Abstract

Evidence on trends in prevalence of disease and disability can clarify whether countries are experiencing a compression or expansion of morbidity. An expansion of morbidity, as indicated by disease, has appeared in Europe and other developed regions. It is likely that better treatment, preventive measures, and increases in education levels have contributed to the declines in mortality and increments in life expectancy. This paper examines whether there has been an expansion of morbidity in Catalonia (Spain). It uses trends in mortality and morbidity and links these with survival to provide estimates of life expectancy with and without diseases and mobility limitations. We use a repeated cross-sectional health survey carried out in 1994 and 2011 for measures of morbidity, and information from the Spanish National Statistics Institute for mortality. Our findings show that at age 65 the percentage of life with disease increased from 52 to 70 % for men, and from 56 to 72 % for women; the expectation of life with mobility limitations increased from 24 to 30 % for men and from 40 to 47 % for women between 1994 and 2011. These changes were attributable to increases in the prevalence of diseases and moderate mobility limitation. Overall, we find an expansion of morbidity along the period. Increasing survival among people with diseases can lead to a higher prevalence of diseases in the older population. Higher prevalence of health problems can lead to greater pressure on the health care system and a growing burden of disease for individuals.

Keywords: Healthy life expectancy, Diseases, Mobility limitations, Spain

Introduction

In recent years, researchers have tried to understand whether the ideal of living longer and healthier lives will be accomplished. Mortality and morbidity research is crucial to address such a complex issue. Many countries have experienced a continuing decline in mortality during the past half-century, influenced by overall reductions among older individuals after retirement age (Vaupel et al. 1998; Robine 2011; Janssen and Kunst 2005) with an increasing chance of surviving to the fourth age (Baltes and Mayer 1998). In the future, mortality changes at very old ages will be compelling due to mortality declines from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, which are attributable to medical prevention, better treatment of diseases, and increases in education levels (Crimmins et al. 2010). However, living to older ages has raised the question of how healthy longer life will be. Surprisingly, countries experiencing longer lives at very old ages, e.g., southern European countries, do not appear to have better health and they often rank among the worst in indicators of disability. For instance, Spain is one of the European countries with the longest life expectancy at birth in 2009 (HMD 2013) but the highest levels of functioning problems (Solé-Auró and Crimmins 2013), coupled by facing a wave of increasing financial and social costs of long-term care (Alcañiz et al. 2011).

Taking into account these demographic and health changes, our work tries to understand whether this long life is being accompanied by an increase in the time of living in good health, examining changes in the prevalence of potentially fatal chronic diseases and loss of mobility along with change in mortality in a Mediterranean region of over seven million people (Catalonia, Spain). The interest of studying both chronic diseases and mobility functions is to see how and when such hazardous health conditions appear in the pathway of human life span, and how long they last until death ensues. It is worth noting that having more chronic diseases may cause functional limitations in the population. In order to clarify whether there have been changes in the transition from health to disease or mobility limitations, we will look at three chronic conditions which can result in death, as well as mobility limitations, and link these with mortality. Hence, we will provide estimates of life expectancy with and without these conditions during the last two decades. In the following sections we summarize the recent general trends in health, morbidity, disability, and mortality, paying special attention to Spain. We begin with a discussion of the dynamics of health to see whether there is a redistribution of disease and disability in the later stages of life. Afterward, we study trends in major diseases and mobility limitations, and estimate healthy life expectancies linked to disease and disability. In the end, our main aim is to investigate the implications of changes in the prevalence of conditions on the length of life with and without disease and mobility limitations in the life table population.

The dynamics of health at old ages

As Gruenberg (1977), Manton (1982), and Fries (1980) pointed out 30 years ago, mortality declines at older ages could be due to (1) an expansion of morbidity (people live longer, but less healthy), (2) a compression of morbidity (death is delayed, disease starts later), or (3) a dynamic equilibrium between increased prevalence of disability and a reduction in its severity. These three theories have contributed to the development of further research on health trends (Robine and Michel 2004) and are important for service planning, since the three imply quite different pressures on health systems and services.

The optimistic point of view of aging proposed by Fries (1980), a compression of morbidity, pointed out that morbidity is compressed into a shorter period before death, increasing the proportion of life free of disease. There is now an open debate about this theory within a large body of research in demography, epidemiology, and public health. In the 1990s, an increase in life expectancy was accompanied in most countries by an increase in time lived without disability (Cai and Lubitz 2007) or moderate limitations (Graham et al. 2004), indicating a dynamic equilibrium, as only a small delay in the onset was found. In the early 2000s, a continuation of the dynamic equilibrium of the 1990s (Cheung and Yip 2010; Galenkamp et al. 2012) and an emerging expansion in some forms of severe disability in the older populations were observed (Hashimoto et al. 2010). Thus, there was an expansion of morbidity in the late 1990s and early 2000s as the prevalence of chronic diseases and some risk factors appear to have been increasing in both Europe and other developed regions (Gutiérrez-Fisac et al. 2002; Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez 2011). Spain, like other countries (Freedman et al. 2004; Cambois et al. 2008), experienced a compression of disability since the 1980s (Sagardui-Villamor et al. 2005). However, for diseases, most prevalences in the Spanish population have risen until advanced ages (Martínez-Beneyto et al. 2011). Further investigation will provide evidence on survival and morbidity trends in Spain.

Trends in diseases

At the beginning of the past century, infectious diseases accounted for the majority of deaths, but now chronic diseases dominate. Due to medical improvements people often live with diagnosed diseases for long periods of time. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major health problem across the world and is now responsible for approximately one-third of the deaths in both developing and developed countries (Deaton et al. 2011). CVD among European populations is mainly attributable to classical risk factors such as diets high in saturated fats, elevated cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle. However, it is important to notice that developed countries have enjoyed substantial mortality declines in CVD (O’Flaherty et al. 2013; Bhatnagar et al. 2011). Within Europe, southern European countries are better off in terms of CVD mortality risk than those in the north. CVD in Spain has also experienced a downward trend (Ruiz-Ramos et al. 2008), and it now represents the second lowest coronary mortality rate in Europe after France (Sans et al. 1997).

Hypertension is one of the most prevalent universal risk factors, especially in patients with established CVD, and accounts for 6 % of deaths worldwide (Murray and Lopez 1997). Around 11 % of all disease burden in developed countries and about a quarter of European heart attacks are due to hypertension, while hypertensive individuals have twice the risk of experiencing heart attack compared to those without a history of hypertension (Nichols et al. 2012). The treatment of hypertension has improved dramatically over the past decades, contributing to the reductions of mortality incidence due to CVD. In Spain, substantial efforts have been made to diminish hypertension rates (Llisterri et al. 2012); however, the treatment strategy adopted has not been enough to slow down the increases through the last decade (Cordero et al. 2011).

Diabetes is another chronic disease that substantially contributes to increase the risk of CVD, and also magnifies the effect of other risk factors (high cholesterol levels, raised blood pressure, smoking, and obesity). People with diagnosed diabetes have three times the risk of a heart attack compared to those without (Nichols et al. 2012). Diabetes trends in Europe are alarming, given the notable increase in prevalence in most countries (Passa 2002). Spain is not an exception and diabetes has become an important public health problem because of its growing magnitude and its impact on CVD (Ruiz-Ramos et al. 2006). A combination of several factors, such as changes in the diagnostic criteria for diabetes, population aging, and lower mortality among persons with diabetes, has led to an increase in disease prevalence (Valdés et al. 2007).

Disability and physical functioning trends

The first studies on disability appeared in the late 1960 and 1970s with a general conclusion that disability did not decrease during this time period (Wilmoth 1997; Kaplan 1991; Crimmins et al. 1997). Later on disability declines were reported, particularly for the older population and during the 1980s, in developed countries like Japan, the United States, or France (Jacobzone et al. 1999; Robine et al. 2002). In the 1990s, the worldwide rates of disability indicated a dynamic equilibrium between prevalence and severity (Parker and Thorslund 2007; Moe and Hagen 2011; Crimmins et al. 2009), and mixed patterns have appeared in recent years. The disability distribution within Europe is not uniform. Some European countries have shown an expansion of disability among mid-adults (Cambois et al. 2012; Lafortune et al. 2007), while other countries, like the Netherlands, have experienced high and stable prevalence of disability. However, disability rates are expected to increase in the future due to the aging of the population (Picavet and Hoeymans 2002). Southern Europeans are expected to spend a higher percentage of their lives with disability compared to the people from the north (Minicuci et al. 2004). Nevertheless, Spain experienced a compression of disability and the postponement of severe disability onset to more advanced ages from the 1980s to the present (Zunzunegui et al. 2006; Sagardui-Villamor et al. 2005).

In the progressive deterioration of health, the mobility limitations that people suffer at old ages are an anticipated stage before the development of disability. The trends in prevalence of functioning problems in the U.S. show reduced functioning ability of people approaching old ages in the early 2000s (Martin et al. 2010; Lakdawalla et al. 2004). These results contrast unfavorably with the ones obtained two decades ago, particularly in the U.S., when research showed improvements in physical functioning problems in the 1990s (Crimmins 2004). However, there is a less clear worldwide pattern between the 1990 and 2000s. For instance, in the 1990s, increasing functional limitations were found for England, while reduced prevalences appeared among older Norwegians, and stable rates were seen in the Netherlands (Moe and Hagen 2011; Martin et al. 2012; Hoeymans et al. 2012). Knowing these trends is crucial, because an increase in the number of older persons may raise the demand for health care services, whereas decreasing prevalences of functional limitation among them may counteract this demographic effect.

Methodology

Data

We used data obtained between 1994 and 2012 from the Catalan Health Survey (ESCA) (Generalitat de Catalunya 2013). The Department of Health in Catalonia (Spain)—a highly populated Mediterranean region located in the northeast corner of the Iberian Peninsula—is responsible for the technical execution of the survey. The ESCA is the only source of microdata for Catalonia, containing information on morbidity in relation with socio-demographic variables, health behaviors, and individual’s state of health. The sample follows a stratified design, based on age, gender, and geographical area. The random collection of the data is performed using personal interviews. The questionnaires of each time period are designed to be comparable.

This cross-sectional survey was collected in 1994 and continuously during the period 2010–2012 (Alcañiz et al. 2014). In the last time period, we combined data of the last 3 years available (2010, 2011, and 2012) to increase our sample size, and considered 2011 our midpoint year. Hence, when we refer to the year 2011 in our analysis, we include data from the years 2010, 2011, and 2012. Our sample comprised 20,433 Catalan non-institutionalized residents (12,584 people in 1994 and 7,849 people in 2011) randomly selected, aged 15 years and older. Since mortality is not appended to the ESCA, mortality information came from the official life tables from the Spanish National Statistics Institute database (INE 2012).

Measures

We use three indicators of the presence of potentially fatal chronic diseases: hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. Similar question wording is reported in the two time periods in response to the question: “Do you have or has a doctor ever told you that you have any of the following conditions…?”, followed by a list of chronic medical disorders including hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease.

In this survey, people also reported whether they had difficulties or limitations in performing a set of mobility functions. We have chosen an indicator of mobility limitations based on a positive answer (yes versus no) to at least one of these three items: (1) mobility problems, such as the inability to move out of the house without receiving help from another person; (2) walking problems, which may require using special equipment; and (3) other important mobility limitations, such as the difficulty to walk up and down a flight of stairs, and standing, without using special equipment.

Statistical analyses

We first examine the recent changes in the prevalence of diseases, which are prominent causes of mortality at older ages, and the presence of mobility limitations. Healthy life expectancy is estimated using the Sullivan approach (Sullivan 1971), a prevalence-based method of dividing life table years lived in an age interval, into years with and without health disorders, based on the specific health prevalence of that age group. We also show 95 % confidence intervals for estimated life expectancy with and without diseases (Jagger 1999). Error margins are constructed based on statistical sampling analysis (Kish 1995; Levy and Lemeshow 1991). If we set a 95 % confidence level, estimated sampling errors are around ±3 % for all percentages, except for ages 80-plus, where samples are smaller and the errors range between ±5 and ±7 %. Using the healthy life expectancy calculations, we estimate the expected age that chronic diseases or mobility limitations appear in life by gender in each time period. Analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 12 (StataCorp).

Results

Trends in prevalences of diseases and functional limitations

Table 1 shows the percentages of people with hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease, and ensuing mobility limitations. Results are stratified by age groups and gender over time.

Table 1.

Prevalence (percent) of diseases and mobility problems by age and sex in Catalonia (Spain). Individuals aged 15-plus

| Age | Prevalence of hypertension | Prevalence of diabetes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| 1994 | 2011 | Difference | 1994 | 2011 | Difference | 1994 | 2011 | Difference | 1994 | 2011 | Difference | |

| 15–29 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| 30–39 | 5.7 | 8.4 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | −0.4 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| 40–49 | 10.9 | 19.6 | 8.7 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 1.5 |

| 50–59 | 19.2 | 36.0 | 16.8 | 29.8 | 24.6 | −5.2 | 5.6 | 11.2 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 5.7 | −0.6 |

| 60–69 | 28.2 | 49.4 | 21.2 | 36.8 | 48.9 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 18.7 | 6.4 | 12.5 | 13.9 | 1.4 |

| 70–79 | 29.9 | 53.5 | 23.6 | 45.5 | 62.0 | 16.5 | 12.0 | 22.7 | 10.7 | 13.0 | 15.9 | 2.9 |

| 80+ | 26.7 | 50.3 | 23.6 | 42.3 | 68.3 | 26.0 | 7.4 | 22.8 | 15.4 | 9.0 | 22.9 | 13.9 |

| Age | Heart diseases | Mobility limitations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| 1994 | 2011 | Difference | 1994 | 2011 | Difference | 1994 | 2011 | Difference | 1994 | 2011 | Difference | |

| 15–29 | 1.5 | 1.1 | −0.4 | 1.5 | 1.1 | −0.4 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| 30–39 | 1.9 | 1.8 | −0.1 | 1.8 | 1.4 | −0.4 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| 40–49 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 1.2 | −2.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 3.4 | 8.0 | 4.6 |

| 50–59 | 7.9 | 6.0 | −1.9 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 0.4 | 6.8 | 9.8 | 3.0 | 11.9 | 10.5 | −1.4 |

| 60–69 | 13.0 | 17.8 | 4.8 | 11.6 | 11.3 | −0.3 | 12.6 | 12.4 | −0.2 | 20.1 | 19.9 | −0.2 |

| 70–79 | 18.9 | 27.8 | 8.9 | 18.5 | 20.5 | 2.0 | 19.0 | 24.6 | 5.6 | 34.3 | 37.8 | 3.5 |

| 80+ | 22.7 | 36.6 | 13.9 | 22.6 | 30.9 | 8.3 | 44.5 | 52.0 | 7.5 | 57.4 | 69.5 | 12.1 |

Source Catalan Health Survey, 1994 and 2011. Survey weights are used in this table

Prevalence of hypertension increased over time, with clear gender differences. For men, prevalence of hypertension increased over almost the two-decade time period, except at younger ages (15–39) where rates are low and differences between periods are not statistically significant. After age 60, increase in the percentage of males with hypertension is similar over time. This is not the case for women, who survived longer with diseases and show significant increases after age 60 over time. Diabetes is our second chronic disease and increases are generally seen over time. These increments are statistically significant after age 50 for males and only in the oldest ages for females (80-plus). Diabetes rates diminished for both genders after age 70 up to 1994. This is not the case in recent dates, where prevalence for men is steady after age 70 and even grows for women. Our third health condition is heart disease. In both periods, the prevalence of heart disease rises as individuals get older. Among men aged 70-plus, increases of heart disease prevalences are noticed in the two-decade period, while this trend is not so clear for women. Women rates of heart disease are quite similar over time, with significant increases only after age 80.

Table 1 concludes with our mobility measure. Men and women aged 70-plus experience increments in the prevalence of mobility problems between 1994 and 2011. Larger increments are seen in the oldest age (80-plus). Higher prevalences of mobility limitations are found for women than for men almost at all ages over time.

Changes in healthy life expectancy: 1994–2011

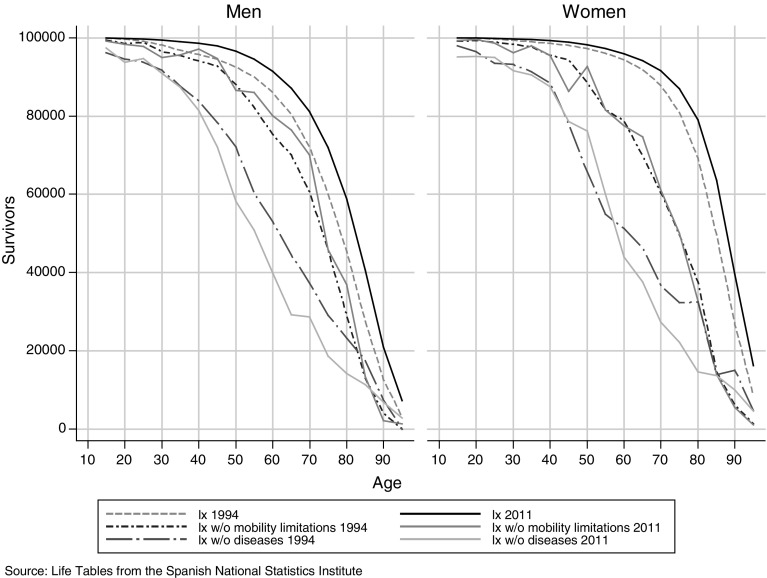

Few analyses on healthy life expectancy in Spain or other Mediterranean countries have examined the changes in life expectancy with disease or mobility limitations (Sagardui-Villamor et al. 2005). Figure 1 shows the increase in overall survival between 1994 and 2011. This curve indicates a rise in survival time over these years, so people are expected to live longer now than two decades ago. Figure 1 also shows the curves representing survival without mobility limitations and without diseases over time. For both genders, survival curves without diseases are shifted leftward, indicating less time of surviving without diseases. A particularity for women between ages 45 and 55 is seen as curves show more time of surviving without diseases in recent periods. Survival curves without disease are much more linear than those for mobility limitations or full life, especially after age 40. This steady negative slope in the survival curve without diseases indicates that the onset of diseases after age 40 is not as concentrated in older ages as is death. It is worth noting that survival curves without mobility limitations are closer to overall curves—more for men than for women—showing that females spend a longer period of their late life with mobility problems. The curves indicating survival without mobility limitations are above those representing survival without diseases, meaning that mobility limitations occur at older ages than the diseases we consider.

Fig. 1.

Survivors in the life table population

Table 2 gives the values of the expected lifetime with and without diseases and mobility limitations over time at 15 and 65 years of age. Confidence intervals are shown and due to large sample sizes their precision is quite good (hardly exceeding 1 year around the healthy life expectancy). Life expectancy increases along the whole period, showing faster increments in younger cohorts. At age 15, life expectancy increased 4.6 years for men and 3.2 years for women; at age 65, both genders show the same gain in life expectancy (2.5 years).

Table 2.

Life expectancy (LE), life expectancy with and without diseases, and life expectancy with and without mobility limitations for men and women: 1994 and 2011

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 2011 | 1994 | 2011 | |

| Age 15 | ||||

| LE | 60.2 | 64.8 | 67.5 | 70.7 |

| Without disease | 47.1 | 43.1 | 48.5 | 46.6 |

| CI | (46.5, 47.5) | (42.1, 43.9) | (47.7, 49.3) | (45.5, 47.5) |

| With at least one disease | 13.1 | 21.7 | 19.0 | 24.1 |

| % With diseases/LE | 22 | 33 | 28 | 34 |

| Able to function | 55.5 | 57.5 | 57.6 | 57.5 |

| CI | (55.1, 55.9) | (56.7, 58.0) | (56.9, 58.1) | (56.7, 58.2) |

| Unable to function | 4.7 | 7.3 | 9.9 | 13.2 |

| % Unable to function/LE | 8 | 11 | 15 | 19 |

| Age 65 | ||||

| LE | 16.2 | 18.7 | 20.2 | 22.7 |

| Without disease | 7.7 | 5.7 | 8.8 | 6.3 |

| CI | (8.1, 9.0) | (4.9, 6.3) | (8.1, 9.5) | (5.5, 7.1) |

| With at least one disease | 8.5 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 16.3 |

| % With diseases/LE | 52 | 70 | 56 | 72 |

| Able to function | 12.3 | 13.0 | 12.1 | 12.1 |

| CI | (11.9, 12.7) | (12.3, 13.5) | (11.5, 12.6) | (11.3, 12.7) |

| Unable to function | 3.9 | 5.7 | 8.1 | 10.6 |

| % Unable to function/LE | 24 | 30 | 40 | 47 |

Source Catalan Health Survey, 1994 and 2011. Survey weights are used in this table. Chronic diseases include hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. Mobility limitations include (1) mobility problems, such as the inability to move out of the house without receiving help from another person; (2) walking problems, which may require using special equipment; and (3) other important mobility limitations, such as the difficulty to walk up and down a flight of stairs, and standing, without using special equipment

LE life expectancy, CI confidence intervals

Over time, men aged 65 experienced increments of life expectancy with disease (4.5 years), and consequently a decrease of years without disease (2 years). If we compare increases in men’s overall life expectancy with decreases in men’s life expectancy without disease, we observe an expansion of morbidity: men live longer but the onset of disease is earlier. This trend is also true for women. This expansion can be easily seen when we look at the percentage of life spent with disease over time: at age 65, this percentage goes from 52 to 70 % for men and from 56 to 72 % for women. Similar patterns are observed at age 15.

In recent times, we also see different patterns on the gender gap in life expectancy with diseases. Table 3 presents the expected age that the health disorders examined here appear by gender over time. For instance, in 2011, 15-year-old men will suffer from these diseases a third of their life, starting, on average, at age 58.1; the same portion of men’s life with diseases is identified for women, but they will start suffering from the diseases considered here later in life as they live longer (age 61.6). Therefore, 3.5 years was the gender difference in 2011; but only 1.4 years in 1994 (starting at age 62.1 for men and 63.5 for women). This gender gap decreases, but does not vanish, at older ages: 1.1 years in 1994, and only a scarcely significant 0.6 years in 2011. At older ages, women’s health declines more sharply than men’s and the gap between the genders fades out.

Table 3.

Expected age that chronic diseases or mobility limitations appear for men and women: 1994 and 2011

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 2011 | 1994 | 2011 | |

| Chronic diseases | ||||

| Age 15 | 62.1 | 58.1 | 63.5 | 61.6 |

| Age 65 | 72.7 | 70.7 | 73.8 | 71.3 |

| Mobility functioning loss | ||||

| Age 15 | 70.5 | 72.5 | 72.6 | 72.5 |

| Age 65 | 77.3 | 78.0 | 77.1 | 77.1 |

Source Catalan Health Survey, 1994 and 2011. Chronic diseases include hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. Mobility limitations include (1) mobility problems, such as the inability to move out of the house without receiving help from another person; (2) walking problems, which may require using special equipment; and (3) other important mobility limitations, such as the difficulty to walk up and down a flight of stairs, and standing, without using special equipment

Temporal patterns for mobility limitations are slightly different. At 65, the percentage of life with functioning problems has risen from 24 to 30 % for men and from 40 to 47 % for women from 1994 to 2011. On average, men aged 65 in 1994 have experienced mobility problems at 77.3 years; in 2011 this activity limitation appears at 78.0, and women at age 65 have suffered mobility problems at 77.1 in both years (Table 3). Therefore, the ages of onset of impairment are very similar, which denotes no relevant gender difference concerning life expectancy without mobility limitations over time.

Discussion

Regarding the health of the population in Catalonia (Spain), we found that mobility limitations occur later in life than the potentially fatal diseases studied. These chronic diseases arrive earlier for men than women, while the onset of mobility limitations for those who were able to function at 65 appears at a similar age by gender at both time periods. Specifically, the prevalence of hypertension increases over time, although part of these increments may be due to better health surveillance that makes people aware of the conditions they have (Howard et al. 2010). Concerning diabetes, the fact that in recent dates prevalences do not decrease at old ages suggests that better monitoring and treatment have succeeded in avoiding premature death due to health complications caused by this disorder for both genders (Valdés et al. 2007). Prevalence of heart disease increases until very old ages over time, which may be a result of early detection plans, or a consequence of longer survival due to better treatment. Part of the gender differences in the prevalence of heart disease may be explained, as pointed out by Flink et al. (2013), by the fact that women are less likely to know the symptoms of heart failure, which may delay requesting the medical services until life is already seriously compromised. Since life expectancy is longer for women than men, women will spend a higher portion of their lives with both chronic diseases and mobility limitations.

Our findings reveal an outstanding expansion of potentially fatal diseases along the period at the oldest age, as people live almost 5 years longer with diseases in 2011 than at the beginning of the 1990s. This expansion is attributable to both a longer life (mostly for women) and an earlier onset of diseases (especially for men), which translates to higher incidence as pointed out by Solé-Auró et al. (2013) in some European countries. Increasing survival among people with diseases has led to a higher prevalence of diseases in the Catalan population. Our results may be picking up not only a higher risk of illness at younger ages, but also an improvement in early control and diagnosis of diseases, particularly hypertension and diabetes, over the years. Due to the earlier onset of disease in the lifetime, individuals affected are not only the oldest, but also working age people. It is likely that the rise in the prevalence of health disorders, particularly heart disease, is mainly explained by better knowledge and treatment of the diseases, increased contacts with medical doctors, and screening campaigns (Ford et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2012). Either way, a scenario of a higher prevalence of diagnosed health problems and longer disease-specific survival can lead to a greater pressure on the health care system, compounded by the fact that in Spain this system is universal and provides appropriate basic health care coverage for all. This effect is lessened taking into account that early diagnosis helps prevent the arrival of advanced stages of the disease that often imply substantial medical expenses. In addition, regarding individual quality of life, a timely diagnosis usually implies medical care, which can extend life in relatively good health, or at least lead to less severe illness. In sum, disease expands, although we cannot assert that quality of life deteriorates. There may be an effect of decreased severity as a consequence of better monitoring of diseases, which would partially explain the increase of the proportion of years with disease. Concerning mobility limitations, little expansion between 1994 and 2011 is found for men and women at age 65, mainly caused by the increments in life expectancy and not by an earlier detection. Nevertheless, the growth on the demand of health care is not necessarily smaller than that for diseases, because the expenses incurred depend on the severity of the disorders and need for care.

Gender differences are also relevant during this time period. Our results show an expansion of the gender gap in life expectancy with diseases at younger ages, but decreases at older ages over time. If the gender gap keeps decreasing at older ages, it may suggest that the mortality advantage of women is influenced by lower prevalence of the diseases we consider in earlier stages in the life cycle. The literature states several causes for these gender differences, such as hormonal differences (Pérez-López et al. 2010). In any case, it has to be taken into account that these results could change if we studied other diseases, such as cancer. Concerning mobility limitations, no relevant changes in gender difference appear over time.

Despite the Spanish advantageous position in CVD mortality rates within Europe, if we want a more healthy society with fewer diseases concentrated at the end of our life, it is important to work on prevention. The strong interrelation among hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease contributes to increased risk of cardiovascular problems and magnifies the effect of several risk factors, such as smoking or obesity (Nichols et al. 2012). Much of the CVD burden worldwide is avoidable, but demands a global approach to prevention (Deaton et al. 2011). For instance, there is a wide field for preventive measures of diabetes and hypertension beginning with simple strategies of primary care, such as the control of body mass index (Lee et al. 2012). Thus, a good control of hypertension is relatively easy to achieve through a healthy lifestyle accompanied by medication in severe cases (Llisterri et al. 2012). Deterioration in mobility associated with old age could be delayed by educating people from youth about the benefits of a regular practice of physical exercise. Further thoughts are necessary on how to improve the key modifiable lifestyles or behavioral risk factors for CVD and functioning loss—smoking, dietary intake, and physical activity (WHO 2009). In fact, any improvement in the prevention or treatment of one of these potentially fatal diseases will have an overall positive effect over the individual health, and therefore over society as a whole.

There are some limitations to the present study that should be noted here. The investigation of disease incidence and longer survival with adverse health conditions would provide clarity, but no longitudinal data for Spain are available. The ESCA does not provide any indicator of disease severity, so we cannot assert that the quality of life related to health has been diminished. Cancer is another important disease to take into account, but our survey does not provide such information in the first year of our analysis. Moreover, since the institutionalized population is not included in our analysis due to lack of data, our findings apply only to the community-dwelling population. While it is often hard to find data on institutionalized population by age, in 2006 the Catalan health authority reported that 0.7 % of the population lived in institutions (Generalitat de Catalunya 2006). The inclusion of this population might result in a slight increase of the prevalence rates for the Catalan population (Lobo et al. 2007); however, it is unlikely that this would be sufficient to change the direction of our findings. While we recognize these limitations, we believe that the analysis presented here is an important step in understanding the trends and dynamics in healthy life expectancy for almost the last two decades in a Mediterranean region.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the funding from NIA R01 AG040176-02, and funding provided from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (ECO2010-21787-C03-01) and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (ECO2012-35584). The authors also acknowledge the Health Catalan Department team for sharing the data.

References

- Alcañiz M, Alemany R, Bolancé C, Guillén M. The cost of long-term care in the Spanish population: comparative analysis between 1999 and 2008. Rev Met Cuant Econ Emp. 2011;12:111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Alcañiz M, Mompart A, Guillén M, Medina A, Aragay JM, Brugulat P, Tresserras R (2014) Nuevo diseño de la Encuesta de Salud de Cataluña (2010–2014): un paso adelante en planificación y evaluación sanitaria. Gacet Sanit (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baltes PB, Mayer KU (1998) The Berlin aging study aging from 70 to 100. Cambridge University Press. http://worldcat.org

- Bhatnagar P, Scarborough P, Wickramasinghe K. P1-93 Trends in the burden of cardiovascular diseases in the UK, 1961–2011. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2011;65(Suppl 1):A92–A93. doi: 10.1136/jech.2011.142976c.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Lubitz J. Was there compression of disability for older Americans from 1992 to 2003? Demography. 2007;44(3):479–495. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambois E, Clavel A, Romieu I, Robine J-M. Trends in disability-free life expectancy at age 65 in France: consistent and diverging patterns according to the underlying disability measure. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5(4):287–298. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambois E, Blachier A, Robine J-M. Aging and health in France: an unexpected expansion of disability in mid-adulthood over recent years. Eur J Pub Health. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K, Yip P. Trends in healthy life expectancy in Hong Kong SAR 1996–2008. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(4):257–269. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0171-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero A, Bertomeu-Martinez V, Mazón P, Facila L, Cosin J, Galve E, Lekuona I, Rodriguez M, Moreno J, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR (2011) Trends in hypertension prevalence, control and guidelines implementation in Spain through last decade. J Am Coll Cardiol 57(14s1):E591–E591

- Crimmins EM. Trends in the health of the elderly. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2004;25(1):79–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.102802.124401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol. 2011;66(1):75–86. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Ingegneri D. Trends in disability-free life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990. Popul Dev Rev. 1997;23(3):555–572. doi: 10.2307/2137572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Hayward MD, Hagedorn A, Saito Y, Brouard N. Change in disability-free life expectancy for Americans 70 years old and older. Demography. 2009;46(3):627–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Garcia K, Kim JK. Are international differences in health similar to international differences in life-expectancy? In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B, editors. International differences in mortality at older ages: dimensions and sources. Panel on understanding divergent trends in longevity in high-income countries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Deaton C, Froelicher ES, Wu LH, Ho C, Shishani K, Jaarsma T. The global burden of cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(4):S5–S14. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318213efcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya. Enquesta de Salut a la població institucionalitzada de Catalunya, 2006. Residències i centres de llarga estada. http://www20.gencat.cat/docs/canalsalut/Home%20Canal%20Salut/Professionals/Temes_de_salut/Gent_gran/documents/espi_cat_65.pdf

- Flink LE, Sciacca RR, Bier ML, Rodriguez J, Giardina EG. Women at risk for cardiovascular disease lack knowledge of heart attack symptoms. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(3):133–138. doi: 10.1002/clc.22092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman V, Crimmins E, Schoeni R, Spillman B, Aykan H, Kramarow E, Land K, Lubitz J, Manton K, Martin L, Shinberg D, Waidmann T. Resolving inconsistencies in trends in old-age disability: report from a technical working group. Demography. 2004;41(3):417–441. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(3):130–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galenkamp H, Braam AW, Huisman M, Deeg DJH. Seventeen-year time trend in poor self-rated health in older adults: changing contributions of chronic diseases and disability. Eur J Pub Health. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Generalitat de Catalunya (2013) Enquesta de Salut de Catalunya (ESCA), Departament de Salut, http://www.gencat.cat/salut/esca

- Graham P, Blakely T, Davis P, Sporle A, Pearce N. Compression, expansion, or dynamic equilibrium? The evolution of health expectancy in New Zealand. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2004;58(8):659–666. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg EM. The failures of success. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1977;55(1):3–24. doi: 10.2307/3349592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Fisac JL, Regidor E, Banegas Banegas JR, Rodríguez Artalejo F. The size of obesity differences associated with educational level in Spain, 1987 and 1995/1997. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2002;56(6):457–460. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.6.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S, Kawado M, Seko R, Murakami Y, Hayashi M, Kato M, Noda T, Ojima T, Nagai M, Tsuji I. Trends in disability-free life expectancy in Japan, 1995–2004. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(4):308–312. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HMD (2013) Human Mortality Database, http://www.mortality.org/

- Hoeymans N, Wong A, van Gool CH, Deeg DJH, Nusselder WJ, de Klerk MMY, van Boxtel MPJ, Picavet HSJ. The disabling effect of diseases: a study on trends in diseases, activity limitations, and their interrelationships. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102(1):163–170. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DH, Thorpe KE, Busch SH. Understanding recent increases in chronic disease treatment rates: more disease or more detection? Health Econ Policy Law. 2010;5(04):411–435. doi: 10.1017/S1744133110000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INE (2012) Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spain. http://www.ine.es

- Jacobzone S, Cambois E, Robine J-M. The health of the older persons in OECD countries: is it improving fast enough to compensate for population ageing? Naciones Unidas: Ministerio de Desarrollo Social; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jagger C. Health expectancy calculation by the Sullivan method: a practical guide. Tokyo: Nihon University, Population Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen F, Kunst AE. Cohort patterns in mortality trends among the elderly in seven European countries, 1950–1999. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(5):1149–1159. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA. Epidemiologic observations on the compression of morbidity: evidence From the Alameda county study. J Aging Health. 1991;3(2):155–171. doi: 10.1177/089826439100300203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kish JL. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lafortune G, Balestat G, Organisation for Economic C-o, Development (2007) Trends in severe disability among elderly people assessing the evidence in 12 OECD countries and the future implications. OECD http://worldcat.org

- Lakdawalla DN, Bhattacharya J, Goldman DP. Are the young becoming more disabled? Health Aff. 2004;23(1):168–176. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Gebremariam A, Vijan S, Gurney JG. Excess body mass index–years, a measure of degree and duration of excess weight, and risk for incident diabetes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(1):42–48. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.166.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy PS, Lemeshow S. Sampling of populations: methods and applications. New York: Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Llisterri JL, Rodriguez-Roca GC, Escobar C, Alonso-Moreno FJ, Prieto MA, Barrios V, González-Alsina D, Divisón JA, Pallarés V, Beato P, on behalf of the Working Group of Arterial Hypertension of the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians Treatment and blood pressure control in Spain during 2002–2010. J Hypertens. 2012;30(12):2425–2431. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283592583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo A, Santos MP, Carvalho J. Anciano institucionalizado: calidad de vida y funcionalidad. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2007;42(Suppl 1):22–26. doi: 10.1016/S0211-139X(07)73584-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG. Changing concepts of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1982;60(2):183–244. doi: 10.2307/3349767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG, Freedman VA, Schoeni RF, Andreski PM. Trends in disability and related chronic conditions among people ages fifty to sixty-four. Health Aff. 2010;29(4):725–731. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG, Schoeni RF, Andreski PM, Jagger C. Trends and inequalities in late-life health and functioning in England. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2012;66(10):874–880. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Beneyto V, Brugulat-Guiteras P, Mompart-Penina A, Rosas-Ruiz A, Tresserras-Gaju R. Impacto de los trastornos crónicos en la esperanza de vida de la población de Cataluña en 1994 y 2006. Med Clin. 2011;137(Suppl 2):9–15. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7753(11)70022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minicuci N, Noale M, Pluijm SMF, Zunzunegui MV, Blumstein T, Deeg DJH, Bardage C, Jylhä M, group ftCw Disability-free life expectancy: a cross-national comparison of six longitudinal studies on aging. The CLESA project. Eur J Ageing. 2004;1(1):37–44. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe J, Hagen T. Trends and variation in mild disability and functional limitations among older adults in Norway, 1986–2008. Eur J Ageing. 2011;8(1):49–61. doi: 10.1007/s10433-011-0179-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9063):1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M, Townsend N, Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A, Scarborough P, Rayner M (2012) European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2012. European Heart Network, Brussels, European Society of Cardiology, Sophia Antipolis

- O’Flaherty M, Buchan I, Capewell S. Contributions of treatment and lifestyle to declining CVD mortality: why have CVD mortality rates declined so much since the 1960s? Heart. 2013;99(3):159–162. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MG, Thorslund M. Health trends in the elderly population: getting better and getting worse. Gerontologist. 2007;47(2):150–158. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passa P. Diabetes trends in Europe. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(S3):S3–S8. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López FR, Larrad-Mur L, Kallen A, Chedraui P, Taylor HS. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease: hormonal and biochemical influences. Reprod Sci. 2010;17(6):511–531. doi: 10.1177/1933719110367829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picavet HSJ, Hoeymans N. Physical disability in The Netherlands: prevalence, risk groups and time trends. Public Health. 2002;116(4):231–237. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine J-M (2011) Age patterns in adult mortality. In: Rogers RG, Crimmins EM (eds) International handbook of adult mortality, vol 2. International Handbooks of Population. Springer, The Netherlands, pp 207–226. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9996-9_10

- Robine J-M, Michel J-P. Looking forward to a general theory on population aging. J Gerontol A. 2004;59(6):M590–M597. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.6.M590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine J-M, Romieu I, Michel J-P, et al. Trends in health expectancies. In: Robine JM, et al., editors. Determining health expectancies. Chichester: Wiley; 2002. pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ramos M, Escolar-Pujolar A, Mayoral-Sánchez E, Corral-San Laureano F, Fernández-Fernández I (2006) La diabetes mellitus en España: mortalidad, prevalencia, incidencia, costes económicos y desigualdades. Gac Sanit 20 (Supl 1):15–24 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Ramos M, Hermosín Bono T, Gamboa Antiñolo F. Tendencias de la mortalidad por enfermedades cardiovasculares en Andalucía entre 1975 y 2004. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2008;82:395–403. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57272008000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagardui-Villamor J, Guallar-Castillón P, García-Ferruelo M, Banegas JR, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Trends in disability and disability-free life expectancy among elderly people in Spain: 1986–1999. J Gerontol A. 2005;60(8):1028–1034. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.8.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans S, Kesteloot H, Kromhout D. The burden of cardiovascular diseases mortality in Europe. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(8):1231–1248. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solé-Auró A, Crimmins EM. The oldest old health in Europe and the United States. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;33(1):1–33. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.33.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solé-Auró A, Michaud PC, Hurd M, Crimmins EM (2013) Disease incidence and mortality among older Americans and European. RAND Labor & Population Working paper [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sullivan DF. A single index of mortality and morbidity. Rockville: Health Services and Mental Health Administration; 1971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés S, Rojo-Martínez G, Soriguer F. Evolución de la prevalencia de la diabetes tipo 2 en población adulta española. Med Clin. 2007;129(9):352–355. doi: 10.1157/13109554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel JW, Carey JR, Christensen K, Johnson TE, Yashin AI, Holm NV, Iachine IA, Kannisto V, Khazaeli AA, Liedo P, Longo VD, Zeng Y, Manton KG, Curtsinger JW. Biodemographic trajectories of longevity. Science. 1998;280(5365):855–860. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2009) Cardiovascular Diseases. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/priorities/en/index.html

- Wilmoth JR. In search of limits. In: Wachter KW, Finch CE, editors. Between Zeus and the salmon. Washington, DC: The Biodemography of Longevity, The National Academies Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Dzayee DA, Beiki O, de Faire U, Alfredsson L, Moradi T. Incidence and case fatality after day 28 of first time myocardial infarction in Sweden 1987–2008. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:1304–1315. doi: 10.1177/1741826711425340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunzunegui MV, Nuñez O, Durban M, de García Yébenes MJ, Otero A. Decreasing prevalence of disability in activities of daily living, functional limitations and poor self-rated health: a 6-year follow-up study in Spain. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18(5):352–358. doi: 10.1007/BF03324830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]