Abstract

Background

In the cetuximab after progression in KRAS wild-type colorectal cancer patients (CAPRI) trial patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) received 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) and cetuximab in first line followed by 5-Fluorouracil, folinic acid, oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) with or without cetuximab until progression. Limited data are available on the efficacy and safety of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) agents on elderly patients with mCRC. In the current study we evaluated the efficacy and safety of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab in age-defined subgroups.

Methods

A post-hoc analysis was performed in CAPRI trial patients; outcomes (progression-free survival (PFS), overall response rate (ORR), safety) were analysed by age-groups and stratified according to molecular characterisation. 3 age cut-offs were used to define the elderly population (≥65; ≥70 and ≥75 years).

Results

340 patients with mCRC were treated in first line with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab. Among those, 154 patients were >65 years, 86 >70 years and 35 >75 years. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed in 182 patients. Among them, 87 patients were >65 years, 46 >70 and 17 >75. 104 of 182 patients were wild type (WT) for KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA genes. In the quadruple WT group, 51 patients were ≥65 years; 29 were ≥70; 9 were ≥75. Median PFS was similar within the age-subgroups in the intention-to-treat population, NGS cohort and quadruple WT patients, respectively. Likewise, ORR was not significantly different among age-subgroups in the 3 populations. Safety profile was acceptable and similarly reported among all age-groups, with the exception of grade ≥3 diarrhoea (55% vs 25%, p=0.04) and neutropaenia (75% vs 37%, p=0.03) in patients ≥75 years and grade ≥3 fatigue (31% vs 20%, p=0.01) in patients <75 years.

Conclusions

Tolerability of cetuximab plus FOLFIRI was acceptable in elderly patients. Similar ORR and PFS were observed according to age-groups. No differences in adverse events were reported among the defined subgroups with the exception of higher incidence of grade ≥3 diarrhoea and neutropaenia in patients ≥75 years and grade ≥3 fatigue in patients <75 years.

Trial Registration number

Keywords: colorectal cancer, cetuximab, FOLFIRI, NGS, elderly

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Despite the fact that the elderly represent a large proportion of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), geriatric population is often under-represented in controlled clinical trials. Limited prospective data are currently available in molecularly selected elderly patients eligible for anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) treatment in combination with chemotherapy.

What does this study add?

The present study presents the results of a post-hoc exploratory analysis of cetuximab after progression in KRAS wild-type colorectal cancer patients (CAPRI trial). 5-Fluorouracil, folinic acid and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) in combination with cetuximab is equally effective, as first-line regimen, in both young and elderly population of patients with mCRC fit for chemotherapy. No significant difference was observed in efficacy end points among the age-groups analysed.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Our data support the importance of careful selection of patients, intensive clinical monitoring and early identification of adverse events for the elderly population fit for doublet chemotherapy plus anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody.

Introduction

The addition of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) agents, such as cetuximab and panitumumab, to first-line chemotherapy have shown to dramatically improve outcomes in patients with molecularly selected metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC),1–6 reaching 33 months in overall survival (OS). Indeed, KRAS and NRAS mutations have been established as negative predictive biomarkers of response to anti-EGFR drugs. Thus, in November 2013, European Medicines Agency (EMA) reviewed the selection criteria for the treatment of mCRC and prescription of anti-EGFR-targeted agents have been restricted to patients with wild-type (WT) RAS tumours in follow-up to (Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use) CHMP request.

Colorectal cancer is predominantly diagnosed in older adults, representing the second leading cause of death from cancer in men aged 60–79 years and the third most common cause in women aged 60–79.7

Despite the large number of elderly patients with mCRC routinely seen in clinical practice, geriatric population is often under-represented in clinical trials. Furthermore, the elderly represent a heterogonous group, whose frailty not always corresponds to age itself but more often depends on correlative variables such as performance status, number of comorbidities and presence of social support. Several cut-offs have been used in the literature to define elderly population, ranging from 65 to 80 years.8 9 Although prospective data from phase II and III studies have demonstrated the potential benefit of bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine in first-line treatment in elderly patients with mCRC unfit for upfront oxaliplatin-based or irinotecan-based combination regimens,10–12 limited prospective data are currently available in molecularly selected patients eligible for anti-EGFR treatment in combination with chemotherapy.8

A recent retrospective analysis from CRYSTAL study has shown that cetuximab in combination with 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) improve outcomes in both young and older patients with WT RAS. Moreover, the intention-to-treat (ITT) population has not been centrally reassessed for KRAS exon 2 mutations. Full data have not been yet presented.13

The present paper discusses the results of a post-hoc exploratory analysis of the phase II study Cetuximab after progression in KRAS wild-type colorectal cancer patients (CAPRI) population, treated in first line with cetuximab in combination with FOLFIRI in order to explore the efficacy and safety of study treatment within three age-defined subgroups.

Methods

Study overview

CAPRI was an academic, open-label, multicentre phase II trial (Eudract number: 2009-014041-81) performed by the GOIM cooperative group in 25 hospitals in Italy. As previously reported,2 3 14 patients aged 18 years or older, with WT KRAS exon 2 histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (as assessed by local pathology detection), with measurable metastatic disease, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–1, were treated in first line with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Patients achieving complete response (CR), partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) were centrally randomised (1:1), stratified according to performance status and to BRAF mutation, to receive 5-Fluorouracil, folinic acid, oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) plus cetuximab or FOLFOX. All patients provided informed consent before inclusion. The trial was approved by the ethics committees of each trial centre and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Eligibility criteria have been previously described.2 14 The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS) and secondary end points were OS, response rate (RR) and safety. A post-hoc analysis was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cetuximab in combination with FOLFIRI in first-line treatment within age-defined subgroups. In order to explore all ranges previously used in mCRC, three age cut-offs were used to define elderly population (≥65; ≥70 and ≥75 years).

Multiple gene mutation analysis by next-generation sequencing (NGS)

Tumour samples were retrospectively analysed with the Ion Ampliseq Colon and Lung Cancer Panel using Ion Torrent sequencing, evaluating 87 hotspots regions of 22 genes, as previously described. This trial was designed and started before KRAS (exon 3 and 4) and NRAS (exon 2, 3 and 4) mutations were identified, in addition to KRAS exon 2 mutations, as predictors of intrinsic resistance to anti-EGFR treatment. From November 2013, when the EMA reviewed the selection criteria for treatment of patients with mCRC with cetuximab or panitumumab, only patients whose tumours were RAS WT (KRAS exons 2, 3, 4 and NRAS exons 2, 3, 4) were eligible and enrolled in the trial. Samples were reassessed for the presence of KRAS exon 2 (codons 12 and 13) mutations.

Statistical analysis

The study was initiated in July 2009 and screened ∼600 patients for KRAS exon 2 mutations to identify at least 320 patients eligible for first-line treatment with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab. Finally, 340 patients were recruited in first-line treatment with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate median PFS time, p values were calculated using log-rank tests at a significance level of 5%. Differences between categorical data within age-subgroups were measured using parametrical tests, χ2 and Fisher exact test, when adequate. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS statistics V.22.0.

Results

Patients' characteristics

From July 2009 to June 2013, 340 patients (ITT population) were enrolled in CAPRI trial and were treated in first line with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Median age of study population was 64 years old (IQR 55–70 years). Of the 340 CAPRI study patients with tumours previously typed as KRAS exon 2 WT by local pathology detection, 182 samples (53.5%) were collected and centrally assessed by NGS, as previously reported.2 14 NGS analysis identified a subgroup of 104 patients ‘quadruple WT’ for KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA genes (57.1%) showing a better outcome as compared with patients carrying either KRAS, NRAS, BRAF or PIK3CA mutations.2 Within the ITT population, 154 patients (45.3%) were aged ≥65 years; 86 (25.3%) ≥70 years; and 35 (10.3%) ≥75 years at study entry. Among the 182 patients, whose samples were available for NGS analysis, 87 (47.8%) were aged ≥65 years; 46 (25.3%) ≥70 years; and 17 (9.3%) ≥75 years. In the ‘quadruple WT’ group, 51 patients of 104 (49.0%) were aged ≥65 years; 29 (27.8%) ≥70 years; and 9 (8.6%) ≥75 years (see online supplementary table S1). Baseline characteristics by age were well balanced between the patient groups.

esmoopen-2016-000086supp001.pdf (106.2KB, pdf)

Efficacy according to age-subgroups

As previously reported,2 14 the overall response rate (ORR) was 56.4% in the ITT population and 57.1% in the NGS cohort. According to the age-subgroups, in ITT population, the subgroup of patients <65 and ≥65 years obtained an ORR of 57.5% and 55.2%, respectively (p=0.66) (table 1A); patients younger than 70 and older than 70 years reported an ORR of 58.3% and 51.2%, respectively (p=0.25) (table 2A); finally, patients <75 and ≥75 years old had comparable ORR, 56.4% vs 57.1%, respectively (p=0.93) (table 3A). Moreover, no difference was observed in SD and progression of disease (PD) rates in the ITT population within the three subgroups (tables 1A, 2A and 3A).

Table 1.

Response rate in patients aged <65 and ≥65 years

| (A) Response rateITT populationn=340 | Age <65 yearsn=186 | Per cent | Age ≥65 yearsn=154 | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 15 | 8.1 | 18 | 11.7 |

| SD | 64 | 34.4 | 51 | 33.1 |

| PR | 92 | 49.5 | 74 | 48.1 |

| CR | 15 | 8.1 | 11 | 7.1 |

| (B) Response rateNGS cohortn=182 | Age <65 yearsn=95 | Per cent | Age ≥65 yearsn=87 | Per cent |

| PD | 7 | 7.4 | 10 | 11.5 |

| SD | 34 | 35.8 | 27 | 31.0 |

| PR | 47 | 49.5 | 45 | 51.7 |

| CR | 7 | 7.4 | 5 | 5.7 |

| (C) Response rateKRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA WTn=104 | Age <65 yearsn=53 | Per cent | Age ≥65 yearsn=51 | Per cent |

| PD | 3 | 5.7 | 6 | 11.8 |

| SD | 15 | 28.3 | 13 | 25.5 |

| PR | 30 | 56.6 | 29 | 56.9 |

| CR | 5 | 9.4 | 3 | 5.9 |

ITT population (1A), NGS cohort (1B) and KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA WT patients (1C).

CR, complete response; ITT, intention to treat; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PD, progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; WT, wild type.

Table 2.

Response rate in patients aged <70 and ≥70 years

| (A) Response rate ITT population n=340 |

Age <70 years n=254 |

Per cent | Age ≥70 years n=86 |

Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 20 | 7.9 | 13 | 15.1 |

| SD | 86 | 33.9 | 29 | 33.7 |

| PR | 128 | 50.4 | 38 | 44.2 |

| CR | 20 | 7.9 | 6 | 7.0 |

| (B) Response rate NGS cohort n=182 |

Age <70 years n=136 |

Per cent |

Age ≥70 years n=46 |

Per cent |

| PD | 10 | 7.4 | 7 | 15.2 |

| SD | 46 | 33.8 | 15 | 32.6 |

| PR | 70 | 51.5 | 22 | 47.8 |

| CR | 10 | 7.4 | 2 | 4.3 |

| (C) Response rate KRAS/NRAS/ BRAF/PIK3CA WT n=104 |

Age <70 years n=75 |

Per cent |

Age ≥70 years n=29 |

Per cent |

| PD | 4 | 5.3 | 5 | 17.2 |

| SD | 20 | 26.7 | 8 | 27.6 |

| PR | 44 | 58.7 | 15 | 51.7 |

| CR | 7 | 9.3 | 1 | 3.4 |

ITT population (1A), NGS cohort (1B) and KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA WT patients (1C).

CR, complete response; ITT, intention to treat; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PD, progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; WT, wild type.

Table 3.

Response rate in patients aged <75 and ≥75 years

| (A) Response rate ITT population n=340 |

Age <75 years n=305 |

Per cent | Age ≥75 years n=35 |

Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 30 | 9.8 | 3 | 8.6 |

| SD | 103 | 33.8 | 12 | 34.3 |

| PR | 148 | 48.5 | 18 | 51.4 |

| CR | 24 | 7.9 | 2 | 5.7 |

| (B) Response rate NGS cohort n=182 |

Age <75 years n=165 |

Per cent |

Age ≥75 years n=17 |

Per cent |

| PD | 16 | 9.7 | 1 | 5.9 |

| SD | 54 | 32.7 | 7 | 41.2 |

| PR | 83 | 50.3 | 9 | 52.9 |

| CR | 12 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| (C) Response rate KRAS/NRAS/ BRAF/PIK3CA WT n=104 |

Age <75 years n=95 |

Per cent |

Age ≥75 years n=9 |

% |

| PD | 9 | 9.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| SD | 26 | 27.4 | 2 | 22.2 |

| PR | 52 | 54.7 | 7 | 77.8 |

| CR | 8 | 8.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

ITT population (1A), NGS cohort (1B) and KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA WT patients (1C).

CR, complete response; ITT, intention to treat; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PD, progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; WT, wild type.

Similar efficacy data were reported in the NGS cohort, where ORR was comparable in the subgroups defined by the three age cut-offs, 65, 70 and 75 years: 58.3% vs 51.2% (p=0.25); 58.8% vs 52.2% (p=0.43); 68.0% vs 55.2% (p=0.22) (tables 1B, 2B and 3B), confirming that the NGS cohort is representative of the entire ITT population.

Likewise, among patients with WT tumours for KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA, consistent results were obtained in the age groups: in patients <65 years ORR was 56.4% vs 57.1% in ≥65 years (p=0.93) (table 1C); in patients <70 years was 57.6% vs 52.9% in ≥70 years (p=0.71) (tables 2C); among patients <75 years ORR was 63.2% vs 77.8% in ≥75 years (p=0.38) (table 3C).

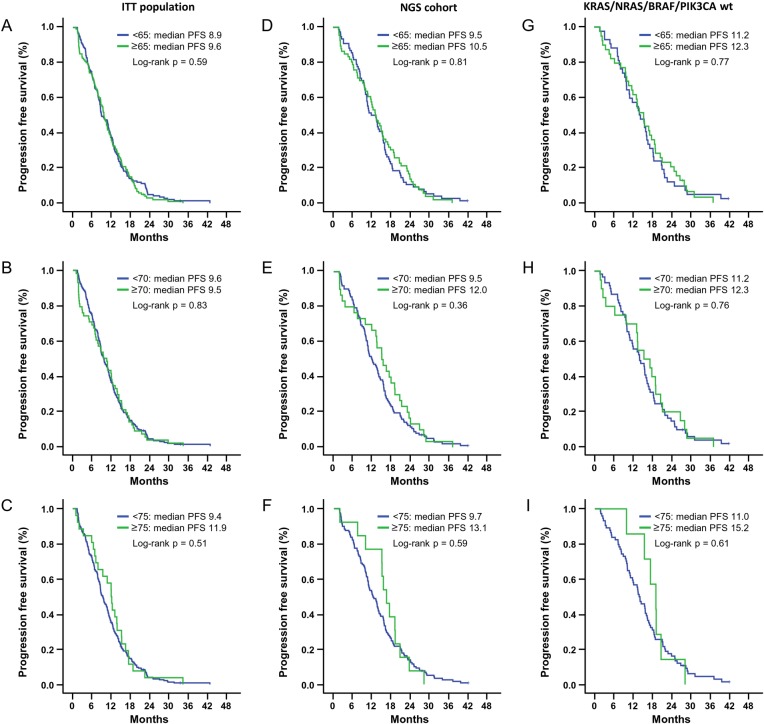

Treatment with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab resulted in comparable efficacy for the primary end point of the study, PFS. In particular, in the ITT population, the median PFS was 8.9 months (95% CI 7.2 to 10.7) in patients aged <65 years and 9.6 months (95% CI 8.4 to 10.9) in those ≥65 years (p=0.59) (figure 1A); median PFS of 9.6 months in patients <70 years (95% CI 8.3 to 11.0) and 9.5 months (95% CI 6.9 to 12.0) in ≥70 years (p=0.83) (figure 1B); median PFS of 9.4 months in patients <75 years (95% CI 8.3 to 10.5) and 11.9 months (95% CI 10.0 to 13.9) in ≥75 years (p=0.51) (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier of progression free survival (PFS) in intention-to-treat (ITT) population (A,B,C), next-generation sequencing (NGS) cohort (D,E,F) and KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and patients with PIK3CA wild type (WT) (G,H,I) according to age-subgroup analysis.

In patients whose tumour was available for NGS analysis, median PFS in <65 years was 9.5 months (95% CI 6.9 to 12.1) vs 10.5 months (95% CI 8.5 to 12.5) in those ≥65 years (p=0.81) (figure 1D); in <70 years 9.5 months (95% CI 7.6 to 11.4) vs 12.0 months (95% CI 8.8 to 15.1) in ≥70 years (p=0.36) (figure 1E); in <75 years 9.7 months (95% CI 8.1 to 11.3) vs 13.1 months (95% CI 10.9 to 15.3) in ≥75 years (p=0.59) (figure 1F).

Finally, in KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA WT patients, median PFS in <65 years was 11.2 months (95% CI 8.0 to 14.4) vs 12.3 months (95% CI 10.1 to 14.5) in those ≥65 years (p=0.77) (figure 1G); in <70 years 11.2 months (95% CI 8.2 to 14.3) vs 12.3 months (95% CI 5.7 to 18.9) in ≥70 years (p=0.76) (figure 1H); in <75 years 11.0 months (95% CI 9.1 to 12.9) vs 15.2 months (95% CI 11.7 to 18.7) in ≥75 years (p=0.61) (figure 1I). The median number of treatment cycles was 12 in all subgroups (IQR 5–20 cycles).

Safety profile according to age-subgroups

Overall, the safety profile of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab was comparable among the age-subgroups in the ITT population (table 4A–C). The incidence of all grade haematological adverse events (AEs) was similar in younger and elderly patients. Neutropaenia was the most common haematological AE and all grade incidence rates were comparable in the ITT population analysed according with the three age cut-offs. However, patients ≥75 years experienced higher rate of grade 3–4 neutropaenia (75%) compared with patients aged <75 years (37% p=0.03) (table 4C). All grades non-haematological AEs were reported to be similar in the three age-subgroups. Nausea and vomiting were the most reported AEs in the overall population and no significant difference was seen among the age groups. Skin reactions were comparable among the three subgroups and no difference was observed in grade 3–4 toxicities. As table 4C shows that in patients ≥75 years a significant difference in grade 3–4 diarrhoea rates was observed (55%) compared with patients younger than 75 years (25%, p=0.04). Conversely, significantly higher grade 3–4 fatigue rates were reported in <75 years patients (31%) compared with elderly population (20%, p=0.01) (table 4C).

Table 4.

Adverse events in intention-to-treat (ITT) population according with age-subgroups

| Age <65 years (n=186) |

Age ≥65 years (n=154) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Adverse event | All grade | Per cent | Grade 3–4 | Per cent | All grade | Per cent | Grade 3–4 | Per cent | p Value |

| Anaemia | 30 | 16 | 3 | 10 | 24 | 16 | 4 | 17 | 0.46 |

| Leucopenia | 16 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 19 | 12 | 5 | 26 | 0.30 |

| Neutropaenia | 37 | 20 | 16 | 43 | 41 | 27 | 16 | 39 | 0.70 |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 3 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 0.32 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 75 | 40 | 7 | 9 | 46 | 30 | 8 | 17 | 0.19 |

| Diarrhoea | 60 | 32 | 14 | 23 | 46 | 30 | 16 | 35 | 0.19 |

| Fatigue | 61 | 33 | 17 | 28 | 43 | 28 | 14 | 33 | 0.60 |

| Skin reactions | 52 | 28 | 8 | 15 | 38 | 25 | 6 | 16 | 0.95 |

| (B) Adverse event | Age <70 years (n=254) | Age ≥70 years (n=86) | p Value | ||||||

| All grade | Per cent | Grade 3–4 | Per cent | All grade | Per cent | Grade 3–4 | Per cent | ||

| Anaemia | 39 | 15 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 1 | 7 | 0.39 |

| Leucopenia | 22 | 9 | 4 | 18 | 13 | 15 | 3 | 23 | 0.72 |

| Neutropaenia | 57 | 22 | 23 | 40 | 21 | 24 | 9 | 43 | 0.84 |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 7 | 3 | 1 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 17 | 0.90 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 93 | 37 | 10 | 11 | 28 | 33 | 5 | 18 | 0.31 |

| Diarrhoea | 83 | 33 | 20 | 24 | 23 | 27 | 10 | 43 | 0.06 |

| Fatigue | 81 | 32 | 25 | 31 | 23 | 27 | 6 | 26 | 0.65 |

| Skin reactions | 71 | 28 | 10 | 14 | 19 | 22 | 4 | 21 | 0.55 |

| (C) Adverse event | Age <75 years (n=305) | Age ≥75 years (n=35) | p Value | ||||||

| All grade | Per cent | Grade 3–4 | Per cent | All grade | Per cent | Grade 3–4 | Per cent | ||

| Anaemia | 48 | 16 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 0.77 |

| Leucopenia | 33 | 11 | 6 | 18 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 50 | 0.27 |

| Neutropaenia | 70 | 23 | 26 | 37 | 8 | 23 | 6 | 75 | 0.03 |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 11 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 50 | 0.14 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 107 | 35 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 40 | 3 | 21 | 0.27 |

| Diarrhoea | 95 | 31 | 24 | 25 | 11 | 31 | 6 | 55 | 0.04 |

| Fatigue | 94 | 31 | 29 | 31 | 10 | 29 | 2 | 20 | 0.01 |

| Skin reactions | 82 | 27 | 13 | 16 | 8 | 23 | 1 | 13 | 0.80 |

Patients aged <65 and ≥65 (4A), aged <70 and ≥70 (4B), aged <75 and ≥75 years (4C).

Conclusions

In the era of precision medicine, treatment of mCRC in the elderly population is a challenge for medical oncologists. Few studies have assessed the role of the anti-EGFR agents in combination with chemotherapy in the elderly population8 and limited data are currently available for the combination of cetuximab plus FOLFIRI in first-line setting.13 15–17 The results of this post-hoc analysis show that FOLFIRI in combination with cetuximab is equally effective, as first-line regimen, in both young and elderly population fit for chemotherapy and no significant difference was observed in efficacy end points among the age-groups analysed. Moreover, these results are in line with those previously reported in the ITT CAPRI population.2

Regarding safety profile, treatment was well tolerated by both younger and older patients. The incidence of all grade AEs was similar among the three age-subgroups and consistent with drugs toxicity profile. It should be noted that in patients ≥75 years, higher rates of grade 3–4 diarrhoea and neutropaenia were recorded, nevertheless, no hospitalisation was required. These data are consistent with previous reports of G3–4 toxicity in elderly patients treated in first line with cetuximab plus chemotherapy9 16–20 and confirm the importance of close monitoring of potentially serious side effects in older patients, for whom lower bone marrow reserves might induce prolonged neutropaenia, while severe diarrhoea increases the risk of malnutrition, dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

In order to recognise elderly patients fit for chemotherapy, age should not be the only parameter to be used. This evaluation should be done within a multidisciplinary and multidimensional analysis, as a part of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). This study is limited by the lack of preplanned CGA and cumulative illness rating scale assessment in the elderly population, since CAPRI ITT population was not specifically selected to perform any age-subgroup analysis.

Furthermore, to optimise treatment outcomes, molecular data should be the basis of selection of patients. Within the limitation of a retrospective subgroup analysis, our study suggests that elderly patients, fit for chemotherapy, re-examined for KRAS exon 2 status and assessed as ‘quadruple WT’ according to an extended gene analysis, including KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA, have the same benefit from first-line treatment with cetuximab in combination with FOLFIRI compared with younger population.

Our data support the importance of careful selection of patients, intensive clinical monitoring and early identification of AEs for the elderly population fit for doublet chemotherapy plus anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody; however, phase III randomised controlled trial should be carried out to provide more definitive evidence on role of chemotherapy in combination with anti-EGFR drugs in the elderly population, including a CGA within a multidisciplinary evaluation.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Erika Martinelli @Erikamartinelli

Collaborators: The following CAPRI-GOIM investigators participated to this study and are coauthors of the article: Istituto Nazionale Tumori “Fondazione Giovanni Pascale” IRCCS, Napoli: Vincenzo. Iaffaioli, Guglielmo Nasti, Anna Nappi, Gerardo Botti, F. Tatangelo, Nicoletta Chicchinelli; Stabilimento SS. Annunziata, Taranto: Mirko Montrone, Annamaria Sebastio, Tiziana Guarino; IRCCS Giovanni Paolo II, Bari: Gianni Simone; IRCCS Ospedale Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo (FG): Paolo Graziano, Cinzia Chiarazzo, Gabriele Di Maggio; Nuovo Ospedale Garibaldi, Nesima, Catania: Laura Longhitano, Mario Manusia; Azienda Ospedaliera “A. Cardarelli,” Napoli: Giacomo Cartenì, Oscar Nappi; Ospedale Monaldi-Azienda Ospedaliera dei Colli, Napoli: Pietro Micheli, Luigi Leo; Policlinico Universitario “A. Gemelli”, Roma: Sabrina Rossi, Alessandra Cassano; Ospedale Sacro Cuore di Gesù Fatebenefratelli, Benevento: Eugenio Tommaselli, Guido Giordano; Ospedale “A. Perrino”, Brindisi: Francesco Sponziello, Antonella Marino; Presidio Ospedaliero Polo Occidentale, Castellaneta (BA): Antonio Rinaldi; A.O. Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti Di Foggia, Foggia: Sante Romito; Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Rome: Andrea Onetti Muda; Ospedale Vito Fazzi, Lecce: Vito Lorusso, Silvana Leo; Azienda Ospedaliera, Treviglio (BG): Sandro Barni; Ospedale Umberto I, Nocera Inferiore: Giuseppe Grimaldi; CROB-IRCCS, Rionero in Vulture (PZ): Michele Aieta.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Gruppo Oncologico dell’ Italia Meridionale (GOIM). Cetuximab was provided free of charge by Merck Serono, Italy. Merck Serono provided also an unrestricted research grant to partially cover administrative costs of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Local Ethical Committees, AIFA.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Vincenzo Iaffaioli, Guglielmo Nasti, Anna Nappi, Gerardo Botti, F. Tatangelo, Nicoletta Chicchinelli, Mirko Montrone, Annamaria Sebastio, Tiziana Guarino, Gianni Simone, Paolo Graziano, Cinzia Chiarazzo, Gabriele Di Maggio, Laura Longhitano, Mario Manusia, Giacomo Cartenì, Oscar Nappi, Pietro Micheli, Luigi Leo, Sabrina Rossi, Alessandra Cassano, Eugenio Tommaselli, Guido Giordano, Francesco Sponziello, Antonella Marino, Antonio Rinaldi, Sante Romito, Andrea Onetti Muda, Vito Lorusso, Silvana Leo, Sandro Barni, Giuseppe Grimaldi, and Michele Aieta

References

- 1.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1023–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciardiello F, Normanno N, Maiello E, et al. Clinical activity of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab according to extended gene mutation status by next-generation sequencing: findings from the CAPRI-GOIM trial. Ann Oncol 2014;25:1756–61. 10.1093/annonc/mdu230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Normanno N, Rachiglio AM, Lambiase M, et al. Heterogeneity of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer and potential effects on therapy in the CAPRI GOIM trial. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1710–14. 10.1093/annonc/mdv176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Köhne CH, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:692–700. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1065–75. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenz H, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/5-FU/leucovorin (FOLFIRI) or oxaliplatin/5-FU/leucovorin (mFOLFOX6) with bevacizumab (BV) or cetuximab (CET) for patients (PTs) with expanded RAS analyses untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (mCRC). Ann Oncol 2014;25(Suppl 4). 10.1093/annonc/mdu438.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29. 10.3322/caac.21254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosati G, Aprile G, Cardellino GG, et al. A review and assessment of currently available data of the EGFR antibodies in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2016;7:134–41. 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelwahab S, Azmy A, Abdel-Aziz H, et al. Anti-EGFR (cetuximab) combined with irinotecan for treatment of elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2012;138:1487–92. 10.1007/s00432-012-1229-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham D, Lang I, Marcuello E, et al. AVEX study investigators. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1077–85. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70154-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feliu J, Safont MJ, Salud A, et al. Capecitabine and bevacizumab as first-line treatment in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2010;102:1468–73. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrdoljak E, Omrc˘en T, Boban M, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine as first-line treatment in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Drugs 2011;22:191–7. 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283417f3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Folprecht G, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line cetuximab + FOLFIRI in older and younger patients (PTs) with RAS wild-type (WT) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) in the CRYSTAL study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(Suppl 4S). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciardiello F, Normanno N, Martinelli E, et al. Cetuximab continuation after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (CAPRI-GOIM): a randomized phase II trial of FOLFOX plus cetuximab versus FOLFOX. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1055–61. 10.1093/annonc/mdw136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahm S, Goehler T, Hering-Schubert C, et al. Outcome of patients with KRAS exon 2 wild type (KRAS-WT) metastatic colorectal carcinoma (mCRC) with cetuximab-based first-line treatment in the noninterventional study ERBITAG and impact of comorbidity and age. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(Suppl 4S). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bokemeyer C, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, et al. Addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy as first-line treatment for KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS randomised clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1466–75. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folprecht G, Köhne C, Bokemeyer C, et al. Cetuximab and 1st-line chemotherapy in elderly and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC): a pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS studies. Milan: European Cancer Congress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouchahda M, Macarulla T, Spano JP, et al. Cetuximab efficacy and safety in a retrospective cohort of elderly patients with heavily pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2008;67:255–62. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dotan E, Devarajan K, D'Silva AJ, et al. Patterns of use and tolerance of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies in older adults with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2014;13:192–8. 10.1016/j.clcc.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sastre J, Grávalos C, Rivera F, et al. First-line cetuximab plus capecitabine in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer: clinical outcome and subgroup analysis according to KRAS status from a Spanish TTD group study. Oncologist 2012;17:339–45. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

esmoopen-2016-000086supp001.pdf (106.2KB, pdf)