SUMMARY

Stable cell lines that express the canine-derived A2a adenosine receptor (A2aAR) have been generated. Using a previously characterized anti-A2aAR antibody probe, we have identified the recombinant receptor protein and examined the desensitization process of this G protein-coupled receptor. Agonist exposure induced a rapid desensitization of A2aAR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity. This was associated with reduced affinity of the receptor for the A2aAR-selective agonist [3H]CGS21680 and agonist-stimulated phosphorylation of the receptor protein. Agonist-stimulated A2aAR sequestration into a light membrane fraction was also detected over the same time frame but, whereas inhibition of this process did not affect the extent of desensitization, the rapid recovery normally observed after short term agonist exposure was dramatically reduced. Long term agonist treatment resulted in the down-regulation of A2aARs and up-regulation of Giα2 and Giα3, as determined by immunoblotting. Recovery of A2aAR function after agonist removal required several hours and was associated with the return of receptor levels to control values. In contrast, inactivation of Gi proteins by pertussis toxin treatment did not alter the extent of agonist-induced desensitization observed. Neither short nor long term desensitization could be mimicked by elevation of intracellular cAMP levels alone. Therefore, these data suggest that A2aAR desensitization is mediated by multiple, temporally distinct, agonist-dependent processes. Agonist-stimulated phosphorylation of the receptor may induce short term desensitization by impairing receptor-Gs coupling, whereas long term down-regulation of receptor number and up-regulation of inhibitory G proteins mediate long term adaptation.

The ability of the ubiquitous nucleoside adenosine to modulate important physiological processes such as platelet aggregation, lipolysis, and neurotransmission has been known for many years (1). Only recently, however, has the molecular nature of the cell surface ARs responsible for initiating these events been elucidated (2). Functional and molecular cloning studies have demonstrated that ARs can be divided into at least three groups; A1ARs mediate inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity via interaction with one (or more) Gi proteins, whereas A2ARs stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity by coupling to Gs (2). Expression of the rat A3AR confers adenosine-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity, although whether this is its only signaling function in vivo is uncertain (3). Each of the cloned ARs exhibits the predicted seven-membrane-spanning domain topography characteristic of most G protein-coupled receptors (4, 5).

A2ARs can be further divided into A2a and A2b subtypes, which have been distinguished by pharmacological and molecular biological studies (6–8). Although both receptors are capable of stimulating adenylyl cyclase activity, only the A2aAR is capable of binding the agonist CGS21680 with high affinity (7,8). Furthermore, in situ hybridization and Northern blotting experiments have demonstrated that these receptors exhibit distinct patterns of expression (7).

Agonist-induced desensitization or refractoriness is a universal feature of G protein-coupled receptors, although only the β2-adrenergic receptor and rhodopsin have been studied extensively. These studies suggest that, after short term agonist exposure, agonist-occupied β2-adrenergic receptors uncouple from Gs due to phosphorylation events catalyzed by receptor-specific kinases (e.g.,βARK-1 and -2) and/or kinases regulated by levels of intracellular second messengers (e.g., PKA). Phosphorylation of the receptor by βARK(s) increases the affinity of the receptor for cytosolic factors (‘arrestin proteins’), thereby competitively inhibiting receptor binding to Gs whereas phosphorylation by PKA directly impairs the ability of the receptor to interact with Gs as well as increasing its ability to couple to Gi (9,10). Receptor sequestration, a process whereby a receptor translocates to an ill defined ‘light membrane’ fraction, has been described in several cell lines, although the mechanisms by which this occurs are poorly understood (11, 12). The mechanisms by which long term desensitization occurs are also unclear, although studies on many receptors have shown that prolonged exposure to agonists can regulate expression of both a receptor and/or its associated G protein (13–16). Moreover, phenomena whereby long term activation of the stimulatory pathway of adenylyl cyclase results in the enhanced functioning of other G protein-coupled pathways have also been described (16,17).

Several studies in rat kidney cells (18), vascular smooth muscle cells from rat aorta (19), NG108–15 cells (21), and DDT1 MF-2 cells (20) have shown that the A2AR response undergoes a rapid desensitization after short term exposure (several minutes) to agonists such as 2-chloroadenosine, NECA (18, 19, 21), or the more A2aAR-selective ligand PAPA-APEC (20). Moreover, this desensitization is homologous, inasmuch as stimulatory hormone-, fluoride-, and forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activities are unaffected under these conditions (18–21). Nevertheless, study of A2AR desensitization in established cell lines has several limitations. First, the A2AR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase response in many cell types is relatively small, compared with that of other Gs-coupled receptors. Second, it is possible that a given cell line may express both A2aARs and A2bARs, as well as other A2AR subtypes that have yet to be isolated; indeed, we have noted that A2aARs from liver and brain exhibit different reactivities to two polyclonal antibody preparations raised against distinct regions of the canine-derived A2aAR protein (22). As a result of these technical difficulties, the mechanisms by which the observed desensitization occurs have remained unknown. To circumvent these problems, we have transfected CHO cells with the canine thyroid-derived RDC8 cDNA, which codes for an A2aAR (23), and isolated clonal cell lines that exhibit both high levels of specific agonist binding and robust stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity, to begin to characterize mechanisms of short and long term A2aAR desensitization at the molecular level.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

[32P]Phosphoric acid, [α-32P]ATP, [α-32P]NAD+, [3H] cAMP, [3H]CGS21680, and l25I-Protein A were from DuPont-New England Nuclear. Protein A-agarose, soybean trypsin inhibitor, leupeptin, PMSF, benzamidine, pepstatin A, chloramine T, ATP, dATP, GTP, creatine phosphokinase, concanavalin A, and HEPES (sodium salt) were from Sigma. Cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B was from Pharmacia. Phosphocreatine, restriction enzymes, and T4 ligase were from Boehringer-Mannheim. All electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad. Cell culture reagents were from GIBCO. PTx was from List Biochemicals. The plasmid pSVNeo was from Pharmacia. All other chemicals were of the highest grade commercially obtainable.

Cell culture and transfections

Transfected CHO cells were grown as monolayers in 75-cm2 flasks, in Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μg/ml G418 (to maintain selection pressure). Approximately 3 × 105 cells in 25-cm2 flasks were co-transfected with 30 μg of pBC12-BI expression vector (described in Ref. 24 and kindly provided by Dr. Bryan Cullen, Duke University) containing wild-type A2aAR cDNA (described in Ref. 23 and kindly provided by Dr. Gilbert Vassart, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium) and 1.5 μg of pSVNeo (conferring G418 resistance), by a modified calcium phosphate precipitation/15% glycerol shock procedure (24). Cells were maintained in the presence of 400 μg/ml G418 until ~14 days after transfection, when isolated colonies were selected and replated. Identification of receptor-expressing clones was by radioligand binding using 20 nM [3H] CGS21680, as described below.

Crude membrane preparation and radioligand binding

Membranes from CHO cells were prepared as follows. After aspiration of medium from the flasks, monolayers were rapidly washed three times with 20 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA). Four milliliters of fresh lysis buffer were then added, into which the cells were scraped before Dounce homogenization (20 strokes) on ice. After centrifugation at 42,000 x g for 15 min at 4°, membranes were resuspended in a minimal volume of 50 mM HEPES, pH 6.8, 10 mM MgCl2 (50/10 buffer), with 0.15 unit/ml ADA, for immediate use in binding assays as described previously (25). Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (26). Typically, experiments using CHO cells employed 20–80 μg of protein/tube.

Desensitization conditions

Cells in monolayers nearing confluence were washed once with 20 ml of PBS, and fresh Ham’s F-12 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum was added. NECA and ADA (included to remove adenosine released by the cells) were then added (to the final concentrations specified in the figure legends) and incubations were carried out for the indicated times at 37° in a cell culture incubator. Incubations were terminated by placing flasks on ice, aspirating off the medium, and rapidly washing the monolayer three times with 20 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer. Cells were then detached by scraping into 4 ml of lysis buffer and membranes were made as described previously.

Photoaffinity labeling

This was performed as described previously, using 0.8 nM 125I-azido-PAPA-APEC (27); membranes from one 75-cm2 flask were used for each condition.

Assay of adenylyl cyclase activity

Membranes prepared from one flask of transfected CHO cells were immediately resuspended by Dounce homogenization (20 strokes) in 1 ml of 75 mM TrisHCl (pH 7.4 at 30°) containing 200 mM NaCl and 12.5 mM MgCl2. After incubation with 6 units/ml ADA for 15 min at 30° to remove endogenous adenosine, 40 μl of membrane suspension (~40 μg of protein) were added to 40 μl of reaction mixture (0.14 mM dATP, 5 mM phosphocreatine, 30 units/ml creatine phosphokinase, 12 μM GTP, and 1.5 μCi of [α-32P]ATP) and 20 μl of water or drugs. Papaverine (100 μM) was also included to inhibit low-Km phosphodiesterases. For experiments in which NaF or forskolin was included in the assay, GTP was omitted from the reaction mixture. All incubations were for 15 min at 30°. Reactions were terminated by placing the tubes on ice and adding 1 ml of stop solution (10 × 103 cpm/ml [3H]cAMP, 0.3 mM cAMP, and 0.4 mM ATP) to each tube. [32P]cAMP was purified by sequential chromatography with Dowex-50 and alumina columns, as described by Salomon et al. (28).

Preparation of a light membrane fraction

Three flasks of CHO-A2aAR cells were used for each light membrane preparation. After treatment with vehicle or agonist, monolayers were rapidly washed with ice-cold PBS and scraped into 4 ml of PBS containing 0.25 mg/ml concanavalin A to block further receptor redistribution (12). Cells were collected by centrifugation and were resuspended in 5 ml of lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors previously shown to prevent A2aAR degradation (25); these were soybean trypsin inhibitor (100 μg/ml), leupeptin (5 μg/ml), pepstatin A (1 μg/ml), and PMSF (0.1 mM). After Dounce homogenization (20 strokes), a pellet was sedimented by centrifugation at 42,000 × g for 20 min. Four milliliters of the supernatant were collected, and light membranes were pelleted by centrifugation at 140,000 × g for 70 min. The resulting ‘glassy’ pellets were resuspended and equivalent amounts were prepared for electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

For immunoblotting of G protein subunits, the appropriate amounts of membrane protein were collected by centrifugation and prepared for electrophoresis by resuspension in 10% (w/v) SDS electrophoresis sample buffer and boiling for 5 min before loading for SDS-PAGE. For immunoblotting of A2aARs, ~1 mg of membrane protein was collected by centrifugation and solubilized with 100 μl of 0.8% (v/v) Triton X-100 in 100 mM Na2HPO4, pH 6.5, 5 mM EDTA, containing 5 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μM benzamidine, and 0.1 mM PMSF. After incubation on ice for 1 hr to solubilize membrane proteins, soluble fractions were collected by centrifugation at 100,000 x g for 1 hr at 4°, in a benchtop ultracentrifuge. Protein concentrations of soluble fractions were then determined and 300 μg were added to an equal volume of 16% (w/v) SDS electrophoresis sample buffer before boiling for 2 min and electrophoresis. Discontinuous electrophoresis was performed as described by Laemmli (29), using 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide resolving gels. Transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose and immunodetection with primary antibodies and 125I-Protein A were performed as described previously (22).

The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting at the concentrations indicated in parentheses: TP/2 (4 μg/ml affinity-purified IgG) for detection of A2aARs (22), TG982 (1/4000 dilution of serum) for detection of Giα2 (30), RM/1 (1/1000 dilution of serum) for detection of Gsα (31), TG977 (1/8000 dilution of serum) for detection of Giα3 (30), and TG987 (1/4000 dilution of serum) for detection of G protein β subunits (30). TP/2 was affinity purified from whole serum as described previously (22). Blots were exposed to Kodak XAR film with dual intensifying screens for 12–48 hr. Quantitation of immunoblots was by excision and counting of γ-radiation from bands of interest, with suitable correction for background radiation. For each antibody concentration used, initial experiments were performed to determine the range in which the relationship between the amount of protein loaded and the 125I-Protein A detected was linear, subsequent comparative immunoblots used protein loadings within these ranges.

Labeling of CHO cells with [32P]orthophosphate

Cell monolayers nearing confluence were washed twice with PBS, and fresh Ham’s medium minus serum, supplemented with 32Pi (5 mCi/treatment), 30 μM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, and 0.3 unit/ml ADA, was added. After 2.5 hr at 37° in a cell culture incubator, agonist, forskolin, or vehicle was added directly to this medium and the incubation was continued for an additional 30 min.

Immunoprecipitation of A2aARs

After labeling, flasks were placed on ice, the medium was removed, and the monolayers were rapidly washed five times with ice-cold PBS. Cells were then scraped into 4 ml of HPEN (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA). This buffer also included protease inhibitors (10 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 0.1 mM PMSF) and phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM NaF, 1 mM phosphoserine, 1 mM phosphothreonine, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 0.1 mM sodium vanadate). After Dounce homogenization (20 strokes), membrane pellets were collected by centrifugation. These pellets were washed twice by rehomogenization in HPEN plus inhibitors and further centrifugation. The final membrane preparation was solubilized in 0.8% Triton X-100/HPEN plus inhibitors by pipette trituration and passage through a 20-gauge needle. After solubilization on ice for 2 hr, soluble fractions were collected by centrifugation at 100,000 x g for 1 hr. SDS was then added to a final concentration of 0.08% and the mixture was precleared of nonspecifically binding proteins by overnight incubation at 4° with preimmune serum and 150 μl of Protein A-agarose. After centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated with 20 μg/ml affinity-purified TP/2 antibodies for 3 hr on ice; nonspecific immunoprecipitation was assessed by the inclusion of antigenic peptide at 20 μg/ml After the addition of 30 μl of Protein A-agarose and further incubation for 2 hr, immunoprecipitates were collected by centrifugation and extensively washed with HPEN plus inhibitors containing 1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% SDS, followed by two washes with HPEN and inhibitors without detergent. Phosphoproteins were eluted by the addition of 30 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and incubation at room temperature for 60 min. After centrifugation to sediment the Protein A-agarose, equal volumes of supernatant were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

PTx-catalyzed [32P]ADP-ribosylation

This was performed on isolated membrane preparations as described by Ribeiro-Neto et al (32).

Data analysis

Scatchard plots (33) of radioligand binding data were fitted by least squares analysis. Adenylyl cyclase dose-response curves were analyzed by a computer-assisted curve-fitting program previously validated (34). Data in the text and in tables are presented as mean ± standard errror values for the number of experiments indicated, unless otherwise stated. Graphs depict representative experiments, which were performed at least twice. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (two-tailed), with an α probability of 0.05.

Results

Characterization of CHO cells expressing A2aARs

Co-transfection of CHO cells with pSVNeo and PBC-A2aAR cDNAs resulted in the isolation of several clonal cell lines that exhibited at least 50% specific binding of 20 nM [3H]CGS21680; one of these clones was chosen for further analysis. Scatchard analysis of data from saturation isotherms performed on membrane preparations showed that [3H]CGS21680 bound to a single, saturable, high affinity site with a Kd of 7.4 ± 1.7 nM (10 experiments) and Bmax values ranging from 0.88 to 2.20 pmol/mg in 10 experiments. The existence of a single class of binding sites for [3H]CGS21680 and the Kd value observed are consistent with previous observations of endogenous A2aARs in rat, bovine, and canine striatum, as well as those from PC-12 cells (35, 36). In parallel experiments, no specific binding of [3H]CGS21680 was detected in membranes from nontransfected CHO cells (data not shown).

The expressed A2aAR was functional, in as much as membranes from transfected cells displayed a ligand-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity that exhibited the expected A2aAR pharmacology, i.e., a potency order of NECA > CGS21680 > (R)-PIA > (S)-PIA, with Hill coefficients for each of these ligands of 0.9 or greater, indicative of interaction of each ligand with a single class of receptor binding sites. The response of membranes from nontransfected cells to either 10 μM CGS21680 or 10 μM NECA was barely detectable (~5% above basal). Therefore, the adenylyl cyclase response observed in membranes from transfected cells was due to the expression of the A2aAR cDNA.

Agonist-induced desensitization of A2aAR function

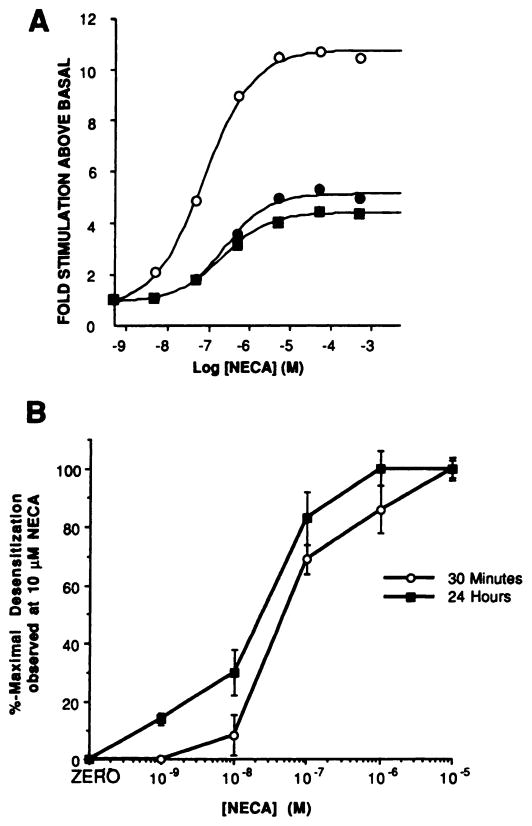

Fig. 1 and Table 1 show the desensitization pattern of A2aAR function after exposure of cells to 10 μM NECA and 0.3 unit/ml ADA. Desensitization was first detected after a 15-min agonist exposure, and after 30 min the maximal stimulation elicited by NECA was ~50% of that observed in membranes prepared from cells that had been treated with ADA alone (Fig. 1A; Table 1). Incubation with NECA for 60 min or 120 min did not produce any further reduction in maximal stimulation; indeed, after incubation with agonist for 24 hr, the maximal stimulation produced by NECA fell only slightly further, to ~40% of that observed in membranes from control cells (Fig. 1A; Table 1). Desensitization of the A2aAR response was associated with large reductions in the maximal adenylyl cyclase stimulation produced by NECA but with only a small increase in its EC50 value (Fig. 1A; Table 1). The abilities of 30-min or 24-hr exposure of cells to NECA to elicit desensitization exhibited similar dose dependencies (IC50 for 30-min exposure, ~40 nM; for 24-hr exposure, ~20 nM) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Desensitization of the A2aAR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase response. A, Dose dependence of NECA-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in membranes prepared from cells treated in the absence (○) or presence of 10 μM NECA for either 30 min (●) or 24 hr (■) at 37°. This experiment is representative of 10 that produced quantitatively similar results; basal activities were 7.9 ± 2.2 pmol/min/mg (control), 8.0 ± 0.6 pmol/min/mg (30-min treated), and 7.0 ± 1.0 pmol/min/mg (24-hr treated). B, Dose dependence of A2aAR desensitization to increasing concentrations of NECA at 30 min and 24 hr. Data are presented as a percentage of the desensitization observed with 10 μM NECA (set at 100%); the mean desensitization produced by exposure to 10 μM NECA in these experiments was to 59% (30 min) and 45% (24 hr) of the 10 μM NECA-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity produced in membranes from ADA-treated cells. Each data point is the mean ± standard error of three separate determinations.

TABLE 1. Time course off onset of A2aAR desensitization.

Monolayers of CHO-A2aAR cells were treated either with 10 μM NECA and 0.3 unit/ml ADA or with ADA alone (controls) for the indicated times before extensive washing, membrane preparation, and assay of adenylyl cyclase activity with increasing concentrations of NECA, as described in Experimental Procedures. Dose-response curves were generated by a computer modeling program, to give EC50 and maximal fold stimulation values. For these experiments, the maximal fold stimulation above basal activity obtained with NECA in membranes from ADA-treated cells (controls) was 10.3 ±1.4 (mean ± standard error, 15 experiments)

| Stimulation | EC50 | na | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of control | μM | ||

| Control | 100 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 15 |

| 15min | 86.0 ± 0.5 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 3 |

| 30min | 52.9 ± 3.3 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 3 |

| 60 min | 57.8 ± 1.6 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 3 |

| 120 min | 65.4 ± 1.2 | 0.16 ± 0.10 | 3 |

| 24 hr | 42.0 ± 3.7 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 4 |

n, number of experiments.

Short term (30-min) or long term (24-hr) desensitization produced by treatment with 10 μM NECA did not result in any changes in the efficacies with which sodium fluoride or forskolin was able to stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity, suggesting that the Gs-catalytic unit interaction is unaffected by the desensitization process (Table 2). Therefore, the desensitization process selectively diminishes productive interaction between the A2aAR and Gs.

TABLE 2. NaF- and forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activities in membranes from CHO-A2aAR cells after agonist treatment.

Cells were incubated with 0.3 unit/ml ADA in the absence (control) or presence of 10 μM NECA for either 30 min or 24 hr at 37°. Membranes were then prepared for assay of adenylyl cyclase activity with 10 mM NaF and 10 μM forskolin, as described in Experimental Procedures. The values for fold stimulation above basal are means ± standard errors for three experim ents. Basal activities in these experiments were 8.0 ± 3.3 pmol/min/mg (control), 6.5 ± 2.2 pmol/min/mg (30 min treated), and 4.8 ±1.1 pmol/min/mg (24-hr treated)

| Adenylyl cyclase activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 10 mM NaF | 10 μM Forskolin | |||

|

|

|

|||

| 30 min | 24 hr | 30 min | 24 hr | |

| pmol/min/mg | ||||

| Control | 15.8 ± 2.9 | 14.7 ± 3.7 | 9.9 ± 1.3 | 9.4 ± 0.5 |

| +10 μM NECA | 14.6 ± 0.7 | 13.6 ± 2.8 | 9.2 ± 2.2 | 10.1 ± 0.2 |

Agonist-induced changes in [3H]CGS21680 binding to the A2aAR

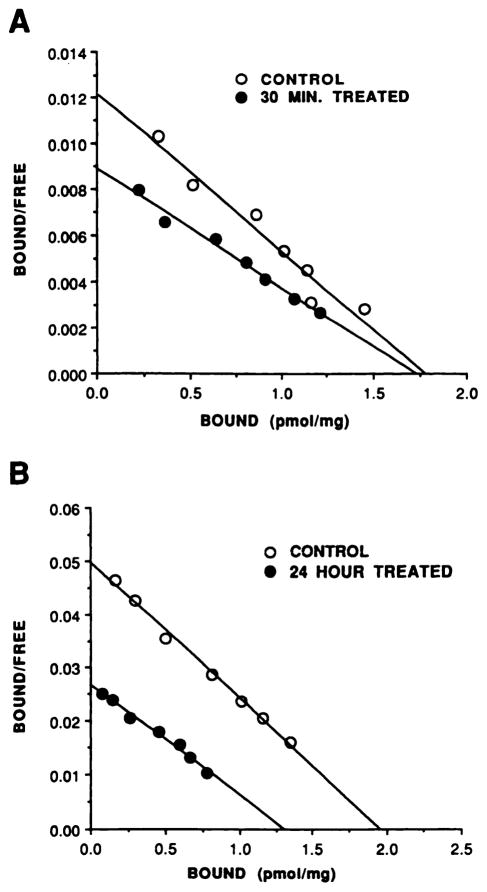

After an agonist exposure time sufficient to cause functional desensitization, the number of binding sites for [3H] CGS21680 did not change but the Kd increased by ~2-fold (Kd increased from 10.0 ± 1.5 nM to 20.5 ± 3.1 nM, three experiments, p < 0.05; Bmax values were 1.46 ± 0.30 pmol/mg and 1.71 ± 0.44 pmol/mg for control and 30-min-treated samples, respectively, p > 0.1); Scatchard analysis of the data demonstrated that the whole population of [3H]CGS21680 binding sites were converted to the lower affinity state, because binding to agonist-treated cells was still consistent with a single class of binding sites (Fig. 2A). Because agonists display a higher affinity for receptors that are coupled to their appropriate G protein, the increase in Kd observed after agonist exposure is consistent with reduced coupling efficiency between the A2aAR and Gs.

Fig. 2.

Scatchard analysis of [3H]CGS21680 binding after short and long term desensitization. CHO-A2aAR cells were incubated with 0.3 unit/ml ADA, in the absence or presence of 10 μM NECA, for either 30 min (A) or 24 hr (B) before membrane preparation for [3H]CGS21680 saturation binding experiments, as described in Experimental Procedures. ○, Binding in membranes from ADA-treated cells (controls); ●, binding in membranes from 10 μM NECA-treated cells. Data are presented from single experiments, which are representative of at least three performed for each time point.

[3H]CGS21680 saturation binding experiments on membranes prepared from cells that had been treated with agonist for 24 hr exhibited additional alterations in agonist binding (Fig. 2B). Hence, whereas binding in membranes from treated cells was still of lower affinity (Kd increased from 10.3 ±1.1 nM to 17.5 ± 2.8 nM, three experiments, p < 0.05), the total number of agonist binding sites was also reduced by approximately 40% (Bmax was reduced from 1.91 ± 0.31 pmol/mg to 1.25 ± 0.20 pmol/mg, three experiments, p < 0.05).

Therefore, changes in agonist binding appear to occur in two stages; short term agonist exposure induces an apparent impairment of the coupling between the A2aAR and Gs, manifested as reduced affinity of the receptor for [3H]CGS21680. Long term agonist exposure also induces down-regulation of the total number of agonist binding sites.

Quantitation of A2aARs in membranes from control and desensitized cells

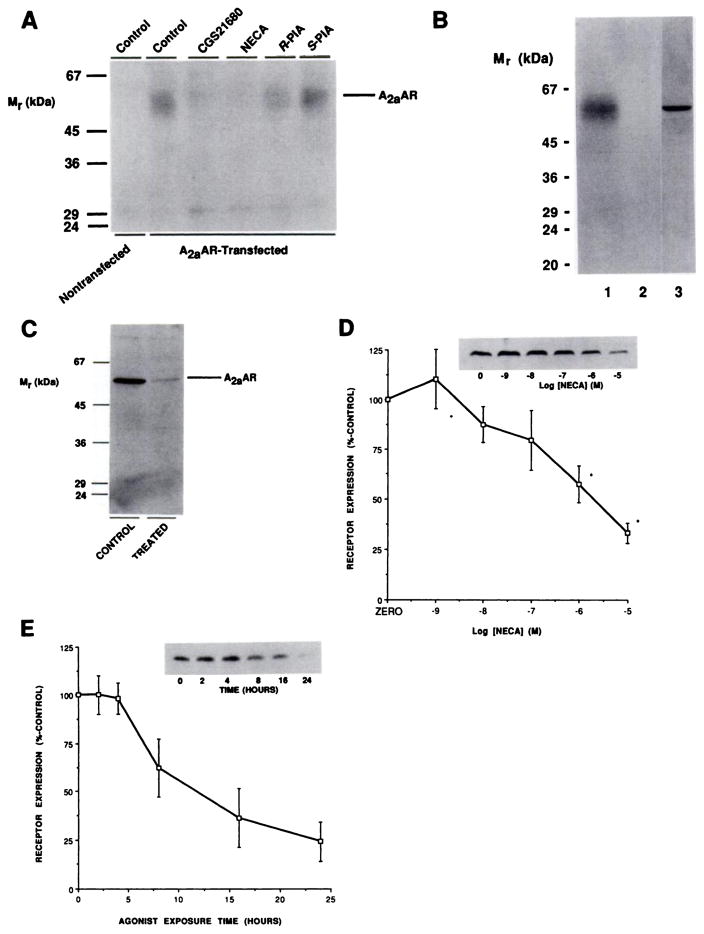

The identity of the expressed A2aAR was determined by two methods. Photoaffinity labeling of CHO cell membranes with the agonist photoaffinity probe 125I-azido-PAPA-APEC identified a single band, of 60 kDa, which was not present in nontransfected CHO cells (Fig. 3A). The labeling of this protein was blocked by AR agonists in a manner consistent with an A2aAR pharmacology, i.e., CGS21680 = NECA > (R)-PIA > (S)-PIA (Fig. 3A). Immunoblotting of membranes from transfected cells with affinity-purified antibody TP/2 identified a single immunoreactive band, at 60 kDa, which was absent in nontransfected cells and which comigrated exactly with the labeled protein (Fig. 3B). We have previously characterized the ability of this antibody to recognize endogenous canine A2aARs, by immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation of photoaffinity-labeled receptors (22).

Fig. 3.

Quantitation of A2aARs by immunoblotting after long term desensitization. A, Photoaffinity labeling of A2aARs with 125I-azido-PAPA-APEC. Membranes from nontransfected or A2aAR-transfected CHO cells were subjected to photoaffinity labeling as described in Experimental Procedures. The indicated agonists were present at a final concentration of 1 μM. B, Co-migration of A2aARs identified by photoaffinity labeling and immunoblotting. Membranes from A2aAR-transfected CHO cells were Identified by photoaffinity labeling in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of 1 μM NECA or immunoblotting with 4 μg/ml affinity-purified TP/2 (lane 3), as described in Experimental Procedures. C, Treatment of CHO-A2aAR cells with 0.3 unit/ml ADA for 24 hr at 37° in the absence (CONTROL) or presence (TREATED) of 10 μM NECA before membrane preparation and solubilization for immunoblotting with 4 μg/ml affinity-purified TP/2, as described in Experimental Procedures. This experiment is one of four performed, which produced quantitatively similar results. D, Dose dependence of A2aAR loss with increasing concentrations of NECA. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of NECA for 24 hr at 37° before membrane preparation, immunoblotting with TP/2, and quantitation as described in Experimental Procedures. Data are presented as means ± standard errors for three experiments. Inset, autoradiograph from one such experiment. *, Statistically significant (p < 0.05) reduction in receptor levels. E, Time course of loss of immunoreactive A2aAR. Cells were incubated at 37° with 10 μM NECA for the indicated times before membrane preparation and immunoblotting with 4 μg/ml affinity-purified TP/2. The data are presented as mean ± half the range of values from two experiments, one of which is depicted in the Inset.

To determine changes in the total A2aAR population, rather than just those receptors identified in agonist radioligand binding studies, we used antibody TP/2 in comparative immunoblotting studies. Immunoblotting of membranes from cells that had been treated for 24 hr in the presence or absence of 10 μM NECA demonstrated that a dramatic reduction in the level of immunoreactive receptors was associated with conditions under which the A2aAR response underwent functional desensitization (87 ± 6% reduction, compared with levels in control cells, four experiments) (Fig. 3C). The loss of immunoreactive A2aARs was dose dependent, although relatively high doses were required (Fig. 3D). Time-course experiments showed that receptor number remained steady until 4 hr. Receptor loss was detected at 8 hr of treatment, and after 24 hr levels of receptor reached their minimum level (Fig. 3E).

A2aAR sequestration after short term desensitization

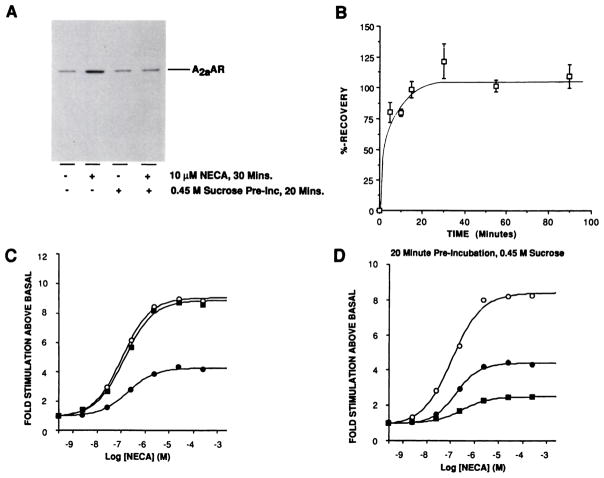

Immunoblotting studies demonstrated that receptor levels did not decline until after several hours of agonist exposure. Therefore, mechanisms other than receptor loss must have been responsible for the short term uncoupling and desensitization. One possible explanation was that receptor sequestration, analagous to that described for other G protein-coupled receptors (11, 12, 37–41), occurred. However, preincubation with 0.45 M sucrose, an inhibitor of receptor internalization in CHO cells (37), did not affect the subsequent ability of NECA to cause desensitization after a 30-min agonist exposure (the response to 10 μM NECA was reduced to 61 ± 12% of control stimulation, three experiments). These observations suggested either that the A2aAR did not undergo sequestration or that it underwent sequestration but this process was not involved in mediating short term desensitization. To discriminate between these possibilities, light membrane fractions were prepared, for immunoblotting with TP/2, from cells to which agonist was added after preincubation with or without sucrose (Fig. 4A); these experiments demonstrated that agonist treatment caused a rapid accumulation of receptors in light vesicles, consistent with a sequestration event (240 ± 30% increase, three experiments). However, sucrose pretreatment completely inhibited agonist-stimulated A2aAR accumulation in light membranes (4 ± 6% increase, three experiments) without drastically affecting basal levels of receptor in this membrane fraction (13 ± 7% increase in basal levels of receptor due to sucrose treatment, three experiments) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

A2aAR sequestration and recovery after short term desensitization. A, Cells were preincubated in medium with or without 0.45 M sucrose for 20 min at 37° before the addition of ADA alone (control) or with NECA to a final concentration of 10 μM and incubation for an additional 30 min. Light membrane fractions were then prepared and equal amounts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with affinity-purified anti-A2aAR antibodies, as described in Experimental Procedures. This experiment is one of three performed, which produced similar results. B, For recovery of A2aAR function after short term desensitization, cells were treated with or without 10 μM NECA and 0.3 unit/ml ADA for 30 min at 37°. Treated cells were then washed three times with warm PBS and incubated in agonist-free medium for the indicated times at 37°. Membranes were then simultaneously prepared for assay of adenylyl cyclase activity in the absence or presence of 10 μM NECA. The mean desensitization in these experiments was to 58% of untreated controls. Data points are presented as means ± standard errors from three separate determinations. Percentage of recovery was calculated as 100 × [fold stimulation (recovering cells) – fold stimulation (treated cells)/fold stimulation (control cells) – fold stimulation (treated cells)]. C, Cells were treated with (●) or without (○) 10 μM NECA for 30 min at 37°. One batch of treated cells were then washed and incubated in agonist-free medium, as described in B, for an additional 30 min (■). Membranes were then prepared simultaneously for assay of adenylyl cyclase activity with increasing concentrations of NECA. This experiment is one of three performed, which produced similar results. D, Cells were preincubated for 20 min at 37° with medium containing 0.45 M sucrose before the addition of ADA, with or without NECA, and assay of adenylyl cyclase activity as described for C. This is one of three experiments, which produced similar results.

Intriguingly, although sucrose pretreatment did not block short term desensitization, it altered the ability of the cells to recover from this state. The ability to regain adenylyl cyclase responsiveness was studied after exposure of the cells to 10 μM NECA for 30 min. After agonist removal, maximal adenylyl cyclase stimulation was regained very rapidly (t½ < 5 min) and remained stable for at least 90 min; analysis of NECA dose-response curves demonstrated that both potency and efficacy of A2aAR stimulation were completely restored (Fig. 4, B and C). Preincubation for 20 min with 0.45 M sucrose before agonist addition drastically reduced the resensitization observed 30 min after agonist washout (Fig. 4D). Hence, whereas untreated cells recovered to 90 ± 7% (four experiments) of the control stimulation 30 min after agonist removal, sucrose-pretreated cells either recovered only marginally or, as shown in Fig. 4D, exhibited further desensitization (pretreated cells recovered to 44 ± 15% of the control stimulation, four experiments).

Agonist-stimulated phosphorylation of the A2aAR

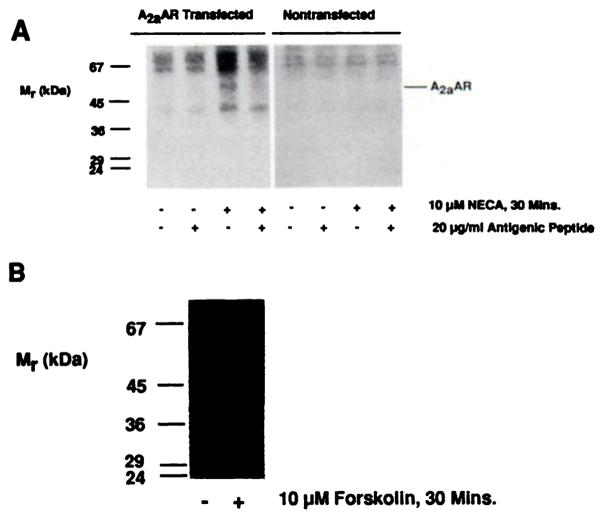

Because inhibition of receptor sequestration did not affect the ability of the A2aAR to desensitize after 30-min agonist exposure, we wished to ascertain whether the receptor was modified during the desensitization process. Phosphorylation was an obvious candidate for such a modification, because this has been implicated in mediating short term desensitization of both rhodopsin and the β2-adrenergic receptor, both of which bear structural similarities to the A2aAR (4). Hence, we labeled CHO-A2aAR cells with [32P]orthophosphate and incubated the cells with or without NECA before cell lysis and solubilization of membranes for immunoprecipitation of A2aARs with antibody TP/2. After a 30-min agonist exposure, a 60-kDa phosphoprotein was immunoprecipitated by TP/2; immunoprecipitation of this protein was completely abolished by the inclusion of antigenic peptide in the immunoprecipitation reaction (Fig. 5A). Despite the presence of several nonspecific bands in the immunoprecipitation, only the 60-kDa protein exhibited the necessary properties of the A2aAR. First, phosphorylation was observed only in transfected cells (Fig. 5A). Second, the precipitated protein had the same molecular mass as the expressed A2aAR. Finally, immunoprecipitation of this protein was completely abolished by the inclusion of antigenic peptide, whereas the labeling of the other bands was merely altered with the background labeling. The increased background labeling observed in lanes containing immunoprecipitated receptors is commonly observed when low abundance, phosphorylated, transmembrane receptors are enriched by either immunoprecipitation or purification by column chromatography (42, 43).

Fig. 5.

Agonist-stimulated in vivo phosphorylation of the A2aAR. A, Either untransfected (CHO) or A2aAR-transfected (CHO-A2aAR) cells were incubated with [32P]orthophosphate and ADA for 2.5 hr before the addition of fresh ADA alone (control) or with NECA to a final concentration of 10 μM for 30 min at 37°. Membranes were then prepared for solubilization and immunoprecipitation with 20 μMg/ml affinity-purified TP/2, in the absence or presence of antigenic peptide, as described in Experimental Procedures. B, CHO-A2aAR cells were preincubated with [32P]orthophosphate, as described for A, before incubation with 10 μM forskolin or 0.1 % ethanol vehicle and immunoprecipitation as described.

Treatment of CHO-A2aAR cells with 10 μM forskolin before solubilization and immunoprecipitation failed to stimulate the phosphorylation of the A2aAR (Fig. 5B). This is consistent with the lack of consensus sites for PKA phosphorylation (4) and also eliminates the possibility that PKA indirectly mediates A2aAR phosphorylation via activation of other kinases.

Effects of cAMP generation and PKC activation on A2aAR responsiveness

To determine whether cAMP generation was responsible for either the rapid onset of desensitization or the long term reduction in responsiveness, cells were treated for 30 min or 24 hr with either 10 μM forskolin or 0.1% ethanol vehicle (Table 3). Treatment of cells with these compounds reduced neither the efficacy nor the potency with which NECA was capable of stimulating adenylyl cyclase activity in isolated membranes. Moreover, reducing the Mg2+ concentration in the adenylyl cyclase assay by 10-fold, to detect subtle changes in receptor-G protein coupling, failed to unmask any cAMP-mediated reduction in A2aAR function (Table 3). Similarly, 30-min exposure of CHO-A2aAR cells to 1 μM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, a potent activator of PKC enzymes, did not result in a consistent reduction in A2aAR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity under either assay condition, despite the presence of consensus PKC phosphorylation sites on the A2aAR (Table 3). Hence, in this system, activation of either PKA or PKC could not account for the observed desensitization.

TABLE 3. Effects of PKA and PKC activation on A2aAR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity.

Cells were treated for either 30 min or 24 hr in the presence of 0.3 unit/ml ADA and either 10 μM forskolin or 0.1% (v/v) ethanol vehicle (control). Cells were also treated for 30 min with ADA and either 1 μM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or 1 μM 4α-phorbol, an inactive phorbol ester (PKC control). Membranes were then prepared for assay of adenylyl cyclase activity in the absence or presence of 10 μM NECA, with MgCl2 present at final concentrations of either 10 mM (high [Mg2+]) or 1 mM (low [Mg2+]), as described in Experimental Procedures. Data are presented as means ± standard errors for three experiments.

| 30 min | 24 hr | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| High [Mg2+] | Low [Mg2+] | High [Mg2+] | Low [Mg2+] | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Stimulationa | EC50 | Stimulation | EC50 | Stimulation | EC50 | Stimulation | EC50 | |

| Fold | μM | fold | μM | fold | μM | fold | μM | |

| Control | 8.7 ± 0.6 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 11.6 ± 0.2 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

| 10 μM Forskolin | 9.7 ± 0.7 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 11.2 ± 0.2 | 0.40 ± 0.11 | 11.5 ± 1.3 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 0.50 ±0.12 |

| PKC control | 8.3 ± 1.2 | —b | 14.3 ± 0.5 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1 μM PMA | 8.1 ± 1.1 | — | 15.9 ± 0.5 | — | — | — | — | — |

Stimulation above basal.

—, not determined.

Recovery of A2aAR function after long term desensitization

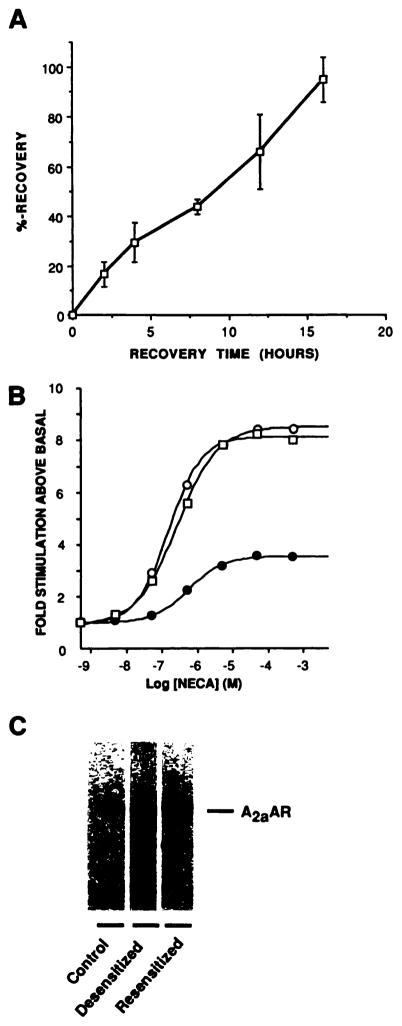

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1A, long term exposure to agonist resulted in only a slightly greater inhibition of A2aAR function, compared with that observed after 30 min. However, after 24-hr exposure to 10 μM NECA, removal of agonist resulted in a much slower recovery of adenylyl cyclase responsiveness, which occurred over a period of several hours (Fig. 6A); analysis of NECA dose-response curves after 16 hr of recovery in agonist-free medium showed that both the efficacy and potency of the adenylyl cyclase response were restored (Fig. 6B). Immunoblotting of membranes demonstrated that recovery of the adenylyl cyclase response was associated with a complete recovery of receptor levels, suggesting that the two phenomena are related (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Recovery of A2aAR function after long term desensitization. CHO-A2aAR cells were either exposed for 24 hr at 37° to 0.3 unit/ml ADA in the absence or presence of 10 μM NECA or exposed for 24 hr to 10 μM NECA and 0.3 unit/ml ADA before extensive washing with PBS, addition of agonist-free medium containing 0.3 unit/ml ADA, and further incubation at 37° for the indicated times. Membranes were then prepared simultaneously for assay of adenylyl cyclase activity, as described in Experimental Procedures. A, Time course of recovery of the 10 μM NECA-stimulated adenylyl cyclase response in isolated CHO-A2aAR cell membranes after 24-hr desensitization. Data are pooled from four experiments, with each data point representing the mean ± standard error of three determinations. B, Dose-response curves for NECA-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in membranes from ADA-treated controls (○), 24-hr desensitized cells (●), or 24-hr desensitized cells allowed to recover in agonist-free medium for 16 hr (□). The EC50 values for NECA in this experiment were 0.28 μM (control), 0.56 μM (desensitized), and 0.33 μM (resensitized). This experiment is one of two performed, which produced identical results. C, Resensitization detected by immunoblotting. CHO-A2aAR cells were treated as described in B and subjected to immunoblotting with affinity-purified TP/2 as described in Experimental Procedures. In this experiment, agonist treatment down-regulated receptors to 28% of the control level. Subsequent recovery in the absence of agonist increased receptor levels to 110% of the control value. This is one of three immunoblots performed.

Quantitation of G protein subunits in membranes from control and desensitized cells

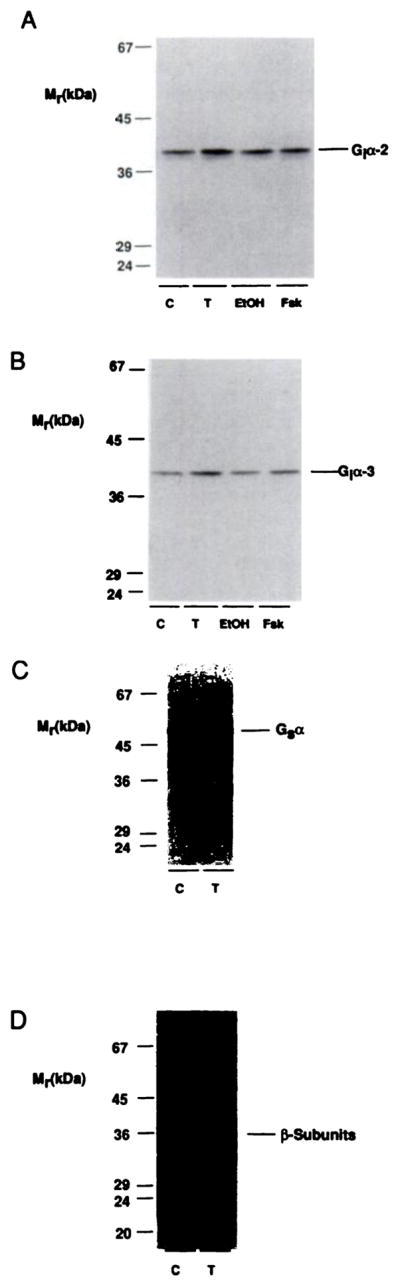

One possible mode of regulation whose importance in the desensitization process has been demonstrated in other systems involves regulation of the quantity of G protein subunits (14–17). Therefore, comparative immunoblotting experiments were performed using membranes from cells that had been treated in the presence or absence of 10 μM NECA for 24 hr (Fig. 7; Table 4). Immunoblotting with antisera specific for Giα2 or Giα3 demonstrated that long term exposure to agonist was associated with increased levels of both of these proteins in membranes from transfected cells (Fig. 7, A and B; Table 4). Long term agonist exposure did not consistently alter the expression of Gs. α or β subunits (Fig. 7, C and D; Table 4). Interestingly, the ability of NECA to increase expression of these proteins was not solely due to its ability to elevate intracellular cAMP levels, because parallel treatment with 10 μM forskolin did not significantly alter the expression of either Gi α subunit (<10% difference, compared with controls, in three experiments) (Fig. 7, A and B). Similar treatment with 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP also failed to increase expression of Gi α subunits (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Regulation of G protein subunits after long term desensitization. CHO-A2aAR cells were treated with 0.3 unit/ml ADA alone (C) or with 10 μM NECA (T), 10 μM forskolin (Fsk), or 0.1% (v/v) ethanol vehicle (ETOH), for 24 hr at 37°. Membranes were then prepared for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the antisera described in Experimental Procedures for detection of Giα2 (A), Giα3 (B), Gsα (C), and β (D) subunits. For A and B, 100 μg of membrane protein were loaded in each lane; for C and D, 75 μg were used in each lane. These are representative comparisons; composite data from several experiments are given in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Expression of G protein subunits in membranes prepared from cells after long term agonist exposure.

CHO-A2aAR cells were treated with 0.3 unit/ml ADA in the absence (control) or presence of 10 μM NECA for 24 hr. Membrane preparations were then subjected to immunoblotting with the primary antibodies described in Experimental Procedures. The results are expressed as means ± standard errors for n experiments.

| G protein subunit | Expression | n |

|---|---|---|

| % of control | ||

| Gsα | 115 ± 12 | 4 |

| Giα2 | 162 ± 30a | 5 |

| Giα3 | 161 ± 28a | 5 |

| β subunits | 90 ± 10 | 4 |

Significantly different from control value (p < 0.05).

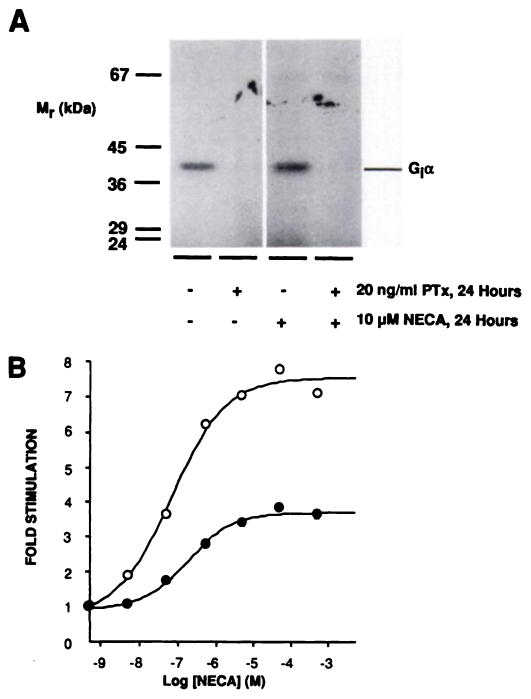

Therefore, to ascertain whether functional Gi activity is necessary to observe A2aAR desensitization, cells were treated for 24 hr with or without agonist, in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml PTx to catalyze the ADP-ribosylation and inactivation of Gi α subunits (Fig. 8A). However, treatment with PTx did not alter the desensitization pattern observed, suggesting that the elevated expression of Giα2 and Giα3 is not directly involved in mediating long term desensitization; the response to 10 μM NECA after 24-hr agonist treatment was reduced to 41 ± 11% (PTx treated) or 50 ± 14% (untreated) of controls (set at 100%) (three experiments) (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Effect of PTx treatment on A2aAR desensitization. CHO-A2aAR cells were treated for 24 hr at 37° with or without 10 μM NECA, in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml PTx, before membrane preparation as described in Experimental Procedures. A, After treatment of CHO-A2aAR cells with or without PTx, 30 μg of membranes from control and 24-hr 10 μM NECA-treated cells were subjected to PTx-catalyzed [32P]ADP-ribosylation in vitro and labeled proteins were visualized by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Using this approach, it was estimated that >90% of G, α subunits were ADP-ribosylated by a 24-hr incubation with 20 ng/ml PTx. B, Dose dependence of NECA-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in membranes prepared from cells treated with 20 ng/ml PTx and 0.3 unit/ml ADA in the absence (○) or presence (●) of 10 μM NECA for 24 hr at 37°. This is one of three quantitatively similar experiments.

Discussion

The isolation of a cDNA clone for the canine A2aAR has facilitated the generation of stable cell lines expressing this protein in the absence of any other A2ARs, thereby providing an ideal system to examine the roles of different processes in mediating the functional desensitization of the A2aAR. As with any study utilizing expression of a ‘foreign’ receptor in a cell type in which the receptor is naturally deficient, any phenomena observed should serve as a basis from which to determine the desensitization mechanisms used by cells expressing the receptor endogenously.

Treatment of A2aAR-transfected cells with agonist induced a rapid reduction in NECA-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in subsequently isolated membranes. After 30 min of agonist exposure, the reduced A2aAR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity was not accompanied by any diminution in stimulation mediated by sodium fluoride or forskolin, suggesting that the functioning of Ga and the catalytic unit of adenylyl cyclase was unaffected by the desensitization process. These data are consistent with the ‘homologous’ nature of A2aAR desensitization previously reported in rat kidney cells (18), smooth muscle cells from rat aorta (19), NG108–15 cells (21), and DDT1 MF-2 cells (20) and support a model whereby desensitization selectively diminishes A2aAR-Ga interaction. Furthermore, agonist radioligand binding studies demonstrated that a 30-min agonist treatment induced formation of a receptor population that bound agonist with reduced affinity, without altering the maximal A2aAR binding capacity. Because agonists bind with higher affinity to receptors that are coupled to their appropriate G protein, the shift of the whole population of receptors to lower affinity suggested that, whereas the number of A2aAR-Ga complexes was not altered, the efficiency of the A2aAR-Ga interaction was reduced. Inhibition of receptor sequestration did not affect the ability of the A2aAR functional response to desensitize, suggesting that internalization of the receptor was not responsible for the observed desensitization. It was therefore possible that the receptor protein was modified such that its ability to interact with Ga was impaired Consistent with this hypothesis was the finding that the ability of NECA to induce short term desensitization was associated with the agonist-stimulated phosphorylation of immunoprecipitable A2aARs. Neither receptor phosphorylation nor desensitization could be mimicked by elevation of intracellular cAMP levels alone, although it is possible that simultaneous elevation of cAMP levels and agonist occupation of receptors are required for these effects to be manifested.

By analogy with other G protein-coupled receptor systems, including rhodopsin and the α2A- and β2-adrenergic receptors (42, 44), we suggest that the observed agonist-induced phosphorylation of the A2aAR may be responsible for the rapid loss of receptor function. The inability of PKA activation alone to induce desensitization and receptor phosphorylation might suggest that a receptor-specific kinase analogous or identical to the βARK enzymes may be responsible (45). This is also suggested by secondary structural comparisons between the A2aAR, the β2-adrenergic receptor, and rhodopsin. Each of these receptors has a cytoplasmic carboxyl-terminal domain containing many serine and threonine residues in an acidic milieu, which studies using peptide substrates have shown to be an important factor in determining susceptibility to phosphorylation by βARK (46).

The ability of sucrose pretreament to inhibit both A2aAR sequestration and the rapid recovery normally observed after short term agonist exposure is consistent with the results of similar studies performed with the human β2-adrenergic receptor in CHO cells (37). Taken together with work on β-adrenergic receptors in frog erythrocytes (47), this suggested that sequestration of receptors may provide the means by which phosphorylated receptors may be concentrated in phosphatase-enriched vesicles for dephosphorylation and recycling back to the plasma membrane. Inhibition of this process before agonist exposure would therefore result in an accumulation of phosphorylated receptors that could not be dephosphorylated after agonist removal (37). In the case of the A2aAR, it remains to be proven whether the phosphorylation of the receptor is indeed responsible for the agonist-stimulated diminution in signaling capacity of the A2aAR, although the similarity between our data and those reported in Ref. 37 might suggest that similar processes occur.

Long term treatment of CHO-A2aAR cells with elevated concentrations of NECA for up to 24 hr produced a slightly larger reduction in A2aAR function, compared with that seen at 30 min. However, unlike the short term desensitization process, this second phase of A2aAR desensitization was associated with a dose- and time-dependent reduction in the levels of immunoreactive A2aARs and, by 24 hr, a reduction in the total number of agonist binding sites, as measured with [3H] CGS21680. Moreover, unlike reversal from short term agonist treatment, recovery from desensitization caused by long term agonist exposure occurred over a period of several hours, rather than a few minutes, further suggesting that the desensitization mechanisms operative at 30 min and 24 hr are distinct. Like short term desensitization, adenylyl cyclase activation by fluoride and forskolin was unaffected, suggesting a defect at the level of the A2aAR-Ga interaction. Interestingly, the reduced affinity of the A2aAR for [3H]CGS21680 observed after 30-min agonist exposure, which was associated with receptor phosphorylation, persisted after 24 hr. However, at the latter time point receptor down-regulation appeared to be the dominant mechanism, because recovery after long term agonist exposure occurred over several hours, rather than the few minutes necessary after short term treatment. Nevertheless, the disparity between the NECA dose dependencies for receptor down-regulation and desensitization is most likely due to the fact that multiple mechanisms appear to be responsible for desensitization, such that when certain mechanisms are not fully manifested (e.g., down-regulation) the contribution of others may be sufficient to induce maximal desensitization. In this regard, receptor sequestration, although not involved at early time points, may play an increasingly significant role as total receptor number decreases. However, this phenomenon is difficult to investigate, because treatment for long periods with inhibitors of sequestration adversely affects adenylyl cyclase responsiveness in these cells (40). It was also for these reasons that we could not determine whether receptor sequestration was required to observe down-regulation; more elegant cell biological studies involving immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopic techniques will be necessary to answer this question.

The difference in the extent of receptor down-regulation as determined by agonist binding versus immunoblotting is not entirely unexpected. Previous studies on α2- and β-adrenergic receptor subtypes have similarly produced anomalous results when comparing agonist and antagonist binding (48, 49). Hence, whereas the β-adrenergic receptor agonist hydroxybenzylisoproterenol is a full agonist capable of completely and competitively blocking antagonist binding, saturating concentrations of [3H]hydroxybenzylisoproterenol recognize only 60% of the receptor complement identified in antagonist binding studies (48). An analogous situation may be occurring in transfected CHO cells, with [3H]CGS21680 being capable of identifying only a fraction of the total number of A2aARs expressed. Therefore, the extent of down-regulation measured by agonist binding may underestimate the total quantity lost. Alternatively, it is possible that a desensitization-induced conformational change in the A2aAR diminishes the immunoreactivity of the receptor with the antibody. This would be unlikely, however, because the membranes are solubilized and electrophoresed under denaturing conditions. The resolution of these questions awaits the development of a selective, high affinity, radiolabeled, A2aAR antagonist.

An interesting phenomenon associated with long term A2aAR desensitization was the agonist-dependent up-regulation of Giα2 and Giα3. These changes in G protein expression did not directly affect the ability of either fluoride or forskolin to stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity under conditions in which the A2aAR was desensitized. Also, treatment with PTx to inactivate Gi proteins during agonist treatment did not diminish the agonist-induced desensitization observed. Nevertheless, increased expression of Gi α subunits provides a potential mechanism by which the A2aAR can modulate the signaling capacity of receptors coupled to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity; analogous cross-regulation of the stimulatory and inhibitory pathways of adenylyl cyclase has been described by us (15) and others (17) in various model systems. Attempts to directly determine whether the increased expression of Gi α subunits enhanced their ability to inhibit adenylyl cyclase were unsuccessful, because we could not measure any detectable inhibition of forskolin-stimulated activity by either GTP or nonhydrolyzable analogues (data not shown). Therefore it seems that, in the absence of an activated Gi-coupled receptor, “tonic,” GTP-dependent, receptor-independent functioning of Gi in CHO cells is very low, unlike in adipocytes, where it is readily observed under our assay conditions (50). This would also explain why we did not observe a decrease in fluoride- or forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity after long term agonist treatment.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated for the first time that multiple, temporally distinct, processes are associated with the phenomenon of A2aAR desensitization. Short term agonist exposure causes a rapid impairment of the receptor/G protein interaction, leading to reduced A2aAR-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity. This is associated with reduced affinity of the receptor for agonist, receptor phosphorylation, and sequestration of receptors into a light vesicle population. Long term treatment leads to receptor down-regulation, recovery from which takes several hours, and the elevated expression of inhibitory G protein α subunits, which could potentially modulate the functioning of receptors coupled to other signal transduction pathways.

Acknowledgments

G.L.S. was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Specialized Center for Organized Research Grant P50-HL17670 in Ischemic Disease, in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1-HL35134 and Supplement, and by Grant-in-Aid 91008200 from the American Heart Association. T.W.G. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK42486.

The authors would like to thank Drs. Vickram Ramkumar, Mark Olah, and John Raymond for helpful discussions and Linda Scherich for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

adenosine receptor

- ADA

adenosine deaminase

- βARK

β-adrenergic receptor kinase

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- PIA

phenylisopropyladenosine

- PAPA-APEC

(−)-N6-[(R)-1-methyl-2-phenylethyl] adenosine

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PTx

pertussis toxin

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

References

- 1.Olsson RA, Pearson D. Cardiovascular purinoceptors. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:761–846. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiles GL. Adenosine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6451–6454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou QY, Li C, Olah ME, Johnson RA, Stiles GL, Civelli O. Molecular cloning and characterization of an adenosine receptor: the A3 adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7432–7436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Galen PJM, Stiles GL, Michaels GS, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A1 and A2 receptors: structure and function relationships. Med Res Rev. 1992;12:423–471. doi: 10.1002/med.2610120502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohlman HG, Thorner J, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Model systems for the study of seven-transmembrane-segment receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:653–688. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.003253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruns RF, Lu GH, Pugsley TA. Characterization of the A2 adenosine receptor labelled by [3H]NECA in rat striatum membranes. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:331–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stehle JH, Rivkees SA, Lee JJ, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. Molecular cloning and expression of the cDNA for a novel A2-adenosine receptor subtype. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:384–393. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.3.1584214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furlong TJ, Pierce KD, Selbie LA, Shine J. Molecular characterization of a human brain A2 adenosine receptor. Mol Brain Res. 1992;15:62–66. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohse MJ, Andexinger S, Pitcher J, Trukawinski S, Codina J, Faure JP, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Receptor desensitization with purified proteins: kinase dependence and receptor specificity of β-arrestin and arrestin in the β2-adrenergic receptor and rhodopsin systems. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8558–8564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto T, Murayama Y, Hayashi Y, Inagaki M, Ogata E, Nishimoto I. Identification of a Gs-activator region of the β2-adrenergic receptor that is autoregulated via protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation. Cell. 1991;67:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harden TK, Cotton CU, Waldo GL, Lutton JK, Perkins JP. Catecholamine-induced alteration in sedimentation behavior of membrane-bound β-adrenergic receptors. Science (Washington D C) 1980;210:441–443. doi: 10.1126/science.6254143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lohse MJ, Benovic JL, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Multiple pathways of rapid β2-adrenergic receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3202–3209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green A, Milligan G, Dobias S. Gi down-regulation as a mechanism for heterologous desensitization in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3223–3229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenzie FR, Milligan G. Prostaglandin E1-mediated cyclic AMP-independent down-regulation of Gsα in neuroblastoma × glioma hybrid cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17084–17093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longabaugh JP, Didsbury J, Spiegel A, Stiles GL. Modification of the rat A1 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase during chronic exposure to an adenosine receptor agonist. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:681–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadcock JR, Port JD, Malbon CC. Cross-regulation between G protein-mediated pathways: activation of the inhibitory pathway of adenylyl cyclase increases the expression of β2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11915–11922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadcock JR, Ros M, Watkins DC, Malbon CC. Cross-regulation between G protein-mediated pathways: stimulation of adenylyl cyclase increases expression of the inhibitory G protein Giα2. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14784–14790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman ME, Levitzki A. Desensitization of normal rat kidney cells to adenosine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand-Srivastava MB, Cantin M, Ballak M, Picard S. Desensitization of the stimulatory A2 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase system in vascular smooth muscle cells from rat aorta. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1989;62:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(89)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramkumar V, Olah ME, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Distinct pathways of desensitization of A1- and A2-adenosine receptors in DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;40:639–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenimer JG, Nirenberg M. Desensitization of adenylate cyclase to prostaglandin E1 and 2-chloroadenosine. Mol Pharmacol. 1981;20:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer TM, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Immunological identification of A2 adenosine receptors by two polyclonal antibody preparations. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:391–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maenhaut C, Van Sande J, Libert F, Abramowicz M, Parmentier M, Vanderhaegen JJ, Dumont JE, Vassart G, Schiffmann S. RDC8 encodes for an adenosine A2 receptor with physiological constitutive activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen BR. Use of eukaryotic expression technology in the functional analysis of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:684–704. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanoff C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. The A2 adenosine receptor: guanine nucleotide modulation of agonist binding is enhanced by proteolysis. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;39:130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Glycoprotein nature of the A2 adenosine receptor binding subunit. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:177–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salomon Y, Londos C, Rodbell M. A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal Biochem. 1974;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (Lond) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raymond JR, Olsen CL, Gettys TW. Cell-specific physical and functional coupling of human 5HT1A receptors to inhibitory G protein α-subunits and lack of coupling to Gsα. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11064–11073. doi: 10.1021/bi00092a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simonds WF, Goldsmith PK, Woodward CJ, Unson CG, Spiegel AM. Receptor and effector interactions of Gs: functional studies with antibodies to the αs carboxyl-terminal decapeptide. FEBS Lett. 1989;249:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribeiro-Neto F, Mattera R, Grenet D, Sekura RD, Birnbaumer L, Field JB. ADP-ribosylation of G proteins by pertussis and cholera toxins in isolated membranes: different requirements for and effects of guanine nucleotides and Mg2+ Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1:472–481. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-7-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scatchard G. The attractions of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1949;51:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLean A, Hancock AA, Lefkowitz RJ. Validation and statistical analysis of a computer modelling method for quantitative analysis of radioligand binding data for mixtures of pharmacological receptor subtypes. Mol Pharmacol. 1982;21:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanoff C, Stiles GL. Solubilization and characterization of the A2 adenosine receptor. J Recept Res. 1993;13:961–973. doi: 10.3109/10799899309073703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hide H, Padgett WL, Jacobson KA, Daly JW. A2a adenosine receptors from rat striatum and rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells: characterization with radioligand binding and activation of adenylate cyclase. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu SS, Lefkowitz RJ, Hausdorff WP. β-Adrenergic receptor sequestration: a potential mechanism of receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. Ligand-regulated internalization and recycling of the human β2-adrenergic receptor between the plasma membranes and endosomes containing transferrin receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassis S, Sullivan M. Desensitization of the mammalian β-adrenergic receptor: analysis of receptor distribution on non-linear sucrose gradients. J Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 1986;11:35–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eason MG, Liggett SB. Subtype-selective desensitization of α2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25473–25479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez MC, Xie YB, Wang H, Collison K, Segaloff DL. Effects of truncations of the cytoplasmic tail of the luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor on receptor-mediated hormone internalization. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:327–336. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.3.1316539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouvier M, Hausdorff WP, De Blasi A, O’Dowd BF, Kobilka BK, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Removal of phosphorylation sites from the β2-adrenergic receptor delays the onset of agonist-promoted desensitization. Nature (Lond) 1988;333:370–373. doi: 10.1038/333370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobin AB, Nahorski SR. Rapid agonist-mediated phosphorylation of m3-muscarinic receptors revealed by immunoprecipitation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9817–9823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liggett SB, Ostrowski J, Chesnut LC, Kurose H, Raymond JR, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Sites in the third intracellular loop of the α2A-adrenergic receptor confer short-term desensitization: evidence for a receptor kinase-mediated mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4740–4746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hausdorff WP, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Turning off the signal: desensitization of β-adrenergic receptor function. FASEB J. 1990;4:2881–2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Onorato JJ, Palczewski K, Regan JR, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Benovic JL. Role of acidic amino acids in peptide substrates of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase and rhodopsin kinase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5118–5125. doi: 10.1021/bi00235a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sibley DR, Strasser RH, Benovic JL, Daniel K, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the β-adrenergic receptor regulates its functional coupling to adenylate cyclase and its subcellular distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9408–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wessels M, Mullikin D, Lefkowitz RJ. Differences between agonist and antagonist binding following β-adrenergic receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3371–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kahn DJ, Mitrius JC, Uprichard DC. Alpha2-adrenergic receptors in neuroblastoma × glioma hybrid cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1982;21:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parsons WJ, Ramkumar V, Stiles GL. The new cardiotonic agent sulmazole is an A1 adenosine receptor antagonist and functionally blocks the inhibitory regulator Gi. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;33:441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]