Abstract

Avoidance behavior in clinical anxiety disorders is often a decision made in response to approach-avoidance conflict, resulting in a sacrifice of potential rewards to avoid potential negative affective consequences. Animal research has a long history of relying on paradigms related to approach-avoidance conflict to model anxiety-relevant behavior. This approach includes punishment-based conflict, exploratory, and social interaction tasks. There has been a recent surge of interest in the translation of paradigms from animal to human, in efforts to increase generalization of findings and support the development of more effective mental health treatments. This article briefly reviews animal tests related to approach-avoidance conflict and results from lesion and pharmacologic studies utilizing these tests. We then provide a description of translational human paradigms that have been developed to tap into related constructs, summarizing behavioral and neuroimaging findings. Similarities and differences in findings from analogous animal and human paradigms are discussed. Lastly, we highlight opportunities for future research and paradigm development that will support the clinical utility of this translational work.

Keywords: approach-avoidance conflict, fear, anxiety, decision-making, translational

Introduction

Approach avoidance conflict has been described as situations involving “opposing and concomitant tendencies of desire…and of fear” [Millan, 2003] and has long been implicated as an important construct related to the experience of anxiety. There has been a surge of recent translational work related to approach-avoidance conflict, providing a potential link between findings from animal conflict paradigms and human behavior and symptomatology. The goal of the current review is to summarize findings from this research and provide potential paths towards furthering the clinical relevance of such translational work.

Animal research has been instrumental in characterizing potential neural substrates as well as pharmacological targets and treatments relevant for anxiety (Kalueff, Wheaton, & Murphy, 2007; Kumar, Bhat, & Kumar, 2013; Millan, 2003). Before human neuroimaging, animal research and human lesion studies were the primary methods for advancing neurobiological understanding of mental health. Animal research relies heavily upon behavioral tests and models that are thought to represent at least some aspect of mental health disorders. Beyond face validity, these paradigms have at least some predictive utility in terms of identifying pharmacologic agents or behavioral interventions that may be beneficial for human suffering (Cryan & Holmes, 2005; Millan, 2003; Millan & Brocco, 2003). The utility of animal paradigms is perhaps more evident within the anxiety disorders literature than other areas, with one of the prime examples being the translation of fear learning as modeled in animals to inform exposure therapy as implemented in humans (Craske, Hermans, & Vansteenwegen, 2006; Hermans, Craske, Mineka, & Lovibond, 2006; Hofmann, 2007, 2008; Vervliet, Craske, & Hermans, 2013). Animal research offers the experimental control to test neurobehavioral theories with a degree of control and precision that may not always be possible or ethical with human research. Thus, the use of animal research to inform clinical psychology work is incredibly important for continued advancement of the field.

Given the above, the ability to generalize findings (or test for generalization) from animal to human work is paramount. However, there are many obstacles for such generalization. First, it is often difficult to identify which animal models or paradigms are most relevant for which human mental health disorders or symptoms (e.g., generalized anxiety versus panic, social anxiety, or even depression). Second, when various pharmacologic agents or manipulations show promise in animal models, it is difficult to identify which have the greatest potential for clinical treatment in human populations (Steckler, Stein, & Holmes, 2008). Third, it is not fully understood how neural targets identified in animal research generalize to the human brain that has non-equivocal differences in structure (e.g., the expansive prefrontal cortex) (Van der Worp et al., 2010). In addressing these challenges, we are often left with trying to compare apples to oranges, such as, comparing (a) how animal behavior changes with pharmacologic or behavioral manipulations to (b) how human self-report of symptoms changes with pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic intervention. Even when using neuroimaging, we are often comparing neural responses to passive viewing paradigms (i.e., symptom provocation studies) to how animal behavior changes with ablations or neurotoxic lesions. All too often, researchers must attempt to translate directly from animal studies to large clinical safety or efficacy studies without any bridging human research to more directly assess the translational potential of such findings (Steckler et al., 2008). In turn, animal researchers are faced with designing animal behavioral studies based on imperfect diagnostic profiles and self-report symptom dimensions.

The use of quantitative human behavioral paradigms that can objectively capture aspects of psychological disorders can be a powerful tool for translation of animal to human (or human back to animal) findings (Delgado, Olsson, & Phelps, 2006; Kumar et al., 2013; Young, Minassian, Paulus, Geyer, & Perry, 2007). Such paradigms are often developed from clinical or cognitive understanding of human function, which then leaves it to animal researchers to attempt to translate this into a viable animal test [as has been done with the continuous performance task; (McKenna, Young, Dawes, Asgaard, & Eyler, 2013; Young et al., 2013)]. An additional strategy is to develop human analogues to currently-used animal paradigms. Here, we focus on opportunities for this latter strategy, with particular attention to paradigms that have been utilized to identify underlying neural substrates.

Approach-Avoidance Conflict

Prominent theories of motivated behavior propose three major systems: (1) a behavioral activation system, elicited by appetitive or rewarding stimuli, (2) a fight, flight, freeze system, elicited by threatening or aversive stimuli, and (3) a behavioral inhibition system, elicited by conflict between the other two systems, or approach-avoidance conflict (Corr, 2013; McNaughton & Gray, 2000). Approach-avoidance conflict arises when the same action is associated with both reward and punishment. Approach-avoidance conflict poses a unique decisional challenge for comparing the value of available options, because individuals must not only integrate information concerning the value of potential rewards and punishments, but also the likelihood and magnitude of those potential outcomes (Aupperle & Paulus, 2010; Quartz, 2009; Rolls & Grabenhorst, 2008). The importance of examining such conflict situations (in addition to fear responses alone) is apparent from animal research. For example, in rodent decision-making tasks amphetamine stimulates reward-seeking behavior when punishment is rare/non-existent, but drives avoidance behavior when punishments are prominent (Orsini, Moorman, Young, Setlow, & Floresco, 2015).

As we have discussed previously (Aupperle & Paulus, 2010), avoidance behavior in clinical anxiety disorders most often involves a decision to sacrifice potential rewards in order to avoid potential negative consequences. Avoidance that does not involve the sacrifice of potential rewards obviously exists, but would most likely not lead to a level of distress that would lead to an individual seeking treatment. For example, the fight, flight, freeze system may be highly relevant for panic attacks (i.e., acute fear responses to a situation); however, panic disorder only becomes a clinical problem when an individual starts sacrificing potential positive outcomes (e.g., not attending social events) in order to avoid the potential negative outcome of panic. For generalized anxiety disorder, overt avoidance behavior in response to acutely feared situations is often difficult to identify. Instead, individuals may engage in effortful behaviors (e.g., reassurance seeking) that allow them to continue approaching situations (e.g., going to work) while simultaneously preventing potentially feared negative outcomes. Therefore, approach-avoidance conflict and the behavioral inhibition system (rather than only the fear-flight-freeze system) may be particularly relevant for the understanding and treatment of anxiety disorders.

Animal research has a long history of relying on conflict- and exploratory-related paradigms to model anxiety. While human research has a long history of research dedicated to understanding approach and avoidance drives, much of this research has relied upon self-report measures and/or has focused on situations in which these two drives are not simultaneously occurring. There has recently been a surge of interest in developing conflict and exploratory paradigms that may have translational value in relation to animal tests, and that may be helpful in assessing anxiety-relevant conflict decisions and avoidance behavior. Below, we briefly summarize each of these types of animal paradigms, as well as the relevant neural networks and effects of anxiolytic medications (as this research may hold particular relevance for intervention efforts in humans). We then review paradigms that have been specifically developed to tap into related constructs in humans and summarize any neurobiological findings. Lastly, we highlight opportunities for future research and paradigm development to fill the gaps of this translational work.

Fear conditioning and extinction has served as an exemplary model of translational research in anxiety (Craske et al., 2006; Delgado et al., 2006; Hermans et al., 2006; Krypotos, Effting, Arnaudova, Kindt, & Beckers, 2014; Lommen, Engelhard, & van den Hout, 2010; Vervliet et al., 2013; van Meurs, Wiggert, Wicker, & Lissek, 2014). In these paradigms, subjects are typically presented with neutral stimuli either paired or not paired with an aversive event (e.g., delivery of shock) and behavioral and physiological outcomes are assessed. However, these paradigms are more relevant for the fight, flight, and freeze system rather than approach-avoidance conflict and either do not measure avoidance behavior per se (instead relying upon other behavioral and physiological responses, such as startle, eye blink, etc.), or do not examine avoidance behavior in the context of potential simultaneous reward. Similarly, passive viewing paradigms used during neuroimaging studies in humans only have indirect implications for avoidance, as behavioral responses are not assessed. Readers are referred to reviews related to these constructs and types of paradigms (Etkin & Wager, 2007; Sergerie, Chochol, & Armony, 2008; Shin & Liberzon, 2010; Vuilleumier & Pourteois, 2007). In this review, we focus on paradigms specifically measuring behavior in response to approach-avoidance conflict relevant decisions. While we do not claim to provide an exhaustive review of every test or model, we attempt to focus on categories of paradigms we feel may be particularly relevant for anxiety disorders, including (a) punishment-induced conflict paradigms, which involve situations in which the same behavior is associated with both reward and punishment, (b) exploratory conflict paradigms, which involve situations where there is both a desire to explore the environment as well as fear of the unknown, and (c) social interaction conflict paradigms, which involve conflict between social affiliation/exploration and fear of potential social threat or novelty. For a full review of animal paradigms relevant for anxiety see Kumar et al. (2013) and Millan (2003).

Animal Paradigms

A number of paradigms have been utilized to assess approach-avoidance conflict behaviors in animals, including punishment-induced, exploratory, and social interaction conflict paradigms. These paradigms are reviewed in regards to methodology, providing a foundation of knowledge for the reader to understand how they can be translated to human populations. In addition, we briefly review findings regarding brain regions that may be involved and the impact of anxiolytics on animal behavior, as these findings are crucially important when considering the clinical translation of findings from animal to human.

Punishment-Induced Conflict Paradigms

Punishment-induced conflict tasks have been used extensively as models of anxiety and for characterizing anxiolytic agents (Griebel & Holmes, 2013; Millan, 2003; Millan & Brocco, 2003). The most commonly used are the Vogel and Geller-Seifter tasks. In Vogel conflict tests, water-deprived rodents are placed in a Plexiglass compartment with a water tube. When the rodent licks the tube a certain number of times (i.e., 20 times), a shock is administered to the feet. Thus, the same behavior (licking) is associated with a reward (water) and a punishment (shock), creating a conflict in behavior. The number of shocks delivered (i.e. number of times the animal approaches the conflict outcome) during a specified time period (i.e., 3 min) is recorded. In Geller-Seifter conflict tasks, rodents are deprived of food and then are trained to press a lever for food pellets. During periods of threat, an electric shock is delivered after they press the lever a certain number of times (i.e., 20 times). The response rate of the animal is then recorded. Conditioned suppression tests are also often categorized with the above conflict tests. These tasks involve delivering a conditioned stimulus (e.g., a tone paired with a shock) to a rodent who is lever pressing for food and the resulting freezing response (and delay of licking behavior) is recorded. These tests involve a conflict between two incompatible responses and have obvious relevance for understanding anxiety. However, as these tasks do not specifically measure deliberate avoidance of stimuli associated with reward due to potential punishment, they are not included in the current review (see previous reviews; Kumar et al., 2013; Millan, 2003).

Exploratory Paradigms

Exploratory paradigms create conflict between the innate drive to explore novel environments and fear of potential unknown threats. In the elevated plus-maze task, animals are placed in the center platform on an apparatus consisting of two open arms (no side walls) and two enclosed arms. Frequency of open arm entries and duration of time spent in open arms is recorded. There are various versions (e.g., elevated t-maze), all of which characterize behavior when animals are faced with the desire to explore their surroundings and concurrent desire to avoid potential danger and unfamiliarity of the exposed arms. While originally developed to assess risk-preference behavior, reduced willingness to explore open arms is commonly thought to be associated with an anxiety-related response (Carobrez & Bertoglio, 2005; Kumar et al., 2013; Treit, Engin, & McEown, 2009).

The open field test consists of a square open field area with the surface divided into equal-sized squares (e.g., 16 squares). The animals are placed in the center and behavior is recorded for a specified time period (e.g., five minutes). Frequency and duration of time in the center (which may involve greater predatory threat for rodents) and periphery of the open field, number of squares entered (as a measure of distance traveled), and rearing on back two legs, is recorded. Reduced willingness to enter the center (thigmotaxis), and less rearing behavior is associated with an anxiety-related response (Kumar et al., 2013; Lister, 1990; Prut & Belzung, 2003).

Animal tasks involving activity chambers allow for testing of exploratory activity distinct from locomotor activity. Hole board tests consist of an apparatus similar to the open field, but with holes in the floor of the area. In addition to locomotor activity and rearing, as in the open field test, exploratory activity is measured via frequency and duration of head dipping into these holes (Kumar et al., 2013). A variety of versions of activity chambers have been created and have become more sophisticated with regard to (1) relying on the use of cameras and infrared beams to automatically track behavior and (2) developing more specific measures to quantify quality and organization of behavior. An example is the rodent behavioral pattern monitor (BPM) developed by Geyer and colleagues (Geyer, Russo, & Masten, 1986; Paulus, Geyer, & Braff, 1996; Young et al., 2007). The BPM is a chamber with rearing touchplates on the walls and holes in the floors and walls. Locomotor movement and exploratory behavior (head dipping) is recorded via infrared beams and locomotor activity is characterized in terms of hierarchical and geometric organization. Specifically, spatial d measures the extent to which movement is one- versus two-dimensional; dynamical entropy h measures the extent to which movement is ordered versus disordered (calculated by comparing movements to preceding movement sequences); and spatial coefficient of variation (CV) measures variation in the pattern of transitions among BPM field sectors (Geyer et al., 1986; Paulus et al., 1996; Young et al., 2007). Decreased exploratory activity, rather than overall motor activity, may be associated with anxiety-related responses.

Foraging experiments consist of a nesting and foraging area. Rats are first placed in the nesting area for a habituation period, followed by exploration of the foraging area with a goal of finding and consuming food. The foraging area is manipulated by an introduction of a threatening stimulus. A range of defensive behaviors is observed, as well as nest-food foraging distance, the latency of successful food procurement, and duration of time the animal spends engaged in the feeding behavior (Choi & Kim, 2010; Fanselow & Lester, 1988; Helmstetter & Fanselow, 1993). Of particular note is the robogator paradigm by Kim and colleagues, which uses a robot “predator” as a threat stimulus to compete with the foraging drive (Choi & Kim, 2010; Mobbs & Kim, 2015).

Light-dark boxes consist of a box divided into equal compartments connected by a small opening. One compartment is painted black and enclosed, while the other is painted white, lighted, and covered in transparent glass. Rodents are placed in the illuminated box and behavior is monitored regarding latency to enter the dark compartment and frequency and duration of time spent in each compartment (Bourin & Hascoët, 2003; Kumar et al., 2013). Reduced willingness to explore the light side of the box is considered evidence of an anxiety-related response.

Interaction-based paradigms

Persistent significant fear and avoidance of social situations are the core feature of social anxiety disorder, and can also manifest themselves in generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depression. Interaction-based paradigms are designed to examine and modulate naturally occurring social behaviors in rodents. The paradigms discussed below specifically measure social avoidance behavior during situations which could be viewed as involving conflict between desire for social affiliation and the potential threat of novelty or negative interactions. This includes the social interaction test, social preference-avoidance test, social approach-avoidance test, three-chambered social approach test, and modified Y-maze (Toth & Neumann, 2013). We attempt to emphasize paradigms that focus specifically on conflict produced by drives to approach social interactions with both positive and negative potential outcomes, rather than those specifically designed to create negative social experiences resulting in helplessness or depressive-like behaviors (e.g., social defeat or social isolation paradigms) (Hollis & Kabbaj, 2014; Stepanichev, Dygalo, Grigoryan, Shishkina, & Gulyaeva, 2014; Toth & Neumann, 2013).

In the social interaction test (File, 1980; File & Hyde, 1978; File & Seth, 2003; Toth & Neumann, 2013) pairs of rats are placed in a familiar or novel test arena under high or low lighting conditions for a period of 5–15 minutes during which their exploratory and social behaviors are monitored, including sniffing, mutual grooming, adjacent lying, climbing over and crawling under the partner, approximation, and following. Social interaction is at its lowest when the area is unfamiliar and brightly lit. A decrease in social behavior is thought to indicate increased arousal or emotionality and social avoidance (File, 1980).

For the social preference-avoidance test, an experimental rodent is exposed to a non-social stimulus (e.g., wire cage) either in a familiar or novel environment for a specific period of time (i.e., 3–4 minutes) (Berton et al., 2006; Lukas et al., 2011; Toth & Neumann, 2013). After varying delays, the non-social stimulus is replaced by a conspecific for the same length of time. Social investigation of the conspecific relative to the non-social stimulus is assessed, whereby a decrease in social investigation indicates social avoidance.

Two chambers, connected by a sliding door, are used in the social approach-avoidance test (Haller & Bakos, 2002; Toth & Neumann, 2013). The larger chamber further consists of two unequal compartments, divided by a transparent perforated Plexiglas wall allowing for olfactory, visual, and auditory communication between animals. The experimental rodent is placed in the small chamber, while the conspecific is placed in the smaller compartment of the larger chamber. Following a habituation period in the non-social chamber, the sliding door is removed and the experimental rodent is allowed to explore the apparatus for a specified period of time (i.e., 5 minutes). Social avoidance is characterized by decreased frequency and duration of time spent in the social compartment compared with the non-social compartment. The three-chambered social approach test is very similar, except that the animal starts in a center compartment, with a non-social compartment on one side and a social compartment (with the conspecific) on the other side (Landauer & Balster, 1982; Toth & Neumann, 2013; Wee, Francis, Lee, Lee, & Dohanich, 1995).

The modified Y-maze (Lai, 2005; Lai & Johnston, 2002; Toth & Neumann, 2013) consists of a Y-shaped maze with closed arms. Perforated opaque Plexiglas walls are used to divide ends of each arm from the base of the maze. Prior to testing, each animal undergoes a habituation period during which it is allowed to freely explore the base and the arms of the maze for 5 minutes. The stimulus animal is then placed in one of the arms (social arm), and the experimental animal is allowed to explore the entire Y-maze for 3–5 minutes. Decreased time spent in the social relative to the non-social arm and the base suggests social avoidance.

Neural Networks

Animal research on approach-avoidance conflict implicates neural networks that overlap with those identified in the fear conditioning and extinction literature (Davis & Whalen, 2001; Kim & Jung, 2006; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Sotres-Bayon, Cain, & LeDoux, 2006). Consideration of the approach-avoidance conflict literature, however, can provide further insight into the processes supported by various regions, in turn identifying neuroanatomical targets of interest for translational work in humans. Lesion studies in animal conflict research implicate most strongly the amygdala, hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and thus are reviewed below. Other regions, including periaqueductal gray (PAG), raphe nuclei, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), mammillary bodies, and septum, most likely play important roles in conflict- and avoidance-related decisions (Lang, Davis, & Öhman, 2000; McNaughton & Corr, 2004; Millan, 2003). Striatal regions are further implicated in animal paradigms related to risk (choosing uncertain, larger risks over safer options) and social behavior, and may be under-appreciated in regard to contributions to avoidance behavior during conflict (Berton et al., 2006). For example, in a rodent Iowa Gambling Task, it was observed that rats avoiding risk (low reward/low punishment option) exhibited PFC activity initially, which moved to striatal activation after making safe preference decisions (Fitoussi et al., 2015).

Amygdala

Across animal and human studies, the amygdala has been implicated in the detection of salience within the environment and has been found to be a central region in supporting fear learning (Davis, Walker, Miles, & Grillon, 2010; Davis & Whalen, 2001; Rosen & Donley, 2006). The amygdala is not a homogenous region, but is rather composed of several distinct subregions. Most notably, the basolateral (BlA) and central amygdala (CeA) are thought to be distinctive in regards to function and neuroanatomical connections. The BlA receives input from the thalamus, cortical sensory regions, hippocampus, and PFC and is thought to function as an “evaluator,” responding to salient stimuli associated with increased arousal and vigilance (Davis et al., 2010; Rosen & Donley, 2006). The BlA projects to the CeA (along with other brain regions), which in turn is thought to be involved in orchestrating greater attention to the stimulus and appropriate responses through connections with other regions (i.e., brainstem and midbrain for behavioral and autonomic responses). The response of the CeA is thought to be modulated by afferent connections from the PFC as well as brainstem in order to allow the use of autonomic and previously learned information to inform response to current stimuli (Davis & Whalen, 2001; Rosen & Donley, 2006). The CeA also has connections to the BNST (i.e., to modulate sustained fear or anxiety responses) and striatum (i.e., to inform avoidance of stimuli associated with aversive events), and may have intriguing possibilities for conflict-related behavior (Davis et al., 2010; Davis & Whalen, 2001; Rosen & Donley, 2006).

Lesioning of the amygdala has rather consistently led to increased approach behavior (i.e., increased punished responding/reduced punishment sensitivity) on conflict tests (Choi & Kim, 2010; Kopchia, Altman, & Commissaris, 1992; Millan, 2003; Möller, Wiklund, Sommer, Thorsell, & Heilig, 1997; Yadin, Thomas, Strickland, & Grishkat, 1991), and also may increase open arm exploration on the elevated plus maze, though less consistently (Möller et al., 1997; Treit & Menard, 1997). These effects, at least for punished conflict tests, have often been circumscribed to the CeA rather than BlA (Kopchia et al., 1992; Möller et al., 1997; Yadin et al., 1991); except see (Killcross, Robbins, & Everitt, 1997). Interestingly, Jean-Richard-Dit-Bressel and McNally (2015) recently reported that inactivation of the caudal (but not rostral) BlA resulted in increased punished responding during an acquisition/learning phase (when learning to suppress responses due to punishment), but did not impact choice behavior when preferences for punished versus non-punished levers were later tested in the absence of punishment. Taken together, these findings indicate that the BlA is important for both the acquisition and expression of punishment, but not for decision-making during conflict (Jean-Richard-Dit-Bressel & McNally, 2015). Amygdala lesions have been reported to decrease social interaction, as well as aggressive displays of behavior (McHugh, Deacon, Rawlins, & Bannerman, 2004). However, prevailing theories are that, rather than reflecting an anxiolytic response, this may indicate affective blunting (punishment insensitivity), impaired recognition of social cues, or inappropriate social behavior (McHugh et al., 2004).

Hippocampus

Historically, theories of approach-avoidance conflict have highlighted the potential role of the hippocampus as central in the behavioral inhibition system and approach-avoidance conflict (Gray, 1982; Gray & McNaughton, 1996; McNaughton & Gray, 2000). The hippocampus has also been implicated in spatial navigation (more dorsal regions) and paired-associates learning, which may be relevant to exploratory and conflict paradigms, respectively (Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2014; Fanselow & Dong, 2010; Meltzer & Constable, 2005). Other theories of hippocampal function focus on its relevance for memory consolidation and representing context of fear learning (Fanselow & Dong, 2010). As with the amygdala, distinct regions of the hippocampus may underlie each of these aspects of approach/avoidance behavior.

Lesions of the ventral hippocampus have specifically been found to result in more open arm/light exploration during the elevated plus maze and light-dark boxes (Bannerman et al., 2002; Bannerman et al., 2003; Kjelstrup et al., 2002; McHugh et al., 2004; Treit & Menard, 1997; Trivedi & Coover, 2004), as well as greater social interaction (McHugh et al., 2004). The effects of dorsal hippocampal lesions have been less consistent (Bannerman et al., 2002; Kjelstrup et al., 2002; McHugh et al., 2004). Thus, while dorsal hippocampus has been more strongly implicated in spatial learning and memory, the ventral hippocampus has been implicated more strongly in the anxiety/fear response or biasing behavior during affective decisions (Bannerman et al., 2004). This functional separation seems to mimic anatomical projections, as the ventral hippocampus projects more specifically to brain regions associated with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and stress response (i.e., the PFC, BNST, and amygdala) (Bannerman et al., 2004). Recently, it was reported that ventral hippocampal lesions increased approach tendencies towards the conflict cue on a novel associative memory task in which previously-learned conflict versus neutral cues were present in different arms of a radial maze (Schumacher, Vlassov, & Ito, 2016). In this study, ventral hippocampal lesions were found not to impair conditioned cue avoidance in the absence of conflict, suggesting that the hippocampus could be important for biasing behavior away from rewarding outcomes during approach-avoidance conflict (Schumacher et al., 2016).

Medial PFC

The mPFC is prominent within current neurobiological models of fear and anxiety, with most theories focusing on its role in top-down modulation of central amygdala activity and anxiety/fear responses (Quirk & Beer, 2006; Quirk & Mueller, 2008; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2006). However, this view is predominantly informed by the fear conditioning/extinction literature, rather than other conceptual models (such as conflict), and is relatively simplistic given the complexity of anatomy, connections, and potential functions of this region (Myers-Schulz & Koenigs, 2012). The rodent mPFC can be separated into infralimbic (IL; potentially related to primate Brodmann Area [BA] 25, or the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex [sgACC], in primates) and the prelimbic (PL; potentially corresponding to primate BA 32) cortex. The IL cortex has projections to a variety of regions implicated in emotional and autonomic processing, including the amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray (PAG) and other brainstem nuclei, ventral striatum, olfactory forebrain, insula cortex, entorhinal cortex, and other cortical areas, including anterior cingulate and PL cortex (Killcross & Coutureau, 2003; Vertes, 2004). The PL cortex also projects to amygdala, thalamus, PAG and other brainstem nuclei, dorsal and ventral striatum, as well as other regions of the cortex including anterior cingulate, orbital, and infralimbic cortex (Killcross & Coutureau, 2003; Vertes, 2004).

Indication from rodent studies is that the IL cortex relates to the extinction of conditioned fear, whereas the PL cortex relates to the expression of conditioned fear (Myers-Schulz & Koenigs, 2012). This finding has often been compared to findings in human neuroimaging studies of ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) versus dorsal ACC activation. Importantly, however, there is some suggestion that BA 32 as defined in primates actually corresponds to a much more ventral region (just anterior to BA 25) in humans, which has important implications for convergence between rodent and human research (Milad et al., 2007; Myers-Schulz & Koenigs, 2012). In addition, there is also some contradictory evidence that the IL cortex serves to stimulate CeA or non-amygdalar autonomic regions to enhance stress-related responses or habitual behavior, which could point to further specialization of IL subregions (Myers-Schulz & Koenigs, 2012).

Rodent studies involving mPFC lesioning or inactivation (including both IL and PL, as well as often ACC) have reported anxiolytic effects (i.e., increased exploration) on the Vogel conflict test (Lisboa et al., 2010), elevated plus maze (Deacon, Penny, & Rawlins, 2003; Lacroix, Spinelli, Heidbreder, & Feldon, 2000; Shah & Treit, 2003; Sullivan & Gratton, 2002), open field (Lacroix et al., 2000), and social interaction tests (Gonzalez et al., 2000; Shah & Treit, 2003). Similarly, Resstel and colleagues (2008) reported that either selective PL or IL cortical lesions increased punished responding on the Vogel conflict test. Contrary to these findings, Lisboa et al., (2010) reported that mPFC lesions (both PL and IL) result in an anxiogenic effect on the elevated plus maze and light-dark box, while Jinks and McGregor (1997) found IL lesions to produce an anxiogenic effect on the elevated plus maze and open field test. Finally, Fitzpatrick, Knox, and Liberzon (2011) reported PL and IL lesions to have no effect on open field test behavior.

Differences in lesion size and specificity, rodent species, and the specific paradigms used may contribute to the mixed findings in rodent lesion studies. However, thus far, there does not seem to be a clear distinction regarding the role of IL versus PL regions in conflict or exploratory-based paradigms. These results are somewhat in contrast to results within the fear conditioning literature, in which there is a general consensus that stimulation of the PL cortex results in increased freezing, whereas stimulation of the IL cortex decreases freezing to a conditioned stimulus. These conflicts point to potential differences in the aspects of anxiety (i.e., anxiety- versus fear-based responses) tapped into by the different paradigms and encourage a more nuanced perspective on the neurobiology of anxiety.

Anxiolytic Effects

There has been an overwhelming number of neurotransmitter, hormone, and other systems implicated in behavior relevant for anxiety and the animal approach-avoidance conflict paradigms discussed above. It is beyond the scope of the current review to discuss each of these systems. Given their translational utility and known anxiolytic effects in humans, we focus here on benzodiazepines and antidepressants. There is an extensive literature assessing pharmacologic effects of anxiolytic agents on behavior across the various paradigms we have discussed (i.e., punished conflict, exploratory, and social interaction paradigms). The clinical validity of these paradigms was initially judged according to their sensitivity to anxiolytic agents, namely benzodiazepines, thus limiting their ability to generalize to other drug classes used for anxiety (e.g., antidepressants). Not surprising then is that benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam, diazepam) consistently have anxiolytic effects across paradigms (injected specifically into amygdala or systemically), including increased punished responding on conflict tests, exploration of open arms on maze tasks, exploration of light areas of light-dark boxes, and social exploration on social interaction tests (for review, see Cryan and Sweeney [2011], Millan [2003], Prut and Belzung [2003], and Treit et al. [2009]).

Punishment-induced conflict paradigms (e.g., Vogel, Geller-Seifter) have perhaps had the most consistency in regard to sensitivity across drug classes of relevance for anxiety. In addition to acute benzodiazepine administration, chronic or subchronic (but not acute) administration of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs; imipramine, amitriptyline) consistently increases punished responding (Millan, 2003; Treit et al., 2009). Chronic administration of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; e.g., phelzine, parguline), bupropion, and trazodone also produced significant increases in punished responses (Treit et al., 2009). The impact of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and 5-HT1A specific agonists, such as buspirone, has been inconsistent (Basso, Gallagher, Mikusa, & Rueter, 2011; Chaki et al., 2005; Millan, 2003; Treit et al., 2009). With respect to the elevated plus maze, SSRIs, 5-HT1A agonists, and MAOIs have inconsistent anxiolytic effects, whereas neither acute nor chronic administration of TCAs produce increased open arm exploration (Borsini, Podhorna, & Marazziti, 2002; Treit et al., 2009). For the open field test, most studies report increases in center field entries with benzodiazepines (~56% of studies) and 5-HT1A agonists (~63–73% of studies) (Prut & Belzung, 2003). SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine, paroxetine), MAOIs, and TCAs have all failed to exert anxiolytic effects in the open field test or hole board tests (Borsini et al., 2002; Treit et al., 2009). Findings related to light/dark box behavior have been similar. Anxiolytic effects have been reported for benzodiazepines and 5-HT1A agonists, but not for other antidepressant classes (Borsini et al., 2002; Treit et al., 2009).

In general, benzodiazepines decrease avoidance on social interaction tests (File, 1980; File & Seth, 2003; Leveleki et al., 2006; Nicolas & Prinssen, 2005), though findings have been more evident with rats than mice (Cutler, Rodgers, & Jackson, 1997; File & Seth, 2003; Hilakivi, Durcan, & Lister, 1989). SSRIs, even when administered chronically, have rather inconsistent anxiolytic effects on social interaction tests (File & Seth, 2003; Liu et al., 2010; Starr et al., 2007; To & Bagdy, 1999). Studies using 5-HT1A receptor agonists also report mixed findings, though this may be due to lower doses having a different mechanism of action (anxiolytic) as compared to higher doses (anxiogenic) (File & Seth, 2003; Gonzalez, Andrews, & File, 1996).

Several factors may account for the mixed pharmacologic effects on anxiety-relevant behavior. One possibility is that the different tests may tap into different aspects of anxiety (Cryan & Holmes, 2005; Kalueff et al., 2007; Ramos, 2008). For example, avoidance of plus maze open arms may be guided by different neural systems than avoidance of shock during Vogel conflict. Human translational paradigms could be useful for informing such a prospect and for identifying tests relevant for different clusters of symptoms (e.g., anxiety in novel situations versus when faced with decisions between explicit positive and negative outcomes). Given different effects found across species or animal strains, it is unknown which species/strain may be most relevant for which paradigms, clinical symptoms, or pharmacologic agents (Cryan & Holmes, 2005; Pawlak, Ho, & Schwarting, 2008; Rex, Voigt, Gustedt, Beckett, & Fink, 2004). Notably, there are indications that female rodents exhibit less approach behavior during conflict-related tests than males, and that pharmacologic effects may differ for females versus males (Basso et al., 2011; Carobrez & Bertoglio, 2005). Given that human anxiety disorders are more prevalent among females, the fact that the majority of animal research uses males presents a potentially crucial translational issue. It is also possible that in humans, many of our pharmacologic agents (e.g., SSRIs) exert their benefit through mechanisms other than direct influence on anxiety-specific behaviors. Tests that measure other types of behaviors (e.g., depressive responses) or methods of assessing more complex behavioral “syndromes” (e.g., patterns of behavior across multiple tests) may therefore have predictive utility for human anxiety (Kalueff et al., 2007).

Human Paradigms

Translation from animal paradigms hold great promise for informing our understanding of mental illness in humans and development of novel therapeutic approaches. However, as compared to animal research, there are few quantitative behavioral approaches to measuring approach-avoidance conflict behavior in humans. Investigators typically rely on subjective rating scales to quantify the strength of reward- and punishment-related drives. While there are many scales relevant to these constructs separately (e.g., neuroticism, extroversion), the behavioral activation/inhibition scale (BIS/BAS) was specifically developed to assess the systems proposed by Gray and colleagues (Carver & White, 1994; Gray, 1982; Gray & McNaughton, 2003). Notably, the BIS/BAS scale has been further revised to distinguish between the fight-flight-freeze system (FFFS) and the BIS, in order to account for evident neuropsychopharmacological differences between fear and anxiety processes (Corr, 2016; Corr & Cooper, 2016; Corr & McNaughton, 2012). While the BIS/BAS remains one of the most widely used measures related to approach and avoidance motivations, recently other measures have been developed to tap into similar constructs (e.g., The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality Questionnaire RST-PQ; [Corr, 2016; Corr & Cooper, 2016]). Various neuroimaging approaches (e.g., electroencephalography [EEG], functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI]) have been used to identify relationships between self-reported approach and avoidance motivations and neural activation patterns. This literature has highlighted the potential importance of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) in guiding behavior according to goal motivations, as well as a broader network involving the PFC (ACC and OFC), amygdala, and basal ganglia (Berkman & Lieberman, 2010; Spielberg et al., 2011; Spielberg et al., 2012; Spielberg, Stewart, Levin, Miller, & Heller, 2008). In particular, the right PFC has been associated with trait avoidance motivations (Spielberg et al., 2012), while ventral striatal, medial OFC (Simon et al., 2010), and left PFC have been more frequently associated with trait approach motivations (Spielberg et al., 2012).

Given the surge of translational behavioral paradigms aimed at understanding approach-avoidance conflict behavior and neural substrates, below we focus on human behavioral paradigms that were specifically designed to, or closely resemble, the conflict, exploratory, and social interaction animal paradigms discussed above. While we recognize the importance of paradigms assessing automatic response tendencies (i.e., reaction times) to approach or avoid affective stimuli (e.g., modified dot probe tests, approach avoidance test [AAT]; [Cisler & Koster, 2010; Heuer, Rinck, & Becker, 2007; Rinck & Becker, 2007]) these paradigms do not tap into approach-avoidance conflict decisions per se. Please refer to related reviews in this regard (e.g., Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2007). However, it is interesting to note that research with such tasks implicates the lateral anterior PFC in overriding automatic responses to emotionally laden stimuli (Tyborowska, Volman, Smeekens, Toni, & Roelofs, 2016; Volman, Roelofs, Koch, Verhagen, & Toni, 2011; Volman et al., 2013). Other translational paradigms, although not directly tapping into approach-avoidance conflict, are relevant for our understanding of conflict and anxious avoidance and lend themselves well to multiple methodological approaches. For example, in the human joystick-operated runway task (JORT; analogue to the mouse defense battery test), the participant controls the speed of a moving cursor that is trapped between two threat stimuli. This task has been used to study anxiety (elicited by threats that may require approach and thus cause goal conflict) and fear (elicited by threats that need to be avoided), including their genetic correlates and modulation by anxiolytics and antidepressants (Perkins et al., 2009; Perkins et al., 2011).

Monetary-Based Conflict Tasks

Notably, risk-based decision-making tasks usually involve a “high-risk” choice/behavior that is associated with a higher reward that it is more uncertain or could result in monetary loss. Thus, such paradigms elicit conflict between the potential high reward and the risk of either no reward or loss of reward (i.e., Iowa Gambling Task [IGT; Bechara, Damasio, & Damasio, 2000], Balloon Analogue Risk Task [BART; Lejuez et al., 2002]). A multitude of human lesion and neuroimaging studies have been conducted in conjunction with risk-based tasks (for review, see Mohr, Biele, & Heekeren [2010], Rangel, Camerer, & Montague [2008], and Vorhold [2008]), and recently, animal versions of these risk-based paradigms have been developed (de Visser et al., 2011; Jentsch, Woods, Groman, & Seu, 2010; Orsini et al., 2015; van Enkhuizen et al., 2014). This line of research highlights a network that includes the OFC/vmPFC and striatal regions (signaling value of outcomes), ACC and dmPFC (conflict and error monitoring), dlPFC (processing goal motivation, action selection), anterior insula (processing of internal bodily states), thalamus (processing affective responses or reward, or as a relay with the PFC), and amygdala regions (processing outcome uncertainty or ambiguity) (Mohr et al., 2010; Rangel et al., 2008). Studies have reported anxiety (e.g., trait anxiety, worry, social anxiety) to relate to either decreased (Maner et al., 2007) or increased risk-taking (Miu, Heilman, & Houser, 2008).

There have also been tasks recently developed to assess approach-avoidance conflict, but they are monetary-based and thus very similar to risk-based paradigms. O'Neil et al. (2015) and Bach et al. (2014) aimed to identify the potential role of the hippocampus in approach-avoidance conflict, given its putative role in animal models. The former involved a task in which face and scene images were associated with either gain or loss of points. Participants were then presented with a combination of a “gain” image and “loss” image to create a conflict in responding. The latter presented participants with a grid that they “explored” to collect monetary tokens. A virtual “predator” in the grid could catch the player and remove all tokens unless the participant escaped into the opposite corner, thus creating a conflict between going after tokens and avoiding losing tokens. Both of these studies implicated the anterior hippocampus (in addition to PFC and amygdala). Bach and colleagues (2014) additionally offered evidence that the anterior hippocampus particularly tracked level of threat and that individuals with hippocampal sclerosis are less impacted by threat (consistent with animal work described above).

Sheynin and colleagues (2014, 2016) utilized a task in which participants navigated a “spaceship” on the screen, obtaining point reward for shooting enemy ships. During “bomb” periods, their spaceship would be destroyed and they would lose a large amount of reward points unless they moved to a safe area. A warning phase created a conflict between continuing to pursue enemy ships versus retreating to the safe area. Females and those with greater self-reported behavioral inhibition exhibited greater frequency and duration of escape behavior, respectively (Sheynin et al., 2014). Computational modeling provided theoretic evidence that increased sensitivity to aversive outcomes could account for the higher frequency of escape associated with behavioral inhibition, and that a higher punishment/reward sensitivity ratio could underlie the longer duration of escape behavior demonstrated by females (Sheynin et al., 2016).

Pittig and colleagues (2014) developed a modified version of the IGT (i.e., “Spider Gambling Task”) by replacing the back of the cards with pictures of two spiders and two butterflies. There are two versions, such that in one spiders were depicted on the disadvantageous and butterflies on the advantageous decks (non-conflict version), while in the other, picture positions were reversed (conflict version). Relative to controls, spider-fearful individuals generally avoided advantageous choices associated with spider pictures, but as the number of trials increased they exhibited a greater rate of approach to these stimuli (Pittig et al., 2014).

Foraging has also been studied in humans as a way to understand approach-avoidance conflict. Kolling and colleagues (2012) asked participants to make two types of choices with a goal of maximizing points they could earn during the task. Participants first made a foraging choice of whether to engage with a currently offered set of abstract stimuli, or altogether search for alternative options. The alternative options were associated with high, medium, or low cost, thus creating conflict. They found that while the vmPFC was involved in making decisions based on well-defined value options, the ACC encoded the average value of the foraging environment and the cost of foraging (Kolling et al., 2012).

Affective/Pain Punishment-Induced Conflict Tasks

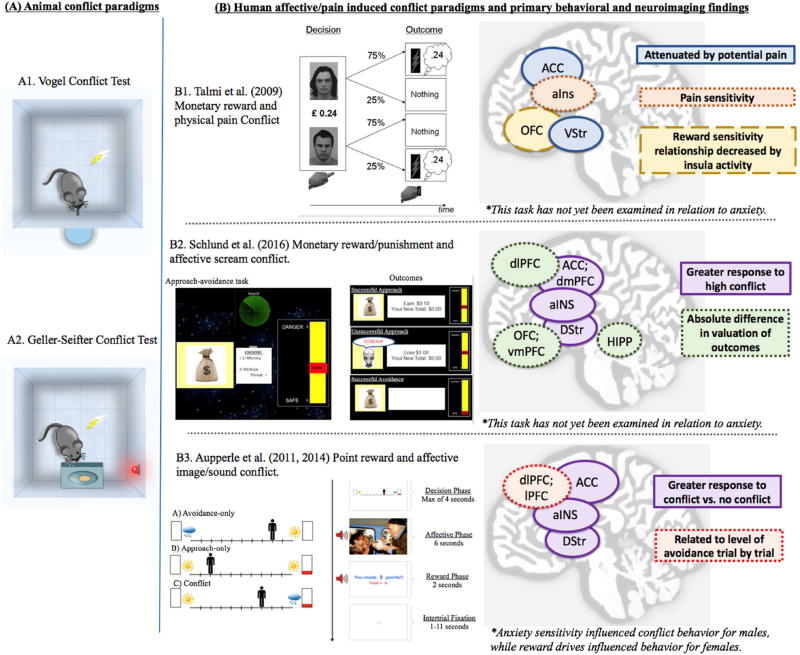

Monetary-based risk or conflict paradigms are often heavily focused on approach processing, as the “punishment” involves losing reward (e.g., money or points). These tasks may not tap directly into the constructs measured via animal approach-avoidance conflict paradigms, where the “punishment” (i.e. shock) is more directly threatening. They may also not appropriately model the affective risk or punishment (i.e., emotional triggers) that is often motivation for avoidance in anxiety disorders (but see Pittig et al., 2014). Further, there is indication that different neural systems may underlie processing monetary loss (reliant more on striatal regions) versus affective/pain related outcomes such as shock (reliant more on amygdala regions) (Delgado, Jou, & Phelps, 2011). Thus, the handful of paradigms developed to specifically tap into conflict induced by affective or pain-related “punishment” are thoroughly discussed below and summarized in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Animal punishment-induced conflict paradigms and translational human approach-avoidance conflict paradigms in which the punishment is affective or painful in nature.

(A) A1 and A2 are pictorial representations of the Vogel and Geller-Seifter conflict tests, respectively. For these tests, rodents are delivered a shock after a specific number of water licks (Vogel) or level presses for food (Geller-Seifter).

(B) B1 is a figure reprinted with permission from Talmi et al. (2009). How humans integrate the prospects of pain and reward during choice. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(46). This task presented participants with choices between two faces associated with either high or low probability of tactile (shock or touch) stimulation combined with a monetary gain or loss. B2 is a figure reprinted with permission from Schlund et al. (2016). The tipping point: Value differences and parallel dorsaleventral frontal circuits gating human approacheavoidance behavior. NeuroImage, 136, p. 97. This task presented participants with a binary choice to approach or avoid a potential $.10 outcome that was paired with varying threat (probability) of losing $1.00 and hearing an aversive female scream. B3 is a task developed by one of tShe current authors (Aupperle et al., 2011) in which participants are presented with choices between two outcomes on either side of a runway and during conflict trials, one of these outcomes consists of a negative affective image/sound combined with point reward while the other outcome consists of a positive affective image/sound combined with no points.

(C) A summary of behavioral and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) findings for each human paradigm are provided.

Talmi, Dayan, Kiebel, Frith, and Dolan (2009) investigated neural responses during a learning paradigm that involved making decisions with conflicting outcomes of painful threat and reward. Pain was induced using electrode shock stimulation that was “the strongest pain they could tolerate without distress.” A comparison stimulation (“touch”) was delivered that equated to “just discernable sensation.” In each trial, participants chose between two faces associated with high (75%) or low (25%) probability of tactile delivery. For each choice, there was a monetary value offered (gain or loss) and participants were aware that the monetary outcome would only occur if the tactile stimulation was also delivered. Thus, on some trials, choosing the face associated with a higher probability of pain would result in a higher probability of monetary reward, whereas for other trials, choosing the face associated with a higher probability of pain would result in a higher probability of monetary loss. Results indicated that individuals whose choice behavior was more influenced by the potential pain stimuli exhibited (a) higher skin conductance responses and (b) greater activation in the right anterior insula during pain trials. Ventral striatal and ventral ACC activation during reward trials was significantly attenuated by the potential for pain stimulation. Level of insula activation on a trial by trial basis also seemed to relate to decreased reward sensitivity, and appeared to attenuate the relationship between the OFC and reward sensitivity. These results highlight a network of PFC-striatal-insula regions in processing of pain-reward conflict and suggest that the anterior insula may be critical in impacting choice behavior through its influence on reward-sensitive brain areas (i.e., OFC, striatum).

With the specific aim of translating animal conflict paradigms, Aupperle, Sullivan, Melrose, Paulus, and Stein (2011) developed the human approach-avoidance conflict (AAC) paradigm. The AAC includes emotional “punishment” (negative affective images combined with sound) rather than painful stimuli (as used in Talmi et al. [2009]) or monetary loss (as used in risk-based decision-making tasks) and therefore may have important implications for understanding avoidance behavior relevant specifically to anxiety disorders, which often do not involve problematic avoidance of monetary loss (with the exception of some individuals with generalized anxiety) or physically painful stimuli (with the exception of injection or other specific phobias). The AAC task presents individuals with a runway on the screen, on which there is an avatar that can be moved to the right or left. On either side of the runway are potential outcomes. For conflict conditions, one outcome involves the combination of both reward (points) and punishment (negative affective image/sound combinations), while the alternative option involves no reward and a positive affective image/sound. These trials are therefore meant to produce an approach-avoidance conflict with concurrent desires to approach the reward and avoid the negative affective outcomes.

Research using the AAC task indicates that females exhibit increased avoidance behavior compared to males (Aupperle et al., 2011; similar to Sheynin et al., 2014, 2016). Greater anxiety sensitivity (measured by the anxiety sensitivity index [ASI]) related to increased avoidance behavior during conflict for males, while greater reward drives (measured by the behavioral activation scale [BAS Fun Seeking]) related to decreased avoidance behavior for females (Aupperle et al., 2011). In a follow-up fMRI study, conflict decisions were found to elicit greater activation within bilateral anterior insula, bilateral caudate, and right-lateralized dorsal ACC and dlPFC regions (Aupperle, Melrose, Francisco, Paulus, & Stein, 2015). Right lateral PFC activation related to the level of avoidance behavior exhibited on a trial-by-trial basis. Results supported the idea that the ACC may be involved in monitoring and processing the level of emotional conflict experienced, signaling a representation of approach/avoidance drives to the lateral PFC, involved in attentional control, goal pursuit, and implementation of final motor responses (Chouinard & Paus, 2006; Hoshi, 2006; Hoshi & Tanji, 2007; Spielberg et al., 2012). Higher levels of conflict may also rely more heavily on anterior insula regions, where there is thought to be greater integration of interoceptive signals with affective valuations. In addition, the regions identified as relating to increased avoidance behavior were right lateralized—supporting propositions that right PFC regions are more involved in avoidance motivations as opposed to approach motivations (Harmon-Jones, Gable, & Peterson, 2010). The potential importance of right-lateralized dlPFC was supported by a follow-up study reporting that right dlPFC stimuliation (via transcranial direct current stimulation) increased avoidance behavior for individuals with high anxiety sensitivity (Chrysikou, Gorey, & Aupperle, 2016).

The AAC task provides a novel way of probing approach-avoidance conflict in human populations, with face validity in regard to generalizing to animal paradigms. However, it is not without limitations, including the fact that the current version varies the level of reward offered during conflict but not the level of affective threat. Therefore, although it allows for an investigation of neural substrates that underlie increased/decreased conflict due to increased salience of reward, the AAC task is not designed to examine neural substrates that may underlie increased conflict incurred by increased salience of the negative outcome.

Schlund et al. (2016) recently developed a task aimed specifically at measuring approach-avoidance conflict behavior relevant to anxiety. This task has many similarities to the task developed by Aupperle et al. (2011), but also some important differences. In this task, the threat/punishment consisted of a loss of $1.00 combined with a 600 ms female scream. The investigators created 10 levels of threat by increasing the probability of punishment delivery when that choice was made (levels 1–2 functioned as safe trials; levels 4–10 consisted of increasing probability of the punishment outcome occurring). During the task, participants are given a binary choice to “approach” or “avoid” using a button press. On the screen, they are shown the level of potential threat on one side of the screen, and a money bag on the other. If they press the button to go for the reward, they know there is a chance that they will receive the monetary loss paired with the scream, instead of the reward. Thus, while the choice/behavior is not associated with both a reward and punishment like in the AAC task and animal conflict paradigms, this method allows researchers to identify a “tipping” point at which the participant starts to avoid the potential threat. Using this paradigm, Schlund et al. (2016) identified physiological and neural signatures that tracked level of conflict (greatest match in valuation between threat and reward outcomes) versus level of threat. Specifically, greater conflict (rather than threat) was associated with (a) slower reaction time, (b) increased skin conductance, and (c) greater activation within regions of the pregenual and dorsal ACC, dmPFC, caudate head, and anterior insula/IFG. Regions of the vmPFC, OFC, dlPFC, and hippocampus showed the greatest activation during low and high conflict levels, suggesting these may have tracked absolute differences in valuation between the two outcomes.

Together, results from human affective-based conflict tasks developed by ourselves (Aupperle et al., 2011) and others (Sheynin et al. 2014, 2016) suggest that females exhibit greater avoidance behavior, replicating finding from rodent conflict paradigms (Basso et al., 2011; Carobrez & Bertoglio, 2005). In addition, results from these human paradigms suggest that, for females, approach drives rather than anxiety sensitivity or threat drives may be more important for determining avoidance behavior (Aupperle et al., 2011; Sheynin et al., 2016). This has important implications for treatment targets in anxiety disorders, as enhancing reward or approach drives (e.g., via psychological treatments such as behavioral activation or positive affect interventions) may be a more effective approach for reducing avoidance behavior than treatments focused on reducing sensitivity to anxiety or threat (e.g., via exposure-based therapies).

Neuroimaging findings of Aupperle et al. (2011) and Schlund et al. (2016) report very similar networks involved in processing conflict. Results highlight regions of the ACC, anterior insula, and caudate head in responding more to situations of high conflict, with Aupperle et al. (2011) highlighting the potential importance of lateral frontal and caudate regions in avoidance behavior. Interestingly, Aupperle et al. (2011) reported right dlPFC to activate more during conflict (as compared to non-conflict situations), whereas Schlund et al. (2016) reported left dlPFC to activate more during trials involving low conflict (i.e., either high threat or no threat). This discrepancy could be related to the lateralization of findings, as research reported above has found greater left dlPFC activation specifically to relate to approach tendencies, whereas right dlPFC activation relates to behavioral inhibition and avoidance tendencies. Schlund et al. (2016) and Talmi et al. (2009) both highlight a role for the OFC in tracking either valuation differences or in predicting greater avoidance behavior.

It is interesting to note that none of these paradigms have reported significant amygdala activation in response to approach-avoidance conflict or in relation to avoidance behavior, despite the fact that it has been highly implicated in these behaviors in animal paradigms. It is possible that the human amygdala responds equally to reward and threat outcomes (i.e., to general salience), and thus is not being identified in the contrasts involved in fMRI research. Alternatively, the amygdala may be more involved in processing outcomes, only to inform later decision-making through its connections with other regions (Aupperle et al., 2015). It is possible that in humans, conflict is mediated most strongly by other regions that have evolved to enforce more inhibitory control or integration of complex value signals (i.e., anterior insula, PFC). Finally, animal research on approach-avoidance conflict has focused primarily on vmPFC and amygdala, and has not systematically investigated the role of insula or other PFC regions that may be homologous to those identified in human research.

Notably, none of the approach-avoidance conflict paradigms discussed have been used to examine behavioral or neural responses associated with clinical anxiety populations. This would be optimal for identifying the utility of these paradigms in modeling clinical levels of avoidance, identifying neural substrates for such pathological avoidance, and translating findings from animal work in regards to the effects of pharmacologic manipulation.

Exploratory Paradigms

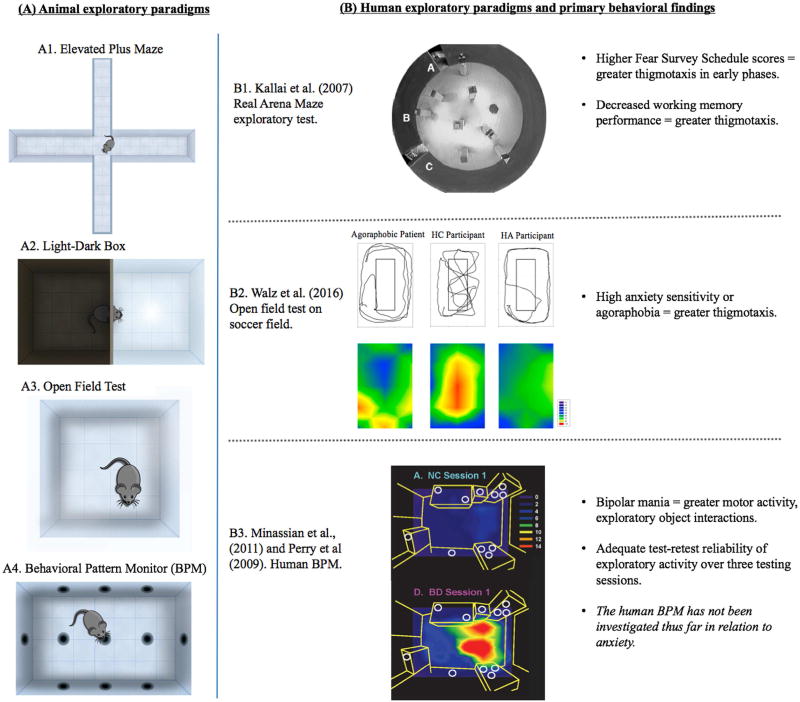

Human paradigms relevant for exploration differ from the previous conflict paradigms discussed in that they have relied more on in vivo situations in which individuals are faced with conflict between the urge to explore a novel environment (e.g., a room) and drives to avoid potential threats for doing so (e.g., social evaluation, or other unknown threats). These paradigms have been explicitly designed to mimic animal open field or activity chambers (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Animal exploratory paradigms and translational human exploratory paradigms.

(A) A1 is pictorial representation of the elevated plus maze task in which rodents are placed on a center platform of a maze with two open arms and two enclosed arms. A2 is a pictorial representation of the light-dark box in which rodents are placed into a box divided into equal black/enclosed and white/glass compartments. A3 is a pictorial representation of the open field test in which the rodent is placed in an open field area to explore. A4 is a pictorial representation of the rodent behavioral pattern monitor (a type of activity chamber) consisting of a chamber with rearing touchplates on the walls and holes in the floors and walls to invite exploration.

(B) B1 is a figure reprinted from Kallai et al. (2007). Cognitive and affective aspects of thigmotaxis strategy in humans. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121(1). Investigators used both a computer-generated circular arena (not pictured) and a real arena maze, consisting of a large circular timber wall arena with eight navigation objects placed throughout. Participants goal is to find a target platform while wearing opaque swimming glasses. B2 is a figure reprinted with permission from Walz et al. (2016). A Human Open Field Test Reveals Thigmotaxis Related to Agoraphobic Fear frontal circuits gating human approacheavoidance behavior. Biological Psychiatry, 80(5). This task consists of a 166 m × 79 m unlined soccer field that participants are asked to walk on in any way they chose for 15 minutes. B3 is a human behavioral pattern monitor developed by one of the current authors (Young et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2009) in which participants are asked to wait for 15 minutes in a room (designed to appear as an “office in transition”), with objects placed around the room to invite exploration.

Kallai et al. (2007) examined human behavior on open-field type tasks, with the aim of assessing how anxiety may relate to strategies of exploring various spaces. They utilized both a computer-generated arena and a real arena maze. The computer-generated circular arena was located within a square room, and viewed from a first-person perspective. Windows and other icons were included on the wall to assist in orientation. Participants used a joystick to navigate the space and were told the objective was to locate the target as quickly as possible (target was a blue square in first two practice trials, but invisible in the eight test trials). The real arena maze consisted of a large, circular timber wall arena (6.5 m in diameter). The investigators placed eight navigation objects (with different geometric cues, but equal in size) around the room. In one quadrant of the maze, there was a pressure-sensitive target platform disc that when stepped on, sounded a tone. Participants were asked to wear opaque swimming glasses when in the arena, preventing the use of visual information to guide exploration. The primary behavioral outcome for both the computer-generated and the real arena was thigmotaxis, calculated as the proportion of movement close to the arena wall versus the center of the room (in virtual meters or real meters, respectively). Individuals with higher total scores on the Fear Survey Schedule (but not trait anxiety) exhibited greater thigmotaxis in early phases of both the computer-generated and real arena. Decreased performance on working memory tasks also related to greater use of thigmotaxic strategies. These results provide some evidence of cross-species translation of navigational strategies in open fields, and support the idea that decreased center field entries may in fact relate to anxiety for both rodents and humans.

Walz, Mühlberger, and Pauli (2016) created a human open field test, which consisted of a 166 m × 79 m unlined soccer field surrounded by “walls” of trees and bushes. Each participant was given 15 minutes to walk on the field and then return to the starting point. A GPS sensor was attached to the participant’s arm to measure location at all times. GPS coordinates were overlayed with the soccer field separated into 15 equally sized rectangles (12 wall areas; 3 center areas), similar to rodent paradigms. Groups of participants with either high anxiety sensitivity or agoraphobia exhibited less center field entry and greater thigmotaxis during exploration of the open field, providing further support for cross-species translation of open field paradigms.

Geyer and colleagues (Minassian et al., 2011; Perry et al., 2009; Young et al., 2007) developed a human behavioral pattern monitor as an analogue to the rodent BPM. The human BPM is conducted within a 2.7 m × 4.3 m room that is unfamiliar to the participant. Within the room is a desk, filing cabinets, and bookshelves (but no chair). Dispersed evenly on the furniture are eleven objects chosen to invite exploration (safe, colorful, tactile) in order to mimic the holes in the rodent BPM. Participants are given 15 minutes to wait in the room for the experimenter and are not told that they are being observed. During this time, an ambulatory monitoring device measures physiological data and a camera in the ceiling measures the individual’s coordinate location. Manual coding is later used to assess for exploratory activity (i.e. interactions with objects). The investigators are able to calculate measures of overall motor activity, exploratory behavior, and organization of behavior (including spatial d, entropy h, and spatial CV, as in the rodent BPM). The human BPM has thus far been used to characterize behavior for patients suffering from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Specifically, hospitalized patients with either bipolar mania or schizophrenia exhibited less predictable motor activity while individuals with bipolar mania exhibited high levels of overall motor activity, more interactions with exploratory objects, and organization of activity characterized by long, straight movements (Perry et al., 2010). These results are similar to findings in the dopamine transporter genetic knock-down mice and mice administered GBR12909 (a dopamine transporter inhibitor), providing evidence for the translational validity of the paradigm. A follow-up investigation confirmed that the differences in behavior previously observed for bipolar mania were sustained across three testing sessions (across four weeks, while in inpatient treatment) and reported adequate correlations between-session for healthy controls, at least for object interactions (count of motor activity .40–.55; object interactions r = .73–.81; spatial d, r=.30 – .52; and entropy h, r = .39 – .71) (Minassian et al., 2011). These data suggest that the human BPM could be used in repeated-measures designs to characterize exploratory activity with treatments. However, even though rodent open field and activity chambers have been used extensively to assess anxiety-related behaviors and responses to anxiolytic treatment, the BPM has yet to be investigated in relation to anxiety in humans.

Social Interaction Paradigms

Human studies have typically employed passive viewing of socially relevant stimuli or the pairing of aversive unconditioned stimuli to induce social fear conditioning. While these tasks have been important for identifying automatic tendencies to “avoid” such stimuli, they do not specifically tap into decisional or social approach-avoidance conflict. Nevertheless, these studies suggest that fear responses in social anxiety are selectively sensitive to social stimuli (Lissek et al., 2008), and relate to dysfunction in the amygdala, insula, hippocampus, dACC, and vmPFC (Etkin, 2010; Pejic, Hermann, Vaitl, & Stark, 2013). There have also been tasks recently developed to assess approach and avoidance-related responses (i.e., through reaction time for joystick responses or button presses, or via eye-gaze) to emotional face stimuli (e.g., Radke, Roelofs, & de Bruijn [2013]). The most obvious translation of animal research would be to set up a large room separated into at least two “compartments,” have a confederate be present in one compartment, and assess the amount of time a participant spends in the confederate-occupied compartment during a specified time period. This type of translational work has not yet been conducted to our knowledge. However, tasks have been developed to assess social learning ability (e.g., learning an opponent’s trustworthiness [Andari et al., 2010]), social interaction in a moral context (e.g., social exclusion [Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003]), prejudice (Richeson et al., 2003), moral decision-making (Gottfried, O'Doherty, & Dolan, 2002; Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley, & Cohen, 2004; Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Heekeren, Wartenburger, Schmidt, Schwintowski, & Villringer, 2003), and social norm violation (Berthoz, Armony, Blair, & Dolan, 2002). Tasks that may have the most relevance in terms of social avoidance as measured in animal paradigms include: (1) social trust games that can assess levels of trust demonstrated behaviorally in social situations, and (2) eye gaze tasks, as focus on another’s face can be viewed as an important aspect of human social interaction.

In the “trust game,” the participant is given a certain amount of money (e.g., $10) in each trial. They are then able to decide how much of this money is to be shared with another person, and the amount shared is increased (i.e., doubled). This second player then decides how much to send back to the participant. Thus, social trust is assessed by willingness to share higher amounts with the person, trusting that they will reciprocate (Sripada et al., 2009; Tzieropoulos, 2013). Responses can also be compared for a variety of players, with different pre-determined levels of reciprocation. Thus, these paradigms may involve conflict between self- versus other-interest or the conflict between short-term costs (i.e., monetary loss) and the long-term gain of a cooperative relationship. Functional MRI studies in healthy controls have most consistently implicated the striatum and thalamus (perhaps reflecting reward processing or anticipation), amygdala and hippocampus (processing of salience, uncertainty, or risk), insula (integration of interoceptive information to inform decision-making), and cingulate cortex and other frontal cortical regions (i.e., medial, inferior, superior frontal; processing of response conflict and social mentalizing or cognitions of empathy, etc [Riedl & Javor, 2012]). Studies have not found social anxiety to relate to differences in behavioral responses on such tasks, but have reported social anxiety to relate to decreased activation within mPFC and IFG as well as greater activation in the dlPFC (Sripada et al., 2009), and decreased modulation of ventral striatal activation according to the reciprocal level of game partners (Sripada et al., 2009). These results were interpreted as reflecting dysfunction in regions important for social mentalizing or cognition and for appropriately processing social reward contingencies. However, these paradigms and findings may be only indirectly related to approach-avoidance conflict in relation to social anxiety, avoidance of social interaction, and the animal paradigms discussed above.

Eye contact is considered an important aspect of human social behavior and nonverbal social cues, which could be considered a behavioral index of relevance for approach-avoidance conflict and social anxiety (Langton, Watt, & Bruce, 2000; Vecera & Johnson, 1995). Functional MRI studies with eye gaze implicate a network involving the amygdala (processing of a motivationally relevant social cues), IFG (thought to support synchronous responses in social interactions), vmPFC (processing affective value or intent of others’ behavior), dmPFC (social mentalizing), superior temporal sulcus (processing of head orientation, body posture, and gaze information), and the ventral striatum (processing motivationally relevant cues or rewarding aspects of a social interaction) (Pfeiffer, Vogeley, & Schilbach, 2013).

Early studies investigating the relationship between social anxiety and eye contact were conducted in realistic situations (e.g., giving a speech to an audience) and manually coded. These studies reported social anxiety to relate to less gazing behavior and eye contact (Eves & Marks, 1991; Farabee, Ramsey, & Cole, 1993; Wieser, Pauli, Alpers, & Mühlberger, 2009; except see Hofmann, Gerlach, Wender, & Roth, 1997). Later studies using eye tracking devices have confirmed social anxiety to relate to decreased eye fixations to facial images (Horley, Williams, Gonsalvez, & Gordon, 2003; Horley, Williams, Gonsalvez, & Gordon, 2004; Moukheiber et al., 2010), videos (Weeks, Howell, & Goldin, 2013), and virtual reality situations (Mühlberger, Wieser, & Pauli, 2008). This literature is not without inconsistencies, however, as high social anxiety has also been reported to relate to longer eye gaze (Wieser et al., 2009; Wieser, Pauli, Grosseibl, Molzow, & Mühlberger, 2010). Wieser et al. (2010) recently used a virtual reality environment to assess not only eye gaze, but also interpersonal distance with avatars of varying sex and either direct or averted gaze at the participant. The study included women only and reported high anxiety to relate to less gaze contact and greater backward head movement in response to male avatars showing a direct gaze. Lastly, there have been studies using force plates or game boards to measure tendencies to move away from or toward emotional or facial stimuli (Eerland, Guadalupe, Franken, & Zwaan, 2012; Stins et al., 2011), which could be useful in designing future studies assessing avoidance and decision-making in social interactions.

Conclusions

There has been a recent surge of interest in the translation of paradigms from animal to human (and human to animal), in an effort to increase generalization of findings and hopefully improve or hasten development of more effective mental health interventions. Paradigms related to fear learning (conditioning and extinction) provide a model template for how such translational work can inform the field. Theoretical and clinical understanding of avoidance behavior suggests that it is a product of processes other than (or in addition to) fear-based responses or fear learning (Aupperle & Paulus, 2010; Gray & McNaughton, 2003). Sacrificing potential rewards in order to avoid anticipated potential negative outcomes appears particularly characteristic of anxious psychopathology. Thus, animal paradigms related to approach-avoidance conflict, including those involving punishment-induced conflict, exploration of novel or anxiety-provoking environments, or social interaction, may have important implications for understanding avoidance-based decision-making. Investigators have specifically put effort towards translating punishment-induced conflict (Figure 1) and exploratory (Figure 2) paradigms, though less attention has been given to translating social interaction paradigms. This lack of social interaction translation may be in part due to difficulty controlling variables involved in social interactions, such as gender and age. However, the use of virtual reality environments may support additional headway in development of both exploratory and social interaction human paradigms (e.g., Wieser et al., 2010).