Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) causes around 1 million deaths annually.1 Guidelines for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD have been published by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)2 and regional bodies such as the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS),3 the United Kingdom's National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE),4 and the Canadian Thoracic Society.5 Although such guidelines are updated regularly, they lag behind developments in clinical research. Furthermore, adherence to guidelines by practising doctors is often poor.6

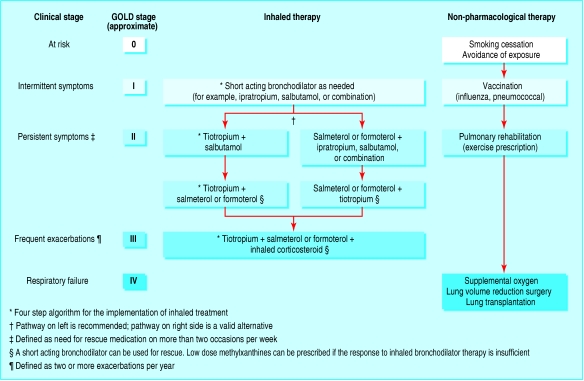

On the basis of a review of recent medical developments, we describe a practical, patient oriented approach to the hierarchical implementation of pharmacotherapy in COPD. Published guidelines and many recent articles have acknowledged that modern management should embrace long acting bronchodilators and consider the potential role of inhaled corticosteroids and the stage at which they should be introduced. We have developed an algorithm that includes these important treatments.

Sources and search criteria

We reviewed the most recent guidelines from GOLD (August 2004), NICE (February 2004), and ATS/ERS (June 2004), and supplemented these by searching PubMed, using the criteria (“COPD” or “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”) and “bronchodilator” for publications between January 2002 and March 2004. We found 21 recent clinical trials not cited in the GOLD guidelines, which covered combination therapy (inhaled corticosteroid plus β2 agonist), the anticholinergic tiotropium taken once daily, and several meta-analyses of use of inhaled corticosteroid.7-10 w1-w17

Diagnosis and staging

Since therapeutic strategies in COPD and asthma differ markedly, differential diagnosis is key to optimal management. Asthma should be suspected in patients with a childhood history of asthma, recurrent respiratory infections or episodes of “bronchitis,” or a family history of asthma or atopy (hay fever, allergic rhinitis, and eczema). COPD should be suspected in patients with a history of harmful exposure, most commonly a smoking history of 20 pack years or more but also exposure to environmental and occupational pollutants. The diagnostic criterion for COPD is now a ratio of forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 70% after using a bronchodilator.

Recent developments

Tiotropium is now available as a once daily long acting anticholinergic bronchodilator

Formoterol and salmeterol are available as choices of long acting β adrenoreceptor agonists

Pulmonary rehabilitation is advantageous to reverse physical deconditioning

Supplemental oxygen should be prescribed as a portable system to enhance physical activity

Lung volume reduction surgery can be considered for patients with upper lobe predominant emphysema and lower exercise capacity

Historically, severity of COPD has been classified according to FEV1, which may not correlate directly with symptoms. A symptomatic approach to therapy using clinical stages may be more useful (fig 1).

Fig 1.

Clinical algorithm for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Clinical stages are defined symptomatically (see footnote). GOLD stage refers to the classification of COPD on the basis of spirometry after using a bronchodilator

The role of inhaled therapy

Inhaled therapy, including bronchodilators and steroids, is one of several, often complementary, approaches to COPD treatment, as shown in figure 1. Inhaled bronchodilators comprise anticholinergics, which relax airway smooth muscle by blocking cholinergic tone (the primary reversible component in COPD), and β2 agonists, which are non-specific, functional bronchodilators that work via the sympathetic pathway. Short acting inhaled bronchodilators are the traditional basis of COPD pharmacotherapy. However, newer long acting bronchodilators are more suitable for maintenance treatment because they are more effective and convenient.2

Short acting inhaled bronchodilators

These include the anticholinergics ipratropium and oxitropium and the β2 agonists salbutamol, terbutaline, and pirbuterol.2 Short acting bronchodilators improve lung function, although their effect on symptoms, exercise capacity, exacerbations, and health status is less clear.11,12 They are generally well tolerated. Quick acting β2 agonists are recommended for use as needed to relieve intermittent symptoms, alone for patients with mild COPD and intermittent symptoms, and together with other agents in patients with severe disease.

Long acting inhaled bronchodilators

Long acting inhaled bronchodilators include the anticholinergic tiotropium, given once daily, and the β2 agonists salmeterol and formoterol, given twice daily.2 All improve lung function, although they differ in their mechanisms and duration of effect. Compared with salmeterol twice daily, tiotropium once daily provides superior bronchodilation for 24 hours13,14; also, salmeterol may lose efficacy over time.14

Long acting bronchodilators also improve patient centred outcomes such as exercise capacity, dyspnoea, and health related quality of life.13 Both tiotropium and formoterol improve health related quality of life more than ipratropium.13 Tiotropium also reduces the time to first exacerbation compared with placebo (fig 2).7

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of no exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in patients receiving tiotropium 18 μg once a day, salmeterol 50 μg twice a day, or placebo for six months7

The reduction of lung hyperinflation with tiotropium is likely to contribute to the improvements in dyspnoea seen in COPD patients.15 Since long acting bronchodilators provide more effective and longer lasting relief of symptoms than short acting bronchodilators they should be used for patients who have persistent symptoms that require frequent use of medication.13

Inhaled corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids include fluticasone propionate, budesonide, and beclomethasone dipropionate. Although commonly used in asthma, they seem to be ineffective as a maintenance treatment for mild to moderate COPD,2 because of the different nature of the underlying inflammation.16 Meta-analysis shows that inhaled corticosteroids reduce the rate of exacerbations.17 Another recent, but controversial, meta-analysis shows that inhaled corticosteroids may slow the rate of decline in FEV1.18 Although the effect was small and possibly of little clinical importance (the rate of decline fell by 9 ml/year), a trend was obvious towards a greater effect in patients with more severe airflow limitation (FEV1 ≤ 50% predicted) and at higher doses. A further meta-analysis of the results of six randomised, placebo controlled trials of inhaled corticosteroids in 3571 patients with COPD followed from 24 to 54 months did not find a significant association between inhaled corticosteroids and the rate of decline in FEV1.19

It is important, moreover, to take into account the adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroids, such as loss of bone mineral density and development of cataracts and glaucoma, particularly at higher doses.20 Because of the equivocal evidence of efficacy and the potential for side effects, inhaled corticosteroids are not approved for use in COPD in many countries, and their use should be considered only in patients with a history of frequent exacerbations.

Combination therapy

Since anticholinergics and β2 agonists have differing mechanisms of action, combination therapy can provide additive effects, as has been shown for the combination of a short acting anticholinergic with either a short acting or a long acting β2 agonist.21 w18

Maintenance treatment with a combination of anticholinergic and β2 agonist bronchodilators is suitable for patients who have more severe symptoms, especially those with a history of frequent exacerbations.2 The combination of a long acting anticholinergic and a long acting β2 agonist should also provide additive effects,22 although this has been tested only in one small study.23

Recently, five clinical trials have been published on the combination of a long acting β2 agonist with an inhaled corticosteroid in patients with moderate to severe COPD.8,9,10,24,25 Four of these studies found that combination therapy improved lung function compared with either component alone.8,9,10,24-25 The additive effect on FEV1 of the combination over the monoproducts in one of these trials is illustrated in figure 3.24 Additive effects of treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid or long acting anticholinergic and a long acting β2 agonist over those of both monocomponents for other outcomes were less consistent: two studies showed additive effects for improvement in health status8,10 and for reduction in dyspnoea,8,24 and one study each for a decrease in rescue use of a β2 agonist24 and for improvement in exacerbations.10

Fig 3.

Mean change in pre-dose (trough) forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after administration of placebo, fluticasone 500 μg twice a day, salmeterol 50 μg twice a day, or the combination10

Implementing treatment

The GOLD, ATS/ERS, NICE, and Canadian Thoracic Society guidelines provide general approaches to the implementation of inhaled therapy to treat COPD.2 We have proposed a more explicit algorithm (fig 1).13 For practising clinicians, however, therapeutic choices are rarely so clear. To help decision making, we have developed short case scenarios that illustrate the implementation of an evidence based treatment algorithm.

Case 1: A 47 year old man presenting for a routine history and physical examination

Initially the patient had no complaints, but then he admitted that for the past few months he had noticed a morning cough productive of a little clear sputum. He denied breathlessness but, when asked if he engaged in any vigorous physical activity, he said he was a little more short of breath than earlier in life. He has never taken regular medication. He started smoking at the age of 15 and quickly built up to a pack per day, which he continued until his 40th birthday. Because of his smoking history the patient had a spirometry test. FEV1 was normal at 82% of predicted, but the ratio of FEV1 to FVC was 67% (GOLD stage I). The clinical stage is “intermittent symptoms” (fig 1).

Management: Salbutamol or albuterol and ipratropium (Combivent), administered by metered dose inhaler, can be prescribed on an “as needed” basis—for example, with physical activity. The patient can be anticipated to use the inhaler every few days. He should be encouraged to maintain a healthy level of physical activity and should remain relatively stable for about five years.

Case 2: A 52 year old woman with shortness of breath on exertion and occasional productive cough

The patient is inclined to downplay her symptoms but has apparently modified her lifestyle to compensate for them. She was given a salbutamol metered dose inhaler, which she used occasionally to begin with, but now she takes at least two puffs every day. Her FEV1 is mildly reduced at 78% predicted, as is her FEV1:FVC ratio, at 67% (GOLD stage II). She has never been admitted to hospital with respiratory problems. The stage is “persistent symptoms” (fig 1).

Management: Maintenance therapy should be introduced with a long acting bronchodilator, such as tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day; salmeterol dry powder inhaler, 50 μg twice a day; or formoterol dry powder inhaler, 12 μg twice a day. The patient's need for salbutamol should lessen.

Case 3: A 56 year old man with symptoms of COPD who has been taking albuterol and ipratropium metered dose inhaler, two puffs four times per day, for about three years

The patient complains of daily intermittent wheezing and chest tightness. He is short of breath when climbing hills and is now able to play only nine holes of golf. His ratio of FEV1 to FVC is 57%, and his FEV1 is 65% of predicted (GOLD stage II). The clinical stage is again “persistent symptoms” (fig 1).

Management: Tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day, can be substituted for the albuterol and ipratropium metered dose inhaler, with the provision of a salbutamol metered dose inhaler for use as needed. After an interval of adjustment, the patient's requirement for salbutamol should be assessed to determine whether a prolonged action (12 hour) inhaled β2 agonist is needed twice daily in addition to the long acting (24 hour) anticholinergic bronchodilator once daily.

Case 4: A 63 year old man who has known that he has COPD for 10 years

The patient's illness has been characterised by productive cough during the winter, but he has never been admitted to hospital. Four months ago he began using tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day, and his symptoms improved. However, lately he has experienced intermittent chest tightness and wheezing, which have been particularly troublesome at night. These symptoms have required him to use a salbutamol metered dose inhaler up to five times during the day and also when he has woken up at night. His ratio of FEV1 to FVC was 48%, and his FEV1 was 47% of predicted (GOLD stage III). The clinical stage is again “persistent symptoms” despite long acting monotherapy (fig 1 and summary).

Management: Tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day, should be continued. A β2-agonist with prolonged action (salmeterol dry powder inhaler, 50 μg twice a day, or formoterol dry powder inhaler, 12 μg twice a day) should be added to optimise bronchodilation. The patient's intermittent chest tightness and wheezing should diminish, thereby decreasing the need for rescue therapy with a short acting β2 agonist. The patient should be referred to a pulmonary rehabilitation programme.

Case 5: A 65 year old woman with COPD has visited her general practitioner every few months, asking for a course of antibiotics

About two years ago the patient was prescribed tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day, and formoterol dry powder inhaler, 18 μg twice a day. On this regimen, she remained clinically stable, and her exercise performance improved with attendance at a pulmonary rehabilitation programme. During the past eight months she has visited her general practitioner three times with worse breathlessness and cough productive of yellow sputum. The clinical stage is “frequent exacerbations” (fig 1).

Management: An inhaled corticosteroid should be added, such as fluticasone metered dose inhaler, 500 μg (two puffs) twice a day, or budesonide dry powder inhaler, 400 μg (two inhalations) twice a day. Alternatively, a single dry powder inhaler can administer 50 μg of salmeterol per inhalation in combination with 250 μg or 500 μg of fluticasone per inhalation.

Case 6: A 68 year old man with debilitating COPD has noticed ankle swelling over the past few weeks

The patient has experienced exacerbations, which have been treated with tapering courses of oral prednisone, and he continues to take prednisone 10 mg once a day. His ankle oedema has been treated with hydrochlorothiazide. His ratio of FEV1 to FVC is 40%, and his FEV1 is 28% of predicted (GOLD stage IV). He has been using supplemental oxygen at night, prescribed based on an arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) of 56 mm Hg (breathing room air) and the presence of peripheral oedema. Inhaled medications consist of tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day, and salmeterol dry powder inhaler, 50 μg twice a day. The clinical stage is “respiratory failure” (fig 1).

Additional educational resources

For doctors

COPD diagnosis, management, and prevention

World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (www.goldcopd.com)

Inhaled corticosteroids

Alsaeedi A, Sin DD, McAlister FA. The effects of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Am J Med 2002;113: 59-65

Sutherland ER, Allmers H, Ayas NT, Venn AJ, Martin RJ. Inhaled corticosteroids reduce the progression of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Thorax 2003;58: 937-41

Bronchodilator therapy

Barnes PJ. Therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Ther 2003;97: 87-94

Tashkin DP, Cooper CB. The role of bronchodilators in the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 2004;125: 249-59

For patients

The European Network of COPD Patient Associations (ENCPA; www.efanet.org) can put patients in contact with their local patient support group. EFA Central Office, Avenue Louise 327, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium (tel 0032 (0) 2 6469945; fax 0032 (0) 2 6464116; EFAOffice@skynet.be

COPD International. Volunteer organisation specialising in online support (www.copd-international.com)

Management: An inhaled corticosteroid should be introduced (such as fluticasone metered dose inhaler, 500 μg (two puffs) twice a day, or budesonide dry powder inhaler, 400 μg (two inhalations) twice a day). Alternatively, a single dry powder inhaler device can administer 50 μg of salmeterol per inhalation in combination with 250 μg or 500 μg of fluticasone per inhalation. An attempt should be made to wean off prednisone over six weeks. A portable oxygen delivery system should be provided for use by ambulatory patients outside the home, and the patient should be referred for pulmonary rehabilitation.

Case 7: A 62 year old woman with a 25 pack year smoking history, who quit smoking at 50 and had “wheezy bronchitis” as a child and lifelong hay fever

The patient's son has asthma. She presented six weeks earlier with worsening symptoms, and her FEV1 was 0.77 l (32% predicted). She was given oral prednisone, tapering from 40 mg once a day to 20 mg once a day. Re-evaluation of her pulmonary function now shows her FEV1:FVC ratio to be 35% and her FEV1 to be 1.03 l (43% predicted), increasing to 1.25 l (+22%) after an inhaled bronchodilator. Her regular inhaled medications consist of tiotropium dry powder inhaler, 18 μg once a day, and formoterol, 12 μg twice a day. This patient has asthma and smoking related COPD.

Management: An inhaled corticosteroid should be introduced (such as fluticasone metered dose inhaler, 500 μg (two puffs) twice a day, or budesonide dry powder inhaler, 400 μg (two inhalations twice a day). If budesonide is used, it can be combined in a single dry powder inhaler with formoterol (12 μg twice a day). She should be weaned off prednisone over two weeks.

Conclusions

Clinical guidelines provide a useful reference for practising clinicians. However, they are often long, not easily approachable, and therefore underused. The sample case summaries presented here and the treatment flow chart in figure 1 provide a basis for the practical implementation of current guidelines and more recent clinical trial evidence.

Supplementary Material

Additional references w1-w18 are on bmj.com

Additional references w1-w18 are on bmj.com

Contributors: This review is a combined effort on the part of the two authors. CBC wrote the case examples.

Competing interests: CBC has been a consultant and speaker for Biotechnology General Corp, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and VIASYS Healthcare. He is a member of the scientific advisory board of Boehringer Ingelheim/Pfizer for tiotropium related questions. He has also received research grants from Biotechnology General Corp, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, ONO Pharma, and Pfizer. DPT has been a consultant and speaker for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, and he has received research grants from Altana, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer.

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet 2003;362: 847-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Bethesda, MD: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, World Health Organization, 2003. www.goldcopd.com/2004clean.pdf (accessed 19 Jan 2005).

- 3.Celli BR, MacNee W, and committee members. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23: 932-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2004;59: 1-232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Marciniuk D, Balter M, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2003. Can Respir J 2003;10(suppl A): 11A-65A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey SD. Suboptimal medical therapy in COPD: exploring the causes and consequences. Chest 2000;117: 33S-7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brusasco V, Hodder R, Miravitlles M, Lee A, Towse LJ, Kesten S. Health outcomes in a 6-month placebo controlled trial of once-daily tiotropium compared with twice-daily salmeterol in patients with COPD. Thorax 2003;58: 399-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szafranski W, Cukier A, Ramirez A, Menga G, Sansores R, Nahabedian S, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive disease. Eur Respir J 2003;21: 74-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahler DA, Wire P, Horstman D, Chang CN, Yates J, Fischer T, et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination delivered via the diskus device in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166: 1084-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, Jones P, Pride N, Gulsvik A, et al. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361: 449-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rennard SI, Serby CW, Ghafouri M, Johnson PA, Friedman M. Extended therapy with ipratropium is associated with improved lung function in patients with COPD. A retrospective analysis of data from seven clinical trials. Chest 1996;110: 62-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liesker JJW, Wijkstra PJ, Ten Hacken NHT, Koeter GH, Postma DS, Kerstjens HAM. A systematic review of the effects of bronchodilators on exercise capacity in patients with COPD. Chest 2002;121: 597-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashkin DP, Cooper CB. The role of long-acting bronchodilators in the management of stable COPD. Chest 2004;125: 249-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donohue JF, Menjoge S, Kesten S. Tolerance to bronchodilating effects of salmeterol in COPD. Respir Med 2003;97: 1014-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celli B, ZuWallack R, Wang S, Kesten S. Improvement in resting inspiratory capacity and hyperinflation with tiotropium in COPD patients with increased static lung volumes. Chest 2003;124: 1743-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hattotuwa KL, Gizycki MJ, Ansari TW, Jeffery PK, Barnes NC. The effects of inhaled fluticasone on airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled biopsy study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165: 1592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsaeedi A, Sin DD, McAlister FA. The effects of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Am J Med 2002;2002: 59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutherland ER, Allmers H, Ayas NT, Venn AJ, Martin RJ. Inhaled corticosteroids reduce the progression of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Thorax 2003;58: 937-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Highland KB, Strange C, Heffner JE. Long-term effects of inhaled corticosteroids on FEV1 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138: 969-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipworth BJ. Systemic adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroid therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 1999;159: 941-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Noord JA, de Munck DRAJ, Bantje T, Hop WCJ, Akveld MLM, Bommer AM. Long-term treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with salmeterol and the additive effect of ipratropium. Eur Respir J 2000;15: 878-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennant RC, Erin EM, Barnes PJ, Hansel TT. Long-acting beta 2-adrenoceptor agonists or tiotropium bromide for patients with COPD: is combination therapy justified? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2003;3: 270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cazzola M, Marco FD, Santus P, Boveri B, Verga M, Matera MG, et al. The pharmacodynamic effects of single inhaled doses of formoterol, tiotropium and their combination in patients with COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2004;17: 35-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanania NA, Darken P, Horstman D, Reisner C, Lee B, Davis S, et al. The efficacy and safety of fluticasone propionate (250 microg)/salmeterol (50 microg) combined in the Diskus inhaler for the treatment of COPD. Chest 2003;124: 834-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calverley PM, Boonsawat W, Cseke Z, Zhong N, Peterson S, Olsson H. Maintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2003;22: 912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.