Abstract

Although there is an extensive body of literature on the use of residential satisfaction to measure the impact of housing conditions on well-being in later life, less is known about differences and similarities between sub-populations and national contexts. By means of a cross-European analysis (EU15), this study aims to examine how objective and subjective factors of living conditions shape the perceptions of older Europeans about the adequacy of their residential environment. Two patterns of housing quality are explored: (1) international heterogeneity of the EU15 countries, and (2) intra-national heterogeneity, where we distinguish between households at risk of poverty and those not at risk in the elderly population of these countries. Data were drawn from the 2007 wave of the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions survey, providing a sample of more than 58,000 individuals aged 65 years and older. The housing characteristics surveyed were reduced using tetrachoric correlations in a principal component analysis. The resulting predictors, as well as control variables (including gender, age, health status and tenure), are assessed using multiple linear regression analysis to explore their association with a high or low level of residential satisfaction. Despite a generally positive assessment by older Europeans of their living space, major geographic and household income differences existed in the factors that explained residential satisfaction. Identifying factors associated with residential satisfaction in different household income groups and national contexts may facilitate the development of EU policies that attempt to make ‘ageing in place’ a viable and suitable option for older Europeans.

Keywords: Ageing, Residential satisfaction, Living conditions, Poverty, Tetrachoric principal component analysis, Europe

Introduction

In the 1980s, Hunt and Frankenberge (1981) posed the question of the home as a castle or a cage for older people, as a metaphor of the influence the residential environment has on well-being in old age. Given the multidimensional nature of the living environment, “physically, socially and psychologically constructed in both real and ideal forms” (Sommerville 1997), in which the possible outcomes of the person–environment relationship are also manifold, the question remains to be answered. Previous research has consistently shown that the way in which living conditions affect the quality of life of older people is related not only to their practical use of the objective characteristics of their dwellings and the surrounding area—facilities, type of building, level of maintenance and structural adaptation, location, etc. (Braubach and Power 2011; Burton et al. 2011; Costa-Font 2013), but also to their perceptions of the environment’s potential to fulfil their cognitive, aspirational and emotional needs (Evans et al. 2002; Kaspar et al 2012; Nygren et al. 2007; Oswald et al 2007; Wahl et al. 2009).

Awareness of the objective-subjective duality of the person–environment relationship has given way to a search for indicators to approach this issue with survey data. Residential satisfaction has been the most utilised proxy of perceived housing adequacy, as it offers simple evaluation measures that consider emotional feelings and responses towards the social–physical living environment (Canter and Rees 1982; Francescato 2002; Weidemann and Anderson 1985).

Despite the large number and variety of studies using this indicator and summarised in meta-analyses (Aragonés et al. 2002; Pinquart and Burmedi 2003), its utilisation in cross-country comparisons exploring housing satisfaction among older adults is almost nonexistent in the literature (Nygren et al. 2007; Iwarsson et al. 2004, 2007). At a time when the implementation of ‘ageing in place’1 policies was a way to reduce rising healthcare costs (UN 2002) and take advantage of technical innovations in healthcare, understanding the relevance of the home environment to the well-being of older adults in the European Union (EU) is particularly important. As to the living conditions that affect residential satisfaction, evidence up until now is largely confined to national- or regional-level studies (see e.g. Oswald et al. 2003 for two rural regions in Germany; Iwarsson and Wilson 2006 for Sweden; Day 2008 for Scotland; and Rioux and Werner 2011 for France).

Implementing cross-European initiatives by EU policy-making bodies in an effort to effectively address ‘ageing in place’ needs should take into account both national particularities and the individual factors common to many older adults such as living conditions (Richardson and Bartlett 2009; Sixsmith et al. 2014). However, very few projects since ENABLE-AGE (Iwarsson et al. 2007) have been designed specifically to collect cross-country information on the influence of the residential environment on the autonomy, participation and well-being of the older-old (75+ years) population. Conversely, some useful insights can be drawn from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey, even though information concerning housing-related problems of the older population is only a small part of the data being collected.

In the present study, we will opt to analyse how specific individual factors related to living conditions influence residential satisfaction in old age in order to see if there are shared or not among the EU15 countries2 using data from EU-SILC (Wave 2007). Given the known differences by income level in residential satisfaction (e.g. Brown 1995; Golant 2008) and expectation to age in place (e.g. Lehning et al. 2013) and the fact that poverty reduction is one of the European Commission’s priorities,3 we perform separate intra-national analyses according to poverty status. The study has three objectives: (1) to develop a general overview of the level of residential satisfaction among older Europeans; (2) to assess the weight of living conditions in explaining residential satisfaction; and (3) to ascertain the degree of heterogeneity within and between the EU15 countries in the association between living conditions and residential satisfaction.

Background and hypotheses

Conceptual frames to approach the adequacy of living conditions in old age

Research on the adequacy of residential environments for older people has been predominantly developed by the field of environmental gerontology and related disciplines, under the theoretical umbrella of person–environment (P–E) Fit models (Carp and Carp 1984; Kahana 1982; Lawton and Nahemow 1973). These models presume that the suitability of a living space in later life depends on mutual adaptation between individual needs and environmental pressures (Gitlin 2003; Wahl et al. 2004). However, results based on the application of P–E Fit models show that the suitability of a living space depends not only on practical adaptations (accessibility), but also on the resident’s subjective sense of usability, the perceptions about the extent to which material conditions fulfil personal needs (Aragonés et al. 2002; Christensen et al. 1992; Fänge and Iwarsson 1999; Oswald et al. 2005). Residential satisfaction has been a recurrent single-item indicator of housing adequacy in these studies, strongly influenced by multiple factors: the sociodemographic profile and health status of the individual (Pinquart and Burmedi 2003; Rojo-Pérez et al. 2001); the physical environment, including accessibility of services and amenities (Rioux and Werner 2011); and psychological and social factors such as inter-personal relationships (Prieto-Flores et al. 2011).

More recent conceptual frameworks go beyond the limits of objective housing attributes and the level of functional adaptation suggested by P–E Fit models. Wahl et al. (2012) elaborated an integrative framework that better incorporates the cognitive–affective factors of the P–E approach into the fit models by considering two simultaneous processes, experience-driven (belonging) and behaviour-driven (agency). The “belonging” processes explain subjective perceptions related to cognitive and emotional factors, such as attachment to place and identity. Agency processes are more related to aspirations, the proactive behaviour of making intentional changes in the P–E relationship by adapting, creating or sustaining the living space. Both processes evolve during the life-course as the individual grows older, introducing a longitudinal view that recognises the importance of cohort effects in the P–E interchange. The empirical application of this framework advocates for the construction of aggregated indexes, in which housing satisfaction is only one of the sub-indicators, together with the usability of the home—potential of the environment to fulfil individual needs, meaning of home—feelings, goals, emotions and habits in relation to home, and housing-related control beliefs—sense of independence or autonomy in old age that regulates the interchange with the residential environment (Nygren et al. 2007; Oswald et al. 2006; Oswald et al. 2007).

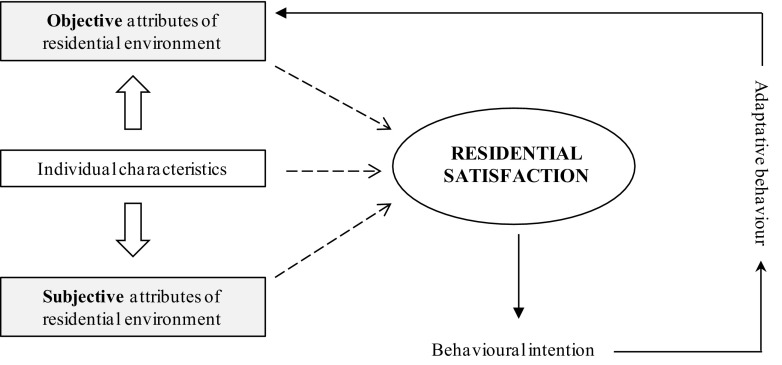

According to Amerigo and Aragonés (1997), the systematic interplay between objective and subjective housing elements contributes to form (or not) residential satisfaction (Fig. 1). Every residential environment presents certain material conditions (size, structure, services, facilities, etc.) that individuals and households evaluate in regard to their personal characteristics (age, gender, living arrangements, health status, etc.). These personal characteristics operate as a ‘filter’, transforming the physical elements into subjective attributes, in a process that contrasts actual and ideal residential conditions. Depending on the perceived suitability, the assessment of satisfaction and the behaviour towards this environment is positive or negative.

Fig. 1.

Amerigo and Aragonés’ systemic model of residential satisfaction. Source Based on Amerigo and Aragonés (1997, p. 48)

Although there are more comprehensive approaches to housing perceptions, our analysis on residential satisfaction is supported in ‘traditional’ P–E models given that it is impossible to approach the affective–cognitive dimension with our data source, even when applying the Amerigo–Aragonés scheme. Another limitation to be considered when using “residential satisfaction” as an indicator of housing perceptions is that there is no universally accepted taxonomy of living conditions’ indicators. This lack of homogeneous measures of physical housing quality multiplies the number of possible explanatory factors (Fänge and Iwarsson 1999; Smith et al. 2004). In fact, the development of standard indicators is recognised as one of the most important challenges for researchers (Adriaanse 2007). In addition, the two most common levels of environmental stratification—dwelling and neighbourhood—are clear in theory but confusing in practice. The ‘dwelling’ tends to be understood as the indoor housing space, but may also contain outdoor or non-housing zones such as the front entrance, backyard, gardens, garages, porches, balconies, terraces, etc. The ‘neighbourhood’ is even more difficult to define because different spatial criteria—area, community, district, etc.—have been used interchangeably (Aragonés et al. 2002; Iwarsson et al. 2007; Oswald et al. 2010).

Mapping the territory: trends in objective housing quality indicators and subjective perceptions of older Europeans

Comparative perspectives to describe the objective and subjective living conditions of older Europeans rarely have been implemented in surveys and empirical studies. Exceptions include the overviews of the housing standards of older Europeans published by Whitten and Kailis (1999) and Domanksi et al. (2006), which identified an uneven geographic distribution of housing quality in this population. Objective indicators—construction quality, dwelling size, services and facilities—improve on gradients from East to West and from the South to the North of Europe. Similarly, an analysis that included economic status showed that older low-income homeowners in Sweden, The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany enjoy relatively good housing conditions, compared with their counterparts in Mediterranean countries (Norris and Winston 2012). While housing standards for the older population have been upgraded throughout Europe, the gap between the groups with the best and the worst residential conditions has widened. In the EU15 countries, some of these differences are more evident between households with different income levels within the same country than between countries (Domanski et al. 2006).

In light of the literature on P–E interchange, the present study tested two hypotheses: (1) the living conditions in terms of accessibility and usability shape the level of residential satisfaction of older Europeans in each country of the EU15, a broader geographical context than earlier studies by Francescato (2002) and Oswald et al (2007); and (2) living conditions and residential satisfaction in Europe are not homogeneously distributed by geography or economic status (comparing households at risk of poverty to those not at risk). The second hypothesis is based on heterogeneity patterns of objective and subjective housing quality (Domanski et al. 2006; Whitten and Kailis 1999). The lack of cross-country conceptual constructs, as stated by the theorists of comparative research on ageing Tersch-Römer and von Kondratowitz (2006), in order to validate our study, compels us to base our study on the inter–intra-national heterogeneity distribution of housing quality as has been documented in the earlier cited studies. The comparison among both EU15 countries and being or not being at risk of poverty responds to the particularly clear manifestation of the aforementioned trends in these contexts.

Data and methods

The selected data source was the 2007 wave of the EU-SILC survey,4 which is being carried out annually since 2003 by the European Union, to provide comparable data to generate the socio-economic indicators used for assessing the well-being evolution of the European population. The 2007 wave was selected over more recent rounds because it included a special module on housing and neighbourhood characteristics. This set of 19 variables, mostly dichotomous (yes/no), covered both objective (i.e. physical elements of the dwelling) and subjective (based on opinions) information on living conditions.

The EU-SILC survey sample (206,313 individuals in 2007) is representative of the whole population residing in private dwellings at the moment of the survey in each country, having been elected by stratified random sampling procedures in most of the countries.5 For this study, a sub-sample of 58,178 individuals aged 65 years and older was extracted. The survey mitigated the possible underrepresentation of the most deprived collectives due to their higher non-response rates by establishing a minimum-large sample size to ensure a sufficient number of cases.6 The overall non-response rate in the 2007 wave was 24 % (ranging from 42 % in Denmark to 15 % in France and Italy). An additional 0.2 % (0.1–1.2 %, depending on the country) among the population aged 65 and older did not answer the question about their residential satisfaction.

In the present study, the definition of dwelling is limited to interior space, basically due to data limitations. As the EU-SILC survey did not specify boundaries, neighbourhood is defined as the dwelling’s immediate surrounding area; Marans and Rodgers (1975) refer to this as the ‘micro-neighbourhood’.7 Notwithstanding the existence of newer, more comprehensive frames to study housing perceptions (Wahl et al. 2012), our analysis of residential satisfaction was necessarily based on more ‘traditional’ P–E models because of the lack of information about the affective–cognitive dimension in the EU-SILC, the best available data source.

The empirical analysis was carried out in two phases. First, principal component analysis (PCA) was used to reduce the original 19 variables to four components, which are used as predictors of residential satisfaction. Second, the data were modelled using multiple linear regressions by country and household income group (15 × 2), assessing the association between the predictors obtained from the PCA and the reported residential satisfaction.

Tetrachoric PCA method to calculate predictors of residential satisfaction

The PCA method seeks to simplify the information contained in a set of observed variables , assuming that one or several latent variables underlie the data structure , (Hotelling 1933). One basic premise of the classical formulation of PCA is that the input variables must have a normal distribution or, at least, a reasonable approximation to normality (Abdi and Williams 2010; Dunteman 1989), making it suitable for continuous variables but less so for discrete data. The normality problems of using PCA for categorical data in 2 × 2 contingency tables can be overcome, however, by estimating the principal component eigenvalues utilising the tetrachoric correlation matrix rather than the usual Pearson’s correlation matrix. The former assumes that discrete data are truncated versions of continuous variables and, for that reason, normally distributed.

While tetrachoric correlations can be estimated in many ways, one proposed by Becker and Clogg (1988) appears to be the most accurate (Bonett and Price 2005). Normal percentiles and row and column category ‘scores’ are calculated to obtain a scaled log-odds ratio, which is then used to compute their tetrachoric approximations. Similar to Yule’s Q, the normed measure of association based on the odds ratio, this can be expressed as

where and is the population odds ratio.

Assessing the residential satisfaction of older Europeans

The second phase of this analysis explored the determinants of older Europeans’ residential satisfaction by carrying out a multiple linear regression analysis (MLRA) for each EU15 country, a common method in the assessment of residential satisfaction when the dependent variable is a single-item indicator (Rojo-Pérez et al. 2001). The predicted or expected values of the independent variables (X p)—in our case, the four predictors obtained with the PCA controlled by sociodemographic, health, and housing characteristics—are associated to the dependent variable ‘overall residential satisfaction’ , measured by a 4-point scale: (1) very dissatisfied, (2) somewhat dissatisfied, (3) satisfied and (4) very satisfied. This variable refers to dwelling value, space, neighbourhood, quality, whether the dwelling meets the household needs, and other aspects. The resulting function for the MLRA is then

The regression coefficients β represent the relative strength and the direction, positive or negative, that each predictor provokes in , ranging between −1 and 1. The intensity of the relationship between the predictors and the dependent variable is measured by the square multiple correlation indicator R 2, which estimates the variance explained by the model.

In addition to the PCA factors, several control variables were introduced into the model to control for them and thereby isolate the effect of living conditions: demographics (age and gender), health status (self-reported health status and limitations in daily activities), living arrangements (living alone or not), type of tenure (owner vs. tenant), financial burden (housing costs a financial burden or not) and the area where the dwelling is located (urban vs. rural).

Finally, the models were run on the sample’s households at risk of poverty and on those not at risk. Individual poverty status was obtained from the ‘risk of poverty threshold’ indicator (ARPT60) included in the EU-SILC dataset, defined as less than 60 % of the national median disposable income after social transfers (Eurostat 2009).

Results

Degree of residential satisfaction of older Europeans

The majority of older Europeans evaluate their housing situation positively, even in the case of those at risk of poverty. A mixture of material and psychological aspects explains this finding. On the one hand, there is a generalisation of high standards in the EU15 housing stock, above all in northern and western Europe (Domanski et al. 2006). On the other hand, psychological adaptation mechanisms, together with the emotional attachment that older people feel about their homes, can lead to a cognitive dissonance evaluating quite disadvantaged residential environments as positive (Carp 1976; Gilleard et al. 2007).

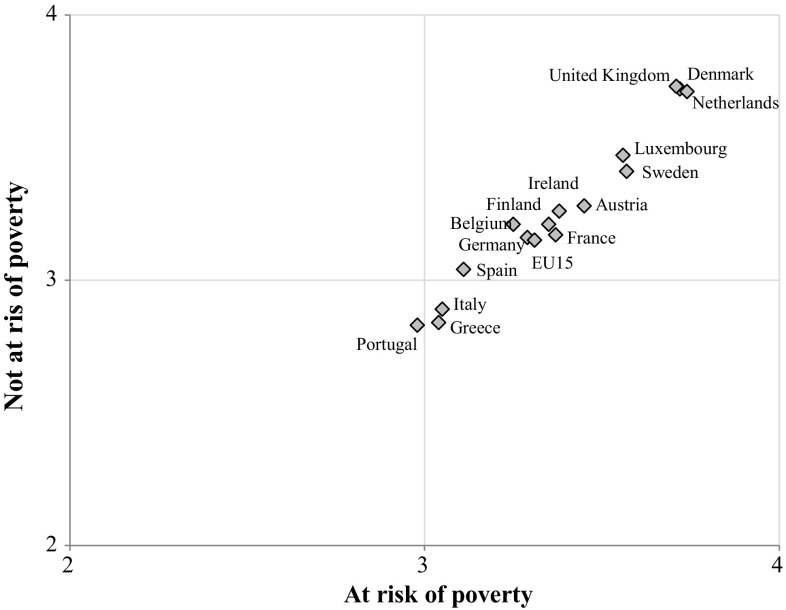

Despite the overall positive evaluation, all southern European countries declared the lowest levels of residential satisfaction, while there is no clear geographical pattern among the remaining EU15 countries (Fig. 2). In addition, satisfaction is systematically lower among the population at risk of poverty (with the exception of the three countries with the highest level of residential satisfaction, The Netherlands, Denmark and the UK). However, if we take into account the standard deviation, the observed differences are no longer statistically significant (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Residential satisfaction averaged scores by country comparing socio-economic groups (4-point scale). Scores: 1 very dissatisfied; 2 somewhat dissatisfied; 3 satisfied; and 4 very satisfied. Source EU-SILC (Wave 2007)

Table 1.

Overall residential satisfaction (4-point scale) of population aged 65 and over, by country and risk of poverty status

| Not at risk of poverty | At risk of poverty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | N | SD | Mean | N | SD | |

| Netherlands | 3.74 | 2716 | 0.498 | 3.71 | 173 | 0.537 |

| Denmark | 3.72 | 1679 | 0.547 | 3.72 | 278 | 0.531 |

| United Kingdom | 3.71 | 2826 | 0.513 | 3.73 | 1168 | 0.497 |

| Sweden | 3.57 | 2255 | 0.551 | 3.41 | 221 | 0.608 |

| Luxembourg | 3.56 | 928 | 0.586 | 3.47 | 81 | 0.572 |

| Austria | 3.45 | 2431 | 0.590 | 3.28 | 413 | 0.627 |

| Finland | 3.38 | 2814 | 0.661 | 3.26 | 478 | 0.673 |

| France | 3.37 | 3623 | 0.584 | 3.17 | 519 | 0.634 |

| Ireland | 3.35 | 2053 | 0.842 | 3.21 | 919 | 0.904 |

| Germany | 3.29 | 5799 | 0.952 | 3.16 | 970 | 0.930 |

| Belgium | 3.25 | 1823 | 0.809 | 3.21 | 535 | 0.687 |

| Spain | 3.11 | 4511 | 0.637 | 3.04 | 1863 | 0.674 |

| Italy | 3.05 | 8852 | 0.548 | 2.89 | 2324 | 0.618 |

| Greece | 3.04 | 2414 | 0.579 | 2.84 | 873 | 0.641 |

| Portugal | 2.98 | 1876 | 0.706 | 2.83 | 668 | 0.757 |

| EU15 | 3.31 | 46,600 | 0.703 | 3.15 | 11,483 | 0.742 |

Source EU-SILC (Wave 2007)

Living conditions as predictors of residential satisfaction in old age

Comparative findings were rather limited regarding perceived problems with the residential environment. EU-SILC data showed that housing maintenance and the incapacity to properly acclimatise the dwelling are the principal problems reported by older Europeans in both income strata and in most countries (Table 1). However, older people living in households at risk of poverty more frequently reported dwelling-related problems. A gap between high- and low-income groups in housing quality is detected in all countries, but is widest in southern Europe. Home maintenance problems such as a leaky roof, damp walls/floor/foundation, broken windows or rot in frames or floors were reported by about 20 % of older adults not at risk of poverty in Spain, Italy, Portugal or Greece, and by up to 30 % of their at-risk peers. In stark contrast, in Finland, these rates were 3 % of older-adult households not at risk of poverty vs. 7 % of at-risk households, and 3 versus 4 %, respectively, in Sweden.

An inability to maintain a comfortable temperature inside the dwelling is another frequent problem for older people, especially in Portugal and Greece. In the population at risk of poverty, an astonishing 71 % of older Portuguese and 34 % of older Greeks perceive their homes to be inadequately warm in winter and around 40 % in both countries declare that their homes are not sufficiently cool in summer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-reported problems of older population associated with the dwelling and neighbourhood by socio-economic group, EU15 countries, 2007 (%)

| AT | BE | DE | DK | ES | FI | FR | GR | IE | IT | LU | NL | PT | SE | UK | EU15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dwelling | ||||||||||||||||

| Shortage of space | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| At risk of poverty | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Too dark | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| At risk of poverty | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 4 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 24 | 5 | 9 | 10 |

| Housing maintenancea | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 6 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 19 | 3 | 10 | 23 | 14 | 20 | 10 | 11 | 20 | 3 | 8 | 12 |

| At risk of poverty | 13 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 29 | 4 | 15 | 36 | 16 | 30 | 16 | 10 | 30 | 7 | 10 | 21 |

| Not comfortably warm | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 1 | 13 | 2 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 1 | 7 | – | 1 | 47 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| At risk of poverty | 6 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 16 | 3 | 10 | 34 | 3 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 71 | 6 | 5 | 17 |

| Not cool during summer | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 14 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 22 | 15 | 23 | 30 | 7 | 28 | 10 | 12 | 37 | 8 | 8 | 19 |

| At risk of poverty | 20 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 26 | 11 | 21 | 40 | 7 | 31 | 9 | 10 | 41 | 10 | 6 | 22 |

| Neighbourhood | ||||||||||||||||

| Noise | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 20 | 20 | 23 | 15 | 21 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 10 | 25 | 19 | 25 | 26 | 10 | 16 | 20 |

| At risk of poverty | 18 | 16 | 27 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 19 | 11 | 11 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 19 | 9 | 13 | 17 |

| Pollution, grime, etc. | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 7 | 15 | 19 | 6 | 12 | 13 | 18 | 14 | 7 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 20 | 5 | 11 | 15 |

| At risk of poverty | 6 | 13 | 20 | 5 | 11 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 1 | 9 | 12 |

| Violence or vandalism | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at risk of poverty | 10 | 17 | 9 | 10 | 15 | 11 | 16 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 23 | 13 |

| At risk of poverty | 10 | 14 | 9 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 3 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 19 | 12 |

AT Austria, BE Belgium, DE Germany, DK Denmark, ES Spain, FI Finland, FR France, GR Greece, IE Ireland, IT Italy, LU Luxembourg, NL The Netherlands, PT Portugal, SE Sweden, UK United Kingdom

aProblems associated with housing maintenance include leaky roof, damp walls/floor/foundation, broken windows and rot in frames or floor

Self-reported problems related to the neighbourhood are important for older Europeans, although country and household income differences are more moderate than in the case of dwelling-related problems. Noise from the street or neighbours appears as the main problem (20 % on average for older people not at risk of poverty and 17 % at risk of poverty). Pollution or grime is identified more often by the high-income older population than the rest in 14 of the 15 countries (in Ireland the proportions are the same). In line with previous studies (Scharf et al. 2003), vandalism or violence in the neighbourhood is particularly relevant for older adults in the UK, with 23 % of older population not at risk of poverty and 19 % of those at risk of poverty declaring this as a problem. The lowest level is found in Greece (8 and 3 % respectively).

A tetrachoric principal component analysis (TPCA) with rotation, using STATA, was used to reduce the number of living condition variables to a more meaningful size. As the TPCA output shows in Table 3, four components were identified, explaining 60 % of the total variance.8

COMPONENT 1. Accessibility to community services This component explains 21.5 % of the total variance. It is positively correlated with accessibility to all community service variables; good access to a grocery store, banking services, postal services and primary health care services and, to a lesser degree, to easy access to public transport.

COMPONENT 2. Inadequate housing maintenance The second component (13.9 % of total variance) refers to poor housing maintenance. It is negatively associated with an adequate state of electrical and plumbing installations, and positively associated with some self-reported problems: dark or not enough light, lack of space and leaking roof, damp walls/floors/foundation, or rot in window frames or floor.

COMPONENT 3. Basic dwelling facilities This component (13.0 % of total variance) is positively associated with housing facilities, i.e. heating and cooling systems and indoor flushing toilet, shower or bath for the exclusive use of the household, as well as the subjective variable of the dwelling being adequately warm in winter.

COMPONENT 4. Environmental problems The last component (11.9 % of total variance) contains information regarding the neighbourhood. Three variables are positively associated with the perception of environmental deterioration: noise, pollution and vandalism.

Table 3.

Living conditions’ variables included in the PCA analysis and the TPCA loading coefficients

| Spatial frame | Variable | Type | Comp 1 | Comp 2 | Comp 3 | Comp 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dwelling | Shower/bathroom in the dwelling | D | −0.024 | −0.130 | 0.448 | 0.153 |

| Toilet in the dwelling | D | 0.022 | −0.127 | 0.440 | 0.155 | |

| Heating systema | Ca | −0.051 | 0.060 | 0.492 | −0.085 | |

| Air conditioning facilities | D | 0.017 | 0.271 | 0.360 | 0.028 | |

| Adequate electrical installations | D | 0.002 | −0.526 | −0.090 | 0.049 | |

| Adequate plumbing installations | D | −0.013 | −0.497 | 0.027 | 0.073 | |

| Shortage of space | D | 0.023 | 0.371 | −0.021 | 0.002 | |

| Leaking roof, damp walls/floors/foundation, or rot in window frames or floorb | D | −0.035 | 0.340 | −0.091 | 0.053 | |

| Dark/not enough light | D | −0.010 | 0.325 | −0.008 | 0.120 | |

| Adequately warm in winter | D | 0.034 | −0.032 | 0.387 | −0.134 | |

| Adequately cool in summer | D | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.254 | −0.263 | |

| Neighbour-hood | Access to groceryc | Cb | 0.470 | 0.025 | −0.019 | −0.013 |

| Access to banking servicesc | Cb | 0.463 | −0.008 | 0.015 | 0.007 | |

| Access to postal servicesc | Cb | 0.454 | 0.028 | 0.010 | −0.054 | |

| Access to public transportc | Cb | 0.392 | −0.015 | 0.008 | 0.078 | |

| Access to health care servicesc | Cb | 0.444 | −0.034 | −0.012 | −0.014 | |

| Noise from street or neighbourhoods | D | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.555 | |

| Pollution or grime | D | 0.013 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.559 | |

| Crime/Vandalism | D | 0.009 | 0.046 | 0.030 | 0.452 |

Source EU-SILC (Wave 2007) Signification level: p < 0.000

D dichotomous, C categorical

aInitial categories: 1. Yes, central heating or similar 2. Yes, other fixed heating 3. No, no fixed heating. These were subsequently dichotomised as Yes (formerly 1 and 2) and No (3)

bThis is a single variable. Respondents can suffer from one or more of these problems

cInitial categories: 1. With great difficulty 2. With some difficulty 3. Easily 4. Very easily. For the PCA regression analysis, these were dichotomised by aggregating the first two and last two categories

Explaining factors of residential satisfaction of older Europeans

Regression models are presented for each EU15 country and the two risks of poverty categories: Model 1 only contains the control variables, and Model 2 adds the residential satisfaction predictors obtained in the earlier PCA. We did not run Model 2 for Finland and Luxembourg due to an insufficient number of cases (especially households at risk of poverty) for a valid statistical analysis. Table 4 presents the R 2 indicator by country and household poverty status (at risk/not at risk of poverty). Results show that, as expected, the introduction of the PCA predictors improves the model fit, but that generally more variance is explained in the at-risk-of-poverty models, suggesting that for poorer individuals, living conditions are more important in explaining residential satisfaction. This appeared to be especially the case for Austria, Denmark, France, Portugal, Netherlands and Sweden; in the case of the UK, the reverse is actually true: living conditions were more important in determining residential satisfaction for those living in households not at risk of poverty. The analysis of the association between the explaining factors (control variables and predictors) and the degree of residential satisfaction is presented below.

Table 4.

Predictive potential of residential satisfaction regression models; R-squared values of adjusted variance

| Not at risk of poverty | At risk of poverty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| AT | 0.06*** | 0.13** | 0.15*** | 0.25*** |

| BE | 0.00** | 0.03** | 0.04** | 0.11*** |

| DE | 0.01** | 0.02** | 0.00 | 0.06*** |

| DK | 0.07 | 0.04* | 0.08 | 0.24*** |

| ES | 0.01*** | 0.05*** | 0.02** | 0.11** |

| FI | 0.05*** | 0.15** | – | – |

| FR | 0.10*** | 0.19*** | 0.10*** | 0.35*** |

| GR | 0.05*** | 0.30*** | 0.02* | 0.26*** |

| IE | 0.03*** | 0.07* | 0.05*** | 0.09*** |

| IT | 0.05*** | 0.13*** | 0.05*** | 0.15*** |

| LU | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.30** |

| NL | 0.05*** | 0.11** | 0.21** | 0.42*** |

| PT | 0.05*** | 0.12*** | 0.05*** | 0.28*** |

| SE | 0.10*** | 0.12** | 0.12* | 0.24* |

| UK | 0.05*** | 0.16*** | 0.05*** | 0.11*** |

Source EU-SILC (Wave 2007) Signification level: *** p < 0.000; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

Model 1: Control variables (age, sex, health status, limitations ADL, living arrangements, tenure, housing cost as financial burden)

Model 2: Control variables + living conditions’ predictors: accessibility to community services, inadequate housing maintenance, basic dwelling facilities, environmental problems

Not possible to carry out binary logistic regression due to lack of cases

AT Austria, BE Belgium, DE Germany, DK Denmark, ES Spain, FI Finland, FR France, GR Greece, IE Ireland, IT Italy, LU Luxembourg, NL The Netherlands, PT Portugal, SE Sweden, UK United Kingdom

Control variables

The MLRA outcomes by country for older people not at risk of poverty are displayed in Table 5, and for those at risk in Table 6. Regarding the control variables, type of tenure is the most often significant; older tenants are more inclined than owners to declare dissatisfaction with their residential situation in all countries. A possible explanation for this difference in residential satisfaction is what has been labelled as locus of control (Rotter 1966), i.e. satisfaction varies depending on whether the perceived responsibility to transform/improve the living space lies with the individual or with external agents. In the case of tenants, any modification of the dwelling needs the approval and/or action of the landlord who is responsible for the property maintenance (external locus of control) and does not always respond as desired to the tenant’s demands (James 2008).

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression of predictor variables on residential satisfaction Results for the older population not at risk of poverty, EU-SILC (Wave 2007)

| Country | N | Control variables | Living condition predictors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Health | ADL | Alone | Tenure | Burden | Area | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | ||

| Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | ||

| AT | 2,127 | 0.00** | 0.01 | 0.11*** | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.18*** | 0.06** | 0.05* | 0.00 | −0.52*** | 0.33*** | −0.19*** |

| BE | 1,624 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.09** | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.48*** | 0.26** | 0.02 |

| DE | 4,157 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.07** | 0.06* | 0.02 | 0.08** | −0.32*** | 0.10 | −0.15*** |

| DK | 897 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.11** | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.12** | −0.04 | 0.10** | −0.14 | 0.20* | −0.02 |

| ES | 1,486 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.10** | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.24*** | 0.22*** | −0.07 |

| FI | 389 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.21** | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.59 | 0.20** | 0.02 | 0.13** | −0.15 | 0.38** | −0.11 |

| FR | 878 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.17*** | −0.01** | 0.00* | −0.29 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.29*** | 0.30** | −0.10** |

| GR | 2,093 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06** | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.18** | 0.23*** | 0.08** | 0.04** | −0.44*** | 0.40*** | −0.09*** |

| IE | 1,898 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.10** | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.15*** | 0.12** | 0.03 | −0.43*** | 0.19 | −0.19*** |

| IT | 5,625 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10*** | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.19*** | 0.22** | 0.06*** | 0.05*** | −0.21*** | 0.37*** | −0.13*** |

| LU | 791 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.10* | 0.16*** | −0.48*** | 0.33* | −0.13** |

| NL | 968 | 0.01* | 0.05 | 0.09** | 0.06 | −0.06* | −0.10** | 0.03 | – | 0.05 | −0.47*** | 0.30** | −0.05 |

| PT | 503 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | −0.12 | −0.10 | −0.10 | 0.15** | −0.04 | 0.12** | −0.16* | 0.28** | −0.02 |

| SE | 979 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.16*** | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.11** | 0.20*** | 0.02 | 0.11** | −0.21** | 0.21** | −0.17** |

| UK | 1,497 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.15*** | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.06* | −0.52*** | 0.17* | −0.24 |

| EU15 | 24,944 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10*** | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.07*** | 0.20*** | 0.04*** | 0.06*** | −0.38*** | 0.31*** | −0.12*** |

Significance level: *** p < 0.000; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

Control variables; age (continuous), sex (ref. male), health status (ref. good health), limitations ADL (ref. yes), living alone (ref. yes), tenure (ref. owner), burden (ref. housing cost is a financial burden), urban area (ref. densely populated area; more than 500 hab./Km² and more than 50.000 hab.). Predictors: P1 (accessibility to services), P2 (inadequate housing maintenance), P3 (basic dwelling facilities), and P4 (environmental problems)

AT Austria, BE Belgium, DE Germany, DK Denmark, ES Spain, FI Finland, FR France, GR Greece, IE Ireland, IT Italy, LU Luxembourg, NL The Netherlands, PT Portugal, SE Sweden, UK United Kingdom

Table 6.

Multiple linear regression of predictor variables on residential satisfaction results for the older population at risk of poverty, EU-SILC (Wave 2007)

| Country | N | Control variables | Living condition predictors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Health | ADL | Alone | Tenure | Burden | Area | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | ||

| Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | ||

| AT | 355 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.28*** | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.25** | 0.12* | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.37** | 0.26** | −0.04 |

| BE | 472 | 0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.36** | 0.28** | −0.04 |

| DE | 640 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.16** | 0.17** | −0.42*** | 0.17 | −0.11 |

| DK | 164 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.27* | 0.00 | 0.29** | −0.93* | −0.09 | 0.01 |

| ES | 438 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.17 | −0.11 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.30** | 0.35*** | −0.11 |

| FI | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| FR | 94 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.26 | −0.15 | −0.04 | −0.49** | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.36* | −0.42** | 0.17 | −0.17 |

| GR | 734 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.14* | −0.06 | 0.08** | −0.39*** | 0.32*** | −0.03 |

| IE | 844 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.29*** | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.11 | 0.16** | 0.01 | −0.31*** | 0.32 | −0.21** |

| IT | 1,243 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.21*** | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.28*** | 0.41*** | −0.06* |

| LU | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NL | 58 | 0.02* | −0.11 | 0.25* | −0.20 | 0.24* | −0.35** | 0.03 | . | −0.14 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| PT | 149 | 0.00 | −0.19 | −0.27 | 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.33** | 0.43** | −0.22 | 0.21** | −0.27 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| SE | 101 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.22 | 0.13 | −0.11 | −0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.14 | −0.81** | 0.19 | −0.08 |

| UK | 590 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.17** | 0.09** | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.32*** | −0.28** | −0.12** |

| EU15 | 5,994 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.10*** | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.12*** | 0.24*** | 0.07** | 0.06*** | −0.38*** | 0.34*** | −0.10*** |

Signification level: *** p < 0.000; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

Control variables; age (continuous), sex (ref. male), health status (ref. good health), limitations ADL (ref. yes), living alone (ref. yes), tenure (ref. owner), burden (ref. housing cost is a financial burden), urban area (ref. densely populated area; more than 500 hab./Km² and more than 50.000 hab.). Predictors: P1 (accessibility to services), P2 (inadequate housing maintenance), P3 (basic dwelling facilities), and P4 (environmental problems)

AT Austria, BE Belgium, DE Germany, DK Denmark, ES Spain, FI Finland, FR France, GR Greece, IE Ireland, IT Italy, LU Luxembourg, NL The Netherlands, PT Portugal, SE Sweden, UK United Kingdom

The association between being a tenant and lower residential satisfaction shows a uniform pattern among those in risk of poverty and those who are not. Related to this, older people who considered housing costs—including mortgage interest payments, monthly rent, maintenance or repairs and the cost of utilities (water, electricity, etc.)—as not being a financial burden reported higher residential satisfaction in all of the EU15 countries. This association, however, is more often significant in households not at risk of poverty. The health status profile of the older person is also related to the level of residential satisfaction, although more significantly in the case of those living above the poverty threshold. Reports of bad or very bad health were related with a higher level of residential satisfaction in nine countries across the continent: Austria, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Sweden and the Netherlands. In general, gender, age and living arrangements show neither clear nor significant patterns between countries or risk of poverty status.9

Living conditions’ predictors

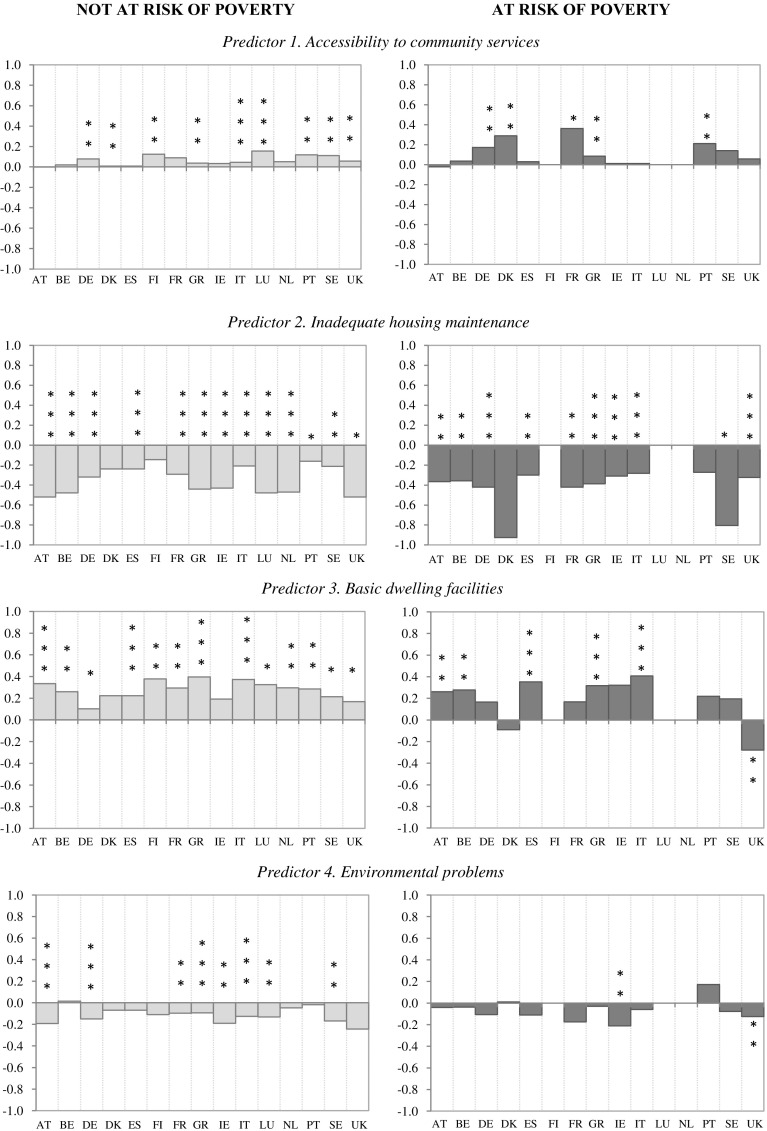

Looking at the PCA components, the association between the predictors’ coefficients and the assessment of satisfaction of the residential context in both risks of poverty groups and in the majority of EU15 countries shows a positive relationship with the predictors ‘access to community services’ and ‘basic dwelling facilities’, and a negative one with ‘inadequate housing maintenance’ and ‘environmental problems’ (Fig. 3).

Predictor 1 (Access to services): Living near services and places important for daily life is a strong factor explaining residential satisfaction (Haugen 2011), and this relationship was confirmed in our analysis. Regarding the older adults with higher incomes, accessibility to community services was significantly related to residential satisfaction in Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland and Sweden), western Europe (Germany, France, Luxembourg and the UK) and southern Europe (Greece, Italy, and Portugal). In the case of older adults at risk of poverty, having easy access to services was positively associated with residential satisfaction in southern Europe (Greece, Italy, and Portugal) and northern and western Europe (Denmark, France and Germany).

Predictor 2 (Inadequate housing maintenance): The negative influence of an inadequate housing maintenance on residential assessment of older adults was strong and very homogeneous in both the international and economic contexts, given that home reparations are real barriers that could affect the evaluation of living space (Oswald and Wahl 2004). With the exception of Denmark and Finland, inadequate housing maintenance negatively affected the evaluation of the living environment among the older adults over the poverty threshold in the EU15 countries. The spatial pattern of the results for the group at risk of poverty was slightly less clear, as Portugal and The Netherlands did not show a significant association, but its negative influence on residential satisfaction was nevertheless strong in the remaining countries.

Predictor 3 (Basic dwelling facilities): When the dwelling was equipped with basic facilities, older Europeans above the poverty threshold tended to be more satisfied about the place where they live. The exceptions were Germany and Ireland. Basic dwelling facilities only predicted residential satisfaction for older adults at risk of poverty in Italy, Greece, Spain, Belgium and Austria, which could be partially explained by the high percentage of dwellings lacking these basic facilities, especially among low-income populations (Fernández-Carro 2013; Whitten and Kailis 1999). This could be due to the poorer quality of housing in these countries (Table 1). Thus, residential satisfaction depended on basic dwelling facilities mainly in Mediterranean countries, independently of the income level. In the rest of countries, this relationship was low, not significant or absent. One possible explanation for the outlier status of the UK, where a dwelling having the basic facilities negatively affected the residential satisfaction of older adults living under the poverty threshold, is the effect of neighbourhood regeneration. Despite major investment in providing lower income UK households with new or improved housing in a higher quality setting (Van Gent 2010), structural problems such as unemployment and crime may not have improved, overriding the way respondents feel about their residence.

Predictor 4 (Environmental problems): Our study confirmed the negative relationship between environmental problems and residential satisfaction (Braubach 2007), although our results were not as conclusive as expected. For those older households not at risk of poverty, the existence of environmental problems also negatively conditioned their residential satisfaction, being statistically significant in some countries across Europe although without a clear regional pattern. In other words, homogeneity is less evident than for predictor 2. The effect of perceived environmental deficiencies in the lower income group is significant in just three countries: Italy, Ireland and the UK.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between residential satisfaction and living conditions in older ages. Results of multiple linear regression analysis. ***p < 0.01 **p < 0.05 *p < 0.1

Discussion

This study proposed a cross-European (EU15) overview of factors that enhance or constrain residential satisfaction, based on the assumption underlying the P–E models which states that the suitability of a given residential environment depends in great extent on the problems older people perceive, i.e. the subjective interpretation of the existing facilities (Amerigo and Aragonés, 1997; Aragonés et al. 2002; Kahana et al. 2003). Our research objective was threefold: to depict a general overview of the level of residential satisfaction of older Europeans, to assess the weight that living conditions have on explaining residential satisfaction; and to ascertain the existence of heterogeneity in the association between living conditions and residential satisfaction in Western Europe (between and within countries). Based on previous studies that identified an uneven spatial distribution of housing quality in Europe (Domanski et al. 2006; Whitten and Kailis 1999), we hypothesised that living conditions influence the evaluations that older adults have about their living environment and that these also vary according to the country of residence and risk of poverty status.

The study offers three major conclusions corresponding to the research objectives. First, the level of residential satisfaction of older Europeans follows a pattern consisting of a rather positive assessment of their housing conditions regardless of EU15 country of residence or household income level. Even older adults at risk of poverty, whose living standards are expected to be low, affirmed being satisfied or very satisfied with their residential situation. Even so, older people residing in southern Europe (Portugal, Greece, Italy and Spain) showed lower scores of residential satisfaction than those in the northern or western part of the continent, in accordance with the housing quality gradient outlined by Domanski et al. (2006).

The second conclusion confirms our first hypothesis; the characteristics of the living space (accessibility) and the evaluations that older people make about their dwelling (usability) both play an important role in explaining the degree of residential satisfaction in old age, just as Amerigo and Aragones (1997) suggested in their conceptual scheme. The introduction of the PCA predictors, which summarised features of the living environment, increased the explanatory potential of the statistical models in all countries, especially in the case of older Europeans under the poverty threshold. However, the degree with which living conditions explain residential satisfaction is not homogeneous for EU15 countries. Spatial heterogeneity, although not decisive, follows a regional pattern, along north–south and west–east lines, as reported from other studies (Ramos Lobato and Kaup 2014).

The third conclusion is that a cross-European pattern exists in the association between the four living conditions predictors considered and the level of residential satisfaction. In this case, the analysis does not completely support our second hypothesis, which was that residential satisfaction in Europe is not homogeneously distributed spatially nor economically. On the one hand, older adults who perceive to have good access to community services and reside in dwellings that possess the basic facilities tend to be more satisfied with their living space in most EU15 countries. On the other hand, poor housing maintenance and environmental problems negatively affect residential satisfaction for “everyone everywhere”. In addition, our analysis showed that characteristics such as inadequate housing maintenance or the dwelling’s lack of the more basic amenities are powerful predictors of residential satisfaction in later life in the majority of the EU15 countries. These results are in line with previous studies that highlight the weight that social and physical characteristics of the environment, particularly domestic space, has in the housing evaluations of older adults (Braubach and Power 2011; Costa-Font 2013; Rioux and Wender 2011), as well as studies showing cross-national similarities in the effect of characteristics of their residential context on well-being in old age (Scharf and de Jong Gierverld 2008).

In sum, while the association between living conditions and residential satisfaction is homogenous in Europe in terms of direction, i.e. the housing characteristics and perceptions increase or decrease the residential satisfaction of older Europeans in a quite similar way, the strength of this relationship is spatially and economically heterogeneous.

‘Ageing in place’ as an alternative to institutional care settings is a recurring theme in European politics but lacks concerted action, as few countries include older adults in policy decision making. As a result, Scandinavian countries have invested a great deal more in urban planning than the Mediterranean countries (Mestheneos 2011). From our results, it can be inferred that it is particularly in the south of Europe that improvements in dwelling and neighbourhood conditions would, besides enhancing residential satisfaction, also be a step towards achieving a more general life satisfaction and well-being in old age; however, this has obvious policy implications, “as housing stock is not normally planned to meet the requirements of older people” (Braubach and Power 2011). As most housing stock is not earmarked to specific age groups, housing (and general social well-being) policies should liaise with housing construction policies to cater to the changing conditions and (future) needs of occupants in different life stages. At least, public policy should facilitate the specific health- and safety-related reforms that permit older people to remain at home with a sufficient degree of independence and comfort. The implementation of this type of ‘ageing in place’ policies should not be addressed only to adapting the indoor space of older people’s homes, but also be combined with other measures that seek to create age-friendly cities, regenerating deprived areas, eliminating physical barriers or improving the accessibility to services and amenities used by older people.

Our research offers clues to modulate and coordinate policy tools at European and national levels, taking into account different countries and income groups (Smith 2013). For instance, measures aiming to maximise residential satisfaction through the improvement of rental housing quality or basic dwelling facilities would better be targeted to southern countries, especially to the lower end of the housing market. On the other hand, other measures can be more uniformly designed and implemented, for instance, against inadequate housing maintenance or the environmental problems surrounding a dwelling.

This study has some limitations that should be mentioned. Although the EU-SILC survey data permit a comparative study of residential satisfaction, it is not specifically designed to study housing perceptions among older adults; this impeded the possibility to contribute to developing an integrative framework, as proposed by Wahl et al. (2012). The survey does not contain variables regarding the affective–cognitive relationship of older adults to their environment, in particular, place attachment, meaning of home, social relationships and sense of independence. This limited the explanatory potential of the statistical models. The use of ‘residential satisfaction’ as an indicator of perceived housing adequacy may therefore have been rather basic if we take into account the recent analytical developments in this respect that consider aggregated indexes as more precise measurement tools (Nygren et al 2007; Oswald et al. 2006). Another shortcoming of the data source is that the information related to well-being is limited, as only self-reported health status and daily activity limitations are recorded, thus restricting the possibility to examine the outcomes of P–E relationships. In addition, future cross-national studies on the residential satisfaction should, besides individual factors, also consider the inclusion of macro-indicators that capture national differences in elderly welfare, housing and health care systems and economic conditions, and, if available, also macro-indicators at the neighbourhood level, especially related to poverty, unemployment and crime as this will help to better explain some of the divergent patterns found at national level by our study.

Finally, due to its relatively large sample size, EU-SILC remains a useful data source to study housing perceptions, not only for international comparison, but also for population sub-samples.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a revised version of Chapter 5 of Fernandez-Carro’s (2013) PhD thesis “Ageing in Place in Europe: a multidimensional approach to independent living in later life”. Financial support for this research came from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness: Dr Módenes and Dr. Fernández-Carro under the R + D + i project “Re-defining the population-housing linkage in a crisis context. A cross-European view” (CSO2010-17133), Dr. Módenes under the R + D + i project “Geographical mobility and housing: Spain in an international perspective” (CSO2013-45358-R) and Dr Spijker under the “Ramón y Cajal” programme (RYC-2013-14851).

Footnotes

Ageing in Place is a mainstream policy guideline of the EU in relation to the housing and care of older people. It seeks to preserve and extend as long as possible the conditions that allow older individuals to remain in their own home as an alternative to nursing residences (Sixsmith and Sixsmith 2008).

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, The Netherlands, and the UK.

European Union Survey on Income and Life Conditions. More info about: EU-SILC survey: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european_union_statistics_on_income_and_living_conditions.

Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Sweden employ simple random sampling methods. More info about the sampling procedures: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/d7e88330-3502-44fa-96ea-eab5579b4d1e/SILC065%20operation%202013%20VERSION%20MAY%202013.pdf.

For more detailed information about the Eurostat treatment to avoid non-response errors see: Verma et al (2010).

Marans and Rodgers (1975) established two environmental levels: ‘macro-neighbourhood’, the administrative division of urban environments, and ‘micro-neighbourhoods’, small groups of dwellings that conform a familiar space to their inhabitants.

The scale items were appropriate for PCA as the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) criteria of sampling adequacy, calculated before factor extraction, presented a value of 0.806.

Although age had two noticeable exceptions (Belgium and the Netherlands, where residential satisfaction increases with age among older elderly at risk of poverty), overall our results did not substantiate the positive association between age and residential satisfaction found in previous studies (Piquart and Burmedi 2003). However, it should be noted that we did not report on more precise age patterns in elderly residential satisfaction due to the limited sample size for the at risk of poverty sub-sample aged 80+ in half of the countries. It is nevertheless noteworthy to highlight the most important (although tentative) findings of the outcomes regarding the 80+ for all countries combined: (1) higher levels of residential satisfaction compared with population aged 65–79; and (2) indoor dwelling conditions (basic facilities and maintenance) are better predictors of residential satisfaction of the poor oldest-old than the characteristics of the outdoor space. Finally, it is worth to remember that results for ages 65–79 are close to those of the whole sample.

References

- Abdi H, Williams LJ. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. 2010;2:433–459. doi: 10.1002/wics.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adriaanse CCM. Measuring residential satisfaction: a residential environmental satisfaction scale (RESS) J Hous Built Environ. 2007;22:287–304. doi: 10.1007/s10901-007-9082-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amerigo M, Aragonés JI. A theoretical and methodological approach to the study of residential satisfaction. J Environ Psychol. 1997;17:47–57. doi: 10.1006/jevp.1996.0038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aragonés JI, Francescato G, Gärling T. Evaluating residential environments. In: Aragonés JI, Francescato G, Gärling T, editors. residential environments. Westport: Bergin & Garvin; 2002. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Becker MP, Clogg CC. A note on approximating correlations from odds ratios. Soc Methods Res. 1988;16:407–424. doi: 10.1177/0049124188016003003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonett DG, Price RM. Inferential methods for the tetrachoric correlation coefficient. J Educ Behav Stat. 2005;30:213–225. doi: 10.3102/10769986030002213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braubach M. Residential conditions and their impact on residential environment satisfaction and health: results of the WHO large analysis and review of European housing and health status (LARES) study. Int J Environ Pollut. 2007;30:384–403. doi: 10.1504/IJEP.2007.014817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braubach M, Power A. Housing conditions and risk: reporting on a European study of housing quality and risk of accidents for older people. J Hous Elder. 2011;25:288–305. doi: 10.1080/02763893.2011.595615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown V. The effects of poverty environments on elders’ subjective well-being: a conceptual model. Gerontologist. 1995;35(4):541–548. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton E, Mitchell L, Stride C. Good places for ageing in place: development of objective built environment measures for investigating links with older people’s wellbeing. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:839. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canter D, Rees K. A multivariate model of housing satisfaction. Int Rev Appl Psychol. 1982;31:185–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1982.tb00087.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carp FM. Housing and living environments of older people. In: Binstock RH, Shanas E, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. New York: VanNostrand Reinhold; 1976. pp. 244–271. [Google Scholar]

- Carp FM, Carp A. A complimentary/congruence model of well-being or mental health for the community elderly. In: Altman I, Lawton MP, Wohlwill J, editors. Human behaviour and the environment: the elderly and the physical environment. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 279–336. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL, Carp FM, Cranz GL, Wiley JA. Objective housing indicators of the subjective evaluations of elderly residents. J Environ Psychol. 1992;12:225–236. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80137-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Font J. Housing-related well-being in older people: the impact of environmental and financial influences. Urb Stud. 2013;50:657–673. doi: 10.1177/0042098012456247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Day R. Local environments and older people’s health: dimensions from a comparative qualitative study in Scotland. Health Place. 2008;14(2):299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanski H, Ostrowska A, Przybysz D, Romaniuk A, Krieger H. First European Quality of Life Survey: social dimensions of housing. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dunteman GH. Principal components analysis. London: Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (2009) Description of SILC user database variables:Cross-sectional and Longitudinal. Version 2007.1 from 01-03-09. Eurostat, Unit F-3, Luxembourg

- Evans G, Kantrowitz E, Elshelman P. Housing quality and psychological well-being among the elderly population. Gerontol B. 2002;57:381–383. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.P381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fänge A, Iwarsson S. Physical housing environment: development of a self-assessment instrument. Can J Occup Ther. 1999;66:250–260. doi: 10.1177/000841749906600507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Carro C (2013) Ageing in place in Europe: a multidimensional approach to independent living in later life. PhD Thesis. Autonomous University of Barcelona

- Francescato G. Residential satisfaction research: the case for and against. In: Aragonés JI, Francescato G, Gärling T, editors. Residential environments. Westport: Bergin & Garvey; 2002. pp. 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard C, Hyde M, Higgs P. The impact of age, place, aging in place, and attachment to place on the well-being of the over 50 s in England. Res Aging. 2007;29:590–604. doi: 10.1177/0164027507305730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L. Conducting research on home environments: lessons learned and new directions. Gerontologist. 2003;43:628–637. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. Commentary: irrational exuberance for the aging in place of vulnerable low-income older homeowners. J Aging Soc Pol. 2008;20(4):379–397. doi: 10.1080/08959420802131437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen K. The advantage of ‘Near’: which accessibilities matter to whom? Eur J Transp Infrast. 2011;11:368–388. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J Educ Psychol. 1933;24:417–441. doi: 10.1037/h0071325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P, Frankenberge R (1981) Home: castle or cage? In: An introduction to sociology. Open University, Milton Keynes

- Iwarsson S, Wilson G. Environmental barriers, functional limitations, and housing satisfaction among older people in Sweden: a longitudinal perspective on housing accessibility. Technol Disabil. 2006;18(2):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson S, Wahl H-W, Nygren C. Challenges for cross-national housing research with older persons: lessons from ENABLE-AGE project. Eur J Ageing. 2004;1:79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson S, Wahl H-W, Nygren C, Oswald F, Sixsmith A, Sixsmith J, Széman Z, Tomsone S. Importance of the home environment for healthy aging: conceptual and methodological background of the European ENABLE-AGE project. Gerontologist. 2007;47:78–84. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James RN., III Residential satisfaction of elderly tenants in apartment housing. Soc Indic Res. 2008;89:421–437. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9241-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E. A congruence model of person–environment interaction. In: Lawton MP, Windley PG, Byerts TO, editors. Ageing and the environment: theoretical approaches. New York: Springer; 1982. pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Lovegreen L, Kahana B, Kahana M. Person, environment, and person–environment fit as influences on residential satisfaction of elders. Environ Behav. 2003;35:434–453. doi: 10.1177/0013916503035003007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar R, Oswald F, Wahl H-W, Voss E, Wettstein M. Daily mood and out-of-home mobility in older adults: does cognitive impairment matter? J Appl Gerontol. 2012;11:1–22. doi: 10.1177/0733464812466290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow L. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfen C, Lawton MP, editors. Psychology of adult development and ageing. Washington DC: American Psychology Association; 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Lehning AJ, Smith RJ, Dunkle RE. Do age-friendly characteristics influence the expectation to age in place? A comparison of low-income and higher income Detroit elders. J Appl Gerontol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0733464813483210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marans RW, Rodgers SW. Toward an understanding of community satisfaction. In: Hawley A, Rock V, editors. Metropolitan America in contemporary perspective. New York: Halstead Press; 1975. pp. 299–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mestheneos E (2011) Ageing in place in the European Union. Global ageing issues and action 7.2:17–24. http://www.ifa-fiv.org/global-ageing-issues-action-volume-7-2/

- Norris M, Winston N. Home-ownership, housing regimes and income inequalities in Western Europe. Int J Soc Welf. 2012;21:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00811.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren C, Oswald F, Iwarsson S, Fänge A, Sixsmith J, Schilling O, Wahl H-W. Relationships between objective and perceived housing in very old age. Gerontologist. 2007;47:85–95. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl H-W. Housing and health in old age. Rev Environ Health. 2004;19:223–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl H-W, Mollenkopf H, Schilling O. Housing and life satisfaction of older adults in two rural regions in Germany. Res Aging. 2003;25(2):122–143. doi: 10.1177/0164027502250016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Hieber A, Wahl HW, Mollenkopf H. Ageing and person–environment fit in different urban neighbourhoods. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:88–97. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0026-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Schilling O, Wahl H-W, Fänge A, Sixsmith J. Homeward bound: introducing a four domain model of perceived housing in very old age. J Environ Psychol. 2006;26:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl H-W, Schilling O, Nygren C, Fänge A, Sixsmith A. Relationships between housing and healthy aging in very old age. Gerontologist. 2007;47:96–107. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Jopp D, Rott C, Wahl HW. Is aging in place a resource for or risk to life satisfaction? Gerontologist. 2010;51:238–250. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Burmedi D. Correlates of residential satisfaction in adulthood and old age: a meta-analysis. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;23:195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Flores ME, Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Forjaz MJ, Rojo-Perez F, Martinez-Martin P. Residential satisfaction, sense of belonging and loneliness among older adults living in the community and in care facilities. Health Place. 2011;17:1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Lobato I, Kaup S (2014) The Territorial Dimension of Poverty and Social Exclusion in Europe. http://www.espon.eu/export/sites/default/Documents/Projects/AppliedResearch/TIPSE/DFR/Annex_7_TypologyOfCountries_Working_Paper_9.pdf

- Richardson B, Bartlett H. The impact of ageing-in-place policies on structural change in residential aged care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux L, Werner C. Residential satisfaction among aging people living in place. J Environ Psychol. 2011;31:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo-Pérez F, Fernández-Mayoralas G, Pozo-Rivera E, Rojo-Abuin JM. Ageing in Place: predictors of the residential satisfaction of elderly. Soc Indic Res. 2001;54:173–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1010852607362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80:1–28. doi: 10.1037/h0092976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf T, de Jong Gierverld J. Loneliness in urban neigbourhoods: an Anglo-Dutch comparison. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5:103–115. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0080-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf T, Phillipson C, Smith A. (2003). Older people’s perceptions of the neighbourhood: evidence from socially deprived urban areas’, sociological research Online [http://www.socresonline.org.uk/8/4/scharf.html]. Accessed 18 Aug 2014

- Sixsmith A, Sixsmith J. Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008;32:219–235. doi: 10.1007/s12126-008-9019-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith J, Sixsmith A, Fänge AM, Naumann D, Kucsera C, Tomsone S, Haak M, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Woolrych R. Healthy ageing and home: the perspectives of very old people in five European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE. European Union foreign policy in a changing world. New York: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Sim J, Scharf T, Phillipson C. Determinants of quality of life amongst older people in deprived neighbourhoods. Ageing Soc. 2004;24:793–814. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04002569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville P. The social construction of home. J Archit Plan Res. 1997;14:227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Tersch-Römer C, von Kondratowitz H-J. Comparative ageing research: a flourishing field of theoretical cultivation. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3:155–167. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . Second world assembly of ageing. Political declaration and Madrid international plan of action on ageing. Madrid: United Nations; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gent WPC. Housing context and social transformation strategies in neighbourhood regeneration in Western European cities. Int J Hous Policy. 2010;10:63–87. doi: 10.1080/14616710903565712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma V, Betti G, Gagliardi F. An assessment of survey errors in EU-SILC methodologies and working papers. Luxembourg: Eurostat; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl HW, Scheidt R, Windley PG. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics. Aging in context: socio-physical environments. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H-W, Fänge A, Oswald F, Gitlin LN, Iwarsson S. The home environment and disability-related outcomes in aging individuals: what is the empirical evidence? Gerontologist. 2009;49:355–367. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl HW, Iwarsson S, Oswald F. Aging well and the environment: toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist. 2012;0:1–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidemann S, Anderson JR. A conceptual framework for residential satisfaction. In: Altman I, Werner C, editors. Home environments. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 153–182. [Google Scholar]

- Whitten P, Kailis E. Housing conditions of the elderly in the EU. Luxembourg: Eurostat; 1999. [Google Scholar]