Abstract

Background:

Staphylococcus aureus has the ability to form biofilms on any niches, a key pathogenic factor of this organism and this phenomenon is directly related to the concentration of NADPH. The formation of NADP is catalyzed by NAD kinase (NADK) and this gene of S. aureus ATCC 12600 was cloned, sequenced, expressed and characterized.

Materials and Methods:

The NADK gene was polymerase chain reaction amplified from the chromosomal DNA of S. aureus ATCC 12600 and cloned in pQE 30 vector, sequenced and expressed in Escherichia coli DH5α. The pure protein was obtained by passing through nickel metal chelate agarose column. The enzyme kinetics of the enzyme and biofilm assay of the S. aureus was carried out in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The kinetics was further confirmed by the ability of the substrates to dock to the NADK structure.

Results:

The recombinant NADK exhibited single band with a molecular weight of 31kDa in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and the gene sequence (GenBank: JN645814) revealed presence of only one kind of NADK in all S. aureus strains. The enzyme exhibited very high affinity for NAD compared to adenosine triphosphate concurring with the docking results. A root-mean-square deviation value 14.039Å observed when NADK structure was superimposed with its human counterpart suggesting very low homology. In anaerobic conditions, higher biofilm units were found with decreased NADK activity.

Conclusion:

The results of this study suggest increased NADPH concentration in S. aureus plays a vital role in the biofilm formation and survival of this pathogen in any environmental conditions.

Keywords: Adenosine triphosphate, biofilms, NAD kinase, NADPH, root-mean-square deviation

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive cocci and an important cause of nosocomial infections. Appearance of multidrug resistance strains of S. aureus including resistant to vancomycin all over the world in such strains conspicuous variations are observed in colony morphology, physiology and growth characteristics due to high reductive conditions with poor acetate metabolism.[1,2,3,4] Studies have shown that high anaerobic conditions favor accumulation of NADPH and NADH in bacteria and these molecules inhibit NAD kinase (NADK).[5]

The numerous pivotal functions of NAD(P) in metabolism, transcription, signaling pathways and detoxification reactions makes nicotinamide dinucleotide a central molecule for cell viability, which means that its concentration is firmly regulated. The biosynthesis of NAD(P) have been elucidated in detail[6,7] in Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar and Salmonella typhimurium, a multifunctional protein NadR is reported as NAD-dependent repressor of transcription of genes implicated in NAD biosynthesis,[8,9] thus explains this pathway is regulated at the transcriptional level.

NAD is synthesized through de novo or pyridine salvage pathway and there are many differences exists between prokaryotes and eukaryotes.[6,7] The main metabolite in de novo NAD biosynthesis in all living organisms is quinolinic acid (QA). Eukaryotes synthesize QA via tryptophan degradation while prokaryotes obtain QA through the condensation of imino aspartate with dihydroxyacetone phosphate which is catalyzed by quinolinate synthetase system.[6,7] QA is transformed into nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN) by QA phosphoribosyltransferase afterward NaMN adenylyltransferase catalyzes adenylation of NaMN to nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide.[6,7,10] The nadD gene encoding NaMN adenylyltransferase was shown to be essential for survival in S. aureus and Streptococcus pneumonia that are fully dependent on niacin salvage pathway.[11] Finally, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide is changed into NAD through the reaction catalyzed by NAD synthetase encoded by gene nadE, this reaction is followed by the synthesis of NADP catalyzed by magnesium dependent ubiquitous enzyme NADK[6,7] - encoded by gene NADK. Since this reaction is the only biochemical step in the synthesis of NADP from NAD, NADK is therefore, key enzyme for NADP synthesis and for the NADP-dependent anabolic and biosynthetic pathways in the cell. NADKs show homo oligomer structures but differ in the molecular size and number of subunits.[12] The molecular size of subunit from prokaryotes is approximately 30–35 kDa, almost all known NADKs are oligomeric proteins consisting of 2-8 identical subunits of 30–60 kDa.[12]

NADK is a ubiquitous, allosteric enzyme, catalyzes the formation of NADP using adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as phosphoryl donor and plays a central role in coupling oxidative - reductive conditions. It dictates whether the system is in oxidative or reductive conditions based on the concentration of [NAD+/NADH] ratio near 1000, favors the oxidative conditions whereas [NADP+/NADPH] ratio near 0.01, favors the reductive conditions[13] and defense against oxidative stress[14] by providing electrons for reductive repair. This could be one of the most crucial growth-limiting stimuli to control the pathogenesis.[15] As, NAD(H) and NADP(H) participate in more than 300 different oxidative-reductive reactions[16] their importance in substance metabolism and energy metabolism has long been known in tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and de novo biosynthesis. NAD(H) is primarily involved in oxidative catabolic reactions, whereas NADP(H) participates in reductive anabolic reactions.[13] Thus, owing to the importance of NADK which is essential for the survival of microorganisms[17] the present study is focused on cloning, expression and characterization of NADK of S. aureus ATCC 12600.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and conditions

S. aureus ATCC 12600 and E. coli DH5α were obtained from Merck Biosciences. Pvt Ltd. S. aureus was grown on modified Baird Parker media at 37°C. A clear isolated colony exhibiting distinct zone and shiny black color was picked and inoculated in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and grown for overnight at 37°C and this grown S. aureus ATCC 12600 culture was used to characterize NADK. E. coli DH5α were used in the expression of S. aureus NADK gene cloned in pQE 30 vector.[18]

Biofilm assay

The biofilm assay was carried out for S. aureus ATCC 12600 grown in Luria-Bertani and BHI broths following earlier explained method.[19]

Kinetic study of NAD kinase

The cytosolic fraction was collected from the S. aureus to perform the enzyme assay and kinetics for NADK. The reaction mixture contains 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NAD, 10 mM ATP, 5 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, pure glucose-6- phosphate dehydrogenase, crude or pure NADK of S. aureus. The reaction mixture was incubated for 4-5 min at 37°C and absorbance was taken at 340 nm. The maximum velocity of the enzyme catalyzed reaction was calculated by taking varying concentrations of substrate NAD from 0.25 to 10 mM. KM and Vmax for NADK were determined using Hanes–Woolf plot by taking [So ] on X-axis and [So/Vo ] on Y-axis. From Y-intercept value obtained in the graph, KM was calculated.[20] Bradford method was applied to estimate the concentration of proteins.[21]

NAD kinase gene amplification and sequencing from Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from late log phase culture of S. aureus and NADK gene was amplified by using forward primer: 5’-CATGCGTTATACAATTT-3’ and reverse primer: 5’-TCATCGTTCTTCATCAC-3’ which were designed from the NADK gene sequence of S. aureus Mu 50 strain.[22] The cocktail reaction mixture of 50 μl contained 0.5 μg of chromosomal DNA, 100 μM of dNTP's mixture, 100 picomoles of forward primer, and reverse primer, 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Merck Biosciences. Pvt Ltd). Amplification parameters included an initial denaturation step for 10 min at 94°C; 40 cycles of each having denaturation at 94°C for 60 s, annealing at 37.35°C for 90 s and amplification at 72°C for 120 s which was followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min in a master cycler gradient Thermocycler (Eppendorf). Nanoparticle-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cleansing kit (Taurus Scientific, USA) was used to purify the PCR products which were then subjected to sequencing using dye terminating method at MWG Biotech India Ltd. Thus, obtained NADK gene sequence was deposited at GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank).

Cloning, expression and purification of NAD kinase

NADK gene was cloned in the Sma I site of pQE 30 and followed by transformation in E. coli DH5α. Thus formed clone was called as NADK-1. The insert in the clone was sequenced and on confirming the sequencing in the clone the gene was over-expressed with 1mM IPTG. The recombinant NADK [rNADK] was purified from the cytosolic fraction of clones by passing through nickel metal chelate agarose column (by following QIA express expression system protocol) and protein was eluted using 300 mM imidazole hydrochloride the product was analysed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).[18,23] The enzyme kinetics of purified rNADK was performed as described earlier in the section.

Sequence and structural analysis of NAD kinase

The three-dimensional structure of S. aureus NADK was built by using modeler 9v8 tool. The stereochemistry of the final model was verified by submitting to PROCHECK and ProSA-web servers. The structural alignment of S. aureus NADK and human NADK structures were carried out using PyMol software.[24,25,26] ATP and NAD docking to NADK of S. aureus and humanwas performed to find out the mode of binding and affinity variations using Molecular Operating Environment MOE version 2011.10 software (Chemical Computing Group, Canada).

Results

Characterization of NAD kinase

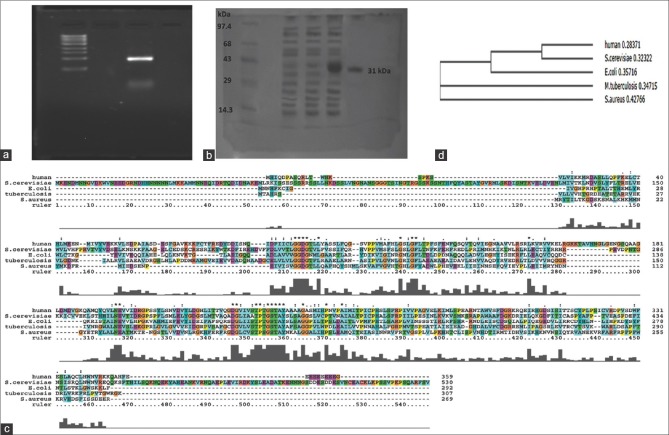

NADK is the most prominent enzyme whose products detects whether the system is in oxidative or reductive conditions. In the present study, we have cloned, sequenced, expressed, and characterized NADK gene from S. aureus ATCC 12600. The sequence of NADK (GenBank Accession number: JN645814) showed complete homology with NADK gene of all the strains of S. aureus reported in the database. The NADK gene expressed from NADK-1 clone was purified by passing through nickel metal chelate affinity column showed a molecular weight of 31 kD on 10% SDS-PAGE [Figure 1a and b].

Figure 1.

(a) Amplification of NAD kinase gene using NAD kinase 1 and NAD kinase 2 primers from the chromosomal DNA of Staphylococcus aureus. M Lane showing DNA ladder L1 lane showing amplified product of NAD kinase gene, (b) electrophoretogram showing the expression of recombinant NAD kinase clone in 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lane M: Molecular weight marker. Lane 1 and 2: Uninduced cell lysate of NAD kinase 1 clone. Lane 3: Induced cell lysate of NAD kinase 1 clone Lane 4: Purified recombinant NAD kinase. (c) Multiple sequence alignment of NAD kinase. (d) Phylogenetic tree based on NAD kinase sequence of Staphylococcus aureus with other bacterial NAD kinase sequences and Human NAD kinase

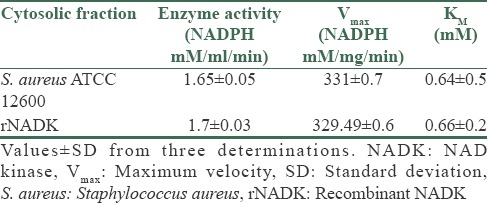

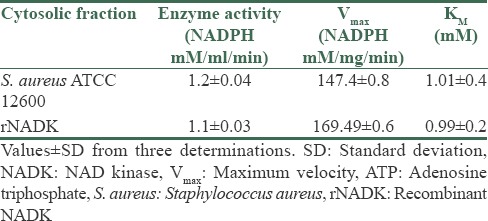

The NADK identified in the cytoplasm of S. aureus ATCC 12600 demonstrated an enzyme activity of 1.65 ± 0.05 mM/ml/min and KM 0.64 ± 0.5 mM [Table 1] for NADP substrate and for ATP as substrate the enzyme exhibited 1.2 ± 0.04 μM/ml/min as enzyme activity with KM 1.01 ± 0.4 mM. Similar results were observed with pure rNADK [Table 2], signifying the presence of only one NADK gene in S. aureus corroborating with the basic local alignment search tool and docking results. NADK docking of S. aureus results showed highest docking score with NAD (−13.9069 kcal) compared to ATP (−13.7903 Kcal) [Supplementary Table 1 (117.5KB, tif) and Supplementary Figure 1a (161.5KB, tif) and b (161.5KB, tif) ]; however, human NADK showed highest docking score with ATP (−12.7409) compared to NAD (−9.7059) [Supplementary Table 2 (209KB, tif) and Supplementary Figure 1c (161.5KB, tif) -d (161.5KB, tif) ]. The buildup of NADPH in the bacteria allosterically inhibits NADK[5] and in the present study the pure rNADK activity was inhibited by the NADPH [Supplementary Figure 2 (218.8KB, tif) ]. The enzyme kinetics when compared with other organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae,[27] Mycobacterium tuberculosis,[28,29,30] E. coli[29,30,31] and human[32] showed significant differences [Supplementary Table 3 (135.6KB, tif) ] correlating with the differences observed in the multiple sequence alignment of NADK gene sequence [Figure 1c and d].

Table 1.

The enzyme kinetics of NADK and rNADK for NAD substrate

Table 2.

The enzyme kinetics of NADK and rNADK for ATP substrate

Molecular docking of S. aureus NADK

(a) Docking of NAD with Staphylococcus aureus NAD kinase. (b) Docking of adenosine triphosphate with Staphylococcus aureus NAD kinase. (c) Docking of NAD with human NAD kinase (d) Docking of NAD with human NAD kinase

Molecular docking of human NADK

Graph showing the inhibition of NAD kinase with NADPH

The comparative NADK kinetics with other bacteria and human

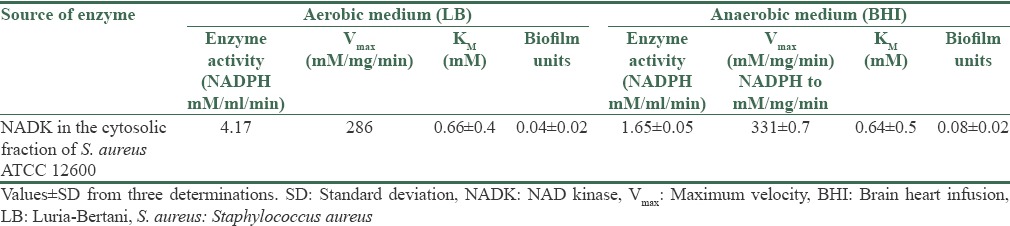

Increased NADK activity was observed in S. aureus ATCC 12600 grown in aerobic broth compared with anaerobic conditions indicating increased buildup of NADPH in the organism corroborating the high reductive conditions favoring high rate of biofilm formation [Table 3].

Table 3.

NADK activity in S. aureus ATCC 12600 grown in aerobic and anaerobic media

Comparative structural analysis of S. aureus NAD kinase with human NAD kinase

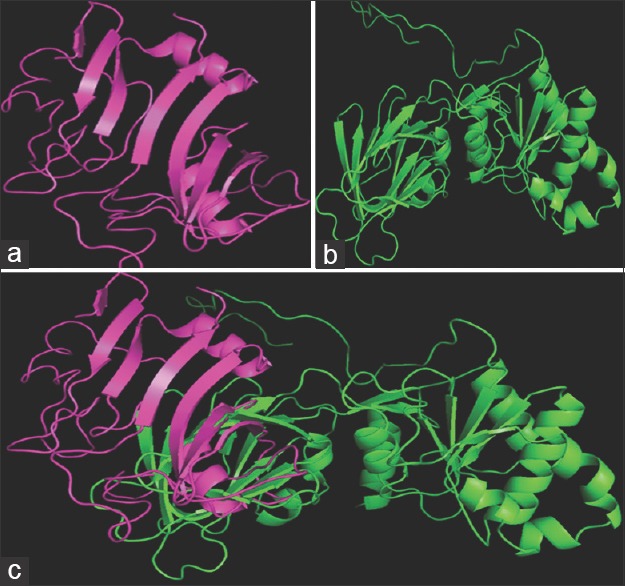

The structural alignment of S. aureus ATCC 12600 NADK [Figure 2a] and human NADK [Figure 2b] structures revealed an identity of 9.1% that is, distributed randomly throughout the conformation and when both structures were superimposed [Figure 2c], the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value 14.039Å indicates the extensive structural variations in both domain and nondomain regions. This value also implies distantly aligned variation between the Cα atoms of the backbones of two aligned structures.

Figure 2.

Structural comparison of Staphylococcus aureus NAD kinase (magenta) and human NAD kinase (Green) using PyMol. (a) Staphylococcus aureus NAD kinase; (b) human NAD kinase; (c) super imposed structures of human NAD kinase (green), staph NAD kinase (magenta)

Discussion

There is a growing recognition that NADP (H) is the crucial coenzyme for many cellular processes in living organisms, such as NADPH-dependent reductive anabolic pathways; signal transduction, cellular defense against stress.[33,34] Studies have indicated that NADK is an essential enzyme for the survival of microorganisms in varied environmental conditions;[17] therefore, the present study is focused on cloning, expression and characterization of NADK from S. aureus ATCC 12600. In S. aureus and in M. tuberculosis, the activity of NADK is inhibited intensively by NADP+[29,31] whereas in E. coli[35] and S. enteric[5] NADH and NADPH are potent allosteric negative modulators of NADK.

NADK mainly concerned with these reactions and dictates whether the system is in oxidative or reductive conditions. This could be one of the most crucial growth-limiting stimuli to control the pathogenesis.[15] The ratio of NAD/NADP+ and NADH/NADPH controls many pathways in S. aureus such as TCA cycle, de novo biosynthesis and this regulation has profound effect on the redox status which is a key factor in S. aureus for the production of toxins, virulence factors and biofilm formation.[19,26,36,37] In the present study, the anaerobic conditions favored biofilm formation with decreased NADK activity which explains there is a greater build-up of NADPH in the bacteria leading to increased synthetic phase [Table 3].

The comparison of amino acid sequences of several known prokaryotic and eukaryotic NADKs revealed a general structural organization consisting of a conserved catalytic domain within the C-terminus and variable N-terminal parts[12] but the regulatory patterns of NADKs differ distinctively among microbes. These conspicuous differences throw light on the pathogenesis of S. aureus in the human host as compared with other bacteria.

The structural analysis of NADK revealed that it has a very low homology with human NADK as indicated from the RMSD value 14.039Å. The results correlated with the enzyme kinetic data[28,29,30,31,32] which indicated that human NADK has very high affinity for the substrate compared to S. aureus NADK[32] [Supplementary Tables 1 (117.5KB, tif) -3 (135.6KB, tif) and Supplementary Figures 1 (161.5KB, tif) and 2 (218.8KB, tif) ]; which is understandable owing to the fact that high oxidative conditions prevails in human tissues compared with S. aureus. However, it is very well known that this human pathogen can colonize in any anatomical locales in the host[38] for which S. aureus must be influencing the cellular redox state thus regulating metabolic, signaling and transcriptional processes in the cell,[2,19,33,34,37] this probably facilitates in the colonization and biofilm formation.

Conclusion

In the present study, NADK which catalyzes the synthesis of NADP in S. aureus was cloned, sequenced, expressed and characterized. The results of the present study indicated the buildup of NADPH in S. aureus in reductive conditions favors higher biofilm formation and this phenomenon is vital in the survival and spread of its infection in both hospital settings and community-acquired conditions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Sciences University for providing funds and facilities under SBAVP scheme (SBAVP/Ph. D/02) to carry out this work.

References

- 1.Somerville GA, Chaussee MS, Morgan CI, Fitzgerald JR, Dorward DW, Reitzer LJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus aconitase inactivation unexpectedly inhibits post-exponential-phase growth and enhances stationary-phase survival. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6373–82. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6373-6382.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson JL, Rice KC, Slater SR, Fox PM, Archer GL, Bayles KW, et al. Vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains have impaired acetate catabolism: Implications for polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis and autolysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:616–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01057-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui L, Ma X, Sato K, Okuma K, Tenover FC, Mamizuka EM, et al. Cell wall thickening is a common feature of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5–14. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.5-14.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sifri CD, Baresch-Bernal A, Calderwood SB, von Eiff C. Virulence of Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants in the Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1091–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1091-1096.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grose JH, Joss L, Velick SF, Roth JR. Evidence that feedback inhibition of NAD kinase controls responses to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7601–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602494103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begley TP, Kinsland C, Mehl RA, Osterman A, Dorrestein P. The biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides in bacteria. Vitam Horm. 2001;61:103–19. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)61003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magni G, Amici A, Emanuelli M, Raffaelli N, Ruggieri S. Enzymology of NAD+synthesis. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1999;73:135–82, xi. doi: 10.1002/9780470123195.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penfound T, Foster JW. NAD-dependent DNA-binding activity of the bifunctional NadR regulator of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:648–55. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.648-655.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tritz GJ, Chandler JL. Recognition of a gene involved in the regulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:128–36. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.1.128-136.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone TW, Addae JI. The pharmacological manipulation of glutamate receptors and neuroprotection. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;447:285–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01851-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorci L, Pan Y, Eyobo Y, Rodionova I, Huang N, Kurnasov O, et al. Targeting NAD biosynthesis in bacterial pathogens: Structure-based development of inhibitors of nicotinate mononucleotide adenylyltransferase NadD. Chem Biol. 2009;16:849–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng S, Yongfu L, Ye L, Xiaoyuan W. Molecular properties, functions, and potential applications of NAD kinases. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2009;41:352–61. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1995. Other pathways of carbohydrate metabolism. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomposiello PJ, Bennik MH, Demple B. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3890–902. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3890-3902.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman G, Garbutt IT, Demnitz U. Ability of a Staphylococcus aureus isolate from a chronic osteomyelitic lesion to survive in the absence of air. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983;2:595–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02016574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster JW, Moat AG. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis and pyridine nucleotide cycle metabolism in microbial systems. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:83–105. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.1.83-105.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi F, Li Y, Li Y, Wang X. Molecular properties, functions, and potential applications of NAD kinases. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2009;41:352–61. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad UV, Vasu D, Kumar YN, Kumar PS, Yeswanth S, Swarupa V, et al. Cloning, expression and characterization of NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase from Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;169:862–9. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-0027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeswanth S, Nanda Kumar Y, Venkateswara Prasad U, Swarupa V, Koteswara rao V. Venkata Gurunadha Krishna Sarma P Cloning and characterization of l-lactate dehydrogenase gene of Staphylococcus aureus. Anaerobe. 2013;24:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer T. Enzymes Biochemistry, Biotechnology and Clinical Chemistry. 1st ed. Chichester, West Sussex, England: Horwood Publishing Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohta T, Hirakawa H, Morikawa K, Maruyama A, Inose Y, Yamashita A, et al. Nucleotide substitutions in Staphylococcus aureus strains, Mu50, Mu3, and N315. DNA Res. 2004;11:51–6. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. Molecular Cloning, A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bramucci E, Paiardini A, Bossa F, Pascarella S. PyMod: Sequence similarity searches, multiple sequence-structure alignments, and homology modeling within PyMOL. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl 4):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S4-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar PS, Kumar YN, Prasad UV, Yeswanth S, Swarupa V, Sowjenya G, et al. In silico designing and molecular docking of a potent analog against Staphylococcus aureus porphobilinogen synthase. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6:158–66. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.135246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad UV, Swarupa V, Yeswanth S, Kumar PS, Kumar ES, Reddy KM, et al. Structural and Functional analysis of Staphylococcus aureus NADP-dependent IDH and its comparison with Bacterial and Human NADPdependent IDH. Bioinformation. 2014;10:81–6. doi: 10.6026/97320630010081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apps DK. The NAD kinases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1970;13:223–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawai S, Mori S, Mukai T, Suzuki S, Yamada T, Hashimoto W, et al. Inorganic polyphosphate/ATP-NAD kinase of Micrococcus flavus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:57–63. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raffaelli N, Finaurini L, Mazzola F, Pucci L, Sorci L, Amici A, et al. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis NAD kinase: Functional analysis of the full-length enzyme by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7610–7. doi: 10.1021/bi049650w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori S, Kawai S, Shi F, Mikami B, Murata K. Molecular conversion of NAD kinase to NADH kinase through single amino acid residue substitution. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24104–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai S, Mori S, Mukai T, Hashimoto W, Murata K. Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli NAD kinase. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4359–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerner F, Niere M, Ludwig A, Ziegler M. Structural and functional characterization of human NAD kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:69–74. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minard KI, McAlister-Henn L. Sources of NADPH in yeast vary with carbon source. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39890–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Outten CE, Culotta VC. A novel NADH kinase is the mitochondrial source of NADPH in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2003;22:2015–24. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zerez CR, Moul DE, Gomez EG, Lopez VM, Andreoli AJ. Negative modulation of Escherichia coli NAD kinase by NADPH and NADH. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:184–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.184-188.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Somerville GA, Cockayne A, Dürr M, Peschel A, Otto M, Musser JM. Synthesis and deformylation of Staphylococcus aureus delta-toxin are linked to tricarboxylic acid cycle activity. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6686–94. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6686-6694.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkateswara Prasad U, Vasu D, Yeswanth S, Swarupa V, Sunitha MM, Choudhary A, et al. Phosphorylation controls the functioning of Staphylococcus aureus isocitrate dehydrogenase – Favours biofilm formation. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2015;30:655–61. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2014.959945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Molecular docking of S. aureus NADK

(a) Docking of NAD with Staphylococcus aureus NAD kinase. (b) Docking of adenosine triphosphate with Staphylococcus aureus NAD kinase. (c) Docking of NAD with human NAD kinase (d) Docking of NAD with human NAD kinase

Molecular docking of human NADK

Graph showing the inhibition of NAD kinase with NADPH

The comparative NADK kinetics with other bacteria and human