Abstract

The integration within existing health care systems of preventive initiatives to maintain independent living among older people is increasingly emphasized. This article describes the development and refinement of the [G]OLD home visitation programme: an eight-step programme, including a comprehensive geriatric assessment, for the early detection of health and well-being problems among older people (≥75 years) by general practices. A single group post-test study using a mixed model design is performed to evaluate (a) the feasibility of the home visitation programme in general practice, (b) the practical usefulness of the geriatric assessment instrument, and (c) programme implementation with respect to reinventions introduced by general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses (PNs). Within 3 months time, 22 PNs of 18 participating general practices visited 240 community-dwelling older people (mean age = 82.0 years; SD 4.2) who had not been in contact with their general practice for more than 6 months. Mean time investment of the programme per older person was 118.1 min (SD 27.0) for GPs and PNs combined. Evaluation meetings revealed that GPs and PNs considered the home visitation programme to be feasible in daily practice. They judged the geriatric assessment to be useful, although minor adjustments are needed (e.g., lay-out, substitution of tests). PNs often failed to register follow-up actions for detected problems in a care and treatment plan. Future training for PNs should address this issue. No reinventions were introduced that threatened fidelity of implementation. The findings are used to improve the home visitation programme before its evaluation in a large-scale controlled trial.

Keywords: Frailty, Geriatric assessment, Home visit, General practice

Introduction

As the number of older people rises markedly worldwide, health care systems are faced with a growing number of potentially frail older people who suffer from complex, multiple health complaints (Blokstra et al. 2007; Health Council of the Netherlands 2008). The changes in the demand of care among the aging population accompanied by the increased health care costs prompted the focus on the timely identification of health risks among older people that may ultimately be detrimental for maintaining independent living. In Denmark, municipalities are enforced by state law to offer preventive in-home visits to older people aged 75 and over, and several studies have been conducted to understand the best ways to organize the home visits and to determine its most important components (Rubenstein 2007). For example, cooperation between home care and general practitioners (GPs) is stimulated to organize efficient primary care for older people (Vass et al. 2009). In the Netherlands, preventive initiatives for older people are often insufficiently embedded within existing health care systems (Health Council of the Netherlands 2008). More proactive, coherent and multidisciplinary preventive care using a patient-centered approach is needed. GPs, supported by a practice nurse (PN), are increasingly held responsible for this task by the Dutch College of General Practitioners (2007), as they sustain a generalist view and are easily accessible for older people. Hence, many GPs express the need of a structured approach for organizing care for older people that fits into daily clinical practice.

[G]OLD preventive home visitation programme

This state of affairs has resulted in the development of a preventive home visitation programme for older people called [G]OLD: "Getting OLD the healthy way," in two regions in the south of the Netherlands. While prior studies on the effectiveness of preventive home visits showed conflicting results (e.g., Van Haastregt et al. 2000; Elkan et al. 2001), involving the GP seems a promising approach (Vass et al. 2009). We believe home visits can be valuable when embedded within general practices. It fosters multidisciplinary collaboration (between GPs, PNs, and other caregivers), which is one of the key factors for successful care management of people with complex care needs (Bodenheimer and Berry-Millett 2009). Moreover, strong primary care is associated with improved population health (Starfield et al. 2005).

We redesigned care delivery within general practices by applying components of the Chronic Care Model (CCM) (Bodenheimer et al. 2002) and the Guided Care Model (Boult et al. 2008), resulting in a comprehensive protocol that guides general practices in planning and executing geriatric care. Several of the included components have been postulated in reviews as promising components of interventions to prevent functional decline in community-dwelling older people (Daniels et al. 2010; Markle-Reid et al. 2006). The [G]OLD-protocol applies a stepwise approach. First, the PN informs older people about the home visit using an information leaflet and makes an appointment for the home visit by phone (step 1). The PN prepares for the home visit by printing out relevant information from the GPs information system (e.g., medication list, medical history) (step 2). Then, the PN visits older people at home for a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) of their health and well-being using the so-called [G]OLD-instrument (step 3; see details below). Results of the assessment are discussed with the GP (step 4), as well as with the older person (step 5). In case problems or risk situations require attention, the PN and/or the GP formulate a care and treatment plan in accordance with the older person’s needs and wishes (step 6). If applicable, the PN executes the care and treatment plan, for example by referring the older person to individually appropriate professionals (e.g., physiotherapist, occupational therapist) (step 7). In case different professionals need to be involved in follow-up actions, planning optimal care for the older person is discussed in regular multidisciplinary meetings. Finally, the PN monitors progress, and coordinates care and follow-up (step 8). Frequency of follow-up contacts will depend on the type of problems or complaints. When no follow-up actions are needed, the PN will check the older person’s health status annually (by phone or by means of a re-assessment with the [G]OLD-instrument).

[G]OLD geriatric assessment instrument

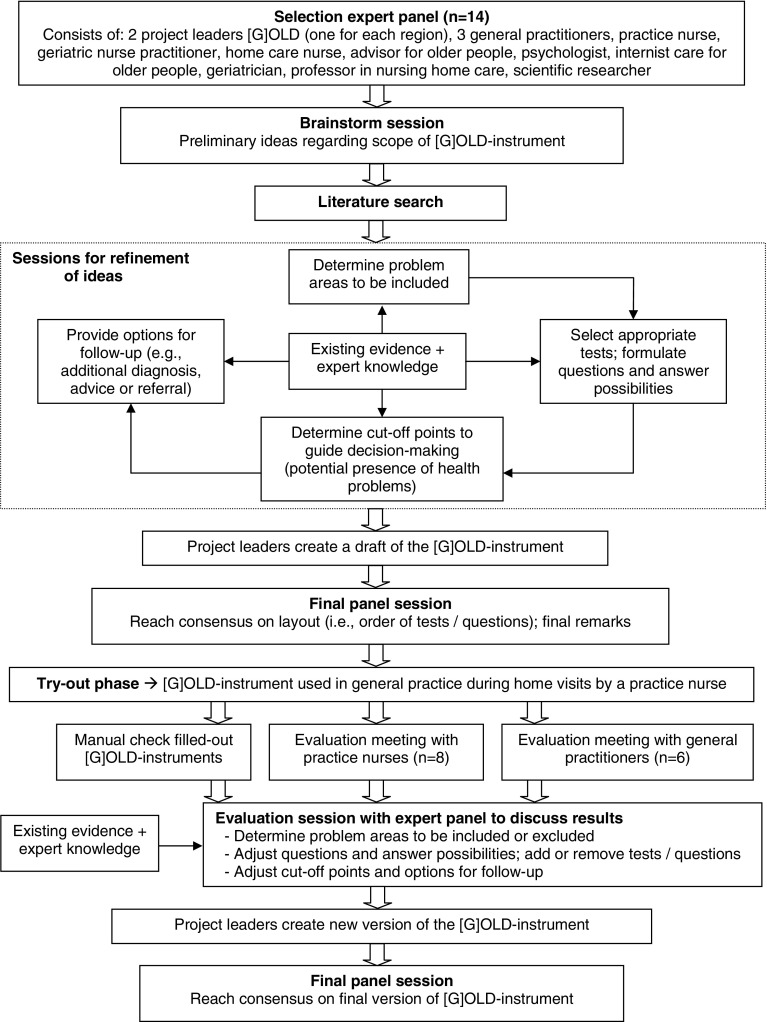

Although many CGA instruments exist, general practices required a flexible instrument encompassing all components of interest to a GP to obtain a complete overview of the older person’s health and well-being, while keeping the time investment to a minimum. Therefore, an expert panel (consisting of, among other, GPs) was brought together to develop a multidimensional geriatric assessment instrument: the [G]OLD-instrument (see Fig. 1). It assists the PN in uncovering early signs of decline among relatively healthy older people and in identifying needs among older people with existing problems where decline is unavoidable; both with the ultimate aim to maintain independent living among older people.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart procedure development multidimensional [G]OLD-instrument

The content of the [G]OLD-instrument is based on an existing Dutch instrument for geriatric assessment "TRAZAG" (Warnier 2008; Warnier et al. 2007) and on input from the expert panel. The assessment covers 23 areas, including older people’s functioning, physical and mental health, engagement in activities, and social well-being (for details, see Table 1). PNs can carry out an additional examination, or parts of it, if they require more insight into the presence or absence of a problem or risk situation.

Table 1.

Topics covered by the [G]OLD-instrument, their operationalization and source

| Topicsa | Operationalization | (Preliminary) cut-off point | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part one (basic assessment) | |||

| General health status | 1 item SF-20 (Kempen et al. 1995); 1 item SF-36 (Van der Zee and Sanderman 1993) | N/A | EB |

| 3 questions about complaints in past 2 months | N/A | PB | |

| Blood pressure | Blood pressure in mmHg | BPsyst > 140 mmHg BPdiast > 80 mmHg | Biomed |

| Medication use | Number of prescribed drugs; comparison actual use with prescription | ≥5 prescribed drugs | PB |

| IADL | IADL scale of Lawton and Brody (1969) | Dependent ≥ 1 IADL | EB/PB |

| ADL | Barthel index (Mahoney and Barthel 1965) | Dependent ≥ 1 ADL | EB/PB |

| Receiving informal care | 2 questions about informal care giver | N/A | PB |

| Vision | 5 questions (all self-report): | ||

| Problems in daily living because of impaired sight; decrease in vision capability lately; whether person wears glasses | Yes/No | PB | |

| Difficulty to read newspaper; difficulty to recognise face at 4 m distance (Van Sonsbeek 1988) | Yes/No | EB | |

| Hearing | Problems in daily living because of impaired hearing; environment acknowledges impaired hearing; whether person uses hearing aid (all self-report) | Yes/No | PB |

| Nutrition | Body Mass Index (BMI)—overweight (World Health Organization 2000) | BMI ≥ 25 | Biomed |

| Undesired weight loss in past 3–6 months Problems with eating and drinking |

Scored ‘yes’ on 1 item or both items | PB | |

| Physical activity | Physical activity on average 30 min per day, at least 5 days per week | Yes/No | PB |

| Smoking behavior | Whether person smokes and desire to quit smoking | Yes/No | PB |

| Alcohol use | Whether person drinks alcohol 2 items to determine excessive alcohol use; desire to reduce/quit alcohol use |

Yes/No <2 days abstinent and men ≥ 2–3 glasses/day, women ≥ 1–2 gl./day |

PB PB |

| Memory | Questions 1a-1e from Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975) | ≥1 wrong answer | EB |

| Anxiety | Part A of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith 1983) | Score ≥ 8 (range 0–21) | EB |

| Depression | 4 items Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Yesavage et al. 1982): dissatisfaction; emptiness; depressed mood; personal devaluation | Score ≥ 1 (range 0–4) | EB |

| Personality disorders | 3 items from Gerontologic Personality Disorders Scale (GPS) (Van Alphen et al. 2004): intention to end life; suffering from nervousness, tension; used sleeping pills in the past | Score ≥ 2 (range 0–3) | PBb |

| Fall incidents | Number of falls past 6 months Cause of falls, concerned about falling, and avoidance of activities due to fear of falling |

≥1 falls past 6 months N/A |

PB PB |

| Mobility | Get-up and go test (Mathias et al. 1986) | Score ≥ 3 (range 0–5) | EB |

| Participation in society | Satisfaction with daily activities/routines | Yes/No | PB |

| Loneliness | Whether person feels lonely (grade 1–10) 2 items about cause of loneliness; need of support to decrease loneliness |

Score ≥ 5 (range 1–10) N/A |

PB PB |

| Informal care giving | Provides informal care (and to whom) Burdened by informal care giving |

Yes/No Somewhat or very burdened |

PB PB |

| Finance | Financial problems past 12 months | Yes/No | PB |

| Quality of life | Self-reported quality of life (grade 1–10) | N/A | PB |

| Part two (additional examination) | |||

| Malnutrition | Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (Guigoz et al. 1994) | Score ≤ 11 (range 0–14) | EB |

| Memory | Complete Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975) Clock drawing test (Shulman et al. 1986) |

Score ≤ 24 (range 0–30) Score ≤ 4 (range 0–5) |

EB EB |

| Depression | Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15) (Sheikh and Yesavage 1986) | Score ≥ 5 (range 0–15) | EB |

| Personality disorders | Gerontologic Personality Disorders Scale (GPS) consisting of HAB-scale and BIO-scale (Van Alphen et al. 2004) | Score ≥ 5 on HAB-scale (range 0–7) or BIO-scale (range 0–9) | EBb |

| Participation in society | Whether person regularly performs outdoor activities (description activities and whether in need of support) | Yes/No | PB |

| Informal care giving | Amount and type of informal care giving and whether in need of support Self-perceived Pressure from Informal Care test (Dutch acronym: EDIZ) (Pot et al. 1995) |

N/A Scored ‘yes’ on item 8 and 9: heavily burdened |

PB EB |

N/A means not applicable, (I)ADL means (instrumental) activities of daily living, EB evidence-based; (derived from) an existing test validated for application in older subjects, PB practice-based; formulated by expert panel based on clinical expertise or derived from clinical guidelines, EB/PB evidence-based/practice-based; an existing validated test, but slightly adjusted wording or answer possibilities to fit the current context, biomed biomedical measurement

aIn the same order as they appear in the [G]OLD-instrument

bA validation study is being conducted to assess the validity and reliability of the complete version of the Gerontologic Personality Disorders Scale (GPS)

Objectives

The [G]OLD home visitation programme was developed with the ultimate aim to provide general practices with a protocol for organizing geriatric care that would be feasible and useful for application in daily practice. After the initial development, a pilot study was initiated to refine the [G]OLD home visitation programme for future use. The aims were to evaluate (a) the feasibility for general practices of home visits by a PN for the early detection of health and well-being problems, (b) the practical usefulness of the [G]OLD geriatric assessment instrument, and (c) whether the different steps of the [G]OLD home visitation programme were implemented as planned, by focussing on reinventions introduced by general practices. Reinvention may occur in the diffusion process when GPs and PNs apply the home visitation programme in their own practice and make changes to the original protocol [for further details, see Rogers (2003)]. Reinvention is often necessary for diffusing an innovation into a complex setting, although essential components of the innovation ensuring its effectiveness should not be discarded. It offers insight into how the [G]OLD home visitation programme can be put into daily practice on a large scale.

Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study was performed (April–June 2009), with a single group post-test design in the Dutch regions Maastricht-Heuvelland and Parkstad. According to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, no formal ethical approval was needed for this study, as subjects were not required to follow rules of behavior.

Selection of general practices

All general practices within the two regions (n = 143) were approached by postal mail to inform them about the study. They all had a PN working in the practice, but a prerequisite for participation was that the PN could devote time to conducting the home visits and arranging follow-up actions. A total of 21 general practices (14.7 %) agreed to participate (nine from Maastricht-Heuvelland, twelve from Parkstad) and were all included.

Selection of older people

General practices selected community-dwelling people aged 75 years or older from the GPs Information System. Those on a waiting list for admission to a nursing home or a home for older people, and the terminally ill were excluded. All general practices were requested to purposefully select older people who had not been in contact with their GP/PN for a consultation or visit for more than 6 months before the start of this study. These "apparently healthy" older people are often overlooked within general practice. However, they may fail to seek help or care for their unmet problems or complaints for various reasons (Walters et al. 2001). Therefore, this purposive sample might be particularly interesting for GPs as the results of the geriatric assessment might add to their current knowledge of the older person’s health and well-being. PNs were allowed to select older people and, if required, GPs could check the final list. Eligible older people were then randomly approached by the PN in a stepwise manner (until the end of the 3-month study phase) by means of an information leaflet by postal mail and subsequently a telephone call to schedule the home visit. General practices were informed that the time period for conducting the home visits for this study would be 3 months, but to decrease the risk of selection bias they could continue using the [G]OLD-instrument afterwards.

Training PNs

To equip PNs with the necessary knowledge and skills, they received 2 days of training. During the first day (prior to the pilot phase), information was provided concerning issues to be aware of in the aging process. Supervised by a nurse practitioner specialized in care for older adults, PNs practiced applying the [G]OLD-instrument among nursing home residents. The second day (during the pilot phase) consisted of discussing PNs’ practical experiences thus far and offering in-depth information on mental and psychological problems among older people, as well as impairments in hearing and sight. Additionally, a session focussed on working in multidisciplinary teams and included meeting other professional caregivers or institutions offering care and/or well-being facilities for older people.

Measures

A mixed model design (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004) is applied. Equal priority is given to both quantitative and qualitative data, they are gathered concurrently, and mixing takes place both at the stages of data collection and integration (after data analysis).

Registration forms PNs

Practice nurses registered the average time required for step 1 to step 4 of the [G]OLD-protocol on a structured registration form. For the remaining steps, the time investment strongly depended on the number and type of problems detected. Reasons for non-participation among older people were registered on the same form. Results of the geriatric assessment were registered by PNs on a structured assessment form. At the end of each home visit, the PN asked the older person open-ended questions about his/her opinion concerning: (a) the [G]OLD-questions; (b) the duration of the home visit; and (c) whether they preferred a home visit or a consultation in the GPs practice, and recorded this in writing on a separate form. These are preliminary indicators of the acceptability of the home visitation programme according to older people. The [G]OLD-instrument also included a separate care and treatment plan containing a list with all problem areas from the [G]OLD-instrument for which further details and follow-up actions could be written down. This form was checked manually to identify inconsistencies between the number of detected problems and the number of follow-up actions formulated by the PN.

Evaluation meetings

Within 1 month after the pilot phase, semi-structured evaluation meetings were organized with 6 GPs (15.0 %) and 8 PNs (36.4 %) separately to evaluate the implementation of the different steps of the home visitation programme, including the feasibility of the home visitation programme, and the practical usefulness of the [G]OLD-instrument. One member of the project team led the discussion using a topic list, while another member of the project group made notes of the discussion. The topic list consisted of all eight steps of the home visitation programme, as well as the training of PNs, and overall time investment. After both meetings, the project team members discussed the notes and reached consensus on the interpretation of the discussion.

Reinvention

According to Rebchook et al. (2006), three types of reinventions can be identified with different implications regarding fidelity (implementation as intended by the intervention developers): (1) a new component may be added to the protocol (no threat to fidelity); (2) minor changes to a component (fidelity more or less maintained or even improved); (3) major changes to or deletion of a component (fidelity threatened). For step 1 to step 6 of the [G]OLD-protocol, GPs and PNs were invited during the evaluation meetings to explain how they implemented each step. Any reinventions were subsequently labeled. Because the evaluation meetings took place shortly after the pilot phase to guarantee detailed information about experiences, no reinventions could be identified for step 7 and step 8 of the [G]OLD-protocol. A longer follow-up was not feasible within the study period.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical package SPSS for windows, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics (means, medians, and frequencies) were computed for quantitative variables. The number of planned follow-up actions following problems or complaints detected during the geriatric assessment were obtained by means of 2 × 2 contingency tables for each topic in the [G]OLD-instrument.

Content analysis was performed on the qualitative data from the registration forms, care and treatment plans, and the open-ended questions in the [G]OLD-instrument. The results of the evaluation meetings with GPs and PNs were summarized in a narrative report.

Results

Participants

One general practice dropped out at the start of the study due to illness of the PN. Two general practices did not return the forms before deadline. Thus, we included data from 18 general practices. Five of these were solo practices, five practices with two GPs, and the remaining were group practices (≥3 GPs) (total n = 40 GPs).

In total, 22 PNs invited 272 eligible older people for a home visit, of which 32 (11.8 %) refused to participate. Reasons for refusal were visit not necessary [not in need of (additional) help or care] (57.6 %), not interested in visit/medical examination (12.1 %), suspicion (e.g., afraid to be placed in a home for older people) (9.4 %), or other reasons (does not want results to be used for research; illness; partner passed away; could not be reached by phone; informal caregiver insulted; already had visit from a consultant for older people) (18.2 %). The average refusal rate per general practice was 12.5 % (SD 13.7; range 0–50 %).

Practice nurses visited 240 participants at home within a 3-month period for the [G]OLD geriatric assessment. The average number of home visits conducted per PN was 10.9 visits (SD 5.1; range 2–20). An overview of the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics is shown in Table 2. The mean age was 82.0 years; the majority was female, widowed, lived alone, and had completed primary education.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of older people enrolled in study (n = 240)

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 82.0 ± 4.2 |

| Range | 75–94 |

| Median | 82.0 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 164 (68.9 %) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single, widowed | 149 (62.1 %) |

| Married | 68 (28.3 %) |

| Single, divorced | 11 (4.6 %) |

| Single, never married | 9 (3.8 %) |

| Living together, unmarried | 3 (1.2 %) |

| Living status, n (%) | |

| Living alone | 158 (65.8 %) |

| Living with partner, husband/wife | 68 (28.3 %) |

| Living with others | 14 (5.9 %) |

| Level of education, n (%)a | |

| Primary education | 116 (49.1 %) |

| Lower to middle professional education | 108 (45.8 %) |

| Higher professional education | 12 (5.1 %) |

SD standard deviation

a n = 236

Feasibility [G]OLD home visitation programme

Time investment

The average total time investment for GPs and PNs combined was 118.1 min (for details, see Table 3). The home visit itself took on average 55.7 min and the duration of the home visit varied considerably between PNs.

Table 3.

Time required for the different elements of the [G]OLD preventive home visitation programme according to PNs (n = 19)

| Elements [G]OLD preventive home visitation programme | Average time investment GP and PN per older person (minutes) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | |

| Total time selection of eligible older people | 9.3 | 8.1 | 1.0–30.0 |

| Selection of eligible older people by GP | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.0–8.0 |

| Selection of eligible older people by PN | 7.1 | 8.5 | 0.0–30.0 |

| Send older people the invitation letter and information leaflet (PN) | 8.6 | 3.6 | 2.0–15.0 |

| Make an appointment with the older person by phone for the home visit (PN) | 7.7 | 4.5 | 2.0–15.0 |

| Selection of relevant information from the GPs Information System as preparation for the home visit (PN) | 6.1 | 3.9 | 0.5–15.0 |

| Travel back and forth for the home visit (PN) | 15.8 | 6.0 | 5.0–30.0 |

| Duration of the home visit (PN) | 55.7 | 14.5 | 34.0–92.5 |

| Post-discussion GP and PN | 8.1 | 5.39 | 0.8–21.5 |

| Total average time investment (GP + PN) | 118.1 | 27.0 | 78.4–161.9 |

M mean, SD standard deviation

Feasibility according to GPs and PNs

In general, GPs indicated that due to [G]OLD they experienced an improvement in quality of care for older people and an intensification of the contacts between PNs and older people.

General practitioners all agreed that the home visits are time consuming and that the costs are not fully reimbursed by health insurers. Some PNs struggled with planning the home visits, because it was difficult to judge on forehand how long a home visit would take. Nevertheless, all GPs and PNs preferred a home visit instead of a consultation in the GPs practice. It provides useful information about living conditions and the functioning of older people in their daily environment. GPs argued that it is important to investigate for which community-dwelling older people (aged ≥ 75 years) the geriatric assessment is most beneficial.

With respect to the group of non-responders, both GPs and PNs agreed that a home visit would have been particularly beneficial for these people. They might avoid seeking care or maintain a façade of “normalcy” to prevent others from noticing their problems. According to PNs, this group of older people is difficult to reach and they suggest that the GPs should try to contact refusers.

Finally, PNs wished more guidelines regarding follow-up actions that can be undertaken following detected problems or needs. GPs indicated that a service map with an overview of (local) health and well-being facilities would be useful and desirable.

Multidimensional geriatric assessment

Follow-up actions for detected health or well-being needs

According to the cut-off points in the basic assessment, follow-up actions were needed among 238 older people (99.2 %). Although required, for 10.9 % of these older people (n = 26) no care and treatment plan was formulated by the PN. Reasons for this are mainly unknown, although in general these older people seem to experience somewhat fewer problems (e.g., fewer complaints in the past 2 months, less dependent in IADL) compared to people for whom care and treatment plans were formulated. The number of follow-up actions formulated in the care and treatment plan per detected problem or risk situation is shown in Table 4. The most follow-up actions were following positive test results with respect to memory problems (58.7 %) (e.g., performing the MMSE test), decreased mobility (53.8 %) (e.g., referral to physiotherapist or occupational therapist), and depression (50.7 %) (e.g., performing the GDS-15 test), whereas for financial problems, excessive alcohol use, and dependency in one or more instrumental activities of daily living, no or only few follow-up actions were registered (0, 0, and 7.4 %, respectively). For only 69 out of all 824 unaddressed problems or needs, PNs wrote down the reason for not undertaking follow-up actions. Mostly, older people already received treatment, care or help (43.5 %) for problems such as impaired hearing, impaired sight, and dependency in (instrumental) activities of daily living. Furthermore, some older people wished no action (33.3 %), such as in case of impaired hearing and smoking. In other cases, no improvement was possible (13.0 %; problems such as polypharmacy or impaired sight) or the GP applied a “watchful waiting” policy (10.1 %; problems such as depression or one fall incident in past 6 months).

Table 4.

Follow-up actions formulated in the care and treatment plan following positive test results in the basic assessment and additional examination using the [G]OLD-instrument

| (Early signs of) problemsa | Prevalence, n (%) | Follow-up actions, n (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| Basic assessment ([G]OLD-instrument part one) (n = 240) | ||

| Hypertension (n = 230) | 160 (69.6 %) | 54 (33.8 %) |

| Polypharmacy (n = 155)c | 67 (43.2 %) | 12 (17.9 %) |

| Dependent ≥ 1 IADL (n = 240) | 94 (39.2 %) | 7 (7.4 %) |

| Insufficient physical activity (n = 239) | 84 (35.1 %) | 12 (14.3 %) |

| Decreased mobility (n = 76)c | 26 (34.2 %) | 14 (53.8 %) |

| Problems daily living due to impaired hearing (n = 239) | 79 (33.1 %) | 36 (45.6 %) |

| Problems daily living due to impaired sight (n = 238) | 74 (31.1 %) | 26 (35.1 %) |

| Depression (n = 235) | 69 (29.4 %) | 35 (50.7 %) |

| Moderate to severe overweight (n = 223) | 61 (27.4 %) | 7 (11.5 %) |

| Falls in last 6 months (n = 239) | 65 (27.2 %) | 19 (29.2 %) |

| Dependent ≥ 1 ADL (n = 240) | 65 (27.1 %) | 5 (7.7 %) |

| Loneliness (n = 237) | 61 (25.7 %) | 10 (16.4 %) |

| Cognitive impairment (n = 223) | 46 (20.6 %) | 27 (58.7 %) |

| Excessive alcohol use (n = 100)c | 20 (20.0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Burdened by informal care giving (n = 36)c | 7 (19.4 %) | 1 (14.3 %) |

| Unsatisfied with daily routines (n = 235) | 41 (17.4 %) | 12 (29.3 %) |

| Smoking (n = 237) | 33 (13.9 %) | 11 (33.3 %) |

| Personality disorders (n = 237) | 29 (12.2 %) | 14 (48.3 %) |

| Problems living conditions or housing (n = 239) | 28 (11.7 %) | 7 (25.0 %) |

| Anxiety (n = 225) | 17 (7.6 %) | 7 (41.2 %) |

| Financial problems (n = 208) | 9 (4.3 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Malnutrition (n = 238) | 6 (2.5 %) | 1 (16.7 %) |

| Additional examination ([G]OLD-instrument part two) (n = 77) | ||

| Malnutrition (n = 4) | 3 (75.0 %) | 2 (66.7 %) |

| Cognitive impairment (n = 36) | 25 (69.4 %) | 15 (60.0 %) |

| Depression (n = 41) | 21 (51.2 %) | 13 (61.9 %) |

| Unsatisfied with daily routines (n = 17) | 5 (34.2 %) | 2 (40.0 %) |

| Burdened by informal care giving (n = 3) | 1 (33.3 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Personality disorders (n = 17) | 3 (17.6 %) | 1 (33.3 %) |

(I)ADL means (instrumental) activities of daily living

a N representing number of participants who underwent that specific test or set of questions

b N and % of total number of participants with the (potential) problem (column ‘Prevalence’)

c N representing number of participants from total sample who use medications, have difficulty walking around the house during the home visit, drink alcohol, and provide informal care, respectively

Practice nurses used part two of the [G]OLD-instrument for 32.1 % of the older people (n = 77) and it took on average 28.7 min to complete (SD 14.9; range 5.0–70.0, large variation due to differences in tests that were executed). Follow-up actions formulated per detected problem or need are presented in Table 4. Again, for some problems, no follow-up actions were formulated and the only reason mentioned in 8 out of 25 unaddressed problems was that the older person refused action. Note that the discrepancy in the number of older people who underwent certain tests during the additional examination and the number of older people who should have undergone these tests according to the prevalence numbers in the basic assessment. This implies that PNs did not always perform the additional examination or parts of it.

Practical usefulness according to GPs and PNs

In general, PNs and GPs judged the [G]OLD-instrument to be practically useful. One GP presented a case in which the [G]OLD-instrument helped to get a complete overview of an older person’s health status which would facilitate a quicker transition to a nursing facility when the situation becomes unbearable. The GPs agreed that the older people are a heterogeneous group and that a broad, structured geriatric assessment instrument is necessary. PNs discussed the more practical side of administrating the [G]OLD-instrument. All suggested improvements by GPs and PNs were grouped into the following categories (random order): (a) lay-out; (b) textual errors; (c) removal of tests or questions (e.g., Whispered Voice test); (d) adding new tests or questions (e.g., type of house); (e) substitution of tests or questions by other, more valid or more reliable, alternatives [e.g., ADL and IADL questions by GARS (Kempen et al. 1996)]; (f) changes in the order of questions. Since no changes were made during the pilot phase, we do not label these suggestions as ‘reinventions’.

Practice nurses indicated that they required additional instructions regarding the administration of tests in the [G]OLD-instrument and clearer cut-off points for (early signs of) problems. For example, they emphasized the need for additional training in assessing older people’s medication use. GPs also acknowledged the importance of good training and guidelines for PNs. For instance, the MMSE test for determining cognitive impairment can be very confronting for older people if not introduced well by the PN.

Reinvention

Both GPs and PNs present at the evaluation meetings considered all steps of the structured [G]OLD-protocol to be valuable. For example, GPs acknowledged the importance of formulating a care and treatment plan with clear follow-up actions since this is essential for ensuring an adequate follow-up.

One PN made a minor change in step 1, namely mentioning the date of the home visit already in the first letter sent to the older person instead of making the appointment after sending the letter. One PN indicated not having sent the letter and the information leaflet to the older people (not implemented). This step was purposefully omitted from the protocol by the PN and substituted by directly calling the older person for making an appointment. Although the other PNs sent the letter with the information leaflet, they questioned whether older people actually read the leaflet. In addition to the protocol, all PNs also registered the results of the geriatric assessment in the GPs information system. They consider this essential for the follow-up of older people over time. Finally, two GPs mentioned having pre-discussed each planned visit with the PN (addition to protocol), while the other GPs explicitly mentioned not having pre-discussed the visits, because the PN should keep an open mind during the assessment.

Besides these reinventions, all other steps of the [G]OLD home visitation programme were implemented as planned according to PNs and GPs.

Acceptability of home visits according to older people

Of the participants, 95.3 % were satisfied about the duration of the visit, 0.9 % thought it was too short, and 3.8 % gave no opinion. The majority preferred a home visit (83.8 %) instead of a consultation in the GPs practice (1.3 %), 14.9 % felt indifferent. In general, participants judged the [G]OLD-questions asked to be “fine” (85.8 %), meaning that they were acceptable, while 4.3 % had no opinion and 5.7 % gave other comments. Only 3.4 % found them hard to answer, 0.4 % thought they were unpleasant, and 0.4 % said they were too personal.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the testing an intervention before its large-scale implementation provides valuable information for understanding how the intervention functions in the intended context. The Medical Research Council has argued that this often-neglected phase is essential in developing and evaluating complex interventions aimed at improving health, as a failure to consider the practical issues of implementation properly will lead to weaker interventions (Craig et al. 2008).

Compared to other recent studies in the Netherlands in which the effect of the preventive home visits was absent (Bouman et al. 2008; Van Hout et al. 2010), the [G]OLD home visitation programme is fully embedded within general practices. It comprises elements of the Guided Care model that has shown to be feasible and acceptable for patients and caregivers (Boyd et al. 2007). In contrast to interventions with a resource-based approach that aim to achieve and maintain overall well-being by stimulating self-management abilities (Steverink et al. 2005), the current problem-oriented approach fits more closely to the available knowledge and expertise in general practices. We found that the [G]OLD home visitation programme is indeed feasible for GPs and PNs, and also acceptable for older people. Although GPs considered the home visitation programme to be time consuming (average time investment per patient was almost 2 h), they emphasized the improved quality of care for their older patients. However, feasibility cannot be guaranteed over an extended period, as insufficient reimbursement by health insurers of the costs of this type of care for older people may eventually start to outweigh the benefits.

The [G]OLD-instrument was judged to be useful by both GPs and PNs. They gave valuable comments (such as clearer cut-off points) which will lead to improvement of the [G]OLD-instrument (see final steps in Fig. 1). Many health or well-being problems were detected for which follow-up actions were formulated in the care and treatment plan. This suggests, as concluded by previous research in other countries (Lucchetti and Granero 2011; Piccoliori et al. 2008), that a geriatric assessment in general practice might be worthwhile in terms of identifying previously unknown problems. Furthermore, the fact that many (early signs of) problems were detected among older people who had not visited the GP/PN for more than 6 months suggests that older people may not seek help or underreport symptoms, problems or needs. Potential reasons for this are that older people attribute them as natural features of aging, or symptoms that might indicate psychiatric disorders (e.g., low mood, forgetfulness) may not be considered to represent disease that requires a medical opinion (Morgan et al. 1997). Due to the aim of our study, we did not intend to obtain a representative sample of all community-dwelling older people who rarely consult their GP and we did not collect data among older people who often consulted the GP. Therefore, the prevalence numbers should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, it is deemed unlikely that general practices selected a more frail subpopulation of older people for the home visits, as they were informed prior to the study that they could continue using the [G]OLD-instrument afterwards. It might be argued that the cut-off points in the [G]OLD-instrument should be raised since for several detected needs follow-up actions were lacking. However, the expert panel judged the cut-off points to be appropriate. If there are early signs of problems, but follow-up actions are not desired or necessary yet according to the older person or GP, the GP can keep this information in mind for future reference.

Besides the suggested changes to the [G]OLD-instrument, this study also provided insight into necessary adjustments to improve the home visitation programme in general and issues to be aware of during its large-scale implementation. For example, responders might be healthier than non-responders, which indicates the importance of examining differences between the two groups in future research. Moreover, we noticed that PNs sometimes skipped certain tests or questions in the assessment for unknown reasons. In addition, PNs often did not clearly register problems and/or complaints detected during the home visit in the care and treatment plan or they did not (yet) specify appropriate follow-up actions. Possible explanations are that PNs, as indicated during the evaluation meetings, need clearer cut-off points and more guidelines for follow-up actions, they might register follow-up actions elsewhere (e.g., the GPs Information System), or no follow-up actions were needed. Even when follow-up actions were formulated, they often lacked detail (e.g., “monitor progress”). Without appropriate follow-up actions after the detection of health and well-being needs, the effectiveness of the home visitation programme may be compromised. It is likely that the 2-day training has been too short and may not have addressed these and other aspects (e.g., how to build a good relationship with the older person) adequately. Future training for PNs should concentrate on these aspects and in particular the issue of inaccurate/inadequate reporting by PNs.

Our focus on reinventions additionally resulted in allowing PNs to mention the date of the home visit already in the invitation letter send to the older person. Further, despite critical comments on the information leaflet for older people, the leaflet is essential in terms of informed consent and therefore should not be omitted. The majority of GPs disagreed with a pre-discussion before the home visit, and therefore we did not include this as an additional component to the [G]OLD-protocol. Finally, we aim to develop an ICT-based solution for general practices in which PNs can register the results of the geriatric assessments and plan follow-up actions in a uniform way.

Although this study refers to a specific intervention in a specific context, the results may contribute to an improved understanding of the issues to be aware of in the early phase of intervention implementation (e.g., reinventions introduced by programme implementers, inaccurate reporting). Furthermore, we illustrated the steps undertaken in designing and testing the intervention protocol as well as the geriatric assessment instrument. A limitation of the current study is that only few professionals attended the evaluation meetings and especially GPs were underrepresented. However, we did receive valuable information and critical comments which will help to improve both the home visitation programme and the [G]OLD-instrument, although it is likely that we missed certain opinions. Furthermore, this study provided insufficient insight into whether planned follow-up actions were indeed undertaken and to what extent other professionals were involved. A thorough process evaluation as part of our upcoming controlled trial will further address this specific issue.

In conclusion, the preliminary results of this study are promising and the [G]OLD preventive home visitation programme seems to be a valuable tool for general practices. Adjustments to the [G]OLD-instrument and the training for PNs are needed before further implementation. A large-scale controlled trial will be conducted to evaluate the influence of the home visitation programme on older people’s health-related quality of life and disability, and to evaluate into more detail the implementation of all elements of the [G]OLD-protocol within general practices, including the satisfaction of care providers and older people (process evaluation). This type of effectiveness studies is needed to facilitate the translation of research into practice and to increase the likelihood that evidence-based interventions will be adopted within the healthcare system (Gill 2005).

Acknowledgments

The development of project [G]OLD was supported by a grant from the Province of Limburg, the municipality of Maastricht, and the Foundation Beyaert Robuust Limburg, all in the Netherlands. Drs. M. Frederix and Drs. I. Wijnands (GP organization Maastricht-Heuvelland, "RHZ") organized expert panel meetings for the development of the [G]OLD-instrument and organized the evaluation meetings with GPs and PNs. The Public Health Service South-Limburg, the GP organizations in the regions Maastricht-Heuvelland ("RHZ") and Parkstad ("HOZL"), the municipality of Maastricht, the Foundation Beyaert Robuust Limburg, and the Dutch organization who looks after the interests of those who require care ("Huis voor de Zorg") collaborated in setting up the [G]OLD home visitation programme. We would like to thank all general practices in this study for their participation and useful input in improving the [G]OLD home visitation programme. Also, we are grateful to Lenneke van Eerd (student assistant, Maastricht University) for all the data entry work.

References

- Blokstra A, Baan CA, Boshuizen HC, Feenstra TL, Hoogenveen RT, Picavet HSJ, Smit HA, Wijga AH, Verschuren WMM. Vergrijzing en toekomstige ziektelast. Prognose chronische ziektenprevalentie 2005–2025 [Impact of the ageing population on burden of disease. Projections of chronic disease prevalence for 2005–2025] RIVM rapport 260401004. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R (2009) Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Research synthesis report no. 19. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boult C, Karm L, Groves C. Improving chronic care: the “Guided Care” model. Perm J. 2008;12:50–54. doi: 10.7812/tpp/07-014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman A, Van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Kempen GIJM, Knipschild P. Effects of a preventive home visiting program for older people with poor health status: a randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:397–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, Leff B, Brager R, Dunbar L, Wolff JL, Wegener S. Guided care for multimorbid older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:697–704. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Br Med J. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R, Metzelthin S, Van Rossum E, De Witte L, Van den Heuvel W. Interventions to prevent disability in frail community-dwelling older persons: an overview. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7:37–55. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutch College of General Practitioners (2007) NHG-Standpunt Toekomstvisie Huisartsenzorg. Huisartsgeneeskunde voor ouderen [Statement of the NHG, Future of General Practitioner Care. General practice medicine for older people]. NHG, Utrecht

- Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, Hewitt M, Robinson J, Blair M, Williams D, Brummell K. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J. 2001;323:719–725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM. Education, prevention, and the translation of research into practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:724–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Mini Nutritional Assessment: a practical assessment tool for grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Facts Res Gerontol. 1994;4(Suppl 2):15–60. [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands . Health care for the elderly with multimorbidity. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kempen GIJM, Brilman EI, Heyink JW, Ormel J. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de MOS Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-20): een handleiding [Measurement of general health status with the MOS Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-20): a guideline] Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kempen GIJM, Miedema I, Ormel J, Molenaar W. The assessment of disability with the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale. Conceptual framework and psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1996;33:1601–1610. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti G, Granero AL. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in general practice: results from the ‘Senta Pua’ project in Brazil. Eur J Gen Pract. 2011;17:20–27. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2010.538674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markle-Reid M, Browne G, Weir R, Gafni A, Roberts J, Henderson SR. The effectiveness and efficiency of home-based nursing health promotion for older people: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:531–569. doi: 10.1177/1077558706290941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias S, Navak US, Isaacs B. Balance in elderly patients: the “get-up and go” test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:387–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R, Pendleton N, Clague JE, Horan MA. Older people’s perceptions about symptoms. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(427–430):427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoliori G, Gerolimon E, Abholz H. Geriatric assessment in general practice using a screening instrument: is it worth the effort? Results of a South Tyrol Study. Age Ageing. 2008;37:647–652. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pot AM, Van Dijck R, Deeg DJ. Ervaren druk door informele zorg: constructie van een schaal [Perceived stress caused by informal caregiving: construction of a scale] Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 1995;26:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM, Huebner D, TRIP Research Team Translating research into practice: the dissemination and initial implementation of an evidence–based HIV prevention program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:119–136. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ. New insights from the Danish preventive home visit trial. Eur J Ageing. 2007;4:141–143. doi: 10.1007/s10433-007-0055-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh JA, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent findings and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment and intervention. New York: Howarth Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman K, Shedletsky R, Silver IL. The challenge of time: clock-drawing and cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1986;1:135–140. doi: 10.1002/gps.930010209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Slaets JPJ. How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Alphen SP, Engelen GJ, Kuin Y, Hoijtink H, Derksen JJ. Constructie van een schaal voor de signalering van persoonlijkheidsstoornissen bij ouderen [Construction of a scale to detect personality disorders in older people] Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;35:186–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee KI, Sanderman R. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de RAND-36: een handleiding [Measurement of general health status with the RAND-36: a guideline] Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haastregt JCM, Diederiks JPM, Van Rossum E, De Witte LP, Crebolder HFJM. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people living in the community: systematic review. Br Med J. 2000;320:754–758. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hout HPJ, Jansen APD, Van Marwijk HWJ, Nijpel G. Prevention of adverse health trajectories in a vulnerable elderly population through nurse home visits: randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN05358495] J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:734–742. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sonsbeek JLA. Methodological and substantial aspects of the OECD indicator of functional limitations. Maandbericht Gezondheid (CBS) 1988;88:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vass M, Avlund K, Siersma V, Hendriksen C. A feasible model for prevention of functional decline in older home-dwelling people—the GP role. A municipality-randomized intervention trial. Fam Pract. 2009;26:56–64. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K, Iliffe S, Orrell M. An exploration of help-seeking behaviour in older people with unmet needs. Fam Pract. 2001;18:277–282. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnier RMJ. TRAZAG. Transmuraal Zorg Assessment Geriatrie [TRAZAG. Transmural Care Assessment Geriatrics] Maastricht: Academic Hospital Maastricht/MUMC+; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warnier RMJ, Debie T, Beusmans G. Complexe zorg voor ouderen. Beoordelingsinstrument voor de praktijkverpleegkundige [Complex care for older people. Assessment instrument for the practice nurse] Tijdschr Prakt. 2007;2:50–53. doi: 10.1007/BF03074943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:1982–1983. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]