastly of therapeutic interest we could limit iTreg plasticity both in-vitro and in-vivo by generating induced Treg in the presence of Vitamin C and Retinoic acid. Moreover these stabilized iTreg could reduce SK lesions more effectively compared to unstable iTreg when adoptively transferred to HSV infected mice. All these results suggest that stabilizing Treg might represent a process to be targeted to minimize lesion expression and their chronicity.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female 6 to 8 week old C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). CD45.1 congenic (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ), Rag1-deficient (B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J) and B6 ROSA26-Td Tomato reporter mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Foxp3-GFP-Cre mice were provided by Dr. Jeffery Bluestone (San Francisco, CA). To generate Treg fate mapping mice Foxp3-GFP-Cre were crossed with B6 ROSA26-Td Tomato mice. Foxp3-GFP (C57BL/6 background) mice were a kind gift from M. Oukka (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School), BALB/c DO11.10 RAG2 −/− mice were purchased from Taconic and kept in pathogen free facility where food, water, bedding and instruments were autoclaved. All mice were housed in facilities at the University of Tennessee (Knoxville, TN) approved by the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care. All investigations followed guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the University of Tennessee Animal Care and Use committee (protocol approval numbers 1253-0412 and 1244-0412). All procedures were performed under tribromoethanol (avertin) anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Virus

HSV-1 strain RE Tumpey and HSV-1 KOS was propagated in Vero cell monolayers (number CCL81; ATCC, Manassas, VA), titrated, and stored in aliquots at −80°C until used. Ultraviolet (UV) inactivation of the HSV-1 RE virus was performed for 10 minutes. Following this protocol, a plaque assay was done to confirm that the virus was killed.

Corneal HSV-1 Infection and Scoring

Corneal infections of mice were performed under deep anesthesia. The mice were lightly scarified on their corneas with a 27-gauge needle, and a 3-μL drop that contained 104 plaque-forming units of HSV-1 RE was applied to one eye. Mock-infected mice were used as controls. These mice were monitored for the development of SK lesions. The SK lesion severity and angiogenesis in the eyes of mice were examined by slit-lamp biomicroscopy (Kowa Company, Nagoya, Japan). The scoring system was as follows: 0, normal cornea; +1, mild corneal haze; +2, moderate corneal opacity or scarring; +3, severe corneal opacity but iris visible; +4, opaque cornea and corneal ulcer; and +5, corneal rupture and necrotizing keratitis.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

At day 15 pi, corneas were excised, pooled group-wise, and digested with liberase (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN) for 45 minutes at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. After incubation, the corneas were disrupted by grinding with a syringe plunger on a cell strainer and a single-cell suspension was made in complete RPMI 1640 medium. The single-cell suspensions obtained from corneal samples were stained for different cell surface molecules for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses. All steps were performed at 4°C. Briefly, cells were stained with respective surface fluorochrome-labeled Abs in FACS buffer for 30 minutes, then stained for intracellular Abs. Finally, the cells were washed three times with FACS buffer and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde. The stained samples were acquired with a FACS LSR II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

To determine the number of IFN-γ producing T cells, intracellular cytokine staining was performed. In brief, corneal cells were either stimulated with Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (50ng) and Ionomycin (500ng) for 4 hours in the presence of brefeldin A (10 μg/mL) or stimulated with UV-inactivated HSV-1 RE (1 MOI) overnight followed by 5 hour brefeldin A (10 μg/mL) in U-bottom 96-well plates. After this period, Live/Dead staining was performed followed by cell surface and intracellular cytokine staining using Foxp3 intracellular staining kit (ebioscience) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Reagents and antibodies

CD4 (RM4-5), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), CD25 (PC61, 7D4), CD44 (IM7), Foxp3 (FJK-16S), anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD28 (37.51), GolgiPlug (brefeldin A) from either ebiosciences or BD biosciences. PMA and Ionomycin from sigma. Cell Trace Violet and Live/Dead Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain Kit from Life Technologies. Recombinant IL-2, IL-12, IL-6 and TGF-β from R&D systems.

TSDR assay

A quantitative real-time PCR method was used as described by Floess et al., 2007 (12). Briefly, two subsets of Treg (CD4+ Foxp3+ GFP+ CD25lo and CD4+ Foxp3+ GFP+ CD25hi) from HSV-1 ocularly infected Foxp3-GFP male mice (day 15 pi) or iTreg generated with or without the supplementation of Vitamin C +RA from naïve CD4 + T cells isolated from the spleens of Foxp3 GFP male mice as described above (2 × 105 each) were sorted and processed using the EZ DNA Methylation-Direct kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified bisulfite-treated DNA was used in a quantitative PCR reaction. Primers and probes sequences used were the following: forward primer, 5′-GGTTTATATTTGGGTTTTGTTGTTATAATTT-3′; and reverse primer, 5′-CCCCTTCTCTTCCTCCTTATTACC-3′. Probe sequences were: methylated (CG) probe, 5′-TGACGTTATGGCGGTCG-3′; and unmethylated (TG) probe, 5′-ATTGATGTTATGGTGGTTGGA-3′. PCR was performed with 10 μl Universal Master Mix II (Applied Biosystems), 1 μl eluted DNA, primer/probe mix, and enough water to bring the total volume to 20 μl. Final concentration of primers were 900 nM and concentration of probes were 150 nM. Reactions were run for 10 min at 95°C for 10 min and 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 61°C for 1.5 min (7500 Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems). Percent demethylation was calculated using the formula percent demethylation = 100/[1 + 2(CtTG–CtCG)], where CtTG represents the threshold cycle of the TG (unmethylated) probe and CtCG represents the threshold cycle of the CG (methylated) probe (23).

T cell isolation, sorting and adoptive transfer experiments

Single-cell suspensions were obtained from DLNs and the spleens from footpad or ocular HSV-1 infected mice at day 5 and day 15 pi respectively. Splenic erythrocytes were eliminated with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich). To purify the peripheral CD4+ T cell subpopulation obtained from FM mice, pooled spleen and DLN cells were isolated using a mouse CD4+ T cell isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Cells were then stained and subject to FACS sorting. The purity of all the sorted cells was >95%. The sorted cells were subsequently used for adoptive transfer experiments.

For adoptive transfer experiments in Balb/c mice, splenocytes isolated from DO11.10 RAG2 −/− mice were used as a precursor population for the induction of Foxp3+ in CD4+ T cells as described elsewhere (24). Briefly, (1×106/ml) splenocytes after RBC lysis and several washings were cultured in RPMI media containing rIL-2 (100 U/ml) and TGFβ (5ng/ml) in the presence or absence of Vitamin C and RA with plate bound anti-CD3/28 Ab (1 μg/ml) for 5 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After 5 days, a few cells were characterized for Foxp3 intracellular staining (ebioscience staining kit) analyzed by flow cytometry. Based on the frequency of Live Foxp3+ cells generated in the different cultures conditions 10 × 106 Vitamin C + RA stabilized iTreg or control unstable iTreg were adoptively transferred i.v into HSV-1 infected Balb/c mice at day 3 pi.

Administration of IVIGs

Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs; Gammagard Liquid) was obtained from Baxter (Deerfield, IL). Rag1−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with IVIG (3.75 mg per mouse) at day 2 after infection. The dose of IVIG was chosen to be 3.75 mg per mouse, based on previous studies (25).

In vitro Treg and Treg stability assays

Splenocytes isolated from DO11.10 RAG2 −/− or Foxp3 GFP mice were used as a precursor population for the induction of Foxp3+ in CD4+ T cells. Briefly, 1×106 splenocytes after RBC lysis and several washings were cultured in 1ml RPMI media containing rIL-2 (100 U/ml) and TGFβ (5ng/ml) in the presence or absence of Vitamin C and RA with plate bound anti-CD3/28 Ab (1 μg/ml) for 5 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After 5 days, samples were characterized for Foxp3 intracellular staining (ebioscience staining kit) or GFP expression (Foxp3 GFP mice) analyzed by flow cytometry. Treg were either sorted (TSDR methylation analysis) or cultured in 96-well round bottom plate in the presence of IL-2 (100U/ml) or IL-12 (5ng/ml) or IL-6 (25ng/ml) +TGF-β (1ng/ml) for 3 days followed by flow cytometry analysis of Live CD4+ Foxp3+ cells.

In vitro suppression assay

To measure the suppressor function of CD25lo and CD25hi Treg, FACS sorted CD25lo, CD25hi GFP+ cells and naïve CD4+ cells (CD62L+ CD44−) from DLN and spleens (day 15 pi) of HSV-1 ocularly infected FM mice were cultured with anti-CD3 (1 μg/well) and anti-CD28 (0.5 μg/well) antibodies in a U-bottom 96-well plate. The suppressive capacity of the subsets of Treg was measured by co-culturing Treg and T conventional cells (Tconv) at different ratios (Treg/Tconv, 1:1 to 1:8). After 3 days of incubation, the extent of CTV dilution was measured in CD4+ cells by flow cytometry. Percent suppression by different subsets of Treg was calculated by using the formula 100 – [(frequency of cells proliferated at a particular Treg/effector T cell ratio)/(frequency of cells proliferated in the absence of Treg)].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student t test unless otherwise specified. A P value of <0.05 was regarded as a significant difference between groups: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Treg lose FoxP3 expression in the cornea after ocular HSV-1 infection and acquire a Th1 cell phenotype

To directly examine Treg plasticity in the cornea after HSV-1 ocular infection in-vivo, FoxP3Cre-GFP: Rosa26lsl-Td-Tomato mice (now referred to as fate mapping mice (FM mice)) were used. These mice allow Treg fate mapping and the ability to distinguish between cells that currently express from the cells that once expressed FoxP3 but now lack its expression (ex-Treg). FM mice have cells that can be distinguished by flow cytometric analysis into three main T cell populations that participate in SK lesions. Accordingly, Treg are (CD4+ GFP+ Tomato+), ex-Treg are (CD4+ Tomato+ GFP−) and lastly effector CD4 T cells are (CD4+ Tomato− GFP−) (Supplementary figure 1). It was evident that after HSV-1 ocular infection of FM mice that some of the Treg lineage cells in the cornea lost their GFP expression indicating their likely loss of Treg function. Such ex-Treg accounted for 37% of the total Treg population at day 8, 53.8% at day 15 and 35.3% at day 21 pi (Figure 1A). Curiously, the peak numbers of ex-Treg were evident in day 15 pi samples, which is the usual time when lesions are at their peak (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Kinetic analysis of ex-Treg in the corneas of HSV-1 infected mice.

FM mice were infected ocularly with 1× 104 PFU of HSV-1, and at each time point (d8, 15 and day 21) three to four corneas were collected, pooled, and digested with Liberase and analyzed for various cell types. A&B) Representative FACS plots, frequencies and average numbers of corneal ex-Treg cells at each time point pi. C&D) Intracellular staining was conducted to quantify Th1 ex-Treg cells by stimulating them with PMA/ionomycin. Representative FACS plots, frequencies and average numbers of ex-Treg cells producing IFN-γ after stimulation with PMA/ionomycin at each time point (d8, 15 and day 21). Plots shown were gated on ex-Treg cells. E) For quantification of Ag-specific ex-Treg cells, corneal single cell suspensions were stimulated for 16 h with UV-inactivated HSV-RE, with the addition of brefeldin A for the last 5 h of stimulation. Representative FACS plots shown are gated on ex-Treg cells, T effectors or Treg. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (A–D) and unpaired Student’s t-test (E). Error bars represent means ± SEM (n = 6 – 8 mice). Experiments were repeated at least three times. P≤0.0001(****), P≤0.01(**), P≤0.05(*).

To quantify the cytokine producing abilities of these ex-Treg, single cell suspensions of 3–4 collagen-digested pooled corneas from ocularly HSV-1 infected FM mice were stimulated at different times pi with PMA/ionomycin, followed by an intracellular cytokine detection assay. As shown in figure 1C at days 8 and 21 pi 33% of the ex-Treg became IFN-γ producers but at day 15, which is the peak of the disease, 80% of the ex-Treg were IFN-γ producers. Additionally, similar to ex-Treg numbers, the IFN-γ producing ex-Treg cells peaked at day 15 pi. Of particular interest, the percentage of exFoxp3 cells was increased particularly in the corneas (approx. 50%), as compared to DLN and spleen (approx. 19% and 25% respectively) at day 15pi (Supplementary figure 2A). The frequencies of IFN-γ produced by exFoxp3 cells were also higher in corneas (approx. 80 %) as compared to DLN and spleen (approx. 7% and 16% respectively) when measured at the same time pi (Supplementary figure 2B). Furthermore, intracellular cytokine production by corneal cells stimulated with a UV-inactivated viral Ag revealed a high percentage of ex-Treg (approx. 22%) and minimal Treg that were IFN-γ producing cells at day 15pi (Figure 1E). All these results indicate that a substantial proportion of corneal Treg convert into Th1 ex-Treg after HSV-1 ocular infection. Of interest, some of the ex-Treg were HSV antigen specific indicating that such ex-Treg may have derived from the HSV specific Treg population.

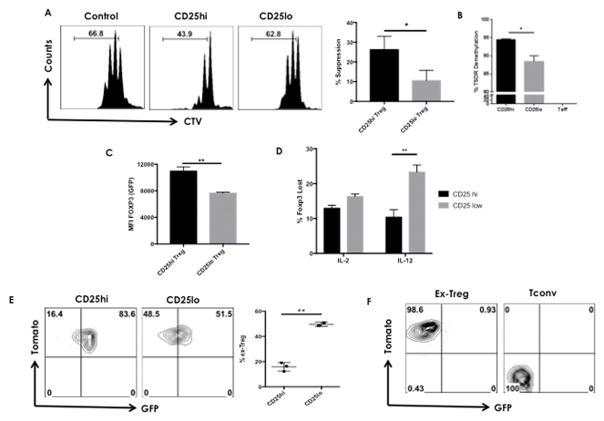

CD25lo Foxp3+CD4+ Treg generate ex-Treg during HSV-1 induced inflammation

Several reports suggest that Treg are comprised of Foxp3-stable CD25hi and Foxp3-unstable CD25lo populations (21, 22, 26). These reports also show that CD25lo Treg have defective suppression, express less Foxp3 expression and had a moderately less demethylated TSDR compared to the CD25hi Treg. Similarly, in our system we could show that HSV-1 immune FACS sorted CD25lo Treg at day 15pi were less suppressive (Figure 2A). In addition, methylation analysis of TSDR region using real-time PCR confirmed that 100% of CD4+Foxp3.GFP− T conv cells had methylated CpG sites, whereas >94% of CpG sites were demethylated in CD25hi Treg cells (Figure 2B). Notably, CD25lo Treg cells also displayed a highly demethylated TSDR but had slightly but significantly lower demethylation than CD25hi Treg cells (~88% compared with ~94%) (Figure 2B). Furthermore, CD25lo Treg also showed less Foxp3 expression as compared to the CD25hi Treg, as measured by MFI (Figure 2C). These results led us to hypothesize that CD25lo Treg might be the main population that harbored uncommitted Treg in SK lesions. To evaluate if such CD25lo Treg were unstable in-vitro, CD4+ GFP+ T cells were sorted into CD25lo and CD25hi cells with purity >95% (Supplementary figure 3) from HSV-1 infected FoxP3-GFP mice at day 15pi and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28+IL-2 (control) or CD3/CD28+IL-12 for 5 days. As shown in figure 2D, in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12, 25% of the CD25lo, but only 10% of the CD25hi Treg lost FoxP3 expression. However, in the control cultures that received IL-2 alone, minimal loss of FoxP3 expression was observed (approx. 10%). These results indicate that pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12 can promote the conversion of antigen experienced CD25lo Treg into ex-Treg.

Figure 2. CD25loFoxp3+CD4+ Treg are unstable Treg cells that convert into ex-Treg in an inflammatory environment.

A–C & E–F) FM mice were infected ocularly with 1× 104 PFU of HSV-1. DLNs and spleens were collected at day 14 pi and CD25lo and CD25hi Treg cells were sorted. A) An equal number of each population (1 × 105 cells) was cultured with CTV-labeled sorted effector T cells (Treg/Teff, 1:1) in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Representative histograms show the extent of CTV dilution at a 1:1 Treg/Teff ratio. Bar graphs show the percent suppression of CD25lo Treg and CD25 Treg at 1:1 ratio to Teff. B) Demethylation of TSDR region at Foxp3 locus of the sorted CD25lo and CD25hi Treg was determined as described in materials and methods. C) Bar graph shows the MFI of FoxP3 expression on CD25lo and CD25hi Treg. D) Sorted CD25lo and CD25hi Treg from day 15 HSV-1 infected FoxP3-GFP mice were exposed to 100U/ml IL-2 or 5ng/ml IL-12 for 5 days. Cells were measured for GFP expression before exposure and after exposure. Histograms represent the frequency of Foxp3 lost by CD25lo and CD25hi Treg exposed to different conditions. E) Sorted CD25lo and CD25hi Treg were adoptively transferred into HSV-1 footpad infected congenic Thy1.1 mice at 24hpi and transferred cells were analyzed for ex-Treg. Representative FACS plots show the frequency of ex-Treg after adoptive transfer. Plots are gated on CD4+Thy1.2+Tomato+ cells. F) Sorted effector T cells and ex-Treg from immunized FM mice were adoptively transferred into HSV-1 footpad infected congenic Thy1.1 mice at 24h pi and transferred cells were analyzed for Treg. Representative FACS plots show the frequency of Treg after adoptive transfer. Plots are gated on CD4+Thy1.2 + cells. Each experiment was repeated at least two times with at least 3 mice per group. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparison test. P≤0.01(**), P≤0.05(*).

To evaluate FoxP3 stability of the two CD25lo and CD25hi Treg populations in vivo, FACS sorted HSV-1 immune Thy1.2 CD25lo and CD25hi Treg (gated on GFP+ cells) from FM mice were adoptively transferred into congenic Thy1.1 mice and these were infected via the footpad with HSV-1 24 hours later. The recipient mice were analyzed for the presence of donor T cells in the popliteal lymph node (PLN) and spleen at day 5 pi by reacting with anti-CD4 and anti-Thy1.2. As is evident from Figure 2E, 50% of the donor CD25lo Treg lost GFP expression and converted into ex-Treg. This compared to only 16.4% in the donor CD25hi Treg in the PLN of recipient animals (Figure 2E). Similar results were found in the spleen (data not shown).

To determine if ex-Treg could be derived from activated conventional T cells that transiently express Foxp3 or if ex-Treg could be converted back into Treg. The same experimental setup as above was used. Accordingly, similar numbers of FACS sorted effector T cells or ex-Treg cells from immunized FM mice were adoptively transferred into congenic Thy1.1 mice and these were infected via the footpad with HSV-1 24 hours later. The recipient mice were analyzed for the presence of donor T cells in the PLN and spleen at day 5 pi by reacting with anti-CD4 and anti-Thy1.2. As is evident from figure 2F, none of effector T cells or the ex-Treg cells showed any conversion into Treg. This suggests that transient upregulation of FoxP3 on effector T cells is not contaminating the ex-Treg population and that the ex-Treg population does not convert back into Treg during HSV-1 induced inflammation.

Taken together, our results show that HSV-1 immune CD25lo Treg showed defective suppression, had a partially methylated TSDR and were highly unstable cells that convert to ex-Treg under inflammatory conditions.

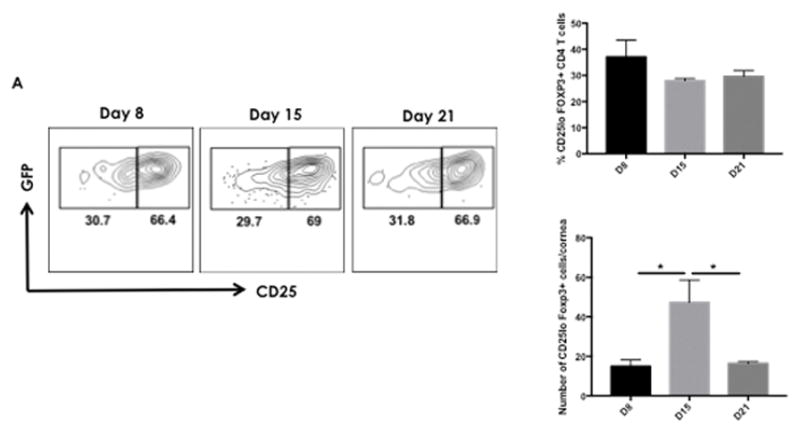

CD25lo Treg were increased in the cornea after HSV-1 ocular infection

To determine if the population of unstable CD25lo Treg increased in the cornea after HSV-1 ocular infection, FoxP3-GFP mice were ocularly infected with HSV-1 and corneas were collected, collagen digested and the recovered cells reacted with anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 antibodies at days 8, 15 and 21 pi. As shown in figure 3A, the frequency of CD25lo Treg remained stable over time, but the numbers of CD25lo Treg increased as the disease progressed and reached a peak at day 15 pi. In addition the numbers of CD25lo Treg reduced at day 21 pi which could be attributed to the reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines at this day as shown previously (27). These results suggest that unstable CD25lo Treg population is present in the cornea at different days post infection.

Figure 3. Unstable CD25lo Treg increase with the progression of disease.

Foxp3 GFP mice were infected ocularly with 1× 104 PFU of HSV-1 and at each time point (d8, 15 and 21) three to four corneas were collected, pooled, and digested with Liberase and analyzed for CD25lo Treg. A) Representative FACS plots, frequencies and average numbers of corneal CD25lo Treg cells at each time point pi. The level of significance was determined by a Student t test (unpaired). Error bars represent means ± SEM (n = 8 – 10 mice). Experiments were repeated at least three times. P≤0.05(*).

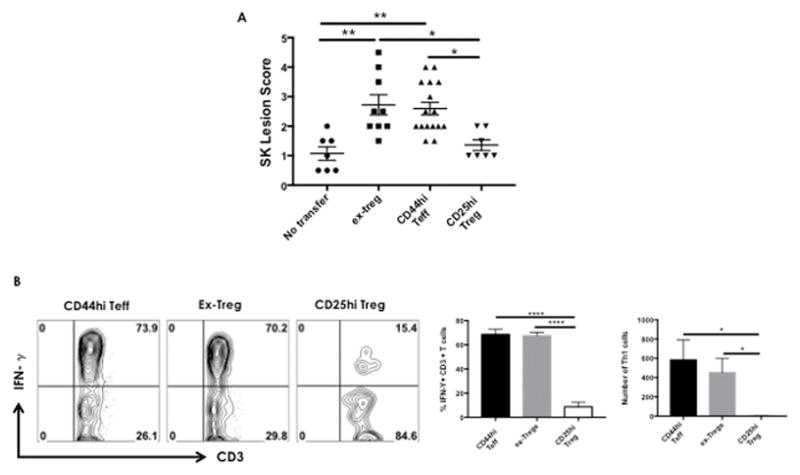

Ex-Treg are pathogenic and can cause SK

Previous results showed the presence of ex-Treg, Treg as well as conventional effector T cells in corneal lesions. To measure and compare the pathogenicity of ex-Treg, Treg and CD44hi T effectors, ex-Treg, CD25hi Treg and CD44hi FoxP3-T effectors were FACS sorted from DLNs and spleens of day 15 post infected FM mice. Equal numbers of each cell population were then transferred into T cell and B cell deficient Rag1−/−, which were infected ocularly 24h later with HSV-1. The recipients were monitored clinically over the next 10 days. Because HSV-1 infected Rag1−/− mice usually develop lethal herpetic encephalitis, infected recipient mice were given a source of anti-HSV-1 antibody (human IVIG) 2 days after infection, which allows mice to survive beyond day 6 pi and ensures optimal HSK development in surviving mice (28). Using this protocol our results showed that CD44hi T effectors and ex-Treg induced similar levels of SK severity (lesion score < 2.5) at day 10 pi (Figure 4A), while the control animals that received no cells or CD25hi Treg showed minimal lesions. In addition, T effectors and ex-Treg cells in subpools of collagen-digested corneas produced similar levels of IFN-γ (approx. 70%) as seen by the ICS assay after PMA/ionomycin stimulation (Figure 4B), while the control animals that received CD25hi Treg showed minimal IFN-γ production (approx. 15%). These results demonstrate that ex-Treg cells can function as pathogenic effector cells producing IFN-γ in the cornea and that these ex-Treg can induce SK with a similar severity to that caused by CD44hi T effector cells.

Figure 4. ex-Treg are pathogenic in-vivo.

FM mice were infected ocularly with 1× 104 PFU of HSV-1. DLNs and spleens were collected at day 15 pi and ex-Treg, CD25hi Treg and CD44hi FoxP3-T effectors cell were FACS sorted. Rag1−/− were ocularly infected with HSV-1 and were divided into groups. One group of mice received 5 × 105 ex-Treg cell at 24hpi. One group of mice received 5 × 105 CD25hi Treg cell at 24hpi. One group of mice received 5 × 105 CD44hi FoxP3-T effectors cell 24h pi and one group received no cells. All mice were treated with IVIG at day 2 pi. A) SK lesion severity at day 10 after infection is shown. B) Mice were sacrificed on day 10 after infection, and corneas were harvested and pooled group wise for the analysis of various cell types. Intracellular staining was conducted to quantify Th1 cells by stimulating them with PMA/ionomycin. Representative FACS plots, frequencies and average numbers of CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ after stimulation with PMA/ionomycin. Plots shown were gated on CD3+CD4+ T cells. Data compiled from two separate experiments consisting of 3–4 animals in each group. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparison test. Error bars represent means ± SEM. P≤ 0.0001(****), P≤0.01(**), P≤0.05(*)

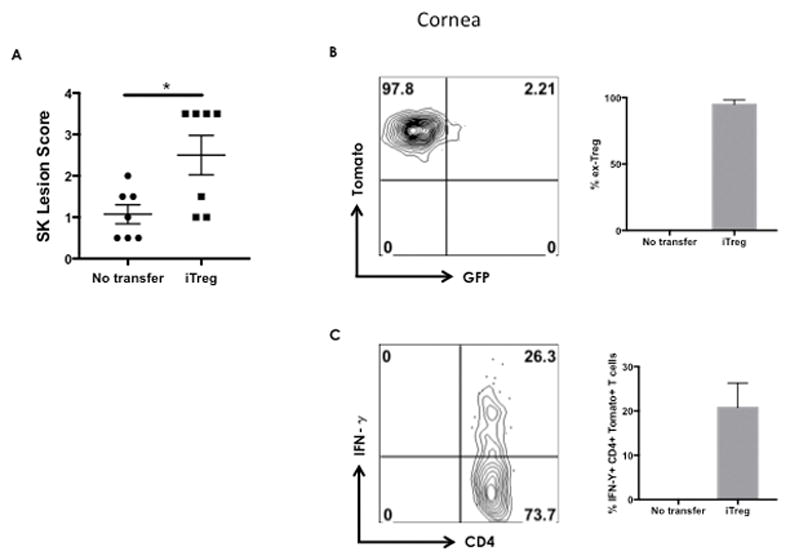

iTreg covert into ex-Treg and induce SK disease in Rag1−/− recipients

Previous reports show that naive T cells converted in-vitro into iTreg cells by TCR stimulation in the presence of IL-2 and TGF-β had methylated CpG sites in the FoxP3 CNS2 region, but could lose Foxp3 expression rapidly (12). However, whether or not FoxP3 instability of in-vitro induced iTreg results in pathogenic ex-Treg during HSV-1 infection remains to be substantiated. To test this possibility iTreg were generated from sorted naïve CD4+T cells from FM mice by stimulating them with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of IL-2 and TGF-β for 5 days. Tomato+ GFP+ iTreg cells were then FACS sorted and adoptively transferred into T cell and B cell deficient Rag1−/− mice 24 hours after ocular infection with HSV-1. Recipients were monitored clinically over the next 10 days. These mice were also given IVIG at day 2pi to protect them from lethal encephalitis as described in the previous section. At day 10 pi typical HSK lesions (score ≥2.5) were evident in the iTreg recipients at the time of sacrifice whereas only minimal lesions were evident at the same time in control animals that were infected but received no cell transfer (Figure 5A). More importantly, 95% of the cells recovered from the corneas of the iTreg recipients lost FoxP3 expression and converted into ex-Treg in the SK lesions (Figure 5B). Moreover, 26% of the infiltrating CD4 T cells in the cornea produced IFN-γ as measured by the ICS assay after PMA/ionomycin stimulation (Figure 5C). This supports the notion that the iTreg had converted into Th1 cells in the SK microenvironment. Taken together our data show that iTreg were highly unstable and could convert into Th1 ex-Treg in an SK inflammatory micro-environment and that these cells contributed to SK expression.

Figure 5. iTreg are pathogenic in-vivo.

A) Naive CD4 T cells purified from FM mice were cultured (1×106 cells/well) with 100U/ml IL-2, 5ng/ml TGFβ and 1μg/ml anti-CD3/CD28, for up to 5 days. Foxp3 GFP+ Tomato+ T cells (iTreg) were FACS sorted. Rag1−/− were ocularly infected with HSV-1 and were divided into two groups. One group of mice received 5 × 105 iTreg cells at 24h pi and one group received no cells. All mice were treated with IVIG at day 2 pi. A) SK lesion severity at day 10 after infection is shown. B) Mice were sacrificed on day 10 after infection, and corneas were harvested and pooled group wise for the analysis of various cell types. Intracellular staining was conducted to quantify Th1 cells by stimulating them with PMA/ionomycin. Representative FACS plots show frequency of ex-Treg and CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ after stimulation with PMA/ionomycin. Plots shown were gated on CD3+CD4+Tomato+ T cells. Data compiled from two separate experiments consisting of 3–4 animals in each group. The level of significance was determined by a Student t test (unpaired). Error bars represent means ± SEM. P≤0.05(*).

iTreg generated in the presence of Vitamin C and RA were highly stable and resistant to conversion into ex-Treg

A previous report had indicated that iTreg generated in the presence of Vitamin C and RA could substantially stabilize FoxP3 expression both in-vitro and in-vivo (29, 30). This occurred in part by demethylating the TSDR region of the Foxp3 locus. Similarly, we could show that iTreg generated in the presence of Vitamin C + RA had an almost completely demethylated TSDR region (90%), whereas, in the control iTreg (without Vitamin C + RA) the TSDR was only minimally demethylated (12%) (Figure 6A). Furthermore, to show that Vitamin C + RA could stabilize iTreg in the face of inflammatory cytokines in the SK system, splenocytes from DO11.10 RAG2−/− animals (ova peptide specific and 98% naïve CD4+ T cells) were cultured in the presence of Treg differentiating conditions (anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation +IL-2 and TGF-β) either in the presence or absence of Vitamin C + RA. After 5 days of culture a few cells were harvested and cell numbers that expressed Foxp3 were recorded. The remaining cells were exposed either to IL-2 or IL-12 (Th1 condition) or IL-6 and TGF-beta (Th17 conditions) for an additional 3 days. FoxP3 expression was analyzed again at this time point and the % Foxp3 expression lost was calculated. In these experiments, IL-2 alone led to minimal loss of Foxp3 expression (approx. 8%), whereas exposure to IL-12 and IL-6 +TGF-β resulted in a significant loss of Foxp3 expression (approx. 30%) in control iTreg. In contrast, iTreg generated in the presence of Vitamin C + RA were significantly more stable and lost minimal (5–10%) Foxp3 expression when exposed to either Th1 or Th17 differentiating conditions (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Vitamin C + RA generated iTreg are highly stable.

A) Naive CD4 T cells purified from Foxp3 GFP male mouse were cultured (500,000 cells/well) with 100U/ml IL-2, 1μg/ml anti-CD3/CD28, 5ng/ml TGFβ and in the presence or absence of Vitamin C and RA for up to 5 days. Foxp3 GFP+ T cells were FACS sorted. Demethylation of TSDR region at Foxp3 locus was determined as described in Materials and methods. B) Splenocytes from DO11.10 RAG2−/− animals were cultured in the presence of 1μg/ml anti-CD3/CD28, 100 U/ml IL-2, 5ng/ml TGF-β in the presence or absence of Vitamin C and RA for 5 days. Then exposed to 100U/ml IL-2 or 5ng/ml IL-12 or 25ng/ml IL-6 and 1ng/ml TGF-beta for another 3 days. Cells were measured for Live CD4+ Foxp3+ cells before exposure and after exposure. Bar graphs show the frequency of Foxp3 lost by cells of control and Vitamin C and RA induced iTreg exposed to different conditions. C) Naive CD4 T cells purified from FM mice were cultured (1 × 106 cells/well) with 100U/ml IL-2, 1μg/ml anti-CD3/CD28, 5ng/ml TGFβ and in the presence or absence of Vitamin C and RA for 5 days. Control unstable iTreg and Vitamin C + RA generated stable Treg were adoptively transferred into HSV-1 ocularly infected congenic Thy1.1 mice at 72hpi and transferred cells were analyzed for ex-Treg cells. Representative FACS plots show the frequency of ex-Treg after adoptive transfer. Plots are gated on CD4+Thy1.2+Tomato+ cells. Each experiment was repeated at least two times with at least 3 mice per group. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparison test. Error bars represent means ± SEM. P≤ 0.0001(****), P≤0.001 (***), P≤0.01(**), P≤0.05(*).

To evaluate in vivo stability of Foxp3 expression of iTreg cells generated in the presence of Vitamin C + RA, naive CD4+ T cells from FM mice were cultured in the presence of Treg differentiating conditions (anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation +IL-2 and TGF-β) either in the presence or absence of Vitamin C + RA. The control iTreg and Vitamin C + RA generated iTreg were adoptively transferred into congenic, HSV-1 ocularly infected Thy1.1 mice at 72hpi. Recipient mice were then analyzed for the presence of donor T cells in the DLN and spleen at day 15 pi by reacting with anti-CD4 and anti-Thy1.2. As evident from Figure 6C, 26–28% of the donor control iTreg lost GFP expression and converted into ex-Treg. This compared to a loss of only 3–7% in the recipients of Vitamin C + RA generated iTreg.

These results demonstrate that HSV-1 induced inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IL-6 could promote the conversion of iTreg into ex-Treg and this conversion could be markedly inhibited when iTreg were generated in the presence of Vitamin C and RA.

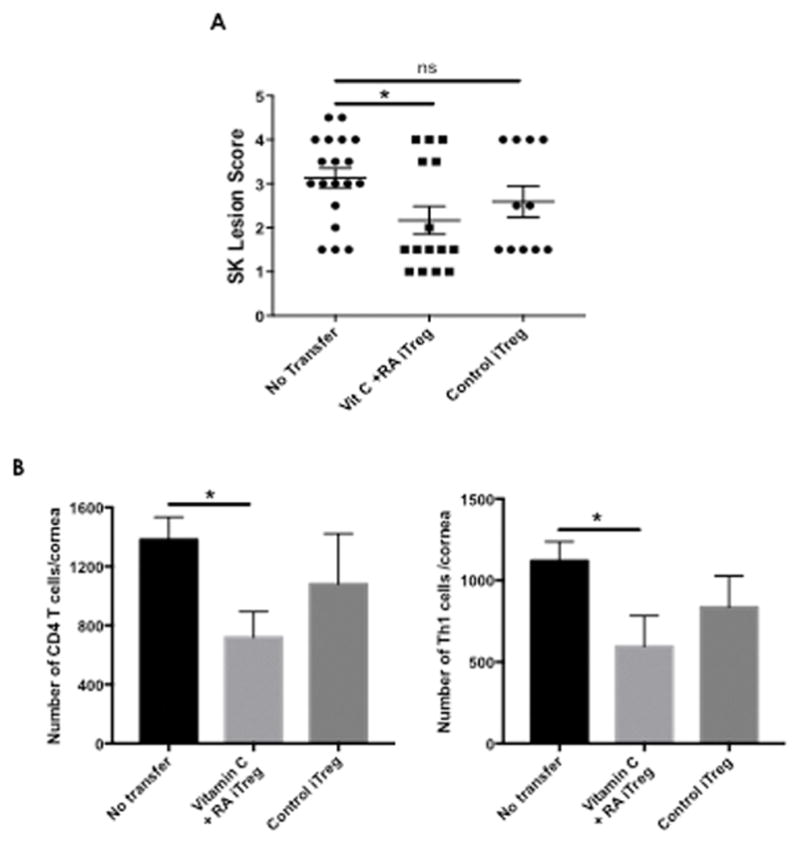

Vitamin C+ RA stabilized iTreg more efficiently suppress SK lesions than do control iTreg

To evaluate if iTreg populations stabilized in vitro by induction in the presence of Vitamin C + RA were more effective at controlling SK lesions than un-stabilized iTreg, adoptive experiments were performed. The donor cell populations used to generate the both stabilized iTreg and control unstable iTreg were from DO11.10 RAG2−/− (OVA specific) mice as described in materials and methods. These mice were used because they provide a highly enriched naïve CD4 T cell population (5). Groups of Balb/c mice received the adoptive transfer 3 days after ocular infection and disease severity were followed until termination on day 15 pi. As shown in Figure 7A mice that received the stabilized iTreg population expressed significantly reduced lesions compared to those that received no iTreg. Similarly mice that received the stabilized iTreg population showed a trend of reduced lesions compared to those that received unstable control iTreg population although no significance was achieved. Additionally, there were 1.8 fold reduced number of CD4+T cells and Th1 cells infiltrating the cornea in the mice that received the stabilized iTreg compared to those that received no iTreg (Figure 7B). Taken together, our data demonstrate that stabilized Vitamin C +RA generated iTreg were better at suppressing SK lesions compared to un-stabilized control iTreg.

Figure 7. Vitamin C+ RA generated Treg suppress SK lesions better than control iTreg.

Balb/c mice ocularly infected with 1×105 PFU of HSV-1 were divided into groups. One group of mice received stabilized Vitamin C + RA generated iTreg (10 × 106) at day 3 after infection. One group of mice received control unstable iTreg (10 × 106) at day 3 after infection, and one group of mice received no transfer of cells. Disease severity and immune indicators in the cornea were evaluated at day 15 after infection. A) SK lesion severity at day 15 after infection are shown. B) Mice were sacrificed on day 15 after infection, and corneas were harvested and pooled group wise for the analysis of various cell types. Intracellular staining was conducted to quantify Th1 cells by stimulating them with PMA/ionomycin. The bar graph represents total numbers of corneal infiltrating CD4+ T cells, and Th1cells of mice that received no transfer, control iTreg or Vitamin C + RA generated iTreg. Each experiment was repeated at least two times with at least 8 mice per group. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparison test. Error bars represent means ± SEM. P≤0.05(*)

Discussion

In this report, using fate mapping mice, we showed that Treg present in the cornea during a viral induced inflammatory reaction are unstable and can become ex-Treg with a Th1 phenotype. Interestingly, some of these ex-Treg were shown to be HSV antigen specific. We also showed that the CD25lo Treg were highly plastic and converted into ex-Treg more readily than the stable CD25hi Treg subpopulation. Interestingly, the unstable CD25lo Treg were present in the cornea and this population increased with the progression of disease and followed the same pattern as the appearance of ex-Treg. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12 and IL-6 was in part responsible for the generation of ex-Treg during SK development. Furthermore, ex-Treg displayed equivalent disease causing potential as effector T cells when cells were adoptively transferred in HSV-1 infected Rag1−/− animals. We also showed that the population of Treg generated in vitro from naïve CD4 T cells were highly unstable when transferred into lymphopenic Rag1−/− recipients with almost 95% of the iTreg converting into ex-Treg. Finally, we could show that Treg generated in-vitro in the presence of Vitamin C and RA produced a population with increased stability when exposed to an inflammatory environment either in-vitro or in-vivo. More importantly, the stabilized iTreg population was more efficient at reducing SK lesions as compared to control unstable iTreg when adoptively transferred in day 3 HSV-1 infected mice. Taken together our results demonstrate that instability of Treg function occurs in the inflammatory environment of a virus-induced lesion and that the converted ex-Treg can also participate in tissue damage, an event that may help explain chronicity.

It is becoming increasingly evident that diverse environmental stimuli can affect Treg stability acting by modulating epigenetic programing or posttranslational modifications (16). For example, proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, IL-6 and IL-1β could trigger a signaling pathway through their receptors on Treg. This could cause a loss of Foxp3 expression by several mechanisms. Thus, IL-1β induces the ubiquitinase enzyme Stub1 that permits the ubiquitination of FoxP3 and its degradation (31). In addition, IL-6 leads to a STAT3-dependent decrease in Foxp3 protein and mRNA accompanied by increased DNMT1 expression. This effect results in methylation of the TSDR region of the Foxp3 gene, as well as diminished acetylation of histone 3 at the upstream promoter region of the gene (19, 32). Additionally, IL-12 can activate the IL-12R-β2/STAT4-mediated signaling pathway, which causes the polarization towards the Th1 type Treg and loss of FoxP3 expression (33, 34). In our report we showed that IL-12 and IL-6 could cause the loss of FoxP3 expression especially in CD25lo Treg and iTreg populations. A cytokine that has been shown to stabilize Treg is IL-2 by signaling through the IL-2R (CD25) on the Treg cells (20, 21, 26). Accordingly, several recent studies in mice and humans showed that robust CD25 expression on Treg correlated with enhanced FoxP3 expression, suppressive function and stability of the Treg phenotype (21, 35, 36). Similarly, we observed that the CD25lo population of Treg in SK system were less suppressive and were highly unstable with 50% of them losing FoxP3 expression when adoptively transferred into HSV-1 footpad infected WT mice.

An interesting observation was that the unstable CD25lo Treg infiltrated the cornea at different times post HSV-1 infection and could have contributed in part to the generation of ex-Treg. However, some question whether ex-Treg observed in some autoimmune settings represent the loss of Foxp3 by bonafide Treg, or whether they represent conventional proinflammatory T cells that transiently induced endogenous FoxP3 and so induced FoxP3-Cre recombinase, leading to activation of the lineage tracer (Tomato) expression. We favor the notion that in our system of SK the ex-Treg represents true ex-Treg and not proinflammatory T cells that transiently expressed FoxP3 based largely on the results of adoptive transfer experiments. Accordingly, adoptive transfer of Foxp3-CD4+ T cells from FM mice into HSV-1 infected WT mice did not show any conversion to ex-Treg (Figure 1F), thus showing that T conv cells transiently expressing FoxP3 did not occur in our system or that the transient expression of Foxp3 was not enough to induce FoxP3-Cre recombinase. In addition, adoptive transfer of FACS sorted CD25lo Treg from HSV-1 infected FM mice into Thy1.1 mice that were infected with HSV-1 in the footpad showed conversion of these Treg into ex-Treg. This would support the idea that the conversion of Treg to ex-Treg is occurring in the infectious disease system we investigated.

Another interesting and noteworthy observation was that the ex-Treg in the SK lesions included cells that were viral antigen specific. These data indicate that the high frequency of ex-Treg might be generated from viral specific Treg and not other polyclonal Treg populations. Such observations are in line with the findings by the Bluestone group that showed that MOG specific Treg were highly plastic as compared to the polyclonal Treg during autoimmune inflammation (37). Additionally, while the full range of specificities expressed by Treg cells could not be established, it is conceivable that some of the ex-Treg could also recognize self-antigens of corneal origin and contribute to SK pathogenesis. These issues need to be addressed further and studies are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

Explanations for Treg plasticity include epigenetic and posttranslational modifications (16). Accordingly, demethylation of CpG islands in the TSDR region of the Foxp3 locus is considered a hallmark of Treg stability and functionality (12). Demethylation of the CpG islands in the TSDR region ensures that critical transcription factors such as Foxp3 and Runx1–Cbf-β complex, to bind to the TSDR region and maintain Foxp3 activity in the progeny of dividing Treg (14, 38). Epigenetic regulation of stable Foxp3 expression is also regulated by FoxP3 acetylation (15, 39, 40). Previous reports show that the TSDR region is demethylated in thymic Treg expressing Foxp3, but in iTreg TSDR region is fully methylated making them unstable (12). We could also show that iTreg have a fully methylated TSDR and displayed plasticity when adoptively transferred in Rag1−/− mice. Moreover, almost 95% of these iTreg lost FoxP3 expression and became ex-Treg with the Th1 phenotype. Post-translation modifications that regulate Treg plasticity include phosphorylation and ubiquitination of FoxP3 (16) and these events are being further explored in our system.

It is important from a lesion management perspective to find appropriate measures to limit or prevent Treg plasticity. Approaches under consideration include agents that cause demethylation of the TSDR region of the FoxP3 gene such as Azacytidine, which was investigated for its effects on SK lesion severity (41). The results showed that Azacytidine therapy after disease process had been initiated effectively diminished lesions. Other agents that prevent methylation of the TSDR region or promote acetylation of the FoxP3 gene may also show therapeutic promise to contain Treg plasticity (16). Vitamin C induces CNS2 demethylation in iTreg in a ten-eleven-translocation 2 (Tet2)/Tet3-dependent manner to increase the stability of Foxp3 expression (29, 30). Similarly, RA also has a stabilizing effect on Foxp3 protein expression. It acts by suppressing IL-1 receptor upregulation, and accelerating IL-6 receptor downregulation along with increasing histone acetylation of the FoxP3 TSDR without affecting the methylation status of the TSDR region (42).

In the present communication we explored the value of Vitamin C and RA and could show that iTreg generated in the presence of Vitamin C and RA were more stable both in-vitro and in-vivo. Accordingly, when iTreg were adoptively transferred into WT HSV-1 ocularly infected mice at day 3 pi (a time at which levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines is high in the DLN), almost 30% of these iTreg lost Foxp3 expression. In contrast when iTreg were generated in the presence of Vitamin C and RA conversion was minimal (3–7%). Similar stabilizing effects were observed when iTreg generated with Vitamin C and RA, were exposed to proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 or IL-12 in-vitro. Moreover, these results might also explain previous findings that adoptive transfer of iTreg before infection effectively controlled SK lesion development yet transfers given later when the proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 were highly elevated were without notable lesion control (5). Our current finding explains this phenomenon since many iTreg converted and become ex-Treg without regulatory activity. Interestingly, we could stop this plasticity by generating iTreg in the presence of Vitamin C + RA and more importantly adoptive transfer of stabilized Vitamin C+ RA generated Treg suppressed SK lesions more efficiently than the control unstable iTreg when transferred to day 3 HSV-1 infected mice. It remains to be evaluated if Vitamin C + RA could stabilize CD25lo Treg and if the combination of Vitamin C and RA treatment in-vivo might hold promise as a therapeutic means of controlling virus induced inflammatory lesions.

Our results indicate that conversion of Treg or iTreg into Th1 cells may have a critical role in the severity of viral induced inflammatory lesions. Blocking pathways to prevent the conversion of these Treg into pathogenic T cells could represent a useful approach to control an important cause of human blindness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jeffery Bluestone for providing the Foxp3-GFP-Cre mice.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant EY 005093.

References

- 1.Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niemialtowski MG, Rouse BT. Predominance of Th1 cells in ocular tissues during herpetic stromal keratitis. J Immunol. 1992;149:3035–3039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendricks RL, Tumpey TM, Finnegan A. IFN-gamma and IL-2 are protective in the skin but pathologic in the corneas of HSV-1-infected mice. J Immunol. 1992;149:3023–3028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suvas S, Azkur AK, Kim BS, Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control the severity of viral immunoinflammatory lesions. J Immunol. 2004;172:4123–4132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sehrawat S, Suvas S, Sarangi PP, Suryawanshi A, Rouse BT. In vitro-generated antigen-specific CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells control the severity of herpes simplex virus-induced ocular immunoinflammatory lesions. J Virol. 2008;82:6838–6851. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00697-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veiga-Parga T, Suryawanshi A, Mulik S, Gimenez F, Sharma S, Sparwasser T, Rouse BT. On the role of regulatory T cells during viral-induced inflammatory lesions. J Immunol. 2012;189:5924–5933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, Penaranda C, Martinez-Llordella M, Ashby M, Nakayama M, Rosenthal W, Bluestone JA. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Bluestone JA. Regulatory T cells: stability revisited. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyao T, Floess S, Setoguchi R, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Waldmann H, Huehn J, Hori S. Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sujino T, London M, Hoytema van Konijnenburg DP, Rendon T, Buch T, Silva HM, Lafaille JJ, Reis BS, Mucida D. Tissue adaptation of regulatory and intraepithelial CD4(+) T cells controls gut inflammation. Science. 2016;352:1581–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakaguchi S, Vignali DA, Rudensky AY, Niec RE, Waldmann H. The plasticity and stability of regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nri3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, Schlawe K, Chang HD, Bopp T, Schmitt E, Klein-Hessling S, Serfling E, Hamann A, Huehn J. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huehn J, Polansky JK, Hamann A. Epigenetic control of FOXP3 expression: the key to a stable regulatory T-cell lineage? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:83–89. doi: 10.1038/nri2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Loosdregt J, Vercoulen Y, Guichelaar T, Gent YY, Beekman JM, van Beekum O, Brenkman AB, Hijnen DJ, Mutis T, Kalkhoven E, Prakken BJ, Coffer PJ. Regulation of Treg functionality by acetylation-mediated Foxp3 protein stabilization. Blood. 2010;115:965–974. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbi J, Pardoll D, Pan F. Treg functional stability and its responsiveness to the microenvironment. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:115–139. doi: 10.1111/imr.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodge DR, Cho E, Copeland TD, Guszczynski T, Yang E, Seth AK, Farrar WL. IL-6 enhances the nuclear translocation of DNA cytosine-5-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) via phosphorylation of the nuclear localization sequence by the AKT kinase. Cancer genomics & proteomics. 2007;4:387–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samanta A, Li B, Song X, Bembas K, Zhang G, Katsumata M, Saouaf SJ, Wang Q, Hancock WW, Shen Y, Greene MI. TGF-beta and IL-6 signals modulate chromatin binding and promoter occupancy by acetylated FOXP3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14023–14027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806726105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal G, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic mechanisms of regulation of Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2009;114:3727–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Q, Kim YC, Laurence A, Punkosdy GA, Shevach EM. IL-2 controls the stability of Foxp3 expression in TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2011;186:6329–6337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komatsu N, Mariotti-Ferrandiz ME, Wang Y, Malissen B, Waldmann H, Hori S. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: a committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1903–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811556106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huynh A, DuPage M, Priyadharshini B, Sage PT, Quiros J, Borges CM, Townamchai N, Gerriets VA, Rathmell JC, Sharpe AH, Bluestone JA, Turka LA. Control of PI(3) kinase in Treg cells maintains homeostasis and lineage stability. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:188–196. doi: 10.1038/ni.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cottrell S, Jung K, Kristiansen G, Eltze E, Semjonow A, Ittmann M, Hartmann A, Stamey T, Haefliger C, Weiss G. Discovery and validation of 3 novel DNA methylation markers of prostate cancer prognosis. The Journal of urology. 2007;177:1753–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veiga-Parga T, Suryawanshi A, Rouse BT. Controlling viral immuno-inflammatory lesions by modulating aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002427. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhela S, Mulik S, Gimenez F, Reddy PB, Richardson RL, Varanasi SK, Jaggi U, Xu J, Lu PY, Rouse BT. Role of miR-155 in the Pathogenesis of Herpetic Stromal Keratitis. Am J Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komatsu N, Okamoto K, Sawa S, Nakashima T, Oh-hora M, Kodama T, Tanaka S, Bluestone JA, Takayanagi H. Pathogenic conversion of Foxp3+ T cells into TH17 cells in autoimmune arthritis. Nat Med. 2014;20:62–68. doi: 10.1038/nm.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suryawanshi A, Veiga-Parga T, Rajasagi NK, Reddy PB, Sehrawat S, Sharma S, Rouse BT. Role of IL-17 and Th17 cells in herpes simplex virus-induced corneal immunopathology. J Immunol. 2011;187:1919–1930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhela S, Mulik S, Reddy PB, Richardson RL, Gimenez F, Rajasagi NK, Veiga-Parga T, Osmand AP, Rouse BT. Critical role of microRNA-155 in herpes simplex encephalitis. J Immunol. 2014;192:2734–2743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue X, Trifari S, Aijo T, Tsagaratou A, Pastor WA, Zepeda-Martinez JA, Lio CW, Li X, Huang Y, Vijayanand P, Lahdesmaki H, Rao A. Control of Foxp3 stability through modulation of TET activity. J Exp Med. 2016;213:377–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasidharan Nair V, Song MH, Oh KI. Vitamin C Facilitates Demethylation of the Foxp3 Enhancer in a Tet-Dependent Manner. J Immunol. 2016;196:2119–2131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z, Barbi J, Bu S, Yang HY, Li Z, Gao Y, Jinasena D, Fu J, Lin F, Chen C, Zhang J, Yu N, Li X, Shan Z, Nie J, Gao Z, Tian H, Li Y, Yao Z, Zheng Y, Park BV, Pan Z, Zhang J, Dang E, Li Z, Wang H, Luo W, Li L, Semenza GL, Zheng SG, Loser K, Tsun A, Greene MI, Pardoll DM, Pan F, Li B. The ubiquitin ligase Stub1 negatively modulates regulatory T cell suppressive activity by promoting degradation of the transcription factor Foxp3. Immunity. 2013;39:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger EP, Reid SP, Levy DE, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182:259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch MA, Thomas KR, Perdue NR, Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Campbell DJ. T-bet(+) Treg cells undergo abortive Th1 cell differentiation due to impaired expression of IL-12 receptor beta2. Immunity. 2012;37:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall AO, Beiting DP, Tato C, John B, Oldenhove G, Lombana CG, Pritchard GH, Silver JS, Bouladoux N, Stumhofer JS, Harris TH, Grainger J, Wojno ED, Wagage S, Roos DS, Scott P, Turka LA, Cherry S, Reiner SL, Cua D, Belkaid Y, Elloso MM, Hunter CA. The cytokines interleukin 27 and interferon-gamma promote distinct Treg cell populations required to limit infection-induced pathology. Immunity. 2012;37:511–523. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hori S. Developmental plasticity of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, Mathian A, Nakahata T, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M, Amoura Z, Gorochov G, Sakaguchi S. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Martinez-Llordella M, Zhou X, Anthony B, Rosenthal W, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Bluestone JA. Self-antigen-driven activation induces instability of regulatory T cells during an inflammatory autoimmune response. Immunity. 2013;39:949–962. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudra D, Egawa T, Chong MM, Treuting P, Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Runx-CBFbeta complexes control expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 in regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1170–1177. doi: 10.1038/ni.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li B, Samanta A, Song X, Iacono KT, Bembas K, Tao R, Basu S, Riley JL, Hancock WW, Shen Y, Saouaf SJ, Greene MI. FOXP3 interactions with histone acetyltransferase and class II histone deacetylases are required for repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4571–4576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700298104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao R, de Zoeten EF, Ozkaynak E, Chen C, Wang L, Porrett PM, Li B, Turka LA, Olson EN, Greene MI, Wells AD, Hancock WW. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/nm1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varanasi SK, Reddy PB, Bhela S, Jaggi U, Gimenez F, Rouse BT. Azacytidine treatment inhibits the progression of Herpes Stromal Keratitis by enhancing regulatory T cell function. J Virol. 2017 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02367-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu L, Lan Q, Li Z, Zhou X, Gu J, Li Q, Wang J, Chen M, Liu Y, Shen Y, Brand DD, Ryffel B, Horwitz DA, Quismorio FP, Liu Z, Li B, Olsen NJ, Zheng SG. Critical role of all-trans retinoic acid in stabilizing human natural regulatory T cells under inflammatory conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3432–3440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408780111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.