Abstract

Recent evidence suggests negative associations between received social support and emotional well-being. So far, these studies mainly focused on younger adults. Quantity and quality of social support changes with age; therefore, this study investigated whether there are age differences regarding the association between received social support and positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). Moreover, it was tested whether these age effects might be due to a differential effectiveness of different sources of support for younger and older individuals. Forty-two individuals (21 younger adults, aged 21–40 and 21 older adults, aged 61–73) completed 30-daily diaries on their received social support, PA/NA and the sources of support provision. Data were analyzed using multilevel modeling. Results indicated age-related differential effects: for younger individuals, received social support was negatively associated with indicators of emotional well-being, whereas these associations were positive for older respondents. Regarding NA, these effects held when testing lagged predictions and controlling for previous-day affect. No age differences emerged regarding the associations between different sources of support and indicators of affect. Conceptual implications of these age-differential findings are discussed.

Keywords: Social support, Age differences, Positive and negative affects, Daily diaries

Introduction

Social support is generally perceived as being beneficial for an individual’s well-being. Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive effects of social support on mental (e.g., Hays et al. 2001) and physical well-being (e.g., Uchino et al. 1996). There are, however, studies that demonstrate no (Knoll et al. 2007a) or even negative effects of social support on well-being (e.g., Bolger et al. 2000). These heterogeneous results may in part be due to different operationalizations of support, that is perceived and received support (e.g., Norris and Kaniasty 1996; Schwarzer and Knoll 2010). Perceived social support comprises the potential availability of support from the social network is prospectively assessed and is known to be relatively stable over time (Sarason et al. 1990). Moreover, it depends only little on actual support transactions (e.g., Knoll et al. 2007b). On the other hand, received social support refers to recipients’ retrospective reports of actual support transactions (e.g., Norris and Kaniasty 1996; Schwarzer and Knoll 2010).

In terms of positive and negative associations with well-being under stress, perceived social support is almost consistently positively related to an individual’s well-being (Cohen 2004). In contrast, so far, received social support as a predictor has yielded inconsistent findings with regard to emotional well-being outcomes: although positive associations with well-being are reported (e.g., Kleiboer et al. 2006), oftentimes results indicate non-significant (e.g., Knoll et al. 2007a) or even negative associations with well-being (e.g., Bolger et al. 2000).

From a conceptual perspective, at least three potential explanations for these unexpected non- or even negative associations are currently under debate: first, the support might undermine the recipients’ self-worth (Bolger and Amarel 2007). Second, the receipt of support could simply be a reaction of the social environment to an increased stress level (i.e., low well-being) of an individual (“reverse causation”, Seidman et al. 2006). Third, the support received might not meet the needs of the recipient (e.g., Martire et al. 2002). From a lifespan perspective, it is remarkable that, so far, all the studies on negative effects of received social support on well-being focused on young- and middle-aged individuals (e.g., Bolger et al. 2000). As the composition of the social network and thus of the sources of social support changes dramatically with increasing age, this study aimed at addressing age differences in the conceptual alternatives by examining whether the patterns of relationships between received social support and indicators of well-being also apply for older people.

Age differences of social support

Aging is characterized by a number of changes in social network constellations. The network size may decrease with age (e.g., Lang 2001); however, despite a decrease in quantity, quality of social interaction may not necessarily be diminished. Theories of social network composition over the lifespan agree that older individuals actively compose their social networks. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) proposes that aging individuals primarily follow emotionally meaningful goals instead of future-oriented goals. As a consequence, to meet these emotionally meaningful goals, older individuals actively select emotionally meaningful relationships and rather abandon others (e.g., Carstensen et al. 1999; Lang 2001). It has been demonstrated that the network-related selection processes in older age are rather driven by seeking emotional meaning than by seeking emotional support, with emotionally close individuals becoming typical sources of emotional support (Fung and Carstensen 2004). In contrast, networks of younger persons comprise more diverse sources of support, such as work colleagues or acquaintances (e.g., Levitt et al. 1993). Thus, selecting a social network mainly consisting of emotionally close social interaction partners may lead to an increased match between receipt of and needs for emotional support by the older individual (Krause 2005). This, in turn, should make it less likely that received social support negatively affects well-being in older adults. In contrast, the same might not necessarily be the case for younger adults. Receiving emotional social support from more distal interaction partners might indeed increase the possibility of mismatching the needs of the receiver or of undermining the recipient’s self-worth. As a consequence, received social support might have negative effects on well-being or affective states (Bolger and Amarel 2007; Martire et al. 2002). This study set out to test those age-differential predictions.

Additionally, it has been demonstrated that associations between received support and depression were different for young and old individuals depending on the source of support (Okun and Keith 1998). Sources of support in this study were partner, children, and other relatives/friends. For younger individuals, only support received from their partner was associated with lower depressive symptoms, whereas for older persons support from all sources was predictive of lower depressive symptoms. Moreover, research with young- and old-aged individuals demonstrated that with increasing age positive associations between social support and well-being become stronger (e.g., Li and Liang 2007; Krause 2005). This again might be explained by differences in the sources of support across ages: receiving emotional social support from close social network partners, which is more likely for older adults due to the selective composition of the social network, might be more beneficial for one’s well-being than received emotional social support from both close and distal social network partners, as it should be the case for younger adults. Following this conceptual rationale, the source of social support might make a crucial difference regarding the effects of received social support on well-being. Thus, it can be expected that older adults are less likely to experience the negative effects of received social support known from research with younger adults (e.g., Bolger et al. 2000).

This study

So far, research considering age-differential associations of social support with well-being was cross-sectional. The negative effects of received social support on affect indicators among younger adults, however, were usually analyzed applying a daily-diary approach to test associations on the intrapersonal level and to control for changes across times. Taking changes across time into account is especially important, because one potential mechanism for the negative associations between received social support and well-being is “reverse causation.” This means that people with lower well-being receive more social support (Seidman et al. 2006). This study applied a daily-diary design to control for the possibility of reverse causation and to investigate possible short-term reactions to receipt of support.

Moreover, many studies on social support effects on well-being focus on negative aspects of well-being, such as depressive symptoms (e.g., Okun and Keith 1998) or negative mood (e.g., Bolger et al. 2000). Positive aspects of well-being have been focused on less often. Thus, this study included both positive and negative measures of affect.

Taken together, the aim of our study was twofold. First, we investigated age differences in the associations of received emotional social support on positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) applying a daily-diary design. Based on the conceptual rationale outlined above, we predicted that older individuals would exhibit positive associations between received emotional support and PA and negative associations between received support and NA. Associations in the opposite directions were predicted for younger persons. These differential age effects should hold when controlling for previous-day positive or NA, thereby excluding the possibility of reverse causation (Seidman et al. 2006). Second, further extending the literature, we aimed at testing whether the association between different sources of support and PA and NA might be moderated by age. Based on assumptions of SST (Carstensen et al. 1999), we hypothesized that due to their selective network composition of emotionally meaningful and close sources of support, older adults may benefit from all sources of support in terms of their PA and NA, whereas younger adults may not.

Method

Sample and procedure

Forty-two (Swiss)-German-speaking individuals (57.1 % women) from the German-speaking regions of Switzerland were recruited from the departmental participant pool and by convenience sampling, applying a snowball method. The study was advertised among university students who were asked to recruit potential respondents in their wider circles of acquaintances and then participants were asked to inform other potential respondents about the study. Twenty-one respondents were between 21 and 40 years of age (M = 30.86, SD = 5.53) and 21 were between 61 and 73 years of age (M = 66.38, SD = 3.26). Fourteen participants were single (33.3 %) and 28 (66.7 %) were married or living in a domestic partnership. In terms of highest degree of education, the majority of participants (n = 18, 42.9 %) reported a vocational training, 11 individuals (26.2 %) reported 12 years of schooling, 10 participants (23.8 %) held a university degree, 2 individuals (4.8 %) reported 9 years of schooling, and 1 person (2.4 %) held no graduation. No age differences emerged for education (χ2 = 3.37, df = 5, p = 0.64). The younger participants were either studying or working and the older participants were all retired.

During an individual baseline session all potential respondents gave informed consent to participate. They completed a short questionnaire and were instructed that the 30 daily diaries should be completed each night before going to bed and that each diary should be sent back the next day with one of the provided return envelopes.

Of the 1,260 diaries, only 32 diaries were not returned, resulting in a return rate of 97.46 %. Number of returned diaries was not significantly associated with sex, marital status, or working status, but it was significantly related to age group in that older persons (M = 29.81, SD = 0.51) returned more diaries than younger participants (M = 28.71, SD = 2.19) (t(22.10) = −2.23, p = 0.04).

Measures

Means, standard deviations, range, intraclass correlations (ICC), and age differences for all measures are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, ICC and tests for age differences

| Younger adults | Older adults | Range | ICC | Age differences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Positive affect | 3.00 | 0.36 | 3.28 | 0.59 | 1–5 | 0.35 | t(40) = −1.85# |

| Negative affect | 1.45 | 0.36 | 1.19 | 0.15 | 1–5 | 0.33 | t(26.80) = 3.00** |

| Received social support | 1.37 | 0.34 | 1.22 | 0.26 | 1–2 | 0.43 | t(40) = 1.64 |

| Source: partner | 1.48 | 0.40 | 1.55 | 0.41 | 1–2 | 0.57 | t(33) = −0.57 |

| Source: family | 1.08 | 0.10 | 1.09 | 0.12 | 1–2 | 0.21 | t(33) = −0.41 |

| Source: friends | 1.43 | 0.33 | 1.28 | 0.32 | 1–2 | 0.36 | t(33) = 1.32 |

| Source: acquaintances | 1.13 | 0.13 | 1.05 | 0.10 | 1–2 | 0.24 | t(33) = 2.07* |

| Multimorbidity | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0–5 | – | t(39) = −0.05 |

| Subjective health | 3.76 | 0.94 | 4.0 | 0.63 | 1–5 | – | t(40) = −0.96 |

| Chronic stress | 22.14 | 6.20 | 19.62 | 5.76 | 0–56 | – | t(40) = 1.37 |

| Depressive symptoms | 9.57 | 5.53 | 10.19 | 5.00 | 0–60 | – | t(40) = −0.38 |

| Perceived social support | 3.73 | 0.33 | 3.65 | 0.34 | 1–4 | – | t(40) = 0.80 |

Note The ICC stands for the amount of between-person variance in relation to total variance (Kreft and DeLeeuw 1998)

# p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

For the assessment of PA and NA, we used the PA and NA Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988). The PANAS comprises 20 adjectives with 10 items representing NA and ten items representing PA. Answering format was from 1 to 5 (Not at All, A Little, Moderately, Quite a Bit, or Extremely). PA and NA were negatively associated within persons across days (b = −0.19, p = 0.001).

Received Emotional Social Support was assessed using the following item: “In the last 24 h, did you receive emotional support (such as listening to you, comforting you) from anyone?” Answering format was dichotomous: no (1)–yes (2). This item was taken from the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE; Almeida et al. 2002). The same assessment strategy was applied in earlier social support research (Bolger et al. 2000). Besides the face validity of the item wording, the study by Bolger et al. (2000) demonstrated that receipt of support on a given day was related to increases in anxiety and depression and thus indicating the validity of this single item measure.

Sources of support. In case individuals had positively answered the social support item, they were asked to indicate the sources of support. They could choose the following sources: partner, child(ren), grandchild(ren), other family members, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and were instructed to mark all sources they had received support from. No mark was coded 1, having received support from this source was coded 2. These sources were also taken from the DISE (Almeida et al. 2002). As only those individuals who had received support answered the sources of support items, there was a relatively high amount of logical missing values per day: Seven individuals (17 %) indicated to have never received support at all during the 30 days. Across those 35 individuals who had received support, 343 daily entries indicating the sources were provided. In order to be able to analyze the sources of support nonetheless, the items child(ren), grandchild(ren), other family members were aggregated to the source “family” and the items neighbors and colleagues were aggregated to the source “acquaintances”.

To control whether potential age differences in the effects of received social support on PA and NA can be explained by differences on other variables, the listed below covariates were tested for age differences. All were measured at baseline assessment. For means, standard deviations broken down by age groups and tests for age differences see Table 1.

Health status. Two indicators for health status were used in this study. Multimorbidity was assessed by the number of medical diagnoses reported by participants. Subjective health was rated by a single item asking participants on a scale of very bad (1) to very good (5) how they would describe their present health status.

Chronic stress was assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al. 1983). The scale comprises 14 items with a five-point Likert-scale response format (0 “never” to 4 “very often”). Internal consistency was Cronbach’s alpha was 0.70.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977). The scale comprises 20 items. Persons are asked to report the frequency of occurrence of depressive symptoms during the past week, ranging from 0 (less than a day) to 3 (most of the time [5–7 days]). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.72

Perceived social support was assessed by the perceived social support dimension of the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS; Schulz and Schwarzer 2003). The scale comprises 8 items with a four-point Likert-scale response format (1 “totally disagree” to 4 “totally agree”). A sample item is “Whenever I am sad, there are people who cheer me up.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Data analyses

Although the amount of missing values occurring in this study was small, missings were related to the age of participants and thus systematically biased. Thus, the missing pattern is at best missing at random (MAR; Graham 2009), which means that the probability of missing values on any variable is not related to its particular value, but depends on some other variable. In this case, listwise deletion of persons with missing data would not be the appropriate method for handling missing data. Thus, all participants were included in the analyses. HLM uses Maximum Likelihood estimation for missing values on Level 1 (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). As age was included in all analyses, missing estimation accounted for potential age differences and thus, systematic bias due to age of participants was accounted for. In case of logical missings (e.g., for the sources of support), missings were not estimated.

The data structure of this study was hierarchical because observations were nested in persons. We used multilevel modeling, using the program HLM 6.06 (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). Multilevel modeling allows investigating associations between constructs on both levels of analyses, the within-person and the between-person level. As the first aim of this study was to test for age differences in the associations between received emotional social support and PA and NA we specified two-level models with age group being the Level-2 (i.e., between-person) predictor and all other variables being the time-varying Level-1 (i.e., within-person) predictors. Because there were no age effects on the control variables (see Table 1), none of these variables was included in the analyses. On Level 1, a linear time trend was included in all analyses to control whether the associations between predictors and criterion on the within-person level are due to shared time trends (i.e., methodological artifacts) rather than representing real effects.

To give an example, the Level-1 equation for received social support on NA reads as follows:

|

with y ij being the individual j’s NA across i points of measurement. β0j is individual j’s intercept representing a person’s initial level of NA. β1j and β2j are the slopes representing the within-person association between NA with received social support and the linear time trend, and r ij is the residual variance.

The linear time trend was centered at the first assessment. All Level-1 variables were group mean centered, i.e., the person-specific mean was subtracted from the variable. Group means were then reintroduced as predictors of the intercept on Level 2 and grand-mean centered (Kreft and DeLeeuw 1998). By doing so, it is possible to distinguish effects on the within-person level, in this case fluctuations around the individual mean across points of measurement, from effects of interindividual differences, in this case mean levels across points of measurement, on the outcome.

The sample Level-2 equations for NA are as follows:

|

with γ00 being the sample mean of NA, and γ01 and γ02 the between-person association between NA and received social support and age group. u0j is the random error, i.e., the interindividual variation in β0j. γ10 and γ20 are the average within-person effects of received support and linear time trend, on NA. γ11 is the cross-level interaction between age group and received social support on NA. All predictors were modeled as random (error terms: u1j, u2j), indicating potential interindividual differences in these mean effects.

In order to test for the reverse causation hypotheses, i.e., to test whether the effects of received support on the outcomes holds when controlling for previous-day affect, we also analyzed lagged effects. This means that previous-day (t − 1) received support was specified to predict following-day (t) outcomes while controlling for previous-day (t − 1) affect (i.e., positive or NA) and time trend.

As our second aim was to test whether age moderated the association between source of support and positive or NA, we specified two-level models with age group being the Level-2 (i.e., between-person) predictor and source of support being the time-varying Level-1 (i.e., within-person) predictors. As there were rather few occasions of support reported and thus, relatively few data points for sources of support, we tested the moderation of age on the association between source of support and PA and NA separately for the four different sources. Here again, all effects on level 2 were modeled as random, indicating potential interindividual differences in the mean effects.

As an indicator of effect size, we report a pseudo-R 2 statistic which results from the difference in residual within-person variance between the model with all predictor variables included and a model with all but the predictor of interest included (Kreft and DeLeeuw 1998). However, this is only an approximation to the R 2 known from usual regression models because R 2 cannot be uniquely defined in models with random intercept and random slopes (Kreft and DeLeeuw 1998). This might sometimes also result in failures to compute a pseudo-R 2 for predictors. Thus, the pseudo-R 2s reported should be interpreted with caution.

Results

The ICC (see Table 1) stands for the amount of between-person variance in relation to total variance (Kreft and DeLeeuw 1998). All but one (daily reports of partner as the source of support) ICCs were below 0.5, indicating more within-person than between-person variance.

Associations between affect and social support at the same day

In the model specifying the prediction of PA, random effects of the intercept of PA, of the slope of received social support, and of the linear time trend were significantly different from zero. These random effects indicated interindividual differences in initial levels of PA and in the within-person associations between PA and received social support and linear time trend at the same day.

The model resulted in a non-significant effect of linear time trend and of received social support on PA on the within-person level (see Table 2). The association between received social support and PA, however, was qualified by age group. As displayed in Fig. 1, the association between received social support and PA is negative only for younger but not for older participants. Thus, on days with higher amounts of received social support younger individuals reported lower levels of PA, whereas older participants reported higher levels of PA. This finding was robust for potential underlying linear time trends. In terms of interindividual differences, age group and mean level of received social support across days resulted in significant positive effects on the intercept of PA, indicating that interindividual differences in mean level of received social support across days and older age were positively associated with mean initial levels of PA.

Table 2.

Daily PA and NA as a function of daily received social support and age

| b | SE | p value | Pseudo-R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: daily positive affect | ||||

| Between-person effects | ||||

| Age group | 0.41 | 0.13 | 0.003 | 0.15 |

| Mean level of received support | 0.80 | 0.19 | 0.001 | 0.14 |

| Within-person effects | ||||

| Received support | −0.57 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.05 |

| Linear time trend | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.54 | 0.03 |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||

| Age group × received support | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.07 | DNA |

| Dependent variable: daily negative affect | ||||

| Between-person effects | ||||

| Age group | −0.23 | 0.07 | 0.004 | 0.17 |

| Mean level of received support | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Within-person effects | ||||

| Received support | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.001 | 0.14 |

| Linear time trend | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.90 | 0.02 |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||

| Age group × received support | −0.28 | 0.14 | 0.06 | DNA |

Note Age group coded young = 1, old = 2

DNA does not apply/cannot be computed

Fig. 1.

Within-person associations between social support and PA moderated by age. Note Controlled for linear time trend

In the model specifying the prediction of NA, random effects of the intercept of NA, of the slope of received social support, and of the linear time trend were significantly different from zero. These random effects indicated interindividual differences in initial levels of NA, in the within-person associations of NA with the linear time trend and received social support on the same day.

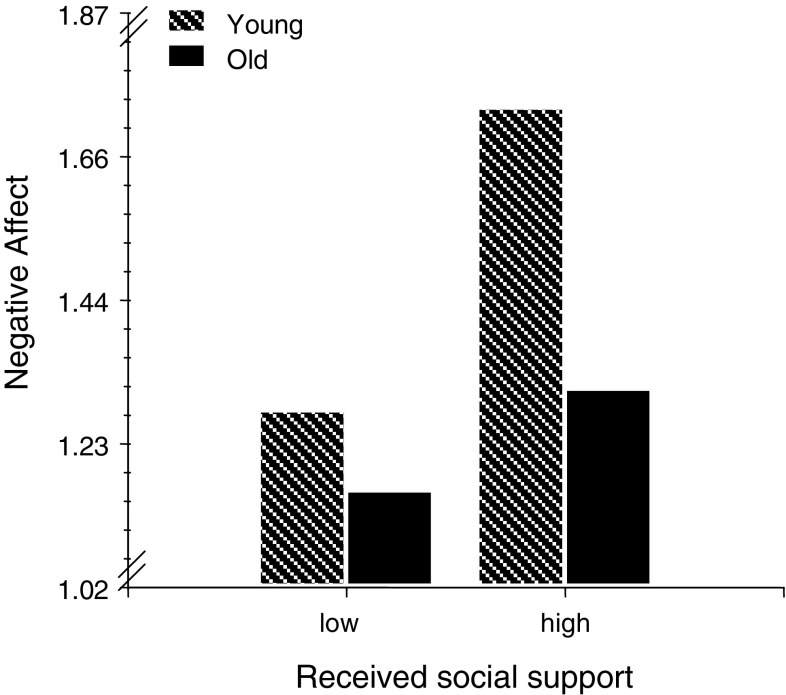

The model resulted in a non-significant effect of linear time trend on NA on the within-person level (see Table 2). A significant positive effect of received social support on NA on the within-person level emerged. Again, this association was qualified by age group. As displayed in Fig. 2, the association between received social support and NA was positive only for younger participants. Thus, on days with higher amounts of received social support especially younger individuals reported higher levels of NA. This finding was robust for potential underlying linear time trends. In terms of interindividual differences, age groups and mean level of received social support across days resulted in significant effects on the intercept of NA, indicating that higher mean levels of received social support across days and younger age were positively associated with mean initial levels of NA.

Fig. 2.

Within-person associations between social support and NA moderated by age. Note Controlled for linear time trend

Associations between previous-day predictors and following-day affect

To test whether the effects of received support on the outcomes held when controlling for previous-day affect, we also analyzed lagged effects. In the model specifying the prediction of PA on day t, random effects of the intercept of PA on day t and of the slope of previous-day PA, but not of previous-day received social support, or linear time trend were significantly different from zero. These random effects indicated interindividual differences in initial levels of PA and in the within-person associations between previous-day PA with PA on day t.

The model resulted in non-significant effects of linear time trend (see Table 3), and previous-day received social support on day t PA on the within-person level. For previous-day PA, a significant association with day t PA emerged. As no significant random effect of previous-day social support emerged, no cross-level interaction with age group was computed.

Table 3.

Lagged effects of positive/negative affect at t-1, received social support at t-1 and age on daily positive/negative affect

| b | SE | p value | Pseudo-R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: positive affect | ||||

| Between-person effects | ||||

| Age group | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Mean level of received support | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Within-person effects | ||||

| Positive affect at t − 1 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.002 | 0.04 |

| Received support at t – 1 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.81 | DNA |

| Linear time trend | −0.0002 | 0.002 | 0.94 | DNA |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||

| Age group × received support at t – 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Dependent variable: negative affect | ||||

| Between-person effects | ||||

| Age group | −0.23 | 0.08 | 0.005 | 0.13 |

| Mean level of received support | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Within-person effects | ||||

| Negative affect at t – 1 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Received support at t – 1 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Linear time trend | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.57 | DNA |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||

| Age group × received support at t − 1 | −0.17 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

Note Age group coded young = 1, old = 2; for positive affect: as no significant random effect of previous-day social support emerged, no cross-level interaction with age group could be computed

DNA does not apply/cannot be computed

In terms of interindividual differences, age group and mean level of received social support across days resulted in significant positive effects on the intercept of day t PA, indicating that interindividual differences in mean level of received social support and older age were positively associated with mean initial levels of PA.

In the model specifying the prediction of day t NA, random effects of the intercept of NA on day t, of the slope of previous-day NA, and of previous-day received social support, but not of linear time trend were significantly different from zero. These random effects indicated interindividual differences in initial levels of NA and in the within-person associations between previous-day NA and previous-day received social support with day t NA.

The model resulted in non-significant effects of linear time trend (see Table 3) on day t NA on the within-person level. Significant effects emerged for previous-day NA, and previous-day received social support. The latter was again qualified by a cross-level interaction with age group. About the same picture emerged as for the cross-level interaction on same day associations: The association between previous-day received social support and following-day NA was positive only for younger but not for older participants. Thus, days with higher amounts of received social support went along with higher amounts of NA the following day in younger individuals, whereas for older participants no such association emerged in these data. In terms of interindividual differences, age group resulted in significant negative effects on the intercept of NA, indicating that older participants reported lower mean initial levels of NA. No significant effect of mean level of received social support across days emerged.

Associations between sources of support on PA and NA

Due to the relatively few data points for sources of support, we tested the moderation of age on the association between source of support and PA and NA separately for the four different sources, resulting in eight different analyses (see Table 4). Overall, none of the sources of support was associated with PA or NA on the within-person level. Moreover, no age differences on these associations emerged.

Table 4.

Effects of sources of support and age on daily positive and negative affect

| Positive affect | Negative affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | Pseudo-R 2 | b | SE | p | Pseudo-R 2 | |

| Source of support: partner | ||||||||

| Between-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.003 | 0.18 | −0.36 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Mean level of partner | −0.24 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.52 | DNA |

| Within-person effects | ||||||||

| Source: partner | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.94 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.74 | 0.11 |

| Linear time trend | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.04 |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group × partner | −0.17 | 0.31 | 0.58 | DNA | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Source of support: family | ||||||||

| Between-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.20 | −0.31 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Mean level of family | −0.79 | 1.01 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 0.91 | 0.16 | 0.08 |

| Within-person effects | ||||||||

| Source: family | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.04 | −0.20 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.02 |

| Linear time trend | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group × family | −0.28 | 0.74 | 0.70 | DNA | −0.23 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.01 |

| Source of support: friends | ||||||||

| Between-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.19 | −0.28 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Mean level of friends | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.68 | DNA |

| Within-person effects | ||||||||

| Source: friends | −0.07 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Linear time trend | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group × friendsa | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.01 | DNA | DNA | DNA | DNA |

| Source of support: acquaintances | ||||||||

| Between-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.22 | −0.31 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Mean level of acquaintances | 1.04 | 0.52 | 0.06 | DNA | −0.36 | 0.61 | 0.56 | DNA |

| Within-person effects | ||||||||

| Source: acquaintances | −0.47 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.11 |

| Linear time trend | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Between- × within-person effects | ||||||||

| Age group × acquaintances | −0.07 | 0.63 | 0.91 | DNA | −0.42 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.01 |

Note Age group coded young = 1, old = 2

DNA does not apply/cannot be computed

aThe random effect of the slope of source of support friends when predicting NA was not significant. Therefore, a cross-level interaction with age group could not be computed

For all sources of support, except for friends as source of support when predicting NA, random effects of the intercept of PA/NA, of the slope of the respective source of support, and of the linear time trend were significantly different from zero. These random effects indicated interindividual differences in initial levels of positive/NA and in the within-person associations between affect and the different sources of support and linear time trend at the same day. Moreover, age group consistently displayed the between-level effect on the intercept of PA and NA in all eight analyses, indicating that older adults reported lower mean initial negative and higher mean initial PA than younger individuals. Finally, for the analysis predicting NA by friends as the sources of support, a significant negative within-person effect of friends occurred. Thus, on days when friends are reported being the source of emotional social support, NA is lower. The pseudo-R 2 for this effect, however, is small.

Discussion

The study provides evidence for age differences in the associations between received emotional social support and PA and NA on a day-to-day basis. On the one hand, our findings are in line with the results from recent studies showing that for younger adults received social support may be negatively associated with their well-being (c.f., Bolger et al. 2000). Besides this, our research indicated crucial age differences: Among older individuals negative effects of received social support may be no longer evident which is in line with SST assuming a social network constellation with more emotionally meaningful interaction partners (Carstensen et al. 1999). Importantly, these findings also held when controlling for previous-day NA, implying that received emotional support was not just a reaction of the social network to a higher level of NA in the younger participants (“reverse causation,” Seidman et al. 2006). Those findings have several conceptual implications for current models of socio-cognitive aging.

As one possible explanation for the age difference is based on assumptions of the SST (Carstensen et al. 1999) the selection of different sources of support by younger and older individuals, we also tested whether the different sources of support are differently related to PA and NA among younger and older adults. We assumed that for more distal network members (neighbors/colleagues), age differences would occur in that younger adults would benefit less from these sources. Our results, however, could not confirm this prediction. Although younger individuals reported overall more support from more distal network members (neighbors and colleagues), which is in line with SST (Carstensen et al. 1999) and might also reflect the difference in working status of younger and older individuals, no age differences regarding the associations between sources of support and positive/NA emerged.

There are several possible reasons for these results. First, as this was a sample recruited from the normal population to assess the associations between social support and affect in a non-stressed sample, this indeed resulted in relatively few support occasions for the whole sample throughout the 30-day diary phase. As a consequence, the number of occasions on which sources of support was indicated at all, was relatively small, which might have reduced power to detect significant effects. However, as the pseudo-R 2 indicates, the effect sizes of the interactions between age group and the different sources of support were in fact very small. Thus, the potentially reduced power does not explain the lack of substantial effects that were predicted. Second, this study is the first to test these associations on a day-to-day basis. As recent evidence indicates the results of retrospective recall, applied in cross-sectional studies, is rather different from day-to-day assessments (e.g., Schwarz 2007). Our results might not replicate previous findings (e.g., Okun and Keith 1998) because of the micro-time perspective applied in this study. Thus, replication studies are needed to further examine those possibly differential effects across different time perspectives.

With the sources of support failing to explain the age differences on the associations between received social support and positive/NA found, several alternative theoretical perspectives may account for the data: first, a potential underlying mechanism for age differences in the association between emotional support and well-being is an age-related difference in reciprocity of social exchanges (Rook 1987). Equity theory posits that a perceived imbalance of social exchanges (e.g., providing and receiving emotional support) in either direction is detrimental for an individual’s well-being (Walster et al. 1978). This is especially true for casual relationships or “new” non-romantic relationships. However, partners’ well-being in long-term and more intimate relationships (e.g., with family or close friends) is not necessarily dependent on immediate reciprocity (Antonucci and Jackson 1990). As suggested by SST, the social network of older individuals comprises less casual relationships, thus, an imbalance of exchanges might not be as problematic in terms of well-being as for younger adults with more diverse kinds of relationships in their network. However, as demonstrated by Keyes (2002), younger adults’ well-being was not affected by imbalanced exchanges of emotional support, whereas this was the case for older adults. Thus, further investigation should explicitly assess the perceived need of reciprocity depending on the sources of support to test whether this is a potential explanatory mechanism for the age differences found in this study.

Second, our findings are in line with the social input model of age differences in relationships (e.g., Fingerman et al. 2008). This model postulates that irrespective of older individuals’ motivations or emotion regulation capabilities, older adults are treated more positively by their social interaction partners and are thus more likely to experience more positive feelings with regard to their social interactions than younger people (e.g., Rook 1984).

Third, it might also be possible that for younger adults who probably need to attest their capabilities in a competitive work environment, received emotional social support might undermine their feelings of competence and self-worth more easily than for older adults. This issue needs to be addressed in future studies by assessing indicators of self-worth as a potential mechanism for the found effects.

Of conceptual importance finally were that the results concerning PA as an outcome differed from those of NA in that the previous-day PA was the only predictor for following-day affect at the within-person level. In terms of age differences, older adults seemed to report higher levels of PA over time than younger individuals. This is in line with findings suggesting that levels of PA remain stable or even increases with age (Charles et al. 2001). Moreover, older adults in our study reported lower mean levels of NA than younger adults. This again is in line with findings on amplified emotion regulation capabilities with increasing age (Gross et al. 1997).

This study has limitations some of which were already discussed. Furthermore, the use of a single-item measure of social support implies limits of reliability and validity. In terms of threats to reliability, classical test theory assumptions would predict an underestimation of effects. With regard to limitations of validity, we could replicate the results of Bolger et al. (2000) in the younger sample using different indicators of well-being (PA and NA in our study, anxiety and depression in the work by Bolger et al.). Moreover, item wording was face valid as it comprised “emotional support” and unambiguous examples (e.g., being comforted). Thus, it may be assumed that the likelihood of mixing up instrumental and emotional social support was small. Another limitation was that our focus was only on emotional social support. Further research might test whether age differences hold when other kinds of social support, such as instrumental or informational support, are considered. Moreover, our data, although longitudinal and on a day-to-day basis, are correlational in nature and thus causal inferences should not be drawn. Finally, our sample might be biased in that rather healthy and well socially supported individuals took part. Mean values of our control variables (e.g., chronic stress, depressive symptoms, and subjective health) indicate a certain bias. This study’s aim, however, was to compare the effects of support receipt in older and younger adults and at the same time replicate results of former studies on healthy young adults. Thus, an older adult group with higher multimorbidity, etc., would have made comparability between young and old participants more complicated. Yet, future studies aiming at replicating this study’s results in a more representative sample are clearly needed. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that our results are based on cohort effects and that future generations of older adults will also experience negative associations between received social support and PA and NA. Likewise, we are unable to predict if obtained results hold in old-aged individuals, confronted with dramatic changes in their health status and changes in their social networks such as death of their partners or close friends. Clearly, more research is needed to find answers to these urgent questions.

Conclusions

This research is among the first to indicate age differences in the relationships between received support and PA and NA. Moreover, findings argue against an important role of age-related differences in sources of support as possible underlying mechanism. In addition, the results rule out “reverse causation” for producing those effects. Future studies will have to further enlighten mechanisms associated with the revealed age differences in the effectiveness of received emotional social support.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all students who helped with data collection. While preparing this manuscript, the first author was partly funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP00P1_133632/1). The contribution by the third author was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science. Associations between received social support and PA and NA: Evidence for age differences from a daily-diary study

References

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The daily inventory of stressful events: an interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9(1):41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Jackson JS. The role of reciprocity in social support. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, editors. Social support: an interactional view. New York: Wiley; 1990. pp. 173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Amarel D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: experimental evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(3):458–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(6):953–961. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am Psychol. 1999;54(3):165–181. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(1):136–151. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Karmarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Miller L, Charles S. Saving the best for last: how adults treat social partners of different ages. Psychol Aging. 2008;23(2):399–409. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Carstensen LL. Motivational changes in response to blocked goals and foreshortened time: testing alternatives to socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Tsai J, Skorpen CG, Hsu AYC. Emotion and aging: experience, expression, and control. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(4):590–599. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays JC, Steffens DC, Flint EP, Bosworth HB, George LK. Does social support buffer functional decline in elderly patients with unipolar depression? Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1850–1855. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL. The exchange of emotional support with age and its relationship with emotional well-being by age. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(6):518–525. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiboer AM, Kuijer RG, Hox JJ, Schreurs KMG, Bensing JM. Receiving and providing support in couples dealing with multiple sclerosis: a diary study using an equity perspective. Pers Relatsh. 2006;13(4):485–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00131.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll N, Kienle R, Bauer K, Pffueller B, Luszczynska A. Affect and enacted support in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization: when providing is better than receiving. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1789–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll N, Rieckmann N, Kienle R. The other way around: does health predict perceived support? Anxiety Stress Coping. 2007;20(1):3–16. doi: 10.1080/10615800601032823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring age differences in the stress-buffering function of social support. Psychol Aging. 2005;20(4):714–717. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, DeLeeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. London: SAGE; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR. Regulation of social relationships in later adulthood. J Gerontol B. 2001;56(6):321–326. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.P321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt MJ, Weber RA, Guacci N. Convoys of social support: an intergenerational analysis. Psychol Aging. 1993;8(3):323–326. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.8.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LW, Liang J. Social exchanges and subjective well-being among older Chinese: does age make a difference? Psychol Aging. 2007;22(2):386–391. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Stephens MA, Druley JA, Wojno WC. Negative reactions to received spousal care: predictors and consequences of miscarried support. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):167–176. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.21.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Kaniasty K. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: a test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(3):498–511. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun MA, Keith VM. Effects of positive and negative social exchanges with various sources on depressive symptoms in younger and older adults. J Gerontol B. 1998;53(1):P4–20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53B.1.P4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models. Application and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. The negative side of social interaction: impact on psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46(5):1097–1108. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Reciprocity of social-exchange and social satisfaction among older women. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(1):145–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Pierce GR, Sarason BR. Social support and interactional processes—a triadic hypothesis. J Soc Pers Relat. 1990;7(4):495–506. doi: 10.1177/0265407590074006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz U, Schwarzer R. Social support in coping with illness: the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS) Diagnostica. 2003;49(2):73–82. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Retrospective and concurrent self-reports: the rationale for real-time data capture. In: Stone AA, Shiffman S, Atienza AA, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture self-reports in health research. Oxford: University Press; 2007. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Knoll N. Social support. In: Kaptein A, Vedhara K, Weinman J, editors. Health psychology. Oxford: Blackwell; 2010. pp. 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman G, Shrout PE, Bolger N. Why is enacted social support associated with increased distress? Using simulation to test two possible sources of spuriousness. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32(1):52–65. doi: 10.1177/0146167205279582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Walster G, Berscheid E. Equity. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]