Abstract

Impaired immune reconstitution after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is attributed in part to impaired thymopoiesis. Recent data suggest that precursor input may be a point of regulation for the thymus. We hypothesized that administration of FLT3 Ligand (FLT3L) would enhance thymopoiesis following adoptive transfer of aged FLT3L treated marrow to Lupron-treated aged hosts by increasing murine HSC (LSK cells) trafficking and survival. In murine models of aged and young hosts, we show that FLT3L enhances thymopoiesis in aged Lupron-treated hosts through increased survival and export of LSK cells via CXCR4 regulation. In addition, we elucidate an underlying mechanism of FLT3L action on marrow LSK cells, that FLT3L drives LSK cells into the stromal niche using hoescht (Ho) dye peri-mortem. Thus, in summary, we show that FLT3L administration leads to: 1) increased LSK cells and ETP precursors that can enhance thymopoeisis after transplantation and androgen withdrawal, 2) mobilization of LSK cells through down-regulation of CXCR4, 3) enhanced marrow stem cell survival associated with Bcl-2 up-regulation, and 4) marrow stem cell enrichment through increased trafficking to the marrow niche. Thus, we show a mechanism by which FLT3L activity on hematopoeitic and thymic progenitor cells may contribute to thymic recovery. These data have potential clinical relevance to enhance thymic reconstitution after cyto-reductive therapy.

Keywords: FLT3 ligand, stromal niche, CXCR4, androgen withdrawal, thymopoiesis, hematopoietic stem Cell transplantation

Introduction

Impaired thymic function contributes to immune dysregulation following lymphopenia or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) 1–3, due to reduced de novo naïve T cells production and loss of central T cell tolerance4. This delayed thymic recovery is associated with increased rates of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), infections, and relapse3,5–9. Revealing points of regulation constraining thymic recovery may provide targets to enhance thymic function following HSCT.

Many studies have shown that androgen withdrawal increases thymic function with subsequent increase in peripheral naïve T cells in both unmanipualted male mice and in the setting of hematopoietic transplantation10–16. Increased recent thymic emigrants (RTE) in these settings confirmed the thymic contribution 13,17–19. Our group showed that the sequence of events underlying this process included: expansion of thymic epithelial cells, increased thymic stromal production of CCL25, increased entry of marrow precursors, and accelerated thymocyte development20. Thus, agents that could increase thymic precursor cell number could improve thymic reconstitution in the setting of intra-thymic signaling through androgen withdrawal.

FLT3L is endogenously produced by both mice and humans and is important for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) generation and survival in-vitro21–23. FLT3L knock-out (KO) mice show reduced immature thymocytes and fewer lymphoid-primed multipotent marrow progenitors (FLT3+ LSK CELLS) suggesting that this cytokine may be important in de novo thymus-derived T cell development28,29. While mature T cell populations were normal in FLT3LKO mice, T cell reconstitution following HCST is impaired with FLT3LKO mice as donors or recipients25,29,. Others substantiated a role for FLT3L in post-natal and post-BMT early thymocyte progenitor (ETP) uptake during thymic reconstitution30,31, suggesting that FLT3L would be a good candidate to enhance thymic recovery after BMT, which was suggested though not tested in prior studies32.

In the present study, we investigate the role of FLT3L on marrow thymic precursors, and thymic recovery after HSCT. We show that FLT3L does not directly enhance thymopoiesis, but rather enhances export of early thymic progenitors that contribute to thymic reconstitution during times when progenitor import constrains thymic recovery, such as after HSCT. We suggest that this is due to enhanced survival and export of precursors, specifically through upregulation of the anti-apoptotic factor, Bcl-2, rather than increased proliferation. Finally, we purport that this occurs through regulation of CXCR4 expression and enhanced progenitor-stromal interactions without increase in stromal number following FLT3L exposure. These data support a model whereby immature HSC are driven into stroma, receive survival signals, and exceed niche number, leading to export to other niche (e.g. spleen).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Age-matched post-pubertal C57BL/6(B6)-Ly5.1 and B6 (Ly5.2) (congenic) male mice were purchased from the Animal Production Unit, National Cancer. Animal care and experimental procedures were carried out under NCI approved protocols. FLT3LKO mice were obtained from Taconic Farms under an MTA with NIAID28. Young mice were chosen as the earliest age post-puberty (aged 2 months or less) to be similar to a young adult donor (age 18–30 years) and elder mice were chosen as greater than 4 months of age to mimic donors exceeding 40–50 years of life.

Lupron procedure

Animals were treated with Lupron 3 month depot at a dose of 3 mg/kg/mouse subcutaneously in 1 dose 2 weeks prior to BMT. Sham animals were injected subcutaneously with saline at the same time point.

FLT3L administration

Animals treated with recombinant human FLT3L (PeproTech) received a dose of 5 ug/mouse/day via Alzet pump (7 day). Sham treated mice received PBS via Alzet pump (7 day).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions of thymus, spleen, and bone marrow (BM) were harvested and counted at various time points. Cells from the spleen, and BM were subjected to ACK lysis to remove red blood cells. All flow cytometry specimens were incubated with anti-Fcγ III/II receptor (2.4G2) blocking antibody prior to staining. Samples were labeled using combinations of the following antibodies: CD4, CD8, CD3, CD44, CD25, B220, AA4.1, CD45.2, CD45.1, CD45, Sca-1, c-kit (APC (eBioscience) or PE), and IL7Rα (eBioscience), FLT3 (eBioscience), CCR9 (R&D systems), CD11c, CD31, Gr-1, Ki-67, Bcl-2 (Biolegend), CXCR4 (BD or Biolegend), CD150 (eBioscience), CD47 (Biolegend). For DN and ETP/LSK cells subset determination, mature cells were labeled with biotinylated lineage markers: TER, CD8α, H57, Gr1, Mac1, NK1.1, IgM, CD19, B220, CD3, and CD11c. Biotinylated antibodies were developed with streptavidan pacific blue (Invitrogen). All antibodies were purchased from BD unless indicated otherwise. Isotype controls were utilized for all rare populations, including florescence minus one controls. Four, five, and six color panels were acquired on a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). All data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Software).

BrdU incorporation

Older age-matched C57BL/6 male mice were injected i.p. with 2 mg BrdU after 1 week of continuous FLT3L or PBS exposure. Mice were sacrificed 2 hours following BrdU injection. For all BrdU studies, C57BL/6 male mice not exposed to BrdU were used to define the BrdU negative population. Cells were processed and stained using labeling and detection kits BrdU (BD Biosciences) using either FITC or APC conjugated anti-BrdU antibodies.

Adoptive transfer of congenic T-cell depleted bone marrow

BM from C57BL/6 (> 4 month-old male mice) treated with PBS or FLT3L (by Alzet pump as above) was T cell depleted (TCD) using anti-CD8 and -Thy1.2 conjugated paramagnetic beads and Midi separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec). One million BM cells were injected intravenously into congenic (Ly5.2) aged hosts that received Lupron (as above) or PBS one day after receiving 900 cGy. Immune reconstitution was evaluated at 6 weeks.

FLT3L with or without CXCR4 antibody exposure

BM and splenic cells from C57BL/6 5 month old female mice treated with FLT3L (as above, Alzet pump) with or without CXCR4 antibody (R&D systems) 100 ug/mouse/dose injected i.p. for 3 days (day 1–3 of FLT3L exposure).

Measurement of marrow stroma

Femurs were removed from mice after treatment with FLT3L or PBS. Marrow stroma was extracted and digested per Christopher et al34 and then stained for FLT3Low cytometry analysis.

Evaluation of LSK CELLS with respect to position in marrow stroma

Six month old C57BL/6 mice treated with FLT3L or control were injected with 0.8 mg of Hoecsht dye (per 25g body weight) retro-orbital at 10 minutes and 5 minutes pre-euthanasia followed by tissue extraction35. Tissues were collected in buffer with Reserpine (Sigma) and Verapamil (Sigma) to maintain Hoecsht dye within exposed cells. Cells were immediately processed and evaluated by FLT3Low cytometry using LSRII (antibodies for FLT3Low cytometry above).

Statistical analysis

All experimental groups included greater than or equal to 5 mice per group and represented mean data from multiple experiments. Error bars are shown on all relevant figures. Statistical analysis was performed using Statview 5.0.1 software. All studies were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-test.

Results

Exogenous FLT3L does not alter thymic function

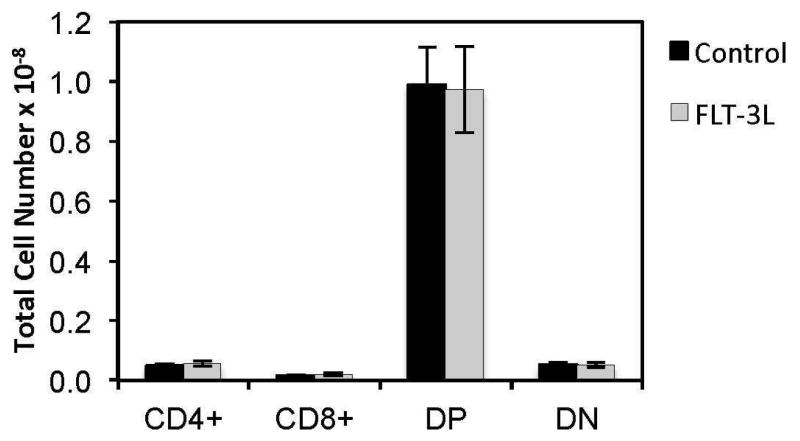

First, we investigated whether FLT3L enhanced thymopoiesis, as had been previously postulated due to elevations in naïve splenic T cells following FLT3L administration 32. Our data recapitulated that of others, with increased naïve splenic T cells, demonstrating a reproducible model (data not shown). Surprisingly, thymocyte numbers were unaltered between FLT3L treated mice and PBS treated age-matched control littermates (performed in young (2 month old) and older (>4 month old) mice, (data for 2 month old mice shown, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exogenous FLT3L does not alter thymic function in young or old mice.

Panel (A) and (B) demonstrate that thymic subsets are unaltered after 1 week of FLT3L exposure in young and old mice respectively.

Exogenous FLT3L enriches marrow LSK cells in young and older mice

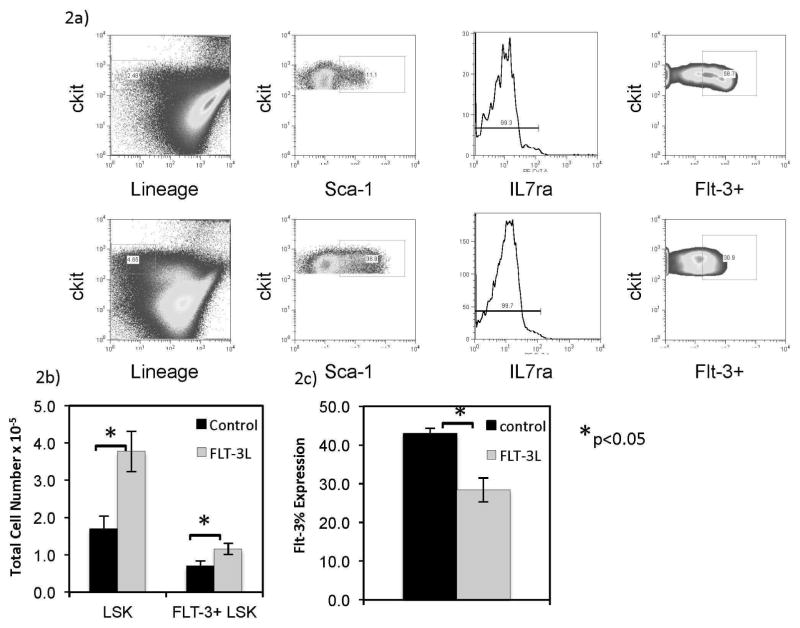

Previously published data showed an enhanced thymopoiesis after FLT3L administration in the context of bone marrow transplantation (BMT)30,31. We hypothesized that this was due to an expansion of marrow progenitors. As shown by others, exogenous FLT3L profoundly increased the marrow LSK cells (p<0.05) and FLT3+ LSK cells (p<0.05) total numbers in young and older mice (Figure 2A–B). This increase in LSK cell number demonstrated an increase in LSK cells proportion as well (Figure 2B). In addition, FLT3 expression on marrow LSK cells (by flow cytometry) was diminished after FLT3L exposure (p<0.05) (Figure 2C), which could be due to downregulation after consumption of FLT3L or due to trafficking of LSK cells highly expressing the FLT3 receptor out of the marrow compartment.

Figure 2. Exogenous FLT3L enriches marrow LSK cells in young and older mice.

Representative flow cytometry plots are shown for LSK cells gating (marrow live cells, Lineage negative, c-Kit hi, Sca-1 positive, IL7Rα negative) including FLT3 after 1 week of control and FLT3L exposed mice (A). Marrow LSK cells were enumerated at this time point using flow cytometry analysis for aged matched mice (B) after 1 week of FLT3L exposure or control. FLT3 expression proportion decreased (C).

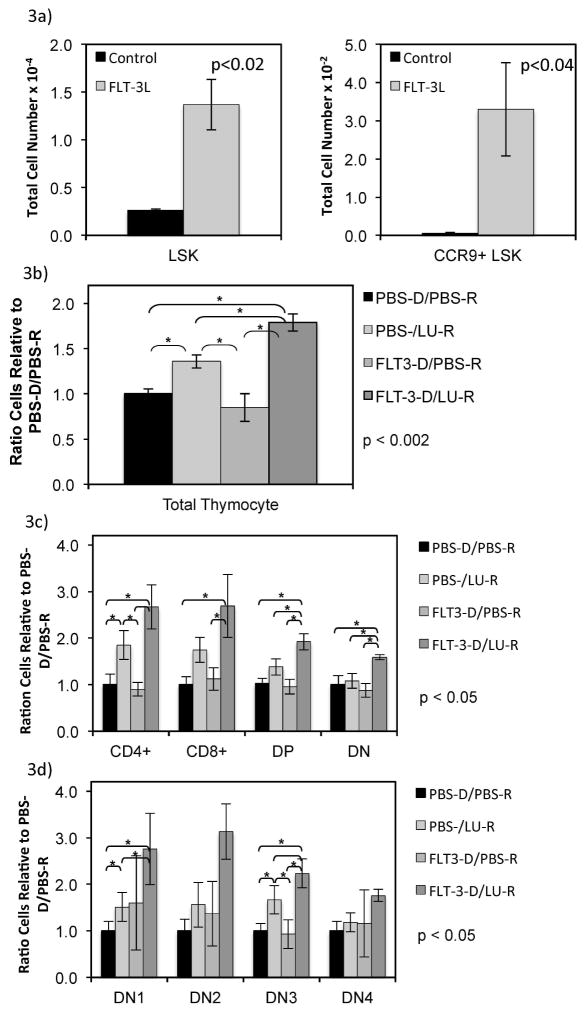

Exogenous FLT3L to the donor enhances thymic reconstitution in hosts who receive Lupron after HSCT

Because ETP are a point of regulation in thymocyte development, we hypothesized that these increased marrow LSK cells (pre-ETP) may have led to enhanced thymic reconstitution in the setting of BMT through expansion of the donor pool. As thymic dysfunction after HSCT occurs more frequently in older individuals, we next studied the impact of FLT3L administration on older mice (greater than 4 months of age). These older mice were used as donors and hosts, receiving a minimum number (1 million) of T cell depleted marrow cells adoptively transferred. LSK cells were increased 5 fold in the donor product after FLT3L treatment with similar enrichment of CCR9+ LSK cells, the population that will exit the marrow to become ETP (Figure 3A) (p<0.02). Following radiation, hosts received Lupron to promote androgen withdrawal that has been shown to increase ETP entry and accelerate thymocyte development20 or PBS control. Thus, if ETP entry is now limited through circulating precursors, FLT3L treatment may lead to improved thymocyte reconstitution as compared to PBS treated hosts with FLT3L treated donors. At 5 weeks post-transplant, thymocyte numbers were significantly higher in the FLT3L treated donors and Lupron-treated host pairs as compared to either agent alone or PBS donor and host controls (p<0.4) (Figure 3B). Interestingly, mice who received FLT3L treated marrow in the absence of androgen withdrawal did not demonstrate higher thymocyte numbers, suggesting that 1 million T cell depleted unmanipulated marrow cells provides sufficient ETP for thymic reconstitution in older mice. As previously shown, Lupron administration alone led to enhanced thymopoeisis as compared to controls, though significantly less than those mice who received the FLT3L treated marrow in addition to Lupron treatment. Total thymocyte numbers for these populations included: Control-donor/Control-host 1.47 e8 (+/− 1.58 e7), Control-donor/Lupron-treated host 1.97 e8 (+/− 6.27 e6), FLT3L treated donor/Control host 1.25 e8 (1.25 e8 +/− 2.25 e7), FLT3L-treated donor/Lupron-host 2.37 e8 (+/−5.04 e6), (p<0.002). Furthermore, the increase in thymocytes with FLT3L treated donors and Lupron treated hosts as compared to PBS treated controls included CD4+ single positive (SP), CD8+ SP, CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), and DN thymocytes (p<0.05) (Figure 3C). While the Lupron-treated groups led to increased SP and DP thymocytes (compared to PBS controls), DN thymocytes total numbers were only increased in the FLT3L donor/Lupron host group (p<0.05) (Figure 3D). Further analysis of the DN populations revealed an increase in DN1 populations in the FLT3L donor/Lupron host group above PBS controls. These data support optimal uptake of thymocytes in mice that received adoptive transfer of FLT3L-treated donor, because these are constrained by the thymic CCL25 availability that also controls thymocyte developmental progression (most critical for progression to DN3 which recapitulates the ratios of the total number of thymocytes for the groups).

Figure 3. Exogenous FLT3L to the donor enhances thymic reconstitution in hosts who receive Lupron after HSCT.

Flow cyometry was used to enumerate marrow LSK cells that expressed CCR9, the pre-ETP population, after 1 week of FLT3L exposure compared to control (A). One million T cell depleted donor bone marrow from C57BL/6 greater than 4 month-old male mice treated with PBS or FLT3L was adoptively transferred into congenic (Ly5.2) aged hosts that received Lupron or PBS one day after radiation. Thymi were recovered at 6 weeks and donor congenic thymocyte populations enumerated using flow cytometry. The ratio of donor total thymocytes (B), thymic subsets (C), and double negative thymocyte subsets (D) in each of the 4 treatment groups is shown compared to control (PBS treated donor transferred to PBS treated recipient (PBS-D/PBS-R); PBS treated donor transferred to Lupron treated recipient (PBS-D/Lu-R); FLT3L treated donor transferred to PBS treated recipient (Flt3-D/PBS-R); FLT3L treated donor transferred to Lupron treated recipient (Flt3-D/Lu-R).

Exogenous FLT3L increases in the spleen secondary to trafficking from marrow

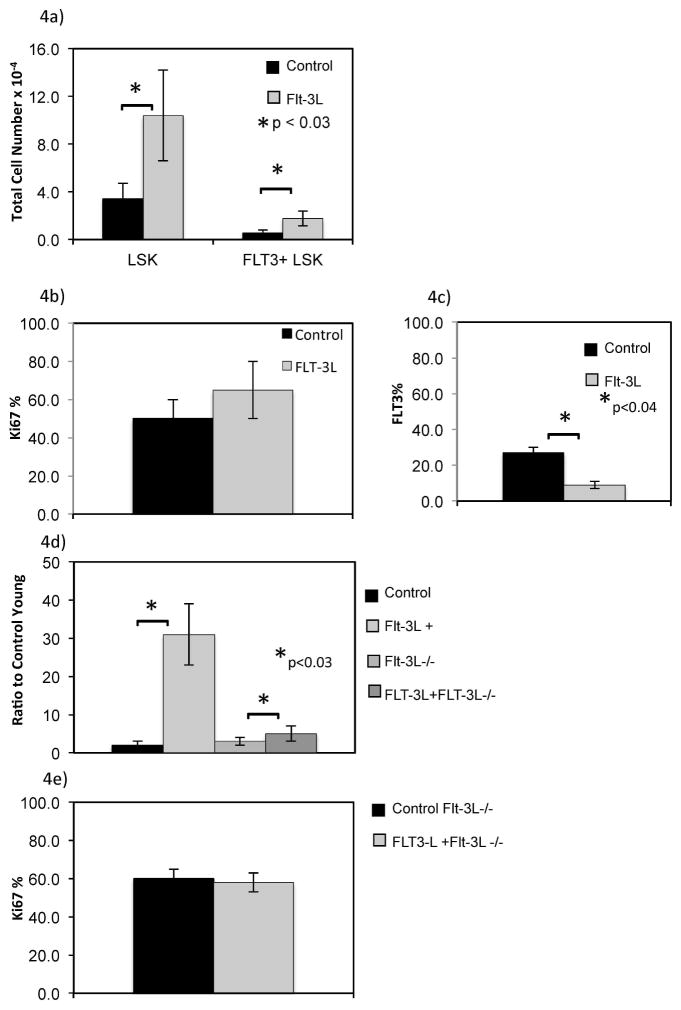

These findings suggested FLT3L might also provide a signal to enhance export of precursors from the marrow, increasing early progenitors available for thymic uptake. After FLT3L administration, splenic LSK cells were dramatically increased by greater than 10 fold, far in excess of that observed in the marrow (4 fold increase or less, p<0.03) (Figure 4A). Splenic FLT3 positive LSK cells were also significantly increased after FLT3L exposure. However, the proportion of splenic FLT3+ LSK Ki-67 positive was unchanged, which suggested that there was not increased proliferation of resident splenic FLT3+ LSK. (Figure 4B). Additionally, similar to marrow studies, FLT3 expression in the spleen was down-regulated, following exposure to the FLT3L cytokine (p<0.04) (Figure 4C). To address the question of whether FLT3L led to trafficking of marrow LSK cells to spleen, we used FLT3LKO mice28 which bear FLT3 receptor but do not have circulating FLT3L, so that the effect of exogenous exposure to FLT3L could be measured as a direct effect in each organ. Following FLT3L administration, splenic LSK cells in FLT3LKO mice increased, the FLT3 receptor expression was down regulated on LSK, without change in Ki-67 proportion (Figure 4D, p<0.04, 4E p non significant). This suggested that FLT3L led to trafficking of FLT3+ LSK from marrow to spleen. If instead the FLT3L was only impacting resident splenic LSK, and leading to increased splenic LSK, Ki-67 of this population should have been increased after exposure. Because the increase in splenic LSK cells in FLT3LKO mice was less than that observed in WT mice after FLT3L administration, this suggested that the level of circulating FLT3L may directly correlate with the number of LSK cells exported from BM to spleen (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Splenic LSK cells are increased in response to FLT3L exposure.

Splenic LSK cells were enumerated using flow cytometry for control and FLT3L treated mice for 1 week in age matched mice (A). Proportion of cells positive for Ki-67 was determined by flow cytometry for young mice (B). FLT3 frequency of splenic LSK cells is shown for young and old mice exposed to FLT3L or control for 1 week. FLT3LKO (FLT3L−/−) and wild type C57BL/6 mice were treated with FLT3L or control for 1 week and flow cytometry was used to enumerate splenic LSK cells proportion FLT3 receptor positive (C), LSK cell ratio to control mice (D), and Ki-67 positive fraction within FLT3L knock out mice with and without FLT3L administration (E).

Exogenous FLT3L increases LSK cells survival not proliferation

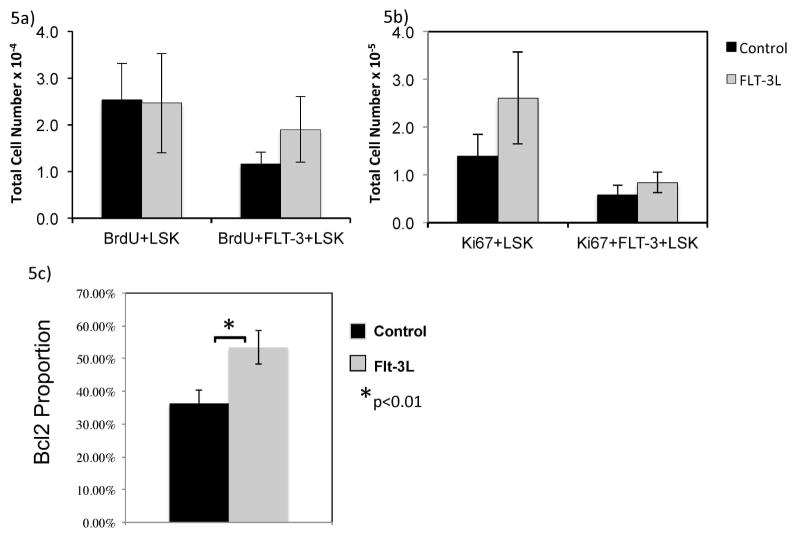

We then performed studies to determine if the increase in LSK cells/ETP was due to proliferation of precursors, enhanced survival, or both. BrdU and Ki-67 studies failed to show a significant increase in proliferation of marrow LSK cells after FLT3L administration (Figure 5A, B). Rather, we show an upregulation of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein following FLT3L administration in LSK cells (p<0.01) (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. FLT3L increases LSK cells survival by increasing Bcl-2.

Marrow LSK cells that had uptake of BrdU (A), or were Ki-67 positive (B) or Bcl-2 (C) were enumerated using flow cytometry after 1 week of control or FLT3L.

FLT3L uses CXCR4 stromal interactions

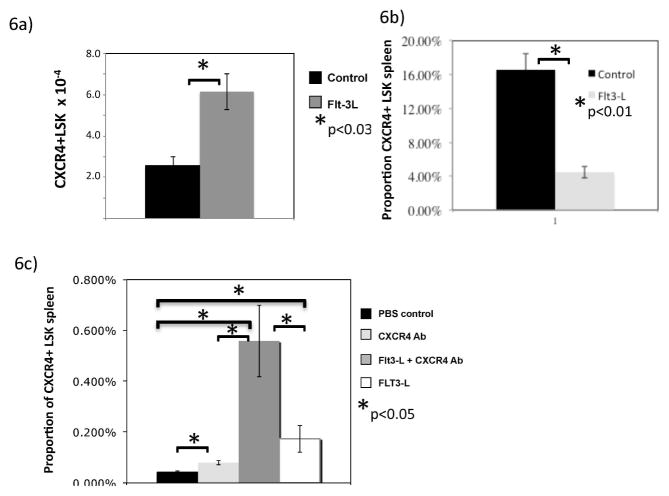

Because FLT3L both mobilized precursors and increased Bcl-2 of marrow LSK cells, we hypothesized that the mechanism underlying these findings involved CXCR4, a receptor critical for marrow stromal residence of stem cells. To explore this, we evaluated CXCR4 expression on marrow and splenic LSK cells. In support of this hypothesis, marrow LSK cells showed an increase in total number of LSK cells that were CXCR4 positive in response to FLT3L exposure (p<0.03, Figure 6A) without altering the proportion expressing CXCR4. In contrast, the proportion of splenic LSK cells expressing CXCR4 was significantly decreased following FLT3L administration (p<0.01, Figure 6B), consistent with trafficking of LSK cells from marrow. Because these data suggested that FLT3L acted through the CXCR4 pathway, we co-administered an anti-CXCR4 antibody to investigate whether these effects could be augmented or abrogated. After FLT3L and anti-CXCR4 antibody co-administration, the marrow LSK cells were increased to a similar extent compared to FLT3L alone (data not shown). However, co-administration of antibody and FLT3L, led to a dramatic increase of splenic LSK cells, far in excess of FLT3L or antibody alone (p<0.05, Figure 6C). Thus, FLT3L augmentation of anti-CXCR4-antibody mediated mobilization, suggests that this is not simply a redundant mechanism of CXCR4 interruption, but an additive effect (likely survival). Furthermore, the lack of an additive effect in the marrow (and lack of an effect of anti-CXCR4 antibody on marrow LSK cells alone) is consistent with a mechanism that involves CXCR4 regulation without mediating effects directly through this receptor.

Figure 6. FLT3L alters CXCR4 expression on LSK cells.

Flow cytometry was used to enumerate CXCR4 positive LSK cells in marrow of FLT3L treated or control mice after 1 week (A). Proportion of CXCR4 positive LSK cells in spleen is shown (B) after 1 week of FLT3L or control exposure. LSK cells were also enumerated after 1 week of exposure to controls or FLT3L or CXCR4 antibody in the spleen (C).

FLT3L drives marrow LSK cells into the marrow stromal niche

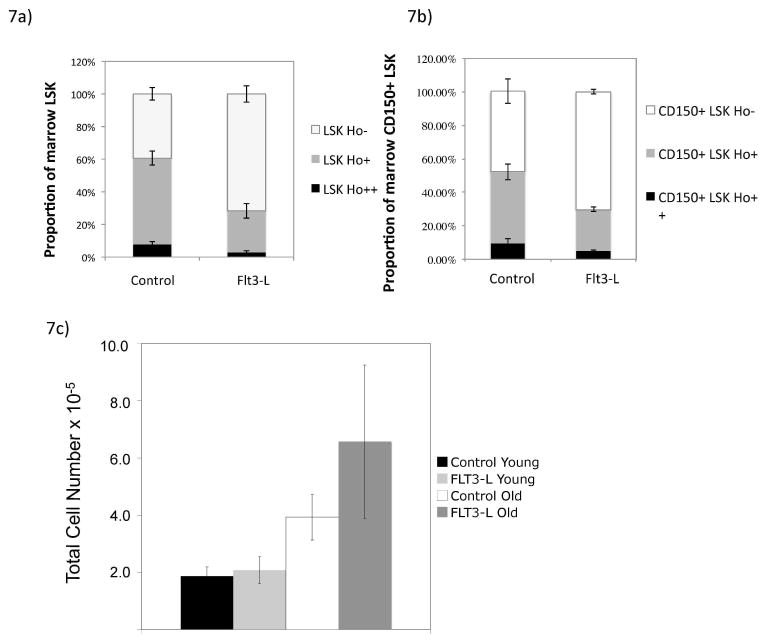

These data led us to hypothesize that FLT3L might lead to increased interaction with the stromal niche. Using Hoechst dye to determine the position of LSK cells in the marrow space35,36, we measured mature and immature LSK cells populations with and without exogenous FLT3L. These mice receive dye at 5 and 10 minutes pre-mortem and then the cells are processed to maintain dye within the cell, thus serving as a surrogate for cellular position within the marrow space. Cells ensconced in the niche are Ho− (not exposed to dye); in contrast, cells in areas of high blood FLT3Low are Ho++, with an intermediate position demonstrated as well (Ho+). After FLT3L exposure, the Ho− proportion of LSK cells was significantly increased, while Ho+ and Ho++ were significantly decreased, p<0.03 for LSK cells Ho++ FLT3L versus control, p<0.001 for LSK cells Ho+ and Ho− FLT3L versus control (Figure 7A). This was also true of the most immature LSK cells, p< 0.004 between CD150 Ho+ FLT3L versus control and p< 0.02 for CD150 Ho− FLT3L versus control (CD150 +) (Figure 7B). Thus, LSK cells exposed to FLT3L upregulate CXCR4, driving them into the stromal niche, providing survival signals, leading to increased total marrow numbers. To account for potential increased stromal cells as a result of FLT3L, we measured the effect of FLT3L on marrow stromal cells (CD45− Ter119−), and showed that these cells were not increased significantly after FLT3L in older or young mice (in the 1 week time frame) (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. LSK cells and Immature LSK cells are enriched in stromal niche after FLT3L administration.

Marrow LSK cells position in the marrow stromal niche was determined using Hoescht dye (Ho), whereby Ho− represent those ensconced within the niche and protected from blood flow, and Ho++ represent those with the highest exposure to blood flow. FLT3L exposure led to increased Ho− (stromal protected) proportion of total LSK cells, p<0.03 for LSK cells Ho++ FLT3L versus control, p<0.001 for LSK cells Ho+ and Ho− FLT3L versus control, (A) and immature CD150+ LSK cells, p< 0.004 between CD150 Ho+ FLT3L versus control and p< 0.02 for CD150 Ho− FLT3L versus control (B). FLT3L exposure did not increase stromal cell (CD45− Ter CD119−) number following extraction and digestion (C).

DISCUSSION

Thymic dysfunction following HSCT has significant clinical consequences. While factors such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy damage have been postulated to contribute to poor thymopoiesis, the hematopoietic constraints on thymic recovery are less well explored. In this manuscript, we set out to uncover how bone marrow precursor restrictions affect thymic renewal.

Previous work had suggested a role for FLT3L in the regulation of thymic function due to increased splenic recent thymic emigrants after FLT3L exposure32. However, the thymi were not examined directly in this work, leaving the question unanswered. Our data demonstrate that FLT3L does not directly regulate thymopoiesis in WT mice under homeostatic conditions in this murine model. Rather, these results would support a trafficking mechanism of naïve T cells to the spleen leading to an increase in recent thymic emigrants without enhanced thymopoiesis, such as has been shown after IL-7 administration37.

Although FLT3L does not enhance thymopoiesis in unmanipulated WT mice, prior publications have shown that FLT3L may enhance thymopoiesis after BMT 26,30,31,38. Our data demonstrate that this enhanced thymopoiesis is secondary to improved progenitor uptake, suggesting FLT3L overcomes the constraint of limiting progenitors to optimize thymus reconstitution. FLT3L co-administration with Lupron led to the greatest increase in thymopoeisis, consistent with the concept that Lupron led to intra-thymic signaling that permitted greater ETP incorporation and FLT3L led to increased circulation of ETP. This was demonstrated through the increase in FLT3+ LSK in peripheral sites and that the greatest increase in thymocytes occurred in the immature (double negative) subset. Notably, we did not administer FLT3L to BMT recipients in these experiments; thus, this mechanism applies only to the donor-exposed to FLT3L. Administration of FLT3L to the donor rather than the host has greater translational potential, overcoming the issue of tumor acceleration by FLT3L in hosts undergoing BMT for high-risk cancers38,39.

We then sought to uncover the mechanism underlying FLT3L increase in thymic progenitors. Because of the paucity of FLT3+LSK cells in peripheral blood, we chose to use the proportion in lymphoid tissues undergoing proliferation to investigate trafficking. First, we show that FLT3L leads to LSK cells and FLT3+ LSK cells egress, increasing splenic LSK cells without proliferation (Ki-67). However, these data could have been due to differences in endogenous production of FLT3L between the marrow and spleen such that the same exogenous dose could have greater effect in a splenic milieu that was relatively devoid of FLT3L. We then obtained FLT3LKO mice40 and demonstrated similar results. While the LSK cells trafficking out of marrow was conserved in this model, the absolute increase in cells in the spleen was less in the KO compared to WT mice. While others had suggested that FLT3L could mobilize stem cells41–43 that could rescue lethally irradiated hosts43,44, these data add to this work and implicate trafficking of cells out of the marrow, and not proliferation of a few LSK cells upon egress, a critical element for its potential use as a mobilizing agent for hematopoietic stem cell donation.

Further, we show an increase in the FLT3+ LSK cells following FLT3L administration, expected given the reduced number of FLT3+ LSK cells in FLT3L knockouts28. However, total LSK cells were not diminished in these mice, suggesting that FLT3L did not affect stem cells as a whole. Increased LSK cells after FLT3L was not related to proliferation, consistent with prior in vitro studies that failed to induce LSK cells proliferation after FLT3L45. Specifically, we show that Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein, is increased in marrow LSK cells following FLT3L exposure. While LSK cells survival has been increased after FLT3L in-vitro21,29, our data suggest in-vivo survival advantage may occur through Bcl-2, though further functional studies would need to be performed to confirm this finding.

Our data also suggested that LSK cells received a survival signal from FLT3L including cells that were FLT3 negative (the more immature subset). Because FLT3L both mobilized precursors and enhanced survival of marrow LSK cells, we hypothesized that the mechanism underlying these findings involved CXCR4, a receptor critical for marrow stromal residence of stem cells. Our data revealed that FLT3L exposure led to increased total number of LSK cells with CXCR4 expression in marrow, while the splenic LSK cells CXCR4 + proportionately decreased. Thus, FLT3L altered CXCR4 expression that directs cellular localization outside the marrow niche (with decreased CXCR4) or inside the marrow compartment (CXCR4 upregulation).

Because FLT3L mediates homing through the CXCR4 pathway, there was evidence that this cytokine led to interactions with the stromal niche. Studies have shown that long term progenitor hematopoietic cells reside mostly within the marrow niche35,36,46–48. Using Hoechst dye to determine the position of LSK cells in the marrow space35,36, we show an increase in LSK cells within stromal niches after FLT3L exposure, which was not due to increased stromal cells. Collectively, our data suggest that FLT3L drives immature LSK cells into stromal niches, consistent with enhanced survival, leading to increased LSK cells. Because of this newly generated surplus of LSK cells or because of differences in niche interactions48, surplus LSK cells may then down-regulate CXCR4 and emigrate to the spleen. Our data further support the hypothesis that the niche is simply saturated, because FLT3LKO mice export fewer LSK cells to spleen after FLT3L exposure and would have more intra-marrow niches available given the prior absence of this signal to drive stem cells to the niche. This is also supported by published data that show that success of mobilization may be due to the length of FLT3L exposure49, in which longer exposure saturates the niche. Thus, FLT3L may regulate HSC renewal and egress, at least in part through stromal interactions with CXCR4, thereby creating a point of thymic regulation only in terms of renewal of the marrow LSK cells/ETP pool.

These data have potential translational implications for hematologists. FLT3L administration to BMT donors may enhance the survival of HSCs and may accelerate engraftment. This may be most relevant to the setting of older donors where others have revealed a relative loss of LSK cells/ETP potential50–52. Further, our data would support a trial to use FLT3L mobilized donors with Lupron to enhance thymopoiesis, and prior data suggest that FLT3L could adequately mobilize hematopoietic progenitors53,54, and supporting synergy between FLT3L and GCSF (the standard mobilizing agent)55. Collectively, these may provide opportunities to enhance thymic recovery, potentially lowering infectious and GVHD risk 56–59. However, because we did not perform these experiments in mice undergoing HSCT, the influence of FLT3-treated donor LSK cells and Lupron-treated hosts on thymic recovery after allogeneic HSCT should be explored in future murine studies.

In summary, these data suggest a mechanism for FLT3L activity on HSC and marrow thymic precursors without direct effects on thymopoiesis. Our data support that this activity involves mobilization of precursors and survival advantage through stromal CXCR4/CXCL12 interactions. These data may have important implications for clinical applications of FLT3L in transplantation and in the biology of FLT3L and its effect on marrow progenitors.

Highlights.

Flt3-ligand administration to donor hematopoietic stem cells enhances thymus reconstitution in Lupron-treated hosts.

Flt3-ligand administration increases hematopoietic stem cell survival coincident with Bcl-2 upregulation.

Flt3-ligand exposure mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells both into the periphery (through CXCR4 downegulation) and into the marrow stromal niche.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Telford for his review of this manuscript. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Funding

This research was funded by the intramural program of the National Cancer Institute, NIH.

Footnotes

Authorship

Contribution: K.M.W., A.M., P.J.L., C.V.B., J.W. performed research. A.M., P.J.L., C.V.B., and K.M.W. analyzed the data. K.M.W. and R.E.G. designed research, wrote and edited the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hakim FT, Memon SA, Cepeda R, et al. Age-dependent incidence, time course, and consequences of thymic renewal in adults. J Clin Invest. 2005 Apr;115(4):930–939. doi: 10.1172/JCI22492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewin SR, Heller G, Zhang L, et al. Direct evidence for new T-cell generation by patients after either T-cell-depleted or unmodified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations. Blood. 2002 Sep 15;100(6):2235–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams KM, Hakim FT, Gress RE. T cell immune reconstitution following lymphodepletion. Seminars in immunology. 2007 Oct;19(5):318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackall CL, Gress RE. Pathways of T-cell regeneration in mice and humans: implications for bone marrow transplantation and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 1997 Jun;157:61–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkman R, Cohen G, Carter SL, et al. Successful immune reconstitution decreases leukemic relapse and improves survival in recipients of unrelated cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006 Sep;12(9):919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King C, Ilic A, Koelsch K, Sarvetnick N. Homeostatic expansion of T cells during immune insufficiency generates autoimmunity. Cell. 2004 Apr 16;117(2):265–277. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordoy T, Husebekk A, Aaberge IS, et al. Humoral immunity to viral and bacterial antigens in lymphoma patients 4–10 years after high-dose therapy with ABMT. Serological responses to revaccinations according to EBMT guidelines. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001 Oct;28(7):681–687. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small TN, Papadopoulos EB, Boulad F, et al. Comparison of immune reconstitution after unrelated and related T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation: effect of patient age and donor leukocyte infusions. Blood. 1999 Jan 15;93(2):467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olkinuora H, Talvensaari K, Kaartinen T, et al. T cell regeneration in pediatric allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007 Feb;39(3):149–156. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen NJ, Viselli SM, Shults K, Stelzer G, Kovacs WJ. Induction of immature thymocyte proliferation after castration of normal male mice. Endocrinology. 1994 Jan;134(1):107–113. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen NJ, Kovacs WJ. Effects of androgens on T and B lymphocyte development. Immunol Res. 2001;23(2–3):281–288. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leposavic G, Karapetrovic B, Obradovic S, Vidiic Dandovic B, Kosec D. Differential effects of gonadectomy on the thymocyte phenotypic profile in male and female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996 May;54(1):269–276. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg GL, Alpdogan O, Muriglan SJ, et al. Enhanced Immune Reconstitution by Sex Steroid Ablation following Allogeneic Hemopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J Immunol. 2007 Jun 1;178(11):7473–7484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heng TS, Goldberg GL, Gray DH, Sutherland JS, Chidgey AP, Boyd RL. Effects of castration on thymocyte development in two different models of thymic involution. J Immunol. 2005 Sep 1;175(5):2982–2993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roden AC, Moser MT, Tri SD, et al. Augmentation of T cell levels and responses induced by androgen deprivation. J Immunol. 2004 Nov 15;173(10):6098–6108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutherland JS, Goldberg GL, Hammett MV, et al. Activation of thymic regeneration in mice and humans following androgen blockade. J Immunol. 2005 Aug 15;175(4):2741–2753. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland JS, Spyroglou L, Muirhead JL, et al. Enhanced Immune System Regeneration in Humans Following Allogeneic or Autologous Hemopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation by Temporary Sex Steroid Blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Feb 15;14(4):1138–1149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg GL, Sutherland JS, Hammet MV, et al. Sex steroid ablation enhances lymphoid recovery following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2005 Dec 15;80(11):1604–1613. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000183962.64777.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnard AL, Chidgey AP, Bernard CC, Boyd RL. Androgen depletion increases the efficacy of bone marrow transplantation in ameliorating experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Blood. 2009 Jan 1;113(1):204–213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams KM, Lucas PJ, Bare CV, et al. CCL25 increases thymopoiesis after androgen withdrawal. Blood. 2008 Oct 15;112(8):3255–3263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veiby OP, Jacobsen FW, Cui L, Lyman SD, Jacobsen SE. The flt3 ligand promotes the survival of primitive hemopoietic progenitor cells with myeloid as well as B lymphoid potential. Suppression of apoptosis and counteraction by TNF-alpha and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 1996 Oct 1;157(7):2953–2960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Felice L, Di Pucchio T, Breccia M, et al. Flt3L enhances the early stem cell compartment after ex vivo amplification of umbilical cord blood CD34+ cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998 Jul;22( Suppl 1):S66–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasko JE, Metcalf D, Rossner MT, Begley CG, Nicola NA. The flt3/flk-2 ligand: receptor distribution and action on murine haemopoietic cell survival and proliferation. Leukemia. 1995 Dec;9(12):2058–2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boiers C, Buza-Vidas N, Jensen CT, et al. Expression and role of FLT3 in regulation of the earliest stage of normal granulocyte-monocyte progenitor development. Blood. 2010 Jun 17;115(24):5061–5068. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buza-Vidas N, Cheng M, Duarte S, Nozad H, Jacobsen SE, Sitnicka E. Crucial role of FLT3 ligand in immune reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation and high-dose chemotherapy. Blood. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):424–432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackarehtschian K, Hardin JD, Moore KA, Boast S, Goff SP, Lemischka IR. Targeted disruption of the flk2/flt3 gene leads to deficiencies in primitive hematopoietic progenitors. Immunity. 1995 Jul;3(1):147–161. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen CT, Kharazi S, Boiers C, et al. FLT3 ligand and not TSLP is the key regulator of IL-7-independent B-1 and B-2 B lymphopoiesis. Blood. 2008 Sep 15;112(6):2297–2304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitnicka E, Buza-Vidas N, Ahlenius H, et al. Critical role of FLT3 ligand in IL-7 receptor independent T lymphopoiesis and regulation of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors. Blood. 2007 Oct 15;110(8):2955–2964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen CT, Boiers C, Kharazi S, et al. Permissive roles of hematopoietin and cytokine tyrosine kinase receptors in early T-cell development. Blood. 2008 Feb 15;111(4):2083–2090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenins L, Gill JW, Boyd RL, Hollander GA, Wodnar-Filipowicz A. Intrathymic expression of Flt3 ligand enhances thymic recovery after irradiation. J Exp Med. 2008 Mar 17;205(3):523–531. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wils EJ, Braakman E, Verjans GM, et al. Flt3 ligand expands lymphoid progenitors prior to recovery of thymopoiesis and accelerates T cell reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 2007 Mar 15;178(6):3551–3557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fry TJ, Sinha M, Milliron M, et al. Flt3 ligand enhances thymic-dependent and thymic-independent immune reconstitution. Blood. 2004 Nov 1;104(9):2794–2800. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swee LK, Bosco N, Malissen B, Ceredig R, Rolink A. Expansion of peripheral naturally occurring T regulatory cells by Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand treatment. Blood. 2009 Jun 18;113(25):6277–6287. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-161026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christopher MJ, Liu F, Hilton MJ, Long F, Link DC. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009 Aug 13;114(7):1331–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkler IG, Barbier V, Wadley R, Zannettino AC, Williams S, Levesque JP. Positioning of bone marrow hematopoietic and stromal cells relative to blood flow in vivo: serially reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells reside in distinct nonperfused niches. Blood. 2010 Jul 22;116(3):375–385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parmar K, Mauch P, Vergilio JA, Sackstein R, Down JD. Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 27;104(13):5431–5436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701152104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu YW, Memon SA, Sharrow SO, et al. Exogenous IL-7 increases recent thymic emigrants in peripheral lymphoid tissue without enhanced thymic function. Blood. 2004 Aug 15;104(4):1110–1119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ailles LE, Gerhard B, Hogge DE. Detection and characterization of primitive malignant and normal progenitors in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia using long-term coculture with supportive feeder layers and cytokines. Blood. 1997 Oct 1;90(7):2555–2564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carow CE, Levenstein M, Kaufmann SH, et al. Expression of the hematopoietic growth factor receptor FLT3 (STK-1/Flk2) in human leukemias. Blood. 1996 Feb 1;87(3):1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKenna HJ, Smith FO, Brasel K, et al. Effects of flt3 ligand on acute myeloid and lymphocytic leukemic blast cells from children. Exp Hematol. 1996 Feb;24(2):378–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashihara E, Shimazaki C, Sudo Y, et al. FLT-3 ligand mobilizes hematopoietic primitive and committed progenitor cells into blood in mice. Eur J Haematol. 1998 Feb;60(2):86–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1998.tb01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasel K, McKenna HJ, Morrissey PJ, et al. Hematologic effects of flt3 ligand in vivo in mice. Blood. 1996 Sep 15;88(6):2004–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudo Y, Shimazaki C, Ashihara E, et al. Synergistic effect of FLT-3 ligand on the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells into blood in mice. Blood. 1997 May 1;89(9):3186–3191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Kruijf EJ, Hagoort H, Velders GA, Fibbe WE, van Pel M. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are differentially mobilized depending on the duration of Flt3-ligand administration. Haematologica. 2010 Jul;95(7):1061–1067. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.016691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyman SD, Jacobsen SE. c-kit ligand and Flt3 ligand: stem/progenitor cell factors with overlapping yet distinct activities. Blood. 1998 Feb 15;91(4):1101–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature. 2006 Jun 29;441(7097):1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010 Aug 12;466(7308):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo Celso C, Fleming HE, Wu JW, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009 Jan 1;457(7225):92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fukuda S, Broxmeyer HE, Pelus LM. Flt3 ligand and the Flt3 receptor regulate hematopoietic cell migration by modulating the SDF-1alpha(CXCL12)/CXCR4 axis. Blood. 2005 Apr 15;105(8):3117–3126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zediak VP, Maillard I, Bhandoola A. Multiple prethymic defects underlie age-related loss of T progenitor competence. Blood. 2007 Aug 15;110(4):1161–1167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-071605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayack SR, Shadrach JL, Kim FS, Wagers AJ. Systemic signals regulate ageing and rejuvenation of blood stem cell niches. Nature. 2010 Jan 28;463(7280):495–500. doi: 10.1038/nature08749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrison SJ, Wandycz AM, Akashi K, Globerson A, Weissman IL. The aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 1996 Sep;2(9):1011–1016. doi: 10.1038/nm0996-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rini BI, Paintal A, Vogelzang NJ, Gajewski TF, Stadler WM. Fl\t-3 ligand and sequential FL/interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic renal carcinoma: clinical and biologic activity. J Immunother. 2002 May-Jun;25(3):269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morse MA, Nair S, Fernandez-Casal M, et al. Preoperative mobilization of circulating dendritic cells by Flt3 ligand administration to patients with metastatic colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Dec 1;18(23):3883–3893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.23.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neipp M, Zorina T, Domenick MA, Exner BG, Ildstad ST. Effect of FLT3 ligand and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on expansion and mobilization of facilitating cells and hematopoietic stem cells in mice: kinetics and repopulating potential. Blood. 1998 Nov 1;92(9):3177–3188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, et al. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996 Nov 1;184(5):1953–1962. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teshima T, Reddy P, Liu C, Williams D, Cooke KR, Ferrara JL. Impaired thymic negative selection causes autoimmune graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2003 Jul 15;102(2):429–435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Belle TL, Juntti T, Liao J, von Herrath MG. Pre-existing autoimmunity determines type 1 diabetes outcome after Flt3-ligand treatment. J Autoimmun. 2010 Jun;34(4):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Keeffe M, Hochrein H, Vremec D, et al. Effects of administration of progenipoietin 1, Flt-3 ligand, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and pegylated granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on dendritic cell subsets in mice. Blood. 2002 Mar 15;99(6):2122–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birg F, Courcoul M, Rosnet O, et al. Expression of the FMS/KIT-like gene FLT3 in human acute leukemias of the myeloid and lymphoid lineages. Blood. 1992 Nov 15;80(10):2584–2593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piacibello W, Fubini L, Sanavio F, et al. Effects of human FLT3 ligand on myeloid leukemia cell growth: heterogeneity in response and synergy with other hematopoietic growth factors. Blood. 1995 Dec 1;86(11):4105–4114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abu-Duhier FM, Goodeve AC, Wilson GA, et al. FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations in adult acute myeloid leukaemia define a high-risk group. Br J Haematol. 2000 Oct;111(1):190–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kharazi S, Mead AJ, Mansour A, et al. Impact of gene dosage, loss of wild-type allele, and FLT3 ligand on Flt3-ITD-induced myeloproliferation. Blood. 2011 Sep 29;118(13):3613–3621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kiyoi H, Naoe T, Nakano Y, et al. Prognostic implication of FLT3 and N-RAS gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1999 May 1;93(9):3074–3080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kondo M, Horibe K, Takahashi Y, et al. Prognostic value of internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene in childhood acute myelogenous leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999 Dec;33(6):525–529. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199912)33:6<525::aid-mpo1>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rombouts EJ, Pavic B, Lowenberg B, Ploemacher RE. Relation between CXCR-4 expression, Flt3 mutations, and unfavorable prognosis of adult acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004 Jul 15;104(2):550–557. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park SH, Chi HS, Min SK, et al. Prognostic significance of the FLT3 ITD mutation in patients with normal-karyotype acute myeloid leukemia in relapse. Korean J Hematol. 2011 Jun;46(2):88–95. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2011.46.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nervi B, Ramirez P, Rettig MP, et al. Chemosensitization of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) following mobilization by the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100. Blood. 2009 Jun 11;113(24):6206–6214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Juarez J, Dela Pena A, Baraz R, et al. CXCR4 antagonists mobilize childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells into the peripheral blood and inhibit engraftment. Leukemia. 2007 Jun;21(6):1249–1257. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobi A, Thieme S, Lehmann R, et al. Impact of CXCR4 inhibition on FLT3-ITD-positive human AML blasts. Exp Hematol. 2010 Mar;38(3):180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spoo AC, Lubbert M, Wierda WG, Burger JA. CXCR4 is a prognostic marker in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):786–791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]