Abstract

Whereas it is often stated that aging might have more negative consequences for the evaluation of women compared to men, evidence for this assumption is mixed. We took a differentiated look at age stereotypes of men and women, assuming that the life domain in which older persons are rated moderates gender differences in age stereotypes. A sample of 298 participants aged 20–92 rated 65-year-old men and women on evaluative statements in eight different life domains. Furthermore, perceptions of gender- and domain-specific age-related changes were assessed by comparing the older targets to 45-year-old men and women, respectively. The results speak in favor of the domain specificity of evaluative asymmetries in age stereotypes for men and women, and imply that an understanding of gendered perceptions of aging requires taking into account the complexities of domain-specific views on aging.

Keywords: Age stereotypes, Middle and older adulthood, Gender differences, Life domains

Introduction

Are older men and women perceived and evaluated differently? Or are age stereotypes independent of perceptions of gender and vice versa? Public discourse speaks in favor of the former assumption. According to the so-called “double standard of aging” (cf. Sontag 1972) older women are evaluated more negatively than older men, especially because their “most highly valued social asset, their physical attractiveness” declines whereas men’s “most valued social resources, their earnings potential and achievement” increase as they age (Barrett and von Rohr 2008, p. 360). This hypothesis of a double standard of aging has sparked research that investigates the consequences of a double categorization that is based on the interaction of a person’s gender and age. And even though the original double standard has been formulated with regard to the bodily domain, it has been applied to other domains as well (e.g., Canetto et al. 1995; Kite et al. 2005), assuming that the appearance-related disadvantages of women tend to generalize to other domains.

However, if one takes a closer look at the studies that investigated effects of both age and gender characteristics on evaluations of the respective target categories, a rather differentiated picture emerges. Even though there are studies showing that “old age” is perceived to start earlier for women (Barrett and von Rohr 2008; Kite and Wagner 2002), that women hold younger age identities than men to protect their selves from devaluation (Barrett 2005), and that in some studies older women are actually evaluated more negatively on factors including competence and appearance (e.g., Canetto et al. 1995; Deutsch et al. 1986), there are also studies demonstrating that older women might actually be perceived more favorably in general (Narayan 2008; Laditka et al. 2004) or at least in some domains: For instance, older women are rated more positively when it comes to attributes that are related to nurturance or social competence, neatness, and care (Canetto et al. 1995)—an effect that might be explained by the fact that those domains represent traditional “warm” gender roles. More astonishingly though, in their meta-analysis, Kite et al. (2005) reported that older females are judged even more positively with regard to competence than older men, which speaks for a more differentiated view. And even for attractiveness, results are not clear-cut: In a study by Teuscher and Teuscher (2007), older adults were seen as less attractive than younger ones, regardless of target gender (for bodily self-perceptions, see also Wilcox 1997). It thus seems that an unqualified assumption of an aging double standard that disfavors women is an oversimplification of a rather complex social phenomenon.

This call for a more complex, domain-specific investigation of social perceptions of older men and women is further corroborated by recent studies that have looked at age stereotypes without specifying the gender of the target. Even though overall age stereotypes seem to be predominantly negative, there is considerable variability in the activation and evaluative content of age stereotypes (and general age awareness), depending on the domain in which the older person is seen (Casper et al. 2011; Diehl and Wahl 2010; Gluth et al. 2010; Kite et al. 2005; Kite and Wagner 2002). Most recently, we (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011) found that the evaluation of older persons varies strongly if one specifies stereotypic statements about “old persons” in different life domains. Whereas older persons were perceived rather positively in domains like family and work, they were perceived rather negatively in the domains of friends and health, corroborating the assumption of a differentiated view on older persons that is largely dependent on context factors. Such a domain dependency also applies to the content and activation of gender stereotypes (Casper and Rothermund 2012; Mendoza-Denton et al. 2008; Thompson 2006).

However, even though some studies did measure age and gender stereotypes in a differentiated way, those studies relied on ratings of somewhat abstract attributes and characteristics. To our knowledge, so far no one has systematically investigated gender-specific stereotypes of older persons that are presented in various, specific life domains. Investigating domain-specific stereotypes is important not only with regard to the evaluation of older men and women, but stereotypes can also be applied to the self (“self-stereotyping”) and become internalized into the self-concept (Latrofa et al. 2010; Levy 2009; Rothermund and Brandtstädter 2003). There is also first evidence that such an internalization of (age and gender) stereotypes might be domain-specific (Casper and Rothermund 2012; Kornadt and Rothermund 2012).

A factor that further complicates matters is the role of rater age and gender. Whereas previous findings show that older adults rate other older adults more favorably (Gluth et al. 2010; Laditka et al. 2004), our study (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011) already yielded evidence that life domain might moderate this effect: Even though overall, older adults provided more positive ratings of older persons, there were also life domains where young people gave higher ratings of older persons (such as religiosity, personality), whereas there were no age group differences in other domains (such as leisure, finances). Furthermore, since most of the previous studies were conducted several years ago, and some of them relied mostly on college students, it is still unclear whether there might be age- or cohort-related differences in the ratings of older men and women stemming from possible changes in the perception of gender roles that have occurred in the last two or three decades (e.g., Swazina et al. 2004). This should be especially visible in different ratings given by younger compared to middle-aged and older persons, therefore we assume that in general, younger adults should report less gender differences than middle-aged and older adults.

Findings regarding rater gender are somewhat mixed as well. Some studies that find differences in ratings of older men and women show that women rate older persons more favorably in general (Bodner et al. 2012; DeArmond et al. 2006; Deutsch et al. 1986), some find that this applies only for the ratings of older women (Laditka et al. 2004), and yet others do not find any gender differences at all (Grant et al. 2002). We therefore do not have any specific hypotheses for the interaction of participant and target gender.

Taken together, we argue that a domain-specific perspective on stereotypes of older men and women could shed further light on previous findings reported in the literature on aging and gender stereotypes. Based on our previous study (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011) that investigated domain-specific age stereotypes, and on the assumption that the perception of older men and women is based on their perceived match to the roles and characteristics that are relevant in a certain domain (Eagly and Steffen 1984; see also Barrett 2005; Diekman and Hirnisey 2007; Grühn et al. 2011; Kite 1996; Kite and Wagner 2002; Thompson 2006), we assume that older men and women should be rated differently depending on life domain. Specifically, drawing on social role theory (Eagly and Steffen 1984; Eagly et al. 2000; Kite 1996), we expected men to be rated more positively in domains that relate to agency (work, finances), whereas women should be rated more positively in domains regarding nurturing and social contacts (family, friends, leisure), and—assuming the original double standard of aging was still true—more negatively in the health domain. Since our study is the first to investigate age and gender stereotypes in such a differentiated way, we do not formulate specific hypotheses for the other domains.

Furthermore, it is important to disentangle differences in the evaluation of older men and women from differences that are primarily due to differential ratings of men and women in general and thus unrelated to age. Therefore, we compared the ratings of older men and women to those of middle-aged men and women. This allowed us to identify not only differences between perceptions of older men and women, but also to attribute these differences to gender-specific differences in perceived age-related changes. We thus extend previous research on age and gender stereotypes by using a differentiated measure of age stereotypes that takes life domain and target age differences into account, and by investigating raters of both genders covering a large age range.

Methods

Sample

A total sample of N = 298 raters, comprising younger (n = 112; 65 female, aged 20–28 years; M age = 22.53, SD = 2.45), middle-aged (n = 98; 50 female; aged 30–58 years; M age = 46.03, SD = 3.59), and older adults (n = 88; 51 female; aged 60–92 years; M age = 67.92, SD = 6.22) participated in the study. One older female participant chose not to report her age and was thus excluded from analyses. Younger participants were recruited on campus and in introductory psychology classes at the University of Jena, Germany, the middle-aged and older adults were contacted via snowball and convenience sampling, and in the waiting room of a general practitioner. Psychology students received course credit for participation; among the other participants, two amazon.com vouchers worth € 20 were raffled as compensation for their participation.

Age groups differed in background variables, reflecting typical differences between age groups: Younger participants were more likely to have university-bound school degrees than middle-aged and older persons, they were less likely to report fair or bad health, and more likely to be single than older and middle-aged participants. Middle-aged and older participants only differed with regard to marital status, middle-aged participants were less likely to be single than older participants.

Measures

Participants first provided socio-demographic information and then completed a questionnaire (in German) that was adapted from Kornadt and Rothermund (2011) to assess age stereotypes in different life domains. The life domains were chosen from an interview study with older adults and comprised the following: Family and Partnership (family), Friends and Acquaintances (friends), Religion and Spirituality (religion), Leisure Activities and Commitment (leisure), Personality and Way of Living (personality), Finances and Money (finances), Work and Employment (work), as well as Physical and Mental Health, Fitness and Appearance (health). For each domain, “old persons” were rated on 3–5 items consisting of an eight-point scale between the negative (1) and the positive (8) pole of a stereotypic statement, respectively. Participants were instructed that they should give their evaluations of persons of different ages and gender. For details on the questionnaire construction and item wordings, see Kornadt and Rothermund (2011).

For the present study, the questionnaire was adapted in three ways: First, a fixed age was given for the male and female rating targets to make sure that all participants imagined men and women of the same age. We chose the age of 65 for the “old” targets, since this was the average age at which across all domains, people were rated as being “old” in previous studies (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011). Additionally, 45-year-old persons (middle-aged targets) were rated on the same items, in order to have a baseline of gender differences that is not affected by gendered perceptions of aging. Therefore, each participant rated 65-year-old men, 45-year-old men, 65-year-old women, and 45-year-old women on the same items for all life domains consecutively1. The order of target gender was counterbalanced within each of the participant age groups.2 So for each domain, respectively, half of the participants rated the three male targets first and the other half first rated the three female targets.

Scales were computed by calculating the mean for the 3–5 items per domain3 for each target, with higher values representing more positive evaluations of the targets. This resulted in eight scales for 65-year-old women and men, as well as for 45-year-old women and men, respectively. Reliabilities of the scales were satisfactory (65-year-old female target: 0.66 ≤ α ≤ 0.86; 65-year-old male target: 0.70 ≤ α ≤ 0.81; 45-year-old female target: 0.70 ≤ α ≤ 0.86; 45-year-old male target: 0.73 ≤ α ≤ 0.83).

Analyses

In order to test our assumptions, we performed 8 (life domain) × 2 (target gender) × 3 (participant age group) × 2 (participant gender) mixed model analyses of variance (ANOVA) with life domain and target gender as within-subjects factors and participant age group and gender as between-subjects factors4. In a first analysis, we used the mean ratings of 65-year-old men and women as a dependent variable. In order to test whether domain-specific gender differences in the ratings of older men and women indeed represent gendered age stereotypes rather than reflecting pure gender differences that are independent of age, we performed a second analysis and computed the difference between the ratings of 65-year-old and 45-year-old targets as a measure of gendered perceptions of age-related changes. These difference scores were then used as a dependent variable, with higher values indicating that older persons are rated more positively than middle-aged targets. When overall effects in the ANOVA where significant, we performed post hoc comparisons (simple effects, Sidak-corrected) for the relevant factor combinations. For some tests, df is slightly lower than the sample size because some participants [n = 13 (4 %) for the first and n = 16 (5 %) for the second analysis] did not enter the test due to missing values on single variables.

Results

Ratings of older men and women

Replicating results from former studies, the analysis yielded a significant main effect for domain F(7, 272) = 44.04, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.53. Regardless of gender, older persons were rated rather positively in the domains of family and work, and rather negatively in the friends, finances, and health domains. The main effect for participant age group was also significant, F(2, 278) = 10.94, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.07, indicating that across domains, the oldest participants rated older men and women more positively than the middle-aged and young participants. Furthermore, the effect of target gender was significant, F(1, 278) = 43.28, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.14, indicating that older women were rated more positively than older men.

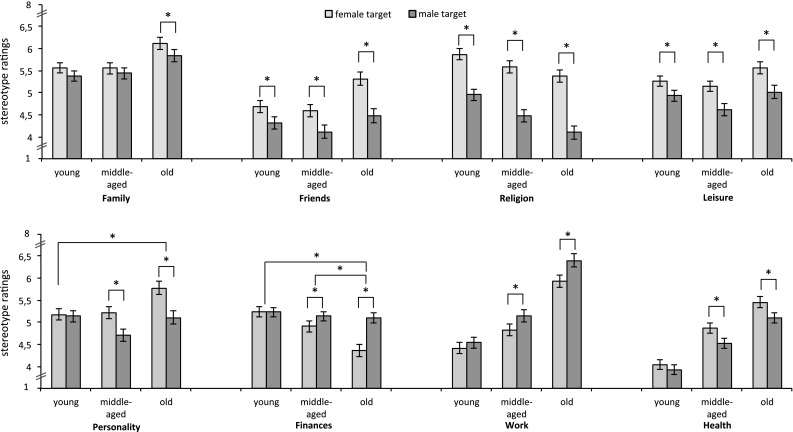

However, those main effects were qualified by significant interaction effects: First, the interaction of target gender × participant gender was significant, F(1, 278) = 38.79, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.12. Whereas men did not rate older men and women differently (M female = 4.99, SD = 0.67; M male = 4.96, SD = 0.78), women showed an in-group preference and evaluated women more positively than men (M female = 5.23, SD = 0.70; M male = 4.76, SD = 0.73). The interactions domain × age group, F(14, 546) = 9.05, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.19, and domain × target gender F(7, 272) = 37.69, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.49, were also significant, but further qualified by a significant three-way interaction of domain × target gender × age group, F(14, 546) = 3.01, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.07 (the pattern of means for this interaction is depicted in Fig. 1). Deviating from the general trend to evaluate older women more positively than older men, a reversed effect favoring men over women was found for the domains of finances and work, but this reversed effect was restricted to the groups of middle-aged and older raters. There was also a significant target gender × age group interaction for the personality domain, in which the young raters deviated from the middle-aged and older raters in that they did not evaluate older women more positively than older men. Somewhat unexpectedly, no gender differences emerged in the family domain, in which only the older participants rated women as more positive than men. No other main or interaction effects reached significance (all F < 2.73, all p > 0.07).

Fig. 1.

Mean values and standard errors for the ratings of older female and male targets by the three participant age groups. *p < 0.05 (post hoc comparisons, Sidak-corrected)

Comparison of middle-aged and older rating targets

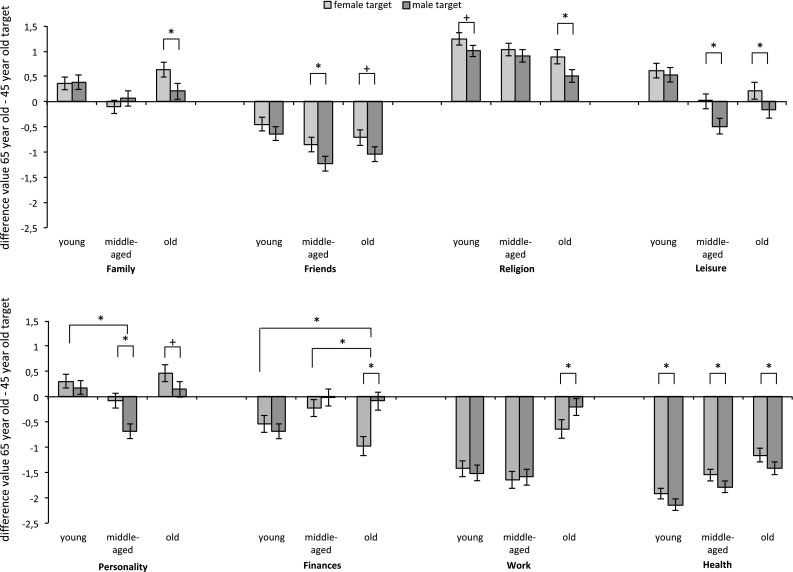

The analysis with the difference scores between the ratings of 65-year-old and 45-year-old targets yielded highly similar results to the analysis of the absolute ratings of older men and women that was reported above (see Fig. 2 for an illustration of the pattern of means of gender-specific age-related changes in the respective domains): The main effect of domain was significant, F(7, 269) = 130.83, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.77, indicating that whereas older persons were rated more positively than middle-aged persons in the domains of family, religion, and leisure, they were rated more negatively in the friends, finances, work, and health domains. No age differences were obtained for the domain of personality. The main effect of participant age group was significant, F(2, 275) = 6.84, p < 0.01, η p² = 0.05, indicating generally more positive ratings of age-related changes in the group of older raters. The domain × age group interaction was also significant, F(14, 540) = 8.08, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.17, indicating that as in the previous analysis, age differences between the three groups of raters were mostly due to the work and health domains. Also, female targets were generally rated more positively than men, F(1, 275) = 14.98, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.05, and this effect was qualified by a domain × target gender interaction, F(7, 269) = 6.54, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.15 (female targets were rated more negatively only for finances, no gender differences were obtained in the domains of family and work), and by a target gender × participant gender interaction, F(1, 275) = 13.15, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.05. However, the three-way interaction including domain was also significant, as female participants rated women especially positive in the friends, leisure, and health domains, F(7, 269) = 3.53, p < 0.01, η p² = 0.08.

Fig. 2.

Difference values and standard errors for the ratings of older targets minus the ratings of middle-aged targets by the three participant age groups. *p < 0.05 + p < 0.10 (post hoc comparisons, Sidak-corrected)

Most interestingly, and replicating the findings from the previous analysis, the three-way interaction domain × target gender × age group was again significant, F(14, 540) = 3.14, p < 0.001, η p² = 0.08. Although the magnitude of the effects was slightly smaller than for the absolute ratings, the analyses yielded highly similar patterns (see Fig. 2): Perceived age-related changes were more positive for women than for men in most domains (family, friends, religion, leisure, personality, health), but again, a reversed effect favoring men over women was obtained for the finances and work domains. As in the previous analysis, these domain-specific differences in gendered perceptions of age-related changes were generally more pronounced for the older and middle-aged raters. No or only small gender differences were obtained for the young raters, regardless of domain, and independently of whether age-related changes were perceived to be more favorable for women or for men within the groups of older raters. No other main or interaction effect reached significance (all F < 2.54, all p > 0.08).

Discussion

Starting from the assumption that the mixed findings regarding differential evaluations of older men and women might be partially explained by the domain specificity of age and gender stereotypes, we asked people about their evaluations of older men and women in different life domains. Our results point to a differentiated view on older men and women. However, overall, older women were rated more positively in our study. This was visible in absolute ratings of “old” targets, but also when investigating gendered perceptions of age-related changes by comparing ratings of “old” and “middle-aged” targets. In addition, effects were more pronounced for female participants, who rated older women more favorably than older men, whereas male participants did not show gender-specific differences in ratings. This is in line with previous findings of a gender-specific in-group bias for women but not for men (e.g., Aidman and Carroll 2003; Rudman and Goodwin 2004), and might be related to the fact that gender identity seems to be more important for women than for men (e.g., Cameron and Lalonde 2001), resulting in stronger age-group identification and endorsement of age-group stereotypes that is less situationally flexible (Casper and Rothermund 2012). Additionally, since women might be perceived as the social group lower in status, this identification might result in a stronger devaluation of an out-group in order to maintain self-esteem (Latrofa et al. 2010, 2012). However, since we did not assess gender self-stereotyping, we cannot provide more conclusive evidence for this assumption; this would be one interesting avenue for further research.

Supporting our main assumption, ratings were dependent on participant age and life domain. Instead of a general double standard of aging, the domains of finances and work were the only ones in which men were clearly rated more positively than women. This was true for the absolute ratings of older men and women as well as for the comparisons with middle-aged men and women, probably expressing the status of older men as being or having been the main financial providers and breadwinners for their families (cf. Kite 1996). Furthermore, there were pronounced gender differences in the domains of religion, friends, and leisure; in those domains older women were rated more positively than men by all age groups. Still, this result is not too surprising, considering that all these domains are “social” domains, where women of all ages might be evaluated more positively (Canetto et al. 1995). Somewhat unexpectedly, however, women were also evaluated more positively in the domains of personality, which tapped characteristics regarding openness and advice giving, as well as health, which also encompasses an item concerning appearance. This speaks against the assumption that especially the age-related deterioration of the body seems to have stronger negative consequences for the evaluation of women; in fact, our data speak in favor of the opposite assumption.5 Also surprising is the lack of pronounced gender differences in the family domain, where only older participants rated women more favorably. Due to the stereotype of women occupying the caretaker role, it would have been expected that they would be evaluated more positively in this domain. It may be possible that in this domain, a cohort effect is visible: For the older participants, being family-oriented is more of a female characteristic, whereas this effect is mitigated in younger age groups that grew up more with the idea of gender equality in family roles. We will come back to this point later in the discussion.

Taken together, it seems that participants differentiated men and women with regard to the perceived “fit” to the requirements of the life domain to be rated in, and this differentiation yielded more positive results for older women in the majority of domains. It can thus be assumed that women are perceived as being more active and vigorous than older men, which is reflected in most life domains of our questionnaire. Importantly, these effects cannot be explained by general perceptions of gender differences that are independent of age. Similar results were obtained when comparing the ratings of older to middle-aged targets. Apparently, aging and age-related changes are perceived to differ between men and women, and the quality of these perceived gender differences depends on the life domain on which they are rated.

As already mentioned for the family domain, another interesting finding is related to participant age. Whereas the middle-aged and older age group did show gender differences for almost all domains, younger participants did not rate men and women differently in most domains. This might be due to the fact that for the younger generations, men and women might be perceived as being more “equal” (Narayan 2008). However, it may also be the case that for younger participants, age was the most relevant category in the ratings, overshadowing any moderating effect of gender on the perceptions of older persons that might be prevalent in a certain domain (Kite et al. 1991). This is supported by studies showing that older persons have more differentiated age stereotypes, which might also apply to the ratings of older men and women (Hummert et al. 1994). However, the fact that even the younger participants did show gender differences in the social domains, and that some of these gender differences were also found when comparing the ratings of older men and women with their middle-aged counterparts, speaks more in favor of the first explanation, i.e., the softening of gendered age stereotypes in certain domains. Since we have to rely on cross-sectional data though, this assumption is rather speculative and requires further longitudinal and experimental evidence (e.g., comparing explicit and implicit measures of gendered age stereotypes).

Some limitations have to be kept in mind when interpreting the results of our study. The age of the older targets was always 65 years, and even though this age has been shown to represent “old” persons in the majority of life domains (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011; see also Barrett and von Rohr 2008), we do not know whether changing the age of the “old” target would result in different ratings. One could imagine that for the oldest old, gender differences might vanish for most life domains, whereas lowering the age of the target might result in more negative ratings for women, since it is assumed that aging is perceived to start earlier for them (Kite and Wagner 2002). Systematically varying the age of the target to be rated might be one avenue for further research.

Our within-subjects design where all participants had to rate all targets might also have led to the amplification of differences between persons of different gender and age groups (Kite et al. 2005). However, target order was the same for all life domains, and we found an interaction of target gender and age group with the life domain in which the targets had to be rated, which we think is an indicator for the validity of our results. That is, the most important finding reflecting specific patterns of gender differences in the evaluations of older persons for different domains cannot be attributed to the design of our study. Still, further research should take into account that age and gender differences in ratings might be of varying magnitude depending on the research design. The application of indirect and implicit measures of age and gender stereotypes might be another avenue to reduce the impact of such demand characteristics.

Another important point regards our use of difference scores in the second analysis, since difference scores do not allow for an analysis of effects regarding absolute levels of evaluative ratings for the two variables from which the difference is computed (e.g., differences between people scoring very low or very high on both measures). We do not consider this to be a major problem, however, since effects regarding absolute differences in ratings of old persons were contained in the first part of the results section, where we focus on the ratings of “old persons” only. The difference between middle-aged and older persons was thus not intended to assess differences in absolute levels of ratings, but was instead used to specifically represent perceptions of age-related changes. Interestingly, the pattern of findings between absolute levels of ratings for older people and for the age-related changes corresponded nicely between the two analyses, indicating most of the variance in the ratings (between domains, gender, and age groups) is due to different evaluations of the “old” person targets rather than reflecting different evaluations of the “middle-aged” targets.

It is also possible that the selection of a 45-year-old comparison target might have mitigated the effects of age on appearance for older women. Age-related appearance changes might be strongest before the age of 45 and thus, the changes in appearance between 45 and 65 might not be of much more importance for women’s evaluations. Furthermore, we used verbal instead of pictorial material, which might also lead to an underestimation of the effects of appearance on the ratings of older women. However, the study by Teuscher and Teuscher (2007) that employed pictorial material also did not yield strong evidence for a double standard concerning appearance.

In addition, most of the research on gender and age stereotypes thus far has been conducted in Western societies (especially the US); this is also the case for our study that took place in Germany. Considering the strong influence of culture on gender roles and aging processes (e.g., Bergman et al. 2013; Kamilar et al. 2000), it would be an interesting avenue for future research to investigate the role of culture on the interplay of the perceptions of older men and women.

With regard to the implications of our findings, it should be noted that perceptions of age-related changes of older men and women might not fully match self-perceptions of these age-related changes and their subjective evaluations. For example, even though men might tend to perceive stronger declines with regard to their physical fitness and attractiveness than women do, their self-esteem might still be less affected by these changes due to the fact that men might put less emphasis on these attributes; instead, social evaluations of older men might focus on other characteristics. Conversely, even though perceived age-related changes regarding competence at work were less negative for men compared to women, having difficulties to compete with younger workers and changes related to retirement might still affect men more than women due to the centrality that work and occupational status have for the self-views of men (Cinamon and Rich 2002; Lee and Owens 2002; but see also Sharabi and Harpaz 2011).

With respect to the interpretation of our findings, one crucial question remains: What constitutes the basis of the resulting domain-specific differences in ratings of older men and women? Research on perceived personality changes during the aging process shows that older persons are perceived to possess different characteristics than younger persons (e.g., Chan et al. 2012; Grühn et al. 2011). And even though actual gender differences in life span personality changes seem not to be pronounced (Chapman et al. 2007; Ferguson 2010; Lippa 2010) it would be interesting to investigate whether they are nevertheless perceived to be there (cf. Haslam et al. 2007), and whether those perceptions might interact with the requirements that are posed in different life domains. However, it may also be that it is exactly those requirements that are perceived to change over the life span in a gender-specific way, and since women and men are ascribed different characteristics regardless of their own age (Lippa 2010), they are perceived to be more or less effective, happy, or in control of their life in a certain domain. Future research will have to disentangle and further illuminate those underlying processes of gender- and domain-specific age stereotypes.

As a final remark, we want to make clear that we do not underestimate the fact that aging is a gendered process and that overall, women do face grave challenges and discrimination during the aging process (Antonucci et al. 2010), especially when it comes to financial and work-related matters (for retirement planning, see Noone et al. 2010). Furthermore, even though older women were rated more positively in most domains, those domains might be perceived as being less important and thus they might not have such a strong influence on the overall perception of a person. Still, considering that men were rated more negatively in many domains, especially those regarding social activities, we think that a closer look on the interaction of life domains and gender when it comes to age stereotypes might lead to a more differentiated understanding on where older men and women are evaluated rather positively or negatively. Highlighting those domain-specific, gender-related differences in age stereotypes is a necessary requirement to be able to specifically target interventions that in the long run might lead to a more positive aging experience for men and women in diverse societies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by two Grants of the VolkswagenStiftung (AZ II/83 142, AZ 86 758) to Klaus Rothermund.

Footnotes

Besides the 65-year-old and the 45-year-old targets, 25-year-old men and women were also rated in the questionnaire; these data are not presented here, but can be obtained from the authors.

We additionally ran the analysis with the between person factor “order”. The only effect that was marginally significant was the interaction target gender × age group × order F(2, 272) = 3.10, p = 0.047, η 2p = 0.02, which was due to the younger participants rating women more positively if male targets had to be rated first. Due to the small effect that was not of theoretical interest, we decided to drop “order” from further analyses.

Since for the finances domain, the third-item (65-/45-year-old men/women…provide for others financially—do not provide for others financially) had low loadings on the finances factor for all target age groups, we decided to use a two-item scale for this domain. The same was done for the domain of work, where the third-item (65-/45-year-old men/women…have a negative attitude toward retirement—have a positive attitude toward retirement) had low loadings for the middle-aged targets.

All effects involving the age group factor remained significant after including different background variables (education, marital status, health status) as additional factors into the analyses, indicating that none of the age group effects can be explained in terms of differences in these variables.

Analyzing appearance as a single item yielded similar results. Women rated older women as having a more positive appearance than older men, especially among middle-aged and older participants. And even though older targets were generally rated less positively in their appearance than middle-aged targets, women gave less negative ratings of older women’s appearance compared to older men’s. Taken together, the more positive rating of older women compared to older men was true even if we looked only at the ratings for physical appearance.

References

- Aidman EV, Carroll SM. Implicit individual differences: relationships between implicit self-esteem, gender identity, and gender attitudes. Eur J Pers. 2003;17:19–36. doi: 10.1002/per.465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Blieszner R, Denmark FL. Psychological perspectives on older women. In: Landrine H, Russo NF, editors. Handbook of diversity in feminist psychology. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 233–257. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE. Gendered experiences in midlife: implications for age identity. J Aging Stud. 2005;19:163–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, von Rohr C. Gendered perceptions of aging: an examination of college students. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2008;67:359–386. doi: 10.2190/AG.67.4.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman YS, Bodner E, Cohen-Fridel S. Cross-cultural ageism: ageism and attitudes toward aging among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:6–15. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner E, Bergman YS, Cohen-Fridel S. Different dimensions of ageist attitudes among men and women: a multigenerational perspective. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:895–901. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JE, Lalonde RN. Social identification and gender-related ideology in women and men. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40:59–77. doi: 10.1348/014466601164696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canetto SS, Kaminski PL, Felicio DM. Typical and optimal aging in women and men: is there a double standard? Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1995;40:187–207. doi: 10.2190/RX0U-T56B-1G0F-266U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper C, Rothermund K. Gender self-stereotyping is context dependent for men but not for women. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2012;34:434–442. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.712014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casper C, Rothermund K, Wentura D. The activation of specific facets of age stereotypes depends on individuating information. Soc Cogn. 2011;29:393–414. doi: 10.1521/soco.2011.29.4.393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W, McCrae RR, De Fruyt F, Jussim L, Löckenhoff CE, De Bolle M, et al. Stereotypes of age differences in personality traits: universal and accurate? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;103:1050–1066. doi: 10.1037/a0029712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Lyness JM. Gender differences in five factor model personality traits in an elderly cohort. Pers Ind Differ. 2007;43:1594–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon R, Rich Y. Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: implications for work–family conflict. Sex Roles. 2002;47:531–541. doi: 10.1023/A:1022021804846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeArmond S, Tye M, Chen PY, Krauss A, Rogers DA, Sintek E. Age and gender stereotypes: new challenges in a changing workplace and workforce. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;36:2184–2214. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00100.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch FM, Zalenski CM, Clark ME. Is there a double standard of aging? J Appl Soc Psychol. 1986;16:771–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01167.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MK, Wahl H-W. Awareness of age-related change: examination of a (mostly) unexplored concept. J Gerontol B Psychol. 2010;65:340–350. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekman AB, Hirnisey L. The effect of context on the silver ceiling: a role congruity perspective on prejudiced responses. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:1353–1366. doi: 10.1177/0146167207303019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Steffen VJ. Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46:735–754. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Wood W, Diekman AB. Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: a current appraisal. In: Eckes T, Trautner HM, editors. The developmental social psychology of gender. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 123–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ. A meta-analysis of normal and disordered personality across the life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:659–667. doi: 10.1037/a0018770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluth S, Ebner NC, Schmiedek F. Attitudes toward younger and older adults: the German aging semantic differential. Int J Behav Dev. 2010;34:147–158. doi: 10.1177/0165025409350947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Button CM, Hannah TE, Ross AS. Uncovering the multidimensional nature of stereotype inferences: a within-participants study of gender, age, and physical attractiveness. Curr Res Soc Psychol. 2002;8:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Grühn D, Gilet A-L, Studer J, Labouvie-Vief G. Age-relevance of person characteristics: persons’ beliefs about developmental change across the lifespan. Dev Psychol. 2011;47:376–387. doi: 10.1037/a0021315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Bastian B, Fox C, Whelan J. Beliefs about personality change and continuity. Pers Ind Dif. 2007;42:1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Garstka TA, Shaner JL, Strahm S. Stereotypes of the elderly held by young, middle-aged, and elderly adults. J Gerontol. 1994;49:P240–P249. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.P240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamilar CB, Segal DL, Qualls SH. Role of gender and culture in the psychological adjustment to aging. In: Eisler RM, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of gender, culture, and health. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 405–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME. Age, gender, and occupational label: a test of social role theory. Psychol Women Quart. 1996;20:361–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00305.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Wagner LS. Attitudes toward older adults. In: Nelson TD, editor. Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 2002. pp. 129–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Deaux K, Miele M. Stereotypes of young and old: does age outweigh gender? Psychol Aging. 1991;6:19–27. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Stockdale GD, Whitley EB, Johnson BT. Attitudes toward younger and older adults: an updated meta-analytic review. J Soc Issues. 2005;61:241–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00404.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kornadt AE, Rothermund K. Contexts of aging: assessing evaluative age stereotypes in different life domains. J Gerontol B Psychol. 2011;66:547–556. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornadt AE, Rothermund K. Internalization of age stereotypes into the self-concept via future self-views: a general model and domain-specific differences. Psychol Aging. 2012;27:164–172. doi: 10.1037/a0025110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laditka SB, Fischer M, Laditka JN, Segal DR. Attitudes about aging and gender among young, middle age, and older college-based students. Educ Gerontol. 2004;30:403–421. doi: 10.1080/03601270490433602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latrofa M, Vaes J, Cadinu M, Carnaghi A. The cognitive representation of self-stereotyping. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2010;36:911–922. doi: 10.1177/0146167210373907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latrofa M, Vaes J, Cadinu M. Self-stereotyping: the central role of an ingroup threatening identity. J Soc Psychol. 2012;152:92–111. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2011.565382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Owens RG. Men, work and gender. Australian Psychol. 2002;37:13–19. doi: 10.1080/00050060210001706626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR. Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Cur Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippa RA. Gender differences in personality and interests: when, where, and why? Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4:1098–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00320.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Park SH, O’Connor A. Gender stereotypes as situation–behavior profiles. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan C. Is there a double standard of aging? Older men and women and ageism. Educ Gerontol. 2008;34:782–787. doi: 10.1080/03601270802042123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noone J, Alpass F, Stephens C. Do men and women differ in their retirement planning? Testing a theoretical model of gendered pathways to retirement preparation. Res Aging. 2010;32:715–738. doi: 10.1177/0164027510383531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermund K, Brandtstädter J. Age stereotypes and self-views in later life: evaluating rival assumptions. Int J Behav Dev. 2003;27:549–554. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman LA, Goodwin SA. Gender differences in automatic in-group bias: why do women like women more than men like men? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87:494–509. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi M, Harpaz I. Gender and the relative centrality of major life domains: changes over the course of time. Community Work Fam. 2011;14:57–62. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2010.506033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S (1972) The double standard of aging. The Saturday Review, New York, September 23, pp 29–38

- Swazina KR, Waldherr K, Maier K. Gender-specific ideals over time. Z Diff Diagn Psychol. 2004;25:165–176. doi: 10.1024/0170-1789.25.3.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher U, Teuscher C. Reconsidering the double standard of aging: effects of gender and sexual orientation on facial attractiveness ratings. Pers Indiv Diff. 2007;42:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH., Jr Images of old men’s masculinity: still a man? Sex Roles. 2006;55:633–648. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S. Age and gender in relation to body attitudes: is there a double standard of aging? Psychol Women Quart. 1997;21:549–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00130.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]