Abstract

Macrophages are an essential component of innate immunity and play a vital role in inflammation and host defense. Based on immunological responses, the macrophages are classified into “activated” macrophage (M1 macrophages) participating in the responses of type I helper T (Th1) cells to pathogens and “alternatively activated” macrophages (M2 macrophages) in response to interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13. In this review, we discuss the origin, classification and function of macrophages. We also discuss the mechanisms underlying polarization of different macrophage subtypes, including transcriptional, epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation.

Keywords: Macrophage, Phenotype, Polarization, Homeostasis, Cancer

Background

Since the discovery of macrophages by Metchnikoff in 1908 and their name conveys the ability to engulf foreign substances, biologists have been occupied with the concept of macrophages as regulators of the innate immune system [1]. To date, it is known that macrophages are not only scavengers of pathogens and dead cells but also important components of the tumor microenvironment, where they regulate tumor progression, matrix remodeling, angiogenesis and metastasis [2]. As the most plastic cells of the haematopoietic system, macrophages are found in all tissues and show great functional diversity. Although macrophages of various tissues are morphologically distinct from one another and have different transcriptional profiles and functional abilities, they are all required for the maintenance of homeostasis [3, 4]. However, the functions of macrophages can be subverted by chronic inflammation, resulting in a causal association of macrophages with disease states. Therefore, revealing the biological roles of macrophages can contribute to understanding the heterogeneity and function of macrophages.

Origin of macrophages

Macrophages have a broad role in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis, through the clearance of damaged cells and tissues and the repair of tissues. They are active in biosynthesis and express a wide range of receptors, which recognize foreign materials as well as normal and abnormal cells. In fact, macrophages are present in almost all tissues [1]. Macrophages differentiate from circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which migrate into tissue in response to inflammation or in the steady state. These PBMCs develop from a haematopoietic stem cell in the bone marrow that is the precursor of many different cell types, including granulocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages and mast cells. Monocytes develop from haematopoietic stem cells, and then sequentially give rise to granulocyte/macrophage colony-forming units, monoblasts, pro-monocytes and finally monocytes. Afterwards, monocytes are released from the bone marrow into the bloodstream [5, 6]. In the blood, monocytes are not a homogeneous population of cells. Although monocyte heterogeneity is not fully understood, it turns that monocytes migrate from the blood into tissues to differentiate into long-lived tissue-specific macrophages of the bone (osteoclasts), central nervous system (microglial cells), alveoli, gastrointestinal tract, connective tissue (histiocytes), liver (Kupffer cells), peritoneum and spleen [7]. Macrophages differ morphologically and phenotypically in different organs. Through endocytosis, phagocytosis and secretion of various products, including growth factors, cytokines and metabolites, macrophages perform both trophic and toxic functions, thus serving as a widely distributed mononuclear phagocyte during individual development and throughout the whole life.

Classification of macrophages

Activation of macrophages is a key area of tissue homeostasis, disease pathogenesis and inflammation. Differentiation and activation of macrophages depend on specific growth factors, receptors, signaling pathways and transcription factors. Over the last decades, diverse terms have been applied to macrophage activation, where toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist or cytokine treatment produces distinct patterns of gene and protein expression in macrophages [8]. M1- and M2-polarized macrophages also have distinct features in terms of the metabolism of iron, folate and glucose [9]. Besides, macrophages possess the ability to change their activation states in response to growth factors, cytokines, microbes, microbial products and other modulators [10, 11]. Macrophage activation is involved in the outcome of many diseases, including metabolic diseases, autoimmune diseases, cancers and infections.

Some specific cytokines, including granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) alone or together with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), can activate macrophages into M1 subtype [10]. Classical macrophage activation is characterized by high capacity to present antigen, high interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-23 production, low IL-10 production and consequent activation of a polarized type I response [12]. It is also accompanied with high production of inflammation cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α and IL-6) and toxic nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). M1 macrophages mediate the defense of animals against a variety of pathogens and play a key role in anti-tumor immunity [12].

As reported, IL-4 and IL-13 are found to be more than simple inhibitors of macrophage activation, in that they induce a distinct activation program, known as “alternative activation” [13]. Moreover, other cytokines such as IL-33 and IL-25 enhance alternatively activated macrophage induction indirectly through T helper 2 (Th2) cells [13, 14]. Studies have showed that alternatively activated macrophages present M2 phenotype. M2 cells are typically IL-12low, IL-23low and IL-10high and generally characterized by low production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α and IL-6) [12]. M2 macrophages have high levels of scavenger-, mannose-, and galactose-type receptors, and the arginine metabolism is shifted to polyamines and ornithine [15]. In general, M2 macrophages are a component of polarized Th2 responses. Hence, M2 macrophages function in a range of physiologic and pathological processes, including homeostasis, anti-inflammation, repair, metabolic functions and malignancy.

Underlying mechanisms of macrophage polarization

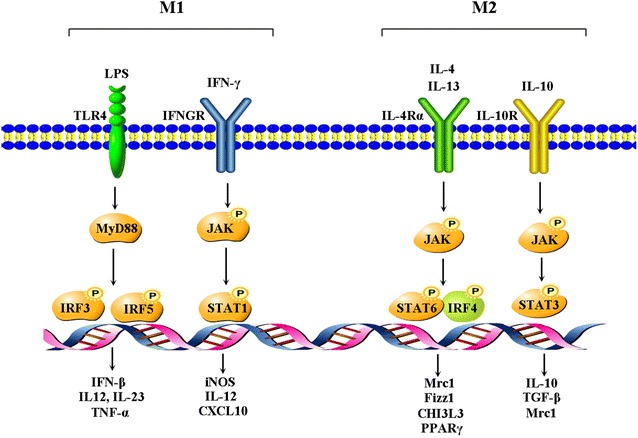

A network of signaling molecules, transcription factors, epigenetic mechanisms, and post-transcriptional regulators underlies the different phenotypes of macrophages (Fig. 1). As reported, IFN-γ triggers the phosphorylation and dimerization of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), thus initiating the transcription of M1-associated genes (iNOS, Il12 and CXCL10) [16] (Fig. 1). LPS stimulation results in IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) activation via Toll-like receptor adaptor molecule 1 (TICAM1)-dependent Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) motivation [17] (Fig. 1). Hence, the IFN-β expression and activation of STAT1 and STAT2 are initiated. Notch-RBP-J signaling also controls expression of the transcription factor IRF8 that induces downstream M1 macrophage-associated genes after TLR4 activation [17]. Besides, M1 macrophages upregulate IRF5, which is essential for induction of cytokines (IL-12, IL-23 and TNF-α) involved in eliciting Th1 and Th17 responses [18]. However, IL-4 and IL-13 treatment leads to the production of M2 macrophages via STAT6 signaling pathway [19]. Activated STAT6 in turn recruits IRF4 and activates transcription of genes typical of M2 macrophages, e.g., mannose receptor C1 (Mrc1), resistin-like α (Fizz1), chitinase 3–like 3 (Chi3l3) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARg). The interaction between PPARγ and STAT6 facilitates DNA binding and the expressions of various M2-related genes [19] (Fig. 1). IL-6 and leukemia-inhibitory factor, present at high concentrations in ovarian cancer ascites, differentiate monocytes into M2 macrophages by increasing macrophage colony-stimulating factor consumption [20]. IL-10 can activate STAT3-mediated gene expressions, such as Il10, Tgfb1 and Mrc1, which are associated with M2 phenotype [12, 21] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Molecular pathways of macrophage polarization. LPS and IFN-γ trigger the activation of TLR4 and IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR) pathways and induce the phosphorylation of the transcription factors IRF3, IRF5 and STAT1, leading to the transcription of M1-related genes. IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathway is triggered via IL-4Rα to activate STAT6 and IRF4, thus regulating the expression of M2-related genes. IL-10 signals through IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) to activate STAT3, thereby triggering M2-like macrophage polarization

Macrophage development, polarization and activation are also controlled by epigenetic changes. Epigenetic regulation is typically mediated by post-translational modifications (methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation) of histones and other chromatin proteins that bind DNA. The methylation and hydroxymethylation of CpG DNA motifs alter gene expression in macrophages [22]. During M1 polarization, master transcription factors, such as PU.1 and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα), bind to and open the regulatory regions (promoters and enhancers) of M1-related genes [23]. Enhancers are marked by H3K4me1, PU.1 and open chromatin, as demonstrated by high sensitivity of DNase I digestion [23]. Furthermore, TLR stimulation results in the release of the above epigenetic ‘brakes’, for example concomitant induction or activation of demethylases such as JMJD3, JMJD2d, PHF2 and AOF1 that erase the negative histone marks H3K9me3, H3K27me3 and H4K20me3 [24]. Alternative activation of macrophages is mediated by histone demethylase JMJD3, which facilitates the expression of M2-promoting transcription factor IRF4 by removing negative H3K27me3 marks at the Irf4 locus [25]. By contrast, HDAC3 acts as a suppressor on IL-4-induced M2 polarization by deacetylation of enhancers of IL-4-induced genes [25]. Therefore, both histone methylation and acetylation are important for M2 polarization.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding small RNAs that play important gene-regulatory roles in animals and plants by pairing to the mRNAs of protein-coding genes to direct their post-transcriptional repression [26]. It is increasingly clear that many miRNAs display tissue- or cell-type-specific expression patterns in cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism [27]. Upon LPS and IFN-γ stimulation, the expression levels of miRNAs involved in M1 phenotype polarization are significantly increased, including miR-155, miR-125a/b and let-7e [28–30]. As reported, miR-155 enhances Tnfa mRNA stability as inhibition of miR-155 decreases Tnfa mRNA half-life, while overexpression of miR-155 increases Tnfa mRNA [31]. miR-125a/b directly targets the negative NF-κB regulator TNF alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3), thus reinforcing NF-κB transcriptional activity [32]. miR-146, miR-9, miR-21 and miR-147 participate in M1 polarization by forming a negative feedback loop with NF-κB [33, 34]. Moreover, miR-223 can be induced by LPS and in turn inhibits the activation of M1 macrophages [35]. On the other hand, miR-187, miR-378-3p and miR-511-3p are engaged in M2 activation [36, 37]. miR-187 recruits Tnfa mRNA into RNA induced silence complex (RISC), leading to the degradation of this mRNA. AKT1 signaling suppresses the IL-4-induced M2-realted genes’ expressions, e.g., Mrc1, Fizz1 and Chi3l3 [38]. miR-378-3p involves in the M2 macrophage activation by targeting AKT1 signaling pathway [37]. miR-511-3p locates in the fifth intron of Mrc1 gene and is co-transcribed with Mrc1, indicating that miR-511-3p is a typical alternatively activated miRNA during macrophage alternative activation [36].

Macrophages and tissue homeostasis

Mature macrophages are located throughout the body and perform important functions of immune surveillance. They survey their immediate surroundings for signs of tissue damage or invading organisms and are subjected to stimulating immune cells to respond when danger signals are detected by cell surface receptors [39, 40]. Following tissue injury or infection, the macrophages usually exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype and secrete pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-1, ΝΟ and ROS, which participate in the activation of various antimicrobial mechanisms. Moreover, IL-12 and IL-23 are expressed by activated macrophages and further influence the polarization of Th1 and Th17 cells [41].

In addition to fighting pathogen infections, resident tissue macrophages are involved in maintaining healthy tissues by removing dead and dying cells and toxic substances. Macrophages are selective of the substance that they eliminate by recognition of cell receptors with ligands [42]. During phagocytosis of macrophages, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize signals of invading pathogens, foreign substances and dead cells. Afterwards, transcriptional mechanisms are activated that lead to phagocytosis and release of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors. Besides, macrophages also secret numerous molecules, including complement and Fc receptors, C3b and antibodies [2]. Therefore, macrophages monitor and respond to changes in their environment by surface receptors and secreted molecules.

Macrophages in cancers

If the inflammatory macrophage response against infection or injury is not quickly controlled, it will become pathogenic and leads to disease progression. To impede the damage of the inflammatory response, macrophages usually undergo apoptosis or transform into an anti-inflammatory phenotype that facilitates wound healing. It is becoming clear that the mechanisms underlying the conversion of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages have a major effect on the progression and resolution of chronic diseases, including asthma, atherosclerosis, fibrosis, autoimmune diseases and cancer [43, 44]. Here, this review focuses on the roles of macrophages in cancer initiation and progression.

Cancer is a hyperproliferative disorder that involves morphological cellular transformation, uncontrolled cellular proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis. In the tumor tissues, except for cancer cells, there are fibroblasts, endothelial cells and immune cells, which constitute tumor microenvironment (TME) [45]. Macrophages are the major immune cells in TME. More and more evidences show that macrophage density of TME correlates with cancer progression and poor prognosis [46–49]. During tissue injury or infection, M1 macrophages produce a series of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, ΝΟ and ROS [50]. On one hand, ΝΟ and ROS are highly toxic for microorganisms as well as adjacent tissues and lead to aberrant inflammation. On the other hand, they can induce a mutagenic environment and genetic instability of adjacent epithelial cells by inhibiting the function of p53 and by increasing the activity of DNA methylase, which leads to an increment on CpG island methylation and an erroneous gene transcription [51]. TNF-α produced by M1 macrophages promotes tumor cell proliferation and neoangiogenetic abilities through the induction of genes encoding anti-apoptotic molecules [52]. M1 macrophages also contribute to constitutive activation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB and STAT3 [53, 54]. NF-κB activation in tumor cells can promotes tumor progression by enhancing their aggressive potential and increase the transcriptions of proinflammatory and angiogenetic genes, for example IL-12, TNF-α and iNOS [53]. Activation of STAT3 leads to resistance to apoptosis in tumor cells and to a tolerant tumor environment [54]. Besides, M1 macrophage-secreted epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) facilitate epithelial growth and survival [55]. Herein, chronic inflammation induces cancer occurrence and M1 macrophage is a vital participant in this process.

Once tumors become established, they cause macrophage differentiation so that the macrophages change from M1 phenotype to M2 phenotype that promotes tumor progression and malignancy. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) has been shown to be involved in changing the macrophage phenotype from M1 to M2 [56, 57]. M2 cells develop defective NF-κB activation during tumor progression by constitutive formation of p50 homodimers, leading to a reduced expression of iNOS accompanied by an impaired ability to produce NO and a reduced TNF-α secretion [58]. The Notch signaling pathway is also involved in the generation of M2-macrophages [59]. Notch is up-regulated in M1 macrophages, which leads to increased IL-12 production. M2 macrophages in progressing tumors have been shown to down-regulate Notch [59]. Cytokines are involved in the differentiation of M2 macrophages. CXCL12, which is highly produced in the tumor environment, has been shown to not only mediate recruitment and migration of monocytes to the tumor tissue, but also participate in differentiating macrophages towards immunosuppressive M2 macrophages by up-regulating chemokine [C–C motif] ligand 1 (CCL1) expression [60]. M2 macrophages express a variety of proangiogenic cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), IL-8 and enzymes, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and COX-2 [61]. VEGF deficiency in macrophages significantly inhibits tumor angiogenesis, while overexpression of VEGF facilitates tumor angiogenesis and progression [62]. Besides, macrophages also participate in the junction and remodeling of new blood vessels [63].

Metastasis, which represents the migration of cancer cells from the primary tumor to a distant organ or tissue, is the most frequent cause of poor prognosis and death for patients with cancer. The steps of metastasis include tumor cell adhesion and invasion of basement membranes and the surrounding tissue, intravasation into blood vessels, survival in the bloodstream, extravasation from blood vessels, and growth at different organ sites [64]. Cancer researchers have focused their studies on macrophage- secreted factors that potentially influence cancer cell migration, invasion or adhesion. To date, EGF, CCL18, IL-18, IL-1β and IL-8 secreted by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have been extensively investigated [65–68]. Our previous study indicated that M2 macrophages-secreted CHI3L1 (chitinase 3-like protein 1) protein specifically bound to the interleukin (IL)-13 receptor α2 chain (IL-13Rα2) of gastric and breast cancer cells, thus promoting cancer metastasis [69]. Paracrine loops of EGF/colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and CCL18/granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) between M2 macrophages and cancer cells have been shown to increase carcinoma cell invasion [70]. Besides, macrophage-produced osteonectin in the tumor extracellular matrix (ECM) is engaged in cancer cell migration by facilitating cancer cell adhesion to fibronectin [71].

Relationship between myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and TAMs in cancer

As discussed above, cancer initiation and progression are assisted by TAMs. A high frequency of TAMs is associated with poor prognosis in many tumors [72, 73]. MDSCs have attracted increased attention, and their presence in the blood of cancer patients is emerging as a simple prognostic marker to monitor clinical outcome and therapy. MDSCs are characterized by myeloid origin, heterogeneity and ability to downregulate immune responses in cancer [74]. Immunosuppressive MDSCs with monocytic features can traffic from bone marrow to tumor tissues, mainly through the same chemokine pathway of CCR2/CCL2 axis with TAMs [75].

In tumor-bearing hosts, generation of MDSC and TAM requires the integration of two types of signals: factors that expand myeloid precursors and factors that activate immune-regulatory programs [4, 76–78]. CSF1, granulocyte-CSF (G-CSF), and GM-CSF are the three major regulators of myeloid lineage proliferation and differentiation [76]. G-CSF promotes the differentiation of myeloid precursors into MDSCs. The master factor for TAM recruitment and programming in the TME is CSF1 [4]. IL-4 and IL-13 participate in both TAM and MDSC survival and the acquisition of an immunosuppressive phenotype [77]. Metabolic environmental signals can also modulate the intratumoral distribution of myeloid cells [78].

The activities of MDSC and TAM not only contribute to an immunosuppressive environment that keeps T cells at bay and protect tumors from the effects of the immune system, but include mechanisms that sustain and promote tumor growth and metastasis [79]. TAMs and MDSCs exert their immunosuppressive effects in an antigen-specific or antigen-nonspecific manner [79]. To sustain the immunosuppressive environment, TAMs and MDSCs secrete kinds of chemokines acting on CCR5 and CCR6, which are involved in Treg recruitment. MDSCs can also skew macrophages toward an M2 phenotype through a cell contact–dependent mechanism, characterized by decreased production of IL-12 [80]. The downregulation of IL-12 is further enhanced by the macrophages themselves, because TAMs stimulate an additional IL-10 release by MDSCs, thereby creating a negative loop. Therefore, TAMs and MDSCs regulate the intratumoral IL-10 and IL-12 balance, which is critical for triggering T cell responses [81].

Conclusions

As essential regulators of inflammation and host defense, macrophages exert a dual influence on tumor growth and progression. Plasticity and heterogeneity are hallmarks of the macrophage lineage. Hence, the specific markers used to distinguish M1 and M2 phenotypes require further standardization and development. Previous studies have revealed that adaptive immunity can orchestrate cancer-promoting inflammation and TAMs through various molecular pathways [82]. Thus, the development of effective strategies to block cancer-promoting inflammation or to activate protective innate immunity will contribute to the control of cancer initiation and progression. As cancer is a worldwide problem, screening of specific agents or inhibitors targeting recruitment or cancer-promoting activity of TAMs and MDSCs in TME will be helpful to control cancers [73, 83, 84].

Authors’ contributions

YC and XZ drafted and prepared the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31430089) and National Program on the Key Basic Research Project (2015CB755903).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- Th1 cells

type I helper T cells

- IL-4

interleukin-4

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- GM-CSF

granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NO

nitric oxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- TICAM-1

toll-like receptor adaptor molecule 1

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- Mrc1

mannose receptor C1

- Fizz1

resistin-like α

- Chi3l3

chitinase 3–like 3

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- C/EBPα

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α

- miRNA

microRNA

- TNFAIP3

TNF alpha-induced protein 3

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase 2

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- CCL18

chemokine [C–C motif] ligand 18

- TAMs

tumor-associated macrophages

- CHI3L1

chitinase 3-like protein 1

- IL-13Rα2

interleukin-13 receptor α2 chain

- CSF-1

colony-stimulating factor 1

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- ECM

extracellular matrix

Contributor Information

Yulei Chen, Email: biochenyulei@163.com.

Xiaobo Zhang, Phone: 86-571-88981129, Email: zxb0812@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:9–17. doi: 10.1038/ni.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian B-Z, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto D, Miller J, Merad M. Dendritic cell and macrophage heterogeneity in vivo. Immunity. 2011;35:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaguin M, Houlbert N, Fardel O, Lecureur V. Polarization profiles of human M-CSF-generated macrophages and comparison of M1-markers in classically activated macrophages from GM-CSF and M-CSF origin. Cell Immunol. 2013;281:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sica A, Larghi P, Mancino A, Rubino L, Porta C, Totaro MG, et al. Macrophage polarization in tumour progression. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YJ, Yang CK, Wei PL, Huynh TT, Whang-Peng J, Meng TC, et al. Ovatodiolide suppresses colon tumorigenesis and prevents polarization of M2 tumor-associated macrophages through YAP oncogenic pathways. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:60. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0421-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caccamo N, Todaro M, Sireci G, Meraviglia S, Stassi G, Dieli F. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of human γδ T cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:30–34. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 2013;229:176–185. doi: 10.1002/path.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labonte AC, Tosello-Trampont A-C, Hahn YS. The role of macrophage polarization in infectious and inflammatory diseases. Mol Cells. 2014;37:275–285. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu H, Zhu J, Smith S, Foldi J, Zhao B, Chung AY, et al. Notch-RBP-J signaling regulates the transcription factor IRF8 to promote inflammatory macrophage polarization. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:642–650. doi: 10.1038/ni.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krausgruber T, Blazek K, Smallie T, Alzabin S, Lockstone H, Sahgal N, et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1–TH17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:231–238. doi: 10.1038/ni.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szanto A, Balint BL, Nagy ZS, Barta E, Dezso B, Pap A, et al. STAT6 transcription factor is a facilitator of the nuclear receptor PPARγ-regulated gene expression in macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;33:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeannin P, Duluc D, Delneste Y. IL-6 and leukemia-inhibitory factor are involved in the generation of tumor-associated macrophage: regulation by IFN-γ. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:23–26. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda E, Ho V, Ruschmann J, Antignano F, Hamilton M, Rauh MJ, et al. SHIP represses the generation of IL-3-induced M2 macrophages by inhibiting IL-4 production from basophils. J Immunol. 2009;183:3652–3660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivashkiv LB. Epigenetic regulation of macrophage polarization and function. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stender JD, Pascual G, Liu W, Kaikkonen MU, Do K, Spann NJ, et al. Control of proinflammatory gene programs by regulated trimethylation and demethylation of histone H4K20. Mol Cell. 2012;48:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Santa F, Narang V, Yap ZH, Tusi BK, Burgold T, Austenaa L, et al. Jmjd3 contributes to the control of gene expression in LPS-activated macrophages. EMBO J. 2009;28:3341–3352. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satoh T, Takeuchi O, Vandenbon A, Yasuda K, Tanaka Y, Kumagai Y, et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:936–944. doi: 10.1038/ni.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:509–524. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Nunez RT, Louafi F, Sanchez-Elsner T. The interleukin 13 (IL-13) pathway in human macrophages is modulated by microRNA-155 via direct targeting of interleukin 13 receptor α1 (IL13Rα1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1786–1794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, Hou J, Lin L, Wang C, Liu X, Li D, et al. Inducible microRNA-155 feedback promotes type I IFN signaling in antiviral innate immunity by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. J Immunol. 2010;185:6226–6233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graff JW, Dickson AM, Clay G, McCaffrey AP, Wilson ME. Identifying functional microRNAs in macrophages with polarized phenotypes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21816–21825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bala S, Marcos M, Kodys K, Csak T, Catalano D, Mandrekar P, et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-155 in macrophages contributes to increased tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) production via increased mRNA half-life in alcoholic liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1436–1444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S-W, Ramasamy K, Bouamar H, Lin A-P, Jiang D, Aguiar RC. MicroRNAs miR-125a and miR-125b constitutively activate the NF-κB pathway by targeting the tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, A20) Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Rao DS, Yang L, Zhao JL, Kalwani M, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1189–1201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, Martin C, O’leary JJ, Ruan Q, et al. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang G, Meng C, Guo X, Cheruku PS, Shi L, Xu H, et al. A novel regulator of macrophage activation: miR-223 in obesity associated adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Squadrito ML, Etzrodt M, De Palma M, Pittet MJ. MicroRNA-mediated control of macrophages and its implications for cancer. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossato M, Curtale G, Tamassia N, Castellucci M, Mori L, Gasperini S, et al. IL-10–induced microRNA-187 negatively regulates TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12p40 production in TLR4-stimulated monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:E3101–E3110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres A, Makowski L, Wellen KE. Metabolism fine-tunes macrophage activation. eLife. 2016;5:e14354. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amit I, Winter DR, Jung S. The role of the local environment and epigenetics in shaping macrophage identity and their effect on tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:18–25. doi: 10.1038/ni.3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jantsch J, Schultze JL, Kurts C. Immunophysiology: macrophages as key regulators of homeostasis in various organs. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2017;469:363–364. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-1963-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:986–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ostuni R, Kratochvill F, Murray PJ, Natoli G. Macrophages and cancer: from mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Overmeire E, Laoui D, Keirsse J, Van Ginderachter JA, Sarukhan A. Mechanisms driving macrophage diversity and specialization in distinct tumor microenvironments and parallelisms with other tissues. Front Immunol. 2014;5:127. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chanmee T, Ontong P, Itano N. Hyaluronan: a modulator of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2016;375:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Yang L, Zhang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: from basic research to clinical application. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopez-Bujanda Z, Drake CG. Myeloid-derived cells in prostate cancer progression: phenotype and prospective therapies. J Leukoc Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1189/jlb.5VMR1116-491RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohno S, Inagawa H, Soma G, Nagasue N. Role of tumor-associated macrophage in malignant tumors: should the location of the infiltrated macrophages be taken into account during evaluation? Anticancer Res. 2002;22:4269–4275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cannarile MA, Ries CH, Hoves S, Rüttinger D. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages in cancer therapy and understanding their complexity. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e955356. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.955356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cobbs CS, Whisenhunt TR, Wesemann DR, Harkins LE, Van Meir EG, Samanta M. Inactivation of wild-type p53 protein function by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in malignant glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8670–8673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Simone V, Franze E, Ronchetti G, Colantoni A, Fantini MC, Di Fusco D, et al. Th17-type cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-α synergistically activate STAT3 and NF-κB to promote colorectal cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2015;34:3493–3503. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ben-Neriah Y, Karin M. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-κB as the matchmaker. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:715–723. doi: 10.1038/ni.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Wang T, Wei S, Zhang S, Pilon-Thomas S, et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:1314–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Investig. 2007;117:1175–1183. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakanishi Y, Nakatsuji M, Seno H, Ishizu S, Akitake-Kawano R, Kanda K, et al. COX-2 inhibition alters the phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages from M2 to M1 in ApcMin/+ mouse polyps. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1333–1339. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris RE. Cyclooxygenase-2 (cox-2) blockade in the chemoprevention of cancers of the colon, breast, prostate, and lung. Inflammopharmacology. 2009;17:55–67. doi: 10.1007/s10787-009-8049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saccani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, Biswas SK, Nebuloni M, Vago L, et al. p50 nuclear factor-κB overexpression in tumor-associated macrophages inhibits M1 inflammatory responses and antitumor resistance. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11432–11440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang YC, He F, Feng F, Liu XW, Dong GY, Qin HY, et al. Notch signaling determines the M1 versus M2 polarization of macrophages in antitumor immune responses. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4840–4849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanchez-Martin L, Estecha A, Samaniego R, Sanchez-Ramon S, Vega MA, Sanchez-Mateos P. The chemokine CXCL12 regulates monocyte-macrophage differentiation and RUNX3 expression. Blood. 2011;117:88–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peterson TE, Kirkpatrick ND, Huang Y, Farrar CT, Marijt KA, Kloepper J, et al. Dual inhibition of Ang-2 and VEGF receptors normalizes tumor vasculature and prolongs survival in glioblastoma by altering macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:4470–4475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525349113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ager EI, Kozin SV, Kirkpatrick ND, Seano G, Kodack DP, Askoxylakis V, et al. Blockade of MMP14 activity in murine breast carcinomas: implications for macrophages, vessels, and radiotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:1–12. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bravo-Cordero JJ, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. Directed cell invasion and migration during metastasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hou Z, Falcone DJ, Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ. Macrophages induce COX-2 expression in breast cancer cells: role of IL-1β autoamplification. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:695–702. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaler P, Augenlicht L, Klampfer L. Macrophage-derived IL-1β stimulates Wnt signaling and growth of colon cancer cells: a crosstalk interrupted by vitamin D3. Oncogene. 2009;28:3892–3902. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang J, Liao D, Chen C, Liu Y, Chuang TH, Xiang R, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages regulate murine breast cancer stem cells through a novel paracrine EGFR/Stat3/Sox-2 signaling pathway. Stem Cells. 2013;31:248–258. doi: 10.1002/stem.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhong L, Roybal J, Chaerkady R, Zhang W, Choi K, Alvarez CA, et al. Identification of secreted proteins that mediate cell–cell interactions in an in vitro model of the lung cancer microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7237–7245. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen Y, Zhang S, Wang Q, Zhang X. Tumor-recruited M2 macrophages promote gastric and breast cancer metastasis via M2 macrophage-secreted CHI3L1 protein. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:36. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0408-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su S, Liu Q, Chen J, Chen J, Chen F, He C, et al. A positive feedback loop between mesenchymal-like cancer cells and macrophages is essential to breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:605–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sangaletti S, Di Carlo E, Gariboldi S, Miotti S, Cappetti B, Parenza M, et al. Macrophage-derived SPARC bridges tumor cell-extracellular matrix interactions toward metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9050–9059. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang QW, Liu L, Gong CY, Shi HS, Zeng YH, Wang XZ, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in solid tumor: a meta-analysis of the literature. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang M, Liu F, Higuchi K, Sawashita J, Fu X, Zhang L, et al. Serum amyloid A expression in the breast cancer tissue is associated with poor prognosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:35843–35852. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Montero AJ, Diaz-Montero CM, Kyriakopoulos CE, Bronte V, Mandruzzato S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients: a clinical perspective. J Immunother. 2012;35:107–115. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318242169f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lesokhin AM, Hohl TM, Kitano S, Cortez C, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Avogadri F, et al. Monocytic CCR2(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:876–886. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Casbon AJ, Reynaud D, Park C, Khuc E, Gan DD, Schepers K, et al. Invasive breast cancer reprograms early myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow to generate immunosuppressive neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E566–E575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424927112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gray MJ, Poljakovic M, Kepka-Lenhart D, Morris SM., Jr Induction of arginase I transcription by IL-4 requires a composite DNA response element for STAT6 and C/EBPβ. Gene. 2005;353:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Savage ND, de Boer T, Walburg KV, Joosten SA, van Meijgaarden K, Geluk A, et al. Human anti-inflammatory macrophages induce Foxp3+ GITR+ CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress via membrane-bound TGFβ-1. J Immunol. 2008;181:2220–2226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schlecker E, Stojanovic A, Eisen C, Quack C, Falk CS, Umansky V, et al. Tumor-infiltrating monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells mediate CCR5-dependent recruitment of regulatory T cells favoring tumor growth. J Immunol. 2012;189:5602–5611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P, Beury DW, Clements VK. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), macrophages, and dendritic cells enhances tumor-induced immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andreu P, Johansson M, Affara NI, Pucci F, Tan T, Junankar S, et al. FcRγ activation of regulates inflammation-associated squamous carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ngambenjawong C, Gustafson HH, Pun SH. Progress in tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-targeted therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Denton NL, Chen CY, Scott TR, Cripe TP. Tumor-associated macrophages in oncolytic virotherapy: friend or foe? Biomedicines. 2016;4. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines4030013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.