Abstract

Purpose

Our analysis follows the implementation of Public Law 107–260, the Benign Brain Tumor Cancer Registries Act mandating collection of non-malignant brain tumors including meningiomas.

Methods

Meningiomas were selected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database for 2004–2011. Demographic and clinical characteristics, initial treatment patterns, and survival outcomes were evaluated.

Results

The average annual age-adjusted incidence rates were 7.62 per 100,000 population, 7.50 non-malignant (7.18 benign; 0.32 borderline malignancy), and 0.12 malignant. Annual rates increased for benign and borderline malignancy but decreased for malignant tumors. Female rates exceeded male rates and were even twice those for benign tumors. Black rates were significantly higher than other races for all three behavior types. Rates increased with advancing age. More than 80% tumors were located in cerebral meninges. Diagnostic confirmation through pathology occurred for about 50% benign, 90% borderline malignancy, and 80% malignant tumors. No initial treatment was reported for approximately 60% benign, 30% borderline malignancy, and 30% malignant meningiomas. Five-year relative survival estimates for benign, borderline malignancy, and malignant were 85.6%, 82.3%, and 66.0%, respectively. Predictors of poorer survival were advanced age, male, black race, no initial treatment, and malignant behavior whereas younger age, female, spinal meningioma, any initial treatment and benign or borderline malignancy were associated with better survival.

Conclusion

Our analysis demonstrates an increasing incidence of non-malignant meningiomas at the population level. Treatment patterns and survival outcomes is concerning for a substantial percentage not receiving surgical or radiation treatments for higher grade meningiomas.

Keywords: meningioma, benign tumor, malignant tumor, incidence, trend, survival, treatment, prognosis

Introduction

Population-based studies of meningiomas have been limited because of the benign nature of the histology and prior to diagnosis year 2004 hospital and state central cancer registries were not required to collect non-malignant cases. This changed with the passage of Public Law 107–260, the Benign Brain Tumor Cancer Registries Amendment Act.1 This law mandated collection of benign brain tumors that began with diagnosis year 2004. Our analysis follows the implementation of this law on this common, but little investigated cancer.

Meningiomas arise from archnoidal cells of leptomeninges and may occur throughout the coverings of the central nervous system. These archnoidal cells are derived from both mesenchyme and more anteriorly from the neural crest. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies meningiomas into 3 groups based on histologic grading.2 The estimated distribution of meningiomas by WHO classification scheme is 80–90% benign Grade I tumors, 5–15% atypical or borderline malignancy grade II tumors, and 1–3% malignant grade III tumors with recurrence rates following surgery of 7–20%, 30–40% and 50–80%, respectively.2,3

Meningiomas have the highest incidence rate among all primary brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors.4 Non-malignant meningioma is the most frequently reported histology, which accounts for more than one-third of all primary brain and CNS tumors.4 In autopsy series, asymptomatic (quiescent) meningiomas have been found in 2% of those autopsied 5, while in imaging-based screening studies of the general population, meningiomas are found in up to 1% of adults.6,7 The vast majority of symptomatic or incidentally identified meningiomas (~97%) are non-malignant tumors. The median age at diagnosis is 65 years and incidence increases with advancing age.4 Incidence is significantly higher in females as compared to males and although to a much lesser degree studies demonstrate higher incidence in blacks compared to whites for both malignant and non-malignant meningiomas.4

Treatment for most patients with meningioma includes one or more of the following: surgery, radiation therapy (RT), stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), or observation.8–12 For symptomatic or progressively enlarging meningiomas, complete surgical excision is recommended but in anatomically inaccessible locations, SRS can be employed. 12 For aggressive or higher grade meningiomas or partially resected benign meningiomas, adjuvant radiation therapy may be considered.13,14 Chemotherapy or other systemic therapies are usually reserved for inoperable and radiation-resistant disease.15 Clinical factors influencing prognosis include tumor grade, extent of surgery, and tumor volume.8,10–12,16,17

Methods

We evaluated population-based data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 18 registries of the National Cancer Institute. The SEER Program is an authoritative source of cancer incidence and survival in the United States (US) with registries covering approximately 28 percent of the US population. Meningiomas were defined as International Classification of Diseases for Oncology Version 3 (ICD-O-3) histology codes 9530–9534 and 9537–9539 in brain or central nervous system primary site ICD-O-3 codes C70.0–72.9, 75.1–75.3.18 Our analysis included both malignant (ICD-O-3 behavior code 3) and non-malignant meningiomas (ICD-O-3 behavior codes: 0-benign; 1-borderline malignancy).18

Demographic characteristics evaluated were age, gender, race (white; black; American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) or Asian Pacific Islander (API), and ethnicity (Hispanic; non-Hispanic). Hispanic ethnicity was defined using the NAACCR Hispanic Identification Algorithm, version 2, data element.19 Primary site and tumor behavior distributions were assessed as well as diagnostic methods, treatment patterns, and survival outcomes.

Frequencies, rates, trends, and survival statistics were calculated using the SEER*Stat 8.1.5 software. 20–22 Incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals are expressed per 100,000 and where appropriate age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population. Trends for incidence rates are presented as annual percentage change (APC). The APC is calculated by first fitting a regression line to the natural logarithms of the rates (r) using calendar year (x) as a regressor variable. The method of weighted least squares is used to calculate the regression equation. A positive APC corresponds to an increasing trend, a negative APC to a decreasing trend.

To further investigate sharp changes in incidence rates over time, the Joinpoint regression program version 4.1.1. was utilized.23,24 Joinpoints correspond to a point in time of a change in the trend where two different sloped lines come to a juncture, and the software fits the simplest joinpoint model that the trend data will allow. Using the Grid Search Method, the Permutation Test model (model: ln[y]=xb) assessed changes in incidence rates with a minimum number of 3 observations from a joinpoint to either end of the data. The APC with corresponding two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI), for each trend segment is calculated using weighted least squares regression.

Survival analyses were conducted on the cohort of meningioma cases in the SEER research data base for diagnosis years 2004–2010 who were actively followed and of known age. The study follow-up cutoff date was December 2011. Cases reported as death certificate only or autopsy, ages 100 years or older, and/or alive with no survival time were excluded. Standardized procedures were applied to select a single case for those cases with multiple primaries. Survival time was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last contact. Cases determined to be alive were censored at the date of last contact. SEER*Stat 8.1.5 statistical software was used to estimate observed and relative survival rates.20–22 This software can utilize life–table (actuarial) methods to compute survival estimates and accounts for current follow-up. In addition, Cox regression analyses were conducted using a dataset for meningiomas retrieved from the ASCII text files on the SEER website that is equivalent to the dataset in the SEER*Stat software program. 25 Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate risk of death and examine the effects of important covariables on survival using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. 26,27

Results

Table 1 and Appendix A1 Table (online) demonstrate population-based statistics on meningioma incidence and trends. A total of 51,065 new cases of meningioma occurred in the eighteen SEER geographic areas during 2004–2011. Of these cases, 50,290 or more than 98% were determined to be non-malignant (benign and borderline malignancy). Of non-malignant cases, over 95 percent were benign with the remaining classified as borderline malignancy. Only 775 malignant cases were diagnosed during the eight study years. The primary site location for more than 80% of all meningioma cases was cerebral meninges followed by meninges, NOS (~ 13%) then spinal meninges (~ 4%) and finally the posterior fossa, cranial nerve, pituitary, and suprasellar group (< 1%).

Table 1.

Meningioma Tumor Incidence and Trends by Selected Characteristics and Behavior, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2011

| All Meningiomas | Benign | Borderline Malignancy | Malignant | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Rate | CI Rate | Count | Rate | CI Rate | APC | CI APC | Count | Rate | CI Rate | APC | CI APC | Count | Rate | CI Rate | APC | CI APC | |

| Total | 51,065 | 7.62 | (7.55–7.68) | 48,136 | 7.18 | (7.12–7.25) | 2.41* | (1.02–3.81) | 2,154 | 0.32 | (0.31–0.33) | 2.48* | (0.52–4.47) | 775 | 0.12 | (0.11–0.12) | −7.27* | (−13.12, −1.02) |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 13,618 | 4.58 | (4.50–4.66) | 12,412 | 4.19 | (4.11–4.26) | 2.78* | (1.26–4.33) | 889 | 0.29 | (0.27–0.31) | 1.81 | (−0.23–3.90) | 317 | 0.10 | (0.09–0.12) | −5.03 | (−11.22–1.59) |

| Female | 37,447 | 10.22 | (10.11–10.32) | 35,724 | 9.74 | (9.64–9.85) | 2.32* | (1.00–3.67) | 1,265 | 0.35 | (0.33–0.37) | 2.99 | (−0.34–6.44) | 458 | 0.12 | (0.11–0.14) | −8.47* | (−14.62, −1.87) |

| Race | ||||||||||||||||||

| White | 40,453 | 7.51 | (7.43–7.58) | 38,261 | 7.10 | (7.03–7.17) | 2.33* | (0.95–3.72) | 1,627 | 0.30 | (0.29–0.32) | 2.99* | (0.78–5.25) | 565 | 0.11 | (0.10–0.11) | −5.13 | (−11.84–2.09) |

| Black | 5,932 | 9.17 | (8.93–9.41) | 5,531 | 8.58 | (8.35–8.82) | 3.04* | (0.95–5.17) | 275 | 0.40 | (0.35–0.45) | −0.86 | (−8.59-7.52) | 126 | 0.19 | (0.16–0.23) | −14.82* | (−23.22, −5.49) |

| AIAN | 291 | 4.21 | (3.70–4.77) | 278 | 4.07 | (3.56–4.62) | 5.62 | (−3.79–15.94) | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | |

| API | 3,778 | 6.38 | (6.18–6.59) | 3,476 | 5.89 | (5.69–6.09) | 0.57 | (−1.19-2.37) | 228 | 0.37 | (0.32–0.42) | 2.57 | (−1.24–6.53) | 74 | 0.12 | (0.10–0.16) | −13.98* | (−25.30, −0.95) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 5,279 | 6.45 | (6.26–6.64) | 4,955 | 6.10 | (5.91–6.28) | 1.10 | (−2.04–4.34) | 246 | 0.26 | (0.23–0.30) | −1.66 | (−5.47-2.30) | 78 | 0.09 | (0.07–0.12) | 0.01 | (−13.29–15.35) |

| Non-Hispanic | 45,786 | 7.81 | (7.73–7.88) | 43,181 | 7.36 | (7.29–7.43) | 2.59* | (1.31–3.89) | 1,908 | 0.33 | (0.31–0.35) | 3.21* | (0.72–5.76) | 697 | 0.12 | (0.11–0.13) | −7.77* | (−12.93, −2.30) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0–19 | 259 | 0.14 | (0.12–0.15) | 203 | 0.11 | (0.09–0.12) | −0.53 | (−4.52-3.63) | 43 | 0.02 | (0.02−0.03) | 13.24 | (−2.76–31.87) | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| 20–34 | 1,715 | 1.26 | (1.20–1.32) | 1,543 | 1.13 | (1.08–1.19) | 1.94 | (−0.81–4.77) | 137 | 0.10 | (0.08–0.12) | 6.59 | (−0.16–13.79) | 35 | 0.03 | (0.02–0.04) | −9.27 | (−26.96-12.70) |

| 35–44 | 4,223 | 4.36 | (4.23–4.50) | 3,923 | 4.05 | (3.93–4.18) | 1.88 | (−0.50–4.33) | 235 | 0.24 | (0.21–0.28) | 1.83 | (−4.80–8.92) | 65 | 0.07 | (0.05–0.09) | −2.84 | (−19.34-17.03) |

| 45–54 | 8,270 | 8.54 | (8.36–8.73) | 7,804 | 8.06 | (7.88–8.24) | 2.08* | (0.61–3.57) | 364 | 0.38 | (0.34–0.42) | 5.77* | (0.26–11.59) | 102 | 0.11 | (0.09–0.13) | −8.23 | (−19.21-4.24) |

| 55–64 | 10,491 | 14.63 | (14.35–14.91) | 9,836 | 13.72 | (13.45–13.99) | 0.83 | (−0.09–1.75) | 471 | 0.66 | (0.60–0.72) | 2.08 | (−2.90–7.32) | 184 | 0.26 | (0.22–0.30) | −7.17 | (−14.84-1.19) |

| 65–74 | 10,636 | 25.89 | (25.40–26.39) | 10,016 | 24.39 | (23.91–24.87) | 2.05* | (0.22–3.92) | 459 | 1.11 | (1.01–1.22) | 0.56 | (−5.68-7.22) | 161 | 0.39 | (0.34–0.46) | −5.09 | (−10.48-0.63) |

| 75+ | 15,471 | 41.05 | (40.40–41.70) | 14,811 | 39.27 | (38.63–39.91) | 3.83* | (1.89–5.81) | 445 | 1.21 | (1.10–1.33) | 1.17 | (−3.97–6.59) | 215 | 0.57 | (0.50–0.66) | −10.54* | (−17.84, −2.59) |

| Primary Site | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cerebral meninges | 42,146 | 6.29 | (6.23–6.35) | 39,692 | 5.92 | (5.86–5.98) | 1.77* | (0.22–3.34) | 1,864 | 0.28 | (0.26–0.29) | 2.12 | (−0.59-4.89) | 590 | 0.09 | (0.08–0.10) | −8.03* | (−13.47, −2.26) |

| Spinal meninges | 2,257 | 0.34 | (0.32–0.35) | 2,185 | 0.33 | (0.31–0.34) | 0.79 | (−2.62–4.31) | 44 | 0.01 | (0.01-0.01) | 1.30 | (−11.39–15.79) | 28 | 0.00 | (0.00–0.01) | ~ | ~ |

| Posterior fossa, othera | 98 | 0.02 | (0.01–0.02) | 90 | 0.01 | (0.01–0.02) | −15.20* | (−25.64,−3.30) | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Meninges,NOS | 6,564 | 0.98 | (0.96–1.00) | 6,169 | 0.92 | (0.90–0.94) | 7.58* | (5.64–9.55) | 245 | 0.04 | (0.03–0.04) | 5.33 | (−1.92–13.11) | 150 | 0.02 | (0.02–0.03) | −2.80 | (−13.46-9.18) |

cranial nerve, pituitary, suprasellar.

AIAN, American Indian/Alaska Native; API Asian or Pacific Islander; NOS, not otherwise specified; CI, confidence interval; APC, annual percentage change.

Rates are per 100,000 and age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population. CIs are 95% . APCs were calculated using weighted least squares method.

The APC is significantly different from zero (p<0.05).

Statistics suppressed due to insufficient count.

The average annual age adjusted incidence rate (AAIR) for all meningiomas was 7.62 per 100,000. AAIRs for non-malignant and malignant tumors were 7.50 and 0.12, respectively. Within the non-malignant category, the AAIRS were 7.18 and 0.32 for benign tumors and borderline malignancy tumors, respectively. Statistically significant increases in the annual incidence rates (AIR) over 2004–2011 were apparent for non-malignant, benign, and borderline malignancy tumors whereas malignant AIRs were observed to significantly decrease. Significant trends in AIRs also were observed for primary site at diagnosis. Increases were noted for cerebral meninges and meninges, NOS but a significant decrease was seen for diagnoses in the posterior fossa, cranial nerve, pituitary, and suprasellar site category. AIRs for meningiomas diagnosed in the spinal meninges were stable across 2004–2011.

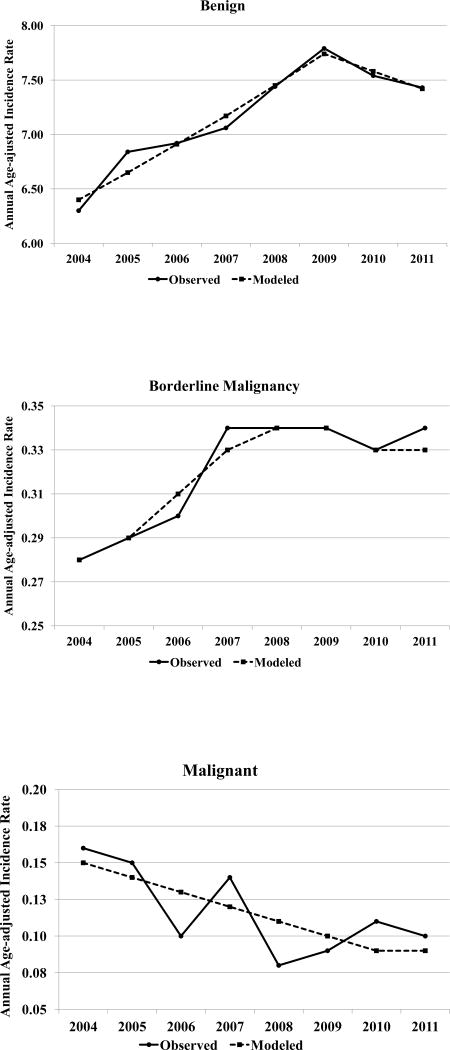

Joinpoint analyses for meningiomas by behavior demonstrated statistically significant trends in annual rates and three models with one joinpoint across years 2004–2011. These trends are graphically displayed in Figure 1. Statistically significant increases were observed over years 2004 to 2009 for non-malignant (APC=3.87, p<.05) and benign meningiomas (APC=3.86, p<.05) with a leveling off and no significant change in AIRs during years 2009–2011. The pattern for borderline malignancy was similar but the significant increase appeared from 2004 to 2008 (APC=5.50, p<.05) with no significant change over 2008–2011. No joinpoint was apparent for malignant meningiomas but a significant linear decline (APC= −7.27, p<0.05) was observed.

Figure 1.

Trends in Annual Age-adjusted Incidence Rates for Meningiomas by Behavior, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2011

Table 1 presents meningioma incidence by selected characteristics and behavior. For benign meningiomas, the AAIR for females was significantly greater than and more than twice the rate observed for males. The gender differences in AAIRs were statistically significant for benign and borderline malignancy tumors but not for malignant meningiomas. Among races, the highest AAIR for benign meningiomas was observed for blacks, followed by whites, then APIs and lowest for the AIAN group. The AAIRs for blacks were statistically significantly higher than those observed for other races among all tumor behavior types. Whites and blacks were observed to have statistically significantly higher benign AAIRs than AIANs as well as APIs. Likewise, APIs were observed to have benign AAIRs statistically significantly higher than AIANs. Non-Hispanic AAIRs for benign and borderline malignancy tumors were statistically significantly higher than those observed for Hispanics. Age-specific rates were observed to increase progressively with advancing age for all tumor types.

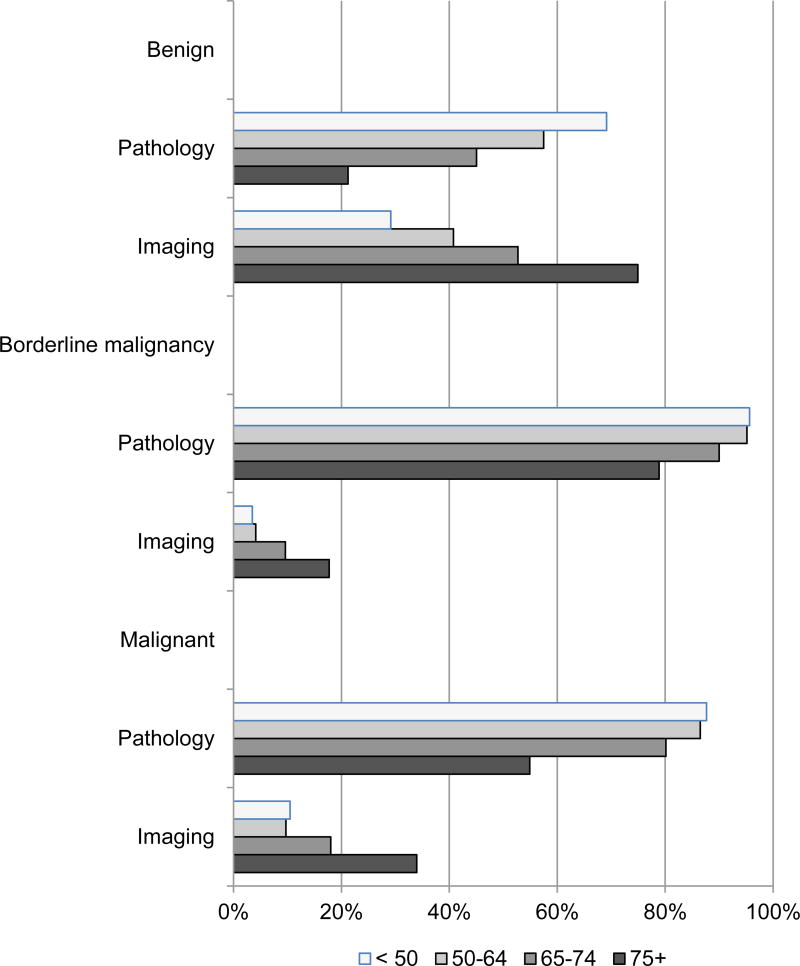

Diagnostic confirmation was made through pathology for about half of benign tumors and half by imaging but pathology was predominant among borderline malignant tumors (91%) and malignant tumors (77%). Diagnostic confirmation patterns for benign and borderline malignancy tumors were similar for males and females but males were somewhat more likely to have malignant tumors diagnosed through pathology than females (85% vs. 71%). An inverse relationship was evident between age and diagnostic confirmation through pathology. That is, as age increases diagnostic confirmation through pathology decreases. Conversely, a direct association between age and the proportion of cases diagnosed through imaging was observed. The relationships between age and diagnostic confirmation were consistent for benign, borderline malignancy, and malignant tumors as shown in Appendix A1 Figure (online).

Table 2 shows the distribution of initial treatment status for newly diagnosed meningiomas during 2004–2011. No initial surgery or radiation treatments were reported for greater than 60% benign tumors and about 30% borderline malignancy and 30% malignant tumors. Among the surgery/radiation treatment combinations, ‘surgery only’ was the most common for all meningioma behavior types. Cases diagnosed with borderline malignancy or malignant meningiomas more often received both surgery and radiation as a first course treatment than cases diagnosed with benign tumors. About twice as many malignant meningioma cases were reported to receive ‘radiation only’ when compared to benign or borderline malignancy cases. For all behaviors, higher proportions of females, blacks, and non-Hispanics received ‘no initial treatment’ compared to their respective demographic counterparts. The age group, 75 years and older, was substantially less likely to receive surgery and/or radiation as initial treatment than their younger age counterparts for the three behavior types. Ages 65–74 years were also more often noted to receive no initial treatment for benign tumor diagnoses than younger age groups. Benign meningioma cases with primary site locations in the spinal meninges or the posterior fossa, cranial nerve, pituitary suprasellar group more frequently received an initial surgical and/or radiation intervention than cerebral meninges or meninges, not otherwise specified. Almost 60% of spinal meninges cases were reported to receive surgery only initial treatment. Radiation only was the most frequent initial treatment for primary site diagnoses in the posterior fossa, cranial nerve, pituitary suprasellar site locations.

Table 2.

Distribution of Initial Treatment Status for Meningiomas by Selected Characteristics and Behavior, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2011

| Benign | Borderline Malignancy | Malignant | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Initial Treatment |

Surgery Only |

Radiation Only |

Surgery+ Radiation |

Othera | No Initial Treatment |

Surgery Only |

Radiation Only |

Surgery+ Radiation |

Othera | No Initial Treatment |

Surgery Only |

Radiation Only |

Surgery+ Radiation |

Othera | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Total | 61.8 | 28.2 | 6.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 29.3 | 49.3 | 5.7 | 13.5 | 2.2 | 31.0 | 33.4 | 11.6 | 19.9 | 4.1 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 59.0 | 30.3 | 6.2 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 25.3 | 52.0 | 5.0 | 15.2 | 2.6 | 25.2 | 39.1 | 8.8 | 24.6 | 2.2 |

| Female | 62.7 | 27.4 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 32.1 | 47.4 | 6.3 | 12.3 | 2.0 | 34.9 | 29.5 | 13.5 | 16.6 | 5.5 |

| Race | |||||||||||||||

| White | 62.0 | 28.2 | 6.2 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 28.4 | 50.7 | 5.8 | 13.1 | 2.0 | 30.4 | 32.0 | 12.0 | 21.4 | 4.1 |

| Black | 64.4 | 25.8 | 6.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 33.5 | 41.8 | 6.6 | 14.9 | 3.3 | 36.5 | 35.7 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 3.2 |

| AIAN | 60.1 | 29.5 | 5.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| API | 56.2 | 31.7 | 7.7 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 30.3 | 47.8 | 4.4 | 15.4 | 2.2 | 25.7 | 37.8 | 8.1 | 21.6 | 6.8 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 53.7 | 36.0 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 26.4 | 51.2 | 6.5 | 14.2 | 1.6 | 19.2 | 39.7 | 10.3 | 26.9 | 3.9 |

| Non-Hispanic | 62.7 | 27.3 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 29.7 | 49.1 | 5.6 | 13.4 | 2.3 | 32.3 | 32.7 | 11.8 | 19.1 | 4.2 |

| Age(years) | |||||||||||||||

| <50 | 43.6 | 43.9 | 7.3 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 27.1 | 49.7 | 6.8 | 14.8 | 1.6 | 19.8 | 40.1 | 14.8 | 24.1 | 1.2 |

| 50–64 | 53.1 | 35.2 | 7.5 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 26.3 | 48.7 | 6.8 | 16.5 | 1.6 | 22.8 | 38.0 | 10.1 | 25.3 | 3.8 |

| 65–74 | 62.6 | 27.5 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 28.1 | 51.0 | 5.2 | 13.9 | 1.7 | 27.3 | 35.4 | 16.2 | 18.6 | 2.5 |

| 7 5+ | 80.7 | 12.1 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 38.0 | 47.9 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 51.2 | 21.9 | 7.4 | 11.6 | 7.9 |

| Primary Site | |||||||||||||||

| Cerebra lMeninges | 62.7 | 27.2 | 6.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 29.1 | 49.6 | 5.5 | 13.8 | 2.0 | 29.3 | 32.2 | 12.7 | 22.0 | 3.7 |

| Spinal Meninges | 38.0 | 59.2 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 25.0 | 59.1 | 4.6 | 9.1 | 2.3 | 21.4 | 53.6 | 3.6 | 17.9 | 3.6 |

| Posterior Fossa, otherb | 44.4 | 23.3 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Meninges, NOS | 64.3 | 23.6 | 7.2 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 31.8 | 44.9 | 7.8 | 11.4 | 4.1 | 38.0 | 35.3 | 8.7 | 12.7 | 5.3 |

One thousand six cases could not be included in any of the four treatment groups due to inadequate information.

cranial nerve, pituitary, suprasellar.

AIAN, American Indian/Alaska Native; API, Asian or Pacific Islander; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Statistics suppressed due to insufficient count.

A total of 42,194 cases met the selection criteria for the survival analyses that resulted in findings shown in Appendix A2 Table (online). Kaplan-Meier 5-year relative survival estimates for benign, borderline malignancy, and malignant meningiomas were 85.6%, 82.3%, and 66.0%, respectively. For benign cases, 5-year relative survival was significantly more favorable for females than males; blacks than whites; Hispanics than non-Hispanics; spinal meningiomas than other primary site locations; and, any surgical or radiation treatment compared to no initial treatment. Relative survival estimates were similar for age groups until about age 55 years when survival became progressively less favorable with advancing age groups. The age-specific pattern was apparent for benign, borderline malignancy, and malignant behaviors.

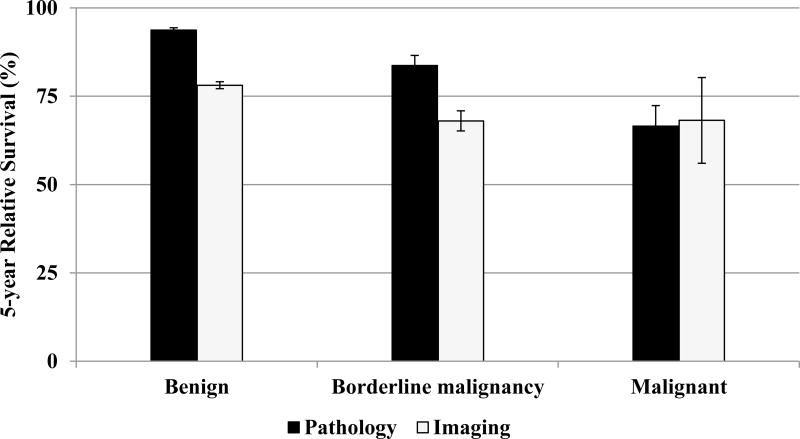

Survival differences were apparent based on method of diagnostic confirmation. For non-malignant (benign and borderline malignancy) tumors, cases diagnosed through pathology had significantly better survival than those diagnosed by imaging as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic Confirmation Method Distribution for Meningioma Cases by Behavior and Age Group, Surveillance, Epidemiology, End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2011

Results for proportional hazards regression analysis of the effect of selected factors on menigioma survival are shown in Table 3. Observed 5-year survival estimates are also presented for factors of interest. Advancing age, male gender, black race, no initial surgical or radiation intervention, and malignant behavior had adverse effects on meningioma survival. Conversely, younger age, female gender, spinal meningioma, any combination of initial surgical and radiation treatment, and benign or borderline malignancy behavior were associated with better survival outcomes.

Table 3.

Five-Year Relative Survival Rates (%) for Meningioma by Selected Characteristics and Behavior Surveillance, Epidemiology, End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2010

| Benign | Borderline Malignancy | Malignant | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | % | 95% CI | Count | % | 95% CI | Count | % | 95% CI | |

| Total | 39,846 | 85.6 | (85.0–86.2) | 1,794 | 82.3 | (79.3–84.8) | 554 | 66.0 | (60.6–70.9) |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 10,242 | 81.9 | (80.7–83.1) | 737 | 83.7 | (78.7–87.6) | 220 | 63.9 | (55.0–71.4) |

| Female | 29,604 | 86.9 | (86.2–87.5) | 1,057 | 81.3 | (77.4–84.6) | 334 | 67.4 | (60.3–73.6) |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 31,698 | 86.1 | (85.4–86.7) | 1,351 | 84.0 | (80.6–86.8) | 399 | 66.2 | (59.6–72.0) |

| Black | 4,562 | 81.6 | (79.8–83.4) | 236 | 74.8 | (64.5–82.5) | 91 | 67.6 | (53.9–78.0) |

| AIAN | 217 | 81.9 | (72.6 –88.2) | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| API | 2,910 | 85.0 | (83.0 –86.8) | 189 | 78.9 | (69.3 –85.7) | 58 | 57.5 | (40.9 –71.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 4,025 | 89.5 | (87.8 –91.0) | 205 | 84.9 | (76.3 –90.6) | 56 | 63.1 | (44.4 –77.0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 35,821 | 85.2 | (84.6 –85.8) | 1,589 | 81.9 | (78.7 –84.7) | 498 | 66.3 | (60.5 –71.5) |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 0–19 | 143 | 95.1 | (87.7 –98.1) | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| 20–34 | 1,250 | 97.5 | (96.0 –98.4) | 111 | 92.0 | (81.5 –96.6) | 23 | 87.0 | (56.1 –96.7) |

| 35–44 | 3,297 | 97.0 | (96.1 –97.7) | 193 | 89.0 | (81.5 –93.6) | 50 | 88.2 | (70.5 –95.5) |

| 45–54 | 6,554 | 94.9 | (94.1 –95.6) | 303 | 90.8 | (84.9 –94.5) | 78 | 84.7 | (73.2 –91.5) |

| 55–64 | 8,125 | 91.4 | (90.4 –92.2) | 392 | 88.4 | (82.6 –92.4) | 136 | 72.9 | (62.7 –80.8) |

| 65–74 | 8,290 | 85.7 | (84.5 –86.8) | 391 | 76.8 | (69.5 –82.5) | 115 | 50.5 | (38.1 –61.6) |

| 75+ | 12,187 | 70.6 | (68.9 –72.2) | 374 | 65.7 | (56.0 –73.8) | 143 | 45.6 | (32.8 –57.5) |

| Primary Site | |||||||||

| Cerebral meninges | 33,051 | 85.3 | (84.7–86.0) | 1,562 | 82.4 | (79.2–85.2) | 419 | 66.1 | (59.6–71.7) |

| Spinal meninges | 1,809 | 96.2 | (93.5–97.8) | 32 | 88.4 | (59.6–97.1) | 20 | 62.2 | (29.8–83.0) |

| Posterior fossa, othera | 76 | 86.4 | (75.8–92.6) | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Meninges, NOS | 4,910 | 83.5 | (81.7–85.1) | 199 | 78.9 | (68.5–86.2) | 108 | 67.7 | (56.5–76.7) |

| Treatment | |||||||||

| No Initial Treatment | 24,379 | 79.9 | (78.9–80.7) | 548 | 79.3 | (73.5–84.0) | 169 | 61.5 | (50.0–71.1) |

| Surgery only | 11,469 | 94.8 | (94.1–95.5) | 882 | 84.7 | (80.6–88.0) | 192 | 70.2 | (61.6–77.2) |

| Radiation only | 2,566 | 91.2 | (89.0–93.0) | 99 | 80.2 | (64.3–89.5) | 66 | 75.2 | (56.8–86.6) |

| Surgery + Radiation | 740 | 92.7 | (89.2–95.1) | 234 | 80.4 | (71.4–86.8) | 107 | 54.3 | (41.8–65.3) |

cranial nerve, pituitary, suprasellar; Kaplan-Meier method. Ederer II method used for cumulative expected.

Confidence interval (CI): Log)-Log() Transformation. The level is 95%. AIAN, American Indian/Alaska Native; API Asian or Pacific Islander; NOS, not otherwise specified;

Statistics suppressed due to insufficient count.

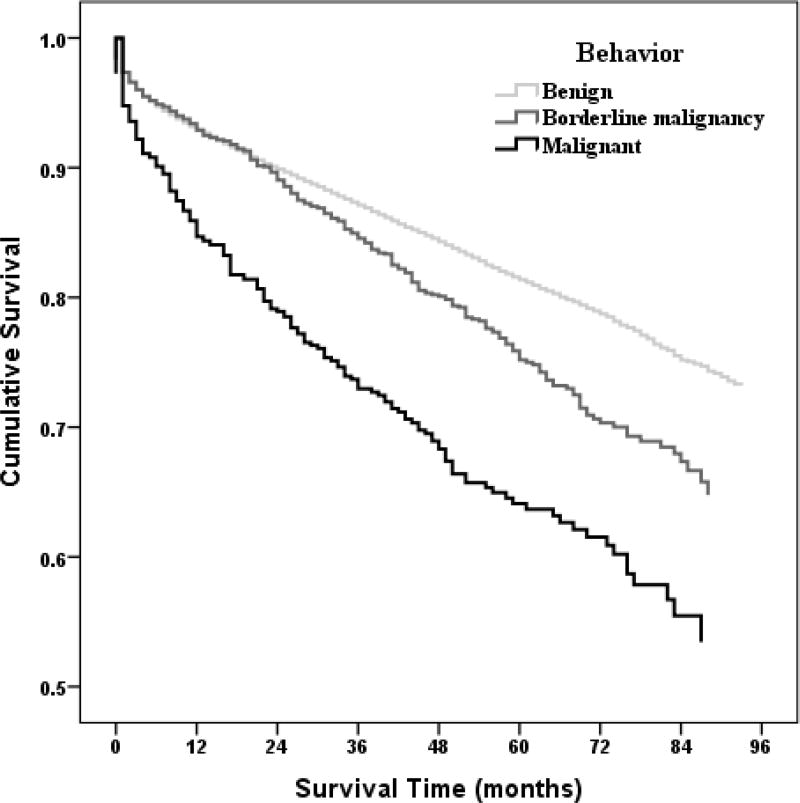

Cumulative survival patterns over seven years for meningioma cases by behavior adjusting for selected factors including age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, primary site at diagnosis, and initial treatment are shown in Appendix A2 Figure (online). The cumulative survival probabilities were highest for benign meningiomas followed by borderline malignancy and notably the worst for malignant meningiomas. Survival outcome differences between benign and borderline malignancy meningiomas became apparent at about 24 months when the respective survival curves separated with poorer survival becoming apparent for borderline malignancy compared with benign meningiomas.

Discussion

Our broad United States demographic analysis following Public Law 107–260 demonstrates an increasing incidence of meningiomas at the population level and provides new information on this most common CNS tumor. Increasing risk over the time period may be an artifact of increasingly accurate reporting associated with implementation of Public Law 107–260. The extent this contributed to the increased incidence is unknown. There is also a degree of ascertainment bias. This includes having improved diagnostic techniques as half of cases are registered based on imaging versus pathologic, which is required for most other cancers. There are also differences in state or hospital registries use of imaging-based registration of tumors. The state of Minnesota, for example, currently is the only state with a law forbidding registration of tumors based on imaging and as expected has the lowest incidence of brain and central nervous system tumors.28 Also unknown is the uniformity of registration for clinically, disease-based symptoms versus incidental imaging based finding (an incidentaloma).

Our trend analyses suggest that rates stabilize and demonstrate no significant change over 2009–2011. Reporting for diagnosis years 2004–2009 may have been influenced by factors previously discussed and that diagnosis years 2009–2011 likely reflect accurate incidence estimates for meningiomas with more complete registration of nonmalignant tumors. A recent study using data from 11 population-based state cancer registries that collected both malignant and non-malignant primary brain tumors diagnosed from 1997–2008 reported statistically significant age-adjusted rate increases for non-malignant tumors from 1997–2005 with no significant changes for rates during 2005–2008 suggesting that the latter time period may reflect the true incidence of non-malignant brain and CNS tumors in the United States.29 Our findings would suggest that the ‘true’ incidence time period may be somewhat later during 2009–2011 when we observed stabilization of rates.

As expected, the disease is higher in women and elderly, and the site location largely involves the cerebral meninges. Identifying the cause for the increase in incidence is a priority as the US population is aging with women living longer than men. Meningiomas will therefore be an increasingly common clinical concern. From our results, the elderly were also less likely to obtain a tissue-based diagnosis and in the future if this trend holds image-based bias will be magnified. Relative survival outcomes in these image-based diagnosed cases are poorer and reflecting that perhaps an increase in comorbid conditions preventing a pathologic diagnosis and/or a disparity in care.

Our findings reaffirm previous studies on meningioma, but with firm statistical power.30–34 The expected gender-based difference in incidence was observed. We also found a gender based difference in outcomes for benign meningiomas with men having a poorer relative survival than women. Black race was associated with higher incidence and poorer survival outcomes. For most other CNS tumors blacks have a lower incidence and no significant difference in survival. In addition, spinal meningiomas representing a fraction of cases, less than 5%, have improved outcomes with overall good survival compared with other primary sites.

Our study also provides an overview on the current state of clinical management of meningiomas and their expected outcomes. A substantial portion of cases of benign was not microscopically confirmed, while borderline malignant and malignant had significantly higher rates of pathologic confirmation. Also clinically relevant is the relatively high percentage of cases that were not receiving treatment with surgery or radiation especially for borderline malignant and malignant meningiomas. Although advanced age was associated with less treatment, even many younger patients did not receive local-regional therapy. This lack of therapy is higher than expected compared to large clinical series.8,9,35–37 The reason for this lack of local-regional therapy could be for many reasons including advanced age, poor overall health, views on the benign course of the disease, and differences in clinical care from an academic versus the general population.

We also point out that our survival analysis is based on relative survival versus disease-specific survival. As meningiomas are associated with an older age group having comorbid conditions, this may exaggerate the aggressiveness of this cancer. Obtaining cancer-specific survival also has challenges in population-based studies as it is known to have bias on misclassification on cause of death with difficulty attributing cancer-specific death versus cancer-consequent death.

The use of cancer registries is essential for obtaining generalizable epidemiologic information on tumors but there are limitations. This includes previously discussed regional and state reporting differences. We also recognize that registry information lacks centralized imaging review and uniform validation of case quality. Furthermore, our information on mode of therapy has limitations in SEER and we lack information on use of chemotherapy.

In summary our broad US demographic analysis following the implementation of Public Law 107–260 demonstrates an increasing incidence of meningiomas that has recently stabilized. Relative survival is similar to previous studies, however, initial local-regional therapy is lower than expected. The main demographic risk factors for meningioma, advanced age and in women, are rising in the general US population and the incidence will increase.

Figure 3.

Five-year Relative Survival Estimates for Meningiomas by Behavior and Method of Diagnostic Confirmation, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2010

Figure 4. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Model.

Non-parametric Estimates of Survival Function for Effects by Behavior on Meningioma (Adjusted for age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, primary site, and initial treatment.)

Table 4.

Effect of Selected Factors on Meningioma Survival, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program 18 Registries, 2004–2010

| Count | % Dead |

Observed 5-year Survival (%) (SE%) |

HRa (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0–34 | 1,566 | 3 | 96.3 (0.6) | 1.00 | <.001 |

| 35–44 | 3,538 | 4 | 95.5 (0.4) | 1.46 (1.05–2.01) | <.05 |

| 45–54 | 6,934 | 7 | 92.6 (0.4) | 2.32 (1.72–3.12) | <.001 |

| 55–64 | 8,652 | 12 | 86.7 (0.4) | 4.01 (3.00–5.35) | <.001 |

| 65–74 | 8,796 | 22 | 75.9 (0.5) | 7.70 (5.78–10.25) | <.001 |

| 75+ | 12,704 | 47 | 46.3 (0.6) | 18.98 (14.28–25.24) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 11,199 | 27 | 69.6 (0.5) | 1.00 | |

| Female | 30,991 | 21 | 76.1 (0.3) | 0.70 (0.67–0.74) | <.001 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 33,446 | 23 | 74.2 (0.3) | 1.00 | <.001 |

| Black | 4,888 | 25 | 71.0 (0.8) | 1.34 (1.26–1.42) | <.001 |

| AIAN | 226 | 16 | 78.6 (3.6) | 1.06 (0.76–1.47) | 0.73 |

| API | 3,156 | 19 | 78.1 (0.9) | 0.93 (0.86–1.02) | 0.11 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 37,905 | 23 | 73.7 (0.3) | 1.00 | |

| Hispanic | 4,285 | 16 | 80.7 (0.7) | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | 0.50 |

| Primary Site | |||||

| Cerebral meninges | 35,031 | 23 | 74.2 (0.3) | 1.00 | <.001 |

| Spinal meninges | 1,860 | 13 | 84.8 (1.0) | 0.65 (0.57–0.74) | <.001 |

| Posterior Fossa, otherb | 84 | 25 | 76.1 (5.1) | 1.17 (0.76–1.80) | 0.47 |

| Meninges, NOS | 5,215 | 24 | 72.0 (0.7) | 1.09 (1.02–1.15) | <.01 |

| Treatment | |||||

| No Initial Treatment | 25,093 | 28 | 66.4 (0.4) | 1.00 | <.001 |

| Surgery only | 12,542 | 13 | 86.7 (0.3) | 0.59 (0.56–0.63) | <.001 |

| Radiation only | 2,731 | 16 | 81.5 (0.9) | 0.68 (0.61–0.75) | <.001 |

| Surgery +Radiation | 1,081 | 16 | 82.0 (1.4) | 0.80 (0.68–0.93) | <.01 |

| Behavior | |||||

| Benign | 39,843 | 22 | 74.6 (0.3) | 1.00 | <.001 |

| Borderline malignancy | 1,793 | 22 | 74.1 (1.3) | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) | <.001 |

| Malignant | 554 | 38 | 58.8 (2.4) | 2.14 (1.86–2.45) | <.001 |

Hazard ratio adjusted for age group, sex, race, ethnicity, primary site, treatment and behavior;

cranial nerve, pituitary, suprasellar;

AIAN, Amereican Indian/Alaska Native, API, Asian or Pacific Islander; NOS, not otherwise specified; SE, standard error; CI, confidence intervals.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: TAD, JPT, EVD, and JLV were supported by the National Cancer Institute (R03CA156561).

References

- 1.Benign Brain Tumor Cancer Registries Amendment Act . PUBLIC LAW 107–260—OCT. 29, 2002. In: Record C, editor. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY—S. Vol. 148. 2002. p. 2558. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry A, Stafford SL, Scheithauer BW, et al. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1455–65. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199712000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(Suppl 2):ii1–ii56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakasu S, Hirano A, Shimura T, et al. Incidental meningiomas in autopsy study. Surg Neurol. 1987;27:319–22. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(87)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuratsu J, Kochi M, Ushio Y. Incidence and clinical features of asymptomatic meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:766–70. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.5.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1821–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yano S, Kuratsu J, Kumamoto Brain Tumor Research G Indications for surgery in patients with asymptomatic meningiomas based on an extensive experience. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:538–43. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.105.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sankila R, Kallio M, Jaaskelainen J, et al. Long-term survival of 1986 patients with intracranial meningioma diagnosed from 1953 to 1984 in Finland. Comparison of the observed and expected survival rates in a population-based series. Cancer. 1992;70:1568–76. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1568::aid-cncr2820700621>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaaskelainen J, Haltia M, Servo A. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: radiology, surgery, radiotherapy, and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:233–42. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirimanoff RO, Dosoretz DE, Linggood RM, et al. Meningioma: analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:18–24. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22–39. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condra KS, Buatti JM, Mendenhall WM, et al. Benign meningiomas: primary treatment selection affects survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:427–36. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldsmith BJ, Wara WM, Wilson CB, et al. Postoperative irradiation for subtotally resected meningiomas. A retrospective analysis of 140 patients treated from 1967 to 1990. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:195–201. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.2.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY. Advances in meningioma therapy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:231–40. doi: 10.1007/s11910-009-0034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Stafford SL, et al. "Malignancy" in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer. 1999;85:2046–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990501)85:9<2046::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wara WM, Sheline GE, Newman H, et al. Radiation therapy of meningiomas. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;123:453–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.123.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, et al. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. Third. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Group. NRaEW: NAACCR Guideline for Enhancing Hispanic/Latino Identification: Revised NAACCR Hispanic/Latino Identification Algorithm [NHIA v2.2.1] Springfield (IL): 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software. www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 8.1.5.

- 21.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. 2014 ( www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2013 Sub (2000–2011) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2012 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2014 (updated 5/7/2014), based on the November 2013 submission.

- 22.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15:547–69. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.1.1. Aug, 2014. Statistical Research and Applications Branch. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. 2014 ( www.seer.cancer.gov) Research Data (1973–2011), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2014, based on the November 2013 submission.

- 26.IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time-to-Event Data. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005–2009. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(Suppl 5):v1–49. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy BJ, Kruchko C, Dolecek TA. The impact of the Benign Brain Tumor Cancer Registries Amendment Act (Public Law 107–260) on non-malignant brain and central nervous system tumor incidence trends. J Registry Manag. 2013;40:32–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Kruchko C. Meningiomas: causes and risk factors. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E2. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/10/E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longstreth WT, Jr, Dennis LK, McGuire VM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Cancer. 1993;72:639–48. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<639::aid-cncr2820720304>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preston-Martin S, Mack W, Henderson BE. Risk factors for gliomas and meningiomas in males in Los Angeles County. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6137–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larjavaara S, Haapasalo H, Sankila R, et al. Is the incidence of meningiomas underestimated? A regional survey. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:182–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cahill KS, Claus EB. Treatment and survival of patients with nonmalignant intracranial meningioma: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:259–67. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.JNS101748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarthy BJ, Davis FG, Freels S, et al. Factors associated with survival in patients with meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:831–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.5.0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaaskelainen J. Seemingly complete removal of histologically benign intracranial meningioma: late recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrence in 657 patients. A multivariate analysis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:461–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santacroce A, Walier M, Regis J, et al. Long-term tumor control of benign intracranial meningiomas after radiosurgery in a series of 4565 patients. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:32–9. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31822d408a. discussion 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]