Abstract

Isoprene represents a key building block for the production of valuable materials such as latex, synthetic rubber or pharmaceutical precursors and serves as basis for advanced biofuel production. To enhance the production of the volatile natural hydrocarbon isoprene, released by plants, animals and bacteria, the Kudzu isoprene synthase (kIspS) gene has been heterologously expressed in Bacillus subtilis DSM 402 and Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 using the pHT01 vector. As control, the heterologous expression of KIspS in E. coli BL21 (DE3) with the pET28b vector was used. Isoprene production was analyzed using Gas Chromatography Flame Ionization Detector. The highest isoprene production was observed by recombinant B. subtilis harboring the pHT01-kIspS plasmid which produced 1434.3 μg/L (1275 µg/L/OD) isoprene. This is threefold higher than the wild type which produced 388 μg/L (370 μg/L/OD) isoprene, when both incubated at 30 °C for 48 h and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Additionally, recombinant B. subtilis produced fivefold higher than the recombinant B. licheniformis, which produced 437.2 μg/L (249 μg/L/OD) isoprene when incubated at 37 °C for 48 h induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. This is the first report of optimized isoprene production in B. licheniformis. However, recombinant B. licheniformis showed less isoprene production. Therefore, recombinant B. subtilis is considered as a versatile host for heterologous production of isoprene.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13568-017-0461-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Isoprene, Isoprene synthase, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis

Introduction

Isoprene is a small volatile hydrophobic molecule containing five carbon atoms and is also known as 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene. It is a colorless organic compound that is produced by animals, plants and bacteria. It has a low solubility in water as well as a low boiling point of 34 °C which enables withdrawal from the upper gas phase of a bioreactor when produced via biotechnological processes (Xue and Ahring 2011). This aspect turns it valuable for downstream chemical products. Isoprene as biofuel contains more energy, is not miscible in water and does not show corrosive effects compared to ethanol (Atsumi and Liao 2008; Lindberg et al. 2010). Companies develop bioisoprene production such as Genencor and Goodyear, published their efforts to develop a gas-phase bioprocess for production of isoprene (Whited et al. 2010). Their work involved metabolic engineering of E. coli capable of producing high yields of isoprene, in addition to developing a large-scale fermentation process with high rates of the isoprene recovered from the off-gas. They reported a titer of over 60 g/L, a yield of 11% isoprene from glucose and a volumetric productivity of 2 g/L/h (Chandran et al. 2011). Several researchers reported using isoprenol as anti-knock agent, in which branched C5 alcohols store more energy than ethanol and high octane numbers (RON, or research octane number, of 92–102), that helps their use as gasoline alternatives and as anti-knock additives (Cann and Liao 2010; Mack et al. 2014). In addition, they have been verified in various engine types and they proved to have better gasoline-like properties than ethanol (Yang et al. 2010). All isoprenoids are known to be derived from the two universal five-carbon (C5) building blocks, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). These universal precursors are known to be produced by either one of the three identified pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway and/or the pathway, which is also 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) pathway. Additionally, an alternative MVA-independent pathway has been identified for the biosynthesis of IPP and DMAPP in bacteria, algae and plants which is named the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway and lacks the first two steps of the DXP pathway (Rodríguez-Concepción and Boronat 2012). Bacillus subtilis uses the DXP pathway and was found to be the best naturally isoprene producing bacteria (Kuzma et al. 1995). It is known that the isoprene synthase utilize dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) as substrate (Withers et al. 2007). The isoprene synthase gene was not identified in bacteria yet, however it has been characterized from many plants such as Populus species, e.g. aspen, Poplar Alba (Beatty et al. 2014; Fortunati et al. 2008; Miller et al. 2001; Sasaki et al. 2005; Sharkey et al. 2005; Silver and Fall 1995; Chotani et al. 2013; Vickers et al. 2010), Pueraria Montana (kudzu) and/or Pueraria lobata (Beatty et al. 2014; Hayashi et al. 2015; Sharkey et al. 2005). The isoprene synthase gene from poplar was successfully isolated and heterologously expressed in E. coli. Moreover, isoprene synthase cDNA was isolated from Populus alba (PaIspS) and expressed in E. coli for enzymatic characterization (Sasaki et al. 2005). Previous studies failed to isolate the isoprene synthase from bacteria (Julsing et al. 2007; Sivy et al. 2002), thus the Kudzu isoprene synthase gene (kIspS) was codon optimized and heterologously expressed in E. coli (Zurbriggen et al. 2012). Previously, the codon optimized Mucuna bracteata IspS was engineered in S. cerevisiae and it only produced 16.1 μg/L (Hayashi et al. 2015). Additionally, when the codon optimized M. bracteata IspS was engineered in Pantoea ananatis, it produced 63 μg/L (Hayashi et al. 2015). Recent studies involved in overexpression of codon optimized kudzu IspS (kIspS) in E. coli using different constructs (Cervin et al. 2016). The E. coli best isoprene production yield was 10 μg/L. In addition, the codon optimized kudzu and poplar IspS genes were expressed in Yarrowia lipolytica using different methods; in which the isoprene yield was 0.5–1.0 μg/L from the headspace culture (Cervin et al. 2016). This study aimed to develop recombinant Bacillus strains (B. subtilis and B. licheniformis) with high level of isoprene production using the Kudzu isoprene synthase.

Materials and methods

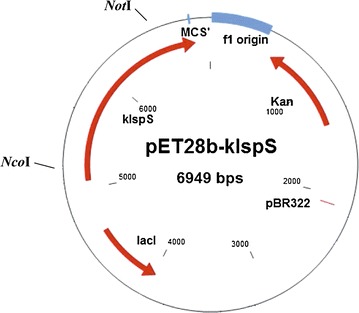

Construction of recombinant pET-28b plasmid with the kIspS for expression in E. coli

The Kudzu isoprene synthase from pBA2kIKmA2 plasmid was kindly obtained from Anastasios Melis (Addgene plasmid #39213) (Lindberg et al. 2010). The isoprene synthase gene from P. montana (kudzu) presented in GenBank under Accession No. AY316691 (Sharkey et al. 2005). The kIspS orf (1.7 kb) was amplified using the specific primers; kIspS_NcoI_F: 5′-AACACCATGGATGCCGTGGATTT-GTGCTACGAGC-3′ and kIspS_NotI_R: 5′-ATCCGCGGCCGCCACGTACATTAGTT-GATTGATTGG-3′ with added sites NcoI and NotI, respectively to facilitate the cloning process using phusion polymerase (NEB #M0530S). The amplification reaction was performed using PCR profile with an initial cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min and a final extension at 72 °C or 5 min. Thereafter, PCR product was cleaned up using DNA, RNA and protein purification REF 740609.250 Gel and PCR clean up protocol (January 2012/Rev.02). The purified fragment was digested with NcoI and NotI and ligated (using T4 DNA ligase NEB #002025) at the corresponding sites of pET-28b, forming the constructed plasmid pET28b-kIspS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Physical map of the constructed plasmid pET28b containing the kIspS gene

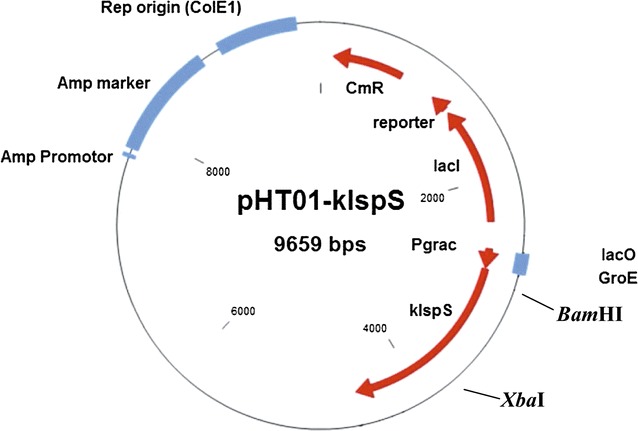

Construction of recombinant pHT01 plasmid with the kIspS for heterologous expression in Bacillus

The pHT01 plasmid (MoBiTec GmbH), which bears chloramphenicol resistance, was used for cloning and expressing the kIspS gene into two Bacillus strains; B. subtilis DSM 402 (https://www.dsmz.de/catalogues/details/culture/DSM-402.html) and Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 (https://www.dsmz.de/catalogues/details/culture/DSM-13.html). Conducted B. subtilis antibiogram showed that no natural resistance to chloramphenicol is present. To facilitate the cloning into pHT01, two primers were designed to amplify the kIspS gene harboring BamHI and XbaI cloning site; named kIspS_BamHI_F: 5′-ATATGGATCCATGCCGTGGATTTGTGCTACGAGC-3′ and kIspS_XbaI_R: 5′-ATATTCTAGACACGTACATTAGTTGATTGATTGG-3′, respectively with phusion polymerase (NEB #M0530S). The amplification reaction was performed using the same PCR profile as mentioned above and the PCR amplicon was cleaned as mentioned above. Following, the purified fragment was digested with BamHI and XbaI and ligated (using T4 DNA ligase NEB #002025) into the corresponding restriction sites of pHT01 vector, resulting in the recombinant plasmid pHT01-kIspS (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Physical map of the constructed plasmid pHT01 containing the kIspS gene

Transformation and screening of the recombinant plasmid pET28b-kIspS in E. coli BL21 (DE3)

Chemical transformation was carried out for heterologous expression of pET28b-kIspS-C-term in BL21 (DE3) (Mamiatis et al. 1985). Colony PCR strategy was performed to screen the pET28b-kIspS-C-term in BL21 (DE3) using the kIspS specific primers with the same amplification conditions as mentioned previously.

Transformation and screening of the recombinant plasmid pHT01-kIspS into B. subtilis and B. licheniformis

Preparation of electro-competent cells as well as transformation protocol was carried out according to (Xue et al. 1999) with minor modifications. In the preparation of washing and/or electroporation solution, 20% glycerol was used instead of 10% glycerol. Additionally, electroporation of the cells was performed using Micropulser electroporator BioRad catalog #165–2100 and cuvette 1 mm gap for both Bacillus strains. In the case of B. subtilis, 180 ng of plasmid DNA (pHT01-kIspS) was added to 60 µL of electro-competent cells using program EC1; voltage: 1.8 kV and time constant: 5.7 m/s as 1 pulse. In case of B. licheniformis, 290 ng of the plasmid DNA (pHT01-kIspS) was added to 60 µL of electro-competent cells. While for electroporation of cells mode: Ag, voltage: 2.2 kV and time constant 5.6 m/s as 1 pulse. For selection LB agar plates with 34 µg/mL chloramphenicol was used. In case of B. subtilis, plates were incubated on 30 °C O/N, while for B. licheniformis plates were incubated on 37 °C O/N. pHT01-kIspS plasmid mini preparation was performed (Gene JET plasmid Miniprep kit Thermo-scientific #k0503) from both Bacillus spp., in which lysozyme (20 mg/mL) was added as 5 mg/250 resuspension solution then samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with shaking for each sample. PCR was carried out for the screening of the cells harboring the recombinant the pHT01-kIspS plasmid using the same primers and amplification conditions as mentioned above.

Gas Chromatography-Flame Ionization Detector (GC-FID) analysis

Analysis of the produced isoprene was carried out using GC-FID. In this assay, an overnight grown culture was transferred to a 10 mL GC headspace vial (Macherey–Nagel, Germany) resulting in a 2 mL culture with an OD600 of 0.1. After incubation using an orbital shaker at 150 rpm, the GC vials were placed on the RSH Plus auto-sampler (Thermo Fisher) and injected onto a Trace 1310 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). The column used to detect isoprene was a Bond-U-Rt column 30 m, 0.25 mm as column ID, 8 µm df from Restek GmbH (Germany). Amounts of isoprene produced were estimated by comparison with a dilution of isoprene in ethyl acetate (Sigma-Aldrich). The response of the detector was linear at a range from 1 to 4 µM of isoprene, giving the calibration Eq. (1) with an R2 of 1.

| 1 |

Different parameters were evaluated to study the level of isoprene production, including the effect of different time intervals and IPTG induction on isoprene production.

Bacillus subtilis samples were incubated at 30 °C and in case of E. coli samples were incubated at 37 °C for 4, 8, 12, 24 and 48 h with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction. While, B. licheniformis WT and recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-KIspS samples were incubated at 37 °C for 4, 8, and 48 h upon induction with 0.1 M IPTG and without induction.

The influence of different IPTG concentrations on isoprene production

The level of isoprene production for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis harboring the recombinant plasmid pHT01-kIspS, in addition to E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring the recombinant plasmid pET28b-kIspS were investigated using different IPTG concentrations (i.e., 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 mM) for 4 h incubation at the suitable temperature for each.

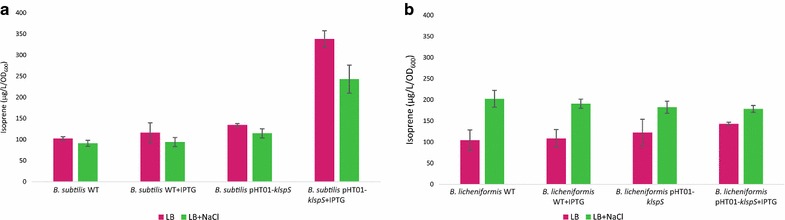

The effect of 0.3 M NaCl on B. subtilis and B. licheniformis isoprene production

Cultures of the B. subtilis and B. licheniformis were grown in Free LB and LB treated by 0.3 M NaCl with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction for 4 h incubation at the suitable temperature for each.

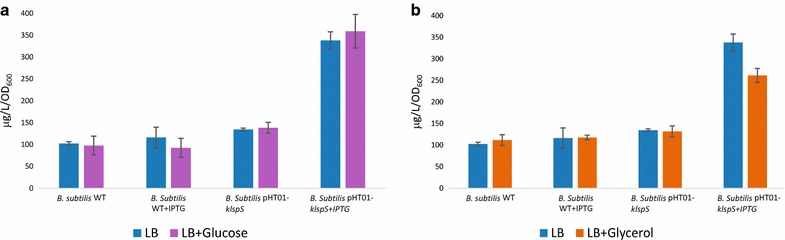

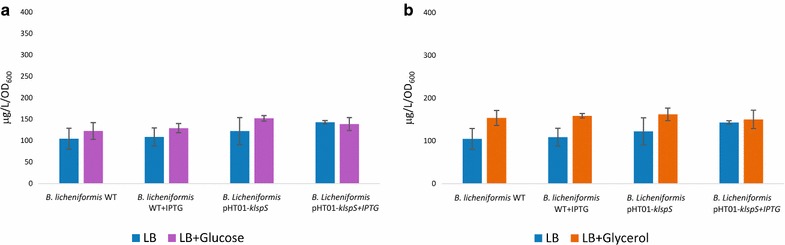

The effect of utilizing an extra carbon source on B. subtilis and B. licheniformis isoprene production

Cultures of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis were grown in Free LB and LB containing 5 g/L glucose and 5 g/L glycerol were investigated. Cultures were also grown for 4 h at the suitable temperature for each.

Codon usage analysis for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis

Codon usage analysis was performed, in which the codon usage preference table for each Bacillus spp. (B. subtilis DSM and B. licheniformis) was determined using codon usage database (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/). Then the P. montana (kudzu) isoprene synthase (kIspS) original sequence of GenBank Accession No. AY316691 was optimized using the online tool optimizer (http://genomes.urv.es/OPTIMIZER/). Comparison between the kIspS original sequence, the codon optimized kIspS sequence for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis showed that there are differences in the preferred codon and that could explain the differences in the level of kIspS in the two species.

Results

Generation of recombinant plasmid pET-28b-kIspS for heterologous expression into E. coli

The pET-28b plasmid and the amplified kIspS fragment were digested using NcoI and NotI enzymes. Agarose gel electrophoresis for the digested DNA showed the two linearized DNA strands, one at 5.2 kb which represent the expected band of the linearized pET-28 backbone and another band at 1.7 kb, which represent the kIspS gene (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The two bands were cut from the gel, cleaned up and ligated, together forming the recombinant plasmid pET28b-kIspS for heterologous expression into E. coli BL21 (DE3). Bacterial cells with and without the recombinant plasmid were used to measure isoprene production. For screening of the recombinant plasmid, colony PCR was carried out using isoprene specific primers. Positive clones showed a band at 1.7 kb (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Generation of recombinant pHT01-kIspS plasmid for heterologous expression into B. subtilis and B. licheniformis

The pHT01 plasmid and the amplified kIspS gene were digested using BamHI and XbaI restriction enzymes. Agarose gel electrophoresis of the digested DNA showed bands at 7.9 and 1.7 kb, which represent the linearized pHT01 plasmid and the kIspS gene, respectively (Additional file 3: Figure S3). The two fragments were cut from the gel, cleaned up and ligated together to form the recombinant plasmid pHT01-kIspS. Transformation was carried out for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis transformation with the recombinant plasmid pHT01-kIspS. For screening of recombinant cells, plasmid was purified and subjected to PCR analysis using the specific primers, which were mentioned above. PCR amplification of the pHT01-kIspS plasmid displayed a band at 1.7 kb; which represents the expected size of the kIspS amplicon (Additional file 4: Figure S4).

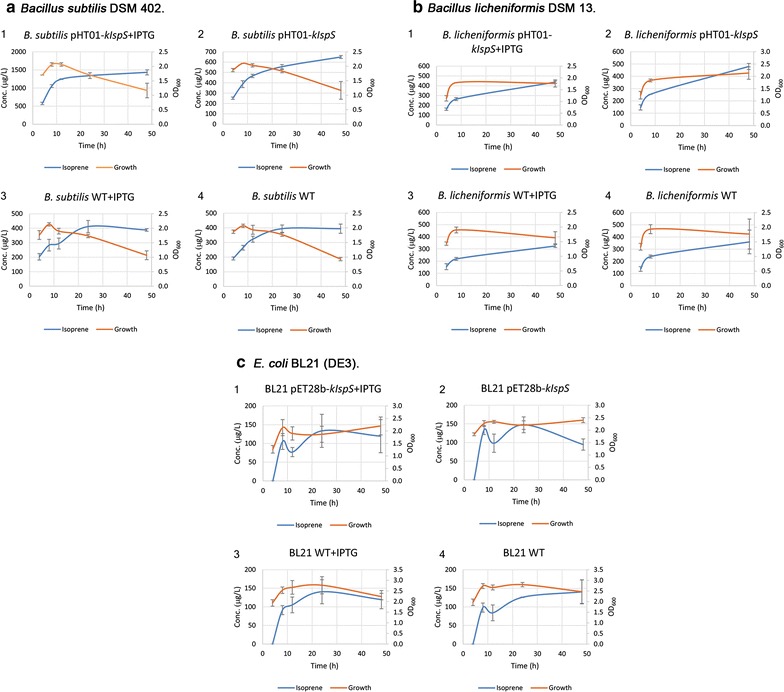

Isoprene production by different bacterial strains

The concentrations of isoprene produced from different strains were measured using GC-FID and the results indicated that the recombinant B. subtilis harboring pHT01-kIspS has the highest isoprene production of 1434.3 μg/L (1275 µg/L/OD isoprene). This is threefold higher than the wild type which produced 388 μg/L (370 μg/L/OD isoprene), when both incubated at 30 °C for 48 h and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG (Fig. 3a). While recombinant B. licheniformis, showed less isoprene production. Compared to the control (recombinant BL21 cells harboring pET28b-kIspS), which produced 53 µg/L/OD isoprene when incubated at 37 °C for 48 h and induced by 0.1 mM IPTG. Results revealed that recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-kIspS showed no significant differences in the isoprene production compared to the B. licheniformis WT during different time intervals (4, 8 and 48 h) of incubation at 37 °C and induction by 0.1 mM IPTG. Recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-kIspS produced 249 µg/L/OD when incubated at 37 °C for 48 h (Fig. 3b). The comparison between the expression of isoprene in the recombinant bacteria at 48 h incubation and 0.1 mM IPTG induction indicated that the two B. subtilis strains harboring pHT0-kIspS produced fivefold higher isoprene production than the recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT0-kIspS. To the best of our knowledge this is the first attempt of enhancing isoprene production in B. licheniformis.

Fig. 3.

Isoprene production by different strains analyzed using Gas Chromatography Flame Ionization Detector (GC-FID). Three strains were analyzed; a Bacillus subtilis DSM 402, b Bacillus licheniformis 13 and c E. coli BL21 (DE3). Four different treatments were used; (1) recombinant strain with 0.1 mM IPTG induction, (2) recombinant strain without IPTG induction, (3) WT with 0.1 mM IPTG induction, (4) WT without IPTG induction. The average concentrations (µg/L/OD600) are obtained from three independent cultures starting with the standard OD600 nm of 0.1

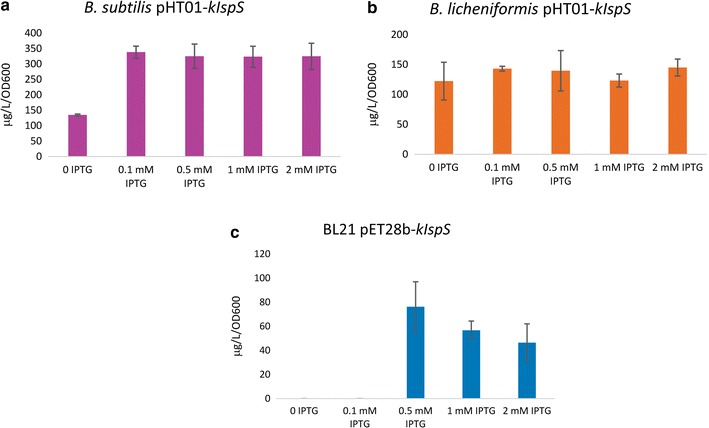

Influence of different IPTG concentrations on isoprene production

The concentrations of isoprene produced from different strains under induction with 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 mM IPTG were measured using GC-FID. Results showed insignificant difference in isoprene production of the recombinant B. subtilis harboring pHT01-kIspS upon different IPTG induction at 30 °C incubation for 4 h (Fig. 4a). While in case of recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-kIspS, results also showed insignificant differences in isoprene production by induction using different IPTG concentrations at 37 °C incubation for 4 h (Fig. 4b). Although recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET28b-kIspS showed highest isoprene production (76 µg/L/OD) at 37 °C for 4 h incubation when induced by 0.5 mM IPTG, no isoprene production was detected for the recombinant BL21 grown in LB media induced by 0.1 mM IPTG at 37 °C incubation for 4 h (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Influence of IPTG concentration on isoprene production of the different strains used in this study. The average concentrations (µg/L/OD600) were obtained from three independent cultures starting with the standard OD600 nm of 0.1. Error bars indicate standard deviation between replicate data

The effect of 0.3 M NaCl on isoprene production

Our results demonstrated that 0.3 M NaCl did not enhance the isoprene production for B. subtilis WT, recombinant B. subtilis and B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-kIspS. However, 0.3 M NaCl enhanced B. licheniformis WT isoprene production. In this respect (Xue and Ahring 2011) reported that some external factors, such as heat 48 °C, 0.3 M NaCl and H2O2 (0.005%) induce isoprene production, while 1% ethanol inhibits isoprene production. Results revealed that B. subtilis harboring pHT01-klspS produced 243 µg/L/OD, while B. subtilis WT produced only 94 µg/L/OD isoprene, when both treated with 0.3 M NaCl and 0.1 mM IPTG for 4 h incubation at 30 °C. Thus, 0.3 M NaCl did not enhance the isoprene production for the recombinant B. subtilis harboring pHT01-klspS, in which it produced 338 µg/L/OD for 4 h incubation at 30 °C without NaCl and with 0.1 mM IPTG induction (Fig. 5a). While for B. licheniformis the WT isoprene production was slightly enhanced by 0.3 M NaCl and 0.1 mM IPTG induction, as it produced 191 µg/L/OD, compared to the B. licheniformis WT that produced 108.5 µg/L/OD without 0.3 M NaCl and by 0.1 mM IPTG induction at 37 °C incubation for 4 h. Recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-klspS without 0.3 M NaCl and by 0.1 mM IPTG induction, it produced 143 µg/L/OD, while when induced by 0.3 M NaCl and 0.1 mM IPTG it produced 178.5 µg/L/OD (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

The enhancement of isoprene production in different Bacillus species a The effect of salt (0.3 M NaCl) on Bacillus subtilis isoprene production with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction in WT and pHT01-kIspS recombinant Bacillus subtilis. b The effect of salt (0.3 M NaCl) on Bacillus licheniformis isoprene production with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction in WT and pHT01-kIspS recombinant Bacillus licheniformis strain. The average isoprene production concentrations (μg per l culture per OD600) are obtained from three independent cultures starting with standard OD600 nm 0.1. The error bars represent the standard deviation

Influence of utilizing an extra carbon source on isoprene production by B. subtilis and B. licheniformis

The highest isoprene production was observed for the recombinant B. subtilis harboring pHT01-kIspS upon utilizing 5 g/L glucose as an extra carbon source, in which it produced 359 µg/L/OD isoprene (Fig. 6a). While upon utilizing 5 g/L glycerol it produced 261.4 µg/L/OD isoprene when incubated at 30 °C for 4 h and induced by 0.1 mM IPTG (Fig. 6b). In contrary results revealed that B. licheniformis WT and recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-kIspS showed insignificant difference in isoprene production upon utilizing glucose (Fig. 7a) and glycerol (Fig. 7b) as an extra carbon source.

Fig. 6.

Analysis the effect of utilizing glucose and glycerol on Bacillus subtilis of isoprene production. a The influence utilizing glucose on Bacillus subtilis isoprene production with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction in WT and pHT01-kIspS recombinant Bacillus subtilis. b The influence of utilizing glycerol on Bacillus subtilis isoprene production with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction in WT and pHT01-kIspS recombinant Bacillus subtilis. The average concentrations (μg per l culture per OD600) are obtained from three independent cultures starting with the standard OD600 nm of 0.1. The error bars represent the standard deviation

Fig. 7.

Analysis the effect of utilizing glucose and glycerol on Bacillus licheniformis of isoprene production. a The influence utilizing glucose on Bacillus licheniformis isoprene production with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction in WT and pHT01-kIspS recombinant Bacillus licheniformis. b The influence of utilizing glycerol on Bacillus licheniformis isoprene production with and without 0.1 mM IPTG induction in WT and pHT01-kIspS recombinant Bacillus licheniformis. The average concentrations (μg per l culture per OD600) are obtained from three independent cultures starting with the standard OD600 nm of 0.1. The error bars represent the standard deviation

Codon usage analysis

To clarify the reason for the difference in isoprene production in B. licheniformis and B. subtilis, bioinformatics study was carried out to predict the best codon usage for both strains using software for Codon Usage DataBase. Comparison between the kIspS and the optimized IspS sequence for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis were performed and results showed differences in the codon usage between them as shown in Additional file 5: Table S1 as shaded sequences. These differences may be the cause in the level of expression of the same gene in the different species.

Discussion

In this study, we developed recombinant Bacillus strains (B. subtilis DSM 402 and B. licheniformis DSM 13) in an attempt to enhance isoprene production using the kudzu isoprene synthase. Interestingly, B. subtilis harboring the pHT01-kIspS plasmid showed a higher production of isoprene than B. licheniformis harboring the same plasmid. Recombinant B. subtilis produced 1434.3 μg/L (1275 μg/L/OD isoprene), which is threefold higher than the wild type that produced 388 μg/L (370 μg/L/OD) isoprene, when both incubated at 30 °C for 48 h by 0.1 mM IPTG induction. Our results are in accordance with a recent study for expression of kIspS in B. subtilis, in which the isoprene production levels were increased also with threefold in comparison to the wild type, from 400 μg/L to 1.2 mg/L in batch culture (Vickers and Sabri 2015). To the best of our knowledge no previous work was done for enhancing isoprene production in B. licheniformis, where this is the first report of optimized isoprene production in B. licheniformis. Since recombinant B. subtilis harboring pHT01-kIspS produce a fivefold higher isoprene production than recombinant B. licheniformis harboring pHT01-kIspS at 48 h incubation with induction by 0.1 mM IPTG. Thus, B. licheniformis seems to be not of significant importance for further studies on isoprene production. Additionally, multiple sequence alignment results showed differences in the codon usage of kIspS optimization for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis, which might be the reason that there is difference in isoprene production for both recombinant bacteria. For isoprene production optimization in our study, on one hand we found that induction by different IPTG concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 mM) did not change the level of isoprene production in B. subtilis and B. licheniformis. Recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET28b-kIspS showed higher isoprene production (76 µg/L/OD) at 37 °C for 4 h incubation when induced by 0.5 mM IPTG. On the other hand for the effect of NaCl on isoprene production, our results demonstrated that 0.3 M NaCl did not enhance the isoprene production for all strains under study except the wild type B. licheniformis. However, it was revealed that NaCl and heat can induce isoprene production, (Xue and Ahring 2011), in which isoprene increases at temperature ranging between 25 and 45 °C then decreases until it reaches 0 at 65 °C in another study, optimum bacterial isoprene production was obtained at 45 °C (Kuzma et al. 1995). Moreover, when utilizing extra carbon sources to the media, i.e. glucose and/or glycerol, highest isoprene production was observed for the recombinant B. subtilis at 5 g/L glucose as an extra substrate. This result is in contrary to the previous observation (Zurbriggen et al. 2012) for E. coli transformed with kIspS, in which glycerol provided higher yields of isoprene compared to glucose, fructose, xylose, or LB media. In addition, isoprene production assays demonstrated that kIspS expression in E. coli best activity were obtained at 37 °C for 6 h when induced by 0.1 mM IPTG (Zurbriggen et al. 2012). Previous studies demonstrated that Synechocystis PCC6803 and E. coli are responsive strains for heterologous transformation by the IspS gene, in which they express and store the isoprene protein into their cytosol (Lindberg et al. 2010). Recent studies involved in overexpression of codon optimized kudzu IspS (kIspS) in E. coli using different constructs (Cervin et al. 2016). In This study, the E. coli best isoprene production yield was 10 μg/L. Moreover, the codon optimized kudzu and poplar IspS genes were expressed in Y. lipolytica using different methods; in which the isoprene yield was 0.5–1.0 μg/L from the headspace culture (Cervin et al. 2016). Previously, the codon optimized M. bracteata IspS was engineered in Corynebacterium glutamicum and produced 24.2 μg/L, additionally it was also engineered in Enterobacter aerogenes and produced 316 μg/L (Hayashi et al. 2015). Moreover, the kIspS was expressed in Trichoderma reesei; in which it yields 0.5 μg/L isoprene. Also, the synthetic tagged kIspS gene was introduced into Synechocystis sp. PC6803 (Lindberg et al. 2010). Results revealed that low levels of IspS protein were detected, in addition to the codon optimization that significantly enhanced protein production, in which latter strain produced 50 μg isoprene per gram dry cell weight per day, which is equivalent to 4 μg isoprene/L culture/h−1 (Hong et al. 2012). The same kIspS construct was used with a glucose-sensitive version of Synechocystis sp. PC6803; which produced isoprene that peaked at 100–130 μg/L culture (Bentley et al. 2014; Bentley and Melis 2012). Additionally, the isoprene production was slightly improved to 300 μg/L culture by introducing a heterologous MVA pathway (Bentley et al. 2014). There are previous studies on expression of more than one isoprene synthase, which shows are highly production of isoprene. In which the expression of ten isoprene synthase genes from Arachishypogaea together with the MVA pathway in E. coli resulted in the production of up to 35 mg/L/h/OD of isoprene (Beatty et al. 2014). Also, it was shown that heterologous expression of P. alba IspS and S. cerevisiae MVA pathway in E. coli, yield 532 mg/L isoprene in a fed-batch fermentation (Yang et al. 2012). Previous study on enhancing isoprene production through heterologous expression of B. subtilis DXS and DXR yield 314 mg/L isoprene, while over expression endogenous DXS and DXR in E. coli harboring P. nigra IspS gene enhanced isoprene production from 94 to 160 mg/L (Zhao et al. 2011). Additionally, by introducing RBS and nucleotide spacers provide the maximum isoprene expression in E. coli batch cultures from 0.4 mg/L isoprene of the control culture to 5 mg/L isoprene per of MEP super-operon transformants culture and up to 320 mg/L isoprene of MVA super-operon transformants culture (Zurbriggen et al. 2012). It was demonstrated that B. subtilis bears an isoprene synthase activity which utilizes the dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) as a substrate for isoprene production. Additionally, the isoprene synthase activity was optimal at pH 6.2 as well as it requires low levels of divalent ions and it was found to be separated from the chloroplast isoprene synthase (Sivy et al. 2002). Recently, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (Dxs) and 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (Dxr) were overexpressed separately in B. subtilis DSM 10 strain. Over expression of Dxs increased the yield of isoprene by 40%. While over expression of Dxr had no change on the level of isoprene production (Xue and Ahring 2011). Concerning the control we have successful results in transformation of recombinant plasmid pET28b-kIspS-C-term in BL21 cells and the highest isoprene production for the recombinant BL21 cells harboring pET28b-kIspS-C-term was 70 μg/L/OD when incubated at 37 °C for 24 h induced by 0.1 mM IPTG. Previous assays for kIspS expression in E. coli, revealed that the best isoprene production activity were obtained at 37 °C for 6 h with 0.1 mM IPTG induction (Zurbriggen et al. 2012). Moreover, heterologous expression of the codon optimized kIspS in E. coli has been carried out and results showed that there is no significant difference of kIspS gene expression in recombinant and non-recombinant E. coli (Zurbriggen et al. 2012).

It can be concluded from the obtained results that recombinant B. subtilis is a better host than B. licheniformis and E. coli for expressing isoprene and is considered as a versatile host for heterologous production of isoprene. It is recommended in the future research to give more attention for synthetic biology as well as substrate utilization pathways that would aid enzyme optimization and production improvement.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Digestion of pET28b plasmid and the amplified kIspS fragment with NcoI and NotI to 2 generate pET28b-kIspS-C-term construct. Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #3 N3200, Lane 1: pET28b digested by NcoI and NotI (5.2 kb), Lane 2: kIspS (1.7 kb) digested by NcoI 4 and NotI.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Colony PCR results of the recombinant plasmid pET28b-kIspS-C term in BL21 (DE3) cells. 7 Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #N3200, Lane 1, 2 & 3 are positive results for 8 the colony PCR of pET28b-kIspS-C terminal in BL21 (DE3) cells.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Digestion of pHT01 plasmid and the amplified kIspS fragment with BamHI and XbaI to 11 generate pHT01-kIspS construct. Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #N04695, 12 Lane 1: pHT01 (7.9 kb) digested by BamHI and XbaI, Lane 2: amplified kIspS fragment (1.7 kb) 13 digested by BamHI and XbaI.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. PCR screening results for recombinant B. subtilis and B. licheniformis harboring the 15 pHT01-kIspS plasmid. Lane 1: Negative control. Lane 2: PCR results for pHT01-kIspS in B. 16 licheniformis. Lane 3: positive control from pHT01-kIspS. Lanes 4, 5 & 6: PCR results for pHT01-17 kIspS in B. subtilis. Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #N04695.

Additional file 5: Table S1. Differences between the kIsps codon and the optimized codon for (A) B. subtilis and (B) B. 20 licheniformis. Shadows show the differences in the codon.

Authors’ contributions

LA and ML carried out the main experiments, participated in the review collection and drafted the manuscript. HZ, NA and AAA contributed in designing the work and helped in drafting the manuscript. ASA contributed on the analysis of the Gas Chromatography data and NA participated in the design of the study, supervision of the research work, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Science and Technology Development Fund for the short-term fellowship (STDF-STF) of microbial isoprene production Project No. 6672, which was awarded to Ms. Lamis Gomaa in February 2014. The authors are grateful to Prof. Dr. Volker Sieber and Dr.-Ing. Jochen Schmid for their hospitality in the lab and their contribution to the experimental design.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

We conducted experiments and data generated. All data is shown in graphs. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Consent for publication

This article does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge that this work was funded in part by STDF Project No. 6672, which was awarded to Ms. Lamis Gomaa in February 2014.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- kIspS

Kudzu isoprene synthase

- GC-FID

Gas Chromatography Flame Ionization Detector

- DXP

1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate

- DMAPP

dimethylallyl diphosphate

- IPP

isopentenyl diphosphate

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13568-017-0461-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Lamis Gomaa, Email: lamis.muhammed@gmail.com.

Michael E. Loscar, Email: michael.loscar@tum.de

Haggag S. Zein, Email: drhaggagzein@staff.cu.edu.eg

Nahed Abdel-Ghaffar, Email: nahedabdelghffar@hotmail.com.

Abdelhadi A. Abdelhadi, Email: Abdelhadi.abdallah@agr.cu.edu.eg

Ali S. Abdelaal, Email: asamy82@gmail.com

Naglaa A. Abdallah, Phone: +201223179109, Email: naglaa.abdallah@agr.cu.edu.eg

References

- Atsumi S, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering for advanced biofuels production from Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty MK, Hayes K, Hou Z, Meyer DJ, Nannapaneni K, Rife CL, Wells DH, Zastrow-hayes GM. Legume isoprene synthase for production of isoprene. US Patent. 2014;8(895):277. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley FK, Melis A. Diffusion-based process for carbon dioxide uptake and isoprene emission in gaseous/aqueous two-phase photobioreactors by photosynthetic microorganisms. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:100–109. doi: 10.1002/bit.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley FK, Zurbriggen A, Melis A. Heterologous expression of the mevalonic acid pathway in cyanobacteria enhances endogenous carbon partitioning to isoprene. Mol Plant. 2014;7:71–86. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann AF, Liao JC. Pentanol isomer synthesis in engineered microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(4):893–899. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervin MA, Chotani GK, Feher FJ, La Duca R, McAuliffe JC, Miasnikov A, Peres CM, Puhala AS, Sanford KJ, Valle F. Compositions and methods for producing isoprene. US Patent. 2016;8(709):785. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran SS, Kealey JT, Reeves CD. Microbial production of isoprenoids. Process Biochem. 2011;46(9):1703–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2011.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chotani GK, Nielsen A, Sanford KJ. Reduction of carbon dioxide emission during isoprene production by fermentation. US Patent. 2013;8(470):581. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunati A, Barta C, Brilli F, Centritto M, Zimmer I, Schnitzler JP, Loreto F. Isoprene emission is not temperature-dependent during and after severe drought-stress: a physiological and biochemical analysis. Plant J. 2008;55:687–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Harada M, Takaoka S, Fukushima Y, Yokoyama K, Nishio Y, Tajima Y, Mihara Y, Nakata K. Isoprene synthase and gene encoding the same, and method for producing isoprene monomer. US Patent. 2015;8(962):296. [Google Scholar]

- Hong SY, Zurbriggen A, Melis A. Isoprene hydrocarbons production upon heterologous transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:52–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julsing MK, Rijpkema M, Woerdenbag HJ, Quax WJ, Kayser O. Functional analysis of genes involved in the biosynthesis of isoprene in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:1377–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0953-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma J, Nemecek-Marshall M, Pollock WH, Fall R. Bacteria produce the volatile hydrocarbon isoprene. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00294190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg P, Park S, Melis A. Engineering a platform for photosynthetic isoprene production in cyanobacteria, using Synechocystis as the model organism. Metab Eng. 2010;12:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JH, Rapp VH, Broeckelmann M, Lee TS, Dibble RW. Investigation of biofuels from microorganism metabolism for use as anti-knock additives. Fuel. 2014;117:939–943. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamiatis T, Fritsch E, Sambrook J, Engel J. Molecular cloning—a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Oschinski C, Zimmer W. First isolation of an isoprene synthase gene from poplar and successful expression of the gene in Escherichia coli. Planta. 2001;213:483–487. doi: 10.1007/s004250100557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boronat A. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in prokaryotic organisms. In: Bach TJ, Rohmer M, editors. Isoprenoid synthesis in plants and microorganisms: new concepts and experimental approaches. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K, Ohara K, Yazaki K. Gene expression and characterization of isoprene synthase from Populus alba. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2514–2518. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Yeh S, Wiberley AE, Falbel TG, Gong D, Fernandez DE. Evolution of the isoprene biosynthetic pathway in kudzu. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:700–712. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver GM, Fall R. Characterization of aspen isoprene synthase, an enzyme responsible for leaf isoprene emission to the atmosphere. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13010–13016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivy LT, Shirk MC, Fall R. Isoprene synthase activity parallels fluctuations of isoprene release during growth of Bacillus subtilis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:71–75. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers CE, Sabri S. Isoprene. Biotechnol Isoprenoids. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Vickers CE, Possell M, Hewitt CN, Mullineaux PM. Genetic structure and regulation of isoprene synthase in Poplar (Populus spp.) Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73:547–558. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whited GM, Feher FJ, Benko DA, Cervin MA, Chotani GK, McAuliffe JC, LaDuca RJ, Ben-Shoshan EA, Sanford KJ. Technology update: development of a gas-phase bioprocess for isoprene-monomer production using metabolic pathway engineering. Ind Biotechnol. 2010;6:152–163. doi: 10.1089/ind.2010.6.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Withers ST, Gottlieb SS, Lieu B, Newman JD, Keasling JD. Identification of isopentenol biosynthetic genes from Bacillus subtilis by a screening method based on isoprenoid precursor toxicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6277–6283. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00861-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J, Ahring BK. Enhancing isoprene production by genetic modification of the 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2399–2405. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Gang-Ping, Johnson JS, Dalrymple BP. High osmolarity improves the electro-transformation efficiency of the gram-positive bacteria Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;34(3):183–191. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(98)00087-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Dec JE, Dronniou N, Simmons B. Characteristics of isopentanol as a fuel for HCCI engines. AE Int J Fuels Lubri. 2010;3(2010-01-2164):725–741. doi: 10.4271/2010-01-2164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhao G, Sun Y, Zheng Y, Jiang X, Liu W, Xian M. Bio-isoprene production using exogenous MVA pathway and isoprene synthase in Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol. 2012;104:642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yang J, Qin B, Li Y, Sun Y, Su S, Xian M. Biosynthesis of isoprene in Escherichia coli via methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:1915–1922. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen A, Kirst H, Melis A. Isoprene production via the mevalonic acid pathway in Escherichia coli (Bacteria) Bioenergy Res. 2012;5:814–828. doi: 10.1007/s12155-012-9192-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Digestion of pET28b plasmid and the amplified kIspS fragment with NcoI and NotI to 2 generate pET28b-kIspS-C-term construct. Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #3 N3200, Lane 1: pET28b digested by NcoI and NotI (5.2 kb), Lane 2: kIspS (1.7 kb) digested by NcoI 4 and NotI.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Colony PCR results of the recombinant plasmid pET28b-kIspS-C term in BL21 (DE3) cells. 7 Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #N3200, Lane 1, 2 & 3 are positive results for 8 the colony PCR of pET28b-kIspS-C terminal in BL21 (DE3) cells.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Digestion of pHT01 plasmid and the amplified kIspS fragment with BamHI and XbaI to 11 generate pHT01-kIspS construct. Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #N04695, 12 Lane 1: pHT01 (7.9 kb) digested by BamHI and XbaI, Lane 2: amplified kIspS fragment (1.7 kb) 13 digested by BamHI and XbaI.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. PCR screening results for recombinant B. subtilis and B. licheniformis harboring the 15 pHT01-kIspS plasmid. Lane 1: Negative control. Lane 2: PCR results for pHT01-kIspS in B. 16 licheniformis. Lane 3: positive control from pHT01-kIspS. Lanes 4, 5 & 6: PCR results for pHT01-17 kIspS in B. subtilis. Marker: 2 log DNA ladder (1.0–10.0 kb) NEB catalogue #N04695.

Additional file 5: Table S1. Differences between the kIsps codon and the optimized codon for (A) B. subtilis and (B) B. 20 licheniformis. Shadows show the differences in the codon.

Data Availability Statement

We conducted experiments and data generated. All data is shown in graphs. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.