Abstract

Data from European countries participating in the Generations and Gender Surveys showed that mean loneliness scores of older adults are higher in Eastern than in Western European countries. Although co-residence is considered as one of the fundamental types of social integration, and although co-residence is more common in Eastern Europe, the mean loneliness scores of older co-resident adults in Eastern Europe are still very high. This article investigates mechanisms behind the puzzling between-country differences in social integration and loneliness. Firstly, the theoretical framework of loneliness is discussed starting from the individual’s perspective using the deficit and the cognitive discrepancy approach and taking into account older adults’ deprived living conditions. Secondly, mechanisms at the societal level are investigated: cultural norms, the demographical composition and differences in societal wealth and welfare. It is argued that an integrated theoretical model, as developed in this article, combining individual and societal level elements, is most relevant for understanding the puzzling reality around social integration and loneliness in country-comparative research. An illustration of the interplay of individual and societal factors in the emergence of loneliness is presented.

Keywords: Social integration, Loneliness, Co-residence, Individual perspective, Societal perspective, Theoretical framework

Introduction

Focusing on differences in the mean level of loneliness of older people in Eastern and Western European societies, we would like to contribute to the theoretical framework of loneliness in cross-cultural research. As loneliness belongs to those indicators which characterize the liveability of a society (i.e. a good society should have a low prevalence of loneliness), we will start with normative statements concerning societal cohesion and integration. In a classic volume on old age, Rosow (1967) stated that ‘the most significant problems of older people (…) are intrinsically social. The basic issue is that of their social integration’ (p. 8). This conviction can be found in political declarations as well. In the León Ministerial Declaration ‘A society for all ages: Challenges and opportunities’ it is stated that ‘We are committed to promoting intergenerational solidarity as one of the important pillars of social cohesion…’ (Stuckelberger and Vikat 2007, p. 3). In addition to research and policies addressing the health and wealth aspects of the ageing population, more and more attention is being devoted to the social integration of older adults. If we apply these normative statements to loneliness, it could be inferred that the social integration of older people in many cases leads to low levels of loneliness. However, we would like to challenge this straightforward assumption with the following empirical observation.

Turning the statement just mentioned into an empirically testable hypothesis, it could be assumed that societies with strong social integration will have a low prevalence of lonely individuals (and vice versa). We can test this very simple hypothesis by comparing Western and Eastern European countries. Although filial norms are higher in Eastern European countries as compared to Western European countries, the incidence of loneliness among the population aged 60 and above is higher in (most) Eastern than in (most) Western European countries. Compare the answers on a direct question about loneliness: 6.3 % of the Danish respondents proved to be lonely, 8.3 % of the Netherlands’ respondents, 8.5 % of the German respondents, 13.4 % of the Belgian respondents and 17.8 % of the French respondents, as compared to 15.6 % of the Czech, and 20.0 % of the Polish respondents (Fokkema et al. 2012).

These countries differ significantly in providing older adults with the possibilities of social integration via co-residence. While in Western countries only a minority of older adults (4–5 %) co-resides with children aged 25 or above, the incidence of co-residence is more than 20 % in Bulgaria and Russia, and more than 50 % in Georgia (De Jong Gierveld 2009). This stronger social integration in Eastern Europe does not lead to a lower intensity of loneliness in these countries, however. In Table 1, the mean scores of older adults on the 6-item De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale (0, not lonely—6, intensely lonely) are shown, separately for adults living with or without partners, either in independent households or in co-residence with their children, controlled for age of older adults (De Jong Gierveld, Dykstra, and Schenk, in press).

Table 1.

Mean loneliness scores (and standard deviations) of parents aged 60–79 years by current partner status, living arrangement and region (Eastern Europe: Russian Republic, Bulgaria, Georgia; Western Europe: Germany and France

| Partner status | ||

|---|---|---|

| No partner | Plus partner | |

| Eastern Europe, adults in co-residence | 3.42 (1.85) | 2.88 (1.78) |

| Eastern Europe, adults in independent household | 3.60 (1.97) | 2.78 (1.81) |

| Western Europe, adults in independent households | 2.00 (1.83) | 1.36 (1.56) |

Source Generations and gender surveys, wave 1

Table 1 shows that mean loneliness scores are higher in Eastern European countries, both for those older people living in independent households and for those in co-residence, as compared to Western Europe. (Note, that co-residence in Western Europe is not included in Table 1, because of the low incidence of co-residence in Western Europe). If co-residence with one’s own children is one of the fundamental types of social integration, it should affect the intensity of loneliness. Only the existence of a partner, however, has a consistent effect on the intensity of loneliness, while co-residence has not. Hence, there might be other factors contributing to the higher levels of loneliness in Eastern Europe which lead to mean loneliness scores above the cut-off score of 2 on the loneliness continuum.

Tesch-Römer and von Kondratowitz (2006) made a plea for further theoretical investigation of whether differences or similarities in ageing processes can be expected across countries via the identification of societal and cultural frames and mechanisms at the macro and individual level. We are following up on this plea and wish to investigate the mechanisms behind between-country differences in well-being and social integration, to go beyond norms and attitudes and to take on board the broader social context.

Starting with puzzling empirical differences in loneliness between Eastern and Western European societies, we will first discuss the conceptual framework of loneliness in an individual perspective (“The individual perspective: conceptual framework of loneliness” section). In this section, we will show that individual approaches do not sufficiently explain East–West differences in loneliness. The societal level will be considered in the next section (“The societal perspective: the contexts of loneliness” section), taking into account societal welfare, demographical composition, and cultural norms. Finally, we will present an integrated model and discuss the interaction between the societal and individual level in respect to loneliness levels in Eastern and Western European societies, hoping to render some theoretical harvest (“Interplay of individual and societal factors in the emergence of loneliness” section).

The individual perspective: conceptual framework of loneliness

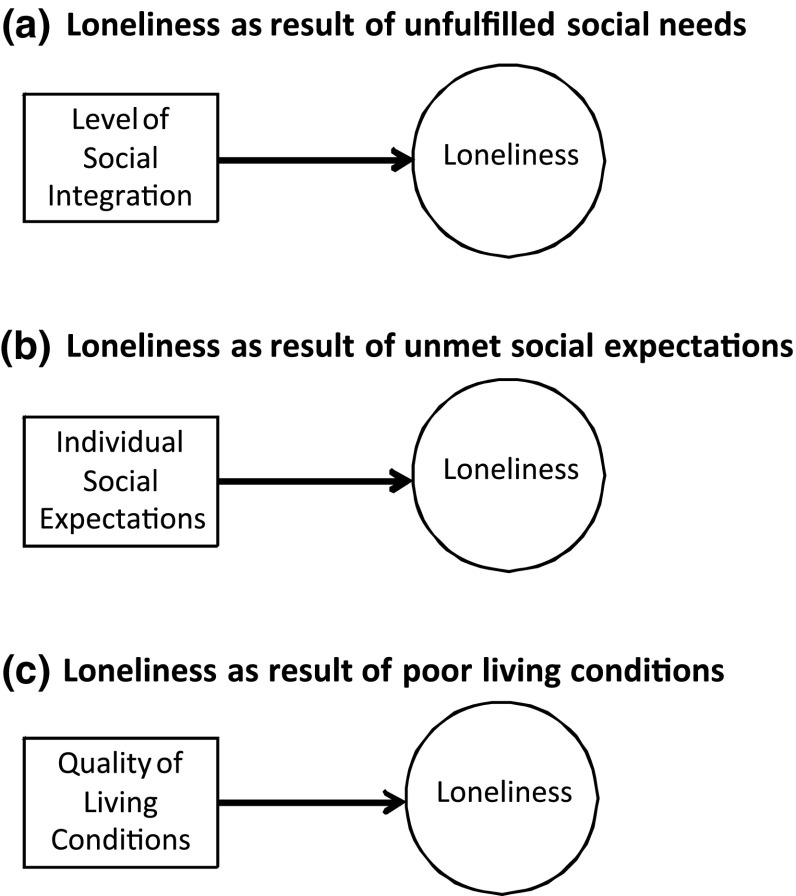

Loneliness is a genuinely social experience. An individual is lonely because other people are lacking. Loneliness might be the bitterly felt the absence of an intimate partner (emotional loneliness) or the sadness of being unnoticed or rejected by others (social loneliness). Despite its social nature, loneliness is an individual reaction, mixing cognitive evaluations and emotional response. Peplau and Perlman (1982) described in their seminal work a variety of theoretical conceptual approaches to loneliness. We will concentrate on three of these (De Jong Gierveld et al. 2006): (a) Loneliness as a result of unfulfilled social needs, (b) loneliness as a result of unmet social expectations, and (c) loneliness as a result of poor living conditions (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Three theoretical conceptual approaches concerning the emergence of loneliness

Loneliness as a result of unfulfilled social needs

Social motives are built into human nature: Humans are ‘social animals’ and need contact and exchange with other people, both kin and non-kin, both strong and weak ties (Cacioppo et al. 2006a, b). Consequently, loneliness results if social needs are not fulfilled because social contacts are lacking (see Fig. 1a). One might call this the ‘deficit approach’ of loneliness. In a similar vein, Weiss (1973) suggests two forms of loneliness: Emotional loneliness results from the absence of an intimate partner, while social loneliness is due to lacking social integration into a network of family members, friends and acquaintances. Hence, not only the structure of the social network (size and type of relationships) but also its quality (existence of emotionally satisfying and secure ties) are relevant for the emergence of loneliness.

Empirical research has shown that social involvement in family and employment fulfils the basic social needs of individuals. Marriage may provide people with feelings of intimacy and emotional connectedness (De Jong Gierveld et al. 2009). Married people have additional possibilities, through the spouse’s and children’s activities, to maintain a larger and varied network of social and emotional bonds with kin and non-kin network members as compared to those who live alone (Dykstra and De Jong Gierveld 2004; Pinquart and Sörensen 2001).

People’s social needs may change with increasing age. According to the socio-emotional selectivity theory, the need for information and knowledge is predominant in adolescence and young adulthood, while the need for emotion regulation and the need for familiar, intimate relations increase in importance in later adulthood (Charles and Carstensen 2007). It is taken for granted that the possibilities for integration are better for those involved in household types including family members of different generations: the daily contacts between grandparents, children and grandchildren are expected to lead to social integration and feelings of being embedded (Tomassini et al. 2004). Research has shown that those living in one-person households are predominantly at risk of social isolation and loneliness (Dykstra and De Jong Gierveld 2004; Victor et al. 2003). Moreover, it has been shown that changes in social integration, e.g. losing a partner and reduced social activities account for changes in loneliness over time (Van Aartsen and Jylhä 2011).

Does the ‘deficit hypothesis’ (loneliness results from unfulfilled social needs) help to explain the loneliness differences between Eastern and Western European societies? The deficit hypothesis implicitly assumes universality (all human beings have social needs). In order to explain societal differences, one could assume that differences in social needs are distributed differently across societies (e.g. because the prevalence of functional limitations differ between societies). In addition, one could assume that social expectations may differ between cultures and societies. Hence, we would like to turn to an approach which focuses on the role of social expectations that might be useful to explain differences between Eastern and Western European Societies.

Loneliness as result of unmet social expectations

In contrast to the ‘deficit hypothesis’, the cognitive discrepancy approach focuses on expectations regarding social relations. A person evaluates her or his relationships in the light of her or his personal standards for an optimal network of social contact. Not only the existence (or absence) of persons in the network are relevant for the emergence of loneliness but also the discrepancy between people’s expectations and (perceived) reality. A leading definition of loneliness was formulated by Perlman and Peplau (1981, p. 31): ‘The unpleasant experience that occurs when a person’s network of social relations is deficient in some important way, either quantitatively or qualitatively’. Hence, it seems wise to take into consideration people’s social preferences and standards (Dykstra and De Jong Gierveld 1994). If the social network does not meet a person’s standards in terms of quantity and quality, loneliness results (see Fig. 1b). The cognitive approach not only considers standards but also the cognitive consequences of loneliness. Loneliness may lead a person becoming highly sensitive to (perceived) social threats. As a consequence, lonely individuals are more likely to expect negative social exchange and also behave in a way which leads more often to unsuccessful social interactions, and hence social isolation (Cacioppo and Hawkley 2009).

There is rich evidence for the ‘cognitive hypothesis’ of loneliness. Discrepancy between expectations regarding relationships and the status of a relationship predicts loneliness in divorced and married adults. Divorcees who attach great importance to having a partner and people whose marriages are conflict-ridden tend to have high levels of emotional loneliness (Dykstra and Fokkema 2007). With respect to ageing processes, the socio-emotional selectivity theory would assume expectations regarding intimate relations not to change. Hence, cognitive standards regarding the quality of social relations should be relevant in old age as well. There is also empirical evidence for the “cognitive hypothesis” for older adults: Although the size of a social network is related to feelings of isolation, preferences and perceived deficiencies of friendships are strong predictors of social loneliness (Heylen 2010).

With respect to the comparison between Eastern and Western European societies, the cognitive approach is better suited to account for differential levels of loneliness in different societies. Individual expectations are formed in the exchange with the social and cultural context of a person. Hence, cultural standards might be relevant in explaining differences in individual social expectations (we will come back to this argument later).

Loneliness as result of poor living conditions

Finally, it has been shown over and again that poor living conditions may explain why some people consider themselves lonely. Loneliness is related to socio-demographic characteristics such as health status (ill people feel lonelier than healthy people), income (poorer people feel lonelier than wealthier people), and neighbourhood (people living in deprived neighbourhoods feel lonelier than people living in well-off neighbourhoods; see De Jong Gierveld et al. 2006; Halleröd 2009; Pinquart and Sörensen 2001; Scharf and De Jong Gierveld 2008; Scharf et al. 2005).

Quite often, these more distal predictors are linked to proximal factors like a small number of friends or poor relationship quality. Deprived living conditions may endanger the size or functioning of the social network of a person; an inadequate social network or lack of social support may lead to the negative feeling of being isolated (see Fig. 1c). It is well documented that on average financial hardship is associated with greater psychological distress and more interpersonal conflicts. Negative social interactions may unfold their effect on subjective well-being when financial resources are low (Krause et al. 2008). Stress processes are a key element in this context and stress responses affect well-being in later life and can accelerate the ageing process (Ferraro and Shippee 2009).When there are too few resources to go around, it is not difficult to see why inter-personal conflicts might arise, resulting in not getting help when help is needed (Hobfoll 1989). Given that health often deteriorates in old age (Wurm et al. 2010), this pathway may be of special importance in old age.

However, there might be another nexus between poor living conditions and loneliness. Low social status and especially financial problems have an adverse effect on health and subjective well-being of older people (George 1992, 2006). Loneliness is part of the cognitive-emotional evaluation system of the individual. While different in origin, feelings of loneliness are related to indicators of subjective well-being like depressive symptoms (Cacioppo et al. 2006). Hence, poor living conditions may lead to a combination of negative experiences and also give rise to loneliness.

Looking again at the societal differences between Eastern- and Western-European societies, one should take into account the differential levels (and distributions) of individual wealth within the different countries. If poor living conditions influence both social integration and subjective well-being, different levels in average income and wealth might explain different levels of loneliness in European societies.

Social needs, social expectations, living conditions and loneliness

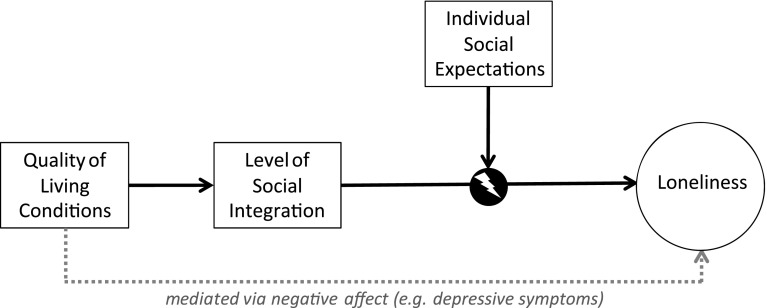

Before we more thoroughly discuss the impact of societal factors in the emergence of loneliness, we would like to elaborate the relationship between the deficit approach (unfulfilled social needs lead to loneliness), the cognitive approach (unmet social expectations lead to loneliness) and the living situation approach (poor living conditions lead to negative emotional experiences and, hence, also to loneliness). Figure 2 illustrates the connections between social integration, individual social expectations and living conditions in the emergence of loneliness.

Fig. 2.

The interaction between social integration, individual social expectations and living conditions in the emergence of loneliness

The level of social integration is a necessary condition for the fulfilment of social needs and, hence, the prevention of loneliness. However, individual preferences and expectations are highly important for the evaluation of the relationship in a person’s network. Hence, social needs and social expectations interact with each other. Finally, individuals and their social partners are embedded in material and societal contexts. These contexts influence social needs and the quality of social relations. However, the impact of poor living conditions on loneliness might also be mediated by negative affect and, especially, depressive symptoms. Ageing has an impact on the components of this loneliness model. Social integration may become more fragile (because the person experiences the loss of partner and friends) and social expectations change with advancing age (ties to familiar persons may gain in importance). Quite often, health and dependency—highly important aspects of the individual living situation in old age—pose challenges for older people and may change the need for social support.

The societal perspective: the contexts of loneliness

Individuals and their social networks are embedded in larger societal and cultural contexts. These contexts influence individual social expectations, create opportunities for social integration and shape the quality of individual living situations. Larger societal and cultural contexts, like culture, social policy, socio-economic factors and social change, can be seen as ‘upstream forces’ which condition social network structures (Berkman et al. 2000, p. 847). In the following, we will concentrate on three interrelated societal and cultural contexts, namely (a) cultural norms for exchange and solidarity, (b) the demographical composition of a population and (c) societal wealth and welfare, including the support systems of the welfare state (see for a similar approach: Glaser et al. 2004). We hasten to add that this discussion of demographical, cultural and societal factors is in no way meant to be comprehensive. Other aspects could be added as well (e.g. the complexity of a society, rigidness of cultural norms, etc.). We will give some comparative examples for the large variation between countries, concentrating on Eastern and Western European societies.

Cultural norms as reference system for individual expectations

Cultural norms regarding social activities, exchange and solidarity play an important role in social integration. One of the most basic social norms concerns mutual help within families (family solidarity). Filial norms are the basis for support from adult children to their ageing parents (Lowenstein and Daatland 2006). Hence, these norms are an important basis for social integration of older people. There are cultural differences, however. Support for filial norms has a East–West dimension in Europe: These norms are strong in Eastern Europe and weaker in countries in Western Europe.

Co-residence is considered to be of crucial importance to support ageing parents and their general well-being. This is especially so in Eastern European countries as compared to Western European countries: 70 % of the Russian population aged 18–79 years, 80 % of the Bulgarian population and 90 % of the Georgian population agreed with the statement ‘Children should have their parents to live with them when parents can no longer look after themselves’. This is in sharp contrast to the norms in France and Germany with 42 and 44 % agreeing with the statement, respectively (De Jong Gierveld 2009). Saraceno and Keck (2010) investigated the public efforts in providing care provisions (encompassing a minimum pension provision, residential and home based care) to the population aged 65 and over in 27 European countries. They concluded that Eastern European countries such as Hungary, Poland and Bulgaria are to be characterised as countries with very low levels of welfare state support and consequently high levels of family support: ‘familialism by default’; in contrast Western European countries such as Denmark, France, Belgium and the Netherlands are to be characterised as‘de-familialisation’ countries. Different systems of cultural norms are related to varying forms of social integration of older people.

Cultural norms may also act as a reference system for individual expectations, moderating the link between social expectations and loneliness. This can be illustrated by the case of a widowed older person. In a culture where filial norms are strong, the widowed older person might be expected to live with her or his children—and might be satisfied with such a solution. In a culture which values autonomy and self reliance, the same situation might be evaluated differently: The older person might perceive living in a child’s household as a burden to the child—hence, feel lonely.

Demographical composition as an opportunity structure for social integration

Populations can be characterized, among other factors, by the distribution of gender, age and family status. The main aspects of demographical composition—birth, migration, ageing and death—are the background factors for social integration and influence the support available by family members. It has to be kept in mind that the demographical composition of populations is constantly changing (Gaymu et al. 2008). Trends in partnering and (re)marriage, age differences between partners and levels of fertility influence the composition of families and the availability of support by different members of the family (Glaser et al. 2004). The distributions of partner and parent status are two of the key characteristics of demographical composition.

For social integration in old age, partner and parent status are of high importance (Katz et al. 2005). Sharing life with a partner is one of the basic preconditions of social integration. Moreover, for people who have lived in a partnership throughout their adult life, the loss of a partner is a critical life event and may change the extent of social integration. European societies differ in the overall rates of partner status, parent status and types of living arrangements. For instance, the proportion of married people aged 75 years and above differs substantially between European countries. In 2001, the proportion of married women in this age group varied between 18 % (Eastern Europe, Czech Republic) and 26 % (Western Europe, France), while the differences for men ranged from 62 % in England and Wales to 69 % in the Czech Republic. In the next decade, this situation will change (especially for women): The proportion of widowed older people will become smaller, and the proportions of both married and divorced persons will increase (Kalogirou and Murphy 2006). Living together with a partner is quite often associated with lower prevalence of loneliness (Sundström et al. 2009).

The demographical composition of a population not only shapes the opportunities for social integration but also moderates individual expectations (Dykstra 2009). The composition of a population might mitigate (or intensify) individual social expectations. Hence, we would hypothesize that similar individual situations have different consequences in populations with different demographical compositions. An example: A person without children living in a high fertility society might feel much lonelier than a person living in a society where childlessness has a higher probability.

Societal welfare as an enabling factor for quality of living situations

Finally, we would like to stress that societal wealth and welfare are highly important for social integration of all members of a society and, hence, also for older persons. In poor societies family ties are highly important for mastering the daily challenges of providing the means of livelihood and therefore these ties are under constant pressure. Hence, an overall higher level of wealth of a society (and relatively equal distribution of wealth) may give more people the chance to construct their social relations without too much interference from basic livelihood concerns.

European countries vary widely in societal wealth or strength of welfare state support. A variety of macro-indicators might be used to describe societal wealth, such as the gross domestic product, GDP. The GDP refers to the market value of all goods and services produced within a country in a given period. GDP per capita is often considered an indicator of a country’s standard of living. Recent data indicate sharp differences in this respect between the regions and countries. Starting in the beginning of the 1990s, the Eastern European region has gone through a significant geo-political reorganization, accompanied by a general state of socio-political changes. The connected economic transformations had the most profound impact, both at the country- and family level. Major problems encompass a high level of unemployment and poverty in the region, going together with high inflation and decreasing wages. One has to take these developments into consideration in discussing social integration and loneliness. Additionally, we will concentrate on the rate of relative poverty (here defined as equivalised disposable income below 60 % of the national median after social transfers) and the proportion of people living in overcrowded households (here defined as a household which does not have at least one room for the household, one room per couple in the household, one room for each single person aged 18 or more, and depending on age and gender, single or shared rooms for adolescents and children).

In 2009, the proportion of older people over the age of 65 years in relative poverty was about 18 % in Europe (27 member states), but varies widely between European countries. In some countries of Western Europe, the rate of older people living in relative poverty is low (Luxembourg 5 %, Netherlands 8 %) or around the EU mean (Germany 15 %). In Eastern European countries, however, the relative poverty rates of older people are much higher (Estonia 34 %, Bulgaria 39 %; SILC 2010). Similarly, the rate of overcrowded households (households which do not have a minimum number of rooms for the number of people living together) is much higher in Eastern European countries exceeding 40 % or even 50 % of the total population. In contrast, the overcrowding rate in Western European countries is mostly below or around 5 % (Eurostat 2010, p. 331). Clearly, in poorer countries more people live in socio-economic conditions which may lead to interpersonal conflicts, stress and, consequently, loneliness.

However, in addition to a direct pathway connecting socio-economic country level inequalities and people’s well-being via individual socio-economic resources, it makes sense to assume an indirect pathway by which contextual level socio-economic inequalities—poverty and social exclusion from institutional resources—reduce trust and increase people’s perceptions of relative deprivation, leading to negative outcomes (O’Rand 2001, 2006). Such an indirect pathway can be illustrated by a study which analysed the impact of individual and context factors on loneliness (Deeg and Thomése 2005). Both low income and poor socio-economic status of the neighbourhood predicted individual loneliness. Again, in addition to a direct pathway from neighbourhood characteristics (e.g. constant neighbourhood turnover predicting loneliness), there was also a pathway via individual perceptions (e.g. housing and neighbourhood satisfaction predicting loneliness). Hence, societal wealth and welfare might moderate the impact of poor living conditions on the emergence of loneliness.

Interplay of individual and societal factors in the emergence of loneliness

This brief discussion of cultural norms, demographical composition and societal welfare has resulted in a rather complex picture. Differences between Western and Eastern European countries are discernible in some of these domains, but it is unclear whether there is a concordant impact in all domains. For instance, there are stronger familialistic norms in Eastern European countries (which might be positive for the social integration of older people); but, at the same time, the risk of poverty is higher in Eastern European countries (which might make the social integration of older people more difficult). Additionally, a strong family ideology might overburden a family when material means are scarce. Taking these considerations into account, it seems difficult to infer the extent of loneliness in a country from varying demographical, cultural and welfare conditions. Hence, in the remaining part of the paper, we will present a model and give some empirical illustrations for the interaction between societal and individual factors on the emergence of loneliness.

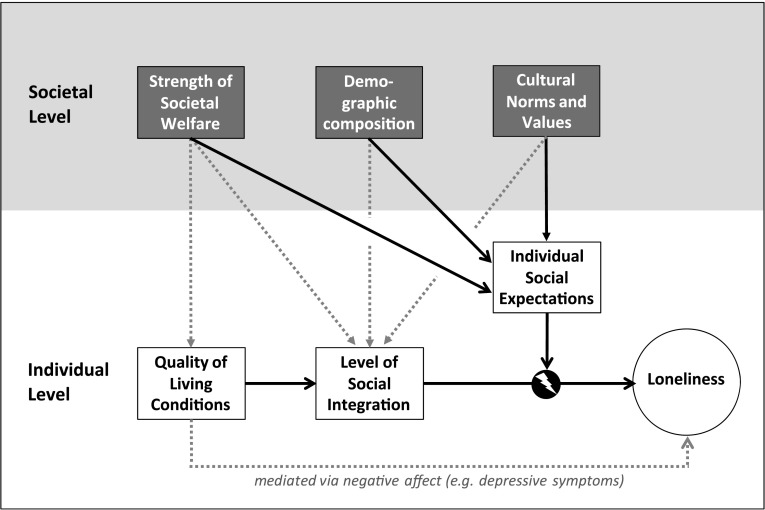

An integrative model

The integrative model we propose is graphically depicted in Fig. 3. We start out with the individual level model on the emergence of loneliness we have described above (lower part of Fig. 3). Additionally, we propose three context factors on a societal level (upper part of Fig. 3): Societal wealth and welfare, demographical composition and cultural norms and values. These contexts exert main effects on individual factors (dotted grey arrows). Marginal societal wealth increases the risk that older persons live in poverty and, hence, are socially less integrated as compared to societies with a higher level of welfare. A high rate of marriage increases the likelihood of household and family support. Finally, familialistic norms in a culture increase the probability for older persons to be in contact and to exchange support with their families. Please note that we have outlined macro- (societal level) and micro-level (the individual and the immediate ties of this person). Highly important in the context of social integration and loneliness are structures and processes on the meso-level (e.g. the interplay between family ties and private networks of neighbours and friends). In order to reduce the complexity, we have not explicitly shown these meso-level structures and processes in the model.

Fig. 3.

Individual and societal factors in the emergence of loneliness

We propose that there is an interaction between context level and individual level factors (see Fig. 3, solid black lines). The crucial arena for these interactions is individual social expectation. Valuing intergenerational support has a different meaning in a context where this value is a basic cultural tenet as compared to a context where intergenerational support is seen as optional. Living in a population with high intergenerational co-residence raises the individual preference for living in a child’s household. Living in a richer country will lower preferences for kin support. In the final part of this paper, we would like to illustrate the interplay of individual and societal factors in the emergence of loneliness.

Illustrations for the interplay of individual and societal factors in the emergence of loneliness

As argued above, the individual level of social integration is protective against loneliness when the quantity and quality of social ties, activities, and support are judged to be sufficient by the individual. In a familialistic culture, this would be the case if family ties are strong and intergenerational support high. The alleviating effects of social integration via intergenerational family support may collapse, however, when individual living circumstances are inadequate, societal wealth marginal, and welfare state support weak. In this case, we assume that the existence of close family members and the strong normative demand to mutual support may even aggravate loneliness (studies showing the relationship between low socio-economic status, family conflicts and reduced well-being can be found in family research on the family stress model and in health research, e.g. Aytac and Rankin 2009; Barrett and Turner 2005; Choi and Marks 2011). In the remaining part of this paper, we would like to illustrate the strain on family solidarity from economic disadvantage more concretely (a) for societies with a very low societal wealth (as indicated by a low GDP), (b) for societies with a low to moderate societal wealth (as indicated by a low to moderate GDP) and (c) for societies with a moderate to high societal wealth (as indicated by a moderate to high GDP).

A socio-economic country context characterized by low GDP and low household incomes makes it difficult to make ends meet and forces older and younger generations to support one another: Daughters, for example, will take care of cleaning the living quarters of their ageing parent(s) and provide other types of care and support—parents who presumably co-reside with their adult children. Attitudes will be in line with this situation of instrumental reciprocal support, that is: oriented towards strong filial obligations. Adherence to these norms and behaviour in line with these norms offer an opportunity for society at large to guarantee an optimal level of personal well-being including for the oldest age groups. When the level of standards and expected behaviour is higher than the level of exchange of support that can be fulfilled by family members, both the support providers and receivers are at risk of stress responses and decreasing levels of well-being. This is the more so for women, who are confronted with the double burden of (compulsory) participation in the workforce and fulfilling their ‘natural’ roles in care for the children and older parents (in-law) and doing all the cooking and cleaning (Haukanes 2001).

A socio-economic country context characterized by a somewhat higher, but moderate level, of GDP and household incomes (of a substantial proportion of the population) that allows people to make ends meet offers more opportunities for a variety of familial resource mobilization. Older adults might be inclined to live independently for as long as possible albeit in the direct vicinity of their offspring. In this situation, for example, daughters will take care of cleaning the living quarters of their ageing parent(s), both for parents who are co-residing and for those not co-residing. Mainstream standards and values might be still underlining filial responsibilities, but up to a level that allows more personal freedom to all generations. Examples of this situation are to be found in old Saxon Romanian villages (such as Viscri/Weisskirch; Van der Haegen and Niedermaier 1997) where the farmer’s main house and a cottage for the older parents are built next to one another on the same family ground. In doing so, the older couple is provided with a certain level of independence and the guarantee of familial support when care is needed.

A socio-economic context characterized by a substantial higher GDP and a government that can financially or otherwise support families to a certain extent offers opportunities with still more options for making personal support arrangements on the one hand and an individual life style, personal decision making and relative independence for as long as possible on the other. Arrangements with different types of inter-linkages between family care, market care, state provisions and volunteer work are nowadays recognizable within and between European countries (Lyon and Glucksmann 2008). In this situation, for example, daughters will be in frequent contact with their older parent(s), may be sometimes cleaning their living quarters, but may be more often engaged in emotional support exchanges. Children might employ (round-the-clock) paid care (by foreign women) for their ageing parent(s), enabling the dependent older adult and the family members to continue living in his or her own home, thus fulfilling aspirations to remain in a ‘natural’ family environment. In doing so, children change into the role of care managers, being in charge of all aspects of the life of the care recipient, including running the house, the finances and the (foreign) care worker (Ayalon 2009). Prevailing standards and attitudes that fit this situation are less oriented towards filial obligations as such—highlighting the need for instrumental support—but more directed towards a broader field of exchanging instrumental and emotional support between older people and their adult children. When potential support providers fail to adhere to standards, both support providers and receivers might be at risk of stress responses and decreasing levels of well-being. The mechanisms mentioned here, based on the cumulative inequality theory and the relative deprivation frame work, offer possibilities to interpret and explain differences in the ageing processes across countries, taking into account both social and cultural frames and individual level conditions.

Outlook: changing lives in changing societies

In this paper, we started out with a puzzling empirical result: Comparing Western and Eastern European countries we saw that for older adults, both social integration and loneliness are higher in Eastern than in Western societies. In order to solve this puzzle and to cultivate theoretical conceptions of comparative ageing research, we developed a conceptual framework of loneliness, considering demographical, cultural and societal factors and their interaction with individual level determinants of loneliness. We hope that our tentative theoretical model might help to stimulate further empirical research and open possibilities to broaden the model to other regions of Europe. Comparing Northern and Southern European countries, Sundström and colleagues find that the prevalence of loneliness is higher in the Mediterranean countries than in Northern Europe (Sundström et al. 2009)—and point out that this is a puzzling finding because ‘this is at variance with our most simplified and cherished views of “Anomie” in Nordic countries and “Gemeinschaft” in Southern societies’. We believe that our model might be useful in this context. The interaction between cultural values and individual social expectations might lead to greater individual expectations in Southern European countries, and hence a higher level of loneliness despite good social integration of older people in these societies.

We would like to finish our discussion with a reference to the relevance of social change for the emergence of loneliness (cf. the theoretical linkage between social change and individual development by Pinquart and Silbereisen 2004). In analysing loneliness in a comparative perspective, we have to pay close attention to societies undergoing rapid change. During the last two decades, the Eastern European countries have experienced rapid societal changes with deep consequences for the social integration in the context of family, household type, neighbourhood and the broader social environment. These negative economic and social changes in the countries of Eastern Europe have resulted in increased income inequalities, poverty, unhealthy behaviour, psychological stress and decreased life expectancy (Petrov 2007). As far as the position of older people is concerned, the intergenerational relationships changed fundamentally. After the economic crisis of the 1990s pension schemes in many Eastern European deteriorated which makes it difficult for the majority of older adults to pay everyday expenses (e.g. Tchernina and Tchernin 2002). Many of the older adults now have to rely on the financial help of children, who themselves are confronted with very high levels of unemployment, decreasing income levels and increasing costs of living. Changes in societal wealth and the strength of the welfare state, alterations in the demographical composition of a population and shifts in cultural norms and values are the changing contexts for individual living conditions, social integration and subjective perceptions and aspirations of social ties. A theoretical perspective combining societal and individual factors in the emergence of loneliness might help to capture also the relation between social change and individual development.

References

- Ayalon L. Family and family-like interactions in households with round-the-clock paid foreign carers in Israel. Ageing Soc. 2009;29(5):671–686. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aytac IA, Rankin BH. Economic crisis and marital problems in Turkey: testing the family stress model. J Marriage Fam. 2009;71(3):756–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00631.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, Turner RJ. Family structure and mental health: the mediating effects of socioeconomic status, family process, and social stress. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(2):156–169. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(10):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, Burleson M, Berntson GG, Nouriani B, et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J Res Pers. 2006;40(6):1054–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL (2007) Emotion regulation and aging. In Gross JJ (ed) Handbook of emotion regulation. Guilford Press, New York

- Choi H, Marks NF. Socioeconomic status, marital status continuity and change, marital conflict, and mortality. J Aging Health. 2011;23(4):714–742. doi: 10.1177/0898264310393339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J (2009) Living arrangements, family bonds and the regional context affecting social integration of older adults in Europe. In: How generations and gender shape demographic change: towards policies based on better knowledge. United Nations, Geneva, pp 107–126

- De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T, Dykstra PA. Loneliness and social isolation. In: Vangelisti A, Perlman D, editors. The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J, Broese van Groenou MI, Hoogendoorn AW, Smit JH. Quality of marriages in later life and emotional and social loneliness. J Gerontol B. 2009;64B(4):497–506. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA, Schenk N (in press) Living arrangements, intergenerational support types and older adult loneliness in Eastern and Western Europe. Demogr Res

- Deeg DJH, Thomése FGC. Discrepancies between personal income and neighbourhood status: effects on physical and mental health. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:98–108. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA. Older adult loneliness: myths and realities. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6:91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, De Jong Gierveld J. The theory of mental incongruity, with a specific application to loneliness among widowed men and women. In: Erber R, Gilmour R, editors. Theoretical frameworks in personal relationships. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, De Jong Gierveld J. Gender and marital-history differences in emotional and social loneliness among Dutch older adults. Can J Aging. 2004;23(2):141–155. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, Fokkema T. Social and emotional loneliness among divorced and married men and women: comparing the deficit and cognitive perspectives. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;29(1):1–12. doi: 10.1080/01973530701330843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (2010) Europe in figures. Eurostat yearbook 2010. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

- Ferraro KF, Shippee TP. Aging and cumulative inequality: how does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):333–343. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema T, De Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA. Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J Psychol. 2012;146(1–2):201–228. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.631612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaymu JL, Ekamper P, Beets G (2008) Future trends in health and marital status: effects on the structure of living arrangements of older Europeans in 2030. Eur J Ageing. doi:10.1007/s10433-008-0072-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- George LK. Economic status and subjective well-being: a review of the literature and an agenda for future research. In: Cutler NE, Gregg DW, Lawton MP, editors. Aging, money, and life satisfaction: aspects of financial gerontology. New York: Springer Publishing; 1992. pp. 69–99. [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Perceived quality of life. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. pp. 320–336. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser K, Tomassini C, Grundy E. Revisiting convergence and divergence: support for older people in Europe. Eur J Ageing. 2004;1(1):64–72. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halleröd B. Ill, worried or worried sick? Inter-relationships among indicators of wellbeing among older people in Sweden. Ageing Soc. 2009;29:563–584. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haukanes H. Anthropological debates on gender and the post-communist transformation. Nordic J Feminist Gender Res. 2001;9(1):5–20. doi: 10.1080/08038740118140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heylen L. The older, the lonelier? Risk factors for social loneliness in old age. Ageing Soc. 2010;30(7):1177–1196. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10000292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalogirou S, Murphy M. Marital status of people aged 75 and over in nine EU countries in the period 2000–2030. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3:74–81. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R, Lowenstein A, Phillips J, Daatland SO. Theorizing intergenerational family relations. In: Bengtson VL, Acock AC, Allen KR, Dilworth-Anderson P, Klein DM, editors. Sourcebook of family theory and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Newsom JT, Rook KS. Financial strain, negative social interaction, and self-rated health: evidence from two United States nationwide longitudinal surveys. Ageing Soc. 2008;28:1001–1023. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X0800740X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A, Daatland SO. Filial norms and family support in a comparative cross-national context: evidence from the OASIS study. Ageing Soc. 2006;26(2):203–223. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X05004502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon D, Glucksmann M. Comparative configurations of care work across Europe. Sociology. 2008;42(4):101–118. doi: 10.1177/0038038507084827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand AM. Stratification and the life course: the forms of life-course capital and their interrelationships. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 5. New York: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand AM. Stratification and the life course: life course capital, life course risks, and social inequality. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 6. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Perlman D. Perspectives on loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness. New York: Wiley; 1982. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman D, Peplau LA. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In: Gilmour R, Duck S, editors. Personal relationships 3: personal relationships in disorder. London: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov IC. The elderly in a period of transition: health, personality and social aspects of adaptation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1114:300–309. doi: 10.1196/annals.1396.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Silbereisen RK. Human development in times of social change: theoretical considerations and research needs. Int J Behav Dev. 2004;28(4):289–298. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: a meta-analysis. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2001;23(4):245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I. Social integration of the aged. New York: The Free Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Saraceno C, Keck W. Can we identify intergenerational policy regimes in Europe? Eur Soc. 2010;12(5):675–696. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2010.483006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf T, Jong Gierveld JD. Loneliness in urban neighbourhoods: an Anglo-Dutch comparison. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5(2):103–115. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0080-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf T, Phillipson C, Smith AE. Social exclusion of older people in deprived urban communities of England. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:76–87. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0025-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckelberger A, Vikat A (2008) A Society for all ages: challenges and opportunities. In: Proceedings of the UNECE ministerial conference on ageing, 6–8 November 2007 in León. United Nations, Spain

- Sundström G, Fransson E, Malmberg B, Davey A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6(4):267–275. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchernina NV, Tchernin EA. Older people in Russia’s transitional society: multiple deprivation and coping responses. Ageing Soc. 2002;22(5):543–562. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X02008851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tesch-Römer C, von Kondratowitz H-J. Comparative ageing research: a flourishing field in need of theoretical cultivation. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3(3):155–167. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomassini C, Glaser K, Wolf DA, Broese van Groenou M, Grundy E. Living arrangements among older people: an overview of trends in Europe and the USA. Popul Trends. 2004;115:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aartsen M, Jylhä M. Onset of loneliness in older adults: results of a 28 year prospective study. Eur J Ageing. 2011;8(1):31–38. doi: 10.1007/s10433-011-0175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Haegen H, Niedermaier P. Weisskirch: Ein Siebenbürgisches Dorf im Griff der Zeit. Acta Geogr Lovan. 1997;36:1–318. [Google Scholar]

- Victor C, Bowling A, Bond J, Scamber S (2003) Loneliness, social isolation and living alone in later life. Research findings: 17, April 2003. Economic and Social Research Council

- Weiss RS. Loneliness: the experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wurm W, Schöllgen I, Tesch-Römer C (2010) Gesundheit. In: Motel-Klingebiel A, Wurm S, Tesch-Römer C (eds) Altern im Wandel. Befunde des Deutschen Alterssurveys (DEAS). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, pp 90–117