Abstract

The aim of this study was to establish how different types of welfare states shape the context of the everyday life of older people by influencing their subjective well-being, which in turn might manifest itself in suicide rates. Twenty-two European countries studied were divided into Continental, Nordic, Island, Southern, and post-socialist countries, which were subdivided into Baltic, Slavic, and Central-Eastern groups based on their socio-political and welfare organization. Suicide rates, subjective well-being data, and objective well-being data were used as parameters of different welfare states and obtained from the World Health Organization European Mortality Database, European Social Survey, and Eurostat Database. This study revealed that the suicide rates of older people were the highest in the Baltic countries, while in the Island group, the suicide rate was the lowest. The suicide rate ratios between the age groups 65+ and 0–64 were above 1 (from 1.2 to 2.5), except for the group of the Island countries with a suicide rate ratio of 0.8. Among subjective well-being indicators, relatively high levels of life satisfaction and happiness were revealed in Continental, Nordic, and Island countries. Objective well-being indicators like old age pension, expenditure on old age, and social protection benefits in GDP were the highest in the Continental countries. The expected inverse relationship between subjective well-being indicators and suicide rates among older people was found across the 22 countries. We conclude that welfare states shape the context and exert influence on subjective well-being, and thus may lead to variations in risk of suicide at the individual level.

Keywords: Suicide of older people, Subjective well-being, Objective well-being, European welfare regimes, European Social Survey, Eurostat

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (2012), from 2000 until 2050, the world’s population aged 60 and over will more than triple from 600 million to 2 billion and more than 25 % of the European population will be 65 or older. Rapid aging worldwide challenges the existing social setting by putting additional strains on social security systems, increasing demands for health care, and the persisting negative attitudes toward older people in our society (Palmore 1999; Nelson 2004, 2005).

In most countries of the world, older people commit suicide at higher rates than any other age group (Conwell 2009), and the prevalence of suicide rates of older people varies strongly geographically (Bonnewyn et al. 2009). Within Europe, suicide rates among older people were the highest in Eastern Europe and the lowest in Southern Europe (De Leo et al. 2009).

According to research by De Leo and his colleagues, in Islands countries, the decrease of suicide rates among older people has been particularly related to increased economic security, changing attitudes toward retirement, improved social services, and better psychiatric care (De Leo 1998, 1999; De Leo and Spathonis 2003; De Leo et al. 2009). During recent years, Shah and other authors utilized the data from the WHO and the UN database to explore the correlations between suicide rates of older people and the older people’s dependency ratios, life expectancy, gross domestic product (GDP), and health care expenditure (Shah 2008, 2009; Shah et al. 2008a, b). On the basis of comparison between American states, Flavin and Radcliff (2009) conclude that more generous social welfare expenditures are associated with lower suicide rates. This suggests that the social situation of different age groups varies across countries and it could be explained by differences in cultural, political, and socio-economic context—by welfare state.

Since the ground-breaking work of Esping-Andersen (1990), the concept of welfare state has been widely applied to explain differences, from family formation issues to aspects of pension systems and social security. Esping-Andersen (1990) categorized capitalist economies into three welfare regimes: the liberal welfare states in which modest social insurance plans and benefits predominate, the conservative welfare states in which rights are attached to class and status and the preservation of status differentials predominates, and the socio-democratic welfare states in which the principles of universalism and an equality of the highest standards predominate. The categorization has been criticized, but developed further and therefore could be applied as the analytical framework. For instance, Ogg (2005) summarized the European countries with three types of welfare regimes, namely, Nordic, Mediterranean, and post-socialist. According to his analyses, the Nordic model of social protection is characterized by a high level of public services (including pensions); a Mediterranean or Southern European welfare regime with “traditional” or “familial” models of social protection strongly adheres to the ideology that the family should be the main provider of care, with a correspondingly low investment in state social protection; and post-socialist countries of Eastern Europe show the transition from centrally planned socialist systems, implying that “young” older people are finishing their working life in more insecure economic circumstances than their predecessors. Thus, as stated by Botev (2012), in Central and Eastern European countries, the political, economic, and social transformations affected younger and older generations differently. These countries have recently engaged in reforms common to the “transition countries” that were previously under the influence of the Soviet Union. All European countries are now facing huge demographic imbalances with decreasing working age cohorts (Esping-Andersen 2002), i.e., the older population is growing, while the young and active population is shrinking (Ogg 2005), which pressingly demands the allocation of resources for the additional expenditure burdens of aging (Esping-Andersen 2002).

Durkheim’s classic theory posits the association between elevated suicide rates and times of significant socio-economic change (Durkheim 1897/1951; Yur’yev et al. 2012) and differentiates between causes of suicide produced by circumstances of integration and regulation within society (Durkheim 1897/1951; McIntosh et al. 1994). Durkheim (1897/1951) argued that differences in suicide rates across communities should be viewed as indicators of the “health” of these societies (Flavin and Radcliff 2009). Welfare policies and the general ideological complexion of governments affect quality of life, and to some extent the suicide rate can be treated as a measure of “social health” (Flavin and Radcliff 2009).

Thus, we hypothesize that different types of welfare states shape the context of the everyday life of older people by influencing their subjective well-being, which in turn might emerge in the prevalence of suicides. The aims of this study are to (1) identify suicide rates of older people and compare these with those of a younger age group in 22 European countries; (2) examine the relationships of suicide mortality of older people with subjective and objective well-being indicators in these countries; and (3) analyze the patterns of suicide mortality of older people in the country groups based on their geographical variations and welfare models.

Methods

Data collection

Most developed-world countries have accepted the chronological age of 65 years as a definition of an older person (WHO 2013), and analysis of population aging usually involves the disaggregation of populations into the functional or chronological age groups of 0–14, 15–64, and 65 years and above, the broad assumption being that those in the middle age group are economically active, while the other two groups are not (Phillips et al. 2010).

Data of suicide rates (average of the three latest years available) of the age groups 65+ and 0–64 in 22 European countries were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) European Mortality Database (EMDB), updated in July 2012. The EMDB contains mortality-related indicators presented for the selected 67 causes or groups of causes of death by defined age groups and is widely used for international analysis, particularly for international comparisons and the assessment of the health situation and trends in European countries in an international context.

According to the Office for National Statistics Measuring National Well-being Debate website (ONS) (2011), there are two main distinct approaches to measuring well-being. Subjective well-being is an umbrella term which captures factors such as how satisfied people are with their lives, self-reported health, job satisfaction, and how happy people feel. Life satisfaction is conceived of as the cognitive component of subjective well-being, whereas other aspects, such as happiness or positive and negative emotions represent affective components of subjective well-being (Diener 1984; Diener et al. 1999; Schwarz et al. 2010). Thus, subjective well-being indicates individuals’ perceptions and impressions about their well-being and it is generally measured through survey questions. The individual’s subjective perception may diverge from the objective reality (Kahneman and Krueger 2006; Albert et al. 2010). Objective well-being is an independently observable assessment of conditions and it is based on the assumption that people have basic needs and rights, and well-being can be estimated through objective indicators which measure the extent to which these needs and rights are fulfilled. For instance, these observable indicators are GDP, life expectancy, and wealth (ONS 2011). Available data on subjective well-being indicators were used for these European countries from the fourth edition of the European Social Survey (ESS) Round 4, updated in February (2011). ESS is an academically driven social survey that aims to provide high quality data over time about changing social attitudes and values in Europe. The data and additional documentation are freely available for downloading at the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) website. Available data on objective well-being indicators were adopted from the Eurostat Database, updated in November (2012).

Indicators’ description

Four subjective well-being indicators from ESS, about health, income, life satisfaction, and happiness, were chosen for the purposes of this study.

-

A

Subjective general health (physical and mental health)—How is your health in general? (1 = very good; 5 = very bad).

-

B

Self-rated income—How do you feel about your household’s income nowadays? (1 = living comfortably on present income; 4 = finding it very difficult on present income).

-

C

Life satisfaction—How satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays? (0 = extremely dissatisfied; 10 = extremely satisfied).

-

D

Happiness—How happy would you say you are? (0 = extremely unhappy; 10 = extremely happy).

The scales of subjective general health (A) and self-rated income (B) were reversed in tables and figures of this study in order to have identical direction with other subjective well-being indicators depending on the negative or positive meaning of the indicators.

Another four objective well-being indicators from the Eurostat Database, about old age pension, expenditure on old age, old-age-dependency ratio, and social protection benefits, were chosen for further analyses.

-

E

Old age pension % of the GDP

-

F

Expenditure on old age % of the GDP

-

G

Old-age-dependency ratio—the ratio between the total number of older persons of an age when they are generally economically inactive (aged 65 and over) and the number of persons of working age (from 15 to 64)

-

H

Social protection benefits % of GDP—transfers to households, in cash or in kind, intended to relieve them of the financial burden of several risks and needs. These include disability, sickness/healthcare, old age, survivors, family/children, unemployment, housing, and social exclusion not covered elsewhere.

According to an official document from Eurostat (2011), social protection benefits specified for old age have two forms: one is cash benefits (including old age pension, anticipated old age pension, partial pension, care allowance, and other cash benefits) and the other is benefits in kind (including accommodation, assistance in carrying out daily tasks, and other benefits in kind). Old age pension as one of cash benefits includes the provision of a replacement income when the aged person retires from the labor market, the guarantee of a certain income when a person has reached a prescribed age, and the providing of goods or services specifically required by the personal or social circumstances of the older people.

In our analysis, objective well-being is assessed by four indicators, three of which are based on GDP. GDP is an aggregate measure of production equal to the sum of the gross values added of all resident institutional units engaged in production (plus any taxes, and minus any subsidies, on products not included in the value of their outputs). The sum of the final uses of goods and services (all uses except intermediate consumption) measured in purchasers’ prices, less the value of imports of goods and services, or the sum of primary incomes distributed by resident producer units (OECD 2002). We have to take into account that these indicators (E and G) more or less represent the age structure of the society; however, indicator H indicates more precisely the generosity of the welfare state.

Countries’ classification

In the present study, the selection of countries was predetermined by the availability of country data in the European Social Survey and presuming that classification of social protection systems within Europe is possible in spite of inter-country variation (Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999; Ogg 2005). Formation of the country groups in the current analysis is based on the welfare regime typology introduced by Esping-Andersen (1990) and developed further by different authors (Ferrera 1996; Bonoli and Palier 2001; Kuhnle 2001). The typology of selected countries based on welfare regimes also coincides with socio-political and geographical dimensions. The EU member states before 2004 were divided into Continental countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, France, and Germany) which can be characterized as conservative welfare type, Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland, and Norway) representing the social democratic welfare regime, Islands countries (the UK and Ireland) as the liberal type, and finally Southern European countries (Spain, Greece, and Portugal). Due to unavailability of data in the ESS, Italy was excluded from the Southern group. Denmark was excluded from the Nordic group since data on suicide rates were available till 2006. Norway was included in the Nordic group since its social protection system strongly resembles the whole Nordic welfare model, even though it is not an EU member state. As stated by Ervasti et al. (2012), the Eastern European group of countries is very heterogeneous. These countries have a joint history as members of the Soviet Bloc, but since the collapse of the Soviet Union, they started to develop in their own directions. Thus, the post-socialist European countries were geographically and socio-politically divided into Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Slavic countries (Russia, Ukraine, and Bulgaria), and Central-Eastern European countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, and Romania). Due to unavailability of data in the ESS, Belarus was excluded from the Slavic group.

Statistical analysis

Suicide rates (SR) vary yearly; therefore, the latest 3 years’ average rates per 100,000 persons of a given age group were calculated for the aged 65+ and 0–64 in each country studied in order to smooth occasional fluctuations. Ratios between suicide rates of 65+ and 0–64 were computed for each country. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to show the inter-correlations of suicide rates, objective, and subjective well-being indicators. To enable comparability of all indicators among the countries studied, average suicide rates (ASR) among the aged 65+ during the last three available years and the average scores of all the subjective (ASWBI) and the objective well-being indicators (AOWBI) were standardized for each country as follows.

Standardized SR = (ASR of each country—the mean of SR of countries as a whole)/standard deviation of SR of countries as a whole;

Standardized SWBI = (ASWBI of each country—the mean of SWBI of countries as a whole)/standard deviation of SWBI of countries as a whole;

Standardized OWBI = (AOWBI of each country—the mean of OWBI of countries as a whole)/standard deviation of OWBI of countries as a whole.

Results

The suicide rates of older people were above 25 per 100,000 in the Baltic, Slavic, and Central-Eastern country groups, while in the Islands group, the average rate was the lowest at 6.7 per 100,000. The range of suicide rate ratios between the age groups 65+ and 0–64 was from 1.2 to 2.5, except for the group of the Island countries with a suicide rate ratio at 0.8 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Suicide rates per 100,000, subjective and objective well-being data for aged 65 + in 22 European countries

| Countries | Last 3 years | Suicide rate 65+ | RR 65+ versus 0–64 | Subjective well-being | Objective well-being | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | ||||

| Baltic | 29.1 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 25.1 | 17.0 | |

| Estonia | 2008–2010 | 23.4 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 25.2 | 17.2 |

| Latvia | 2008–2010 | 27.6 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 25.8 | 15.6 |

| Lithuania | 2008–2010 | 36.4 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 24.4 | 18.2 |

| Slavic | 26.6 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 22.0 | 16.4 | |

| Ukraine | 2008–2010 | 27.0 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 4.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Russia | 2008–2010 | 31.6 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 5.4 | NA | NA | 18.0 | NA |

| Bulgaria | 2009–2011 | 21.3 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 25.9 | 16.4 |

| Central-Eastern | 27.9 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 8.4 | 22.7 | 20.1 | |

| Czech Republic | 2008–2010 | 18.9 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 21.6 | 18.9 |

| Hungary | 2007–2009 | 41.2 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 6.9 | 9.0 | 24.1 | 22.7 |

| Slovenia | 2008–2010 | 34.1 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 8.9 | 23.8 | 22.9 |

| Romania | 2008–2010 | 17.3 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 21.3 | 16.1 |

| Continental | 20.2 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 26.4 | 29.2 | |

| Belgium | 2004–2006 | 24.2 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 26.0 | 27.9 |

| Netherlands | 2008–2010 | 10.7 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 8.8 | 10.2 | 22.8 | 28.9 |

| France | 2007–2009 | 26.1 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 11.6 | 12.1 | 25.6 | 31.2 |

| Germany | 2008–2010 | 19.6 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 31.2 | 28.9 |

| Nordic | 15.9 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 9.8 | 25.3 | 27.5 | |

| Sweden | 2008–2010 | 17.0 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 12.1 | 27.7 | 30.1 |

| Finland | 2008–2010 | 18.5 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 10.0 | 25.8 | 28.2 |

| Norway | 2008–2010 | 12.1 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 22.5 | 24.1 |

| Southern | 13.2 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 10.0 | 26.8 | 25.2 | |

| Spain | 2008–2010 | 13.0 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 6.0 | 7.7 | 24.7 | 23.8 |

| Greece | 2007–2009 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 11.3 | 28.4 | 27.0 |

| Portugal | 2008–2010 | 22.5 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 27.3 | 24.8 |

| Islands | 6.7 | 0.8 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 20.8 | 26.0 | |

| UK | 2008–2010 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 24.9 | 26.8 |

| Ireland | 2008–2010 | 7.4 | 0.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 16.7 | 25.1 |

Indicators from European Social Survey (2008 year, round 4) (the scales of subjective general health and self-rated income were reversed in order to have identical direction with other subjective well-being indicators depending on the negative or positive meaning of the indicators)

A subjective general health (physical and mental health)—How is your health in general? (1 = very good; 5 = very bad)

B self-rated income—How do you feel about your household’s income nowadays? (1 = living comfortably on present income; 4 = finding it very difficult on present income)

C life satisfaction—How satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays? (0 = extremely dissatisfied; 10 = extremely satisfied)

D happiness—How happy would you say you are? (0 = extremely unhappy; 10 = extremely happy)

Indicators from EUROSTAT

E old age pension % of the GDP

F expenditure on old age % of the GDP

G old-age-dependency ratio—the ratio between the total number of older persons of an age when they are generally economically inactive (aged 65 and over) and the number of persons of working age (from 15 to 64)

H social protection benefits—transfers to households, in cash or in kind, intended to relieve them of the financial burden of several risks and needs. These include disability, sickness/healthcare, old age, survivors, family/children, unemployment, housing, and social exclusion not covered elsewhere

RR suicide rate ratio

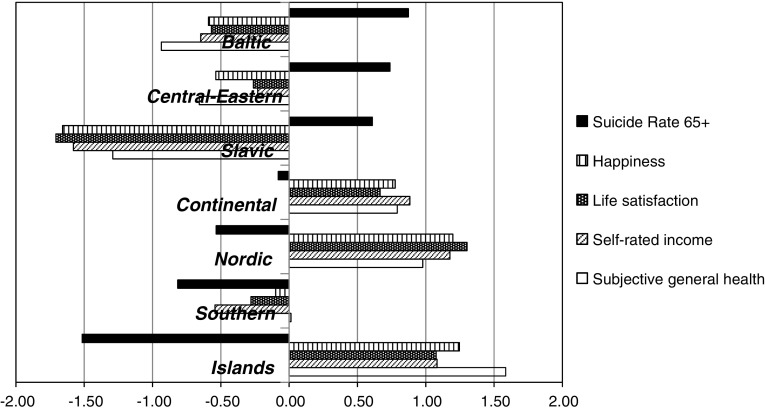

Aggregated scores about self-reported health for respondents aged over 65 were below 3 in the post-socialist countries (Baltic, Slavic, and Central-Eastern groups), while their counterparts in the Continental, Nordic, Islands, and Southern country groups had scores above 3. Scores for self-related income were low in the Slavic, Baltic, and Southern country groups and higher in the Nordic group and the Islands. In the Continental, Nordic, and Islands countries, relatively high levels of life satisfaction and happiness were revealed.

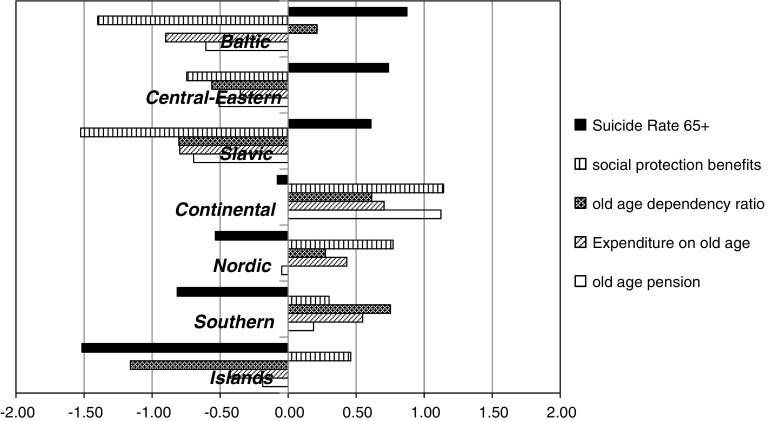

The Continental countries provided older people with the highest proportion of old age pension and expenditure on old age in GDP (9.3 and 10.3 %), followed by the Southern (7.8 and 10.0 %) and Nordic countries (7.4 and 9.8 %). The old-age-dependency ratio was the highest in the Southern countries (26.8 %) and the lowest in the Islands countries (20.8 %). The Continental countries had the highest percentage of social protection benefits (including spending on older people) of their GDP (29.2 %) and all other country groups except the Baltic and the Slavic had more than 20 % social protection benefits of their GDP.

Suicide mortality among older people in 22 countries as a whole was significantly correlated with the aggregated subjective well-being indicators, except self-rated income (Table 2). The strongest negative correlation was found between subjective general health and suicide rates (−0.72). The weakest negative correlation existed with life satisfaction (−0.51). The aggregated objective well-being indicators, however, showed no significant correlations with suicide rates. Suicide rate ratios between those aged 65+ and 0–64 were not significantly correlated with any well-being indicator, except happiness (−0.42) and old-age-dependency ratio (0.45). Furthermore, the indicator of social protection benefits was significantly correlated with all well-being indicators, except old-age-dependency ratio. The indicator of social protection benefits had the strongest positive correlation with happiness (0.75) and the weakest positive correlation with old age pension % of the GDP (0.60).

Table 2.

Correlations between suicide rates, objective and subjective well-being indicators

| Suicide rate 65+ | RR 65+ versus 0–64 | Social protection benefits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective general health aggregated | −0.72* | −0.38 | 0.74* |

| Self-rated income aggregated | −0.41 | −0.35 | 0.70* |

| Life satisfaction aggregated | −0.51* | −0.41 | 0.66* |

| Happiness aggregated | −0.56* | −0.42* | 0.75* |

| Old age pension % of the GDP | −0.04 | 0.21 | 0.60* |

| Expenditure on old age % of the GDP | −0.11 | 0.19 | 0.70* |

| Old-age-dependency ratio | −0.01 | 0.45* | 0.30 |

| Social protection benefits % of the GDP | −0.33 | −0.11 |

The scales of subjective general health and self-rated income were reversed in order to have identical direction of other subjective well-being indicators depending on the negative or positive meaning of the indicators. No available data in objective well-being indicators for Russia and Ukraine

RR suicide rate ratio

* p < 0.05

The suicide rates standardized by the overall mean and standard deviation had signs opposite to the standardized scores of subjective well-being indicators in all countries studied (that is, the higher than average standardized suicide rates were in association with the lower than average standardized scores of subjective well-being indicators in all countries studied), except in Southern European countries where suicide rates had signs identical to some of the subjective well-being indicators (lower than average). In the Central-Eastern, Slavic, Continental, and South countries, suicide rates had signs opposite to the objective well-being indicators (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Standardized suicide rates per 100,000 aged 65+ and subjective well-being by country groups. Note the scales of subjective general health and self-rated income were reversed in order to have identical direction of subjective well-being indicators depending on the negative or positive meaning of the indicators

Fig. 2.

Standardized suicide rates per 100,000 aged 65+ and objective well-being by country groups

Discussion

Worldwide demographic aging means that the absolute number of suicides by older people is likely to increase (O’Connell et al. 2004; Yur’yev et al. 2010). The results of this study showed that there was large difference in magnitude of the suicide rate ratios between the older (65+) and the younger (0–64) age groups. In the UK and Ireland, this ratio was generally close to 1:1, but in Southern Europe, the suicide rates of the older people were 2.5 times higher than those among younger persons. As stated already by De Leo (1999), suicide cases increase with the aging process much more in Southern European countries (Spain and Portugal) than in the Islands (UK and Ireland). The outcomes of this study also showed that the respondents aged over 65 reported much higher general health in the Island countries than others. Moreover, the expenditure on old age as the proportion of GDP and old age pension as the proportion of GDP were sufficient in the UK. According to Bonoli and Palier (2001), the Island countries with much lower suicide rates among the older people have welfare state developments in three key areas of social protection: unemployment compensation, old age pensions, and health care. Following Durkheim’s idea of social integration, this could be seen as a certain level of attachment of individuals to their groups (Durkheim 1897/1951; Yur’yev 2012).

In contrast, older people in Southern European countries reported a lower income level, relatively worse physical and mental health, and lower quality of life. These Southern European countries developed their own welfare state later than Northern Europe (Ferrera et al. 2001), and state social protection offered low investment (Ogg 2005), but families and voluntary organizations had more important welfare functions (Kuhnle 2001). According to the classical view of Durkheim (1897/1951) and some other authors (e.g., Yur’yev et al. 2010), the traditional family life provides the best protection against self-destructive behavior. However, with the fastest aging rate in the populations in these countries, the increasing stress on families might bring out the absence of a positive culture of aging among the older people. Negative and/or false images of aging can contribute to agism attitudes that are reflected in society and contribute to a low level of self-esteem in older people (De Mendonca Lima et al. 2001).

In the Nordic welfare model, the universalistic “people’s pension” has its roots in the social assistance tradition (Esping-Andersen 2010), and social protection is a right for all citizens, who can enjoy substantial access to free services (Bonoli and Palier 2001). Our results in this study revealed that in Nordic countries, older people reported the highest life satisfaction, the most comfortable income level, and relatively better general health among all the countries studied. Nevertheless, the suicide rates of older people were still higher, which probably stems from other risk factors, such as loneliness (Rubenowitz et al. 2001; Waern et al. 2003; Wiktorsson et al. 2010; Fässberg et al. 2012), lack of perceived social connectedness (Kjolseth et al. 2009; Fässberg et al. 2012), depression (Wasserman 1999–2000; Wasserman and Ringskog 2001), and anxiety disorders (Wasserman and Ringskog 2001). It is in line with Durkheim’s statement that suicide occurs when the individual lacks adequate integration into society and also lacks or has weak integration into the family (Durkheim 1897/1951; McIntosh et al. 1994).

In Continental European countries, the Bismarckian social insurance tradition is the strongest and social benefits are linked to payment of contributions and directly depend on employment status (Bonoli and Palier 2001). The findings from this study showed that these countries allocated larger proportions of GDP for social protection benefits and expenditure on old age than European countries under different welfare models. Nevertheless, the suicide rates of older people were still relatively high, especially in France and Belgium, which was in line with previous research that the highest suicide rates among males 65 years and over were found in some parts of Western Europe (i.e., in France) (De Leo et al. 2009). On the one hand, the Bismarckian welfare state assumed that men were working full time and that they would have long and uninterrupted careers leading up to a relatively brief retirement, in which the concept of full employment involved primarily the male breadwinners who provide support for the entire family (Palier 2010). On the other hand, the employment rate of older workers (55 years and older) is quite high in “market liberal” countries like the UK as well as in “social democratic” countries like Sweden, but low in “conservative-corporatist” countries like Germany (Esping-Andersen 1990; Tesch-Römer and Kondratowitz 2006). The Conservative model created pressures for subsidized early retirement, a strategy that reduces labor market participation, while increasing social charges and doing little to promote new employment (Ferrera et al. 2001). Yur’yev et al. (2010) indicated that suicide mortality is lower in countries where older people can continue to participate longer in employment.

With respect to these statements above, our results showed that suicide rates were higher in the Continental countries than in the Islands and Nordic countries, even though the former had higher percentages of old age pension, expenditure on old age, and social protection benefits than the latter. Moreover, older males in the Continental countries, as the previous breadwinners to support their families, had fewer chances to establish secure attachment with family and its surroundings (neighbors, friends, etc.) compared to women who were discouraged from work and stayed with children based on the Conservative model. Durkheim would have predicted an increase in suicide risk because of lessened contact with and involvement in family and other social relationships which are, by definition, aspects of social isolation (Durkheim 1897/1951; McIntosh et al. 1994). Moreover, secure attachment in late life seems to be related to less agism and a better quality of life. The enhancement of a secure attachment base in older people may assist in moderating agism and improving older people’s quality of life (Bodner and Cohen-Fridel 2010). Having a family enhances subjective well-being, and spending more time with one’s family helps even more (Helliwell and Putnam 2005). Frequent interactions with both friends and neighbors are associated with systematically higher assessments of subjective well-being (Helliwell and Putnam 2005). Therefore, the social protection systems based on the priority of males’ employment under the Conservative model to some extent might exert negative influence on the functions and roles of males in the family and social life, which may be associated with relatively high suicide rates among older males in these Continental countries.

Our studies indicated that the highest suicide rate of older people was among the post-socialist European countries, Central-Eastern European countries with the second highest suicide rates following Baltic countries. In recent decades, these countries have gone through rapid social, political, and economic changes and the increase of suicides could be seen as a response. According to Durkheim (1897/1951), during times of rapid social changes or transformations when the future is uncertain and behavioral patterns are unclear, suicide usually increases (Yur’yev 2012). Before the introduction of the central planned economy under the influence of the Soviet Union, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovenia had implemented a Bismarckian welfare state as Continental European countries. After the Soviet Union collapsed, Central and Eastern Europe encountered difficulties in restructuring a welfare system under a completely different economic and political system; more and more people were hit by unemployment and poverty, the family pattern in force during communism had to be re-discussed, and protection during old age had to be renegotiated (Cerami 2010). On the other hand, these countries’ welfare and social protection systems still maintain the legacy of centrally planned socialist systems (Ogg 2005). Older people in the rural areas of Hungary have particularly high poverty rates and former co-operative farm agricultural workers are now unemployed or retired on inadequate pensions (Szalai 1998; Ogg 2005). Slovenia had strikingly high suicide rates among older people, after Hungary. There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon. During transition, the new development and uncertainty probably scared and burdened older people who experienced difficulties in adapting to rapid social changes. This was reinforced by a negative social atmosphere because the social status of the older population in Slovenian society is generally low and is not respected (Grad et al. 2001). Nevertheless, the Czech Republic has closer similarities to Nordic Europe in living arrangements and marriage patterns (Ogg 2005) and this might contribute to explaining why the suicide rate of older people in the Czech Republic was much more in accordance with those of Nordic European countries and differed markedly from Hungary and Slovenia. Even though Romania had the lowest total suicide rate in the Central-Eastern country group as a whole, the age group 65 years and older has the highest suicide rate. Again, this may be derived from underlying social issues and relevant consequences (Cozman 2006, 2009).

The economic level of the Baltic countries is higher than that of other post-Soviet countries (Värnik and Mokhovikov 2009), but due to delays in industrialization and modernization during the 50 years under Soviet rule, these countries have shown relatively lower economic development compared to Western European countries (Aidukaite 2004). This corresponds with the findings from our study which showed relatively worse subjective and objective well-being levels with much higher suicide rates among older people in these countries. Especially Lithuania, with the second highest suicide rate among older people among all the countries studied, showed lower social protection benefits as a percentage of their GDP and lower quality of life as assessed by older people. The most common hypothesis to explain the very high rate of suicides in Lithuania lies in the long-lasting effects of the Soviet/Nazi/Soviet occupations of the 1940s and the 50 years under the communist regime, and on the inability of individuals and groups to manage psychosocial stress and environmental changes (Gailiene 2004). With abrupt changes, the equilibrium is disrupted and a state of deregulation emerges, and as a result the individual is left without clear norms to guide or regulate behavior (“anomy,” cf. Durkheim 1897/1951; McIntosh et al. 1994). Värnik and Mokhovikov (2009) pointed out that people who experienced the transition crises might have psychological reactions called “Soviet Syndromes,” such as loss of meaning of life and loss of trust in the support of society (Skrabski et al. 2003, 2005; Värnik and Mokhovikov 2009). Trust and membership are associated with increased life satisfaction and reduced suicide rates (Helliwell and Putnam 2005).

To sum up, the different types of welfare states shape and maintain the cultural, normative, and practical context in which the everyday life of individuals takes place, including suicides. Higher levels of social support may enhance social engagement and enable older people to maintain helpful roles for leading a successful later life. However, being less integrated into the society and losing roles in the course of older years, old people who do not wish to exhaust or drain economic and other resources or do not wish to be an undue burden might have suicidal behaviors as a contemporary form of altruistic suicide as proposed by Durkheim (McIntosh et al. 1994). Therefore, future research on how to promote older peoples’ well-being and in turn decrease suicide risk at the individual level should take into consideration the different European welfare regimes in connection with measures of integration.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to the editor-in-chief for providing invaluable suggestions.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Aidukaite J (2004) The emergence of the post-socialist welfare state—the case of the baltic states: Estonia Latvia and Lithuania. Dissertation: Södertörn University College

- Albert I, Labs K, Trommsdorff G. Are older adult German women satisfied with their lives? On the role of life domains, partnership status, and self-construal. GeroPsych. 2010;23(1):39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bodner E, Cohen-Fridel S. Relations between attachment styles, ageism and quality of life in late life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(8):1353–1361. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnewyn A, Shah A, Demyttenaere K. Suicidality and suicide in older people. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2009;19:271–294. doi: 10.1017/S0959259809990347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonoli G, Palier B. How do welfare states change? Institutions and their impact on the politics of welfare state reform in Western Europe. In: Leibfried S, editor. Welfare state futures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Botev N. Population ageing in Central and Eastern Europe and its demographic and social context. Eur J Ageing. 2012;9(1):69–79. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami A. The politics of social security reforms in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. In: Palier B, editor. A long goodbye to Bismarck? The politics of welfare reforms in Continental Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2010. pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y. Suicide prevention in later life: A glass half full, or half empty? Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):845–848. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozman D. Synopsis of Suicidology. Cluj-Napoca: Science Book Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cozman D. Suicide prevention in Romania. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 807–809. [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D. Is suicide prediction in old age really easier? Crisis. 1998;19(2):60–61. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.19.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D. Cultural issues in suicide and old age. Crisis. 1999;20(2):53–55. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.20.2.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D, Spathonis K. Culture and suicide in late life. Psychiatric Times. 2003;20:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D, Krysinska K, Bertolote JM, Fleischman A, Wasserman D. Suicidal behaviors on all the continents among the elderly. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 693–701. [Google Scholar]

- De Mendonca Lima CA, Bertolote JM, Simeone I, Camus V. Suicide in old age: Swiss perspectives. In: De Leo D, editor. Suicide and euthanasia in older adults: a transcultural journey. Göttingen: Hogrefe & Huber; 2001. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1984;95(3):542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide: a study in sociology. New York: Free Press; 1897–1951. [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti H, Goul Andersen J, Friberg T, Ringdal K. The future of the welfare state. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Social foundations of post-industrial economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Towards the good society, once again? In: Esping-Andersen G, Gallie D, Hemerijck A, Myles J, editors. Why we need a new welfare state? Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Prologue: What does it mean to break with Bismarck? In: Palier B, editor. A long goodbye to Bismarck? The politics of welfare reforms in Continental Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2010. pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- European Social Survey (2011) http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/. Accessed Feb 2011

- Eurostat (2011) Eurostat methodologies and working papers: the European system of integrated social protection statistics manual. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

- Eurostat Database (2012) http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/themes. Accessed Nov 2012

- Fässberg MM, van Orden KA, Duberstein P, Erlangsen A, Lapierre S, Bodner E, Canetto SS, De Leo D, Szanto K, Waern M. A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:722–745. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera M. The Southern model of wlefare in social Europe. J Eur Soc Policy. 1996;6(1):17–37. doi: 10.1177/095892879600600102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera M, Hemerijck A, Rhodes M. Recasting European welfare states for the 21st century. In: Leibfried S, editor. Welfare state futures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Flavin P, Radcliff B. Public policies and suicide rates in the American states. Soc Indic Res. 2009;90(2):195–209. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9252-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gailiene D. Suicide in Lithuania during the years of 1990–2002. Arch Suicide Res. 2004;8(4):389–395. doi: 10.1080/13811110490476806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grad OT, Kogoj A, Trontelj J. Elderly suicide in Slovenia. In: De Leo D, editor. Suicide and euthanasia in older adults: a transcultural journey. Göttingen: Hogrefe & Huber; 2001. pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell JF, Putnam RD. The social context of wellbeing. In: Huppert FA, Baylis N, Keverne B, editors. The science of wellbeing. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 435–459. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20:3–23. doi: 10.1257/089533006776526030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjolseth I, Ekeberg O, Steihaug S. “Why do they become vulnerable when faced with the challenges of old age?” Elderly people who committed suicide, described by those who knew them. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:903–912. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnle S. The Nordic welfare state in a European context: dealing with new economic and ideological challenges in the 1990s. In: Leibfried S, editor. Welfare state futures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JL, Santos JF, Hubbard RW, Overholser JC. Elder suicide: research, theory and treatment. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TD. Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TD. Ageism: prejudice against our feared future self. J Soc Issues. 2005;61(2):207–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00402.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell H, Chin AV, Cunningham C, Lawlor BA. Recent developments: suicide in older people. BMJ. 2004;329(7471):895–899. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7471.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2002) Gross domestic product (GDP). http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1163. Accessed 01 July 2002

- Office for national statistics measuring national well-being debate website (2011) http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110422103457/well-being.dxwconsult.com/2011/02/24/objective-vs-subjective-well-being/. Accessed 24 Feb 2011

- Ogg J. Social exclusion and insecurity among older Europeans: the influence of welfare regimes. Ageing Soc. 2005;25:69–90. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04002788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palier B. Ordering change: understanding the ‘Bismarckian’ welfare reform trajectory. In: Palier B, editor. A long goodbye to Bismarck? The politics of welfare reforms in Continental Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2010. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Palmore EB. Ageism: negative and positive. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J, Ajrouch K, Hillcoat-Nalletamby S. key concepts in social gerontology. London: SAGE; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenowitz E, Waern M, Wilhelmson K, Allebeck P. Life events and psychosocial factors in elderly suicides-A case–control study. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1193–1202. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz B, Albert I, Trommsdorff G, Zheng G, Shi SH, Nelwan PR. Intergenerational support and life satisfaction: a comparison of Chinese, Indonesian, and German elderly mothers. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2010;41(5–6):706–722. doi: 10.1177/0022022110372197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. A cross-national study of the relationship between elderly suicide rates and urbaninzation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(6):714–719. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. The relationship between elderly suicide rates and the human development index: a cross-national study of secondary data from the World Health Organization and the United Nations. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(1):69–77. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Bhat R, Mackenzie S, Koen C. A cross-national study of the relationship between elderly suicide rates and life expectancy and markers of socioeconomic status and health care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(2):347–360. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Padayatchi M, Das K. The relationship between elderly suicide rates and elderly dependency ratios: a cross-national study using data from the WHO data bank. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(3):596–604. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700628X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrabski A, Kopp M, Kawachi I. Social capital in a changing society: cross sectional associations with middle aged female and male mortality rates. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(2):114–119. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrabski A, Kopp M, Rozsa S, Rethelyi J, Rahe RH. Life meaning: an important correlate of health in the Hungarian population. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(2):78–85. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalai J. Poverty and social policy in Hungary in the, 1990s. In: Festschrift for ivan szelenyi at 60 years. Budapest: Rutgers Institute for Hungarian Studies; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tesch-Römer C, Kondratowitz HJv. Comparative ageing research: a flourishing field in need of theoretical cultivation. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3:155–167. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Värnik A, Mokhovikov A. Suicide during transition in the former Soviet Republics. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Wilhelmson K. Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology. 2003;49:328–334. doi: 10.1159/000071715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman D (1999–2000) Depression, a common illness. Symptoms, causes and treatment options. Hans Reitzels Förlag, Copenhagen (in Danish) and atur och Kultur, Stockholm, Sweden (in Swedish)

- Wasserman D, Ringskog S. Suicide among the elderly in Sweden. In: De Leo D, editor. Suicide and euthanasia in older adults: a transcultural journey. Göttingen: Hogrefe & Huber; 2001. pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktorsson S, Runeson B, Skoog I, Ostling S, Waern M. Attempted suicide in the elderly: characteristics of suicide attempters 70 years and older and a general population comparison group. Am J Geriatri Psychiatry. 2010;18:57–67. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1c13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2013) Definition of an older or elderly person. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/

- World Health Organization European Mortality Database (2012) http://data.euro.who.int/hfamdb/. Accessed July 2012

- Yur’yev A (2012) Dimension-specific impact of social exclusion on suicide mortality in Europe. Dissertation: Tallinn University

- Yur’yev A, Leppik L, Tooding LM, Sisask M, Värnik P, Wu J, Värnik A. Social inclusion affects elderly suicide mortality. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(8):1337–1343. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yur’yev A, Värnik A, Värnik P, Sisask M, Leppik L. Role of social welfare in European suicide prevention. Int J Soc Welf. 2012;21:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00777.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]