We have an opportunity to revolutionize the way in which we, as a society, think about parenting, in particular the parenting of adolescents.1 We can raise awareness about the importance of parenting during adolescence, we can shift negative perceptions about parenting and adolescence, and we can provide tools for raising healthy teenagers. The power to do so is well within our grasp, and the effects will reverberate throughout our schools, our courts, our workplaces, our neighborhoods, and our lives.

—Rae Simpson, Raising Teens2

INTRODUCTION

The family is the foundational system supporting healthy youth development.2–7 However, similar to a mobile that includes multiple interdependent pieces, even a well-balanced family can become unsteady when 1 piece shifts. To maintain equilibrium, the system must be flexible and adaptable. Given that a fundamental task of adolescence is renegotiation of the relationship between parents and youth, this developmental stage is particularly challenging for parents seeking to maintain balance within their family system. Despite increased understanding of the importance of parents in the lives of youth, and identification of key strategies and approaches that may help parents to guide their child through adolescence, little support is available to parents during this transition.

Parents receive advice and knowledge about optimal parenting strategies from multiple sources when their children are young, often beginning with prenatal classes and continuing through early childhood education. Yet, although health care, social service, and educational systems provide these messages to parents of young children, similar opportunities are not as widely available during adolescence. For example, when the federal government recently invested in Parenting Home Visiting Programs, only 1 of the 7 funded programs included parents of teenagers.8,9 Consequently, parents may be left with 2 impressions: First, that they should not need additional parenting support during their children’s teenage years, and second, that the strategies they used with their younger children remain appropriate for their teens.

The consequences of the lack of information and support for parents of teens are profound. Results of a recent analysis of parenting skills by the Center on Children and Families indicate that these parenting gaps have consequences for social mobility.8 This research found that children of parents with strong parenting skills, including high parental warmth and verbal communication skills, are more likely to succeed in life compared with children whose parents have weaker skills. The authors state, “By the end of adolescence, three out of four children with the strongest parents graduate high school with at least a 2.5 GPA, while avoiding being convicted of a crime or becoming a teen parent. By contrast, only 30% of children with the weakest parents manage to meet these benchmarks.”8(p8) This article presents a clear description of the social benefit of strong parenting skills and identifies the need for interventions focused on building these skills.8

Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to provide needed support and education to parents of teens. Although the gap in parenting support is acknowledged within health care preventive guidelines,10,11 it is not currently being adequately addressed in clinical care or in training for health care providers.12 Nevertheless, there is evidence to support “best practices” for parenting adolescents and there are strategies primary care providers can use to coach parents in making use of these developmentally appropriate parenting practices. These skills and knowledge support parents in maintaining balance within their family system as their children navigate adolescence to ensure a healthy developmental transition for their teens and themselves. Parents are defined through this article as the significant adult exercising that “role” in a teen’s life.

WHY PARENTS AND FAMILY MATTER FOR ADOLESCENTS

Over the last decade, research has reaffirmed that parents play a protective role in the lives of adolescents.3–7 Developmentally, adolescence is a peer-oriented stage; however, parents are much more influential on the lives of their teens than they believe. Youth self-report that their parents affect the decisions they make.13,14 For example, 47% of teens say that parents influence their decisions about sex more than friends, and that teens rely on parents more than anyone else when making important decisions.15 In fact, the positive effects of parents and families on adolescent outcomes are not diminished by the presence of “deviant peers,” suggesting that parents can outweigh the influence of negative peer relations on a teenager’s life.16,17

Given parents’ importance, research has identified sets of attributes and skills that characterize parenting associated with optimal youth health outcomes, and importantly has shown that these parenting behaviors can be developed.18 Four parenting styles have been described based on the levels of control/discipline and emotional nurturance between parents and their children.7

Authoritative: This style is notable for an optimal combination of both high nurturance and discipline. It is referred to as “positive parenting” and it will be explored in more detail.7,18

Authoritarian: This style is defined by high control, but low emotional support and may sometimes be referred to as “dominating.”7,18

Indulgent: This style is described by high nurturance but low control, or lack of monitoring, and may be referred to as “permissive.”7,18

Uninvolved: This style is defined by both low levels of emotional support and low discipline or monitoring and is sometimes referred to as “disengaged.”7,18

Research indicates that children and teens raised in homes in which parents are characterized as authoritative or “positive” show strong health advantages such as the following:

Lower engagement in risky sexual behavior,19

Higher self-esteem, lower incidence of major depression, and fewer suicide attempts,3,23,24

In 2-parent families, the parenting styles may be the same or different.28,29 Although having 2 “positive” parents is associated with the best adolescent outcomes, having ≥1 positive parent in the family can protect an adolescent against the negative consequences of the parenting style of the other parent.28

Key parenting practices contributing to healthy adolescent behaviors include supervision and monitoring, communication of family values and expectations, and consistent discipline methods.30,31 Age-appropriate parental monitoring of adolescents’ whereabouts also protects against risky health behaviors.26,32,33 Successful monitoring is an interactive process that depends on youth disclosure and parents’ appropriate solicitation of information; it depends on the quality of the parent– youth relationship within the larger family context.32,33

Positive qualities of relationships (eg, warmth, support, acceptance, attachment) are not static. They can be bolstered through education and skills building, ultimately protecting adolescents against risky behaviors.3,20,30 Adolescent development is best supported by a family and home environment that is both flexible and appropriately cohesive.34 Flexible families are open to new challenges, interpretations, and ideas, and find ways to adjust during the transitions of adolescence; less flexible families find transitions and adapting to change more challenging.34,35 Healthy levels of family cohesion promote the emotional support that enables individuals or family relationships to remain resilient through challenges. Families at the extremes of cohesiveness may not adequately nurture adolescent transition to adulthood. At 1 extreme, families who are too cohesive may become so enmeshed that it becomes difficult for the adolescent to go through the normal process of individualization.34–38 At the other extreme, families with low cohesion may be so individualized, there is little emotional involvement and support.34,35

Achieving adolescent health-promoting parenting practices and family interactions is challenging, especially in the context with high levels of stress (eg, families with low economic resources facing immigration challenges) and/or low family support (eg, single parents). Parents who are able to utilize positive parenting skills likely have high self-efficacy related to parenting practices. Parenting self-efficacy, defined as a parents’ personal belief that he or she can appropriately raise a child, has an important influence on adolescent development.39 Parenting adolescents per se can generate stress that undermines parenting efficacy for many.40 Therefore, primary care providers can support and empathize with parents of adolescents to increase parenting efficacy and contribute to positive outcomes in both the teens’ and parents’ lives.41

How Do Community and Neighborhood Factors Affect Parenting Practices and Ultimately Adolescent Health?

There is a growing body of evidence regarding environmental factors that influence healthy adolescent development. These social determinants of health may include poverty, poor housing stock, unsafe neighborhoods, ineffective schools, lack of employment, recent immigration, and language barriers.42,43 There is clear evidence that neighborhood safety has both direct and indirect effects on adolescent health outcomes44; therefore, parenting strategies need be sensitive to these environmental circumstances. Teens in unsafe settings need stricter, more intense monitoring than is necessary in other neighborhoods; parents may be challenged by incorporating these more restrictive guidelines into positive parenting practices.44 Under these conditions, it is best to encourage youth participation in supervised programming (like after school activities), where teens can develop social connections with peers in a safe way, in addition to have interventions that address multiple areas of family functioning, including emotional support.45

Negative social determinants of health contribute to disparities in health outcomes and create significant challenges for primary care providers seeking to optimize health for all adolescent patients.42,43 Families experiencing negative social determinants of health often have trouble accessing support to address their unmet needs.46 These environmental stressors may have a direct effect on adolescent outcomes and on parenting efficacy.45,47,48 Parenting efficacy deterred by these factors can be strengthened by creating supportive relationships with other family members, friends and supportive professionals, and by developing strong cultural and community bonds.47,48

Addressing these challenges requires a health care system more attuned to assessing and addressing the ecological contributors to health.49 A recent Institute of Medicine (IOM)12 report on gaps in adolescent care delivery called for a focus on the needs of vulnerable adolescents and clearly articulated the need to integrate family-centered approaches into primary care for adolescents. Understanding the impact of these environmental factors on both parents and teens is crucial for providers to support family-centered care.49

OPTIMIZING PRIMARY CARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF ADOLESCENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES

The Current Status

The 2009 IOM report and several national guidelines highlight the need for a new approach within our health system that provides family-centered care to adolescents to optimize health outcomes.12 Both the American Medical Association through the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services and the American Academy of Pediatrics, through “Bright Futures,” state that parents should receive health guidance on parenting behaviors that promote healthy adolescent adjustment at least once during early, middle, and late adolescence.10,11

Although delivering education, anticipatory guidance, and support to parents of adolescents is an established standard of care, there are currently several system-level dilemmas to consider regarding translating these recommendations into practice.

Dilemma #1: How Can Health Care Delivery Systems Be Organized to Integrate Families into Adolescent Care?

Although the last IOM report in Adolescent Health Care reflected a general consensus that our primary care delivery system is not currently structured to allow easy integration of families into adolescent care delivery,12 a number of innovative approaches are emerging that successfully provide high-quality care that supports youth within their family systems. One promising but currently underutilized model is the Patient-Centered Medical Home. The Patient-Centered Medical Home model is well-suited to providing comprehensive adolescent care using an ecological approach50 by providing the needed time, personnel, and reimbursement to financially compensate for the intensity of this type of care delivery. The newer model, Health Home, allows more comprehensive preventive measures, other services, and a bundle of payment that is well-suited for family-centered interventions.51

Dilemma #2: How Can Primary Care Providers Effectively Assess the Health of the Family and Strength of Parenting Practices?

When assessing an adolescent, standard guidelines recommend having separate time both for the teen and the family, and using well-established questionnaires such as those provided in Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services and Bright Futures to guide the interaction.10,11 Links to these questionnaires are presented in Table 1. This provide the parent and the teen with confidentiality.

Table 1.

Links to the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) and Bright Futures Parent and Youth Questionnaires

Data from Elster AB, Kuznets NJ. Guidelines for adolescent preventive services. Baltimore (MD): American Medical Association; 1994; and Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008.

A complete family assessment is indicated when the concerns presented by an adolescent relate to difficult family situations. Examples may include mental or behavioral problems, chronic illness, or situations when the adolescent’s actions affect other family members. Important areas to explore during a family assessment of an adolescent and questions targeting these topics are presented in Box 1. These questions are designed to assist primary care providers in identifying problems in family relations. Greater issues across the areas indicate need for referral to family therapy.

Box 1. Dimensions of a family assessment and associated questions.

Family Cohesion and Support

Do you have a close (or distant) relationship with your parents and siblings? Can you give me examples of a situation where you have felt in close contact with them?

Do you feel supported by your family? Why or why not? How?

Family Adaptability and Flexibility

How do you react when something does not result as you had planned?

How does your family react when something does not result as you had planned?

Can you give me an example of something that has been challenging for your family? How did they react?

What have you tried to address this situation?

Family Communication and Conflict Resolution Strategies

Could you tell me how you solved a recent problem that you had with your family? (Make sure that they provide a detailed description of the situation, including who said what, how the other responded, how the conflict was solved, and how they felt after the situation)

Parental Supervision and Monitoring

How do you make sure where and with whom your child is when s/he is not at home?

How do you know what your child is doing when s/he is not at home?

External Resources

Have you shared your concerns about your child with others? If so, with whom?

Do you have other family members or friends to ask for advice and support?

Are you in touch with your child’s school teachers?

Do you attend religious services? If so, do you know people at your place of worship?

Dilemma #3: What Information Should Providers Share with Parents Regarding Parenting an Adolescent?

Health care providers can be good references for parenting advice beyond the preschool years. Key information for parents to effectively guide their children during adolescence includes the following:

Adolescence is a transition toward independence. Some parents are not aware that this process is a normal part of child development, and may feel threatened by their child’s new behaviors.2

- You can be an effective parent. Parenting efficacy may be evaluated by asking, “On a scale of 1 to 10, how effective do you think you could be in parenting your teen?” Be prepared for parents coping with high levels of stress in their own lives. By respectfully listening, validating their concerns, and helping them to reflect on their strengths, a clinician can increase parenting self-efficacy. Useful resources to guide parents on how to improve their communication with their child include:

- Shoulder to Shoulder parents brochure, downloadable at http://www.hcmc.org/services/AquiParaTiHereforYou/APTTeenParentResources/index.htm,

- A Parent’s Guide to Surviving the Teen Years, available at http://kidshealth.org/parent/growth/growing/adolescence.html, and

- Communicating with Your Teen, available at http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/5000/pdf/5158.pdf.

Become your teen’s “COACH.” Parents need to adjust their parenting practices to meet their children at this new phase of development. One model is the COACH system (Box 2). Acting as a coach for their teen, parents can focus on guiding their children toward independence and creating opportunities for them in ways that prepares them for the challenges of becoming an adult. At the same time, parents can gain a different perspective. By asking themselves, “How would I react if I were his coach instead of his parent?”, parents can focus on their child’s behaviors, rather than in their interpretation of what their child is doing.

- Be a good communicator. Parents need to master effective parent–youth communication and successful conflict resolution strategies (see links to previous parent– youth communication resources):

- Parents should be reminded that an adolescent’s willingness to communicate with them is highly influenced by their ability to establish a context where youth feel free to share.12 Importantly, this does not mean that parents need to agree with their children, but rather that parents should convey that they are willing to listen to them and will treat their opinions with respect.

- Clinicians can help to improve parents’ communication skills by explaining to them and role modeling what providers know about the basics of motivational interviewing, including skills of active listening, rolling with resistance, and the concept of empathy.52

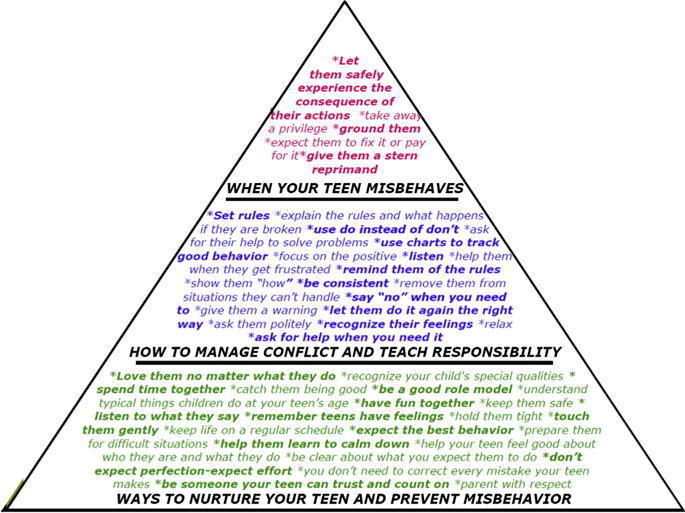

Positive parenting works. Parents need to understand that positive parenting works because it creates an emotional context where kids are more open about their opinions and experiences.53 In the 2001 article “Raising Teens,” Simpson identified the 5 key parenting tasks that are crucial in children’s teen years (see summary of core content of the report in Table 2).2 The Positive Parenting Pyramid, developed by Rose Allen, former parent educator at the University of Minnesota Extension Service, is an example of a tool that can help to convey how parents can direct teen behavior through establishing foundational relationships and parenting practices (Fig. 1).54

Box 2. COACH strategies to facilitate changes in parenting styles.

C reate confidence

O bserve

A dvise

C almly let them “play”- experience life

H elp them debrief those experiences

Table 2.

Basic tasks for parents and strategies to promote them

| Task for Parents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Love and Connect | 2. Monitor And Observe | 3. Guide and Limit | 4. Model and Consult | 5. Provide and Advocate |

| Description | ||||

| Teens need parents to develop and maintain a relationship with them that offers support and acceptance while accommodating the teen’s increasing maturity. | Through a process that involves less supervision and more communication, observation, and networking with other adults, teens need parents who are aware of and let teens know they are aware of their activities, including school performance, work experiences, after-school activities, peer relationships, adult relationships. | Teens need parents to uphold a clear but evolving set of boundaries that maintain important family rules and values but also encourage increased competence and maturity. | Teens need parents to provide ongoing information and support about decision making, values, skills, goals, and interpreting and navigating the larger world by teaching through example and ongoing dialogue. | Teens need parents to not only provide adequate nutrition, clothing, shelter and health care but also a supportive home environment and a network of caring adults. |

| Strategies for Parents | ||||

| Watch for moments to show affection | Keep track of your teen’s whereabouts: WHO they hang out with WHAT they are doing WHERE they are WHEN they will be home | Maintain family rules | Set a good example | Network within the community |

| Acknowledge good times | Keep in touch with other adults | Communicate expectations | Express personal positions | Make informed decisions about school |

| Expect increased criticism from your teen | Involve yourself in school events | Choose your battles | Model the kind of adult relationships you would like your teens to have | Make similarly informed decisions about extracurricular activities |

| Spend time simply listening to your teen | Stay informed about your teens’ progress | Use discipline as a goal | Answer teens’ questions in ways that are truthful. | Arrange or advocate for preventative health care |

| Treat each teen as a unique individual | Learn and watch for warning signs | Restrict punishment | Maintain or establish traditions | Identify people and programs to support and inform you as a parent |

| Appreciate and Acknowledge your teen | Seek guidance if you have concerns | Renegotiate responsibilities and privileges | Support your teen’s education and vocational training | |

| Provide meaningful roles for teen in the family | Monitor your teen’s experience | Help your teen get information | ||

| Spend time together | Evaluate the level of change | Give teens opportunities to practice reasoning and decision-making. | ||

| Key Messages for Parents | ||||

| Most things about their children’s world are changing, but don’t let your love be one of them. | Monitor your teen’s activities because you still can, and it still counts. | Loosen up, but don’t let go. | Parents still matter in the teen years and teens still care. | You can’t control your teen’s world, but you can add to and subtract from it. |

Data from Simpson AR. Raising Teens: a synthesis of research and a foundation for action. Boston (MA): Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health; 2001. Available at: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/chc/parenting-project/.

Fig. 1.

Teen parenting pyramid. (From University of Minnesota Extension Service. Positive parenting of teens: a video-based parent education curriculum. St. Paul (MN): University of Minnesota Extension; 1999.)

Dilemma #4: Can a Clinic Be Youth Friendly and Family Oriented? The Challenge of Confidentiality

Confidentiality is a key aspect of adolescent care delivery. A challenge to integrating parents into adolescent care is navigating confidentiality. Evidence suggests that talking or explaining to parents why teens have the right to confidential care can change the predisposition of 30% of the parents.55 Thus, explaining to parents why confidentiality is important for teenagers is fundamental. It is also important to offer an intimate space for the parent, and to convey that the provider is also available to support and coach them while they adapt their parenting styles to the new needs of their child’s adolescence.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Lessons Learned from a Case Study of a Family-Oriented, Youth-Friendly Primary Care Clinic: The Aquí Para Ti (APT) Experience

Aquí Para Ti (APT) is a comprehensive, clinic-based, healthy youth development program that provides medical care, coaching, health education, and referrals for Latino youth (all gender) ages 10 to 24 as well as their families in Minneapolis, Minnesota. APT has been at the forefront of health care service delivery innovation for adolescents since it was founded in 2002. Although it was developed for Latino youth, the overarching model is suitable for other ethnic groups. APT addresses positive youth development, health equity, social determinants of health, and family centeredness. The APT model fulfills all the IOM recommendations to improve Adolescent Care (Table 3). This multi–award-winning program is currently leading the way in defining best practices for behaviorally appropriate health care homes, has been favorably reviewed by agencies assessing health care improvements, and has been named an innovative program to address health disparities by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Health Care Innovations Exchange Program and identified as an Innovative approach to Adolescent Health by the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM). Aqui Para Ti is partially funded by the Eliminating Health Disparities Initiatives Grants (EHDI), from Minnesota Department of Health. Aqui Para Ti was officially certified as a Health Care Home in 2010 by the MN State Certification.

Table 3.

Description of how Aqui para Ti (APT) addresses the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) Adolescent Health Services Delivery Recommendations

| IOM Recommendations | APT Innovations & Examples |

|---|---|

| Focus on the needs of vulnerable adolescents including immigrant populations | Delivers appropriate care for Latino youth and families

|

| Providers must build trust & open communication with adolescents | Provides adolescent-friendly care

|

| Define & train WHAT? to adolescent care competencies | Utilizes an adolescent-focused interdisciplinary team whose members either have skills or experience working with youth or are trained in a defined set of competencies |

| Prevention, health promotion, and behavioral health should be routine | Utilizes appropriate, standard, screening tools and modularized coaching approaches for health behavior, mental health, and health promoting factors |

| Protect confidentiality | Assures family-friendly approach to confidentiality |

| Develop coordinated, linked, & interdisciplinary services for behavioral, reproductive, and mental health | Utilizes case management to coordinate across the health care system and with community resources by:

|

| Adolescents should have access to care | Screens all youth and families regarding ability to access services & address barriers to care through case management |

Data from National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Adolescent Health Services: Missing Opportunities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009.

Model of care

The main features of APT include the following.

Parallel family care: This approach protects youth privacy in a family-centered manner. Family members work together to support the healthy youth development of the child. The approach also honors familism (a key Latino value that stresses strong family connections and cohesion) and builds family strengths and skills by addressing parents’ mental health and parenting needs.

Culturally inclusive: APT included key Latino values in the design of the program, and created a bilingual, bicultural team that represents, celebrates, and appreciates the community they serve. Cultural concordance, defined by the IOM as a cultural match between those delivering an intervention and the target population,12 has shown to improve patient outcomes owing to improved communication, patient satisfaction, adherence to recommendations, and increased self-efficacy owing to identification with the team as role models who reinforce a positive sense of ethnic identity.56

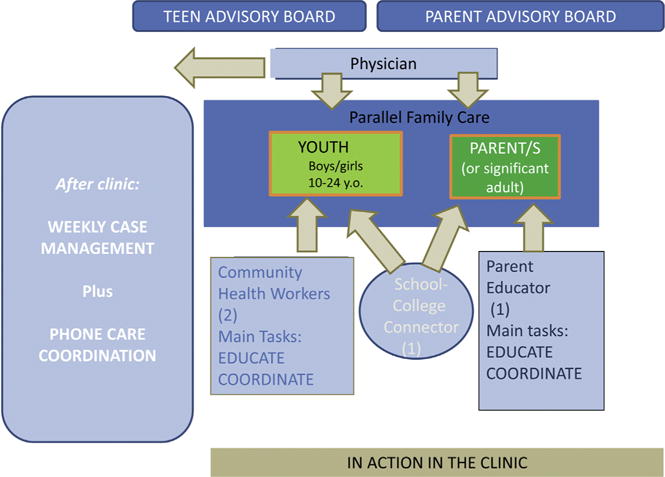

Multidisciplinary team: The special developmental needs of adolescents and their families require diverse talents and skill sets. The clinical team is composed of a family physician, 2 care coordinators/health educators, a school/college connector, and a parent educator. The program has an overall Program Coordinator to manage grants and evaluation, staff, and extra clinical activities. This team creates and sustains connections by simultaneously tackling chronic social, mental, and medical conditions and providing holistic care in 1 location (Fig. 2).

Healthy youth development: The team promotes internal assets and external supports using motivational interviewing techniques52 to record the adolescent’s and parent/guardian’s goals, perspectives, and readiness to change.57

Dual approach: Prevention–intervention: By fulfilling unmet social, mental, and medical health needs, and building on the existing strengths of the individuals and their families, the team addresses the needs of vulnerable families, and improves health equity.

Fig. 2.

Aqui Para Ti “Action in clinic” map.

APT clinical processes

APT functions as a “clinic within a clinic,” delivering care during 3 half-day sessions per week and discussing case management as a team during another half-day session per week. Each care session has between 6 and 8 teens, including 2 new teens per session. Teens or parents can come alone or together. Each initial session begins with a pre-planning huddle where the whole team meets to plan the care for the patients to be seen in that specific session (included new patients). Patient visits last 20 to 30 minutes and usually both the teen and his or her parents attend. During the first visit, parents and youth fill out standardized screening questionnaires.10 Clinical processes include the following steps.

Prepare parents for this process by explaining to them that confidentiality is not meant to contradict or hinder their parenting, rather but to support them. Importantly, this should be done while both the parent and teen are present. The APT team has developed a bilingual English and Spanish document, the “Confidentiality Mantra,” that addresses this topic. A copy of the Mantra is available at: http://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/whatresearch_final.pdf.

Screen parents and teens. After reading the “Confidentiality Mantra,” separate teens and parents and screen them for mood disorders using both the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services questionnaire10 and the Beck Inventory,58 for screening of depression, on their first visit. Parents are also screened for parenting efficacy and parenting styles on either their second or third visit. Parent and youth complete the questionnaires before the clinical encounter, in separate rooms, to maintain confidentiality.

Assess areas of concern for the youth, parents, and provider, which should be organized around the youth’s well-being.

Counsel youth and parents to help them better understand their health problems by having them work together to prioritize them according to both the teen and family needs.

Coach youth and parents by providing them with information, skills, and tools through brief modules based on semistructured scripts and delivered to them by either by one of the team’s member.

Connect the family with culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health and social services, provide them with referrals to address any unmet needs, and foster personal growth and community connection through different activities.

Coordinate the entire plan through weekly case management sessions. In case management, the team designs care plans for new families, taking into consideration the self-identified goals from their visit, determines a risk and need level, and reviews progress for established patients. Care coordination by phone is a crucial element to support the families’ success. Families and teens are instructed to call the Program’s phone line for troubleshooting problems, make appointments, get transferred to the clinic’ nurse if needed, etc. The whole team coordinates 8 AM to 5 PM phone coverage to support their patients’ needs during the week. After hours call and weekends are handled by the Clinic ON-Call Physician system.

Using this approach, APT has achieved positive results in teen’s overall well-being, mental health, and sexual health. The team tested the model of care with random teen interviews and focus groups with parents. In this evaluation, both parents and youth reported that the APT model was useful to their needs. More information about the APT program and its outcomes is available at http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id52784.

How to Translate the Aqui Para Ti Framework into Your Practice

For providers hoping to move toward a more family-centered approach to adolescent care delivery, the following points are some practical first steps to consider.

Before the clinical visit

Identify passionate allies in the clinic that can collaborate with you to build a family-centered adolescent care system. Identify interprofessional staff, including social workers, nurses, and health educators, to work with you to conduct a parallel family visit. If other professionals are not available, make appointments with parents for parenting coaching visits. A30-minute visit can be charged under parenting ICD codes such as “parenting problem” or “parenting stress” on the child’s or the parent’s insurance. It could be charged under the child’s insurance if the teen is present in the clinic, even if the provider spends most of the visit talking only to the parent. The model can be certified as a Patient Centered Medical Home,50 or as the newer Health Home Model.51

Find allies outside the clinic: Identify specialists and community agencies that understand the model of care and can complement the approach. Ask internal allies to help identify key individuals at these agencies who can brief your organization about who they are and what they do, and serve as your point person for referrals.

Anticipate the practice’s needs: It is helpful to have handouts with information that you can give to the parents of teens. Examples of a toolkit can be found on the APT website (see above).

Within the clinical visit

Explain confidentiality to parents and youth together as soon as possible during the visit, and establish that this is the way clinicians work with all teens and families. Inform them that this approach allows both teens and parents to receive support from clinicians (or providers).

Ideally, assess parents and youth at the same time but in separate rooms using well-established screening questionnaires.10,11 Providers should review the questionnaire responses and meet with the parent for ≥5 minutes during the initial visit, and then make a plan for follow-up.

When providers talk, parents and youth listen. Parents can feel threatened and judged by someone talking to their teens alone. Use motivational interviewing skills when assessing parents.52 Importantly, parents and families need to be met where they are, and need to feel welcomed and listened to by their health care providers. Keep in mind that, to provide optimal care for youth, both parents and adolescents need to be the targets of your care and compassion to the same degree.

- First, do not harm. If clinicians are encouraging parents and their teen to discuss a problem together, help them to set ground rules to ensure that the conversation is safe and useful for everyone:

- Constructive comments only

- Active listening

- No name calling allowed

- No embarrassing stories

If a teen comes for a visit alone, assess the parent and adolescent relationship and encourage them to tell parents what they talked about during that appointment. For example, say “The fact that I am not going to tell your parents does not mean that you shouldn’t.” Remember that it is possible to provide family-centered care even when working with only 1 family member.

SUMMARY

There is an increased recognition for the need to create approaches to care delivery for adolescents that are both family centered and youth friendly to improve youth and family outcomes.10–12

Primary care providers are in a unique position to strengthen and support parents by delivering evidence-based messages regarding best practices for parenting adolescents. Providers can help parents to successfully maintain balance for themselves and their family by providing empathy, guidance, and support during the sometimes stressful transition of adolescence. Working on parenting is a leverage point in the community; it creates the social capital to raise other children in the household in a positive way and it creates mentors in our neighborhoods who can provide support for other parents and teens in the community.

With intentional planning, providers can become proficient in coaching parents, and foster positive outcomes by working in an integrated, family-centered manner. This article includes guidelines and recommendations that can increase primary care provider’s skills and self-efficacy in delivering family-centered adolescent care, while highlighting why adolescent service delivery is a critical priority for primary care.

KEY POINTS.

Parental involvement during adolescence is important; however, parents may not recognize that the parenting skills that help teens thrive are different from those they learned for their young children.

Parenting stress during the teen years can be high, even if there are no other stressors in the family.

Primary care providers are perfectly positioned to partner with parents, and support them in mastering parenting skills that support healthy youth development.

Family-centered care does not hinder teens’ right and access to confidential care.

Families need to be supported in the context of their communities and their cultures, considering both their strengths and challenges.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Aqui Para Ti/ Here For you is partially funded by the Eliminating Health Disparities Initiative (EHDI), from the Minnesota Department of Health.

References

- 1.D’Angelo SL, Omar HA. Parenting adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2003;15:11–9. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2003.15.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson AR. Raising Teens: a synthesis of research and a foundation for action. Boston (MA): Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health; 2001. Available at: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/chc/parenting-project/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick MD, Harris LJ, Blum RW. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29(Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youngblade LM, Theokas C, Schulenberg J, et al. Risk and promotive factors in families, schools, and communities: a contextual model of positive youth development in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2007;119(S1):S47–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum RW. Improving the health of youth: a community health perspective. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:254–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg L. We know some things: parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J Res Adolesc. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rees RV, Howard K. The parenting gap. Washington, DC: Center on Children and Families at Brookings Institution; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development. Great transitions: preparing adolescents for a new century. New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elster AB, Kuznets NJ. Guidelines for adolescent preventive services. Baltimore (MD): American Medical Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Adolescent health services: missing opportunities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins WA. Parents’ cognitions and developmental changes in relationships during adolescence. In: Sigel IE, McGillicuddy-DeLisi A, Goodnow JJ, editors. Parental belief systems: the psychological consequences for children. 2nd. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 175–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blum RW. Positive youth development: reducing risk, and improving health. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert B. With one voice 2007: America’s adults and teens sound off about teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, Dishion TJ. Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: an 11-year prospective analysis. Addict Behav. 2012;37:1314–24. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trudeau L, Mason WA, Randall GK, et al. Effects of parenting and deviant peers on early to mid-adolescent conduct problems. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:1249–64. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9648-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, et al. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev. 1992;63:1266–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen M, Svetaz MV, Hardeman R, et al. What research tells us about Latino parenting practices and their relationship to youth sexual behavior. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, et al. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:202–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cislak A, Safron M, Pratt M, et al. Family-related predictors of body weight and weight-related behaviours among children and adolescents: a systematic umbrella review. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:321–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berge JM, Saelens BE. Familial influences on adolescents’ eating and physical activity behaviors. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2012;23:424–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark MS, Jansen KL, Cloy JA. Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:442–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhatia SK, Bhatia SC. Childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Demaray MK. Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:47–61. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, et al. Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68:1084–104. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung HL, Steinberg L. Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance, and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:319–31. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simons GL, Conger R. Linking mother–father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes. J Fam Issues. 2007;28:212–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKinney C, Renk K. Differential parenting between mothers and fathers implications for late adolescents. J Fam Issues. 2008;29:806–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. Am Psychol. 2003;56:457–65. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. The national cross-site evaluation of high risk youth programs: final report. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: further support for a reinterpretation of goring. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:366–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000;71:1072–85. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olson DH, Russell CS, Sprenkle DH. Circumplex model: systemic assessment and treatment of families. Binghamton (NY): The Haworth Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scabini E, Manzi C. Family processes and identity. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 565–84. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunha AI, Relvas AP, Soares I. Anorexia nervosa and family relationships: perceived family functioning, coping strategies, beliefs, and attachment to parents and peers. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2009;9:229–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayseless O, Scharf M. Too close for comfort: inadequate boundaries with parents and individuation in late adolescent girls. Am J Orthop. 2009;79:191–202. doi: 10.1037/a0015623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Parsai M, et al. Cohesion and conflict: family influences on adolescent alcohol use in immigrant Latino families. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2009;8:400–12. doi: 10.1080/15332640903327526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shumow L, Lomax R. Parental efficacy: predictor of parenting behavior and adolescent outcomes. Parenting: Science Practice. 2002;2:127–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman PK, Karraker KH. Self-efficacy and parenting quality: findings and future applications. Dev Rev. 1997;18:47–85. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Small SA, Eastman G. Rearing adolescents in contemporary society: a conceptual framework for understanding the responsibilities and needs of parents. Fam Relat. 1991;40:455–62. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379:1641–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379:1630–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, et al. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: a multilevel analysis. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;31:35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, et al. Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:436–57. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. 2nd. Oxford (England): Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clinton M, Lunney P, Edwards H, et al. Perceived social support and community adaptation in schizophrenia. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:955–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.t01-1-00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Izzo C, Weiss L, Shanahan T, et al. Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children’s socio-emotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2000;20:197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barkley L, Kodjo C, West KJ, et al. Promoting equity and reducing health disparities among racially/ethnically diverse adolescents: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:e804–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker I, McManus MA, Fox HB. Medical home innovations: where do adolescents fit? The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health; Dec, 2011. (Report number (7)). Available at: http://www.thenationalalliance.org/pdfs/Report7.%20Medical%20Home%20Innovations.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014 Available at: http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Long-Term-Services-and-Support/Integrating-Care/Health-Homes/Health-Homes.html. Accessed March 28, 2014. [PubMed]

- 52.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. New York: Guilford Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinberg L. The family at adolescence: transition and transformation. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:170–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.University of Minnesota Extension Service. Positive parenting of teens: a video-based parent education curriculum. St. Paul (MN): University of Minnesota Extension; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hutchinson JW, Stafford EM. Changing parental opinions about teen privacy through education. Pediatrics. 2005;116:966–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper LA, Powe NR. Disparities in patient experiences, healthcare processes, and outcomes: the role of patient-provider racial, ethnic and language concordance. New York: The Commonwealth Fund (Publication #753); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rubak S, Sandbæk A, Lauritzen T, et al. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:305–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]