Abstract

Research has implicated religious activity as a health determinant, but questions remain, including whether associations persist in places where Judeo-Christian religions are not the majority; whether public versus private religious expressions have equivalent impacts, and the precise advantage expressed as years of life. This article addresses these issues in Taiwan. 3,739 Taiwanese aged 53+ were surveyed in 1999, 2003, and 2007. Mortality and disability were recorded. Religious activities in public and private settings were measured at baseline. Multistate life-tables produced estimates of total life expectancy and activity of daily living (ADL) disability-free life expectancy across levels of public and private religious activity. There is a consistent positive gradient between religious activity and expectancy with greater activity related to longer life and more years without disability. Life and ADL disability-free life expectancies for those with no religious affiliation fit in between the lowest and highest religious activity groups. Results corroborate evidence in the West. Mechanisms that intervene may be similar in Eastern religions despite differences in the ways in which popular religions are practiced. Results for those with no affiliation suggest benefits of religion can be accrued in alternate ways.

Keywords: Religion, Disability, Life expectancy, Activities of daily living, Asia, Multistate life-tables

Introduction

Over the last couple of decades there has been growing interest in the link between religious activity and health outcomes, and for good reason. Religious activity has been empirically linked to an array of attributes that impact upon health outcomes, such as personal values, locus of control, feelings of self, health related behaviors, intergenerational associations, and coping mechanisms (Ellison and Levin 1998; Gillum 2006; Hill et al. 2007; Hummer et al. 1999, 2004; Iwasaki et al. 2002; Krause 2004, 2002; Krause et al. 2002; Lawler-Row and Elliott 2009; Obisesan et al. 2006; Ryan and Willits 2007; Strawbridge et al. 2001). This research has provided good evidence that strong religious convictions, especially when combined with frequent attendance of religious services, results in longer and functionally healthier lives (Chida et al. 2009; Gillum et al. 2008; Hummer et al. 1999; Helm et al. 2000; Hill et al. 2005; Idler and Kasl 1997; Kelley-Moore and Ferraro 2001; Koenig et al. 1999; Krause et al. 1999; La Cour et al. 2006; Oman and Reed 1998; Roff et al. 2006; Strawbridge et al. 1997; Yeager et al. 2006; Zhang 2008).

One sentiment expressed throughout much of this research is that mechanisms that link religious activity and health conform to psycho-social characteristics that operate to increase the size and functionality of one’s social network, which results in the provision and strengthening of received and perceived social support. This seems logical within the Western Judeo-Christian religious milieu that encourages physical attendance at places of worship, which in turn generates networks of individuals that participate collectively in activities taking place not only within but around the peripheral environment of the place of worship. The link may not, however, be as robust when it comes to religions that tend to be more focused on individualistic and meditative pursuits. Many activities related to these types of religions are conducted alone. Yet, research has also suggested other ways in which religion can influence health outcomes for those that follow these religions. Some religious activity can, for instance, relieve existential anxieties, provide direction when dealing with demanding and stressful situations and decision making, and offer reflective opportunities that can positively impact on emotional health.

The above suggests a number of unanswered questions in the religion-health discourse. First, with a few notable exceptions, research has been undertaken within western countries that have strong Judeo-Christian traditions and fewer studies have considered Asian settings (Krause et al. 2002, 1999; Yeager et al. 2006; Zeng et al. 2010). Not much is known about whether and to what extent links persist within and across boundaries that are characterized by different belief and value systems and different ways of expressing religious conviction. An Asian-based religion such as Buddhism, for instance, tends to be organized around individualistic reflective principles and practices that less frequently involve structured social pursuits in comparison to most western-based religions (Batchelor 1987; Lutz et al. 2008). It is true that Buddhists do engage in collective rituals, such as chanting, and do visit temples with family members during specific festivals. But, much more so than in western traditions, visitors to the temple tend to engage in unaccompanied activities that promote meditative absorption, which in Buddhism is viewed as an attempt to cultivate a state of mindfulness or heightened awareness. Indeed, a great deal of the practice for frequent visitors takes place solo and in silence. Thus, the supportive types of benefits that are gained through socially based practices may not be as robust. Second, while religious attendance and activities that take place within group settings has been well studied, less is understood about health impacts of private types of activities such as those that take place in the home or in silence. Third, while it has been shown that religion has a favorable impact on mortality and physical functioning, particularly in old-age, estimated effects expressed in years of life are difficult to specify without adequate panel data able to measure demographic outcomes such as mortality.

Using the case of Taiwan, a society dominated by Buddhist and Taoist religions, and a longitudinal panel aged 53 and older, we report life expectancies and activities of daily living (ADL) disability-free life expectancies across levels of private and public religious practice. Both Buddhism and Taoism, the majority religions in Taiwan, involve personal types of practices and are often described as being less focused on public meetings and interpersonal associations than most western-based religions. At the same time, both traditions involve other activities that take place in a public setting. For instance, Buddhists seek to “make merit” by donating to the local temple or doing other charitable activities, and they also are frequently involved in group-based chanting, observing festivals, and at times group-based meditation. Taoism emphasizes values of compassion, moderation, and humility, but it is also socially ritualistic and replete with festivals often attended at temples by entire families (Maspero 1981; Robinet and Brooks 1997).

Methods

Data are from three waves of a panel survey called “The Survey of Health and Living Status of the Middle Aged and Elderly in Taiwan.” It began in 1989 by the Taiwan Provincial Institute of Family Planning (which later became the Bureau of Health Promotion of the Taiwan Department of Health) and the University of Michigan, with support from the Taiwan government and the US National Institute on Aging. There were approximately 4,000 respondents, and these were representative of Taiwan’s population aged 60 and over and living in both community and old-age institutions. The survey included questions on a range of subjects including functional status, socio-demographic and economic characteristics, and other topics relevance to social determinants of health. Surveys took place in the home of respondents and were conducted by trained interviewers. Surviving members of the 1989 cohort were re-interviewed in 1993, 1996, 1999, 2003, and 2007. A second cohort aged 50–67 was added in 1996 to expand the age range of the survey. This cohort was sampled with a different sampling ratio than the first, so a weight is included to ensure that all surveys are representative of the population and this weight is used in all analyses to follow. Survivors of the added cohort were also re-interviewed in subsequent waves. Response rates for all years are high, about 90 %. Detailed information about this survey can be found in several key and related publications (Chang and Hermalin 1989; Hermalin 2002; Yeager et al. 2006; Zimmer et al. 2005).

This current analysis uses the 1999 wave as the baseline because it is the first survey in the set to include questions on religiosity. ‘”Mainlanders,” who are military personnel and their families that moved from Mainland China to Taiwan in the 1940s during or after the Chinese revolution, constitute 700 of the 1999 sample. They are removed from this analysis because they have an unusual set of characteristics that can bias results; for instance, they are predominantly unmarried men who have held government jobs and have subsequently had better than average health insurance and better than average health throughout their lives. Being all from Mainland China they are also somewhat homogeneous in religious activity. The total N is 3,739 (1,951 women, mean age 66.4; 1,788 men, mean age 66.9).

Measures

Survey administrators recorded wave-to-wave mortality by referencing the Taiwan Death Registry. Mortality information is thus complete. But, to assure representativeness with respect to mortality, we compared sample life expectancy at age 55 with that published by the Taiwan Directorate General for Accounting and Statistics. It is exactly the same for women (26.8 years) and slightly lower for men (22.9 vs. 23.5). The latter is expected given that our sample omitted Mainlanders who tend to be men that live longer than other Taiwanese men.

We measure disability according to ADLs (Katz et al. 1983). Those who are categorized as ADL disability-free for a particular wave report, on that survey, that they have no difficulty conducting any of the following by themselves, with no help from devices: bathing, dressing and undressing, eating, getting out of bed, standing up or sitting in a chair, moving about inside the house, and going to the toilet. Those categorized as ADL disabled report that they have difficulty with one or more of these activities.

Two survey questions are used to assess level of religious activity at baseline. The first is an indicator of private activity and asks about the frequency with which an individual prays, burns incense, worships gods or the Buddha at home. The second is an indicator of public activity and asks the frequency with which an individual goes to temple or church for worship. Possible responses were often, sometimes, rarely or never. Prior to these two questions the survey included a filter on religious affiliation. Fifty percent reported being Taoist, 28 % being Buddhist, and 8 % reported other affiliations. Fifteen percent reported no affiliation. Those with no affiliation were not asked the two questions on religious activity. Therefore, a fifth category of no affiliation is included in the analysis.

Analysis

Estimates of life expectancy and ADL disability-free life expectancy are obtained using a multistate life-table technique. The life-table is a standard tool for summarizing the occurrence of events. It is traditionally thought of as a method for studying death and in turn life expectancy, but is equally effective for examining the occurrence of other events such as disability, marriage, or employment. In a multistate life-table, there are more than two possible events being monitored, for instance, becoming unhealthy and dying. The information that needs to be inputted into the life-table is the probability of an event occurring or, put another way, of making a transition from one state to another over a specific period of time. The information that the multistate life-table outputs includes estimated years an individual with a given set of characteristics can expect to live in a particular state.

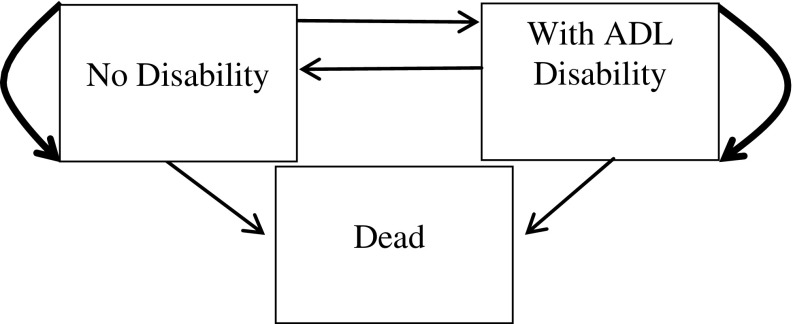

For this study, the transition probabilities considered are between ADL disability states from waves 1999 to 2003 and 2003 to 2007. A 1999 to 2007 period is used for a small number who were missing in 2003 but re-entered the survey in 2007. At baseline, the states are with and without one or more ADL disability. The follow-up states are with and without one or more ADL disability and being deceased. Figure 1 illustrates these, with each arrow representing one of the six possible transitions. Each transition has a probability associated with it for a person with a given set of characteristics, and the three probabilities from each originating state to the three follow-up states equal 1.0. The characteristics we use in this study to differentiate the transition probabilities are age, sex, and religiosity.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of multistate life-table transitions

The software used to compute the multistate life-table is the Interpolated Markov Chain (IMaCh) program (Brouard and Lievre 2002; Lievre et al. 2003). It was developed by Brouard and colleagues based on methods for analyzing life and healthy life expectancy introduced by Laditka and Wolf (1998). The IMaCh software calculates total life and ADL disability-free life expectancies by first estimating the transition probabilities using a multinomial logistic regression approach. Separate equations are estimated for private (home) and public (temple or church) religious activity. For each equation, we tested the significance of the multinomial model by comparing log-likelihoods with and without the religiosity variables, and in both cases the tests showed the equations to be highly significant (results not shown).

Lievre et al. (2003) detail the IMaCh approach. The method has become increasingly popular for analyzing disparities in population health because of the ease of interpreting life expectancies as opposed to coefficients, and their direct application to policy (Crimmins et al. 2009; Jagger et al. 2007; Kaneda et al. 2005; Reynolds et al. 2005; Yong and Saito 2012). Our data include persons aged 53 and older; however, for presentation purposes, life and ADL disability-free life expectancy estimates are shown for men and women with varying levels of religious activity at ages 55, 65, 75, and 85. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are reported for each estimate, which provides an indication of whether an estimate based on a particular level of religious activity is significantly different from the estimate based on a different level of activity. A conservative approach to basing significance is assessing whether 95 % confidence intervals bounding two estimates overlap; however, a more liberal approach is often used, which assesses whether a 95 % confidence interval bounding one estimate includes the value of another. We will refer to the more conservative method in the “Results” section that follows to provide the greatest level of support for the existence of an association.

Results

Table 1 shows transition probabilities derived from the raw data for periods 1999–2003 and 2003–2007. A greater number of individuals begin each period without one or more ADL disability. The probability of remaining without ADL disability is high for the group that begins disability-free, greater than 0.8 for both men and women across waves. The probability of dying for those disability-free at baseline is low, but it is a little higher for men (0.126 and 0.132) than for women (0.077). For those with at least one ADL disability at baseline, there is a small chance of recovery (between .128 and .176 depending on sex and wave). Those with ADL disability at baseline are more likely to die prior to follow-up than those without. This probability is higher for men (0.642 and 0.627) than women (0.495 and 0.434).

Table 1.

Transition probabilities by ADL disability at baseline, sex, and survey wave

| Baseline ADL disability status | Follow-up ADL disability status | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2003 | 2003–2007 | 1999–2003 | 2003–2007 | ||

| None | (N = 1,588) | (N = 1,207) | (N = 1,663) | (N = 1,300) | |

| None | .828 | .823 | .845 | .827 | |

| One or more | .047 | .045 | .078 | .096 | |

| Died | .126 | .132 | .077 | .077 | |

| Total | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| One or more | (N = 136) | (N = 117) | (N = 210) | (N = 229) | |

| None | .148 | .128 | .176 | .142 | |

| One or more | .210 | .245 | .329 | .424 | |

| Died | .642 | .627 | .495 | .434 | |

| Total | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

Table 2 describes the religious activity of males and females from the 1999 survey. Females are slightly more likely to report higher levels of religious activity and a slightly lower percentage of females report no affiliation. For both males and females, activity level is higher in private than in public religious practice.

Table 2.

Distribution of religious activity by sex at baseline

| Males (N = 1,788) | Females (N = 1,951) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |

| Often (%) | 16.8 | 50.1 | 22.3 | 59.6 |

| Sometimes | 40.4 | 16.9 | 39.3 | 14.0 |

| Rarely | 20.8 | 12.6 | 19.9 | 9.3 |

| Never | 10.8 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 9.1 |

| No affiliation | 11.2 | 11.2 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table 3 displays estimates for total and ADL disability-free life expectancies by level of activity in public religious practice as well as 95 % confidence intervals. Estimates are provided by sex for four specific mid-decade ages. The results of the upper panel here are typical of all results. That is, there is a consistent gradient in both total and ADL disability-free life expectancy by level of religious activity, with the greater the level of activity, the greater the number of years spent without an ADL disability and alive at each age. For instance, at age 55, males who report their level of public religious activity is often (meaning they often go to their place of worship) can expect to live 24.3 more years. They live 23.7 years if they go sometimes, 22.3 years if rarely, and 21.0 years if never. Thus, the never group is estimated to live 3.3 fewer years than the often group. With respect to ADL disability-free life, there is also a clear gradient. At age 55, the often group lives 22.7 more years without an ADL disability. This compares to 22.0, 20.6, and 19.4 sequentially for the sometimes, rarely, and never groups.

Table 3.

Total and ADL disability-free life expectancy by level of public religious activity, sex, and selected ages, with 95 % confidence intervals in parentheses

| Level of religious activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | No affiliation | |

| Males | |||||

| N | 896 | 302 | 225 | 164 | 200 |

| Total life expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 24.3 (22.7–25.9) | 23.7 (22.5–24.8) | 22.3 (20.9–23.7) | 21.0 (19.1–22.8) | 22.5 (20.4–24.6) |

| Age 65 | 16.2 (14.9–17.5) | 15.7 (14.7–16.7) | 14.5 (13.4–15.6) | 13.4 (12.0–14.9)* | 14.6 (13.0–16.1) |

| Age 75 | 9.6 (8.6–10.7) | 9.3 (8.5–10.1) | 8.4 (7.6–9.2) | 7.7 (6.7–8.7) | 8.5 (7.4–9.6) |

| Age 85 | 5.2 (4.4–5.9) | 5.0 (4.4–5.6) | 4.4 (3.9–5.0) | 4.1 (3.5–4.7) | 4.5 (3.8–5.2) |

| ADL disability-free expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 22.7 (21.2–24.1) | 22.0 (20.9–23.0) | 20.6 (19.3–21.9) | 19.4 (17.6–21.1)* | 20.9 (19.1–22.7) |

| Age 65 | 14.5 (13.3–15.8) | 14.0 (13.1–14.9) | 12.8 (11.8–13.8) | 11.9 (10.5–13.3)* | 13.1 (11.7–14.6) |

| Age 75 | 8.0 (7.1–8.9) | 7.7 (6.9–8.4) | 6.8 (6.0–7.6) | 6.2 (5.3–7.2) | 7.1 (6.0–8.2) |

| Age 85 | 3.6 (2.9–4.3) | 3.4 (2.9–4.0) | 2.9 (2.4–3.5) | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 3.2 (2.4–3.9) |

| Females | |||||

| N | 1,157 | 273 | 181 | 178 | 162 |

| Total life expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 28.4 (26.6–30.1) | 27.4 (26.1–28.8) | 25.9 (24.5–27.4) | 24.4 (22.7–26.1)* | 26.1 (22.8–29.3) |

| Age 65 | 19.6 (17.9–21.2) | 18.8 (17.6–20.0) | 17.4 (16.2–18.7) | 16.2 (14.8–17.6)* | 17.3 (15.4–19.3) |

| Age 75 | 12.1 (10.6–13.6) | 11.5 (10.4–12.6) | 10.4 (9.4–11.5) | 9.6 (8.5–10.6)* | 10.3 (8.9–11.7) |

| Age 85 | 6.7 (5.5–7.9) | 6.4 (5.5–7.3) | 5.7 (4.9–6.5) | 5.2 (4.5–6.0) | 5.6 (4.6–6.6) |

| ADL disability-free expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 24.5 (23.1–25.9) | 23.3 (22.2–24.4) | 22.0 (20.6–23.3) | 20.6 (18.8–22.4)* | 22.1 (19.9–24.2) |

| Age 65 | 15.8 (14.5–17.1) | 14.7 (13.7–15.7) | 13.5 (12.4–14.7) | 12.4 (10.9–14.0)* | 13.7 (11.9–15.4) |

| Age 75 | 8.5 (7.4–9.5) | 7.7 (6.8–8.5) | 6.8 (5.9–7.7) | 6.1 (4.9–7.3)* | 7.0 (5.6–8.4) |

| Age 85 | 3.4 (2.6–4.2) | 3.0 (2.4–3.6) | 2.5 (1.9–3.1) | 2.2 (1.4–2.9) | 2.7 (1.8–3.7) |

* Statistical significance comparing the “never” group with the “often” group using the following criteria: confidence intervals bounding the “never” group do not overlap with confidence intervals bounding the “often” group

Those with no affiliation come out consistently in the middle of the four religious activity levels. For instance, males at age 55 with no religious affiliation are expected to live 22.5 years, somewhere between the sometimes and the rarely group and almost exactly midway between the top and bottom estimates. With respect to ADL disability-free life expectancy, they are expected to live 20.9 years without a disability, again between the sometimes and rarely groups.

Years of life and ADL disability-free life decline with age while gradients remain clear. Women live longer overall and there is an even sharper gradient, with life expectancy at age 55 being 28.4, 27.4, 25.9, and 24.4 for the often, sometimes, rarely, and never religious activity levels. The total estimated difference between often and never is 4 years of life. Those with no affiliation are again approximately halfway between highest and lowest estimates with a life expectancy of 26.1.

Table 4 shows total and ADL disability-free life expectancies by level of private religious activity and sex at ages 55, 65, 75, and 85. Interestingly, despite representing a very different set of activities, similar gradients are found. Taking 85-year-old women as the example, life expectancy is estimated to be 6.3 years for those who practice privately often, 6.2 for the sometimes group, 5.5 for rarely, and 5.1 for never. Therefore, an 85-year-old woman who practices often is estimated to live 1.2 years longer than her counterpart who practices never. The estimate is 5.9 for those with no affiliation.

Table 4.

Total and ADL disability-free life expectancy by level of private religious activity, sex and selected ages, with 95 % confidence intervals in parentheses

| Level of religious activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | No affiliation | |

| Males | |||||

| N | 300 | 722 | 372 | 193 | 200 |

| Total life expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 23.8 (22.8–24.9) | 22.8 (21.2–24.4) | 22.1 (20.3–23.8) | 21.6 (19.6–23.7) | 22.7 (20.9–24.4) |

| Age 65 | 15.8 (14.9–16.6) | 14.9 (13.6–16.2) | 14.2 (12.8–15.6) | 14.0 (12.3–15.6) | 14.3 (12.9–15.8) |

| Age 75 | 9.3 (8.6–10.0) | 8.7 (7.7–9.7) | 8.2 (7.2–9.2) | 8.1 (6.9–9.2) | 7.9 (6.9–9.0) |

| Age 85 | 4.9 (4.4–5.5) | 4.6 (4.0–5.3) | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) | 4.2 (3.5–5.0) | 4.1 (3.4–4.8) |

| ADL disability-free expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 22.3 (21.3–23.2) | 21.0 (19.6–22.5) | 20.3 (18.7–21.9) | 19.9 (18.0–21.9) | 21.3 (19.7–22.9) |

| Age 65 | 14.2 (13.4–15.0) | 13.1 (11.9–14.3) | 12.5 (11.2–13.8) | 12.3 (10.8–13.9) | 13.0 (11.7–14.3) |

| Age 75 | 7.8 (7.1–8.4) | 6.9 (6.0–7.8) | 6.5 (5.5–7.4) | 6.6 (5.4–7.7) | 6.7 (5.8–7.6) |

| Age 85 | 3.5 (3.0–4.0) | 2.9 (2.3–3.6) | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 2.9 (2.1–3.6) | 3.0 (2.4–3.5) |

| Females | |||||

| N | 435 | 767 | 388 | 199 | 162 |

| Total life expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 27.6 (26.5–28.7) | 26.9 (25.1–28.7) | 25.6 (23.8–27.4) | 24.3 (22.4–26.2)* | 25.6 (23.7–27.6) |

| Age 65 | 18.9 (17.9–19.8) | 18.3 (16.6–19.9) | 17.1 (15.5–18.7) | 16.0 (14.4–17.6)* | 17.1 (15.3–18.8) |

| Age 75 | 11.5 (10.6–12.4) | 11.1 (9.7–12.5) | 10.1 (8.9–11.4) | 9.5 (8.3–10.7) | 10.3 (8.7–11.8) |

| Age 85 | 6.3 (5.6–7.1) | 6.2 (5.0–7.3) | 5.5 (4.5–6.5) | 5.1 (4.3–5.9) | 5.9 (4.6–7.3) |

| ADL disability-free expectancy | |||||

| Age 55 | 23.8 (22.8–24.7) | 22.5 (21.0–24.1) | 21.5 (19.8–23.2) | 20.3 (18.2–22.4)* | 22.6 (21.0–24.2) |

| Age 65 | 15.1 (14.3–15.9) | 14.0 (12.6–15.4) | 13.0 (11.6–14.5) | 12.2 (10.4–14.0)* | 14.2 (12.8–15.6) |

| Age 75 | 8.0 (7.2–8.7) | 7.1 (6.0–8.2) | 6.4 (5.2–7.5) | 6.0 (4.6–7.3) | 7.6 (6.5–8.7) |

| Age 85 | 3.2 (2.6–3.7) | 2.6 (1.9–3.3) | 2.3 (1.5–3.0) | 2.1 (1.3–3.0) | 3.7 (2.8–4.6) |

* Statistical significance comparing the “never” group with the “often” group using the following criteria: confidence intervals bounding the “never” group do not overlap with confidence intervals bounding the “often” group

Confidence intervals are shown in Tables 3 and 4. On balance, across ages, sexes, type of religious activity, and total versus ADL disability-free expectancy estimates, the 95 % confidence interval bounds comparing often and never religious activity either display significance or near significance. The 95 % confidence intervals that bound the no affiliation group tend to intersect other groups indicating a lack of significance. Consistency of the placement of the no affiliation estimates, being in most instances close to the middle of the high and low estimates, is nonetheless revealing.

Discussion

A growing interest in the link between religion and health in the West is advancing hand-in-hand with increasing evidence that greater levels of religious activity lead to better health outcomes. With notable exceptions there is little evidence beyond the western world, where Judeo-Christian traditions are strong, despite differences in the ways in which religion is structured (Iwasaki et al. 2002; Krause et al. 1999, 2002; Yeager et al. 2006; Zhang 2008). This study adds several important elements to our understanding of this association.

First, the religion and health association persists across cultures and different religions. The evidence for this comes from our results that, consistent with studies conducted elsewhere, show an association between religious activity and both disability-free and total life expectancy in Taiwan.

Second, the association displays a consistent gradient. Each reported higher level of religious activity means more expected years lived and more expected years lived without ADL disability. Thus, engaging in private or public activity often is more advantageous than sometimes, which is more advantageous than rarely, which is more advantageous than never.

Third, the association persists across public and private religious activity. Taiwanese elders practice more private than public religious activity, as is seen in Table 2, yet the expectancy gradients are similar for both public and private. It is reasonable to suspect that the mechanisms acting upon these associations would differ across activity types. Public activity often involves groups of individuals and may lead to the strengthening of social bonds and social support, which in turn can impact on stress and coping mechanisms. Those who practice in a place of worship may also receive benefits by walking there. Private activity does not necessarily carry the same advantages. But, there is a strong body of research coming simultaneously out of neuroscience and complementary and alternative medicine that is indicating that private meditative types of practices, which in many ways describe much Eastern religious activity, whether associated with religion or not, have beneficial effects on stress and immune function (Davidson et al. 2003; Grossman et al. 2004; Lutz et al. 2008; Majumdar et al. 2004). This would explain associations with mortality, although that such activity would also influence disability has not been investigated. Our study suggests that the meditative activities that are often centerpiece of religion as practiced in the East may be equally beneficial for an active as well as a long life.

Fourth, mechanisms beyond social support may be key explanatory factors that link religion and good health. Indeed, as noted by Krause (2002), research increasingly suggests differential pathways through which religion may promote various types of health outcomes, implying a complexity to the association that can transcend religious structures. Moreover, although Buddhism and Taoism are different than Judeo-Christian religions in a number of ways, there are also dimensions of each that are similar, and some of these dimensions relate to health outcomes. The meditative aspects involved in Buddhism may relate to the activity of prayer as practiced in other religions. Both the type of prayer that is common in western traditions and the type of meditation that is common in eastern traditions may help in reducing stress and aiding immune functions. Many religions promote good eating practices. Many also promote strong intergenerational networks and social support through the celebration of festivals and religious holidays.

Fifth, estimates for those without a religious affiliation are generally midway between the highest and lowest estimates of life and ADL disability-free life expectancy. This provides some additional implications for this study. It indicates that it is not necessary to be a religious person to be part of a group that has good health. Some of the non-affiliated could pursue other activities that result in the same benefits as those that often engage in religious activity. Being part of social groups, for instance, may have similar impacts on social support. They also may engage in meditative practices outside the context of religion. Some may also have characteristics of the non-practicing group who have an affiliation but do not receive the benefits of intervening mechanisms.

At the same time, we caution that despite a clear gradient, many of the comparisons across activity groups are not statistically significant. This, however, is true when utilizing the conservative significance test. The more liberal test, taking the point estimate for one group and examining whether it lies between the boundaries for other groups, increases the number of comparisons deemed significant. Also, while the conservative test reported in Tables 3 and 4 does not provide statistical significance across a majority of comparisons, it does indicate that the contrast of estimates for often and never groups satisfies or nearly satisfies the p < .05 criteria in many comparisons. Moreover, the gradient in the estimates, which is prominent and consistent across ages, sexes, type of religious activity, and total versus ADL disability-free expectancy estimates, provides a very salient indication that higher levels of activity are associated with more years of total and ADL disability-free life.

Besides significance, there are other caveats that should be noted. Categorization of religious engagement using terms such as “often” and “rarely” does not pinpoint a precise frequency of public and private activity. The multistate life-table technique does not lend itself very well to large numbers of covariates. Moreover, while the amount of time spent in an initial state of health, meaning the exact timing of a shift to another state of health, might influence estimates; these data do not include detailed information on the timing of shifts in health and IMaCh assumes that transitions take place in the middle of a period. Finally, the conclusions we arrive at here are not necessarily generalizable across definitions of health beyond disability, although further investigation using other measures would be informative.

The strength of this study is to indicate that expected total and ADL disability-free years of life for those who often versus never engage in public and private religious activities in Taiwan differs. Men and women that report often participating in public and private religious activity can expect between 2 and 4 more total and disability-free years at age 55 compared to their counterparts that report never participating. Those with no affiliation can expect to live more total and disability-free years than those who never engage in religious activity, but fewer than those who engage often. Significance or near significance comparing the highest and lowest levels of activity combined with the unambiguousness of the gradient lends confidence to the conclusion that frequent religious attendance associates with longer disability-free and total life expectancy.

References

- Batchelor S. The jewel in the lotus: a guide to the Buddhist traditions of Tibet. London: Wisdom Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Brouard N, Lievre A (2002) Computing health expectancies using IMaCh (a maximum likelihood computer program using interpolation of Markov Chains). Institut National d’Etudes Demographiques (INED, Paris) and EUROREVES

- Chang M-C, Hermalin AI (1989) 1989 survey of health and living status of the elderly in Taiwan: questionnaire and survey design. Comparative study of the elderly in four Asian Countries, Research Report No. 1. The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI

- Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):81–90. doi: 10.1159/000190791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Hagedorn A, Saito Y, Brouard N. Change in disability-free life expectancy for Americans 70 years old and older. Demography. 2009;46(3):627–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):564. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000077505.67574.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(6):700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum RF. Frequency of attendance at religious services, overweight, and obesity in American women and men: the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(9):655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum RF, King DE, Obisesan TO, Koenig HG. Frequency of attendance at religious services and mortality in a US national cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(2):124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm HM, Hays JC, Flint EP, Koenig HG, Blazer DG. Does private religious activity prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,851 older adults. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(7):400–405. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.M400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermalin AI. The well-being of the elderly in Asia: a four-country comparative study. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Angel JL, Ellison CG, Angel RJ. Religious attendance and mortality: an 8-year follow-up of older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(2):102–109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.S102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Ellison CG, Burdette AM, Musick MA. Religious involvement and healthy lifestyles: evidence from the survey of Texas adults. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(2):217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02872676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Nam CB, Ellison CG. Religious involvement and US adult mortality. Demography. 1999;36(2):273–285. doi: 10.2307/2648114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Ellison CG, Rogers RG, Moulton BE, Romero RR. Religious involvement and adult mortality in the United States: review and perspective. South Med J. 2004;97(12):1223–1230. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146547.03382.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl SV. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons I: cross-sectional patterns in health practices, social activities, and well-being. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(6):294–305. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52B.6.S294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sunaga R, Miyazaki H, Xiao L, Wang N, Yosiaki S, Suzuki S. Social networks and mortality based on the Komo-Ise cohort study in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1208. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger C, Matthews R, Melzer D, Matthews F, Brayne C, MRC CFAS Educational differences in the dynamics of disability incidence, recovery and mortality: findings from the MRC cognitive function and ageing study (MRC CFAS) Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(2):358–365. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda T, Zimmer Z, Tang Z. Socioeconomic status differentials in life and active life expectancy among older adults in Beijing. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(5):241–251. doi: 10.1080/09638280400006481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Branch LG, Branson MH, Papsidero JA, Beck JC, Greer DS. Active life expectancy. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(20):1218–1224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198311173092005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore JA, Ferraro KF. Functional limitations and religious service attendance in later life. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(6):365–373. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.S365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Hays JC, Larson DB, George LK, Cohen HJ, McCullough ME, Meador KG, Blazer DG. Does religious attendance prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,968 older adults. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(7):370–376. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.M370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(6):S332. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.S332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Common facets of religion, unique facets of religion, and life satisfaction among older African Americans. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(2):109–117. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ingersoll-Dayton B, Liang J, Sugisawa H. Religion, social support, and health among the Japanese elderly. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:405–421. doi: 10.2307/2676333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Liang J, Shaw BA, Sugisawa H, Kim HK, Sugihara Y. Religion, death of a loved one, and hypertension among older adults in Japan. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(2):S96. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Cour P, Avlund K, Schultz-Larsen K. Religion and survival in a secular region. A twenty year follow-up of 734 Danish adults born in 1914. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laditka SB, Wolf DA. New methods for analyzing active life expectancy. J Aging Health. 1998;10(2):214–241. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler-Row KA, Elliott J. The role of religious activity and spirituality in the health and well-being of older adults. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(1):43. doi: 10.1177/1359105308097944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievre A, Brouard N, Heathcote C. The estimation of health expectancies from cross-longitudinal surveys. Math Popul Stud. 2003;10(4):211–248. doi: 10.1080/713644739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(4):163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar M, Grossman P, Dietz-Waschkowski B, Kersig S, Walach H. Does mindfulness meditation contribute to health? Outcome evaluation of a German sample. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;8(6):719–730. doi: 10.1089/10755530260511720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maspero H. Taoism and Chinese religion. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Obisesan T, Livingston I, Trulear HD, Gillum F. Frequency of attendance at religious services, cardiovascular disease, metabolic risk factors and dietary intake in Americans: an age-stratified exploratory analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(4):435–448. doi: 10.2190/9W22-00H1-362K-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman D, Reed D. Religion and mortality among the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(10):1469. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.10.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SL, Saito Y, Crimmins EM. The impact of obesity on active life expectancy in older American men and women. Gerontologist. 2005;45:438–444. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinet I, Brooks P. Taoism: growth of a religion. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roff LL, Klemmack DL, Simon C, Cho GW, Parker MW, Koenig HG, Sawyer-Baker P, Allman RM. Functional limitations and religious service attendance among African American and white older adults. Health Soc Work. 2006;31(4):246–255. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.4.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AK, Willits FK. Family ties, physical health, and psychological well-being. J Aging Health. 2007;19(6):907. doi: 10.1177/0898264307308340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):957–961. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Cohen RD, Kaplan GA. Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(1):68–74. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DM, Glei DA, Au M, Lin H-S, Sloan RP, Weinstein M. Religious involvement and health outcomes among older persons in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2228–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong V, Saito Y. Are there educational differentials in disability and mortality transitions and active life expectancy among Japanese older adults? Findings from a 10-year prospective cohort study. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 2012;67(3):343–353. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Gu D, George LK. Association of religious participation with mortality among Chinese old adults. Res Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0164027510383584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. Religious participation and mortality risk among the oldest old in China. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 2008;63(5):293–297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.S293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z, Martin LG, Lin H-S. Determinants of old-age mortality in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]