Abstract

Dementia is a major challenge for health and social care services. People living with dementia in the earlier stages experience a “care-gap”. Although they may address this gap in care, self-management interventions have not been provided to people with dementia. It is unclear how to conceptualise self-management for this group and few published papers address intervention design. Initial focusing work used a logic mapping approach, interviews with key stakeholders, including people with dementia and their family members. An initial set of self-management targets were identified for potential intervention. Self-management for people living with dementia was conceptualised as covering five targets: (1) relationship with family, (2) maintaining an active lifestyle, (3) psychological wellbeing, (4) techniques to cope with memory changes, and (5) information about dementia. These targets were used to focus literature reviewing to explore an evidence base for the conceptualisation. We discuss the utility of the Corbin and Strauss (Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home. Jossey-Bass, Oxford, 1988) model of self-management, specifically that self-management for people living with dementia should be conceptualised as emphasising the importance of “everyday life work” (targets 1 and 2) and “biographical work” (target 3), with inclusion of but less emphasis on specific “illness work” (targets 4, 5). We argue that self-management is possible for people with dementia, with a strengths focus and emphasis on quality of life, which can be achieved despite cognitive impairments. Further development and testing of such interventions is required to provide much needed support for people in early stages of dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, Self-management, Patient education, Intervention development

Introduction

In early 2010 an estimated 821,884 people were living with dementia (around 1.3 % of the population) in the UK (Luengo-Fernandez et al. 2010), which is estimated to rise to 1,735,087 by 2051 (Alzheimer’s Society 2007). Dementia costs the UK economy over £17 billion per annum (Department of Health 2009), set to rise to £50 billion by 2031 (Comas-Herrera et al. 2007), and accounts for 11 % of total NHS costs for mental health (National Audit Office 2007). Dementia has extensive personal consequences, owing to losses in independence, decreased social activities and ability to initiate activities, co-morbid depression and reduced quality of life (Alzheimer’s Society 2007). Dementia can impact on multiple areas of life, including work, personal relationships, and psychological health through fear and emotional consequences of the diagnosis and changes to functioning (Mountain 2006). Healthy diet and exercise are potentially beneficial (Brodaty et al. 2003; Riviere et al. 2001). These behaviours require self-management.

People with dementia live on average 11–12 years after diagnosis, making it a chronic illness (National Audit Office 2007). Self-management interventions have been widely developed for people living with chronic illness. The National Dementia Strategy for England sets out 17 objectives to improve care for people with dementia and their family/carers, including early diagnosis and intervention for all, with the development of structured peer support and community support (Department of Health 2009). There is currently a “care-gap” as there is little care available in the early stages of dementia but services available for people with more advanced dementia (National Audit Office 2007).

Self-management may go some way to meet this care-gap for people living with early stage dementia. Early stage dementia is a descriptive term for the less advanced stages of dementia, where some cognitive processes remain relatively unaffected (Morris et al. 2001), experiencing mild impairment but able to maintain some level of independence (Kuhn 2007). Little research has addressed the applicability of self-management to people living with early stage dementia. It may be assumed that owing to even mild cognitive impairment, self-management skills are not learnable or feasible to enact, which further disempowers people with dementia in the early stages (Mountain 2006). First, it is shown that interventions have been useful for people with dementia, despite them placing some demands on cognitive capacity. Second, it is shown that not all aspects of self-management require the learning or use of specific skills. Indeed, self-management may be more widely conceptualised.

Self-management can be defined as a person’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical, psychological, social and lifestyle changes, and consequences of chronic illness (Department of Health 2005). Self-management is defined broadly as activities which help people to live well with their condition, maintain meaningful or pleasurable activity and achieve a good quality of life (Barlow et al. 2002; Corbin and Strauss 1988; Kitwood 1997). The aim of self-management is to live as well as possible with the chronic illness, achieving a good quality of life by shaping one’s life and reactions to illness (Corbin and Strauss 1992). Self-management interventions have been shown to be useful for a range of chronic conditions, improving wellbeing, health status, and reducing health service utilisation (Lorig and Holman 2003; Lorig et al. 1999).

There is a lack of interventions for people living with dementia and little research into their self-management (Mountain 2006). There is evidence for some cognitive, occupational therapy and psychotherapy approaches, for example (Brenske et al. 2008; Joosten-Weyn Banningh et al. 2008; Angevaren et al. 2008), support groups (Snyder et al. 2007), relaxation, and memory training (Rapp et al. 2002). The limited research suggests that self-management programmes could be beneficial to people with dementia for developing physical and emotional self-management strategies (Mountain 2006). The evidence also highlights that approaches which place demands on cognitive capacities have had some success with people with dementia.

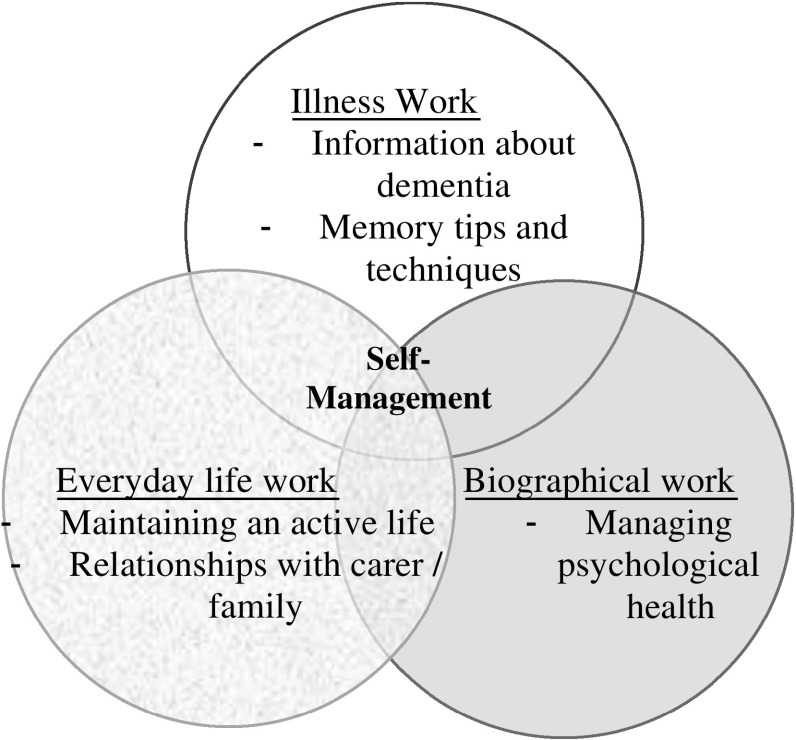

Broadly, self-management can be conceptualised as encompassing different types of work that the person must do to live well. According to Corbin and Strauss (1988, 1992) there are three overlapping types of “work”: illness work of medical management; everyday life work to sustain a meaningful life; and biographical work to manage emotional impacts. In many widely used self-management interventions, illness work such as medication adherence and exercise is focused on (Lorig et al. 1999). Goal scheduling and action planning are often included (Lorig and Holman 2003), supporting the maintenance of an active lifestyle, relating to everyday work. Biographical work may be supported by activities around acceptance and depression (Wilson et al. 2007). Dominant models of self-management have been criticised for neglecting the importance of everyday life and biographical work (Wilson et al. 2007), which may be important in dementia.

For different conditions, there are different foci for self-management (Lau-Walker and Thompson 2009), for example for diabetes there may be clear medical procedures or diet regimens, emphasising illness work and medical management (Warsi et al. 2004). Conversely, finding meaning in life and managing the psychological impacts may be more relevant in other conditions. For dementia, literature suggests that self-management tasks may include adherence to medication, engaging in activities to maintain cognitive function, emotional expression, and adjustment to illness to maintain a positive perspective (Clare et al. 2003). However, it is necessary to understand how self-management should be conceptualised for people with early dementia in order to design interventions, particularly as interventions fail if they are out of line with participants’ needs (Lawn and Schoo 2010). It is currently unclear which types of the work require more or less emphasis in an intervention for people with early dementia. Recently, Mountain and Craig (2012) published a suggested content for self-management intervention for people with dementia, based on a series of interviews, however, further work is necessary as they provided little reference back to the existing literature and theory. It remains necessary to create consensus and regarding necessary intervention content and focus.

This paper aims to conceptualise what self-management is for this group. First, we briefly describe data collection used to derive potential intervention targets. Second, we use these identified targets to focus literature searching to provide evidence for our conceptualisation of self-management for people with dementia in the early stages. This leads us to specify recommendations for intervention design and evaluation.

Focusing the literature review: initial conceptualisation of self-management targets

Owing to a paucity of literature around self-management for people with dementia, our study aimed to derive a conceptualisation. To do this, we used the “Coventry Intervention Development Process” (CIDP), (Martin et al. 2009, in press). The process first uses a logic-modelling approach through interviews with stakeholders to generate initial conceptualisation (Renger and Hurley 2006). In the second part of this process, the initial conceptualisation is used to target literature reviewing to explore evidence base for the conceptualisation and recommend potential intervention components and evaluation frameworks.

To begin, we interviewed a range of participants to provide reasons for why “People with dementia are not encouraged to take an active part in their care”, in the form of a logic map (reasons linked to one-another based on the participants’ perceived causal pathways). Seven people with dementia (one female), two family members (both female), and two charity representatives (one female) were recruited through the Alzheimer’s Society and were interviewed individually or in small groups. Eight health care professionals working in dementia services were interviewed individually. These were two Clinical Psychologists (one female), two Community Psychiatric Nurses (both female), two GPs (one female), and two Psychiatrists working in Older Adults services. [This process is described in full in (Martin et al. 2012)]. The reasons were integrated into a summary logic map, eliminating duplicated reasons, or those out with the remit of self-management (e.g., reasons relating to lack of government funding). Participants were then invited to complete an online survey to score the reasons for importance to good self-management and changeability through self-management intervention. Two clinical psychologists, two community psychiatric nurses, and two voluntary sector experts who had participated in step one and one psychiatrist working with older people, one person living with dementia and one self-management expert completed the questionnaire. Responses from the nine participants were analysed together. Antecedents with a mean rating greater than “moderately” important and changeable were selected as intervention targets. The evidence base linking these antecedents to self-management and outcomes was checked (any unsupported antecedents were removed). This gave rise to the initial conceptualisation of self-management for people with early dementia.

This first part of the process led to sixteen reasons why “People with dementia are not encouraged to take an active part in their care” that were at least moderately important and changeable. These reasons provided the initial conceptualisation and were grouped into five targets with two guiding overarching principles. Table 1 outlines targets which are: (1) support to seek information about dementia; (2) greater support to maintain an active life; (3) issues around relationship with family/friends/carers; (4) education/sharing of practical memory tips and techniques; and (5) support with psychological wellbeing, including low self-efficacy and perceived low self-worth.

Table 1.

Five intervention targets and the overarching principle

| Targets | Antecedents | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Relationship with carer | Carer might just do things for people with dementia (no chance to self-manage) |

| Carer has to encourage people with dementia to self manage | ||

| Need to do activities as a couple | ||

| Activity might not get done by people with dementia | ||

| Care roles are not always clear | ||

| 2. | Maintaining an active lifestyle | Not encouraged to stay active |

| People with dementia want to be able to take basic care of themselves | ||

| People with dementia have no access to activities | ||

| 3. | Psychological wellbeing | Insecurity, low self-efficacy and low self-esteem |

| People with dementia and carers might be in denial (or might not know) | ||

| 4. | Memory techniques | Memory techniques are not routinely taught |

| 5. | Information | Lack of information for people with dementia |

| People with dementia don’t know much about their condition | ||

| People with dementia don’t know what treatments or resources there are (e.g., Finance) | ||

| Overarching principles | Services and systems do not address individual needs of people with dementia | |

| Individual differences are not taken into account |

Reviewing the literature to conceptualise self-management for people with dementia

Our initial focusing work identified five potential intervention targets. PsycInfo, Medline, and CINAHL were searched to explore the relevance of the target to wellbeing in dementia, the evidence base for related interventions, and potential components for a self-management intervention. Searching concentrated first on dementia-specific research and was then broaden out to include self-management literature for other chronic conditions.

Target 1: relationship with family/friends/“carer”

In our focusing work, both people with dementia and family discussed the importance of this relationship and the challenges for both parties to ensure it is supportive. It is possible that family may take on the responsibility for activities that the person with dementia may still want to or feel able to continue to do. Conversely, appropriate social support facilitates goal achievement, which in turn affects wellbeing (Bandura 2004). Berg and Upchurch (2007) found that negotiation and positive validation in the dyad (person with dementia and family/friend/carer) are associated to better coping with chronic illness. Family/friends/carers who assume control, aiming to be supportive, may actually be tapping into the person’s greatest fears of dependency (Frazier et al. 2003). Maintaining involvement in everyday life is important for the dyad (Ablitt et al. 2009). In our conceptualisation of self-management intervention for dementia, the aim is for this relationship to be positively supportive, but not to return all decisions to the person with early dementia as this may be neither feasible nor beneficial.

Interventions addressing personal relationships for people living with dementia are scarce (Ablitt et al. 2009). An intervention for people with dementia and their caregivers used joint-problem solving together and communication tasks, reporting better interaction in the intervention group and caregivers were more satisfied with the interaction, although the person with dementia’s satisfaction was not reported (Corbeil et al. 1999). In-depth qualitative research has revealed the importance of couple relationships, specifically of sharing affection and enjoyment and maintaining involvement (Hellstrom et al. 2007). Negotiating tasks whilst facilitating the person with dementia to play an active part in everyday activity was a key part of dynamics of a couple relationships in dementia. Dividing up tasks and working together patiently was important. As dementia progressed, people did let go and a slow transition was evidenced.

Given the lack of available evidence or recommendations around this issue, conceptualisation of this target was discussed with expert input from Clinical Psychologists. Two sequential discussion sessions are suggested, whereby participants were encouraged to think about and discuss issues shown above to be related to wellbeing, including the impact of dementia on their personal relationships for both themselves and their significant other(s). This should be followed by a discussion of ways in which roles and activities could be negotiated and communication improved. The self-management task here is to discuss and adjust to the impact of dementia on relationships.

Target 2: maintaining an active lifestyle

This second intervention target addresses the perception that people with dementia are not encouraged to stay active or engage in meaningful or pleasurable activities. Maintaining an active lifestyle is important to wellbeing (Heyn et al. 2004) and is a key issue drawn out in the NICE clinical guideline for dementia (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence developed in conjunction with SCIE 2006). Self-efficacy, goal setting and pursuit are associated with wellbeing (Steverink et al. 2005). Maintaining an active life allows participants to experience pleasurable and meaningful activities, shown in positive psychology to improve quality of life (Seligman et al. 2005). Outdoor activities have been shown to provide a sense of meaning, enjoyment, and counter the experience that some people with dementia have that there world is shrinking (Duggan et al. 2008).

Groups for people with dementia which have ran activities suggested by the group members have found enjoyment of activities and increased subsequent housekeeping activities, although this did not increase quality of life (Carek 2004; Higgins et al. 2005). Goal-oriented rehabilitation with an educational component, memory strategies, mind-mapping and goal planning, led to better occupational performance and quality of life (Londos et al. 2008).

Common elements of many self-management courses are goal setting and activity planning, in addition to presentations and discussion of the benefits of staying active and healthy (Barlow et al. 2002; Lorig and Holman 2003). These should be used in a self-management programme for people with early dementia. Goal setting should be simplified to emphasise that doing something active is the key, rather than the standard more cognitively complex planning of implementation intentions (Gollwitzer 1999). The self-management task here is to maintain activity and through this maintain quality of life.

Target 3: psychological wellbeing

The psychological wellbeing target as identified from participants’ logic maps and prioritisation of issues includes insecurity, low self-efficacy, and low self-esteem, in addition to issues around acceptance. Self-acceptance is a coping strategy used by people with dementia, particularly in the early stages, to improve psychological wellbeing (Harris 2002). Psychological wellbeing is evidenced as important to dementia, not least as negative affect may inhibit concentration and exacerbate cognitive impairment (Carek 2005). Psychological coping is important to people with dementia for adjusting to diagnosis (Alzheimer’s Society and Mental Health Foundation 2008). Improving or maintaining psychological wellbeing is therefore important to self-management for dementia to improve quality of life but also to aid adjustment and attenuate negative impacts of affect on cognitive processes.

In previous research, the opportunity to express feelings and socialise at a memory support group was rated as useful by people with early stage dementia and the self-guided nature of the group increased perceptions of control (Carek 2004). Group processes were highly important in a qualitative exploration of a memory group (Scarboro 2000). Group-based discussion of emotions improve depression, anxiety and coping with people living with dementia (Cheston et al. 2003; Snyder et al. 2007). Group processes are found to be generally curative, with experiences of “universality” (spending time with others experiencing similar problems) being a major group factor in improving self-esteem and self-efficacy (Yalom and Leszcz 2005). This underlies the rationale for a group support intervention format. Self-management research interventions have included a range of activities addressing psychological wellbeing (Barlow et al. 2002; Lorig and Holman 2003), which are detailed in relation to our intervention below.

Breathing and relaxation is commonly used in self-management interventions to decrease stress in response to symptoms of chronic illnesses (Barlow et al. 2005). Gratitude activities have been identified as beneficial to acceptance and self-perceptions within positive psychology research (Seligman 2002). Identifying personal strengths can help improve one’s evaluation of self-esteem (Seligman et al. 2005). Identifying pleasurable activities, here named “techniques to increase happiness”, is a drawn from wider cognitive-behavioural therapy interventions, as first identifying and then engaging in such activities can improve mood, view of self and self-efficacy (Ryan and Deci 2001; Moniz-Cook et al. 2009). Goal setting and achievement, as in target 2, is relevant here as this is beneficial to psychological wellbeing, improving self-efficacy, and perceived self-worth (Frazier et al. 2003) and sharing goal successes can improve perceived self-efficacy (Bandura and Jourden 1991). Self-acceptance exercises have been developed to emphasis that we all have positive and negative characteristics (Dryden 1998). Self-acceptance has been improved by self-management interventions (Abraham and Gardner 2008). These activities are all suggested as these would facilitate the self-management task of pursuing and maintain wellbeing.

Target 4: techniques to cope with memory change

The fourth target addresses tips and techniques for living with an impaired memory, a key issue in the experience of living with dementia which causes distress and frustration (Alzheimer’s Society and Mental Health Foundation 2008).

In memory support groups, group processes and support from others were found to be more helpful than the actual sharing of memory tips (Scarboro 2000) and most memory retaining interventions have had poor results (Burns 2005). A complex intervention for mild cognitive impairment using external aids and coping techniques found increased use of techniques at 2 weeks after the intervention, but not at 4 months follow-up (Kinsella et al. 2009). Memory enhancement training, with education on dementia, memory performance, and memory skills training such as chunking and cueing, has been tested. This revealed no objective improvement in memory but improved perceived memory (Rapp et al. 2002) and wellbeing, owing to decrease distress around memory (Schmitter-Edgecombe et al. 2008). Accepting changes owing to chronic illness is an important part of self-management: “letting go” of one’s previous identity may promote adjustment (Aujoulat et al. 2008).

We concluded that components to provide supportive tips and techniques may not improve memory but may improve coping with memory loss, fitting into our intervention logic. The conceptualisation of self-management for dementia is highly focused on improving the subjective experience of living with dementia. The opportunity for people to share strategies is seen as important by people with dementia and can be empowering (LaBarge and Trtanj 1995; Nomura et al. 2009). We suggest a sharing memory tips session, focusing on decreasing distress around memory by providing some practical tips to aid perceptions of manageability of memory loss and to introduce the idea of accepting changes to memory. It could be said there is an apparent tension between strategies to control memory and discussion around accepting memory changes, however, accepting loss does not mean no longer trying to use memory or perceive it as potentially controllable and useful. The session should encourage the acceptance of changes, whilst also decreasing distress by providing strategies which make this loss feel more manageable. In addition, memory box activities were suggested during consultation with Alzheimer’s Society representatives, which covered how to create a memory box which contains photographs and mementoes. This can be both an enjoyable activity to create in the early stages of dementia as well as a helpful resource as dementia progresses.

Target 5: information

Information needs covers a wide range of different topics including what dementia is as a disease, features of disease progression, what losses in functioning to expect, what medical and psychological interventions exist, resources such as financial benefits. Evidence supports the relevance of this target: receiving information was reported as very important to adjusting to diagnosis by people with dementia (Alzheimer’s Society and Mental Health Foundation 2008).

A recent meta-synthesis of information provision in self-management generally found this is most useful at an early stage in illness and when information is tailored (Protheroe et al. 2008). Provision of information to people with dementia specifically has been found to be useful, for example, providing and sharing information, with self-guided information seeking in a memory group (Carek 2004) and an 8 week day care program (Higgins et al. 2005). Specific strategies used with people with early dementia to address information needs include information sessions where topics were discussed with handouts with information and opportunities to ask questions and provide answers, which was evaluated qualitatively as very useful (Carek 2004). Social cognitive theory suggests that information is important to what participants expect to experience and therefore how they behave (Bandura 2004), providing instruction also.

Based on these recommendations, our conceptualisation of self-management intervention here includes self-guided information, achieved through a specific “Q&A Open Space” session where participants are able to ask questions about dementia and an emphasis throughout on asking questions of one-another and the tutors. Throughout the intervention, participants should be signposted to information sources and empowered to access and share information (after Rice and Warner 1994). In addition, an activity around successful working with health and social care professionals should be included, as seen in many other self-management interventions (Lorig and Holman 2003), as this enables participants to better use their relationship with health and social professionals to access information specific to them.

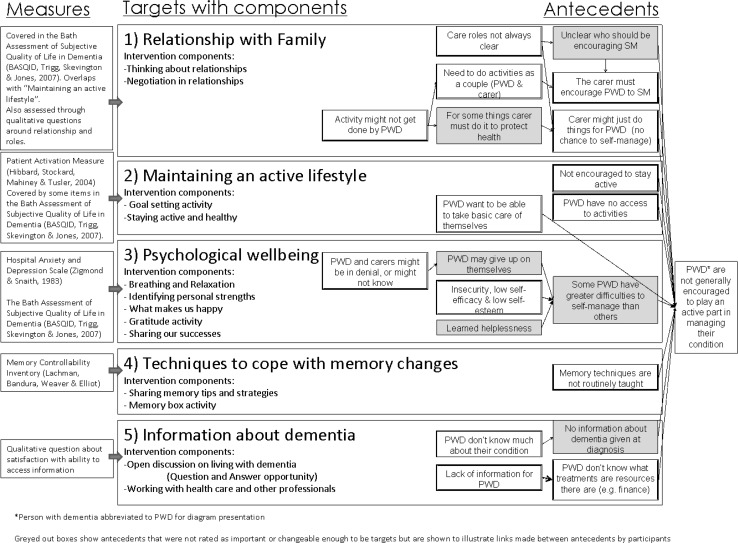

Evaluating self-management intervention for dementia

An evaluation framework was designed to explore the impact of the intervention on the targets. There are a limited number of outcome measures validated for completion by people in the early stages of dementia, rather than completion by a carer. An initial list of potential measures was drafted from the literature search and the expert panel commented via email. These measures have items addressing intervention aims 1–4. Expert consultation suggested that the best way to explore whether information provision had been achieved was through interviews, as tests of knowledge were not suitable with this group. The recommended primary outcome measure is the Bath Assessment of Quality of Life in Dementia (Trigg et al. 2007) with secondary outcome measuring Patient Activation Measure (Hibbard et al. 2004), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond and Snaith 1983) and Memory Controllability Inventory (Lachman et al. 1995). These are shown in Fig. 1, which illustrates the conceptualised intervention targets, based on the logic maps derived from initial focusing work.

Fig. 1.

Intervention logic with components and outcome measures

Proposed self-management intervention content

The literature reviewed above provides some insight into potential intervention structure and components. Based on the literature review, a list of potential components was compiled and sent to clinical psychologists working with people with dementia, representatives of the Alzheimer’s society, a person living with dementia and their spouse, an experience lay-self-management tutor and expert researchers in dementia and chronic disease management. Their comments and suggestions were collated. From this, the intervention content was derived. An intervention manual was produced which details the suggested components (available on request from authors). The intervention sessions are outlined in Table 2. Sessions were structured to have consistent first and final activities, creating a sense of routine and familiarity. Table 2 also highlights the link between each suggested component and the conceptualisation of self-management for people with dementia. This facilitates evaluation of the intervention: each intervention target has a selection of components and if the target outcome is not changed, it is possible to easily identify the components which may require further work. Intervention piloting is now possible.

Table 2.

Course objectives and activities for each session

| Overall course objectives: |

| (1) Participants feel more able to communicate their feelings and needs to their family and friends |

| (2) Participants feel more able to maintain an active lifestyle through goal setting and scheduling of pleasurable activities and events |

| (3) Participants experience an improved quality of life and psychological wellbeing |

| (4) Participants are more aware of strategies for coping with changing memory and have the opportunity to share their strategies |

| (5) Participants feel more able to access relevant information |

| Session | Brief description | Target addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | ||

| 1.1 Opening and introduction | Introductions, outline of participants’ responsibilities | (Introductory material) |

| 1.2 Course overview: what is self-management | Outline of course structure, content and aims | (Introductory material) |

| 1.3 Gratitude activity | Identifying and sharing experiences to be thankful for. Generating and sharing positive emotions | Psychological wellbeing |

| Break | ||

| 1.4 Practice better breathing | Introduction to diaphragmatic breathing | Psychological wellbeing |

| 1.5 Prepare for change and goal setting | Identifying goals that are pleasurable and meaningful. Noting down and sharing goals. (Participants to share written copy of goal with family/friend and receive mid-week reminder phone call) | Maintaining an active lifestyle |

| Session 2 | ||

| 2.1 Feedback from goal setting and gratitude activity | Discuss outcome from 1.5, difficulties and successes. Discussing and sharing of completed gratitude activities from session 1.3 | Maintaining an active lifestyle, psychological wellbeing |

| 2.2 Relaxation | Practicing diaphragmatic breathing | Psychological wellbeing |

| 2.3 Open Space discussion on living with dementia | Discuss the information participants have used, what is more or less useful, remaining questions and explore ways to seek out information | Information |

| Break | ||

| 2.4 Staying active and healthy | Discuss the importance of staying active and healthy, including diet and exercise. Problem solving around how to stay active and healthy | Maintaining an active lifestyle |

| 2.5 Goal setting | As in 1.5 | As in 1.5 |

| Session 3 | ||

| 3.1 Feedback from goal setting and gratitude activity | As in 2.1 | As in 2.1 |

| 3.2 Relaxation | Practise diaphragmatic breathing focusing on one word associated with relaxation | Psychological wellbeing |

| 3.3 Identifying personal strengths | Based on Seligman’s (2002) suggested activity, present participants with list of strengths then discuss which strength they identify with most | Psychological wellbeing |

| Break | ||

| 3.4 Sharing memory tips and strategies | Express emotions around dealing with memory loss and share these experiences. Share strategies participants use which help reduce negative emotions around memory loss | Techniques to cope with memory change |

| 3.5 Goal setting | As in 1.5 | As in 1.5 |

| Session 4 | ||

| 4.1 Feedback from goal setting and gratitude activity | As in 2.1 | As in 2.1 |

| 4.2 Relaxation | Sensory relaxation activity with imagery of, e.g., walking through a garden on a summer’s day (or, if participants request more practice, return to activity 3.2) | Psychological wellbeing |

| 4.3 Memory box | Share the idea of a memory box and how to make one (box of personal mementoes and photos important to the individual, often accompanied with brief written description). Encourage to again share emotions associated with memory loss and positive past memories | Techniques to cope with memory change |

| Break | ||

| 4.4 Techniques to increase happiness | Building on personal strengths activity (3.3), discuss idea that doing activities we are good at can increase happiness. Discuss continued importance of enjoyment in life. Encourage participants to focus on strengths and set goals around this | Psychological wellbeing |

| 4.5 Goal setting | As in 1.5 | As in 1.5 |

| Session 5 | ||

| 5.1 Feedback from goal setting and memory box | As in 2.1 | As in 2.1 |

| 5.2 Relaxation | As in 4.2 | |

| 5.3 Thinking about relationships | Discuss changes in personal relationships and emotions associated to this. Guide consideration of reasons for this. Consider importance of maintaining activity and how this may impact on relationships. (May illustrate with a story of a couple or family taken from tutor’s experience or Alzheimer’s Society online resources) | Relationships with family/friends/“carer” |

| Break | ||

| 5.4 Negotiation in relationships | Consider the advantages and disadvantages of talking about emotions and difficulties with family/friends/carer, for example negotiation required around who does household chores Encourage participants to discuss any difficulties openly and plan how communication could be improved | Relationships with family/friends/“carer” |

| 5.5 Goal setting | As in 1.5 | As in 1.5 |

| Session 6 | ||

| 6.1 Feedback from goal setting | As in 2.1 | As in 2.1 |

| 6.2 Relaxation | As in 4.2 | Psychological wellbeing |

| 6.3 Working with health and social care professionals | Explore aspects of relationships with health and social care that work and do not work so well. Present and discuss list of commonly used improvement strategies including, e.g., booking double appointments and ensuring ask questions when information provided is too complex | Information |

| Break | ||

| 6.4 Self-acceptance | Tutor first models and then asks participants to think of some negative characteristics, then some of their positive characteristics. Review idea that we are all a mixture of positive and negative | Psychological wellbeing |

| 6.5 Sharing our successes | Share recent successes, including attending the course, enjoying the sessions, being more active and achieving goals for example | Psychological wellbeing |

| 6.6 Course close and completion of feedback | Review course material. Collect feedback. Thank participants | Course end |

Discussion

We present a conceptualisation of self-management for people with early stage dementia, based on initial focusing work and targeted reviews of the literature. Suggested outcome measures and intervention content further illustrate our conceptualisation and provide a pilot intervention structure to be tested.

Self-management for dementia was conceptualised as focusing on (1) relationship with family/friend/carer, (2) maintaining an active lifestyle, (3) psychological wellbeing, (4) techniques to cope with memory change, and (5) information about dementia. This relates to Corbin and Strauss’ (1988) model of self-management work, with relationship with family and maintaining an active lifestyle relating to “everyday life work”, psychological wellbeing relating to “biographical work” and techniques to cope with memory change and information about dementia being “illness work”. The conceptualisation then emphases everyday life work and biographical work, over illness work. This is summarised in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Illustrating the conceptualisation of self-management for people living with early dementia, after Corbin and Strauss (1985)

Tasks such as learning new health information, remembering to take medications and remembering to schedule health care appointments may be perceived as beyond the ability of the person with dementia, owing to cognitive impairment. This may explain the dearth of research into self-management for people with dementia. However, this represents a narrow view of self-management. Self-management extends beyond such tasks and includes aims to improve personal resilience, quality of life, and increase levels of activity (Jones 2010). Here self-management is more emotion than problem focused (Davies and Batehup 2010) and more focused on managing one’s life with the condition than managing the condition itself. Our conceptualization of self-management for dementia challenges medically dominated ideas of self-management as performing illness work such as medication adherence and differs from many other self-management interventions (Wilson et al. 2007), partly as there is currently a lack of commonly prescribed, effective treatments for dementia. Some interventions run the risk of “medicalising” self-management (Wilson et al. 2007), de-emphasising emotional experiences and enjoyment. Kitwood emphasized the importance in dementia care of attending to the person, treating people as individuals with interests and desires and worries of their own, valuing people, and their strengths and providing a positive environment (Kitwood 1997). Our conceptualisation of self-management for people with dementia echoes these elements of person centred care and re-emphasises the “self” within “self management of long-term conditions”.

A strong emphasis is placed on maintaining activities and working with one’s strengths. Maintaining an active life is thought to be important to dementia, and is specified in clinical guidelines (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence developed in conjunction with SCIE 2006). The emphasis on these activities is also related to the aim of self-management to improve or maintain quality of life. The experience of positive events and emotions are known to remain with people with dementia and have a positive impact on their quality of life (Trigg et al. 2007). Wellbeing for people with dementia includes self-esteem, positive affect and behaviours, reduced negative affect and a feeling of belonging (Brod et al. 1999), which can be fostered through self-management intervention.

We have presented suggested intervention components (see Table 2) to address the targets from our conceptualization of dementia. Evidence was found to support the importance of the different intervention targets. It must be stated, however, that owing to a lack of research on interventions with people with early stage dementia, some suggested components cannot be said to be evidence-based and require further investigation. It is suggested that this is achieved by further developing and testing of our outline self-management intervention. This is particularly true for the components around relationship with family/friends and carers, where there was a paucity of research.

Our initial focusing work specified targets for our intervention conceptualisation. The process engaged service users and their families, in addition to representatives from charities and health care professionals, ensuring patient and public involvement to guide how we conceptualise self-management for this group. The logic map provides hypothesised relationships between antecedents that cause the problem: here antecedents that underlie why people with dementia are not encouraged to play an active part in their care. These antecedents provide intervention targets, for which evidence-based intervention components can be designed. The initial focusing work lead to “logic maps”. We found that as participants go through the process of providing a logic chain, details are built up which provide not only “why” the problem exists, but also start to suggest “what” may be needed and “how” improvements may come about. These data may be accessible by semi-structured interviewing, however, maintaining focus on the problem and its causes may be challenging and more time-consuming (logic mapping interviews typically take less than 45 min). Furthermore, participants may be strategy focused, suggesting ways to deal with the problem without considering the underlying logic of this (Renger and Hurley 2006) typifying many of the difficulties with the early stages of intervention development, where the risk is that intervention components are included without a clear underlying rationale (Webb et al. 2010). Our research concentrates on people in the early stages of dementia, for whom logical thinking and working memory remain largely unimpaired (Pasquier 1999; Braver et al. 2005) and visual cognition is generally preserved (Morris et al. 2001), supporting the use of this type of logic mapping method. Guidance on conducting research with people with dementia suggests a non-judgmental stance, accepting what participants say, building rapport and working to make the participant feel valued (Hellström et al. 2007); this guidance was followed. The active involvement of people with dementia in our focusing work increases the validity of our conceptualisation.

This study is limited by a relatively small sample used for the initial focusing of self-management. The nature of participants’ cognitive impairment and socio-demographic data are not known in detail, which may limit the degree to which the results are representative of other people living with dementia. The comments are inherently subjective, however, support was found in the research literature for each target for intervention which formed the overall conceptualisation. Further research, perhaps using more in-depth qualitative interviews, may be required to ensure that the targets captured by our conceptualisation are more widely endorsed. However, it must be stated that the more indepth qualitative research (rather than our mixed approach using literature reviewing) used by Mountain and Craig (2012) led to a similar conceptualisation, supporting the validity of the conceptualisations. For the proposed intervention components and design, there were some areas where there was a lack of research specific to dementia. This was particularly true for components dealing with relationship with carer/family/friends. Further research in how to address these targets is required to better inform intervention content.

One key advantage of our initial focusing work using logic mapping is the clear conceptualisation where suggested intervention components are clearly and specifically linked to both outcomes and underlying needs, thus providing a clear intervention logic. The next stage is to test intervention feasibility, re-assess the value of the components, re-test and trial for efficacy. We recommend that future research should also concentrate on creating a greater evidence base for the intervention targets, in particular how best to improve relationships with family/friends and carers. The intervention components can then be modified to incorporate relevant additions to the evidence. In addition, research exploring the degree to which these targets capture all important and changeable elements of self-management for people with dementia is suggested. Semi-structured interviews exploring the relevance of the suggested targets to a wider range of people living with dementia may be a good starting point. Further consideration is required of the level of preserved cognitive functioning required to engage in these elements of self-management and how the emphasis of self-management may alter as the disease progresses. The pilot intervention is outlined and further research is required to understand not only its potential acceptability, feasibility, efficacy, and effectiveness but also to explore the best time to deliver this in terms of time since diagnosis and the characteristics of participants who may benefit most in terms of types of impairments and support needs.

In conclusion, we recommend that self-management for people with early stage dementia be conceptualised as emphasising maintenance of activity and personal relationships in everyday life and management of psychological wellbeing, with additional components specific to the “illness work” of coping with memory change and accessing information (Corbin and Strauss 1988). The evidence base for potential intervention components to address these tasks of self-management provides insight into how interventions can be developed and tested. We argue that self-management is possible with dementia and further development and testing of such interventions is required to provide much needed support for people in the early stages of dementia.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Warwick Coventry Primary Care Research.

References

- Ablitt A, Jones GV, Muers J. Living with dementia: a systematic review of the influence of relationship factors. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(4):497–511. doi: 10.1080/13607860902774436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham C, Gardner B. What psychological and behaviour changes are initiated by ‘expert patient’ training and what training techniques are most helpful? Psychol Health. 2008;24(10):1153–1165. doi: 10.1080/08870440802521110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society (2007) Dementia UK: the full report, London

- Alzheimer’s Society, Mental Health Foundation (2008) Dementia: out of the shadows. Alzheimer’s Society, London

- Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJJ, Aleman A, Vanhees L (2008) Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev (3): CD005381 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Aujoulat I, Marcolongo R, Bonadiman L, Deccache A. Reconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: a critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1228–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Jourden FJ. Self-regulatory mechanisms governing the impact of social comparison on complex decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(6):941–951. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow JH, Bancroft GV, Turner AP. Self-management training for people with chronic disease: a shared learning experience. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(6):863–872. doi: 10.1177/1359105305057320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(6):920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Satpute AB, Rush BK, Racine CA, Barch DM. Context processing and context maintenance in healthy aging and early stage dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Psychol Aging. 2005;20(1):33–46. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenske S, Rudrud EH, Schulze KA, Rapp JT. Increasing activity attendance and engagement in individuals with dementia using descriptive prompts. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41(2):273–277. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brod M, Stewart AL, Sands L. Conceptualisation of quality of life in dementia. J Ment Health Aging. 1999;5(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Green A, Koschera A. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):657–664. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A. Your guide to Alzheimer’s disease. London: Hodder Arnold; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carek V. The Memory Group: a need-led group for those affected by a diagnosis of early-stage dementia. PSIGE Newslett. 2004;88:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carek V. Supporting each other: the Calderdale Memory Group. Ment Health Learn Disabil Res Pract. 2005;2:124–136. doi: 10.5920/mhldrp.2005.22124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheston R, Jones K, Gilliard J. Group psychotherapy and people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(6):452–461. doi: 10.1080/136078603100015947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Woods RT, Moniz Cook ED, Orrell M, Spector A (2003) Cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive training for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003260 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Pickard L, Knapp M. Cognitive impairment in older people: future demand for long-term care services and the associated costs. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(10):1037–1045. doi: 10.1002/gps.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbeil RR, Quayhagen MP, Quayhagen M. Intervention effects on dementia caregiving interaction. J Aging Health. 1999;11:79–95. doi: 10.1177/089826439901100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Managing chronic illness at home: three lines of work. Qual Sociol. 1985;8(3):224–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00989485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home. Oxford: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A (1992) Nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the trajectory framework. In: Woog P (ed) The chronic illness trajectory framework. Springer, New York, pp 9–28 [PubMed]

- Davies N, Batehup L. Self-management support for cancer survivors: guidance for developing interventions: an update of the evidence. London: Macmillan Cancer Support; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2005) Promoting optimal self care consultation techniques that improve quality of life for patients and clinicians. Department of Health, London

- Department of Health (2009) Living well with dementia: a national dementia strategy. Department of Health, England

- Dryden W. Developing self-acceptance. Chichester: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan S, Blackman T, Martyr A, Schaik PV. The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: ‘a shrinking world?’. Dementia Int J Soc Res Pract. 2008;7(2):191–204. doi: 10.1177/1471301208091158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier LD, Cotrell V, Hooker K. Possible selves and illness: a comparison of individuals with Parkinson’s disease early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, and healthy older adults. Int J Behav Med. 2003;27(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54:493–503. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PB. The person with Alzheimer’s disease: pathways to understanding the experience. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom I, Nolan M, Lundh U. Sustaining ‘couplehood’: spouses’ strategies for living positively with dementia. Dementia Int J Soc Res Pract. 2007;6(3):383–409. doi: 10.1177/1471301207081571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström I, Nolan M, Nordenfelt L, Lundh U. Ethical and methodological issues in interviewing persons with dementia. Nursing Ethics. 2007;14(5):608–619. doi: 10.1177/0969733007080206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn P, Abreu BC, Otthenbacher KJ. The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(10):1694–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins M, Koch K, Hynan LS, Carr S, Byrnes K, Weiner MF. Impact of an activities-based adult dementis care program. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(2):165–169. doi: 10.2147/nedt.1.2.165.61050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones FR (2010) Self-management and patient and public involvement: an interview with Bob Sang. In: Jones FR (ed) Perspectives on lay led self-management courses for people with long-term conditions. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 107–114

- Joosten-Weyn Banningh LW, Kessels RP, Olde Rikkert MG, Geleijns-Lanting CE, Kraaimaat FW. A cognitive behavioural group therapy for patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and their significant others: feasibility and preliminary results. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(8):731–740. doi: 10.1177/0269215508090774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella GJ, Mullaly E, Rand E, Ong B, Burton C, Price S, Phillips M, Storey E. Early intervention for mild cognitive impairment: a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:730–736. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.148346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D (2007) Helping families face the early stages of dementia. In: Cox CB (ed) Dementia and social work practice: research and interventions. Springer Publishing Co., New York

- LaBarge E, Trtanj F. A support group for people in the early stages of dementia of Alzheimer type. J Appl Gerontol. 1995;14:289–301. doi: 10.1177/073346489501400304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Bandura A, Weaver SL, Elliot E. Assessing memory control beliefs: the memory controllability inventory. Aging Cognition. 1995;2:67–84. doi: 10.1080/13825589508256589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Walker M, Thompson DR. Self-management in long-term health conditions—a complex concept poorly understood and applied—letter to the editor. Patient Educ Counsel. 2009;75:290–292. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn S, Schoo A. Supporting self-management of chronic health conditions: common approaches. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londos E, Boschian K, Lindén A, Persson C, Minthon L, Lexell J. Effects of a goal-oriented rehabilitation program in mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(2):177–183. doi: 10.1177/1533317507312622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Sobel D, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Bandura A, Ritter P, Gonzalez VM, Laurent D, Holman HR. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A (2010) Dementia 2010: The Economic Burden of Dementia and Associated Research Funding in the United Kingdom. Alzheimer’s Research Trust, England

- Martin F, Turner A, Wallace L, Bradbury NM (2009) Developing a self-management intervention for people with early stage dementia. In: United Kingdom society for behavioural medicine conference, Southampton, 14–15 Dec 2009

- Martin F, Turner A, Bourne C, Batehup L (in press) Supporting patient-initiated follow-up for testicular cancer survivors: development and qualitative evaluation of a self-management workshop. Oncol Nurs Forum [DOI] [PubMed]

- Martin F, Turner A, Wallace L, Choudhry K, Bradbury N. Perceived barriers to self-management for people with dementia in the early stages. Dementia. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1471301211434677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moniz-Cook E, Gibson G, Harrison J, Wilkinson H (2009) Timely psychosocial interventions in a memory clinic. In: Moniz-Cook E, Manthorpe J (eds) Early psychosocial interventions in dementia: Evidence-based practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, pp 50–70

- Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller P, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, Berg L. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:397–405. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain GA. Self-management for people with early dementia: an exploration of concepts and supporting evidence. Dementia Int J Soc Res Prac. 2006;5(3):429–446. doi: 10.1177/1471301206067117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain GA, Craig CL. What should be in a self-management programme for people with early dementia? Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(5):576–583. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.651430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office . Improving services and support for people with dementia. London: National Audit Office; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence developed in conjunction with SCIE (2006) NICE Clinical Guideline 42: dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London

- Nomura M, Makimoto K, Kato M, Shiba T, Matsuura C, Shigenobu K, Ishikawa T, Matsumoto N, Ikeda M. Empowering older people with early dementia and family caregivers: a participatory action research study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier F. Early diagnosis of dementia: neuropsychology. J Neurol. 1999;246(1):6–15. doi: 10.1007/s004150050299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protheroe J, Rogers A, Kennedy A, Macdonald W, Lee V. Promoting patient engagement with self-management support information: a qualitative meta-synthesis of processes influencing uptake. Implementation Science. 2008;3:44. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp SR, Brenes G, Marsh AP. Memory enhancement training for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a preliminary study. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(1):5–11. doi: 10.1080/13607860120101077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renger R, Hurley C. From theory to practice: lessons learned in the application of the ATM approach to developing logic models. Eval Prog Plan. 2006;29:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice K, Warner N. Breaking the bad news: what do psychiatrists tell patients with dementia about their illness? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994;9(6):467–471. doi: 10.1002/gps.930090605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere S, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Voisin T, Reynish E, Andrieu S, Lauque S, Salva A, Frisoni G, Nourhashemi F, Micas M, Vellas B. A nutritional education program could prevent weight loss and slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2001;5(4):295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarboro J. Developing and evaluating a memory support group for people with memory difficulties. PSIGE Newslett. 2000;73:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Howard JT, Pavawalla SP, Howell L, Rueda A. Multidyad memory notebook intervention for very mild dementia: a pilot study. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(5):477–487. doi: 10.1177/1533317508320794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press/Simon and Schuster; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology process: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol. 2005;60(5):410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder L, Jenkins C, Joosten L. Effectiveness of support groups for people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: an evaluative survey. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Demen. 2007;22(1):14–19. doi: 10.1177/1533317506295857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Slaets J. How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigg R, Skevington SM, Jones RW. How can we best assess the quality of life of people with dementia? The bath assessment of subjective quality of life in dementia (BASQID) The Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):789–797. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(9/23):1641–1649. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Sniehotta FF, Michie S. Using theories of behaviour change to inform interventions for addictive behaviours. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1879–1892. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PM, Kendall S, Brooks F. The expert patients programme: a paradox of patient empowerment and medical dominance. Health Soc Care Commun. 2007;15(5):426–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID, Leszcz M. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. 5. New York: Basic Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]