Abstract

The poverty rate amongst older Portuguese adults has decreased significantly in recent years as their incomes have increased and their levels of inequality and material deprivation have converged to the national average. This paper investigates whether this improved situation is homogeneous across this population group, but concludes that poverty pockets subsist. In particular, those aged 75+ and living alone record a poverty rate above 30 % in 2010, showing that this group is still subject to great economic and social vulnerability. An important feature of this income heterogeneity is the higher average income of the 65–74 age group versus the 75+ group. The evolution of both contributive and means-tested pensions has been a key element in the reduction of poverty amongst older people in Portugal and in improving their living standards. However, the austerity policies implemented post-2010 have made a strong impact on pensions and may reverse these positive developments.

Keywords: Social policy, Income distribution, Inequality, Poverty alleviation, Portugal

Introduction

The study of poverty and deprivation amongst older people in OECD and EU countries has been gaining importance due to the increasing ageing of the population at a time of economic crisis and growing pressure on resources. According to OECD (2013:13), “The reduction of old-age poverty has been one of the greatest social policy successes in OECD countries” with an average old-age poverty rate of 12.8 % (down from 15.1 % in 2007) and disposable income at about 86 % of national income in 2010, despite the recession. Moreover, both monetary and non-monetary indicators, such as material deprivation, should be used in the difficult task of evaluating retirement income adequacy. Studies like Zaidi (2009, 2010) and OECD (2013) conclude that old-age poverty and deprivation rates have declined across most EU and OECD countries due to significant recent changes in social policies and pensions’ provision. However, the current economic crisis and austerity policies have had an impact on social policies, as described in OECD (2013) and simulated in Callan et al. (2011). A more detailed country specific analysis may be found in Aziz et al. (2013) in New Zealand; INE (2010) in Portugal; Lindquist and Wadensjo (2012) in Sweden; O’Brien et al. (2010) in the US; and Prunty (2007) in Ireland. In general, older people, and particularly older women and ethnic minorities, are at higher risk of poverty and deprivation. Brown and Prus (2006) and Goudswaard et al. (2012) focus on the state/private pension impact on poverty reduction in OECD countries and conclude that it is not significant. Albuquerque et al. (2010) discuss the transitional effects of retirement on income and poverty in Portugal (namely, that older pensioners and those with shorter contributions period are more at risk), whereas Schirle (2013) decomposes old-age poverty in Canada and shows that its single most important factor is retirement income (both pensions and social benefits).

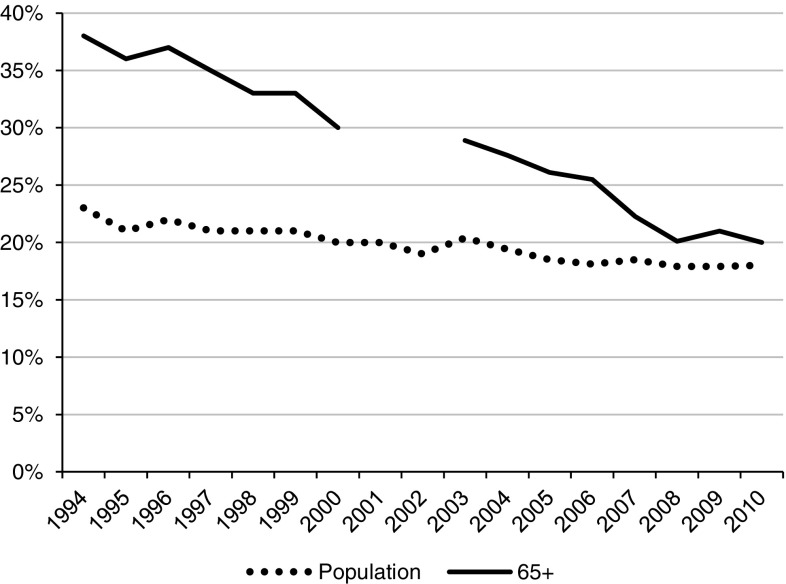

Old-age poverty declined significantly in Portugal during the last decades—whereas the national poverty rate fell from about 23 % in 1994 to 18 % in 2010, the old-age rate dropped from about 38 % to 20 %. However, this halving of the poverty rate conceals the heterogeneity of this age group where important clusters of deep poverty remain. In 2010, adults aged 75+ living alone had the highest poverty rate (33 %); and the older female poverty rate is higher (21.4 %) than the male rate (18.0 %). The aim of this paper is to characterise in detail the phenomenon of old-age poverty in Portugal in the 2003–10 period, including its non-monetary component of material deprivation, following the Eurostat methodology. This paper updates and extends previous Portuguese studies, and investigates a period of intense social policy change which included the introduction of the “Solidarity Supplement for the Elderly” (Complemento Solidário para Idosos, CSI) in 2006 and the 2007 reform of the “Social Security Law” (Lei de Bases da Segurança Social). This reform had the stated aim of safeguarding the long-term sustainability of the pension system through substantial changes in the replacement rules, linking pensions to economic growth and life expectancy, and penalising early retirement. It has led to less generous pensions, but will affect future pensioners most. Moreover, the accelerating ageing of the population has so far prevented the expected reduction in expenditure. The CSI is a means-tested benefit that aims at closing the gap between the level of old-age income and the (national) poverty line. With 236 thousand beneficiaries in 2010, the CSI has clearly contributed to the significant reduction in poverty in recent years, but its performance is still far from its proclaimed ultimate aim of taking older people out of poverty. The profound crisis that has affected Portugal since 2010 and led to the Portuguese Government signing the “Economic Adjustment Programme” with the Troika (European Commission, ECB and IMF) in 2011 brought deep budget cuts that have only begun to affect directly old-age income levels after 2011. However, these cannot yet be reflected in this study because of data unavailability.

This paper is organised as follows: Sect. 2 describes the Portuguese as an ageing, but less poor population; Sect. 3 studies in detail old-age poverty during the 2003–10 period including their income distribution; Sect. 4 analyses its other dimension, material deprivation; finally, Sect. 5 concludes the paper and summarises its main conclusions. The main data source used is the Portuguese micro-data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) made available by INE-Statistics Portugal. The EU methodology for measuring and evaluating poverty and material deprivation is followed: equivalised income is calculated by adjusting the household disposable income using the modified OECD scale; the poverty line is defined as 60 % of the median adult equivalent income; and the material deprivation indicators are based on a set of nine items available in the EU-SILC database.

An ageing, but less poor older population

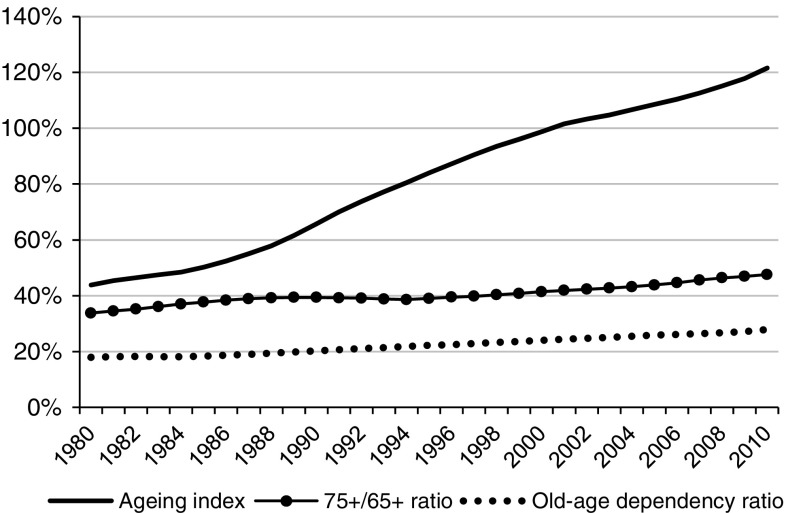

The increasing ageing of the Portuguese population is revealed in Fig. 1 below, and is described in more detail in Carrilho and Craveiro (2013). The ageing index rose quickly from around 45 % at the start of the eighties to 91 % in 1997. It crossed the 100 % barrier in 2001, meaning that more Portuguese are aged 65 and older (65+ here-after) than 15 and younger, and reached 122 % in 2010. The old-age dependency ratio has grown steadily from about 18 % in the eighties to 25 % in 2003 and 28 % in 2010. These results reflect the sharp decrease in the birth rate from 16.2 ‰ in 1980 to 9.6 % in 2010, together with an almost unchanged mortality rate of around 10 ‰. Life expectancy (at birth) has thus risen from 71.1 years in 1980 (men: 67.8, women: 74.8) to 79.6 in 2010 (76.5 and 82.4, respectively). Moreover, the proportion of people aged 75+, the ‘older old’, within the 65+ population has grown from about a third in 1980 to just under a half in 2010.

Fig. 1.

An ageing population, Portugal 1980–2010. Source INE-Statistics Portugal. Ageing index: (population aged 65+/population aged <15)*100; 75+/65+ ratio: (population aged 75+/population aged 65+)*100; Old-age dependency ratio: (population aged 65+/population aged 15-64)*100

However, the more numerous older Portuguese adults were becoming less poor: their mean equivalised income converged to the national average in the second half of the noughties, growing consistently from 83 % of that average in 2004 to 94 % in 2010. This steady rise is in marked contrast with the nineties, when that proportion had followed a downward trend (dropping to 81 % of the national average in 2000). This increase in equivalised income is reflected in the decline of the 65+ poverty rate at a much faster pace than the national rate (up to 2008), as shown in Fig. 2. The gap between the two rates decreased from about 15 percentage points in 1994 to only two in 2010.

Fig. 2.

National and old-age poverty rates, 1994–2010. Source INE-Statistics Portugal, ECHP 1995-2001 and EU-SILC 2004-2011. Authors’ calculations. NB There is no data on older poverty in the period 2001-04, i.e., between the last ECHP survey and the initial EU-SILC

Additionally, this fall in the 65+ poverty rate led to a decrease in the proportion of Portuguese poor that are older: in 1994, 26 % of the poor were aged 65+, but in 2010, this proportion had decreased to 20 %, which is even more significant when taking into account that their proportion in the total population had risen from 14 to 18 %. This decrease in old-age poverty will be considered in detail in the next section.

Old-age poverty

Data from the Portuguese component of EU-SILC for 2004–11 are used in this section to characterise the 65+ population and to investigate whether it is a homogeneous group in terms of poverty.

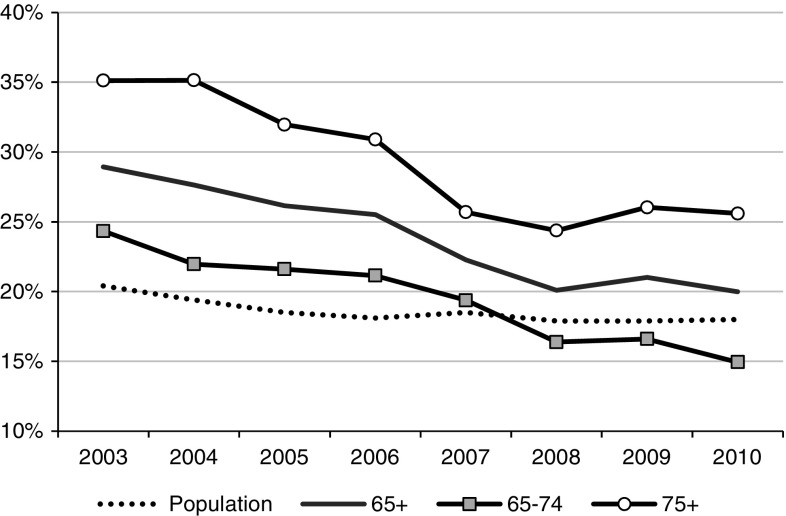

Figure 3 reveals that all old-age poverty rates follow a similar path and converge to the national rate during this period, but the 75+ poverty rate is, on average, ten percentage points higher than that of the 65–74 group. Since 2008, the 65–74 poverty rate is actually lower than the national rate, dropping to 15 % in 2010, the first year of austerity. This (lower) rate is due to two factors: the fall in the nominal poverty line, the first time since poverty statistics exist in Portugal; and the very small exposure of 65+ incomes to the 2010 austerity policies, particularly the lowest pensions. Like in most countries, gender is an important factor that reflects the higher female longevity. In 2010, the 65+ female poverty rate of 21 % was about three percentage points above the 65+ male rate.

Fig. 3.

Old-age poverty rate, 2003–2010. Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004-2011. Authors’ calculations

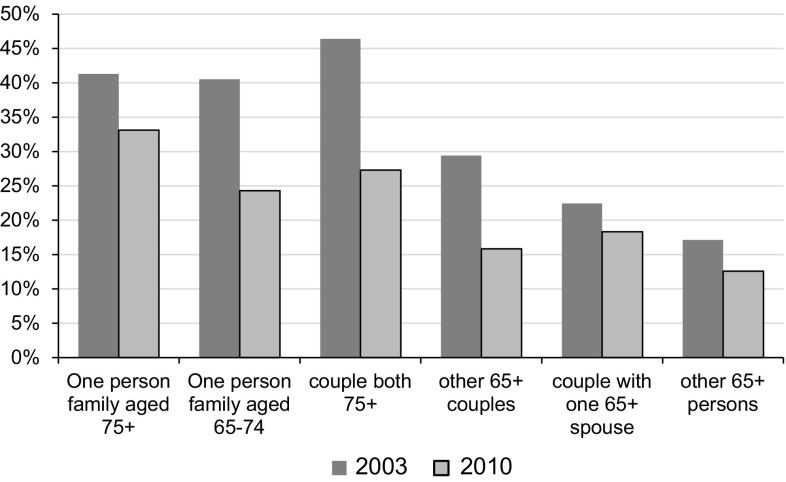

Another important factor in old-age poverty is the type of household, i.e. whether people live alone, with their spouse (also aged 65+ or not), or within extended families. Six household types are considered in Fig. 4: two of the 65+ living alone (‘one person family aged 65–74’ and ‘one person family aged 75+’); two of couples where both spouses are aged 65+ (‘couple both 75+’ and ‘other 65+ couples’, i.e. both spouses are 65–74 or only one is 65–74 and the other is 75+); and two that include people aged less than 65 (‘couples with one 65+ spouse’, and ‘other 65+ persons’, i.e. older people who live within extended families). More than 30 % of old-age people belong to the latter group, but this proportion decreased steadily in this period.

Fig. 4.

65+ poverty rate by household type, 2003 and 2010. Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004 and 2011. Authors’ calculations

There is a marked reduction in all poverty rates between 2003 and 2010 in Fig. 4, but not widespread enough to lead to a decrease in poverty incidence across all groups to levels comparable to the national average. This reduction was most evident (above 40 %) in two of the most vulnerable groups, 65–74 living alone and ‘couple both 75+’, plus ‘other 65+ couples’. The other most vulnerable group, ‘75+ living alone’, saw a much smaller reduction (just under 20 %), and as a result, the almost identical poverty rates in 2003 of the two living alone groups became separated by about 9 percentage points in 2010, with a poverty rate of the 75+ of about 33 %.

Still, more than a quarter of the 75+ either living alone or as couples are poor, whereas living with other household members aged less than 65 clearly reduces the risk of poverty. This result can be biased by the usage of the household equivalised income as proxy for the equivalised income of each individual member when more than one-third of the 65+ live within extended families. Grouping the eight household types defined in Fig. 4 above into two groups: ‘65+ in 65+ households’, which comprises all 65+ living exclusively with other 65+, and ‘65+ in other households’, which comprises all 65+ living in households that also include other individuals, shows that the poverty rate is influenced by these household arrangements. The poverty rate of the ‘65+ in other households’ is always below 20 %, and less than 15 % since 2008. Conversely, the ‘65+ in 65+ households’ rate is much higher, but its substantial drop from 36 % in 2003 to 23 % in 2010 played a major role in reducing the average old-age poverty rate. Furthermore, the gap between the two rates decreased from 18 to 10 percentage points over this period.

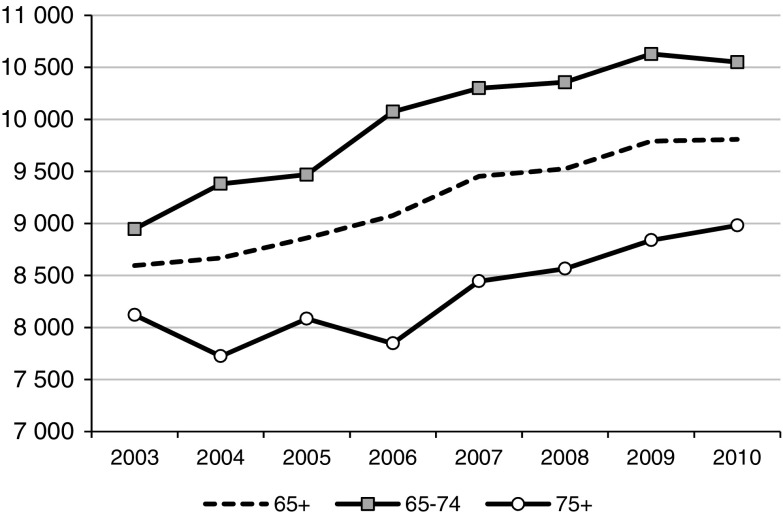

The next stage of the analyses looks into the evolution of the levels and composition of older people’s household income and how they contribute to the changes in poverty already detected. Figure 5 shows the considerable increase (almost 15 %) in the average equivalised disposable income of the 65+ over the 2003–10 period and its convergence to the national average. This increase is even more pronounced in the 65–74 group which actually overtook the national average in 2010 (10,549 and 10,407€, respectively, whereas the 75+ average equivalised disposable income increased from about 80 % of the national value to about 86 % over the same period.

Fig. 5.

Old-age average equivalised disposable Income, 2003–10, € per year, 2010 prices. Source:INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004-2011. Authors’ calculations

Another way of relating the standard of living of older people to that of the whole population is by comparing their equivalised disposable incomes. In Table 1, the income of the 65+ corresponded to 85 % of the national average in 2003, but its steady increase raised it to 94 % in 2010. This increase was not uniform and gender is important: the income of the 65–74 group and of 65+ men actually surpassed the national average in 2010 (101 and 102 %, respectively). It is the older old and women that record lower, but steadily increasing, percentages of the national equivalised income.

Table 1.

−65+ average equivalised disposable income as a % of the average national equivalised disposable income, 2003–10

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||||||

| 65–74 | 88.3 | 89.5 | 90.9 | 95.9 | 97.0 | 99.1 | 99.4 | 101.4 |

| 75+ | 80.2 | 73.7 | 77.6 | 74.7 | 79.5 | 81.9 | 82.7 | 86.3 |

| 65+ | 84.8 | 82.7 | 85.0 | 86.4 | 89.0 | 91.1 | 91.6 | 94.2 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| 65+ male | 84.6 | 86.1 | 89.5 | 90.6 | 95.5 | 97.9 | 99.6 | 101.7 |

| 75+ female | 81.4 | 80.2 | 81.8 | 83.3 | 84.3 | 86.3 | 85.9 | 88.9 |

| Household type | ||||||||

| 65+ in 65+ households | 79.5 | 75.8 | 78.1 | 83.7 | 84.9 | 87.5 | 86.9 | 89.2 |

| 65+ in other households | 93.4 | 93.8 | 96.5 | 91.2 | 96.7 | 97.9 | 100.3 | 103.7 |

Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004-2011. Authors’ calculations

It is also evident that living in households with younger people increases the equivalised income of the older cohort considerably, eventually taking it to above the national average (104 % in 2010). A partial explanation for this relative improvement in older people’s income is the stronger growth (in real terms) of pensions compared to the other components of disposable household income in this period: household income rose at a higher rate than pensions up to 2004, but was significantly affected by the financial crisis, whereas pensions rose steadily throughout this period and actually reached their highest level in 2010. Moreover, pensions were not substantially affected by the austerity budget cuts up to 2010, unlike wages and social transfers (see Rodrigues and Andrade (2013) for a detailed discussion).

The main source of income of older people is naturally pensions. Portugal has essentially a Bismarckian pension system where pension values are a function of contributions paid and number of years worked, complemented first by a non-contributory means-tested social pension to which those aged 65+ with no other source of income are entitled, and secondly by the CSI if the social pension is not enough to take the household income above the poverty line. The proportion of 65+ in receipt of pensions, either contributive or (means-tested) social pensions, rose from 91 % of their total number to 94 % over this period. Likewise, the proportion of older people whose main source of income is pensions rose from 86 to 92 %, but considerably more for the 75+ with 91 and 95 %, respectively.

Social Security macroeconomic data give a further insight into the analysis of older people’s income and changes in their poverty. The 2010 Social Security accounts reveal that the value of the monthly contributive pension rose from 351.1€ in 2003 to 477.03€ in 2010, a nominal increase of 35 % and a real increase of over 18 %. It reflects both the higher number of contributive years taken into account in the pension awarding process and the higher average pension value of the ‘new’ pensioners. This largely explains the difference between the poverty rates of the 65–74 and 75+ groups described above.

The monthly value of the social pension also increased substantially: for those aged 65–69, it rose from 156.97 to 207.06€, and for those aged 70+, it rose from 170.14 to 224.58€, a nominal increase of 32 % and a real increase above 15 % in both cases. The growing importance of the social pension is reflected in the increasing of its weight in total pension expenditure: from 12 % in 2003 to 15 % in 2010. This rise in the values of (average) pensions, clearly at a higher rate than the national disposable income, is the prime explanation of the significant decrease in old-age poverty rate in Portugal.

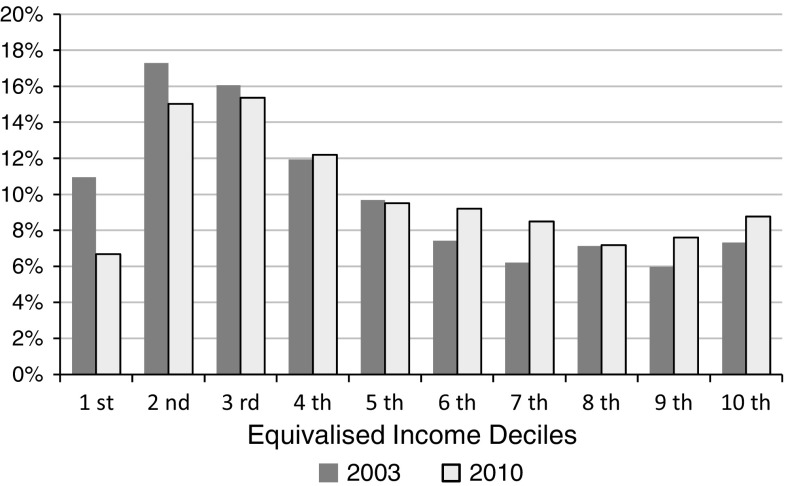

The general improvement in older people’s income levels is reflected in their distribution by equivalised income deciles. In Fig. 6, this distribution is compared for 2003 and 2010. The proportion of 65+ in the two lowest deciles dropped from 28 to 22 %, whereas their proportion in the two highest increased from 13 to 16 %. This shift towards the high end of the income distribution is a direct result of the relative income improvements already discussed.

Fig. 6.

65+ equivalised disposable income by deciles, 2003 and 2010. Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004-2011. Authors’ calculations

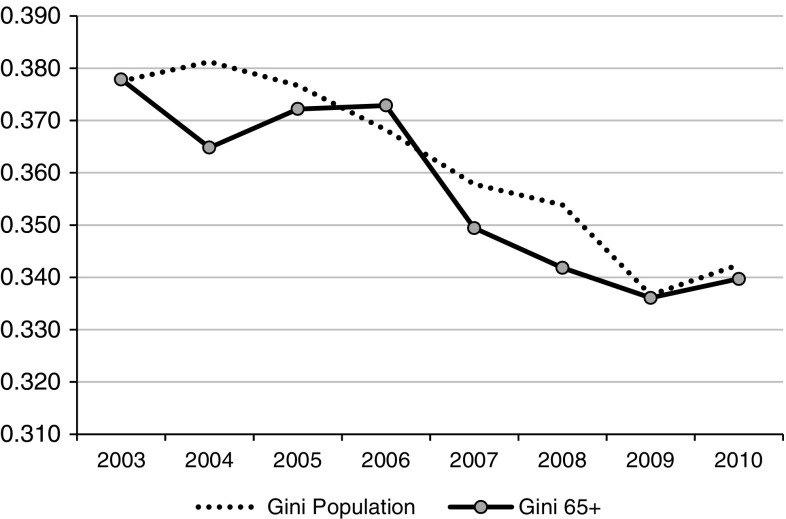

Another way of investigating the heterogeneity of the 65+ group is through the analysis of the inequality of their income distribution, as measured by the Gini coefficient. This is particularly important due to the high levels of Portuguese inequality described in detail in Rodrigues and Andrade (2014).

Figure 7 shows the steady reduction in the Portuguese income inequality between 2004 and 2009 and subsequent increase in 2010. In 2003, the old-age income distribution was as unequal as the national one, and by the end of the period, their inequality was almost identical (0.342 and 0.340, respectively). Although following a more irregular path, the 65+ group is about as heterogeneous as the whole population. In the next section, a broader definition of poverty, material deprivation, is used to analyse the old-age cohort within Portuguese society.

Fig. 7.

Gini Coefficient, 2003–10. Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004-2011. Authors’ calculations

Old-age material deprivation

It is widely agreed that being poor cannot be reduced to a lack of monetary resources, but also includes the inability to enjoy a minimum standard of living and participation in society. The material dimension of poverty, or material deprivation, is defined as the inability to attain certain basic standards of living and consumption. In order to implement these concepts, the EU has defined nine indicators of material deprivation (see Guio (2005, 2009) and Guio et al. (2009), for example). They include a wide range of items that are listed in detail in the first column of Table 2. Each figure in the table gives the percentage of ‘enforced lack’, i.e. the percentage of individuals that would have liked to possess the item, but could not afford it, and therefore, were deprived of it. In the case of items I6 to I9, the indicators distinguish between lack of financial capacity and ‘no interest or necessity’.

Table 2.

Deprivation indicators (%), 2003 and 2010

| Population | 65+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2010 | 2003 | 2010 | |

| I1. Inability to face unexpected financial expenses | 19.5 | 29.0 | 25.9 | 26.9 |

| I2. Inability to afford paying for one week annual holiday away from home | 60.7 | 57.1 | 70.7 | 63.8 |

| I3. Arrears (mortgage or rent payments, utility bills or hire purchase) | 8.1 | 10.2 | 4.7 | 3.3 |

| I4. Inability to afford a meal with meat, chicken or fish every second day | 4.4 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 3.9 |

| I5. Inability to keep home adequately warm | 36.3 | 26.7 | 46.8 | 30.4 |

| I6. Enforced lack of a washing machine | 3.5 | 1.5 | 9.1 | 3.6 |

| I7. Enforced lack of a colour TV | 1.1 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 0.8 |

| I8. Enforced lack of a telephone | 3.9 | 1.9 | 6.7 | 3.9 |

| I9. Enforced lack of a personal car | 12.0 | 9.2 | 14.8 | 10.5 |

Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004 and 2011. Authors’ calculations

The three items that older people are most deprived of coincide with the national average (see Rodrigues and Andrade (2012) for a detailed analysis and discussion of Portuguese material deprivation). In decreasing order they are: “Inability to afford paying for 1 week annual holiday away from home” (I2), “Inability to keep home adequately warm” (I5) and “Inability to face unexpected financial expenses” (I1). Their deprivation decreased from 71 % of the 65+ in 2003 to 64 % in 2010 for I2 and 47 % to 31 % for I5, with a slight increase for I1, reflecting the financial crisis. The fourth most deprived item is “Enforced lack of a personal car” (I9), whereas nationally it is generally “Arrears (mortgage or rent payments…)” (I3), but this difference reflects group circumstances. Gender and household types do not significantly affect the ranking of the deprivation items, although I3 is more important to the 65+ living within extended families, which again reflects the different characteristics of these households. Generally women aged 65+ are less deprived of a telephone, TV and washing machine than men in the same age group. Full detailed results are available from the authors. Finally, it could be argued that adopting a different set of items, as in Zaidi (2011), or weighing methodology, as in Rodrigues and Andrade (2012) for the whole population, would be more appropriate to study this age group, but that is beyond the scope of the current study.

The first EU agreed measure of material deprivation is defined as the enforced lack of at least (any) three of the nine items, and therefore, is a measure of the deprivation incidence. The second is a measure of its intensity, and is defined as the mean of the number of items that individuals are deprived of. Higher 65+ income levels in this period are reflected in the decline of the old-age material deprivation rate and its convergence to the national rate (21.3 and 20.9 %, respectively, in 2010). As shown in Table 3, on average, the 65+ were deprived of 1.88 items in 2003, well above the national 1.49, but by 2010, this value had dropped to 1.47 compared to the national 1.39, reflecting the already discussed convergence. However, if poverty risk is taken into account, this drop becomes more substantial: the 65+ poor were deprived, on average, of 2.68 items, compared to the 2.50 national poor in 2003, but by 2010, the national average had hardly changed, whereas the 65+ average had dropped to 2.29. Actually, it was the 65+ non-poor that recorded the highest drop in deprivation rates over this period (23 to 16 %) followed by the 65+ poor (51 to 43 %), whilst the national non-poor and poor rates hardly changed. Nevertheless, the material deprivation of the 75+ is still above that national rate; and women are more deprived than men, with a 65+ female deprivation rate in 2010 of 24 %, six percentage points above the male rate (not shown in the table).

Table 3.

Deprivation indicators, 2003 and 2010

| Non-poor | Poor | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2010 | 2003 | 2010 | 2003 | 2010 | |

| Population | ||||||

| Deprivation rate | 15.7 | 15.4 | 45.0 | 45.8 | 21.7 | 20.9 |

| Deprivation Intensity | 1.24 | 1.16 | 2.5 | 2.45 | 1.49 | 1.39 |

| 65+ | ||||||

| Deprivation rate | 22.9 | 16.0 | 51.3 | 42.7 | 31.1 | 21.3 |

| Deprivation intensity | 1.55 | 1.27 | 2.68 | 2.29 | 1.88 | 1.47 |

Source INE-Statistics Portugal, EU-SILC 2004 and 2011. Authors’ calculations

The highest reduction in material deprivation is recorded in households that include only 65+ individuals, but in 2010, the 65+ living alone are still the most deprived group. Older people living with younger relatives show smaller reductions in deprivation, echoing the smaller relative reduction in the national rate already discussed.

Conclusion

One of the clearest indicators of the social changes that have occurred in Portugal over the last decades is the significant decrease in old-age poverty: between 2003 and 2010, the poverty incidence of the older Portuguese dropped by 31 %. Given the considerable percentage of 65+ in the total population, this large decrease necessarily had an impact on the national poverty indicators.

This study highlights the heterogeneity of the older population in terms of poverty indicators: although their poverty rate as a whole fell, poverty pockets subsist at disturbingly high levels. In particular, those aged 75+ and living alone record a poverty rate above 30 % in 2010, implying that this group remains one of great economic and social vulnerability, and justifying the safeguarding, and even expansion, of the social measures that target it specifically.

An important feature of this heterogeneity is the difference between the higher average income of the 65–74 group versus the 75+, a feature that needs to be taken into account in the design of social and economic policies aimed at older people in general. In fact, the analysis of the asymmetric 65+ income distribution reveals that being 65+ does not necessarily imply low income or vulnerability: in 2010, more than 16 % of the people in this age group were in the two highest deciles of that distribution. The high level of 65+ inequality, which mirrors the national average, justifies the need for social and poverty targeting policies that privilege a means-tested approach, rather than a universal one.

The study of material deprivation enabled an in-depth identification of the more exposed older people. Those living alone or in couples where both spouses are aged 75+ emerge as the most vulnerable, both in terms of monetary resources and of access to goods and services. However, the usage of a methodology (and indicators) common to all EU population instead of one designed specifically for them and their needs have to be seen as a limitation.

The evolution of pensions, both contributive and means-tested, is a key element in the reduction in poverty and improvement in the living standards of the 65+. However, the austerity policies implemented post-2010 have made a strong impact on pensions and can reverse these positive recent developments, even though the lowest pensions have remained relatively excluded from the cuts. This reverse in social policies, of which another example is the recent drop in the number of CSI beneficiaries, will necessarily lead to a fall in their efficacy in reducing poverty, and extreme poverty, in Portugal.

Finally, the continuing impoverishment and high unemployment rates of the Portuguese population are forcing many older people to support financially their children and grandchildren who have been hit by the recession and unemployment. The improved living standards older people had secured for their retirement may now be lost, as they are hit by the current crisis in a more convoluted way.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank three anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions. However, the usual disclaimer applies. We also acknowledge INE-Statistics Portugal for permission to use the Portuguese EU-SILC microdata (Protocol INE/MCES, process 413).

References

- Albuquerque P, Arcanjo M, Nunes F, Pereirinha J. Retirement and the poverty of the seniorly: the case of Portugal. J Inc Distr. 2010;19:41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz O, Gemmell N, Laws A (2013) The distribution of income and fiscal incidence by age and gender: some evidence from New Zealand. Victoria University of Wellington Working Papers in Public Finance 10/2013

- Brown RL, Prus SG. Income inequality over the later-life course: a comparative analysis of seven OECD countries. Ann Act Sci. 2006;1:307–317. doi: 10.1017/S1748499500000178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callan T, Leventi C, et al. (2011) The distributional effects of austerity measures: a comparison of six EU countries. EUROMOD Working Papers EM6/11, Institute for Social and Economic Research, Colchester

- Carrilho MJ, Craveiro ML. A situação demográfica recente em Portugal. Revista de Estudos Demográficos. 2013;50:45–90. [Google Scholar]

- Goudswaard K, van Vliet O, Been J, Caminada K. Pensions and income inequality in old age. CESifo DICE Report. 2012;4(2012):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Guio A-C. Material deprivation in the EU. Statistics in focus: population and social conditions. Luxembourg: Eurostat; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guio A-C. What can be learned from deprivation indicators in Europe? Luxembourg: Eurostat; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guio A-C, Fusco A, Marlier E (2009) A european union approach to material deprivation using EU-SILC and Eurobarometer Data. IRISS Working Paper 2009–19

- INE (2010) O risco de pobreza e a privação material das pessoas idosas. In: Sobre a pobreza, as desigualdades e a privação material em Portugal. INE, Lisboa (About poverty, inequality and material deprivation in Portugal)

- Lindquist GS, Wadensjo E (2012) Income distribution among those of 65 years and older in Sweden. IZA DP No. 6745

- O’Brien E, Wu KB, Baer D. Older Americans in poverty: a snapshot. Washington: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2013) Old-age income poverty. In: Pensions at a glance 2013: OECD and G20 countries, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2013-26-en

- Prunty M (2007) Older people in poverty in Ireland: an analysis of EU-SILC 2004. Combat Poverty Agency Working Paper Series 07/02

- Rodrigues CF, Andrade I. Monetary poverty, material deprivation and consistent poverty in Portugal. Notas Económ. 2012;35:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues CF, Andrade I (2013) Robin Hood versus Piggy Bank: income redistribution in Portugal 2006–10. Working Papers Department of Economics 2013/28, ISEG, Lisbon

- Rodrigues CF, Andrade I, et al. Portugal: there and back again, an inequality’s tale. In: Nolan B, et al., editors. Changing inequalities and societal impacts in rich countries: thirty countries’ experiences. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 514–540. [Google Scholar]

- Schirle T. Senior poverty in Canada: a decomposition analysis. Can Public Policy. 2013;39(4):517–540. doi: 10.3138/CPP.39.4.517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A. Poverty and income of older people in OECD countries. Vienna: ECSWPR; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A (2010) Poverty risks for older people in EU countries—an update. ECSWPR Policy Brief January (11): 1–23

- Zaidi A (2011) Exclusion from material resources among older people in EU countries: new evidence on poverty and capability deprivation. ECSWPR Policy Brief July (2): 1–17