Abstract

Subunit pair 1Dx5 + 1Dy10 was recognized as superior subunit combination in wheat and contained an extra repetitive-domain cysteine residue in 1Dx5 that was important for understanding the formation of dough viscoelasticity. In this research, one specific serine codon of the 1Ax1 gene corresponding to the extra cysteine residue of 1Dx5 was substituted by a cysteine codon through site-directed mutagenesis. Four homozygous transgenic lines (T4) expressing the mutant 1Ax1 gene (mut1Ax1) were produced. Their greater dough strength and stability were confirmed by mixograph and were associated with highly increased gluten index, larger amounts of gluten macropolymers, larger size distribution for glutenin macropolymer particles and varied sodium-dodecyl-sulfate sedimentation volumes, compared with those of the one line expressing wild 1Ax1 that had similar expression level of transgene. The contents of β-sheets in dough and disulfide groups in gluten of the mut1Ax1 transgenic lines were significantly increased. The microstructure of dough mixed to peak showed a more continuous gluten matrix in the mutant transgenic lines than the one line mentioned-above. It was concluded that the extra cysteine residue of mutant 1Ax1 subunit plays a positive role in contributing to dough strength and stability of wheat by cross-linking into gluten aggregates through inter-chain disulfide bonds.

Introduction

The unique viscoelasticity of wheat dough is conferred by decisive gluten proteins in wheat grains and produces different types of wheat end-use products, such as breads, cakes, and other flour-based foods1, 2. Gluten proteins consist mainly of polymeric glutenins and monomeric gliadins, which are considered to be the major determinants of dough elasticity and viscosity, respectively3, 4. High molecular weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GSs) were highly related to the dough rheological properties5, 6, especially the high-quality subunit 1Ax1 and subunit pair 1Dx5 + 1Dy10. It was further predicated that the superiority of subunit pair 1Dx5 + 1Dy10 over other subunit pairs may be due to the role of the extra cysteine residue in the repetitive domain of subunit 1Dx5 during dough formation7–10.

The application of gene transformation methods in wheat has made it possible to compare the effects of x-type HMW-GSs on wheat flour properties. The expression of the exogenous genes 1Dx5 and 1Ax1 had different impacts on flour functional properties. Over-expression of transgene 1Dx5 dramatically increased the amount of glutenin polymers and thus resulted in “over-strong” dough properties, which were not suitable for making bread11. Meanwhile, over-expression of transgene 1Ax1 resulted in a more modest increase in dough strength12, 13. The “over-strong” characteristics of transgene 1Dx5 might result from the greater amounts of large-sized glutenin polymers due to the extra cysteine residue, which could promote the glutenin network to be more compact14, 15. However, Leόn et al.16 reported that the expression of subunit genes 1Ax1 and 1Dx5 in the bread-making wheat cv. Anza had similar effects on improving rheological properties, in which the ratios of 1Ax1/HMW and 1Dx5/HMW were 25.2% and 20.3%, respectively. The different reports about the impact of subunit 1Dx5 on dough rheological properties could be attributed to the differences in wheat genetic backgrounds and in the expression levels of the 1Dx5 gene.

Moreover, the extra cysteine in specific x-type HMW-GSs such as 1Bx7.1 may be not as important as previously reported or even interfere with glutenin polymerisation, which further has negative effect on the dough mixing properties17, 18. Thus, the effect of the extra cysteine residue of x-type HMW-GSs on the functional properties of flour remains unknown.

Therefore, further research is needed to better understand the impact of the extra cysteine residue on wheat flour processing properties. Subunits 1Ax1 and 1Dx5 have different effects on wheat flour functional properties; in most cases, the former moderately increases the flour functional property, and the latter has a detrimental effect11, 12. While subunit 1Ax1 has four cysteine residues, 1Dx5 has five, with one extra cysteine residue in the repetitive domain. Subunit 1Ax1 always appears singly due to the gene silencing of the y-type subunit at the same Glu-A1 locus in the wheat genome. In contrast, subunit 1Dx5 generally occurs with 1Dy1019, 20, and its effect might be influenced by the total amounts of both subunits, and thus the ratio of 1Dx5/1Dy10 and a balanced D-subunit composition14, 21.

In the present study, subunit 1Ax1 was selected as a mutational target to evaluate the effect of a specific extra cysteine residue close to the N-terminal repetitive domain of x-type HMW-GSs such as subunit 1Dx5 on wheat flour characteristics. The serine codon in the repetitive domain of 1Ax1 subunit that corresponds to the extra cysteine residue of subunit 1Dx5 was substituted by a cysteine codon through site-directed mutagenesis. Then, the resulting mutant gene (mut1Ax1) and wild-type 1Ax1 gene (wt1Ax1) were separately expressed in transgenic wheat lines. The impact of mutant 1Ax1 subunit (Mut1Ax1) on the flour rheological characteristics and its possible mechanism were analysed from the results of sodium-dodecyl-sulfate (SDS) sedimentation volume, gluten index analysis, mixograph, size exclusion-high performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC), glutenin macropolymer (GMP) particle size distribution, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), compared with those of the non-transformed and non-transgenic segregant lines and two positive control lines expressing wt1Ax1.

Results

Generation of transgenic plants and homozygous lines of wheat

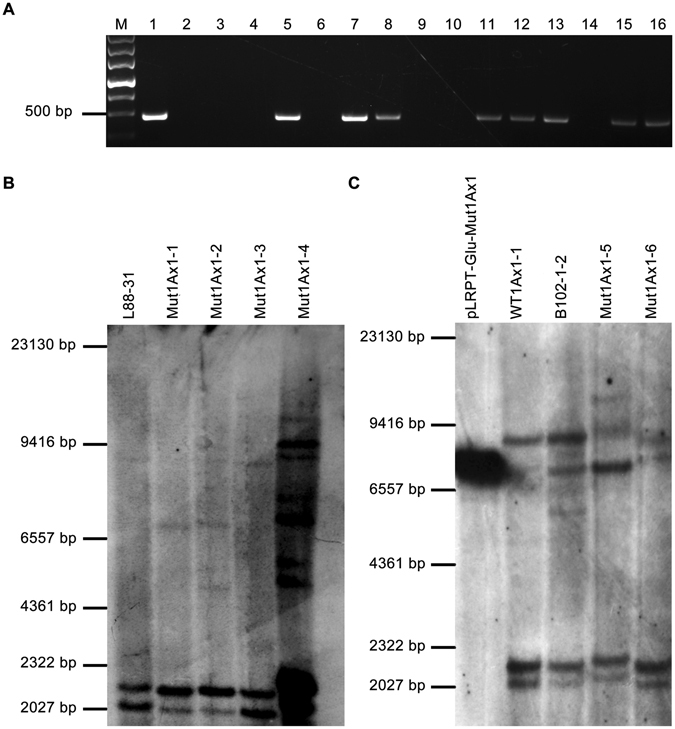

Approximately 1,000 immature wheat scutella were used for the bombardment of plasmid pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1 and in turn for tissue differentiation and plant regeneration. Positive transgenic wheat plants were confirmed in the T0 generation by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification (Fig. 1A). Meanwhile, transformed plants expressing the wt1Ax1 gene were generated as described for those expressing the mut1Ax1 gene. The sequencing results for the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) products of target gene mut1Ax1 showed that the introduced gene expressed in the transgenic wheat lines had been successfully site-mutated (Supplementary Fig. S2C and D). Subsequently, the offspring of these transgenic T0 plants were identified based on Southern blotting analysis. As shown in Fig. 1B and C, these lines had different banding patterns that may be attributed to the rearrangement and/or truncation after transgene insertion22, 23; therefore, these lines were considered independent transgenic lines.

Figure 1.

PCR (A) and Southern blotting analysis (B and C) of the transgenic wheat plants. Above: PCR amplification of the CaMV35S terminator sequence (A). Lane M: DNA Marker III; lane 1: pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1 for positive control; lane 2: water for negative control; lane 3: genomic DNA of L88-31 for negative control; lanes 4-16: genomic DNA of regenerated wheat plants. Below: Southern blotting analysis (B and C) of BamHI-cut genomic DNA from transgenic wheat lines (Mut1Ax1-1, -2, -3, -4, -5 and -6) and control lines (L88-31, WT1Ax1-1 and B102-1-2) probed with a 421 bp, DIG-labelled fragment of the pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1 coding sequence. Positive control of pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1 digested with BamHI. The PCR results of transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 in Fig. 1B and C are shown in lanes 5, 7, 8, 11, 12 and 13 of Fig. 1A, while that of line WT1Ax1-1 is shown in lane 15.

Four independent mut1Ax1 transgenic lines and one independent wt1Ax1 transgenic line were confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to be homozygous with similar levels of transgene expression in the T3 generation: Mut1Ax1-1, Mut1Ax1–2, Mut1Ax1–5, Mut1Ax1–6 and WT1Ax1-1. The expression level of transgene 1Ax1 in line B102-1-2 was the highest. The abovementioned transgenic lines, the non-transgenic segregant line N-8 and line L88-31 were considered a set of isogenic wheat lines. A field experiment with these wheat lines with a randomised complete block design was carried out for subsequent analyses24.

Agronomic performance of transgenic wheat lines

Transgenic wheat lines may have poorer agronomic characteristics with respect to their control lines25, 26. Here, as shown in Supplementary Table S1, there were no significant differences among all lines in traits such as heading date, number of spikelets per spike and 1,000-seed weight. There was no significant difference at the 0.01 probability level in growth period between transgenic and negative control lines (L88-31 and N-8) except for the positive control line B102-1-2; the number of seeds per spike was similar among lines, with the exception of transgenic line Mut1Ax1-6. The plant height of transgenic line Mut1Ax1-5 was significantly higher than that of control line N-8 (P < 0.01).

Characterisation of storage proteins

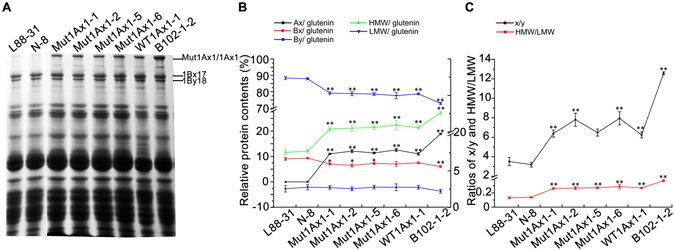

As shown in Fig. 2A, the transgenic subunit Mut1Ax1 or 1Ax1 was stably expressed in all transgenic wheat lines. Transgenic subunits accounted for 11%~13% of glutenin proteins in lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 but approximately 19% in line B102-1-2. The total protein contents of the flours varied from 7.52% for the non-transformed control line L88-31 to 9.29% for the positive control line B102-1-2; this variation indicated a clear tendency for increases in the amount of total proteins in transgenic wheat lines.

Figure 2.

Characterisations of glutenin proteins in transgenic and control lines. (A) SDS-PAGE of seed proteins extracted from transgenic and control wheat lines. Transgenic Mut1Ax1 and endogenous subunit pair 1Bx17 + 1By18 were indicated by short lines on the right side of the gel. (B) The amounts and proportions of HMW-GS and LMW-GS and the ratios of x/y and HMW/LMW were determined by densitometry analysis for all lines. Data are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). * and ** show the comparisons between all transgenic lines and negative controls (L88-31 and N-8) (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

The expression of mut1Ax1 or 1Ax1 in the transgenic wheat lines altered the amounts and compositions of glutenin proteins in the endosperm, as shown in Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 2. Relative to their negative controls L88-31 and N-8, all transgenic lines had higher contents of glutenin proteins and ratios of glutenin/gliadin. The glutenin fractions in flour increased from 3.53 μg mg−1 in line N-8 to 4.19 μg mg−1 in line B102-1-2. No significant difference in the contents of gliadin proteins was observed among lines. The glutenin/gliadin ratios in all transgenic wheat lines were higher than those in the two negative controls. Transgenic lines showed decreased contents of endogenous subunit 1Bx17 (Fig. 2B), but there was no significant difference among these lines in contents of subunit 1By18. However, all transgenic lines had higher significant increases in the ratios of x/y and HMW/LMW in glutenins (Fig. 2C).

Similar expression levels of mut1Ax1 or 1Ax1 in transgenic lines except for B102-1-2 were observed. Compared with line WT1Ax1-1, the amount of glutenin proteins was highest in lines Mut1Ax1-1 (3.82 µg mg−1 flour), Mut1Ax1-2 (4.01 µg mg−1 flour), Mut1Ax1-5 (3.69 µg mg−1 flour) and Mut1Ax1-6 (4.07 µg mg−1 flour), and those of lines Mut1Ax1-2 and Mut1Ax1-6 were significantly higher (P < 0.01). Meanwhile, contents of gliadin proteins were slightly reduced in lines Mut1Ax1-1, -2 and -5 relative to line WT1Ax1-1. Moreover, the ratio of glutenin/gliadin ranged from 0.75 in line WT1Ax1-1 to 0.87 in line Mut1Ax1-1, with no significant difference (P < 0.01). Lines expressing mut1Ax1 had slight increases in the amounts of Ax in glutenin proteins relative to line WT1Ax1-1 with no significant differences (Fig. 2B). In contrast, line WT1Ax1-1 had a higher proportion of subunit 1Bx17 in glutenins than did lines Mut1Ax1-1, -2, -5 and -6 without significant difference (P < 0.01). Based on the similar contents of 1By18 in glutenin proteins, lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 had nearly equal amounts of HMW in glutenins. Additionally, all transgenic lines generated in this study had approximately 78% of low molecular weight glutenin subunit (LMW) proteins in glutenins. Overall, there were no significant differences on the ratios of x/y and HMW/LMW in glutenins (Fig. 2C).

Except for lines Mut1Ax1-1 and -5, the contents of gutenin proteins in the other lines, Mut1Ax1-2 and -6, were similar to those in line B102-1-2 (Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the contents of gliadin proteins among lines. The ratio of glutenin/gliadin in the four mut1Ax1 transgenic lines was 0.87, 0.86, 0.8 and 0.86, respectively; these values were lower than that in B102-1-2 (0.9) with no significant difference (P < 0.01). Line B102-1-2 had the characteristic of over-expression of transgene 1Ax1 (Fig. 2B). Compared with lines expressing mut1Ax1, the amounts of both endogenous subunits 1Bx17 and 1By18 in glutenins were lower in the positive control line B102-1-2 (Fig. 2B). In addition, the proportion of LMW proteins in glutenins of line B102-1-2 was significantly reduced with respect to those mutant transgenic lines. As a result, the ratios of x/y and HMW/LMW in line B102-1-2 were evidently higher than those in lines expressing mut1Ax1 (Fig. 2C).

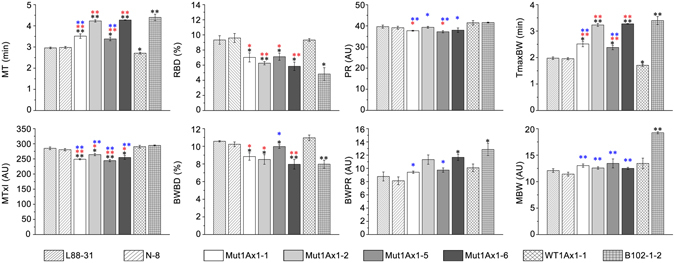

Mixing property analysis

The dough mixing properties of control and transgenic wheat lines were determined using a 10-g mixograph with three replications. As seen in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3, there were no significant differences among mixing parameters between the two negative control lines (N-8 and L88-31), which suggests that genetic transformation in the same background hardly had any effect on the dough mixing properties. All transgenic wheat lines differed from the two negative controls in the dough mixing properties, with the transgenic lines having longer mixing time (MT), higher bandwidth at peak resistance (BWPR) and maximum bandwidth during the mixing (MBW), and lower resistance to breakdown (RBD). These results indicated that the incorporation of subunit Mut1Ax1 or 1Ax1 improved the dough stability and its resistance to extension to some extent.

Figure 3.

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the dough mixing properties. Comparisons of the eight mixograph parameters among dough samples of all lines. Bars represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3). */** Show the comparisons between all transgenic lines and negative controls (L88-31 and N-8) on the mixing parameters, while  and

and  represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

With respect to line WT1Ax1-1, the transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 had significant increases in MT and time to maximum bandwidth (TmaxBW), which together with significant decreases in RBD and bandwidth breakdown (BWBD) showed greater dough strength and stability (Fig. 3). Although there was no significant difference in MBW between these lines, lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 had apparently higher values of BWPR, while the BWPR of the other two lines (Mut1Ax1-1 and -5) was similar to that of the positive control WT1Ax1-1. Dough resistance to extension was enhanced in lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6.

As mentioned above, line B102-1-2 with a higher expression level of 1Ax1 and higher ratios of x/y and HMW/LMW, differed significantly from lines expressing mut1Ax1. Line Mut1Ax1-1 had no significant difference from the control in RBD and BWBD, exclusive of the other mixing parameters, while line Mut1Ax1-5 had no significant difference in RBD and BWPR compared with line B102-1-2. Whereas both lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 had no significant differences from line B102-1-2 among those mixing parameters, except for midline integral at 8 min (MTxI) and MBW (Fig. 3).

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on gluten index and SDS-sedimentation volume

There were no significant differences in the gluten indexes or SDS-sedimentation volumes between the negative controls L88-31 and N-8 (Supplementary Table S2). Compared with the negative controls, gluten index increases were observed in all transgenic wheat lines with remarkably significant levels (P < 0.01) of Mut1Ax1-2 (59.47) and Mut1Ax1-6 (63.51) lines, significant levels (P < 0.05) of Mut1Ax1-1 (53.4) and Mut1Ax1-5 (53.7) and no significant level of WT1Ax1-1 (50.21). Compared with WT1Ax1-1, significant levels of Mut1Ax1-2 and Mut1Ax1-6 and no significant levels of Mut1Ax1-1 and Mut1Ax1-5 were observed in the transgenic lines. Line Mut1Ax1-6 was not significantly different from the control line B102-1-2 in this parameter. Meanwhile, the SDS-sedimentation volumes in all six transgenic lines were significantly higher than those of the two negative controls. The sedimentation values of all mutant transgenic lines were remarkably lower than those in line WT1Ax1-1. This result might be due to the formation of a more compact gluten matrix, which was promoted by the extra cysteine residue21, 27.

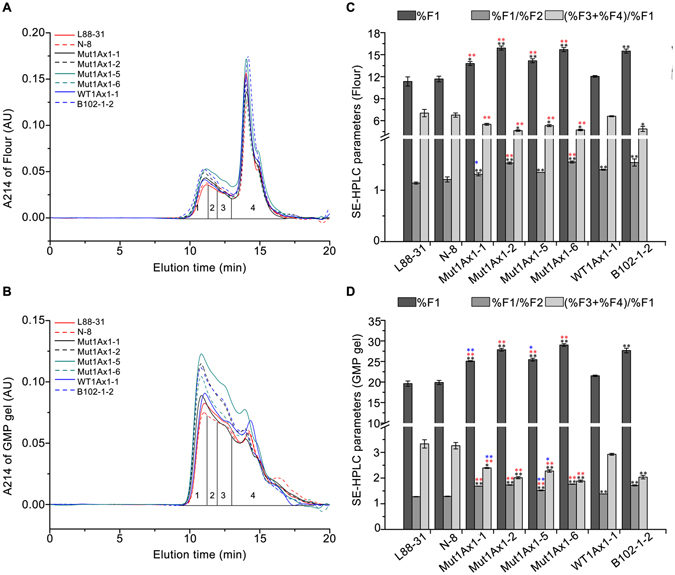

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the formation of gluten aggregates

Gluten proteins were fractionated by SE-HPLC based on molecular masses without reducing the inter-chain disulfide bonds. Figure 4 shows typical HPLC profiles of fractions extracted from flour/GMP gel samples of control and transgenic wheat lines. These parameters from SE-HPLC profiles were associated with dough strength, with which the proportion of large-sized polymers (%F1), %F1/%F2 and (%F3 + %F4)/%F1 showed particularly strong correlations28.

Figure 4.

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the formation of HMW aggregates. SE-HPLC analyses of flour and GMP gel samples of transgenic and control lines are shown in (A) and (B), with corresponding comparisons of three parameters (%F1, %F1/%F2, and (%F3 + %F4)/%F1) analysed statistically in (C) and (D). Bars represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4). */** show the comparisons between all transgenic lines and negative controls (L88-31 and N-8) on the three parameters above, while  and

and  represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

The six transgenic wheat lines had obviously higher values of %F1, lower ratios of (%F3 + %F4)/%F1 and higher ratios of %F1/%F2 compared with the negative controls L88-31 and N-8 (Fig. 4). It could be concluded that transgenic subunits incorporated the formation of gluten polymer and increased the amounts of large-sized polymers.

Notably, the peaks at fractions 1 and 2 of lines expressing mut1Ax1 were higher and accompanied by a left shift compared with those of line WT1Ax1-1 (Fig. 4A and B). In addition, the relative amount of large-sized polymers (%F1) was clearly higher in the lines expressing mut1Ax1. Moreover, the values of %F1/%F2 in lines Mut1Ax1-1, -2 and -6 significantly increased, while the (%F3 + %F4)/%F1 ratio in the four lines expressing mut1Ax1 clearly decreased in flour/GMP gel samples (Fig. 4C and D). Furthermore, the size distribution of gluten proteins in lines expressing mut1Ax1 with clearly lower transgene expression levels was similar to that of the positive control B102-1-2 with overexpression of the 1Ax1 gene (Fig. 4C). For GMP gels, there were no significant differences on the above three parameters between line B102-1-2 and the two of transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 (Mut1Ax1-2 and -6).

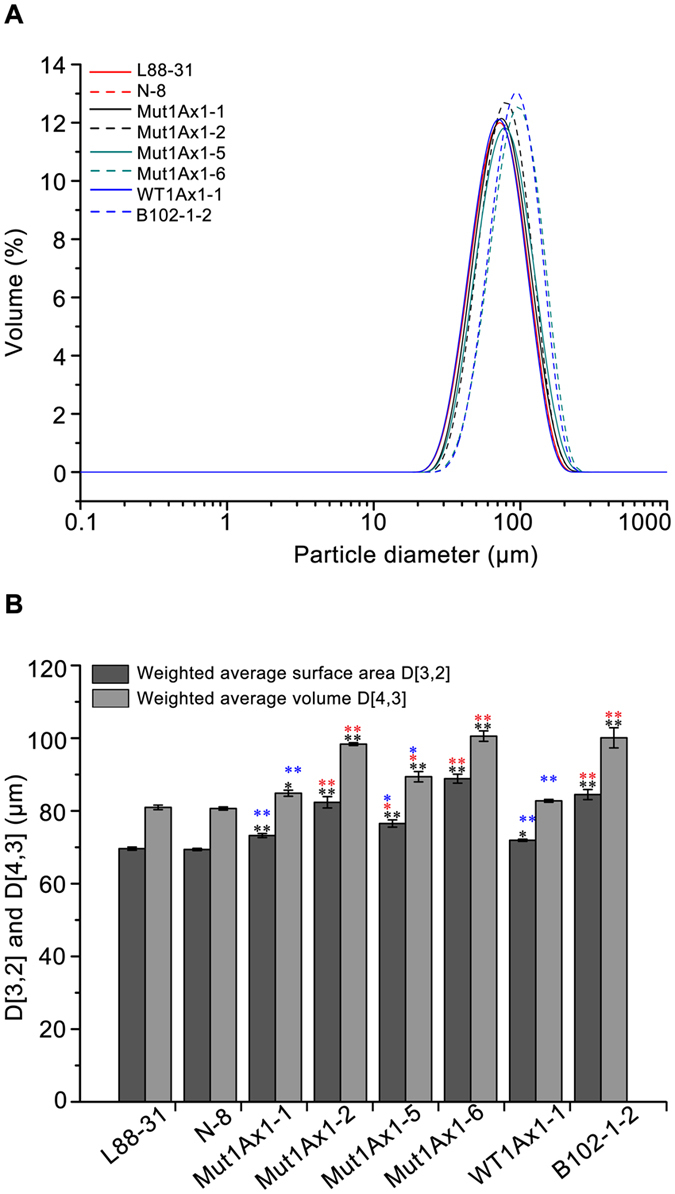

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on GMP particle size distribution

GMP was comprised of large glutenin structures and thus correlated closely with the rheological property of dough29, 30. In all transgenic wheat lines except for WT1Ax1-1, the particle diameters of GMP became larger with an obvious right shift compared with negative controls L88-31 and N-8 (Fig. 5A). This result is consistent with the results of the weighted average diameters (Fig. 5B). With respect to D[3,2] and D[4,3], lines Mut1Ax1-2, -5, and -6 increased significantly relative to line WT1Ax1-1 (P < 0.01), while line Mut1Ax1-1 had a slight increase with no significant difference. The values of D[3,2] in lines expressing mut1Ax1 were 73.23, 82.37, 76.53 and 88.87 μm respectively, while those of D[4,3] varied from 84.87 to 100.57 μm. There were no significant differences in the weighted average diameters between line B102-1-2 (84.5 μm and 100.1 μm) and lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6.

Figure 5.

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on GMP particles size distribution. (A) The size distribution patterns of GMP particles extracted from defatted flour samples. (B) Weighted average diameters D[3,2] and D[4,3] of GMP particles. Bars represent the mean ± SEM (n = 4). */** Show the comparisons between all transgenic lines and negative controls (L88-31 and N-8) on the two parameters above, while  and

and  represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

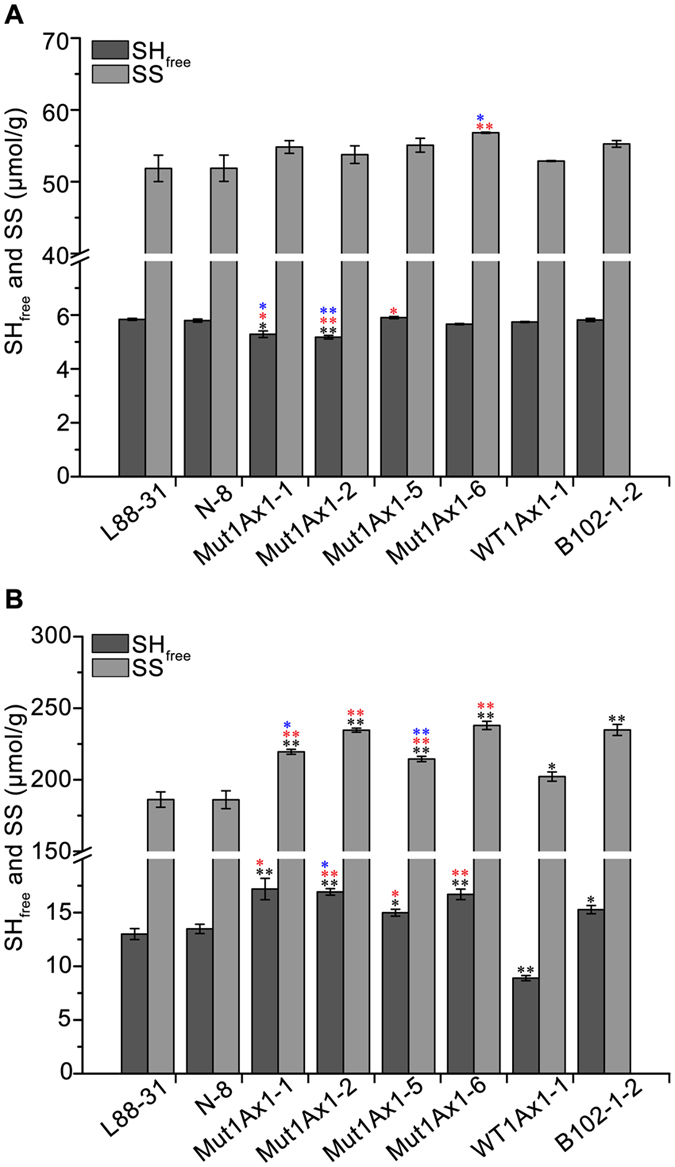

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the amount of disulfide bonds

Thiol and disulfide contents are involved in the correct folding of seed storage proteins during grain development and are thus correlated with glutenin polymer conformation. The contents of free sulfhydryl (SHfree) and disulfide (SS) in flour/ground freeze-dried gluten samples were investigated as described previously without thermomechanical treatment31. In comparisons with negative controls (L88-31 and N-8), the SS contents in flour samples were not significantly different in all transgenic lines, but the SS contents in gluten significantly increased (Fig. 6). The SS contents in flour samples of lines Mut1Ax1-1, -2, and -5 increased slightly relative to those of line WT1Ax1-1 with no significant difference. In contrast, the SS contents of line Mut1Ax1-6 were evidently higher than those of line WT1Ax1-1. In gluten samples, the contents of SHfree and SS in lines expressing mut1Ax1 were significantly higher than those of line WT1Ax1-1 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6B). Line B102-1-2 with higher expression of 1Ax1 was not significantly different from lines Mut1Ax1-1, -2 and -5 in the SS contents in flour, and it did not differ from lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 in the SS contents in gluten samples.

Figure 6.

Comparisons of free thiol and disulfide groups in flours and glutens from transgenic and control wheat lines. (A) Relative contents of free thiol and disulfide groups in flour samples from all lines. (B) Relative contents of free thiol and disulfide groups in ground freeze-dried samples from all lines. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. At least three biological experiments were performed. */** Show the comparisons between all transgenic lines and negative controls (L88-31 and N-8) on the contents of free thiol and disulfide groups, while  and

and  represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

represent comparisons between transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 and comparisons between those lines and line B102-1-2, respectively (*P

< 0.05, **P

< 0.01 by Student’s t-test).

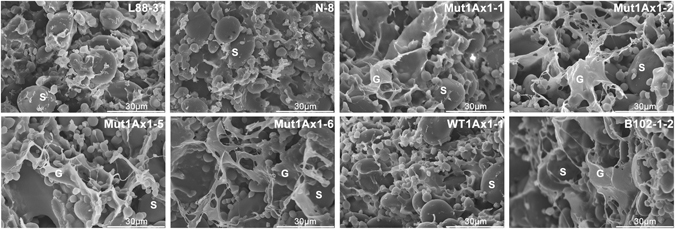

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the microstructure of dough

SEM was performed to determine the effects of the Mut1Ax1 subunit on the microstructure of wheat dough mixed to peak. Obvious distinctions from imagines are shown in Fig. 7. In the two negative lines L88-31 and N-8, the starch granules were surrounded by discrete gluten matrix. Conversely, in all transgenic wheat lines except for WT1Ax1-1, a more continuous and apparent structure was observed. Compared with the line WT1Ax1-1, the structure of the gluten network was more visible in all lines expressing mut1Ax1. At the same time, similar amounts of network matrix were observed in lines expressing mut1Ax1 and the control line B102-1-2.

Figure 7.

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the microstructure of dough mixed to peak by SEM. Displays of the starch granules (S) and the gluten network structures (G).

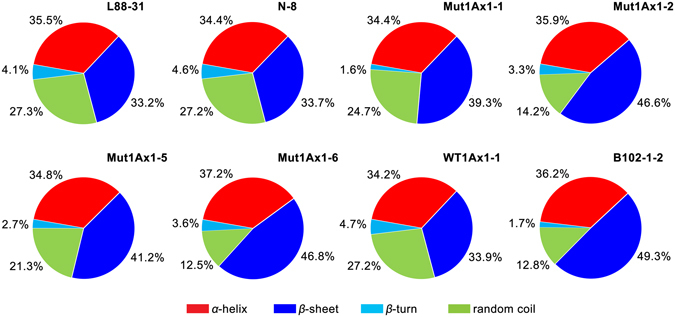

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on protein secondary structure

The curve-fitting result of dough mixed to peak is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4 to demonstrate the conformation changes of gluten proteins based on the introgression of the mut1Ax1 gene. Typical protein bands were observed over the region of 1,350-1,200 cm−1. After curve-fitting analysis, the α-helix (~1,314 cm−1) and β-sheet (~1,240 cm−1) structures occupied larger proportion of the total area (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. S4), which is similar to previously reported results32. Lines expressing mut1Ax1 had no remarkable differences in the α-helix content compared with the control line WT1Ax1-1 under similar conditions. There were significant increases in the β-sheet content of lines expressing mut1Ax1 (from 39.3% to 46.8%) relative to line WT1Ax1-1 (33.9%). Meanwhile, a striking decrease in the band at ~1,284 cm−1 was observed in dough samples of lines expressing mut1Ax1; this decrease corresponded to the random coil conformation. Moreover, the β-turn content was 1.6% in line Mut1Ax1-1, which was significantly lower than 4.7% in line WT1Ax1-1, and slightly decreased in lines Mut1Ax1-2, -5 and -6.

Figure 8.

Effects of Mut1Ax1 on the secondary structure of gluten revealed by FT-IR. Values are given as the mean percentage of each secondary structure (n = 4).

Furthermore, the α-helix content in lines expressing mut1Ax1 was not significantly different from that of the control line B102-1-2. Except for lines Mut1Ax1-1 and -5, there were no significant differences in the β-sheet and random coil contents between B102-1-2 and two transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 (Mut1Ax1-2 and -6). In contrast, a distinct difference was observed: the β-turn contents were 3.3% (Mut1Ax1-2), 2.7% (Mut1Ax1-5), and 3.6% (Mut1Ax1-6), respectively. These values were evidently higher than that of the control B102-1-2 (1.7%).

Discussion

The effects of the number and position of cysteine residues on the size of glutenin polymers and other flour functional properties have always been considered a hot research topic17, 33. The mechanism of the “over-strong” characteristics for subunit 1Dx5 with an extra cysteine residue remains unclear. Some researchers have attributed this mechanism to the presence of the extra cysteine residue in the repetitive domain14, which is due to the “head-to-tail” HMW polymer formed by disulfide crosslinking among HMW-GSs34. Some reports of subunit 1Dx5 without the extra cysteine residue have shown that the formation and stability of glutenin polymers might be due to the inter-chain hydrogen bonds presented in the conservative central repetitive domains18.

In our study, lines expressing mut1Ax1 and line WT1Ax1-1 had similar transgene expression levels, which was important for comparing the relevant experimental results. The introgressions of transgenes mut1Ax1 and wt1Ax1 (WT1Ax1-1) led to a similar effect on glutenin protein characterisation (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, more gluten aggregates were formed in GMP gels of the mutant transgenic lines due to their highly significant increases in the amounts of large- and medium-sized polymers (Fig. 4B and D). This result agrees with the results of the gluten index and size distribution of GMP particles (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 5). All lines expressing mut1Ax1 had obvious right shifts to a larger size distribution for GMP particles (Fig. 5), which helped to form a more compact gluten matrix. This change appears to be due to the extra cysteine residue forming highly cross-linked polymers relative to the control WT1Ax1-1. This residue could further lead to decreased SDS-sedimentation volumes of all mutant lines compared with the abovementioned control line27, 35–37. All mutant transgenic lines had significantly higher SDS-sedimentation volumes than those of the two negative controls (L88-31 and N-8), which was similar to the results in previous reports21, 27, 38. These data support our results of significant increases in the SS contents of gluten samples (Fig. 6). These results were further supported by the results of SEM and FT-IR analyses (Figs 7 and 8 and Supplementary Fig. S4). The more visible structure of the gluten network in dough of all mutant transgenic lines demonstrated that subunit Mut1Ax1 promoted the formation of protein network structure and thus positively impacted the dough quality. Secondary conformational changes of gluten proteins during mixing have been contributed to intermolecular interactions and are closely related to the rheological characteristics of wheat dough32. Significant increases in the β-sheet contents in these lines indicate that the amount of glutenin aggregations increased39, while relative decreases in the β-turn contents showed that intermolecular disulfide bonds were formed and promoted the conversion from β-turn to β-sheet. Compared with line WT1Ax1-1, the contents of random coils were significantly reduced in lines Mut1Ax1-2, -5 and -6 when the total β-sheet, β-turn and random coil contents were similar among the four transgenic lines. Based on the disulfide crosslinkage resulting from the extra cysteine residue, the incorporation of the Mut1Ax1 subunit might drive this transition from random coils to β-sheets and β-turns39, 40. All of the abovementioned results suggested that the extra cysteine residue in the repetitive domain was cross-linked into the formation of gluten aggregates and network matrix by intermolecular disulfide bonds. That implied that the superior dough properties of lines expressing mut1Ax1 were due to the incorporation of the Mut1Ax1 subunit, which led to longer MT, lower RBD and higher BWPR in lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 with significant differences.

The SE-HPLC results of GMP gels indicated that the size distribution of gluten proteins between the positive control line B102-1-2 and lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 was similar (Fig. 4D). Additionally, the control differed from lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 in the SS contents in gluten samples with no significant difference (Fig. 6B). GMP gels was consisted mainly of HMW-GS and LMW-GS, which were cross-linked with interchain disulfide bonds41. It was then likely that subunit Mut1Ax1 could incorporate into glutenin polymers, enhancing the formation of gluten aggregates based on the extra cysteine residue. In addition, similar scales of network structure were observed in lines expressing mut1Ax1 and control line B102-1-2 (Fig. 7). Moreover, the analysis of secondary structure further agreed with the results mentioned above. In particular, the β-sheet contents in lines Mut1Ax1-2 and -6 were not significantly different from those in the control line B102-1-2 (Fig. 8). These results helped to explain that the two transgenic lines expressing mut1Ax1 (Mut1Ax1-2 and -6) had lower transgene expression but had the roughly similar dough mixing properties as those of the control line B102-1-2 (Fig. 3). With respect to all the mutant lines, they were different from the mixing behaviours of line over-expressing 1Dx5 42, in which the peak time increased along with decreases in all other mixing characteristics. This result may be due to the difference in the expression levels of transgene mut1Ax1 and transgene 1Dx5; another possible reason is that subunit 1Dx5 originally appeared together with subunit 1Dy10.

From the abovementioned results and the fundamental mechanism regarding the formation of gluten viscoelasticity34, it was deduced here that an extra cysteine residue in subunit Mut1Ax1 took part in the cross-linking among glutenin proteins through intermolecular disulfide bonds, which increased the SS contents of gluten and glutenin macropolymers and the size of GMP particles, increased the gluten index and modified the glutenin matrix network of dough, and ultimately improved the dough strength (Figs 3–8). In addition, our study provides an applicable method for exploring the possible mechanisms behind the superiority of subunit pair 1Dx5 + 1Dy10 in comparison with pair Mut1Dx5 + 1Dy10, with subunit Mut1Dx5 without the extra cysteine residue.

Materials and Methods

Site-directed mutagenesis and vector construction

Gene mut1Ax1 was generated from a combination with one part obtained through chemical synthesis (SunBio Medical Biotechnology Ltd., Shanghai, China) and the other part cut from the plasmid pHMW1Ax1 reported by Halford et al.43.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1A, a 564 bp fragment (a) was artificially synthesised with the cytosine at the 344 bp position of gene 1Ax1 substituted by guanine, while the restriction sites BamHI and NcoI were placed on the sides of its 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The corresponding encoding domain contained site-directed mutagenesis that substituted one specific serine codon by a cysteine codon in the repetitive domain. The other linear fragment (b) of 1954 bp was gained by digesting the plasmid pHMW1Ax1 with NcoI and PstI. Then, fragments a and b were digested with NcoI; subsequent ligation made the whole gene mut1Ax1 with the restriction sites BamHI and PstI at 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. Finally, the mut1Ax1 gene was cloned into pLRPT, which was used as the eukaryotic expression vector22, 44. The construct was named pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1. The recombinant vector carrying wt1Ax1 was constructed in a similar way and named pLRPT-Glu-WT1Ax1 (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

Wheat transformation and plant regeneration

Common wheat variety L88-31 is a spring wheat with the HMW-GS pair 1Bx17 + 1By1845. Due to it being null at the Glu-A1 locus, this variety was used for particle bombardment in this study.

Genetic transformation started in May 2013. Immature scutella were isolated from young seeds of wheat cv. L88-31 as reported previously46. These young seeds were rinsed with 70% (v/v) ethanol for 5 min in a sterile conical flask, subsequently sterilised with 0.1% (v/v) HgCl2 for 5 min and rinsed with sterilised deionised water 5 times for 1 min each time. After sterilisation, these isolated scutella were bombarded with the plasmid pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1 or pLRPT-Glu-WT1Ax1 as described previously47. T0 plants regenerated via in vitro tissue culture and then grown to maturity under the same greenhouse conditions as described by Ma et al.28.

Identification of transgene integration and expression in wheat plants

To identify the transgenes in transgenic wheat plants, the primers used for PCR amplification were designed according to the sequence of the CaMV35S terminator, as its presence in the recombined construct was unique compared with the common wheat genome23. The offspring of these transgenic T0 plants were subsequently analysed by Southern blotting to confirm whether they were independent transgenic lines. Genomic DNA was extracted as previously reported48. After genomic DNA was digested with BamHI, which cuts once within the reconstruction, it was electrophoresed to fully sequence DNA fragments and transfer DNA as previously reported49. Afterwards, probe labelling, hybridisation and chemiluminescent detection were performed following the procedure of the DIG High Prime DNA Labelling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche Diagnostics Gmbh, Mannheim, Germany). Southern blotting pre-hybridisation in this study was carried out at 42 °C for 0.5 h and then hybridisation at 48 °C for 12-14 h. Primers that were used for PCR amplification to prepare the probe were designed with pLRPT-Glu-Mut1Ax1 as the DNA template and produced a 421 bp fragment for DIG labeling50.

With respect to T1 transgenic plants, developmental seeds of each line were collected at 15 days post anthesis (dpa) and were used to extract the total RNA using a Plant Total RNA kit (Zoman Bio., Beijing, China) (Supplementary Fig. S2A). After treatment with gDNase, purified mRNA was used to synthesise cDNA using the FastQuant RT Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Then, a DNA fragment containing the mutant site was amplified from the synthesised cDNA. A specific primer pair (forward primer: 5′-ATgACTAAgCggTTggTTCTT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CggAgAAgTTgggTAgTACCCTgC-3′) was designed for transgene mut1Ax1 or wt1Ax1 and used for RT-PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The transgene expression in wheat plants was also identified in single half-grains by SDS-PAGE.

Analysis of transgenic wheat lines and field trials

In the following generations, SDS-PAGE was used to screen transgenic plants expressing mut1Ax1 or wt1Ax1 in order to obtain the homozygous transgenic lines that expressed the transgene stably. To compare with the mut1Ax1 transgenic wheat lines, the wt1Ax1 transgenic wheat line obtained in this study and line B102-1-2 were used as positive controls. B102-1-2 was provided by Rothamsted Research Institute, UK, and was transformed with plasmids pHMW1Ax1 and pAHC25 in the genetic background of wheat line L88-3150. Wheat line L88-31 and non-transgenic segregant line were selected as negative controls.

A field experiment of homozygous wheat lines with a randomised complete block design with two replicates, according to Barro et al.25, was carried out in October 2015 in Wuhan, China. Plant height, spike length, number of spikelets per spike, number of seeds per spike and 1,000-seed weight were determined. Finally, seeds from all pure lines were harvested in June 2016 and then subjected to subsequent analyses.

Seed storage protein characterisation and SDS-PAGE analysis

Total seed protein was extracted from flour samples of transgenic and control wheat lines and separated by SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide gel as described by He et al.51. Glutenins from 10 mg flour samples were identified by SDS-PAGE in triplicate and were analysed using the densitometry method2. To quantify the different storage protein fractions in each line, glutenins and gliadins were extracted from whole grains as reported by Leόn et al.16. Then, the contents of glutenins and gliadins were determined according to Bradford52.

Measurement of flour protein content and dough mixing and preparation of gluten samples

Grains of two plots per line were blended together, sun-dried and tempered at a 14% (w/w) moisture level for 18 h at room temperature. Subsequently, wheat grains of each line were milled in a Chopin CD1 mill (Chopin technology co., Villeneuve-la-Garenne Cedex, France). The moisture content was determined according to International Association for Cereal Chemistry standard no.110/1 (ICC, 1976). The flour protein content was calculated from the nitrogen content by the method of Dumas according to ICC standard no.167 (%N × 5.7; ICC, 2000), using a Vario Micro cube with two replicates (Elementar co., Hanau, Germany).

A 10-g mixograph (National Manufacturing Co., Lincoln NE, USA) was used for mixograph analysis as described previously53. Mixograms and eight key mixing parameters highly related to the flour functional properties were measured and collected in triplicate. The parameters included were MT (min), TmaxBW (min), RBD (%), BWBD (%), PR (arbitrary units, AU), BWPR (AU), MBW (AU) and MTxI (AU). Dough samples mixed to peak were collected in this study and then freeze-dried for SEM analysis.

Gluten samples were obtained according to Popineau et al.42 with some modifications. Once mixing was finished as mentioned above, dough was quickly scraped off from the mixing bowl and suspended in 140 mL of distilled water by gentle magnetic stirring. After centrifugation at 5,000 g for 15 min, gluten was collected from the top layer of the mixture and then washed until no starch was left. Subsequently, the gluten was freeze-dried, ground into dry powder in a mortar, sealed and stored at 4 °C to determine the contents of free sulfhydryl and disulfide.

Determination of the gluten index and SDS-sedimentation volume

The gluten index was determined using a Glutomatic 2200 (Perten Instruments Ltd., Hägersten, Sweden) following the America Association of Cereal Chemists, approved method 38-12 A (AACC, 2000). Each sample was performed in quadruplicate. SDS-sedimentation volume test was performed according to AACC international method 56-70.01 (AACC, 1999). Four biological experiments were carried out for each sample.

Isolation of GMP gel

The gel layer was isolated from wheat flour using the method reported by Mueller et al.41. To defat, 10 g of flour was mixed with 25 mL of n-pentane, magnetically stirred for 30 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 4,235 g for 20 min at 20 °C (HC-2062, Zonkia, Hefei, China). The subsequent details of the experimental procedure followed that in the report mentioned above. The purified gel was thoroughly lyophilised, briefly ground into dry powder in a mortar, sealed and stored at 4 °C for SE-HPLC analysis.

GMP particle size distribution analysis

The particle size distribution of GMP was measured using a Mastersizer 3000 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) with a range of 0.01 ~ 3500 µm. The gel layer was isolated from 2 g of defatted flour as mentioned above. The preparation of GMP dispersions and subsequent details of measurement were carried out according to van Herpen et al.54. The particle distribution was expressed as the volume percentage. The derived data D[3,2] and D[4,3] were calculated as previously described55, which represented the weighted average surface area and the weighted average volume, respectively.

SE-HPLC analysis

Total proteins were extracted from both transgenic wheat lines and GMP gel samples of each line56. A 20 μL supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm Nylon membrane, manually injected into the Waters 1525 binary HPLC pump, and fractionated on a Phenomenex Biosep-SEC-s4000 column for 20 min (0.5 mL min−1 flow rate). It was further detected at 214 nm with a Waters 2998 photodiode array detector (Waters Corp., MA, USA). As shown in Fig. 4, each eluted profile was divided into four fractions, which corresponded to large-sized polymers (F1), medium-sized polymers (F2), small oligomers (F3) and monomeric gliadins and non-gluten proteins (F4)53.

Determination of free sulfhydryl and disulfide contents

SHfree and thiol equivalent groups (SHeq) were extracted from the flour of each line and from ground gluten samples using Ellman’s reagents [propan-2-ol, 250 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5) and 4 g/L 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid in ethanol (5/5/1, v/v/v)]31. The contents of both groups were assayed with three replicates. Tinfoil was used throughout the experiment to avoid light as much as possible. The stepwise diluted L-cysteine (1 mM) reacted with Ellman’s reagents under the same conditions as for the samples to generate a standard curve. Then, the concentration of the sample was read from its absorbance corresponding to the standard curve. All other details were consistent with the previous description57. The SS content was calculated as follows: SHeq = 2SS + SHfree. All values were expressed in μmol g−1 protein.

Scanning electron microscopy

The microstructure of dough mixed to peak was determined by a previously described method40. The freeze-dried dough samples of all lines were orderly deposited on a silicon wafer. After gold spraying, the samples were imaged on a Hitachi SEM-600 (Hitachi High-Technologies Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at 1.5 K (15 kV) magnifications.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy has been used to estimate the conformation and conformational changes of proteins58, 59. To test the changes in protein secondary structure of dough mixed to peak, a Bruker VERTEX-70 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with a universal attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory was used to record spectra in the 4,000–500 cm−1 region at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and with 64 accumulated scans32. This experiment was performed as previously described56.

Statistical analysis

Primers design and DNA sequences alignment were performed by Vector NTI Advance 11.5.1. SPSS for Windows 16.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical evaluation. Analysis of variance was performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) was used to determine significant differences in agronomic performance among lines and the contents of glutenins and gliadins. The statistical significance for other parameters was determined using Student’s t test.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Thanks should go to Zhenshu He for looking after the transgenic wheat plants carefully. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31071403, 31371614), the National Natural Science Foundation of Hubei, China (2016CFB549), and National Genetically Modified New Varieties of Major Projects of China (2016ZX08010004-004). We thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) for technical assistance in the measurements of nitrogen content and FTIR.

Author Contributions

G.H., Y.W., M.L. and F.M. conceived and wrote the paper. M.L. and Y.W. participated in all experiments and analysed the data. J.Z. and K.L. performed genetic transformation. J.C. helped to analyse storage proteins characterisation. M.C. and G.Y. performed part of the sequencing and RT-PCR experiments.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Miao Li, Yaqiong Wang and Fengyun Ma contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07541-w

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuesheng Wang, Email: wysh@hust.edu.cn.

Guangyuan He, Email: hegy@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Shewry PR. Wheat. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1537–1553. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shewry PR, et al. Comparative field performance over 3 years and two sites of transgenic wheat lines expressing HMW subunit transgenes. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;113:128–136. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shewry PR, Halford NG. Cereal seed storage proteins: structures, properties and role in grain utilization. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:947–958. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.370.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambourne J, et al. Characterisation of an s-type low molecular weight glutenin subunit of wheat and its proline and glutamine-rich repetitive domain. J Cereal Sci. 2010;51:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2009.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne PI. Genetics of wheat storage proteins and the effect of allelic variation on bread-making quality. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1987;38:141–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.38.060187.001041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gianibelli MC, Larroque OR, MacRitchie F, Wrigley CW. Biochemical, genetic and molecular characterization of wheat glutenin and its component subunits. Cereal Chem. 2001;78:635–646. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2001.78.6.635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shewry PR, et al. The high molecular weight subunits of wheat glutenin and their role in determining wheat processing properties. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2003;45:219–302. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(03)45006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence GJ, Moss HJ, Shepherd KW, Wrigley CW. Dough quality of biotypes of eleven Australian wheat cultivars that differ in high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit composition. J Cereal Sci. 1987;6:99–101. doi: 10.1016/S0733-5210(87)80045-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payne PI, Nightingale MA, Krattiger AF, Holt LM. The relationship between HMW glutenin subunit composition and the bread-making quality of British-grown wheat varieties. J Sci Food Agric. 1987;40:51–65. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740400108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shewry PR, Tatham AS, Barro F, Barcelo P, Lazzeri P. Biotechnology of bread-making: unraveling and manipulating the multi-protein gluten complex. Bio/technol. 1995;13:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/nbt1195-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooke L, et al. Overexpression of a gluten protein in transgenic wheat results in greatly increased dough strength. J Cereal Sci. 1999;30:115–120. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.1999.0265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field JM, et al. Introgression of transgenes into a commercial cultivar confirms differential effects of HMW subunits 1Ax1 and 1Dx5 on gluten properties. J Cereal Sci. 2008;48:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasil IK, et al. Evaluation of baking properties and gluten protein composition of field grown transgenic wheat lines expressing high molecular weight glutenin gene. 1Ax1. J Plant Physiol. 2001;158:521–528. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darlington H, et al. Milling and baking properties of field grown wheat expressing HMW subunit transgenes. J Cereal Sci. 2003;38:301–306. doi: 10.1016/S0733-5210(03)00034-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson OD, et al. Nucleotide sequences of the two high molecular weight glutenin genes from the D-genome of a hexaploid bread wheat, Triticum aestivum L. cv Cheyenne. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:461–462. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.1.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.León E, et al. Mixing properties and dough functionality of transgenic lines of a commercial wheat cultivar expressing the 1Ax1, 1Dx5 and 1Dy10 HMW glutenin subunit genes. J Cereal Sci. 2009;49:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2008.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao X, Zhang Q, Newberry MP, Chalmers KJ, Mather DE. A cysteine in the repetitive domain of a high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit interferes with the mixing properties of wheat dough. Amino Acids. 2013;44:1061–1071. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren Y, Wang T, Xu ZB, Yang ZJ, Ren ZL. Molecular characterization of a novel HMW-GS 1Dx5′ associated with good bread making quality (Triticum aestivum L.) and the study of its unique inheritance. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2007;55:585–592. doi: 10.1007/s10722-007-9262-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence GJ, Shepherd KW. Chromosomal location of genes controlling seed protein in species related to wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 1981;59:25–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00275771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payne PI, Lawrence GJ. Catalogue of alleles for the complex gene loci GluA1, GluB1, GluD1, which code for the high molecular-weight subunits of glutenin in hexaploid wheat. Cereal Res Commun. 1983;11:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blechl A, et al. Transgenic wheats with elevated levels of Dx5 and/or Dy10 high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits yield doughs with increased mixing strength and tolerance. J Cereal Sci. 2007;45:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2006.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He GY, et al. Expression of an extended HMW subunit in transgenic wheat and the effect on dough mixing properties. J Cereal Sci. 2005;42:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2005.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma FY, et al. Overexpression of avenin-like b proteins in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) improves dough mixing properties by their incorporation into glutenin polymers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, et al. Overexpression of Puroindoline a gene in transgenic durum wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum) leads to a medium–hard kernel texture. Mol Breed. 2013;33:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9971-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barro F, et al. Functional properties and agronomic performance of transgenic tritordeum expressing high molecular weight glutenin subunit genes 1Ax1 and 1Dx5. J Cereal Sci. 2003;37:65–70. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.2002.0479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández P, et al. Morphological and agronomic variation in transgenic tritordeum lines grown in the field. J Plant Physiol. 2000;156:223–229. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(00)80310-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barro F, et al. Functional properties of flours from field grown transgenic wheat lines expressing the HMW glutenin subunit 1Ax1 and 1Dx5 genes. Mol Breed. 2003;12:223–229. doi: 10.1023/A:1026367214120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma FY, et al. Transformation of common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) with avenin-like b gene improves flour mixing properties. Mol Breed. 2013;32:853–865. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9913-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Don C, Lichtendonk WJ, Plijter JJ, Hamer RJ. Glutenin macropolymer: a gel formed by glutenin particles. J Cereal Sci. 2003;37:1–7. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.2002.0481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Don C, Lichtendonk WJ, Plijter JJ, van Vliet T, Hamer RJ. The effect of mixing on glutenin particle properties: aggregation factors that affect gluten function in dough. J Cereal Sci. 2005;41:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2004.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morel MH, Redl A, Guilbert S. Mechanism of heat and shear mediated aggregation of wheat gluten protein upon mixing. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:488–497. doi: 10.1021/bm015639p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seabourn BW, Chung OK, Seib PA, Mathewson PR. Determination of secondary structural changes in gluten proteins during mixing using fourier transform horizontal attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy. J Agr Food Chem. 2008;56:4236–4243. doi: 10.1021/jf703569b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pirozi MR, Margiotta B, Lafiandra D, MacRitchie F. Composition of polymeric proteins and bread-making quality of wheat lines with allelic HMW-GS differing in number of cysteines. J Cereal Sci. 2008;48:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anjum FM, et al. Wheat gluten: high molecular weight glutenin subunits–structure, genetics, and relation to dough elasticity. J Food Sci. 2007;72:R56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masci S, et al. Production and characterization of a transgenic bread wheat line over-expressing a low-molecular-weight glutenin subunit gene. Mol Breed. 2003;12:209–222. doi: 10.1023/A:1026346823301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez ML, Gόmez M, Carrillo JM, Vallejos RH. Analysis of dough functionality of flours from transgenic wheat. Mol Breed. 2001;8:103–108. doi: 10.1023/A:1011995625202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakszegi M, et al. Technological quality of field grown transgenic lines of commercial wheat cultivars expressing the 1Ax1 HMW glutenin subunit gene. J Cereal Sci. 2008;47:310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez MC, Ruiz M, Carrillo JM. Effects of different prolamin alleles on durum wheat quality properties. J Cereal Sci. 2005;41:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2004.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wellner N, Bianchini D, Clare Mills EN, Belton PS. Effect of selected hofmeister anions on the secondary structure and dynamics of wheat prolamins in gluten. Cereal Chem. 2003;80:596–600. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2003.80.5.596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JJ, et al. Role of N-terminal domain of HMW 1Dx5 in the functional and structural properties of wheat dough. Food Chem. 2016;213:682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller E, Wieser H, Koehler P. Preparation and chemical characterisation of glutenin macropolymer (GMP) gel. J Cereal Sci. 2016;70:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2016.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popineau Y, et al. Prolamin aggregation, gluten viscoelasticity, and mixing properties of transgenic wheat lines expressing 1Ax and 1Dx HMW-Gs transgenes. J Agr Food Chem. 2001;49:395–401. doi: 10.1021/jf001015j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halford NG, et al. Analysis of HMW glutenin subunits encoded by chromosome 1A of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) indicates quantitative effects on grain quality. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;83:373–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00224285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tosi P, D’Ovidio R, Napier JA, Békés F, Shewry PR. Expression of epitope-tagged LMW glutenin subunits in the starchy endosperm of transgenic wheat and their incorporation into glutenin polymers. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:468–476. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawrence GJ, MacRitchie F, Wrigley CW. Dough and baking quality of wheat lines deficient in glutenin subunits controlled by the Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1 loci. J Cereal Sci. 1988;7:109–112. doi: 10.1016/S0733-5210(88)80012-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barcelo, P. & Lazzeri, P. A. In Methods in Molecular Biology: Plant gene transfer and expression protocols (ed. H. Jones) 113–123 (Humana Press, 1995).

- 47.Sparks, C. A. & Jones, H. D. In Transgenic crops of the world-essential protocols: Transformation of wheat by biolistics (ed. I. S. Curtis) 19–34 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004).

- 48.Stacey, J. & Isaac, P. G. In Methods in Molecular Biology: Protocols for nucleic acid analysis by nonradioactive probes (ed. P. G. Isaac) 9–15 (Humana Press, 1994).

- 49.Wang C, et al. Enrichment of provitamin A content in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by introduction of the bacterial carotenoid biosynthetic genes CrtB and CrtI. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:2545–2556. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barro F, et al. Transformation of wheat with high molecular weight subunit genes results in improved functional properties. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1295–1299. doi: 10.1038/nbt1197-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He GY, et al. Transformation of pasta wheat (Triticum turgidum L-var. durum) with high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit genes and modification of dough functionality. Mol Breed. 1999;5:377–386. doi: 10.1023/A:1009681321708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tosi P, et al. Modification of the low molecular weight (LMW) glutenin composition of transgenic durum wheat: effects on glutenin polymer size and gluten functionality. Mol Breed. 2005;16:113–126. doi: 10.1007/s11032-005-5912-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Herpen TWJM, et al. The origin and early development of wheat glutenin particles. J Cereal Sci. 2008;48:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2008.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Don C, Mann G, Bekes F, Hamer RJ. HMW-GS affect the properties of glutenin particles in GMP and thus flour quality. J Cereal Sci. 2006;44:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2006.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q, et al. Tannins improve dough mixing properties through affecting physicochemical and structural properties of wheat gluten proteins. Food Res Int. 2015;69:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Y, et al. Konjac glucomannan-induced changes in thiol/disulphide exchange and gluten conformation upon dough mixing. Food Chem. 2014;143:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh BR, Deoliveira DB, Fu FN, Fuller MP, Mantsch HH. Fourier transform infrared analysis of amide III bands of proteins for the secondary structure estimation. Proc SPIE. 1993;1890:47–55. doi: 10.1117/12.145242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cai S, Singh BR. A distinct utility of the amide III infrared band for secondary structure estimation of aqueous protein solutions using partial least squares methods. Biochem. 2004;43:2541–2549. doi: 10.1021/bi030149y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.