Abstract

Ion-mediated interaction between DNAs is essential for DNA condensation, and it is generally believed that monovalent and nonspecifically binding divalent cations cannot induce the aggregation of double-stranded (ds) DNAs. Interestingly, recent experiments found that alkaline earth metal ions such as Mg2+ can induce the aggregation of triple-stranded (ts) DNAs, although there is still a lack of deep understanding of the surprising findings at the microscopic level. In this work, we employed all-atom dynamic simulations to directly calculate the potentials of mean force (PMFs) between tsDNAs, between dsDNAs, and between tsDNA and dsDNA in Mg2+ solutions. Our calculations show that the PMF between tsDNAs is apparently attractive and becomes more strongly attractive at higher [Mg2+], although the PMF between dsDNAs cannot become apparently attractive even at high [Mg2+]. Our analyses show that Mg2+ internally binds into grooves and externally binds to phosphate groups for both tsDNA and dsDNA, whereas the external binding of Mg2+ is much stronger for tsDNA. Such stronger external binding of Mg2+ for tsDNA favors more apparent ion-bridging between helices than for dsDNA. Furthermore, our analyses illustrate that bridging ions, as a special part of external binding ions, are tightly and positively coupled to ion-mediated attraction between DNAs.

Introduction

Nucleic acids are highly charged polyanionic biopolymers, and their collapse into compact state would experience very strong Coulomb repulsion (1). By interaction with polycations such as cationic protein and polyamines, DNAs can be tightly packaged inside cell nucleus, bacterial cytoplasm, and viral capsids (2, 3). In solutions, cations can bind to nucleic acids to reduce and modulate the repulsion between nucleic acid segments. Therefore, cations play an important role in the condensation and assembly of nucleic acids (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Extensive experiments have shown that cations with valence ≥3 can effectively condense double-stranded (ds) DNAs at millimolar ion concentrations (4, 5, 8), whereas monovalent ions and nonspecifically binding divalent ions such as Mg2+ generally cannot condense dsDNAs even at molar ion concentrations (2, 5, 9). The multivalent ion-mediated effective attraction has been proposed to be responsible for the condensation of DNAs and other like-charged polyelectrolytes (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18). However, recent experiments have shown that the multivalent ion-mediated condensation of nucleic acids is far beyond what has been known (19, 20). First, recent UV absorption and small-angle x-ray scattering experiments have shown that cobalt hexamines can induce the aggregation of B-form dsDNAs although they cannot cause the aggregation of A-form dsRNAs (19). Second, recent small-angle x-ray scattering and osmotic stress experiments have shown that alkaline earth divalent ions cannot lead to the aggregation of dsDNAs, although they can cause the aggregation of triple-stranded (ts) DNAs (20).

Some polyelectrolyte theories and models have been developed and employed to understand or predict ion-mediated interactions between DNA helices (4, 5, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32). The counterion condensation theory is a successful double-limiting law, although it always predicts an effective attraction between dsDNAs even at a low monovalent salt (21, 22). The Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) theory is rather successful for predicting electrostatic properties of biopolymers in aqueous/monovalent salt solutions (23, 24, 25, 26, 27), although the theory always predicts an effective repulsion between dsDNAs due to the ignorance of ion-ion correlations. The tightly bound ion model can predict an ion-mediated effective attraction between dsDNAs, but this model ignores the realistic molecular charge distribution on atoms and may not make reliable predictions about detailed ion-binding near the DNA surface (28, 29, 30). To understand the recent experiments on the aggregation of dsDNAs and dsRNAs in cobalt hexamine solutions (19) and on the aggregation of dsDNAs and tsDNAs in alkaline earth divalent ion solutions (20), the electrostatic zipper model was extended. This model makes predictions in qualitative accordance with the experiments (31, 32), whereas the partition of binding ions into the minor/major grooves in the model is from the preset parameters (32). Besides the theoretical models, computer simulations can be considered as an effective tool to probe structural dynamics and ion effects for biomolecules (33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44). Very recently, the puzzling lack of dsRNA condensation was explained in Tolokh et al. (45), based on all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and the different ion-binding modes (called external binding and internal binding) to dsDNAs and dsRNAs were proposed to be responsible for the different condensation behaviors of dsDNAs and dsRNAs in cobalt hexamine solutions (45). Furthermore, all-atom MD simulations were employed to directly calculate the cobalt hexamine-mediated interactions between two dsDNAs and between two dsRNAs (46). The external binding of multivalent ions (e.g., cobalt hexamine or spermine) to dsDNA favors the ion bridge between adjacent helices and an effective attraction between dsDNAs, whereas multivalent ions internally bind to dsRNA and cannot form apparent ion bridges at millimolar concentrations (45, 46, 47, 48).

However, there is still a lack of deep understanding on why alkaline earth ions such as Mg2+ can condense tsDNAs although they cannot condense dsDNAs. Unlike dsDNA, a tsDNA is formed by a third strand binding into the major groove of dsDNA via Hoogsteen (or reverse Hoogsteen) basepairing (49), and its charge density and structure are different from dsDNA to dsRNA. Therefore, tsDNA is a good structure model to study the mechanism of DNA condensation. Moreover, it is known that tsDNA participates in diverse biological functions such as gene regulation and DNA repair (50, 51), and may play a role in modulating the chromosome conformation in eukaryotic genomes (52). Furthermore, there is also a need for direct illustration of the relationship between bridging ions and the effective force between DNAs.

In this work, we employed all-atom MD simulations to directly calculate the potentials of mean force (PMFs) between tsDNAs, between dsDNAs, and between dsDNA and tsDNA in Mg2+ solutions. The Mg2+ distributions were analyzed in detail and direct comparisons were made between our calculations and the corresponding experimental measurements (20, 53). This work illustrates why Mg2+ can condense tsDNAs although it cannot condense dsDNAs at the microscopic level, and provides a direct illustration of the correlation between bridging Mg2+ ions and the effective attraction between tsDNAs.

Materials and Methods

All-atom MD simulations

In this work, we calculated the PMFs between dsDNAs (dsDNA-dsDNA), between tsDNAs (tsDNA-tsDNA), and between tsDNA and dsDNA (tsDNA-dsDNA) by all-atom MD simulations. The dsDNA and tsDNA are modeled as a 16-bp homopolymeric poly(dA):poly(dT) duplex in B-form and a poly(dT):poly(dA):poly(dT) triplex, which are built with Nucleic Acid Builder (54). The sequence for tsDNA was chosen according to the recent osmotic stress and small angle x-ray diffraction experiments (20), and the helical structure of tsDNA of a homo-sequence like poly(dT):poly(dA):poly(dT) can be constructed more conveniently than those of hetero-sequence (55). Correspondingly, the sequence of dsDNA was also taken as poly(dA):poly(dT). Specifically, the built tsDNA has an axial rise of 3.26 Å per residue and 12 residues per turn, and the structural parameters are taken from x-ray fiber diffraction (55); see the Supporting Material for details of building tsDNA. Because tsDNAs and dsDNAs were built in their respective standard forms, our calculations should not be affected essentially by the use of poly(dT):poly(dA):poly(dT) and poly(dA):poly(dT) strands.

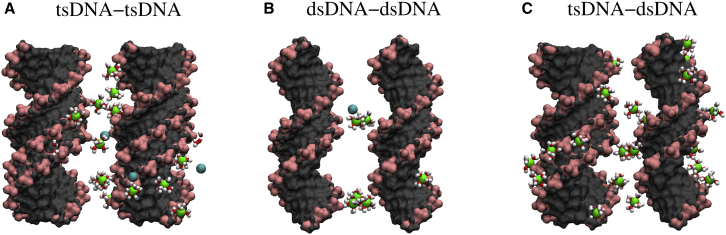

The two DNA helices with axes kept in the z direction were separated in the x direction and immersed in a cubic box containing explicit water and ions, as shown in Fig. 1. The DNAs were harmonically constrained with a force constant of 1000 kJ/(mol·nm2) in the z direction, and thus the DNAs were allowed to move in the x-y plane and kept in parallel with each other. The ions were added to the systems according to the reported concentrations (20 and 100 mM [Mg2+], respectively) (20, 53). We employed the Amber parmbsc0 force field for DNA and the TIP3P water model for the explicit solvent (56, 57). Simultaneously, we adopted the hydrated magnesium ion model (58) with ion-pair specific corrections to the LJ parameters (59), which has been shown to improve the predictions for the Mg2+-mediated DNA assembly (58, 60).

Figure 1.

An illustration for two parallel DNAs (tsDNA-tsDNA, dsDNA-dsDNA, and tsDNA-dsDNA) in MgCl2 solutions. Mg2+ ions are shown as green spheres and Cl− ions are shown as cyan spheres (only parts of the ions are shown). The pairs of short DNAs are restrained in the z direction, and a spring with a spring constant k, which connects the mass centers of the two helices has been added to calculate the potentials of mean force between DNAs. The DNA-DNA distance is defined as the distance between the mass centers of two DNAs, and the shown DNA-DNA distances are 30 (A), 29 (B), and 28 Å (C), respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

All the MD simulations were carried out with Gromacs 4.5 (61). The equilibrated systems of two (ds or ts) DNAs in MgCl2 solutions were obtained as follows: first, using our previously described protocol (46), an energy minimization of 5000 steps was performed with the steepest descent algorithm, and the systems were slowly heated to 298 K and equilibrated until 0.5 ns. Second, the subsequent NPT simulations of 2 ns (time-step 1 fs, P = 1 atm) were performed and the DNAs were fixed. Subsequently, the steered MD procedures were performed for umbrella sampling. Third, all our MD simulations were continued for another 100 ns in the isothermic-isobaric ensemble (time-step 2 fs, P = 1 atm, T = 298 K). Our MD simulations generally reached equilibrium after ∼10 ns, as shown in Fig. S2 for the number of ions around DNAs versus the MD running time. The MD trajectories in equilibrium are used to calculate the PMF between two DNAs, as described below.

Calculating PMF between DNAs

In this work, we employed umbrella sampling (62) with the pseudo-spring method (46, 63) to calculate the PMF between two DNAs. In the method, a pseudo-spring with spring constant k is added to link the mass centers of two DNAs. Based on the MD trajectories in equilibrium, the PMF ΔG between two DNAs can be calculated by (46, 63)

| (1) |

| (2) |

where F is the effective force between DNAs. Δx is the mean deviation of the spring length away from the original length x0 in equilibrium, and xref is the outer reference distance. In practice, the spring constant k is generally taken as 1000 kJ/(mol·nm2) and xref is taken as 40 Å. For the cases where two helices interact very strongly, we also use a higher spring constant of k = 2000 kJ/(mol·nm2). Furthermore, the MD data were used for calculating the PMFs with the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) (64), and the PMFs from the pseudo-spring method are very close to those from the WHAM method; see Figs. S3 and S4 for the PMFs and the technique details of the WHAM method. In the following, we used the DNA-DNA distance to denote the distance between the mass centers of two DNAs.

Continuum electrostatic calculations

For detailed analyses of the Mg2+-mediated PMFs between (ds and ts) DNAs, we also calculated the electrostatic potentials for the dsDNA and tsDNA in 20 mM MgCl2 solutions by solving the PB equation with the APBS software (65). The parameters employed for APBS are listed as follows: the grid spacing is 0.3 Å, the dielectric constants are two for DNAs and 78 for water, and the solvent probe radius is 2 Å. The surface electrostatic potentials are visualized with the VMD program (66).

Results and Discussion

In this work, we directly calculated the Mg2+-mediated PMFs between dsDNAs, between tsDNAs, and between dsDNA and tsDNA using all-atom MD simulations. We compared our calculations with the available experimental measurements (20, 53), and detailed analyses were carried out to reveal the microscopic mechanism for the distinctive difference in Mg2+-mediated PMFs between dsDNAs and tsDNAs. Furthermore, we provided a direct illustration of the tight and positive coupling between bridging ions and the ion-mediated attraction between DNAs.

PMFs between DNAs in Mg2+ solutions

PMFs between dsDNAs

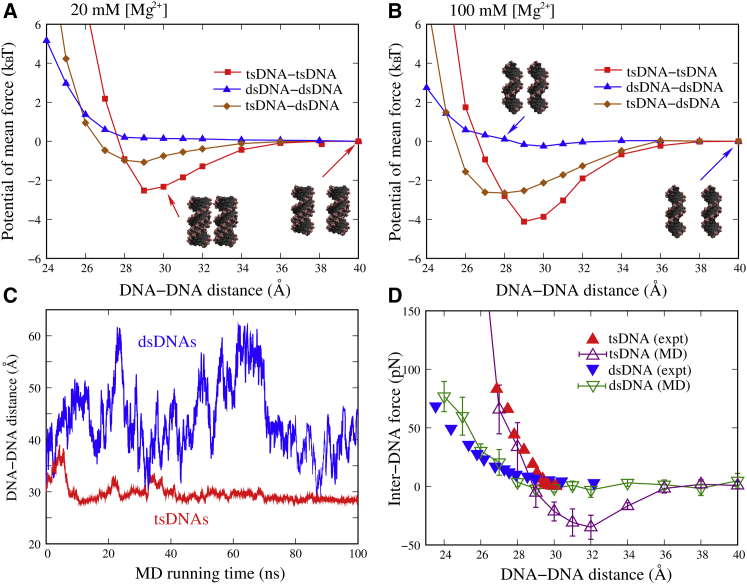

As shown in Fig. 2, the PMF between dsDNAs appears flat and is weakly repulsive at low (∼20 mM) [Mg2+]. When [Mg2+] is increased to ∼100 mM, the PMF between dsDNAs changes from a weak repulsion to a weak attraction. Such attraction is very slight (∼−0.02 kBT per bp at a DNA-DNA distance of ∼29 Å), and should be insufficient to induce the condensation of short dsDNAs. The weakly repulsive PMF between dsDNAs at ∼20 mM [Mg2+] is in accordance with our MD simulation for two unconstrained dsDNAs. As shown in Fig. 2 C, the two dsDNAs fluctuate across a wide DNA-DNA distance range rather than preferring to remain close to each other during the MD process. Our calculated PMFs between dsDNAs are also consistent with the experiments showing that alkaline earth metal ions cannot induce dsDNA condensation even at high ion concentrations (20, 67). The change in DNA sequence should not cause a strong attractive PMF between dsDNAs, because the A·T sequence used in our MD simulations has been shown to be most prone to multivalent ion-mediated attraction between dsDNAs (68). The role of Mg2+ in mediating effective interaction between dsDNAs has been attributed to its +2 charge, which is not high enough when bridging dsDNAs to cause a strong effective attraction (4, 5, 9, 69).

Figure 2.

The potentials of mean force between DNAs is given for three cases: tsDNA-tsDNA, dsDNA-dsDNA, and tsDNA-dsDNA in ∼20 (A) and in ∼100 mM Mg2+ solutions (B). (C) Shown here is the distance between the mass center of the DNAs versus the MD simulation time from the MD simulations for two tsDNAs (red) and two dsDNAs (blue) without the connection spring in a 20 mM Mg2+ solution. (D) The inter-DNA forces were calculated from our MD simulations and the experimental measurements on osmotic pressure. It should be noted here that the osmotic pressure experiment only gives the repulsive part of the forces between DNAs (20, 53). To see this figure in color, go online.

PMFs between tsDNAs

In contrast to dsDNAs in Mg2+ solutions, the PMF between tsDNAs is strongly attractive with the free energy minimum ∼−2.5 kBT (∼−1.48 kcal/mol) at a DNA-DNA distance of ∼29 Å for ∼20 mM [Mg2+], as shown in Fig. 2, A and B. When [Mg2+] is increased to ∼100 mM, the attractive PMF becomes stronger and the free energy minimum decreases to ∼−4.2 kBT (∼−2.45 kcal/mol). The strong attractive PMF between tsDNAs mediated by Mg2+ is confirmed by the MD simulation for two unconstrained tsDNAs. Fig. 2 C shows that two unconstrained tsDNAs prefer to fluctuate weakly around the DNA-DNA distance of ∼29 Å. The strong attractive PMF between tsDNAs implies that tsDNAs have apparently stronger condensation propensity in Mg2+ solutions than dsDNAs, which is in accordance with the recent experiments (20). In our simulations, the DNAs were constrained in parallel and not separated very far from each other. Actually, the condensation of DNAs would not only depend on the PMF between parallel DNAs, but also on DNA concentration (47), DNA length (47), and DNA end-to-end stacking interaction (70), which are related to translational entropy, rotational entropy, and end-to-end assembly for short DNAs (47, 70), respectively; see Tolokh et al. (47) for the details of evaluating condensation free energy of DNAs. Because our MD simulations allow the rotation of DNA around their axes, we can roughly examine the relative orientation of the DNAs around their axes at different DNA-DNA distances. At large DNA-DNA distance, there is no obvious orientational correlation between the two DNAs. When the DNA-DNA distance becomes small, the two DNAs are inclined to interlock in a groove-to-backbone conformation where bridging ions can efficiently bridge the adjacent phosphate strands in the two DNAs. A more detailed analysis on the orientational correlation between DNAs can be found in Yoo and Aksimentiev (60).

PMFs between dsDNA and tsDNA

It would be interesting to examine the PMF between dsDNA and tsDNA because the PMFs between dsDNAs and between tsDNAs are distinctively different. As shown in Fig. 2, the PMF between dsDNA and tsDNA is visibly attractive, and such effective attraction becomes stronger at higher [Mg2+]. The free energy minimum is ∼−1.5 kBT (∼−0.9 kcal/mol) at ∼20 mM [Mg2+] and becomes ∼−2.3 kBT (∼−1.3 kcal/mol) at ∼100 mM [Mg2+], suggesting that the attractive PMF between dsDNA and tsDNA is weaker (stronger) than that between tsDNAs (dsDNAs). The attractive PMF between tsDNA and dsDNA implies that dsDNAs-tsDNAs have a stronger condensation propensity than dsDNAs in Mg2+ solutions. Certainly, the obvious dsDNA-tsDNA condensation in Mg2+ solutions is still required to be measured experimentally to validate our findings here.

In the following, we made quantitative comparisons with the experimental measurements (20, 53). Based on the assumption that inter-DNA forces in a DNA aggregate are additive (60), the inter-DNA force for dsDNAs and tsDNAs can be approximately calculated from the experimental osmotic pressures Π (29, 60),

| (3) |

where d is the mean distance between two nearest neighbors in a DNA array, and h is the length of 16-bp dsDNA or tsDNA. As shown in Fig. 2 D, the calculated inter-DNA force between dsDNAs is weakly repulsive at ∼20 mM [Mg2+] and that between tsDNAs is strongly attractive, which agrees well with the experimental data (20, 53). Alternatively, we can also calculate the osmotic pressure for dsDNA and tsDNA arrays based on the additive assumption (29, 60), and make direct comparisons with the experimental measurements on osmotic pressures (20, 53). As shown in Fig. S5, the calculated osmotic pressures are in good agreement with the experimental data for both tsDNAs and dsDNAs. The slight deviation between the calculations (∼29 Å) and experiments (∼30 Å) may be attributed to the slight nonadditive effect at high divalent salts (10, 71), and it remains difficult in general to completely achieve a quantitative agreement between the calculations and experiments.

As described above, the experimental findings that Mg2+ cannot condense dsDNAs whereas it can condense tsDNAs is attributed to the Mg2+-mediated forces between dsDNAs and between tsDNAs (20, 72). The PMF between dsDNAs in a Mg2+ solution is repulsive (or very weakly attractive at high [Mg2+]), whereas the PMF between tsDNAs is strongly attractive. The question that follows is: why can Mg2+ ions cause an effective attraction for tsDNAs, although they cannot for dsDNAs?

Mg2+ distribution around DNA: triplex versus duplex

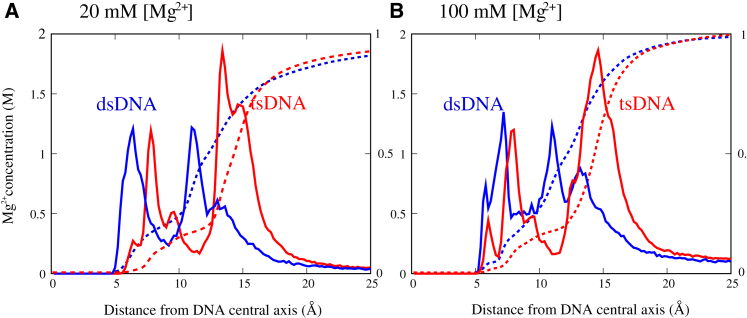

To understand the distinctively different roles of Mg2+ in mediating effective interactions between dsDNAs and between tsDNAs, we analyzed the Mg2+ distributions around dsDNA and around tsDNA, particularly given the different ion-binding modes between dsDNA and dsRNA (46, 47, 48). The cylindrical distributions c(r) values of Mg2+ around dsDNA and around tsDNA are calculated according to Wu et al. (46), where r is the axial distance from the helical axis. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, Mg2+ ions begin to bind at an axial distance of r ∼5 Å and prefer to accumulate in two distribution regions separated by an apparent local minimum for both dsDNA and tsDNA. The inner Mg2+-binding regions are in the axial distance ranges of 5 < r < 10 Å for dsDNA and 6 < r < 12 Å for tsDNA, which correspond to the ion binding into a groove. The outer Mg2+-binding regions are in the ranges of 10 < r < 14 Å for dsDNA and 12 < r < 17 Å for tsDNA, which correspond to the ion binding to phosphate groups. The ranges of the inner region and outer region for Mg2+-binding are slightly different for dsDNA and tsDNA, which is attributed to the larger helical radius of tsDNA than that of dsDNA (∼12.5 Å for tsDNA and ∼11 Å for dsDNA) (20). As suggested in the literature (46, 47, 48), the Mg2+-binding in the inner region is called the “internal binding Mg2+”, whereas that in the outer region is called the “external binding Mg2+”. Because the total number of ions binding to a DNA (per phosphate) is almost constant, the number of internal binding ions and the number of external binding ions are negatively coupled: the fewer (more) internal binding ions would correspond to the more (fewer) external binding ions. The internal binding ions of one DNA are generally separated from the other DNA by a large distance, and consequently make much less contribution to modulating the inter-DNA attractive force than an ion positioned between two DNAs. Thus a large ratio of external binding ions is generally more conducive to an effective attraction between two DNAs.

Figure 3.

(A and B) Shown here are the Mg2+ concentration distributions around DNA and the corresponding net charge distribution Q(r) per unit charge on the DNA molecules as functions of the radial distance r from the central axis of DNA. To avoid the end effect, the central full helix turn in the middle of the DNA is selected for the analyses. To see this figure in color, go online.

For dsDNA, the peak of c(r) for external binding Mg2+ has a similar height and width to that for internal binding. However, for tsDNA, the peak of c(r) for external binding Mg2+ is significantly higher and wider than that of internal binding. Our calculations further show that at ∼20 mM [Mg2+], the number of internal binding and external binding Mg2+ ions is 2.5 and 4.2 for the central full turn of dsDNA, and 2.6 and 8.1 for the central full turn of tsDNA, respectively. This indicates that the distinctive difference in Mg2+-binding between dsDNA and tsDNA is attributed to the preference for ion binding modes: for dsDNA, the internal binding of Mg2+ ions into the groove is only slightly weaker than the external binding to phosphate groups; however, for tsDNA, the external binding to phosphate groups is dominant over the internal binding into the groove. The strong external binding of ions would favor strong ion-bridging between DNAs to cause an apparently effective attraction, as suggested in recent studies (46, 47, 48). Therefore, the strong external binding of Mg2+ is responsible for the strong attraction between tsDNAs, whereas for dsDNA, the external binding of Mg2+ is relatively weak and consequently cannot induce an apparent attraction between dsDNAs. In addition, as shown in Fig. 3, A and B, when [Mg2+] increases from ∼20 to ∼100 mM, the external binding of Mg2+ becomes stronger for both tsDNAs and dsDNAs due to the lower binding penalty of ions. As a result, the PMF between tsDNAs becomes more attractive, and the PMF between dsDNAs can become weakly attractive at high [Mg2+], as described above.

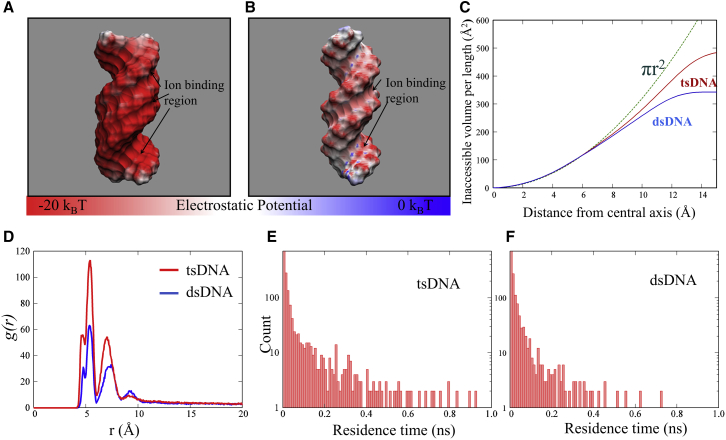

Why does Mg2+ bind to dsDNA and tsDNA in different ways? To understand the distinctively different ways that of Mg2+ binds to dsDNA and tsDNA, we examined the different structures of dsDNA and tsDNA as well as the electrostatic potential around them. As shown in Fig. 1 A, B-form dsDNA has a narrow minor groove (width ∼6 Å) and a wide major groove (width ∼12 Å), whereas for tsDNA, the binding of the third nucleotide strand into the major groove of the DNA duplex causes tsDNA to have three grooves: two of them are very narrow (∼3 and ∼4 Å) and one is slightly wide (∼9 Å). Here, the groove widths were calculated as the smallest separation distances between the P atoms in two strands minus 5.8 Å (approximately the sum of the van der Waals radii of two phosphate groups) (73). As a result, the accessible volume of ions in the grooves for tsDNA would be smaller than that for dsDNA, as shown in Fig. 4 C. The smaller ion-accessible volume in the grooves would cause Mg2+ binding to tsDNA to be slightly more external, than to dsDNA. More importantly, more strands in tsDNA can cause stronger electrostatic potential in the vicinity and different binding sites compared with dsDNA. We have calculated the electrostatic potential on the Mg2+-accessible surface for both tsDNA and dsDNA with the PB solver of APBS (65), although the PB theory may not capture some details in the vicinity of DNA surface (74). As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, a dsDNA has two kinds of preferential sites for ion binding: N7 atoms in the wide major groove and phosphate groups at the narrow minor groove. In contrast, for tsDNA, the most preferential binding sites for Mg2+ ions are phosphate groups at the two very narrow grooves, and the binding into the slightly wide groove is the next preferential binding site. Therefore, for dsDNA, the internal binding (into the major groove) and external binding to phosphate groups (at the minor groove) are both favorable, which is in accordance with the cylindrical distribution of Mg2+ around dsDNA. However, for tsDNA, the external binding (to phosphate groups at two narrow grooves) is dominant over internal binding (into the slightly wide groove), corresponding to the Mg2+ distribution around tsDNA in Fig. 3. Furthermore, Fig. 4 shows that the surface electrostatic potential of tsDNA is apparently stronger than that of dsDNA, which would cause stronger and tighter binding of Mg2+; see also Fig. 4, D–F.

Figure 4.

(A and B) Given here is the electrostatic potential at the hydrated Mg2+ accessible surface of tsDNA and dsDNA. Shown is the electrostatic potential computed 3 Å away (radius of hydrated Mg2+ is ∼3Å) from the DNA surface. (C) The ion-inaccessible volume per unit length (Å) is given for tsDNA and dsDNA. (D) Given here are the radial distribution functions g(r) of Mg2+ with respect to the phosphate atoms of tsDNA and dsDNA. (E and F) Shown here is the distribution of residence time for the Mg2+ within 5.4 Å of the phosphate atoms for tsDNA and dsDNA, where 5.4 Å corresponds to the peak location in (D). To see this figure in color, go online.

Therefore, the stronger external binding to tsDNA than to dsDNA is attributed to the enhancement of the electrostatic potential and smaller ion-accessible volume in the grooves caused by the third nucleotide strand, which leads to stronger external binding of Mg2+ to bridge adjacent helices to induce an effective attraction. We also note that a larger fraction of spermine in the external shell for tsRNA of poly(A·U·U) than that for dsRNA of poly(A·U) was proposed to understand the condensation of poly(A·U) in spermine solutions, because the tsRNA of poly(A·U·U) can possibly be formed in the presence of spermine (48). Additionally, the recent MD simulations for RNA triplex observed that multivalent cations of spermines have a preference to bind more externally to a RNA triplex than to a RNA duplex (48), which is in analogy to our observation that the external binding of Mg2+ to a tsDNA is much more pronounced than to a dsDNA.

Bridging ions between DNAs: triplex versus duplex

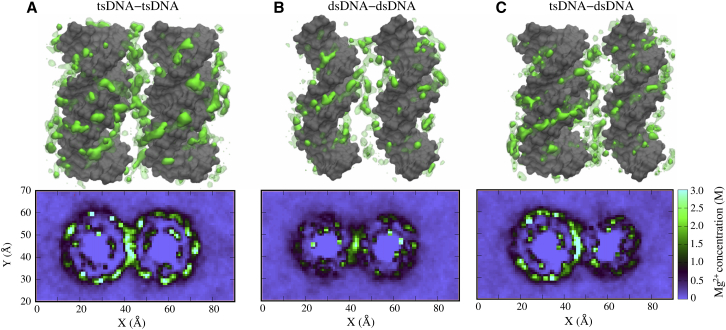

Going beyond a single helix, to understand the Mg2+-mediated PMFs between (ts and ds) DNAs, we can illustrate Mg2+ concentration distributions around two tsDNAs, two dsDNAs, and a tsDNA and a dsDNA. As shown in Fig. 5, there is a strong ion-bridging configuration between tsDNAs, whereas that between dsDNAs appears obviously weaker, which corresponds to the strongly attractive PMF between tsDNAs in Mg2+ solutions. For tsDNA-dsDNA, the ion-bridging is slightly weaker than for tsDNA-tsDNA and corresponds to that the Mg2+-mediated attraction between tsDNA and dsDNA is slightly weaker than that between tsDNAs. Furthermore, for a quantitative view of Mg2+ distributions, we calculated the 2D distributions for tsDNA-tsDNA, dsDNA-dsDNA, and tsDNA-dsDNA. As shown in Fig. 5, for tsDNA-tsDNA at ∼20 mM [Mg2+], the local concentration of Mg2+ in the interfacial region is very high (∼6 M), but for dsDNA-dsDNA, the Mg2+ concentration (∼4 M) is visibly lower than that for tsDNA-tsDNA. When DNAs approach each other, Mg2+ ions accumulate in the interfacial region to form ion-bridges between two DNAs, as shown in Fig. S6. Such an ion-bridge has been proposed to be responsible for the multivalent ion-mediated attraction between DNAs and between other polyelectrolytes (46, 47, 60, 68, 75, 76). As suggested above, the external binding of Mg2+ favors the ion-bridge and the effective attraction between DNAs.

Figure 5.

(Top panels) Given here are the illustrations for the region of high Mg2+ density (solid area >10 M, and transparent area >5 M) around two 16-bp DNAs in 20 mM Mg2+ solutions, respectively. (Bottom panels) Given here are the distributions of Mg2+ for the three cases corresponding to the top panels averaged over the MD trajectory and over the DNAs in the z direction. The DNA-DNA distance is 30 Å for tsDNA-tsDNA (A), 28 Å for dsDNA-dsDNA (B), and 29 Å for tsDNA-dsDNA (C). To see this figure in color, go online.

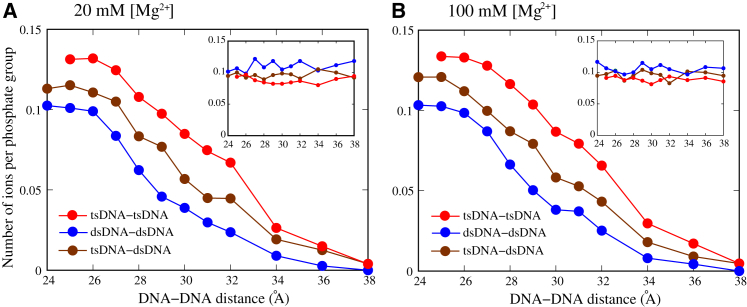

Because there is no available physical definition for bridging ions, we would define bridging ions as those residing within a short cutoff distance rc of 9 Å from the surface atoms of both DNAs. This definition is based on the spatial positions of ions relative to both the two DNAs, and the slight change in cutoff distance rc around 9 Å does not qualitatively influence our analyses (see below). As shown in Fig. 6, the number of bridging ions increases as the two DNAs become close, and such increase in the number of bridging Mg2+ is much more pronounced for tsDNAs, indicating a stronger ion-bridging effect for tsDNAs and consequently a stronger effective attraction between tsDNAs. It is not strange that the number of bridging ions is not very sensitive to the increase of bulk [Mg2+] (from ∼20 to ∼100 mM), because multivalent ion-binding near the DNA surface is more dependent on the electrostatic field nearby than on bulk ion concentration (21, 72). However, the increase of bulk [Mg2+] would reduce the entropy penalty for ion-binding and consequently could cause stronger effective attraction between DNAs (63, 72). When the DNA-DNA distance becomes less than a certain value (e.g., ∼29 Å for tsDNAs), the increase in the number of bridging ions slows down and the rapid increase in Coulomb repulsion between the negative charges on the two DNAs results in a strong short-range repulsion between DNAs. Moreover, as shown in Fig. S7, the bridging Mg2+ ions between DNAs are dynamic (with a residence time of no more than a nanosecond) and the residence time of bridging Mg2+ for tsDNAs is longer than that for dsDNAs, indicating a more pronounced bridging effect for tsDNAs.

Figure 6.

(A and B) Shown here are the numbers of bridging Mg2+ ions and internal binding Mg2+ ions (in insets) per phosphate group as functions of the DNA-DNA distance. Here, it should be noted that the radius of tsDNA is larger than that of dsDNA. In general, the number of bridging ions for tsDNA-tsDNA is apparently more than that for dsDNA-dsDNA, whereas the number of internal binding ions for tsDNA-tsDNA is visibly less than that for dsDNA-dsDNA. To see this figure in color, go online.

In addition, we calculated the numbers of internal binding Mg2+ as functions of DNA-DNA distance for the tsDNA-tsDNA, dsDNA-dsDNA, and tsDNA-dsDNA. Fig. 6 shows that the numbers of internal binding Mg2+ ions remain almost invariable as two DNAs approach each other, indicating that the internal ion binding does not respond to the approaching DNAs and consequently makes no contribution to the effective attraction between the tsDNAs. This is reasonable because internal binding ions generally bind deeply into the grooves of a DNA and the approach of another DNA can only have a negligible effect on such ion binding.

Correlation between bridging ions and inter-DNA force

To reveal the role of bridging ions in modulating the effective attraction between DNAs, we further analyzed the bridging Mg2+ and instantaneous inter-DNA forces for tsDNAs in a 20 mM Mg2+ solution. Additional MD simulations were performed, in which tsDNAs were strongly restrained to keep them immobile, and the instantaneous force between the tsDNAs was calculated by (60, 77, 78)

| (4) |

where U(rN) is the total potential energy of the system, and d is the reaction coordinate (the distance between the mass centers of two DNAs). As the pair of DNAs is aligned along the z direction and separated in the x direction, the force only relates to the x component of the force acted on each atom of the DNAs. For this case, the inter-DNA force can be calculated by

| (5) |

where F1x and F2x are the total force in the x direction acting on the left DNA and right DNA, respectively; see the Supporting Material for more details.

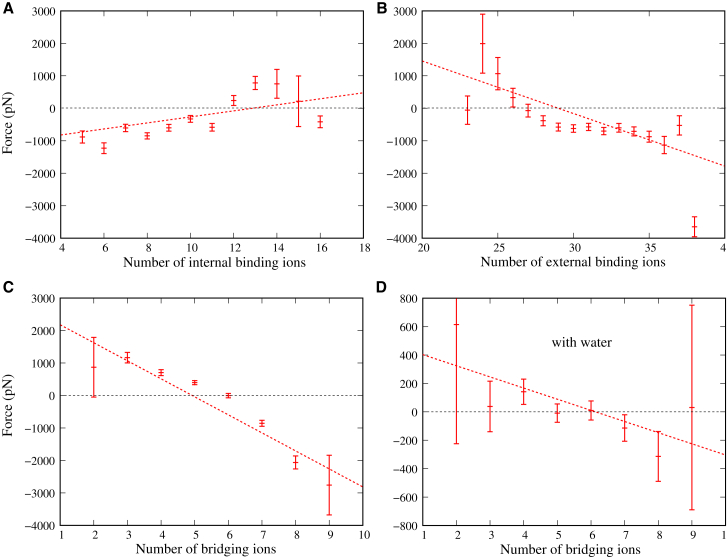

Fig. S9 shows the instantaneous force between tsDNAs and the instantaneous number of bridging Mg2+ as functions of MD running time, where water molecules are removed in the analyses due to the strong fluctuations. It is shown that the two curves fluctuate versus the MD running time and there is a visible correlation between the two curves: the fluctuation of the number of bridging Mg2+ to a high value would correspond to a stronger attraction force. Such a correlation coefficient is ∼−0.42, suggesting that bridging Mg2+ does contribute to the effective attraction between tsDNAs. Moreover, we examined the effect of the cutoff distance rc on the correlation between the instantaneous inter-DNA force and the number of bridging Mg2+. As shown in Fig. S8, with the different values for the cutoff distance rc for defining the bridging Mg2+, the instantaneous number of bridging ions also has a visible correlation with the instantaneous inter-DNA force, suggesting that the above analyses are robust. Fig. S9 also shows the instantaneous numbers of internal binding Mg2+ and external binding Mg2+. The correlation coefficients between the instantaneous inter-DNA force and the numbers of internal binding Mg2+ and external binding Mg2+ are ∼0.08 and ∼−0.14, respectively. This may suggest that the effective force between tsDNAs is positively correlated with the internal binding ions and negatively correlated with the external binding ions in a slight manner. The correlations between the inter-DNA force and the number of binding Mg2+ have been shown more directly in Fig. 7. In an analogy to the correlation coefficients calculated above, the correlation between inter-DNA force and the numbers of internal binding Mg2+ and external binding Mg2+ are weakly positive and negative, respectively. Furthermore, the correlation between the inter-DNA force and the number of bridging Mg2+ is strongly negative, i.e., the large and small numbers of bridging Mg2+ correspond to the attractive (negative) and repulsive (positive) inter-DNA forces for tsDNAs, respectively. Therefore, the above analyses show that the bridging Mg2+ ions as a special part of external binding ions are strongly coupled to the effective attraction between tsDNAs.

Figure 7.

Shown here is the coupling between inter-DNA force and internal binding Mg2+ (A), external binding Mg2+ (B), bridging Mg2+ (C), and bridging Mg2+ with the contribution of water molecules (D). Here, positive (negative) force indicates the effective repulsion (attraction). The inter-DNA forces corresponding to same number of bridging (or internal binding or external binding) Mg2+ ions are averaged and the error bars are obtained as standard errors of the averages. The distance between two tsDNAs is 32 Å. To see this figure in color, go online.

Furthermore, although the inclusion of water may bring a strong fluctuation, we examined the correlation between the number of bridging Mg2+ and the instantaneous inter-DNA force with the contribution of water molecules. We extracted ∼8000 conformations from the MD trajectory and performed energy minimization to remove all kinetic energy from the system to reduce the thermal noise. We then calculated the instantaneous inter-DNA force and number of bridging Mg2+ ions. Fig. 7 D shows that, as an analogy to Fig. 7 C, the negative correlation between the inter-DNA force and number of bridging Mg2+ still exists, except at a much lower (absolute) correlation slope. This illustrates that the bridging ions are critically important for the effective attraction between tsDNAs, and the number of bridging ions can emerge as an “order parameter” that correlates well with the ion-mediated attraction between DNAs.

In addition, the comparison between Fig. 7, C and D, shows that water molecules would provide a global screening for the inter-DNA force, i.e., the attractive (repulsive) force at large (small) numbers of bridging Mg2+ would become apparently weaker with the contribution of water molecules; see also Fig. S10. Such an effect is attributed to the nature of the strong electric dipole of water molecules. The rotation and translation of water molecules would significantly reduce the DNA-DNA Coulomb repulsion, which is also reflected by the high dielectric constant (∼78 at 25°C) of water in light of continuous dielectric model (79). However, the above analyses are only from the viewpoint of a simple exclusion/inclusion of water. In fact, the bridging ions and water molecules are strongly coupled, and the bridging ions can serve as an important modulator for water structure between two like-charged DNAs, as there would be orientational frustration for the water molecules between like-charged DNAs without the bridging (multivalent) ions. The bridging Mg2+ ions between tsDNAs can induce the structuring of water molecules with the O-atom toward the Mg2+ and the H-atom toward the phosphate groups, and such an effect is very apparent at 32 Å, where there are visible hydrogen-bonds between the H-atom and phosphate groups in the x direction and the attraction between tsDNAs is the strongest, as shown in Fig. S11. Therefore, the bridging ions contribute substantially to the effective attraction between tsDNAs, and water molecules may also make a contribution to such effective attraction through the structuring and hydrogen bonding with phosphate groups mediated by (multivalent) bridging ions (80, 81, 82).

Conclusions

This work shows that the Mg2+-mediated interaction between tsDNAs is apparently attractive, and such attraction becomes stronger at higher [Mg2+], whereas the effective interaction between dsDNAs mediated by Mg2+ cannot become apparently attractive even at high [Mg2+]. Our analyses show that such distinctive differences in the PMFs for tsDNAs and dsDNAs are attributed to the different ion-binding modes: Mg2+ will internally bind to groove and externally bind to the phosphate groups for both tsDNA and dsDNA, whereas the external binding to tsDNA is significantly stronger than that to dsDNA. The stronger external binding of Mg2+ to tsDNA (than to dsDNA) is attributed to the enhancement of electrostatic potential and less ion-accessible volume in the grooves caused by the third strand, and would favor more apparent ion-bridging between adjacent tsDNAs. Our additional calculations show that the PMF between tsDNA and dsDNA is attractive and the effective attraction is visibly weaker than that between tsDNAs. Furthermore, our microscopic analyses illustrate a tight coupling between bridging Mg2+ and the inter-DNA force. Our calculations are in accordance with existing experiments (20, 53). First, the calculated PMF between tsDNAs mediated by Mg2+ is strongly attractive whereas that between dsDNAs is not apparently attractive even at high [Mg2+], which implies that tsDNAs would have the apparently greater condensation tendency than dsDNAs in Mg2+ solutions. This is consistent with the experiments where Mg2+ can condense tsDNAs but it cannot condense dsDNAs (20). Second, the calculated inter-DNA forces from our MD simulations are close to those from the osmotic stress measurements (20, 53) for both tsDNAs and dsDNAs based on the additivity assumption (29, 60).

However, this work also involved some approximations and simplifications. First, in the MD simulations, the dsDNA and tsDNA are treated as rigid helical structures and the effect of DNA flexibility was ignored. Because the persistence length of DNA is large (≥500 Å) (38, 39, 83, 84), the ignorance of DNA flexibility would be a reasonable simplification. Second, in our MD simulations, we adopted the hydrated Mg2+ model proposed by Yoo and Aksimentiev (58), because the model can achieve a quantitative agreement with experiments on DNA assembly (58, 60). Although the ion model ignores the dehydration effect of Mg2+, previous studies have shown that Mg2+ generally keeps its hydration shell in solutions and seldom becomes dehydrated when interacting with DNA/RNA helices (85, 86). An accurate description of divalent ions in MD simulations requires realistic treatment of the polarizability and kinetics of the surrounding water (87), and developing a general model for ions, especially for Mg2+, remains a challenge. Third, the two DNAs are constrained in parallel in our simulations and thus the nonparallel configurations of DNAs were ignored in our work. Some previous studies have shown that the parallel configuration would be most favorable for large DNA-DNA distances (>∼28 Å) (88), whereas for small DNA-DNA distances, the parallel configuration will be unstable due to the strong short-range repulsion, and two DNAs would favor a typical x-shape configuration (89). Moreover, the nonparallel (rotational) configurations of DNAs could make unfavorable entropy contributions to DNA condensation free energy. The contribution of nonparallel configurations would become less important for long DNAs. This is beyond the scope of this work, and deserves to be studied separately. Nevertheless, this work will be very helpful for understanding the distinctively different condensation behaviors of tsDNAs and dsDNAs in Mg2+ solutions, as well as the multivalent ion-mediated attraction between DNAs.

Author Contributions

Z.-J.T., J.-P.S., and Z.-L.Z. designed the research. Z.-L.Z., Y.-Y.W., and K.X. performed the calculations. Z.-J.T., Z.-L.Z., and J.-P.S. analyzed the data. Z.-L.Z. and Z.-J.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professors Xiangyun Qiu (George Washington University), Shi-Jie Chen (University of Missouri), Nathan A. Baker (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory), Alexey V. Onufriev (Virginia Tech), and Wen-Bing Zhang (Wuhan University) for valuable discussions. Parts of the all-atom simulations in this work are performed on the supercomputing system in the Super Computing Center of Wuhan University.

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation of China grants (11374234, 11575128, 11175132, and 11647312).

Editor: Chris Chipot.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods and eleven figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30671-9.

Contributor Information

Jian-Ping Sang, Email: jpsang@acc-lab.whu.edu.cn.

Zhi-Jie Tan, Email: zjtan@whu.edu.cn.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Bloomfield V.A., Crothers D.M., Tinoco I., Jr. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 2000. Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties, and Functions. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luger K., Mäder A.W., Richmond T.J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teif V.B., Bohinc K. Condensed DNA: condensing the concepts. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011;105:208–222. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong G.C.L., Pollack L. Electrostatics of strongly charged biological polymers: ion-mediated interactions and self-organization in nucleic acids and proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2010;61:171–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipfert J., Doniach S., Herschlag D. Understanding nucleic acid-ion interactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014;83:813–841. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S.J. RNA folding: conformational statistics, folding kinetics, and ion electrostatics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:197–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodson S.A. Metal ions and RNA folding: a highly charged topic with a dynamic future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu X., Rau D.C., Gelbart W.M. Salt-dependent DNA-DNA spacings in intact bacteriophage λ reflect relative importance of DNA self-repulsion and bending energies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;106:028102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.028102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu X., Andresen K., Pollack L. Inter-DNA attraction mediated by divalent counterions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:038104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.038104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosberg A.Y., Nguyen T.T., Shklovskii B.I. Colloquium: the physics of charge inversion in chemical and biological systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002;74:329–345. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. Electrostatic free energy landscapes for nucleic acid helix assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6629–6639. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherstvy A.G. Electrostatic interactions in biological DNA-related systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:9942–9968. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02796k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J., Bratko D., Prausnitz J.M. Interaction between like-charged colloidal spheres in electrolyte solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15169–15172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler J.C., Angelini T., Wong G.C. Ion multivalence and like-charge polyelectrolyte attraction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91:028301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.028301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen Q., Tang J.X. Temperature effects on threshold counterion concentration to induce aggregation of fd virus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:048101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.048101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. Ion-mediated RNA structural collapse: effect of spatial confinement. Biophys. J. 2012;103:827–836. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y.Z., Jin L., Tan Z.J. Predicting 3D structure, flexibility, and stability of RNA hairpins in monovalent and divalent ion solutions. Biophys. J. 2015;109:2654–2665. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todd B.A., Rau D.C. Interplay of ion binding and attraction in DNA condensed by multivalent cations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:501–510. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L., Pabit S.A., Pollack L. Double-stranded RNA resists condensation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;106:108101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.108101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu X., Parsegian V.A., Rau D.C. Divalent counterion-induced condensation of triple-strand DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21482–21486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003374107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning G.S. The molecular theory of polyelectrolyte solutions with applications to the electrostatic properties of polynucleotides. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1978;11:179–246. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray J., Manning G.S. Formation of loose clusters in polyelectrolyte solutions. Macromolecules. 2000;33:2901–2908. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker N.A. Poisson-Boltzmann methods for biomolecular electrostatics. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:94–118. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker N.A., Sept D., McCammon J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu B., Cheng X., McCammon J.A. AFMPB: an adaptive fast multipole Poisson–Boltzmann solver for calculating electrostatics in biomolecular systems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010;181:1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen D., Chen Z., Wei G.W. MIBPB: a software package for electrostatic analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:756–770. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boschitsch A.H., Fenley M.O., Zhou H.X. Fast boundary element method for the linear Poisson-Boltzmann equation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:2741–2754. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. Electrostatic correlations and fluctuations for ion binding to a finite length polyelectrolyte. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;122:44903. doi: 10.1063/1.1842059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. Ion-mediated nucleic acid helix-helix interactions. Biophys. J. 2006;91:518–536. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan Z.J., Chen S.J. Predicting ion binding properties for RNA tertiary structures. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1565–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kornyshev A.A., Leikin S. Electrostatic zipper motif for DNA aggregation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;82:4138–4141. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kornyshev A.A., Leikin S. Helical structure determines different susceptibilities of dsDNA, dsRNA, and tsDNA to counterion-induced condensation. Biophys. J. 2013;104:2031–2041. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlick T. Vol. 21. Springer Science & Business Media; Berlin, Germany: 2010. (Molecular Modeling and Simulation. An Interdisciplinary Guide). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim T., Freudenthal B.D., Schlick T. Insertion of oxidized nucleotide triggers rapid DNA polymerase opening. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4409–4424. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X., Yu T., Chen S.J. Understanding the kinetic mechanism of RNA single base pair formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:116–121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517511113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., Gong S., Zhang W. The thermodynamics and kinetics of a nucleotide base pair. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144:115101. doi: 10.1063/1.4944067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korolev N., Lyubartsev A.P., Nordenskiöld L. A molecular dynamics simulation study of oriented DNA with polyamine and sodium counterions: diffusion and averaged binding of water and cations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5971–5981. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Y.Y., Bao L., Tan Z.J. Flexibility of short DNA helices with finite-length effect: from base pairs to tens of base pairs. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:125103. doi: 10.1063/1.4915539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao L., Zhang X., Tan Z.J. Understanding of the relative flexibility of RNA and DNA duplexes: stretching and twist-stretch coupling. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1094–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J., Xiao Y. Types and concentrations of metal ions affect local structure and dynamics of RNA. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2016;94:040401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.94.040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J., Zhao Y., Xiao Y. Computational study of stability of an H-H-type pseudoknot motif. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2015;92:062705. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.062705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi W., Song B., Fang H. DNA base pair hybridization and water-mediated metastable structures studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9628–9632. doi: 10.1021/bi2002778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang F.H., Wu Y.Y., Tan Z.J. Salt contribution to the flexibility of single-stranded nucleic acid of finite length. Biopolymers. 2013;99:370–381. doi: 10.1002/bip.22189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drozdetski A.V., Tolokh I.S., Onufriev A.V. Opposing effects of multivalent ions on the flexibility of DNA and RNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117:028101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.028101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tolokh I.S., Pabit S.A., Onufriev A.V. Why double-stranded RNA resists condensation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:10823–10831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y.Y., Zhang Z.L., Tan Z.J. Multivalent ion-mediated nucleic acid helix-helix interactions: RNA versus DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6156–6165. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolokh I.S., Drozdetski A.V., Onufriev A.V. Multi-shell model of ion-induced nucleic acid condensation. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144:155101. doi: 10.1063/1.4945382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katz A.M., Tolokh I.S., Pollack L. Spermine condenses DNA, but not RNA duplexes. Biophys. J. 2017;112:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox K.R., Brown T. Formation of stable DNA triplexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011;39:629–634. doi: 10.1042/BST0390629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seidman M.M., Glazer P.M. The potential for gene repair via triple helix formation. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:487–494. doi: 10.1172/JCI19552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang G., Seidman M.M., Glazer P.M. Mutagenesis in mammalian cells induced by triple helix formation and transcription-coupled repair. Science. 1996;271:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruan H., Wang Y.H. Friedreich’s ataxia GAA.TTC duplex and GAA.GAA.TTC triplex structures exclude nucleosome assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;383:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li J., Wijeratne S.S., Kiang C.H. DNA under force: mechanics, electrostatics, and hydration. Nanomaterials. 2015;5:246–267. doi: 10.3390/nano5010246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Case D.A., Cheatham T.E., 3rd, Woods R.J. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raghunathan G., Miles H.T., Sasisekharan V. Symmetry and molecular structure of a DNA triple helix: d(T)n.d(A)n.d(T)n. Biochemistry. 1993;32:455–462. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pérez A., Marchán I., Orozco M. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of α/γ conformers. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3817–3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoo J., Aksimentiev A. Improved parametrization of Li+, Na+, K+, and Mg2+ ions for all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of nucleic acid systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo Y., Roux B. Simulation of osmotic pressure in concentrated aqueous salt solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo J., Aksimentiev A. The structure and intermolecular forces of DNA condensates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2036–2046. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hénin J., Chipot C. Overcoming free energy barriers using unconstrained molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:2904–2914. doi: 10.1063/1.1773132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y.Y., Wang F.H., Tan Z.J. Calculating potential of mean force between like-charged nanoparticles: a comprehensive study on salt effects. Phys. Lett. A. 2013;377:1911–1919. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar S., Rosenberg J.M., Kollman P.A. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Unni S., Huang Y., Baker N.A. Web servers and services for electrostatics calculations with APBS and PDB2PQR. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:1488–1491. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bai Y., Das R., Doniach S. Probing counterion modulated repulsion and attraction between nucleic acid duplexes in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:1035–1040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404448102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoo J., Kim H., Ha T. Direct evidence for sequence-dependent attraction between double-stranded DNA controlled by methylation. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11045. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li W., Nordenskiöld L., Mu Y. Conformation-dependent DNA attraction. Nanoscale. 2014;6:7085–7092. doi: 10.1039/c3nr03235c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakata M., Zanchetta G., Clark N.A. End-to-end stacking and liquid crystal condensation of 6 to 20 base pair DNA duplexes. Science. 2007;318:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.1143826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang X., Zhang J.S., Tan Z.J. Potential of mean force between like-charged nanoparticles: many-body effect. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23434. doi: 10.1038/srep23434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goobes R., Cohen O., Minsky A. Unique condensation patterns of triplex DNA: physical aspects and physiological implications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2154–2161. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kennard O., Hunter W.N. Oligonucleotide structure: a decade of results from single crystal x-ray diffraction studies. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1989;22:327–379. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Savelyev A., Papoian G.A. Electrostatic, steric, and hydration interactions favor Na+ condensation around DNA compared with K+ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14506–14518. doi: 10.1021/ja0629460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dai L., Mu Y., van der Maarel J.R. Molecular dynamics simulation of multivalent-ion mediated attraction between DNA molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:118301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.118301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luan B., Aksimentiev A. DNA attraction in monovalent and divalent electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15754–15755. doi: 10.1021/ja804802u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Darve E., Pohorille A. Calculating free energies using average force. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;115:9169–9183. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ruiz-Montero M.J., Frenkel D., Brey J.J. Efficient schemes to compute diffusive barrier crossing rates. Mol. Phys. 1997;90:925–942. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uematsu M., Frank E.U. Static dielectric constant of water and steam. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1980;9:1291–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rau D.C., Parsegian V.A. Direct measurement of the intermolecular forces between counterion-condensed DNA double helices. Evidence for long range attractive hydration forces. Biophys. J. 1992;61:246–259. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81831-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rau D.C., Parsegian V.A. Direct measurement of temperature-dependent solvation forces between DNA double helices. Biophys. J. 1992;61:260–271. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stanley C., Rau D.C. Evidence for water structuring forces between surfaces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;16:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lipfert J., Skinner G.M., Dekker N.H. Double-stranded RNA under force and torque: similarities to and striking differences from double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15408–15413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407197111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Herrero-Galán E., Fuentes-Perez M.E., Arias-Gonzalez J.R. Mechanical identities of RNA and DNA double helices unveiled at the single-molecule level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:122–131. doi: 10.1021/ja3054755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chiu T.K., Dickerson R.E. 1 A crystal structures of B-DNA reveal sequence-specific binding and groove-specific bending of DNA by magnesium and calcium. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301:915–945. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robbins T.J., Wang Y. Effect of initial ion positions on the interactions of monovalent and divalent ions with a DNA duplex as revealed with atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2013;31:1311–1323. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.732344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jiao D., King C., Ren P. Simulation of Ca2+ and Mg2+ solvation using polarizable atomic multipole potential. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:18553–18559. doi: 10.1021/jp062230r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kornyshev A.A., Leikin S. Electrostatic interaction between long, rigid helical macromolecules at all interaxial angles. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 2000;62(2 Pt B):2576–2596. doi: 10.1103/physreve.62.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Várnai P., Timsit Y. Differential stability of DNA crossovers in solution mediated by divalent cations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4163–4172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.